2x match challenge

Donate now to support families worldwide.

The future is equal

What is global inequality?

ACT NOW: Your gift can be doubled to support Oxfam’s lifesaving work.

An unequal world makes ending poverty harder—and puts the chance at a good life out of reach for too many people.

Imagine lining up everyone on the planet by their wealth and status. On one end, a small group of individuals that have few, if any, barriers to living a full and healthy life. On the other, a larger group of people who find themselves excluded from the possibility to do the same.

Understanding global inequality starts with recognizing that not everyone enjoys the same rights, treatment, and opportunities. If you face generational poverty or gender discrimination, these barriers to equality can have profound implications for the kind of life you want to live.

At Oxfam, our mission is to fight global inequality to end poverty and injustice. So we’re going to explore global inequality, step by step: What is it; how is it measured (and do different ways of measuring it matter); and how we can reduce global inequality toward ending poverty and injustice.

So what is global inequality?

Global inequality is the unequal distribution of resources, opportunities, and power that shape well-being among the 8 billion individuals on our planet. Distinct from inequality within a country or between countries, global inequality is one way of understanding the different lived experiences of our fellow humans, no matter where they live.

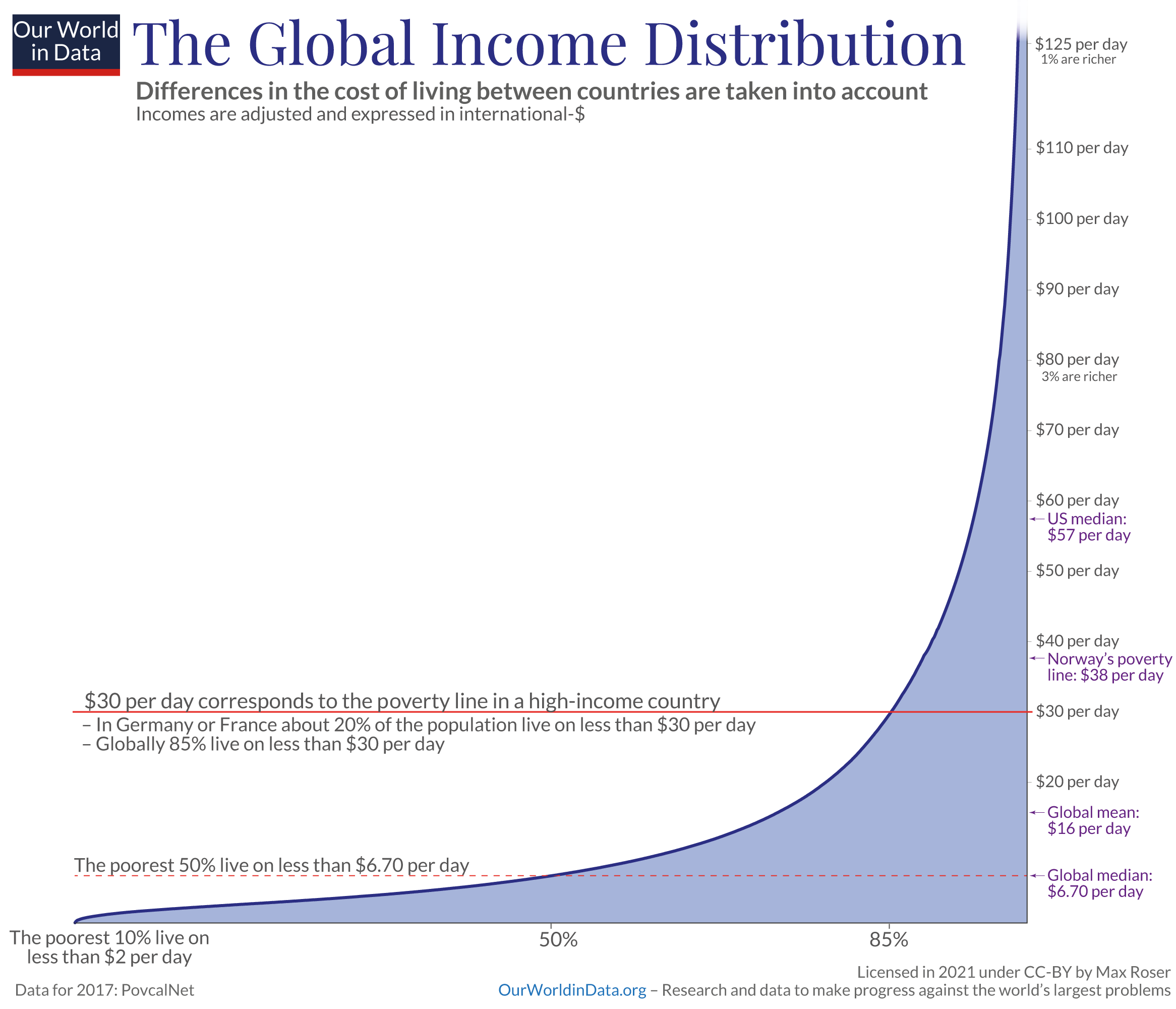

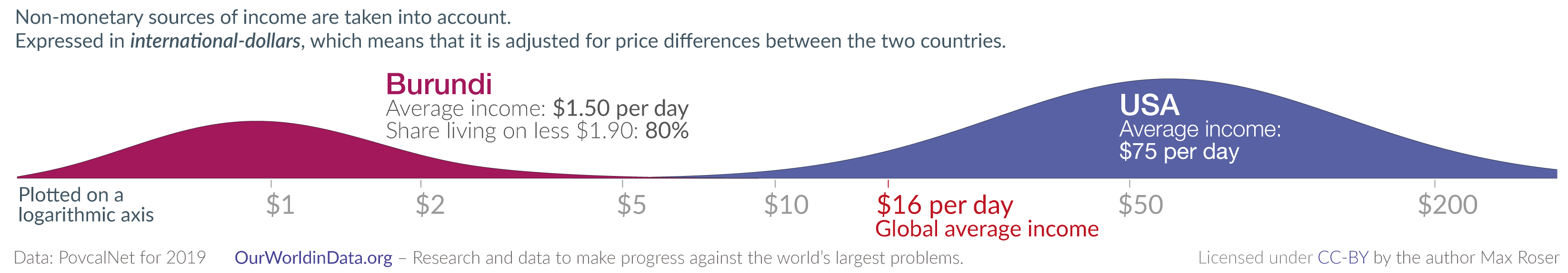

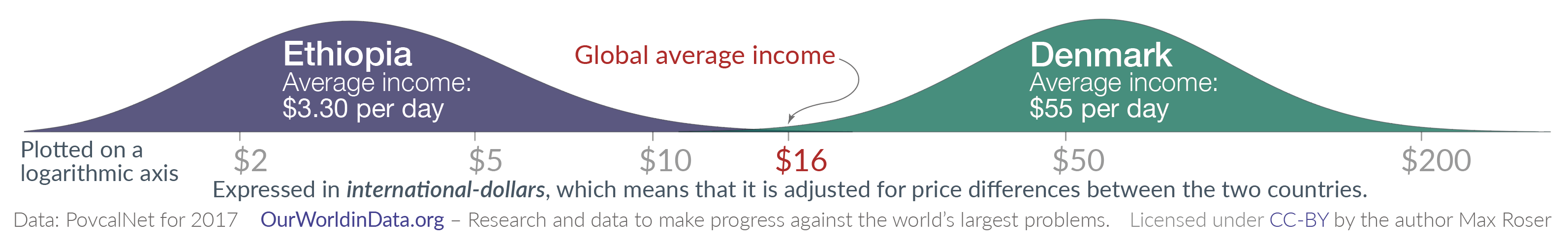

Notably, global inequality is worse than inequality within countries. And economic inequality—the unequal distribution of income—is one strikingly visible dimension of global inequalities in well-being.

- In the early 1800s, individuals worldwide had more similar living standards, and differences in wealth and income were closer.

- Global inequality grew substantially after the Industrial Revolution, sparking rapid income growth in Western Europe, the US, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand as compared with incomes in other countries.

- Fast forward to today, the 10 richest men in the world own more than the bottom 3.1 billion people.

Economic inequality often interacts with other kinds of disadvantage that result from power imbalances in society worldwide. For example, the absence of women’s voices in decision-making spaces or a caste system that discriminates against sectors of society with lower status reflect cultural, political, and social inequalities that undermine people’s well-being.

- Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen calls the array of things that make up well-being “capabilities.”

- Capabilities are essential “freedoms” that make it possible to live a full and healthy life. They come from having adequate resources and the ability to use those resources with ease and purpose.

