Newly Launched - AI Presentation Maker

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 7 Company Credentials Examples with Templates and Samples

Monika Rajput

Every business should have its foundational company credentials. These are the details that no one must overlook because they help define your brand in the market and give an overall idea of your company's vision, achievements, and aspirations. These credentials also contribute to building trust among clients, investors, and partners. Such credentials include your market value, registration number, and headquarters country.

At SlideTeam, we understand how important it is to present these effectively, so we offer templates designed to highlight your company's journey and vision. Using these templates, you can ensure that your company credentials are not just stated but also presented in a way that attracts the target audience. They have a structure yet are versatile, which makes them ideal for emphasizing your journey and vision.

The good news is that our templates are 100% customizable and easy to edit. They come ready to use but can be tweaked to fit your audience perfectly.

Let’s check them out!

Template 1: Procurement Services Provider: Our Procurement Company's Credentials

This PPT template is made to exhibit what sets your procurement process apart from others. It also gives you a clear method for expressing your company vision, market value, presence, and registration number details, which are crucial in building trust. It will take you through sharing the story of your company, relevant procurement services, and why you are different from others. Get this template to talk to new clients, partners, or investors about the best things your company does and how much it would like to be the best in procurement processes. Moreover, it offers editable icons and simple instructions that allow changes as per your needs.

DOWNLOAD TEMPLATE

Template 2: Company Credentials Layout with Central Leaf Icon

A leafy central icon in this template has unique layout. Created as a one-step process, it is quick and easy to present those achievements and other credentials for your company. Being aligned with the values or visions of a company, the centre leaf icon integrates visually appealing elements that also represent growth, progress, and renewal. The versatility of this template lies in that it can be presented according to your needs by leveraging numerous editable icons suitable for different themes. Would you like to have a neat overview? Perfect choice! Get it now if you need an outstanding way to show off what makes your company stand out!

DOWNLOAD TEMPLATE

Make sure to concentrate on the elementary things and express the distinguishing factors of your company for an exceptional procurement company profile. Check this blog out for some examples and tips on how to show your company’s unique aspects better.

Template 3: Company Introduction Moviemaking Company Profile PPT Ideas

This presentation template offers a comprehensive overview of a film production company while emphasizing its commitment to core principles of integrity, innovation, and recognition. It explains the market segment, headquarters and founding year, and where its production houses are situated. We have designed these slides for extended discussions over important issues such as teamwork, innovation, recognition, and authenticity. This template is flexible enough to let you customize your presentation according to your audience's needs. Moreover, you can use this in narrating the story of your company and what principles lie at the heart of the filmmaking process. Download this presentation now and bring your company profile alive by capturing what makes your production house stand out amidst other players within the competitive film industry.

This blog has effective strategies for software companies looking to present innovation that can help you share your company vision and story.

Template 4: Company Profile For Construction Machinery Proposal Template

In order to make a compelling business proposal or company profile, you can highlight your strong points, including company vision, market value, and headquarters country as a construction machinery company in the PPT deck. This turns an international or local presence into a matter of fact. Simultaneously, this adds an element of trust by having the registration number in it. In delivering a concise and focused presentation, this template addresses five stages: Background, Company Vision, Our Focus, Company Mission, and Certifications and Memberships. It is ideal for construction machinery companies that are looking for contracts or expanding their service offerings to clients because it is fully customizable. A company stands out when its unique selling points professionally correspond to the customers. Get this deck for a standout and professional presentation!

Consider this blog for examples and templates on how to give a description of your company in terms of stories and facts.

Template 5: Company Overview Software Company Profile PPT Clipart

The slide is a must-have for software companies. It does a good job of summarizing crucial facts, e.g., name, incorporation year, headquarters country, and industry it operates in. The presentation goes further to provide details about the profile of the CEO, website address, company type, and ticker symbol, as well as financial aspects such as revenue streams, profitability ratios, and market value. More than that, your company's achievements can be seen from some awards or recognition pointing out its superiority. Designed to communicate detailed conversations on the Company Overview, this slide combines informative content with attractive creative design. Obtain a complete overhaul of your company by using this slide; it's fully editable to align with your company's specific branding and messaging needs.

Templae 6: Six Steps Company Credentials Diagram Using Hexagonal Shapes

This PPT deck is perfect for companies who want to present their credentials to the audience in an attractive manner. It has been custom-made with hexagonal shapes. The 6-Step Company Credentials Diagram showcases important company information like credentials, diplomas, and certificates. Moreover, hexagonal shapes also make it easier for businesses to highlight essential parts of their profiles in a coordinated manner, adding beauty to them. The presentation is ideal for your company when you need to communicate qualifications and achievements briefly. Choose this deck as the best solution for displaying your company's qualifications or calling cards in a way that everyone can easily comprehend.

Template 7: Company Credentials Info Graphic Using Rectangular Boxes Having Icons

This template features clarity and efficiency by which you can present your company credentials through rectangular boxes consisting of icons. It is an eight-step process that manages important information about a company, such as credentials, diplomas, and certificates. Each phase has its own icon, which makes it easy to understand what your organization stands for and its main achievements. This method of infographics not only makes complicated information simpler but also ensures that it is visually attractive to the audience so that they can pay attention to it. Download this template if you want to illustrate your company's capabilities and professional success in a clear yet impactful way. This template also helps ensure that the strong points and values are effectively communicated and properly understood.

Improve Your Efficiency

When it comes to making your company stand out, however, most of the attempts are centred on how you tell its narrative as well as the core elements (company vision, credentials, registration number, market value, and location). This is where a solid presentation can really help.

SlideTeam templates are designed just for you. Our templates will give you just what you need at this moment. They can easily be edited according to your style and language requirements, thus talking straight to the target audience. Whether it is about displaying the company vision, its market value, or where it is located, these templates are handy whenever you want to put everything across clearly and easily.

Related posts:

- Must-Have Product Brochure Templates for Advertising and Promotion

- Must-Have Brand Identity Proposal Templates With Examples and Samples!

- Top 10 Business Flyer Templates with Samples and Examples

- The What, Why & How Of Branding Explained

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 10 Introducing Yourself Templates with Examples and Samples

Top 10 Staff Augmentation Templates with Examples and Samples

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

--> Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

--> Sales funnel results presentation layouts

--> 3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

--> Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

--> Future plan powerpoint template slide

--> Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

--> Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

--> Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

--> Agenda powerpoint slide show

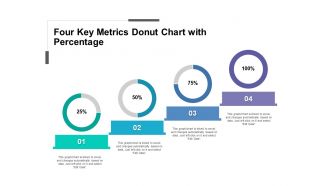

--> Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

--> Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

--> Meet our team representing in circular format

The Ultimate Guide: Advertising Agency Credentials Presentation Explained

- Post author By support

- Post date September 9, 2023

In today’s competitive business landscape, advertising agencies need to go beyond their creative ideas and stunning campaigns to truly stand out.

Enter the advertising agency credentials presentation, a powerful tool that showcases an agency’s expertise, accomplishments, and unique value proposition.

But what makes a credentials presentation truly effective?

How can agencies captivate their audience and leave a lasting impression?

Join us as we delve into the art of crafting a tailored presentation that not only highlights an agency’s credentials but also connects with the audience on a deeper level.

Get ready to unleash the secrets of a winning credentials presentation, guaranteed to leave your prospective clients begging for more!

advertising agency credentials presentation

The advertising agency credentials presentation is a crucial tool for showcasing the expertise and value of an agency to potential clients.

It aims to give a swift boost to the brand name and emphasizes the importance of tailoring the presentation to the audience’s specific needs and goals.

The advantage of flexibility offered by credentials decks is noted, and nine steps for building a persuasive presentation are provided.

Prioritizing the audience’s interests and motivations is recommended, with personalized touches on the first page and a navigation system that addresses their pain points or offers case studies.

Showcasing the behind-the-scenes process and turning the agency’s offerings into tangible business benefits are emphasized.

Testimonials and a concise, problem-solving approach are powerful in convincing potential clients, while leaving the ‘About Us’ section until the end is suggested.

The presenter’s authenticity, knowledge, tone, body language, confidence, and aura play a significant role in engaging the audience.

Optional extras for the presentation are also mentioned.

Key Points:

- Advertising agency credentials presentation is a crucial tool for showcasing expertise and value to potential clients

- Tailoring the presentation to the audience’s needs is important

- Flexibility of credentials decks is advantageous

- Prioritizing the audience’s interests and motivations is recommended

- Showcasing the behind-the-scenes process and turning offerings into tangible benefits are emphasized

- Testimonials and a problem-solving approach are powerful in convincing potential clients

Sources 1 – 2 – 3 – 4

💡 Did You Know?

