- Create new account

- Reset your password

Gendered Impact on Unemployment: A Case Study of India during the COVID-19 Pandemic

India witnessed one of the worst coronavirus crises in the world. The pandemic induced sharp contraction in economic activity that caused unemployment to rise, upheaving the existing gender divides in the country. Using monthly data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy on subnational economies of India from January 2019 to May 2021, we find that a) unemployment gender gap narrowed during the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison to the pre-pandemic era, largely driven by male unemployment dynamics, b) the recovery in the post-lockdown periods had spillover effects on the unemployment gender gap in rural regions, and c) the unemployment gender gap during the national lockdown period was narrower than the second wave.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has adversely impacted labour markets all around the world. According to the International Labour Organization, the working hours lost in 2020 were equal to 255 million full-time jobs, which translated into labour income losses worth US$3.7 trillion (International Labour Organization 2021). Due to the existing gender inequalities, women were more vulnerable to the economic impact of COVID-19 (Madgavkar et al. 2020). The sudden closure of schools and daycare centres due to the Great Lockdown exacerbated the burden of unpaid care on women (Collins et al. 2020; Power 2020; Czymara et al. 2020; Seck et al. 2021). Women also disproportionately represented the accommodation, food services, and retail and wholesale trade sectors, which were worst-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic (Alon et al. 2020; Adams-Prassl et al. 2020; Bonacini et al. 2021). In most countries, women often work in these sectors without any work protection or job guarantee (United Nations Women 2020), leading them to loose their livelihoods faster than men while also dealing with their deteriorating mental health. India is an interesting case study with one of the lowest female labour force participation rates (LFPRs) globally to analyse how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the pre-existing gender disparities in unemployment. According to the World Bank data, India’s female LFPRs was approximately 21% in 2019, the lowest among the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and 26 percentage points lower than the global average. An even more troubling fact is that women’s LFPRs has been falling since the mid-2000s (Ghai 2018; Andres et al. 2017; Sarkar et al. 2019). Since the onset of the pandemic, women in India have been increasingly dropping out of the labour force. As seen in Figure 1, the greater female labour force, which comprises unemployed females who are active and inactive job seekers, has been lower than the pre-pandemic average since April 2020. The number of unemployed women actively looking for jobs has also been lower than the pre-pandemic average barring the months of April, May, and December in 2020. On the contrary, the number of women who are unemployed but inactive in their job search has risen drastically, albeit with minor fluctuations, during this period (Figure 2). A recent survey by Deloitte (2021) identified that the burden of household chores and responsibility for childcare and family dependents increased exponentially for women worldwide and more so in India due to the pandemic. The surveyed women mentioned increase in work and caregiving responsibilities as the main reasons for considering leaving the workforce.

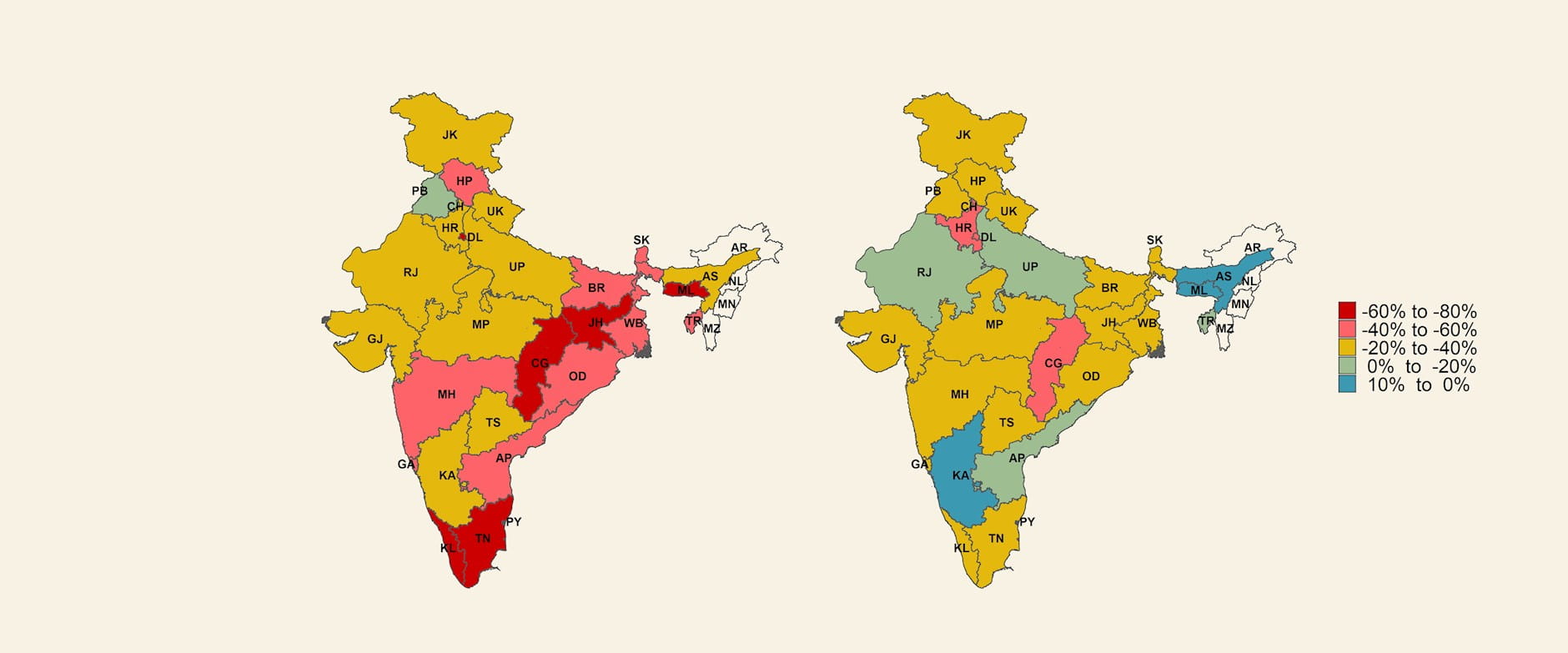

Figure 1 : Percent Change in Female Greater Labour Force and Unemployed Active Job Seekers Compared to the Pre-pandemic Average

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy April 2020 - May 2021

Figure 2: Percent Change in Female Unemployed and Inactive Job Seekers Compared to the Pre-pandemic Average

Figure 3: Unemployment Rate in India (Percent)

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Jan 2020 - May 2021

This study analyses the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the gender unemployment gap from its onset until the second wave using the subnational-level monthly data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). The gender unemployment gap is defined as the difference between male and female unemployment rates ( Albanesi and Şahin 2018 ). We assess the gender unemployment gap during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic era using a difference-in-differences (DID) model. A preliminary investigation of the gender unemployment gap based on the raw data reveals that the gap declined in the lockdown period compared to the pre-lockdown period (Figure 3). We find the gender gap to widen during the second wave, albeit smaller than the pre-pandemic level.

Although a large number of national-level studies were conducted on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unemployment (Estupinan and Sharma 2020; Estupinan et al. 2020; Bhalotia et al. 2020; Chiplunkar et al. 2020; Afridi et al. 2021; Deshpande 2020; Desai et al. 2021), this study is among the very first to assess the impact of the second wave of COVID-19 on the unemployment gender gap in India. A previous study found the rise in male unemployment during the lockdown period contributing to a smaller gender gap (Zhang et al. 2021). In this study, we take one step further to assess the effect of the second COVID-19 wave on the unemployment gender gap in India.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. In Sections 2 and 3, we present the data sources and some facts on the unemployment trend in India. The effects of first and second COVID-19 waves on unemployment disaggregated by gender are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 delves into the gendered impact on unemployment dynamics across urban and rural regions. The concluding remarks are presented in Section 6.

Data and Methodology

In this study, we use the subnational-level monthly employment data from the CMIE from the period of

January 2019 to May 2021 . Starting from January 2016, the CMIE has been conducting household surveys in India on a triennial basis, covering the periods of January to April, May to August, and September to December. This is the only nationally representative employment data in the absence of official government data (Abraham and Shrivastava 2019) and has been used by several employment studies on India (Beyer et al. 2020; Deshpande 2020; Deshpande and Ramachandran 2020).

The employment data are classified into three categories—the number of persons employed, the number of persons unemployed and actively seeking jobs, and the number of persons unemployed and not actively seeking jobs. The sum of these three categories constitutes the greater labour force. The data are also disaggregated by gender (male and female) and residence (rural and urban).[1] For the analysis, we focus on five time periods as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Time Periods

For state[2] i at time t, we construct the unemployment rate as given below:

Unemployment rate = Number of persons unemployed and seeking jobs/Greater labour force (1)

Stylised Facts on Unemployment

This section describes some stylised facts based on the subnational unemployment data from February 2019 to May 2021. To this end, we estimate the regression model below:

where Unemp it is the unemployment rate of state i in time t . To see the unemployment dynamics over the period of study, we use a binary variable Month s that takes the value one for month s and 0, otherwise. The model takes into consideration the impact of past unemployment rates, represented by Unemp it −1. Additionally, the state fixed effects δ i are included to account for unobserved, time-invariant state-level characteristics that may potentially confound our estimates.

Figure 4: Trends in Unemployment Rate

Our coefficient of interest is β 1 s which depicts the time trend in unemployment. The results from the model estimation are shown in Figure 4, in which we can see the dynamics of aggregate unemployment in India from February 2019 to May 2021. The vertical axis pertains to coefficient β 1 s , and the horizontal axis corresponds to the respective months. In Figure 4, the aggregate unemployment rate is found to be relatively stable during the pre-pandemic era. This trend faces an overhaul during the national lockdown (April–May 2020) with a structural upward shift in the unemployment rate. The shock to the unemployment rate does not persist as economic recovery during the post-lockdown period enables unemployment to fall steadily from June 2020 onwards. The unemployment rate becomes stable from January to March 2020 as the country returned to a sense of normalcy with the continued resumption of economic activity.[3] However, the economic impact from the onset of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic caused the unemployment rate to rise again in April and May 2021.

Next, we estimate Equation (3) separately for the female and male unemployment rates to assess the gender differential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on unemployment in India.[4]

where binary variable Quarter s takes the value one for quarter s in the time period of our sample. The model also accounts for lagged unemployment effects through Unemp it −1.

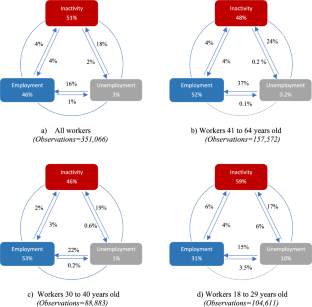

Figure 5: Trends in Unemployment Rate by Gender

Figure 5 shows that a stark gender gap in the unemployment rate (distance between the red and blue lines) exists in the pre-pandemic era as the male unemployment rate is consistently lower than that of the female. Figure 5 also shows that the gender gap dynamics are primarily driven by male unemployment. The sharp rise in male unemployment during the national lockdown causes the gender gap to close in Q2 2020. The post-lockdown recovery (Q3–Q4 2020) is found to have a favourable impact on male unemployment, causing gender gap to revert to the pre-pandemic levels. Although both males and females lost jobs during the onset of the second wave (Q2 2021), the gender gap narrowed as males are found to lose more jobs in absolute terms.

