- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Preparation and Procedures Involved in Gender Affirmation Surgeries

If you or a loved one are considering gender affirmation surgery , you are probably wondering what steps you must go through before the surgery can be done. Let's look at what is required to be a candidate for these surgeries, the potential positive effects and side effects of hormonal therapy, and the types of surgeries that are available.

Gender affirmation surgery, also known as gender confirmation surgery, is performed to align or transition individuals with gender dysphoria to their true gender.

A transgender woman, man, or non-binary person may choose to undergo gender affirmation surgery.

The term "transexual" was previously used by the medical community to describe people who undergo gender affirmation surgery. The term is no longer accepted by many members of the trans community as it is often weaponized as a slur. While some trans people do identify as "transexual", it is best to use the term "transgender" to describe members of this community.

Transitioning

Transitioning may involve:

- Social transitioning : going by different pronouns, changing one’s style, adopting a new name, etc., to affirm one’s gender

- Medical transitioning : taking hormones and/or surgically removing or modifying genitals and reproductive organs

Transgender individuals do not need to undergo medical intervention to have valid identities.

Reasons for Undergoing Surgery

Many transgender people experience a marked incongruence between their gender and their assigned sex at birth. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has identified this as gender dysphoria.

Gender dysphoria is the distress some trans people feel when their appearance does not reflect their gender. Dysphoria can be the cause of poor mental health or trigger mental illness in transgender people.

For these individuals, social transitioning, hormone therapy, and gender confirmation surgery permit their outside appearance to match their true gender.

Steps Required Before Surgery

In addition to a comprehensive understanding of the procedures, hormones, and other risks involved in gender-affirming surgery, there are other steps that must be accomplished before surgery is performed. These steps are one way the medical community and insurance companies limit access to gender affirmative procedures.

Steps may include:

- Mental health evaluation : A mental health evaluation is required to look for any mental health concerns that could influence an individual’s mental state, and to assess a person’s readiness to undergo the physical and emotional stresses of the transition.

- Clear and consistent documentation of gender dysphoria

- A "real life" test : The individual must take on the role of their gender in everyday activities, both socially and professionally (known as “real-life experience” or “real-life test”).

Firstly, not all transgender experience physical body dysphoria. The “real life” test is also very dangerous to execute, as trans people have to make themselves vulnerable in public to be considered for affirmative procedures. When a trans person does not pass (easily identified as their gender), they can be clocked (found out to be transgender), putting them at risk for violence and discrimination.

Requiring trans people to conduct a “real-life” test despite the ongoing violence out transgender people face is extremely dangerous, especially because some transgender people only want surgery to lower their risk of experiencing transphobic violence.

Hormone Therapy & Transitioning

Hormone therapy involves taking progesterone, estrogen, or testosterone. An individual has to have undergone hormone therapy for a year before having gender affirmation surgery.

The purpose of hormone therapy is to change the physical appearance to reflect gender identity.

Effects of Testosterone

When a trans person begins taking testosterone , changes include both a reduction in assigned female sexual characteristics and an increase in assigned male sexual characteristics.

Bodily changes can include:

- Beard and mustache growth

- Deepening of the voice

- Enlargement of the clitoris

- Increased growth of body hair

- Increased muscle mass and strength

- Increase in the number of red blood cells

- Redistribution of fat from the breasts, hips, and thighs to the abdominal area

- Development of acne, similar to male puberty

- Baldness or localized hair loss, especially at the temples and crown of the head

- Atrophy of the uterus and ovaries, resulting in an inability to have children

Behavioral changes include:

- Aggression

- Increased sex drive

Effects of Estrogen

When a trans person begins taking estrogen , changes include both a reduction in assigned male sexual characteristics and an increase in assigned female characteristics.

Changes to the body can include:

- Breast development

- Loss of erection

- Shrinkage of testicles

- Decreased acne

- Decreased facial and body hair

- Decreased muscle mass and strength

- Softer and smoother skin

- Slowing of balding

- Redistribution of fat from abdomen to the hips, thighs, and buttocks

- Decreased sex drive

- Mood swings

When Are the Hormonal Therapy Effects Noticed?

The feminizing effects of estrogen and the masculinizing effects of testosterone may appear after the first couple of doses, although it may be several years before a person is satisfied with their transition. This is especially true for breast development.

Timeline of Surgical Process

Surgery is delayed until at least one year after the start of hormone therapy and at least two years after a mental health evaluation. Once the surgical procedures begin, the amount of time until completion is variable depending on the number of procedures desired, recovery time, and more.

Transfeminine Surgeries

Transfeminine is an umbrella term inclusive of trans women and non-binary trans people who were assigned male at birth.

Most often, surgeries involved in gender affirmation surgery are broken down into those that occur above the belt (top surgery) and those below the belt (bottom surgery). Not everyone undergoes all of these surgeries, but procedures that may be considered for transfeminine individuals are listed below.

Top surgery includes:

- Breast augmentation

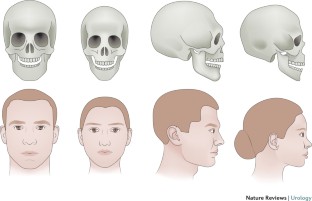

- Facial feminization

- Nose surgery: Rhinoplasty may be done to narrow the nose and refine the tip.

- Eyebrows: A brow lift may be done to feminize the curvature and position of the eyebrows.

- Jaw surgery: The jaw bone may be shaved down.

- Chin reduction: Chin reduction may be performed to soften the chin's angles.

- Cheekbones: Cheekbones may be enhanced, often via collagen injections as well as other plastic surgery techniques.

- Lips: A lip lift may be done.

- Alteration to hairline

- Male pattern hair removal

- Reduction of Adam’s apple

- Voice change surgery

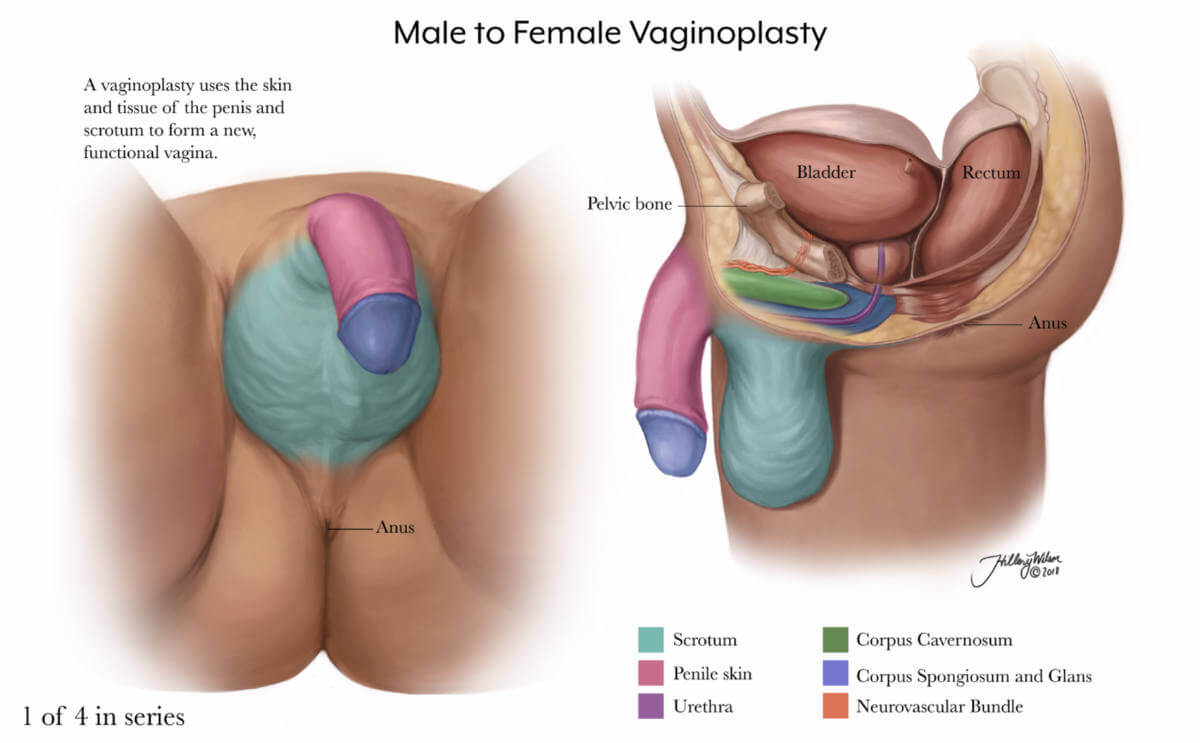

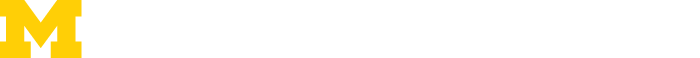

Bottom surgery includes:

- Removal of the penis (penectomy) and scrotum (orchiectomy)

- Creation of a vagina and labia

Transmasculine Surgeries

Transmasculine is an umbrella term inclusive of trans men and non-binary trans people who were assigned female at birth.

Surgery for this group involves top surgery and bottom surgery as well.

Top surgery includes :

- Subcutaneous mastectomy/breast reduction surgery.

- Removal of the uterus and ovaries

- Creation of a penis and scrotum either through metoidioplasty and/or phalloplasty

Complications and Side Effects

Surgery is not without potential risks and complications. Estrogen therapy has been associated with an elevated risk of blood clots ( deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli ) for transfeminine people. There is also the potential of increased risk of breast cancer (even without hormones, breast cancer may develop).

