Module 11: Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

Case studies: schizophrenia spectrum disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify schizophrenia and psychotic disorders in case studies

Case Study: Bryant

Thirty-five-year-old Bryant was admitted to the hospital because of ritualistic behaviors, depression, and distrust. At the time of admission, prominent ritualistic behaviors and depression misled clinicians to diagnose Bryant with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Shortly after, psychotic symptoms such as disorganized thoughts and delusion of control were noticeable. He told the doctors he has not been receiving any treatment, was not on any substance or medication, and has been experiencing these symptoms for about two weeks. Throughout the course of his treatment, the doctors noticed that he developed a catatonic stupor and a respiratory infection, which was identified by respiratory symptoms, blood tests, and a chest X-ray. To treat the psychotic symptoms, catatonic stupor, and respiratory infection, risperidone, MECT, and ceftriaxone (antibiotic) were administered, and these therapies proved to be dramatically effective. [1]

Case Study: Shanta

Shanta, a 28-year-old female with no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, was sent to the local emergency room after her parents called 911; they were concerned that their daughter had become uncharacteristically irritable and paranoid. The family observed that she had stopped interacting with them and had been spending long periods of time alone in her bedroom. For over a month, she had not attended school at the local community college. Her parents finally made the decision to call the police when she started to threaten them with a knife, and the police took her to the local emergency room for a crisis evaluation.

Following the administration of the medication, she tried to escape from the emergency room, contending that the hospital staff was planning to kill her. She eventually slept and when she awoke, she told the crisis worker that she had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) a month ago. At the time of this ADHD diagnosis, she was started on 30 mg of a stimulant to be taken every morning in order to help her focus and become less stressed over the possibility of poor school performance.

After two weeks, the provider increased her dosage to 60 mg every morning and also started her on dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets (10 mg) that she took daily in the afternoon in order to improve her concentration and ability to study. Shanta claimed that she might have taken up to three dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets over the past three days because she was worried about falling asleep and being unable to adequately prepare for an examination.

Prior to the ADHD diagnosis, the patient had no known psychiatric or substance abuse history. The urine toxicology screen taken upon admission to the emergency department was positive only for amphetamines. There was no family history of psychotic or mood disorders, and she didn’t exhibit any depressive, manic, or hypomanic symptoms.

The stimulant medications were discontinued by the hospital upon admission to the emergency department and the patient was treated with an atypical antipsychotic. She tolerated the medications well, started psychotherapy sessions, and was released five days later. On the day of discharge, there were no delusions or hallucinations reported. She was referred to the local mental health center for aftercare follow-up with a psychiatrist. [2]

Another powerful case study example is that of Elyn R. Saks, the associate dean and Orrin B. Evans professor of law, psychology, and psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California Gould Law School.

Saks began experiencing symptoms of mental illness at eight years old, but she had her first full-blown episode when studying as a Marshall scholar at Oxford University. Another breakdown happened while Saks was a student at Yale Law School, after which she “ended up forcibly restrained and forced to take anti-psychotic medication.” Her scholarly efforts thus include taking a careful look at the destructive impact force and coercion can have on the lives of people with psychiatric illnesses, whether during treatment or perhaps in interactions with police; the Saks Institute, for example, co-hosted a conference examining the urgent problem of how to address excessive use of force in encounters between law enforcement and individuals with mental health challenges.

Saks lives with schizophrenia and has written and spoken about her experiences. She says, “There’s a tremendous need to implode the myths of mental illness, to put a face on it, to show people that a diagnosis does not have to lead to a painful and oblique life.”

In recent years, researchers have begun talking about mental health care in the same way addiction specialists speak of recovery—the lifelong journey of self-treatment and discipline that guides substance abuse programs. The idea remains controversial: managing a severe mental illness is more complicated than simply avoiding certain behaviors. Approaches include “medication (usually), therapy (often), a measure of good luck (always)—and, most of all, the inner strength to manage one’s demons, if not banish them. That strength can come from any number of places…love, forgiveness, faith in God, a lifelong friendship.” Saks says, “We who struggle with these disorders can lead full, happy, productive lives, if we have the right resources.”

You can view the transcript for “A tale of mental illness | Elyn Saks” here (opens in new window) .

- Bai, Y., Yang, X., Zeng, Z., & Yang, H. (2018). A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. BMC psychiatry , 18(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1655-5 ↵

- Henning A, Kurtom M, Espiridion E D (February 23, 2019) A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Cureus 11(2): e4126. doi:10.7759/cureus.4126 ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Wallis Back for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A tale of mental illness . Authored by : Elyn Saks. Provided by : TED. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6CILJA110Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Authored by : Ashley Henning, Muhannad Kurtom, Eduardo D. Espiridion. Provided by : Cureus. Located at : https://www.cureus.com/articles/17024-a-case-study-of-acute-stimulant-induced-psychosis#article-disclosures-acknowledgements . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Elyn Saks. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elyn_Saks . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. Authored by : Yuanhan Bai, Xi Yang, Zhiqiang Zeng, and Haichen Yangcorresponding. Located at : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5851085/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

Schizophrenia case studies: putting theory into practice

This article considers how patients with schizophrenia should be managed when their condition or treatment changes.

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Treatments for schizophrenia are typically recommended by a mental health specialist; however, it is important that pharmacists recognise their role in the management and monitoring of this condition. In ‘ Schizophrenia: recognition and management ’, advice was provided that would help with identifying symptoms of the condition, and determining and monitoring treatment. In this article, hospital and community pharmacy-based case studies provide further context for the management of patients with schizophrenia who have concurrent conditions or factors that could impact their treatment.

Case study 1: A man who suddenly stops smoking

A man aged 35 years* has been admitted to a ward following a serious injury. He has been taking olanzapine 20mg at night for the past three years to treat his schizophrenia, without any problems, and does not take any other medicines. He smokes 25–30 cigarettes per day, but, because of his injury, he is unable to go outside and has opted to be started on nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in the form of a patch.

When speaking to him about his medicines, he appears very drowsy and is barely able to speak. After checking his notes, it is found that the nurses are withholding his morphine because he appears over-sedated. The doctor asks the pharmacist if any of the patient’s prescribed therapies could be causing these symptoms.

What could be the cause?

Smoking is known to increase the metabolism of several antipsychotics, including olanzapine, haloperidol and clozapine. This increase is linked to a chemical found in cigarettes, but not nicotine itself. Tobacco smoke contains aromatic hydrocarbons that are inducers of CYP1A2, which are involved in the metabolism of several medicines [1] , [2] , [3] . Therefore, smoking cessation and starting NRT leads to a reduction in clearance of the patient’s olanzapine, leading to increased plasma levels of the antipsychotic olanzapine and potentially more adverse effects — sedation in this case.

Patients who want to stop, or who inadvertently stop, smoking while taking antipsychotics should be monitored for signs of increased adverse effects (e.g. extrapyramidal side effects, weight gain or confusion). Patients who take clozapine and who wish to stop smoking should be referred to their mental health team for review as clozapine levels can increase significantly when smoking is stopped [3] , [4] .

For this patient, olanzapine is reduced to 15mg at night; consequently, he seems much brighter and more responsive. After a period on the ward, he has successfully been treated for his injury and is ready to go home. The doctor has asked for him to be supplied with olanzapine 15mg for discharge along with his NRT.

What should be considered prior to discharge?

It is important to discuss with the patient why his dose was changed during his stay in hospital and to ask whether he intends to start smoking again or to continue with his NRT. Explain to him that if he wants to begin, or is at risk of, smoking again, his olanzapine levels may be impacted and he may be at risk of becoming unwell. It is necessary to warn him of the risk to his current therapy and to speak to his pharmacist or mental health team if he does decide to start smoking again. In addition, this should be used as an opportunity to reinforce the general risks of smoking to the patient and to encourage him to remain smoke-free.

