English Grammar Zone

Essay on The Effects of Global Warming

Every action has a consequence” is a saying that helps us understand why our actions matter, especially when it comes to protecting our planet. Global warming is the result of human actions, such as burning fossil fuels, that release harmful gases into the air. These gases trap heat, warming the Earth. This warming has serious effects on nature and our lives. In this article, we will learn how to write an essay or a paragraph on “The Effects of Global Warming” in English (10-line essay, short essay & long essay for children). Let’s start.

Short Essay on The Effects of Global Warming for Kids

Global warming is causing many changes on Earth. One of the most visible effects is the melting of ice in places like the Arctic. As the planet gets hotter, ice in glaciers and at the poles melts. This is bad for animals like polar bears and seals that live on the ice. They are losing their homes because the ice is disappearing.

The melting ice also causes the sea levels to rise . When ice melts, it adds more water to the oceans. Rising sea levels can flood cities and towns near the coast. It also makes storms stronger, putting people and homes at risk.

Global warming also affects the weather . Some places are getting hotter, while others experience stronger storms and floods. There are more heatwaves and droughts, which make it hard for plants and animals to survive.

Although we cannot completely stop global warming, we can slow it down. By using clean energy , planting trees, and reducing waste, we can make a difference. Recycling , saving water, and turning off lights when not needed are small actions that help.

It is important to act now to protect the planet for future generations. If we work together, we can reduce the effects of global warming and keep the Earth safe for all living things.

Long Essay on The Effects of Global Warming for Children

Global warming is causing many changes that affect life on Earth. One of the major effects is the melting of ice . As the Earth’s temperature rises, ice at the North and South Poles and in glaciers around the world begins to melt. This ice has been there for thousands of years, and its melting is causing problems. Polar bears , penguins, and other animals that rely on ice for hunting and shelter are losing their homes. They have to travel further to find food, which makes their survival difficult.

The melting ice also causes the sea level to rise . When the ice melts, it turns into water that flows into the oceans. This extra water raises the level of the sea. Rising sea levels are dangerous for people living in coastal cities and towns. Flooding becomes more common, and strong storms, like hurricanes, become even more dangerous when the sea level is higher. This means more homes, schools, and businesses could be destroyed by floods.

Another effect of global warming is that it changes the weather . We are seeing more extreme weather events, like heatwaves, droughts, and stronger storms. In some places, it gets hotter than usual, while in others, there is too much rain or even snow. These changes are making it harder for farmers to grow food, and many plants and animals are struggling to survive in the changing climate.

Although we cannot completely stop global warming, we can take steps to slow it down. We can use clean energy like wind and solar power instead of burning coal or oil, which releases harmful gases into the air. Planting trees is another way to help because trees take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen. We should also reduce, reuse, and recycle to cut down on waste. Simple actions like saving water, using less electricity, and choosing environmentally friendly products can help.

In conclusion, global warming is affecting the entire planet in dangerous ways. Ice is melting, sea levels are rising, and the weather is becoming more extreme. But if we act now and make better choices, we can reduce the effects of global warming. By working together, we can help protect our planet for future generations and all the creatures that call Earth home.

10-Line Essay on The Effects of Global Warming

- Global warming is making the Earth hotter.

- The ice in the Arctic and Antarctic is melting.

- Polar bears and seals are losing their homes.

- Rising sea levels are flooding cities.

- Global warming makes storms stronger.

- The weather is changing with more heatwaves.

- Some places are getting more rain and floods.

- We can slow global warming by using clean energy.

- Recycling and planting trees also help.

- Everyone must act to save the planet.

Summary of The Effects of Global Warming for Children

Global warming is making the Earth hotter and causing many changes. Ice is melting, which leads to rising sea levels and flooding in coastal cities. Animals like polar bears are losing their homes. The weather is becoming more extreme with more heatwaves, storms, and floods. We can slow global warming by using clean energy, recycling, and planting trees. It’s important to act now to protect the Earth for future generations.

FAQs on The Effects of Global Warming

- What is melting ice in global warming? Melting ice refers to the glaciers and polar ice caps at the North and South Poles melting due to rising global temperatures. This ice, which has existed for thousands of years, is melting faster than ever because of global warming. When this ice melts, it causes sea levels to rise, affecting coastal areas and wildlife.

- Why are animals losing their homes because of global warming? Animals like polar bears, seals, and penguins depend on ice to hunt and live. When the ice melts due to global warming, these animals have less space to hunt for food and build homes. As a result, they struggle to survive and may face extinction if the ice continues to disappear.

- What is rising sea level and why is it dangerous? Rising sea levels occur when ice from glaciers and polar regions melts, adding more water to the oceans. This can flood coastal cities and towns, destroy homes, and displace millions of people. It also increases the risk of stronger storms, making areas more vulnerable to extreme weather.

- How does global warming change our weather? Global warming causes changes in weather patterns, making some areas hotter and others wetter or drier. This leads to more extreme weather events like heatwaves, stronger storms, droughts, and floods. These changes affect agriculture, water supply, and make natural disasters more dangerous.

- Can we stop global warming completely? While we cannot completely stop global warming, we can slow it down by using clean energy sources like solar and wind power, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and planting trees. By making environmentally friendly choices, we can reduce the harmful effects of global warming and protect the planet for future generations.

Related Posts

Newspaper vocabulary words with meaning.

Newspaper Vocabulary List Newspaper vocabulary plays a crucial role in helping readers navigate the world of journalism. As a primary source of

Essay on My Village for Children

Introduction to My Village “A village is a peaceful place where nature and people live together.” This is a common saying that

Paragraph on Clean India, Green India (100,150,200,250 And 300 words)

Once upon a time in a small village, there was a group of friends named Rina, Raj, and Maya. They loved playing

Essay on Value of Parents for Children

Parents are like the roots of a tree. They help us grow strong and reach high.” Parents are the most important people

Recent Posts

100 examples of masculine and feminine gender, gender in english, essay on global warming for children.

- 10 Lines (41)

- Abbreviation (2)

- active / Passive (3)

- adjectives (23)

- adverbs (24)

- American Vs British (3)

- Another Way to Say (68)

- Basic Grammar for beginner (13)

- Brain Teasers (35)

- Business English (4)

- Business Word (3)

- Clauses (7)

- Collective Nouns (5)

- Collocations (1)

- Common Mistakes (7)

- Communication (4)

- Complex Sentence (4)

- Compound Sentences (2)

- Concrete Noun (2)

- Conditionals (5)

- conjunctions (27)

- Determiners (5)

- Dialogue (2)

- Direct and Indirect (6)

- English Exercises (31)

- English Phrases (43)

- English Riddles (11)

- Expressions (7)

- For Spoken English (196)

- Grammar (452)

- Homophones (3)

- Idioms (16)

- Interjection (1)

- Knowledge Base (56)

- Miscellaneous (22)

- Modals (10)

- Opposite Word (24)

- Paragraph (182)

- Parts of Speech (65)

- Personal Questions (6)

- Phrasal Verbs (6)

- Phrases (2)

- Prepositions (28)

- Pronouns (20)

- Proverb (3)

- Punctuation (2)

- Question Words (2)

- Reading comprehension worksheet (20)

- Reported Speech (1)

- Sentences (56)

- Speaking English (9)

- Synonyms – Antonyms (12)

- Tag Question (2)

- Tenses (31)

- Uncategorized (70)

- Vocabulary (49)

- WH Question Words (1)

- Word Family list (26)

- Worksheets (288)

Welcome to the English Grammar Zone! Here, you’ll find everything you need to know about grammar.

Top Categories

Quick links, subscribe now.

English Grammar Zone Copyright © 2024

Band 8+: Global warming is one of the biggest threats to our environment. What cause of global warming and solutions are there

Global warming is one of the biggest problems that affect the environment. So what is global warming? It is defined as an increase in temperature due to air pollution. It causes serious consequences for humans as well as other species. In this essay, I will explain more clearly the cause and solution to this problem.