In other words: Global inequality stems not just from what people have and don’t have—but what they're able to do with what they have.

How is global inequality measured and does how you measure it matter?

Global inequality can be measured and understood in many ways. Some economic measures focus on the share of income that middle-income groups of people enjoy over time, while others look at the growing wealth among the richest in society.

- According to the World Bank, global inequality is on the rise for the first time in decades because the poorest 40 percent of the world lost twice as much income as the wealthiest 20 percent during the global pandemic. It's the largest increase since 1990.

- But Oxfam considers an alternative measurement: the ratio of income share held by the richest 5 percent as compared with the poorest 40 percent. This approach tries to better capture the extreme concentration of wealth and income.

This widening inequality is a major risk to human flourishing. Unequal treatment breeds distrust, and countries with high inequality grow more slowly—closing off opportunities for economic advancement. Measures that focus on extreme wealth and income also make it easier to see how structural policy choices widen gender and racial inequalities.

So what do we learn by taking a closer look at the growing gap between the rich and the poor?

- 252 men have more wealth than all 1 billion women and girls in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, combined.

- In the US, 3.4 million Black Americans would be alive today if their life expectancy was the same as White people’s. Before COVID-19, that alarming number was already 2.1 million.

- Twenty of the richest billionaires are estimated, on average, to be emitting as much as 8,000 times more carbon than the billion poorest people—increasing the risk of climate-driven humanitarian crisis.

“The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little,” said former US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

How can we reduce global inequality? What could it mean for ending poverty and injustice?

We all have a role to play in creating a more equal future, but governments and the private sector must be responsive to the perspectives and solutions of those most affected by poverty to reduce global inequality in two main areas.

- Corporate board rooms, international climate conferences, and national governments must be accountable to women, workers, and representatives of marginalized communities. When these groups gain power and political voice, they better influence these decision-making spaces, defining their own way out of poverty and tackling the factors that keep people poor.

- Through foreign aid that supports local people and institutions as well as financial commitments that help climate-vulnerable countries tackle the climate crisis, rich industrialized countries have a central role to play in making critical investments to reduce global inequality.

- By making billionaires and giant corporations pay their fair share of taxes, governments can direct more resources to strengthen health systems, lift children out of poverty, and grow more inclusive economies.

Where you’re born or live shouldn’t determine your future, but for too many people, inequality squanders human potential. We need to clearly see the fundamental unfairness and dangers of highly unequal societies, and we must take action to help more people enjoy the freedoms to live a full and healthy life.

While Oxfam has long focused on global inequality, inequality within the US remains a huge challenge. For workers in many states across the South, low wages, a lack of workplace protections, and prohibitions against organizing unions are worsening inequality.

But there’s hope for the future. For the last five years, Oxfam has produced the Best States to Work Index to track how states protect, support, and pay workers. Workers are demanding and winning change, organizing to form new unions, elect more helpful lawmakers, and press for changes in state laws.

Where does your state rank?

Find out in our 2022 Best and Worst States to Work in America rankings, as featured on Season 2, Episode 3 of "The Problem with Jon Stewart" on Apple TV+.

There was a response error processing your form. Please try again. Error code: GLB

Best and Worst States to Work in America

Click here for your special download link . Thank you for your interest in our Best States to Work rankings. We're excited to keep you informed about ways you can partner with Oxfam to fight global inequality to end poverty and injustice.

Related content

What happens when I take an action with Oxfam?

One way we hold the powerful accountable is through petitions. So, what happens to your signature after you've signed?

The Future of Food

How Oxfam and our partners are working with people and communities to rethink the way we produce, process, and distribute the world's food.

Securing land rights secures a brighter future

Oxfam partner influences establishment of equitable land policies in Timor-Leste and empowers citizens to fight for their land rights.

Rising inequality affecting more than two-thirds of the globe, but it’s not inevitable: new UN report

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Inequality is growing for more than 70 per cent of the global population, exacerbating the risks of divisions and hampering economic and social development. But the rise is far from inevitable and can be tackled at a national and international level, says a flagship study released by the UN on Tuesday.

The World Social Report 2020, published by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), shows that income inequality has increased in most developed countries, and some middle-income countries - including China, which has the world’s fastest growing economy.

The challenges are underscored by UN chief António Guterres in the foreword, in which he states that the world is confronting “the harsh realities of a deeply unequal global landscape”, in which economic woes, inequalities and job insecurity have led to mass protests in both developed and developing countries.

“Income disparities and a lack of opportunities”, he writes, “are creating a vicious cycle of inequality, frustration and discontent across generations.”

‘The one per cent’ winners take (almost) all

The study shows that the richest one per cent of the population are the big winners in the changing global economy, increasing their share of income between 1990 and 2015, while at the other end of the scale, the bottom 40 per cent earned less than a quarter of income in all countries surveyed.

One of the consequences of inequality within societies, notes the report, is slower economic growth. In unequal societies, with wide disparities in areas such as health care and education, people are more likely to remain trapped in poverty, across several generations.

Between countries, the difference in average incomes is reducing, with China and other Asian nations driving growth in the global economy. Nevertheless, there are still stark differences between the richest and poorest countries and regions: the average income in North America, for example, is 16 times higher than that of people in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Four global forces affecting inequality

The report looks at the impact that four powerful global forces, or megatrends, are having on inequality around the world: technological innovation, climate change, urbanization and international migration.

Whilst technological innovation can support economic growth, offering new possibilities in fields such as health care, education, communication and productivity, there is also evidence to show that it can lead to increased wage inequality, and displace workers.

Rapid advances in areas such as biology and genetics, as well as robotics and artificial intelligence, are transforming societies at pace. New technology has the potential to eliminate entire categories of jobs but, equally, may generate entirely new jobs and innovations.

For now, however, highly skilled workers are reaping the benefits of the so-called “fourth industrial revolution”, whilst low-skilled and middle-skilled workers engaged in routine manual and cognitive tasks, are seeing their opportunities shrink.

Opportunities in a crisis

As the UN’s 2020 report on the global economy showed last Thursday, the climate crisis is having a negative impact on quality of life, and vulnerable populations are bearing the brunt of environmental degradation and extreme weather events. Climate change, according to the World Social Report, is making the world’s poorest countries even poorer, and could reverse progress made in reducing inequality among countries.

If action to tackle the climate crisis progresses as hoped, there will be job losses in carbon-intensive sectors, such as the coal industry, but the “greening” of the global economy could result in overall net employment gains, with the creation of many new jobs worldwide.

For the first time in history, more people live in urban than rural areas, a trend that is expected to continue over the coming years. Although cities drive economic growth, they are more unequal than rural areas, with the extremely wealthy living alongside the very poor.

The scale of inequality varies widely from city to city, even within a single country: as they grow and develop, some cities have become more unequal whilst, in others, inequality has declined.

Migration a ‘powerful symbol of global inequality’

The fourth megatrend, international migration, is described as both a “powerful symbol of global inequality”, and “a force for equality under the right conditions”.

Migration within countries, notes the report, tends to increase once countries begin to develop and industrialize, and more inhabitants of middle-income countries than low-income countries migrate abroad.

International migration is seen, generally, as benefiting both migrants, their countries of origin (as money is sent home) and their host countries.

In some cases, where migrants compete for low-skilled work, wages may be pushed down, increasing inequality but, if they offer skills that are in short supply, or take on work that others are not willing to do, they can have a positive effect on unemployment.

Harness the megatrends for a better world

Despite a clear widening of the gap between the haves and have-nots worldwide, the report points out that this situation can be reversed. Although the megatrends have the potential to continue divisions in society, they can also, as the Secretary-General says in his foreword, “be harnessed for a more equitable and sustainable world”. Both national governments and international organizations have a role to play in levelling the playing field and creating a fairer world for all.

Reducing inequality should, says the report, play a central role in policy-making. This means ensuring that the potential of new technology is used to reduce poverty and create jobs; that vulnerable people grow more resilient to the effects of climate change; cities are more inclusive; and migration takes place in a safe, orderly and regular manner.

Three strategies for making countries more egalitarian are suggested in the report: the promotion of equal access to opportunities (through, for example, universal access to education); fiscal policies that include measures for social policies, such as unemployment and disability benefits; and legislation that tackles prejudice and discrimination, whilst promoting greater participation of disadvantaged groups.

While action at a national level is crucial, the report declares that “concerted, coordinated and multilateral action” is needed to tackle major challenges affecting inequality within and among countries.

