Russian Language Learning and Teaching

- Dictionaries

- Online resources

- Where to study Russian language

- Other useful links

Russian Language Textbook Publishers

The largest publishing houses in Russia specializing in Russian as a foreign language:

- Next: Dictionaries >>

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.indiana.edu/c.php?g=447870

Social media

Additional resources, featured databases.

- OneSearch@IU

- Google Scholar

- HathiTrust Digital Library

IU Libraries

- Our Departments

- Intranet SharePoint (Staff)

The Education System in Russia Explained

The education system in Russia is structured to reflect its parallel local and international education systems. With a strong emphasis on STEM subjects and a rigorous examination process, the local education system equips learners for both academic and vocational paths, while its international schools and curricula prepare them for a more global career. How does this mechanism compare to those in the West and what sets it apart? Read on to discover more.

Preschool Education in Russia

Preschool education is not mandatory in Russia. However, over 80% of children aged 1-6 attend some form of preschool. The majority of these institutions are state-run and publicly funded, making preschool education either free or low-cost for Russian citizens. Foreign residents in Russia can also access public preschools, although they might need to navigate some additional administrative processes and limited availability. For instance, although public preschools in Moscow are generally available to foreign residents, they may need to fulfill additional proof of residence processes and compete for limited spots in popular areas. Therefore, some foreign residents opt for private or international preschools, which may offer programs better suited to their needs, such as bilingual education or a curriculum aligned with their home country’s education system.

Like elsewhere in the world, the curriculum in Russian preschools is designed to prepare children for not only the academic but also social environment of primary school, thus focusing on socialisation in addition to the development of motor skills, basic numeracy, language and creativity through a variety of activities.

Improve your grades with TutorChase

The world’s top online tutoring provider trusted by students, parents, and schools globally.

4.93 /5 based on 486 reviews

Primary Education in Russia

Primary education in Russia begins at age 7 and lasts for four years, covering grades 1 through 4. This stage focuses on building a solid foundation in core subjects, ensuring that students acquire essential skills in reading, writing and mathematics. For local schools, the curriculum is standardised across the country, with students typically studying the Russian language, mathematics and introductory science.

Primary education in Russia is offered in both public and private schools. Public schools are the most common and are funded by the government, making them free for all students. These schools follow the national curriculum and are accessible to all children. Private schools, on the other hand, charge tuition fees and may offer additional programs, such as bilingual education or specialised subjects. They often have smaller class sizes and more resources, catering to families seeking a different or more tailored educational experience.

Key aspects of primary education in Russia include:

- Class Sizes: Typically, public school classes are relatively small, averaging 20-25 students per class, allowing for individual attention. Private schools often have even smaller classes.

- Daily Structure: The school day usually lasts four to five hours, with students attending classes five days a week.

- Assessment: Students are graded on a 5-point scale, where 5 is "excellent," 4 is "good," 3 is "satisfactory," and 2 is "unsatisfactory." Regular tests and homework assignments contribute to these grades, which reflect the students' understanding and performance in each subject.

- End-of-Stage Evaluation: While there are regular tests and homework throughout the primary years, there are no formal national exams at the end of primary school. Students are promoted to the next grade based on their overall performance throughout the year.

The primary school environment in Russia tends to be more formal and disciplined compared to Western countries. Teachers are highly respected, and there is a strong emphasis on order and adherence to rules. Unlike in some Western systems, where creativity and independent thinking are strongly encouraged from an early age, Russian primary schools often focus more on mastering the basics and developing good study habits. However, the environment is supportive, with teachers playing a crucial role in guiding students through this formative period.

International Education Options in Russia

Due to the limited international recognition of results in state exams, international schools have become more popular for expatriates and internationally-minded families. Russia offers a range of international education options, particularly in major cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg. According to ISC Research, there are over 50 international schools across Russia. These schools have the following characteristics:

- Language of Instruction: English is typically the primary language of instruction, with additional language support offered for non-native speakers.

- Accreditation: These schools are often accredited by international bodies, ensuring that their education standards are recognised globally.

- Tuition fees : International schools in Russia tend to have higher tuition fees compared to local schools, reflecting their specialised curriculums and smaller class sizes.

These schools provide globally recognised programmes such as the following key options:

- International Baccalaureate (IBDP): Available in several schools, offering a globally recognised diploma that is highly regarded by universities worldwide.

- British Curriculum (A-Levels and IGCSE ): Offered in British international schools, these qualifications are essential for students planning to attend universities in the UK and other Commonwealth countries.

- American Curriculum ( SAT Preparation): Some schools and tutors in Russia offer specific preparation for the SAT, focusing on students aiming for American higher education institutions.

This growing interest in international curricula also led to a rise in demand for specialised international curriculum tutors, such as IB tutors , both online and offline. They help students navigate the challenging curriculum. As more Russian students aim for higher education abroad, tutoring provides them with the skills and confidence needed to excel in an international academic environment.

"IB tutoring in Russia combines global standards with the rigour of Russian education, helping students excel academically and develop strong critical thinking skills," says Elena Ivanova, an experienced Physics tutor .

Vocational Education in Russia

Vocational education in Russia provides an option for students who prefer practical training over the traditional academic route. After completing basic general education, students can choose to study specific skills that are directly applicable to various trades and professions instead of further advancing to secondary generla education. They also have the option to choose a few years later, after they complete their secondary general education, to decide whether to go onto higher education or pursue vocational training.

Key aspects of vocational education in Russia include:

- Types of Institutions: Vocational education is provided by colleges (technikum) and vocational schools (uchilishche). These institutions offer programs that range from 2 to 4 years, depending on the field of study and the level of education completed by the student prior to enrollment.

- Curriculum: The curriculum in vocational schools is a blend of theoretical knowledge and hands-on training. Students spend a significant portion of their time working in workshops, laboratories, or real-world environments related to their field of study. Common areas of focus include technical trades (e.g., mechanics, electricians), service industries (e.g., hospitality, tourism), healthcare, and information technology.

- Certification: Upon completion of their vocational education, students receive a diploma or certificate that qualifies them for employment in their chosen field. These qualifications are recognised across Russia and are often highly valued by employers looking for skilled workers.

- Employment Opportunities: Graduates of vocational schools are well-prepared to enter the workforce immediately. Many programs are designed in collaboration with industry partners, ensuring that the skills taught are aligned with current market needs. This practical focus allows graduates to secure jobs more easily compared to their peers who follow a purely academic route.

- Transition to Higher Education: For students who wish to continue their studies, some vocational schools offer pathways to higher education. Graduates can enroll in universities or technical institutes, often receiving credit for the coursework completed during their vocational training.

Vocational education in Russia plays a vital role in the country's economy by providing a skilled workforce ready to meet the demands of various industries. It offers an alternative to the traditional academic path, giving students the opportunity to pursue rewarding careers in a shorter time frame.

Higher Education in Russia: Degrees and Institutions

Higher education in Russia is well-regarded globally, particularly in fields like engineering, natural sciences, and mathematics. The system is divided into several levels, with the most common degrees being the Bachelor’s , Specialist and Master’s degrees.

