- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Online learning.

- Lisa Marie Blaschke Lisa Marie Blaschke Carl von Ossietzky University

- and Svenja Bedenlier Svenja Bedenlier Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.674

- Published online: 30 April 2020

With the ubiquity of the Internet and the pedagogical opportunities that digital media afford for education on all levels, online learning constitutes a form of education that accommodates learners’ individual needs beyond traditional face-to-face instruction, allowing it to occur with the student physically separated from the instructor. Online learning and distance education have entered into the mainstream of educational provision at of most of the 21st century’s higher education institutions.

With its consequent focus on the learner and elements of course accessibility and flexibility and learner collaboration, online learning renegotiates the meaning of teaching and learning, positioning students at the heart of the process and requiring new competencies for successful online learners as well as instructors. New teaching and learning strategies, support structures, and services are being developed and implemented and often require system-wide changes within higher education institutions.

Drawing on central elements from the field of distance education, both in practice and in its theoretical foundations, online learning makes use of new affordances of a variety of information and communication technologies—ranging from multimedia learning objects to social and collaborative media and entire virtual learning environments. Fundamental learning theories are being revisited and discussed in the context of online learning, leaving room for their further development and application in the digital age.

- online learning

- online distance education

- digital media

- learning theory

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 06 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 November 2023

Students’ online learning adaptability and their continuous usage intention across different disciplines

- Zheng Li 1 ,

- Xiaodong Lou 2 ,

- Minwei Chen 3 ,

- Siyu Li 1 ,

- Cixian Lv 4 ,

- Shuting Song 4 &

- Linlin Li 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 838 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3228 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Online learning, as a pivotal element in modern education, is introducing fresh demands and challenges to the established teaching norms across various subjects. The adaptability of students to online learning and their sustained willingness to engage with it constitute two pivotal factors influencing the effective operation of online education systems. The dynamic relationship between these aspects may manifest unique traits within different academic disciplines, yet comprehensive research in this area remains notably scarce. In light of this, this study constructs an Adaptive Structural Learning and Technology Acceptance Model (ASL-TAM) with satisfaction towards online teaching as the mediating variable to investigate the impact and mechanism of online learning adaptivity on continuous usage intention for students from different disciplines. A total of 11,832 undergraduate students from 334 universities in 12 disciplinary categories in mainland China were selected, and structural equation modeling was used for analysis. The results showed that the ASL-TAM model could be fitted for all 12 disciplines. The perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and system environment adaptability dimensions of online learning adaptivity significantly and positively affect satisfaction towards online teaching and continuous usage intention. Satisfaction towards online teaching partially mediates the relationship between online learning adaptivity and continuous usage intention. There were significant differences in the results of the single-factor analysis of the observed variables for the 12 disciplines, and the path coefficients in the ASL-TAM model fitted for each discipline were also significantly different. Compared to the six disciplines under the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) category, six disciplines under the humanities category exhibited more significant internal differences in the results of the single-factor analysis of perceived usefulness and the path coefficients for satisfaction towards online teaching. This research seeks to bridge existing research gaps and provide novel guidance and recommendations for the personalized design and distinctive implementation of online learning platforms and courses across various academic disciplines.

Similar content being viewed by others

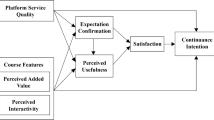

Research on the influencing factors of adult learners' intent to use online education platforms based on expectation confirmation theory

Adoption of blended learning: Chinese university students’ perspectives

The unified theory of acceptance and use of DingTalk for educational purposes in China: an extended structural equation model

Introduction.

With the rapid development of information technology, online learning has become an integral part of modern education. China possesses the largest scale of higher education system and online learning course system globally (National Bureau of Statistics ( 2020 )). However, despite the widespread adoption of online learning platforms, there remain controversies surrounding students’ engagement, satisfaction, and willingness to continue using them. Therefore, researching how to enhance students’ willingness to persist in using online learning platforms is of paramount importance for the development and promotion of online learning. In recent years, scholars have increasingly focused on the factor of students’ online learning adaptability when studying the effectiveness of online learning for students and their willingness to continue using online platforms.

Prior studies have indicated that the overall level of adaptability to online learning among college students is relatively low (Luo, Huang ( 2012 )), and adaptability often becomes a critical factor determining the quality of learning and academic assessment in an online learning environment (D’errico et al., ( 2018 )). However, there is currently insufficient research evidence to fully understand the specific mechanisms through which online learning adaptability affects willingness to persist in using online platforms, necessitating further empirical research.

Moreover, given the extensive use and profound influence of online learning technologies in diverse academic fields (Chikwa et al., ( 2015 )), alongside the marked disparities in online learning outcomes across these disciplines (Ieta et al., ( 2011 )), delving into the intricate interplay between students’ online learning adaptability and their inclination to persist in using these tools across various domains becomes particularly instructive. It can provide valuable insights for crafting precise and efficacious online learning strategies and pedagogical models aimed at enhancing student learning outcomes and bolstering students’ satisfaction with online education.

As such, this study aims to investigate the impact of online learning adaptability on the willingness to persist in using online platforms among students from different disciplines while exploring the potential mediating effect of their satisfaction towards online teaching. This study randomly selected 11,832 valid samples from 256,504 students attending online learning in 12 disciplines across 334 universities in mainland China. Using structural equation modeling, the study analyzed the comprehensive impact of students’ online learning adaptability on their continued use intention of online learning. The study also analyzed the possible mediating effects of satisfaction towards online teaching among the 12 disciplinary categories in the “Degree Granting and Talent Training Discipline Catalog” issued by the Ministry of Education of China.

Theoretical foundation and research hypotheses

Adaptive online learning and continuance intention and their influencing factors.

Continuous usage intention is originated from the tracking and evaluation of the continuous use of software programs. It refers to the user’s decision to continue using a software application and the frequency of use based on the overall perception of the application. Continuous usage intention is one of the most important user indicators for judging the software system’s life cycle. This study applies this factor in the context of online learning research, and forms the concept of “continuance intention of online learning,” which is defined as learners’ intentions to continue choosing online learning as the primary learning method. This study seeks to determine whether students are willing to continue using this type of learning after a certain period of time.

In contrast to Daumiller et al. ( 2021 ), who suggest that teachers’ goals and attitudes have a critical impact on students’ continuance intention to use online learning, Yao et al. ( 2022 ) believe that the key factor affecting continued use of online learning is students’ self-awareness, which is closely related to their adaptability to online learning. Online learning adaptability refers to students’ ability to adapt to the learning environment by adjusting their learning strategies and adopting adaptive behaviors when using online learning platforms or systems. In the 1980s, Davis ( 1986 ) drew on the Theory of Reasoned Action to propose the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). TAM is primarily used to predict the extent to which individuals are inclined to accept, use, or reject new information technologies (Rogers, 2005 ). Given that online learning adaptability can help students overcome difficulties and challenges in the learning process, increasing their acceptance and depth of use of online learning, students’ adaptability to online learning platforms or systems is likely to be one of the important factors influencing their decision to continue using online platforms.