It is also important to speak to the patient’s community team (e.g. doctors, nurses), who specialise in caring for patients with mental health disorders, about why the olanzapine dose was reduced during his stay, so that they can then monitor him in case he does begin smoking again.

Case 2: A woman with constipation

A woman aged 40 years* presents at the pharmacy. The pharmacist recognises her as she often comes in to collect medicine for her family. They are aware that she has a history of schizophrenia and that she was started on clozapine three months ago. She receives this from her mental health team on a weekly basis.

She has visited the pharmacy to discuss constipation that she is experiencing. She has noticed that since she was started on clozapine, her bowel movements have become less frequent. She is concerned as she is currently only able to go to the toilet about once per week. She explains that she feels uncomfortable and sick, and although she has been trying to change her diet to include more fibre, it does not seem to be helping. The patient asks for advice on a suitable laxative.

What needs to be considered?

Constipation is a very common side effect of clozapine . However, it has the potential to become serious and, in rare cases, even fatal [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] . While minor constipation can be managed using over-the-counter medicines (e.g. stimulant laxatives, such as senna, are normally recommended first-line with stool softeners, such as docusate, or osmotic laxatives, such as lactulose, as an alternative choice), severe constipation should be checked by a doctor to ensure there is no serious bowel obstruction as this can lead to paralytic ileus, which can be fatal [9] . Symptoms indicative of severe constipation include: no improvement or bowel movement following laxative use, fever, stomach pain, vomiting, loss of appetite and/or diarrhoea, which can be a sign of faecal impaction overflow.

As the patient has been experiencing this for some time and is only opening her bowels once per week, as well as having other symptoms (i.e. feeling uncomfortable and sick), she should be advised to see her GP as soon as possible.

The patient returns to the pharmacy again a few weeks later to collect a prescription for a member of their family and thanks the pharmacist for their advice. The patient was prescribed a laxative that has led to resolution of symptoms and she explains that she is feeling much better. Although she has a repeat prescription for lactulose 15ml twice per day, she says she is not sure whether she needs to continue to take it as she feels better.

What advice should be provided?

As she has already had an episode of constipation, despite dietary changes, it would be best for the patient to continue with the lactulose at the same dose (i.e. 15ml twice daily), to prevent the problem occurring again. Explain to the patient that as constipation is a common side effect of clozapine, it is reasonable for her to take laxatives before she gets constipation to prevent complications.

Pharmacists should encourage any patient who has previously had constipation to continue taking prescribed laxatives and explain why this is important. Pharmacists should also continue to ask patients about their bowel habits to help pick up any constipation that may be returning. Where pharmacists identify patients who have had problems with constipation prior to starting clozapine, they can recommend the use of a prophylactic laxative such as lactulose.

Case 3: A mother is concerned for her son who is talking to someone who is not there

A woman has been visiting the pharmacy for the past 3 months to collect a prescription for her son, aged 17 years*. In the past, the patient has collected his own medicine. Today the patient has presented with his mother; he looks dishevelled, preoccupied and does not speak to anyone in the pharmacy.

His mother beckons you to the side and expresses her concern for her son, explaining that she often hears him talking to someone who is not there. She adds that he is spending a lot of time in his room by himself and has accused her of tampering with his things. She is not sure what she should do and asks for advice.

What action can the pharmacist take?

It is important to reassure the mother that there is help available to review her son and identify if there are any problems that he is experiencing, but explain it is difficult to say at this point what he may be experiencing. Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness which has several symptoms that are classified as positive (e.g. hallucinations and delusions), negative (e.g. social withdrawal, self-neglect) and cognitive (e.g. poor memory and attention).

Many patients who go on to be diagnosed with schizophrenia will experience a prodromal period before schizophrenia is diagnosed. This may be a period where negative symptoms dominate and patients may become isolated and withdrawn. These symptoms can be confused with depression, particularly in younger people, though depression and anxiety disorders themselves may be prominent and treatment for these may also be needed. In this case, the patient’s mother is describing potential psychotic symptoms and it would be best for her son to be assessed. She should be encouraged to take her son to the GP for an assessment; however, if she is unable to do so, she can talk to the GP herself. It is usually the role of the doctor to refer patients for an assessment and to ensure that any other medical problems are assessed.

Three months later, the patient comes into the pharmacy and seems to be much more like his usual self, having been started on an antipsychotic. He collects his prescription for risperidone and mentions that he is very worried about his weight, which has increased since he started taking the newly prescribed tablets. Although he does not keep track of his weight, he has noticed a physical change and that some of his clothes no longer fit him.

What advice can the pharmacist provide?

Weight gain is common with many antipsychotics [10] . Risperidone is usually associated with a moderate chance of weight gain, which can occur early on in treatment [6] , [11] , [12] . As such, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends weekly monitoring of weight initially [13] . As well as weight gain, risperidone can be associated with an increased risk of diabetes and dyslipidaemia, which must also be monitored [6] , [11] , [12] . For example, the lipid profile and glucose should be assessed at 12 weeks, 6 months and then annually [12] .

The pharmacist should encourage the patient to attend any appointments for monitoring, which may be provided by his GP or mental health team, and to speak to his mental health team about his weight gain. If he agrees, the pharmacist could inform the patient’s mental health team of his weight gain and concerns on his behalf. It is important to tackle weight gain early on in treatment, as weight loss can be difficult to achieve, even if the medicine is changed.

The pharmacist should provide the patient with advice on healthy eating (e.g. eating a balanced diet with at least five fruit and vegetables per day) and exercising regularly (e.g. doing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week), and direct him to locally available services. The pharmacist can record the adverse effect on the patient’s medical record, which will help flag this in the future and thus help other pharmacists to intervene should he be prescribed risperidone again.

*All case studies are fictional.

Useful resources

- Mind — Schizophrenia

- Rethink Mental Illness — Schizophrenia

- Mental Health Foundation — Schizophrenia

- Royal College of Psychiatrists — Schizophrenia

- NICE guidance [CG178] — Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management

- NICE guidance [CG155] — Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management

- British Association for Psychopharmacology — Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology

About the author

Nicola Greenhalgh is lead pharmacist, Mental Health Services, North East London NHS Foundation Trust

[1] Chiu CC, Lu ML, Huang MC & Chen KP. Heavy smoking, reduced olanzapine levels, and treatment effects: a case report. Ther Drug Monit 2004;26(5):579–581. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200410000-00018

[2] de Leon J. Psychopharmacology: atypical antipsychotic dosing: the effect of smoking and caffeine. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55(5):491–493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.491

[3] Mayerova M, Ustohal L, Jarkovsky J et al . Influence of dose, gender, and cigarette smoking on clozapine plasma concentrations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018;14:1535–1543. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S163839

[4] Ashir M & Petterson L. Smoking bans and clozapine levels. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2008;14(5):398–399. doi: 10.1192/apt.14.5.398b

[5] Young CR, Bowers MB & Mazure CM. Management of the adverse effects of clozapine. Schizophr Bull 1998;24(3):381–390. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033333

[6] Taylor D, Barnes TRE & Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry . 13th edn. London: Wiley Blackwell; 2018

[7] Oke V, Schmidt F, Bhattarai B et al . Unrecognized clozapine-related constipation leading to fatal intra-abdominal sepsis — a case report. Int Med Case Rep J 2015;8:189–192. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S86716

