- Appointments

- Resume Reviews

- Undergraduates

- PhDs & Postdocs

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Online Students

- Career Champions

- I’m Exploring

- Architecture & Design

- Education & Academia

- Engineering

- Fashion, Retail & Consumer Products

- Fellowships & Gap Year

- Fine Arts, Performing Arts, & Music

- Government, Law & Public Policy

- Healthcare & Public Health

- International Relations & NGOs

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations

- Media, Journalism & Entertainment

- Non-Profits

- Pre-Health, Pre-Law and Pre-Grad

- Real Estate, Accounting, & Insurance

- Social Work & Human Services

- Sports & Hospitality

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

- Sustainability, Energy & Conservation

- Technology, Data & Analytics

- DACA and Undocumented Students

- First Generation and Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Transfer Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Explore Careers & Industries

- Make Connections & Network

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Write a Resume/CV

- Write a Cover Letter

- Engage with Employers

- Research Salaries & Negotiate Offers

- Find Funding

- Develop Professional and Leadership Skills

- Apply to Graduate School

- Apply to Health Professions School

- Apply to Law School

- Self-Assessment

- Experiences

- Post-Graduate

- Jobs & Internships

- Career Fairs

- For Employers

- Meet the Team

- Peer Career Advisors

- Career Services Policies

- Walk-Ins & Pop-Ins

- Strategic Plan 2022-2025

Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important

- Share This: Share Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important on Facebook Share Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important on LinkedIn Share Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important on X

Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important was originally published on Ivy Exec .

Strong critical thinking skills are crucial for career success, regardless of educational background. It embodies the ability to engage in astute and effective decision-making, lending invaluable dimensions to professional growth.

At its essence, critical thinking is the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in a logical and reasoned manner. It’s not merely about accumulating knowledge but harnessing it effectively to make informed decisions and solve complex problems. In the dynamic landscape of modern careers, honing this skill is paramount.

The Impact of Critical Thinking on Your Career

☑ problem-solving mastery.

Visualize critical thinking as the Sherlock Holmes of your career journey. It facilitates swift problem resolution akin to a detective unraveling a mystery. By methodically analyzing situations and deconstructing complexities, critical thinkers emerge as adept problem solvers, rendering them invaluable assets in the workplace.

☑ Refined Decision-Making

Navigating dilemmas in your career path resembles traversing uncertain terrain. Critical thinking acts as a dependable GPS, steering you toward informed decisions. It involves weighing options, evaluating potential outcomes, and confidently choosing the most favorable path forward.

☑ Enhanced Teamwork Dynamics

Within collaborative settings, critical thinkers stand out as proactive contributors. They engage in scrutinizing ideas, proposing enhancements, and fostering meaningful contributions. Consequently, the team evolves into a dynamic hub of ideas, with the critical thinker recognized as the architect behind its success.

☑ Communication Prowess

Effective communication is the cornerstone of professional interactions. Critical thinking enriches communication skills, enabling the clear and logical articulation of ideas. Whether in emails, presentations, or casual conversations, individuals adept in critical thinking exude clarity, earning appreciation for their ability to convey thoughts seamlessly.

☑ Adaptability and Resilience

Perceptive individuals adept in critical thinking display resilience in the face of unforeseen challenges. Instead of succumbing to panic, they assess situations, recalibrate their approaches, and persist in moving forward despite adversity.

☑ Fostering Innovation

Innovation is the lifeblood of progressive organizations, and critical thinking serves as its catalyst. Proficient critical thinkers possess the ability to identify overlooked opportunities, propose inventive solutions, and streamline processes, thereby positioning their organizations at the forefront of innovation.

☑ Confidence Amplification

Critical thinkers exude confidence derived from honing their analytical skills. This self-assurance radiates during job interviews, presentations, and daily interactions, catching the attention of superiors and propelling career advancement.

So, how can one cultivate and harness this invaluable skill?

✅ developing curiosity and inquisitiveness:.

Embrace a curious mindset by questioning the status quo and exploring topics beyond your immediate scope. Cultivate an inquisitive approach to everyday situations. Encourage a habit of asking “why” and “how” to deepen understanding. Curiosity fuels the desire to seek information and alternative perspectives.

✅ Practice Reflection and Self-Awareness:

Engage in reflective thinking by assessing your thoughts, actions, and decisions. Regularly introspect to understand your biases, assumptions, and cognitive processes. Cultivate self-awareness to recognize personal prejudices or cognitive biases that might influence your thinking. This allows for a more objective analysis of situations.

✅ Strengthening Analytical Skills:

Practice breaking down complex problems into manageable components. Analyze each part systematically to understand the whole picture. Develop skills in data analysis, statistics, and logical reasoning. This includes understanding correlation versus causation, interpreting graphs, and evaluating statistical significance.

✅ Engaging in Active Listening and Observation:

Actively listen to diverse viewpoints without immediately forming judgments. Allow others to express their ideas fully before responding. Observe situations attentively, noticing details that others might overlook. This habit enhances your ability to analyze problems more comprehensively.

✅ Encouraging Intellectual Humility and Open-Mindedness:

Foster intellectual humility by acknowledging that you don’t know everything. Be open to learning from others, regardless of their position or expertise. Cultivate open-mindedness by actively seeking out perspectives different from your own. Engage in discussions with people holding diverse opinions to broaden your understanding.

✅ Practicing Problem-Solving and Decision-Making:

Engage in regular problem-solving exercises that challenge you to think creatively and analytically. This can include puzzles, riddles, or real-world scenarios. When making decisions, consciously evaluate available information, consider various alternatives, and anticipate potential outcomes before reaching a conclusion.

✅ Continuous Learning and Exposure to Varied Content:

Read extensively across diverse subjects and formats, exposing yourself to different viewpoints, cultures, and ways of thinking. Engage in courses, workshops, or seminars that stimulate critical thinking skills. Seek out opportunities for learning that challenge your existing beliefs.

✅ Engage in Constructive Disagreement and Debate:

Encourage healthy debates and discussions where differing opinions are respectfully debated.

This practice fosters the ability to defend your viewpoints logically while also being open to changing your perspective based on valid arguments. Embrace disagreement as an opportunity to learn rather than a conflict to win. Engaging in constructive debate sharpens your ability to evaluate and counter-arguments effectively.

✅ Utilize Problem-Based Learning and Real-World Applications:

Engage in problem-based learning activities that simulate real-world challenges. Work on projects or scenarios that require critical thinking skills to develop practical problem-solving approaches. Apply critical thinking in real-life situations whenever possible.

This could involve analyzing news articles, evaluating product reviews, or dissecting marketing strategies to understand their underlying rationale.

In conclusion, critical thinking is the linchpin of a successful career journey. It empowers individuals to navigate complexities, make informed decisions, and innovate in their respective domains. Embracing and honing this skill isn’t just an advantage; it’s a necessity in a world where adaptability and sound judgment reign supreme.

So, as you traverse your career path, remember that the ability to think critically is not just an asset but the differentiator that propels you toward excellence.

- University of Pennsylvania

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Penn Calendar

Search form

Courses for Fall 2024

| Title | Instructor | Location | Time | All taxonomy terms | Description | Section Description | Cross Listings | Fulfills | Registration Notes | Syllabus | Syllabus URL | Course Syllabus URL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSYC 0001-001 | Introduction to Experimental Psychology | Catherine Apgar Mengting Fang Ruda Lee Fiona Lee Nicole Mikanik Daniel C Swingley | FAGN AUD | TR 12:00 PM-1:29 PM | This course provides an introduction to the basic topics of psychology including our three major areas of distribution: the biological basis of behavior, the cognitive basis of behavior, and individual and group bases of behavior. Topics include, but are not limited to, neuropsychology, learning, cognition, development, disorder, personality, and social psychology. | Living World Sector (all classes) | ||||||||

| PSYC 0405-401 | Grit Lab: Fostering Passion and Perseverance in Ourselves and Others (SNF Paideia Program Course) | Maya Simone Brown-Hunt Angela L Duckworth Paolo Terni | SHDH 351 | T 3:30 PM-6:29 PM | At the heart of this course are cutting-edge scientific discoveries about passion and perseverance for long-term goals. As in any other undergraduate course, you will learn things you didn't know before. But unlike most courses, Grit Lab requires you to apply what you've learned in your daily life, to reflect, and then to teach what you've learned to younger students. The ultimate aim of Grit Lab is to empower you to achieve your personal, long-term goals--so that you can help other people achieve the goals that are meaningful to them. LEARN -> EXPERIMENT -> REFLECT -> TEACH. The first half of this course is about passion. During this eight-week period, you'll identify a project that piques your interest and resonates with your values. This can be a new project or, just as likely, a sport, hobby, musical instrument, or academic field you're already pursuing. The second half of this course is about perseverance. During this eight-week period, your aim is to develop resilience, a challenge-seeking orientation, and the habits of practice that improve skill in any domain. By the end of Grit Lab, you will understand and apply, both for your benefit and the benefit of younger students, key findings in the emerging science on grit. | OIDD2000401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 1210-401 | Introduction to Brain and Behavior | Judith Mclean | LEVN AUD | MW 12:00 PM-1:29 PM | Introduction to the structure and function of the vertebrate nervous system. We begin with the cellular basis of neuronal activities, then discuss the physiological bases of motor control, sensory systems, motivated behaviors, and higher mental processes. This course is intended for students interested in the neurobiology of behavior, ranging from animal behaviors to clinical disorders. | BIOL1110401, NRSC1110401 | Living World Sector (all classes) | |||||||