Online learning adaptability is a complex, multidimensional concept. Generally, it is considered the ability of students to adjust their learning strategies, behaviors, attitudes, goal setting, and resource utilization to adapt to new learning conditions and requirements (Kizilcec et al., 2015 ). This includes adaptability in areas such as technical proficiency, self-management skills, and information literacy. Among these, the adaptability of university students to online learning primarily depends on their familiarity with the technology tools they use. Therefore, mastering online learning platforms, social media, and digital tools can enhance students’ adaptability to online learning (Selwyn, 2011 ). Additionally, in terms of instructional design, the design of online courses has a significant impact on students’ adaptability. Clear learning objectives, organized content, and diverse teaching methods contribute to improving students’ adaptability (Picciano, 2017 ). Providing effective technical support and assistance channels can alleviate students’ technological difficulties and enhance their adaptability to online learning (Johnson & Adams, 2011 ).

In analyzing the issues of online learning adaptability and acceptance, TAM provides several foundational factors, such as perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and self-efficacy (Cakır, Solak ( 2015 )). Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are generally considered the two most essential variables (Martins et al., 2014 ). Perceived usefulness refers to the degree to which users believe that using a particular information technology enhances their work efficiency, while perceived ease of use refers to users’ perception of how easy it is to operate a specific information technology (Davis, 1989 ). Alharbi and Drew ( 2014 ) argue that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness in the TAM model significantly positively influence students’ intentions to use online learning. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

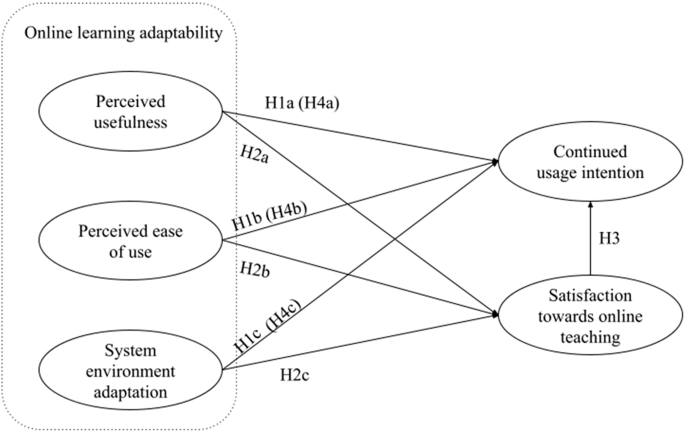

H1a: The perceived usefulness dimension of online learning adaptability has a positive significant impact on students’ continued usage intention.

H1b: The perceived ease of use dimension of online learning adaptability has a positive significant impact on students’ continued usage intention.

Apart from perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, there is still no consensus on other important factors influencing continuance intention, especially regarding the strength and mechanisms of different factors (Joo et al., 2011 ). Liu et al. ( 2010 ) suggests that reasonable external extension variables can effectively predict users’ intentions to use online learning. Bazelais et al. ( 2018 ) and Xu, Lv ( 2022 ) also propose considering the additional effects of external influencing variables in the study of continuance intention. As a frontier and hot topic in online learning research (Jovanovic, Jovanovic ( 2015 )), the theory of Adaptive Learning Systems (ALS) from cognitive psychology proposes the concept of “human-machine interaction adaptability,” which includes two aspects: human adaptation to technology and technology adaptation to humans. The latter relies on the “learner model” to automatically analyze learners’ cognitive levels and learning styles, and then feedback to the former to enhance learners’ learning progress and effectiveness (Retalis, Papasalouros ( 2005 )). Social Cognitive Theory also suggests a similar viewpoint, indicating that students’ adaptability is largely influenced by multiple social contexts. A substantial amount of research on ALS also demonstrates that ALS, as a scientific learning medium, can more actively meet students’ learning needs (How, Hung ( 2019 )), help correct the learning paths generated by students’ autonomous learning habits (Nihad et al., ( 2017 )), and effectively improve students’ learning adaptability (Zulfiani et al., ( 2018 )). This study believes that online learning adaptability is a comprehensive, two-way process for students to adapt to changes in the learning environment through self-perception and for software systems to adapt to user needs systematically. It includes three variables: perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and system environment adaptability, with the latter referring to the functional adaptability of learning software systems to different learning styles of learners. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1c: The system environment adaptation dimension of online learning adaptability has a positive significant impact on students’ continued usage intention.

Satisfaction towards online teaching and its possible mediating role

Prior research has suggested that satisfaction towards online teaching and perceived usefulness are considered core components in evaluating the effectiveness of online learning (Menon, Seow ( 2021 )), as they relate to the quality of online courses and students’ performance (Kuo et al., 2014 ). Scholars attach great importance to the research on the relationship between students’ satisfaction towards online teaching and their continued usage intention, with satisfaction being considered a key element affecting students’ continued usage intention and behavior (Lee, 2010 ).

Among the potential factors contributing to positive adaptability in online learning, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are recognized as two significant factors affecting satisfaction (Huang, 2020 ). Additionally, factors influencing satisfaction can indirectly impact the intention to continue using the system (Bhattacherjee, 2001 ). Furthermore, online educational platforms with robust system adaptability can provide a more stable network connection, higher-quality learning resources, and a more diverse array of learning pathways. Moreover, they can deliver personalized learning support and teaching resources tailored to individual student needs and learning characteristics. This assists students in overcoming learning challenges and enhances teaching effectiveness, ultimately leading to greater teaching satisfaction. Notably, technological innovations introduced by ALS effectively enhance learners’ perceived quality and have a positive indirect influence on teaching satisfaction (Janati et al., ( 2018 )). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: The perceived usefulness dimension of online learning adaptability positively and significantly affects students’ satisfaction towards online teaching.

H2b: The perceived ease of use dimension of online learning adaptability positively and significantly affects students’ satisfaction towards online teaching.

H2c: The system environment adaptation dimension of online learning adaptability positively and significantly affects students’ satisfaction towards online teaching.

It is generally believed that students’ satisfaction towards online teaching can refer to the indicator system proposed by the research on satisfaction towards classroom teaching, comprehensively evaluating common teaching factors such as course design, learning objectives, teaching methods, teacher qualifications, and interactive experiences. Palmer, Holt ( 2010 ) believe that the research on students’ satisfaction towards online teaching should pay more attention to the unique factors of the online teaching environment, such as teaching interactivity, technical proficiency, and online self-assessment. Bolliger and Wasilik ( 2009 ) also believes that we should start from the key participants in the online environment, focusing on the impact of various aspects such as teachers’ information technology application, students’ communication level, and school policy and logistical support. Kurucay and Inan ( 2017 ) opine that the key factor influencing online learning effectiveness is the interaction between learners. Regarding the main factors influencing learners’ satisfaction towards online teaching, Kranzow ( 2013 ) believe that the essential factors are related to teacher’s online course design level and the ability to respond to student needs in a timely manner. Hogan and McKnight ( 2007 ) believe that factors such as the teaching environment and technical support are the main reasons for influencing satisfaction towards online teaching. In addition, there are significant differences in the predicting factors for the acceptance of online learning and satisfaction towards online teaching among university students from different countries (Piccoli et al., 2001 ). Based on the above research, this study will further analyze the factors influencing learners’ satisfaction towards online teaching in the online learning environment, and propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Students’ satisfaction towards online teaching positively affects their continued usage intention.

