- Newsletters

Why the “homework gap” is key to America’s digital divide

- Tanya Basu archive page

When the pandemic hit, parents scrambled to get enough devices to get their kids for online schooling. But even when they did, not everything went smoothly. Getting multiple people online for hours at a time in a home was one big obstacle; making sure entire communities were able to sign on was another.

Jessica Rosenworcel, the senior Democrat on the Federal Communications Commission, wasn’t surprised. For years, Rosenworcel has talked about the “homework gap,” the term she coined to describe a problem facing communities where kids can’t access the internet because infrastructure is inadequate, their families can’t afford it, or both.

People are now paying attention—not least because rumors are swirling that if Joe Biden is elected president, she could be appointed chairperson of the FCC. (Rosenworcel would not confirm these rumors, citing the Hatch Act.)

The FCC’s current broadband standard is a download speed of at least 25 megabits per second—the minimum for a single 4K Netflix stream. But in rural areas, where a Pew study estimates that one-third of Americans don’t have access to broadband, those speeds are unheard of. And while the Pew data indicates that about three-quarters of urban and suburban households have access to broadband, take that claim with a huge grain of salt: in current FCC mapping, a zip code is considered to be served with broadband if a single household has access .

In light of these problems, Rosenworcel is passionate about getting the FCC to update the E-Rate program , a federal education technology service created in 1996 that offers schools and libraries discounted internet access.

I spoke to Rosenworcel about her plans to use the program to address the homework gap. This interview has been edited and condensed for length.

How did you come up with the term “homework gap”?

When I joined the FCC, I decided that I would visit some schools that were E-Rate beneficiaries when I was traveling for work. And something struck me: I wound up in big cities and in small towns, in urban America and rural America, but I heard the very same things from teachers and administrators no matter where I went: “The E-Rate program is great. We now have these devices we can use in all of our classrooms. But when our students go home at night, not all of them have reliable internet access at home. It’s hard for our teachers to assign homework if we don’t have the confidence that every student has reliable access outside of school.”

The more that I talked to teachers, the more I heard the same stories over and over again: Kids sitting in the school parking lot with school laptops they had borrowed late into the evening, trying to peck away at homework because that was the only place they could actually get online. Or kids sitting in fast food restaurants and doing their homework with a side of fries.

I looked at the data and I found that seven in 10 teachers would assign homework that requires internet access. But FCC data consistently shows that one in three households don’t have broadband at home. I started calling where those numbers overlap the “homework gap” because I felt that this portion of the digital divide really needed a phrase or a term to describe it because it’s so important.

It’s becoming apparent that every student needs this to complete schoolwork now. And then enter the pandemic, right? We sent millions and millions of kids home. We told so many of them to go to online class, but the data suggests that as many as 17 million of them can’t make it there, so now this homework gap is becoming an education gap—and I worry it can become a long-term opportunity gap if we don’t correct it.

Why does the US have such digital inequity?

Well, we’re really a diverse country. We’re also diverse geographically, and that has wonderful qualities but it also has consequences. It takes some work to make sure everyone is connected. But we’ve done it before. We did it with electricity following the Rural Electrification Act. We did it with basic telephony. We can do it again with broadband.

Early in the pandemic I spoke to immigrant families and people who don’t have access to the internet unless they go to a public space. A lot of them were told they could get reduced-rate internet, but that was difficult in terms of documentation and being able to pay those rates. How has the FCC addressed this issue, and do you think there is a way to move forward here?

I’m one of five people at the FCC. I’m the senior Democrat. I’m not in the majority. I can be noisy and I can be relentless, but I don’t always convince my colleagues.

I am convinced that we can update the E-Rate program using existing law and support schools—loaning out Wi-Fi hot spots, for instance. I think we can do that today with the E-Rate program.

And shame on us for not doing it. Because we’re not doing it, what you see are pictures like the one that went viral of two girls sitting outside of a Taco Bell in Salinas, California, not for lunch—they were there because they were using the free Wi-Fi signal. And what you now see is Wi-Fi in parking lots across this country in places that have been closed down because there’s this cruel virus and students are sitting in hot cars attending class and doing their schoolwork. And then other students are entirely locked out of the virtual classrooms, because they just don’t have a way to get online.

So shame on the FCC for not making it a priority to update E-Rate to address this crisis, because it’s within our power to help right now. I am saddened that my agency keeps looking the other way.

What is the demographic of kids most affected by the homework gap?

It has a disproportionate impact on communities of color. It’s disproportionately harmful to rural America and disproportionately harms low-income households. What’s most cruel to me about this is that we have a program we could update and help fix this, but we keep looking the other way. So many students are unable to attend class in person right now. And if they can’t make it into online classrooms and they’re out of schools for months, it’s going to have a long-term impact on their education.

Is implementing the E-Rate program even feasible right now?

One of the beauties of the E-Rate program is that it’s set up in a way so that more support goes to schools with greater numbers of students on free or reduced-price lunch programs. In other words, it’s almost a perfect map of where the demand is most likely. We could use that to really figure out how to get devices or wireless hot spots out to students—things that could make a meaningful difference. I mean, it wasn’t that long ago that every student didn’t always get textbooks or a grammar workbook. We have to start recognizing that for students who don’t have internet access at home, having the school loan out a wireless hot spot is the difference between keeping up in class and falling behind. We can do something to fix this.

How quickly can we expand the E-Rate program?

The truth is that we should have started this at the start of the pandemic. Seven months in is too late, but today is better than tomorrow. We should be doing this immediately. And it’s not totally irrational. Years ago, the FCC years ago made some adjustments following Hurricane Katrina to a different program that helps low-income households get internet service, to make sure that everyone who got displaced was able to get phone service started again with a wireless line.