Key aspects of higher education in Russia include:

- Bachelor’s Degree: Typically a 4-year program, offering fundamental knowledge in a chosen field.

- Specialist Degree: Unique to Russia, this degree usually takes 5-6 years to complete and is more focused than a bachelor’s degree, often required for specialised professions like medicine, law and engineering. However, while the Specialist Degree is widely recognised in Russia and some other countries, it may be less recognised by Western Europe and North America.

- Master’s Degree: A 2-year program following a bachelor’s or specialist degree, allowing for deeper specialisation.

Russia is home to over 700 universities, with institutions like Lomonosov Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University consistently ranked among the top in the world. These institutions attract both domestic and international students, offering a diverse range of programmes across various disciplines. According to the Ministry of Education and Science, around 4 million students are currently enrolled in Russian higher education institutions.

Challenges and Strengths of the Russian Education System

The Russian education system is known for its strong emphasis on academic rigour, particularly in STEM subjects, which has historically produced experts in fields like mathematics, engineering, and science. This focus on a solid theoretical foundation is a significant strength, providing students with deep knowledge in core areas. Compared to international curricula like the IBDP, A-Levels, or IGCSE, the Russian system offers a more centralised and uniform approach, ensuring consistency across the country.

However, the system also faces notable challenges:

- Creativity and Innovation: The emphasis on standardisation and rote learning can sometimes limit opportunities for creativity and independent thinking, areas where Western education systems often excel.

- Resource Disparities: There is a significant disparity in resources between urban and rural schools, with the latter often facing outdated facilities and a shortage of qualified teachers.

- Pressure and Stress: The intense competition for university admission, particularly in prestigious institutions, places significant pressure on students, contributing to high levels of stress.

Despite these challenges, the Russian education system remains a robust framework that prepares students well for specialised academic and professional careers. However, there is an ongoing need for reforms to address the balance between academic rigour and fostering innovation and creativity.

Conclusion: The Future of Education in Russia

The Russian education system is known for its structured and disciplined approach, particularly in the early years, contrasting with the more relaxed styles often seen in Western countries. This strict environment helps students build a strong foundation in key subjects like literacy and numeracy. Despite this traditional focus, Russia also offers international education options, especially in cities, providing a diverse and globally relevant learning experience. This blend of discipline and flexibility equips students to succeed both locally and on the global stage.

Can international students study in Russian public schools?

Yes, international students can study in Russian public schools. However, they may need to go through additional administrative processes, such as providing proof of residency or obtaining a study visa. Public schools in Russia are generally open to all children living in the country, including those from foreign families. Russian language proficiency is often required, as the majority of instruction is in Russian. Some schools, particularly in larger cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg, may offer specialised programs or bilingual classes that accommodate non-native speakers. It's advisable for parents to contact the school directly to understand the specific requirements and support available for international students.

Are Russian diplomas recognised internationally?

Russian diplomas, particularly those from accredited universities and recognised institutions, are generally respected and recognised internationally. However, the recognition of a Russian diploma may depend on the country and the specific field of study. For instance, degrees in engineering, medicine, and the sciences are often highly regarded. Some countries might require additional certification or an equivalency evaluation, especially for professional degrees. It's important for students planning to work or continue their studies abroad to check the specific recognition criteria in the destination country. Many Russian universities have partnerships with foreign institutions, which can also facilitate the international recognition of diplomas.

What languages are taught in Russian schools?

Russian is the primary language of instruction in schools across the country. However, students are typically required to learn at least one foreign language, with English being the most commonly taught. Depending on the school and region, other languages such as German, French, Spanish, or Chinese might also be offered. In regions with significant minority populations, local languages may be included in the curriculum as well. The study of foreign languages usually begins in the primary grades and continues through secondary education. Some specialised schools and private institutions may offer advanced or bilingual language programs to further enhance students' language skills.

Is there support for students learning Russian as a second language?

Yes, many Russian schools provide support for students learning Russian as a second language. This is particularly true in schools with a significant number of international or immigrant students. Support can include additional Russian language classes, specialised teachers who focus on helping non-native speakers, and tailored learning materials. In larger cities, some schools offer bilingual programs or international curricula that accommodate students who are not fluent in Russian. These programs aim to integrate students smoothly into the Russian education system while helping them achieve proficiency in the language. Parents should inquire directly with schools about the specific support services available.

How do Russian schools handle extracurricular activities?

Extracurricular activities are an important part of student life in Russian schools. Schools typically offer a wide range of activities, including sports, arts, music, and academic clubs. Participation in extracurriculars is encouraged as it helps students develop additional skills, explore their interests, and build social connections. Many schools have dedicated facilities for activities like gymnastics, football, and music. Additionally, students may have access to cultural clubs that promote traditional Russian arts or explore global cultures. These activities often take place after school hours, and some may require a small fee. In larger cities, specialised clubs or private organisations may offer even more diverse options.

Need help from an expert?

Study and Practice for Free

Trusted by 100,000+ Students Worldwide

Achieve Top Grades in your Exams with our Free Resources.

Practice Questions, Study Notes, and Past Exam Papers for all Subjects!

Looking for Expert Help?

Are you ready to find the perfect tutors in Russia? Let TutorChase guide you through every step of the way. Whether you need expert advice on school selection, help with admissions, or top-notch tutoring for exams, we've got you covered.

Professional tutor and Cambridge University researcher

Written by: Vicky Liu

Vicky has an undergraduate degree from The University of Hong Kong and a Masters from University College London, and has a background in legal and educational writing.

Related Posts

The Education System in the UAE Explained

The Education System in France Explained

The Education System in Italy Explained

The Education System in the UK Explained

The Education System in Hong Kong Explained

Hire a tutor

Please fill out the form and we'll find a tutor for you

- Select your country

- Afghanistan

- Åland Islands

- American Samoa

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bouvet Island

- British Indian Ocean Territory

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Cayman Islands

- Central African Republic

- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Congo, The Democratic Republic of the

- Cook Islands

- Cote D'Ivoire

- Czech Republic

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Falkland Islands (Malvinas)

- Faroe Islands

- French Guiana

- French Polynesia

- French Southern Territories

- Guinea-Bissau

- Heard Island and Mcdonald Islands

- Holy See (Vatican City State)

- Iran, Islamic Republic Of

- Isle of Man

- Korea, Democratic People'S Republic of

- Korea, Republic of

- Lao People'S Democratic Republic

- Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

- Liechtenstein

- Macedonia, The Former Yugoslav Republic of

- Marshall Islands

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- Moldova, Republic of

- Netherlands

- Netherlands Antilles

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- Norfolk Island

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Palestinian Territory, Occupied

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- Russian Federation

- Saint Helena

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Saudi Arabia

- Serbia and Montenegro

- Sierra Leone

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

- Svalbard and Jan Mayen

- Switzerland

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Taiwan, Province of China

- Tanzania, United Republic of

- Timor-Leste

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turkmenistan

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- United States Minor Outlying Islands

- Virgin Islands, British

- Virgin Islands, U.S.

- Wallis and Futuna

- Western Sahara

Alternatively contact us via WhatsApp, Phone Call, or Email

Live from Russia!

Welcome to the online component of the Live from Russia! and Welcome Back! textbooks. These sites contain additional resources and teaching material for both teachers and students.