Previous studies have shown that students’ satisfaction towards online teaching is likely to be influenced by their learning adaptability, and at the same time affects their intention to continue attending online learning (Waheed, 2010 ). Therefore, students’ satisfaction towards online teaching may play a special mediating role between students’ learning adaptability and their continuance intention. Yeung and Jordan ( 2007 ) found that factors such as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and service quality evaluation that affect online learning satisfaction also have a positive impact on students’ continuance intention. Young ( 2013 ) reached similar conclusions and believed that students’ satisfaction towards online teaching plays a mediating role in the process of affecting their continuance intention. However, there are also different views about this topic. For example, Troshani et al. ( 2011 ) found that although perceived ease of use has a significant impact on learners’ usage satisfaction, it does not have a significant impact on their continuance intention. Therefore, the mediating effect of learning adaptability on learners’ continuance intention may be extremely important and needs to be verified through empirical research. Therefore, this study proposes that students’ satisfaction towards online teaching plays a mediating role between their online learning adaptability and continued usage intention. The specific hypotheses are as follows.

H4a: Students’ satisfaction towards online teaching plays a mediating role between perceived usefulness and their continued usage intention.

H4b: Students’ satisfaction towards online teaching plays a mediating role between perceived ease of use and their continued usage intention.

H4c: Students’ satisfaction towards online teaching plays a mediating role between system environment adaptability and their continued usage intention.

Designing the model framework

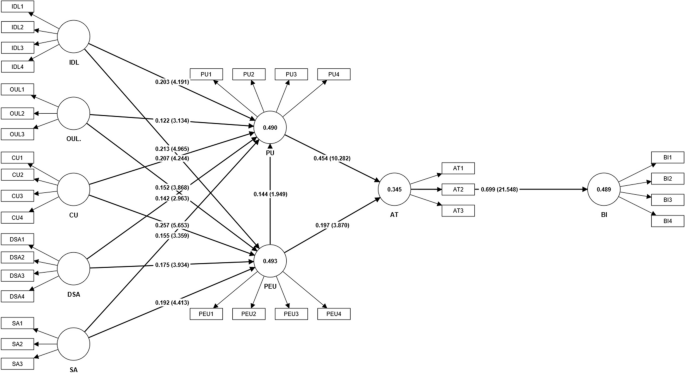

As mentioned earlier, it is feasible to use the TAM model to study the sustained usage intention of online learning, and its explanatory power has been verified by empirical studies (Dziuban et al., 2013 ). However, with the increasing complexity of the online environment, the traditional TAM model may encounter issues with low reliability and validity in explaining complex user environments. Therefore, the academic community has been continuously selecting, combining, and adjusting the basic components of the TAM model. Davis et al. ( 1992 ) pointed out that when using TAM theory, multiple external variables, including intrinsic motivation, should be considered, as they may have complex effects on endogenous variables and behavioral intentions. Farahat ( 2012 ) found that, in addition to perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, student attitudes and social influences in online learning are also important factors that influence students’ willingness to engage in online learning. Therefore, based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Adaptive Structural Learning Model (ALS), this study combines them to construct the Adaptive Learning and Technology Acceptance Model (ASL-TAM model; see Fig. 1 ) as follows:

In ASL-TAM model, online learning adaptability consists of three factors, which are hypothesized to predict continued usage intention and satisfaction towards online teaching.

Methodology

Data source.

The data for this study were collected from an online learning survey conducted by a Teacher Development Centre of a public university (IRB No. NB-HEC-20200328L) in mainland China from 2020 to 2021. The survey was distributed to students through the academic affairs offices of various schools. Additionally, two lie-detection questions were included in the questionnaire to ensure the validity and reliability of the data. Each student account could only save one survey form. In other words, if the same account answered multiple times, the results of the last response would automatically overwrite the previous ones. A total of 256,504 data sets were collected from 334 universities. Among the surveyed students, there were 110,411 males (43%) and 146,093 females (57%). In terms of geographical distribution, 110,919 students (43.2%) were from the eastern region of China, 106,007 (41.3%) were from the central region, and 38,847 (15.1%) were from the western region. The surveyed students were also classified into different academic disciplines, including 11,086 in philosophy, 20,953 in economics, 7420 in law, 17,100 in education, 24,658 in literature, 1201 in history, 29,517 in natural science, 76,301 in engineering, 5295 in agriculture, 11,161 in medicine, 24,583 in management, and 27,229 in arts. A sample of 1000 student questionnaires was randomly selected from each academic discipline, resulting in a total of 12,000 data sets. The sample was cleaned based on criteria such as lie-detection questions, response times (data below 5 min or above 20 min were removed based on the statistical “3σ rule”), age (data below 15 years old or above 25 years old were removed based on the statistical “3σ rule”), school names (data with randomly filled school names were removed), and whether online learning was used (data indicating no usage were removed). In total, 162 samples were cleaned, resulting in 11,832 valid samples (with 986 for each of the 12 academic disciplines).

Instrumentation

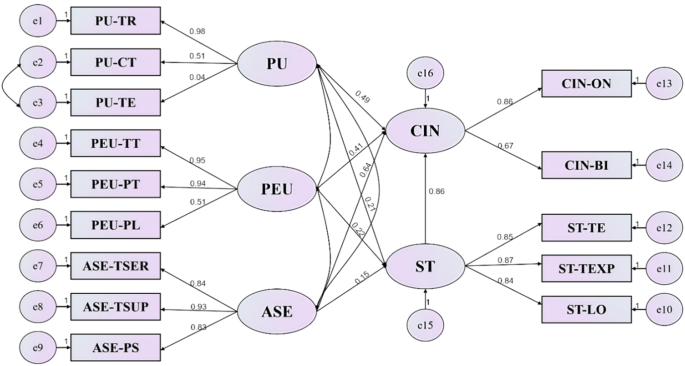

This study was conceptualized based on TAM from the theory of rational behavior and the ALS theory from cognitive psychology. These theories were employed to investigate the underlying mechanisms of the impact of online learning adaptability on users’ continuance intention. In this regard, we consulted the research findings of scholars such as Davis ( 1993 ), Igbaria ( 1990 ), Ajzen & Fishbein ( 1980 ), Chen and Tseng ( 2012 ), among others. The questionnaire consisted of 33 items measuring five variables (see Table S1 for the complete questionnaire): perceived usefulness (11 items), perceived ease of use (3 items), adjustment to system environments (10 items), satisfaction of teaching (7 items), and continuance intention (2 items). The overall reliability of the questionnaire was tested using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.924), KMO (0.937), and Bartlett’s sphericity test ( p < 0.001) in SPSS 25.0 software, indicating that the questionnaire data were reliable and suitable for exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Three principal components were extracted for perceived usefulness (PU): teaching resources (PU_TR), classroom teaching (PU_CT), and teaching evaluation (PU_TE). Three principal components were also extracted for perceived ease of use (PEU): technical training (PEU_TT), pedagogical training (PEU_PT), and proficiency levels (PEU_PL). Three principal components were extracted for system environment adaptation (SEA): technical service (SEA_TSER), teaching support (SEA_TSUP), and policy support (SEA_PS). Three principal components were extracted for satisfaction with online teaching (ST): effectiveness of teaching (ST_TE), teaching experience (ST_TEXP), and learning outcomes (ST_LO). Two principal components were extracted for continuance intention (CIN): online mode (CIN_ON) and blended mode (CIN_BL). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and system environment adaptation were combined to form the independent variable “adaptive structural learning (ASL)” in this study, while satisfaction towards online teaching was the hypothesized mediating variable and continuance intention was the dependent variable. The academic disciplines were treated as control variables. The perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use scales were adapted from Davis ( 1993 ), the system environment adaptation scale was adapted from Igbaria ( 1990 ), the satisfaction towards online teaching scale was adapted from Ajzen and Fishbein ( 1980 ), and the continuance intention scale was adapted from Chen and Tseng ( 2012 ).