We have a history of looking at a disaster, trying to assess what’s necessary to keep people connected, and updating our programs in response. We should be doing this right now with E-Rate for the homework gap.

I read that you’re a mom.

I’m curious what you thought about homeschooling and being online during this time.

Keep Reading

Most popular.

People are using Google study software to make AI podcasts—and they’re weird and amazing

NotebookLM is a surprise hit. Here are some of the ways people are using it.

- Melissa Heikkilä archive page

2024 Climate Tech Companies to Watch

- Amy Nordrum archive page

How refrigeration ruined fresh food

Nearly everything on the American plate is processed, shipped, stored, and sold under refrigeration. In her new book, Nicola Twilley reflects on what it means to be entirely dependent on artificial cooling.

- Allison Arieff archive page

Geoffrey Hinton, AI pioneer and figurehead of doomerism, wins Nobel Prize

The award recognizes foundational contributions to deep learning, a technology that Hinton has since come to fear.

- Will Douglas Heaven archive page

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

How is the digital divide is affecting U.S. students’ homework?

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Image: Erin Clark/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

.chakra .wef-spn4bz{transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--chakra-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;text-decoration:none;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:hover,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-hover]{text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:focus-visible,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-focus-visible]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);} Katherine Schaeffer

- Research carried out by Pew Research Center highlights how a lack of internet connectivity and digital skills negatively affected K-12 students' ability to complete school work at home.

- Research shows these problems were faced by families of different incomes, race and location.

- One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often.

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time – an experience often called the “ homework gap ” – may continue to feel the effects this school year.

Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found about the students most likely to be affected by the homework gap and their experiences learning from home.

Around nine-in-ten U.S. parents with K-12 children at home (93%) said their children have had some online instruction since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, and 30% of these parents said it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet as an educational tool, according to an April 2021 Pew Research Center survey .

Gaps existed for certain groups of parents. For example, parents with lower and middle incomes (36% and 29%, respectively) were more likely to report that this was very or somewhat difficult, compared with just 18% of parents with higher incomes.

This challenge was also prevalent for parents in certain types of communities – 39% of rural residents and 33% of urban residents said they have had at least some difficulty, compared with 23% of suburban residents.

Around a third of parents with children whose schools were closed during the pandemic (34%) said that their child encountered at least one technology-related obstacle to completing their schoolwork during that time. In the April 2021 survey, the Center asked parents of K-12 children whose schools had closed at some point about whether their children had faced three technology-related obstacles. Around a quarter of parents (27%) said their children had to do schoolwork on a cellphone, 16% said their child was unable to complete schoolwork because of a lack of computer access at home, and another 14% said their child had to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

Parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed amid COVID-19 were more likely to say their children faced technology-related obstacles while learning from home. Nearly half of these parents (46%) said their child faced at least one of the three obstacles to learning asked about in the survey, compared with 31% of parents with midrange incomes and 18% of parents with higher incomes.

Of the three obstacles asked about in the survey, parents with lower incomes were most likely to say that their child had to do their schoolwork on a cellphone (37%). About a quarter said their child was unable to complete their schoolwork because they did not have computer access at home (25%), or that they had to use public Wi-Fi because they did not have a reliable internet connection at home (23%).

A Center survey conducted in April 2020 found that, at that time, 59% of parents with lower incomes who had children engaged in remote learning said their children would likely face at least one of the obstacles asked about in the 2021 survey.

A year into the outbreak, an increasing share of U.S. adults said that K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork at home during the pandemic. About half of all adults (49%) said this in the spring 2021 survey, up 12 percentage points from a year earlier. An additional 37% of adults said that schools should provide these resources only to students whose families cannot afford them, and just 13% said schools do not have this responsibility.

Even before the pandemic, Black teens and those living in lower-income households were more likely than other groups to report trouble completing homework assignments because they did not have reliable technology access. Nearly one-in-five teens ages 13 to 17 (17%) said they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, a 2018 Center survey of U.S. teens found.

One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often. Just 4% of White teens and 6% of Hispanic teens said this often happened to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in the survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

A wide gap also existed by income level: 24% of teens whose annual family income was less than $30,000 said the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibited them from finishing their homework, but that share dropped to 9% among teens who lived in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Sdg 04: quality education, related topics:.

.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-ugz4zj{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);color:var(--chakra-colors-yellow);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-ugz4zj{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} SDG 04: Quality Education is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-19044xk{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);color:var(--chakra-colors-uplinkBlue);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-19044xk{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

The agenda .chakra .wef-dog8kz{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineheights-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontweights-normal);} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:flex;align-items:center;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education and Skills .chakra .wef-17xejub{flex:1;justify-self:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-2sx2oi{display:inline-flex;vertical-align:middle;padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-1);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-1);text-transform:uppercase;font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smallest);border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontWeights-bold);background:none;box-shadow:var(--badge-shadow);align-items:center;line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-short);letter-spacing:1.25px;padding:var(--chakra-space-0);white-space:normal;color:var(--chakra-colors-greyLight);box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width: 37.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smaller);}}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-base);}} See all

Skills for the future: 4 ways to help workers transition to the digital economy

Simon Torkington

October 21, 2024

From herding to coding: the Mongolian NGO bridging the digital divide

World University Rankings 2025: Elite universities go increasingly global

What to know about generative AI: insights from the World Economic Forum

The ‘Homework Gap’ Persists. Tech Equity Is One Big Reason Why

- Share article

Nearly a third of U.S. teenagers report facing at least one academic challenge related to lack of access to technology at home, the so-called “homework gap,” according to new survey from the Pew Research Center.