Testosterone use in transmasculine people has been associated with an increase in blood pressure, insulin resistance, and lipid abnormalities, though it's not certain exactly what role these changes play in the development of heart disease.

With surgery, there are surgical risks such as bleeding and infection, as well as side effects of anesthesia . Those who are considering these treatments should have a careful discussion with their doctor about potential risks related to hormone therapy as well as the surgeries.

Cost of Gender Confirmation Surgery

Surgery can be prohibitively expensive for many transgender individuals. Costs including counseling, hormones, electrolysis, and operations can amount to well over $100,000. Transfeminine procedures tend to be more expensive than transmasculine ones. Health insurance sometimes covers a portion of the expenses.

Quality of Life After Surgery

Quality of life appears to improve after gender-affirming surgery for all trans people who medically transition. One 2017 study found that surgical satisfaction ranged from 94% to 100%.

Since there are many steps and sometimes uncomfortable surgeries involved, this number supports the benefits of surgery for those who feel it is their best choice.

A Word From Verywell

Gender affirmation surgery is a lengthy process that begins with counseling and a mental health evaluation to determine if a person can be diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

After this is complete, hormonal treatment is begun with testosterone for transmasculine individuals and estrogen for transfeminine people. Some of the physical and behavioral changes associated with hormonal treatment are listed above.

After hormone therapy has been continued for at least one year, a number of surgical procedures may be considered. These are broken down into "top" procedures and "bottom" procedures.

Surgery is costly, but precise estimates are difficult due to many variables. Finding a surgeon who focuses solely on gender confirmation surgery and has performed many of these procedures is a plus. Speaking to a surgeon's past patients can be a helpful way to gain insight on the physician's practices as well.

For those who follow through with these preparation steps, hormone treatment, and surgeries, studies show quality of life appears to improve. Many people who undergo these procedures express satisfaction with their results.

Bizic MR, Jeftovic M, Pusica S, et al. Gender dysphoria: Bioethical aspects of medical treatment . Biomed Res Int . 2018;2018:9652305. doi:10.1155/2018/9652305

American Psychiatric Association. What is gender dysphoria? . 2016.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people . 2012.

Tomlins L. Prescribing for transgender patients . Aust Prescr . 2019;42(1): 10–13. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2019.003

T'sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, Tangpricha V. Endocrinology of transgender medicine . Endocr Rev . 2019;40(1):97-117. doi:10.1210/er.2018-00011

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877-884. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Seal LJ. A review of the physical and metabolic effects of cross-sex hormonal therapy in the treatment of gender dysphoria . Ann Clin Biochem . 2016;53(Pt 1):10-20. doi:10.1177/0004563215587763

Schechter LS. Gender confirmation surgery: An update for the primary care provider . Transgend Health . 2016;1(1):32-40. doi:10.1089/trgh.2015.0006

Altman K. Facial feminization surgery: current state of the art . Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg . 2012;41(8):885-94. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2012.04.024

Therattil PJ, Hazim NY, Cohen WA, Keith JD. Esthetic reduction of the thyroid cartilage: A systematic review of chondrolaryngoplasty . JPRAS Open. 2019;22:27-32. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.07.002

Top H, Balta S. Transsexual mastectomy: Selection of appropriate technique according to breast characteristics . Balkan Med J . 2017;34(2):147-155. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.2016.0093

Chan W, Drummond A, Kelly M. Deep vein thrombosis in a transgender woman . CMAJ . 2017;189(13):E502-E504. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160408

Streed CG, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: A narrative review . Ann Intern Med . 2017;167(4):256-267. doi:10.7326/M17-0577

Hashemi L, Weinreb J, Weimer AK, Weiss RL. Transgender care in the primary care setting: A review of guidelines and literature . Fed Pract . 2018;35(7):30-37.

Van de grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming aurgery: A follow-up atudy . J Sex Marital Ther . 2018;44(2):138-148. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender confirmation surgeries .

American Psychological Association. Transgender people, gender identity, and gender expression .

Colebunders B, Brondeel S, D'Arpa S, Hoebeke P, Monstrey S. An update on the surgical treatment for transgender patients . Sex Med Rev . 2017 Jan;5(1):103-109. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.08.001

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing surgery

Feminizing surgery, also called gender-affirming surgery or gender-confirmation surgery, involves procedures that help better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing surgery includes several options, such as top surgery to increase the size of the breasts. That procedure also is called breast augmentation. Bottom surgery can involve removal of the testicles, or removal of the testicles and penis and the creation of a vagina, labia and clitoris. Facial procedures or body-contouring procedures can be used as well.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing surgery. These surgeries can be expensive, carry risks and complications, and involve follow-up medical care and procedures. Certain surgeries change fertility and sexual sensations. They also may change how you feel about your body.

Your health care team can talk with you about your options and help you weigh the risks and benefits.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Many people seek feminizing surgery as a step in the process of treating discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. The medical term for this is gender dysphoria.

For some people, having feminizing surgery feels like a natural step. It's important to their sense of self. Others choose not to have surgery. All people relate to their bodies differently and should make individual choices that best suit their needs.

Feminizing surgery may include:

- Removal of the testicles alone. This is called orchiectomy.

- Removal of the penis, called penectomy.

- Removal of the testicles.

- Creation of a vagina, called vaginoplasty.

- Creation of a clitoris, called clitoroplasty.

- Creation of labia, called labioplasty.

- Breast surgery. Surgery to increase breast size is called top surgery or breast augmentation. It can be done through implants, the placement of tissue expanders under breast tissue, or the transplantation of fat from other parts of the body into the breast.

- Plastic surgery on the face. This is called facial feminization surgery. It involves plastic surgery techniques in which the jaw, chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, and areas surrounding the eyes, ears or lips are changed to create a more feminine appearance.

- Tummy tuck, called abdominoplasty.

- Buttock lift, called gluteal augmentation.

- Liposuction, a surgical procedure that uses a suction technique to remove fat from specific areas of the body.

- Voice feminizing therapy and surgery. These are techniques used to raise voice pitch.

- Tracheal shave. This surgery reduces the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple.

- Scalp hair transplant. This procedure removes hair follicles from the back and side of the head and transplants them to balding areas.

- Hair removal. A laser can be used to remove unwanted hair. Another option is electrolysis, a procedure that involves inserting a tiny needle into each hair follicle. The needle emits a pulse of electric current that damages and eventually destroys the follicle.

Your health care provider might advise against these surgeries if you have:

- Significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Any condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

Like any other type of major surgery, many types of feminizing surgery pose a risk of bleeding, infection and a reaction to anesthesia. Other complications might include:

- Delayed wound healing

- Fluid buildup beneath the skin, called seroma

- Bruising, also called hematoma

- Changes in skin sensation such as pain that doesn't go away, tingling, reduced sensation or numbness

- Damaged or dead body tissue — a condition known as tissue necrosis — such as in the vagina or labia

- A blood clot in a deep vein, called deep vein thrombosis, or a blood clot in the lung, called pulmonary embolism

- Development of an irregular connection between two body parts, called a fistula, such as between the bladder or bowel into the vagina

- Urinary problems, such as incontinence

- Pelvic floor problems

- Permanent scarring

- Loss of sexual pleasure or function

- Worsening of a behavioral health problem

Certain types of feminizing surgery may limit or end fertility. If you want to have biological children and you're having surgery that involves your reproductive organs, talk to your health care provider before surgery. You may be able to freeze sperm with a technique called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before surgery, you meet with your surgeon. Work with a surgeon who is board certified and experienced in the procedures you want. Your surgeon talks with you about your options and the potential results. The surgeon also may provide information on details such as the type of anesthesia that will be used during surgery and the kind of follow-up care that you may need.

Follow your health care team's directions on preparing for your procedures. This may include guidelines on eating and drinking. You may need to make changes in the medicine you take and stop using nicotine, including vaping, smoking and chewing tobacco.

Because feminizing surgery might cause physical changes that cannot be reversed, you must give informed consent after thoroughly discussing:

- Risks and benefits

- Alternatives to surgery

- Expectations and goals

- Social and legal implications

- Potential complications

- Impact on sexual function and fertility

Evaluation for surgery

Before surgery, a health care provider evaluates your health to address any medical conditions that might prevent you from having surgery or that could affect the procedure. This evaluation may be done by a provider with expertise in transgender medicine. The evaluation might include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history

- A physical exam

- A review of your vaccinations

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections

- Discussion about birth control, fertility and sexual function

You also may have a behavioral health evaluation by a health care provider with expertise in transgender health. That evaluation might assess:

- Gender identity

- Gender dysphoria

- Mental health concerns

- Sexual health concerns

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings

- The role of social transitioning and hormone therapy before surgery

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved hormone therapy or supplements

- Support from family, friends and caregivers

- Your goals and expectations of treatment

- Care planning and follow-up after surgery

Other considerations

Health insurance coverage for feminizing surgery varies widely. Before you have surgery, check with your insurance provider to see what will be covered.

Before surgery, you might consider talking to others who have had feminizing surgery. If you don't know someone, ask your health care provider about support groups in your area or online resources you can trust. People who have gone through the process may be able to help you set your expectations and offer a point of comparison for your own goals of the surgery.

What you can expect

Facial feminization surgery.

Facial feminization surgery may involve a range of procedures to change facial features, including:

- Moving the hairline to create a smaller forehead

- Enlarging the lips and cheekbones with implants

- Reshaping the jaw and chin

- Undergoing skin-tightening surgery after bone reduction

These surgeries are typically done on an outpatient basis, requiring no hospital stay. Recovery time for most of them is several weeks. Recovering from jaw procedures takes longer.