Firstly, the burning of fossil fuels appears to be one of the main causes of global warming. Burning fossil fuels releases gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (NH4) into the environment. For example, the large number of vehicles on the road, such as cars and motorcycles running on fossil fuels, emit terrible amounts of emissions, such as carbon dioxide, which creates greenhouse gases and causes the temperature on Earth to increase. Besides, factories also release into the environment often toxic emissions such as CO2, H2S, and CO. It can be harmful to human health and the environment. For example, according to a report from the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the thermal power industry is one of the industries with the largest emissions, followed by the petrochemical industry, coal mining, and metallurgy industries. These industries all emit large amounts of toxic emissions into the environment. The second cause is deforestation. This is because as the population increases, the need for housing and food sources becomes urgent. The General Department of Forestry has statistics that: On average, each year the forest area in our country decreases by 2,430 hectares. Trees help absorb CO2 and produce O2, making the air fresh. However, cutting down trees has resulted in less absorption of air pollutants. For example, there is an article claiming that CO2 levels have increased significantly due largely to deforestation and factory operations.Using too many electronic devices is also one of the main causes. Life is increasingly developing, and the need to use smart electronic devices is increasing. However, most such products emit CFCs and other carbon gases. For example, older-generation refrigerators often contain substances such as CFCs or HCFCs, which are volatile, toxic liquids and gases that cause ozone layer depletion. According to a report from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, refrigerators and air conditioners often contain HFC gas, which causes the greenhouse effect and can increase global warming by 12–14.8 times CO2 gas. If these electronic devices are broken or not used, they will be thrown away in the environment, causing the amount of “electronic waste” to increase. It will lead to ozone layer depletion, worsening the greenhouse effect and global warming.

One solution that is proving successful is the use of transportation solutions. Do not use cars or personal motorbikes that run on gasoline or diesel, but instead use bicycles, electric vehicles, or public transport. For example, affordable electric cars and electric motorcycles from Vinfast are appearing on the market. Not using vehicles powered by fossil fuels will reduce emissions into the environment. For example, in the Netherlands, using bicycles for 25% of daily travel needs reduces CO2 emissions equivalent to planting 54 million new trees each year. As a result, the air in the Netherlands is clean, and substances that cause climate change are not found. Another effective solution is forest management. This is the easiest way to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Each individual can plant trees in the house, yard, or sidewalk, or the government can control deforestation, manage the number of existing forests, increase mobilization of forces to plant more trees, and delineate areas of land to plant trees. For example, the government has deployed the directive “Program to plant 1 billion new trees” for agencies, organizations, and individuals to jointly implement or the program “Planting trees to create forests” for students at schools in Ho Chi Minh City. Trees can absorb carbon dioxide. On average, 2 hectares of large foliage trees can absorb tons of carbon dioxide per day and release 730 kg of oxygen. The amount of carbon dioxide emitted by 1 person in 1 day will be absorbed by 10 square meters of trees. Finally, it is to encourage people to use renewable and non-polluting energy sources such as wind and solar energy. Countries such as Denmark and Germany have invested significantly in wind energy, reducing their dependence on fossil fuels. Electricity can be generated through windmills or solar energy. For example, in Bac Lieu, there is a very famous place called “Windmill Wing” with giant wind turbines. It helps create electricity for the entire West. The government also needs to educate people about the positive benefits of solar energy by providing free panels or encouraging factories to install solar panels. In addition, people should consciously reduce the use of fossil fuels to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reduce the impact of global warming.

In conclusion, global warming has become an urgent issue for many countries, including Vietnam. Its main causes are fossil fuel consumption, deforestation, and using many electronic devices. In this article, the solutions for the issue have been proposed in three parts: using renewable energy, forest management, and use of transportation solutions. Governments and all citizens need to join hands to make a more “green” environment, contributing to reducing global warming.

Check Your Own Essay On This Topic?

Generate a band-9 sample with your idea, overall band score, task response, coherence & cohesion, lexical resource, grammatical range & accuracy, other topics:, with deforestation, urban development and illegal hunting, many animal species are becoming endangered and some are even facing extinction. do you think it is important to protect animals what can be done to deal with this problem.

The rising threat of cutting trees, urban development, and poaching led to significant issues which is that numerous of animal species are now on the brink of extinction. Protecting animal species is not only important for maintaining the ecological cycle, but also it contributes to the flourishing of the economy. This essay will shed the […]

To learn effectively, children need to eat a healthy meal at school. How true is statement? Whose responsibility is it provide food for school children?

In today’s world, students should consume hygienic and nutritious food at school, as this is essential for effective learning. I firmly believe that this statement is true because healthy meals enable pupils to concentrate better in class. To achieve this, the government should ensure the provision of such meals. Nutritious foods contain a variety of […]

the use of gamification in language learning is beneficial. Do you agree or disagree?

Gamification is a type of teaching lessons to the students in an interesting way or motivating children by using game-like elements, such as points, rewards, and challenges to enhance engagements at the lesson time. Recently, this method has gained large popularity in education, especially in learning language. I strongly believe that gamification is so beneficial […]

Gamification reflects the use of game-like elements, challenges and rewards to enhance passion and motivation during lesson. It has gained popularity among the people in their education particularly language learning. I firmly agree with idea that it not only improves students’ social skills but also encourages students to achieve breakthroughs. Firstly, gamification is a one […]

In today’s world, students should consume a hygienic and nutritious food at school, which helps them get into an effective learning process. I vehemently believe that this statement is true because pupils can concentrate better after eating healthy meals. To guarantee this purpose, the government should facilitate those foods. Nutritious foods contain a variety of […]

In some areas of the US, a 'curfew' is imposed, in which teenagers are not allowed to be out of doors after a particular time at night unless they are accompanied by an adult.

In some cities of Kazakhstan after a certain time teenagers can not go outdoor, unless they are with a grown-up. I totally agree with that because after 11pm in the streets is too dangerous for teenagers between 13 and 18 years old. Moreover, most of them are irresponsible when it comes to make a decision. […]

Plans & Pricing

- ENVIRONMENT

What is global warming, explained

The planet is heating up—and fast.

Glaciers are melting , sea levels are rising, cloud forests are dying , and wildlife is scrambling to keep pace. It has become clear that humans have caused most of the past century's warming by releasing heat-trapping gases as we power our modern lives. Called greenhouse gases, their levels are higher now than at any time in the last 800,000 years .

We often call the result global warming, but it is causing a set of changes to the Earth's climate, or long-term weather patterns, that varies from place to place. While many people think of global warming and climate change as synonyms , scientists use “climate change” when describing the complex shifts now affecting our planet’s weather and climate systems—in part because some areas actually get cooler in the short term.

Climate change encompasses not only rising average temperatures but also extreme weather events , shifting wildlife populations and habitats, rising seas , and a range of other impacts. All of those changes are emerging as humans continue to add heat-trapping greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, changing the rhythms of climate that all living things have come to rely on.

What will we do—what can we do—to slow this human-caused warming? How will we cope with the changes we've already set into motion? While we struggle to figure it all out, the fate of the Earth as we know it—coasts, forests, farms, and snow-capped mountains—hangs in the balance.

Understanding the greenhouse effect

The "greenhouse effect" is the warming that happens when certain gases in Earth's atmosphere trap heat . These gases let in light but keep heat from escaping, like the glass walls of a greenhouse, hence the name.

Sunlight shines onto the Earth's surface, where the energy is absorbed and then radiate back into the atmosphere as heat. In the atmosphere, greenhouse gas molecules trap some of the heat, and the rest escapes into space. The more greenhouse gases concentrate in the atmosphere, the more heat gets locked up in the molecules.