Select your textbook to continue on to that book's website.

This site is a project of the American Councils for International Education

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Slovenščina

- Science & Tech

- Russian Kitchen

What is education in Russia like? A U.S. teacher investigates

A truck arrives at your house. A couple you’ve never met before open the back and begin unloading stacks of broken wood, cracked tiles, dried out plaster, bent nails, stripped screws, used electrical wiring, dented sheets of metal, and a hammer made of hopes and dreams. They say, “Build us a house!”

You do your best. For years, you continue in this Kafkaesque nightmare, more people come with more supplies. You fight fires and floods and you build house after house after house. No one thanks you and most of what you build is shipped away unfinished into the scrapyard of life.

This is what it’s like to be a teacher. Except that, lest we forget, you’re also in a grotesque fairy-tale where planks of wood and strips of sheet-metal have mouths that often bite and sometimes tell you to fuck yourself.

If that seems dreary, try to remember what it felt like to be a pile of stripped screws, bent nails, and scrapped lumber.

‘Sometimes they throw puberty at you’

I’ve taught many Russian students over the years, both in and out of a classroom. In this time, I’ve learned one thing: they are just like students all over the world: they are intelligent and funny and hardworking and yes, sometimes they throw puberty at you.

When I reached out to Russians to discuss their education, I found a genuine concern and a great deal of passion. I expected anecdotes, petty complaints, and conflicting ideologies. What I received was a series of very consistent constructive ideas on where the Russian education system has gone wrong that are well worth ruminating over:

Curriculums are focused more on math and science than on humanities

Despite having one of the highest literacy rates in the world, (~100% compared to the U.S. ~86%) Some of the Russians I spoke to criticize their education system for not focusing enough on humanities:

“About the education system itself I think we have more deep learning in exact sciences (physics, biology, and chemistry are separated) so it explains why there are a lot of Russian hackers and mathematicians.” – Zoe, current high school student in Russia.

“Humanities in general are considered to be the despicable fate of those who are incompetent of doing math and physics. Thus, the technical subjects would be superior, while humanities would serve as leftovers.” – Ulia, graduated from high school in 2015.

However, not everyone agrees. One highschool biology teacher has found that students are much more likely to excel in history over math and science:

“Most students do not know biology, chemistry, or physics very well. I am preparing some of them for exams, so I know firsthand. Meanwhile, judging by my experiences with Russian students, they're better in history. It's hard to say on what Russian schools focus. School in the USSR were good in math and geography, but now there are too many old teachers who have problems with computers and the internet. On the other hand, there are some really good schools in cities.” – Evgeny, highschool biology teacher in Russia.

There’s a lack of critical thinking and personal expression:

When I was in high school critical thinking was lauded as an essential aspect of education. I was taught to think and be critical of everything; except my teachers, the textbook, my homework, the school, my parents, the principal – it was most important to be critical of authority that was very far away, or dead.

“Compared with my experience with American universities (I know some people who teach students) — on subjects like social studies, history, etc. we almost never wrote papers that were aimed at expressing our thinking, and Americans do it all the time. We were, like, “This scholar wrote that…,” and here you effectively summarize their opus magnum, or “There are two approaches to this problem: first, …, and as opposed to this, there’s another view...” Very rarely it was required that a student actually expresses their own stance and argue it.” – Nadja, studied in Russia in the early 2000s.

READ MORE: What were Russian kids in the 20th century told about sex?

“Russian education does not seem to facilitate personal or professional development of a child, but rather holds an ambition of bluntly transitioning the facts written in a Soviet textbook into a student’s head…The complete absence of critical thinking is probably the most obvious problem in Russian schools. We are taught what to think, not how to think, which is exactly the opposite of what education should be about.” – Ulia, graduated from high school in 2015.

“Trying to teach you how to think critically is a rare thing, even if a teacher is a young enlightened person, he/she cannot do anything with that due to the staff and curriculum. Trying to make some real sense is a straight path to being fired. So, yeah, the educational system is outdated, it doesn't do its work as it did in the USSR, times have changed.” – Denis, taught biology to Russian students in Grades 5 and 9.

There’s a lack of choice for Russian students to explore new subjects

“In Russian high school you generally can’t pick subjects and make up your own schedule. You have a fixed schedule, with different subjects every day, you have a paper school diary where you write that schedule and write down your homework assignments… In the U.S., I could pick any subjects that I like, as long as combined they give you at least the minimum amount of credit required to pass the term. I liked this approach: I picked AP calculus and AP physics because I liked math, and I didn’t have to torture through chemistry or biology or art or any other subject I find excruciatingly boring.” – Ilya, studied in USA and Russia.

“In my time, Russian school education had little to no subjects by choice, and you had to complete bare minimum courses in math, physics, chemistry, astronomy, and other stuff that you may or may not need. That seems like a waste of time and effort for vertical education evangelists, but actually this basis provides you a better catch-all foundation for broad horizons, system thinking and teaches you to see connections between things.” – Nadja, studied in Russia in the early 2000s.

What are teachers like in Russia?

“The last but not the least – the attitude. The teacher is always right. They can easily call a student an idiot, an imbecile, an incompetent nobody – that is common practice. The children are shown that they can be treated like shit by the more powerful others and do nothing about it. Of course, there are great teachers with true love for education and children, but they are more likely to be an exception rather than the norm. Education is our past, present, and most importantly, our future. It demands a drastic transition.” – Ulia, graduated from high school in 2015.

“Well, it's more about respect as you said, not discipline. Quite often teachers (usually ones from the Soviet era) are really conservative like Putin is the only true leader, women have to care more about the family than the career and stuff, and it’s hard to find the line between respectful disagreement and being a moron.” – Zoe, current highschool student in Russia.

“If we talk about the learning process itself, then in the West the teacher tries to be a friend and person, then in the Russian school teachers are often fenced off from students by the severity and the need to complete tasks.” – Nika, University Student Studying Technology.

Many teachers are underpaid and unmotivated

One of the other most consistent comments I received rings true all over the world: if we continue to pay teachers below-par salaries, future generations will suffer.

“But, the one big ‘but,’ is the salary. Teachers, such important people in people’s lives, still get low salaries. It's just barely possible to stay positive and spread joy in such conditions for a long time, you know. You just must be created for that to carry on like this long-term.” – Denis, taught biology to Russian students in Grades 5 and 9.

“Teaching is not a well-paid job in Russia, so people who really want to earn money don't work in education. Which means those who stay in education, whether they really like it or just want to torture other people. Unfortunately, those who like teaching can't last long at schools or universities and they leave the field, disappointed.” – Daria, graduated high-school in 2007.

READ MORE: Which Russian universities produce the most billionaires?

It fascinates me that policy makers allocate funds to make schools more high-tech without understanding a simple truth about education: a great teacher can impart far more with a stick and a pile of sand than a bad teacher with all of the iPads in the world.

I’m one of those foolish people who believe that education is the key to solving the world’s problems, but this means money needs to be better spent.

In America, we have a yearly budget for education that amounts to $68 billion. In Russia, the yearly budget for education is $10 billion. If we stack these numbers up against American and Russian military budgets, we get a good idea of our countries’ priorities: Russia: $69 Billion. America: $600 billion.

