A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- CDC Field Epidemiology Manual Chapters

Collecting and Analyzing Qualitative Data

At a glance.

Chapter 10 of The CDC Field Epidemiology Manual

Introduction

Qualitative research methods are a key component of field epidemiologic investigations because they can provide insight into the perceptions, values, opinions, and community norms where investigations are being conducted 1 2 . Open-ended inquiry methods, the mainstay of qualitative interview techniques, are essential in formative research for exploring contextual factors and rationales for risk behaviors that do not fit neatly into predefined categories. For example, during the 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease outbreaks in parts of West Africa, understanding the cultural implications of burial practices within different communities was crucial to designing and monitoring interventions for safe burials (see below). In program evaluations, qualitative methods can assist the investigator in diagnosing what went right or wrong as part of a process evaluation or in troubleshooting why a program might not be working as well as expected. When designing an intervention, qualitative methods can be useful in exploring dimensions of acceptability to increase the chances of intervention acceptance and success. When performed in conjunction with quantitative studies, qualitative methods can help the investigator confirm, challenge, or deepen the validity of conclusions than either component might have yielded alone 1 2 .

Qualitative Research During the Ebola Virus Disease Outbreaks in Parts of West Africa (2014)

Qualitative research was used extensively in response to the Ebola virus disease outbreaks in parts of West Africa to understand burial practices and to design culturally appropriate strategies to ensure safe burials. Qualitative studies were also used to monitor key aspects of the response.

In October 2014, Liberia experienced an abrupt and steady decrease in case counts and deaths in contrast with predicted disease models of an increased case count. At the time, communities were resistant to entering Ebola treatment centers, raising the possibility that patients were not being referred for care and communities might be conducting occult burials.

To assess what was happening at the community level, the Liberian Emergency Operations Center recruited epidemiologists from the US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the African Union to investigate the problem.

Teams conducted in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with community leaders, local funeral directors, and coffin makers and learned that communities were not conducting occult burials and that the overall number of burials was less than what they had experienced in previous years. Other key findings included the willingness of funeral directors to cooperate with disease response efforts, the need for training of funeral home workers, and considerable community resistance to cremation practices. These findings prompted the Emergency Operations Center to open a burial ground for Ebola decedents, support enhanced testing of burials in the private sector, and train private-sector funeral workers regarding safe burial practices.

Source: Melissa Corkum, personal communication

Choosing When to Apply Qualitative Methods

Similar to quantitative approaches, qualitative research seeks answers to specific questions by using rigorous approaches to collecting and compiling information and producing findings that can be applicable beyond the study population. The fundamental difference in approaches lies in how they translate real-life complexities of initial observations into units of analysis. Data collected in qualitative studies typically are in the form of text or visual images, which provide rich sources of insight but also tend to be bulky and time-consuming to code and analyze. Practically speaking, qualitative study designs tend to favor small, purposively selected samples 1 ideal for case studies or in-depth analysis. The combination of purposive sampling and open-ended question formats deprive qualitative study designs of the power to quantify and generalize conclusions, one of the key limitations of this approach.

Qualitative scientists might argue, however, that the generalizability and precision possible through probabilistic sampling and categorical outcomes are achieved at the cost of enhanced validity, nuance, and naturalism that less structured approaches offer 3 . Open-ended techniques are particularly useful for understanding subjective meanings and motivations underlying behavior. They enable investigators to be equally adept at exploring factors observed and unobserved, intentions as well as actions, internal meanings as well as external consequences, options considered but not taken, and unmeasurable as well as measurable outcomes. These methods are important when the source of or solution to a public health problem is rooted in local perceptions rather than objectively measurable characteristics selected by outside observers 3 . Ultimately, such approaches have the ability to go beyond quantifying questions of how much or how many to take on questions of how or why from the perspective and in the words of the study subjects themselves 1 2 .

Another key advantage of qualitative methods for field investigations is their flexibility 4 . Qualitative designs not only enable but also encourage flexibility in the content and flow of questions to challenge and probe for deeper meanings or follow new leads if they lead to deeper understanding of an issue 5 . It is not uncommon for topic guides to be adjusted in the course of fieldwork to investigate emerging themes relevant to answering the original study question. As discussed herein, qualitative study designs allow flexibility in sample size to accommodate the need for more or fewer interviews among particular groups to determine the root cause of an issue (see the section on Sampling and Recruitment in Qualitative Research). In the context of field investigations, such methods can be extremely useful for investigating complex or fast-moving situations where the dimensions of analysis cannot be fully anticipated.

Ultimately, the decision whether to include qualitative research in a particular field investigation depends mainly on the nature of the research question itself. Certain types of research topics lend themselves more naturally to qualitative rather than other approaches ( Table 10.1 ). These include exploratory investigations when not enough is known about a problem to formulate a hypothesis or develop a fixed set of questions and answer codes. They include research questions where intentions matter as much as actions and "why?" or "why not?" questions matter as much as precise estimation of measured outcomes. Qualitative approaches also work well when contextual influences, subjective meanings, stigma, or strong social desirability biases lower faith in the validity of responses coming from a relatively impersonal survey questionnaire interview.

The availability of personnel with training and experience in qualitative interviewing or observation is critical for obtaining the best quality data but is not absolutely required for rapid assessment in field settings. Qualitative interviewing requires a broader set of skills than survey interviewing. It is not enough to follow a topic guide like a questionnaire, in order, from top to bottom. A qualitative interviewer must exercise judgment to decide when to probe and when to move on, when to encourage, challenge, or follow relevant leads even if they are not written in the topic guide. Ability to engage with informants, connect ideas during the interview, and think on one's feet are common characteristics of good qualitative interviewers. By far the most important qualification in conducting qualitative fieldwork is a firm grasp of the research objectives; with this qualification, a member of the research team armed with curiosity and a topic guide can learn on the job with successful results.

Examples of research topics for which qualitative methods should be considered for field investigations

Research topic

Exploratory research

The relevant questions or answer options are unknown in advance

In-depth case studies Situation analyses by viewing a problem from multiple perspectives Hypothesis generation

Understanding the role of context

Risk exposure or care-seeking behavior is embedded in particular social or physical environments

Key barriers or enablers to effective response Competing concerns that might interfere with each other Environmental behavioral interactions

Understanding the role of perceptions and subjective meaning

Different perception or meaning of the same observable facts influence risk exposure or behavioral response

Why or why not questions Understanding how persons make health decisions Exploring options considered but not taken

Understanding context and meaning of hidden, sensitive, or illegal behaviors

Legal barriers or social desirability biases prevent candid reporting by using conventional interviewing methods

Risky sexual or drug use behaviors Quality-of-care questions Questions that require a higher degree of trust between respondent and interviewer to obtain valid answers

Evaluating how interventions work in practice

Evaluating What went right or, more commonly, what went wrong with a public health response Process or outcome evaluations Who benefited in what way from what perceived change in practice

‘How’ questions Why interventions fail Unintended consequences of programs Patient–provider interactions

Commonly Used Qualitative Methods in Field Investigations

Semi-structured interviews.