YEAR-LONG ADVENTURE for every explorer on your list

Scientists have known about the greenhouse effect since 1824, when Joseph Fourier calculated that the Earth would be much colder if it had no atmosphere. This natural greenhouse effect is what keeps the Earth's climate livable. Without it, the Earth's surface would be an average of about 60 degrees Fahrenheit (33 degrees Celsius) cooler.

A polar bear stands sentinel on Rudolf Island in Russia’s Franz Josef Land archipelago, where the perennial ice is melting.

In 1895, the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius discovered that humans could enhance the greenhouse effect by making carbon dioxide , a greenhouse gas. He kicked off 100 years of climate research that has given us a sophisticated understanding of global warming.

Levels of greenhouse gases have gone up and down over the Earth's history, but they had been fairly constant for the past few thousand years. Global average temperatures had also stayed fairly constant over that time— until the past 150 years . Through the burning of fossil fuels and other activities that have emitted large amounts of greenhouse gases, particularly over the past few decades, humans are now enhancing the greenhouse effect and warming Earth significantly, and in ways that promise many effects , scientists warn.

Aren't temperature changes natural?

Human activity isn't the only factor that affects Earth's climate. Volcanic eruptions and variations in solar radiation from sunspots, solar wind, and the Earth's position relative to the sun also play a role. So do large-scale weather patterns such as El Niño .

You May Also Like

How global warming is disrupting life on Earth

Air pollution, explained

These photos show what happens to coral reefs in a warming world

But climate models that scientists use to monitor Earth’s temperatures take those factors into account. Changes in solar radiation levels as well as minute particles suspended in the atmosphere from volcanic eruptions , for example, have contributed only about two percent to the recent warming effect. The balance comes from greenhouse gases and other human-caused factors, such as land use change .

The short timescale of this recent warming is singular as well. Volcanic eruptions , for example, emit particles that temporarily cool the Earth's surface. But their effect lasts just a few years. Events like El Niño also work on fairly short and predictable cycles. On the other hand, the types of global temperature fluctuations that have contributed to ice ages occur on a cycle of hundreds of thousands of years.

For thousands of years now, emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere have been balanced out by greenhouse gases that are naturally absorbed. As a result, greenhouse gas concentrations and temperatures have been fairly stable, which has allowed human civilization to flourish within a consistent climate.

Greenland is covered with a vast amount of ice—but the ice is melting four times faster than thought, suggesting that Greenland may be approaching a dangerous tipping point, with implications for global sea-level rise.

Now, humans have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by more than a third since the Industrial Revolution. Changes that have historically taken thousands of years are now happening over the course of decades .

Why does this matter?

The rapid rise in greenhouse gases is a problem because it’s changing the climate faster than some living things can adapt to. Also, a new and more unpredictable climate poses unique challenges to all life.

Historically, Earth's climate has regularly shifted between temperatures like those we see today and temperatures cold enough to cover much of North America and Europe with ice. The difference between average global temperatures today and during those ice ages is only about 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius), and the swings have tended to happen slowly, over hundreds of thousands of years.

But with concentrations of greenhouse gases rising, Earth's remaining ice sheets such as Greenland and Antarctica are starting to melt too . That extra water could raise sea levels significantly, and quickly. By 2050, sea levels are predicted to rise between one and 2.3 feet as glaciers melt.

As the mercury rises, the climate can change in unexpected ways. In addition to sea levels rising, weather can become more extreme . This means more intense major storms, more rain followed by longer and drier droughts—a challenge for growing crops—changes in the ranges in which plants and animals can live, and loss of water supplies that have historically come from glaciers.

Related Topics

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

- CLIMATE CHANGE

What does a melting glacier sound like? 'Gunshots.'

The Gulf of Maine is warming fast. What does that mean for lobsters—and everything else?

See what a year looks like in the fastest-warming place on Earth

Sea levels are rising at an extraordinary pace. Here's what to know.

What is the ozone layer, and why does it matter?

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Share full article

The Science of Climate Change Explained: Facts, Evidence and Proof

Definitive answers to the big questions.

Credit... Photo Illustration by Andrea D'Aquino

Supported by

By Julia Rosen

Ms. Rosen is a journalist with a Ph.D. in geology. Her research involved studying ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to understand past climate changes.

- Published April 19, 2021 Updated Nov. 6, 2021

The science of climate change is more solid and widely agreed upon than you might think. But the scope of the topic, as well as rampant disinformation, can make it hard to separate fact from fiction. Here, we’ve done our best to present you with not only the most accurate scientific information, but also an explanation of how we know it.

How do we know climate change is really happening?

How much agreement is there among scientists about climate change, do we really only have 150 years of climate data how is that enough to tell us about centuries of change, how do we know climate change is caused by humans, since greenhouse gases occur naturally, how do we know they’re causing earth’s temperature to rise, why should we be worried that the planet has warmed 2°f since the 1800s, is climate change a part of the planet’s natural warming and cooling cycles, how do we know global warming is not because of the sun or volcanoes, how can winters and certain places be getting colder if the planet is warming, wildfires and bad weather have always happened. how do we know there’s a connection to climate change, how bad are the effects of climate change going to be, what will it cost to do something about climate change, versus doing nothing.

Climate change is often cast as a prediction made by complicated computer models. But the scientific basis for climate change is much broader, and models are actually only one part of it (and, for what it’s worth, they’re surprisingly accurate ).

For more than a century , scientists have understood the basic physics behind why greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide cause warming. These gases make up just a small fraction of the atmosphere but exert outsized control on Earth’s climate by trapping some of the planet’s heat before it escapes into space. This greenhouse effect is important: It’s why a planet so far from the sun has liquid water and life!

However, during the Industrial Revolution, people started burning coal and other fossil fuels to power factories, smelters and steam engines, which added more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Ever since, human activities have been heating the planet.