1. The first recorded use of advertising can be traced back to ancient Egypt, where papyrus was used to create sales messages and posters to promote goods in marketplaces.

2. The phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” originated from an advertisement campaign by a New York advertising agency in the early 20th century. It popularized the idea of competing with neighbors to own the latest products and keeping a high social status.

3. The “Got Milk?” advertising campaign, which began in 1993, is considered one of the most successful and recognized campaigns in the history of advertising. It increased milk sales in the United States by over 7% within just one year.

4. The first-ever television commercial aired in the United States on July 1, 1941, during a broadcast of a Brooklyn Dodgers baseball game. It was an advertisement for Bulova watches and lasted only 10 seconds.

5. A famous advertising agency in London , Saatchi & Saatchi, created the iconic slogan “Just Do It” for Nike in 1988. The slogan was inspired by the last words of a murderer before he was executed, as the agency wanted to capture the essence of determination and action.

Rebranding Presentation For She World Advertising Agency

In the world of advertising, a rebranding presentation holds immense significance. It is a crucial opportunity for an advertising agency to showcase its abilities and make a lasting impression on potential clients . One such agency that recently underwent a rebranding presentation is She World Advertising Agency .

She World, a name that resonates with power and confidence, chose to emphasize these qualities in their rebranding. The presentation revolved around a bold and arrogant female character , perfectly capturing the essence of the agency’s identity. This character, featured prominently with a striking purple eyeline, symbolized the agency’s willingness to break stereotypes and push boundaries.

Here are some key points about the She World Advertising Agency rebranding presentation:

- A rebranding presentation is crucial in the world of advertising.

- It provides an opportunity to showcase an agency’s abilities and make a lasting impression on potential clients.

- She World Advertising Agency recently underwent a rebranding presentation.

- The presentation focused on a bold and arrogant female character.

- This character symbolized the agency’s willingness to break stereotypes and push boundaries.

“The presentation revolved around a bold and arrogant female character, perfectly capturing the essence of the agency’s identity.”

Emphasizing A Bold And Arrogant Female Character With Purple Eyeline

The choice of a bold and arrogant female character with a purple eyeline as the centerpiece of She World’s rebranding presentation was a strategic move . It aimed to leave a lasting impression on the audience and establish a unique identity for the agency. By embracing these qualities, She World showcased its fearlessness and determination to challenge traditional norms in the advertising industry.

The purple eyeline served as a visual representation of the agency’s creativity and innovation . It symbolized the agency’s ability to think outside the box and create unique and impactful campaigns. This striking visual element caught the attention of the audience and effectively conveyed the agency’s message of empowerment and confidence .

- The choice of a bold and arrogant female character

- The strategic move to leave a lasting impression

- Establishing a unique identity for the agency

- Embracing fearlessness and determination

- Visual representation of creativity and innovation

- Symbolism of thinking outside the box

- Creating unique and impactful campaigns

- Catching the attention of the audience

- Conveying a message of empowerment and confidence.

Swift Boost To Brand Name As The Aim Of The Presentation

The primary objective of She World’s rebranding presentation was to give a swift boost to the agency’s brand name . The agency recognized that in a competitive industry, establishing a strong brand presence is essential for success. Therefore, the presentation was meticulously curated to position She World as a reputable and influential player in the advertising realm.

The presentation showcased the agency’s portfolio of successful campaigns to enhance their credibility and demonstrate their expertise . By highlighting their past achievements , She World aimed to instill confidence in potential clients and showcase their ability to deliver exceptional results . This swift boost to the brand name would ultimately attract new clients and facilitate future business growth .

Importance Of A Tailored Advertising Agency Credentials Presentation

In the world of advertising, a one-size-fits-all approach rarely yields successful results. Therefore, the importance of creating a tailored advertising agency credentials presentation cannot be overstated.

Each potential client has unique needs, goals, and challenges, and tailoring the presentation to address these specific aspects is crucial for capturing their attention and interest .

A tailored presentation demonstrates that the agency has taken the time and effort to understand the client’s industry, market, and target audience. This level of personalized attention creates a sense of trust and confidence in the client, increasing the likelihood of a successful partnership.

By addressing the client’s specific needs and goals, the agency shows its commitment to delivering customized solutions that meet their unique requirements.

- A tailored advertising agency credentials presentation is essential for success .

- Understanding the client’s industry, market, and target audience is crucial in building trust .

- Customized solutions are the key to meeting the client’s unique requirements.

Focusing On Audience’s Specific Needs And Goals

When crafting an advertising agency credentials presentation , it is essential to focus on the audience’s specific needs and goals . By understanding the audience’s challenges and aspirations, the agency can tailor the presentation to address their pain points and offer relevant solutions.

The presentation should begin by capturing the audience’s attention and showcasing the agency’s expertise in their specific industry or market . This creates an immediate connection and establishes the agency as a credible and knowledgeable partner .

As the presentation progresses, it is imperative to align the agency’s offerings with the audience’s goals , demonstrating how the agency can help them achieve success.

• Focus on the audience’s specific needs and goals. • Tailor the presentation to address the audience’s pain points. • Showcase the agency’s expertise in the industry or market. • Establish the agency as a credible and knowledgeable partner. • Align the agency’s offerings with the audience’s goals.

Advantage Of Flexibility Offered By Credentials Decks

One of the advantages of using credentials decks in advertising agency presentations is the flexibility they offer. Credentials decks allow for easy customization and modification , enabling the agency to tailor the presentation to meet the specific requirements of each potential client.

By utilizing credentials decks, an agency can easily update and adapt the content , ensuring that it remains relevant and compelling . The flexibility of credentials decks also allows for easy integration of new case studies or success stories , further strengthening the agency’s credibility and showcasing its ability to deliver tangible results .

With credentials decks, agencies can create a dynamic and engaging presentation that resonates with each audience.

- Advantages of credentials decks in advertising agency presentations :

- Flexibility for customization and modification

- Easy update and adaptation of content

- Integration of new case studies or success stories

- Credentials decks help showcase the agency’s credibility and ability to deliver tangible results.

“Using credentials decks in advertising agency presentations offers flexibility, allowing for easy customization, modification, and adaptation of content. It enables agencies to tailor the presentation to meet the specific requirements of each potential client. With the ability to integrate new case studies or success stories, credentials decks effectively showcase the agency’s credibility and ability to deliver tangible results.”

Nine Steps For Building A Credentials Deck

Building an effective credentials deck requires careful planning and execution. Here are nine essential steps to create a compelling presentation:

- Research your target audience and understand their specific needs and goals .

- Define your agency’s unique selling proposition and core values.

- Structure the presentation in a logical and cohesive manner , with a clear narrative flow.

- Craft a captivating opening that grabs the audience’s attention and sets the tone for the presentation.

- Showcase your agency’s past successful campaigns and highlight the measurable impact they achieved.

- Translate the features of your agency’s offerings into tangible business benefits for the client.

- Incorporate visual elements , such as images, graphics, and videos, to enhance the visual appeal and storytelling of the presentation.

- Incorporate testimonials and endorsements from satisfied customers to build credibility and trust .

- Close the presentation with a strong call-to-action , prompting the audience to take the next step towards a partnership with the agency.

By following these steps, advertising agencies can build a compelling credentials deck that effectively showcases their expertise and convinces potential clients of their capabilities.

- Research target audience and understand their needs and goals.

- Define unique selling proposition and core values.

- Structure presentation with logical flow.

- Craft a captivating opening.

- Showcase successful campaigns and their impact.

- Translate features into tangible benefits.

- Incorporate visual elements.

- Include testimonials and endorsements.

- Close with a strong call-to-action.

Prioritizing Audience And Considering Their Interests And Motivations

When creating an advertising agency credentials presentation , it is crucial to prioritize the audience and consider their interests and motivations. Without a genuine understanding of the audience’s needs and desires, the presentation may fail to resonate with them effectively.

To effectively prioritize the audience, extensive research is necessary to gain insights into their industry, market, competitors, and target audience . By understanding the client’s industry landscape, the agency can tailor the presentation to address specific pain points and offer targeted solutions.

The presentation should focus on showcasing the agency’s ability to meet the client’s objectives and provide tangible value. By communicating the agency’s expertise and aligning it with the client’s goals, the presentation becomes a powerful tool to demonstrate how the agency can contribute to the client’s success .