Semi-structured interviews can be conducted with single participants (in-depth or individual key informants) or with groups (focus group discussions [FGDs] or key informant groups). These interviews follow a suggested topic guide rather than a fixed questionnaire format. Topic guides typically consist of a limited number (10-15) of broad, open-ended questions followed by bulleted points to facilitate optional probing. The conversational back-and-forth nature of a semi-structured format puts the researcher and researched (the interview participants) on more equal footing than allowed by more structured formats. Respondents, the term used in the case of quantitative questionnaire interviews, become informants in the case of individual semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDIs) or participants in the case of FGDs. Freedom to probe beyond initial responses enables interviewers to actively engage with the interviewee to seek clarity, openness, and depth by challenging informants to reach below layers of self-presentation and social desirability. In this respect, interviewing is sometimes compared with peeling an onion, with the first version of events accessible to the public, including survey interviewers, and deeper inner layers accessible to those who invest the time and effort to build rapport and gain trust. (The theory of the active interview suggests that all interviews involve staged social encounters where the interviewee is constantly assessing interviewer intentions and adjusting his or her responses accordingly 1 . Consequently good rapport is important for any type of interview. Survey formats give interviewers less freedom to divert from the preset script of questions and formal probes.)

Individual In-Depth Interviews and Key-Informant Interviews

The most common forms of individual semi-structured interviews are IDIs and key informant interviews (KIIs). IDIs are conducted among informants typically selected for first-hand experience (e.g., service users, participants, survivors) relevant to the research topic. These are typically conducted as one-on-one face-to-face interviews (two-on-one if translators are needed) to maximize rapport-building and confidentiality. KIIs are similar to IDIs but focus on individual persons with special knowledge or influence (e.g., community leaders or health authorities) that give them broader perspective or deeper insight into the topic area (See: Identifying Barriers and Solutions to Improved Healthcare Worker Practices in Egypt ). Whereas IDIs tend to focus on personal experiences, context, meaning, and implications for informants, KIIs tend to steer away from personal questions in favor of expert insights or community perspectives. IDIs enable flexible sampling strategies and represent the interviewing reference standard for confidentiality, rapport, richness, and contextual detail. However, IDIs are time-and labor-intensive to collect and analyze. Because confidentiality is not a concern in KIIs, these interviews might be conducted as individual or group interviews, as required for the topic area.

Focus Group Discussions and Group Key Informant Interviews

FGDs are semi-structured group interviews in which six to eight participants, homogeneous with respect to a shared experience, behavior, or demographic characteristic, are guided through a topic guide by a trained moderator 6 . (Advice on ideal group interview size varies. The principle is to convene a group large enough to foster an open, lively discussion of the topic, and small enough to ensure all participants stay fully engaged in the process.) Over the course of discussion, the moderator is expected to pose questions, foster group participation, and probe for clarity and depth. Long a staple of market research, focus groups have become a widely used social science technique with broad applications in public health, and they are especially popular as a rapid method for assessing community norms and shared perceptions.

Focus groups have certain useful advantages during field investigations. They are highly adaptable, inexpensive to arrange and conduct, and often enjoyable for participants. Group dynamics effectively tap into collective knowledge and experience to serve as a proxy informant for the community as a whole. They are also capable of recreating a microcosm of social norms where social, moral, and emotional dimensions of topics are allowed to emerge. Skilled moderators can also exploit the tendency of small groups to seek consensus to bring out disagreements that the participants will work to resolve in a way that can lead to deeper understanding. There are also limitations on focus group methods. Lack of confidentiality during group interviews means they should not be used to explore personal experiences of a sensitive nature on ethical grounds. Participants may take it on themselves to volunteer such information, but moderators are generally encouraged to steer the conversation back to general observations to avoid putting pressure on other participants to disclose in a similar way. Similarly, FGDs are subject by design to strong social desirability biases. Qualitative study designs using focus groups sometimes add individual interviews precisely to enable participants to describe personal experiences or personal views that would be difficult or inappropriate to share in a group setting. Focus groups run the risk of producing broad but shallow analyses of issues if groups reach comfortable but superficial consensus around complex topics. This weakness can be countered by training moderators to probe effectively and challenge any consensus that sounds too simplistic or contradictory with prior knowledge. However, FGDs are surprisingly robust against the influence of strongly opinionated participants, highly adaptable, and well suited to application in study designs where systematic comparisons across different groups are called for.

Like FGDs, group KIIs rely on positive chemistry and the stimulating effects of group discussion but aim to gather expert knowledge or oversight on a particular topic rather than lived experience of embedded social actors. Group KIIs have no minimum size requirements and can involve as few as two or three participants.

Identifying Barriers and Solutions to Improved Healthcare Worker Practices in Egypt

Egypt's National Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) program undertook qualitative research to gain an understanding of the contextual behaviors and motivations of healthcare workers in complying with IPC guidelines. The study was undertaken to guide the development of effective behavior change interventions in healthcare settings to improve IPC compliance.

Key informant interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in two governorates among cleaning staff, nursing staff, and physicians in different types of healthcare facilities. The findings highlighted social and cultural barriers to IPC compliance, enabling the IPC program to design responses. For example,

- Informants expressed difficulty in complying with IPC measures that forced them to act outside their normal roles in an ingrained hospital culture. Response: Role models and champions were introduced to help catalyze change.

- Informants described fatalistic attitudes that undermined energy and interest in modifying behavior. Response: Accordingly, interventions affirming institutional commitment to change while challenging fatalistic assumptions were developed.

- Informants did not perceive IPC as effective. Response: Trainings were amended to include scientific evidence justifying IPC practices.

- Informants perceived hygiene as something they took pride in and were judged on. Response: Public recognition of optimal IPC practice was introduced to tap into positive social desirability and professional pride in maintaining hygiene in the work environment.

Qualitative research identified sources of resistance to quality clinical practice in Egypt's healthcare settings and culturally appropriate responses to overcome that resistance.

Source: Anna Leena Lohiniva, personal communication.