| PSYC 1210-402 | Introduction to Brain and Behavior | Fernanda M Holloman | LLAB 104 | T 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | Introduction to the structure and function of the vertebrate nervous system. We begin with the cellular basis of neuronal activities, then discuss the physiological bases of motor control, sensory systems, motivated behaviors, and higher mental processes. This course is intended for students interested in the neurobiology of behavior, ranging from animal behaviors to clinical disorders. | BIOL1110402, NRSC1110402 | Living World Sector (all classes) | |||||||

| PSYC 1230-401 | Cognitive Neuroscience | George Lin Allyson P Mackey Monami Nishio Victoria Morgan Subritzky Katz | ANNS 110 | MW 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | The study of the neural systems that underlie human perception, memory and language; and of the pathological syndromes that result from damage to these systems. | NRSC2249401 | Nat Sci & Math Sector (new curriculum only) | |||||||

| PSYC 1333-401 | Introduction to Cognitive Science | Russell Richie | DRLB A1 | TR 1:45 PM-3:14 PM | How do minds work? This course surveys a wide range of answers to this question from disciplines ranging from philosophy to neuroscience. The course devotes special attention to the use of simple computational and mathematical models. Topics include perception, learning, memory, decision making, emotion and consciousness. The course shows how the different views from the parent disciplines interact and identifies some common themes among the theories that have been proposed. The course pays particular attention to the distinctive role of computation in such theories and provides an introduction to some of the main directions of current research in the field. It is a requirement for the BA in Cognitive Science, the BAS in Computer and Cognitive Science, and the minor in Cognitive Science, and it is recommended for students taking the dual degree in Computer and Cognitive Science. | CIS1400401, COGS1001401, LING1005401, PHIL1840401 | General Requirement in Formal Reasoning & Analysis | |||||||

| PSYC 1340-401 | Perception | David H Brainard Alexander Gordienko Abigail B Laver | FAGN 116 | MW 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | How the individual acquires and is guided by knowledge about objects and events in their environment. | VLST2110401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 1440-001 | Social Psychology | Geoffrey Goodwin Frank Jackson Nicole Mikanik Shelby Weathers Ryan Wheat | STIT 261 | TR 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | An overview of theories and research across the range of social behavior from intra-individual to the group level including the effects of culture, social environment, and groups on social interaction. | Society sector (all classes) | ||||||||

| PSYC 1777-001 | Introduction to Developmental Psychology | Maya Mangalmurti Mcnealis Heather J Nuske Tiffany Tieu | MEYH B1 | TR 1:45 PM-3:14 PM | The goal of this course is to introduce both Psychology majors and non-majors majors to the field of Developmental Psychology. Developmental Psychology is a diverse field that studies the changes that occur with age and experience and how we can explain these changes. The field encompasses changes in physicalgrowth, perceptual systems, cognitive systems, social interactions and and much more. We will study the development of perception, cognition, language,academic achievement, emotion regulation, personality, moral reasoning,and attachment. We will review theories of development and ask how these theories explain experimental findings. While the focus is on human development, when relevant, research with animals will be used as a basis for comparison. | |||||||||

| PSYC 2220-401 | Evolution of Behavior: Animal Behavior | Yun Ding Marc F Schmidt | LEVN AUD | TR 1:45 PM-3:14 PM | The evolution of behavior in animals will be explored using basic genetic and evolutionary principles. Lectures will highlight behavioral principles using a wide range of animal species, both vertebrate and invertebrate. Examples of behavior include the complex economic decisions related to foraging, migratory birds using geomagnetic fields to find breeding grounds, and the decision individuals make to live in groups. Group living has led to the evolution of social behavior and much of the course will focus on group formation, cooperation among kin, mating systems, territoriality and communication. | BIOL2140401, NRSC2140401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 2288-001 | Neuroscience and Society | Sharon L Thompson-Schill | LEVN 111 | TR 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | Cognitive, social,and affective neuroscience have made tremendous progress in in the last two decades. As this progress continues, neuroscience is becoming increasingly relevant to all of the real-world endeavors that require understanding, predicting and changing human behavior. In this course we will examine the ways in which neuroscience is being applied in law, criminal justice, national defense, education, economics, business,and other sectors of society. For each application area we will briefly review those aspects of neuroscience that are most relevant, and then study the application in more detail. | Living World Sector (all classes) | ||||||||

| PSYC 2314-401 | Data Science for Studying Language and the Mind | Kathryn Schuler | COHN 402 | TR 12:00 PM-1:29 PM | Data Science for studying Language and the Mind is an entry-level course designed to teach basic principles of data science to students with little or no background in statistics or computer science. Students will learn to identify patterns in data using visualizations and descriptive statistics; make predictions from data using machine learning and optimization; and quantify the certainty of their predictions using statistical models. This course aims to help students build a foundation of critical thinking and computational skills that will allow them to work with data in all fields related to the study of the mind (e.g. linguistics, psychology, philosophy, cognitive science). | LING0700401 | Nat Sci & Math Sector (new curriculum only) | |||||||

| PSYC 2314-402 | Data Science for Studying Language and the Mind | Wesley Mark Lincoln | WILL 321 | R 1:45 PM-2:44 PM | Data Science for studying Language and the Mind is an entry-level course designed to teach basic principles of data science to students with little or no background in statistics or computer science. Students will learn to identify patterns in data using visualizations and descriptive statistics; make predictions from data using machine learning and optimization; and quantify the certainty of their predictions using statistical models. This course aims to help students build a foundation of critical thinking and computational skills that will allow them to work with data in all fields related to the study of the mind (e.g. linguistics, psychology, philosophy, cognitive science). | LING0700403 | Nat Sci & Math Sector (new curriculum only) | |||||||

| PSYC 2737-001 | Judgment and Decisions | Diego Fernandez-Duque Camilla Van Geen Feiyi Wang | LEVN AUD | M 5:15 PM-8:14 PM | Thinking, judgment, and personal and societal decision making, with emphasis on fallacies and biases. | |||||||||

| PSYC 2750-401 | Behavioral Economics and Psychology | Paul Deutchman | COLL 200 | TR 3:30 PM-4:59 PM | Our understanding of markets, governments, and societies rests on our understanding of choice behavior, and the psychological forces that govern it. This course will introduce you to the study of choice, and will examine in detail what we know about how people make choices, and how we can influence these choices. It will utilize insights from psychology and economics, and will apply these insights to domains including risky decision making, intertemporal decision making, and social decision making. | PPE3003401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 3220-401 | Neural Systems and Behavior | Marc F Schmidt | PSYL C41 | MW 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | This course will investigate neural processing at the systems level. Principles of how brains encode information will be explored in both sensory (e.g. visual, auditory, social, etc.) and motor systems. Neural encoding strategies will be discussed in relation to the specific behavioral needs of the animal. Examples will be drawn from a variety of different model systems. | BIOL4110401, BIOL5110401, NRSC4110401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 3281-401 | Computational Neuroscience Lab | Nicole C Rust | CANCELED | This course will focus on computational neuroscience from the combined perspective of data collection, data analysis, and computational modeling. These issues will be explored through lectures as well as Matlab-based tutorials and exercises. The course requires no prior knowledge of computer programming and a limited math background, but familiarity with some basic statistical concepts will be assumed. The course is an ideal preparation for students interested in participating in a more independent research experience in one of the labs on campus. | NRSC3334401 | |||||||||

| PSYC 3400-301 | Positive Psychology Seminar: Positive Education (SNF Paideia Program Course) | Caroline Jane Connolly | PWH 108 | M 1:45 PM-4:44 PM | This intensive, discussion-based seminar will equip you with useful insight and critical analysis about Positive Psychology by emphasizing scientific literacy. The workload for this seminar requires intensive reading. To excel in this seminar, students must be willing to enthusiastically read, dissect, and critique ideas within Positive Psychology. This requires students to articulate various ideas in verbal and written form. | |||||||||

| PSYC 3440-301 | Friendship and Attraction Seminar (SNF Paideia Program Course) | Caroline Jane Connolly | WILL 319 | TR 1:45 PM-3:14 PM | This seminar primarily focuses on heterosexual friendship between men and women, and the methodological issues of investigating such relationships. The scope for sexuality and romance in heterosexual opposite-sex friendship will be explored, as well as the possibility that men and women perceive opposite-sex friendship differently from each other. The ramifications of sex, romance, and incongruent perspectives in these relationships will be discussed, as will intimacy, competition, homosexual friendship, and same-sex friendship. | |||||||||