- Prioritize the audience and consider their interests and motivations.

- Conduct extensive research to gain insights into the industry, market, competitors, and target audience.

- Tailor the presentation to address specific pain points and offer targeted solutions.

- Showcase the agency’s ability to meet the client’s objectives.

- Provide tangible value.

- Demonstrate how the agency can contribute to the client’s success.

“Without a genuine understanding of the audience’s needs and desires, the presentation may fail to resonate with them effectively.”

Advised Personalization On The First Page Of The Presentation

First impressions are critical in advertising agency credentials presentations. Therefore, it is highly recommended to personalize the first page of the presentation to capture the audience’s attention and demonstrate the agency’s commitment to their specific needs.

Personalization can take various forms, such as including the client’s logo or using targeted language that resonates with their industry or market. By tailoring the content of the first page to address the client’s pain points and aspirations, the agency creates an immediate connection and establishes credibility .

Additionally, the first page should showcase a compelling and concise statement of the agency’s unique value proposition . This statement should capture the essence of the agency’s expertise and provide a clear indication of why the potential client should choose to partner with them.

Creating A Navigation System That Addresses Client’s Pain Points Or Offers Case Studies

An effective advertising agency credentials presentation should have a clear and intuitive navigation system that addresses the client’s pain points or offers case studies . This allows the audience to easily navigate through the presentation and find relevant information that addresses their specific concerns.

The navigation system could include sections dedicated to addressing common pain points that clients in the industry face. Each section should present the agency’s unique solutions and demonstrate how they have successfully tackled similar challenges in the past.

Alternatively, the presentation could offer in-depth case studies that highlight the agency’s approach, strategy, and results. Case studies provide tangible evidence of the agency’s capabilities and allow potential clients to visualize how the agency can help them achieve their goals.

By creating a navigation system that focuses on the client’s pain points or showcases real-life success stories, the agency can effectively engage the audience and make a compelling argument for their services.

- A clear and intuitive navigation system

- Address client’s pain points or offer case studies

- Sections dedicated to common pain points and agency’s unique solutions

- In-depth case studies showcasing approach, strategy, and results

An effective advertising agency credentials presentation should have a clear and intuitive navigation system that addresses the client’s pain points or offers case studies. This allows the audience to easily navigate through the presentation and find relevant information that addresses their specific concerns.

What should be included in a credential presentation?

In a credential presentation, it is crucial to include the company’s vision, which should effectively communicate the purpose and drive behind fulfilling the company’s mission. By clearly articulating the vision, the audience will gain a deeper understanding of the company’s goals and aspirations, which can foster trust and engagement. Additionally, highlighting the company’s values is essential to showcase the principles and beliefs that guide the organization’s decision-making process. This not only helps the audience align with the company’s ethos but also demonstrates the company’s commitment to ethical practices and accountability. Overall, a comprehensive credential presentation should provide a clear and compelling vision along with the guiding values of the company to effectively engage and resonate with the audience.

What is a creds presentation?

A creds presentation is a strategic display of a company’s strengths and accomplishments. It serves as a condensed portfolio, presenting the best work of the company in a captivating manner. Its main objective is to highlight the products and services offered, emphasizing the value they bring and substantiating it with compelling evidence. This presentation acts as a powerful tool in establishing credibility and convincing potential clients or partners of the company’s expertise and capabilities.

What are the credentials of an agency?

An agency’s credentials serve as a comprehensive representation of its capabilities and expertise. They should showcase a track record of successful projects and satisfied clients, highlighting the agency’s effectiveness in addressing clients’ needs. These credentials should evoke confidence and trust, demonstrating the agency’s proficiency and competence to deliver desired outcomes. Ultimately, the credentials should articulate a compelling narrative that convinces clients that the agency is uniquely positioned to fulfill their requirements.

What is the presentation by ad agency to a client?

A presentation by an ad agency to a client is an opportunity for the agency to showcase their services and solutions. It is a carefully crafted sales presentation, often referred to as a pitch deck, designed to highlight the agency’s expertise and convince the client to choose their services. The pitch deck can be used to secure a meeting with potential investors or to demonstrate the agency’s capabilities in promoting a particular product. Ultimately, it serves as a persuasive tool to win the client’s trust and business.

Related Posts

- Digital Marketing Industry Size

- Cpm In Software Engineering

- Online Job Advertisement Tips and Tricks

- Online Advertising Courses In India

- Marketing Production Manager

- Aetna Health Insurance Customer Service Phone

- Advertising Networks Aoe2

- Marketing Financial Management

- Video Ads Crash Course 3.0 Review

- Wsi Digital Marketing Franchise Review

- Tags advertising , advertising agency , agency , client testimonials , creative portfolio , credentials , credentials presentation , explained , guide , marketing , marketing strategy , presentation , the , ultimate

Credential Presentation – Five tips for a powerful Company Introduction

Introducing a powerful idea.

A credential presentation gives business owners an opportunity to impress. The credentials PPT is usually the first step when engaging with an audience.

It is the perfect communication tool to start a customer-business relationship. The bigger objective is to sell a product or service. At times, business owners focus on the bigger picture instead of devoting time to improve the equally bigger task of putting out a credentials PPT.

Credential presentations are often neglected, incomplete, and outdated. In such a case, it is best to hire a professional credential presentation design agency . As the credentials PPT is the first line of consumer interaction, it needs to stand out in content, design, and structure.

Let’s look at five tips that can elevate your credentials presentation.

Communicate the vision

Firstly, hire a top presentation design agency . You won’t regret it. Their expertise in creating stunning yet engaging PPTs can help you get the desired credentials presentation.

When presenting a credential presentation, images are everything. The presentation is not designed to blindly shove a product or service to customers.

The goal of a credential presentation is to captivate the audience first and then sell along the way. The credentials presentation needs to communicate the company’s vision to the audience.

The vision must include the purpose and drive for fulfilling the company’s mission . The vision also covers company values. With the company vision set in the background, build the presentation through the company story. Storytelling can cause the company’s vision to resonate in the hearts of customers.

Adapting the slides

Each slide must be memorable. To ensure this, make sure you know the audience well. Identify and profile the credential presentation’s audience.

Refine the content in each slide. Compile, compose, edit, and proofread it before asking a PPT design expert to make it compelling.

The idea is to refine the presentation by removing clutter. This also reduces the size of the presentation. Doing some background research on the audience will help you determine who would be more receptive to visuals, numbers and content.

Focus on the future

Credential PPTs usually talk about a company’s origins. It starts with how the company was formed, its formative years in the industry, the key achievements, the biggest clients, etc.

Although, this is a good way to start a credential presentation , keep in mind this shouldn’t be all that you present. Dedicate only about 30% of your presentation to past and current activities.

Customers or investors want to know about the company’s future plans. Future partnerships, upcoming events, projected revenue, etc. have to be included.

Add visual elements

A credential presentation talks more about vision, goals, plans, and operations. With a deluge of information to be shared, it could become difficult to make the presentation immersive.

This can be fixed by letting a presentation design agency do what they do best. An experienced PPT design agency will come up with innovative ways to make your slide’s content captivating.

With the help of high-quality images, custom fonts, and appropriate animation, your company’s credential presentation will engage its audience with charm.

Call-out instruction

While presenting, make sure you are turning monologues into exchanges. Focus on human interactions.

Dedicate some time to answer questions. Once done, direct the audience to a clearly mentioned call-to-action . This CTA could be a link to the company website, a link to your company’s annual report or just a phone number to call.

Don’t leave the audience hanging. Be crystal clear as to what the purpose of the presentation is and what you expect the audience to do next.

- Scroll to top

9 tips to create a creds deck that connects with potential clients.

A creds deck has the power to back up your bold claims and show potential new clients that you’ve got what it takes to turn their dreams into reality. In just a few short slides, you can prove that your business has been there, done that, and knows exactly how to tackle any challenge that may come your way. So, why do most creds decks suck?

You’ve spent years crafting your skills and sharpening your ideas but now you’re tasked with an entirely different challenge: selling them. You’re not short of leads. The prospects are there and they’re yearning for a solution to their problems. But they’re anxious about making the right decision. There’s so much to consider and vast amounts of information available. And they’ve probably got a lot of options.

So, how do you get them to listen to you? How do you convince them that you are the right partner to take them forward? Cue the creds deck. Creds decks are so much more than a list of previous successes. Done right, they establish credibility and expertise, inspire trust, differentiate you from competitors, and paint an honest picture of your business.