Visualization Methods

Visualization methods have been developed as a way to enhance participation and empower interviewees relative to researchers during group data collection 7 . Visualization methods involve asking participants to engage in collective problem- solving of challenges expressed through group production of maps, diagrams, or other images. For example, participants from the community might be asked to sketch a map of their community and to highlight features of relevance to the research topic (e.g., access to health facilities or sites of risk concentrations). Body diagramming is another visualization tool in which community members are asked to depict how and where a health threat affects the human body as a way of understanding folk conceptions of health, disease, treatment, and prevention. Ensuing debate and dialogue regarding construction of images can be recorded and analyzed in conjunction with the visual image itself. Visualization exercises were initially designed to accommodate groups the size of entire communities, but they can work equally well with smaller groups corresponding to the size of FGDs or group KIIs.

Sampling and Recruitment for Qualitative Research

Selecting a sample of study participants.

Fundamental differences between qualitative and quantitative approaches to research emerge most clearly in the practice of sampling and recruitment of study participants. Qualitative samples are typically small and purposive. In-depth interview informants are usually selected on the basis of unique characteristics or personal experiences that make them exemplary for the study, if not typical in other respects. Key informants are selected for their unique knowledge or influence in the study domain. Focus group mobilization often seeks participants who are typical with respect to others in the community having similar exposure or shared characteristics. Often, however, participants in qualitative studies are selected because they are exceptional rather than simply representative. Their value lies not in their generalizability but in their ability to generate insight into the key questions driving the study.

Determining Sample Size

Sample size determination for qualitative studies also follows a different logic than that used for probability sample surveys. For example, whereas some qualitative methods specify ideal ranges of participants that constitute a valid observation (e.g., focus groups), there are no rules on how many observations it takes to attain valid results. In theory, sample size in qualitative designs should be determined by the saturation principle , where interviews are conducted until additional interviews yield no additional insights into the topic of research 8 . Practically speaking, designing a study with a range in number of interviews is advisable for providing a level of flexibility if additional interviews are needed to reach clear conclusions.

Recruiting Study Participants

Recruitment strategies for qualitative studies typically involve some degree of participant self-selection (e.g., advertising in public spaces for interested participants) and purposive selection (e.g., identification of key informants). Purposive selection in community settings often requires authorization from local authorities and assistance from local mobilizers before the informed consent process can begin. Clearly specifying eligibility criteria is crucial for minimizing the tendency of study mobilizers to apply their own filters regarding who reflects the community in the best light. In addition to formal eligibility criteria, character traits (e.g., articulate and interested in participating) and convenience (e.g., not too far away) are legitimate considerations for whom to include in the sample. Accommodations to personality and convenience help to ensure the small number of interviews in a typical qualitative design yields maximum value for minimum investment. This is one reason why random sampling of qualitative informants is not only unnecessary but also potentially counterproductive.

Managing, Condensing, Displaying, and Interpreting Qualitative Data

Analysis of qualitative data can be divided into four stages 9 : data management, data condensation, data display, and drawing and verifying conclusions.

Managing Qualitative Data

From the outset, developing a clear organization system for qualitative data is important. Ideally, naming conventions for original data files and subsequent analysis should be recorded in a data dictionary file that includes dates, locations, defining individual or group characteristics, interviewer characteristics, and other defining features. Digital recordings of interviews or visualization products should be reviewed to ensure fidelity of analyzed data to original observations. If ethics agreements require that no names or identifying characteristics be recorded, all individual names must be removed from final transcriptions before analysis begins. If data are analyzed by using textual data analysis software, maintaining careful version control over the data files is crucial, especially when multiple coders are involved.

Condensing Qualitative Data

Condensing refers to the process of selecting, focusing, simplifying, and abstracting the data available at the time of the original observation, then transforming the condensed data into a data set that can be analyzed. In qualitative research, most of the time investment required to complete a study comes after the fieldwork is complete. A single hour of taped individual interview can take a full day to transcribe and additional time to translate if necessary. Group interviews can take even longer because of the difficulty of transcribing active group input. Each stage of data condensation involves multiple decisions that require clear rules and close supervision. A typical challenge is finding the right balance between fidelity to the rhythm and texture of original language and clarity of the translated version in the language of analysis. For example, discussions among groups with little or no education should not emerge after the transcription (and translation) process sounding like university graduates. Judgment must be exercised about which terms should be translated and which terms should be kept in vernacular because there is no appropriate term in English to capture the richness of its meaning.

Displaying Qualitative Data

After the initial condensation, qualitative analysis depends on how the data are displayed. Decisions regarding how data are summarized and laid out to facilitate comparison influence the depth and detail of the investigation's conclusions. Displays might range from full verbatim transcripts of interviews to bulleted summaries or distilled summaries of interview notes. In a field setting, a useful and commonly used display format is an overview chart in which key themes or research questions are listed in rows in a word processer table or in a spreadsheet and individual informant or group entry characteristics are listed across columns. Overview charts are useful because they allow easy, systematic comparison of results.

Drawing and Verifying Conclusions

Analyzing qualitative data is an iterative and ideally interactive process that leads to rigorous and systematic interpretation of textual or visual data. At least four common steps are involved:

- Reading and rereading. The core of qualitative analysis is careful, systematic, and repeated reading of text to identify consistent themes and interconnections emerging from the data. The act of repeated reading inevitably yields new themes, connections, and deeper meanings from the first reading. Reading the full text of interviews multiple times before subdividing according to coded themes is key to appreciating the full context and flow of each interview before subdividing and extracting coded sections of text for separate analysis.

- Coding. A common technique in qualitative analysis involves developing codes for labeling sections of text for selective retrieval in later stages of analysis and verification. Different approaches can be used for textual coding. One approach, structural coding , follows the structure of the interview guide. Another approach, thematic coding , labels common themes that appear across interviews, whether by design of the topic guide or emerging themes assigned based on further analysis. To avoid the problem of shift and drift in codes across time or multiple coders, qualitative investigators should develop a standard codebook with written definitions and rules about when codes should start and stop. Coding is also an iterative process in which new codes that emerge from repeated reading are layered on top of existing codes. Development and refinement of the codebook is inseparably part of the analysis.

- Analyzing and writing memos. As codes are being developed and refined, answers to the original research question should begin to emerge. Coding can facilitate that process through selective text retrieval during which similarities within and between coding categories can be extracted and compared systematically. Because no p values can be derived in qualitative analyses to mark the transition from tentative to firm conclusions, standard practice is to write memos to record evolving insights and emerging patterns in the data and how they relate to the original research questions. Writing memos is intended to catalyze further thinking about the data, thus initiating new connections that can lead to further coding and deeper understanding.

