Market Failure: Merit & Demerit Goods ( AQA A Level Economics )

Revision note.

Psychology Content Creator

Classification of Merit and Demerit Goods

Merit goods are products that are beneficial for society but the free market does not provide enough of them

Demerit goods are products which have harmful impacts on consumers or society

Value judgements play a role in determining whether goods are classified as merit or demerit goods

Some goods are clearly defined as being a merit or demerit good, such as education (merit good) and illegal drugs (demerit good)

The classification of some goods can be unclear as it is based on a value judgement

Classification of Goods Based on Value Judgements

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ||

|

Merit Goods

Consumers under-consume merit goods as they do not fully recognise the private or external benefits

Merit goods are often under-provided in a free-market and are a cause of partial market failure

Common examples include vaccinations, education and electric cars

Governments often have to subsidise these goods in order to lower the price and/or increase the quantity demanded

Diagram: Merit Goods in a Free Market

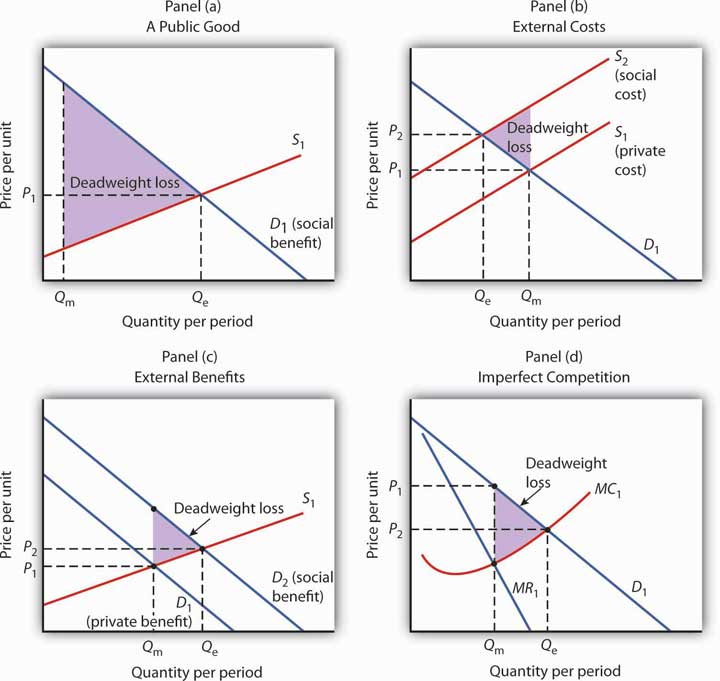

Positive externalities from the consumption of merit goods

Diagram analysis

The marginal social costs (MSC) are assumed to be equal to the marginal private cost (MPC) as the focus is on the consumer (demand side) of the market

The optimal allocation of resources for society would generate an equilibrium where marginal social benefit (MSB) = MSC

At P e Q e where there is no market failure

The free-market equilibrium for merit goods is under consumed as consumers fail to consider the external benefits from consumption

This is shown at P e Q e where the MPB=MSC

The quantity consumed at Q e is below the socially optimal level resulting in an under-consumption and a partial market failure . There is a deadweight loss to society (pink triangle)

To be socially efficient , more factors of production should be allocated to producing this good/service

Worked Example

Which one of the following applies to merit goods?

They are always over consumed by individuals

They are likely to be provided by the market

They can only be supplied by the government

They are always free

B. They are likely to be provided by the market.

Merit goods (education and hospitals) can often be provided by the market. They are beneficial to society and usually not enough are provided.

Demerit Goods

Consumers over-consume demerit goods to a greater extent than is considered desirable by society

Consumers are unlikely to consider all of the consequences when making consumption decisions

The social costs of consumption outweigh the private costs

Demerit goods are often over-provided in a free-market and are a cause of partial market failure

These goods are usually addictive and harmful for consumers, e.g. gambling, alcohol, drugs, sugary foods/drinks

Governments often have to regulate these goods in such a way that they raise the prices and/or limit the quantity demanded

The activities of producers can generate significant external costs, e.g. pollution caused by coal-burning power stations during the production of electricity

However, electricity is considered to be a merit good

The smoke is a by-product and not a good/service

For this reason, economists usually consider demerit goods to be goods used in consumption

Diagram: Demerit Goods in a Free Market

Negative externalities from the consumption of demerit goods

The MSC is assumed to be equal to the MPC as the focus is on the consumer (demand) side of the market

The optimal allocation of resources for society would generate an equilibrium where MSB = MSC

At P e Q e where there is no market failure

The free-market equilibrium for demerit goods is over consumed as consumers fail to consider the external costs from consumption

The quantity consumed at Q e is above the socially optimal level, resulting in overconsumption and a partial market failure . There is a deadweight loss to society (pink triangle)

To be socially efficient , fewer factors of production should be allocated to producing this good/service

Examiner Tip

Not all products that result in positive or negative externalities in consumption are merit or demerit goods. This is a common misconception.

You should be able to illustrate the misallocation of resources resulting from the consumption of merit and demerit goods using diagrams showing marginal private and social cost and benefit curves.

Which of the following applies to demerit goods

Their marginal private benefit is greater than their marginal social benefit

They are always under provided by the market

Their marginal social benefit is greater than their marginal private benefit

They have the characteristics of non-excludability and non-rivalry

A. Their marginal private benefit is greater than their marginal social benefit

Individuals may derive some private benefit from consuming demerit goods, but the overall social benefit is less due to the negative consequences on society. The MPB (the benefit to the individual consumer) tends to exceed the MSB (the benefit to society as a whole)

The other options are incorrect:

Demerit goods may tend to be over-provided and over-consumed by the free market

Demerit goods are associated with negative externalities, implying that the social benefit is less than the private benefit

Demerit goods can often be characterised by excludability and rivalry, meaning they can be restricted to to those willing and able to pay and their consumption by one person reduces its availability to others

Merit & Demerit Goods & Imperfect Information

A lack of information can make it difficult for consumers to make decisions about a good or service

Due to imperfect information , consumers may have incomplete or inaccurate information about the external consequences associated with merit or demerit goods

Merit goods are often under-provided , due to a lack of demand. Consumers are often unaware of the positive effects of consuming such goods

Demerit goods are often over-provided , due to high demand a s consumers are ill-informed regarding the consequences of consuming such goods

Efforts to educate the public by the government, such as public awareness campaigns can help consumers make more informed choices

You've read 0 of your 10 free revision notes

Unlock more, it's free, join the 100,000 + students that ❤️ save my exams.

the (exam) results speak for themselves:

Did this page help you?

- The Market Mechanism, Market Failure & Government Intervention

- Measuring Macroeconomic Performance

- How the Macroeconomy Works

- Economic Performance

- Financial Markets & Monetary Policy

- Fiscal & Supply-side Policies

- The International Economy

- Economic Methodology & the Economic Problem

- Individual Economic Decision Making

- Price Determination in Competitive Markets

Author: Claire Neeson

Expertise: Psychology Content Creator

Claire has been teaching for 34 years, in the UK and overseas. She has taught GCSE, A-level and IB Psychology which has been a lot of fun and extremely exhausting! Claire is now a freelance Psychology teacher and content creator, producing textbooks, revision notes and (hopefully) exciting and interactive teaching materials for use in the classroom and for exam prep. Her passion (apart from Psychology of course) is roller skating and when she is not working (or watching 'Coronation Street') she can be found busting some impressive moves on her local roller rink.

3.1 Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium in Markets for Goods and Services

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain demand, quantity demanded, and the law of demand

- Explain supply, quantity supplied, and the law of supply

- Identify a demand curve and a supply curve

- Explain equilibrium, equilibrium price, and equilibrium quantity

First let’s first focus on what economists mean by demand, what they mean by supply, and then how demand and supply interact in a market.