Unfortunately, most creds decks aren’t done right. We’re going to show you how to create a compelling creds deck that truly connects with your audience, shifts their beliefs and makes them wonder why it took them this long to find you.

What is a creds deck?

A creds deck is essentially your company portfolio. It’s a collection of your very best work, presented in the most flattering way. Typically, the messaging of a creds deck focuses on two main areas. Firstly, it needs to showcase your products and services, the difference you make, and the evidence to back it up. These are your demonstrable successes – case studies, results, the impact, previous projects, etc. Second, and just as important, every component, from the visuals to the story, should accurately capture who you are as a business: your personality, your values and your mission. The audience should get a feel for your business identity through every slide. How you present this information depends on who you are and who your audience is, but creds decks need to do both if they’re to successfully persuade someone to invest.

Here comes the tricky bit. While the purpose of a creds deck is to show off your skills, the worst thing you can do is use this opportunity as an excuse to indulge in your success. There’s nothing wrong with being proud of your work, but there’s pride and then there’s outright bragging. No one wants to work with a narcissist. The focus needs to shift from you to your audience. Naturally, you’ll still talk about yourself, but in a client-centric way. So, the emphasis switches from reeling off your successes to how your successes make you qualified to help the person you’re talking to. Fail to make this switch and you risk total audience disconnect.

Westminster House

The problem with most cred decks.

Speaking of narcissism, most companies try to cram everything into their creds deck, so instead of being a greatest hits album, they become a playlist of everything you’ve ever made. The songs don’t follow on from each other. There’s no harmony. No continuity. No order. This won’t resonate with the listener. They want to hear about how you can address their specific needs and help them attain their personal goals. Clients are smart. If they get a whiff of irrelevance, they’ll lose interest. And if you use generic, nonspecific messaging, they’ll see right through it. Plus, I’m sure you’ll agree that your future clients are worth the effort of a tailored experience.

The home advantage

Creds decks also have the advantage of flexibility: they can be delivered remotely, from the convenience of your home. If for any reason, you can’t present in a face-to-face setting, there’s no reason why you can’t replicate the experience via a video call. You never know when a worldwide contagion’s going to sweep the nation, right? Creds decks give you that flexibility to sell your services in the online and offline spheres, without compromising on impact.

Building a creds deck in 9 steps

1. audience first.

The best way to approach your creds deck is to treat it like any other presentation. And what comes first in any other presentation? The audience. Like we said, too many companies focus on themselves. Before you start detailing how many offices you have and how many employees you’ve got, think about whether your audience even cares.

Companies with a focus on scaling up, for example, will likely see the benefit in your global locations. Others won’t give a toss about how many offices you have, but they may be enticed by the philanthropic string to your bow, seeing an opportunity to boost their CSR credentials. And this is exactly the point, the creds deck needs to be tailored to different audiences.

Think about who you’re pitching to through the lens of “What do they care about?”. Pinpoint their needs, motivations, challenges and expectations, and then use this information to draw parallels between their current reality and your solutions.

2. Personalise that page

Once you’ve thought about your audience, you can begin to piece the creds deck together. Starting unconventionally with… page one. This initial page needs to propose an idea so tempting they can’t click x.

In order to be compelling, your proposal has to resonate with them from the very first page. There’s no shortcut here, the only way to do this is to do your research. Get to know who you’re talking to so you can describe a situation they will identify with. Address a familiar scenario, reference some of their key challenges and set yourself up as the organisation with the keys to unlock their success. Personalise it to fit their situation, while introducing your own overarching value proposition.

Empathy is the driving force of a creds deck. The first page should prove to them that you get it. You understand where they want to go, you understand what’s holding them back and you know how to take them there. It should give them an inviting snapshot of what’s to come and a reason to keep listening.

3. Let the audience dictate their experience

Nothing creates an audience-centric presentation quite like a self-directed experience. Instead of building a linear deck, where audiences have no choice but to sit through every slide politely, give them the option to choose what they want to look at.

If you’d like to keep it simple, opt for a two-route menu system that enables them to jump to a particular slide, and back to the main menu. If you want to create a more dynamic experience, design a navigation system around their challenges. Create a menu that lists a set of pain points, with each one linking to your solution. This way, you can show that you already understand their challenges, and you’ve solved similar challenges before.

If case studies, rather than challenges, are the driving force of your messaging, you could even add layers of navigation for different verticals, or the brands that are most aligned to what they do. Ask them if there’s a company they aspire to be like and show them something similar you’ve worked on, or the real deal if you’ve got that connection under your belt. Navigation in presentation software can be as flexible as you want it to be, just remember to give your audience the power to choose where the conversation goes.

4. Show off what goes on behind the scenes

Your audience aren’t just interested in the final product, they’re keen to know how you got there. Odds are, you’re not the only company offering a solution to their problems, but what will distinguish you is the story you have to tell and the people behind your success.

The human element doesn’t come across in finished products, but in the struggle, the creativity and the development from the original ideas. Be transparent about the process – the highs, the lows, the time pressure, the deadlines, those late nights you spent trying to fix a software malfunction. Show them the mood boards and initial drafts that came before the polished piece. Explain how you overcame what seemed like an insurmountable challenge. In being transparent about the reality of the journey, flaws and all, you’ll evidence just how much passion goes in, from inception to final delivery.

Being honest about the challenges you faced gives you authenticity and shows grit. This will inspire confidence that no matter what, you’ll find an answer and get the job done.

5. Turn features into benefits

Features mean nothing without material business benefits. You should be applauded for devising a solution to their problems, but even if you’ve come up with a revolutionary idea with seven patents and first-of-their-kind features, so what? Features can be read on a specification list. Benefits need to be demonstrated.

Perhaps you’re saving them time, making their processes more efficient, cutting costs or reducing the possibility of downtime. Whatever it is that will change their lives, transpose it into a language that your audience understands, and don’t presume they’ll immediately grasp what these benefits mean for them. Explain the benefits in the context of their working environment, or better yet, show them an angle they may not have considered before. Don’t just say it will solve their challenges, demonstrate how it will and why you can do it better than anybody else.

People buy based on their emotions, but justify their purchases with logic. The features give them the logic, but the benefits stir an emotional response, and it’s this that will feed that motivation to purchase.

6. Let your clients do the selling for you

The purpose of a creds deck is to sell. We know it, you know it, and your potential clients know it. But that doesn’t mean they deserve to sit through soulless marketing spiel and slide after slide of humble brag. And don’t assume they’ll simply take your word for it.

The vast majority of people won’t part with their hard-earned money without some evidence of the tangible successes you’ve had with other companies. And for those who are on the fence, the right testimonial could be the push that lands you a new client. The herd effect is a powerful force. People feel safer making riskier business decisions if others have done it before them. Demonstrating a proven track record of success, with quotes from other people, will reassure prospects of your authenticity and credibility.

The best creds decks give enough evidence to satiate everyone’s appetite. Some are swayed by the human impact; others may be numbers people. A glowing review from a happy customer, placed next to some high-impact data visualisation, could be all it takes to cement your success.

Software presentation

“This might sound cheesy but do believe the Hype! We contacted them with a really urgent requirement and they delivered an amazing presentation and ultra fast. Knowing what we wanted and having the copy already drafted obviously helped but their team got our vision and brought it to life, and better than we expected. We will definitely work with them again and are already thinking about the next idea.”

Colin Brimson

CEO, d-flo Limited

Conference presentation

“Our conference presentation stood out as the best part, and presentation, of the day! The Rockstar section was the talk of the conference, with everyone asking our contact where they’d gone to produce that. Making noise at these events is how the individual brands cut through to the group heads and get more support and confidence where they need it.”

Gordon Donald

Senior Sponsorship and Promotions Manager, AG Barr

Sales presentation

“I highly recommend the team to anyone looking to elevate their communications and take their sales presentations to the next level.”

Stephanie Malham

Chief Operating Officer, Outright Games

CPD presentation

“The team guided us through the step-by-step process with ease, providing great insight and fresh new ideas, to create a more modern and engaging CPD for our audience.”

Andrew Hamilton

UK Specification and Marketing Director, FAAC

Investor deck

“The team helped us to create a first-class investor deck, which was instrumental to the success of our investment round. We ended up securing £585,000, which exceeded our expectations by 30%.”

Kirstine Newton

Co-founder, Altitude Gin

7. Keep it short

It’s good to be passionate about what you do, but try not to let that passion cloud your judgement about audience engagement. You may want to showcase every asset from your highly-successful marketing campaign or every page of a brochure you created, but your prospect probably has other things to be doing. You need to learn to edit. Only show the aspects of your offering that solve a problem for your audience.