- Verifying conclusions. Analysis rigor depends as much on the thoroughness of the cross-examination and attempt to find alternative conclusions as on the quality of original conclusions. Cross-examining conclusions can occur in different ways. One way is encouraging regular interaction between analysts to challenge conclusions and pose alternative explanations for the same data. Another way is quizzing the data (i.e., retrieving coded segments by using Boolean logic to systematically compare code contents where they overlap with other codes or informant characteristics). If alternative explanations for initial conclusions are more difficult to justify, confidence in those conclusions is strengthened.

Coding and Analysis Requirements

Above all, qualitative data analysis requires sufficient time and immersion in the data. Computer textual software programs can facilitate selective text retrieval and quizzing the data, but discerning patterns and arriving at conclusions can be done only by the analysts. This requirement involves intensive reading and rereading, developing codebooks and coding, discussing and debating, revising codebooks, and recoding as needed until clear patterns emerge from the data. Although quality and depth of analysis is usually proportional to the time invested, a number of techniques, including some mentioned earlier, can be used to expedite analysis under field conditions.

- Detailed notes instead of full transcriptions. Assigning one or two note-takers to an interview can be considered where the time needed for full transcription and translation is not feasible. Even if plans are in place for full transcriptions after fieldwork, asking note-takers to submit organized summary notes is a useful technique for getting real-time feedback on interview content and making adjustments to topic guides or interviewer training as needed.

- Summary overview charts for thematic coding. (See discussion under "Displaying Data.") If there is limited time for full transcription and/or systematic coding of text interviews using textual analysis software in the field, an overview chart is a useful technique for rapid manual coding.

- Thematic extract files. This is a slightly expanded version of manual thematic coding that is useful when full transcriptions of interviews are available. With use of a word processing program, files can be sectioned according to themes, or separate files can be created for each theme. Relevant extracts from transcripts or analyst notes can be copied and pasted into files or sections of files corresponding to each theme. This is particularly useful for storing appropriate quotes that can be used to illustrate thematic conclusions in final reports or manuscripts.

- Teamwork. Qualitative analysis can be performed by a single analyst, but it is usually beneficial to involve more than one. Qualitative conclusions involve subjective judgment calls. Having more than one coder or analyst working on a project enables more interactive discussion and debate before reaching consensus on conclusions.

- Systematic coding.

- Selective retrieval of coded segments.

- Verifying conclusions ("quizzing the data").

- Working on larger data sets with multiple separate files.

- Working in teams with multiple coders to allow intercoder reliability to be measured and monitored.

The most widely used software packages (e.g., NVivo [QSR International Pty. Ltd., Melbourne, VIC, Australia] and ATLAS.ti [Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany]) evolved to include sophisticated analytic features covering a wide array of applications but are relatively expensive in terms of license cost and initial investment in time and training. A promising development is the advent of free or low-cost Web-based services (e.g., Dedoose [Sociocultural Research Consultants LLC, Manhattan Beach, CA]) that have many of the same analytic features on a more affordable subscription basis and that enable local research counterparts to remain engaged through the analysis phase (see Teamwork criteria). The start-up costs of computer-assisted analysis need to be weighed against their analytic benefits, which tend to decline with the volume and complexity of data to be analyzed. For rapid situational analyses or small scale qualitative studies (e.g. fewer than 30 observations as an informal rule of thumb), manual coding and analysis using word processing or spreadsheet programs is faster and sufficient to enable rigorous analysis and verification of conclusions.

Qualitative methods belong to a branch of social science inquiry that emphasizes the importance of context, subjective meanings, and motivations in understanding human behavior patterns. Qualitative approaches definitionally rely on open-ended, semistructured, non-numeric strategies for asking questions and recording responses. Conclusions are drawn from systematic visual or textual analysis involving repeated reading, coding, and organizing information into structured and emerging themes. Because textual analysis is relatively time-and skill-intensive, qualitative samples tend to be small and purposively selected to yield the maximum amount of information from the minimum amount of data collection. Although qualitative approaches cannot provide representative or generalizable findings in a statistical sense, they can offer an unparalleled level of detail, nuance, and naturalistic insight into the chosen subject of study. Qualitative methods enable investigators to “hear the voice” of the researched in a way that questionnaire methods, even with the occasional open-ended response option, cannot.

Whether or when to use qualitative methods in field epidemiology studies ultimately depends on the nature of the public health question to be answered. Qualitative approaches make sense when a study question about behavior patterns or program performance leads with why, why not , or how . Similarly, they are appropriate when the answer to the study question depends on understanding the problem from the perspective of social actors in real-life settings or when the object of study cannot be adequately captured, quantified, or categorized through a battery of closed-ended survey questions (e.g., stigma or the foundation of health beliefs). Another justification for qualitative methods occurs when the topic is especially sensitive or subject to strong social desirability biases that require developing trust with the informant and persistent probing to reach the truth. Finally, qualitative methods make sense when the study question is exploratory in nature, where this approach enables the investigator the freedom and flexibility to adjust topic guides and probe beyond the original topic guides.

Given that the conditions just described probably apply more often than not in everyday field epidemiology, it might be surprising that such approaches are not incorporated more routinely into standard epidemiologic training. Part of the answer might have to do with the subjective element in qualitative sampling and analysis that seems at odds with core scientific values of objectivity. Part of it might have to do with the skill requirements for good qualitative interviewing, which are generally more difficult to find than those required for routine survey interviewing.

For the field epidemiologist unfamiliar with qualitative study design, it is important to emphasize that obtaining important insights from applying basic approaches is possible, even without a seasoned team of qualitative researchers on hand to do the work. The flexibility of qualitative methods also tends to make them forgiving with practice and persistence. Beyond the required study approvals and ethical clearances, the basic essential requirements for collecting qualitative data in field settings start with an interviewer having a strong command of the research question, basic interactive and language skills, and a healthy sense of curiosity, armed with a simple open-ended topic guide and a tape recorder or note-taker to capture the key points of the discussion. Readily available manuals on qualitative study design, methods, and analysis can provide additional guidance to improve the quality of data collection and analysis.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.

- Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative research methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. The constructivist credo . Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2013.

- Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM, Guest G, Namey E. Qualitative research methods: a data collectors field guide. https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/Qualitative%20Research%20Methods%20-%20A%20Data%20Collector%27s%20Field%20Guide.pdf

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009:230–43.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

- Margolis E, Pauwels L. The Sage handbook of visual research methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011.

- Mason M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum : Qualitative Social Research/Sozialforschung. 2010;11(3).

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

- Silver C, Lewins A. Using software in qualitative research: a step-by-step guide . Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage: 2014.