So, here is my wild idea:

Why doesn’t the world spend some of the money it uses to kill each other to compensate compassionate, well-educated teachers who are the only ones who stand a chance at raising a new generation of people who might not want to kill each other as much. Perhaps this would grant the world more parents who admire teachers, rather than think they know better; students who are eager to attend classes and learn, rather than wallow in boredom and resentment; and policy makers who understand the value of a mentor and guide in education, rather than our medley of politicians with their thumbs up their asses.

But what do I know, I graduated from public school.

Benjamin Davis , an American writer living in Russia, explores various topics, from the pointless to the profound, through conversations with Russians. Last time he explored what Russians think of guns . If you have something to say or want Benjamin to explore a particular topic, write us in a comment section below or write us on Facebook .

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox

- Russian feminists fight not only for their rights but also for the right words

- ‘F*ck the weather’: This is why there’s no small talk in Russia

- Before and after: How the Russian army changes soldiers (PHOTOS)

This website uses cookies. Click here to find out more.

General Education in Russia During COVID-19: Readiness, Policy Response, and Lessons Learned

- Open Access

- First Online: 15 September 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Sergey Kosaretsky 2 ,

- Sergey Zair-Bek 2 ,

- Yuliya Kersha 2 &

- Roman Zvyagintsev 2

25k Accesses

6 Citations

4 Altmetric

In this chapter, we analyze nationwide measures taken in Russia to organize the education system during the pandemic. We show the opportunities and limitations for responses associated relative to the previous policy phase. Special attention is paid to the peculiarities of a system reaction to the situation of a pandemic in a federative country with heterogeneous regions. In contrast to several other countries that adopted a single national strategy, different scenarios were implemented in Russian regions. We investigate the factors that influenced the scenarios and management decisions at the national and regional levels of the country. We highlight differences in the nature and dynamics of measures taken to organize learning in the first (spring–summer 2020) and second (autumn–winter 2020) waves of the pandemic. We also analyze the subjective experience and wellbeing of students and teachers during a pandemic. As the empirical base, we use data from several large sociological studies conducted in the Russian Federation over the past six months on the issues of school closures, distance learning, and the “new normal.” This provides a new perspective for studying the increasing education gap between children with different socioeconomic status due to the pandemic.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Post-Pandemic Crisis in Chilean Education. The Challenge of Re-institutionalizing School Education

Argentina: Improving Student School Trajectories

The Education System of Venezuela

9.1 introduction.

The COVID-19 pandemic posed an unprecedented challenge to over 44,000 schools, 16.3 million students, and 2.16 million teachers in Russian schools (Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation, 2020a ). The government has had to solve the complicated problem of providing constitutional guarantees of universal free secondary general education while minimizing the immediate health risks for students and teachers as well as the spread of infection through schools.

In this paper, we describe the situation in which the Russian education system found itself during the COVID-19 pandemic and the education policy measures adopted by the government at the federal and territorial levels. We examine the contextual factors that influenced decision making and reflected the specifics of the country’s territorial structure and education management system. We highlight the differences between measures for ensuring the functioning of the education system during the first and second waves of the pandemic and their dependence on the epidemiological situation. Lastly, we discuss the impact and lessons learned from the experience during the pandemic for student quality and wellbeing and the future development of the education system (including policies aimed at families and teachers, digitization, and management models).

The empirical section of the chapter focuses on the subjective wellbeing (SWB) of Russian schoolchildren during the quarantine. We consider this topic to be especially important in the representation of the Russian case because: (1) the topic of subjective wellbeing as a part of the educational process and results has been traditionally ignored by Russian educational policy; (2) subjective wellbeing in the Russian Federation is on average lower than the OECD average (OECD, n.d.); and (3) in the context of a pandemic, subjective wellbeing may be a significantly more important indicator of how well an education system is doing. In addition to a general analysis of the factors associated with subjective wellbeing during school closures for quarantine, we focus on inequality in subjective wellbeing—what happens to children with different socioeconomic status? Against the background of increasing inequality in educational outcomes amidst the pandemic, it is critical for us not to overlook any possible widening gap in subjective wellbeing as this could be a much more dangerous effect of the pandemic on the education system.

9.2 Methodology, Data, and Limitations

We use Russian federal statistics on education and related indicators, such as demographic and economic ones, to identify and describe the context of the education policy. To analyze the administrative decisions adopted for mitigating the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, we drew upon open sources (official websites of national, regional, and municipal government agencies, school websites, and mass media) and interviews with different regional and municipal government officials (over 20 full-length online interviews through Skype). These interviews were conducted by the Higher School of Economics Institute of Education during the period March–October 2020. To assess the readiness of teachers, students, and families for distance learning, we used the results of international studies such as PISA and TALIS (OECD, 2018 ). To study changes in teaching and learning practices, the labor and living conditions of teachers and students, and the reaction of families to the new study regime, we used the results of sociological surveys administered by governmental and non-governmental organizations, including the School Barometer International Study (Isaeva et al., 2020a ).

The goal of the empirical part of the study was to identify and compare the level of subjective wellbeing of Russian schoolchildren before school closures in the spring of 2020 and at the present time (winter 2020). We use data from a study by the HSE Institute of Education. The data was collected in November–December 2020. To assess the situation before the first school closures in spring 2020, we employed retrospective questions about the students’ state at that time.

The survey examined four Russian regions: Moscow, Kaliningrad, Leningrad, and Tyumen Regions. The sample of education organizations within each region was stratified by the type of locality (urban or rural) and the socioeconomic status of the school (low, middle, high). The stratified random sample was selected among all the schools of these regions with the help of information obtained during previous studies on the quality of education (e.g., number of computers). The final sample of the present study comprised 7,355 students between the ages of 8 and 19 (grades 4–11) from 99 Russian schools in the Moscow, Kaliningrad, Leningrad, and Tyumen Regions.

The student questionnaires included questions about students’ main socio-demographic and economic characteristics (age, gender, parents’ higher education, home possessions), their subjective wellbeing before the closure of schools and at the present time (identical set of questions about the periods “before” and “after”), and their ways of interacting with school during the absence of face-to-face education. In addition to the students’ answers, the survey made use of school-level variables: share of teachers with the higher qualification category; number of computers connected to the internet per student; percent of students whose parents have a higher education; and type of school area (urban or rural).