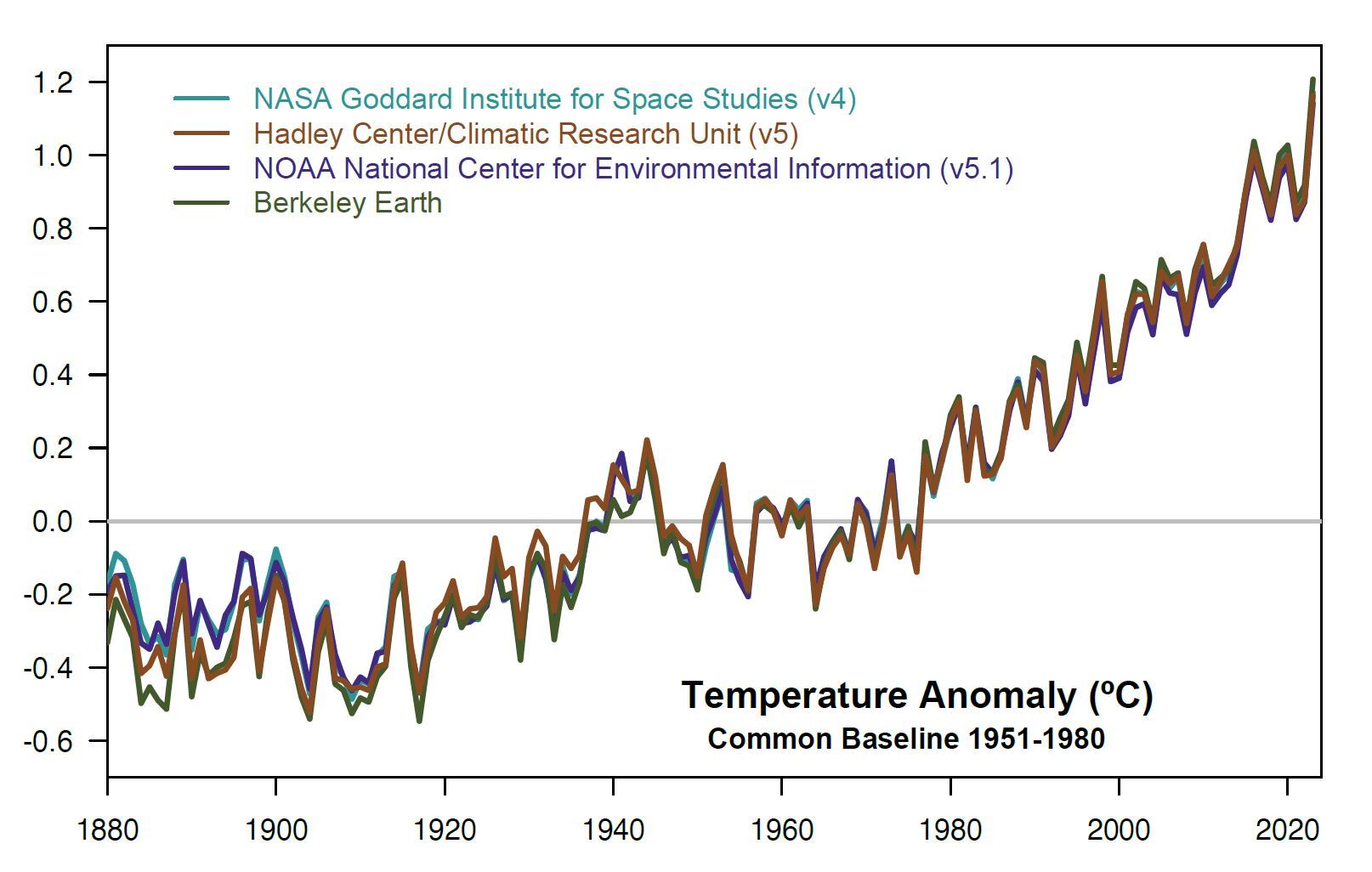

We know this is true thanks to an overwhelming body of evidence that begins with temperature measurements taken at weather stations and on ships starting in the mid-1800s. Later, scientists began tracking surface temperatures with satellites and looking for clues about climate change in geologic records. Together, these data all tell the same story: Earth is getting hotter.

Average global temperatures have increased by 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.2 degrees Celsius, since 1880, with the greatest changes happening in the late 20th century. Land areas have warmed more than the sea surface and the Arctic has warmed the most — by more than 4 degrees Fahrenheit just since the 1960s. Temperature extremes have also shifted. In the United States, daily record highs now outnumber record lows two-to-one.

Where it was cooler or warmer in 2020 compared with the middle of the 20th century

This warming is unprecedented in recent geologic history. A famous illustration, first published in 1998 and often called the hockey-stick graph, shows how temperatures remained fairly flat for centuries (the shaft of the stick) before turning sharply upward (the blade). It’s based on data from tree rings, ice cores and other natural indicators. And the basic picture , which has withstood decades of scrutiny from climate scientists and contrarians alike, shows that Earth is hotter today than it’s been in at least 1,000 years, and probably much longer.

In fact, surface temperatures actually mask the true scale of climate change, because the ocean has absorbed 90 percent of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases . Measurements collected over the last six decades by oceanographic expeditions and networks of floating instruments show that every layer of the ocean is warming up. According to one study , the ocean has absorbed as much heat between 1997 and 2015 as it did in the previous 130 years.

We also know that climate change is happening because we see the effects everywhere. Ice sheets and glaciers are shrinking while sea levels are rising. Arctic sea ice is disappearing. In the spring, snow melts sooner and plants flower earlier. Animals are moving to higher elevations and latitudes to find cooler conditions. And droughts, floods and wildfires have all gotten more extreme. Models predicted many of these changes, but observations show they are now coming to pass.

Back to top .

There’s no denying that scientists love a good, old-fashioned argument. But when it comes to climate change, there is virtually no debate: Numerous studies have found that more than 90 percent of scientists who study Earth’s climate agree that the planet is warming and that humans are the primary cause. Most major scientific bodies, from NASA to the World Meteorological Organization , endorse this view. That’s an astounding level of consensus given the contrarian, competitive nature of the scientific enterprise, where questions like what killed the dinosaurs remain bitterly contested .

Scientific agreement about climate change started to emerge in the late 1980s, when the influence of human-caused warming began to rise above natural climate variability. By 1991, two-thirds of earth and atmospheric scientists surveyed for an early consensus study said that they accepted the idea of anthropogenic global warming. And by 1995, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a famously conservative body that periodically takes stock of the state of scientific knowledge, concluded that “the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernible human influence on global climate.” Currently, more than 97 percent of publishing climate scientists agree on the existence and cause of climate change (as does nearly 60 percent of the general population of the United States).

So where did we get the idea that there’s still debate about climate change? A lot of it came from coordinated messaging campaigns by companies and politicians that opposed climate action. Many pushed the narrative that scientists still hadn’t made up their minds about climate change, even though that was misleading. Frank Luntz, a Republican consultant, explained the rationale in an infamous 2002 memo to conservative lawmakers: “Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly,” he wrote. Questioning consensus remains a common talking point today, and the 97 percent figure has become something of a lightning rod .

To bolster the falsehood of lingering scientific doubt, some people have pointed to things like the Global Warming Petition Project, which urged the United States government to reject the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, an early international climate agreement. The petition proclaimed that climate change wasn’t happening, and even if it were, it wouldn’t be bad for humanity. Since 1998, more than 30,000 people with science degrees have signed it. However, nearly 90 percent of them studied something other than Earth, atmospheric or environmental science, and the signatories included just 39 climatologists. Most were engineers, doctors, and others whose training had little to do with the physics of the climate system.

A few well-known researchers remain opposed to the scientific consensus. Some, like Willie Soon, a researcher affiliated with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, have ties to the fossil fuel industry . Others do not, but their assertions have not held up under the weight of evidence. At least one prominent skeptic, the physicist Richard Muller, changed his mind after reassessing historical temperature data as part of the Berkeley Earth project. His team’s findings essentially confirmed the results he had set out to investigate, and he came away firmly convinced that human activities were warming the planet. “Call me a converted skeptic,” he wrote in an Op-Ed for the Times in 2012.

Mr. Luntz, the Republican pollster, has also reversed his position on climate change and now advises politicians on how to motivate climate action.

A final note on uncertainty: Denialists often use it as evidence that climate science isn’t settled. However, in science, uncertainty doesn’t imply a lack of knowledge. Rather, it’s a measure of how well something is known. In the case of climate change, scientists have found a range of possible future changes in temperature, precipitation and other important variables — which will depend largely on how quickly we reduce emissions. But uncertainty does not undermine their confidence that climate change is real and that people are causing it.

Earth’s climate is inherently variable. Some years are hot and others are cold, some decades bring more hurricanes than others, some ancient droughts spanned the better part of centuries. Glacial cycles operate over many millenniums. So how can scientists look at data collected over a relatively short period of time and conclude that humans are warming the planet? The answer is that the instrumental temperature data that we have tells us a lot, but it’s not all we have to go on.

Historical records stretch back to the 1880s (and often before), when people began to regularly measure temperatures at weather stations and on ships as they traversed the world’s oceans. These data show a clear warming trend during the 20th century.

Global average temperature compared with the middle of the 20th century

+0.75°C

–0.25°

Some have questioned whether these records could be skewed, for instance, by the fact that a disproportionate number of weather stations are near cities, which tend to be hotter than surrounding areas as a result of the so-called urban heat island effect. However, researchers regularly correct for these potential biases when reconstructing global temperatures. In addition, warming is corroborated by independent data like satellite observations, which cover the whole planet, and other ways of measuring temperature changes.