Field Epi Manual

The CDC Field Epidemiology Manual is a definitive guide to investigating acute public health events on the ground and in real time.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A review of qualitative data analysis practices in health education and health behavior research

Ilana g raskind , msc, rachel c shelton , scd, mph, dawn l comeau , phd, hannah l f cooper , scd, derek m griffith , phd, michelle c kegler , drph, mph.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Issue date 2019 Feb.

Data analysis is one of the most important, yet least understood stages of the qualitative research process. Through rigorous analysis, data can illuminate the complexity of human behavior, inform interventions, and give voice to people’s lived experiences. While significant progress has been made in advancing the rigor of qualitative analysis, the process often remains nebulous. To better understand how our field conducts and reports qualitative analysis, we reviewed qualitative papers published in Health Education & Behavior between 2000–2015. Two independent reviewers abstracted information in the following categories: data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity. Of the forty-eight (n=48) articles identified, the majority (n=31) reported using qualitative software to manage data. Double-coding transcripts was the most common coding method (n=23); however, nearly one-third of articles did not clearly describe the coding approach. Although terminology used to describe the analytic process varied widely, we identified four overarching trajectories common to most articles (n=37). Trajectories differed in their use of inductive and deductive coding approaches, formal coding templates, and rounds or levels of coding. Trajectories culminated in the iterative review of coded data to identify emergent themes. Few papers explicitly discussed trustworthiness or reflexivity. Member checks (n=9), triangulation of methods (n=8), and peer debriefing (n=7) were the most common. Variation in the type and depth of information provided poses challenges to assessing quality and enabling replication. Greater transparency and more intentional application of diverse analytic methods can advance the rigor and impact of qualitative research in our field.

Keywords: health behavior, health promotion, qualitative methods, research design, training health professionals

Introduction

Data analysis is one of the most powerful, yet least understood stages of the qualitative research process. During this phase extensive fieldwork and illustrative data are transformed into substantive and actionable conclusions. In the field of health education and health behavior, rigorous data analysis can elucidate the complexity of human behavior, facilitate the development and implementation of impactful programs and interventions, and give voice to the lived experiences of inequity. While tremendous progress has been made in advancing the rigor of qualitative analysis, persistent misconceptions that such methods can be intuited rather than intentionally applied, coupled with inconsistent and vague reporting, continue to obscure the process ( Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014 ). In an era of public health grounded in evidence-based research and practice, rigorously conducting, documenting, and reporting qualitative analysis is critical for the generation of reliable and actionable knowledge.

There is no single “right” way to engage in qualitative analysis ( Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ). The guiding inquiry framework, research questions, participants, context, and type of data collected should all inform the choice of analytic method ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 ; Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ). While the diversity and flexibility of methods for analysis may put the qualitative researcher in a more innovative position than their quantitative counterparts ( Miles et al., 2014 ), it also makes rigorous application and transparent reporting even more important ( Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2011 ). Unlike many forms of quantitative analysis, qualitative analytic methods are far less likely to have standardized, widely agreed upon definitions and procedures ( Miles et al., 2014 ). The phrase thematic analysis , for example, may capture a variety of approaches and methodological tools, limiting the reader’s ability to accurately assess the rigor and credibility of the research. An explicit description of how data were condensed, patterns identified, and interpretations substantiated is likely of much greater use in assessing quality and facilitating replication. Yet, despite increased attention to the systematization of qualitative research ( Levitt et al., 2018 ; O’Brien et al., 2014 ; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007 ), many studies remain vague in their reporting of how the researcher moved from “1,000 pages of field notes to the final conclusions” ( Miles et al., 2014 ).

Reflecting on the relevance of qualitative methods to the field of health education and health behavior, and challenges still facing the paradigm, we were interested in understanding how our field conducts and reports qualitative data analysis. In a companion paper ( Kegler et al. 2018 ), we describe our wider review of qualitative articles published in Health Education & Behavior ( HE&B ) from 2000 to 2015, broadly focused on how qualitative inquiry frameworks inform study design and study implementation. Upon conducting our initial review, we discovered that our method for abstracting information related to data analysis—documenting the labels researchers applied to analytic methods—shed little light on the concrete details of their analytic processes. As a result, we conducted a second round of review focused on how analytic approaches and techniques were applied. In particular, we assessed data preparation and management, approaches to data coding, analytic trajectories, methods for assessing credibility and trustworthiness, and approaches to reflexivity. Our objective was to develop a greater understanding of how our field engages in qualitative data analysis, and identify opportunities for strengthening our collective methodological toolbox.

Our methods are described in detail in a companion paper ( Kegler et al. 2018 ). Briefly, eligible articles were published in HE&B between 2000 and 2015 and used qualitative research methods. We excluded mixed methods studies because of differences in underlying paradigms, study design, and methods for analysis and interpretation. We reviewed 48 papers using an abstraction form designed to assess 10 main topics: qualitative inquiry framework, sampling strategy, data collection methods, data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, reporting of results, use of theory, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity. The present paper reports results on data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity.

Each article was initially double-coded by a team of six researchers, with one member of each coding pair reviewing the completed abstraction forms and noting discrepancies. This coder fixed discrepancies that could be easily resolved by re-reviewing the full text (e.g. sample size); a third coder reviewed more challenging discrepancies, which were then discussed with a member of the coding pair until consensus was reached. Data were entered into an Access database, and queries were generated to summarize results for each topic. Preliminary results were shared with all co-authors for review, and then discussed as a group.

New topics of interest emerged from the first round of review regarding how analytic approaches and techniques were applied. Two of the authors conducted a second round of review focused on: use of software, how authors discussed achieving coding consensus, use of matrices, analytic references cited, variation in how authors used the terms code and theme , and identification of common analytic trajectories, including how themes were identified, and the process of grouping themes or concepts. To facilitate the second round of review, the analysis section of each article was excerpted into a single document. One reviewer populated a spreadsheet with text from each article pertinent to the aforementioned categories, and summarized the content within each category. These results informed the development of a formal abstraction form. Two reviewers independently completed an abstraction form for each article’s analysis section and met to resolve discrepancies. For three of the categories (use of the terms code and theme; how themes were identified; and the process of grouping themes or concepts), we do not report counts or percentages because the level of detail provided was often insufficient to determine with certainty whether a particular strategy or combination of strategies was used.