Demand for Goods and Services

Economists use the term demand to refer to the amount of some good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase at each price. Demand is fundamentally based on needs and wants—if you have no need or want for something, you won't buy it. While a consumer may be able to differentiate between a need and a want, from an economist’s perspective they are the same thing. Demand is also based on ability to pay. If you cannot pay for it, you have no effective demand. By this definition, a person who does not have a drivers license has no effective demand for a car.

What a buyer pays for a unit of the specific good or service is called price . The total number of units that consumers would purchase at that price is called the quantity demanded . A rise in price of a good or service almost always decreases the quantity demanded of that good or service. Conversely, a fall in price will increase the quantity demanded. When the price of a gallon of gasoline increases, for example, people look for ways to reduce their consumption by combining several errands, commuting by carpool or mass transit, or taking weekend or vacation trips closer to home. Economists call this inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded the law of demand . The law of demand assumes that all other variables that affect demand (which we explain in the next module) are held constant.

We can show an example from the market for gasoline in a table or a graph. Economists call a table that shows the quantity demanded at each price, such as Table 3.1 , a demand schedule . In this case we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline. We measure the quantity demanded in millions of gallons over some time period (for example, per day or per year) and over some geographic area (like a state or a country). A demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded on a graph like Figure 3.2 , with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price per gallon on the vertical axis. (Note that this is an exception to the normal rule in mathematics that the independent variable (x) goes on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable (y) goes on the vertical axis. While economists often use math, they are different disciplines.)

Table 3.1 shows the demand schedule and the graph in Figure 3.2 shows the demand curve. These are two ways to describe the same relationship between price and quantity demanded.

| Price (per gallon) | Quantity Demanded (millions of gallons) |

|---|---|

| $1.00 | 800 |

| $1.20 | 700 |

| $1.40 | 600 |

| $1.60 | 550 |

| $1.80 | 500 |

| $2.00 | 460 |

| $2.20 | 420 |

Demand curves will appear somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right. Demand curves embody the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Confused about these different types of demand? Read the next Clear It Up feature.

Clear It Up

Is demand the same as quantity demanded.

In economic terminology, demand is not the same as quantity demanded. When economists talk about demand, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities demanded at those prices, as illustrated by a demand curve or a demand schedule. When economists talk about quantity demanded, they mean only a certain point on the demand curve, or one quantity on the demand schedule. In short, demand refers to the curve and quantity demanded refers to a (specific) point on the curve.

Supply of Goods and Services

When economists talk about supply , they mean the amount of some good or service a producer is willing to supply at each price. Price is what the producer receives for selling one unit of a good or service . A rise in price almost always leads to an increase in the quantity supplied of that good or service, while a fall in price will decrease the quantity supplied. When the price of gasoline rises, for example, it encourages profit-seeking firms to take several actions: expand exploration for oil reserves; drill for more oil; invest in more pipelines and oil tankers to bring the oil to plants for refining into gasoline; build new oil refineries; purchase additional pipelines and trucks to ship the gasoline to gas stations; and open more gas stations or keep existing gas stations open longer hours. Economists call this positive relationship between price and quantity supplied—that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied and a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied—the law of supply . The law of supply assumes that all other variables that affect supply (to be explained in the next module) are held constant.

Still unsure about the different types of supply? See the following Clear It Up feature.

Is supply the same as quantity supplied?

In economic terminology, supply is not the same as quantity supplied. When economists refer to supply, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities supplied at those prices, a relationship that we can illustrate with a supply curve or a supply schedule. When economists refer to quantity supplied, they mean only a certain point on the supply curve, or one quantity on the supply schedule. In short, supply refers to the curve and quantity supplied refers to a (specific) point on the curve.

Figure 3.3 illustrates the law of supply, again using the market for gasoline as an example. Like demand, we can illustrate supply using a table or a graph. A supply schedule is a table, like Table 3.2 , that shows the quantity supplied at a range of different prices. Again, we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline and we measure quantity supplied in millions of gallons. A supply curve is a graphic illustration of the relationship between price, shown on the vertical axis, and quantity, shown on the horizontal axis. The supply schedule and the supply curve are just two different ways of showing the same information. Notice that the horizontal and vertical axes on the graph for the supply curve are the same as for the demand curve.

| Price (per gallon) | Quantity Supplied (millions of gallons) |

|---|---|

| $1.00 | 500 |

| $1.20 | 550 |

| $1.40 | 600 |

| $1.60 | 640 |

| $1.80 | 680 |

| $2.00 | 700 |

| $2.20 | 720 |

The shape of supply curves will vary somewhat according to the product: steeper, flatter, straighter, or curved. Nearly all supply curves, however, share a basic similarity: they slope up from left to right and illustrate the law of supply: as the price rises, say, from $1.00 per gallon to $2.20 per gallon, the quantity supplied increases from 500 gallons to 720 gallons. Conversely, as the price falls, the quantity supplied decreases.

Equilibrium—Where Demand and Supply Intersect

Because the graphs for demand and supply curves both have price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, the demand curve and supply curve for a particular good or service can appear on the same graph. Together, demand and supply determine the price and the quantity that will be bought and sold in a market.

Figure 3.4 illustrates the interaction of demand and supply in the market for gasoline. The demand curve (D) is identical to Figure 3.2 . The supply curve (S) is identical to Figure 3.3 . Table 3.3 contains the same information in tabular form.

| Price (per gallon) | Quantity demanded (millions of gallons) | Quantity supplied (millions of gallons) |

|---|---|---|

| $1.00 | 800 | 500 |

| $1.20 | 700 | 550 |

| $1.60 | 550 | 640 |

| $1.80 | 500 | 680 |

| $2.00 | 460 | 700 |

| $2.20 | 420 | 720 |

Remember this: When two lines on a diagram cross, this intersection usually means something. The point where the supply curve (S) and the demand curve (D) cross, designated by point E in Figure 3.4 , is called the equilibrium . The equilibrium price is the only price where the plans of consumers and the plans of producers agree—that is, where the amount of the product consumers want to buy (quantity demanded) is equal to the amount producers want to sell (quantity supplied). Economists call this common quantity the equilibrium quantity . At any other price, the quantity demanded does not equal the quantity supplied, so the market is not in equilibrium at that price.

In Figure 3.4 , the equilibrium price is $1.40 per gallon of gasoline and the equilibrium quantity is 600 million gallons. If you had only the demand and supply schedules, and not the graph, you could find the equilibrium by looking for the price level on the tables where the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied are equal.

The word “equilibrium” means “balance.” If a market is at its equilibrium price and quantity, then it has no reason to move away from that point. However, if a market is not at equilibrium, then economic pressures arise to move the market toward the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

Imagine, for example, that the price of a gallon of gasoline was above the equilibrium price—that is, instead of $1.40 per gallon, the price is $1.80 per gallon. The dashed horizontal line at the price of $1.80 in Figure 3.4 illustrates this above-equilibrium price. At this higher price, the quantity demanded drops from 600 to 500. This decline in quantity reflects how consumers react to the higher price by finding ways to use less gasoline.

Moreover, at this higher price of $1.80, the quantity of gasoline supplied rises from 600 to 680, as the higher price makes it more profitable for gasoline producers to expand their output. Now, consider how quantity demanded and quantity supplied are related at this above-equilibrium price. Quantity demanded has fallen to 500 gallons, while quantity supplied has risen to 680 gallons. In fact, at any above-equilibrium price, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. We call this an excess supply or a surplus .

With a surplus, gasoline accumulates at gas stations, in tanker trucks, in pipelines, and at oil refineries. This accumulation puts pressure on gasoline sellers. If a surplus remains unsold, those firms involved in making and selling gasoline are not receiving enough cash to pay their workers and to cover their expenses. In this situation, some producers and sellers will want to cut prices, because it is better to sell at a lower price than not to sell at all. Once some sellers start cutting prices, others will follow to avoid losing sales. These price reductions in turn will stimulate a higher quantity demanded. Therefore, if the price is above the equilibrium level, incentives built into the structure of demand and supply will create pressures for the price to fall toward the equilibrium.