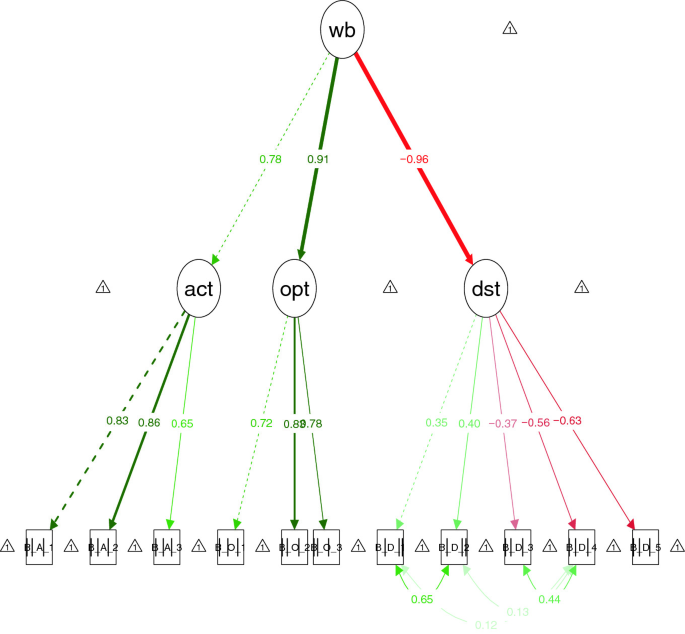

We based our questionnaire on a combination of instruments to assess the subjective wellbeing of schoolchildren: Holistic Student Assessment (Malti et al., 2018 ) and assessment of students’ distress level (Goodman, 2009; Brann et al., 2018). According to the theoretical framework, student subjective wellbeing includes several components, of which the following were used in the present study: (1) orientation on physical activity, (2) optimism, and (3) level of distress. We assume that these components are especially important in the context of a pandemic when students may suffer from anxiety and the lack of physical activity. To measure the level of each component, the questionnaire presented 3–5 different statements with responses on an ordinal scale. Some respondents who provided identical responses to all questions were excluded from the analysis. Hierarchical confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to calculate the overall indicator of subjective wellbeing. We tested a theoretical two-level model, where the first level measured the orientation on physical activity, optimism, and stress level, while the second level measured subjective wellbeing. The results of our analysis confirmed the high quality of this model for two cases: before and after the closure of schools (Appendix 1). The resulting values of the subjective wellbeing score and its components before and after the closure of schools were then used for the purpose of further analysis.

To compare the level of subjective wellbeing of the same students in the studied regions before and after the closure of schools, we made a pairwise comparison of indicators using the t-test for dependent samples. A similar methodology was used to check if there were any differences in the change of subjective wellbeing during the period of pandemic for students with different amounts of home possessions. Using descriptive analysis, we examine how students communicated with their schools during the pandemic. The next step was to use multilevel modeling to assess individual and school factors connected with student SWB before and after school closures and with its variation over the period in question. To assess the changes in subjective wellbeing, we subtracted the current value of the level of wellbeing from its level before school closures. During the final stage, we used ANCOVA analysis to compare the mean indicators of subjective wellbeing in four regions while controlling for significant relevant individual and school factors. The inclusion of covariates in the analysis led to a better assessment of the differences connected directly to regional factors rather than to the students’ family or school.

9.3 The Russian Education System in the Face of the COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic

To understand the reaction of the Russian education system to the pandemic, we must consider how education policy measures are discussed and implemented at the federal and regional levels. First and foremost, Russia’s vast territory and heterogeneous spatial development led to significant differences in both the infection rate and the readiness to organize education activities during a pandemic throughout Russian regions (Mau et al., 2020 ; World Bank, 2018 ).

Russian indicators of “computerization” and “connection of schools” to the internet are above the OECD average (OECD, 2018 ). At the same time, the speed of broadband internet connections is lower in Russia than the world average, amounting to 45 Mbps. Only 76.9% of Russian households have access to the internet, and only 73.6% of them have access to broadband internet (Information Society in the Russian Federation, 2020 ). A favorable situation exists in approximately 40% of Russian regions as they have high indicators in both factors (availability of high-speed internet and computer technologies).

Russian regions have different levels of urbanization. Some regions, especially in Siberia and the Far East, have large numbers of small settlements with a poorly developed digital infrastructure. School students living in these areas experienced the greatest difficulties in distance learning. At the same time, the remoteness of villages and the small size of schools were grounds for keeping schools open in those regions.

Difficulties with organizing distance learning disproportionally affected economically disadvantaged and multi-child families. About 4 million economically disadvantaged individuals in Russia are schoolchildren between the ages of 7 and 16. Every sixth Russian inhabitant between the ages of 0 and 17 lives in a multi-child family. The different distributions of these families across regions led to various difficulties in providing such children with computer technologies. The problems were particularly acute in North Caucasian regions and several regions in Central Russia, including the Moscow and Leningrad Regions. In contrast, the cities that formed the nuclei of these regions (Moscow and Saint Petersburg) did not suffer from such difficulties. Different resource availabilities in cities and their surroundings contributed to the growing inequality of school students during the pandemic.

In terms of distance learning infrastructure, different collections of digital resources and the Russian Electronic School national distance learning platform had been created at the federal level before the beginning of the pandemic. Some regions had also set up their own digital platforms and services that could be used for distance learning; the best-known example is the Moscow Electronic School. In recent years, a market has emerged of private digital education resources and services for both distance and blended learning. Contracts with various digital platforms have been signed by separate regions, municipalities, and general education organizations, giving them an advantage during the pandemic.

Another major factor was the federative structure of the state and the division of responsibilities between federal executive agencies, regions, and municipalities that hindered the implementation of a unified state strategy for the entire school system. Most schools in Russia are managed by local municipal agencies. Free schooling in Russia is financed by regional governments. The maintenance and renewal of school property (buildings, equipment, etc.) is financed by local municipal agencies. Federal education management agencies set the standards for education outcomes and the conditions that must be met to attain them. The federal government also sets the principal models for organizing the system’s work, including the assessment of education quality, the professional development of teachers, the organization of inclusive education, digitization, etc.

During the pandemic, this distribution of powers resulted in the following situation: the Federal Ministry of Education established the general principles for education organizations (banned mass events, created norms of social distancing, etc.), implemented national measures (launched digital platforms with learning and teaching materials, organized televised lessons), changed the dates and form of the state final certification, and monitored measures taken at the territorial level. At the same time, decisions on extending vacations, closing/opening schools, and classes, fixing the end of the school year and other organizational matters were made at the regional and municipal levels. Regions and municipalities were responsible for assuring the digital infrastructure such as the availability and quality of internet access as well as the provision of PCs and laptops to teachers and students. It frequently turned out that the regions with the least financial resources for solving these problems were the same regions with the greatest needs.

In addition to the distribution of managerial powers, there is relevant background of relations between federal and regional government agencies. Over the past 5 years, the Federal Ministry of Education has de facto centralized decision making and limited the autonomy of regions in choosing the subjects and development models of general education. For this reason, after the pandemic began, many regions waited for instructions from the federal ministry. Nevertheless, the latter stressed the rights and responsibilities of regions in deciding which measures should be taken in response to the pandemic. This was quite unexpected for some regions.

9.4 Education Policy at Different Levels During the COVID-19 Pandemic: General Trends

The first cases of COVID-19 were recorded in Russia in February 2020. The disease began to spread in early March 2020. The development of the epidemic corresponded to the widespread international model of two disease waves and peaks. The first peak of the epidemic (11,656 new cases daily) occurred in early May 2020. The incidence of the disease subsequently fell until September 2020. This was followed by the second wave of the pandemic between September and December 2020 with a peak (29,935 new cases daily) before the beginning of the winter holidays and school vacation.