The report’s authors conclude that, given the importance of international cooperation, multilateral institutions such as the UN should be strengthened and action to create a fairer world must be urgently accelerated.

The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development , which provides the blueprint for a better future for people and the planet, recognizes that major challenges require internationally coordinated solutions, and contains concrete and specific targets to reduce inequality, based on income.

- World Social Report

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 10. Global Inequality

Learning objectives.

10.1. Global Stratification and Classification

- Describe global stratification

- Understand how different classification systems have developed

- Use terminology from Wallerstein’s world systems approach

- Explain the World Bank’s classification of economies

10.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

- Understand the differences between relative, absolute, and subjective poverty

- Describe the economic situation of some of the world’s most impoverished areas

- Explain the cyclical impact of the consequences of poverty

10.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

- Describe the modernization and dependency theory perspectives on global stratification

Introduction to Global Inequality

In 2000, the world entered a new millennium. In the spirit of a grand-scale New Year’s resolution, it was a time for lofty aspirations and dreams of changing the world. It was also the time of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), a series of ambitious goals set by UN member nations. The MDGs, as they became known, sought to provide a practical and specific plan for eradicating extreme poverty around the world. Nearly 200 countries signed on, and they worked to create a series of 21 targets with 60 indicators, with an ambitious goal of reaching them by 2015. The goals spanned eight categories:

- To eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- To achieve universal primary education

- To promote gender equality and empower women

- To reduce child mortality

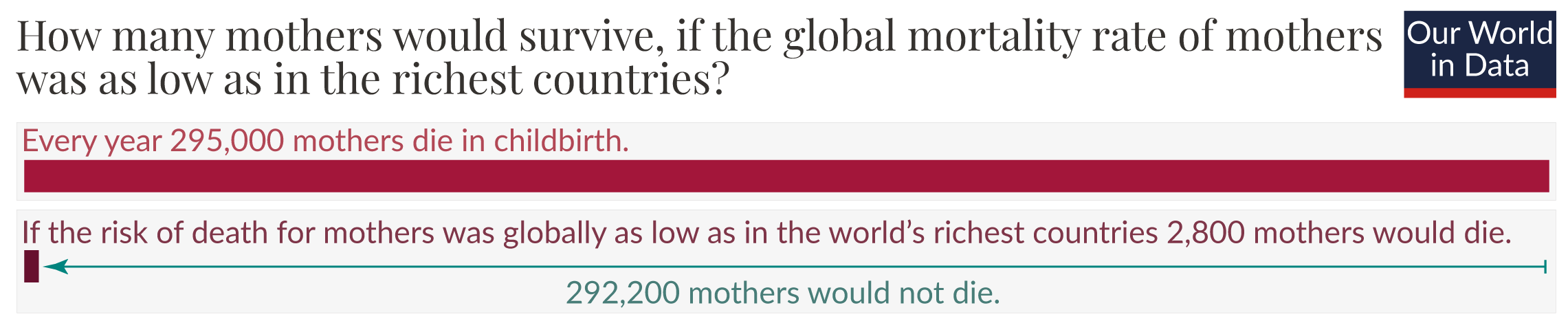

- To improve maternal health

- To combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- To ensure environmental sustainability

- To develop a global partnership for development (United Nations 2010)

There’s no question that these were well-thought-out objectives to work toward. Many years later, what has happened? As of the 2010 Outcome Document, much progress has been made toward some MDGs, while others are still lagging far behind. Goals related to poverty, education, child mortality, and access to clean water have seen much progress. But these successes show a disparity: some nations have seen great strides made, while others have seen virtually no progress. Improvements have been erratic, with hunger and malnutrition increasing from 2007 through 2009, undoing earlier achievements. Employment has also been slow to progress, as has a reduction in HIV infection rates, which have continued to outpace the number of people getting treatment. The mortality and health care rates for mothers and infants also show little advancement. Even in the areas that made gains, the successes are tenuous. And with the global recession having slowed both institutional and personal funding, the attainment of the goals is very much in question (United Nations 2010). As we consider the global effort to meet these ambitious goals, we can think about how the world’s people have ended up in such disparate circumstances. How did wealth become concentrated in some nations? What motivates companies to globalize? Is it fair for powerful countries to make rules that make it difficult for less-powerful nations to compete on the global scene? How can we address the needs of the world’s population?

10.1. Global Stratification and Classification

Just as North America’s wealth is increasingly concentrated among its richest citizens while the middle class slowly disappears, global inequality involves the concentration of resources in certain nations, significantly affecting the opportunities of individuals in poorer and less powerful countries. But before we delve into the complexities of global inequality, let us consider how the three major sociological perspectives might contribute to our understanding of it.

The functionalist perspective is a macroanalytical view that focuses on the way that all aspects of society are integral to the continued health and viability of the whole. A functionalist might focus on why we have global inequality and what social purposes it serves. This view might assert, for example, that we have global inequality because some nations are better than others at adapting to new technologies and profiting from a globalized economy, and that when core nation companies locate in peripheral nations, they expand the local economy and benefit the workers. Many models of modernization and development are functionalist, suggesting that societies with modern cultural values and beliefs are able to achieve economic development while traditional cultural values and beliefs hinder development. Cultures are either functional or dysfunctional for the economic development of societies.

Critical sociology focuses on the creation and reproduction of inequality. A critical sociologist would likely address the systematic inequality created when core nations exploit the resources of peripheral nations. For example, how many Canadian companies move operations offshore to take advantage of overseas workers who lack the constitutional protection and guaranteed minimum wages that exist in Canada? Doing so allows them to maximize profits, but at what cost?

The symbolic interaction perspective studies the day-to-day impact of global inequality, the meanings individuals attach to global stratification, and the subjective nature of poverty. Someone applying this view to global inequality might focus on understanding the difference between what someone living in a core nation defines as poverty (relative poverty, defined as being unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in your country) and what someone living in a peripheral nation defines as poverty (absolute poverty, defined as being barely able, or unable, to afford basic necessities, such as food).

Global Stratification

While stratification in Canada refers to the unequal distribution of resources among individuals, global stratification refers to this unequal distribution among nations. There are two dimensions to this stratification: gaps between nations and gaps within nations. When it comes to global inequality, both economic inequality and social inequality may concentrate the burden of poverty among certain segments of the Earth’s population (Myrdal 1970). As the table below illustrates, people’s life expectancy depends heavily on where they happen to be born.

| Country | Infant Mortality Rate | Life Expectancy |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 4.9 deaths per 1,000 live births | 81 years |

| Mexico | 17.2 deaths per 1,000 live births | 76 years |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 78.4 deaths per 1,000 live births | 55 years |

Most of us are accustomed to thinking of global stratification as economic inequality. For example, we can compare China’s average worker’s wage to Canada’s average wage. Social inequality, however, is just as harmful as economic discrepancies. Prejudice and discrimination—whether against a certain race, ethnicity, religion, or the like—can create and aggravate conditions of economic equality, both within and between nations. Think about the inequity that existed for decades within the nation of South Africa. Apartheid, one of the most extreme cases of institutionalized and legal racism, created a social inequality that earned it the world’s condemnation. When looking at inequity between nations, think also about the disregard of the crisis in Darfur by most Western nations. Since few citizens of Western nations identified with the impoverished, non-white victims of the genocide, there has been little push to provide aid.

Gender inequity is another global concern. Consider the controversy surrounding female genital mutilation. Nations that practise this female circumcision procedure defend it as a longstanding cultural tradition in certain tribes and argue that the West should not interfere. Western nations, however, decry the practice and are working to stop it.

Inequalities based on sexual orientation and gender identity exist around the globe. According to Amnesty International, a number of types of crimes are committed against individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles or sexual orientations (however those are culturally defined). From culturally sanctioned rape to state-sanctioned executions, the abuses are serious. These legalized and culturally accepted forms of prejudice and discrimination exist everywhere—from the United States to Somalia to Tibet—restricting the freedom of individuals and often putting their lives at risk (Amnesty International 2012).

Global Classification

A major concern when discussing global inequality is how to avoid an ethnocentric bias implying that less developed nations want to be like those who have attained postindustrial global power. Terms such as “developing” (nonindustrialized) and “developed” (industrialized) imply that nonindustrialized countries are somehow inferior, and must improve to participate successfully in the global economy, a label indicating that all aspects of the economy cross national borders. We must take care in how we delineate different countries. Over time, terminology has shifted to make way for a more inclusive view of the world.