Figure 6: Trends in Urban and Rural Unemployment Rate by Gender

Figure 6 shows the estimates of β 1 s (see Equation [3]) for urban and rural unemployment in Panels (a) and (b), respectively. During the national lockdown, the sharp rise in male unemployment is more evident in urban areas than rural. In fact, the national lockdown period dynamics in aggregate male and female unemployment in Figure 5 largely resemble the effects seen in the urban region (see Figure 6, Panel [a]). The post-lockdown recovery suits male unemployment, both in rural and urban areas. Female unemployment remains stable in rural areas during the pandemic.

Figure 7: Trends in Regional Unemployment Rate by Gender

7 c

The subsample regression estimates of β 1 s pertaining to the north, east, west and south regions are shown in Figure 7. All regions witnessed a rise in male unemployment during the national lockdown period. On the contrary, the female unemployment dynamics differ between regions. During the national lockdown period, female unemployment rose in the west and south regions (Panels [c] and [d] in Figure 7). The north region shows an interesting anomaly (Panel [a] in Figure 7). Contrary to other regions, female unemployment dipped steeply in the north during the national lockdown period. East region alone did not

experience any strong movements in female unemployment throughout the pandemic (Panel [b] in Figure 7).

Impact of COVID-19 on Unemployment

Section 3 discussed how the overall unemployment and unemployment gender gap witnessed structural breaks during the COVID-19 pandemic. To further investigate the gender aspect of the COVID-19 unemployment dynamics in India, we begin our empirical exercise by examining the unemployment changes during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic era. We use the following model:

where Period 1 , Period 2 , Period 3 , and Period 4 pertain to lockdown, post-lockdown, post-lockdown normalcy, and second wave time periods, respectively. Besides the overall unemployment, we also estimate Equation (4) for male and female unemployment separately. The results are shown in Table 2. We can see from Column (1) of Table 2 that the overall unemployment rate ( β 11 ) witnessed an increase of 0.066 (statistically significant at one percent level) during the lockdown period in comparison to the pre-pandemic period. This effect was primarily driven by the rise in the male unemployment that shot up by 0.082 during the lockdown period (Column [3]).

The uneven distributional effects of the post-lockdown recovery are seen from β 12 estimates. Male unemployment rose by 0.01, while female unemployment fell by 0.036 in comparison to the pre-pandemic era. The fall in female unemployment does not necessarily indicate that the overall labour conditions improved for women during this period. Equation (1) shows that the unemployment rate is driven by two components. Figure 1 validates that the female unemployment rate fell over time due to the decline in the number of unemployed females actively seeking jobs being higher than the decline in the female labour force.[5]

β 14 estimate in Column (1) indicates that the total unemployment rose by 0.019 (statistically significant at 10 percent level) during the second wave compared to the pre-pandemic period. A comparison between β 14 and β 11 estimates reveals an interesting policy highlight that the second wave’s impact on unemployment was smaller than the nationwide lockdown. Finally, the rise in unemployment during the second wave is primarily driven by male unemployment.

Table 2: Impact of COVID-19 on Unemployment

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, and * p<0.1. The robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Unemployment Gender Gap in Urban and Rural Regions

This section delves further into the gendered impact of lockdown on the unemployment dynamics across urban and rural regions. As defined in Section 1, the unemployment gender gap measures the difference between female and male unemployment rates. To identify the effect of the first and second COVID-19 waves on the unemployment gender gap, we estimate the regression model below:

where Female is a binary variable that takes the value 1 for female unemployment and 0, otherwise.

Table 3 shows the estimation results of Equation (5). We discuss the coefficient estimates that are found to be significant. The significant β 1 coefficient reiterates that the unemployment gender gap was an existential problem in India even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The β 31 estimates reveal that the urban region dynamics drove the narrow unemployment gender gap during the lockdown period. Although the magnitude of the narrowing gap during the lockdown did not persist to the post-lockdown period ( β 32 ), rural regions experienced a narrow unemployment gender gap (marginally significant at 10%). This trend continues even in the post-lockdown normalcy period ( β 33 ) as the unemployment gender gap is narrower than the pre-pandemic level by 0.047 in the rural region. This highlights the possibility that the post-lockdown recovery process had a spillover effect on the unemployment gender gap in rural regions. Finally, β 34 estimates show that the narrowing gender gap trend persists only in the urban region during the second wave.

Table 3: Impact of COVID-19 on Unemployment across Urban and Rural Regions during the post-lockdown and post-lockdown normalcy periods.

This article analyses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic vis-à-vis the pre-pandemic period on the gender unemployment gap. Our findings indicate that the gender gap in unemployment narrowed during the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily driven by male unemployment dynamics. Interestingly, we find that female unemployment declined during the post-lockdown period. Such a decline was likely driven by women dropping out of the labour force rather than a dip in the absolute number of unemployed persons. Further, the region-wide subsample analysis finds the unemployment gender gap in urban regions to narrow across all periods of the COVID-19 era. In contrast, the rural regions witness narrowing gender gap during the post-lockdown normalcy. This indicates that the rural regions’ unemployment gender gap witnessed spillover effects from recovery associated with the economic reopening. Finally, the narrow gender gap (compared to the pre-pandemic level) is smaller during the second wave.

There is a looming uncertainty whether the impending third wave will further narrow the gender unemployment gap at the expense of increasing male unemployment and females being pushed out of the workforce. Further research is required with a more extended period of assessment and focussed on household-level data to understand the difference in the impact of COVID-19 on the gender unemployment gap across the different parts of the country and income strata.

The authors thank Paul Cheung and the anonymous referee for their valuable comments and feedback. They also thank Rohanshi Vaid for her excellent research assistance.

[1] The data are not available for Jammu and Kashmir, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Sikkim. Hence, the main analysis focuses on only 26 subnational economies.

[2] The terms “state” and “subnational economy” are used interchangeably throughout the article.

[3] According to the official data, power consumption grew by 10.2% in January 2021; the highest growth rate in three months, which was indicative of higher commercial and industrial demand (Press Trust of India 2021).

[4] In order to obtain the unemployment dynamics on a quarterly basis, Equation (2) is revised to Equation (3) with dummies pertaining to quarter instead of month.

[5] This reason is also validated by CMIE who found the female labour participation in urban regions to fall to 7.2% in October 2020, the lowest since the organisation started measuring this indicator in 2016 (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy 2020).

Abraham, Rosa and Anand Shrivastava (2019): “How Comparable Are India’s Labour Market Surveys? An Analysis of NSS, Labour Bureau, and CMIE Estimates,’’ Azim Premji University CSE Working Paper 2019-03.

Adams-Prassl, et al (2020): “Work Tasks That Can be Done From Home: Evidence on Variation Within & Across Occupations and Industries,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14901.

Afridi, Farzana, Kanika Mahajan and Nikita Sangwan (2021): “Employment Guaranteed? Social Protection during a Pandemic,” Oxford Open Economics, Vol 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/ooec/odab003 .

Albanesi, Stephania and Ayşegül Şahin (2018): “The Gender Unemployment Gap,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol 30, pp 47–67.

Alon, Titan, et al (2020): “The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality,” Technical Report w26947, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Andres, Luis A, et al (2017): “ Precarious Drop: Re- Assessing Patterns of Female Labor Force Participation in India ,” Technical Report 5595-1149, Vol 8024, World Bank, Washington DC.

Beyer, Robert C.M., Tarun Jain and Sonalika Sinha (2020): “Lights Out? COVID-19 Containment Policies and Economic Activity,” Policy Research Working Papers , The World Bank.

Bhalotia, Shania, Swati Dhingra and Fjolla Kondirolli (2020): “City of Dreams no More: The Impact of Covid-19 on Urban Workers in India,” Centre for Economic Performance, https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepcovid-19-008.pdf.

Bonacini, Luca, Giovanni Gallo and Sergio Scicchitano (2021): “Working from Home and Income Inequality: Risks of A ‘New Normal’ With COVID-19,” Journal of Population Economics , Vol 34, No 1, pp 303–60.

Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (2020): “Female Workforce Shrinks in Economic Shocks.” www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=20201214124829&msec=703&ver=pf

Chiplunkar, Gaurav, Erin Kelley and Gregory Lane (2020): “Which Jobs Are Lost during a Lockdown? Evidence from Vacancy Postings in India,” SSRN Journal. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3659916

Collins, Caitlyn, et al (2020): “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours,” Gender, Work & Organization , Vol 28, pp 101–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506 .

Czymara, Chritian S., Alexander Langenkamp and Tomás Cano (2020): “Cause For Concerns: Gender Inequality In Experiencing The COVID-19 Lockdown In Germany,” European Societies , Vol 23, Sup 1, pp 1–14.

Deloitte (2021): “Women @ Work: A Global Outlook India Findings,” https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/about-deloitte/in-women-at-work-india-outlook-report-noexp.pdf.

Desai, Sonalde, Neerad Deshmukh and Santanu Pramanik (2021): “Precarity in a Time of Uncertainty:

Gendered Employment Patterns during the Covid-19 Lockdown in India,” Feminist Economics , Vol 27, Nos 1–2, pp 152–72.

Deshpande, Ashwini (2020): “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Gendered Division of Paid and Unpaid Work: Evidence from India,” IZA – Institute of Labor Economics.

Deshpande, Ashwini and Rajesh Ramachandran (2020): “Is Covid-19 ‘The Great Leveler’?” The

Critical Role of Social Identity in Lockdown-induced Job Losses , GLO Discussion Paper 622, Global Labor Organization (GLO).

Estupinan, Xavier and Mohit Sharma (2020): “Job and Wage Losses in Informal Sector due to the COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in India,” SSRN Electronic Journal .

Estupinan, Xavier, et al (2020): “Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Labor Supply and Gross Value Added in India,” SSRN Electronic Journal .

Ghai, Surbhi (2018): “The Anomaly of Women’s Work And Education In India,” Working Paper 368, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), New Delhi.

International Labour Organization (2021): “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Seventh

Edition,” Updated Estimates and Analysis. Int Labour Organ .

Madgavkar, Anu, et al (2020): “COVID19 and Gender Equality: Countering The Regressive Effects,” McKinsey Global Institute, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects .

Power, Kate (2020): “The COVID-19 Pandemic has Increased the Care Burden of Women and

Families,” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy , Vol 16, No 1, pp 67–73.

Press Trust of India (2021): “India’s Power Consumption Grows At 3-Month High Rate Of 10.2% In January,” Business Standard India , https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/india-s-power-consumption-grows-at-3-month-high-rate-of-10-2-in-january-121020100353_1.html.

Sarkar, Sudipa, Soham Sahoo, and Stephan Klasen (2019): “Employment Transitions Of Women In

India: A Panel Analysis,” World Development , Vol 115, pp 291–309.

Seck, Papa A., et al (2021): “Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 in Asia and the Pacific: Early Evidence on Deepening Socioeconomic Inequalities in Paid and Unpaid Work,” Feminist Economics , Vol 27, Nos 1–2, pp 117–32.

United Nations Women (2020): “From Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19,” Technical report, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2020/Gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-COVID-19-en.pdf.

Zhang, Xuyao, et al (2021): Annual Competitivness Analysis and Gendered Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Unemployment in the Sub-National Economies of India , Singapore: Asia Competitiveness Institute, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Image Courtesy; Canva

In light of the triple talaq judgment that has now criminalised the practice among the Muslim community, there is a need to examine the politics that guide the practice and reformation of personal....

- About Engage

- For Contributors

- About Open Access

- Opportunities

Term & Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Style Sheet

Circulation

- Refund and Cancellation

- User Registration

- Delivery Policy

Advertisement

- Why Advertise in EPW?