And that is the case even though nearly all K-12 students were back to in-person learning this school year, according to the Pew Research Center survey , conducted April 14 to May 4. The survey examines teens’ and parents’ views on virtual learning and the pandemic’s impact on academic achievement.

“More than two years after the COVID-19 outbreak forced school officials to shift classes and assignments online, teens continue to navigate the pandemic’s impact on their education and relationships, even while they experience glimpses of normalcy as they return to the classroom,” the report’s authors noted.

The survey found that 22 percent of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 said they often or sometimes have to do their homework on a cellphone, 12 percent said they “at least sometimes” are not able to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, and 6 percent said they have to use public Wi-Fi to do their homework “at least sometimes” because they don’t have an internet connection at home.

The “ homework gap ” is a term used to describe the difficulty students have in getting online at home to complete school assignments. It disproportionately impacts students in low-income households, students of color, and students in rural areas.

The Pew Research Center’s report found the homework gap remains a persistent problem. About 24 percent of teens who live in a household making less than $30,000 a year said they “at least sometimes” are not able to complete their homework because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, compared with 14 percent of those in a household making $30,000 to $74,999, and 8 percent of those in a household making $75,000 or more, the report found.

Teens whose parents report an annual income of less than $30,000 are also more likely to say they often or sometimes have to do homework on a cellphone or use public Wi-Fi for homework, compared with those living in higher-earning households, according to the survey.

Sixteen percent of Hispanic teens reported they “at least sometimes” aren’t able to complete homework because they lack reliable computer or internet access, compared with 7 percent of Black teens and 10 percent of white teens. Hispanic teens are also four times more likely than white teens to say the same about having to do their homework on a cellphone or using public Wi-Fi for homework, the report found.

When it comes to access to a computer, 20 percent of teens living in a household with an annual income of less than $30,000 reported not having access to a desktop or laptop at home.

Teens prefer learning in person

Eighty percent of teens said they attended school completely in person over the month prior to when the survey was administered, according to the report. Eleven percent said they attended school through a mix of online and in-person instruction, and 8 percent said they attended school completely online.

A majority of teens prefer in-person over virtual or hybrid learning. Sixty-five percent said they would prefer school to be completely in person after the COVID-19 outbreak is over, while 9 percent said they would prefer a completely online learning environment. Eighteen percent said they would prefer a mix of online and in-person instruction, according to the report.

While a majority of teens prefer in-person learning, there are some differences that emerge by race and ethnicity and household income. Seventy percent of white teens and 64 percent of Hispanic teens said they would prefer completely in-person learning after the COVID-19 outbreak, but that share drops to 51 percent among Black teens, according to the report.

Seventy-one percent of teens living in households earning $75,000 or more a year said they prefer for school to be completely in person after the pandemic is over. That share drops to 60 percent or less among those whose annual family income is less than $75,000.

Some teens worry about falling behind

When asked about COVID-19’s effect on their schooling, a majority of teens expressed little to no concern about falling behind in school due to disruptions caused by the outbreak. But Hispanic teens and teens from families with lower incomes were more likely to say they are “extremely” or “very” worried about falling behind in school due to COVID-19 disruptions.

Overall, 16 percent of teens said they are “extremely” or “very” worried they may have fallen behind in school because of COVID-19-related disturbances. Twenty-eight percent of Hispanic teens said they are “extremely” or “very” worried that they may have fallen behind, compared with 19 percent of Black teens, and 11 percent of white teens. And 46 percent of teens from households making less than $75,000 annually reported concerns about falling behind in school, compared with 13 percent of teens from households making more than $75,000 annually.

Sign Up for EdWeek Tech Leader

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

- Media Choice

- Digital Equity

- Digital Literacy and Citizenship

- Tech Accountability

- Healthy Childhood

- 20 Years of Impact

London School of Economics Evaluation of Our Digital Citizenship Curriculum

New AI Ratings and Reviews

- Our Current Research

- Past Research

- Archived Datasets

The Dawn of the AI Era: Teens, Parents, and the Adoption of Generative AI at Home and School

Unpacking Grind Culture in American Teens: Pressures, Burnout and the Role of Social Media

- Press Releases

- Our Experts

- Our Perspectives

- Public Filings and Letters

Common Sense Media Announces Framework for First-of-Its-Kind AI Ratings System

- How We Work

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Meet Our Team

- Board of Directors

- Board of Advisors

- Our Partners

- How We Rate and Review Media

- How We Rate and Review for Learning

- Our Offices

- Join as a Parent

- Join as an Educator

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Request a Speaker

- We're Hiring

The Homework Gap: Teacher Perspectives on Closing the Digital Divide

The homework gap refers to the divide between students who have home broadband access and those who do not. It is also an indicator of whether or not a student will be able to complete their homework and succeed in school alongside their internet-connected peers. To better understand how this gap persists today, Common Sense conducted a nationwide survey with teachers about how often they assign homework that requires digital tools, and how assignments vary in schools with higher- and lower-income students.

This report is a companion piece to the 2019 Common Sense Census: Inside the 21st Century Classroom .

See the infographic Download the full report

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Nearly one-in-five teens can’t always finish their homework because of the digital divide

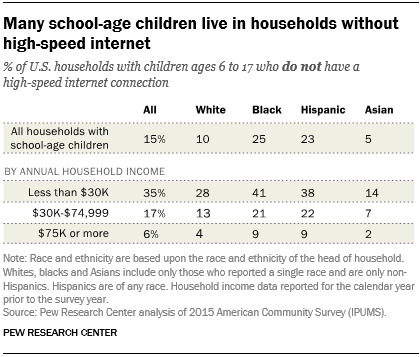

Some 15% of U.S. households with school-age children do not have a high-speed internet connection at home, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of 2015 U.S. Census Bureau data. New survey findings from the Center also show that some teens are more likely to face digital hurdles when trying to complete their homework.