Now suppose that the price is below its equilibrium level at $1.20 per gallon, as the dashed horizontal line at this price in Figure 3.4 shows. At this lower price, the quantity demanded increases from 600 to 700 as drivers take longer trips, spend more minutes warming up the car in the driveway in wintertime, stop sharing rides to work, and buy larger cars that get fewer miles to the gallon. However, the below-equilibrium price reduces gasoline producers’ incentives to produce and sell gasoline, and the quantity supplied falls from 600 to 550.

When the price is below equilibrium, there is excess demand , or a shortage —that is, at the given price the quantity demanded, which has been stimulated by the lower price, now exceeds the quantity supplied, which has been depressed by the lower price. In this situation, eager gasoline buyers mob the gas stations, only to find many stations running short of fuel. Oil companies and gas stations recognize that they have an opportunity to make higher profits by selling what gasoline they have at a higher price. As a result, the price rises toward the equilibrium level. Read Demand, Supply, and Efficiency for more discussion on the importance of the demand and supply model.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/3-1-demand-supply-and-equilibrium-in-markets-for-goods-and-services

© Jul 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Economics Essay Examples

Ace Your Essay With Our Economics Essay Examples

Published on: Jun 6, 2023

Last updated on: Jan 31, 2024

Share this article

Are you struggling to understand economics essays and how to write your own?

It can be challenging to grasp the complexities of economic concepts without practical examples.

But don’t worry!

We’ve got the solution you've been looking for. Explore quality examples that bridge the gap between theory and real-world applications. In addition, get insightful tips for writing economics essays.

So, if you're a student aiming for academic success, this blog is your go-to resource for mastering economics essays.

Let’s dive in and get started!

On This Page On This Page -->

What is an Economics Essay?

An economics essay is a written piece that explores economic theories, concepts, and their real-world applications. It involves analyzing economic issues, presenting arguments, and providing evidence to support ideas.

The goal of an economics essay is to demonstrate an understanding of economic principles and the ability to critically evaluate economic topics.

Why Write an Economics Essay?

Writing an economics essay serves multiple purposes:

- Demonstrate Understanding: Showcasing your comprehension of economic concepts and their practical applications.

- Develop Critical Thinking: Cultivating analytical skills to evaluate economic issues from different perspectives.

- Apply Theory to Real-World Contexts: Bridging the gap between economic theory and real-life scenarios.

- Enhance Research and Analysis Skills: Improving abilities to gather and interpret economic data.

- Prepare for Academic and Professional Pursuits: Building a foundation for success in future economics-related endeavors.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

If youâre wondering, âhow do I write an economics essay?â, consulting an example essay might be a good option for you. Here are some economics essay examples:

Short Essay About Economics

Fiscal policy plays a crucial role in shaping economic conditions and promoting growth. During periods of economic downturn or recession, governments often resort to fiscal policy measures to stimulate the economy. This essay examines the significance of fiscal policy in economic stimulus, focusing on two key tools: government spending and taxation. Government spending is a powerful instrument used to boost economic activity. When the economy experiences a slowdown, increased government expenditure can create a multiplier effect, stimulating demand and investment. By investing in infrastructure projects, education, healthcare, and other sectors, governments can create jobs, generate income, and spur private sector activity. This increased spending circulates money throughout the economy, leading to higher consumption and increased business investments. However, it is important for governments to strike a balance between short-term stimulus and long-term fiscal sustainability. Taxation is another critical aspect of fiscal policy. During economic downturns, governments may employ tax cuts or incentives to encourage consumer spending and business investments. By reducing tax burdens on individuals and corporations, governments aim to increase disposable income and boost consumption. Lower taxes can also incentivize businesses to expand and invest in new ventures, leading to job creation and economic growth. However, it is essential for policymakers to consider the trade-off between short-term stimulus and long-term fiscal stability, ensuring that tax cuts are sustainable and do not result in excessive budget deficits. In conclusion, fiscal policy serves as a valuable tool in stimulating economic growth and mitigating downturns. Through government spending and taxation measures, policymakers can influence aggregate demand, promote investment, and create a favorable economic environment. However, it is crucial for governments to implement these policies judiciously, considering the long-term implications and maintaining fiscal discipline. By effectively managing fiscal policy, governments can foster sustainable economic growth and improve overall welfare. |

A Level Economics Essay Examples

Here is an essay on economics a level structure:

Globalization, characterized by the increasing interconnectedness of economies and societies worldwide, has brought about numerous benefits and challenges. One of the significant issues associated with globalization is its impact on income inequality. This essay explores the implications of globalization on income inequality, discussing both the positive and negative effects, and examining potential policy responses to address this issue. Globalization has had a profound impact on income inequality, posing challenges for policymakers. While it has facilitated economic growth and raised living standards in many countries, it has also exacerbated income disparities. By implementing effective policies that focus on education, skill development, redistribution, and inclusive growth, governments can strive to reduce income inequality and ensure that the benefits of globalization are more widely shared. It is essential to strike a balance between the opportunities offered by globalization and the need for social equity and inclusive development in an interconnected world. |

Band 6 Economics Essay Examples

Government intervention in markets is a topic of ongoing debate in economics. While free markets are often considered efficient in allocating resources, there are instances where government intervention becomes necessary to address market failures and promote overall welfare. This essay examines the impact of government intervention on market efficiency, discussing the advantages and disadvantages of such interventions and assessing their effectiveness in achieving desired outcomes. Government intervention plays a crucial role in addressing market failures and promoting market efficiency. By correcting externalities, providing public goods and services, and reducing information asymmetry, governments can enhance overall welfare and ensure efficient resource allocation. However, policymakers must exercise caution to avoid unintended consequences and market distortions. Striking a balance between market forces and government intervention is crucial to harness the benefits of both, fostering a dynamic and efficient economy that serves the interests of society as a whole. |

Here are some downloadable economics essays:

Economics essay pdf

Economics essay introduction

Economics Extended Essay Examples

In an economics extended essay, students have the opportunity to delve into a specific economic topic of interest. They are required to conduct an in-depth analysis of this topic and compile a lengthy essay.

Here are some potential economics extended essay question examples:

- How does foreign direct investment impact economic growth in developing countries?

- What are the factors influencing consumer behavior and their effects on market demand for sustainable products?

- To what extent does government intervention in the form of minimum wage policies affect employment levels and income inequality?

- What are the economic consequences of implementing a carbon tax to combat climate change?

- How does globalization influence income distribution and the wage gap in developed economies?

IB Economics Extended Essay Examples

IB Economics Extended Essay Examples

Economics Extended Essay Topic Examples

Extended Essay Research Question Examples Economics

Tips for Writing an Economics Essay

Writing an economics essay requires specific expertise and skills. So, it's important to have some tips up your sleeve to make sure your essay is of high quality:

- Start with a Clear Thesis Statement: It defines your essay's focus and argument. This statement should be concise, to the point, and present the crux of your essay.

- Conduct Research and Gather Data: Collect facts and figures from reliable sources such as academic journals, government reports, and reputable news outlets. Use this data to support your arguments and analysis and compile a literature review.

- Use Economic Theories and Models: These help you to support your arguments and provide a framework for your analysis. Make sure to clearly explain these theories and models so that the reader can follow your reasoning.

- Analyze the Micro and Macro Aspects: Consider all angles of the topic. This means examining how the issue affects individuals, businesses, and the economy as a whole.

- Use Real-World Examples: Practical examples and case studies help to illustrate your points. This can make your arguments more relatable and understandable.

- Consider the Policy Implications: Take into account the impacts of your analysis. What are the potential solutions to the problem you're examining? How might different policies affect the outcomes you're discussing?

- Use Graphs and Charts: These help to illustrate your data and analysis. These visual aids can help make your arguments more compelling and easier to understand.

- Proofread and Edit: Make sure to proofread your essay carefully for grammar and spelling errors. In economics, precision and accuracy are essential, so errors can undermine the credibility of your analysis.

These tips can help make your essay writing journey a breeze. Tailor them to your topic to make sure you end with a well-researched and accurate economics essay.