Research method

Descriptive statistics were conducted on the data of 12 disciplines using SPSS 25.0 software, and model construction, model revision, and model interpretation were carried out using AMOS 24.0.

Reliability analysis

Reliability analysis was conducted on the 14 latent variables across the 12 disciplines using SPSS 25.0 software (see Table 1 for results). The results showed that the alpha values of the observation variables based on standardized items were all greater than or equal to 0.9, indicating that the questionnaire of the 12 disciplines had high reliability. During reliability analysis, the scores of the latent variables calculated using the mean method also had considerable reliability, indicating excellent data reliability. The data of the 12 disciplines were suitable for further structural model testing.

Common method bias (CMB) test

The data used in this study were collected through self-reporting methods on the internet, which may have CMB. Before formal data analysis, a Harman single-factor test was conducted to examine common method bias. First, exploratory factor analysis (unrotated) was performed using SPSS 25.0 software. The results showed that the first principal component accounted for 29.21% of the variance, which did not meet the 40% threshold.

One-way ANOVA of disciplinary variables

One-way ANOVA analysis was conducted on the observation variables of 12 disciplines. According to the results in Table 2 , if the 12 disciplines are viewed as a whole, the evaluation of perceived ease of use (3.62) is higher than system environment adaptation (3.60) and perceived usefulness (3.47). The satisfaction towards online teaching (3.47) is higher than continuous usage intention (3.44). Perceived usefulness is the main weak link of online learning adaptability, and the main observation variable that causes the low value of perceived usefulness is teaching evaluation (3.26). The lowest discipline evaluation value comes from philosophy (3.41). The observation variable with the lowest evaluation value in perceived ease of use is technical training (3.58), and the observation variable with the lowest evaluation value in system environment adaptation is technical service (3.53). The observation variable with the lowest evaluation value in the satisfaction towards online teaching is effectiveness of teaching (3.28). All 14 observation variables of the 12 disciplines showed significant inter-group differences ( p < 0.001), indicating that there were general differences in the evaluation outcomes among the observation variables of different disciplines.

Correlation analysis among variables

To explore the relationships between the variables, a correlation analysis was performed. As shown in Table 3 , there were significant positive correlations ( p < 0.001) between the variables of perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and system environment adaptation. There were also significant positive correlations ( p < 0.001) between the variables of perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and system environment adaptation with the mediating variables of satisfaction towards online teaching and continued usage intention. Additionally, there was a significant positive correlation ( p < 0.001) between satisfaction towards online teaching and continued usage intention.

Model construction and fitting

Based on the ASL-TAM model developed in Fig. 1 , a structural equation model was constructed using AMOS 24.0 software, and the initial model was estimated using maximum likelihood. Taking the subject of physics as an example, the results of the initial model fit showed that the correction index MI value of the residual path [e2 < -->e3] was relatively large. Therefore, the initial model was corrected by adding the [e2 < -->e3] residual path, and all path p -values were less than 0.05 after the correction, indicating statistical significance. The fitted model is shown in Fig. 2 .

The validated ASL-TAM model for the subject of physics demonstrated good fit, with most hypotheses being substantiated.

The fitted model for the subject of physics showed good results. The same fitting method was used for the other 11 subjects, and the results showed that all 12 models could be fitted, and the 12 fitting goodness-of-fit indices were within the standard range. Therefore, the ASL-TAM model can be used for relevant evaluation and prediction work (see Table 4 for goodness-of-fit indices).

Path analysis results of fitted models

The path coefficients of the structural equation can reflect the mutual relationships between latent variables and between latent variables and observed variables. The path coefficients between variables after the fitting of the 12 subjects are shown in Table 5 . First, the ASL-TAM models of all 12 subjects can achieve overall convergence. The path coefficients of satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) on continuous usage intention (CIN) are all significant in all 12 subjects, verifying research hypothesis H3. Second, the three paths “perceived ease of use (PEU) → continuous usage intention (CIN)”, “perceived usefulness (PU) → continuous usage intention (CIN)”, and “system environment adaptation (SEA) → continuous usage intention (CIN)” all display significant path coefficients and can be fitted into the ASL-TAM model, indicating that online learning adaptability and its three dimensions all have a significant positive impact on continuous usage intention (CIN), substantiating research hypotheses H1, H1a, H1b, and H1c. Third, the three paths “perceived ease of use (PEU) → satisfaction towards online teaching (ST)”, “perceived usefulness (PU) → satisfaction towards online teaching (ST)”, and “system environment adaptation (SEA) → satisfaction towards online teaching (ST)” all display significant path coefficients, indicating that online learning adaptability and its three dimensions all have a significant positive impact on satisfaction towards online teaching (ST), verifying research hypotheses H2, H2a, H2b, and H2c. Additionally, the path “Satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) → continuous usage intention (CIN)” is displayed with a significant path coefficient in all 12 subjects, indicating that “satisfaction towards online teaching (ST)” has a partial mediating effect between “perceived ease of use (PEU)”, “perceived usefulness (PU)”, “system environment adaptation (SEA)” and “continuous usage intention (CIN)”, verifying research hypotheses H4, H4a, H4b, and H4c.

This study confirms the positive impact of online learning adaptability on users’ intention to continue using the platform. This aligns with previous research findings that students’ adaptation to a course significantly affects their learning outcomes (Manwaring et al., 2017 ). Unlike most studies that only focus on students’ one-way adaptation to the teaching system, this study confirms that both students’ “perceived adaptation” to the system and the system’s “adaptive needs” to the students are equally important and should be considered as a whole. When students’ perceived position in the system matches the target characteristics predicted by the system, they will rate the teaching activities higher (Bretschneider et al., 2012 ).

This study also confirms the positive impact of online learning adaptability on satisfaction towards online teaching, which is in line with previous research that adaptability is an important indicator of students’ learning satisfaction, perceived utility, and intention to continue learning (Machado, Meirelles ( 2015 )). Therefore, adaptability should be the logical starting point for designing online learning systems. At the same time, enhancing the intelligence perception of “human-computer interaction” and improving the teaching adaptivity of “teacher-student interaction” are important directions for enhancing users’ intention to continue using online learning and improving the overall quality of online learning.

This study also confirms the positive impact of satisfaction towards online teaching on users’ intention to continue using the platform, and the TAM model is applicable in evaluating satisfaction and intention to continue using in 12 subject areas. The adaptive structural learning and technology acceptance model fit successfully in all 12 subject areas. This confirms that the TAM model can be used to explain the factors that influence learners’ acceptance of online learning (Venkatesh, Davis ( 2000 )), and the core structure of TAM has a significant impact on users’ intention to continue using (Natasia et al., 2022 ).

Furthermore, this study confirms that satisfaction towards online teaching partially mediates the relationship between online learning adaptability and users’ intention to continue using the platform. The ASL-TAM model developed in this study reveals that there are expression differences in the factors that affect satisfaction towards online teaching and users’ intention to continue using in the 12 subject areas, and the ASL-TAM model can explore the deep path reasons for the expression differences in the factors affecting users’ intention to continue using (Al-Azawei, Lundqvist ( 2015 )), and then analyze the educational goals and methods paths for implementing online learning in different subjects.