Some slides will deserve more attention than others, but that’s your call. Dedicate more time to the topics that matter most for the audience, and to explain the most meaningful components of your overarching argument. Follow a pace that you’re comfortable with, but keep it snappy and stick to the point.

8. Leave the ‘About Us’ section until the end

Out of the hundreds of presentations we’ve seen, one of the most common slipups is talking about yourselves upfront. Imagine you’re a potential client with a niggling pain point. You accept a meeting invitation with a company claiming to have an answer to your problems. The meeting commences and the first thing they do is tell you about their history, awards and company culture, and this ends up eating into most of the meeting time.

Establishing your credibility is vital, but the quality of your ideas and previous successes will do this for you. Leave the ‘ About Us ’ section to the very end and make it optional in your navigation system. Most prospects should be sold on you before you reach this part.

9. You are the driving force of the creds deck

Don’t forget that your slides are there to support you. Think of them as tools that’ll help you get your message across. You, as the presenter, are always the focal point of the presentation.

Ultimately, you’ll convince prospects with your authenticity, knowledge, tone, body language, confidence, and aura. All of this is really important because, together, they’ll shape your prospect’s judgement of you.

Even through a video call, your passion should shine through. This is why practicing is so important. You can use the slides as visual aids or reference points, but when it comes to the moment of delivery, it’s you who’ll be centre stage, with your slides playing a supporting role.

Optional, but recommended, extras

It’s easy for busy companies to dismiss an opportunity to have a face-to-face conversation with you by asking you to send creds deck instead. This is convenient for them, but not so opportune for you, because you run the risk of the deck being lost in a busy inbox. Always try to push for a meeting. Your creds deck alone won’t be enough to persuade your audience. Without an in-person delivery, much of the passion that manifests through tone, gestures and unscripted answers to questions, will be lost.

If there’s no in-person meeting on the horizon, you can still use this to your advantage. Find out as much as you can about them via email, Linkedin or whatever their preferred communication platform is. Ask questions about what they’re currently working on, what’s filling up their time and what would relieve their pressure. Doing this is another way of evidencing that you genuinely care about helping them, and equips you with valuable information that you can use to personalise your creds deck, in preparation for the face-to-face meeting. Building this relationship online could be what charms them into setting up a video call, or making the time to give you that meeting in person.

At times, creating a creds deck may not feel like one of the most enjoyable aspects of self-promotion. Some people worry that a presentation won’t capture the brilliance of what they do, but with our tips, you can make sure every slide does your work justice. Or better yet, give the responsibility to someone else. As a full-service presentation agency , we’re fully equipped to take care of your creds deck for you. There’s no time like the present. Get your creds deck ready now, that next big prospect might be looking for your company as we speak.

Recent Posts

- Posted by hypepresentations

How we structure presentation content.

Your content is the foundation of your presentation, and how you create...

How many slides should I have in my PowerPoint presentation?

When you’re planning out your next big presentation, it can be hard...

Home » Pitching Support » Top ways to make agencies more effective in presenting their credentials

Top ways to make agencies more effective in presenting their credentials

For the past 20 years, I have literally sat through more than a thousand agency credentials presentations . Some were part of a pitch or tender credentials presentation, and others were when I was engaged in providing feedback to help agencies improve their credentials deck and presentation. I can honestly say that initially, less than ten agency credentials examples stood out as memorable.

I remember when this first became apparent after we had spent a day of chemistry meetings with eight back-to-back credentials presentations, where the agencies were asked to provide a maximum 30-minute presentation on “why choose this agency”. In the end, the clients only remembered one of the agencies by name, and the rest were referred to by some other mnemonic, such as the one with the guy with the red spectacles, etc.

So, what is wrong with how many agencies present their credentials? Let me share some common mistakes and solutions to help you hopefully make your credentials presentations more effective.

1. Focus on the purpose of the credentials presentation

Yes, this is like taking a brief about who it is, what they think and feel now, and what we want them to think and feel after seeing the presentation. Usually, it is a new business prospect, and what you want them to think and feel is your agency must either be on their shortlist or appointed at the end of the presentation.

I am not kidding here. In one agency credentials example, the presentation was so powerful that the client was talking about appointing the agency immediately but took them through the process and appointed them in the end. Still, I am sure they had won it at that first meeting.

2. Forget the template and the formula

So many agency credentials appear like a checklist of information. Who we are, what we do, where we are located, how we work, etc, etc, etc. It is predictable and boring and not required. Whoever said there was a checklist, a formula or a format for a credentials presentation?

Remember, I am discussing a presentation here, not a credentials document. Certainly, you need to include the details about you and your company in the document, but the presentation is not simply reading from the document.

3. Make sure you turn features into benefits

This is straight out of Alistair Crompton’s The Craft of Copywriting but applies just as much to agency credentials as to great advertising.

By way of example, I had an agency banging on about their Agency University and how they were committed to the professional development of their employees. It went for about four slides and got into the details of the curriculum and everything – clearly, they were enamoured with it.

The client is sitting there saying that’s all very nice, but “What’s in it for me?” I will tell you, the employees at this agency are training in the latest on business and marketing to advise you on a day-to-day basis better. If the client wants to know more, it is all in the credentials document.

4. Don’t tell them what you do

Tell them what you deliver.

This is an extension of the previous point and one often overlooked. Too often, I find the agency spends too much of the credentials presentation talking about what they do. Have you ever been to a doctor for the first time and had them spend any time telling you what they do? Or an accountant? Or a lawyer? Let’s be honest: most marketers and advertisers broadly know what a media agency does, a creative agency, a public relations firm, or a digital agency. So, telling them what do is potentially the fastest way to commodities yourself because everyone in your category will be saying largely the same thing. Of course, if the audience has no experience or understanding of marketing, you may need to explain what an agency does. But do not waste more than a minute or two on this.

5. If it is too dull or detailed, put it in the ‘leave-behind.’

I am not sure why agencies think they need to answer all of the client’s questions in the presentation. Often, the client may send through a list of questions they want the agency to address in the credentials presentation. Or the agency may invite and elicit questions that the clients are interested in. This is a good strategy. Having been asked, the agency should address these queries, just not necessarily in the presentation.

My favourite is when a client (usually procurement) asks the agency to detail their process. I defy anyone to find a way to present the process in a way that is not sleep-inducing. Remember, the purpose is to build rapport and hopefully get one step closer to getting the business. If something is particularly complex, boring, or potentially confusing, put it in the document the client will take away with them. (Yes, there should always be a document or written follow-up to reference the meeting.) Then, you can reference the details in the leave-behind and move on to more business-winning discussions.

6. Don’t just say it, show it

There is usually a point in the credentials presentation where we get to either the client testimonials, you know, the bit “That’s enough about us, let’s hear what our clients think about us,” or the case studies, which is a chance to show off the work and tell the client prospect how successful you have been.

Unfortunately, these are usually towards the end of the presentation after you have spent the first half talking about how successful you are as an agency and how unique you are. Instead of having a testimonial and case study section, using case studies and testimonials to demonstrate what you are saying is always more powerful.

For example, instead of saying you work collaboratively with other agencies (sure you do), why not have other agencies and your clients talk about your collaboration skills? Or show a case study that could only be achieved through collaboration?

7. What is the outtake of the presentation?

What narrative or story are you telling, and is it memorable and distinctive? Ideally, you want the client to feel that they do not know how they survived to date without you working on their business.

But what makes a marketer think that will depend on his or her own particular needs and circumstances, which is next to impossible to know. But you want to leave them with a powerful impression and a desire to know more. (This is a good measure of a great credentials presentation as it spontaneously has the audience asking you for more information and starting a discussion about how you could or would work together).

But also, when they walk away, what will be their impression of the agency later that day, tomorrow or in a week’s time? And how will they describe you to someone not in the presentation? That is the story or narrative you need to craft.

These are just the top seven most common and perhaps most obvious mistakes I see repeatedly. In 2011, I got so sick of seeing the same formulaic credentials I put together this spoof video of an agency to demonstrate how not to do it. The trouble is I think some agencies have mistaken this as a training video and missed the point.

However, having seen so many agency credentials presentations and how they impact a client looking for a new agency, I am happy to help any agency improve by providing raw and honest feedback. If you are up for it, let us know. Until then, I hope this has helped help you present your agency credentials.

Learn more about how we can help your agency improve its Agency Credentials and Market Positioning here.