Tracheal shave

A tracheal shave minimizes the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple. During this procedure, a small cut is made under the chin, in the shadow of the neck or in a skin fold to conceal the scar. The surgeon then reduces and reshapes the cartilage. This is typically an outpatient procedure, requiring no hospital stay.

Top surgery

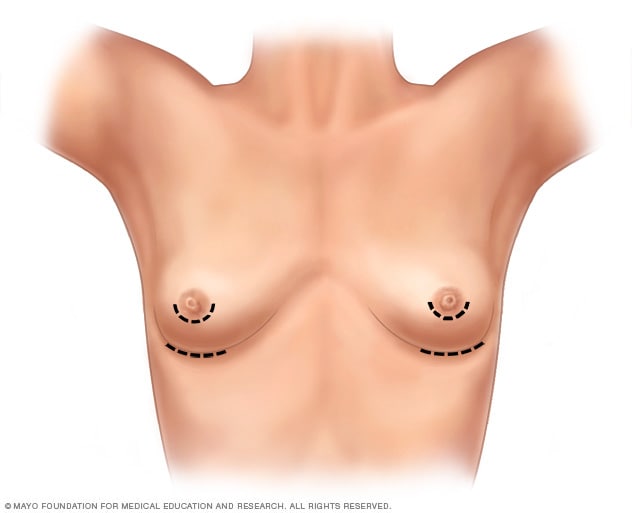

- Breast augmentation incisions

As part of top surgery, the surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast.

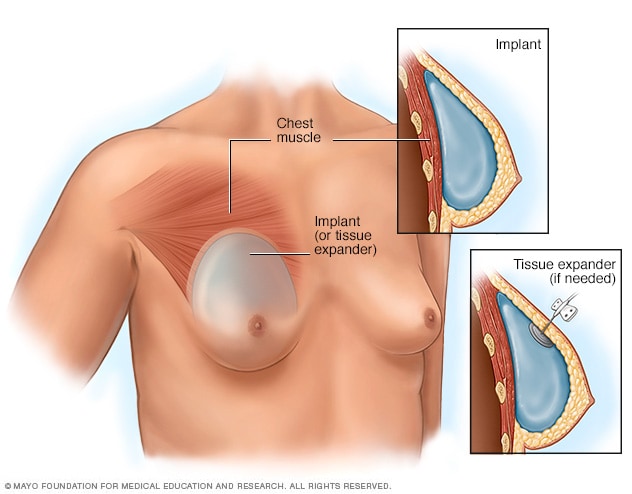

- Placement of breast implants or tissue expanders

During top surgery, the surgeon places the implants under the breast tissue. If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough, an initial surgery might be needed to have devices called tissue expanders placed in front of the chest muscles.

Hormone therapy with estrogen stimulates breast growth, but many people aren't satisfied with that growth alone. Top surgery is a surgical procedure to increase breast size that may involve implants, fat grafting or both.

During this surgery, a surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast. Next, silicone or saline implants are placed under the breast tissue. Another option is to transplant fat, muscles or tissue from other parts of the body into the breasts.

If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough for top surgery, an initial surgery may be needed to place devices called tissue expanders in front of the chest muscles. After that surgery, visits to a health care provider are needed every few weeks to have a small amount of saline injected into the tissue expanders. This slowly stretches the chest skin and other tissues to make room for the implants. When the skin has been stretched enough, another surgery is done to remove the expanders and place the implants.