- Advertisement Tariffs

Connect with us

320-322, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai, India 400 013

Phone: +91-22-40638282 | Email: Editorial - [email protected] | Subscription - [email protected] | Advertisement - [email protected]

Designed, developed and maintained by Yodasoft Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Employment and Earning in Urban India during the First Three Months of Pandemic Period: An Analysis with Unit-Level Data of Periodic Labour Force Survey

Anindita sengupta.

Barrackpore Rastraguru Surendranath College, West Bengal State University, Barrackpore, 85, Middle Road, North 24 Parganas, 700120 West Bengal India

Urbanisation has accelerated the pace of development throughout the world. Big cities provide employment and livelihood for workers because of which workers have always migrated from rural areas to cities. However, in India, most of the migrant workers are absorbed in the low-paid and low-skilled jobs in the widespread informal sector. With the outbreak of COVID-19, lockdown was declared suddenly without any notice in India during the last week of March 2019 and most of the urban informal sector workers suddenly lost their jobs, and since they had no protection, they were pushed into poverty. Detailed analysis of such losses is of utmost importance so that perfectly appropriate remedial measures can be taken by the government. Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) report of 2019-20 has analysed the situation of labour market in India for four quarters from July 2019 to June 2020. Therefore, the last quarter of the data will give us the valuable information about the urban labour market during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic period. This study analyses the possible reasons behind decline in monthly earnings and labour market participation of urban people in India during the period of outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, i.e. during the period from April 2020 to June 2020, using the data of fourth quarter from each of the PLFSs of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 since they have identical seasonal conditions. We have used cross-tabulation method to find out employment and unemployment rates of people in urban areas according to gender and type of employment for the period, from July to June, for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020. We have also tried to find the reasons behind the decline in income of workers during the first three months of the pandemic period, i.e. during the fourth quarter of 2019-20, compared to the fourth quarter of 2017-18 and that of 2018-19 using the Mincerian wage equation. Our empirical results have shown that urban workers in India have lost jobs and suffered from significant decline in income during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic period in almost all types of employment.

Introduction

Urbanisation has accelerated the pace of development throughout the world. Big cities provide employment and livelihood for workers because of which workers have always migrated from rural areas to cities. Regular wage/salaried employees make up nearly half of the urban workforce (48.8% in 2019-20), and the rest are in a hinterland of casual work, temporary contracts and self-employment. Even among regular employees, only 33.2% have a written employment contract while 49.0% have access to paid leave and 48.9% some social security benefits (provident funds, sick pay, health insurance) through the government or their employer (Source: PLFS 2019–20). Majority of urban workers, including those who migrate from rural areas, are absorbed in the low-paid and low-skilled jobs in the widespread informal sector. Most of these urban informal sector jobs lack written contracts, paid leave and social securities. Migrant workers usually live in the urban slum areas and earn very low level of income which barely covers their subsistence level of living. However, availability of informal sector jobs throughout the year attracts workers in urban areas.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, lockdown was declared suddenly without any notice in India during the last week of March 2020; and most of the urban informal sector workers suddenly lost their jobs and since they had no protection, they had been pushed into poverty. India witnessed large-scale return migration of these helpless and vulnerable workers back to the rural areas. This return migration was in the news headlines for a long time and this tragedy has long been widely discussed throughout the world. Due to the dearth of reliable data of loss of employment and drastic decline in earning of urban workers during the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic and declaration of lockdown, it has been difficult for the researchers to measure the extent of such loss.

Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) report of 2019-20 has analysed the situation of labour market in India for four quarters from July 2019 to June 2020. Therefore, it is evident that the last quarter of the data would give us the valuable information about the urban labour market during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic period. According to the PLFS Report, 11.49% of total male labour force was unemployed during the months of April to June of 2018; although the percentage share declined to 10.14% during the same months of 2019, it increased to 19.15% during the same months of 2020, i.e. during the initial three months of pandemic. During April to June of 2018, mean urban earning was Rs. 27,913.15, which increased to Rs. 33,375.44 during the same months of 2019; however, it once again declined to Rs. 28,595.15 during the same months of 2020 at constant 2012 prices (Base: 2012 = 100 for CPI for urban areas). 1 From these overall figures, it is quite clear that urban workers in India suffered from huge loss of employment and earning in the first three months after the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. However, detailed analysis of such losses is of utmost importance so that a perfectly appropriate remedial measure can be taken by the government.

A few researchers and columnists have tried to measure the extent of loss of the pandemic affected urban labour market of India. Bhalotia et al. ( 2020 ) have discussed about the impact of COVID-19 on urban workers in India using the LSE-CEP Survey. They have discussed about COVID-19 and the Urban Poor in www.orfonline.org . Kumar and Srivastava ( 2021 ) have discussed about impact of COVID-19 on employment in urban areas using the PLFS 2019-20 data in a blog in www.prsindia.org . IANS ( 2021 ) has come up with an article on unemployment, COVID-19 and top most worries for urban Indians using Ipsos ‘What Worries the World’ global monthly survey. However, there is no detailed empirical analysis regarding the job loss and reduction in income of urban workers in India during the commencement of the lockdown in 2020. Against this backdrop, this paper tries to analyse the decline in employment rate and average monthly income in urban areas during the first quarter of pandemic in India and compare this situation with the that during the same quarters of two preceding years using the PLFS data of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019=20.

In this paper, we have used the unit-level data of PLFS of 2017-18, 20-19 and 2019-20 published by National Statistical Office (NSO), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. The data of each round are divided into four quarters from July to June. This implies that the last three months of the 2019=20 round would give us the information about the labour market of India during the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic and commencement of nationwide lockdown. We have used cross-tabulation method to find out percentage shares of employed and unemployed people in urban areas according to gender and type of employment for the period from April to June, for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020. We have also tried to find the reasons behind the decline in income of workers during the first three months of the pandemic period, i.e. during April to June of 2020, compared to the same months of 2018 and 2019 using the Mincerian wage equation. Since the dataset has many people who are unemployed and not earning any income, we have used the Heckman’s two-stage selection model to remove the sample selection bias. In this two-step approach, we first conducted a probit model regarding whether the individual has participated in the labour market or not, in order to calculate the inverse Mills ratio or ‘non-selection hazard’. In the second step, we followed the OLS wage regression model. In order to find out the significant reasons behind changes in employment in the first equation and changes in income in the wage equation during the period from April to June of different years, we have used several interaction dummy variables interacted with the year of pandemic.

In what follows, Section 2 describes the data and the samples used in this study. Trends of usual status employment and unemployment rates and average earnings of urban male and female workers across different types of employment during April to June of 2018, 2019 and 2020 are examined in Section 3 . Section 4 deals with methodological issues in estimating the wage equation after correcting for the sample selection bias. Empirical estimates are analysed in Section 5 . Section 6 concludes.

Data and Sample

From 1 April 2017, the NSSO has adopted a new employment and unemployment survey called Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS, which has now become the major employment and unemployment data of the NSSO; replacing the previous 5-year surveys). The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) has already published three PLFS annual reports for the year 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20. The data are divided into four quarters from July to June for each report. This implies that the data of last three months of 2019-20 would give us the information of labour market of India during the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic and commencement of nationwide lockdown. Since dataset of urban workers is a rotational panel data in each PLFS, in case of only the data of quarter 1 with visit 1, quarter 2 with visit 2, quarter 3 with visit 3, and quarter 4 with visit 4 contain the same households and they form a complete panel. Therefore, full data of quarter 1, quarter 2 and quarter 3 are not comparable with the full data of quarter 4. Furthermore, employment in India is predominantly informal sector employment, which suffers from seasonal effect. Therefore, in order to compare situation of workers in pre-COVID and COVID period, we have decided to compare data of fourth quarter from each of the PLFSs of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 (schedule 10.4) since they have identical seasonal conditions.

Trends of Employment and Unemployment Rates and Average Earning of Urban Workers

The estimates of employment and unemployment rates of urban male and female workers during the period April to June of three consecutive years 2018, 2019 and 2020 on the basis of observed data provide us gross idea about the employment pattern in urban areas during pre-pandemic and initial phase of pandemic period. Percentage shares are calculated by using sampling weights constructed from the multiplier by following the norms provided in NSS schedules to get the corresponding values for the population.

Table 1 describes the employment and unemployment rates of urban men and women during April to June of 2018, 2019 and 2020. Here we have considered the fourth quarter and first visit for each survey to maintain the comparability and seasonality. We have restricted our analysis for the age group of 15 to 60 years. 2 It is clear from the table that unemployment rate declined for both urban men and women for the period from April to June of 2018 to that of 2019, although it increased once again for both during the same months of 2020. Unemployment rates of urban women have been much higher compared to those of urban men for both usual principal status and usual principal plus subsidiary status throughout the whole period of our analysis.

Usual status (principal and subsidiary) employment and unemployment rates of men and women (age group of 15–60 years) in urban areas of India during April to June 2018, 2019 and 2020

| Year (April to June) | Status of employment | Total | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P.S | P.S. + S.S | P.S | P.S. + S.S | P.S | P.S. + S.S | ||

| 2018 | Employed | 91.56% | 91.69% | 92.37% | 92.50% | 88.56% | 88.72% |

| Unemployed | 8.44% | 8.31% | 7.63% | 7.50% | 11.44% | 11.28% | |

| 2019 | Employed | 92.91% | 93.11% | 93.55% | 93.78% | 90.53% | 90.65% |

| Unemployed | 7.09% | 6.89% | 6.45% | 6.22% | 9.47% | 9.35% | |

| 2020 | Employed | 91.71% | 91.92% | 92.93% | 93.05% | 87.56% | 88.08% |

| Unemployed | 8.29% | 8.08% | 7.07% | 6.95% | 12.44% | 11.92% | |

Source Unit-level data of PLFS 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20

Table 2 shows the usual status employment rates of urban men and women workers across different types of employment during the months of April to June 2018, 2019 and 2020. It is clear from the table that there has been a slight increase in employment rate in case of both types of self-employment for both male and female workers during the period of our analysis. While there has been a slight increase in rate of unpaid family workers for men, rate of unpaid family women workers increased considerably during this period. While there has been a slight decline in the employment rate of male regular/salaried wage employees, employment rate of female regular/salaried wage employees declined considerably. Employment rate for casual wage labour remained almost the same for urban men, whereas that for urban women decreased considerably.