| PSYC 3464-301 | Seminar in Clinical Psychology: Theories of Psychotherapy | Elizabeth D Krause | GLAB 100 | R 12:00 PM-2:59 PM | This seminar provides an introduction to several major theoretical approaches to psychotherapy, such as psychodynamic/psychoanalytic, behavioral and cognitive-behavioral, humanistic, and interpersonal/group therapy models. Students will learn how these theoretical frameworks differentially influence assessment, case conceptualization, treatment planning, style of the therapeutic relationship, intervention techniques, and methods of evaluating therapy process and outcomes. Using case vignettes, film demonstrations, classroom role playing, and other experiential exercises, students will learn how these models are applied in real world settings and begin to develop an awareness of their own therapeutic philosophy. Critical analysis of the models will be advanced through ethical considerations and the application of multicultural and feminist perspectives. | |||||||||

| PSYC 3766-301 | Inside the Criminal Mind | Rebecca E Waller | GLAB 207 | WF 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | This seminar explores the development of antisocial behavior including psychopathy, aggression, and violence. At its core, this course examines what increases the risk that children will develop behavior problems and go onto more chronic and extreme forms of violence and psychopathic personality that results in harm to others. We will examine psychiatric diagnoses associated with these antisocial behaviors in both childhood and adulthood and how they link to other relevant forms of psychopathology (e.g., substance use, ADHD). We will explore research elucidating the neural correlates of these behaviors, potential genetic mechanisms underlying these behaviors, and the environments that increase risk for these behaviors. Thus, there will be a focus on neurobiology and genetics approaches to psychiatric outcomes, as well as a social science approach to understanding these harmful behaviors, all while considering development across time. We will also consider ethical and moral implications of this research. | |||||||||

| PSYC 3780-401 | Advanced Seminar in Psychology: Obedience | Edward Royzman | PSYL A30 | R 1:45 PM-4:44 PM | Though almost half a century old, Milgram’s 1961-1962 studies of “destructive obedience” continue to puzzle, fascinate, and alarm. The main reason for their continued grip on the field’s attention (other than the boldness of the idea and elegance of execution) may be simply that they leave us with a portrait of human character that is radically different from the one that we personally wish to endorse or that the wider culture teaches us to accept. In this seminar, we will take an in-depth look at these famous studies (along with the more recent replications) and explore their various psychological, political and philosophical ramifications. | PPE4802401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 3803-401 | Advanced Seminar in Psychology: Modeling Choice Behavior | Sudeep Bhatia | 36MK 108 | R 1:45 PM-4:44 PM | How do people decide and how can we study decision processes using formal mathematical and computational models? This course will address this question. It will examine popular quantitative modeling techniques in psychology, economics, cognitive science, and neuroscience, and will apply these techniques to study choice behavior. Students will learn how to test the predictions of choice models, fit the models on behavioral data, and quantitatively examine the goodness-of-fit. They will also get practice formulating their own models for describing human behavior. This class will have a major programming component, however no prior programming experience is required. | PPE4803401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 4281-402 | Computational Neuroscience Lab | Nicole C Rust | TOWN 303 | MW 12:00 PM-1:29 PM | This course will focus on computational neuroscience from the combined perspective of data collection, data analysis, and computational modeling. These issues will be explored through lectures as well as Matlab-based tutorials and exercises. The course requires no prior knowledge of computer programming and a limited math background, but familiarity with some basic statistical concepts will be assumed. The course is an ideal preparation for students interested in participating in a more independent research experience in one of the labs on campus. | NRSC3334402 | ||||||||

| PSYC 4460-301 | Everyday Psychology | Loretta Flanagan-Cato | GLAB 102 | WF 10:15 AM-11:44 AM | PSYC 4460 is an activity-based course with three major goals. First, the course is an opportunity for psychology and cognitive science undergrad majors to develop their professional and science communication skills and share their enthusiasm for these topics with high school students at a nearby public high school in West Philadelphia. In this regard, Penn students will prepare demonstrations and hands-on activities to engage local high school students, increase their knowledge in functions of the mind and brain, providing insights that may promote well being for the high school students and their community. This will be accomplished as students design and execute hands-on/minds-on activities on a range of psychology topics. There will be 10 sessions across the semester for these lessons, allowing the college and high school students to develop a consistent teacher-learner relationship. Second, students will explore the literature that discusses the need for better bridges between scientific research and the broader community. Discussions will incorporate the students' experiences, including challenges and rewards, as they bring psychology lessons to local youth. This academic portion of the course will include guest lectures from the Penn community who actively engaged in community partnerships. Third, students will be challenged to consider solutions for any problems that they encounter using a Theory of Change framework. This aspect of the course will result in a final project in which students much create logical, realistic, evidence-based links between interventions, indicators of change, and ultimate impacts to mitigate the problems. | |||||||||

| PSYC 4462-301 | Research Experience in Abnormal Psychology | Melissa G. Hunt | This is a two-semester course starting in the Fall. Class size limited to 8-10 students. | |||||||||||

| PSYC 4901-401 | Research Practicum in Cognitive Science | Russell Richie | OTHR IP | F 9:00 AM-11:44 AM | Research Practicum is a six-week half-credit course that facilitates students’ entry into research in cognitive science. Students complete a small project of their own devising, from hypothesis generation to report writing, and attend weekly guest lectures from graduate students and post-docs in cognitive science labs that are looking for undergraduate research assistants. Practicum has a ‘flipped’ classroom. Before class each week, students watch video lectures; in-person class is for asking questions about the week’s lecture, and to work on the week’s assignment for the student’s project, with help from the instructor and TA as needed. Each week, we will also have a guest lecturer from the lab of a MindCORE faculty affiliate. (The lecture and the project time could be joined into a single class session (~2.5-3 hours long) but it may be preferable to split these into two separate class sessions in the week.) The main product – pieces of which the student submits every week – is a 4-5 page paper reporting the study they conducted. Each week, students will also write a 150 word summary/reflection on the guest lecture that week. | COGS1770401, LING1770401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 4997-301 | Senior Honors Seminar in Psychology | Elizabeth M Brannon | EDUC 008 | M 1:45 PM-4:44 PM | Open to senior honors candidates in psychology. A two-semester sequence supporting the preparation of an honors thesis in psychology. Students will present their work in progress and develop skills in written and oral communication of scientific ideas. Prerequisite: Acceptance into the Honors Program in Psychology. | |||||||||

| PSYC 5470-001 | Foundations of Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience | Martha J. Farah | CANCELED | This course is designed to introduce students to the interdisciplinary field of social, cognitive and affective neuroscience. We begin with the basics of neurons, synapses and neurotransmission and the functional anatomy of the human brain. We then move on to neuroscience methods including cellular recordings, EEG/ERP, lesion methods, structural and functional neuroimaging and brain stimulation. The remainder of the course covers the neural systems involved in emotion, social cognition, executive function, learning and memory, perception and development. We focus on how our understanding of these systems has emerged from the use of the methods studied earlier. | ||||||||||

| PSYC 6000-301 | Psychopathology | Ayelet M Ruscio | GLAB 100 | W 12:00 PM-2:59 PM | Choice of half or full course units each sem. covering a range of subjects and approaches in academic psychology. | |||||||||

| PSYC 6000-302 | Social Neuroscience | Martha J. Farah | GLAB 100 | M 12:00 PM-1:59 PM | Choice of half or full course units each sem. covering a range of subjects and approaches in academic psychology. | |||||||||

| PSYC 6000-303 | Judgment & Decisions | Barbara Ann Mellers | GLAB 102 | TR 8:30 AM-10:29 AM | Choice of half or full course units each sem. covering a range of subjects and approaches in academic psychology. | |||||||||

| PSYC 6110-401 | Applied Regression and Analysis of Variance | Alexander Vekker | JMHH 270 | TR 12:00 PM-1:29 PM | An applied graduate level course in multiple regression and analysis of variance for students who have completed an undergraduate course in basic statistical methods. Emphasis is on practical methods of data analysis and their interpretation. Covers model building, general linear hypothesis, residual analysis, leverage and influence, one-way anova, two-way anova, factorial anova. Primarily for doctoral students in the managerial, behavioral, social and health sciences. Permission of instructor required to enroll. | BSTA5500401, STAT5000401 | ||||||||

| PSYC 8100-301 | Psychodiagnostic Testing | Melissa G. Hunt | NRN 00 | This course provides a basic introduction to the theories and tools of psychological assessment. Students learn how to administer and interpret a number of standard cognitive, neuropsychological and personality tests including the WAIS-III, WMS-III, WIAT-II, Wisconsin Card Sort, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and the Millon Index of Personality Styles. Attention is given to serving as a consultant, differential diagnosis, case conceptualization, and integrating test results into formal but accessible reports. | ||||||||||

| PSYC 8110-301 | Psychodiagnostic Interviewing | Melissa G. Hunt | NRN 00 | This course, usually taken simultaneously with Psychology 810, provides a basic introduction to psychodiagnostic interviewing and differential diagnosis. Students learn to take clinical histories and to administer a number of standardized diagnostic interviews, including the mental status exam, the SCID I and II for DSM-IV, the ADIS, and various clinician rating scales such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Attention is also given to self-report symptom inventories such as the Beck Depression Inventory and the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised as well as to computerized diagnostic tools. | ||||||||||

| PSYC 8150-301 | Introductory Practicum | Melissa G. Hunt | NRN 00 | Students typically complete 8-10 full assessment batteries on complex patients referred from a number of different sources in the community. This practicum offers intensive supervision, with live (in the room) supervision of every trainee’s first case, and live peer-supervision of their second case. Throughout their time in the practicum they receive close supervision of every case, including checking the scoring of tests and measures, and close reading and editing of every report. Students do a final feedback session with every patient which the supervisor co-leads at the beginning of the year, and observes in the room throughout the rest of the year, thus ensuring direct observation of every trainee throughout the year. |