By Darren Woolley

This post is by Darren Woolley, Founder and Global CEO of TrinityP3. With his background as an analytical scientist and creative problem solver, Darren brings unique insights and learnings to the marketing process. He is considered a global thought leader in optimizing marketing productivity and performance across marketing agencies and supplier rosters.

You might also like:

Managing Marketing: The State Of The Pitch In Australian Advertising

Creative Agency Pitch Consultation – Case study

100 consideration for marketers to avoid poor pitch performance

To contact us about how we can work with you, or to discuss a specific tailored project.

- Case Studies

- Distributor Search

- USA Development

- Workshops & Speeches

- Export Strategy

- Export Passport

- Prime Prospects

- Fix Problem Markets

- Export Express Newsletter

- Export Guides

- United States

- Distributor Management

- Hot Countries

- Export Handbook

Ten Tips: Your Company Credentials Presentation

Greg Seminara, Export Solutions

Distributors are flooded with requests for representation of brands from around the world. Normally, these presentations are jammed with pretty photos and long stories about the companies history. Brands will receive better response with a fact based, company credentials presentation focused on “What Distributors and Buyers really want to know”. Export Solutions recommends that brands create two versions of your credentials presentation: Ten page detailed presentation and a one page summary. Recapped below are our ten tips on developing a strong company credentials presentation to attract interest from Distributors and Buyers anywhere.

1. Just the Facts: Page 1 should include basic company facts. Annual sales, ownership, number of employees, and key categories and brands.

2. History Tell the story of when and how was the company founded. This is your chance to seduce the audience with a captivating story. Learn to tell the story in one page with no company video’s or DVD’s (boring!). Provide a longer version of your history and milestones on your company web site for those who want more information.

3. Brand USP This is the place for pretty pictures of your brand and the opportunity to demonstrate your category expertise. Why is your brand different ? How do you compare with current category assortment ? List any awards or recognition for your company.

4. Current Export Markets Share countries where your brand is currently available. Segment between core markets where your brand is strong and others where you maintain niche status. What is the rationale for entering the distributors country ?

5. Distributor and Retailer Partners Highlight well known distributors currently serving as your partners. List retailers who currently sell your brand. Logo’s work well.

6. Success Stories Focus on recent examples of your brand building results. Mention specific retailers or distributors if examples are well known retailers or in adjacent countries.

7. Investment Strategy Distributors and buyers demand critical information on how you plan to generate consumer awareness, trial, and repeat purchase of your product. Their interest will match your level of financial commitment.

8. Team Resources Publish photos of your export team. This includes marketing, finance, customer service, and logistics experts. List years of service for each team member to demonstrate that you have a strong support organization to build the business.

9. Sync with Web Site Your credentials presentation should sync with information on your web site. In reality, your web site is the first place that a potential distributor will visit. Modern web sites, with crisp graphics, minimal text, and no music will receive attention. Do you have a page dedicated to international export? When was the last time you updated your web site ?

10. Why is your Company a Good Partner ? This represents a one page summary of your company credentials. What value does your company bring to the partnership ? What is the “size of the prize” ? How will your brand make more money for the distributor or buyer ?

Export Solutions can help ! Export Solutions has participated in more than 300 Distributor identification projects and reviewed web sites of more than 10,000 Distributors and Brand Owners. We are available to review your company presentation or web site to provide timely ideas and suggestions to improve your visibility. Contact us in the USA at (001)-404-255-8387 for more information.

Free: 15 Export Guides and 50 Scorecards. Export Express monthly newsletter dedicated to Best Practices for international development through food distributor networks.

Advertisement

The Drum Awards Festival - Extended Deadline

- d - h - min - sec

What do the perfect agency credentials look like?

- Facebook Messenger

By Stefan Rhys-Williams , Senior account manager

The Future Factory

The Drum Network article

This content is produced by The Drum Network, a paid-for membership club for CEOs and their agencies who want to share their expertise and grow their business.

June 22, 2017 | 6 min read

Listen to article 4 min

Agency credentials and presentations continue to be a hot topic in the world of agency new business. But what makes a credential valuable? The Future Factory spoke to senior figures in the brand world, in search of answers to how agencies can best influence the purchasing decisions of brands. Unfortunately, they explained credentials often fall a little short of the mark…

Get to the point

Everybody thinks they’re busy; not having time to really focus or take anything in has become something of a status symbol. So it’s crucial to make the most of your prospect’s time and get your point across as effectively and concisely as possible.

The chief marketing officer of Rightmove has previously emphasised the importance of brevity and favours credentials which only take up a few slides long per case study. He says if five slides isn't sufficient, then “you’re clearly struggling to sell yourself”.

A director at Sonos is also unequivocal: “creds are far too long, they should be short, snappy and insightful”.

Be results-focused

So if it’s best to keep things short and to the point, what should you include? What eye-catching details help you stand out from the crowd? According to a head of PR at a major automotive brand, evidence of tangible value and results is crucial.

Now, in a world of brand equity, stakeholder engagement and other (more-or-less) intangibles, this can be difficult. But it’s worth bearing in mind that framing a case study in terms of tackling a challenge or solving a problem is preferable to a rambling account of the work you’ve done and what you like most about it. If you can measure the ROI your work has delivered then great – but it’s not always as simple as that. Include relevant testimonials and sector-specific insight too, and you’ll be on your way to leaving a great impression and demonstrating the value your agency can add to the brand team’s work.

Remember, even the sleekest credentials in the industry are best talked through rather than emailed in PDF form – get some face time in the diary by emphasising how much more valuable (for both sides) even a brief meeting tends to be.

Emphasise your culture

In addition to thinking carefully about the content and aiming for a deck that’s pithy and concise, it’s important to bear in mind the limitations of agency credentials. For a director at Bacardi, the agency team can be just as important as their case studies – “people buy people”.

Indeed, an over-reliance on credentials can be to the detriment of chemistry: “bring your personality”, advised another chief marketing officer.

Anything from photos of the office (dog) to a distinct and original tone of voice can help inject a bit of character and differentiate your agency in a vigorously competitive industry.

Acknowledge that credentials have their limitations

Knowing you have your well-thumbed credentials at your disposal can be a real source of comfort. Yes, you may have tailored these for a specific meeting, but you know them like the back of your hand and you might be relying on them too heavily. Don’t be afraid to stray from the path and leave the presentation behind.

A director at Diageo takes a similar view. He comments, “I never see a presentation as a presentation, I see it as a conversation… I don’t want to be talked at”. It’s important to be able to react to remarks and questions you may not have been expecting – and that means your credentials should facilitate, not dictate, the kind of conversation you’re having.

As one of our interviewees put it, “don’t present, engage”. Recognise there’s somebody else in the room: solipsism is off-putting and won’t get you very far.

Get a second opinion

Bear in mind that your favourite case study, or what you deem to be your best work, won’t always be as compelling to your prospect. Remember, even the most creative agencies in the world aren’t always best placed to do their own branding – so get another pair of eyes to look over your deck.

The agency marketplace is littered with companies that deliver great, inventive work for their clients but who neglect their own branding, websites and, in this instance, credentials.

Credentials are hard to get right, time consuming and sometimes don’t feel like an agency’s priority. But our research suggests that a decent set of collateral (as part of a broader marketing strategy) can make all the difference and really change how your business is perceived.

With so many agencies out there, sub-par credentials have become a really easy excuse for disregarding a particular approach or pitch – invest a bit and take them seriously.

The Future Factory is offering agencies the chance to get their creds reviewed for free over June. Click here to find out more.

Stefan Rhys-Williams is senior account manager at The Future Factory .

Content by The Drum Network member:

With a mix of lead generation, board level consultancy and coaching, we help to make the future more predictable for agency Owners, Founder and Directors. www.thefuturefactory.co.uk Since...

More from Marketing

Industry insights.

Tel: 01213 558092

Credentials Documents: Why Every Sales-Driven Business Should Have One

So, what could a credentials document do for you.

A credentials document is an essential part of marketing your business, especially if you work in a highly competitive, business-to-business industry.

Targeting a specific audience, a credentials document will demonstrate the capabilities of your business, the services you provide, the impact your work can and does have, and why your audience should choose to work with you.

What Should a Credentials Document Include?

A credentials document is almost like a CV for your business. It is a document that will be tailored for and sent to your business prospects in the hopes of bringing them on board as a client, demonstrating your past work and expertise.

A significant aspect of the credentials document’s structure is to include examples of your best work – hero pieces you are proud of! The work you’ll want to display should be relevant to the prospect you are approaching, demonstrating how you helped clients in the same industry or those with similar goals achieve their aims.