School-age children in lower-income households are especially likely to lack broadband access. Roughly one-third of households with children ages 6 to 17 and whose annual income falls below $30,000 a year do not have a high-speed internet connection at home, compared with just 6% of such households earning $75,000 or more a year. These broadband disparities are particularly pronounced for black and Hispanic households with school-age children – especially those with low household incomes. (The overall share of households with school-age children lacking a high-speed internet connection in 2015 is comparable to what the Center found in an analysis of 2013 Census data.)

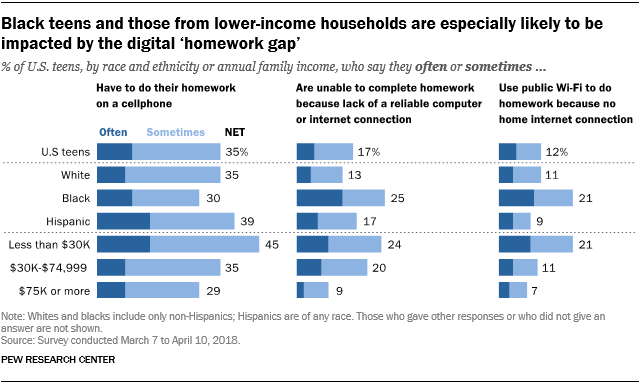

This aspect of the digital divide – often referred to as the “homework gap” – can be an academic burden for teens who lack access to digital technologies at home. Black teens, as well as those from lower-income households, are especially likely to face these school-related challenges as a result, according to the new Center survey of 743 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted March 7–April 10, 2018.

At its most extreme, the homework gap can mean that teens have trouble even finishing their homework. Overall, 17% of teens say they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection.

This is even more common among black teens. One-quarter of black teens say they are at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who say this happens to them often. Just 4% of white teens and 6% of Hispanic teens say this often happens to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in this survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

Teens also differ by income level when it comes to completing assignments: 24% of teens whose annual family income is less than $30,000 say the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibits them from finishing their homework, but that share drops to 9% among teens who live in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

Other times, teens who lack reliable internet service at home say they seek out other locations to complete their schoolwork: 12% of teens say they at least sometimes use public Wi-Fi to complete assignments because they do not have an internet connection at home. Again, this problem is more prevalent for black or less affluent teens. Roughly one-in-five black teens (21%) report having to at least sometimes use public Wi-Fi for this reason, including 10% who say they often do so. And teens whose family income is below $30,000 a year are far more likely than those whose annual household income is $30,000 or higher to say that they do this (21% vs. 9%).

Lastly, 35% of teens say they often or sometimes have to do their homework on their cellphone. Although it is not uncommon for young people in all circumstances to complete assignments in this way, it is especially prevalent among lower-income teens. Indeed, 45% of teens who live in households earning less than $30,000 a year say they at least sometimes rely on their cellphone to finish their homework.

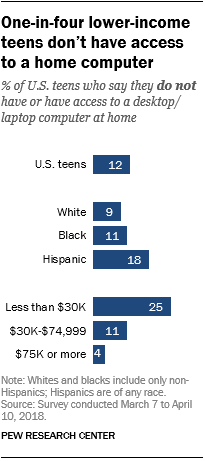

These findings reflect a broader discussion about the digital divide’s impact on America’s youth. Numerous policymakers and advocates have expressed concern that students with less access to certain technologies may fall behind their more digitally connected peers. There is some evidence that teens who have access to a home computer are more likely to graduate from high school when compared with those who don’t.

The Center’s survey of teens does show stark differences in teens’ computer access based on their household income. A quarter of teens whose family income is less than $30,000 a year do not have access to a home computer, compared with 4% of those whose annual family income is $75,000 or more.

Note: See full topline results and methodology here (PDF).

- Age & Generations

- Digital Divide

- Economic Inequality

- Education & Learning Online

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

Monica Anderson is a director of research at Pew Research Center .

Andrew Perrin is a former research analyst focusing on internet and technology at Pew Research Center .

5 facts about student loans

U.s. adults under 30 have different foreign policy priorities than older adults, across asia, respect for elders is seen as necessary to be ‘truly’ buddhist, teens and video games today, as biden and trump seek reelection, who are the oldest – and youngest – current world leaders, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- About Benton

- Organization Timeline

- 40th Anniversary

- Collaborations

- Latest News

- Today's Newsletter

- Weekly Digest

- Digital Beat

- Digital Divide Diaries

- Illinois Broadband Connections

- ACP Enrollment Performance Tool

- Visions of Digital Equity

- Opportunity Fund Fellowship

- Broadband Breakthrough

- Pathways to Digital Equity

The Homework Gap: Teacher Perspectives on Closing the Digital Divide

In 2018, Common Sense conducted a national survey and focus groups to understand the challenges and promise of technology use in the classroom for learning. Teachers across the US were asked about the use of educational technology with students in their classrooms, and issues of access emerged:

- Approximately one out of 10 teachers (12%) reported that the majority of their students (61% to 100%) do not have home access to the internet or a computer. Approximately four out of 10 teachers said that many of their students do not have adequate home access to the internet or a computer to do schoolwork at home.

- Teachers in Title I schools or in schools with more than three-quarters of students being students of color are more likely to say that over 60% of their students do not have home access to the internet or a computer.

- As grade levels increase, teachers are more likely to assign homework that requires access to digital devices and/or broadband internet outside of schools.