Usual status (principal and subsidiary) employment rates of men and women (age group of 15–60 years) in urban areas of India across different types of employment during April to June 2018, 2019 and 2020

| Sex | Status of employment | Year (April to June) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (%) | 2019 (%) | 2020 (%) | |||

| Male | Self-employed own account worker | P.S | 26.51 | 26.18 | 27.77 |

| P.S. + S.S | 27.12 | 27.14 | 28.80 | ||

| Self-employed employer | P.S | 2.92 | 3.76 | 2.64 | |

| P.S. + S.S | 2.98 | 3.95 | 2.79 | ||

| Unpaid family worker | P.S | 3.53 | 3.70 | 3.57 | |

| P.S. + S.S | 3.58 | 3.82 | 3.65 | ||

| Female | Self-employed own account worker | P.S | 16.82 | 19.08 | 17.45 |

| P.S. + S.S | 17.36 | 19.80 | 18.25 | ||

| Self-employed employer | P.S | 0.42 | 1.45 | 0.38 | |

| P.S. + S.S | 0.46 | 1.58 | 0.38 | ||

| Unpaid family worker | P.S | 8.10 | 8.00 | 9.52 | |

| P.S. + S.S | 8.11 | 8.17 | 9.69 | ||

| Male | Regular/salaried wage employee | P.S | 44.49 | 43.89 | 43.68 |

| P.S. + S.S | 44.90 | 44.59 | 44.33 | ||

| Female | Regular/salaried wage employee | P.S | 50.11 | 50.30 | 48.93 |

| P.S. + S.S | 50.63 | 50.86 | 48.21 | ||

| Male | Casual wage labour in public works | P.S | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| P.S. + S.S | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.08 | ||

| Female | Casual wage labour in public works | P.S | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.57 |

| P.S. + S.S | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.60 | ||

| Male | Casual wage labour in other types of work | P.S | 13.24 | 13.40 | 12.75 |

| P.S. + S.S | 13.73 | 13.86 | 13.28 | ||

| Female | Casual wage labour in other types of work | P.S | 10.55 | 8.69 | 9.18 |

| P.S. + S.S | 11.27 | 9.40 | 9.71 | ||

Source Unit-level data of PLFS 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019=20

Table 3 illustrates the estimates of mean monthly earning of urban male and female workers during the months of April to June of three successive years 2018, 2019 and 2020 according to the types of employment in urban areas of India.

Mean monthly earning (Rs.) (constant price, base: 2012 = 100 for urban areas) of urban male and female workers according to types of employment during April to June of 2018, 2019 and 2020

| Year (April to June) | Self-employed | Regular wage/salary | Casual labour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 2018 | 4483.70 | 1593.42 | 15,445.39 | 13,138.95 | 3386.58 | 1277.27 |

| 2019 | 4928.27 | 1274.22 | 18,466.48 | 16,665.56 | 3418.43 | 1294.05 |

| 2020 | 4389.86 | 1546.97 | 16,844.64 | 13,733.71 | 1730.77 | 727.11 |

Table 3 indicates the mean values of monthly earning of urban male and female workers during April to June of three successive years 2018, 2019 and 2020 according to types of employment in India.

Monthly earnings of usual status regular/salaried wage employees and self-employed people are available in unit-level data of PLFS 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20. Daily wages and hours of work of casual labourers are given in current weekly status. We have calculated hourly wages, then converted them to daily wages assuming eight hours of work per day and calculated monthly wages from the daily wages of casual labourers. We have finally calculated mean monthly earning for each type of workers.

The table suggests that although mean monthly earning of both urban male and urban female workers declined during the first three months of the outbreak of pandemic, it is clearly evident that throughout the whole period, mean monthly earning of urban female workers was much lower than that of urban male workers for all the categories of urban employment, and mean monthly earning of urban self-employed and casual labourers were much lower than that of urban regular/salaried labourers in India.

Analysing the data of Tables 2 , ,3, 3 , we observed that although employment rate of urban male workers slightly increased in self-employment casual labour and slightly declined in regular/salaried employment, urban female workers suffered considerable job losses in regular/salaried employment and casual labour, and employment rate increased only marginally in self-employment. During this period, urban women workers were either concentrated in unpaid family works or they were completely unemployed. In all types of jobs, both urban male and female workers experienced considerable decline in mean earnings and decline in income of female workers was higher compared to their male counterparts.

Estimating Mincerian Wage Equation: Methodological Issues

A more flexible way to investigate the exact reasons behind the decline in monthly earnings of urban workers is to estimate a Mincerian wage regression model with education and work experience as explanatory variables (Mincer 1974 ). By following Mincer ( 1974 ), we have constructed our wage equation in the frame of the pooled unit-level data taken from PLFS of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 (schedule 10.4) conducted by the NSSO. (The detailed construction of the wage equation is shown in Eq. ( 1 ) in Appendix.)

A complicated statistical problem will arise in estimating the wage equation with household-level information provided by the NSSO because some households within the sample and some members within a household receive no wage income. If we carry out empirical estimation by ignoring the households with no earning in the form of wage, the sample becomes non-random or incidentally truncated and the problem of sample selection bias will arise. Heckman ( 1976 , 1979 ) proposed two estimation techniques to overcome the selection bias problem. First is the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation of a selection model assuming bivariate normality of the error terms in the wage and participation equations. Second is the two-step estimation (Heckit) procedure, ML probit estimation of the participation equation and ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation of the wage equation using participants only and the normal hazard (the inverse Mills ratio ‘ λ ’) 3 estimated from the first step as additional regressor. In this study, the Heckit method is used in estimating the variations in earning of urban workers. The equation used for correcting sample selection bias is specified in Eq. ( 2 ) in the Appendix.

Empirical Results

In the pooled sample used in this study, we have excluded children up to the age of 15 and the elderly above 60 years. We have calculated all percentage shares by using sampling weights constructed from the multiplier by following the norms provided in NSS schedules to get the corresponding values for the population. As the earning for non-working people is unobserved, we need to estimate a probit model for labour force participation to test and correct for sample selection bias. The estimated results are shown in Table 4 .

Probit estimates of labour force participation

| Variables | Coefficients | z | P > z |

|---|---|---|---|

| constant | 2.214395 | 19.51 | 0.000 |

| year_2020 | − 1.207961 | − 33.4 | 0.000 |

| hhd_size | − 0.0854601 | − 15.41 | 0.000 |

| age | 0.0129339 | 10.26 | 0.000 |

| female | − 0.0332896 | − 5.48 | 0.000 |

| sc | 0.0197346 | 0.34 | 0.736 |

| obc | − 0.1995261 | − 4 | 0.000 |

| general_caste | − 0.2387244 | − 4.75 | 0.000 |

| primary | 0.1650262 | 2.57 | 0.010 |

| middle | − 0.1222663 | − 2.17 | 0.030 |

| secondary | − 0.0341476 | − 0.58 | 0.563 |

| higher_secondary | − 0.0137552 | − 0.22 | 0.823 |

| graduate | 0.1549805 | 2.59 | 0.010 |

| post_graduate | 0.3673821 | 5 | 0.000 |

| no_tech | − 0.0944428 | − 1.55 | 0.000 |

| regular_wage | − 0.9467423 | − 4 | 0.000 |

| self_employed | 1.315003 | 5.9 | 0.000 |

| regular_wage_2020 | − 1.230869 | − 4.9 | 0.000 |

| self_employed_2020 | − 2.295002 | − 10.05 | 0.000 |

| Inverse Mills ratio (lambda) | − 0.2292307 | − 3.57 | 0.000 |

| rho | − 0.35451 | ||

| sigma | 0.64661909 | ||

Source: Unit-level data of PLFS 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20

The estimated value of the inverse Mills ratio ( λ ) as shown in the Table 4 is statistically significant implying the presence of selection bias. Thus, the earning equation is to be estimated after correcting for sample selection bias.

The empirical results are presented in Table 4 . Dummy variable for year 2020 had negative and highly significant coefficient which implies that labour force participation of the urban workers had declined significantly during the months April to June of 2020. Household size had a highly significant negative effect on labour force participation. The larger the family size, the lower was the chance to participate in wage employment. A household with large family size was likely to engage in unpaid family work and self-employment activities, both on the farm and on the non-farm sectors. Age is positive and highly significant coefficient, which implies that with the increase in age, probability of joining the labour market increased significantly throughout the whole period of our analysis. The dummy variable female had negative and highly significant coefficient which implies that if a worker was female in the urban area, probability of participating in the labour market declined significantly. This is perfectly understandable since the labour market is highly imperfect in India and labour force participation rate of female workers would obviously be significantly lower than that of male workers in the urban areas.

Probability of participation in labour market was not significantly higher for scheduled castes, compared to that of scheduled tribes. However, probability of participation declined if the worker was from other backward castes and general castes compared to that of scheduled tribes. Urban people who had primary education had higher probability of participating the labour market compared to the illiterate urban people during the period of our analysis. However, probability of participation in the job market declined in case of people with middle level of general education. Probability of participation in labour market was not significantly different for people having secondary and higher secondary level of education compared to that of people who were illiterates. However, probability of joining the labour market significantly increased for those who had graduate or postgraduate level of education compared to those who were illiterate in the urban areas of India. Probability of participation in the labour market was significantly lower in case of urban people who had no technical education during the period of our analysis. Probability of participation in regular wage jobs was significantly lower than that in casual works. However, probability of participation in self-employment was significantly higher than that in casual works. We further observed that probability of participating in the labour market declined significantly for the people engaged in self-employment and regular/salaried employment in the urban areas during the months of April to June of 2020. This result portrays the crisis in the urban employment market during the outbreak of pandemic in India.

The estimated results of the wage equation specified in Eq. ( 1 ) by OLS using participants in the labour market only and the normal hazard (the inverse Mills ratio) estimated from the first step as additional regressor are shown in Table 5 .

Sample selection bias corrected OLS estimates of the earning equation

| Variables | Coefficients | z | P > z |

|---|---|---|---|

| constant | 7.880818 | 114.81 | 0.000 |

| year_2020 | − 0.149999 | − 2.69 | 0.000 |

| female | − 0.374928 | − 31.58 | 0.000 |

| primary | 0.1570956 | 7.14 | 0.000 |

| middle | 0.2701324 | 14.29 | 0.000 |

| secondary | 0.3614685 | 17.99 | 0.000 |

| higher_secondary | 0.4998619 | 23.42 | 0.000 |

| diploma_certificate | 0.7330315 | 17.71 | 0.000 |

| graduate | 0.8580233 | 41.77 | 0.000 |

| post_graduate | 1.098739 | 46.01 | 0.000 |

| engineering_degree | 0.3735961 | 11.33 | 0.000 |

| medicine_degree | 0.5266938 | 7.97 | 0.000 |

| agriculture_diploma_below_graduate | 0.4651131 | 2.46 | 0.014 |

| engineering_diploma_below_graduate | 0.1018215 | 2.32 | 0.020 |

| medicine_diploma_below_graduate | 0.2047893 | 2.4 | 0.016 |

| agriculture_diploma_graduate_above | 0.4225282 | 2.36 | 0.018 |

| engineering_diploma_below_graduate | 0.3567818 | 6.47 | 0.000 |

| medicine_diploma_below_graduate | 0.4557399 | 4.61 | 0.000 |

| age | 0.048971 | 16.73 | 0.000 |

| agesq | − 0.0003853 | − 10.3 | 0.000 |

| regular_wage | 0.2208679 | 5.92 | 0.000 |

| self_employed | 0.1071807 | 2.72 | 0.006 |

| regular_wage_2020 | − 0.0033544 | − 0.06 | 0.952 |

| self_employed_2020 | − 0.278725 | − 4.8 | 0.000 |

Table 5 shows the results of sample selection bias corrected OLS regression of the earning equation. We have used monthly earnings of the urban workers in rupees at constant prices (Base: 2012 = 100 for urban areas) as the dependent variable. The negative and highly significant coefficient of the year_2020 dummy variable indicates that monthly earning of urban workers declined significantly during the period of April-June 2020. The female dummy variable has negative and highly significant coefficient which implies that if the worker was female, she got lower wage compared to her male counterpart in the urban areas of India. People having general education levels like primary, middle, secondary, higher secondary, diploma or certificate course, graduate and postgraduate had significantly higher earnings compared to illiterate people in the urban areas of India during the whole period of our analysis. People having less than graduate or graduate or postgraduate technical degrees or diplomas in agriculture, engineering, medicine and other subjects had significantly higher earnings compared to those who had no technical education. People with higher experience had significantly higher wages compared to those having lower experience. Wages increased at a decreasing rate with the increase in age or experience in the urban areas of India during the period of our study. People who were engaged in regular/salaried employment and self-employment had significantly higher earnings than those who were working as casual labourers during the whole period of our analysis. During April to June of 2020, i.e. during the period of the outbreak of pandemic, earnings of workers engaged in self-employment and regular/salaried employment declined significantly.