Much has also been made of the small dips and pauses that punctuate the rising temperature trend of the last 150 years. But these are just the result of natural climate variability or other human activities that temporarily counteract greenhouse warming. For instance, in the mid-1900s, internal climate dynamics and light-blocking pollution from coal-fired power plants halted global warming for a few decades. (Eventually, rising greenhouse gases and pollution-control laws caused the planet to start heating up again.) Likewise, the so-called warming hiatus of the 2000s was partly a result of natural climate variability that allowed more heat to enter the ocean rather than warm the atmosphere. The years since have been the hottest on record .

Still, could the entire 20th century just be one big natural climate wiggle? To address that question, we can look at other kinds of data that give a longer perspective. Researchers have used geologic records like tree rings, ice cores, corals and sediments that preserve information about prehistoric climates to extend the climate record. The resulting picture of global temperature change is basically flat for centuries, then turns sharply upward over the last 150 years. It has been a target of climate denialists for decades. However, study after study has confirmed the results , which show that the planet hasn’t been this hot in at least 1,000 years, and probably longer.

Scientists have studied past climate changes to understand the factors that can cause the planet to warm or cool. The big ones are changes in solar energy, ocean circulation, volcanic activity and the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. And they have each played a role at times.

For example, 300 years ago, a combination of reduced solar output and increased volcanic activity cooled parts of the planet enough that Londoners regularly ice skated on the Thames . About 12,000 years ago, major changes in Atlantic circulation plunged the Northern Hemisphere into a frigid state. And 56 million years ago, a giant burst of greenhouse gases, from volcanic activity or vast deposits of methane (or both), abruptly warmed the planet by at least 9 degrees Fahrenheit, scrambling the climate, choking the oceans and triggering mass extinctions.

In trying to determine the cause of current climate changes, scientists have looked at all of these factors . The first three have varied a bit over the last few centuries and they have quite likely had modest effects on climate , particularly before 1950. But they cannot account for the planet’s rapidly rising temperature, especially in the second half of the 20th century, when solar output actually declined and volcanic eruptions exerted a cooling effect.

That warming is best explained by rising greenhouse gas concentrations . Greenhouse gases have a powerful effect on climate (see the next question for why). And since the Industrial Revolution, humans have been adding more of them to the atmosphere, primarily by extracting and burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, which releases carbon dioxide.

Bubbles of ancient air trapped in ice show that, before about 1750, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was roughly 280 parts per million. It began to rise slowly and crossed the 300 p.p.m. threshold around 1900. CO2 levels then accelerated as cars and electricity became big parts of modern life, recently topping 420 p.p.m . The concentration of methane, the second most important greenhouse gas, has more than doubled. We’re now emitting carbon much faster than it was released 56 million years ago .

30 billion metric tons

Carbon dioxide emitted worldwide 1850-2017

Rest of world

Other developed

European Union

Developed economies

Other countries

United States

E.U. and U.K.

These rapid increases in greenhouse gases have caused the climate to warm abruptly. In fact, climate models suggest that greenhouse warming can explain virtually all of the temperature change since 1950. According to the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which assesses published scientific literature, natural drivers and internal climate variability can only explain a small fraction of late-20th century warming.

Another study put it this way: The odds of current warming occurring without anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are less than 1 in 100,000 .

But greenhouse gases aren’t the only climate-altering compounds people put into the air. Burning fossil fuels also produces particulate pollution that reflects sunlight and cools the planet. Scientists estimate that this pollution has masked up to half of the greenhouse warming we would have otherwise experienced.

Greenhouse gases like water vapor and carbon dioxide serve an important role in the climate. Without them, Earth would be far too cold to maintain liquid water and humans would not exist!

Here’s how it works: the planet’s temperature is basically a function of the energy the Earth absorbs from the sun (which heats it up) and the energy Earth emits to space as infrared radiation (which cools it down). Because of their molecular structure, greenhouse gases temporarily absorb some of that outgoing infrared radiation and then re-emit it in all directions, sending some of that energy back toward the surface and heating the planet . Scientists have understood this process since the 1850s .

Greenhouse gas concentrations have varied naturally in the past. Over millions of years, atmospheric CO2 levels have changed depending on how much of the gas volcanoes belched into the air and how much got removed through geologic processes. On time scales of hundreds to thousands of years, concentrations have changed as carbon has cycled between the ocean, soil and air.

Today, however, we are the ones causing CO2 levels to increase at an unprecedented pace by taking ancient carbon from geologic deposits of fossil fuels and putting it into the atmosphere when we burn them. Since 1750, carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by almost 50 percent. Methane and nitrous oxide, other important anthropogenic greenhouse gases that are released mainly by agricultural activities, have also spiked over the last 250 years.

We know based on the physics described above that this should cause the climate to warm. We also see certain telltale “fingerprints” of greenhouse warming. For example, nights are warming even faster than days because greenhouse gases don’t go away when the sun sets. And upper layers of the atmosphere have actually cooled, because more energy is being trapped by greenhouse gases in the lower atmosphere.

We also know that we are the cause of rising greenhouse gas concentrations — and not just because we can measure the CO2 coming out of tailpipes and smokestacks. We can see it in the chemical signature of the carbon in CO2.

Carbon comes in three different masses: 12, 13 and 14. Things made of organic matter (including fossil fuels) tend to have relatively less carbon-13. Volcanoes tend to produce CO2 with relatively more carbon-13. And over the last century, the carbon in atmospheric CO2 has gotten lighter, pointing to an organic source.

We can tell it’s old organic matter by looking for carbon-14, which is radioactive and decays over time. Fossil fuels are too ancient to have any carbon-14 left in them, so if they were behind rising CO2 levels, you would expect the amount of carbon-14 in the atmosphere to drop, which is exactly what the data show .

It’s important to note that water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. However, it does not cause warming; instead it responds to it . That’s because warmer air holds more moisture, which creates a snowball effect in which human-caused warming allows the atmosphere to hold more water vapor and further amplifies climate change. This so-called feedback cycle has doubled the warming caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

A common source of confusion when it comes to climate change is the difference between weather and climate. Weather is the constantly changing set of meteorological conditions that we experience when we step outside, whereas climate is the long-term average of those conditions, usually calculated over a 30-year period. Or, as some say: Weather is your mood and climate is your personality.

So while 2 degrees Fahrenheit doesn’t represent a big change in the weather, it’s a huge change in climate. As we’ve already seen, it’s enough to melt ice and raise sea levels, to shift rainfall patterns around the world and to reorganize ecosystems, sending animals scurrying toward cooler habitats and killing trees by the millions.

It’s also important to remember that two degrees represents the global average, and many parts of the world have already warmed by more than that. For example, land areas have warmed about twice as much as the sea surface. And the Arctic has warmed by about 5 degrees. That’s because the loss of snow and ice at high latitudes allows the ground to absorb more energy, causing additional heating on top of greenhouse warming.

Relatively small long-term changes in climate averages also shift extremes in significant ways. For instance, heat waves have always happened, but they have shattered records in recent years. In June of 2020, a town in Siberia registered temperatures of 100 degrees . And in Australia, meteorologists have added a new color to their weather maps to show areas where temperatures exceed 125 degrees. Rising sea levels have also increased the risk of flooding because of storm surges and high tides. These are the foreshocks of climate change.

And we are in for more changes in the future — up to 9 degrees Fahrenheit of average global warming by the end of the century, in the worst-case scenario . For reference, the difference in global average temperatures between now and the peak of the last ice age, when ice sheets covered large parts of North America and Europe, is about 11 degrees Fahrenheit.

Under the Paris Climate Agreement, which President Biden recently rejoined, countries have agreed to try to limit total warming to between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, since preindustrial times. And even this narrow range has huge implications . According to scientific studies, the difference between 2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit will very likely mean the difference between coral reefs hanging on or going extinct, and between summer sea ice persisting in the Arctic or disappearing completely. It will also determine how many millions of people suffer from water scarcity and crop failures, and how many are driven from their homes by rising seas. In other words, one degree Fahrenheit makes a world of difference.