- Teachers who assign homework that requires access to digital devices and/or broadband internet outside of school are more likely to teach in affluent, non-Title I schools than in Title I schools.

- Teachers in schools with student populations of predominantly students of color are more likely to say that it would limit their students’ learning if their students did not have adequate access to broadband internet or a computing device at home to do homework (34%), as compared to teachers in schools with mixed populations or teachers in schools with predominantly white students (26% and 27%, respectively).

- Log in or register to post comments

Related Headlines

- NetChoice, the Lobbying Group Helping to Broaden the First Amendment’s Reach

- Social media warning labels come to Washington

- What the FTC Learned About Social Media

- Sens Katie Britt, John Fetterman Introduce Bill to Create Warning Label Requirement for Social Media Platforms

- Governor Newsom signs legislation to limit the use of smartphones during school hours

© 1994-2024 Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. All Rights Reserved.

Our expert, award-winning staff selects the products we cover and rigorously researches and tests our top picks. If you buy through our links, we may get a commission. How we test ISPs

- Home Internet

How the homework gap may actually be the key to solving our digital divide

Schools across the country during the past year of distance learning have had access to important data on who has access to broadband and who doesn't.

After schools were ordered to shut down last year due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Freeman School District in Rockford, Washington, surveyed families and put together a map to determine where broadband was available and where it wasn't.

When schools shut down in March 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Freeman School District in Rockford, Washington , like districts across the country, scrambled to put in place a remote learning plan. The good news was that it had already begun rolling out a program to get every student in its 900-person district a device to connect to the internet. This meant the school district had gear for each student to access learning tools remotely.

The bigger problem was that pockets of students throughout the mostly rural school district, 15 miles south of Spokane, lacked access to broadband service or even cellular LTE service.

The trick for Freeman School District was figuring out where those dead spots were and how to get students connected, said superintendent Randy Russell. For students who could get cellular service but who lacked internet service at home, the district provided mobile hotspots. But for those for whom access was simply not available at their homes, students could access the school's Wi-Fi network from the school's parking lot or the parking lots of the library or local Starbucks. For students who couldn't get access to any kind of service, the school provided paper packets.

Locating local internet providers

"We had to figure out a game plan for every single family," Russell said.

Almost immediately, the district began surveying families and piecing together a detailed map of where service existed and where it was lacking. By the time school started in the fall, the district was able to ensure that every student had access to the internet. Some students were still using Wi-Fi hotspots, others were connecting to the community or school-based Wi-Fi from parking lots. And many families in the district formed small cohorts or pods of students in their homes and they organized themselves to ensure kids who lacked access had somewhere to go to access online learning.

"The map really helped us troubleshoot," Russell said. "We could say, 'Oh yeah the Russells over there on Elder Road have no internet. Cougar Wireless only goes this far over there or Verizon goes this far.'"

He said with that knowledge the district was able to provide an extra level of support to students who were disconnected.

But beyond supporting students, that information, being collected by schools across the country, could prove useful when addressing the problem of the digital divide. It's a significant gap: The Federal Communications estimates that 14.5 million people still lack access to broadband internet, while BroadbandNow , which tracks internet service and pricing, puts the figure of unconnected Americans at around 42 million. While President Joe Biden has an ambitious $100 billion plan to build out internet infrastructure, one of the problems remains identifying where the gaps actually are. The work to close the so-called homework gap , exacerbated when the coronavirus pandemic shut down schools and forced 50 million students to suddenly adopt remote learning, could also provide the federal and state governments a roadmap toward fixing the broader digital divide problem.

Related stories

- The digital divide has left millions of school kids behind

- Millions of Americans can't get broadband because of a faulty FCC map. There's a fix

- States couldn't afford to wait for the FCC's broadband maps to improve. So they didn't

Russell said his district and districts across the state were able to feed the information they gathered on online access and attendance to state officials. Those details were critical as legislators tried to figure out how to help schools during the pandemic and where to direct federal funds from the CARES Act.

"The CARES Act dollars were super beneficial to our district," Russell said. "We weren't only able to get PPE, cleaning supplies and masks for our staff, but it also helped us with some of the technology like providing some of the Wi-Fi hotspots kids needed."

Despite federal and state efforts to close the homework gap -- a term used to describe students who lack broadband or equipment like tablets or laptops -- 12 million students are still falling further behind, according to a report from Common Sense and the Boston Consulting Group.

The digital divide

The homework gap is a subset of a much larger digital divide that exists between people with and people without access to high-speed internet. For millions of Americans, the digital divide exists because they live in a rural part of the country where broadband infrastructure simply isn't available. For other families in rural and suburban markets, broadband service may be available but unaffordable.

It's an issue that has dogged policy makers for years. Biden's $100 billion plan to bring broadband to every American comes on top of billions of dollars in funding the federal government has already promised to connect unserved communities. Yet a fundamental problem persists: The maps the federal government uses to determine where it sends money to bridge the digital divide are grossly inaccurate .

The problems with the current system for collecting the data stem from the fact that the data isn't granular enough, so it may say an area is covered with broadband when, in fact, it could be only one address with access.

Republicans and Democrats on the FCC and in Congress have long agreed that the data for mapping needs to be improved to get an accurate picture of where broadband exists and where it doesn't. And they've pledged to do something about it. But getting that data has proven difficult and time-consuming. Officials at the FCC don't expect more accurate maps to be ready until next year.

Silver lining in the pandemic

This is where policy makers could find help from the yearlong experiment on distance learning that schools across the country were forced to undergo. If school districts and others working at the local level were collecting and mapping areas to assess basic broadband and computing needs, it could provide a wealth of knowledge that could be fed into databases mapping the digital divide.