[8] Hibbard KR, Propst A, Frank DE & Wyse J. Fatalities associated with clozapine-related constipation and bowel obstruction: a literature review and two case reports. Psychosomatics 2009;50(4):416–419. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.416

[9] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Clozapine: reminder of potentially fatal risk of intestinal obstruction, faecal impaction, and paralytic ileus. 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/clozapine-reminder-of-potentially-fatal-risk-of-intestinal-obstruction-faecal-impaction-and-paralytic-ileus (accessed April 2020)

[10] Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382(9896):951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3

[11] Bazire S. Psychotropic Drug Directory . Norwich: Lloyd-Reinhold Communications LLP; 2018

[12] Cooper SJ & Reynolds GP. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol 2016;30(8):717–748. doi: 10.1177/0269881116645254

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 (accessed April 2020)

You might also be interested in…

Boots UK shuts online mental health service to new patients

Eating disorders: identification, treatment and support

Mental health considerations in older women

- Dermatology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

- Gynecology and Obstetrics

- Heart and Vascular

- Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

- Pediatric Specialties

- Pediatric Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Pediatrics Florida

- Pediatric Gastroenterology and GI Surgery

- Pediatric Heart

- Pediatrics Maryland/DC

- Pediatric Neurology & Neurosurgery

- Pediatric Orthopaedics

- Physician Affiliations

- Health Care Technology

- High-Value Health Care

- Clinical Research Advancements

- Precision Medicine Excellence

- Patient Safety

Case Study Illustrates How Schizophrenia Can Often Be Overdiagnosed

Share Fast Facts

Study shows how schizophrenia can often be over diagnosed. Learn how. Click to Tweet

Study author Russell Margolis, director of the Johns Hopkins Schizophrenia Center, answers questions on misdiagnosis of the condition and reiterates the importance of thorough examination.

It’s not uncommon for an adolescent or young adult who reports hearing voices or seeing things to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, but using these reports alone can contribute to the disease being overdiagnosed, says Russell Margolis , clinical director of the Johns Hopkins Schizophrenia Center.

Many clinicians consider hallucinations as the sine qua non, or essential condition, of schizophrenia, he says. But even a true hallucination might be part of any number of disorders — or even within the range of normal. To diagnose a patient properly, he says, “There’s no substitute for taking time with patients and others who know them well. Trying to [diagnose] this in a compressed, shortcut kind of way leads to error.”

A case study he shared recently in the Journal of Psychiatric Practice illustrates the problem. Margolis, along with colleagues Krista Baker, schizophrenia supervisor at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, visiting resident Bianca Camerini, and Brazilian psychiatrist Ary Gadelha, described a 16-year-old girl who was referred to the Early Psychosis Intervention Clinic at Johns Hopkins Bayview for a second opinion concerning the diagnosis and treatment of suspected schizophrenia.

The patient made friends easily but had some academic difficulties. Returning to school in eighth grade after a period of home schooling, she was bullied, sexually groped and received texted death threats. She then began to complain of visions of a boy who harassed her, as well as three tall demons. The visions waxed and waned in relation to stress at school. The Johns Hopkins consultants determined that this girl did not have schizophrenia (or any other psychotic disorder), but that she had anxiety. They recommended psychotherapy and viewing herself as a healthy, competent person, instead of a sick one. A year later, the girl reported doing well: She was off medications and no longer complained of these visions.

Margolis answers Hopkins Brain Wise ’s questions.

Q: How are anxiety disorders mistaken for schizophrenia?

A: Patients often say they have hallucinations, but that doesn’t always mean they’re experiencing a true hallucination. What they may mean is that they have very vivid, distressing thoughts — in part because hallucinations have become a common way of talking about distress, and partly because they may have no other vocabulary with which to describe their experience.

Then, even if it is a true hallucination, there are features of the way psychiatry has come to be practiced that cause difficulties. Electronic medical records are often designed with questionnaires that have yes or no answers. Sometimes, whether the patient has hallucinations is murky, or possible — not yes or no. Also, one can’t make a diagnosis based just on a hallucination; the diagnosis of disorders like schizophrenia is based on a constellation of symptoms.

Q: How often are patients in this age range misdiagnosed?

A: There’s no true way to know the numbers. Among a very select group of people in our consultation clinic where questions have been raised, about half who were referred to us and said to have schizophrenia or a related disorder did not. That is not generalizable.

Q: Why does that happen?

A: There is a lack of attention to the context of symptoms and other details, and there’s also a tendency to take patients literally. If a patient complains about x, there’s sometimes a pressure to directly address x. In fact, that’s not appropriate medicine. It is very important to pay attention to a patient’s stated concerns, but to place these concerns in the bigger picture. Clinicians can go too far in accepting at face value something that needs more exploration.

Q: What lessons do you hope to impart by publishing this case?

A: I want it to be understood that the diagnosis of schizophrenia has to be made with care. Clinicians need to take the necessary time and obtain the necessary information so that they’re not led astray. Eventually, we would like to have more objective measures for defining our disorders so that we do not need to rely totally on a clinical evaluation.

Learn more about Russell Margolis’ research regarding the challenges of diagnosing schizophrenia .

- About Johns Hopkins Medicine

- Contact Johns Hopkins Medicine

- Centers & Departments

- Maps & Directions

- Find a Doctor

- Patient Care

- Terms & Conditions of Use

- Privacy Statement

Connect with Johns Hopkins Medicine

Join Our Social Media Communities >

Clinical Connection

- Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery

- Contact Johns Hopkins

© The Johns Hopkins University, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Johns Hopkins Health System. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy and Disclaimer

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2022

Systematic literature review of schizophrenia clinical practice guidelines on acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics

- Christoph U. Correll ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7254-5646 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Amber Martin 4 ,

- Charmi Patel 5 ,

- Carmela Benson 5 ,

- Rebecca Goulding 6 ,

- Jennifer Kern-Sliwa 5 ,

- Kruti Joshi 5 ,

- Emma Schiller 4 &

- Edward Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8247-6675 7

Schizophrenia volume 8 , Article number: 5 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

51 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Schizophrenia

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) translate evidence into recommendations to improve patient care and outcomes. To provide an overview of schizophrenia CPGs, we conducted a systematic literature review of English-language CPGs and synthesized current recommendations for the acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics. Searches for schizophrenia CPGs were conducted in MEDLINE/Embase from 1/1/2004–12/19/2019 and in guideline websites until 06/01/2020. Of 19 CPGs, 17 (89.5%) commented on first-episode schizophrenia (FES), with all recommending antipsychotic monotherapy, but without agreement on preferred antipsychotic. Of 18 CPGs commenting on maintenance therapy, 10 (55.6%) made no recommendations on the appropriate maximum duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead individualization of care. Eighteen (94.7%) CPGs commented on long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs), mainly in cases of nonadherence (77.8%), maintenance care (72.2%), or patient preference (66.7%), with 5 (27.8%) CPGs recommending LAIs for FES. For treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 15/15 CPGs recommended clozapine. Only 7/19 (38.8%) CPGs included a treatment algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

A meta-analysis of effectiveness of real-world studies of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: Are the results consistent with the findings of randomized controlled trials?

Factors associated with successful antipsychotic dose reduction in schizophrenia: a systematic review of prospective clinical trials and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

The efficacy and heterogeneity of antipsychotic response in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis

Introduction.