To wrap it up , writing an economics essay requires a combination of solid research, analytical thinking, and effective communication.

You can craft a compelling piece of work by taking our examples as a guide and following the tips.

However, if you are still questioning "how do I write an economics essay?", it's time to get professional help from the best essay writing service - CollegeEssay.org.

Our economics essay writing service is always ready to help students like you. Our experienced economics essay writers are dedicated to delivering high-quality, custom-written essays that are 100% plagiarism free.

Also try out our AI essay writer and get your quality economics essay now!

Barbara P (Literature)

Barbara is a highly educated and qualified author with a Ph.D. in public health from an Ivy League university. She has spent a significant amount of time working in the medical field, conducting a thorough study on a variety of health issues. Her work has been published in several major publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

OFF ON CUSTOM ESSAYS

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Learning Materials

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Merit and Demerit Goods

When the facts change, I change my mind.

Millions of flashcards designed to help you ace your studies

- Cell Biology

Merit goods lead to _________ .

Review generated flashcards

to start learning or create your own AI flashcards

Start learning or create your own AI flashcards

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Merit and Demerit Goods Teachers

- 11 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

- Asymmetric Information

- Consumer Choice

- Economic Principles

- Factor Markets

- Imperfect Competition

- Labour Market

- Market Efficiency

- Antitrust Law

- Coase Theorem

- Common Resources

- Competition Policy

- Competitive Market

- Consumer Surplus

- Consumer Surplus Formula

- Correcting Externalities

- Deregulation of Markets

- Economics of Pollution

- Effects of Taxes and Subsidies on Market Structures

- Externalities

- Externalities and Public Policy

- Free Rider Problem

- Gains From Trade

- Government Failure

- Government Intervention in the Market

- How Markets Allocate Resources

- Imperfect Market

- Laffer Curve

- Market Failure

- Market Inefficiency

- Negative Externality

- Pigouvian Tax

- Positive Externalities

- Price Control on Market Structure

- Price Support

- Private Solutions to Externalities

- Privatisation Of Markets

- Producer Surplus

- Producer Surplus Formula

- Property Rights

- Public Goods

- Public Ownership

- Public Solutions to Externalities

- Public and Private Goods

- Regulation of Markets

- Social Benefits

- Social Costs

- Social Efficiency

- The Market Mechanism

- Tradable Pollution Permits

- Trade Policy

- Tragedy of the Commons

- Welfare in Economics

- Microeconomics Examples

- Perfect Competition

- Political Economy

- Poverty and Inequality

- Production Cost

- Supply and Demand

Jump to a key chapter

- John Maynard Keynes

Although some people, like John Maynard Keynes, search for facts and information, consumers generally do not have access or choose to ignore important information. This is known as the information problem. The information problem is a key reason behind why merit and demerit goods exist. Let’s study their characteristics.

The idea of merit good was coined by economist Richard Musgrave in the 1950s. He defined merit goods as commodities that individuals and society should be able to benefit from, regardless of their willingness and ability to pay.

What are merit goods?

Merit goods are goods or services that are considered to be beneficial to individuals and society as a whole, but are often under-consumed in a free market economy. These goods have positive effects on health, education, or the environment, but individuals may not consume them in optimal quantities.

Merit goods are goods for which the social benefits of consumption outweigh private benefits, as they are beneficial to both individuals and society as a whole.

Imagine that there is a town where most people drive cars to work every day, but there is also a good public transportation system available. The public transportation system is a merit good, as it has positive externalities such as reducing traffic congestion and air pollution, but many individuals may not use it due to lack of information. To encourage greater use of public transportation, the government could offer subsidies or other incentives to make it more attractive to consumers.

The classification of merit and demerit goods is based on value judgments.

Merit goods examples

Examples of merit goods include education, healthcare services, public transportation and renewable energy.

- Education is often considered a merit good because it provides benefits not just to the individual student, but also to society as a whole. Education can lead to higher levels of economic growth , increased civic engagement, and improved health outcomes.

- Access to healthcare services can improve the overall health of a population, which can lead to increased productivity and reduced healthcare costs over time. In addition, healthy individuals are better able to participate in the workforce and contribute to the economy.

- The use of renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower can help reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the negative effects of climate change. Investing in renewable energy can also create jobs and stimulate economic growth .

- Access to public transportation can reduce traffic congestion, air pollution, and travel costs, while also increasing mobility and access to job opportunities. This can lead to increased economic activity and a more connected and cohesive society.

The characteristics of merit goods

Let’s study the main characteristics of merit goods.

Merit goods and positive externalities

Consumption of merit goods benefits society as a whole. These benefits outweigh the private benefits enjoyed by the individual due to positive externalities .

Exploring the healthcare example in more detail, a consumer that consumes healthcare (merit good) also benefits the community, as they are less likely to spread diseases (positive externality). Therefore, the benefits to society outweigh the individual benefits. If healthcare was only provided privately, fewer people would benefit from it.

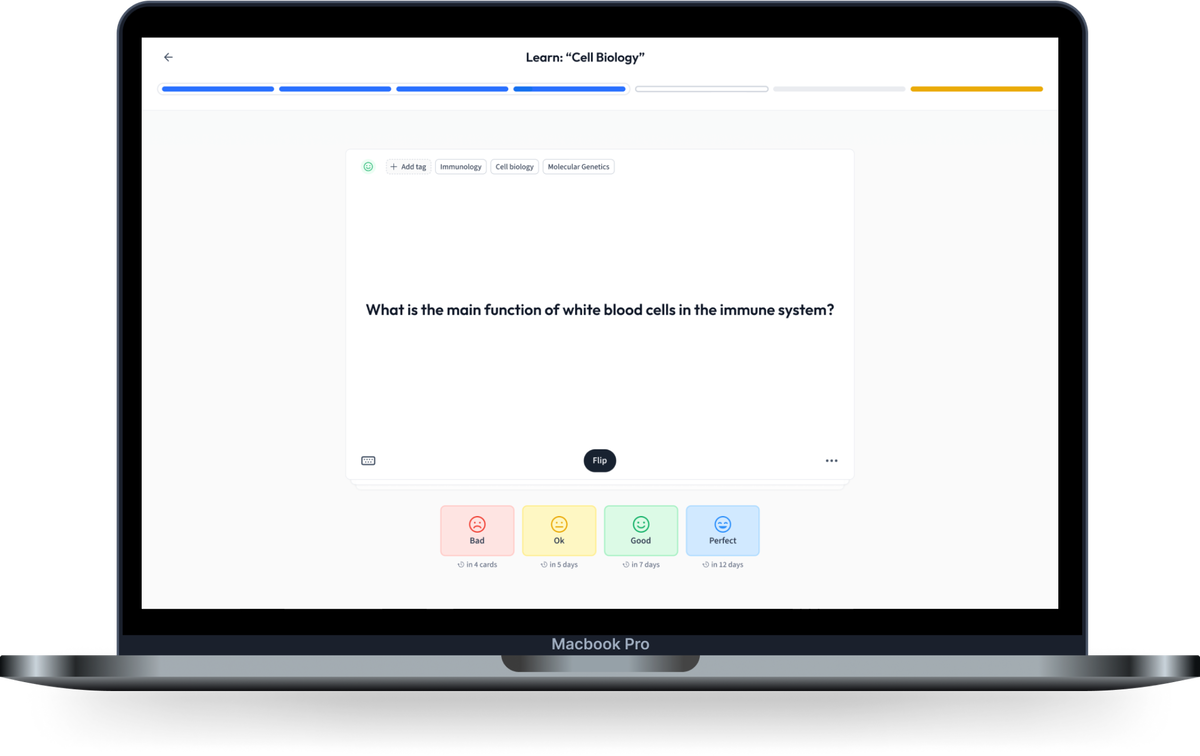

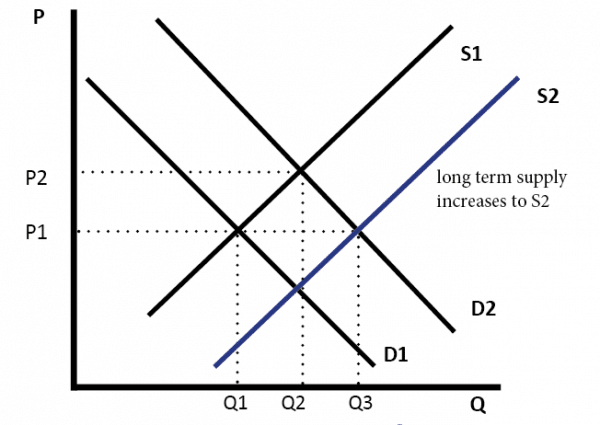

Let’s look at this example in a diagram. In Figure 1 below, S1 represents the market supply of healthcare. It represents the quantity of healthcare private healthcare providers are willing to supply at various price levels. D1 shows how much healthcare consumers are willing to buy. Q1 represents the quantity of private healthcare consumed at price P1.