This study has three contributions. First, the study found that perceived usefulness (PU) (3.47) was lower than system environment adaptation (SEA) (3.60) and perceived ease of use (PEU) (3.62). The continuous usage intention (CIN) (3.44) was lower than satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) (3.47). The main observed variables leading to a low evaluation of perceived usefulness (PU) were teaching evaluation (PU_TE) (3.26) while the lowest evaluated variable in perceived ease of use (PEU) was technology training (PEU_TT) (3.58). In system environment adaptation (SEA), the lowest evaluated variable was technical service (SEA_TSER) (3.53) while the lowest evaluated variable in satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) was teaching effectiveness (ST_TE) (3.28). This indicates that online education in mainland China is still in the early stage of hardware facilities configuration and teaching technology training. The continuous usage intention (CIN) is generally weak, possibly due to the weak links in the early adaptation to online learning, which affects the evaluation of satisfaction towards online teaching (ST), leading to a weaker overall continuous usage intention (CIN). Online learning needs more specific and effective project support (Ramadhan et al., 2021 ).

Second, the study confirms that satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) plays a partial or complete mediating effect between perceived ease of use (PEU), perceived usefulness (PU), system environment adaptation (SEA) and continuous usage intention (CIN), which confirms previous research conclusions. That is, user satisfaction is a key antecedent to influence user intention to continue use and behavior (Igbaria et al., 1997 ). There are many possible factors that influence continuous usage intention (CIN) of a teaching method, but among various factors, satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) of the student population is the “central factor”, especially for online education, learner satisfaction is considered a key factor for teaching success (Joo et al., 2011 ). It is also important to strengthen system environment adaptation (SEA) based on human-computer interaction, as online learning requires an attractive and motivational external environment (Agyeiwaah et al., 2022 ), and satisfaction may vary due to internet experience (Reed, 2001 ).

Thirdly, this study confirms the significant differences in satisfaction towards online teaching (ST) and continuous usage intention (CIN) between STEM and humanities disciplines. Influenced by the early college entrance examination system, China has conventionally classified disciplines into STEM and humanities, similar to the “arts” and “science” branches in the subject guidelines of Western universities. The classification not only affects the disciplines but also results in significant differences in academic literacy among students in different fields. This study found that compared to STEM disciplines (such as natural science, engineering, agriculture, medicine, and management), the six traditional humanities disciplines, namely philosophy, law, education, literature, history, and economics, showed extremely significant differences in perceived usefulness (PU), which may be due to the difference in teaching style between humanities and STEM (Tuimur et al., 2012 ) and the peer cultural influence within the humanities. A study of nearly 500,000 online courses in the state of Washington in the United States has similar conclusions that students face greater difficulties in online learning in fields like English and social sciences, possibly due to the existence of “negative peer effects” in the online courses of these disciplines (Lv et al., 2022 ).

Implications

In order to enhance the satisfaction towards online teaching and continued usage intention of online education, this study proposes the following suggestions:

From the perspective of cognitive psychology, the differences in online teaching among different disciplines are mainly manifested in various aspects such as the cognitive perspectives and learning habits of students with different disciplinary backgrounds. From the standpoint of educational technology theory, there is a need for continuous development of multidimensional and multilevel teaching systems to adapt to the knowledge structures, teaching principles, and curriculum characteristics of different disciplines. Furthermore, constructivist learning theory emphasizes that teachers should assist students in improving their learning adaptability more actively and in constructing knowledge and meaning more proactively. This study empirically validates the above viewpoints and provides new discoveries. Research shows that there are significant differences in satisfaction towards online teaching and continued usage intention in online learning among different subjects, so different online learning for different subjects should be implemented. On the one hand, the convergence of online learning in different subjects should be grasped, and a wide-caliber, widely applicable teaching platform carrier should be constructed to effectively integrate different subject knowledge into the virtual classroom knowledge situation, and better promote the integration of knowledge and skills. On the other hand, attention should be paid to the objective differences of different subjects, and an online education system reflecting the advantages of different subjects should be designed according to the teaching contents of different subjects.

From the perspective of practicality, it is necessary to pay close attention to the significant differences among various disciplines in terms of subject content and learning objectives, teaching methods and learning activities, assessment and feedback methods, as well as the roles of teachers and technological support. It is important to actively develop teaching methods that are tailored to different disciplines, especially in the case of experimental courses. Compared with traditional classroom education, the important breakthrough of online learning is the more convenient and timely teaching feedback. Future online learning systems should create adaptive learning environments based on the different characteristics of learners (Park and Lee, 2003 ), and accelerate the construction of adaptive learning systems for college students with different learning methods in different subjects, which is an effective solution to the conflict between diversified subject needs and static teaching resources, and an important way to resolve the contradiction between diversified student levels and limited teaching resources. For science and engineering subjects, attention should be paid to improving the external environment of online learning, actively improving online learning performance evaluation, promoting industry-university-research cooperation, promoting demand docking, resource sharing, and complementary advantages, promoting industry-education integration and industry-university co-construction, and achieving win-win results for teachers and students. For humanities subjects, the technical support for each link of online learning should be improved, and more humanistic care should be reflected in interactive teaching support. Through more social integration, knowledge exploration-based social consultation can be promoted.

In terms of the broader external educational environment and technological development trends, we should emphasize the opportunities for educational technology innovation and industry-education integration brought about by the differential development of online teaching in various disciplines. Clearly, the issue of disciplinary differences presents challenges in terms of teaching organization and operation, but it also promotes opportunities for personalized learning, collaborative teaching, and diversified assessment. China is already a major player in online education, but it is not yet a powerhouse in this field. To unleash the educational value of online learning and expand its innovative significance, online education, represented by flipped classrooms and MOOCs, not only provides new teaching methods and educational pathways, but also brings innovative educational ideas and paradigms. Therefore, online education needs to emphasize the re-examination of external contexts, overcome the mechanical thinking of “100% replication of classroom education,” and explore new teaching paths and operating modes, providing teachers and students with more novel teaching experiences and promoting the comprehensive improvement of their knowledge, abilities, and qualities.

Limitations and future research

This study has two limitations. Firstly, to increase the credibility of the research conclusions, we have tried to increase the sample size, resulting in a relatively large number of universities involved in the study. These universities may have differences in their discipline settings and standards, which may introduce some errors that need to be addressed in future research. Secondly, previous studies have shown that factors such as the location of the participants, the level of their universities, and their academic year may affect their satisfaction with teaching. We were unable to eliminate these possible interferences in this study and will improve this in future research.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. According to the regulation of the Ethics Committee of Ningbo University, the data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons as they contain personally identifiable information.