Cold War Terminology

Cold War terminology was developed during the Cold War era (1945–1980) when the world was divided between capitalist and communist economic systems (and their respective geopolitical aspirations). Familiar and still used by many, it involves classifying countries into first world, second world, and third world nations based on respective economic development and standards of living. When this nomenclature was developed, capitalistic democracies such as the United States, Canada, and Japan were considered part of the first world . The poorest, most undeveloped countries were referred to as the third world and included most of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The second world was the socialist world or Soviet bloc: industrially developed but organized according to a state socialist or communist model of political economy. Later, sociologist Manual Castells (1998) added the term fourth world to refer to stigmatized minority groups that were denied a political voice all over the globe (indigenous minority populations, prisoners, and the homeless, for example).

Also during the Cold War, global inequality was described in terms of economic development. Along with developing and developed nations, the terms “less-developed nation” and “underdeveloped nation” were used. Modernization theory suggested that societies moved through natural stages of development as they progressed toward becoming developed societies (i.e., stable, democratic, market oriented, and capitalist). The economist Walt Rustow (1960) provided a very influential schema of development when he described the linear sequence of developmental stages: traditional society (agrarian based with low productivity); pre-take off society (state formation and shift to industrial production, expansion of markets, and generation of surplus); take-off (rapid self-sustained economic growth and reinvestment of capital in the economy); maturity (a modern industrialized economy, highly capitalized and technologically advanced); the age of high mass-consumption (shift from basic goods to “durable” goods (TVs, cars, refrigerators, etc.), and luxury goods, general prosperity, egalitarianism). Like most versions of modernization theory, Rustow’s schema describes a linear process of development culminating in the formation of democratic, capitalist societies. It was clearly in line with Cold War ideology, but it also echoed widely held beliefs about the idea of social progress as an evolutionary process.

However, as “natural” as these stages of development were taken to be, they required creation, securing, protection, and support. This was the era when the idea of geopolitical noblesse oblige (first-world responsibility) took root, suggesting that the so-called developed nations should provide foreign aid to the less-developed and underdeveloped nations in order to raise their standard of living.

Immanuel Wallerstein: World Systems Approach

Wallerstein’s (1979) world systems approach uses an economic and political basis to understand global inequality. Development and underdevelopment were not stages in a natural process of gradual modernization, but the product of power relations and colonialism. He conceived the global economy as a complex historical system supporting an economic hierarchy that placed some nations in positions of power with numerous resources and other nations in a state of economic subordination. Those that were in a state of subordination faced significant obstacles to mobilization.

Core nations are dominant capitalist countries, highly industrialized, technological, and urbanized. For example, Wallerstein contends that the United States is an economic powerhouse that can support or deny support to important economic legislation with far-reaching implications, thus exerting control over every aspect of the global economy and exploiting both semi-peripheral and peripheral nations. The free trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) are examples of how a core nation can leverage its power to gain the most advantageous position in the matter of global trade.

Peripheral nations have very little industrialization; what they do have often represents the outdated castoffs of core nations, the factories and means of production owned by core nations, or the resources exploited by core nations. They typically have unstable government and inadequate social programs, and they are economically dependent on core nations for jobs and aid. There are abundant examples of countries in this category. Check the label of your jeans or sweatshirt and see where it was made. Chances are it was a peripheral nation such as Guatemala, Bangladesh, Malaysia, or Colombia. You can be sure the workers in these factories, which are owned or leased by global core nation companies, are not enjoying the same privileges and rights as Canadian workers.

Semi-peripheral nations are in-between nations, not powerful enough to dictate policy but nevertheless acting as a major source for raw material. They are an expanding middle-class marketplace for core nations, while also exploiting peripheral nations. Mexico is an example, providing abundant cheap agricultural labour to the United States and Canada, and supplying goods to the North American market at a rate dictated by U.S. and Canadian consumers without the constitutional protections offered to U.S. or Canadian workers.

World Bank Economic Classification by Income

While there is often criticism of the World Bank, both for its policies and its method of calculating data, it is still a common source for global economic data. When using the World Bank categorization to classify economies, the measure of GNI, or gross national income, provides a picture of the overall economic health of a nation. Gross national income equals all goods and services plus net income earned outside the country by nationals and corporations headquartered in the country doing business out of the country, measured in U.S. dollars. In other words, the GNI of a country includes not only the value of goods and services inside the country, but also the value of income earned outside the country if it is earned by foreign nationals or foreign businesses. That means that multinational corporations that might earn billions in offices and factories around the globe are considered part of a core nation’s GNI if they have headquarters in the core nations. Along with tracking the economy, the World Bank tracks demographics and environmental health to provide a complete picture of whether a nation is high income, middle income, or low income.

High-Income Nations

The World Bank defines high-income nations as having a GNI of at least $12,276 per capita. It separates out the OECD (Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development) countries, a group of 34 nations whose governments work together to promote economic growth and sustainability. According to the Work Bank (2011), in 2010, the average GNI of a high-income nation belonging to the OECD was $40,136 per capita; on average, 77 percent of the population in these nations was urban. Some of these countries include Canada, the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom (World Bank 2011). In 2010, the average GNI of a high-income nation that did not belong to the OECD was $23,839 per capita and 83 percent was urban. Examples of these countries include Saudi Arabia and Qatar (World Bank 2011).

There are two major issues facing high-income countries: capital flight and deindustrialization. Capital flight refers to the movement (flight) of capital from one nation to another, as when General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler close Canadian factories in Ontario and open factories in Mexico. Deindustrialization , a related issue, occurs as a consequence of capital flight, as no new companies open to replace jobs lost to foreign nations. As expected, global companies move their industrial processes to the places where they can get the most production with the least cost, including the costs for building infrastructure, training workers, shipping goods, and, of course, paying employee wages. This means that as emerging economies create their own industrial zones, global companies see the opportunity for existing infrastructure and much lower costs. Those opportunities lead to businesses closing the factories that provide jobs to the middle-class within core nations and moving their industrial production to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations.

Making Connections: the Big Picture

Capital flight, outsourcing, and jobs in canada.

As mentioned above, capital flight describes jobs and infrastructure moving from one nation to another. Look at the manufacturing industries in Ontario. Ontario has been the traditional centre of manufacturing in Canada since the 19th century. At the turn of the 21st century, 18 percent of Ontario’s labour market was made up of manufacturing jobs in industries like automobile manufacturing, food processing, and steel production. At the end of 2013, only 11 percent of the labour force worked in manufacturing. Between 2000 and 2013, 290,000 manufacturing jobs were lost (Tiessen 2014). Often the culprit is portrayed as the high value of the Canadian dollar compared to the American dollar. Because of the high value of Canada’s oil exports, international investors have driven up the value of the Canadian dollar in a process referred to as Dutch disease, the relationship between an increase in the development of natural resources and a decline in manufacturing. Canadian-manufactured products are too expensive as a result. However, this is just another way of describing the general process of capital flight to locations that have cheaper manufacturing costs and cheaper labour. Since the introduction of the North American free trade agreements (the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 1988 and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994), the ending of the tariff system that protected branch plant manufacturing in Canada has enabled U.S. companies to shift production to low-wage regions south of the border and in Mexico.

Capital flight also occurs when services (as opposed to manufacturing) are relocated. Chances are if you have called the tech support line for your cell phone or internet provider, you have spoken to someone halfway across the globe. This professional might tell you her name is Susan or Joan, but her accent makes it clear that her real name might be Parvati or Indira. It might be the middle of the night in that country, yet these service providers pick up the line saying, “good morning,” as though they are in the next town over. They know everything about your phone or your modem, often using a remote server to log in to your home computer to accomplish what is needed. These are the workers of the 21st century. They are not on factory floors or in traditional sweatshops; they are educated, speak at least two languages, and usually have significant technology skills. They are skilled workers, but they are paid a fraction of what similar workers are paid in Canada. For Canadian and multinational companies, the equation makes sense. India and other semi-peripheral countries have emerging infrastructures and education systems to fill their needs, without core nation costs.

As services are relocated, so are jobs. In Canada, unemployment is high. Many university-educated people are unable to find work, and those with only a high school diploma are in even worse shape. We have, as a country, outsourced ourselves out of jobs, and not just menial jobs, but white-collar work as well. But before we complain too bitterly, we must look at the culture of consumerism that Canadians embrace. A flat screen television that might have cost $1,000 a few years ago is now $350. That cost saving has to come from somewhere. When Canadians seek the lowest possible price, shop at big box stores for the biggest discount they can get, and generally ignore other factors in exchange for low cost, they are building the market for outsourcing. And as the demand is built, the market will ensure it is met, even at the expense of the people who wanted that television in the first place.