"Schools are proving to be very valuable partners in figuring out the needs of the community -- including where broadband does and does not exist in their communities," said Amina Fazlullah, director of equity policy for Common Sense, a nonprofit focused on education.

Common Sense partnered with the Boston Consulting Group, EducationSuperHighway and Southern Education Foundation, to publish three in-depth reports over the past year looking at the magnitude of the divide and potential solutions.

Fazlullah added that schools are uniquely positioned to be able to collect data about students' broadband access and to marry that data with other information about students. This includes not just whether service exists, but also service quality and the types of applications being used over that connection. Schools also already collect demographic and socioeconomic data, which can be useful in tracking and analyzing the root causes of why students may not have service.

Together, this gives school districts the ability to track the digital needs of students over time in order to give state and federal policy holders a snapshot of the need, as well as the cost and service quality of the broadband access that's available in the local community.

"If schools are able to work with their states to highlight these gaps, they could be an amazing resource," Fazlullah said.

Still, Fazlullah acknowledges that the data collection effort has been haphazard at best. There hasn't been a uniform way in which schools collect or report this data. And given the local control and differences among states, it's unlikely that a centralized or cohesive system can be put in place quickly.

Texas: Go big or go home

In Texas, there's Operation Connectivity , a partnership between Gov. Greg Abbott, the Dallas Independent School District and the Texas Education Agency, created to connect all of Texas's 5.5 million public school students with a device and reliable internet connection. The organization came together last spring, after the pandemic hit, to figure out how to use federal CARES Act money to coordinate the bulk purchase of 1 million computing devices and 500,000 hotspots for students throughout Texas during the pandemic.

One of the first things the organization did was to assess the situation. They needed to know where devices and services were most needed and where internet was lacking, said Gaby Rowe, the project lead for Operation Connectivity.

"Data was definitely our biggest barrier when we first started this project," she said. "We couldn't fulfill our mandate from the governor if we didn't know where the resources were needed."

But there was no detailed map or data set available to get the information they needed, so Rowe said her group joined forces with Connected Nation Texas , a statewide initiative that had already been funded to create a broadband map to highlight gaps in coverage. Connected Nation Texas was already working with service providers to collect data about where they offered connectivity. Operation Connectivity was able to gather information from the Texas Education Agency and school districts along with service provider data from Connected Nation Texas to get a more accurate picture of what students needed and where.

Through this effort, Operation Connectivity was able to identify roughly 2 million students, or more than a third of the total, who had access to broadband but weren't signed up for a service, either because they could not afford it or there was some other barrier, such as privacy concerns. The group also determined that about 350,000 students had no access to broadband at all. There were about 700,000 students who had access to only one broadband provider, many of whom were likely underserved and with speeds insufficient to support most distance learning.

Coordinated efforts

The lack of good data that is both precise and accurate is a major problem for solving the digital divide, said Nicol Turner Lee, director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution , who has studied the digital divide for more than two decades.

"We don't know how many people are using what type of technology," she said. "So we do need to do a better job of ensuring that we have this data first, because without it, our efforts to accelerate broadband deployment just won't work."

Turner Lee said data collected from school districts and local officials could help build a better picture of what's needed where.

"It took a crisis for us to recognize the need for this local and national data," she said. "Before the pandemic, many school officials had no clue who their local wireless or broadband service providers were."

She said that some still don't have this information. But she added it's important that schools recognize that gathering this data and helping families connect to the internet should be part of their outreach in this new age of distance learning.

"This crisis has really repositioned schools as a partner in the community," she said. She has been pushing states to require that districts collect this data by asking a few simple questions, such as, 'Do you have broadband access at home?'"

But she added that the real heavy lifting to solve the digital divide must still come from the federal government.

"It's become very apparent that broadband is a critical infrastructure asset like our water, electricity and energy system," she said. "We need a New Deal-era type of approach with a coordinated federal response to address infrastructure deployment, adoption and use, so we have workforce opportunities in building this infrastructure. And we have to resolve that no child should ever be left offline again."

Home Internet Guides

- Best Internet Providers in Los Angeles

- Best Internet Providers in New York City

- Best Internet Providers in Chicago

- Best Internet Providers in San Francisco

- Best Internet Providers in Seattle

- Best Internet Providers in Houston

- Best Internet Providers in San Diego

- Best Internet Providers in Denver

- Best Internet Providers in Charlotte NC

- Google Fiber Internet Review

- Xfinity vs Verizon Fios

- Verizon 5G vs. T-Mobile Home Internet

- Verizon Internet Review

- Xfinity Internet Review

- Best Rural Internet

- Best Cheap Internet and TV Bundles

- Best Speed Tests

- AT&T Home Internet Review

- Best Satellite Internet

- Verizon 5G Home Internet Review

- T-Mobile Home Internet Review

- Best Internet Providers

- Frontier Internet Review

- Best Mesh Wi-Fi Routers

- Eero 6 Plus Review

- TP-Link Review

- Nest Wi-Fi vs. Google Wi-Fi

- Best Wi-Fi Extender

- Best Wi-Fi 6 Routers

- Best Wi-Fi Routers

- What is 5G Home Internet?

- Home Internet Cheat Sheet

- Your ISP May Be Throttling Your Internet Speed

- How to Switch ISPs

- Internet Connection Types

- Internet for Apartments

- Top 10 Tips for Wi-Fi Security

- How to Save Money on Your Monthly Internet Bill

- How Much Internet Speed Do You Need?