Schizophrenia is an often debilitating, chronic, and relapsing mental disorder with complex symptomology that manifests as a combination of positive, negative, and/or cognitive features 1 , 2 , 3 . Standard management of schizophrenia includes the use of antipsychotic medications to help control acute psychotic episodes 4 and prevent relapses 5 , 6 , whereas maintenance therapy is used in the long term after patients have been stabilized 7 , 8 , 9 . Two main classes of drugs—first- and second-generation antipsychotics (FGA and SGA)—are used to treat schizophrenia 10 . SGAs are favored due to the lower rates of adverse effects, such as extrapyramidal effects, tardive dyskinesia, and relapse 11 . However, pharmacologic treatment for schizophrenia is complicated because nonadherence is prevalent, and is a major risk factor for relapse 9 and poor overall outcomes 12 . The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) versions of antipsychotics aims to limit nonadherence-related relapses and poor outcomes 13 .

Patient treatment pathways and treatment choices are determined based on illness acuity/severity, past treatment response and tolerability, as well as balancing medication efficacy and adverse effect profiles in the context of patient preferences and adherence patterns 14 , 15 . Clinical practice guidelines (CPG) serve to inform clinicians with recommendations that reflect current evidence from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), individual RCTs and, less so, epidemiologic studies, as well as clinical experience, with the goal of providing a framework and road-map for treatment decisions that will improve quality of care and achieve better patients outcomes. The use of clinical algorithms or other decision trees in CPGs may improve the ease of implementation of the evidence in clinical practice 16 . While CPGs are an important tool for mental health professionals, they have not been updated on a regular basis like they have been in other areas of medicine, such as in oncology. In the absence of current information, other governing bodies, healthcare systems, and hospitals have developed their own CPGs regarding the treatment of schizophrenia, and many of these have been recently updated 17 , 18 , 19 . As such, it is important to assess the latest guidelines to be aware of the changes resulting from consideration of updated evidence that informed the treatment recommendations. Since CPGs are comprehensive and include the diagnosis as well as the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of individuals with schizophrenia, a detailed comparative review of all aspects of CPGs for schizophrenia would have been too broad a review topic. Further, despite ongoing efforts to broaden the pharmacologic tools for the treatment of schizophrenia 20 , antipsychotics remain the cornerstone of schizophrenia management 8 , 21 . Therefore, a focused review of guideline recommendations for the management of schizophrenia with antipsychotics would serve to provide clinicians with relevant information for treatment decisions.

To provide an updated overview of United States (US) national and English language international guidelines for the management of schizophrenia, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify CPGs and synthesize current recommendations for pharmacological management with antipsychotics in the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia.

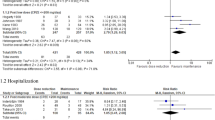

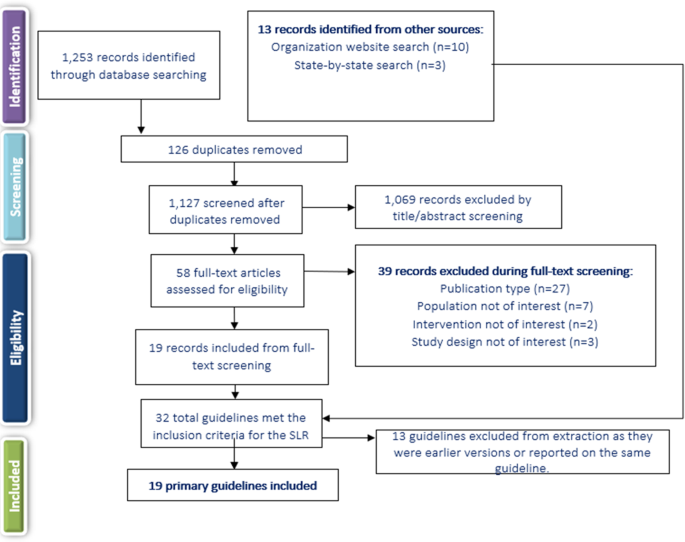

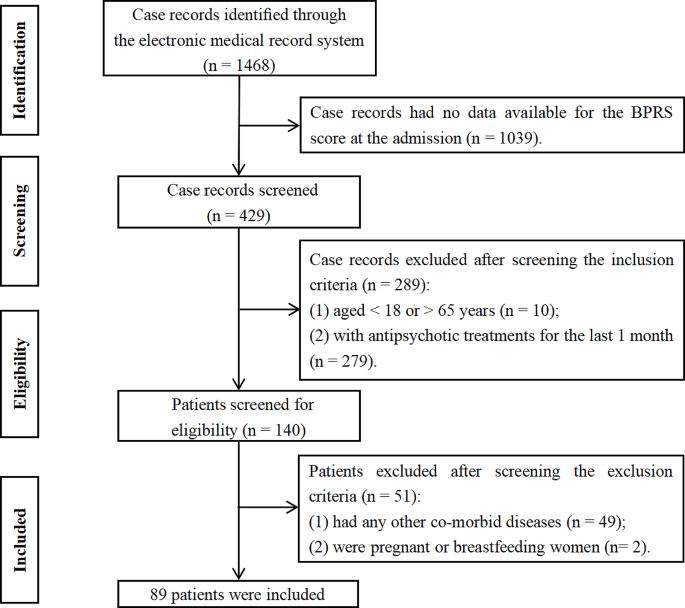

Systematic searches for the SLR yielded 1253 hits from the electronic literature databases. After removal of duplicate references, 1127 individual articles were screened at the title and abstract level. Of these, 58 publications were deemed eligible for screening at the full-text level, from which 19 were ultimately included in the SLR. Website searches of relevant organizations yielded 10 additional records, and an additional three records were identified by the state-by-state searches. Altogether, this process resulted in 32 records identified for inclusion in the SLR. Of the 32 sources, 19 primary CPGs, published/issued between 2004 and 2020, were selected for extraction, as illustrated in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1 ). While the most recent APA guideline was identified and available for download in 2020, the reference to cite in the document indicates a publication date of 2021.

SLR systematic literature review.

Of the 19 included CPGs (Table 1 ), three had an international focus (from the following organizations: International College of Neuropsychopharmacology [CINP] 22 , United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR] 23 , and World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry [WFSBP] 24 , 25 , 26 ); seven originated from the US; 17 , 18 , 19 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 three were from the United Kingdom (British Association for Psychopharmacology [BAP] 33 , the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] 34 , and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] 35 ); and one guideline each was from Singapore 36 , the Polish Psychiatric Association (PPA) 37 , 38 , the Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA) 14 , the Royal Australia/New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) 39 , the Association Française de Psychiatrie Biologique et de Neuropsychopharmacologie (AFPBN) from France 40 , and Italy 41 . Fourteen CPGs (74%) recommended treatment with specific antipsychotics and 18 (95%) included recommendations for the use of LAIs, while just seven included a treatment algorithm Table 2 ). The AGREE II assessment resulted in the highest score across the CPGs domains for NICE 34 followed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines 17 . The CPA 14 , BAP 33 , and SIGN 35 CPGs also scored well across domains.

Acute therapy

Seventeen CPGs (89.5%) provided treatment recommendations for patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , but the depth and focus of the information varied greatly (Supplementary Table 1 ). In some CPGs, information on treatment of a first schizophrenia episode was limited or grouped with information on treating any acute episode, such as in the CPGs from CINP 22 , AFPBN 40 , New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services (NJDMHS) 32 , the APA 17 , and the PPA 37 , 38 , while the others provided more detailed information specific to patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode 14 , 18 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 . The American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP) Clinical Tips did not provide any information on the treatment of schizophrenia patients with a first episode 29 .