Teaching Critical Thinking, Clinical Reasoning, and Teamwork Using Online Discussion Boards in Canvas

- February 22, 2022

- vol 68 issue 24

- Talk About Teaching & Learning

Carlo Siracusa

Just a few years ago, I was skeptical about online teaching. I was not convinced that students could learn effectively online. In particular, I thought that they could not learn how to effectively diagnose and communicate with clients (pets’ owners), and practice the critical thinking skills that are essential for clinical work. I also feared that I would lose the pleasure of working with students. However, both by developing courses that are purposely online and by leading courses that had to go online because of the pandemic, I’ve found that using online discussion boards prepares students effectively for the type of critical thinking they need and allows me to know them as well as or better than in in-person classes.

My attitude toward teaching online changed when, defeating my initial skepticism, I developed an online certificate program with a group of inspired colleagues. Within this program, I teach the online course Fundamentals of Animal Behavior (FoAB) that reviews principles of animal behavior and their application to animal welfare in a non-clinical setting. In this course, I first got the chance to experiment the use of online discussion boards to talk about controversial topics with the students.

The FoAB course is published in the learning management system Canvas, and is composed of weekly modules populated with videos on core theoretical concepts and recommended literature to review. Among the assignments, the students have to attend a synchronous review session via Zoom and participate in a weekly asynchronous discussion board on a controversial topic (e.g. the validity of behavioral testing in laboratory animals). The students have to follow the discussion throughout the week, post an original contribution using a maximum of 250 words, and comment at least once on the post of a classmate. The students’ statements must be meaningful, critical, and supported with references to published literature. The main teaching goal for the discussion boards of the FoAB course is practicing critical thinking and teamwork.

It is interesting to note that the students of the FoAB course complete all the activities remotely and never meet in person with each other or with the instructors. Therefore, I was surprised at first to see how much the students and the instructor behaved as a bonded community during both the synchronous sessions and the asynchronous discussions. The asynchronous discussion boards specifically are developed during the entire weekly module and do not suffer from the time constraints of an hourly synchronous session. They permit all members of the group to observe and review multiple exchanges and intervene when desired. At the end of the 7th week of my first online course, I knew the skills of the FoAB students better than those of my pre-clinical students in the “traditional” Veterinary Medicine doctoral degree, to whom I teach clinical animal behavior in person for a longer time.

Even after having accumulated this anecdotal evidence on the effectiveness of online learning, I did not want to give up the pleasure of interacting in-person with my pre-clinical veterinary students. However, the pleasure of in-person teaching did not last long because the coronavirus pandemic made its appearance. My experience with online learning could have come in handy at that point, but I still saw some obstacles in adapting what I had learned working online with a class of 20 FoAB students to a large class of 130 veterinary students. First, I needed to adapt the content of a live lecture of 50 minutes into video lectures of 10-15 minutes and readings for self-study. Second, I needed to determine if synchronous and asynchronous interactions were suitable for and beneficial to the large class. Third, I needed to decide how to assess the students’ learning and skills. For this purpose, I had traditionally used a final examination with multiple-choice questions on real-life clinical cases presented to the students via text and videos.

After a thorough analysis, I decided to apply what I learned teaching the online FoAB course to my nine-hour Clinical Animal Behavior course. I rearranged the content of the lectures and the examination across seven weekly modules. To replace the original lectures, I created two to three weekly short video lectures and selected reading materials. I replaced the final examination with seven asynchronous discussion boards of clinical cases, one for each module. Based on my previous favorable experience with the discussion boards and considering the large size of the class, I decided to not include synchronous sessions in this course.

The discussion boards were built to be the main learning tool in the course and to test knowledge, critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and teamwork. Clinical reasoning is the ability of the students to extrapolate and organize relevant information from the patient’s history and examination, and then use it to reach a diagnosis and to create a treatment plan. With these goals in mind, I presented the students with a clinical case for which I provided the history and a description of the clinical examination. I divided the class into four groups and asked all the students to contribute to the discussion of the case. Within their group, each student needed to write a post of up to 250 words and could add a second post on a voluntary basis, after all of their colleagues had posted at least once. Each participant had to follow up on the comments of the other students to build communally the analysis and treatment of the assigned case.

I have now used this format for two consecutive years of teaching the Clinical Animal Behavior course online. Hearing the students’ comments from the first year, I divided the class into smaller discussion groups of 10 students in the second year. Moreover, I had the chance to observe the students from the first year transitioning to clinical rotations with patient-side activities, during which they have to apply the skills learned in the behavior course. Based on preliminary observations, I saw that the students who participated in the clinical discussion boards performed better in their patient-side activities than students taught in a traditional way. This experience further grew my belief that online discussion boards are effective for refining critical thinking and teamwork skills. I also witnessed how the discussion of clinical cases through structured online discussion boards is ideal to practice clinical reasoning and prepare the students for patient-side clinical activities.

I believe that the same structured discussion boards could be implemented outside of an online environment with comparable benefits. For this reason, I plan to use structured discussion boards from now on, in whatever mode I teach. Online learning comes, in fact, with its own challenges. The main challenge that I experienced is the amount of time needed to develop and teach an online course. Among the most time-consuming activities are recording the video lectures, moderating the discussion boards, and reviewing all the assignments. All this may be particularly difficult for faculty members who, like me, have clinical duties assigned. Nevertheless, my skepticism about online learning has dissipated and I have become an advocate of structured discussion boards when teaching my students!

Carlo Siracusa is an associate professor of clinical behavior medicine at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

This essay continues the series that began in the fall of 1994 as the joint creation of the College of Arts and Sciences, the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Lindback Society for Distinguished Teaching.

See https://almanac.upenn.edu/talk-about-teaching-and-learning-archive for previous essays.

Social Media

Syo: critical thinking, event details.

Event Date: Monday, August 29, 2022

Event Time: 11:00 AM - to 12:00 PM

Event Description

This preceptorial teaches students the discipline of “critical thinking” – – advocated by Socrates, Francis Bacon, George Bernard Shaw (and many others) and enshrined at the entrance to the Royal Society in London. The focus will be on healthcare.

Add to Calendar Links

- Add to Google Calendar , opens in new tab

- Download .ics File

You are using an outdated browser. This website is best viewed in IE 9 and above. You may continue using the site in this browser. However, the site may not display properly and some features may not be supported. For a better experience using this site, we recommend upgrading your version of Internet Explorer or using another browser to view this website.

- Download the latest Internet Explorer - No thanks (close this window)

- Penn GSE Environmental Justice Statement

- Philadelphia Impact

- Global Initiatives

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Catalyst @ Penn GSE

- Penn GSE Leadership

- Program Finder

- Academic Divisions & Programs

- Professional Development & Continuing Education

- Teacher Programs & Certifications

- Undergraduates

- Dual and Joint Degrees

- Faculty Directory

- Research Centers, Projects & Initiatives

- Lectures & Colloquia

- Books & Publications

- Academic Journals

- Application Requirements & Deadlines

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Campus Visits & Events

- International Students

- Options for Undergraduates

- Non-Degree Studies

- Contact Admissions / Request Information

- Life at Penn GSE

- Penn GSE Career Paths

- Living in Philadelphia

- DE&I Resources for Students

- Student Organizations

- Career & Professional Development

- News Archive

- Events Calendar

- The Educator's Playbook

- Find an Expert

- Race, Equity & Inclusion

- Counseling & Psychology

- Education Innovation & Entrepreneurship

- Education Policy & Analysis

- Higher Education

- Language, Literacy & Culture

- Teaching & Learning

- Support Penn GSE

- Contact Development & Alumni Relations

- Find a Program

- Request Info

- Make a Gift

- Current Students

- Staff & Faculty

Search form

You are here, fostering critical thinking in the classroom.