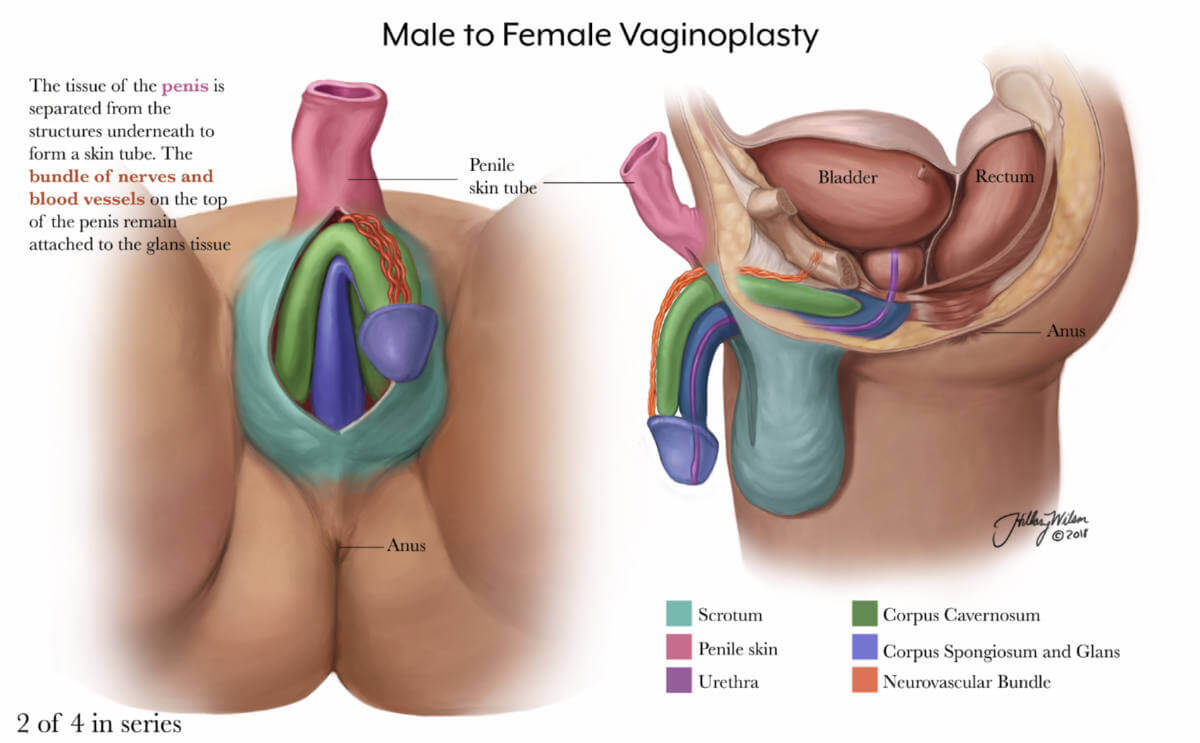

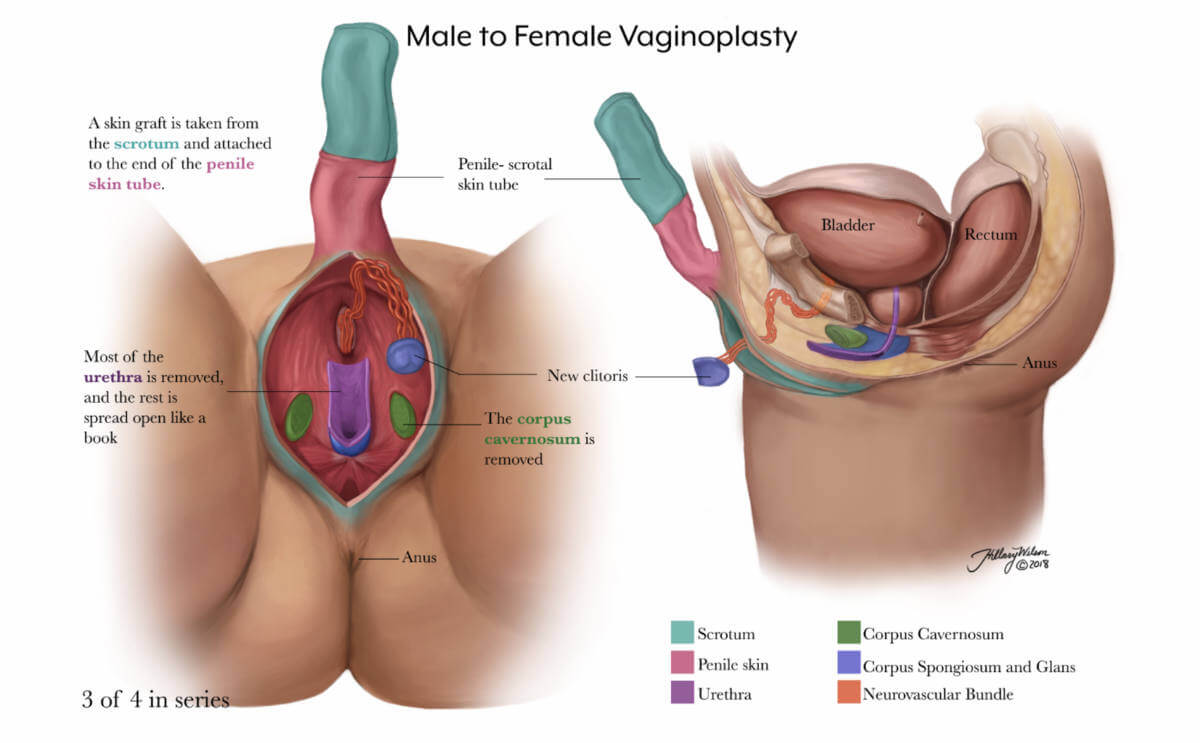

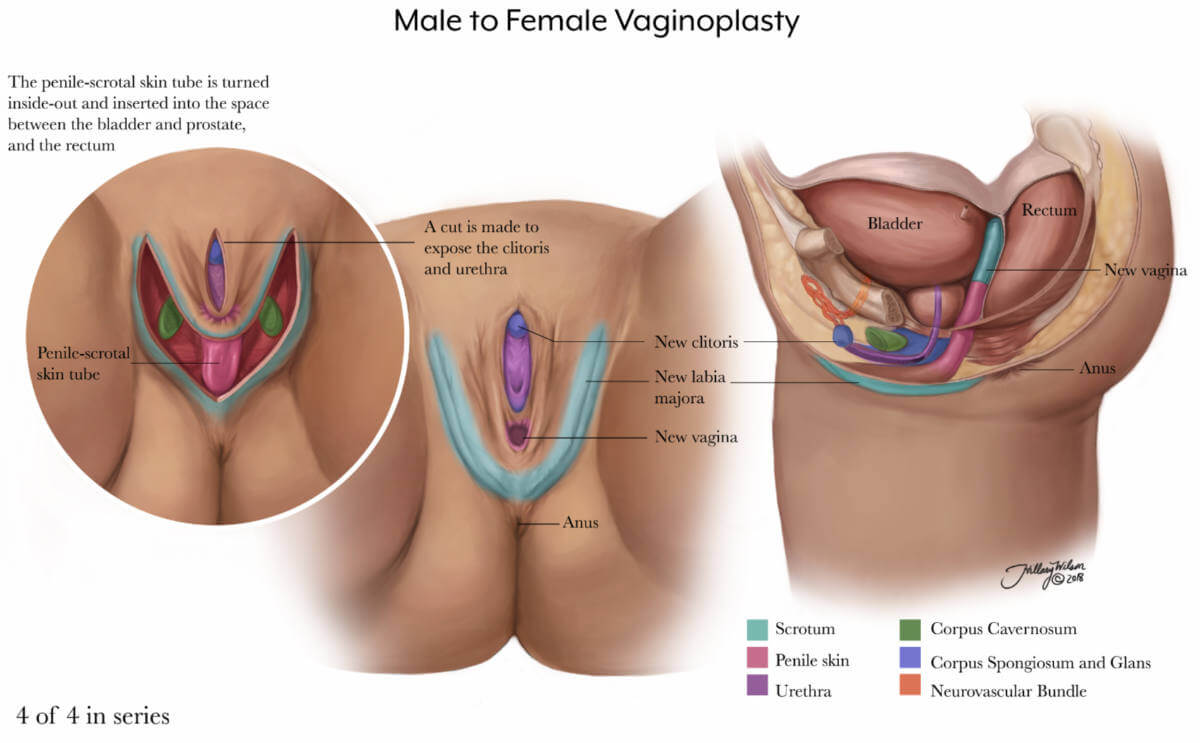

Genital surgery

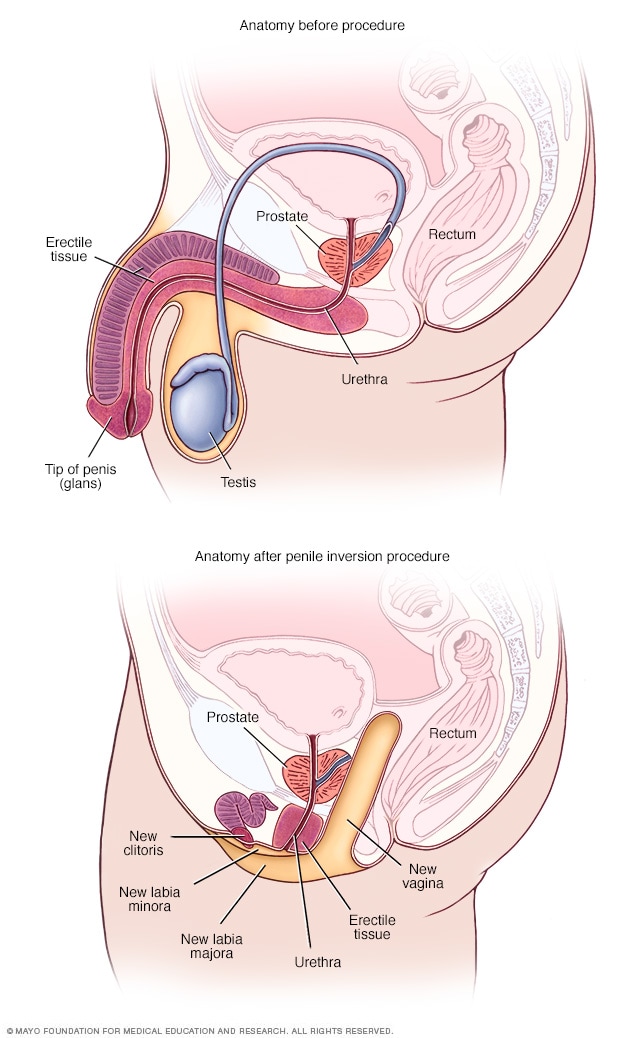

- Anatomy before and after penile inversion

During penile inversion, the surgeon makes a cut in the area between the rectum and the urethra and prostate. This forms a tunnel that becomes the new vagina. The surgeon lines the inside of the tunnel with skin from the scrotum, the penis or both. If there's not enough penile or scrotal skin, the surgeon might take skin from another area of the body and use it for the new vagina as well.

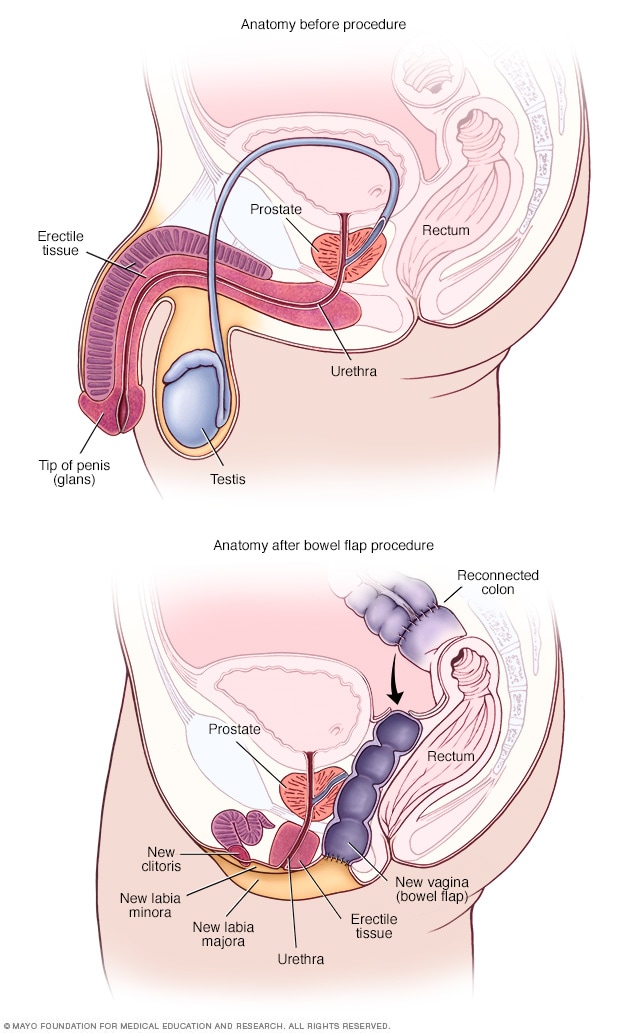

- Anatomy before and after bowel flap procedure

A bowel flap procedure might be done if there's not enough tissue or skin in the penis or scrotum. The surgeon moves a segment of the colon or small bowel to form a new vagina. That segment is called a bowel flap or conduit. The surgeon reconnects the remaining parts of the colon.

Orchiectomy

Orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles. Because testicles produce sperm and the hormone testosterone, an orchiectomy might eliminate the need to use testosterone blockers. It also may lower the amount of estrogen needed to achieve and maintain the appearance you want.

This type of surgery is typically done on an outpatient basis. A local anesthetic may be used, so only the testicular area is numbed. Or the surgery may be done using general anesthesia. This means you are in a sleep-like state during the procedure.

To remove the testicles, a surgeon makes a cut in the scrotum and removes the testicles through the opening. Orchiectomy is typically done as part of the surgery for vaginoplasty. But some people prefer to have it done alone without other genital surgery.

Vaginoplasty

Vaginoplasty is the surgical creation of a vagina. During vaginoplasty, skin from the shaft of the penis and the scrotum is used to create a vaginal canal. This surgical approach is called penile inversion. In some techniques, the skin also is used to create the labia. That procedure is called labiaplasty. To surgically create a clitoris, the tip of the penis and the nerves that supply it are used. This procedure is called a clitoroplasty. In some cases, skin can be taken from another area of the body or tissue from the colon may be used to create the vagina. This approach is called a bowel flap procedure. During vaginoplasty, the testicles are removed if that has not been done previously.

Some surgeons use a technique that requires laser hair removal in the area of the penis and scrotum to provide hair-free tissue for the procedure. That process can take several months. Other techniques don't require hair removal prior to surgery because the hair follicles are destroyed during the procedure.

After vaginoplasty, a tube called a catheter is placed in the urethra to collect urine for several days. You need to be closely watched for about a week after surgery. Recovery can take up to two months. Your health care provider gives you instructions about when you may begin sexual activity with your new vagina.

After surgery, you're given a set of vaginal dilators of increasing sizes. You insert the dilators in your vagina to maintain, lengthen and stretch it. Follow your health care provider's directions on how often to use the dilators. To keep the vagina open, dilation needs to continue long term.