Middle-Income Nations

The World Bank defines lower middle income countries as having a GNI that ranges from $1,006 to $3,975 per capita and upper middle income countries as having a GNI ranging from $3,976 to $12,275 per capita. In 2010, the average GNI of an upper middle income nation was $5,886 per capita with a population that was 57 percent urban. Brazil, Thailand, China, and Namibia are examples of middle-income nations (World Bank 2011).

Perhaps the most pressing issue for middle-income nations is the problem of debt accumulation. As the name suggests, debt accumulation is the buildup of external debt, when countries borrow money from other nations to fund their expansion or growth goals. As the uncertainties of the global economy make repaying these debts, or even paying the interest on them, more challenging, nations can find themselves in trouble. Once global markets have reduced the value of a country’s goods, it can be very difficult to manage the debt burden. Such issues have plagued middle-income countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as East Asian and Pacific nations (Dogruel and Dogruel 2007). By way of example, even in the European Union, which is composed of more core nations than semi-peripheral nations, the semi-peripheral nations of Italy, Portugal, and Greece face increasing debt burdens. The economic downturns in these countries are threatening the economy of the entire European Union.

Low-Income Nations

The World Bank defines low-income countries as nations having a GNI of $1,005 per capita or less in 2010. In 2010, the average GNI of a low-income nation was $528 and the average population was 796,261,360, with 28 percent located in urban areas. For example, Myanmar, Ethiopia, and Somalia are considered low-income countries. Low-income economies are primarily found in Asia and Africa, where most of the world’s population lives (World Bank 2011). There are two major challenges that these countries face: women are disproportionately affected by poverty (in a trend toward a global feminization of poverty) and much of the population lives in absolute poverty. In some ways, the term global feminization of poverty says it all: around the world, women are bearing a disproportionate percentage of the burden of poverty. This means more women live in poor conditions, receive inadequate health care, bear the brunt of malnutrition and inadequate drinking water, and so on. Throughout the 1990s, data indicated that while overall poverty rates were rising, especially in peripheral nations, the rates of impoverishment increased nearly 20 percent more for women than for men (Mogadham 2005). Why is this happening? While there are myriad variables affecting women’s poverty, research specializing in this issue identifies three causes:

- The expansion of female-headed households

- The persistence and consequences of intra-household inequalities and biases against women

- The implementation of neoliberal economic policies around the world (Mogadham 2005)

In short, this means that within an impoverished household, women are more likely to go hungry than men; in agricultural aid programs, women are less likely to receive help than men; and often, women are left taking care of families with no male counterpart.

10.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

What does it mean to be poor? Does it mean being a single mother with two kids in Toronto, waiting for her next paycheque before she can buy groceries? Does it mean living with almost no furniture in your apartment because your income does not allow for extras like beds or chairs? Or does it mean the distended bellies of the chronically malnourished throughout the peripheral nations of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia? Poverty has a thousand faces and a thousand gradations; there is no single definition that pulls together every part of the spectrum. You might feel you are poor if you can’t afford cable television or your own car. Every time you see a fellow student with a new laptop and smartphone you might feel that you, with your ten-year-old desktop computer, are barely keeping up. However, someone else might look at the clothes you wear and the calories you consume and consider you rich.

Types of Poverty

Social scientists define global poverty in different ways, taking into account the complexities and the issues of relativism described above. Relative poverty is a state of living where people can afford necessities but are unable to meet their society’s average standard of living. They are unable to participate in society in a meaningful way. People often disparage “keeping up with the Joneses”—the idea that you must keep up with the neighbours’ standard of living to not feel deprived. But it is true that you might feel “poor” if you are living without a car to drive to and from work, without any money for a safety net should a family member fall ill, and without any “extras” beyond just making ends meet. Contrary to relative poverty, people who live in absolute poverty lack even the basic necessities, which typically include adequate food, clean water, safe housing, and access to health care. Absolute poverty is defined by the World Bank (2011) as when someone lives on less than a dollar a day. A shocking number of people—88 million—live in absolute poverty, and close to 3 billion people live on less than $2.50 a day (Shah 2011). If you were forced to live on $2.50 a day, how would you do it? What would you deem worthy of spending money on, and what could you do without? How would you manage the necessities—and how would you make up the gap between what you need to live and what you can afford?

Subjective poverty describes poverty that is composed of many dimensions; it is subjectively present when your actual income does not meet your expectations and perceptions. With the concept of subjective poverty, the poor themselves have a greater say in recognizing when it is present. In short, subjective poverty has more to do with how a person or a family defines themselves. This means that a family subsisting on a few dollars a day in Nepal might think of themselves as doing well, within their perception of normal. However, a Westerner travelling to Nepal might visit the same family and see extreme need.

Making Connections: the Big Pictures

The underground economy around the world.

What do the driver of an unlicensed speedy cab in St. Catharines, a piecework seamstress working from her home in Mumbai, and a street tortilla vendor in Mexico City have in common? They are all members of the underground economy , a loosely defined unregulated market unhindered by taxes, government permits, or human protections. Official statistics before the 2008 worldwide recession posit that the underground economy accounted for over 50 percent of non-agricultural work in Latin America; the figure went as high as 80 percent in parts of Asia and Africa (Chen 2001). A recent article in the Wall Street Journal discusses the challenges, parameters, and surprising benefits of this informal marketplace. The wages earned in most underground economy jobs, especially in peripheral nations, are a pittance—a few rupees for a handmade bracelet at a market, or maybe 250 rupees (around C$4.50) for a day’s worth of fruit and vegetable sales (Barta 2009). But these tiny sums mark the difference between survival and extinction for the world’s poor.

The underground economy has never been viewed very positively by global economists. After all, its members do not pay taxes, do not take out loans to grow their businesses, and rarely earn enough to put money back into the economy in the form of consumer spending. But according to the International Labour Organization (an agency of the United Nations), some 52 million people worldwide will lose their jobs due to the 2008 recession. And while those in core nations know that unemployment rates and limited government safety nets can be frightening, it is nothing compared to the loss of a job for those barely eking out an existence. Once that job disappears, the chance of staying afloat is very slim.

Within the context of this recession, some see the underground economy as a key player in keeping people alive. Indeed, an economist at the World Bank credits jobs created by the informal economy as a primary reason why peripheral nations are not in worse shape during this recession. Women in particular benefit from the informal sector. The majority of economically active women in peripheral nations are engaged in the informal sector, which is somewhat buffered from the economic downturn. The flip side, of course, is that it is equally buffered from the possibility of economic growth.

Even in Canada, the informal economy exists, although not on the same scale as in peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. It might include under-the-table nannies, gardeners, and housecleaners, as well as unlicensed street vendors and taxi drivers. There are also those who run informal businesses, like daycares or salons, from their houses. Analysts estimate that this type of of labour may make up 10 to 13.5 percent of the overall Canadian economy (Schneider and Enste 2000), a number that will likely grow as companies reduce head counts, leaving more workers to seek other options. In the end, the article suggests that, whether selling medicinal wines in Thailand or woven bracelets in India, the workers of the underground economy at least have what most people want most of all: a chance to stay afloat (Barta 2009).

Who Are the Impoverished?

Who are the impoverished? Who is living in absolute poverty? Most of us would guess correctly that the richest countries typically have the fewest people. Compare Canada, which possesses a relatively small slice of the population pie and owns a large slice of the wealth pie, with India. These disparities have the expected consequence. The poorest people in the world are women in peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. For women, the rate of poverty is particularly exacerbated by the pressure on their time. In general, time is one of the few luxuries the very poor have, but study after study has shown that women in poverty, who are responsible for all family comforts as well as any earnings they can make, have less of it. The result is that while men and women may have the same rate of economic poverty, women are suffering more in terms of overall well-being ( Buvinić 1997). It is harder for females to get credit to expand businesses, to take the time to learn a new skill, or to spend extra hours improving their craft so as to be able to earn at a higher rate.

The majority of the poorest countries in the world are in Africa. That is not to say there is not diversity within the countries of that continent; countries like South Africa and Egypt have much lower rates of poverty than Angola and Ethiopia, for instance. Overall, African income levels have been dropping relative to the rest of the world, meaning that Africa as a whole is getting relatively poorer. Exacerbating the problem, 2011 saw a drought in northeast Africa that brought starvation to many in the region.