The strategy of the Russian education system differed considerably between the two waves of the pandemic. During the first wave, a nationwide lockdown was introduced for all intents and purposes, and most schools switched to distance education. During the second wave, the restrictions greatly differed from region to region, and most schools remained open.

Moreover, as our study shows, school closures during the quarantine had little to do with the real incidence rate of the disease (see Fig. 9.1 a,b). Due to the limited access to data on the incidence rate of the disease among children and on the impact of school closures on disease incidence, the decisions to close schools for quarantine or switch to distance study were made based on general federal policy.

a New cases of disease and the number of schools closed for quarantine during the first wave of the pandemic. b New cases of disease and the number of schools closed for quarantine during the second wave of the pandemic

After the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing enacted rules for the organization of educational activities after the quarantine, including cancelling mass events, dividing classes (to limit contact), implementing disinfection measures, and introducing special measures during the state final certification.

The Russian Ministry of Education initiated and/or supported the following key organizational and technological solutions:

Cancelling the unified final state certification after the 9th grade

Postponing the dates of the unified state exam (USE) after the 11th grade

Cancelling the USE for students who do not plan to enter university

Hotlines for school directors and regional education management agencies to answer questions about the organization of distance learning

TV projects for senior high school students for broadcasting lessons

Providing schoolchildren from particularly disadvantaged families with computers for distance learning

The Russian Ministry of Education allowed regions to make their own decisions based on the local epidemiological situation about the partial premature termination of the school year and about extending school vacations and changing quarantine regimes. The Russian Ministry of Education also introduced several distance learning platforms from which regions could choose.

Nevertheless, these support measures did not work immediately. Each region had to make its own choice based on different factors. In some cases, regional education management agencies announced the early termination of certain (non-core) classes for students in grades 1–8. This led to the reduction of study loads and internet traffic. This took place in some Siberian regions and regions along the Volga River.

Several regions signed special agreements with internet providers for delivering internet services at reduced rates or free of charge and using secondary regional resources for distance learning needs. They also signed agreements with mobile network operators for lower internet rates and special packages for teachers and students. Some regions also used various other mechanisms such as creating mirror sites and hosting education resources. In some regions, internet providers offered internet traffic for distance learning at low rates or virtually free of charge to economically disadvantaged families. Several private online platforms (Yandex Textbook, Uchi.ru) provided free content to support schoolchildren and prevent academic lag.

The lack of computers in families for organizing distance study was compensated by different regions in various ways. In some areas (such as the Moscow Region), school notebooks were offered to families. Other regions (such as the Republic of Sakha-Yakutia) bought computers to offer them to families. In Saint Petersburg and other regions, computers for families were bought with the help of sponsors. Finally, as we mentioned above, the federal government launched a fundraising campaign for purchasing computers for families in need.

To help teachers organize the study process from home, some regions offered school computers to teachers and provided them with technical assistance in configuring home computers and connecting them to the internet. The federal government implemented the project “Education Volunteers,” in which senior students from teaching colleges helped teachers who were unfamiliar with computer technologies to master the basics of organizing distance learning.

In many regions, education development institutes and municipal curricular offices helped teachers by offering express courses and consultations on working in the new format, recorded video guides and training webinars, opened tutor centers, and organized consulting by curricular association directors and teachers who had won professional competitions. Other regional initiatives catered to parents. Hotlines were setup to consult and assist both parents and children using the new distance learning format. These hotlines were staffed by specialists from education management agencies, education psychologists, school counselors, and teachers. In different regions, schools provided support for low-income families distributing food products and even ready meals.

The regions that were the best-positioned to deal with COVID-19 had prior experience in organizing distance learning in bad weather conditions. In these regions, online study was quickly and efficiently deployed, while teachers were much better prepared for the distance learning format. The same was true of individual education organizations that had already begun to develop digital environments before the pandemic, actively used electronic agendas, maintained up-do-date sites stocked with different content, and participated in social media groups. All these instruments were easily adapted to serve the needs of distance learning.

As the first wave of the pandemic showed, distance learning was best organized in territories in which regional and local management teams took the initiative without waiting for directions from federal education management agencies.

All schools in Moscow and the Moscow Region were given the opportunity to work on a high-quality platform with a full range of content. The Republic of Tatarstan invited its schools to use several different education platforms simultaneously for different subjects and grades. At the same time, internet access was almost completely lacking in rural schools in several South Siberian regions, forcing teachers to bring homework assignments to collection points (such as village stores), from where they were gathered by parents and students. Some regions in the Far East, South Siberia, and Far North organized education with the help of televised educational programs.

No analytic or preparatory work for the new school year was conducted during the summer holidays (June–August). No nationwide programs for improving the availability and quality of internet access and computer technologies were implemented, either.

During the first wave of the pandemic in the spring, many parents, teachers, and education managers at different levels believed that the pandemic was a temporary emergency that would soon end without requiring the education system to make any major changes. Some parents, teachers, and students did not believe in COVID-19 or considered its danger to be greatly exaggerated. The skeptical attitude of some teachers, parents, and schoolchildren to the risks and dangers of the pandemic, especially during the first wave in the spring, as well as the belief that the quarantine would not last long led to a certain inertia and reactionism of managerial decisions.

Interviews with officials of regional and municipal education management agencies have shown that the uncertainty and lack of clear forecasts about the development of the pandemic, especially during its initial period, led regions and schools to take quick short-term measures. These measures had small time horizons and were based on the expectation of a rapid return to the usual format of face-to-face learning. The distance learning format was viewed as a temporary emergency measure that did not require any major investments of resources. In addition, the tendency to downplay the pandemic and its consequences for schools was also linked to the lack of clear and unambiguous instructions from the federal government by the respondents. The freedom allotted to regional, municipal, and school managers to take their own decisions was often interpreted as a sign that the federal government did not know what to do in the circumstances. On the other hand, the lack of control from above was seen as an opportunity to avoid “awkward” measures that could irritate parents, teachers, and students.

Due to the increased loads during the distance learning period and the prolongation of the school year, teachers were given an additional leave before the start of the new school year. Most teachers, parents, and students expected the school year to start in the traditional place-based format. Regions partially implemented local preparatory measures for preparing schools for the school year: renovating and re-equipping buildings, providing high-speed internet access, and training teachers.

Second wave

In October, it became clear that the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic had already begun in Russia. Federal government agencies had not issued any teaching or organizational recommendations by the beginning of the second wave, stressing that regions should make all managerial decisions on their own. Only in early October did the Russian Ministry of Education elaborate and publish recommendations on amending study programs in view of the coronavirus infection and recommendations on using information technologies (Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation, 2020c , d ). The Ministry published practical recommendations on organizing the work of teachers in the distance learning format only in November (Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation, 2020b ). In these conditions, regions continued to provide curricular support to schools and train teachers on their own.

The second wave was a lot more extensive and serious than the first. The prevalence and incidence rate of the disease increased. Nevertheless, this situation did not lead to the mass transition of the education system to the distance learning format, as had been the case during the first wave (Fig. 9.2 ).