Agyeiwaah E, Baiden FB, Gamor E, Hsu FC (2022) Determining the attributes that influence students’ online learning satisfaction during covid-19 pandemic. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ 30:100364

PubMed Google Scholar

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol 18(7):534–631

Google Scholar

Al-Azawei A, Lundqvist K (2015) Learner differences in perceived satisfaction of an online learning: an extension to the technology acceptance model in an Arabic sample. Electron J E-Learn 13(5):408–426

Alharbi S, Drew S (2014) Using the technology acceptance model in understanding academics’ behavioural intention to use learning management systems. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 5(1):143–155

Bazelais P, Doleck T, Lemay DJ (2018) Investigating the predictive power of tam: a case study of CEGEP students’ intentions to use online learning technologies. Educ Inf Technol 23(1):93–111

Article Google Scholar

Bhattacherjee A (2001) Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q 25(3):351–370

Bolliger DU, Wasilik O (2009) Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and learning in higher education. Distance Educ 30(2):103–116

Bretschneider U, Rajagopalan B, Leimeister JM (2012) Idea generation in virtual communities for innovation: The influence of participants’ motivation on idea quality. In: 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE, Hawaii, USA, pp. 3467–3479

Cakır R, Solak E (2015) Attitude of turkish efl learners towards e-learning through tam model. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 176:596–601

Chen HR, Tseng TF (2012) Factors that influence acceptance of web-based e-learning systems for the in-service education of junior high school teachers in Taiwan. Eval Program. Plan 35(3):398–406

Chikwa G, Kiran GR, Bino D (2015).Flipped Learning: Does it work? Experiences from Middle East College’s Multi-disciplinary pilot project[C]//International Conference on Education & New Learning Technologies

Daumiller M, Rinas R, Hein J, Janke S, Dickhuser O, Dresel M (2021) Shifting from face-to-face to online teaching during COVID-19: the role of university faculty achievement goals for attitudes towards this sudden change, and their relevance for burnout/engagement and student evaluations of teaching quality. Comput Hum Behav 118:106677

Davis FD (1986) A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13(3):319–340

Davis FD (1993) User acceptance of information technology: system characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int J Man Mach Stud 38(3):475–487

Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR (1992) Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computer in the workplace. J Appl Soc Psychol 22(14):1109–1130

D’errico F, Paciello M, De Carolis B, Vattanid A, Palestra G, Anzivino G (2018) Cognitive Emotions in E-Learning Processes and Their Potential Relationship with Students’ Academic Adjustment. Int J Emot Educ 10(1):89–111

Dziuban C, Moskal P, Kramer L, Thompson J (2013) Student satisfaction with online learning in the presence of ambivalence: looking for the will-o’-the-wisp. Internet High Educ 17:1–8

Farahat T (2012) Applying the technology acceptance model to online learning in the Egyptian universities. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 64(09):95–104

Hogan RL, McKnight MA (2007) Exploring burnout among university online instructors: an initial investigation. Internet High Educ 10(2):117–124

How ML, Hung WLD (2019) Educational Stakeholders’ Independent Evaluation of an Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Adaptive Learning System Using Bayesian Network Predictive Simulations. Education Sciences 9(2):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020110

Huang CH (2020) The Influence of Self-Efficacy, Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and Cognitive Load on Students’ Learning Motivation, Learning Attitude, and Learning Satisfaction in Blended Learning Methods. In: 2020 3rd international conference on Education Technology Management, London, United Kingdom, pp.29-35

Ieta A, Pantaleev A, Ilie CC (2011) An Evaluation of the “Just in Time Teaching” Method Across Disciplines. In: 2011 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. British Columbia, Canada, pp. 22-170

Igbaria M (1990) End-user computing effectiveness: a structural equation model. OMEGA 18(6):637–652

Igbaria M, Zinatelli N, Cragg P, Cavaye A (1997) Personal computing acceptance factors in small firms: a structural equation model. MIS Q 21(3):279–305

Janati SE, Maach A, Ghanami DE (2018). SMART Education Framework for Adaptation Content Presentation. Procedia Computer Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.01.141

Johnson RD, Adams S (2011) An empirical study of the use of affordances by students in the creation of personal learning environments. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 27(4):623–640

Joo YJ, Lim KY, Kim EK (2011) Online university students’ satisfaction and persistence: examining perceived level of presence, usefulness and ease of use as predictors in a structural model. Comput Educ 57(2):1654–1664

Jovanovic D, Jovanovic S (2015) An adaptive e‐learning system for java programming course, based on dokeos le. Comput Appl Eng Educ 23(3):337–343

Kizilcec RenéF, Bailenson JN, Gomez CJ (2015) The instructor’s face in video instruction: evidence from two large-scale field studies. Journal of Educational Psychology 107(3):724–739

Kranzow J (2013) Faculty leadership in online education: Structuring courses to impact student satisfaction and persistence. J Online Learn Teach 9(1):31–139

Kuo YC, Walker AE, Schroder KE, Belland BR (2014) Interaction, internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet High Educ 20:35–50

Kurucay M, Inan FA (2017) Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Comput Educ 115:20–37

Lee JW (2010) Online support service quality, online learning acceptance, and student satisfaction. Internet High Educ 13(4):277–283

Liu IF, Chen MC, Sun YS, Wible D, Kuo CH (2010) Extending the tam model to explore the factors that affect intention to use an online learning community. Comput Educ 54(2):600–610

Luo S, Huang X (2012) A survey research on the online learning adaptation of the college students//International Conference on Consumer Electronics.IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/CECNet.6202236

Lv C, Zhi X, Xu J, Yang P, Wang X (2022) Negative Impacts of School Class Segregation on Migrant Children’s Education Expectations and the Associated Mitigating Mechanism. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22):14882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214882

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Manwaring KC, Larsen R, Graham CR, Henrie CR, Halverson LR (2017) Investigating student engagement in blended learning settings using experience sampling and structural equation modeling. J Comput Assist Learn 35(10):21–33

Martins C, Oliveira T, Popovič A (2014) Understanding the internet banking adoption: a unified theory of acceptance and use of technology and perceived risk application. Int J Inf Manage 34(1):1–13

Machado FN, Meirelles FD (2015) The influence of synchronous interactive tehchnology and the methotological adaptation on the e-learning continuance intention. Revista Latinoamericana de Technologia Educativa 14(3):49–62

Menon RK, Seow LL (2021) Development of an online asynchronous clinical learning resource (“Ask the Expert”) in dental education to promote personalized learning. Healthcare 9(11):1420

Natasia SR, Wiranti Y, Parastika A (2022) Acceptance analysis of NUADU as e-learning platform using the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) approach. Procedia Computer Science 197:512–520

National Bureau of Statistics (2020) http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2020/52717/mtbd/202012/t20201203_503281.html . Accessed 3 Feb 2023

Nihad EE Mokhtar EN, Seghroucheni YZ (2017) Analysing the outcome of a learning process conducted within the system ALS_CORR.International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 12(03). https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v12i03.6377

Palmer SR, Holt DM (2010) Examining student satisfaction with wholly online learning. J Comput Assist Learn 25((2)):101–113

Park OC, Lee J (2003) Adaptive Instructional Systems. Educ Inf Technol 25:651–684

Picciano AG (2017) Theories and frameworks for online education: Seeking an integrated model. Online Learning 21(3):166–190

Piccoli G, Ahmad R, Ives B (2001) Web-based virtual learning environments: a research framework and a preliminary assessment of effectiveness in basic IT skills training. MIS Q 25(4):401–426

Ramadhan I, Pantjawati AB, Juanda EA (2021) Analysis of Learning Model and Learning Understanding of High School Students in Craft Subject Using an Online Learning System. In: 2020 6th UPI International Conference on TVET 2020 (TVET 2020). Atlantis Press, pp. 236-239

Reed TE (2001) Relationship between learning style, internet success, and internet satisfaction of students taking online courses at a selected community college. Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University

Retalis S, Papasalouros A (2005) Designing and generating educational adaptive hypermedia applications. Educ Technol Soc 8(3):26–35

Rogers PJ (2005) Logic models. In: Sandra Mathison (ed) Encyclopedia of Evaluation. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA, p. 232

Selwyn, N (2011) Education and technology: key issues and debates. London and New York: Continuum:141