- Resources & Publications

- Newsletters

Homework Gap Hits Communities of Color Harder

- Aug 4, 2020

- Katie Kienbaum

Millions of students do not have access to adequate connectivity, but Black, Latinx, and Native children are disproportionately impacted by the “homework gap” — a term that describes the divide between students with access to home broadband and Internet-enabled devices and those without, as well as the challenges that unconnected students face. One study found that children in one out of every three Black, Latinx, and Native American households did not have broadband access at home.

These disparities are even more pressing during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, which has turned the homework gap into a chasm. Schools across the country cancelled in-person instruction at the end of the last school year, and many continue to make plans for remote learning in the fall. As the nonprofit Common Sense pointed out in a recent report , “The ‘homework gap’ is no longer just about homework; it’s about access to education.”

School districts, cities, and states across the country are distributing hotspots, deploying wireless LTE networks, and paying for students’ Internet plans, among other efforts to quickly address the homework gap. However, many of these solutions are stopgap answers to a systemic problem.

UnidosUS President and CEO Janet Marguía said in a press release :

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the impact of the digital divide on the academic progress of our students, particularly from low-income, Black, Latino, and American Indian households. Roadblocks, including internet connectivity and access to a computer or tablet, have denied students of color the opportunity to meaningfully engage in online learning, resulting in learning loss and widening achievement gaps . . . We cannot continue to overlook the disproportionate impact of this divide.

Mind the Gap

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel is frequently credited with coining the term “homework gap” to describe the divide between connected and unconnected students. During her time in the FCC, she has called it the “cruelest part of the new digital divide” and has advocated for federal measures to help close the homework gap.

Nearly 17 million children in the U.S. don’t have wired broadband access at home, and more than 7 million children don’t have access to an appropriate device, according to a recent report sponsored by the Alliance for Excellent Education (All4Ed) in partnership with the National Urban League, UnidosUS, and the National Indian Education Association. A similar analysis from Common Sense found that 15-16 million public K-12 students, or about 30%, lack adequate home Internet access and/or devices, with approximately 9 million students lacking both.

Those two reports used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) to support their findings, but other sources also suggest that the digital divide affects a significant portion of students. A Pew Research Center survey from 2018 found that 17% of teens often or sometimes cannot finish homework because of inadequate connectivity or unreliable access to devices. These figures may underestimate the current extent of the homework gap because they do not capture the effects of the pandemic, which has created economic hardship for many families.

Though rural states, like Mississippi and Arkansas, have the highest proportions of unconnected students, states with greater urban populations, such as California and Texas, have larger amounts of students without home Internet access. The Common Sense report found that half of Mississippi public school students, about 234,000 students, lack adequate home Internet, while 34% of Texas public school students, or about 1.8 million students, lack home Internet. For more state-specific statistics, view All4Ed’s interactive map .

It’s referred to as the homework gap, but not having reliable broadband access at home affects students in many ways beyond homework completion. According to a study conducted by the Quello Center at Michigan State University and Merit Network, which looked at the homework gap in 15 rural school districts in Michigan, students without home Internet access also had lower grades and test scores, demonstrated less digital skills competency, and were less likely to plan to attend post-secondary schooling, even after accounting for socioeconomic differences. “Lack of fast Internet access or cell phone only access is associated with disadvantages that likely have lifelong consequences,” the study authors explained.

Black, Latinx, Native Students More Unconnected

The homework gap is greater in low-income communities but also in communities of color. Students from Black, Latinx, and Native American households are more likely to lack access to home connectivity and Internet-enabled access than their white and Asian peers.

All4Ed’s analysis of the 2018 ACS data found that children in 31% of Black and Latinx families and in 34% of Native American families did not have high-speed Internet access at home, compared to children in only 12% of Asian families and 21% of white families. The report also identified gaps in student access to devices among households of different races. Using the same data source, Common Sense likewise found that public school students who are Black, Latinx, or Native American are more likely to lack adequate broadband access than those who are white, reporting that 30-40% of the most unconnected students — those without home Internet access and without an appropriate device — were Black, Latinx, or Native American.

Similarly, the Pew Research Center 2018 survey on student broadband access found that Black and Latinx teens were more likely than white teens to report that they are often or sometimes unable to finish homework assignments because of a lack of a computer or Internet connection. It also found that more Latinx respondents relied on a cell phones to complete homework and that more Black respondents said they frequently used public Wi-Fi connections.

In its study, the Quello Center did not find a statistically significant difference between white students and students of color, reporting that 8.5% of minority students surveyed lacked home broadband compared to 6.9% of white students. But other national data sources in addition to the ACS, including the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s Internet Use Survey and Pew Research Center’s broadband surveys , have found that Black, Latinx, and Native households/adults are less likely to have broadband at home than white and Asian households/adults at statistically significant levels, suggesting that race does impact connectivity.

Unaffordably high costs are one of the main reasons why people do not subscribe to home Internet access, and lower average incomes among Black, Latinx, and Native households could account for some of the broadband disparities. Many providers have low-cost programs available for eligible families, but people may not be aware of their options or may receive inconclusive information from customer service representatives.

However, a 2016 Free Press report found gaps in home broadband availability and adoption among households of different races even after accounting for other household features, such as income. Similarly, analysis from think tank Third Way showed that broadband availability is lower in counties with majority Black and Native populations compared to majority white counties. Various factors, including housing segregation, credit check requirements, and other systems that perpetuate racial inequality, could possibly explain the remaining disparities.

These ingrained injustices means that policymakers must make big changes if they want to close the homework gap, the All4Ed report explains:

America’s racial inequities stem from 400 years of systemic racism and federally sanctioned discriminatory policies . . . Public policy must not be subtle nor incremental in addressing the issues that American school-age children face. We need bold and highly focused solutions that dismantle the systems that keep our children from succeeding.