Conclusions

This study analyses the possible reasons behind decline in monthly earnings and labour market participation of urban people in India during the period of outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, i.e. during the period from April 2020 to June 2020. Since the lockdown for outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic was announced during the last week of March 2020, the unit-level data of the last quarter of PLFS 2019-20 show the situation of labour market in the urban areas of India during the outbreak of the pandemic. Since dataset of urban workers is rotational panel data in each PLFS, full data of quarter 1, quarter 2 and quarter 3 are not comparable with the full data of quarter 4. Furthermore, employment in India is predominantly informal sector employment, which suffers from seasonal effect. Therefore, we have decided to compare data of fourth quarter from each of the PLFSs of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 (schedule 10.4) since they have identical seasonal conditions. The whole analysis is divided into three similar periods: April to June 2018, April to June 2019 and April to June 2020. We have used unit-level data of PLFS of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 published by NSSO India. Since all the persons did not participate in the labour market, we have used Heckman’s two-stage classification model in order to remove the sample selection bias in our analysis.

Firstly, we have used the cross-tabulation method in order to estimate usual status employment and unemployment rates of men and women in urban areas of India segregated into fourth quarters of PLFS 2017=18, 2018-19 and 2019=20. It is clear from our estimates that unemployment rate declined for both urban men and women from the period from April to June of 2018 to that of 2019, although it increased once again for both during the same months of 2020. It is also clear that usual status unemployment rates of urban women have been much higher compared to those of urban men throughout the whole period of our analysis.

We have also calculated usual status employment rates of urban men and women workers across different types of employment during April to June of 2018, 2019 and 2020. It is clear from the figures that while there has been a slight increase in self-employment for both urban male and female workers and slight decrease in regular salaried employment for urban male workers, there has been a considerable decrease in regular/salaried employment for urban female workers during the initial three pandemic months. It is also observed that there has been a considerable increase in participation of urban female workers in unpaid family work during the pandemic months. It is also clear that employment rate for casual wage labour remained almost the same for urban men, whereas that for urban women decreased considerably during the period of our study. Hence, we can conclude that the outbreak of pandemic affected female workers more severely compared to male workers. There had been a shift from regular employment to self-employment and casual employment for both male and female workers, although female workers were more concentrated in unpaid family work.

We have also estimated mean monthly earnings of urban male and female workers during April to June of three successive years 2018, 2019 and 2020 according to the types of employment in urban areas of India. Our estimated figures show that although mean monthly earning of both urban male and urban female workers declined during the three months of the outbreak of pandemic in 2020, it is clearly evident that throughout the whole period, mean monthly earning of urban female workers was much lower than that of urban male workers for all the categories of urban employment, and mean monthly earnings of urban self-employed and casual labourers were much lower than that of urban regular/salaried labourers in India.

We have also observed that although employment rate of urban self-employment and casual labour increased and that of regular employment declined for both male and female workers during April to June of 2020, mean monthly earning of urban self-employed and casual labourers was much lower than that of urban regular/salaried labourers throughout the whole period and it declined further during the first three months of the outbreak of pandemic. It is also clear that throughout the whole period, mean monthly earning of urban female workers was much lower than that of urban male workers for all the categories of urban employment.

Our empirical results show that labour force participation of the urban workers had declined significantly during the months of April to June 2020. The larger the family size, the lower was the chance to participate in wage employment, maybe because the family members were likely to engage themselves in unpaid family work and self-employment activities, both on the farm and on the non-farm sectors. With the increase in age, probability of joining the labour market increased significantly throughout the whole period of our analysis. Female workers had significantly lower probability of joining the labour market compared to male workers. This is perfectly understandable since the labour market is highly imperfect in India and labour force participation rate of female workers would obviously be significantly lower than that of male workers in the urban areas. There was no significant difference in probabilities of joining the labour market between schedules tribes and scheduled castes. However, probability of participation declined if the worker was from other backward castes and general castes compared to that of scheduled tribes. The reason behind such result may be the caste-based reservation system in regular/salaried jobs and prevalence of low-paid and low-skilled jobs in urban job market which were most typically ‘lower caste jobs’ in India, e.g. the job of sanitation workers.

From our empirical findings, it is clear that urban people who had primary education had higher probability of participating in the labour market compared to the illiterate urban people during the period of our analysis. However, probability of participation in the job market declined in case of people with middle level of general education. Probability of participation in labour market was not significantly different for people having secondary and higher secondary level of education compared to that of people who were illiterates. However, probability of joining the labour market significantly increased for those who had graduate or postgraduate level of education compared to those who were illiterate in the urban areas of India. Probability of participation in the labour market was significantly lower in case of urban people who had no technical education during the period of our analysis. Probability of participation in regular wage jobs was significantly lower than that in casual works. However, probability of participation in self-employment was significantly higher than that in casual works. We further observe that probability of participating in the labour market declined significantly for the people engaged in self-employment and regular/salaried employment in the urban areas during the months of April to June of 2020. This result portrays the crisis in the urban employment market during the outbreak of pandemic in India.

After correcting the sample selection bias using the Heckman’s two-stage classification model, we have estimated the earning equation using OLS regression model. Our empirical results show that monthly earning of urban workers declined significantly during the period of April–June 2020. Urban female workers got significantly lower wage compared to their male counterparts. People having general education levels like primary, middle, secondary, higher secondary, diploma or certificate course, graduate and postgraduate had significantly higher earnings compared to illiterate people in the urban areas of India. Urban people having less than graduate or graduate or postgraduate technical degrees or diplomas in agriculture, engineering, medicine and other subjects had significantly higher earnings compared to those who had no technical education. People with higher experience had significantly higher wages compared to those having lower experience in the urban areas of India. Wages increased at a decreasing rate with the increase in age or experience. Urban people who were engaged in regular/salaried employment and self-employment had significantly higher earnings than those who were working as casual labourers during the whole period of our analysis. During April to June of 2020, i.e. during the period of the outbreak of pandemic, earnings of urban workers engaged in self-employment and regular/salaried employment declined significantly.

Construction of the Wage Equation

By following Mincer ( 1974 ), the wage equation in the frame of unit-level data from the random sample is specified as:

The dependent variable in Eq. ( 1 ) is natural log of monthly earning of the urban workers. Variable year_2020 is a time dummy variable, which is 1 if the time if quarter 4 of 2020 and 0 otherwise. Variable female is used as the gender dummy variable, which is 1 if the worker is female and 0 otherwise. We have incorporated 7 explanatory dummy variables denoting different levels of general education starting from below primary level to postgraduate level and considered illiterates as the yardstick of comparison. We have also included 10 explanatory dummy variables denoting different types of technical education including degrees and diploma/certificate courses and considered workers without any technical education as the benchmark variable. We have taken the age variable as a proxy to experience and also included the age squared variable to find out the rate of change in reward with increase in age. We have taken the dummy variables of regular wage employees and self-employed workers and considered casual labourers as the benchmark variable in order to find out whether there were any differences in earnings across these types of employment during the whole period of our analysis. We have further used interaction dummy variables for these two types of urban employment interacted with year_2020 dummy, i.e. the dummy variable for the first three months of the pandemic period, in order to find out whether there were any changes in earnings for these types of urban employment during the pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period. ε is an i.i.d. idiosyncratic error term with mean zero and constant variance σ ε 2 measuring the effects of unobservable random factors.

Two-Step Estimation (Heckit) Procedure

By following Heckman ( 1979 ), we assume the equation for participating in the labour market as:

w i ∗ is the difference between the market wage and the reservation wage. The reservation wage is the minimum wage at which the i th individual is prepared to work. If the wage is below that level, nobody will choose to work. We do not actually observe w i ∗ . What we can observe is a dichotomous variable w i with a value of 1 if a person enters into the labour market and 0 otherwise.

The wage equation specified in ( 1 ) is relevant only if w i ∗ is positive.

The Heckit procedure is the maximum likelihood probit estimation of the participation equation shown in ( 2 ) to obtain estimates of γ by assuming u i ~ N(0, 1).

In the participation Eq. ( 2 ), we have incorporated variable year_2020 as the dummy variable for the pandemic quarter of 2020, variable female as the gender dummy variable, sc, obc and general caste dummy variables, household size variable, age variable, 6 general education dummy variables, dummy variable for the people with no technical education, dummy variables for two types of urban employment and interaction dummy variables of these two types of urban employment interacted with year_2020. Household size is in the selection equation, but it is not included in the wage equation. We assume that, given the productivity factors, the household size has an influence on the employment decision, but no effect on wage.

There is no financial interest to report. I have not received any fund from any agency to conduct the research work related with this paper. I certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.

Declarations

I have no conflict of interest to declare.

1 Author’s calculations from PLFS 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20.

2 Our figures are not comparable to the figures provided in PLFS Reports of 2017-18, 2018=19 and 2019-20, since all the age groups and all the quarters and visits are included in the calculation of employment and unemployment rates in the reports.

3 Inverse Mills ratio, named after John P. Mills, is the ratio of the probability density function to the cumulative distribution function of a distribution.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Bhalotia, S., Swati Dhingra and Fjolla Kondirol (2020). City of dreams no more: COVID-19 in urban India, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/09/11/city-of-dreams-no-more-covid-19-in-urban-india/

- Heckman J. The Common Structure of Statistical Models of Truncation, Sample Selection, and Limited Dependent Variables and a Simple Estimator of Such Models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement. 1976; 5 :475–492. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heckman J. Sample Selection bias as a Specification Error. Econometrica. 1979; 47 :152–161. doi: 10.2307/1912352. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- IANS. (2021). Unemployment, Covid-19 top most worries for urban Indians: Survey, https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/unemployment-covid-19-top-most-worries-for-urban-indians-survey-121093000163_1.html

- Kumar, O., Shashank Srivastava (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on employment in urban areas, https://prsindia.org/theprsblog/impact-of-covid-19-on-unemployment-in-urban-areas

- Mincer J. Schooling, Experience and Earnings. New York: Columbia University Press; 1974. [ Google Scholar ]

This website uses cookies to ensure the best user experience. Privacy & Cookies Notice Accept Cookies

Manage My Cookies

Manage Cookie Preferences

| NECESSARY COOKIES These cookies are essential to enable the services to provide the requested feature, such as remembering you have logged in. | ALWAYS ACTIVE |

| Accept | Reject | |

| PERFORMANCE AND ANALYTIC COOKIES These cookies are used to collect information on how users interact with Chicago Booth websites allowing us to improve the user experience and optimize our site where needed based on these interactions. All information these cookies collect is aggregated and therefore anonymous. | |

| FUNCTIONAL COOKIES These cookies enable the website to provide enhanced functionality and personalization. They may be set by third-party providers whose services we have added to our pages or by us. | |

| TARGETING OR ADVERTISING COOKIES These cookies collect information about your browsing habits to make advertising relevant to you and your interests. The cookies will remember the website you have visited, and this information is shared with other parties such as advertising technology service providers and advertisers. | |

| SOCIAL MEDIA COOKIES These cookies are used when you share information using a social media sharing button or “like” button on our websites, or you link your account or engage with our content on or through a social media site. The social network will record that you have done this. This information may be linked to targeting/advertising activities. |

Confirm My Selections

- Social Impact Research

- Get Involved

- Rustandy Stories

- Give to the Center

- Sign Up For Rustandy Center Updates

- ESG Data Tool

Employment, Income, and Consumption in India During and After the Lockdown: A V-Shape Recovery?