On the other hand, D2 represents both the external benefits (positive externalities) and the individual benefits of consuming healthcare. Q2 shows the socially optimal level of healthcare, whereas Q1 shows the privately optimal level of healthcare. In the free market economy, the positive externalities of merit goods often go unnoticed, so consumption and production are under the socially optimal level.

The price of healthcare has to decrease to P2 in order to reach equilibrium at Q2. However, private suppliers are unwilling to supply at this price as it would decrease their profits significantly. T o increase the supply of healthcare to S2, governments subsidise it. The vertical distance between S1 and S2 represents the unit size of the subsidy.

Why are merit goods underprovided?

A merit good is under-provided and under-consumed because of the following factors:

- Imperfect Information : Consumers may not have access to all the information they need to make an informed decision about the benefits of the merit good, leading them to under-consume it.

- Presence of positive consumption externalities: The benefits of a merit good, such as education or healthcare, may extend beyond the individual who consumes it to society as a whole. However, these positive externalities are not factored into the individual's decision-making, resulting in an under-provision of the good.

- Poor decision-making : Individuals may prioritize short-term costs over long-term benefits, leading them to under-consume a merit good that would be beneficial in the long run. This can be exacerbated by factors such as income inequality, where individuals with lower incomes may prioritize immediate needs over long-term investments in merit goods such as education or healthcare.

What are demerit goods?

Demerit goods are the opposite of merit goods, as the social costs for the community are higher than the private costs for individual consumption. Private costs include the costs incurred by the individual for purchasing the good and the negative impact of the good on the individual. Social costs include the negative externalities that occur during the consumption of the good.

A demerit good is a good for which the social costs of consumption outweigh the private costs.

Social cost = external cost + private cost

Imagine that there is a town where there are many fast food restaurants, which offer unhealthy food options that can lead to health problems such as obesity and heart disease. Fast food is a demerit good, as it has negative externalities that impose costs on others beyond the individual consumer, such as increased healthcare costs. To discourage the over-consumption of fast food, the government could implement policies such as a tax on fast food or regulations requiring restaurants to offer healthier options.

Demerit goods examples

Examples of demerit goods that can have destructive impacts on individuals and society as a whole include alcohol, tobacco, fast-food, single-use plastics, and gambling.

- Tobacco products are widely recognized as a demerit good due to their negative effects on health, including an increased risk of lung cancer, heart disease, and other illnesses.

- Excessive consumption of alcohol can lead to a range of health problems, including liver disease, mental health issues, and an increased risk of accidents and injuries. Alcohol can also contribute to social problems such as violence and crime.

- Fast food and other high-calorie, low-nutrient foods are often considered demerit goods due to their contribution to obesity and related health problems. Overconsumption of these types of foods can also lead to increased healthcare costs and decreased productivity .

- Single-use plastics such as straws, bags, and packaging contribute to environmental pollution and harm wildlife. These plastics take hundreds of years to degrade and can end up in our oceans and waterways, causing serious harm to marine life.

- Gambling can be addictive and can lead to financial problems for individuals and their families. In addition, the promotion of gambling can lead to social issues such as crime and addiction.

The characteristics of demerit goods

Demerit goods and negative externalities.

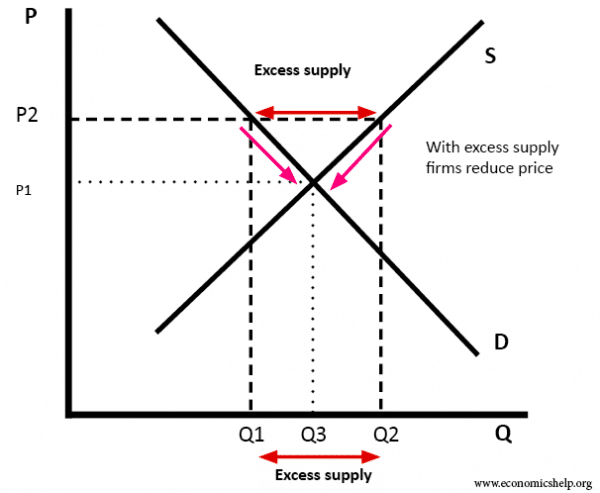

As we know, demerit goods create negative externalities. Looking at Figure 2 below, we can see that the sale of tobacco at market prices results in over-consumption. A privately optimal level of tobacco consumption happens at Q1, where prices are at P1. This is higher than the socially optimal level of tobacco consumption (Q2). Providing tobacco at free-market prices, therefore, results in overconsumption and overproduction.

As a result, governments can introduce taxes on the consumption of tobacco in an attempt to decrease the demand . This results in the supply curve shifting from S1 to S2, raising prices from P1 to P2 and allowing consumption to fall back to the socially optimal level. The vertical distance between S1 and S2 represents the unit size of the tax.

Tax on demerit goods

Taxation on demerit goods is a policy tool used by governments to discourage the consumption of goods that have negative externalities. The idea is that by increasing the price of demerit goods, individuals will be less likely to consume them and the negative externalities will be reduced. Here are some examples of taxes on demerit goods from different countries:

- Tobacco taxes i n the United States: The United States has one of the highest tobacco taxes in the world, with federal and state taxes accounting for over half the retail price of a pack of cigarettes. The aim of these taxes is to discourage smoking, which has been linked to a range of health problems. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, higher tobacco taxes have been shown to reduce smoking rates, particularly among youth.

- Alcohol taxes i n Canada: In Canada, each province and territory sets its own alcohol taxes, with rates varying widely across the country. The aim of these taxes is to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, which can lead to a range of health and social problems. According to a report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, higher alcohol prices have been linked to lower alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol-related problems.

- Plastic bag taxes in the United Kingdom: In 2015, the United Kingdom introduced a 5p (about 7 cents) tax on single-use plastic bags (increased to 10p in 2021) in an effort to reduce plastic waste.

Why are demerit goods overconsumed?

In the same way that merit goods are under-consumed, demerit goods are over-consumed. This is, again, due to imperfect information . Consumers often do not realise the extent of the harm caused by demerit goods which therefore leads to their over-consumption. Consumers also tend to ignore the negative externalities caused to society by consuming demerit goods.

In the early twentieth century, cigarettes were advertised as healthy and beneficial for certain health problems. This likely led to the overconsumption of cigarettes.

Merit goods, demerit goods, and value judgements

Value judgements are personal opinions that characterise what a particular person finds desirable or not.

Value judgments play a large role in determining which goods can be classified as merit and demerit goods. There are certain products that can clearly be defined as merit goods (like education and healthcare) and products that can clearly be defined as demerit goods (like tobacco and illegal drugs). However, due people’s different values and religions, there are certain goods for which the classification is not as easy. For example, some view contraception as a merit good and others as a demerit good. Therefore, the classification depends on the value judgment of the person making the classification.

Merit and Demerit Goods - Key takeaways

- Merit goods are goods for which the social benefits of consumption outweigh private benefits, whereas demerit goods are goods for which the social costs of consumption outweigh private costs.