Closing the Divide

Many advocates believe that closing the homework gap, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, is a role that governments must take on. “It is unlikely that market forces alone will close the gap,” wrote the Quello Center in their report, which suggested that a cost-benefit analysis of public investment in student connectivity would justify the expense. All4Ed and Common Sense also argued for federal investment in response to the pandemic, pegging the national cost of temporarily providing home broadband access and Internet-enabled devices to unconnected students at $6-$11 million.

At the local level, states and cities are working to connect students who are impacted by the homework gap in the short term. Some governments and school districts, such as the State of Connecticut and Portland Public Schools , are covering the costs of home Internet connections and wireless hotspots for households with children, often using federal CARES Act funds. Others, like the State of Maryland and San Antonio, Texas , have plans to deploy wireless LTE networks to provide connectivity to students. Unfortunately, many of these programs are temporary and do little to address the underlying reasons why tens of millions of Americans — especially Black, Latinx, and Native Americans — are stuck with high costs and no choice of Internet provider.

On the other hand, cities with municipal broadband networks have been able to make longer term commitments to connecting their students. Even before the pandemic, Cedar Falls, Iowa, and Longmont, Colorado, had developed low-cost broadband plans for families with students. And Chattanooga’s municipal network, EPB Fiber, recently announced a partnership with the local school district that would provide free home Internet access to all students that qualify for free and reduced lunch.

The pandemic has made it clear that Internet access is no longer a luxury for today’s students. Now it’s up to federal, state, and local governments to figure out how to close the homework gap and connect our students of color.

Photo by adamkaz via iStock .

The article was originally published on ILSR’s MuniNetworks.org . Read the original here .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Educators have been talking about the "digital divide" for two decades, and while some progress has been made in closing the gap, inequities persist in communities across the country.Major efforts have been undertaken to improve access to new technologies in lower-income school districts, but as more teachers turn to digital learning, Keith Krueger, CEO of the Consortium for School Networking ...

Why the "homework gap" is key to America's digital divide. When the pandemic hit, parents scrambled to get enough devices to get their kids for online schooling. But even when they did, not ...

th:Closing the homework gap is key to achieving equity in schools. State and federal. olicymakers mus. can succeed. It starts with:Teacher perspectiv. access outside of schoolTitle I schools42%Non-Title I schools31%Students of color are losing out on critical learning opportunities because teacher.

America's K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time - an experience often called the " homework gap " - may continue to feel the effects this school ...

The " homework gap " is a term used to describe the difficulty students have in getting online at home to complete school assignments. It disproportionately impacts students in low-income ...

Published: December 2, 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic shone a spotlight on a specific aspect of the digital divide known as the homework gap—the inability to do schoolwork at home due to lack of internet access. A disproportionate share of the affected students are Black, Latino/a/x , from low-income households, or live in rural areas.

America's K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time - an experience often called the "homework gap" - may continue to feel the effects this school year. Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found ...

To better understand how this gap persists today, Common Sense conducted a nationwide survey with teachers about how often they assign homework that requires digital tools, and how assignments vary in schools with higher- and lower-income students. This report is a companion piece to the 2019 Common Sense Census: Inside the 21st Century Classroom.

the homework gap, this critical lack of access exacerbates other opportunity gaps. The homework gap hits students of color particularly hard- one out of three Black, Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Native households lacks home internet access. More than 8 million households with children do not have high-speed home internet service.

Bridging the Homework Gap. A small urban district in southwestern Ohio worked to eliminate the homework gap during remote learning. Their success could serve as a model for schools across the country that collectively serve the 16.9 million children without high-speed internet. Photo credit: OFOTO/STOCK.ADOBE.COM.

Doing so would modernize the Lifeline program - and also help address the Homework Gap. The Homework Gap is the cruelest part of the digital divide. But it is within our power to bridge it, help kids get their schoolwork done and expand Internet access. We should go for it. JESSICA ROSEN WORCEL ISA MEMBER OF THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION.

This aspect of the digital divide - often referred to as the "homework gap" - can be an academic burden for teens who lack access to digital technologies at home. Black teens, as well as those from lower-income households, are especially likely to face these school-related challenges as a result, according to the new Center survey of ...

The COVID-19 pandemic shone a spotlight on a specific aspect of the digital divide known as the homework gap—the inability to do schoolwork at home due to lack of internet access. A disproportionate share of the affected students are Black, Latino/a/x , from low-income households, or live in rural areas. The American Rescue Plan provided more ...

In 2018, Common Sense conducted a national survey and focus groups to understand the challenges and promise of technology use in the classroom for learning. Teachers across the US were asked about the use of educational technology with students in their classrooms, and issues of access emerged: Approximately one out of 10 teachers (12%) reported that the majority of their students (61% to 100% ...

The homework gap is a subset of a much larger digital divide that exists between people with and people without access to high-speed internet. For millions of Americans, the digital divide exists ...

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel is frequently credited with coining the term "homework gap" to describe the divide between connected and unconnected students. During her time in the FCC, she has called it the "cruelest part of the new digital divide" and has advocated for federal measures to help ...

NEA's Findings. Black, Latino, and Native students are less likely to have full access to the devices and broadband internet they need to learn than White students. NEA's report on digital equity illustrates the digital divide and homework gap in each state. Students in rural areas lag slightly in terms of access to the internet and devices ...

The Homework Gap. Left Offline from National School Boards Assoc. on Vimeo. Widespread home-based learning has highlighted a long-documented and persistent inequity of students that lack adequate broadband access. This digital divide, commonly known as the homework gap impacts millions of students. When the pandemic began, 15-16 million K-12 ...