Because the prostate gland isn't removed during surgery, you need to follow age-appropriate recommendations for prostate cancer screening. Following surgery, it is possible to develop urinary symptoms from enlargement of the prostate.

Dilation after gender-affirming surgery

This material is for your education and information only. This content does not replace medical advice, diagnosis and treatment. If you have questions about a medical condition, always talk with your health care provider.

Narrator: Vaginal dilation is important to your recovery and ongoing care. You have to dilate to maintain the size and shape of your vaginal canal and to keep it open.

Jessi: I think for many trans women, including myself, but especially myself, I looked forward to one day having surgery for a long time. So that meant looking up on the internet what the routines would be, what the surgery entailed. So I knew going into it that dilation was going to be a very big part of my routine post-op, but just going forward, permanently.

Narrator: Vaginal dilation is part of your self-care. You will need to do vaginal dilation for the rest of your life.

Alissa (nurse): If you do not do dilation, your vagina may shrink or close. If that happens, these changes might not be able to be reversed.

Narrator: For the first year after surgery, you will dilate many times a day. After the first year, you may only need to dilate once a week. Most people dilate for the rest of their life.

Jessi: The dilation became easier mostly because I healed the scars, the stitches held up a little bit better, and I knew how to do it better. Each transgender woman's vagina is going to be a little bit different based on anatomy, and I grew to learn mine. I understand, you know, what position I needed to put the dilator in, how much force I needed to use, and once I learned how far I needed to put it in and I didn't force it and I didn't worry so much on oh, did I put it in too far, am I not putting it in far enough, and I have all these worries and then I stress out and then my body tenses up. Once I stopped having those thoughts, I relaxed more and it was a lot easier.

Narrator: You will have dilators of different sizes. Your health care provider will determine which sizes are best for you. Dilation will most likely be painful at first. It's important to dilate even if you have pain.

Alissa (nurse): Learning how to relax the muscles and breathe as you dilate will help. If you wish, you can take the pain medication recommended by your health care team before you dilate.

Narrator: Dilation requires time and privacy. Plan ahead so you have a private area at home or at work. Be sure to have your dilators, a mirror, water-based lubricant and towels available. Wash your hands and the dilators with warm soapy water, rinse well and dry on a clean towel. Use a water-based lubricant to moisten the rounded end of the dilators. Water-based lubricants are available over-the-counter. Do not use oil-based lubricants, such as petroleum jelly or baby oil. These can irritate the vagina. Find a comfortable position in bed or elsewhere. Use pillows to support your back and thighs as you lean back to a 45-degree angle. Start your dilation session with the smallest dilator. Hold a mirror in one hand. Use the other hand to find the opening of your vagina. Separate the skin. Relax through your hips, abdomen and pelvic floor. Take slow, deep breaths. Position the rounded end of the dilator with the lubricant at the opening to your vaginal canal. The rounded end should point toward your back. Insert the dilator. Go slowly and gently. Think of its path as a gentle curving swoop. The dilator doesn't go straight in. It follows the natural curve of the vaginal canal. Keep gentle down and inward pressure on the dilator as you insert it. Stop when the dilator's rounded end reaches the end of your vaginal canal. The dilators have dots or markers that measure depth. Hold the dilator in place in your vaginal canal. Use gentle but constant inward pressure for the correct amount of time at the right depth for you. If you're feeling pain, breathe and relax the muscles. When time is up, slowly remove the dilator, then repeat with the other dilators you need to use. Wash the dilators and your hands. If you have increased discharge following dilation, you may want to wear a pad to protect your clothing.

Jessi: I mean, it's such a strange, unfamiliar feeling to dilate and to have a dilator, you know to insert a dilator into your own vagina. Because it's not a pleasurable experience, and it's quite painful at first when you start to dilate. It feels much like a foreign body entering and it doesn't feel familiar and your body kind of wants to get it out of there. It's really tough at the beginning, but if you can get through the first month, couple months, it's going to be a lot easier and it's not going to be so much of an emotional and uncomfortable experience.

Narrator: You need to stay on schedule even when traveling. Bring your dilators with you. If your schedule at work creates challenges, ask your health care team if some of your dilation sessions can be done overnight.

Alissa (nurse): You can't skip days now and do more dilation later. You must do dilation on schedule to keep vaginal depth and width. It is important to dilate even if you have pain. Dilation should cause less pain over time.

Jessi: I hear that from a lot of other women that it's an overwhelming experience. There's lots of emotions that are coming through all at once. But at the end of the day for me, it was a very happy experience. I was glad to have the opportunity because that meant that while I have a vagina now, at the end of the day I had a vagina. Yes, it hurts, and it's not pleasant to dilate, but I have the vagina and it's worth it. It's a long process and it's not going to be easy. But you can do it.

Narrator: If you feel dilation may not be working or you have any questions about dilation, please talk with a member of your health care team.

Research has found that gender-affirming surgery can have a positive impact on well-being and sexual function. It's important to follow your health care provider's advice for long-term care and follow-up after surgery. Continued care after surgery is associated with good outcomes for long-term health.

Before you have surgery, talk to members of your health care team about what to expect after surgery and the ongoing care you may need.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing surgery care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/ contents/search. Accessed Aug. 16, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Surgical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming procedures (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nahabedian, M. Implant-based breast reconstruction and augmentation. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Ferrando C, et al. Gender-affirming surgery: Male to female. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

- Search the site GO Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Mental Health

- Social and Public Health

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KP-Headshot-IMG_1661-0d48c6ea46f14ab19a91e7b121b49f59.jpg)

A gender affirmation surgery allows individuals, such as those who identify as transgender or nonbinary , to change one or more of their sex characteristics. This type of procedure offers a person the opportunity to have features that align with their gender identity.

For example, this type of surgery may be a transgender surgery like a male-to-female or female-to-male surgery. Read on to learn more about what masculinizing, feminizing, and gender-nullification surgeries may involve, including potential risks and complications.

Why Is Gender Affirmation Surgery Performed?

A person may have gender affirmation surgery for different reasons. They may choose to have the surgery so their physical features and functional ability align more closely with their gender identity.

For example, one study found that 48,019 people underwent gender affirmation surgeries between 2016 and 2020. Most procedures were breast- and chest-related, while the remaining procedures concerned genital reconstruction or facial and cosmetic procedures.

In some cases, surgery may be medically necessary to treat dysphoria. Dysphoria refers to the distress that transgender people may experience when their gender identity doesn't match their sex assigned at birth. One study found that people with gender dysphoria who had gender affirmation surgeries experienced:

- Decreased antidepressant use

- Decreased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

- Decreased alcohol and drug abuse

However, these surgeries are only performed if appropriate for a person's case. The appropriateness comes about as a result of consultations with mental health professionals and healthcare providers.

Transgender vs Nonbinary

Transgender and nonbinary people can get gender affirmation surgeries. However, there are some key ways that these gender identities differ.

Transgender is a term that refers to people who have gender identities that aren't the same as their assigned sex at birth. Identifying as nonbinary means that a person doesn't identify only as a man or a woman. A nonbinary individual may consider themselves to be:

- Both a man and a woman

- Neither a man nor a woman

- An identity between or beyond a man or a woman

Hormone Therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy uses sex hormones and hormone blockers to help align the person's physical appearance with their gender identity. For example, some people may take masculinizing hormones.

"They start growing hair, their voice deepens, they get more muscle mass," Heidi Wittenberg, MD , medical director of the Gender Institute at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco and director of MoZaic Care Inc., which specializes in gender-related genital, urinary, and pelvic surgeries, told Health .

Types of hormone therapy include:

- Masculinizing hormone therapy uses testosterone. This helps to suppress the menstrual cycle, grow facial and body hair, increase muscle mass, and promote other male secondary sex characteristics.

- Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogens and testosterone blockers. These medications promote breast growth, slow the growth of body and facial hair, increase body fat, shrink the testicles, and decrease erectile function.

- Non-binary hormone therapy is typically tailored to the individual and may include female or male sex hormones and/or hormone blockers.

It can include oral or topical medications, injections, a patch you wear on your skin, or a drug implant. The therapy is also typically recommended before gender affirmation surgery unless hormone therapy is medically contraindicated or not desired by the individual.

Masculinizing Surgeries

Masculinizing surgeries can include top surgery, bottom surgery, or both. Common trans male surgeries include:

- Chest masculinization (breast tissue removal and areola and nipple repositioning/reshaping)

- Hysterectomy (uterus removal)

- Metoidioplasty (lengthening the clitoris and possibly extending the urethra)

- Oophorectomy (ovary removal)

- Phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis )

- Scrotoplasty (surgery to create a scrotum)

Top Surgery

Chest masculinization surgery, or top surgery, often involves removing breast tissue and reshaping the areola and nipple. There are two main types of chest masculinization surgeries:

- Double-incision approach : Used to remove moderate to large amounts of breast tissue, this surgery involves two horizontal incisions below the breast to remove breast tissue and accentuate the contours of pectoral muscles. The nipples and areolas are removed and, in many cases, resized, reshaped, and replaced.

- Short scar top surgery : For people with smaller breasts and firm skin, the procedure involves a small incision along the lower half of the areola to remove breast tissue. The nipple and areola may be resized before closing the incision.

Metoidioplasty

Some trans men elect to do metoidioplasty, also called a meta, which involves lengthening the clitoris to create a small penis. Both a penis and a clitoris are made of the same type of tissue and experience similar sensations.