Data preparation and management

We examined several dimensions of the data preparation and management process ( Table 1 ). The vast majority of papers (87.5%) used verbatim transcripts as the primary data source. Most others used detailed written summaries of interviews or a combination of transcripts and written summaries (14.6%). We documented whether qualitative software was mentioned and which packages were most commonly used. Fourteen of the articles used Atlas.ti (29.2%) and another seventeen (35.4%) did not report using software. NVivo and its predecessor NUD-IST were somewhat common (20.8%), and Ethnograph was used in two articles. Several other software packages were mentioned in one of the papers (e.g. AnSWR, EthnoNotes). Of those reporting use of a software package, the most common use, in addition to the implied management of data, was to code transcripts (33.3%). Approximately 10.4% described using the software to generate code reports, and 8.3% described using the software to calculate inter-rater reliability. Two articles (4.2%) described using the software to draft memos or data summaries. The remainder did not provide detail on how the software was used (16.7%).

Approaches to data preparation and management in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

Note . Percentages may sum to >100 due to the use of multiple approaches

Data coding and analysis

Coding and consensus.

Double coding of all transcripts was most common by far (47.9%), although a significant proportion of papers did not discuss their approach to coding or the description provided was unclear (31.3%) ( Table 2 ). Among the remaining papers, approaches included a single coder with a second analyst reviewing the codes (8.3%), a single coder only (6.3%), and double coding of a portion of the transcripts with single coding of the rest (6.3%). A related issue is how consensus was achieved among coders. Approximately two-thirds (64.6%) of articles discussed their process for reaching consensus. Most described reaching consensus on definitions of codes or coding of text units through discussions (43.8%), while some mentioned the use of an additional reviewer to resolve discrepancies (8.3%).

Approaches to data coding and analysis in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

Analytic approaches named by authors

As reported in our companion paper, thematic analysis (22.9%), content analysis (20.8%), and grounded theory (16.7%) were most commonly named analytic approaches. Approximately 43.8% named an approach that was not reported by other authors, including inductive analysis, immersion/crystallization, issue focused analysis, and editing qualitative methodology. Approximately 20% of the articles reported using matrices during analysis; most described using them to compare codes or themes across cases or demographic groups (14.6%).

We also examined which references authors cited to support their analytic approach. Although editions varied over time, the most commonly cited references included: Miles and Huberman (1984 , 1994 ); Bernard (1994 , 2002 , 2005 ), Bernard & Ryan (2010) , or Ryan & Bernard (2000 , 2003 ); Patton (1987 , 1990 , 1999 , 2002 ); and Strauss & Corbin (1994 , 1998 ) or Corbin & Strauss (1990) . These authors were cited in over five papers. Other references cited in 3–5 papers included: Lincoln and Guba (1985) or Guba (1978) ; Krueger (1994 , 1998 ) or Krueger & Casey (2000) ; Creswell (1998 , 2003 , 2007 ); and Charmaz (2000 , 2006 ).

Terminology: codes and themes

Given the diversity of definitions for the terms code and theme in the qualitative literature, we were interested in exploring how authors applied and distinguished the terms in their analyses. In over half of the articles, either both terms were not used, or the level of detail provided did not allow for clear categorization of how they were used. In the remainder of articles, we observed two general patterns: 1) the terms being used interchangeably and 2) themes emerging from codes.

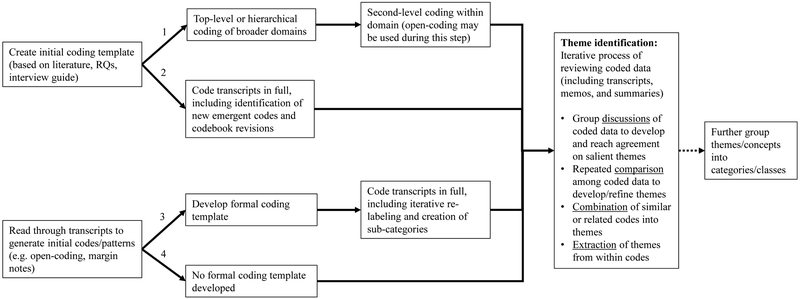

Common analytic trajectories

In addition to examining various aspects of the analytic process as outlined above, we attempted to identify common overarching analytic trajectories or pathways. Authors generally used two approaches to indexing or breaking down and labeling the data (i.e., coding). The first approach (Pathways 1 and 2) was to create an initial list of codes based on theory, the literature, research questions, or the interview guide. The second approach (Pathways 3 and 4) was to read through transcripts to generate initial codes or patterns inductively. This approach was often labeled ‘open-coding’ or described as ‘making margin notes’ or ‘memoing’. We were unable to categorize 11 articles (22.9%) into one of the above pathways because the analysis followed a different trajectory (10.4%) or there was not enough detail reported (12.5%).

Those studies that began with initial or ‘start codes’ generally followed two pathways. The first (Pathway 1; 14.6%) was to code the data using the initial codes and then conduct a second round of coding within the ‘top level’ codes, often using open-coding to allow for identification of emergent themes. The second (Pathway 2; 18.8%) was to fully code the transcripts with the initial codes while simultaneously identifying emerging codes and modifying code definitions as needed. Those that did not start with an initial list of codes similarly followed two pathways. The first (Pathway 3; 33.3%) was to develop a formal coding template after open-coding (e.g., code transcripts in full with an iterative relabeling and creation of sub-codes) and the second (Pathway 4; 10.4%) was to use the initial codes generated from inductively reading the transcripts as the primary analytic step.

From all pathways, several approaches were used to identify themes: group discussions of salient themes, comparisons of coded data to develop or refine themes, combining related codes into themes, or extracting themes from codes. A small number of articles discussed or implied that themes or concepts were further grouped into broader categories or classes. However, the limited details provided by the authors made it difficult to ascertain the process used.

Validity, Trustworthiness, and Credibility

Few papers explicitly discussed techniques used to strengthen validity ( Table 3 ). Maxwell (1996) defines qualitative validity as “the correctness or credibility of a description, conclusion, explanation, interpretation, or other sort of account.” Member checks (18.8%; soliciting feedback on the credibility of the findings from members of the group from whom data were collected ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )) and triangulation of methods (16.7%; assessing the consistency of findings across different data collection methods ( Patton, 2015 )) were the techniques reported most commonly. Peer debriefing (14.6%; external review of findings by a person familiar with the topic of study ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )), prolonged engagement at a research site (10.4%), and analyst triangulation (10.4%; using multiple analysts to review and interpret findings ( Patton, 2015 )) were also reported. Triangulation of sources (assessing the consistency of findings across data sources within the same method ( Patton, 2015 )), audit trails (maintaining records of all steps taken throughout the research process to enable external auditing ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )), and analysis of negative cases (examining cases that contradict or do not support emergent patterns and refining interpretations accordingly ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )) were each mentioned only a few times. Lack of generalizability was discussed frequently, and was often a focus of the limitations section. Another commonly discussed threat to validity was an inability to draw conclusions about a construct or a domain of a construct because the sample was not diverse enough or because the number of participants in particular subgroups was too small. No papers discussed limitations to the completeness and accuracy of the data.