At Penn GSE, Biros learned to teach using the inquiry method. A student-centered approach, it encourages students to play a leading role in learning. “The teacher is a facilitator, a coach, a curator of curriculum who helps students ask the right questions and find the right resources to answer them,” says Biros, who attended GSE with a Leonore Annenberg Teaching Fellowship, considered the equivalent of a national Rhodes Scholarship in teaching. An inquiry methods teacher also strives to make the classroom relevant to the lives and backgrounds of the students.

Biros has championed this technique in two Philadelphia public schools and is now making it the focus of his work launching charter schools in California. At University City, Biros mobilized his high school seniors to better understand problematic issues in their community. He asked them to generate questions and analyze data about low educational attainment, poverty, and crime, and arranged for then-Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter, W’79, to visit his class and respond to students’ questions about how citizens and government can effect change.

“We can begin to instill students with the notion that, ‘Yes, I can solve this.’ When people are empowered with that, what we can accomplish as a society will be endless.”

After graduating from Penn GSE, Biros worked for three years as a full-time teacher at the Kensington High School for Creative and Performing Arts, another public school in Philadelphia. There, he led efforts to redesign the school’s curriculum according to the inquiry method, working with colleagues including two former GSE classmates, Monty Ogden, GED’12, and Charlie McGeehan, GED’12. Their approach also emphasized technology, assigning every student a Chromebook laptop. “Students need the right tools so that they can be engaged learners and exhibit new understandings,” Biros says.

Since last summer, Biros has been developing charter schools in California with the support of the Silicon Schools Fund, a venture philanthropy foundation. To help launch a school in the established Alpha Public Schools network, which serves low-income communities, he has taken on responsibilities in management and operations in addition to teaching and curriculum development. In 2018, with support from Silicon, Biros plans to open his own school, the Collaborative Design Academy, slated to serve a diverse student population beginning with grades four and five and expanding through grade eight. Having worked in public and charter schools, Biros says he sees both as viable vehicles of educational progress. “What I care about is fostering unique and innovative school models,” he says. “I just want great schools, whether charter or public.”

Biros credits GSE with shaping his work through both the inquiry method and close-knit relationships with his classmates. “It was probably the most vibrant year of my academic life,” he says. “To be able to teach in a school and then attend class with my cohort at GSE and reflect on our work was really special. When teachers go into their classrooms and close the door, it is incredibly isolating. But when they are able to reflect and collaborate together, it is incredibly powerful. That’s where real growth comes from.”

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine .

You May Be Interested In

Related stories.

- Creating Opportunity Through Education: Penn GSE Alumni Lead the Way

Related Topics

Related news, media inquiries.

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.

Kat Stein Executive Director of Penn GSE Communications (215) 898-9642 [email protected]

Go to the Alumni section >

Alumni Resources

Get Involved

Our Community

Critical Writing seminars

Choosing the right seminar.

Every critical writing seminar follows the same rigorous curriculum and assessment process and standards. However, each of the three types described below is tailored to the specific needs of writers with differing backgrounds. Just as students who attended math- and science-intensive high schools may be better prepared for such courses at Penn, so too students who excelled at writing-intensive schools may be more advanced writers upon arrival. In turn, some students have had a bad experience with writing and, shying away from it, are not as practiced as their colleagues. Still others may have received substantial instruction in writing but have had limited exposure to specifically American English practices and conventions of writing demanded of Penn students.

During the first week of class, students take a writing diagnostic that helps the instructor determine whether they have enrolled in the course best suited to their needs. However, we find that students are often better able to make this determination themselves, given sufficient information. Proper self-placement saves students the inconvenience of switching classes and schedules during what is already a hectic time of year.

We encourage students to explore the descriptions below and choose the type of seminar that sounds most attuned to their level of preparation. Students who are properly placed typically do well in their seminars, while those who enroll in one not tailored to their needs may quickly fall behind and have to take a second writing seminar to fulfill the requirement.

Students who answer yes to two or more attributes of a given seminar type are encouraged to enroll in that category of seminar.

WRIT 0000 to 0999

These seminars are similar to the second-semester writing seminars taught at other universities. With the exception of "Global English" (WRIT 0110, more information below), the assumption in these seminars is that students are fluent speakers and writers of American English and are knowledgeable about its basic conventions (organizational structure, plagiarism, spelling, etc). These seminars are best suited to students who:

- are confident writers, who may make an occasional error but are generally in control of the fundamentals (grammar, usage, thesis, paragraph construction)

- are confident readers, capable of analyzing and writing about English texts independently

- have had considerable writing practice and guidance in high school (an average of 4 or more pages per week)

- anticipate needing some individual guidance from tutors or instructors, but not frequent meetings with either

For students who would benefit from a more individualized and targeted approach to college writing, we offer two other seminars.

WRIT 0020: Craft of Prose

This seminar fulfills the writing requirement, follows the same curriculum and has the same workload, assessment process and standards as all other writing seminars at Penn. However, seminar enrollment is capped at 12 and instruction includes a significant amount of individualized attention and guidance. While each session has a topic, the emphasis is on the study and practice of writing. Students in the Craft of Prose sections get considerable feedback and mentoring from tutors as well as their instructor. This, along with practice, can significantly accelerate students' writing skills. Only Freshmen and Sophomores are eligible to enroll in Craft of Prose.

The Craft of Prose seminars are best suited to students who might answer "yes" to two or more of the following:

- are intellectually gifted but struggle with one or more of the following: organization and timely submission of assignments; reading comprehension; information processing; writing- or reading-related anxiety; perfectionism or other issues that interfere with reading or writing

- did not get extensive practice and guidance on their writing in high school; for example, wrote fewer than four pages per week on average

- lack confidence in themselves as writers or feel that they need additional help with fundamentals

- do not like to read, are slow readers, or are anxious about reading and analyzing advanced texts

- anticipate needing a fair amount of individual guidance and feedback

- scored below 670 on the SAT Writing or Critical Reading tests

- tend to do considerably better with creative rather than academic writing assignments

WRIT 0110: Global English

This seminar fulfills the writing requirement, follows the same curriculum, and has the same workload, assessment process and standards as all other writing seminars at Penn. The Global English seminars focus on a scholarly topic within the field of global English -- for example, studies of films or literature written in English by non-native speakers; global human rights; digital culture; and other topics that are published in English but written by and for non-native as well as native speakers of the language. Along with this global focus, what distinguishes the Global English seminars is that they are intended for international students and sensitive to their needs, including instruction in the conventions and demands of American English college writing. International students especially enjoy these small seminars in their first year at Penn because they provide an international community that is also adjusting to life and college in the States.

Students who find the Global English seminars best suited to their needs include those who:

- may have attended American or English schools, but have not studied American English writing in the contiguous United States

- are not native speakers of American English

- are fluent in English but struggle with certain aspects of American English, such as articles or verb tenses

- would benefit from specific instruction in such issues as plagiarism, citation, and the organization and voice expected of American English college work

If after reading about these different options you are still uncertain about which seminar is right for you, please do not hesitate to consult with your adviser or with a member of the writing program administration.

If you would like additional feedback, you are welcome to take the diagnostic essay in advance of arriving at Penn, or during orientation week, to get some additional guidance. To arrange to take an advance diagnostic essay, write [email protected] .

Advance diagnostics are best taken at least three weeks prior to the first day of class to allow sufficient time for them to be read and scored. However, we are happy to look at them at a later date, as time permits!

Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally

Program overview.

Emphasizing the importance of long-term strategic decision making, Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally is designed to improve managers’ judgment and critical thinking skills using proven approaches, cutting-edge research, and behavioral economics.

Participants will understand the decision-making process from start to finish, with the ability to recognize cognitive biases that inhibit good decisions. This strategic decision-making program enhances participants' capacity to make well-thought-out individual, group, and organizational decisions.

Date, Location, & Fees

If you are unable to access the application form, please email Client Relations at [email protected] .

November 11 – 15, 2024 Philadelphia, PA $12,500

May 19 – 23, 2025 Philadelphia, PA $12,500

Drag for more

Program Experience

Who should attend, testimonials, highlights and key outcomes.

In Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally , you will learn how to:

- Make decisions in a dynamic of uncertainty

- Build adaptability into your decisions

- Provide the leadership to mitigate the effects of cognitive biases

- Understand the role of emotions and ethics in decision making

- Develop tools to improve individual and organizational decision making

Experience & Impact

In an uncertain business environment, a major challenge is being a decisive, strategic leader. Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally is designed to improve your judgment and guide you to think rigorously and critically.

Wharton faculty, led by Professor Maurice Schweitzer, apply their field-based research and the latest strategic insights to help you broaden your perspective on how to influence, persuade, and make informed, strategic decisions without bias. You will be exposed to new tools and actionable knowledge that will make an immediate impact on how you lead your organization.