Distribution of place-based and distance learning formats in the Russian Federation in October–November 2020 (Mertsalova et al., 2021 )

In October–November 2020, 55 regions kept schools in the place-based format (with isolated transitions to quarantine regimes and distance learning when the minimum prevalence rate of the disease was surpassed), while 30 regions made a partial transition to the distance learning format. While different regions put different grades into distance learning, almost none of them applied this measure to primary schools; the mass distance learning format also did not affect schools with small student bodies, as a rule. 70% of schoolchildren continued to study in the place-based format in October–November. Only 0.1% of all schools were closed entirely for quarantine. Footnote 1

By late December, the total number of closed schools had decreased, even though the incidence rate of the disease continued to grow. Only 64 schools in 20 regions were still closed (0.16% of all schools) in late December (Fig. 9.3 ).

Prolongation of fall break in Russian regions (Mertsalova et al., 2021 )

At the same time, some regions with high incidence rates did not adopt distance learning. 37 regions did not extend the fall break, while 48 regions extended the fall break by 1–3 weeks. Vacation prolongation was the most widespread anti-pandemic measure in Russian regions (a prolongation of 2 weeks in 40 regions and 3 weeks in 8 regions). Once again, many regions with high incidence rates refused to prolong school vacation, and only 39% of regions with high incidence rates converted schools to distance learning. Moreover, regions with similar conditions sometimes took different decisions. For example, Moscow put middle and high school students on distance learning, while Saint Petersburg retained place-based education for all schoolchildren, even though the incidence rates and risks of infection in Saint Petersburg were no lower than in Moscow. In some cases, parental protests over distance learning along with electoral worries discouraged government officials from making changes. Parental anxieties grew despite repeated assurances that distance learning would not be introduced under any circumstances (Kommersant, 2020 ). Thus, anti-pandemic measures during the second wave were chosen more based on social and political factors than objective assessments of the risks.

An important role was played by political signals from the federal center based on fears of aggravating social and economic problems due to the pandemic. Another major factor was growing popular discontent. Parents’ tensions and mistrust of the distance learning format grew as the pandemic progressed. A survey conducted in mid-April showed that 63% of parents believed that schools had successfully shifted to distance learning, while 17% of parents disagreed (Public Opinion Foundation, 2020 ). In a survey in May, 55% of surveyed parents of final-year students expressed their discontent with the organization of distance learning (Rambler News Service, 2020 ). By the start of the following school year, 93% of parents believed that study should be implemented in a place-based format. This was motivated by the assertion that face-to-face study allows children to communicate and socialize (30%) and leads to better education quality (20%), better knowledge (17%) and direct contacts with teachers (16%); in addition, parents believe that they cannot educate their children as well as teachers (14%) (Russian Public Opinion Research Center, 2020 ). Some mass media even launched an information campaign claiming that the government was planning to abandon place-based education altogether after the end of the pandemic.

9.5 Consequences and Lessons of the Coronavirus Pandemic

The experience of transforming the general education system in Russia in the conditions of the pandemic has produced important consequences and lessons for the development of Russian education both today and in the future. Russian experts agree that the reorganization of education during the pandemic, especially during the first wave, led to losses in the quality of education on account of changes in the employed technologies and the reduction in study time (due to prolonged vacations as well as schools and classes put in quarantine). With regards to technology, distance learning is not yet fully able to replace face-to-face learning, according to most teachers, parents, and students. Many distance lessons have suffered from poor quality, simplified content, and the lack of interactivity and feedback. The reduction in study time depended on the school and the subject. Subjects calling for student participation (physical education, art, music, technology, etc.) were particularly affected.

At the same time, the national system for education quality assessment does not provide open data about education losses, as we have already mentioned. According to World Bank forecasts, Russian schoolchildren will lose about 16 points on the PISA reading score or 1/3–1/2 year of study on average (World Bank Group, 2020 ). The Ministry of Education postponed the annual national tests (taken by all school students simultaneously and in the same format) from April to the beginning of the school year to serve as “initial assessments that would be used to correct the study process” (RG, 2020 ).

The very idea of conducting a monitoring and diagnostic study of the readiness of students for the new school year and their academic lag due to the extraordinary study circumstances in March–May 2020 was considered very important for both theoretical and practical reasons. The large sample (6 million people) could have been used to identify typical problems and difficulties faced by students and elaborate recommendations for teachers on the format of curricular materials for place-based and distance learning formats. The analysis of the identified problems could have also served as a guideline for private producers of educational content, including designers of digital platforms. However, no analysis of the sort was conducted, and the results were neither discussed by the expert and teacher communities nor used as sources for planning teacher retraining courses and the work of education psychologists. The Ministry’s methodological recommendations invited schools and teachers to analyze the results of the national tests themselves and to submit within two weeks a proposed scheduled of working with students experiencing academic problems (Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation, 2020e ). Thus, the national tests led to an additional workload being put on teachers in the absence of all informational and curricular support from the federal government.

During the first semester of the new school year, no national measures (extra classes, prolonged school year, vacation programs, etc.) were taken to compensate for losses in education quality that affect student trajectories and labor market prospects, despite recommendations by international organizations (UNESCO, 2020 ). Our analysis shows that few regions and schools implemented such measures at their own initiative. The introduction of such measures aimed both at students completing school during the current year as well as planning to enter vocational colleges and universities and at the entire student body that has been adversely affected by the pandemic remains a key yet open item on the agenda.

Another major negative consequence is the deterioration of the subjective wellbeing and psychological health of students because of the adverse impact of living conditions during the pandemic (including the lack of social interaction, face-to-face communication between children, and communication between children and adults during mutual activities; strained family relations; reduced physical activity; and significantly reduced external support for study). 78% of surveyed parents spoke about the growing discomfort of their children due to the lack of communication with peers, noting that this is a very important function of school. Only half of surveyed parents (49.3%) said that teachers interacted with pupils in the distance learning format and organized direct communication. A similar share (49.6%) noted that teachers provided feedback to students about study and assessment results (Isaeva et al., 2020a ). Psychological problems resulting from self-isolation and distance learning were found among 83.8% of Russian schoolchildren: 42.2% purportedly suffered from depression and 41.6% from asthenia (TASS, 2020 ).

In the context of the data already available, we decided to conduct a separate study. We were less interested in the absolute picture of the subjective wellbeing of schoolchildren than in whether the patterns of changes differ for children with different SES. Additionally, we looked for indirect evidence of whether schools “lose” children during quarantine by examining the characteristics and frequency of interaction between the school and the child.

Subjective wellbeing and psychological health of students

Researchers now predominantly ignore such topics, focusing instead on the analysis of objective losses in the quality of learning due to digital inequality (Engzell et al., 2020 ; Robinson et al., 2020 ; Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020 ). They disregard the theme of subjective wellbeing, although psycho-emotional problems due to school closures, lack of traditional summer vacations, illnesses of close relatives, and an uncertain future may have an even bigger impact on students (Ghosh et al., 2020 ). At the same time, certain international monitoring studies (OECD, 2017 ) assess subjective satisfaction with life. Promoting subjective wellbeing is the third of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2020 ). This is particularly relevant during worldwide pandemics such as COVID-19. In the present study, we analyze contextual factors at the school and individual levels related to different SWB trends of Russian school students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The notion of wellbeing is understood in different ways depending on the context. However, it is clear that wellbeing is a complex notion that cannot be measured by a single indicator (Borgonovi & Pál, 2016 ). Wellbeing studies traditionally examine all participants of the educational process—children (Yu et al., 2018 ), parents (Buehler, 2006 ), teachers (Mccallum et al., 2017 )—and the connections between them (Casas et al., 2012 ; McCallum & Price, 2010 ). In the OECD framework, wellbeing comprises 11 indicators, including personal security and social connections (OECD, 2017 ). In this paper, we focus only on subjective wellbeing, ignoring other dimensions such as health. We define wellbeing as “the assessments, whether positive or negative, that people make of their own lives” (Diener, 2006 ).