Earth’s climate has always changed. Hundreds of millions of years ago, the entire planet froze . Fifty million years ago, alligators lived in what we now call the Arctic . And for the last 2.6 million years, the planet has cycled between ice ages when the planet was up to 11 degrees cooler and ice sheets covered much of North America and Europe, and milder interglacial periods like the one we’re in now.

Climate denialists often point to these natural climate changes as a way to cast doubt on the idea that humans are causing climate to change today. However, that argument rests on a logical fallacy. It’s like “seeing a murdered body and concluding that people have died of natural causes in the past, so the murder victim must also have died of natural causes,” a team of social scientists wrote in The Debunking Handbook , which explains the misinformation strategies behind many climate myths.

Indeed, we know that different mechanisms caused the climate to change in the past. Glacial cycles, for example, were triggered by periodic variations in Earth’s orbit , which take place over tens of thousands of years and change how solar energy gets distributed around the globe and across the seasons.

These orbital variations don’t affect the planet’s temperature much on their own. But they set off a cascade of other changes in the climate system; for instance, growing or melting vast Northern Hemisphere ice sheets and altering ocean circulation. These changes, in turn, affect climate by altering the amount of snow and ice, which reflect sunlight, and by changing greenhouse gas concentrations. This is actually part of how we know that greenhouse gases have the ability to significantly affect Earth’s temperature.

For at least the last 800,000 years , atmospheric CO2 concentrations oscillated between about 180 parts per million during ice ages and about 280 p.p.m. during warmer periods, as carbon moved between oceans, forests, soils and the atmosphere. These changes occurred in lock step with global temperatures, and are a major reason the entire planet warmed and cooled during glacial cycles, not just the frozen poles.

Today, however, CO2 levels have soared to 420 p.p.m. — the highest they’ve been in at least three million years . The concentration of CO2 is also increasing about 100 times faster than it did at the end of the last ice age. This suggests something else is going on, and we know what it is: Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have been burning fossil fuels and releasing greenhouse gases that are heating the planet now (see Question 5 for more details on how we know this, and Questions 4 and 8 for how we know that other natural forces aren’t to blame).

Over the next century or two, societies and ecosystems will experience the consequences of this climate change. But our emissions will have even more lasting geologic impacts: According to some studies, greenhouse gas levels may have already warmed the planet enough to delay the onset of the next glacial cycle for at least an additional 50,000 years.

The sun is the ultimate source of energy in Earth’s climate system, so it’s a natural candidate for causing climate change. And solar activity has certainly changed over time. We know from satellite measurements and other astronomical observations that the sun’s output changes on 11-year cycles. Geologic records and sunspot numbers, which astronomers have tracked for centuries, also show long-term variations in the sun’s activity, including some exceptionally quiet periods in the late 1600s and early 1800s.

We know that, from 1900 until the 1950s, solar irradiance increased. And studies suggest that this had a modest effect on early 20th century climate, explaining up to 10 percent of the warming that’s occurred since the late 1800s. However, in the second half of the century, when the most warming occurred, solar activity actually declined . This disparity is one of the main reasons we know that the sun is not the driving force behind climate change.

Another reason we know that solar activity hasn’t caused recent warming is that, if it had, all the layers of the atmosphere should be heating up. Instead, data show that the upper atmosphere has actually cooled in recent decades — a hallmark of greenhouse warming .

So how about volcanoes? Eruptions cool the planet by injecting ash and aerosol particles into the atmosphere that reflect sunlight. We’ve observed this effect in the years following large eruptions. There are also some notable historical examples, like when Iceland’s Laki volcano erupted in 1783, causing widespread crop failures in Europe and beyond, and the “ year without a summer ,” which followed the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia.

Since volcanoes mainly act as climate coolers, they can’t really explain recent warming. However, scientists say that they may also have contributed slightly to rising temperatures in the early 20th century. That’s because there were several large eruptions in the late 1800s that cooled the planet, followed by a few decades with no major volcanic events when warming caught up. During the second half of the 20th century, though, several big eruptions occurred as the planet was heating up fast. If anything, they temporarily masked some amount of human-caused warming.

The second way volcanoes can impact climate is by emitting carbon dioxide. This is important on time scales of millions of years — it’s what keeps the planet habitable (see Question 5 for more on the greenhouse effect). But by comparison to modern anthropogenic emissions, even big eruptions like Krakatoa and Mount St. Helens are just a drop in the bucket. After all, they last only a few hours or days, while we burn fossil fuels 24-7. Studies suggest that, today, volcanoes account for 1 to 2 percent of total CO2 emissions.

When a big snowstorm hits the United States, climate denialists can try to cite it as proof that climate change isn’t happening. In 2015, Senator James Inhofe, an Oklahoma Republican, famously lobbed a snowball in the Senate as he denounced climate science. But these events don’t actually disprove climate change.

While there have been some memorable storms in recent years, winters are actually warming across the world. In the United States, average temperatures in December, January and February have increased by about 2.5 degrees this century.

On the flip side, record cold days are becoming less common than record warm days. In the United States, record highs now outnumber record lows two-to-one . And ever-smaller areas of the country experience extremely cold winter temperatures . (The same trends are happening globally.)

So what’s with the blizzards? Weather always varies, so it’s no surprise that we still have severe winter storms even as average temperatures rise. However, some studies suggest that climate change may be to blame. One possibility is that rapid Arctic warming has affected atmospheric circulation, including the fast-flowing, high-altitude air that usually swirls over the North Pole (a.k.a. the Polar Vortex ). Some studies suggest that these changes are bringing more frigid temperatures to lower latitudes and causing weather systems to stall , allowing storms to produce more snowfall. This may explain what we’ve experienced in the U.S. over the past few decades, as well as a wintertime cooling trend in Siberia , although exactly how the Arctic affects global weather remains a topic of ongoing scientific debate .

Climate change may also explain the apparent paradox behind some of the other places on Earth that haven’t warmed much. For instance, a splotch of water in the North Atlantic has cooled in recent years, and scientists say they suspect that may be because ocean circulation is slowing as a result of freshwater streaming off a melting Greenland . If this circulation grinds almost to a halt, as it’s done in the geologic past, it would alter weather patterns around the world.

Not all cold weather stems from some counterintuitive consequence of climate change. But it’s a good reminder that Earth’s climate system is complex and chaotic, so the effects of human-caused changes will play out differently in different places. That’s why “global warming” is a bit of an oversimplification. Instead, some scientists have suggested that the phenomenon of human-caused climate change would more aptly be called “ global weirding .”

Extreme weather and natural disasters are part of life on Earth — just ask the dinosaurs. But there is good evidence that climate change has increased the frequency and severity of certain phenomena like heat waves, droughts and floods. Recent research has also allowed scientists to identify the influence of climate change on specific events.

Let’s start with heat waves . Studies show that stretches of abnormally high temperatures now happen about five times more often than they would without climate change, and they last longer, too. Climate models project that, by the 2040s, heat waves will be about 12 times more frequent. And that’s concerning since extreme heat often causes increased hospitalizations and deaths, particularly among older people and those with underlying health conditions. In the summer of 2003, for example, a heat wave caused an estimated 70,000 excess deaths across Europe. (Human-caused warming amplified the death toll .)

Climate change has also exacerbated droughts , primarily by increasing evaporation. Droughts occur naturally because of random climate variability and factors like whether El Niño or La Niña conditions prevail in the tropical Pacific. But some researchers have found evidence that greenhouse warming has been affecting droughts since even before the Dust Bowl . And it continues to do so today. According to one analysis , the drought that afflicted the American Southwest from 2000 to 2018 was almost 50 percent more severe because of climate change. It was the worst drought the region had experienced in more than 1,000 years.