There was little agreement among CPGs regarding the preferred antipsychotic for a first schizophrenia episode. However, there was strong consensus on antipsychotic monotherapy and that lower doses are generally recommended due to better treatment response and greater adverse effect sensitivity. Some guidelines recommended SGAs over FGAs when treating a first-episode schizophrenia patient (RANZCP 39 , Texas Medication Algorithm Project [TMAP] 28 , Oregon Health Authority 19 ), one recommended starting patients on an FGA (UNHCR 23 ), and others stated specifically that there was no evidence of any difference in efficacy between FGAs and SGAs (WFSBP 24 , CPA 14 , SIGN 35 , APA 17 , Singapore guidelines 36 ), or did not make any recommendation (CINP 22 , Italian guidelines 41 , NICE 34 , NJDMHS 32 , Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team [PORT] 30 , 31 ). The BAP 33 and WFBSP 24 noted that while there was probably no difference between FGAs and SGAs in efficacy, some SGAs (olanzapine, amisulpride, and risperidone) may perform better than some FGAs. The Schizophrenia PORT recommendations noted that while there seemed to be no differences between SGAs and FGAs in short-term studies (≤12 weeks), longer studies (one to two years) suggested that SGAs may provide benefits in terms of longer times to relapse and discontinuation rates 30 , 31 . The AFPBN guidelines 40 and Florida Medicaid Program guidelines 18 , which both focus on use of LAI antipsychotics, both recommended an SGA-LAI for patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode. A caveat in most CPGs was that physicians and their patients should discuss decisions about the choice of antipsychotic and that the choice should consider individual patient factors/preferences, risk of adverse and metabolic effects, and symptom patterns 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 .

Most CPGs recommended switching to a different monotherapy if the initial antipsychotic was not effective or not well tolerated after an adequate antipsychotic trial at an appropriate dose 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 39 . For patients initially treated with an FGA, the UNHCR recommended switching to an SGA (olanzapine or risperidone) 23 . Guidance on response to treatment varied in the measures used but typically required at least a 20% improvement in symptoms (i.e. reduction in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale or Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores) from pre-treatment levels.

Several CPGs contained recommendations on the duration of antipsychotic therapy after a first schizophrenia episode. The NJDMHS guidelines 32 recommended nine to 12 months; CINP 22 recommended at least one year; CPA 14 recommended at least 18 months; WFSBP 25 , the Italian guidelines 41 , and NICE 34 recommended 1 to 2 years; and the RANZCP 39 , BAP 33 , and SIGN 35 recommended at least 2 years. The APA 17 and TMAP 28 recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific length of therapy.

Twelve guidelines 14 , 18 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 (63.2%) discussed the treatment of subsequent/multiple episodes of schizophrenia (i.e., following relapse). These CPGs noted that the considerations guiding the choice of antipsychotic for subsequent/multiple episodes were similar to those for a first episode, factoring in prior patient treatment response, adverse effect patterns and adherence. The CPGs also noted that response to treatment may be lower and require higher doses to achieve a response than for first-episode schizophrenia, that a different antipsychotic than used to treat the first episode may be needed, and that a switch to an LAI is an option.

Several CPGs provided recommendations for patients with specific clinical features (Supplementary Table 1 ). The most frequently discussed group of clinical features was negative symptoms, with recommendations provided in the CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , WFSBP 24 , AFPBN 40 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS guidelines; 32 negative symptoms were the sole focus of the guidelines from the PPA 37 , 38 . The guidelines noted that due to limited evidence in patients with predominantly negative symptoms, there was no clear benefit for any strategy, but that options included SGAs (especially amisulpride) rather than FGAs (WFSBP 24 , CINP 22 , AFPBN 40 , SIGN 35 , NJDMHS 32 , PPA 37 , 38 ), and addition of an antidepressant (WFSBP 24 , UNHCR 23 , SIGN 35 , NJDMHS 32 ) or lamotrigine (SIGN 35 ), or switching to another SGA (NJDMHS 32 ) or clozapine (NJDMHS 32 ). The PPA guidelines 37 , 38 stated that the use of clozapine or adding an antidepressant or other medication class was not supported by evidence, but recommended the SGA cariprazine for patients with predominant and persistent negative symptoms, and other SGAs for those with full-spectrum negative symptoms. However, the BAP 33 stated that no recommendations can be made for any of these strategies because of the quality and paucity of the available evidence.

Some of the CPGs also discussed treatment of other clinical features to a limited degree, including depressive symptoms (CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , CPA 14 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS 32 ), cognitive dysfunction (CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , WFSBP 24 , AFPBN 40 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and NJDMHS 32 ), persistent aggression (CINP 22 , WFSBP 24 , CPA 14 , AFPBN 40 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and NJDMHS 32 ), and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (CINP 22 , RANZCP 39 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS 32 ).

Fifteen CPGs (78.9%) discussed treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS); all defined it as persistent, predominantly positive symptoms after two adequate antipsychotic trials; clozapine was the unanimous first choice 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 . However, the UNHCR guidelines 23 , which included recommendations for treatment of refugees, noted that clozapine is only a reasonable choice in regions where white blood cell monitoring and specialist supervision are available, otherwise, risperidone or olanzapine are alternatives if they had not been used in the previous treatment regimen.

There were few options for patients who are resistant to clozapine therapy, and evidence supporting these options was limited. The CPA guidelines 14 therefore stated that no recommendation can be given due to inadequate evidence. Other CPGs discussed options (but noted there was limited supporting evidence), such as switching to olanzapine or risperidone (WFSBP 24 , TMAP 28 ), adding a second antipsychotic to clozapine (CINP 22 , NICE 34 , TMAP 28 , BAP 33 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , RANZCP 39 ), adding lamotrigine or topiramate to clozapine (CINP 22 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 ), combination therapy with two non-clozapine antipsychotics (Florida Medicaid Program 18 , NJDMHS 32 ), and high-dose non-clozapine antipsychotic therapy (BAP 33 , SIGN 35 ). Electroconvulsive therapy was noted as a last resort for patients who did not respond to any pharmacologic therapy, including clozapine, by 10 CPGs 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 39 .

Maintenance therapy

Fifteen CPGs (78.9%) discussed maintenance therapy to various degrees via dedicated sections or statements, while three others referred only to maintenance doses by antipsychotic agent 18 , 23 , 29 without accompanying recommendations (Supplementary Table 2 ). Only the Italian guideline provided no reference or comments on maintenance treatment. The CINP 22 , WFSBP 25 , RANZCP 39 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 recommended keeping patients on the same antipsychotic and at the same dose on which they had achieved remission. Several CPGs recommended maintenance therapy at the lowest effective dose (NJDMHS 32 , APA 17 , Singapore guidelines 36 , and TMAP 28 ). The CPA 14 and SIGN 35 defined the lower dose as 300–400 mg chlorpromazine equivalents or 4–6 mg risperidone equivalents, and the Singapore guidelines 36 stated that the lower dose should not be less than half the original dose. TMAP 28 stated that given the relapsing nature of schizophrenia, the maintenance dose should often be close to the original dose. While SIGN 35 recommended that patients remain on the same antipsychotic that provided remission, these guidelines also stated that maintenance with amisulpride, olanzapine, or risperidone was preferred, and that chlorpromazine and other low-potency FGAs were also suitable. The BAP 33 recommended that the current regimen be optimized before any dose reduction or switch to another antipsychotic occurs. Several CPGs recommended LAIs as an option for maintenance therapy (see next section).