- Merit goods are under-provided by markets .

- Healthcare and education are examples of merit goods.

- Demerit goods are over-consumed due to imperfect information .

- Examples of demerit goods include tobacco, alcohol and sugar.

- Demerit goods lead to negative externalities and are often taxed by the government.

- The information problem occurs when people make incorrect decisions as they do not have or choose to ignore important information.

- Value judgements are personal opinions that characterise what a particular person finds desirable or not. They play a large role in determining which goods are classified as merit and demerit goods.

Flashcards in Merit and Demerit Goods 1

positive externalities

Learn with 1 Merit and Demerit Goods flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Merit and Demerit Goods

What is the difference between demerit and merit?

Merit goods create social benefits, whereas demerit goods bring about social costs.

Which goods should be merit goods?

The question of which goods should be merit and demerit goods are based on value judgements, meaning it is up for interpretation. However, there are certain goods like healthcare and education that should be defined as merit goods.

Why do governments tax demerit goods?

Demerit goods create negative externalities. They are taxed since providing demerit goods at free-market prices would lead to their overconsumption and overproduction.

What is a merit and demerit good?

Merit goods are goods for which the social benefits of consumption outweigh private benefits, whereas a demerit good is a good for which the social costs of consumption outweigh private costs.

Discover learning materials with the free StudySmarter app

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Team Microeconomics Teachers

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB Guides

Market Failures, Public Goods, and Externalities

Definitions and Basics

Definition: Market failure , from Investopedia.com:

Market failure is the economic situation defined by an inefficient distribution of goods and services in the free market. Furthermore, the individual incentives for rational behavior do not lead to rational outcomes for the group. Put another way, each individual makes the correct decision for him/herself, but those prove to be the wrong decisions for the group. In traditional microeconomics, this is shown as a steady state disequilibrium in which the quantity supplied does not equal the quantity demanded….

Externalities , by Bryan Caplan, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Positive externalities are benefits that are infeasible to charge to provide; negative externalities are costs that are infeasible to charge to not provide. Ordinarily, as Adam Smith explained, selfishness leads markets to produce whatever people want; to get rich, you have to sell what the public is eager to buy. Externalities undermine the social benefits of individual selfishness. If selfish consumers do not have to pay producers for benefits, they will not pay; and if selfish producers are not paid, they will not produce. A valuable product fails to appear. The problem, as David Friedman aptly explains, “is not that one person pays for what someone else gets but that nobody pays and nobody gets, even though the good is worth more than it would cost to produce.”… Research and development is a standard example of a positive externality, air pollution of a negative externality….

Public Goods and Externalities , by Tyler Cowen, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Most economic arguments for government intervention are based on the idea that the marketplace cannot provide public goods or handle externalities . Public health and welfare programs, education, roads, research and development, national and domestic security, and a clean environment all have been labeled public goods…. Externalities occur when one person’s actions affect another person’s well-being and the relevant costs and benefits are not reflected in market prices. A positive externality arises when my neighbors benefit from my cleaning up my yard. If I cannot charge them for these benefits, I will not clean the yard as often as they would like. (Note that the free-rider problem and positive externalities are two sides of the same coin.) A negative externality arises when one person’s actions harm another. When polluting, factory owners may not consider the costs that pollution imposes on others….

Markets can fail if there are no property rights and negotiation is costly. The Coase Theorem: Ronald H. Coase , biography from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

“The Problem of Social Cost,” Coase’s other widely cited article (661 citations between 1966 and 1980), was even more path-breaking. Indeed, it gave rise to the field called law and economics. Economists b.c. (Before Coase) of virtually all political persuasions had accepted British economist Arthur Pigou’s idea that if, say, a cattle rancher’s cows destroy his neighboring farmer’s crops, the government should stop the rancher from letting his cattle roam free or should at least tax him for doing so. Otherwise, believed economists, the cattle would continue to destroy crops because the rancher would have no incentive to stop them. But Coase challenged the accepted view. He pointed out that if the rancher had no legal liability for destroying the farmer’s crops, and if transaction costs were zero, the farmer could come to a mutually beneficial agreement with the rancher under which the farmer paid the rancher to cut back on his herd of cattle. This would happen, argued Coase, if the damage from additional cattle exceeded the rancher’s net returns on these cattle. If for example, the rancher’s net return on a steer was two dollars, then the rancher would accept some amount over two dollars to give up the additional steer. If the steer was doing three dollars’ worth of harm to the crops, then the farmer would be willing to pay the rancher up to three dollars to get rid of the steer. A mutually beneficial bargain would be struck….

Public Goods , by Tyler Cowen, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Public goods have two distinct aspects: nonexcludability and nonrivalrous consumption. “Nonexcludability” means that the cost of keeping nonpayers from enjoying the benefits of the good or service is prohibitive. If an entrepreneur stages a fireworks show, for example, people can watch the show from their windows or backyards. Because the entrepreneur cannot charge a fee for consumption, the fireworks show may go unproduced, even if demand for the show is strong….

Protectionism , by Jagdish Bhagwati, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Underlying both cases is the assumption that free markets determine prices and that there are no market failures. But market failures can occur. A market failure arises, for example, when polluters do not have to pay for the pollution they produce. But such market failures or “distortions” can arise from governmental action as well. Thus, governments may distort market prices by, for example, subsidizing production, as European governments have done in aerospace, as many other governments have done in electronics and steel, and as all wealthy countries’ governments do in agriculture. Or governments may protect intellectual property inadequately, leading to underproduction of new knowledge; they may also overprotect it. In such cases, production and trade, guided by distorted prices, will not be efficient….

Market-clearing vs. sticky prices: New Keynesian Economics , by N. Gregory Mankiw, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

The primary disagreement between new classical and new Keynesian economists is over how quickly wages and prices adjust. New classical economists build their macroeconomic theories on the assumption that wages and prices are flexible. They believe that prices “clear” markets—balance supply and demand—by adjusting quickly. New Keynesian economists, however, believe that market-clearing models cannot explain short-run economic fluctuations, and so they advocate models with “sticky” wages and prices . New Keynesian theories rely on this stickiness of wages and prices to explain why involuntary unemployment exists and why monetary policy has such a strong influence on economic activity….

In the News and Examples

Is defense a public good? Defense , from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

National defense is a public good . That means two things. First, consumption of the good by one person does not reduce the amount available for others to consume. Thus, all people in a nation must “consume” the same amount of national defense (the defense policy established by the government). Second, the benefits a person derives from a public good do not depend on how much that person contributes toward providing it. Everyone benefits, perhaps in differing amounts, from national defense, including those who do not pay taxes. Once the government organizes the resources for national defense, it necessarily defends all residents against foreign aggressors….

Is education a public good? An Education in Market Failure , by Morgan Rose.

The most fundamental question raised by the school choice controversy is broader than education itself. Before we can confront the subject of the state’s role in education, we first ought to address the proper role and justification for government intervention in market activities in general…. One rationale that economists often use involves externalities and the problems that markets can have in coping with them. It might be clearer to explain what externalities are by first explaining why they sometimes cause problems for markets…

How do we determine when a market has really failed? And Is Market Failure a Sufficient Condition for Government Intervention? by Art Carden and Steven Horwitz.

Is the Occupy Wall Street movement about market failures, government failures, or both? Makers vs. Takers at Occupy Wall Street , a LearnLiberty video at Youtube.

Cathy O’Neil on Wall St and Occupy Wall Street . EconTalk podcast.

Cathy O’Neil, data scientist and blogger at mathbabe.org, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about her journey from Wall Street to Occupy Wall Street. She talks about her experiences on Wall Street that ultimately led her to join the Occupy Wall Street movement. Along the way, the conversation includes a look at the reliability of financial modeling, the role financial models played in the crisis, and the potential for shame to limit dishonest behavior in the financial sector and elsewhere.