Why is Africa in such dire straits? Much of the continent’s poverty can be traced to the availability of land, especially arable land (land that can be farmed). Centuries of struggle over land ownership have meant that much useable land has been ruined or left unfarmed, while many countries with inadequate rainfall have never set up an infrastructure to irrigate. Many of Africa’s natural resources were long ago taken by colonial forces, leaving little agricultural and mineral wealth on the continent.

Further, African poverty is worsened by civil wars and inadequate governance that are the result of a continent re-imagined with artificial colonial borders and leaders. Consider the example of Rwanda. There, two ethnic groups cohabited with their own system of hierarchy and management until Belgians took control of the country in 1915 and rigidly confined members of the population into two unequal ethnic groups. While, historically, members of the Tutsi group held positions of power, the involvement of Belgians led to the Hutu’s seizing power during a 1960s revolt. This ultimately led to a repressive government and genocide against Tutsis that left hundreds of thousands of Rwandans dead or living in diaspora (U.S. Department of State 2011c). The painful rebirth of a self-ruled Africa has meant many countries bear ongoing scars as they try to see their way toward the future (World Poverty 2012a).

While the majority of the world’s poorest countries are in Africa, the majority of the world’s poorest people are in Asia. As in Africa, Asia finds itself with disparity in the distribution of poverty, with Japan and South Korea holding much more wealth than India and Cambodia. In fact, most poverty is concentrated in South Asia. One of the most pressing causes of poverty in Asia is simply the pressure that the size of the population puts on its resources. In fact, many believe that China’s success in recent times has much to do with its draconian population control rules. According to the U.S. State Department, China’s market-oriented reforms have contributed to its significant reduction of poverty and the speed at which it has experienced an increase in income levels (U.S. Department of State 2011b). However, every part of Asia has felt the global recession, from the poorest countries whose aid packages were hit, to the more industrialized ones whose own industries slowed down. These factors make the poverty on the ground unlikely to improve any time soon (World Poverty 2012b).

Latin America

Poverty rates in some Latin American countries like Mexico have improved recently, in part due to investment in education. But other countries like Paraguay and Peru continue to struggle. Although there is a large amount of foreign investment in this part of the world, it tends to be higher-risk speculative investment (rather than the more stable long-term investment Europe often makes in Africa and Asia). The volatility of these investments means that the region has been unable to leverage them, especially when mixed with high interest rates for aid loans. Further, internal political struggles, illegal drug trafficking, and corrupt governments have added to the pressure (World Poverty 2012c).

Argentina is one nation that suffered from increasing debt load in the early 2000s, as the country tried to fight hyperinflation by fixing the peso to the U.S. dollar. The move hurt the nation’s ability to be competitive in the world market and ultimately created chronic deficits that could only be financed by massive borrowing from other countries and markets. By 2001, so much money was leaving the country that there was a financial panic, leading to riots and ultimately, the resignation of the president (U.S. Department of State 2011a).

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The true cost of a t-shirt.

Most of us do not pay too much attention to where our favourite products are made. And certainly when you are shopping for a cheap T-shirt, you probably do not turn over the label, check who produced the item, and then research whether or not the company has fair labour practices. In fact it can be very difficult to discover where exactly the items we use everyday have come from. Nevertheless, the purchase of a T-shirt involves us in a series of social relationships that ties us to the lives and working conditions of people around the world.

On April 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, collapsed killing 1,129 garment workers. The building, like 90 percent of Dhaka’s 4,000 garment factories, was structurally unsound. Garment workers in Bangladesh work under unsafe conditions for as little as $38 a month so that North American consumers can purchase T-shirts in the fashionable colours of the season for as little as $5. The workers at Rana Plaza were in fact making clothes for the Joe Fresh label—the signature popular Loblaw brand—when the building collapsed. Having been put on the defensive for their overseas sweatshop practices, companies like Loblaw have pledged to improve working conditions in their suppliers’ factories, but compliance has proven difficult to ensure because of the increasingly complex web of globalized production (MacKinnon and Strauss 2013).

At one time, the garment industry was important in Canada, centred on Spadina Avenue in Toronto and Chabanel Street in Montreal. But over the last two decades of globalization, Canadian consumers have become increasingly tied through popular retail chains to a complex network of outsourced garment production that stretches from China, through Southeast Asia, to Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The early 1990s saw the economic opening of China when suddenly millions of workers were available to produce and manufacture consumer items for Westerners at a fraction of the cost of Western production. Manufacturing that used to take place in Canada moved overseas. Over the ensuing years, the Chinese began to outsource production to regions with even cheaper labour: Vietnam, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. The outsourcing was outsourced. The result is that when a store like Loblaw places an order, it usually works through agents who in turn source and negotiate the price of materials and production from competing locales around the globe.

Most of the T-shirts that we wear in Canada today begin their life in the cotton fields of arid west China, which owe their scale and efficiency to the collectivization projects of centralized state socialism. However, as the cost of Chinese labour has incrementally increased since the 1990s, the Chinese have moved into the role of connecting Western retailers and designers with production centres elsewhere. In a global division of labour, if agents organize the sourcing, production chain and logistics, Western retailers can focus their skill and effort on retail marketing. It was in this context that Bangladesh went from having a few dozen garment factories to several thousand. The garment industry now accounts for 80 percent of Bangladesh’s export earnings. Unfortunately, although there are legal safety regulations and inspections in Bangladesh, the rapid expansion of the industry has exceeded the ability of underfunded state agencies to enforce them.

The globalization of production makes it difficult to follow the links between the purchasing of a T-shirt in a Canadian store and the chain of agents, garment workers, shippers, and agricultural workers whose labour has gone into producing it and getting it to the store. Our lives are tied to this chain each time we wear a T-shirt, yet the history of its production and the lives it has touched are more or less invisible to us. It becomes even more difficult to do something about the working conditions of those global workers when even the retail stores are uncertain about where the shirts come form. There is no international agency that can enforce compliance with safety or working standards. Why do you think worker safety standards and factory building inspections have to be imposed by government regulations rather than being simply an integral part of the production process? Why does it seem normal that the issue of worker safety in garment factories is set up in this way? Why does this make it difficult to resolve or address the issue?

The fair trade movement has pushed back against the hyper-exploitation of global workers and forced stores like Loblaw to try to address the unsafe conditions in garment factories like Rana Plaza. Organizations like the Better Factories Cambodia program inspect garment production regularly in Cambodia, enabling stores like Mountain Equipment Co-op to purchase reports on the factory chains it relies on. After the Rana Plaza disaster, Loblaw signed an Accord of Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh to try to ensure safety compliance of their suppliers. However the bigger problem seems to originate with our desire to be able to purchase a T-shirt for $5 in the first place.

Consequences of Poverty

Not surprisingly, the consequences of poverty are often also causes. The poor experience inadequate health care, limited education, and the inaccessibility of birth control. Those born into these conditions are incredibly challenged in their efforts to break out since these consequences of poverty are also causes of poverty, perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage.

According to sociologists Neckerman and Torche (2007) in their analysis of global inequality studies, the consequences of poverty are many. They have divided the consequences into three areas. The first, termed “the sedimentation of global inequality,” relates to the fact that once poverty becomes entrenched in an area, it is typically very difficult to reverse. As mentioned above, poverty exists in a cycle where the consequences and causes are intertwined. The second consequence of poverty is its effect on physical and mental health. Poor people face physical health challenges, including malnutrition and high infant mortality rates. Mental health is also detrimentally affected by the emotional stresses of poverty, with relative deprivation carrying the strongest effect. Again, as with the ongoing inequality, the effects of poverty on mental and physical health become more entrenched as time goes on. Neckerman and Torche’s third consequence of poverty is the prevalence of crime. Cross-nationally, crime rates are higher, particularly with violent crime, in countries with higher levels of income inequality (Fajnzylber, Lederman, and Loayza 2002).

While most of us are accustomed to thinking of slavery in terms of pre–Civil War America, modern-day slavery goes hand in hand with global inequality. In short, slavery refers to any time people are sold, treated as property, or forced to work for little or no pay. Just as in pre–Civil War America, these humans are at the mercy of their employers. Chattel slavery , the form of slavery practised in the pre–Civil War American South, is when one person owns another as property. Child slavery, which may include child prostitution, is a form of chattel slavery. Debt bondage , or bonded labour, involves the poor pledging themselves as servants in exchange for the cost of basic necessities like transportation, room, and board. In this scenario, people are paid less than they are charged for room and board. When travel is involved, people can arrive in debt for their travel expenses and be unable to work their way free, since their wages do not allow them to ever get ahead.

The global watchdog group Anti-Slavery International recognizes other forms of slavery: human trafficking (where people are moved away from their communities and forced to work against their will), child domestic work and child labour, and certain forms of servile marriage, in which women are little more than chattel slaves (Anti-Slavery International 2012).