A great way to further support this is by adding client testimonials taken directly from those you work closest with. This way, prospects can understand the benefits of your services from a proven, external source rather than just from your existing marketing material. They will then be more likely to engage with you – there’s nothing better for business than a good review!

EDGE Creative can help you choose projects that were most successful and display them with clear objectives and results explained, just like our projects page.

Our personalised credentials documents outline who you are and what you do as well as feature case studies of successful projects, testimonials, and an attention-grabbing call to action. We can guide you on what your clients really want to see and piece together the perfect proposal tailored to your target audience.

How Should a Credentials Document Look?

First impressions are crucial, so your credential document needs to be well presented, on-brand, and relevant to your audience. Put yourself in your clients’ shoes for a moment: if you wanted to outsource a service, would you go for the provider with a clean, nicely designed credential document or the one who emailed over some attachments?

There are no rules on exactly how your document should be laid out or presented, but it is always best to ensure it stays true to your brand and expresses all the information clearly and without clutter.

EDGE will work with you to ensure your brand is represented correctly and make you and your company really stand out – it’s what we do best!

How Can We Help You?

At EDGE, we provide a fully integrated marketing service, offering an initial consultation and strategic advice on what approach would work best for your clients, through to on-brand design, copywriting and personalisation to create a unique piece just for you.

Our talented design team can craft your credentials document to suit various marketing channels such as on-screen, printed, digital download and page turning software.

Your credentials document can be edited and personalised for every client individually, so you can be sure that your credentials document has longevity and can evolve as you do, meaning it’s a marketing investment you can’t afford to be without. If you’re still not sure why you need one, check out our case study to see how we have helped Fidelis Group grow their business!

If you’d like to speak to us about starting your credentials document today, please reach us on 0121 355 0892 or email [email protected].

Alternatively, browse our range of services and see how we can help your brand or business with brand development , search engine optimisation , social media marketing and more.

STAY UP TO DATE WITH OUR LATEST UPDATES

Subscribe and get all our updates on our events, activity and news from the digital marketing industry.

By clicking the 'Subscribe' button you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy

Related Blog Posts

8 tips to creating a design credentials pitch for a client

I often get asked from clients as part of a design proposal, “what is the process for?a?design project?” ?to “ how much does it cost to design x?” and “have you done anything similar to what we want?”

In this article I will break down a credentials pitch document into eight sections.

This Credential Pitch document that I have previously used for new clients provided a detailed overview of who we are, what we do, our process, fees and how we work – along with relevant case studies and client testimonials. This was created in an A4 format and sent to the client.

Of course, each one is personally crafted to a new client proposal and this one below is an example based on a website design project for a charity but I’ve used Apple Inc. as a demonstration client in this example.

The following I will break each section down for you with a little explanation and an image.

1. Introductory letter

Firstly, I provide a?signed?introductory letter explaining what the document contains and any other communications.This helps to prepare the client as an opening to what’s involved, giving an overview before going further.

2. Credentials cover page

The cover should contain some branded graphics or imagery that is consistent with your identity, who prepared it and who is it for. And it really helps to have the logo’s partnered together side by side on the cover. This promotes the partnership they will be entering into.

3. Who we are page

A clear, short?and concise?biography of the company gives the client a clear understanding of your approach and why they should choose you. This is then followed by introducing who will be?specifically?working on their design project:

4. What we do page

A?short description about what you specialise in that fits to their design requirements. So following on from the previous page about who you are, go into a little more detail about what you?do:

5. Our process page

This gives the client an insight into how you?will be working with them, what they expect at each stage and what the costs will involve.

6. An idea of our process…

If you take?two or three of your main design services and?briefly detail each process on?what the client will get,?educates and demystifies your services for the client. It also saves you time explaining each time a new client asks you.

7. Case studies

For each individual client, you will need to tailor your case studies so that they are relevant to their design project. In my designs, I have not only selected?case studies from similar?clients, but designs that?showed similar requirements?to this design project.

8. Client testimonials page

On the final page, have relevant, up to date testimonials that backs up all?the content you’ve provided and shows your experience working with a variety of client design projects.

This Credentials Pitch document?is based on The Five C’s from?this article on?the Design Business Association blog

Andy Fuller

Spread the word.