- By Marianne Bertrand, Rebecca Dizon-Ross, Kaushik Krishnan, and Heather Schofield

- November 18, 2020

- Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation

- Share This Page

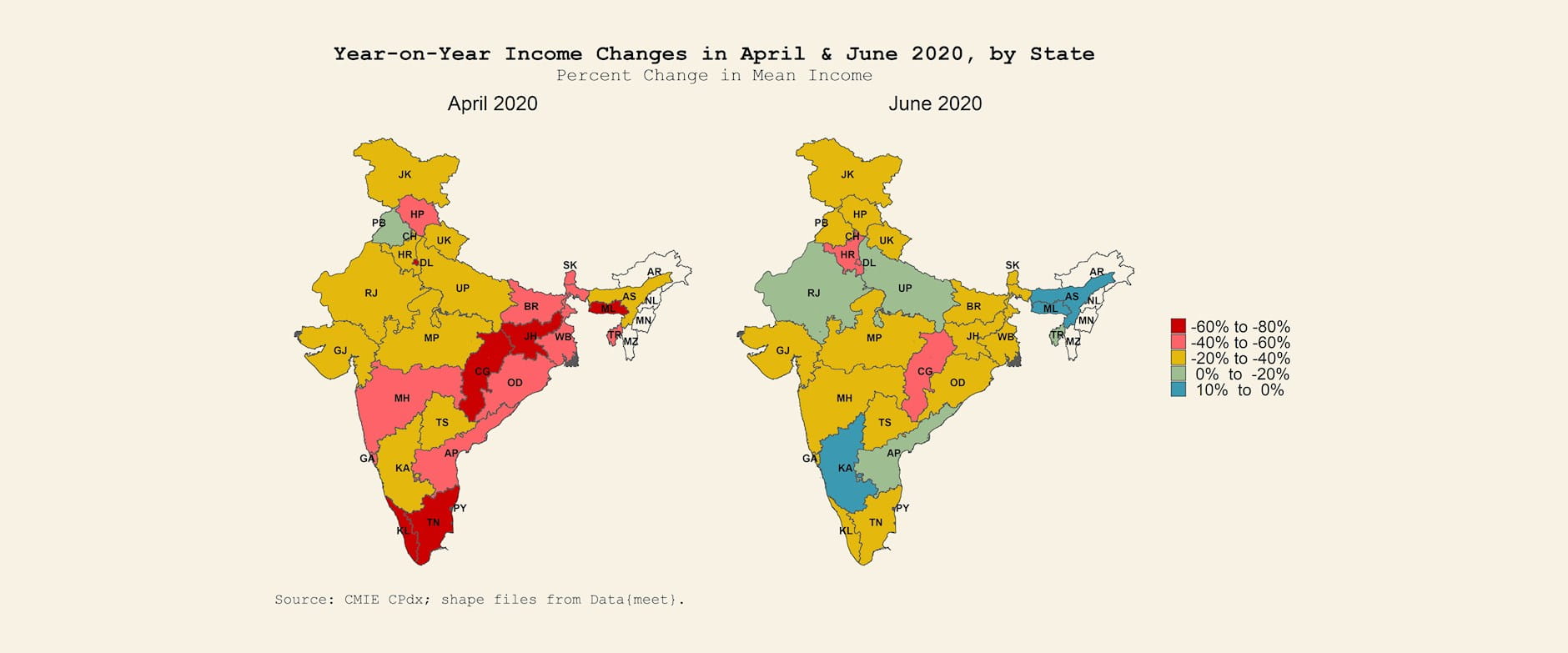

Following a one-day curfew popularly known as the “Janta Curfew” on 22 March 2020, the Government of India ordered a 21-day national lockdown to fight the spread of COVID-19 on 24 March 2020. The lockdown was then extended three times and finally expired on May 31. During this time, most of India’s 1.3 billion residents were required to stop working and shelter indoors, with only a few exceptions. Starting on June 1, and with the exception of containment zones, lockdown restrictions have been relaxed in a phased manner with a focus on easing constraints on economic activity. Some early indicators have pointed towards a V-shape recovery after the lifting of the lockdown.

We document the evolution of unemployment, employment, income and consumption during and after the lockdown. After dramatic setbacks in April and May, all of these time series show rapid improvement immediately after the announcement that lockdown measures would be relaxed. However, they have not all returned to their pre-lockdown levels. There are signs of continued duress for many households, which may foreshadow a slower path to a full recovery.

We analyze data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE)’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS). [1] CPHS is a panel survey that surveys approximately 175,000 households across India every four months. CPHS continued to run through the lockdown with roughly 45 percent of its usual sample, and returned to “normal” survey operations by mid-August. Despite the disruption to surveying imposed by COVID-19 and the lockdown measures, the data collected has remained representative throughout the period. [2]

The Current State of Recovery

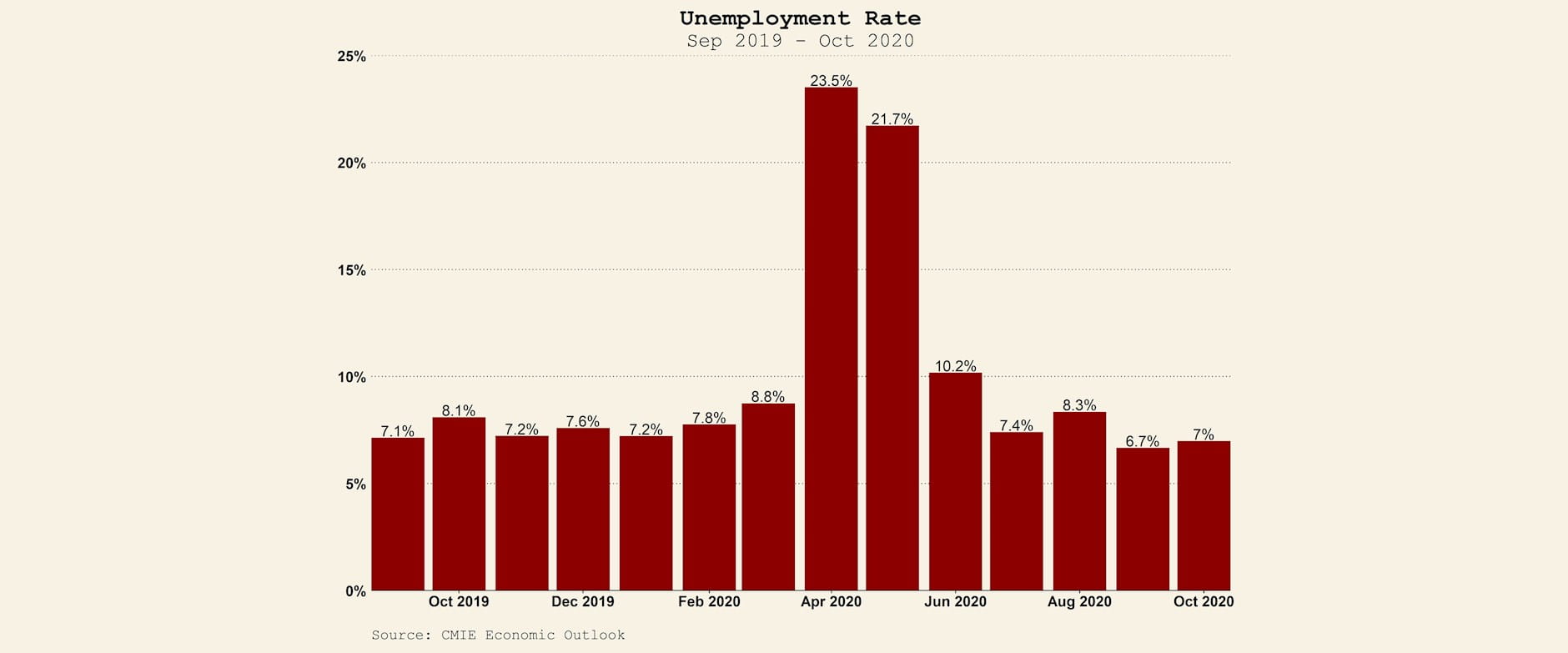

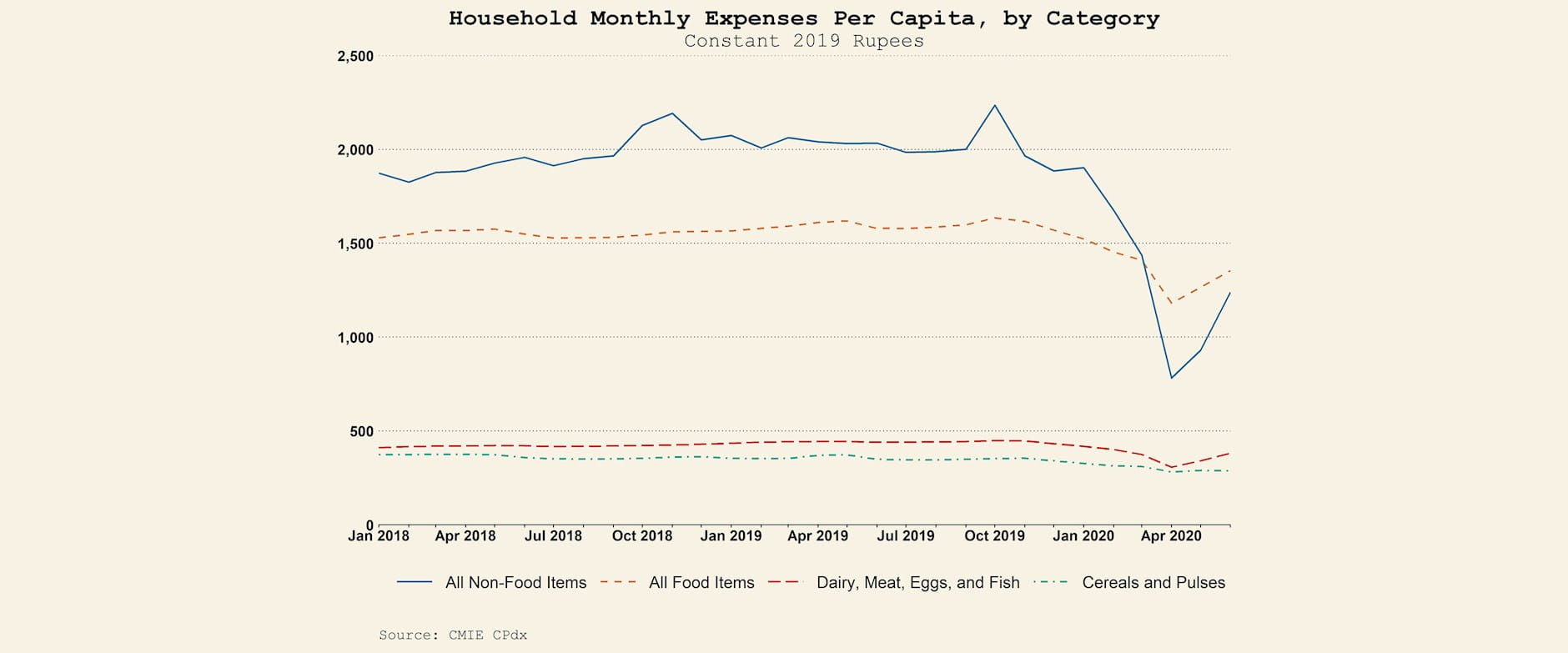

While India recorded a sharp and large drop in GDP during the lockdown — gross domestic product shrank nearly 24 percent in the second quarter of 2020 compared to the second quarter of 2019 [3] — some early indicators have suggested signs of a V-shape recovery. In particular, several commenters have highlighted the year-on-year increase in GST [4] and gross income tax collections revenues. [5] Indian stock markets indexes such as the Nifty50 are higher than they were a year ago. [6] Others have pointed to a very strong kharif season. [7] Industrial activity has also picked up; port traffic, railway freight traffic, and electricity generation have all improved substantially. [8] Core industrial output has almost completely recovered from a 37.9 percent drop in April 2020. [9] Also, and as seen in Figure 1, the unemployment rate, after skyrocketing to nearly 25 percent in April, had largely returned to its pre-lockdown level by June and was fully back to its February level by July, about 7 percent. [10]