Rising temperatures have also increased the intensity of heavy precipitation events and the flooding that often follows. For example, studies have found that, because warmer air holds more moisture, Hurricane Harvey, which struck Houston in 2017, dropped between 15 and 40 percent more rainfall than it would have without climate change.

It’s still unclear whether climate change is changing the overall frequency of hurricanes, but it is making them stronger . And warming appears to favor certain kinds of weather patterns, like the “ Midwest Water Hose ” events that caused devastating flooding across the Midwest in 2019 .

It’s important to remember that in most natural disasters, there are multiple factors at play. For instance, the 2019 Midwest floods occurred after a recent cold snap had frozen the ground solid, preventing the soil from absorbing rainwater and increasing runoff into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. These waterways have also been reshaped by levees and other forms of river engineering, some of which failed in the floods.

Wildfires are another phenomenon with multiple causes. In many places, fire risk has increased because humans have aggressively fought natural fires and prevented Indigenous peoples from carrying out traditional burning practices. This has allowed fuel to accumulate that makes current fires worse .

However, climate change still plays a major role by heating and drying forests, turning them into tinderboxes. Studies show that warming is the driving factor behind the recent increases in wildfires; one analysis found that climate change is responsible for doubling the area burned across the American West between 1984 and 2015. And researchers say that warming will only make fires bigger and more dangerous in the future.

It depends on how aggressively we act to address climate change. If we continue with business as usual, by the end of the century, it will be too hot to go outside during heat waves in the Middle East and South Asia . Droughts will grip Central America, the Mediterranean and southern Africa. And many island nations and low-lying areas, from Texas to Bangladesh, will be overtaken by rising seas. Conversely, climate change could bring welcome warming and extended growing seasons to the upper Midwest , Canada, the Nordic countries and Russia . Farther north, however, the loss of snow, ice and permafrost will upend the traditions of Indigenous peoples and threaten infrastructure.

It’s complicated, but the underlying message is simple: unchecked climate change will likely exacerbate existing inequalities . At a national level, poorer countries will be hit hardest, even though they have historically emitted only a fraction of the greenhouse gases that cause warming. That’s because many less developed countries tend to be in tropical regions where additional warming will make the climate increasingly intolerable for humans and crops. These nations also often have greater vulnerabilities, like large coastal populations and people living in improvised housing that is easily damaged in storms. And they have fewer resources to adapt, which will require expensive measures like redesigning cities, engineering coastlines and changing how people grow food.

Already, between 1961 and 2000, climate change appears to have harmed the economies of the poorest countries while boosting the fortunes of the wealthiest nations that have done the most to cause the problem, making the global wealth gap 25 percent bigger than it would otherwise have been. Similarly, the Global Climate Risk Index found that lower income countries — like Myanmar, Haiti and Nepal — rank high on the list of nations most affected by extreme weather between 1999 and 2018. Climate change has also contributed to increased human migration, which is expected to increase significantly .

Even within wealthy countries, the poor and marginalized will suffer the most. People with more resources have greater buffers, like air-conditioners to keep their houses cool during dangerous heat waves, and the means to pay the resulting energy bills. They also have an easier time evacuating their homes before disasters, and recovering afterward. Lower income people have fewer of these advantages, and they are also more likely to live in hotter neighborhoods and work outdoors, where they face the brunt of climate change.

These inequalities will play out on an individual, community, and regional level. A 2017 analysis of the U.S. found that, under business as usual, the poorest one-third of counties, which are concentrated in the South, will experience damages totaling as much as 20 percent of gross domestic product, while others, mostly in the northern part of the country, will see modest economic gains. Solomon Hsiang, an economist at University of California, Berkeley, and the lead author of the study, has said that climate change “may result in the largest transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the country’s history.”

Even the climate “winners” will not be immune from all climate impacts, though. Desirable locations will face an influx of migrants. And as the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated, disasters in one place quickly ripple across our globalized economy. For instance, scientists expect climate change to increase the odds of multiple crop failures occurring at the same time in different places, throwing the world into a food crisis .

On top of that, warmer weather is aiding the spread of infectious diseases and the vectors that transmit them, like ticks and mosquitoes . Research has also identified troubling correlations between rising temperatures and increased interpersonal violence , and climate change is widely recognized as a “threat multiplier” that increases the odds of larger conflicts within and between countries. In other words, climate change will bring many changes that no amount of money can stop. What could help is taking action to limit warming.

One of the most common arguments against taking aggressive action to combat climate change is that doing so will kill jobs and cripple the economy. But this implies that there’s an alternative in which we pay nothing for climate change. And unfortunately, there isn’t. In reality, not tackling climate change will cost a lot , and cause enormous human suffering and ecological damage, while transitioning to a greener economy would benefit many people and ecosystems around the world.

Let’s start with how much it will cost to address climate change. To keep warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, the goal of the Paris Climate Agreement, society will have to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the middle of this century. That will require significant investments in things like renewable energy, electric cars and charging infrastructure, not to mention efforts to adapt to hotter temperatures, rising sea-levels and other unavoidable effects of current climate changes. And we’ll have to make changes fast.

Estimates of the cost vary widely. One recent study found that keeping warming to 2 degrees Celsius would require a total investment of between $4 trillion and $60 trillion, with a median estimate of $16 trillion, while keeping warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius could cost between $10 trillion and $100 trillion, with a median estimate of $30 trillion. (For reference, the entire world economy was about $88 trillion in 2019.) Other studies have found that reaching net zero will require annual investments ranging from less than 1.5 percent of global gross domestic product to as much as 4 percent . That’s a lot, but within the range of historical energy investments in countries like the U.S.

Now, let’s consider the costs of unchecked climate change, which will fall hardest on the most vulnerable. These include damage to property and infrastructure from sea-level rise and extreme weather, death and sickness linked to natural disasters, pollution and infectious disease, reduced agricultural yields and lost labor productivity because of rising temperatures, decreased water availability and increased energy costs, and species extinction and habitat destruction. Dr. Hsiang, the U.C. Berkeley economist, describes it as “death by a thousand cuts.”

As a result, climate damages are hard to quantify. Moody’s Analytics estimates that even 2 degrees Celsius of warming will cost the world $69 trillion by 2100, and economists expect the toll to keep rising with the temperature. In a recent survey , economists estimated the cost would equal 5 percent of global G.D.P. at 3 degrees Celsius of warming (our trajectory under current policies) and 10 percent for 5 degrees Celsius. Other research indicates that, if current warming trends continue, global G.D.P. per capita will decrease between 7 percent and 23 percent by the end of the century — an economic blow equivalent to multiple coronavirus pandemics every year. And some fear these are vast underestimates .

Already, studies suggest that climate change has slashed incomes in the poorest countries by as much as 30 percent and reduced global agricultural productivity by 21 percent since 1961. Extreme weather events have also racked up a large bill. In 2020, in the United States alone, climate-related disasters like hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires caused nearly $100 billion in damages to businesses, property and infrastructure, compared to an average of $18 billion per year in the 1980s.

Given the steep price of inaction, many economists say that addressing climate change is a better deal . It’s like that old saying: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In this case, limiting warming will greatly reduce future damage and inequality caused by climate change. It will also produce so-called co-benefits, like saving one million lives every year by reducing air pollution, and millions more from eating healthier, climate-friendly diets. Some studies even find that meeting the Paris Agreement goals could create jobs and increase global G.D.P . And, of course, reining in climate change will spare many species and ecosystems upon which humans depend — and which many people believe to have their own innate value.

The challenge is that we need to reduce emissions now to avoid damages later, which requires big investments over the next few decades. And the longer we delay, the more we will pay to meet the Paris goals. One recent analysis found that reaching net-zero by 2050 would cost the U.S. almost twice as much if we waited until 2030 instead of acting now. But even if we miss the Paris target, the economics still make a strong case for climate action, because every additional degree of warming will cost us more — in dollars, and in lives.