Before metoidioplasty, testosterone therapy may be used to enlarge the clitoris. The procedure can be completed in one surgery, which may also include:

- Constructing a glans (head) to look more like a penis

- Extending the urethra (the tube urine passes through), which allows the person to urinate while standing

- Creating a scrotum (scrotoplasty) from labia majora tissue

Phalloplasty

Other trans men opt for phalloplasty to give them a phallic structure (penis) with sensation. Phalloplasty typically requires several procedures but results in a larger penis than metoidioplasty.

The first and most challenging step is to harvest tissue from another part of the body, often the forearm or back, along with an artery and vein or two, to create the phallus, Nicholas Kim, MD, assistant professor in the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery in the department of surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, told Health .

Those structures are reconnected under an operative microscope using very fine sutures—"thinner than our hair," said Dr. Kim. That surgery alone can take six to eight hours, he added.

In a separate operation, called urethral reconstruction, the surgeons connect the urinary system to the new structure so that urine can pass through it, said Dr. Kim. Urethral reconstruction, however, has a high rate of complications, which include fistulas or strictures.

According to Dr. Kim, some trans men prefer to skip that step, especially if standing to urinate is not a priority. People who want to have penetrative sex will also need prosthesis implant surgery.

Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy

Masculinizing surgery often includes the removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and ovaries (oophorectomy). People may want a hysterectomy to address their dysphoria, said Dr. Wittenberg, and it may be necessary if their gender-affirming surgery involves removing the vagina.

Many also opt for an oophorectomy to remove the ovaries, almond-shaped organs on either side of the uterus that contain eggs and produce female sex hormones. In this case, oocytes (eggs) can be extracted and stored for a future surrogate pregnancy, if desired. However, this is a highly personal decision, and some trans men choose to keep their uterus to preserve fertility.

Feminizing Surgeries

Surgeries are often used to feminize facial features, enhance breast size and shape, reduce the size of an Adam’s apple , and reconstruct genitals. Feminizing surgeries can include:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization surgery

- Penis removal (penectomy)

- Scrotum removal (scrotectomy)

- Testicle removal (orchiectomy)

- Tracheal shave (chondrolaryngoplasty) to reduce an Adam's apple

- Vaginoplasty

- Voice feminization

Breast Augmentation

Top surgery, also known as breast augmentation or breast mammoplasty, is often used to increase breast size for a more feminine appearance. The procedure can involve placing breast implants, tissue expanders, or fat from other parts of the body under the chest tissue.

Breast augmentation can significantly improve gender dysphoria. Studies show most people who undergo top surgery are happier, more satisfied with their chest, and would undergo the surgery again.

Most surgeons recommend 12 months of feminizing hormone therapy before breast augmentation. Since hormone therapy itself can lead to breast tissue development, transgender women may or may not decide to have surgical breast augmentation.

Facial Feminization and Adam's Apple Removal

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is a series of plastic surgery procedures that reshape the forehead, hairline, eyebrows, nose, cheeks, and jawline. Nonsurgical treatments like cosmetic fillers, botox, fat grafting, and liposuction may also be used to create a more feminine appearance.

Some trans women opt for chondrolaryngoplasty, also known as a tracheal shave. The procedure reduces the size of the Adam's apple, an area of cartilage around the larynx (voice box) that tends to be larger in people assigned male at birth.

Vulvoplasty and Vaginoplasty

As for bottom surgery, there are various feminizing procedures from which to choose. Vulvoplasty (to create external genitalia without a vagina) or vaginoplasty (to create a vulva and vaginal canal) are two of the most common procedures.

Dr. Wittenberg noted that people might undergo six to 12 months of electrolysis or laser hair removal before surgery to remove pubic hair from the skin that will be used for the vaginal lining.

Surgeons have different techniques for creating a vaginal canal. A common one is a penile inversion, where the masculine structures are emptied and inverted into a created cavity, explained Dr. Kim. Vaginoplasty may be done in one or two stages, said Dr. Wittenberg, and the initial recovery is three months—but it will be a full year until people see results.

Surgical removal of the penis or penectomy is sometimes used in feminization treatment. This can be performed along with an orchiectomy and scrotectomy.

However, a total penectomy is not commonly used in feminizing surgeries . Instead, many people opt for penile-inversion surgery, a technique that hollows out the penis and repurposes the tissue to create a vagina during vaginoplasty.

Orchiectomy and Scrotectomy

An orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles —male reproductive organs that produce sperm. Scrotectomy is surgery to remove the scrotum, that sac just below the penis that holds the testicles.

However, some people opt to retain the scrotum. Scrotum skin can be used in vulvoplasty or vaginoplasty, surgeries to construct a vulva or vagina.

Other Surgical Options

Some gender non-conforming people opt for other types of surgeries. This can include:

- Gender nullification procedures

- Penile preservation vaginoplasty

- Vaginal preservation phalloplasty

Gender Nullification

People who are agender or asexual may opt for gender nullification, sometimes called nullo. This involves the removal of all sex organs. The external genitalia is removed, leaving an opening for urine to pass and creating a smooth transition from the abdomen to the groin.

Depending on the person's sex assigned at birth, nullification surgeries can include:

- Breast tissue removal

- Nipple and areola augmentation or removal

Penile Preservation Vaginoplasty

Some gender non-conforming people assigned male at birth want a vagina but also want to preserve their penis, said Dr. Wittenberg. Often, that involves taking skin from the lining of the abdomen to create a vagina with full depth.

Vaginal Preservation Phalloplasty

Alternatively, a patient assigned female at birth can undergo phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis) and retain the vaginal opening. Known as vaginal preservation phalloplasty, it is often used as a way to resolve gender dysphoria while retaining fertility.

The recovery time for a gender affirmation surgery will depend on the type of surgery performed. For example, healing for facial surgeries may last for weeks, while transmasculine bottom surgery healing may take months.

Your recovery process may also include additional treatments or therapies. Mental health support and pelvic floor physiotherapy are a few options that may be needed or desired during recovery.

Risks and Complications

The risk and complications of gender affirmation surgeries will vary depending on which surgeries you have. Common risks across procedures could include:

- Anesthesia risks

- Hematoma, which is bad bruising

- Poor incision healing

Complications from these procedures may be:

- Acute kidney injury

- Blood transfusion

- Deep vein thrombosis, which is blood clot formation

- Pulmonary embolism, blood vessel blockage for vessels going to the lung

- Rectovaginal fistula, which is a connection between two body parts—in this case, the rectum and vagina

- Surgical site infection

- Urethral stricture or stenosis, which is when the urethra narrows

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Wound disruption

What To Consider

It's important to note that an individual does not need surgery to transition. If the person has surgery, it is usually only one part of the transition process.

There's also psychotherapy . People may find it helpful to work through the negative mental health effects of dysphoria. Typically, people seeking gender affirmation surgery must be evaluated by a qualified mental health professional to obtain a referral.

Some people may find that living in their preferred gender is all that's needed to ease their dysphoria. Doing so for one full year prior is a prerequisite for many surgeries.

All in all, the entire transition process—living as your identified gender, obtaining mental health referrals, getting insurance approvals, taking hormones, going through hair removal, and having various surgeries—can take years, healthcare providers explained.

A Quick Review

Whether you're in the process of transitioning or supporting someone who is, it's important to be informed about gender affirmation surgeries. Gender affirmation procedures often involve multiple surgeries, which can be masculinizing, feminizing, or gender-nullifying in nature.

It is a highly personalized process that looks different for each person and can often take several months or years. The procedures also vary regarding risks and complications, so consultations with healthcare providers and mental health professionals are essential before having these procedures.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender affirmation surgeries .

Wright JD, Chen L, Suzuki Y, Matsuo K, Hershman DL. National estimates of gender-affirming surgery in the US . JAMA Netw Open . 2023;6(8):e2330348-e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8 . Int J Transgend Health . 2022;23(S1):S1-S260. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Chou J, Kilmer LH, Campbell CA, DeGeorge BR, Stranix JY. Gender-affirming surgery improves mental health outcomes and decreases anti-depressant use in patients with gender dysphoria . Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open . 2023;11(6 Suppl):1. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000944280.62632.8c

Human Rights Campaign. Get the facts on gender-affirming care .

Human Rights Campaign. Transgender and non-binary people FAQ .

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877–84. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Richards JE, Hawley RS. Chapter 8: Sex Determination: How Genes Determine a Developmental Choice . In: Richards JE, Hawley RS, eds. The Human Genome . 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2011: 273-298.