Altogether, 10/18 (55.5%) CPGs made no recommendations on the appropriate duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead that each patient should be considered individually. Other CPGs made specific recommendations: Both the Both BAP 33 and SIGN 35 guidelines suggested a minimum of 2 years, the NJDMHS guidelines 32 recommended 2–3 years; the WFSBP 25 recommended 2–5 years for patients who have had one relapse and more than 5 years for those who have had multiple relapses; the RANZCP 39 and the CPA 14 recommended 2–5 years; and the CINP 22 recommended that maintenance therapy last at least 6 years for patients who have had multiple episodes. The TMAP was the only CPG to recommend that maintenance therapy be continued indefinitely 28 .

Recommendations on the use of LAIs

All CPGs except the one from Italy (94.7%) discussed the use of LAIs for patients with schizophrenia to some extent. As shown in Table 3 , among the 18 CPGs, LAIs were primarily recommended in 14 CPGs (77.8%) for patients who are non-adherent to other antipsychotic administration routes (CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , RANZCP 39 , PPA 37 , 38 , Singapore guidelines 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , TMAP 28 , NJDMHS 32 , AACP 29 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 ). Twelve CPGs (66.7%) also noted that LAIs should be prescribed based on patient preference (RANZCP 39 , CPA 14 , AFPBN 40 , Singapore guidelines 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 , AACP 29 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 ).

Thirteen CPGs (72.2%) recommended LAIs as maintenance therapy 18 , 19 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 . While five CPGs (27.8%), i.e., AFPBN 40 , RANZCP 39 , TMAP 28 , NJDMHS 32 , and the Florida Medicaid Program 18 recommended LAIs specifically for patients experiencing a first episode. While the CPA 14 did not make any recommendations regarding when LAIs should be used, they discussed recent evidence supporting their use earlier in treatment. Five guidelines (27.8%, i.e., Singapore 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ) noted that evidence around LAIs was not sufficient to support recommending their use for first-episode patients. The AFPBN guidelines 40 also stated that LAIs (SGAs as first-line and FGAs as second-line treatment) should be more frequently considered for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Four CPGs (22.2%, i.e., CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , Italian guidelines 41 , PPA guidelines 37 , 38 ) did not specify when LAIs should be used. The AACP guidelines 29 , which evaluated only LAIs, recommended expanding their use beyond treatment for nonadherence, suggesting that LAIs may offer a more convenient mode of administration or potentially address other clinical and social challenges, as well as provide more consistent plasma levels.

Treatment algorithms

Only Seven CPGs (36.8%) included an algorithm as part of the treatment recommendations. These included decision trees or flow diagrams that map out initial therapy, durations for assessing response, and treatment options in cases of non-response. However, none of these guidelines defined how to measure response, a theme that also extended to guidelines that did not include treatment algorithms. Four of the seven guidelines with algorithms recommended specific antipsychotic agents, while the remaining three referred only to the antipsychotic class.

LAIs were not consistently incorporated in treatment algorithms and in six CPGs were treated as a separate category of medicine reserved for patients with adherence issues or a preference for the route of administration. The only exception was the Florida Medicaid Program 18 , which recommended offering LAIs after oral antipsychotic stabilization even to patients who are at that point adherent to oral antipsychotics.

Benefits and harms

The need to balance the efficacy and safety of antipsychotics was mentioned by all CPGs as a basic treatment paradigm.

Ten CPGs provided conclusions on benefits of antipsychotic therapy. The APA 17 and the BAP 33 guidelines stated that antipsychotic treatment can improve the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis and leads to remission of symptoms. These CPGs 17 , 33 as well as those from NICE 34 and CPA 14 stated that these treatment effects can also lead to improvements in quality of life (including quality-adjusted life years), improved functioning, and reduction in disability. The CPA 14 and APA 17 guidelines noted decreases in hospitalizations with antipsychotic therapy, and the APA guidelines 17 stated that long-term antipsychotic treatment can also reduce mortality. The UNHCR 23 and the Italian 41 guidelines noted that early intervention increased positive outcomes. The WFSBP 24 , AFPBN 40 , CPA 14 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS 32 affirmed that relapse prevention is a benefit of continued/maintenance treatment.

Some CPGs (WFSBP 24 , Italian 41 , CPA 14 , and SIGN 35 ) noted that reduced risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects and treatment discontinuation were potential benefits of SGAs vs. FGAs.

The risk of adverse effects (e.g., extrapyramidal, metabolic, cardiovascular, and hormonal adverse effects, sedation, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome) was noted by all CPGs as the major potential harm of antipsychotic therapy 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 . These adverse effects are known to limit long-term treatment and adherence 24 .

This SLR of CPGs for the treatment of schizophrenia yielded 19 most updated versions of individual CPGs, published/issued between 2004 and 2020. Structuring our comparative review according to illness phase, antipsychotic type and formulation, response to antipsychotic treatment as well as benefits and harms, several areas of consistent recommendations emerged from this review (e.g., balancing risk and benefits of antipsychotics, preferring antipsychotic monotherapy; using clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia). On the other hand, other recommendations regarding other areas of antipsychotic treatment were mostly consistent (e.g., maintenance antipsychotic treatment for some time), somewhat inconsistent (e.g., differences in the management of first- vs multi-episode patients, type of antipsychotic, dose of antipsychotic maintenance treatment), or even contradictory (e.g., role of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia patients).

Consistent with RCT evidence 43 , 44 , antipsychotic monotherapy was the treatment of choice for patients with first-episode schizophrenia in all CPGs, and all guidelines stated that a different single antipsychotic should be tried if the first is ineffective or intolerable. Recommendations were similar for multi-episode patients, but factored in prior patient treatment response, adverse effect patterns, and adherence. There was also broad consensus that the side-effect profile of antipsychotics is the most important consideration when making a decision on pharmacologic treatment, also reflecting meta-analytic evidence 4 , 5 , 10 . The risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (especially with FGAs) and metabolic effects (especially with SGAs) were noted as key considerations, which are also reflected in the literature as relevant concerns 4 , 45 , 46 , including for quality of life and treatment nonadherence 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 .

Largely consistent with the comparative meta-analytic evidence regarding the acute 4 , 51 , 52 and maintenance antipsychotic treatment 5 effects of schizophrenia, the majority of CPGs stated there was no difference in efficacy between SGAs and FGAs (WFSBP 24 , CPA 14 , SIGN 35 , APA 17 , and Singapore guidelines 36 ), or did not make any recommendations (CINP 22 , Italian guidelines 41 , NICE 34 , NJDMHS 32 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ); three CPGs (BAP 33 , WFBSP 24 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ) noted that SGAs may perform better than FGAs over the long term, consistent with a meta-analysis on this topic 53 .

The 12 CPGs that discussed treatment of subsequent/multiple episodes generally agreed on the factors guiding the choices of an antipsychotic, including that the decision may be more complicated and response may be lower than with a first episode, as described before 7 , 54 , 55 , 56 .

There was little consensus regarding maintenance therapy. Some CPGs recommended the same antipsychotic and dose that achieved remission (CINP 22 , WFSBP 25 , RANZCP 39 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ) and others recommended the lowest effective dose (NJDMHS 32 , APA 17 , Singapore guidelines 36 , TMAP 28 , CPA 14 , and SIGN 35 ). This inconsistency is likely based on insufficient data as well as conflicting results in existing meta-analyses on this topic 57 , 58 , 59 .

The 15 CPGs that discussed TRS all used the same definition for this condition, consistent with recent commendations 60 , and agreed that clozapine is the primary evidence-based treatment choice 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , reflecting the evidence base 61 , 62 , 63 . These CPGs also agreed that there are few options well supported by evidence for patients who do not respond to clozapine, with a recent meta-analysis of RCTs showing that electroconvulsive therapy augmentation may be the most evidence-based treatment option 64 .