Approaches to establishing credibility, trustworthiness, and reflexivity in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

Reflexivity

Reflexivity relates to the recognition that the perspective and position of the researcher shapes every step of the research process ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 ; Patton, 2015 ). Of the papers we reviewed, only four (8.3%) fully described the personal characteristics of the interviewers/facilitators (e.g. gender, occupation, training; Table 3 ). The majority (62.5%) provided minimal information about the interviewers (e.g. title or position), and 14 authors (29.2%) did not provide any information about personal characteristics. The vast majority of papers (87.5%) did not discuss the relationship and extent of interaction between interviewers/facilitators and participants. Only two papers explicitly discussed reflexivity, positionality, or potential personal bias based on the position of the researcher(s).

The present study sought to examine how the field of health education and health behavior has conducted and reported qualitative analysis over the past 15 years. We found great variation in the type and depth of analytic information reported. Although we were able to identify several broad analysis trajectories, the terminology used to describe the approaches varied widely, and the analytic techniques used were not described in great detail.

While the majority of articles reported whether data were double-coded, single-coded, or a combination thereof, additional detail on the coding method was infrequently provided. Saldaña (2016) describes two primary sets of coding methods that can be used in various combination: foundational first cycle codes (e.g. In Vivo, descriptive, open, structural), and conceptual second cycle codes (e.g. focused, pattern, theoretical). Each coding method possesses a unique set of strengths and can be used either solo or in tandem, depending upon the analytic objectives. For example, In Vivo codes, drawn verbatim from participant language and placed in quotes, are particularly useful for identifying and prioritizing participant voices and perspectives ( Saldana, 2016 ). Greater familiarity with, and more intentional application of, available techniques is likely to strengthen future research and accurately capture the ‘emic’ perspective of study participants.

Similarly, less than one quarter of studies described the use of matrices to organize coded data and support the identification of patterns, themes, and relationships. Matrices and other visual displays are widely discussed in the qualitative literature as an important organizing tool and stage in the analytic process ( Miles et al., 2014 ; Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ). They support the analyst in processing large quantities of data and drawing credible conclusions, tasks which are challenging for the brain to complete when the text is in extended form (i.e. coded transcripts) ( Miles et al., 2014 ). Like coding methods, myriad techniques exist for formulating matrices, which can be used for meeting various analytic objectives such as exploring specific variables, describing variability in findings, examining change across time, and explaining causal pathways ( Miles et al., 2014 ). Most qualitative software packages have extended capabilities in the construction of matrices and other visual displays.

Most authors reflected on their findings as a whole in article discussion sections. However, explicit descriptions of how themes or concepts were grouped together or related to one another—made into something greater than the sum of their parts—were rare. Miles et al. (2014) describe two tactics for systematically understanding the data as a whole: building a logical chain of evidence that describes how themes are causally linked to one another, and making conceptual coherence by aligning these themes with more generalized constructs that can be placed in a broader theoretical framework. Only one study in our review described the development of theory; while not a required outcome of analysis, moving from the identification of themes and patterns to such “higher-level abstraction” is what enables a study to transcend the particulars of the research project and draw more widely applicable conclusions ( Hennink et al., 2011 ; Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ).

All data analysis techniques will ideally flow from the broader inquiry framework and underlying paradigm within which the study is based ( Bradbury-Jones et al., 2017 ; Creswell & Poth, 2018 ; Patton, 2015 ). Yet, as reported in our companion paper ( Kegler et al. 2018 ), only six articles described the use of a well-established framework to guide their study (e.g. ethnography, grounded theory), making it difficult to assess how the reported analytic techniques aligned with the study’s broader assumptions and objectives. Interestingly, the most common analytic references were Miles & Huberman, Patton, and Bernard & Ryan, references which do not clearly align with a particular analytic approach or inquiry framework, and Strauss & Corbin, references aligned with grounded theory, an approach only reported in one of the included articles. In their Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research, O’Brien et al. (2014) assert that chosen methods should not only be described, but also justified. Encouraging intentional selection of an inquiry framework and complementary analytic techniques can strengthen qualitative research by compelling researchers to think through the implicit assumptions, limitations, and implications of their chosen approach.

When discussing validity of the research, papers overwhelmingly focused on the limited generalizability of their findings (a dimension of quantitative validity that Maxwell (1996) maintains is largely irrelevant for qualitative methods, yet one that is likely requested by peer reviewers and editors), and few discussed methods specific to qualitative research (e.g., member checks, reading for negative cases). It is notable that one of the least used strategies was the exploration of negative or disconfirming cases, rival explanations, and divergent patterns, given the importance of this approach in several foundational texts ( Miles et al., 2014 ; Patton, 2015 ). The primary focus on generalizability and the limited use of strategies designed to establish qualitative validity, may share a common root: the persistent hegemonic status of the quantitative paradigm. A more genuine embrace of qualitative methods in their own right may create space for a more comprehensive consideration of the specific nature of qualitative validity, and encourage investigators to apply and report such strategies in their work.

The researcher plays a unique role in qualitative inquiry: as the primary research instrument, they must subject their assumptions, decisions, actions, and conclusions to the same critical assessment they would any other instrument ( Hennink et al., 2011 ). However, we found that reflexivity and positionality on the part of the researcher was minimally addressed in the scope of the papers we reviewed. We encourage our fellow researchers to be more explicit in discussing how their training, position, sociodemographic characteristics, and relationship with participants may shape their own theoretical and methodological approach to the research, as well as their analysis and interpretation of findings. In some cases, this reflexivity may highlight the critical importance of building in efforts to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of their research, including peer debriefs, audit trails, and member checks.

Limitations

The present study is subject to several important limitations. Clear consensus on qualitative reporting standards still does not exist, and it is not our intention to criticize the work of fellow researchers. Many of the articles included in our review were published prior to the release of Tong et al.’s (2007) Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research, O’Brien et al.’s (2014) Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research, and Levitt et al.’s (2018) Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research. Further, we could only assess articles based on the information reported. The information included in the articles may be incomplete due to journal space limitations and may not reflect all analytic approaches and techniques used in the study. Finally, our review was restricted to articles published in HE&B and is not intended to represent the conduct and reporting of qualitative methods across the entire field of health education and health behavior, or public health more broadly. As an official journal of the Society for Public Health Education, we felt that HE&B would provide a high quality snapshot of the qualitative work being done in our field. Future reviews should include qualitative research published in other journals in the field.