Veronica Penney contributed reporting.

Illustration photographs by Esther Horvath, Max Whittaker, David Maurice Smith and Talia Herman for The New York Times; Esther Horvath/Alfred-Wegener-Institut

An earlier version of this article misidentified the authors of The Debunking Handbook. It was written by social scientists who study climate communication, not a team of climate scientists.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected] . Learn more

Our Coverage of Climate and the Environment

Climate F.A.Q.: Do you have questions about climate change? We’ve got answers .

Changing DNA to Fight Climate Change: Farmers are spraying corn seeds with genetically modified bacteria to save money on fertilizer. The process is greener, but there is intense pushback .

Fires are Getting Faster: In recent decades, fast-growing blazes were responsible for an outsize share of fire-related devastation , scientists found using satellite data.

Russia’s Warming Arctic: Climate science has been stymied as Russia continues its war in Ukraine . Because of the stalled work, the West may be left without a clear picture of how fast the Earth is heating up.

Ask NYT Climate : Want to know how you can slash Halloween waste? We’ve got tips to make the holiday more sustainable .

Advertisement

Scientific Consensus

It’s important to remember that scientists always focus on the evidence, not on opinions. Scientific evidence continues to show that human activities ( primarily the human burning of fossil fuels ) have warmed Earth’s surface and its ocean basins, which in turn have continued to impact Earth’s climate . This is based on over a century of scientific evidence forming the structural backbone of today's civilization.

NASA Global Climate Change presents the state of scientific knowledge about climate change while highlighting the role NASA plays in better understanding our home planet. This effort includes citing multiple peer-reviewed studies from research groups across the world, 1 illustrating the accuracy and consensus of research results (in this case, the scientific consensus on climate change) consistent with NASA’s scientific research portfolio.

With that said, multiple studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals 1 show that climate-warming trends over the past century are extremely likely due to human activities. In addition, most of the leading scientific organizations worldwide have issued public statements endorsing this position. The following is a partial list of these organizations, along with links to their published statements and a selection of related resources.

American Scientific Societies

Statement on climate change from 18 scientific associations.

"Observations throughout the world make it clear that climate change is occurring, and rigorous scientific research demonstrates that the greenhouse gases emitted by human activities are the primary driver." (2009) 2

American Association for the Advancement of Science

"Based on well-established evidence, about 97% of climate scientists have concluded that human-caused climate change is happening." (2014) 3

American Chemical Society

"The Earth’s climate is changing in response to increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and particulate matter in the atmosphere, largely as the result of human activities." (2016-2019) 4

American Geophysical Union

"Based on extensive scientific evidence, it is extremely likely that human activities, especially emissions of greenhouse gases, are the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century. There is no alterative explanation supported by convincing evidence." (2019) 5

American Medical Association

"Our AMA ... supports the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fourth assessment report and concurs with the scientific consensus that the Earth is undergoing adverse global climate change and that anthropogenic contributions are significant." (2019) 6

American Meteorological Society

"Research has found a human influence on the climate of the past several decades ... The IPCC (2013), USGCRP (2017), and USGCRP (2018) indicate that it is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-twentieth century." (2019) 7

American Physical Society

"Earth's changing climate is a critical issue and poses the risk of significant environmental, social and economic disruptions around the globe. While natural sources of climate variability are significant, multiple lines of evidence indicate that human influences have had an increasingly dominant effect on global climate warming observed since the mid-twentieth century." (2015) 8

The Geological Society of America

"The Geological Society of America (GSA) concurs with assessments by the National Academies of Science (2005), the National Research Council (2011), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2013) and the U.S. Global Change Research Program (Melillo et al., 2014) that global climate has warmed in response to increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases ... Human activities (mainly greenhouse-gas emissions) are the dominant cause of the rapid warming since the middle 1900s (IPCC, 2013)." (2015) 9

Science Academies

International academies: joint statement.

"Climate change is real. There will always be uncertainty in understanding a system as complex as the world’s climate. However there is now strong evidence that significant global warming is occurring. The evidence comes from direct measurements of rising surface air temperatures and subsurface ocean temperatures and from phenomena such as increases in average global sea levels, retreating glaciers, and changes to many physical and biological systems. It is likely that most of the warming in recent decades can be attributed to human activities (IPCC 2001)." (2005, 11 international science academies) 1 0

U.S. National Academy of Sciences

"Scientists have known for some time, from multiple lines of evidence, that humans are changing Earth’s climate, primarily through greenhouse gas emissions." 1 1

U.S. Government Agencies

U.s. global change research program.

"Earth’s climate is now changing faster than at any point in the history of modern civilization, primarily as a result of human activities." (2018, 13 U.S. government departments and agencies) 12

Intergovernmental Bodies

Intergovernmental panel on climate change.

“It is unequivocal that the increase of CO 2 , methane, and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere over the industrial era is the result of human activities and that human influence is the principal driver of many changes observed across the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere. “Since systematic scientific assessments began in the 1970s, the influence of human activity on the warming of the climate system has evolved from theory to established fact.” 1 3-17

Other Resources

List of worldwide scientific organizations.

The following page lists the nearly 200 worldwide scientific organizations that hold the position that climate change has been caused by human action. http://www.opr.ca.gov/facts/list-of-scientific-organizations.html

U.S. Agencies

The following page contains information on what federal agencies are doing to adapt to climate change. https://www.c2es.org/site/assets/uploads/2012/02/climate-change-adaptation-what-federal-agencies-are-doing.pdf

Technically, a “consensus” is a general agreement of opinion, but the scientific method steers us away from this to an objective framework. In science, facts or observations are explained by a hypothesis (a statement of a possible explanation for some natural phenomenon), which can then be tested and retested until it is refuted (or disproved).

As scientists gather more observations, they will build off one explanation and add details to complete the picture. Eventually, a group of hypotheses might be integrated and generalized into a scientific theory, a scientifically acceptable general principle or body of principles offered to explain phenomena.

1. K. Myers, et al, "Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later", Environmental Research Letters Vol.16 No. 10, 104030 (20 October 2021); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774 M. Lynas, et al, "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature", Environmental Research Letters Vol.16 No. 11, 114005 (19 October 2021); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966 J. Cook et al., "Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming", Environmental Research Letters Vol. 11 No. 4, (13 April 2016); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002 J. Cook et al., "Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature", Environmental Research Letters Vol. 8 No. 2, (15 May 2013); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024 W. R. L. Anderegg, “Expert Credibility in Climate Change”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 107 No. 27, 12107-12109 (21 June 2010); DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1003187107 P. T. Doran & M. K. Zimmerman, "Examining the Scientific Consensus on Climate Change", Eos Transactions American Geophysical Union Vol. 90 Issue 3 (2009), 22; DOI: 10.1029/2009EO030002 N. Oreskes, “Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change”, Science Vol. 306 no. 5702, p. 1686 (3 December 2004); DOI: 10.1126/science.1103618

2. Statement on climate change from 18 scientific associations (2009)

3. AAAS Board Statement on Climate Change (2014)

4. ACS Public Policy Statement: Climate Change (2016-2019)

5. Society Must Address the Growing Climate Crisis Now (2019)

6. Global Climate Change and Human Health (2019)

7. Climate Change: An Information Statement of the American Meteorological Society (2019)

8. American Physical Society (2021)

9. GSA Position Statement on Climate Change (2015)

10. Joint science academies' statement: Global response to climate change (2005)

11. Climate at the National Academies

12. Fourth National Climate Assessment: Volume II (2018)

13. IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers, SPM 1.1 (2014)

14. IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers, SPM 1 (2014)

15. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Working Group 1 (2021)