One key gap in the treatment recommendations was how long patients should remain on antipsychotic therapy after a first episode or during maintenance therapy. While nine of the 17 CPGs discussing treatment of a first episode provided a recommended timeframe (varying from 1 to 2 years) 14 , 22 , 24 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 , the APA 17 and TMAP 28 recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific length of therapy. Similarly, six of the 18 CPGs discussing maintenance treatment recommended a specific duration of therapy (ranging from two to six years) 14 , 22 , 25 , 32 , 39 , while as many as 10 CPGs did not point to a firm end of the maintenance treatment, instead recommending individualized decisions. The CPGs not stating a definite endpoint or period of maintenance treatment after repeated schizophrenia episodes or even after a first episode of schizophrenia, reflects the different evidence types on which the recommendation is based. The RCT evidence ends after several years of maintenance treatment vs. discontinuation supporting ongoing antipsychotic treatment; however, naturalistic database studies do not indicate any time period after which one can safely discontinue maintenance antipsychotic care, even after a first schizophrenia episode 8 , 65 . In fact, stopping antipsychotics is associated not only with a substantially increased risk of hospitalization but also mortality 65 , 66 , 67 . In this sense, not stating an endpoint for antipsychotic maintenance therapy should not be taken as an implicit statement that antipsychotics should be discontinued at any time; data suggest the contrary.

A further gap exists regarding the most appropriate treatment of negative symptoms, such as anhedonia, amotivation, asociality, affective flattening, and alogia 1 , a long-standing challenge in the management of patients with schizophrenia. Negative symptoms often persist in patients after positive symptoms have resolved, or are the presenting feature in a substantial minority of patients 22 , 35 . Negative symptoms can also be secondary to pharmacotherapy 22 , 68 . Antipsychotics have been most successful in treating positive symptoms, and while eight of the CPGs provided some information on treatment of negative symptoms, the recommendations were generally limited 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 40 . Negative symptom management was a focus of the PPA guidelines, but the guidelines acknowledged that supporting evidence was limited, often due to the low number of patients with predominantly negative symptoms in clinical trials 37 , 38 . The Polish guidelines are also one of the more recently developed and included the newer antipsychotic cariprazine as a first-line option, which although being a point of differentiation from the other guidelines, this recommendation was based on RCT data 69 .

Another area in which more direction is needed is on the use of LAIs. While all but one of the 19 CPGs discussed this topic, the extent of information and recommendations for LAI use varied considerably. All CPGs categorized LAIs as an option to improve adherence to therapy or based on patient preference. However, 5/18 CPGs (27.8%) recommended the use of LAI early in treatment (at first episode: AFPBN 40 , RANZCP 39 , TMAP 28 , NJDMHS 32 , and Florida Medicaid Program 18 ) or across the entire illness course, while five others stated there was not sufficient evidence to recommend LAIs for these patients (Singapore 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ). The role of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia was the only point where opposing recommendations were found across CPGs. This contradictory stance was not due to the incorporation of newer data suggesting benefits of LAIs in first episode and early-phase patients with schizophrenia 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 in the CPGs recommending LAI use in first-episode patients, as CPGs recommending LAI use were published between 2005 and 2020, while those opposing LAI use were published between 2011 and 2020. Only the Florida Medicaid CPG recommended LAIs as a first step equivalent to oral antipsychotics (OAP) after initial OAP response and tolerability, independent of nonadherence or other clinical variables. This guideline was also the only CPG to fully integrate LAI use in their clinical algorithm. The remaining six CPGs that included decision tress or treatment algorithms regarded LAIs as a separate paradigm of treatment reserved for nonadherence or patients preference rather than a routine treatment option to consider. While some CPGs provided fairly detailed information on the use of LAIs (AFPBN 40 , AACP 29 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , and Florida Medicaid Program 18 ), others mentioned them only in the context of adherence issues or patient preference. Notably, definitions of and means to determine nonadherence were not reported. One reason for this wide range of recommendations regarding the placement of LAIs in the treatment algorithm and clinical situations that prompt LAI use might be due to the fact that CPGs generally favor RCT evidence over evidence from other study designs. In the case of LAIs, there was a notable dissociation between consistent meta-analytic evidence of statistically significant superiority of LAIs vs OAPs in mirror-image 75 and cohort study designs 76 and non-significant advantages in RCTs 77 . Although patients in RCTs comparing LAIs vs OAPs were less severely ill and more adherent to OAPs 77 than in clinical care and although mirror-image and cohort studies arguably have greater external validity than RCTs 78 , CPGs generally disregard evidence from other study designs when RCT evidence exits. This narrow focus can lead to disregarding important additional data. Nevertheless, a most updated meta-analysis of all 3 study designs comparing LAIs with OAPs demonstrated consistent superiority of LAIs vs OAPs for hospitalization or relapse across all 3 designs 79 , which should lead to more uniform recommendations across CPGs in the future.

Only seven CPGs included treatment algorithms or flow charts to guide LAI treatment selection for patients with schizophrenia 17 , 18 , 19 , 24 , 29 , 35 , 40 . However, there was little commonality across algorithms beyond the guidance on LAIs mentioned above, as some listed specific treatments and conditions for antipsychotic switches, while others indicated that medication choice should be based on a patient’s preferences and responses, side effects, and in some cases, cost effectiveness. Since algorithms and flow charts facilitate the reception, adoption and implementation of guidelines, future CPGs should include them as dissemination tools, but they need to reflect the data and detailed text and be sufficiently specific to be actionable.

The systematic nature in the identification, summarization, and assessment of the CPGs is a strength of this review. This process removed any potential bias associated with subjective selection of evidence, which is not reproducible. However, only CPGs published in English were included and regardless of their quality and differing timeframes of development and publication, complicating a direct comparison of consensus and disagreement. Finally, based on the focus of this SLR, we only reviewed pharmacologic management with antipsychotics. Clearly, the assessment, other pharmacologic and, especially, psychosocial interventions are important in the management of individuals with schizophrenia, but these topics that were covered to varying degrees by the evaluated CPGs were outside of the scope of this review.

Numerous guidelines have recently updated their recommendations on the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia, which we have summarized in this review. Consistent recommendations were observed across CPGs in the areas of balancing risk and benefits of antipsychotics when selecting treatment, a preference for antipsychotic monotherapy, especially for patients with a first episode of schizophrenia, and the use of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. By contrast, there were inconsistencies with regards to recommendations on maintenance antipsychotic treatment, with differences existing on type and dose of antipsychotic, as well as the duration of therapy. However, LAIs were consistently recommended, but mainly suggested in cases of nonadherence or patient preference, despite their established efficacy in broader patient populations and clinical scenarios in clinical trials. Guidelines were sometimes contradictory, with some recommending LAI use earlier in the disease course (e.g., first episode) and others suggesting they only be reserved for later in the disease. This inconsistency was not due to lack of evidence on the efficacy of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia or the timing of the CPG, so that other reasons might be responsible, including possibly bias and stigma associated with this route of treatment administration. Lastly, gaps existed in the guidelines for recommendations on the duration of maintenance treatment, treatment of negative symptoms, and the development/use of treatment algorithms whenever evidence is sufficient to provide a simplified summary of the data and indicate their relevance for clinical decision making, all of which should be considered in future guideline development/revisions.

The SLR followed established best methods used in systematic review research to identify and assess the available CPGs for pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotics in the acute and maintenance phases 80 , 81 . The SLR was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, including use of a prespecified protocol to outline methods for conducting the review. The protocol for this review was approved by all authors prior to implementation but was not submitted to an external registry.