Implications

Qualitative research is one of the most important tools we have for understanding the complexity of human behavior, including its context-specificity, multi-level determinants, cross-cultural meaning, and variation over time. Although no clear consensus exists on how to conduct and report qualitative analysis, thoughtful application and transparent reporting of key “analytic building blocks” may have at least four interconnected benefits: 1) spurring the use of a broader array of available methods; 2) improving the ability of readers and reviewers to critically appraise findings and contextualize them within the broader literature; 3) improving opportunities for replication; and 4) enhancing the rigor of qualitative research paradigms.

This effort may be aided by expanding the use of matrices and other visual displays, diverse methods for coding, and techniques for establishing qualitative validity, as well as greater attention to researcher positionality and reflexivity, the broader conceptual and theoretical frameworks that may emerge from analysis, and a decreased focus on generalizability as a limitation. Given the continued centrality of positivist research paradigms in the field of public health, supporting the use and reporting of uniquely qualitative methods and concepts must be the joint effort of researchers, practitioners, reviewers, and editors—an effort that is embedded within a broader endeavor to increase appreciation for the unique benefits of qualitative research.

Common analytic trajectories of qualitative papers in Health Education & Behavior , 2000–2015

Contributor Information

Ilana G. Raskind, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University 1518 Clifton Rd. NE, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA. [email protected].

Rachel C. Shelton, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Dawn L. Comeau, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Hannah L. F. Cooper, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Derek M. Griffith, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA.

Michelle C. Kegler, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Bibliography and References Cited

- Bernard HR (1994). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard HR (2002). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard HR (2005). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (4th ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard HR, & Ryan GW (2010). Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge J, Clark MT, Herber OR, Wagstaff C, & Taylor J (2017). The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: a focused mapping review and synthesis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 627–645. [ Google Scholar ]

- Charmaz K (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbin JM, & Strauss A (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW, & Poth CN (2018). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guba E (1978) Toward a methodology of naturalistic inquiry in educational evaluation CSE Monograph Series in Evaluation. Los Angeles: University of California, UCLA Graduate School of Education. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hennink M, Hutter I, & Bailey A (2011). Qualitative Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kegler MC, Raskind IG, Comeau DL, Griffith DM, Cooper HLF, & Shelton RC (2018). Study Design and Use of Inquiry Frameworks in Qualitative Research Published in Health Education & Behavior. Health Education and Behavior, 0(0), 1090198118795018. doi: 10.1177/1090198118795018 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krueger R (1994). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krueger R (1998) Analyzing & Reporting Focus Group Results Focus Group Kit 6 Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krueger R, & Casey MA (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, Frost DM, Josselson R, & Suarez-Orozco C (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba E (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell J (1996). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1984). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldana J (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, & Cook DA (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med, 89(9), 1245–1251. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton MQ (1987). How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton MQ (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton MQ (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1189–1208. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton MQ (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryan GW, & Bernard HR (2000). Data management and analysis methods In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryan GW, & Bernard HR (2003). Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saldana J (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saldana J, & Omasta M (2018). Qualitative Research: Analyzing Life. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spencer L, Ritchie J, Ormston R, O’Connor W, & Barnard M (2014). Analysis: Principles and Processes In Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nichols CM, & Ormston R (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students & Researchers (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strauss A, & Corbin JM (1994). Grounded theory methodology In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strauss A, & Corbin JM (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (196.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Peer review

- on behalf of the Coproduction Laboratory

- 1 Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 2 Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 3 Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

- 4 Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 5 Highland Park, NJ, USA

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

- Correspondence to: C H Saunders catherine.hylas.saunders{at}dartmouth.edu

- Accepted 26 April 2023

Qualitative research methods explore and provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, including people’s beliefs, perspectives, and experiences. Whether through analysis of interviews, focus groups, structured observation, or multimedia data, qualitative methods offer unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. However, many clinicians and researchers hesitate to use these methods, or might not use them effectively, which can leave relevant areas of inquiry inadequately explored. Thematic analysis is one of the most common and flexible methods to examine qualitative data collected in health services research. This article offers practical thematic analysis as a step-by-step approach to qualitative analysis for health services researchers, with a focus on accessibility for patients, care partners, clinicians, and others new to thematic analysis. Along with detailed instructions covering three steps of reading, coding, and theming, the article includes additional novel and practical guidance on how to draft effective codes, conduct a thematic analysis session, and develop meaningful themes. This approach aims to improve consistency and rigor in thematic analysis, while also making this method more accessible for multidisciplinary research teams.

Through qualitative methods, researchers can provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, and generate new knowledge to inform hypotheses, theories, research, and clinical care. Approaches to data collection are varied, including interviews, focus groups, structured observation, and analysis of multimedia data, with qualitative research questions aimed at understanding the how and why of human experience. 1 2 Qualitative methods produce unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. In particular, researchers acknowledge that thematic analysis is a flexible and powerful method of systematically generating robust qualitative research findings by identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. 3 4 5 6 Although qualitative methods are increasingly valued for answering clinical research questions, many researchers are unsure how to apply them or consider them too time consuming to be useful in responding to practical challenges 7 or pressing situations such as public health emergencies. 8 Consequently, researchers might hesitate to use them, or use them improperly. 9 10 11

Although much has been written about how to perform thematic analysis, practical guidance for non-specialists is sparse. 3 5 6 12 13 In the multidisciplinary field of health services research, qualitative data analysis can confound experienced researchers and novices alike, which can stoke concerns about rigor, particularly for those more familiar with quantitative approaches. 14 Since qualitative methods are an area of specialisation, support from experts is beneficial. However, because non-specialist perspectives can enhance data interpretation and enrich findings, there is a case for making thematic analysis easier, more rapid, and more efficient, 8 particularly for patients, care partners, clinicians, and other stakeholders. A practical guide to thematic analysis might encourage those on the ground to use these methods in their work, unearthing insights that would otherwise remain undiscovered.

Given the need for more accessible qualitative analysis approaches, we present a simple, rigorous, and efficient three step guide for practical thematic analysis. We include new guidance on the mechanics of thematic analysis, including developing codes, constructing meaningful themes, and hosting a thematic analysis session. We also discuss common pitfalls in thematic analysis and how to avoid them.

Summary points

Qualitative methods are increasingly valued in applied health services research, but multidisciplinary research teams often lack accessible step-by-step guidance and might struggle to use these approaches

A newly developed approach, practical thematic analysis, uses three simple steps: reading, coding, and theming

Based on Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, our streamlined yet rigorous approach is designed for multidisciplinary health services research teams, including patients, care partners, and clinicians