Session topics include:

- Rule-Based Decision Making

- Combining Opinions

- Thinking Ethically

- Judgment and Decision Making: The Logic of Chance

- Trust and Cooperation

- Power of Negative Thinking

- Decision Hygiene

- The Role of Data in Decision Making

- Group Decision Making

Through highly interactive lectures, exercises, and case studies, both in the classroom and in smaller work groups, this deep dive into the art and science of decision making will enhance your effectiveness as a leader.

Convince Your Supervisor

Here’s a justification letter you can edit and send to your supervisor to help you make the case for attending this Wharton program.

Due to our application review period, applications submitted after 12:00 p.m. ET on Friday for programs beginning the following Monday may not be processed in time to grant admission. Applicants will be contacted by a member of our Client Relations Team to discuss options for future programs and dates.

Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally is designed for executives who are moving from tactical to strategic roles and for those involved in cross-functional decisions. It is of particular benefit to organizations and industries whose decision-making approaches are shifting as a result of high levels of uncertainty, including telecommunications, financial services, and health care.

Participants leave the program with an expanded peer network, plus specific tools and frameworks they can use to enhance how they approach decisions across their organization.

Fluency in English, written and spoken, is required for participation in Wharton Executive Education programs unless otherwise indicated.

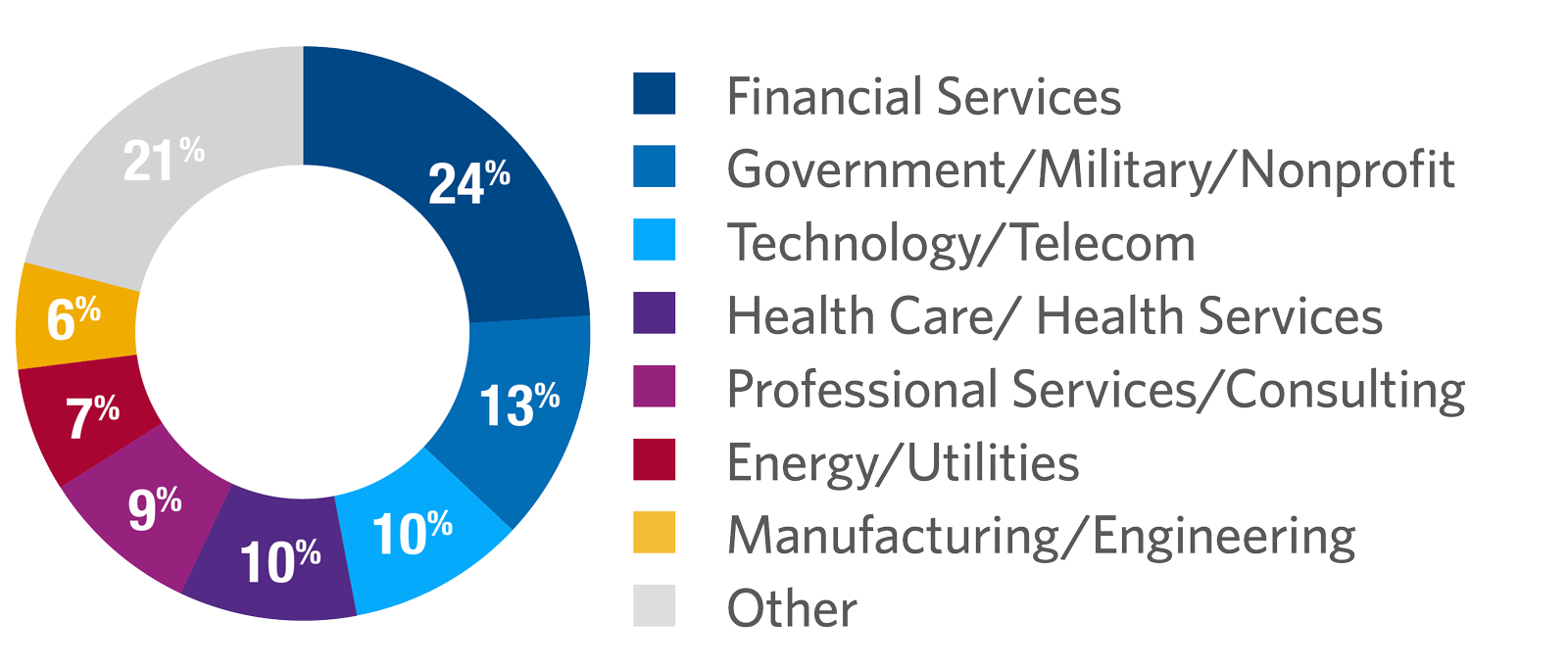

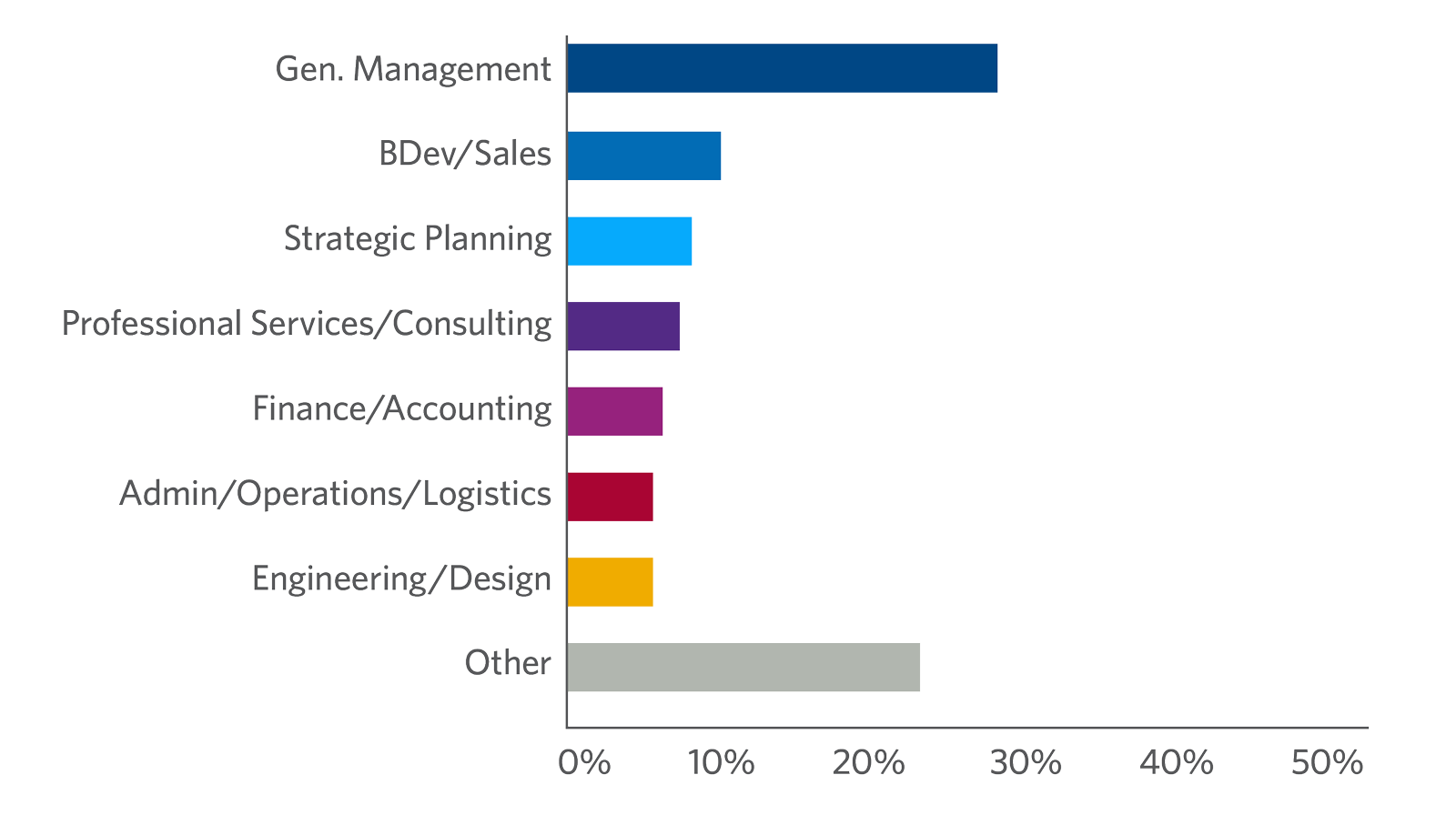

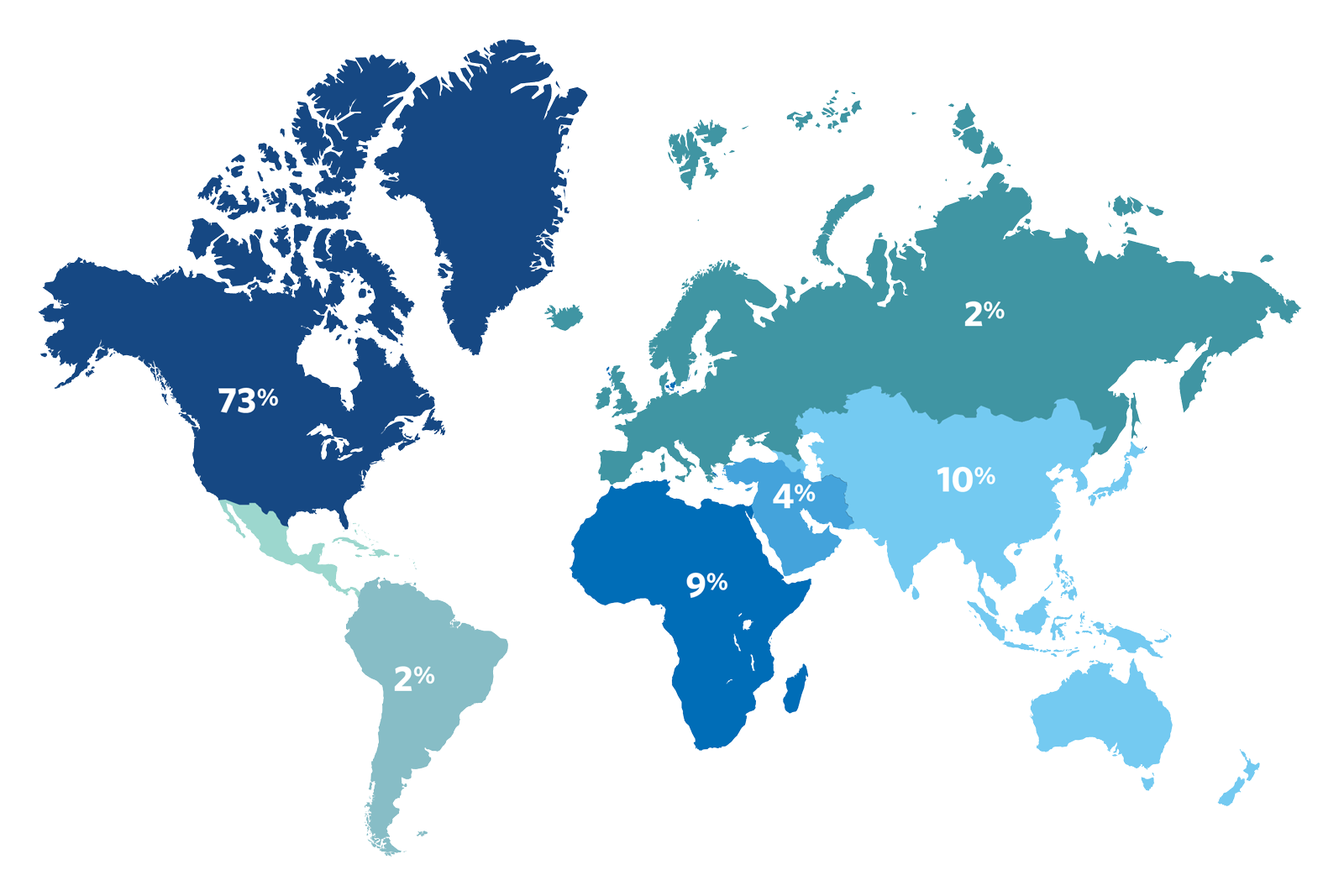

Participant Profile

Participants by Industry

Participants by Job Function

Participants by Region

Plan Your Stay

This program is held at the Steinberg Conference Center located on the University of Pennsylvania campus in Philadelphia. Meals and accommodations are included in the program fees. Learn more about planning your stay at Wharton’s Philadelphia campus .

Group Enrollment

To further leverage the value and impact of this program, we encourage companies to send cross-functional teams of executives to Wharton. We offer group-enrollment benefits to companies sending four or more participants.

Maurice Schweitzer, PhD See Faculty Bio

Academic Director

Cecilia Yen Koo Professor; Professor of Operations, Information and Decisions; Professor of Management, The Wharton School

Research Interests: Decision making, deception and trust, negotiations

Thomas Donaldson, PhD See Faculty Bio

Mark O. Winkelman Professor; Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics, The Wharton School

Research Interests: Business ethics, corporate compliance, corporate governance

Cade Massey, PhD See Faculty Bio

Practice Professor, Operations, Information and Decisions, The Wharton School

Research Interests: People analytics, judgment under uncertainty, organizational behavior

Joseph Simmons, PhD See Faculty Bio

Dorothy Silberberg Professor of Applied Statistics; Professor of Operations, Information and Decisions, The Wharton School

Research Interests: Judgment and decision making, experimental methods, consumer behavior

Abraham Wyner, PhD See Faculty Bio

Professor of Statistics; Director of Undergraduate Program in Statistics; Faculty Lead of the Wharton Sports Analytics and Business Initiative, The Wharton School

Research Interests: Baseball, boosting, data compression, entropy, information theory, probabilistic modeling, temperature reconstructions

Annie Duke, PhD See Faculty Bio

Speaker, Decision Strategist, and Former Professional Poker Player

Ernest D. Haynes III VP & General Manager, Sonoco

The timing for taking Wharton’s Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally was ideal because I am moving from a sales leadership role with Payer & Health System customers to an enterprise role where more strategic thinking will be needed. In my new position my remit will be to support and build the commercial capabilities of the entire enterprise. I have been customer facing for most of my career and now I will be working with more of an in-building team where pulling out the best ideas and thinking from my teammates will be critical. Wharton’s coursework and faculty’s way of thinking about decision making and how to be a better strategic thinker will absolutely help me in my new role. Two insights really struck me — one was strategies for how to get the best ideas, feedback, and insights from everyone on the team and how to fine-tune the ideas that surface, and the other was the thinking around randomness and how you have to be sure you are rewarding the process — not just the outcome — because oftentimes great or bad results can be driven by multiple factors, including bias. The pharma industry faces