Randolph JF Jr. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender females . Clin Obstet Gynecol . 2018;61(4):705-721. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396

Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal treatment strategies tailored to non-binary transgender individuals . J Clin Med . 2020;9(6):1609. doi:10.3390/jcm9061609

Van Boerum MS, Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R, Agarwal C. Chest and facial surgery for the transgender patient . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):219-227. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.18

Djordjevic ML, Stojanovic B, Bizic M. Metoidioplasty: techniques and outcomes . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):248–53. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.12

Bordas N, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Szanto A, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty: surgical options and outcomes in 813 cases . Front Endocrinol . 2021;12:760284. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.760284

Al-Tamimi M, Pigot GL, van der Sluis WB, et al. The surgical techniques and outcomes of secondary phalloplasty after metoidioplasty in transgender men: an international, multi-center case series . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2019;16(11):1849-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.027

Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, et al. Urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery . J Sex Med . 2021;18(7):1271–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.023

Nikolavsky D, Hughes M, Zhao LC. Urologic complications after phalloplasty or metoidioplasty . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):425–35. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.013

Nota NM, den Heijer M, Gooren LJ. Evaluation and treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender incongruent adults . In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext . MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Carbonnel M, Karpel L, Cordier B, Pirtea P, Ayoubi JM. The uterus in transgender men . Fertil Steril . 2021;116(4):931–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.005

Miller TJ, Wilson SC, Massie JP, Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Breast augmentation in male-to-female transgender patients: Technical considerations and outcomes . JPRAS Open . 2019;21:63-74. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.03.003

Claes KEY, D'Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest surgery for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):369–80. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.010

De Boulle K, Furuyama N, Heydenrych I, et al. Considerations for the use of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures for facial remodeling in transgender individuals . Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol . 2021;14:513-525. doi:10.2147/CCID.S304032

Asokan A, Sudheendran MK. Gender affirming body contouring and physical transformation in transgender individuals . Indian J Plast Surg . 2022;55(2):179-187. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1749099

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-thyroid cartilage reduction . Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2019;27(2):267–72. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005

Chen ML, Reyblat P, Poh MM, Chi AC. Overview of surgical techniques in gender-affirming genital surgery . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):191-208. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.19

Wangjiraniran B, Selvaggi G, Chokrungvaranont P, Jindarak S, Khobunsongserm S, Tiewtranon P. Male-to-female vaginoplasty: Preecha's surgical technique . J Plast Surg Hand Surg . 2015;49(3):153-9. doi:10.3109/2000656X.2014.967253

Okoye E, Saikali SW. Orchiectomy . In: StatPearls [Internet] . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Salgado CJ, Yu K, Lalama MJ. Vaginal and reproductive organ preservation in trans men undergoing gender-affirming phalloplasty: technical considerations . J Surg Case Rep . 2021;2021(12):rjab553. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab553

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after facial feminization surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after transmasculine bottom surgery?

de Brouwer IJ, Elaut E, Becker-Hebly I, et al. Aftercare needs following gender-affirming surgeries: findings from the ENIGI multicenter European follow-up study . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2021;18(11):1921-1932. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.005

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transfeminine bottom surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transmasculine top surgery?

Khusid E, Sturgis MR, Dorafshar AH, et al. Association between mental health conditions and postoperative complications after gender-affirming surgery . JAMA Surg . 2022;157(12):1159-1162. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3917

Related Articles

- A to Z Guides

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

Surgery to change the appearance of your body is a common choice for all kinds of people. There are many reasons that people might want to alter their appearance. For transgender or gender nonconforming people, making changes to their bodies is a way of affirming their identity.

A trans person can choose from multiple procedures to make their appearance match their self-identified gender identity. Doctors refer to this as gender "affirmation" surgery.

Trans people might decide to have surgery on their chest, genitals, or face. These surgeries are personal decisions, and each person makes their own choices about what is right for them.

Learn more about gender affirmation surgery and how it helps trans people.

What Does It Mean to Be Transgender or Nonbinary?

Transgender is a word to describe people whose gender identity or gender expression doesn't match the sex they were assigned at birth. Typically, parents and doctors assume a baby's gender based on the appearance of their genitals. But some people grow up and realize that their sense of who they are isn't aligned with how their bodies look. These people are considered transgender.

Trans people may identify as a different gender than what they were assigned at birth. For example, a child assigned male at birth may identify as female. Nonbinary people don't identify as either male or female. They may refer to themselves as "nonbinary" or "genderqueer."

There are many options for trans and nonbinary people to change their appearance so that how they look reflects who they are inside. Many trans people use clothing, hairstyles, or makeup to present a particular look. Some use hormone therapy to refine their secondary sex characteristics. Some people choose surgery that can change their bodies and faces permanently.

Facial Surgery

Facial plastic surgery is popular and accessible for all kinds of people in the U.S. It is not uncommon to have a nose job or a facelift . Cosmetic surgery is great for improving self-esteem and making people feel more like themselves. Trans people can use plastic surgery to adjust the shape of their faces to better reflect their gender identity.

Facial feminization. A person with a masculine face can have surgeries to make their face and neck look more feminine. These can be done in one procedure or through multiple operations. They might ask for:

- Forehead contouring

- Jaw reduction

- Chin surgery

- Hairline advancement

- Cheek augmentation

- Rhinoplasty

- Lip augmentation

- Adam's apple reduction

Facial masculinization. Someone with a feminine face can have surgery to make their face look more masculine. The doctor may do all the procedures at one time or plan multiple surgeries. Doctors usually offer:

- Forehead lengthening

- Jaw reshaping

- Chin contouring

- Adam's apple enhancement

Top Surgery

Breast surgeries are very common in America. The shorthand for breast surgeries is "top surgery." All kinds of people have operations on their breasts , and there are a lot of doctors who can do them. The surgeries that trans people have to change their chests are very similar to typical breast enhancement or breast removal operations.

Transfeminine. When a trans person wants a more feminine bustline, that's called transfeminine top surgery. It involves placing breast implants in a person's chest. It's the same operation that a doctor might do to enlarge someone's breasts or for breast reconstruction .

Transmasculine. Transmasculine top surgery is when a person wants a more masculine chest shape. It is similar to a mastectomy . The doctor removes the breast tissue to flatten the whole chest. The doctor can also contour the skin and reposition the nipples to look more like a typical man's chest.

Bottom Surgery

For people who want to change their genitals, some operations can do that. That is sometimes called bottom surgery. Those are complicated procedures that require doctors with a lot of experience with trans surgeries.

Transmasculine bottom surgery. Some transmasculine people want to remove their uterus and ovaries. They can choose to have a hysterectomy to do that. This reduces the level of female hormones in their bodies and stops their menstrual cycles.

If a person wants to change their external genitals, they can ask for surgery to alter the vaginal opening. A surgeon can also construct a penis for them. There are several techniques for doing this.

Metoidioplasty uses the clitoris and surrounding skin to create a phallus that can become erect and pass urine. A phalloplasty requires grafting skin from another part of the body into the genital region to create a phallus. People can also have surgery to make a scrotum with implants that mimic testicles.

Transfeminine bottom surgery. People who want to reduce the level of male hormones in their bodies may choose to have their testicles removed. This is called an orchiectomy and can be done as an outpatient operation.

Vaginoplasty is an operation to construct a vagina . Doctors use the tissue from the penis and invert it into a person's pelvic area. The follow-up after a vaginoplasty involves using dilators to prevent the new vaginal opening from closing back up.

How Much Does Gender Affirmation Surgery Cost?

Some medical insurance companies will cover some or most parts of your gender-affirming surgery. But many might have certain "exclusions" listed in the plan. They might use language like "services related to sex change" or "sex reassignment surgery." These limitations may vary by state. It's best to reach out to your insurance company by phone or email to confirm the coverage or exclusions.

If your company does cover some costs, they may need a few documents before they approve it.

This can include:

- A gender dysphoria diagnosis in your health records. It's a term used to describe the feeling you have when the sex you're assigned at birth does not match with your gender identity. A doctor can provide a note if it's necessary.

- A letter of support from a mental health professional such as a social worker, psychiatrist , or a therapist.

Gender affirmation surgery can be very expensive. It's best to check with your insurance company to see what type of coverage you have.

If you're planning to pay out-of-pocket, prices may vary depending on the various specialists involved in your case. This can include surgeons, primary care doctors, anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and counselors. The procedure costs also vary, and the total bill will include a number of charges, including hospital stay, anesthesia, counseling sessions, medications, and the procedures you elect to have.

Whether you choose facial, top, or bottom or a combination of these procedures, the total bill after your hospital stay can cost anywhere from $5,400 for chin surgery to well over $100,000 for multiple procedures.

Recovery and Mental Health After Gender Affirmation Surgery

Your recovery time may vary. It will depend on the type of surgery you have. But swelling can last anywhere from 2 weeks for facial surgery to up to 4 months or more if you opted for bottom surgery.

Talk to your doctor about when you can get back to your normal day-to-day routine. But in the meantime, make sure to go to your regular follow-up appointments with your doctor. This will help them make sure you're healing well post-surgery.

Most trans and nonbinary people who get gender affirmation surgery report that it improves their overall quality of life. In fact, over 94% of people who opt for surgery say they are satisfied with the results.

Folks who have mental health support before surgery tend to do better, too. One study found that after gender affirmation surgery, a person's need for mental health treatment went down by 8%.

Not all trans and nonbinary people choose to have gender affirmation surgery, or they may only have some of the procedures available. If you are considering surgery, speak with your primary care doctor to discuss what operations might be best for you.

Top doctors in ,

Find more top doctors on, related links.