10.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

As with any social issue, global or otherwise, there are a variety of theories that scholars develop to study the topic. The two most widely applied perspectives on global stratification are modernization theory and dependency theory.

Modernization Theory

According to modernization theory, low-income countries are affected by their lack of industrialization and can improve their global economic standing through:

- An adjustment of cultural values and attitudes to work

- Industrialization and other forms of economic growth (Armer and Katsillis 2010)

Critics point out the inherent ethnocentric bias of this theory. It supposes all countries have the same resources and are capable of following the same path. In addition, it assumes that the goal of all countries is to be as “developed” as possible (i.e., like the model of capitalist democracies provided by Canada or the United States). There is no room within this theory for the possibility that industrialization and technology are not the best goals.

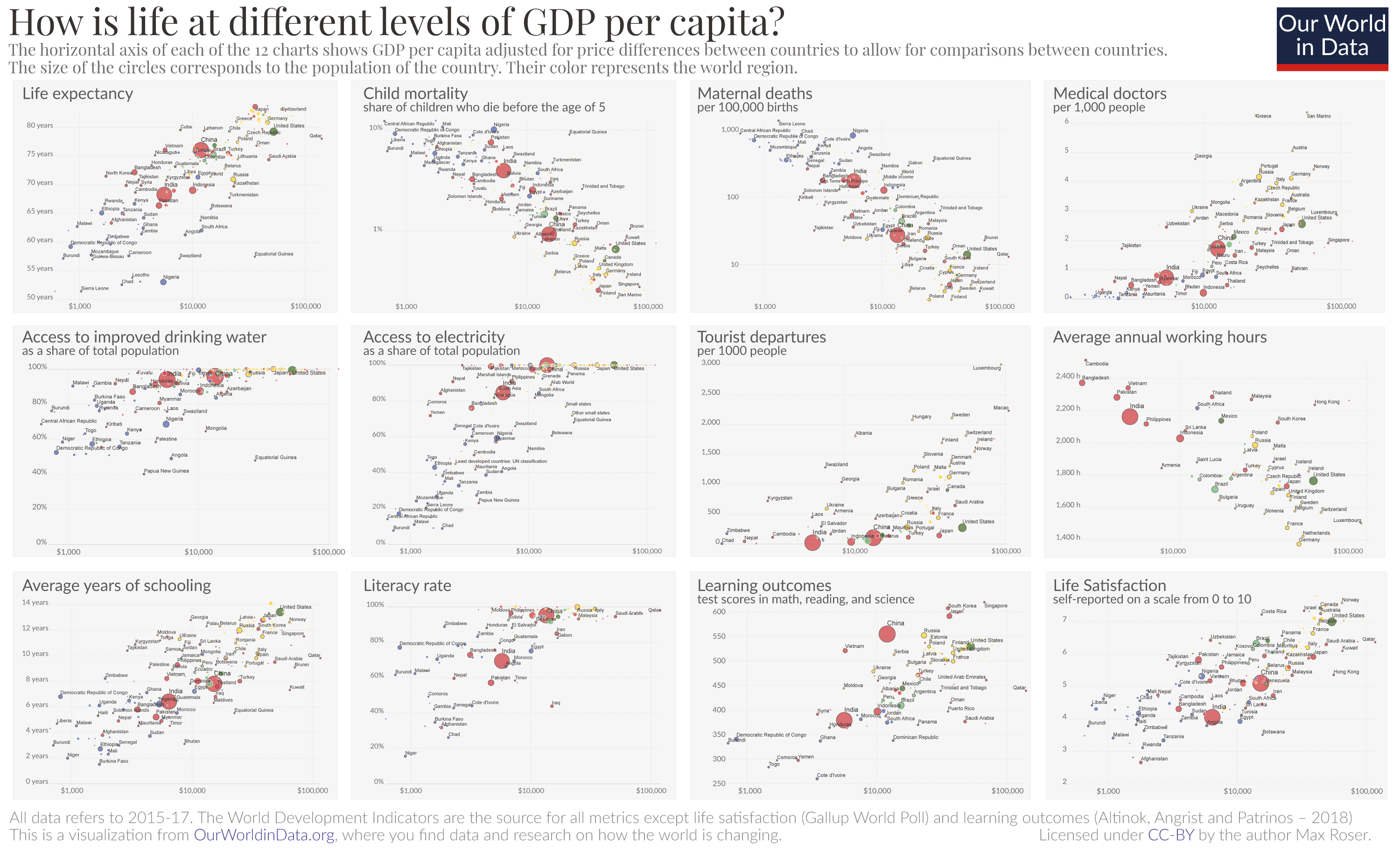

There is, of course, some basis for this assumption. Data show that core nations tend to have lower maternal and child mortality rates, longer lifespans, and less absolute poverty. It is also true that in the poorest countries, millions of people die from the lack of clean drinking water and sanitation facilities, which are benefits most of us take for granted. At the same time, the issue is more complex than the numbers might suggest. Cultural equality, history, community, and local traditions are all at risk as modernization pushes into peripheral countries. The challenge, then, is to allow the benefits of modernization while maintaining a cultural sensitivity to what already exists.

Dependency Theory

Dependency theory was created in part as a response to the Western-centric mindset of modernization theory. It states that global inequality is primarily caused by core nations (or high-income nations) exploiting semi-peripheral and peripheral nations (or middle-income and low-income nations), creating a cycle of dependence (Hendricks 2010). In the period of colonialism, core or metropolis nations created the conditions for the underdevelopment of peripheral or hinterland nations through a metropolis-hinterland relationship . The resources of the hinterlands were shipped to the metropolises where they were converted into manufactured goods and shipped back for consumption in the hinterlands. The hinterlands were used as the source of cheap resources and were unable to develop competitive manufacturing sectors of their own.

Dependency theory states that as long as peripheral nations are dependent on core nations for economic stimulus and access to a larger piece of the global economy, they will never achieve stable and consistent economic growth. Further, the theory states that since core nations, as well as the World Bank, choose which countries to make loans to, and for what they will loan funds, they are creating highly segmented labour markets that are built to benefit the dominant market countries.

At first glance, it seems this theory ignores the formerly low-income nations that are now considered middle-income nations and are on their way to becoming high-income nations and major players in the global economy, such as China. But some dependency theorists would state that it is in the best interests of core nations to ensure the long-term usefulness of their peripheral and semi-peripheral partners. Following that theory, sociologists have found that entities are more likely to outsource a significant portion of a company’s work if they are the dominant player in the equation; in other words, companies want to see their partner countries healthy enough to provide work, but not so healthy as to establish a threat (Caniels, Roeleveld, and Roeleveld 2009).

Globalization Theory

Globalization theory approaches global inequality by focusing less on the relationship between dependent and core nations, and more on the international flows of capital investment and disinvestment in an increasingly integrated world market. Since the 1970s, capital accumulation has taken place less and less in the context of national economies. Rather, as we saw in the example of the garment industry, capital circulates on a global scale, leading to a global reordering of inequalities both between nations and within nations. The production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services are administratively and technologically integrated on a worldwide basis. Effectively, we no longer live and act in the self-enclosed spaces of national states.

The core components of the “globalization project” (McMichael 2012)—the project to transform the world into a single seamless market—are the imposition of open “free” markets across national borders, the deregulation of trade and investment, and the privatization of public goods and services. Development has been redefined from the model of nationally managed economic growth to “participation in the world market” according to the World Bank’s World Development Report 1980 (cited in McMichael 2012, pp. 112-113). The global economy as a whole, not modernized national economies, emerges as the site of development. Within this model, the world and its resources are reorganized and managed on the basis of the free trade of goods and services and the free circulation of capital by democratically unaccountable political and economic elite organizations like the G7, the WTO (World Trade Organization), GATT (General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs), the World Bank and IMF (International Monetary Fund), and the various international measures used to liberalize the global economy (the 1995 Agreement on Agriculture, Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs), Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)).

According to globalization theory, the outcome of the globalization project has been the redistribution of wealth and poverty on a global scale. Outsourcing shifts production to low-wage enclaves, displacement leads to higher unemployment rates in the traditionally wealthy global north, people migrate from rural to urban areas and “slum cities” and illegally from poor countries to rich countries, while large numbers of workers simply become redundant to global production and turn to informal, casual labour. The anti-globalization movement has emerged as a counter-movement to define an alternative, non-corporate global project based on environmental sustainability, food sovereignty, labour rights, and democratic accountability.