Data sources and search algorithms

Searches were conducted by two independent investigators in the MEDLINE and Embase databases via OvidSP to identify CPGs published in English. Articles were identified using search algorithms that paired terms for schizophrenia with keywords for CPGs. Articles indexed as case reports, reviews, letters, or news were excluded from the searches. The database search was limited to CPGs published from January 1, 2004, through December 19, 2019, without limit to geographic location. In addition to the database sources, guideline body websites and state-level health departments from the US were also searched for relevant CPGs published through June 2020. A manual check of the references of recent (i.e., published in the past three years), relevant SLRs and relevant practice CPGs was conducted to supplement the above searches and ensure and the most complete CPG retrieval.

This study did not involve human subjects as only published evidence was included in the review; ethical approval from an institution was therefore not required.

Selection of CPGs for inclusion

Each title and abstract identified from the database searches was screened and selected for inclusion or exclusion in the SLR by two independent investigators based on the populations, interventions/comparators, outcomes, study design, time period, language, and geographic criteria shown in Table 4 . During both rounds of the screening process, discrepancies between the two independent reviewers were resolved through discussion, and a third investigator resolved any disagreement. Articles/documents identified by the manual search of organizational websites were screened using the same criteria. All accepted studies were required to meet all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Only the most recent version of organizational CPGs was included for data extraction.

Data extraction and synthesis

Information on the recommendations regarding the antipsychotic management in the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia and related benefits and harms was captured from the included CPGs. Each guideline was reviewed and extracted by a single researcher and the data were validated by a senior team member to ensure accuracy and completeness. Additionally, each included CPG was assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool. Following extraction and validation, results were qualitatively summarized across CPGs.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the SLR are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Correll, C. U. & Schooler, N. R. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16 , 519–534 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kahn, R. S. et al. Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1 , 15067 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Millan, M. J. et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 , 485–515 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Huhn, M. et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 394 , 939–951 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kishimoto, T., Hagi, K., Nitta, M., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Long-term effectiveness of oral second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct head-to-head comparisons. World Psychiatry 18 , 208–224 (2019).

Leucht, S. et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379 , 2063–2071 (2012).

Carbon, M. & Correll, C. U. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16 , 505–524 (2014).

Correll, C. U., Rubio, J. M. & Kane, J. M. What is the risk-benefit ratio of long-term antipsychotic treatment in people with schizophrenia? World Psychiatry 17 , 149–160 (2018).

Emsley, R., Chiliza, B., Asmal, L. & Harvey, B. H. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 13 , 50 (2013).

Correll, C. U. & Kane, J. M. Ranking antipsychotics for efficacy and safety in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 77 , 225–226 (2020).

Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 12 , 345–357 (2010).

Kane, J. M., Kishimoto, T. & Correll, C. U. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry 12 , 216–226 (2013).

Correll, C. U. et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77 , 1–24 (2016).

Remington, G. et al. Guidelines for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia in adults. Can. J. Psychiatry 62 , 604–616 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Treatment recommendations for patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 161 , 1–56 (2004).

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Field, M. J., & Lohr, K. N. (Eds.). Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. (National Academies Press (US), 1990).

American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia , 3rd edn. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841 .

Florida Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program. 2019–2020 Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults . (2020). Available at: https://floridabhcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2019-Psychotherapeutic-Medication-Guidelines-for-Adults-with-References_06-04-20.pdf .

Mental Health Clinical Advisory Group, Oregon Health Authority. Mental Health Care Guide for Licensed Practitioners and Mental Health Professionals. (2019). Available at: https://sharedsystems.dhsoha.state.or.us/DHSForms/Served/le7548.pdf .

Krogmann, A. et al. Keeping up with the therapeutic advances in schizophrenia: a review of novel and emerging pharmacological entities. CNS Spectr. 24 , 38–69 (2019).

Fountoulakis, K. N. et al. The report of the joint WPA/CINP workgroup on the use and usefulness of antipsychotic medication in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr . https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001546 (2020).

Leucht, S. et al. CINP Schizophrenia Guidelines . (CINP, 2013). Available at: https://www.cinp.org/resources/Documents/CINP-schizophrenia-guideline-24.5.2013-A-C-method.pdf .

Ostuzzi, G. et al. Mapping the evidence on pharmacological interventions for non-affective psychosis in humanitarian non-specialised settings: A UNHCR clinical guidance. BMC Med. 15 , 197 (2017).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 1: Update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 13 , 318–378 (2012).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 2: Update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 14 , 2–44 (2013).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia - a short version for primary care. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 21 , 82–90 (2017).

Moore, T. A. et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68 , 1751–1762 (2007).

Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP). Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Procedural Manual . (2008). Available at: https://jpshealthnet.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/tmapalgorithmforschizophrenia.pdf .

American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP). Clinical Tips Series, Long Acting Antipsychotic Medications. (2017). Accessed at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view .

Buchanan, R. W. et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr. Bull. 36 , 71–93 (2010).

Kreyenbuhl, J. et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr. Bull. 36 , 94–103 (2010).

New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services. Pharmacological Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Schizophrenia . (2005). Available at: https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dmhs_delete/consumer/NJDMHS_Pharmacological_Practice_Guidelines762005.pdf .

Barnes, T. R. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 34 , 3–78 (2020).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. (2014). Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 .

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of Schizophrenia: A National Clinical Guideline . (2013). Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign131.pdf .

Verma, S. et al. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Schizophrenia. Singap. Med. J. 52 , 521–526 (2011).

CAS Google Scholar

Szulc, A. et al. Recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms. Standards of pharmacotherapy by the Polish Psychiatric Association (Polskie Towarzystwo Psychiatryczne), part 1. Rekomendacje dotyczace leczenia schizofrenii z. objawami negatywnymi. Stand. farmakoterapii Polskiego Tow. Psychiatrycznego, czesc 1. 53 , 497–524 (2019).

Google Scholar

Szulc, A. et al. Recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms. Standards of pharmacotherapy by the Polish Psychiatric Association (Polskie Towarzystwo Psychiatryczne), part 2. Rekomendacje dotyczace leczenia schizofrenii z. objawami negatywnymi. Stand. farmakoterapii Polskiego Tow. Psychiatrycznego, czesc 2. 53 , 525–540 (2019).

Galletly, C. et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50 , 410–472 (2016).

Llorca, P. M. et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 13 , 340 (2013).

De Masi, S. et al. The Italian guidelines for early intervention in schizophrenia: development and conclusions. Early Intervention Psychiatry 2 , 291–302 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Barnes, T. R. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 25 , 567–620 (2011).

Correll, C. U. et al. Efficacy of 42 pharmacologic cotreatment strategies added to antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic overview and quality appraisal of the meta-analytic evidence. JAMA Psychiatry 74 , 675–684 (2017).

Galling, B. et al. Antipsychotic augmentation vs. monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. World Psychiatry 16 , 77–89 (2017).

Pillinger, T. et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , 64–77 (2020).

Rummel-Kluge, C. et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Schizophr. Bull. 38 , 167–177 (2012).

Angermeyer, M. C. & Matschinger, H. Attitude of family to neuroleptics. Psychiatr. Prax. 26 , 171–174 (1999).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dibonaventura, M., Gabriel, S., Dupclay, L., Gupta, S. & Kim, E. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 12 , 20 (2012).

McIntyre, R. S. Understanding needs, interactions, treatment, and expectations among individuals affected by bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: the UNITE global survey. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70 (Suppl 3), 5–11 (2009).

Tandon, R. et al. The impact on functioning of second-generation antipsychotic medication side effects for patients with schizophrenia: a worldwide, cross-sectional, web-based survey. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 19 , 42 (2020).