many challenges, especially in the areas of transparency and addressing the issue of the cost of drug products to the patient. How do you find the right balance between having a profit so you can innovate but being able to bridge for patients who need to be able to afford your innovation? Whoever cracks that nut and builds that bridge between innovation, affordability, and patient access will get the keys to the kingdom. Another issue we grapple with is around accessing physicians — as an industry we essentially have the same selling model as 50 years ago. In this digital age, we have to think about how we find the right balance of face-to-face engagement as well as building other ways to inform and educate physicians in real time. Wharton teaches you how to think about how best to approach problems like these — by using the tools that I learned in this course, I believe that in my new role, my team will net better results as we seek to solve complex issues like these facing our company and our industry. Also, now I have a broader network through Wharton that will be able to support me as I grow as a leader in my organization.”

Caroline DeMarco Vice President, Commercial Capabilities, Strategic Planning & Operations, GSK

What drew me to Wharton was its reputation and the deep selection of courses. A key takeaway for me in Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally was understanding the bias in qualitative information. I come from more of a quantitative background dealing with data, but as you advance through your career, the qualitative aspect of decision making becomes more important — the soft skills and our ability to use qualitative information to make effective decisions. When it comes to strategic decision making, there are no absolutes — you frequently have to make decisions without 100 percent of the information. This class really gives you pause to consider the implications of decisions, knowing that you don’t have 100 percent of the information. This has direct relevance to my role in risk management because we don’t deal with anything that is black and white. Wharton’s insights on qualitative decision-making bias also influenced what I wrote in an article on reputation risk that will appear in the RMA Journal .”

Joseph Iraci CRO of Regulated Entities & Managing Director of Financial Risk Management, TD Ameritrade

I am the director of the John Templeton Foundation’s character development portfolio. I oversee 60 grants that include research and programmatic grants focusing on advancing the science and practice of character. My greatest challenge is identifying the proposals that will yield important information about the cultivation of good character. In Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally we heard the latest research from experts in business, psychology, and law. These scholars are also very talented at translating that research and making it relevant to organizations independent of industry. They sparked a lot of my own thinking and ideas of ways in which we could use this research to improve the outcomes at our foundation. We like to think our decision-making processes are objective and free of bias, but bias is a part of human nature and as the workshop highlights, you will make far better, more strategic decisions if you understand what the biases are and how they influence your thinking. I came home with dozens of pages of notes for how my organization might use this latest research on strategic decision making to improve our own practices. Personally, I consider bias on a more regular basis and more intentionally, trying to build systems into my own process to mitigate the effects of these biases. Another lecture topic was on the logic of chance, which is very relevant to philanthropy. We spend a lot of time and resources trying to identify the best proposal to yield insights into character, but there is a lot of chance involved. We can’t guarantee results, but understanding the role chance plays in achieving an outcome is powerful. Wharton’s program was immediately applicable to my work. We are currently going through a strategic planning process and our foundation’s president asked the senior grant-making staff to brainstorm a number of ideas to pursue in the next round of our planning; during one of our off-site retreats, she used Wharton’s process for brainstorming. It was also great to have different perspectives in the program. We had participants from Nigeria, South Korea, and Brazil, and when the law professor shared a case study about Walmart and their practices abroad in the context of ethical decision making — specifically around the issue of bribery — it was fascinating to hear from individuals who do a lot of work abroad who could provide greater context. To conclude, this was an outstanding program, which would be valuable for any executive in any field. It’s about better thinking — becoming more cognizant of how to make better decisions.”