Making Connections: Careers in Sociology

Factory girls.

We’ve examined functionalist and conflict theorist perspectives on global inequality, as well as modernization and dependency theories. How might a symbolic interactionist approach this topic?

The book Factory Girls: From Village to City in Changing China , by Leslie T. Chang, provides this opportunity. Chang follows two young women (Min and Chunming) who are employed at a handbag plant. They help manufacture coveted purses and bags for the global market. As part of the growing population of young people who are leaving behind the homesteads and farms of rural China, these female factory workers are ready to enter the urban fray and pursue an income much higher than they could have earned back home.

Although Chang’s study is based in a town many have never heard of (Dongguan), this city produces one-third of all shoes on the planet (Nike and Reebok are major manufacturers here) and 30 percent of the world’s computer disk drives, in addition to a wide range of apparel (Chang 2008).

But Chang’s focus is less centred on this global phenomenon on a large scale and more concerned with how it affects these two women. As a symbolic interactionist would do, Chang examines the daily lives and interactions of Min and Chunming—their workplace friendships, family relations, gadgets, and goods—in this evolving global space where young women can leave tradition behind and fashion their own futures. What she discovers is that the women are definitely subject to conditions of hyper-exploitation, but are also disembedded from the rural, Confucian, traditional culture in a manner that provides them with unprecedented personal freedoms. They go from the traditional family affiliations and narrow options of the past to life in a “perpetual present.” Friendships are fleeting and fragile, forms of life are improvised and sketchy, and everything they do is marked by the goals of upward mobility, resolute individualism, and an obsession with prosperity. Life for the women factory workers in Dongguan is an adventure, compared to their fate in rural village life, but one characterized by gruelling work, insecurity, isolation, and loneliness. Chang writes, “Dongguan was a place without memory.”

absolute poverty the state where one is barely able, or unable, to afford basic necessities

anti-globalization movement a global counter-movement based on principles of environmental sustainability, food sovereignty, labour rights, and democratic accountability that challenges the corporate model of globalization

capital flight the movement (flight) of capital from one nation to another, via jobs and resources

chattel slavery a form of slavery in which one person owns another

core nations dominant capitalist countries

debt accumulation the buildup of external debt, wherein countries borrow money from other nations to fund their expansion or growth goals

debt bondage when people pledge themselves as servants in exchange for money for passage, and are subsequently paid too little to regain their freedom

deindustrialization the loss of industrial production, usually to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations where the costs are lower

dependency theory theory stating that global inequity is due to the exploitation of peripheral and semi-peripheral nations by core nations

first world a term from the Cold War era that is used to describe industrialized capitalist democracies

fourth world a term that describes stigmatized minority groups who have no voice or representation on the world stage

global feminization a pattern that occurs when women bear a disproportionate percentage of the burden of poverty

global inequality the concentration of resources in core nations and in the hands of a wealthy minority

global stratification the unequal distribution of resources between countries

gross national income (GNI) the income of a nation calculated based on goods and services produced, plus income earned by citizens and corporations headquartered in that country

metropolis-hinterland relationship the relationship between nations when resources of the hinterlands are shipped to the metropolises where they are converted into manufactured goods and shipped back to the hinterlands for consumption

modernization theory a theory that low-income countries can improve their global economic standing by industrialization of infrastructure and a shift in cultural attitudes toward work

peripheral nations nations on the fringes of the global economy, dominated by core nations, with very little industrialization

relative poverty the state of poverty where one is unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in the country

second world a term from the Cold War era that describes nations with moderate economies and standards of living

semi-peripheral nations in-between nations, not powerful enough to dictate policy but acting as a major source of raw materials and providing an expanding middle-class marketplace

subjective poverty a state of poverty subjectively present when one’s actual income does not meet one’s expectations

third world a term from the Cold War era that refers to poor, nonindustrialized countries

underground economy an unregulated economy of labour and goods that operates outside of governance, regulatory systems, or human protections

Section Summary

10.1. Global Stratification and Classification Stratification refers to the gaps in resources both between nations and within nations. While economic equality is of great concern, so is social equality, like the discrimination stemming from race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and/or sexual orientation. While global inequality is nothing new, several factors, like the global marketplace and the pace of information sharing, make it more relevant than ever. Researchers try to understand global inequality by classifying it according to factors such as how industrialized a nation is, whether it serves as a means of production or as an owner, and what income it produces.

When looking at the world’s poor, we first have to define the difference between relative poverty, absolute poverty, and subjective poverty. While those in relative poverty might not have enough to live at their country’s standard of living, those in absolute poverty do not have, or barely have, basic necessities such as food. Subjective poverty has more to do with one’s perception of one’s situation. North America and Europe are home to fewer of the world’s poor than Africa, which has highest number of poor countries, or Asia, which has the most people living in poverty. Poverty has numerous negative consequences, from increased crime rates to a detrimental impact on physical and mental health.

10.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification Modernization theory, dependency theory, and globalization theory are three of the most common lenses sociologists use when looking at the issues of global inequality. Modernization theory posits that countries go through evolutionary stages and that industrialization and improved technology are the keys to forward movement. Dependency theory sees modernization theory as Eurocentric and patronizing. With this theory, global inequality is the result of core nations creating a cycle of dependence by exploiting resources and labour in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries. Globalization theory argues that the division between the wealthy and the poor is now organized in the context of a single, integrated global economy rather than between core and peripheral nations.

Section Quiz

10.1. Global Stratification and Classification 1. A sociologist who focuses on the way that multinational corporations headquartered in core nations exploit the local workers in their peripheral nation factories is using a _________ perspective to understand the global economy.

- Critical sociology

- Symbolic interactionist

2. A ____________ perspective theorist might find it particularly noteworthy that wealthy corporations improve the quality of life in peripheral nations by providing workers with jobs, pumping money into the local economy, and improving transportation infrastructure.

3. A sociologist working from a symbolic interaction perspective would ____________________________________.

- Study how inequality is created and reproduced

- Study how corporations can improve the lives of their low-income workersTtry to understand how companies provide an advantage to high-income nations compared to low-income nations

- Want to interview women working in factories to understand how they manage the expectations of their supervisors, make ends meet, and support their households on a day-to-day basis

4. France might be classified as which kind of nation?

- Semi-peripheral

5. In the past, Canada manufactured clothes. Many clothing corporations have shut down their Canadian factories and relocated to China. This is an example of ________________.

- Conflict theory

- Global inequality

- Capital flight

10.2. Global Wealth and Poverty 6. Slavery in the pre–Civil War American South most closely resembled ________________.

- Chattel slavery

- Debt bondage

- Relative poverty

7. Maya is a 12-year-old girl living in Thailand. She is homeless and often does not know where she will sleep or when she will eat. We might say that Maya lives in _________ poverty.

8. Mike, a college student, rents a studio apartment. He cannot afford a television and lives on cheap groceries like dried beans and ramen noodles. Since he does not have a regular job, he does not own a car. Mike is living in ___________________.

- Global poverty

- Absolute poverty

- Subjective poverty

9. Faith has a full-time job and two children. She has enough money for the basics and can pay her rent each month, but she feels that, with her education and experience, her income should be enough for her family to live much better than they do. Faith is experiencing _________________.

10. In a B.C. town, a mining company owns all the stores and most of the houses. It sells goods to the workers at inflated prices, offers house rentals for twice what a mortgage would be, and makes sure to always pay the workers less than they need to cover food and rent. Once the workers are in debt, they have no choice but to continue working for the company, since their skills will not transfer to a new position. This most closely resembles ______________.

- Child slavery

- Debt slavery

- Servile marriage

10.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification 11. One flaw in dependency theory is the unwillingness to recognize ____________________________________.

- That previously low-income nations such as China have successfully developed their economies and can no longer be classified as dependent on core nations

- That previously high-income nations such as China have been economically overpowered by low-income nations entering the global marketplace

- That countries such as China are growing more dependent on core nations

- That countries such as China do not necessarily want to be more like core nations

12. One flaw in modernization theory is the unwillingness to recognize____________________________________.

- That semi-peripheral nations are incapable of industrializing

- That peripheral nations prevent semi-peripheral nations from entering the global market

- Its inherent ethnocentric bias

- The importance of semi-peripheral nations industrializing

13. If a sociologist says that nations evolve toward more advanced technology and more complex industry as their citizens learn cultural values that celebrate hard work and success, she is using _________________ theory to study the global economy.

- Modernization theory

- Dependency theory

- Globalization theory

- Evolutionary dependency theory