Is smoking an example of a market failure? The Economics of Smoking , by Pierre Lemieux

After the economists’ analytical assault, the case for smoking regulations seemed pretty thin in the early 1990s. Then, a new argument was proposed by World Bank economist Howard Barnum. It relied on welfare economics, a field of neoclassical economic theory designed to show that “market failures,” created by external costs or other types of “externalities” (phenomena that bypass the market), prevent free markets from maximizing social welfare. The welfare-economics argument against smoking has since been refined by other economists working with the World Bank, and has provided the intellectual basis for the Bank’s 1999 report on the smoking “epidemic.”… The argument runs as follows. Smoking is not like other consumption choices, and the economic presumption of market efficiency does not apply. This is because, as the World Bank puts it, “many smokers are not fully aware of the high probability of disease and premature death,” and because of the addictive nature of tobacco.

Global warming and market failure. The Economics of Climate Change , by Robert P. Murphy

If the physical science of manmade global warming is correct, then policymakers are confronted with a massive negative externality. When firms or individuals embark on activities that contribute to greater atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, they do not take into account the potentially large harms that their actions impose on others. As Chief Economist of the World Bank Nicholas Stern stated in his famous report, climate change is “the greatest example of market failure we have ever seen.”…

Monopoly and market failure. Monopoly , by George Stigler, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

A famous theorem in economics states that a competitive enterprise economy will produce the largest possible income from a given stock of resources. No real economy meets the exact conditions of the theorem, and all real economies will fall short of the ideal economy–a difference called “market failure.”…

Externalities: When is a Potato Chip not Just a Potato Chip? a LearnLiberty video.

The Failure of Market Failure. Part I. The Problem of Contract Enforcement , by Anthony de Jasay

Received wisdom advances two broad reasons why government is entitled to impose its will on its subjects, and why the subjects owe it obedience, provided its will is exercised according to certain (constitutional) rules. One reason is rooted in production, the other in distribution–the two aspects of social cooperation. Ordinary market mechanisms produce and distribute the national income, but this distribution is disliked by the majority of the subjects (notably because it is ‘too unequal’) and it is for government to redistribute it (making it more equal or bend it in other ways, a function that its partisans prefer to call ‘doing social justice’). However, the market is said to be deficient even at the task of producing the national income in the first place. Government is needed to overcome market failure. A society of rational individuals would grasp this and readily mandate the government to do what was needful (e.g. by taxation, regulation and policing) to put this right….

The Failure of Market Failure. Part II. The Public Goods Dilemma , by Anthony de Jasay

Public goods are freely accessible to all members of a given public, each being able to benefit from it without paying for it. The reason standard theory puts forward for this anomaly is that public goods are by their technical character non-excludable. There is no way to exclude a person from access to such a good if it is produced at all. Examples cited include the defence of the realm, the rule of law, clean air or traffic control. If all can have it without contributing to its cost, nobody will contribute and the good will not be produced. This, in a nutshell, is the public goods dilemma, a form of market failure which requires taxation to overcome it. Its solution lies outside the economic calculus; it belongs to politics….

Moral externalities and markets. Satz on Markets . EconTalk podcast.

Debra Satz, Professor of Philosophy at Stanford University, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about her book, Why Some Things Should Not Be For Sale: The Moral Limits of the Market. Satz argues that some markets are noxious and should not be allowed to operate freely. Topics discussed include organ sales, price spikes after natural disasters, the economic concept of efficiency and utilitarianism. The conversation includes a discussion of the possible limits of political intervention and whether it would be good to allow voters to sell their votes….

Is price gouging justifiable? Munger on John Locke, Prices, and Hurricane Sandy . EconTalk Podcast.

Mike Munger of Duke University talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about the gas shortage following Hurricane Sandy and John Locke’s view of the just price. Drawing on a short, obscure essay of Locke’s titled “Venditio,” Munger explores Locke’s views on markets, prices, and morality.

A Little History: Primary Sources and References

John Maynard Keynes , biography from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

… Why shouldn’t government, thought Keynes, fill the shoes of business by investing in public works and hiring the unemployed? The General Theory advocated deficit spending during economic downturns to maintain full employment.

Ronald Coase on Externalities, the Firm, and the State of Economics . EconTalk Podcast, May 2012.

Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase of the University of Chicago talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about his career, the current state of economics, and the Chinese economy. Coase, born in 1910, reflects on his youth, his two great papers, “The Nature of the Firm” and “The Problem of Social Cost”. At the end of conversation he discusses his new book on China, How China Became Capitalist (co-authored with Ning Wang), and the future of the Chinese and world economies.

Did Markets Fail in Post-Soviet Economies? , a LearnLiberty video.

Prof. Pavel Yakovlev argues that capitalism, to the extent that it has been tried, has improved post-Soviet economies.

Advanced Resources

The Demand and Supply of Public Goods , by James M. Buchanan.

People are observed to demand and to supply certain goods and services through market institutions. They are observed to demand and to supply other goods and services through political institutions. The first are called private goods; the second are called public goods…. Neoclassical economics provides a theory of the demand for and the supply of private goods. But what does “theory” mean in this context? This question can best be answered by examining the things that theory allows us to do. Explanation is the primary function of theory, here as everywhere else. For the private-goods world, economic theory enables us to take up the familiar questions: What goods and services shall be produced? How shall resources be organized to produce them? How shall final goods and services be distributed? Note, however, that theory here does not provide the basis for specific forecasts. Instead, it allows us to develop an explanation of the structure of the system, the inherent logical structure of the decision processes. With its help we understand and explain how such decisions get made, not what particular pattern of outcome is specifically chosen….

The Reason of Rules: Constitutional Political Economy , by Geoffrey Brennan and James M. Buchanan.

Since we are ourselves professional economists, we have been particularly mystified by the reluctance of our profession to adopt what we have called the constitutional perspective. Economists in this century have been greatly concerned with “market failure,” which was the central focus of the theoretical welfare economists that dominated economic thought during the middle decades of the century. This market-failure emphasis extended to both micro- and macro-levels of analysis. Scholars working at either of these levels showed no reluctance in proffering advice to governments on detailed market correctives and macroeconomic management. In retrospect, post-public choice, it seems strange that these scholars so rarely showed a willingness to apply their analytic apparatus to institutions other than the market; they paid almost no attention to politics and political institutions. Once a policy recommendation seemed to have emerged from their market-failure analytics, there was no subsequent analysis aimed at proving that persons in their political roles, as either principals or agents, would somehow behave as the economists’ precepts dictated. Implicitly, economists seemed locked into the presumption that political authority is vested in a group of moral superpersons, whose behavior might be described by an appropriately constrained social welfare function. Initial cursory attempts by a few public-choice pioneers to inject a bit of practical realism into our models of individual behavior in politics were subjected to charges of ideological bias. The myth of the benign despot seems to have considerable staying power, a phenomenon that we examine specifically in Chapter 3….

Related Topics

Supply and Demand, Markets and Prices

Roles of Government

Property Rights

Government Failures, Rent Seeking, and Public Choice

What is the role of markets in an economy?

Markets are places where buyers and sellers can meet to sell and purchase goods and services.

- Markets provide places for firms to sell their goods and gain revenue.

- Markets provide places for consumers to buy the goods and services that they need.

Markets are mostly self-regulated, relying on the principles of supply and demand to determine prices.

Why markets are important

1. Ration scarcity . Suppose a good is becoming scarce and close to running out, then the supply of the good will fall. Causing the price to rise.