Many organizations, besides OECD, make international comparative studies about the contextual factors that determine the subjective wellbeing of school students. For example, a study by Korean scholars shows that subjective wellbeing is best predicted by variables from the micro level of children’s life (family, school and close community), while economic and broader national contextual factors are less or not at all significant (Lee & Yoo, 2015 ). However, another study shows that national factors are, on the contrary, quite important: the better the public health, material wellbeing, and education system in a country, the higher the children’s subjective wellbeing (Bradshaw et al., 2013 ). At the same time, the comparison of rural and urban territories within a single country traditionally shows that rural children have a higher level of subjective wellbeing (Gross-Manos & Shimoni, 2020 ; Rees et al., 2017 ). Nevertheless, this trend may only apply to countries with a sufficiently high overall standard of living in rural areas (Requena, 2016 ).

Regarding studies of the impact of inequality (whether economic or territorial) on the subjective wellbeing of children, a survey of 15 different countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa demonstrated a positive connection with a child’s home possessions yet no connection with economic inequality indicators at the national level (Main et al., 2019 ). Studies of so-called “rich societies” paint a different picture: the wellbeing of children at the national level is connected with the level of economic inequality in a country yet not with the mean wage (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2007 ). At the same time, other studies show that the lower the general socioeconomic level of the neighborhood in which children grow up, the lower their subjective wellbeing (Laurence, 2019 ). However, this paper indicates that there is no direct connection here: disadvantaged communities have more negative and fewer positive social interactions, which results in lower wellbeing (Ibid.).

Researchers from Yale University and Columbia Business School show that the higher the income inequality in a country, the higher the level of subjective wellbeing. Although this does not directly apply to children, it is an important consideration since the authors conduct an extensive analysis of the contradictory nature of statistics in this field (Katic & Ingram, 2017 ). Objective aspects of wellbeing are unequally distributed by gender, age, class, and ethnicity and are strongly associated with life satisfaction (Western & Tomaszewski, 2016 ). Although there are relatively few studies of the effect of specific factors on subjective wellbeing, especially in the case of children, we attempt to do so in this study. There are many studies on the relation between subjective wellbeing and age, which show that most developed countries have U-shaped SWB curves with a minimum at the age of 40–50 (Steptoe et al., 2015 ). At the same time, the objective and subjective SES of people is connected to changes to the SWB in at least a 4-year perspective (Zhao et al., 2021 ).

In the present study, we examine the existence of similar trends for children over a short-term period. Clearly, a country’s social policies are important in the long term: children are happier if they live in favorable conditions and safe communities, attend good schools, etc. (Bradshaw, 2015 ). However, we cannot examine such policies here. Instead, we look at the impact of certain factors “here and now” rather than in the long term.

One example of the questions that were included in the survey as a component of wellbeing scale is the statement: “There are more good than bad things in my life.” Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with this claim. It can be seen from Table 9.1 that the distribution of answers for the period before school closures differs from answers about the current situation. We can see a widening pattern for opposite categories, which is also true for the SWB index as a whole.

A comparison of the level of subjective wellbeing of students before the closure of schools in the spring and at the present time shows that this indicator fell on average in most of the studied regions (Fig. 9.4 ). Significant decreases in the level of wellbeing were observed in the Kaliningrad Region (t = 3.14, p = 0.001), Leningrad Region (t = 1.76, p = 0.039) and Moscow Region (t = 1.65, p = 0.050). The latter experienced the greatest decrease. At the same time, the wellbeing of children in the Tyumen Region increased slightly over this period, although this increase was not significant (t = -1.58, p = 0.943).

Student subjective wellbeing before and after school closures

Assessment of the change in wellbeing during the pandemic for groups of students with different amount of home possessions reveals alarming results. We found that in the group of students with comparatively low level of home possessions there was a significant decrease in wellbeing during the pandemic (t = 2.42, p = 0.016). On the other hand, students from families with middle and high levels of home possessions did not experience any significant changes in subjective wellbeing. This illustrates growing inequality between students from different families in the period of school closures (Fig. 9.5 ).

Student subjective wellbeing in families with different amount of home possessions

Among all other socio-demographic characteristics, only student age was significantly related to a change in wellbeing in the pandemic period. Younger students aged 8–10 years claimed a slight increase in subjective wellbeing after school closures (t = -5.27, p = 0.000). At the same time, students from 11 to 14 years old had significantly lower results on the subjective wellbeing scale after school closures (t = 3.34, p = 0.001 and t = 2.98, p = 0.003). In addition, no significant changes in subjective wellbeing were found for students aged 15 years and older (Fig. 9.6 ).

Student subjective wellbeing for different age groups

As for communication with school, it appears that about 11% of all students lost almost all contact with their schools. Only 89% of respondents stated that they received messages from school almost every day. Other students received messages from school once a week or even less. Of all the means of communication with students, schools used emails most often (84%). In addition, 32% of students claimed that they communicated with school by video calls (Fig. 9.7 ).

Communication with school

Our study of factors contributing to student subjective wellbeing showed that school characteristics did not play a key role in the state of children. No school characteristic (school resources, student body, area) had a significant connection with the subjective wellbeing of students if individual and regional factors were included in the model. Significant individual characteristics both before and after school closures included gender, age, parents’ higher education, and home possessions (e.g., car, television, computer, air conditioner, etc.) (Fig. 9.8 ). Footnote 2 Girls had a lower level of subjective wellbeing than boys; the same was true for older students in comparison to younger. At the same time, the parents’ education and the number of home possessions had a positive relationship with the subjective wellbeing. The region in which the student lives also had an effect: the subjective wellbeing of students in the Tyumen Region was higher than in other regions both before school closures and in the winter of 2020.

Factors of student subjective wellbeing before and after school closures

Our analysis confirms the results of prior SWB studies. In particular, our findings that primary school students had higher subjective wellbeing than older students before and after school closures, while boys sustainably felt better than girls, are consistent with recent major studies of student subjective wellbeing (Lampropoulou, 2018 ).

Measurements of the level of SWB since the closure of schools show that subjective wellbeing had fallen less for students with numerous home possessions (Fig. 9.9 ). Footnote 3 Another important factor is student interaction with schools during the absence of face-to-face learning: students who received information from their school by email or through online platforms showed a more stable level of subjective wellbeing. At the same time, the older the student, the more his or her subjective wellbeing decreased over the period in question. With regards to regional differences, the greatest changes in SWB were observed in the Kaliningrad and Moscow Regions while the least changes were observed in the Tyumen Region.

The change was measured as SWB before school closure minus SWB after school closure.