Troshani I, Rampersad G, Wickramasinghe N (2011) Cloud Nine? An Integrative Risk Management Framework for Cloud Computing. In: 2011 24th BLED Proceedings. Bled, Slovenia, pp. 15-26

Tuimur R, Role E, Makewa LN (2012) Evaluation of student teachers grouped according to teaching subjects: students’ perception. Int J Emot Educ 4(4):232–246

Venkatesh V, Davis FD (2000) A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manage Sci 46(2):186–204

Waheed M (2010) Instructor’s intention to accept online education: an extended TAM model. In: E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), Florida, UAS, pp. 1263-1271

Xu J, Lv C (2022) The influence of migrant children’s identification with the college matriculation policy on their educational expectations. Front Psychol 13:963216

Yao Y, Wang P, Jiang Y, Li Q, Li Y (2022) Innovative online learning strategies for the successful construction of student self-awareness during the COVID-19 pandemic: Merging TAM with TPB. J Innov Knowl 7(4):100252

Yeung P, Jordan E (2007) The continued usage of business e-learning courses in hong kong corporations. Educ Inf Technol 12(3):175–188

Young JR (2013) What professors can learn from ‘hard core’ mooc students. Chron High Educ 59(37):A4

Zulfiani Z, Suwarna IP, Miranto S (2018) Science education adaptive learning system as a computer-based science learning with learning style variations. Journal of Baltic Science Education 17(4):711–727. https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/18.17.711

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation (Education) Project, “Research on the Path and Mechanism of Universities Promoting Rural Entrepreneurship Education under the Background of Rural Revitalization” (grant No. BIA200204).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ningbo University, Ningbo, China

Zheng Li & Siyu Li

Zhejiang Business Technology Institute, Hangzhou, China

Xiaodong Lou

Xiamen University, Xiamen, China

Minwei Chen

Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

Cixian Lv, Shuting Song & Linlin Li

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZL: Conceptualization, supervision, resources, writing review and editing; XL and MC: Data curation, writing original draft preparation; SL: Data curation; CL: Resources, writing review and editing, supervision; SS: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing original draft preparation; LL: Methodology, writing review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Cixian Lv or Shuting Song .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo University.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary file, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Li, Z., Lou, X., Chen, M. et al. Students’ online learning adaptability and their continuous usage intention across different disciplines. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 838 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02376-5

Download citation

Received : 11 April 2023

Accepted : 07 November 2023

Published : 18 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02376-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018

Associated data.

Systematic reviews were conducted in the nineties and early 2000's on online learning research. However, there is no review examining the broader aspect of research themes in online learning in the last decade. This systematic review addresses this gap by examining 619 research articles on online learning published in twelve journals in the last decade. These studies were examined for publication trends and patterns, research themes, research methods, and research settings and compared with the research themes from the previous decades. While there has been a slight decrease in the number of studies on online learning in 2015 and 2016, it has then continued to increase in 2017 and 2018. The majority of the studies were quantitative in nature and were examined in higher education. Online learning research was categorized into twelve themes and a framework across learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was developed. Online learner characteristics and online engagement were examined in a high number of studies and were consistent with three of the prior systematic reviews. However, there is still a need for more research on organization level topics such as leadership, policy, and management and access, culture, equity, inclusion, and ethics and also on online instructor characteristics.

- • Twelve online learning research themes were identified in 2009–2018.

- • A framework with learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was used.

- • Online learner characteristics and engagement were the mostly examined themes.

- • The majority of the studies used quantitative research methods and in higher education.

- • There is a need for more research on organization level topics.

1. Introduction

Online learning has been on the increase in the last two decades. In the United States, though higher education enrollment has declined, online learning enrollment in public institutions has continued to increase ( Allen & Seaman, 2017 ), and so has the research on online learning. There have been review studies conducted on specific areas on online learning such as innovations in online learning strategies ( Davis et al., 2018 ), empirical MOOC literature ( Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013 ; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016 ; Zhu et al., 2018 ), quality in online education ( Esfijani, 2018 ), accessibility in online higher education ( Lee, 2017 ), synchronous online learning ( Martin et al., 2017 ), K-12 preparation for online teaching ( Moore-Adams et al., 2016 ), polychronicity in online learning ( Capdeferro et al., 2014 ), meaningful learning research in elearning and online learning environments ( Tsai, Shen, & Chiang, 2013 ), problem-based learning in elearning and online learning environments ( Tsai & Chiang, 2013 ), asynchronous online discussions ( Thomas, 2013 ), self-regulated learning in online learning environments ( Tsai, Shen, & Fan, 2013 ), game-based learning in online learning environments ( Tsai & Fan, 2013 ), and online course dropout ( Lee & Choi, 2011 ). While there have been review studies conducted on specific online learning topics, very few studies have been conducted on the broader aspect of online learning examining research themes.

2. Systematic Reviews of Distance Education and Online Learning Research

Distance education has evolved from offline to online settings with the access to internet and COVID-19 has made online learning the common delivery method across the world. Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) reviewed research late 1990's to early 2000's, Berge and Mrozowski (2001) reviewed research 1990 to 1999, and Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) reviewed research in 2000–2008 on distance education and online learning. Table 1 shows the research themes from previous systematic reviews on online learning research. There are some themes that re-occur in the various reviews, and there are also new themes that emerge. Though there have been reviews conducted in the nineties and early 2000's, there is no review examining the broader aspect of research themes in online learning in the last decade. Hence, the need for this systematic review which informs the research themes in online learning from 2009 to 2018. In the following sections, we review these systematic review studies in detail.

Comparison of online learning research themes from previous studies.

2.1. Distance education research themes, 1990 to 1999 ( Berge & Mrozowski, 2001 )

Berge and Mrozowski (2001) reviewed 890 research articles and dissertation abstracts on distance education from 1990 to 1999. The four distance education journals chosen by the authors to represent distance education included, American Journal of Distance Education, Distance Education, Open Learning, and the Journal of Distance Education. This review overlapped in the dates of the Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) study. Berge and Mrozowski (2001) categorized the articles according to Sherry's (1996) ten themes of research issues in distance education: redefining roles of instructor and students, technologies used, issues of design, strategies to stimulate learning, learner characteristics and support, issues related to operating and policies and administration, access and equity, and costs and benefits.

In the Berge and Mrozowski (2001) study, more than 100 studies focused on each of the three themes: (1) design issues, (2) learner characteristics, and (3) strategies to increase interactivity and active learning. By design issues, the authors focused on instructional systems design and focused on topics such as content requirement, technical constraints, interactivity, and feedback. The next theme, strategies to increase interactivity and active learning, were closely related to design issues and focused on students’ modes of learning. Learner characteristics focused on accommodating various learning styles through customized instructional theory. Less than 50 studies focused on the three least examined themes: (1) cost-benefit tradeoffs, (2) equity and accessibility, and (3) learner support. Cost-benefit trade-offs focused on the implementation costs of distance education based on school characteristics. Equity and accessibility focused on the equity of access to distance education systems. Learner support included topics such as teacher to teacher support as well as teacher to student support.

2.2. Online learning research themes, 1993 to 2004 ( Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 )

Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) reviewed research on online instruction from 1993 to 2004. They reviewed 76 articles focused on online learning by searching five databases, ERIC, PsycINFO, ContentFirst, Education Abstracts, and WilsonSelect. Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) categorized research into four themes, (1) course environment, (2) learners' outcomes, (3) learners’ characteristics, and (4) institutional and administrative factors. The first theme that the authors describe as course environment ( n = 41, 53.9%) is an overarching theme that includes classroom culture, structural assistance, success factors, online interaction, and evaluation.

Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) for their second theme found that studies focused on questions involving the process of teaching and learning and methods to explore cognitive and affective learner outcomes ( n = 29, 38.2%). The authors stated that they found the research designs flawed and lacked rigor. However, the literature comparing traditional and online classrooms found both delivery systems to be adequate. Another research theme focused on learners’ characteristics ( n = 12, 15.8%) and the synergy of learners, design of the online course, and system of delivery. Research findings revealed that online learners were mainly non-traditional, Caucasian, had different learning styles, and were highly motivated to learn. The final theme that they reported was institutional and administrative factors (n = 13, 17.1%) on online learning. Their findings revealed that there was a lack of scholarly research in this area and most institutions did not have formal policies in place for course development as well as faculty and student support in training and evaluation. Their research confirmed that when universities offered online courses, it improved student enrollment numbers.

2.3. Distance education research themes 2000 to 2008 ( Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009 )

Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) reviewed 695 articles on distance education from 2000 to 2008 using the Delphi method for consensus in identifying areas and classified the literature from five prominent journals. The five journals selected due to their wide scope in research in distance education included Open Learning, Distance Education, American Journal of Distance Education, the Journal of Distance Education, and the International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. The reviewers examined the main focus of research and identified gaps in distance education research in this review.

Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) classified the studies into macro, meso and micro levels focusing on 15 areas of research. The five areas of the macro-level addressed: (1) access, equity and ethics to deliver distance education for developing nations and the role of various technologies to narrow the digital divide, (2) teaching and learning drivers, markets, and professional development in the global context, (3) distance delivery systems and institutional partnerships and programs and impact of hybrid modes of delivery, (4) theoretical frameworks and models for instruction, knowledge building, and learner interactions in distance education practice, and (5) the types of preferred research methodologies. The meso-level focused on seven areas that involve: (1) management and organization for sustaining distance education programs, (2) examining financial aspects of developing and implementing online programs, (3) the challenges and benefits of new technologies for teaching and learning, (4) incentives to innovate, (5) professional development and support for faculty, (6) learner support services, and (7) issues involving quality standards and the impact on student enrollment and retention. The micro-level focused on three areas: (1) instructional design and pedagogical approaches, (2) culturally appropriate materials, interaction, communication, and collaboration among a community of learners, and (3) focus on characteristics of adult learners, socio-economic backgrounds, learning preferences, and dispositions.

The top three research themes in this review by Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) were interaction and communities of learning ( n = 122, 17.6%), instructional design ( n = 121, 17.4%) and learner characteristics ( n = 113, 16.3%). The lowest number of studies (less than 3%) were found in studies examining the following research themes, management and organization ( n = 18), research methods in DE and knowledge transfer ( n = 13), globalization of education and cross-cultural aspects ( n = 13), innovation and change ( n = 13), and costs and benefits ( n = 12).

2.4. Online learning research themes

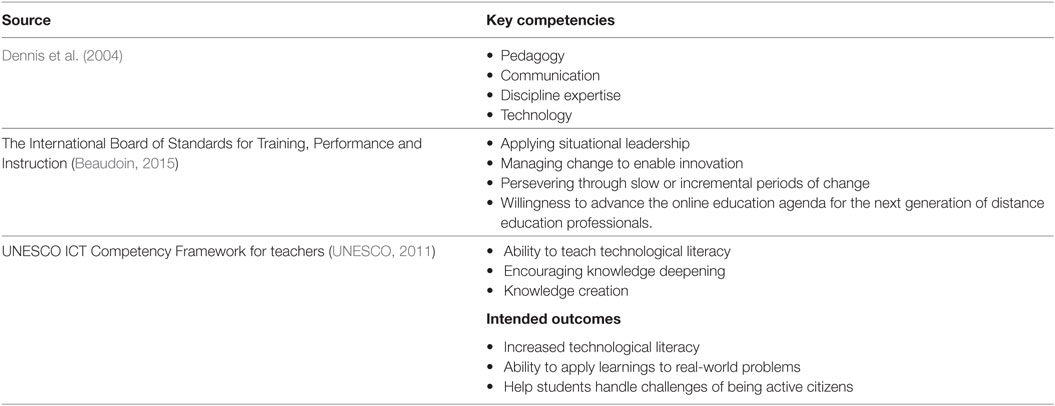

These three systematic reviews provide a broad understanding of distance education and online learning research themes from 1990 to 2008. However, there is an increase in the number of research studies on online learning in this decade and there is a need to identify recent research themes examined. Based on the previous systematic reviews ( Berge & Mrozowski, 2001 ; Hung, 2012 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009 ), online learning research in this study is grouped into twelve different research themes which include Learner characteristics, Instructor characteristics, Course or program design and development, Course Facilitation, Engagement, Course Assessment, Course Technologies, Access, Culture, Equity, Inclusion, and Ethics, Leadership, Policy and Management, Instructor and Learner Support, and Learner Outcomes. Table 2 below describes each of the research themes and using these themes, a framework is derived in Fig. 1 .

Research themes in online learning.

Online learning research themes framework.

The collection of research themes is presented as a framework in Fig. 1 . The themes are organized by domain or level to underscore the nested relationship that exists. As evidenced by the assortment of themes, research can focus on any domain of delivery or associated context. The “Learner” domain captures characteristics and outcomes related to learners and their interaction within the courses. The “Course and Instructor” domain captures elements about the broader design of the course and facilitation by the instructor, and the “Organizational” domain acknowledges the contextual influences on the course. It is important to note as well that due to the nesting, research themes can cross domains. For example, the broader cultural context may be studied as it pertains to course design and development, and institutional support can include both learner support and instructor support. Likewise, engagement research can involve instructors as well as learners.

In this introduction section, we have reviewed three systematic reviews on online learning research ( Berge & Mrozowski, 2001 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009 ). Based on these reviews and other research, we have derived twelve themes to develop an online learning research framework which is nested in three levels: learner, course and instructor, and organization.

2.5. Purpose of this research

In two out of the three previous reviews, design, learner characteristics and interaction were examined in the highest number of studies. On the other hand, cost-benefit tradeoffs, equity and accessibility, institutional and administrative factors, and globalization and cross-cultural aspects were examined in the least number of studies. One explanation for this may be that it is a function of nesting, noting that studies falling in the Organizational and Course levels may encompass several courses or many more participants within courses. However, while some research themes re-occur, there are also variations in some themes across time, suggesting the importance of research themes rise and fall over time. Thus, a critical examination of the trends in themes is helpful for understanding where research is needed most. Also, since there is no recent study examining online learning research themes in the last decade, this study strives to address that gap by focusing on recent research themes found in the literature, and also reviewing research methods and settings. Notably, one goal is to also compare findings from this decade to the previous review studies. Overall, the purpose of this study is to examine publication trends in online learning research taking place during the last ten years and compare it with the previous themes identified in other review studies. Due to the continued growth of online learning research into new contexts and among new researchers, we also examine the research methods and settings found in the studies of this review.

The following research questions are addressed in this study.

- 1. What percentage of the population of articles published in the journals reviewed from 2009 to 2018 were related to online learning and empirical?

- 2. What is the frequency of online learning research themes in the empirical online learning articles of journals reviewed from 2009 to 2018?