FIGURE 1

Yet other sources point to only a partial and incomplete convalescence. For example, most fast frequency indicators with the exception of electricity generation, railway freight traffic and e-way bills fell year-on-year in the September 2020 quarter. [3] After consistent month-on-month increases in the Index of Industrial Production (IIP) since May, this trend reversed in August. [7] The demand for petroleum products has continued to stay far below its 2019 levels. [11] Despite GST collections having grown, net tax collections are still down 14 percent compared to a year ago and the central government’s non-tax revenues are down 60 percent year-on-year. [5] Furthermore, the indicators suggesting a V-shape recovery cannot provide a perfect picture of the ongoing experiences of Indian households. For example, the GST taxes luxury goods more heavily and basic food consumption items (such as flour, fresh fruits, vegetables, meat, fish and milk) are not generally subject to the consumption tax, making GST revenue data a poor proxy of the well-being of the typical Indian household. Also, the unemployment rate calculates employment as a share of the labor force. As such, this statistic may mask discouragement effects, with workers exiting the labor force if they cannot find work. It may also mask exit of the labor force because of health safety concerns. Furthermore, even if most Indians have been able and willing to return to work post-lockdown, available labor market opportunities may have worsened, translating into lower incomes and negative pressures on consumption.

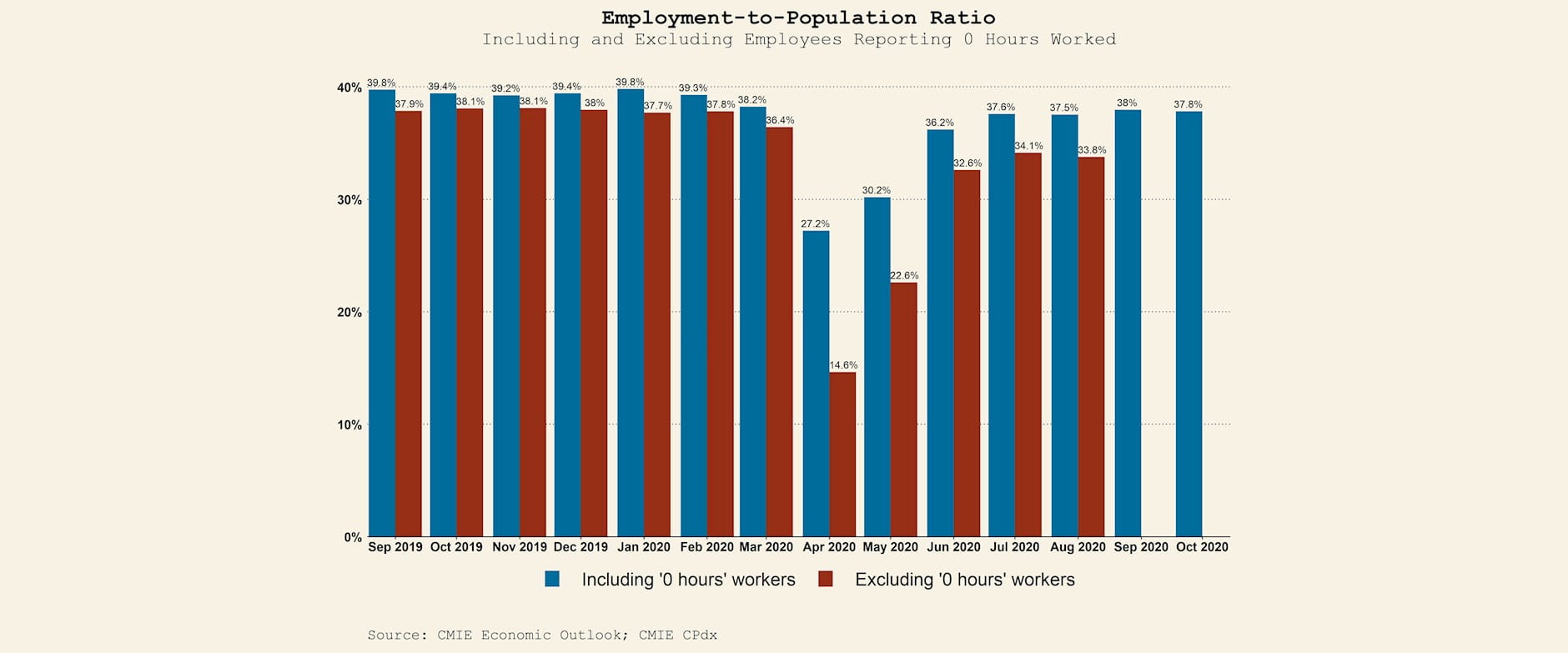

Key Finding #1: The employment to population ratio has not yet returned to its pre-lockdown levels.

Unlike the unemployment rate, the employment to population ratio (which isn’t limited to individuals who report being in the labor force) has not yet fully returned to its pre-lockdown level, as seen in Figure 2. [12] After a collapse in April and May, the employment to population ratio among those 15 years of age or older has hovered around 37 to 38 percent between June and October, from a base of closer to 40 percent pre-lockdown. [13] Furthermore, when we exclude from the numerator individuals who report being employed but simultaneously report working zero hours (which we can measure until August), the decline in the employment to population ratio becomes larger, corresponding to about a 4 percentage point drop, or nearly 10 percent drop, relative to the pre-lockdown period, with no sign of improvement between July and August.

FIGURE 2

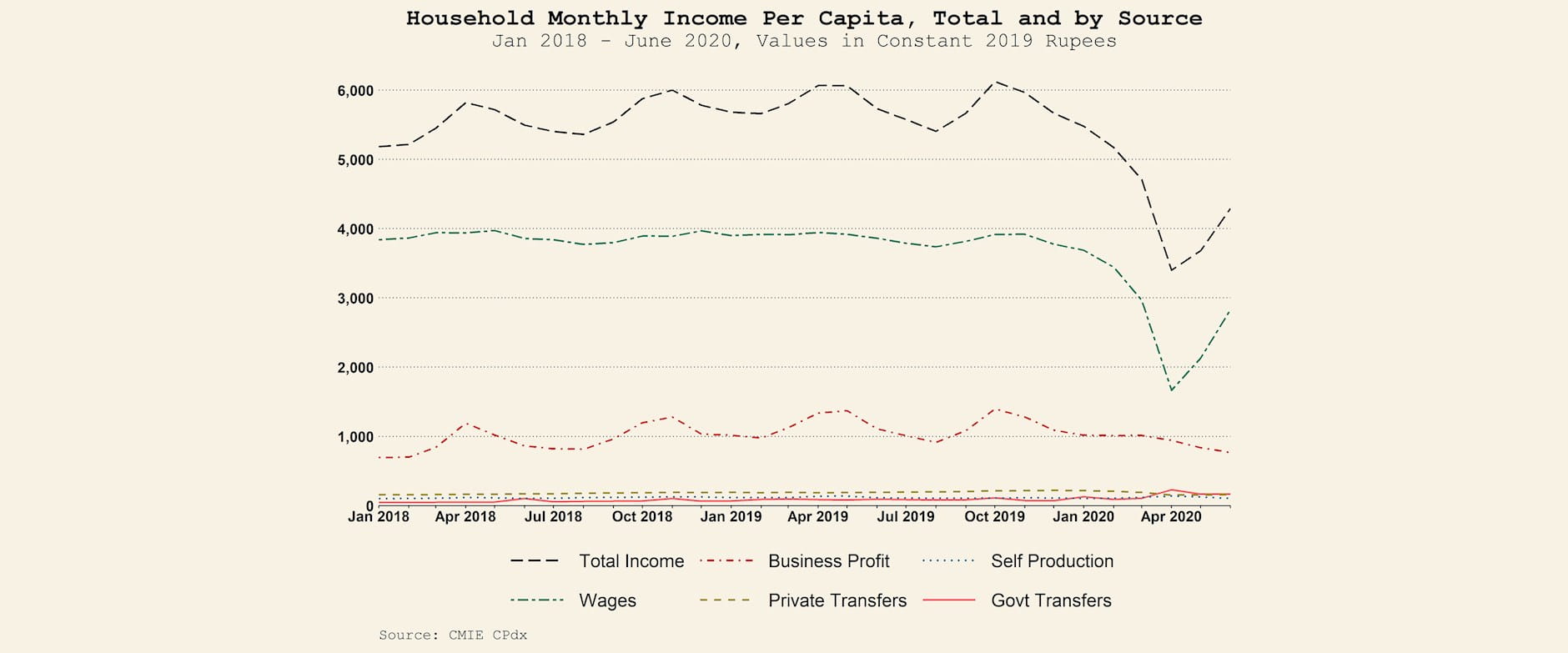

Key Finding #2: Per-capita income levels remained depressed in June.