- Health A-Z News

- Health A-Z Reference

- Health A-Z Slideshows

- Health A-Z Quizzes

- Health A-Z Videos

- WebMDRx Savings Card

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis C

- Diabetes Warning Signs

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Morning-After Pill

- Breast Cancer Screening

- Psoriatic Arthritis Symptoms

- Heart Failure

- Multiple Myeloma

- Types of Crohn's Disease

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 16 May 2017

An overview of female-to-male gender-confirming surgery

- Shane D. Morrison 1 ,

- Mang L. Chen 2 &

- Curtis N. Crane 2

Nature Reviews Urology volume 14 , pages 486–500 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

2728 Accesses

66 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Reconstruction

- Sexual behaviour

Gender-confirming surgery is becoming a more frequently encountered procedure for urologists, plastic surgeons, and gynaecologists

Female-to-male gender-confirming surgery consists of facial masculinization, chest masculinization, body contouring, and genital surgery

Metoidioplasty (hypertrophy with systemic hormones and mobilization of the clitoris with urethroplasty) can produce a sensate microphallus

Phalloplasty can produce an aesthetic and sensate phallus with ability to micturate in a standing position and engage in penetrative sexual intercourse if proper nerve coaptation and prosthetic insertion are performed

Urethral complications following genital surgery in transmen are generally higher than 30% and include urethral fistulas and strictures; revisional urethroplasty can address most urethral complications following genital surgery

Advances in basic sciences, transgender-specific prostheses, and patient-reported outcomes will continue to offer options for improvements in gender-confirming surgery

Gender dysphoria is estimated to occur in approximately 25 million people worldwide, and can have severe psychosocial sequelae. Medical and surgical gender transition can substantially improve quality-of-life outcomes for individuals with gender dysphoria. Individuals seeking to undergo female-to-male (FtM) transition have various surgical options available for gender confirmation, including facial and chest masculinization, body contouring, and genital surgery. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines should be met before the patient undergoes surgery, to ensure that gender-confirming surgery is appropriate and indicated. Chest masculinization and metoidioplasty or phalloplasty are the most common procedures pursued, and both generally result in high levels of patient satisfaction. Phalloplasty, with a resultant aesthetic and sensate phallus along with implantable prosthetic, can take upwards of a year to accomplish, and is associated with a considerable risk of complications. Urethral complications are most frequent, and can be addressed with revision procedures. A number of scaffolds, implants, and prostheses are now in development to improve outcomes in FtM patients.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Male-to-female gender affirmation surgery: breast reconstruction with Ergonomix round prostheses

Overview on metoidioplasty: variants of the technique

Masculinizing genital gender-affirming surgery: metoidioplasty and urethral lengthening

World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. 7th Version (World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2011). Standards of care for transgender and gender nonconforming patients to assist all providers caring for patients within this population.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Benjamin, H. The Transsexual Phenomenon (Julian Press, 1966).

Google Scholar

Byne, W. et al . Report of the American Psychiatric Association task force on treatment of gender identity disorder. Arch. Sex. Behav. 41 , 759–796 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dhejne, C. et al . Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: cohort study in Sweden. PLoS ONE 6 , e16885 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dhejne, C., Oberg, K., Arver, S. & Landen, M. An analysis of all applications for sex reassignment surgery in Sweden, 1960-2010: prevalence, incidence, and regrets. Arch. Sex. Behav. 43 , 1535–1545 (2014).

Lawrence, A. A. Gender assignment dysphoria in the DSM-5. Arch. Sex. Behav. 43 , 1263–1266 (2014).

Leiter, E., Futterweit, W. & Brown, G. R. in Reconstructive Urology Vol. 2 (eds Webster, G., Kirby, R., King, L. & Goldwasser, B.) 921–932 (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1993).

Winter, S. et al . Transgender people: health at the margins of society. Lancet 388 , 390–400 (2016). Evaluation of the difficulties experienced by transgender patients in seeking healthcare.

Wylie, K. et al . Serving transgender people: clinical care considerations and service delivery models in transgender health. Lancet 388 , 401–411 (2016).

Gooren, L. J. Clinical practice. Care of transsexual persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 364 , 1251–1257 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Deutsch, M. B. et al . Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 20 , 700–703 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Morrison, S. D. The care transition in plastic surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 136 , 861e–862e (2015).

Morrison, S. D. & Swanson, J. W. Surgical justice. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 136 , 291e–292e (2015).

De Cuypere, G., Elaut, E. & Heylens, G. Long-term follow-up: psychosocial outcome of Belgian transsexuals after sex reassignment surgery. Sexologies 15 , 126–133 (2006).

Article Google Scholar

De Cuypere, G. et al . Sexual and physical health after sex reassignment surgery. Arch. Sex. Behav. 34 , 679–690 (2005).

Hage, J. J. & Karim, R. B. Ought GIDNOS get nought? Treatment options for nontranssexual gender dysphoria. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105 , 1222–1227 (2000).

Lawrence, A. A. Sexuality before and after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch. Sex. Behav. 34 , 147–166 (2005).

Wierckx, K. et al . Sexual desire in female-to-male transsexual persons: exploration of the role of testosterone administration. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 165 , 331–337 (2011).

Wierckx, K. et al . Sexual desire in trans persons: associations with sex reassignment treatment. J. Sex. Med. 11 , 107–118 (2014). Evaluation of the sexual desires experienced by transgender patients after gender-confirming surgery.

Wierckx, K. et al . Long-term evaluation of cross-sex hormone treatment in transsexual persons. J. Sex. Med. 9 , 2641–2651 (2012).

Wierckx, K. et al . Quality of life and sexual health after sex reassignment surgery in transsexual men. J. Sex. Med. 8 , 3379–3388 (2011).

Zaker-Shahrak, A., Chio, L. W., Isaac, R. & Tescher, J. Economic impact assessment: Gender nondiscrimination in health insurance. (ed. Department of Insurance) (State of California, 2012).

Monstrey, S. et al . Surgical therapy in transsexual patients: a multi-disciplinary approach. Acta Chir. Belg. 101 , 200–209 (2001).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Selvaggi, G., Dhejne, C., Landen, M. & Elander, A. The 2011 WPATH standards of care and penile reconstruction in female-to-male transsexual individuals. Adv. Urol. 2012 , 581712 (2012).

Gooren, L. J. Management of female-to-male transgender persons: medical and surgical management, life expectancy. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 21 , 233–238 (2014).

Davis, S. R. et al . Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N. Engl. J. Med. 359 , 2005–2017 (2008).

Gooren, L. J. & Giltay, E. J. Review of studies of androgen treatment of female-to-male transsexuals: effects and risks of administration of androgens to females. J. Sex. Med. 5 , 765–776 (2008).

Gooren, L. J., Giltay, E. J. & Bunck, M. C. Long-term treatment of transsexuals with cross-sex hormones: extensive personal experience. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93 , 19–25 (2008).

Mueller, A. & Gooren, L. Hormone-related tumors in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 159 , 197–202 (2008).

Van Caenegem, E. et al . Bone mass, bone geometry, and body composition in female-to-male transsexual persons after long-term cross-sex hormonal therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 , 2503–2511 (2012).

Monstrey, S. J., Ceulemans, P. & Hoebeke, P. Sex reassignment surgery in the female-to-male transsexual. Semin. Plast. Surg. 25 , 229–244 (2011).

Morrison, S. D., Perez, M. G., Carter, C. K. & Crane, C. N. Pre- and post-operative care with associated intra-operative techniques for phalloplasty in female-to-male patients. Urol. Nurs. 35 , 134–138 (2015).

Morrison, S. D., Perez, M. G., Nedelman, M. & Crane, C. N. Current state of female-to-male gender confirming surgery. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 7 , 38–48 (2015).

Selvaggi, G. & Bellringer, J. Gender reassignment surgery: an overview. Nat. Rev. Urol. 8 , 274–282 (2011).

Morrison, S. D. et al . Educational exposure to transgender patient care in plastic surgery training. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 138 , 944–953 (2016). Evaluation of resident exposure to transgender patient care in plastic surgery.

Obedin-Maliver, J. et al . Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 306 , 971–977 (2011).

Dy, G. W. et al . Exposure to and attitudes regarding transgender education among urology residents. J. Sex. Med. 13 , 1466–1472 (2016). Evaluation of resident exposure to transgender patient care in urology.

Morrison, S. D. et al . Facial feminization: systematic review of the literature. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 137 , 1759–1770 (2016).

Ousterhout, D. K. Dr. Paul Tessier and facial skeletal masculinization. Ann. Plast. Surg. 67 , S10–S15 (2011).

Deschamps-Braly, J. C., Sacher, C. L., Fick, J. & Ousterhout, D. K. First female-to-male facial confirmation surgery with description of a new procedure for masculinization of the thyroid cartilage (Adam's apple). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 139 , 883e–887e (2017). First report of facial masculinization in transmen.

Monstrey, S. et al . Chest-wall contouring surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: a new algorithm. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 121 , 849–859 (2008). Algorithmic approach to chest wall masculinization.

Richards, C. & Barrett, J. The case for bilateral mastectomy and male chest contouring for the female-to-male transsexual. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 95 , 93–95 (2013).

Berry, M. G., Curtis, R. & Davies, D. Female-to-male transgender chest reconstruction: a large consecutive, single-surgeon experience. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 65 , 711–719 (2012).

Colic, M. M. & Colic, M. M. Circumareolar mastectomy in female-to-male transsexuals and large gynecomastias: a personal approach. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 24 , 450–454 (2000).

Nelson, L., Whallett, E. J. & McGregor, J. C. Transgender patient satisfaction following reduction mammaplasty. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 62 , 331–334 (2009).

Vukadinovic, V., Stojanovic, B., Majstorovic, M. & Milosevic, A. The role of clitoral anatomy in female to male sex reassignment surgery. ScientificWorldJournal 2014 , 437378 (2014).

Weyers, S. et al . Gynaecological aspects of the treatment and follow-up of transsexual men and women. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn. 2 , 35–54 (2010).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ergeneli, M. H., Duran, E. H., Ozcan, G. & Erdogan, M. Vaginectomy and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy as adjunctive surgery for female-to-male transsexual reassignment: preliminary report. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 87 , 35–37 (1999).

Weyers, S., Selvaggi, G. & Monstrey, S. Two-stage versus one-stage sex reassignment surgery in female-to-male transsexual individuals. Gynecol. Surg. 3 , 190–194 (2006).