The rise in price will deter consumers from buying and encourage them to look for alternatives. Also, as prices rise, it will provide incentives for firms to either find new supplies or create suitable alternatives. For example, if a new pest destroys wheat crops, the price of wheat will rise encouraging consumers to find alternatives like barley and rice. In the long-term, farmers will seek alternatives to wheat or new production methods that avoid the crop

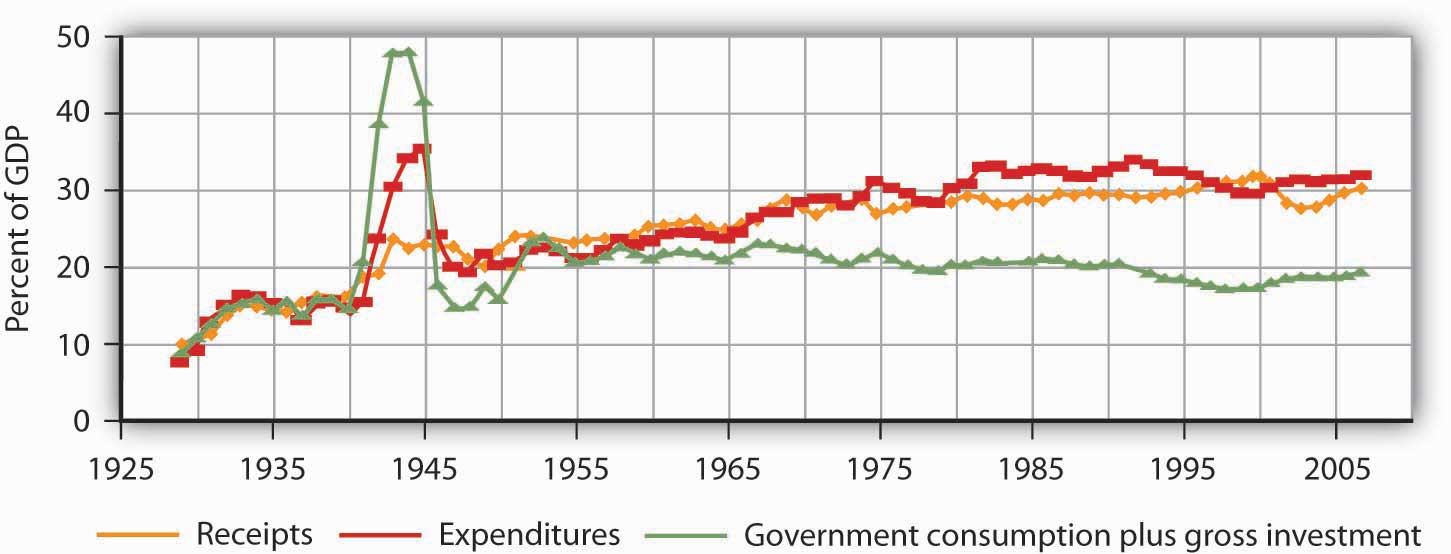

2. Incentives . Markets create incentives for firms to respond to shortages and surpluses. Suppose a good becomes very popular, market forces will push up prices to P2.

However, this higher price acts as a signal for firms to increase supply to S2 – so other time the market responds to this change in demand. For example, in recent years, there has been growing demand for lithium batteries, this creates incentives for firms to build new lithium mines to meet growing demand.

For example, suppose there was excess supply of a good, such as rental housing. In the below case there are houses unoccupied.

Market forces will cause prices to fall. Firms cut the price of renting until they have let out their housing.

4. Efficiency . When a market is functioning properly, then consumers will have a choice about where to buy their goods and services. If one firm allows costs to rise or provides sub-standard services, then it will become unprofitable and go out of business. Therefore, in a market economy, there is a strong incentive for firms to be efficient, cut costs and offer a good service to consumer.

5. Consumer choice . Without markets, consumers would struggle to get the goods and services they need. Markets enable consumers to choose the cheapest (or best) product, leading to a greater range of choices. New markets can continually spring up offering consumers choices there were not aware of.

Types of markets

- Physical market. A traditional marketplace is a physical location where sellers and buyers can set up their stalls or shops.

- Global market. When markets have international sellers and international buyers, e.g. going to buy car, you can buy imports from abroad or Currency markets, where you can easily buy from a dealer in any country.

- Virtual markets. Increasingly the market is online with consumers able to visit sellers through the computer and internet. This has made markets more global.

Limitations of markets

- Public goods are not provided because there is no profit incentive to provide goods, which is difficult for firms to charge, e.g. street lighting is not practical because of who would pay towards it. If it is provided, consumers could free-ride (enjoy without paying) Other important public goods not provided by free market, include legal system, law and order and protection of private property.

- Externalities . A market is efficient at allocating resources if the costs are met by firm and consumer. However, many goods and services create external costs to other people in society. For example, when you generate coal-powered electricity, there are very substantial costs of pollution, global warming – for people around the globe. In a market, this external cost is not included in the price and so we get over-consumption of these goods with negative externalities.

- Positive externalities . Similarly, goods which have significant positive externality may be under-provided and under-consumed.

- Merit/demerit goods . These are goods where consumers may make poor choices due to lack of information or irrational behaviour. For example, addictive goods like smoking and gambling – in a free market, consumers may get caught in addictive consumption which reduces their personal welfare.

- Inequality . Markets provide goods and services – so long as people can afford them. If people are unemployed or have no income, then they may lack basic necessities because they can’t afford them. Inequality in a free market can increase because of monopoly power, monopsony employers, inherited wealth and unequal opportunities.

- Monopolies tend to work inefficiently . A firm with monopoly power can set high prices and not be subject to the same competitive pressures.

How to make markets work better

- Internalise externalities. A Pigovian tax makes consumers pay the full social cost of a good, rather than just a private cost, e.g. carbon tax .

- Government provision of public goods

- Remove monopoly power by encouraging competition

- Avoid unnecessary bureaucracy and red-tape.

Alternatives to markets

One thing about markets is that it is often hard to envisage any alternative. The two main options could be

- Gift-giving economy . Anthropologists state in some communities, there are not the same market forces. People contribute to the community and are happy to give excess wealth and food to those in need. There is an expectation that the ‘favour’ will be returned.

- Utopian socialism. Similar to the gift-giving economy is the ideals of ‘utopian socialism’ where people work for the common good and resources and distributed according to need.

- Centrally planned economy . Under communism in Soviet Union, the economy was arranged by central planning with planners deciding what to produce and who should get it. The aim was to create equality, but it also led to inefficiency, shortages and surpluses and inflexibility.

There are many limitations of markets, however, they can be part of the solution towards economic development and providing decent living standards. The economist Greg Mankiw’s sixth principle of economics is Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity.

Most economists would agree with this to some extent. If only because there are few practical alternatives. However, very few economists would argue we should just rely on markets. There needs to be a balance with government intervention dealing with the worst excess of the markets, such as inequality and externalities.

Essay Curve

Essay on Market – 10 Lines, 100, 200, 500, 1500 Words

Essay on Market: The market is a bustling hub of activity where goods and services are bought and sold, creating a dynamic ecosystem of supply and demand. In this essay, we will explore the various aspects of the market, from its role in the economy to the impact of consumer behavior on pricing. We will also delve into the different types of markets, such as perfect competition and monopolies, and analyze their effects on both businesses and consumers. Join us as we unravel the complexities of the market in this insightful essay.

Table of Contents

Market Essay Writing Tips

1. Start by choosing a specific market to focus on. This could be a physical market, such as a farmer’s market or flea market, or a virtual market, such as an online marketplace like Amazon or eBay.

2. Begin your essay with an introduction that provides an overview of the market you will be discussing. Include information about its location, size, and the types of products or services that are sold there.

3. Research the history of the market to provide context for your essay. This could include information about when the market was established, how it has evolved over time, and any significant events or changes that have occurred.

4. Describe the layout and organization of the market. Discuss how vendors are arranged, what types of stalls or booths are used, and any unique features that set the market apart from others.

5. Provide details about the products or services that are available at the market. This could include information about the variety of goods sold, the quality of the products, and any specialties or unique items that are offered.

6. Discuss the atmosphere and experience of shopping at the market. Describe the sights, sounds, and smells that visitors might encounter, as well as any cultural or social aspects of the market that make it a unique and interesting place to visit.

7. Consider the economic impact of the market on the local community. Discuss how the market supports small businesses, creates jobs, and contributes to the overall economy of the area.

8. Explore the role of technology in the market, if applicable. Discuss how online marketplaces have changed the way people buy and sell goods, and how traditional markets are adapting to compete in the digital age.