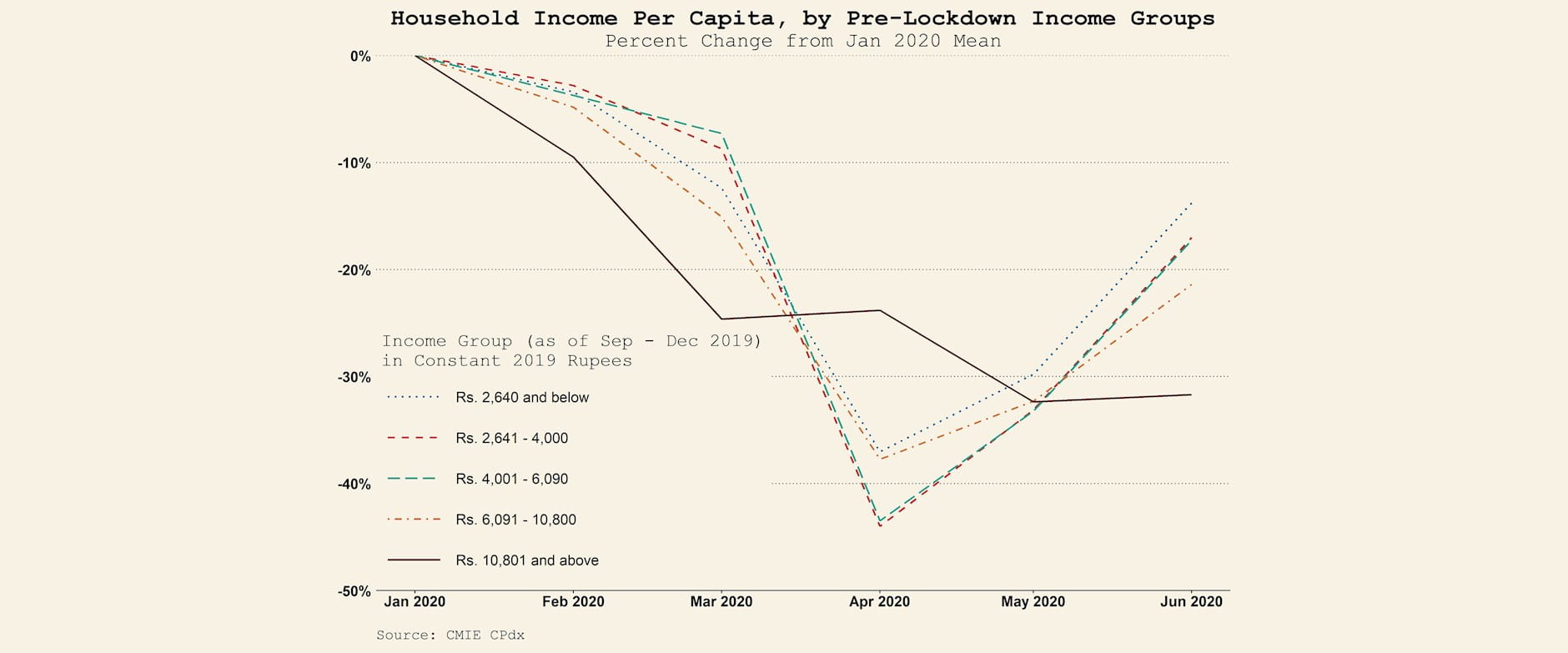

Even a full return to pre-lockdown employment rate levels (which clearly did not happen) could hide sharp differences in the nature of labor market opportunities and other income generating activities after the lockdown measures have been lifted. Individuals may earn less in the same occupation or may have shifted to less remunerative work. Indeed, others have documented a substantial shift from formal to informal employment as a consequence of the lockdown. [14] Figure 3 presents the monthly time series of household per capita income, including disaggregation by source of income, through June (the latest month of data availability). [15] Total income per capita was about 44 percent lower in April 2020 and 39 percent lower in May 2020 compared to the same months in 2019. Despite an uptick when the lockdown eased, per capita total income in June 2020 remained about 25 percent lower than in June 2019. However, this figure may overstate the decline due to lockdown and associated COVID-related disruptions as both total income and labor income were already trending down in the last quarter of 2019 and early months of 2020. This is consistent with a broad downward trend in the economy in early 2020 even before the pandemic and lockdowns. [16] When benchmarked to February 2020, June total (labor) incomes are only 17 (18) percent down.

FIGURE 3

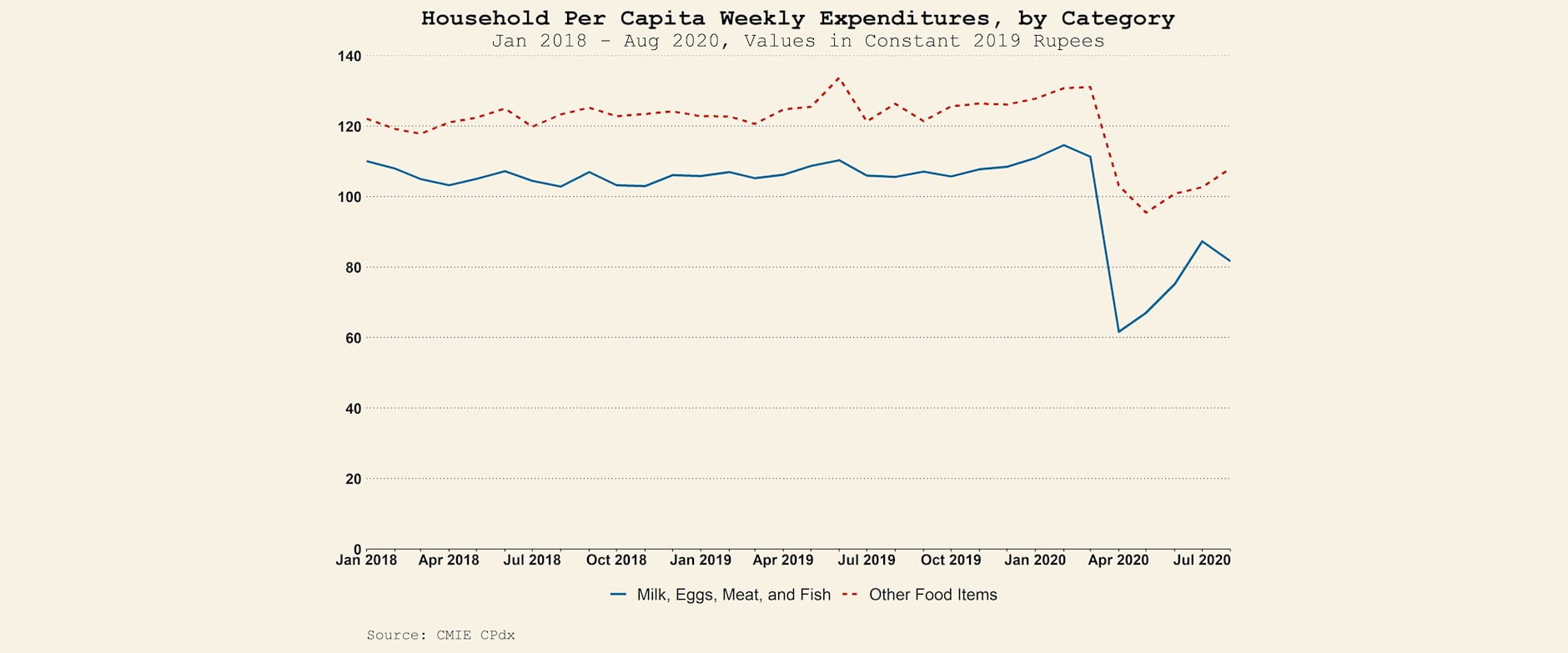

The drop in total income during the lockdown was primarily driven by a sharp drop in labor income, but was supplemented by a decline in business profits. Interestingly, unlike labor income, business income does not show any sign of recovery by June. Rather, business profits remain 24 percent below their level in February 2020 and 31 percent below their level in June 2019. While government assistance via direct benefit transfers increased during the lockdown, these in-cash transfers represent such a small proportion of total income that they played virtually no role in stabilizing income for the average Indian household during the lockdown. This does not rule out that other forms of government support, such as wage income via the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) workfare scheme (which are captured in the wages time series in Figure 3), or in-kind transfers via the Public Distribution System (PDS) (which are not captured in any of the time series in Figure 3), may have helped many households during the lockdown, and continue to stabilize these households post-lockdown.

Key Finding #3: Very few occupations have been spared from the negative income shock.

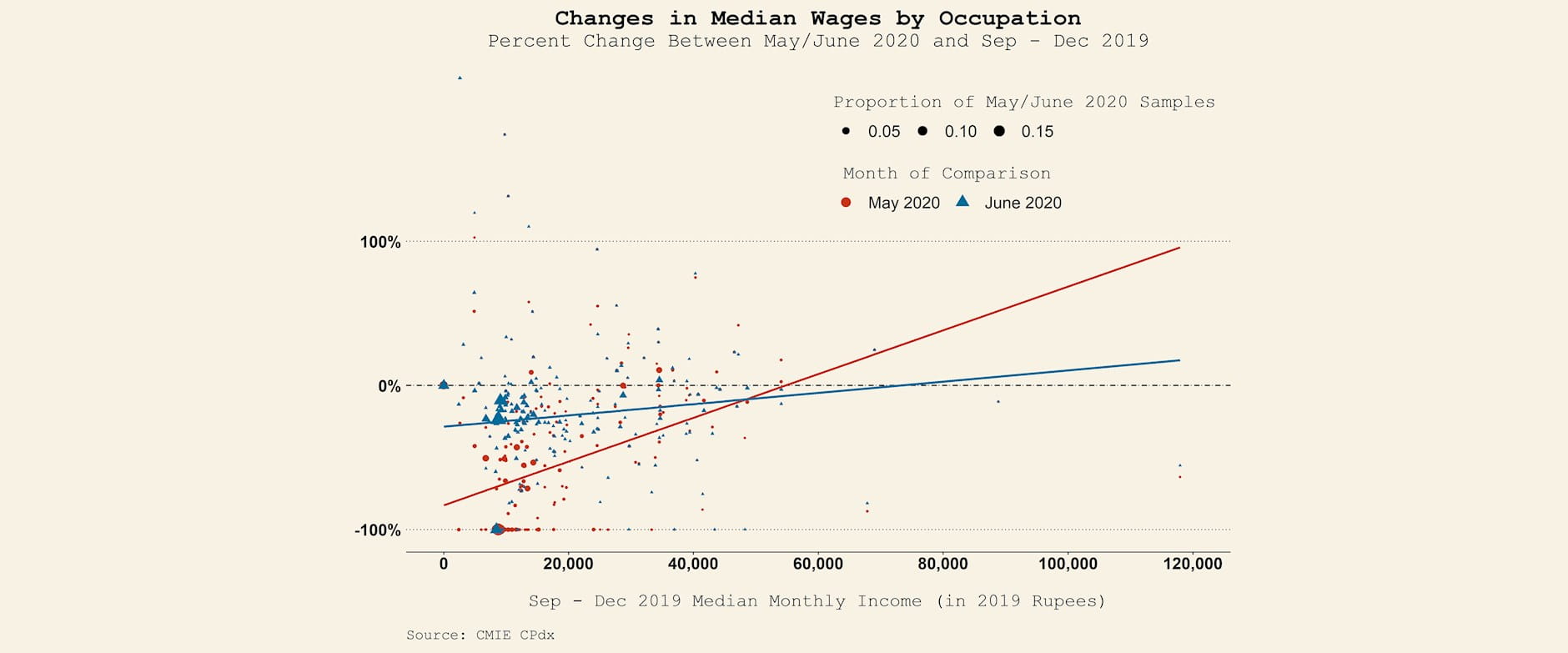

Drops in wage income appear to be widespread across occupations. [17] Figure 4 presents the percent changes in median wages by occupation both during (May, line in red and scatter in circles) and after (June, line in blue and scatter in triangles) the lockdown period. [18] In particular, we relate median wage income among those employed full-time in an occupation pre-COVID (September to December 2019; x-axis) to percent changes in that median income in that occupation, again among those employed full-time, both during (May 2020) and after the lockdown (June 2020). As can be seen below, the vast majority of occupations experienced very large declines in income for the median individual in that occupation during the lockdown. While some substantial recovery had occurred by June, median incomes remained below baseline in about 80 percent of occupations in that month. Considering the 10 largest occupations in terms of employment numbers in June, the largest losses in median income in that month compared to baseline are recorded among subsistence farmers, smaller businessmen (such as shopkeepers or dhaba owners), agricultural laborers, and industrial and machine workers. Regression analyses show that income losses during the lockdown were both economically and statistically larger among lower income occupations, while no such statistical relationship can be detected post-lockdown.

FIGURE 4