© Designbull. All rights Reserved. | Terms | Privacy | Disclaimer

Made with ❤ by Designbull

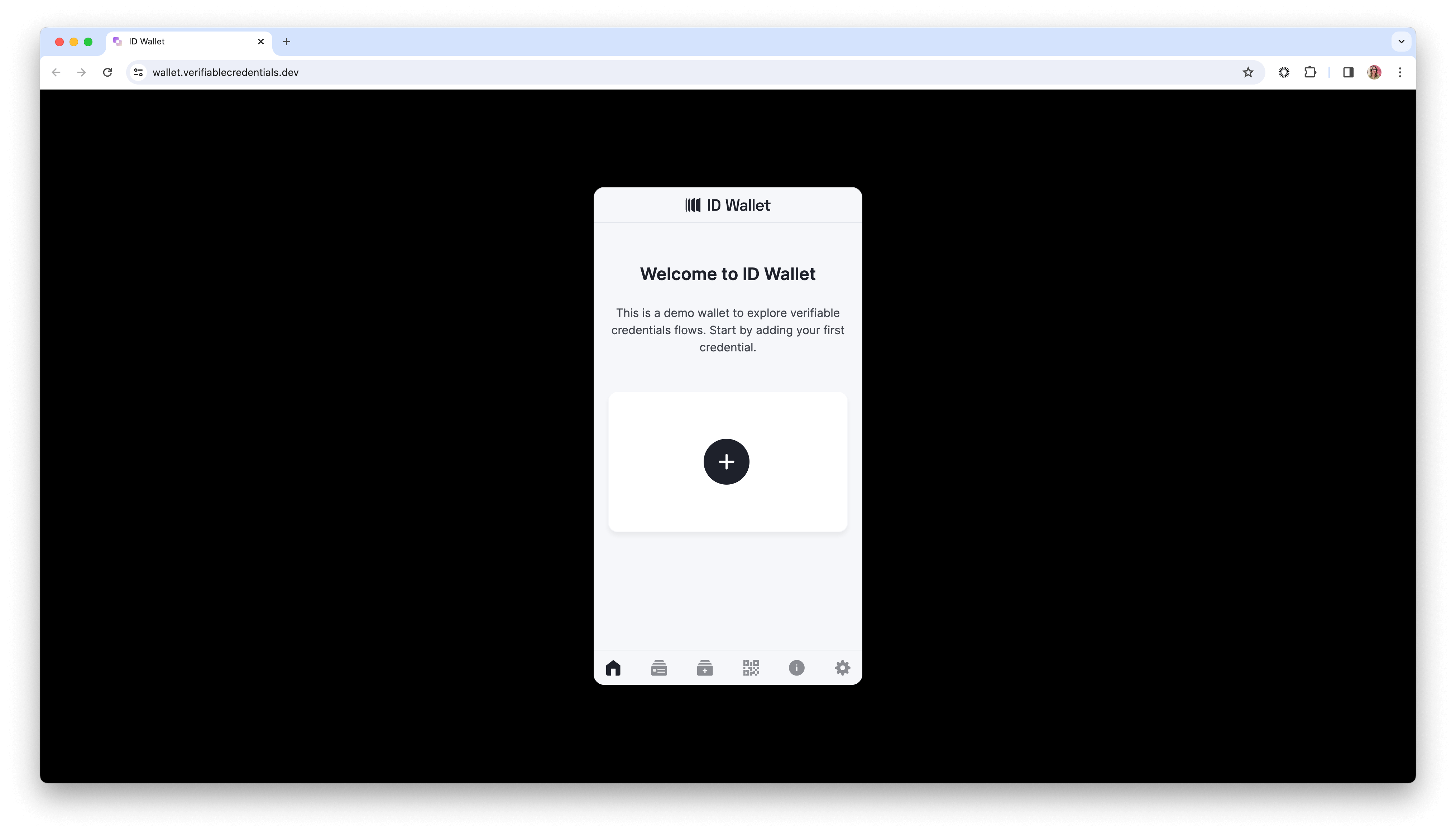

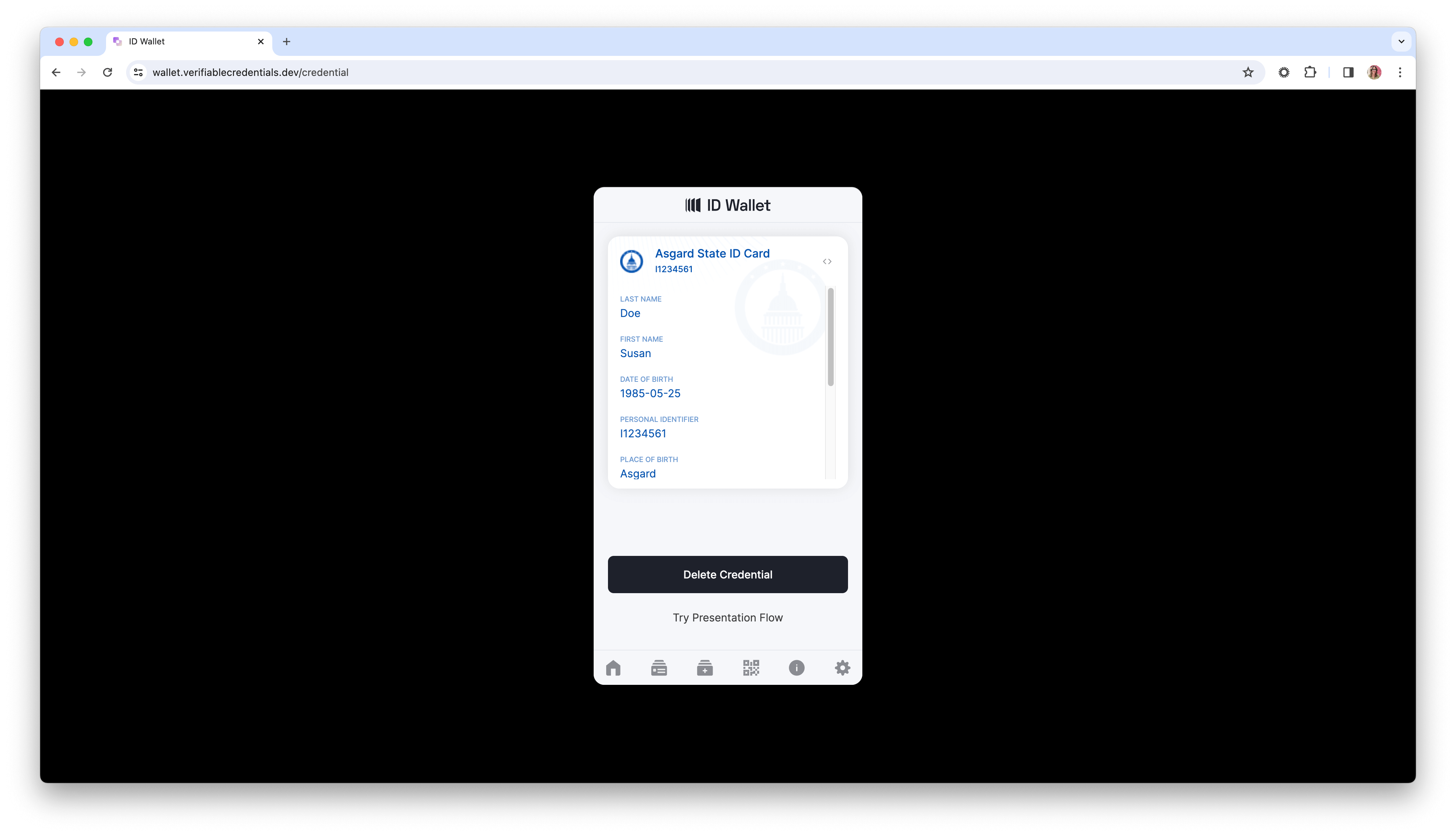

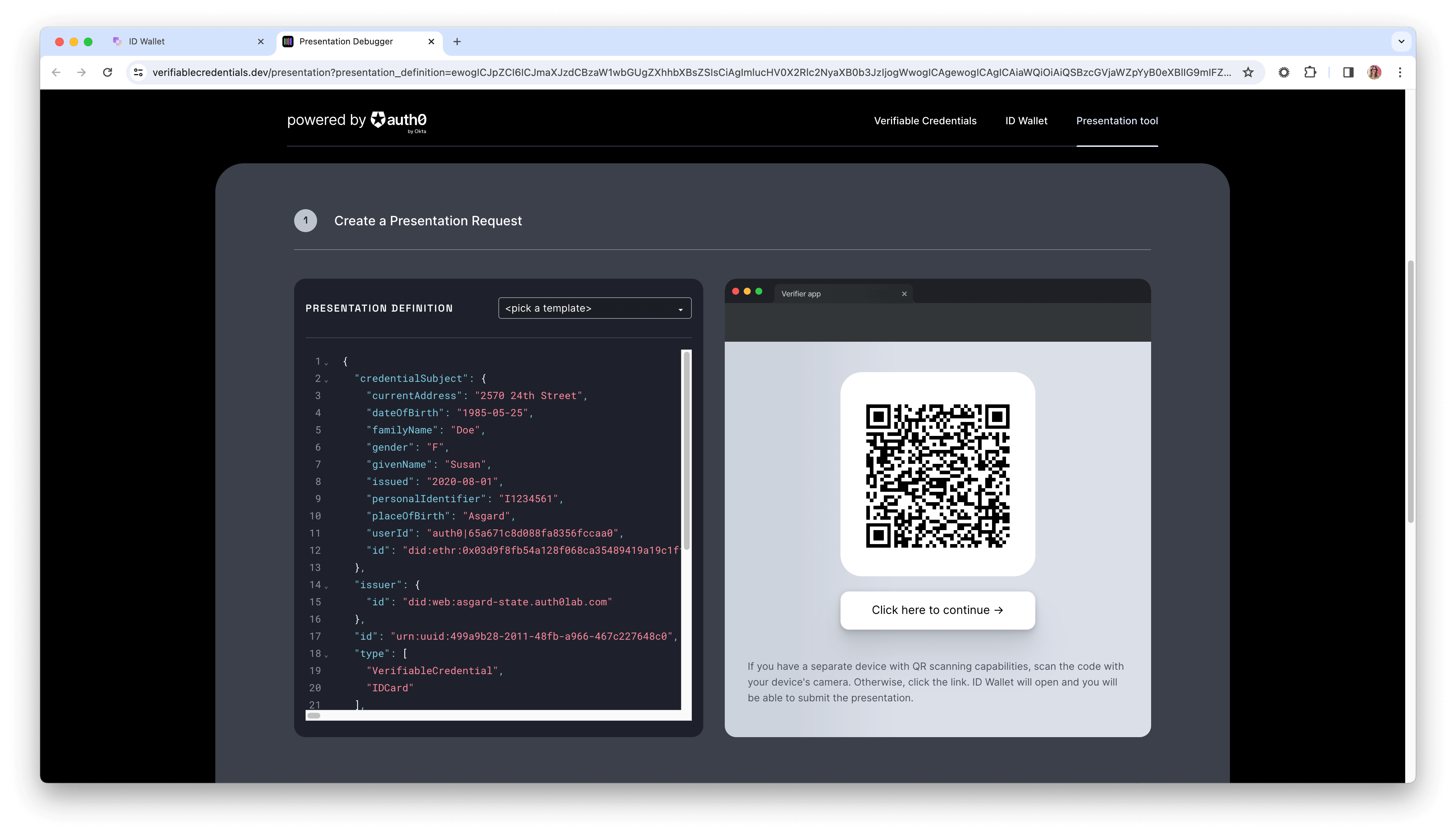

Verifiable Credentials Data Model v1.1

W3C Recommendation 03 March 2022

See also translations .

Copyright © 2022 W3C ® ( MIT , ERCIM , Keio , Beihang ). W3C liability , trademark and permissive document license rules apply.

Credentials are a part of our daily lives; driver's licenses are used to assert that we are capable of operating a motor vehicle, university degrees can be used to assert our level of education, and government-issued passports enable us to travel between countries. This specification provides a mechanism to express these sorts of credentials on the Web in a way that is cryptographically secure, privacy respecting, and machine-verifiable.

Status of This Document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of its publication. A list of current W3C publications and the latest revision of this technical report can be found in the W3C technical reports index at https://www.w3.org/TR/.

Comments regarding this specification are welcome at any time, but readers should be aware that the comment period regarding this specific version of the document have ended and the Working Group will not be making substantive modifications to this version of the specification at this stage. Please file issues directly on GitHub , or send them to [email protected] ( subscribe , archives ).