Sarah Clement Director of Character Virtue Development, John Templeton Foundation

I decided to attend the Effective Decision Making: Thinking Critically and Rationally program at Wharton to help me make even more effective decisions. As a result of my attending, I was able to broaden my strategic-thinking perspective based on insights from their highly impressive team of professors and colleagues who attended from a diverse range of functions, industries, and countries. There were several key takeaways that I have been able to leverage in my day-to-day work responsibilities, including the following: You cannot judge the quality of individual decisions based on their outcomes; instead, the quality should be judged on the process that was used to make them People tend to be overly precise while they should consider a much larger range of possibilities Even dramatically different outcomes can be purely the product of chance My overall experience exceeded my expectations. I plan on keeping in touch with a few of the colleagues whom I met and I certainly expect to find my way back to Wharton!”

Jonathan Hirschmann Animal Health Executive

Download the program schedule , including session details and format.

Hotel Information

Fees for on-campus programs include accommodations and meals. Prices are subject to change.

Read COVID-19 Safety Policy »

International Travel Information »

Plan Your Stay »

Related Programs

- Executive Negotiation Workshop: Negotiate with Confidence

Schedule a personalized consultation to discuss your professional goals:

+1.215.898.1776

Still considering your options? View programs within Leadership and Management , Strategy and Innovation or:

Find a new program

- Skip to Content

- Catalog Home

- Institution Home

- Courses A-Z /

Psychology (PSYC)

PSYC 0001 Introduction to Experimental Psychology

This course provides an introduction to the basic topics of psychology including our three major areas of distribution: the biological basis of behavior, the cognitive basis of behavior, and individual and group bases of behavior. Topics include, but are not limited to, neuropsychology, learning, cognition, development, disorder, personality, and social psychology.

Fall or Spring

1 Course Unit

PSYC 0400 The Pursuit of Happiness

What is happiness? Can it be successfully pursued? If so, what are the best ways of doing so? This interactive course will consider various ways of answering these questions by exploring theoretical, scientific, and practical perspectives on flourishing, thriving, and wellness. We will discuss approaches to happiness from the humanities and the sciences and then try them out to see how they might help us increase our own well-being and that of the communities in which we live.

PSYC 0405 Grit Lab: Fostering Passion and Perseverance in Ourselves and Others (SNF Paideia Program Course)

At the heart of this course are cutting-edge scientific discoveries about passion and perseverance for long-term goals. As in any other undergraduate course, you will learn things you didn't know before. But unlike most courses, Grit Lab requires you to apply what you've learned in your daily life, to reflect, and then to teach what you've learned to younger students. The ultimate aim of Grit Lab is to empower you to achieve your personal, long-term goals--so that you can help other people achieve the goals that are meaningful to them. LEARN -> EXPERIMENT -> REFLECT -> TEACH. The first half of this course is about passion. During this eight-week period, you'll identify a project that piques your interest and resonates with your values. This can be a new project or, just as likely, a sport, hobby, musical instrument, or academic field you're already pursuing. The second half of this course is about perseverance. During this eight-week period, your aim is to develop resilience, a challenge-seeking orientation, and the habits of practice that improve skill in any domain. By the end of Grit Lab, you will understand and apply, both for your benefit and the benefit of younger students, key findings in the emerging science on grit.

Also Offered As: OIDD 0050, OIDD 2000

PSYC 0986 Study abroad College elective

Non-major elective in the College study abroad

PSYC 0996 Transfer College elective

Non-major elective in the College transfer

PSYC 1210 Introduction to Brain and Behavior

Introduction to the structure and function of the vertebrate nervous system. We begin with the cellular basis of neuronal activities, then discuss the physiological bases of motor control, sensory systems, motivated behaviors, and higher mental processes. This course is intended for students interested in the neurobiology of behavior, ranging from animal behaviors to clinical disorders.

Also Offered As: BIOL 1110 , NRSC 1110

PSYC 1212 Physiology of Motivated Behavior

This course focuses on evaluating the experiments that have sought to establish links between brain structure (the activity of specific brain circuits) and behavioral function (the control of particular motivated and emotional behaviors). Students are exposed to concepts from regulatory physiology, systems neuroscience, pharmacology, and endocrinology and read textbook as well as original source materials. The course focuses on the following behaviors: feeding, sex, fear, anxiety, the appetite for salt, and food aversion. The course also considers the neurochemical control of responses with an eye towards evaluating the development of drug treatments for: obesity, anorexia/cachexia, vomiting, sexual dysfunction, anxiety disorders, and depression.

Also Offered As: NRSC 2227

Prerequisite: PSYC 0001

PSYC 1230 Cognitive Neuroscience

The study of the neural systems that underlie human perception, memory and language; and of the pathological syndromes that result from damage to these systems.

Also Offered As: NRSC 2249

Prerequisite: PSYC 0001 OR COGS 1001

PSYC 1310 Language and Thought

This course describes current theorizing on how the human mind achieves high-level cognitive processes such as using language, thinking, and reasoning. The course discusses issues such as whether the language ability is unique to humans, whether there is a critical period to the acquisition of a language, the nature of conceptual knowledge, how people perform deductive reasoning and induction, and how linguistic and conceptual knowledge interact.

Also Offered As: LING 0750

PSYC 1333 Introduction to Cognitive Science

How do minds work? This course surveys a wide range of answers to this question from disciplines ranging from philosophy to neuroscience. The course devotes special attention to the use of simple computational and mathematical models. Topics include perception, learning, memory, decision making, emotion and consciousness. The course shows how the different views from the parent disciplines interact and identifies some common themes among the theories that have been proposed. The course pays particular attention to the distinctive role of computation in such theories and provides an introduction to some of the main directions of current research in the field. It is a requirement for the BA in Cognitive Science, the BAS in Computer and Cognitive Science, and the minor in Cognitive Science, and it is recommended for students taking the dual degree in Computer and Cognitive Science.

Also Offered As: CIS 1400 , COGS 1001 , LING 1005 , PHIL 1840

PSYC 1340 Perception

How the individual acquires and is guided by knowledge about objects and events in their environment.

Also Offered As: VLST 2110

PSYC 1440 Social Psychology

An overview of theories and research across the range of social behavior from intra-individual to the group level including the effects of culture, social environment, and groups on social interaction.

PSYC 1450 Personality and Individual Differences

This course provides an introduction to the psychology of personality and individual differences. Many psychology courses focus on the mind or brain; in contrast to those approaches of studying people in general, the focus in this course is on the question "How are people different from each other?" It will highlight research that take a multidimensional approach to individual differences and attempts to integrate across the biological, cognitive-experimental, and social-cultural influences on personality.

PSYC 1462 Abnormal Psychology

The concepts of normality, abnormality, and psychopathology; symptom syndromes;theory and research in psychopathology and psychotherapy.

PSYC 1530 Memory

This course presents an integrative treatment of the cognitive and neural processes involved in learning and memory, primarily in humans. We will survey the major findings and theories on how the brain gives rise to different kinds of memory, considering evidence from behavioral experiments, neuroscientific experiments, and computational models.

Also Offered As: NRSC 1159

PSYC 1777 Introduction to Developmental Psychology

The goal of this course is to introduce both Psychology majors and non-majors majors to the field of Developmental Psychology. Developmental Psychology is a diverse field that studies the changes that occur with age and experience and how we can explain these changes. The field encompasses changes in physicalgrowth, perceptual systems, cognitive systems, social interactions and and much more. We will study the development of perception, cognition, language,academic achievement, emotion regulation, personality, moral reasoning,and attachment. We will review theories of development and ask how these theories explain experimental findings. While the focus is on human development, when relevant, research with animals will be used as a basis for comparison.

PSYC 2220 Evolution of Behavior: Animal Behavior

The evolution of behavior in animals will be explored using basic genetic and evolutionary principles. Lectures will highlight behavioral principles using a wide range of animal species, both vertebrate and invertebrate. Examples of behavior include the complex economic decisions related to foraging, migratory birds using geomagnetic fields to find breeding grounds, and the decision individuals make to live in groups. Group living has led to the evolution of social behavior and much of the course will focus on group formation, cooperation among kin, mating systems, territoriality and communication.

Also Offered As: BIOL 2140 , NRSC 2140

Prerequisite: BIOL 1102 OR BIOL 1121 OR PSYC 0001

PSYC 2240 Visual Neuroscience