Relationship-building and share learning Chevening is looking for individuals with strong professional relationship-building skills, who will engage with the Chevening community and influence and lead others in their chosen profession. Please explain how you build and maintain relationships in a professional capacity, using clear examples of how you currently do this, and outline how you hope to use these skills in the future.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Writing9 with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Include an introduction and conclusion

A conclusion is essential for IELTS writing task 2. It is more important than most people realise. You will be penalised for missing a conclusion in your IELTS essay.

The easiest paragraph to write in an essay is the conclusion paragraph. This is because the paragraph mostly contains information that has already been presented in the essay – it is just the repetition of some information written in the introduction paragraph and supporting paragraphs.

The conclusion paragraph only has 3 sentences:

- Restatement of thesis

- Prediction or recommendation

To summarize, a robotic teacher does not have the necessary disciple to properly give instructions to students and actually works to retard the ability of a student to comprehend new lessons. Therefore, it is clear that the idea of running a classroom completely by a machine cannot be supported. After thorough analysis on this subject, it is predicted that the adverse effects of the debate over technology-driven teaching will always be greater than the positive effects, and because of this, classroom teachers will never be substituted for technology.

Start your conclusion with a linking phrase. Here are some examples:

- In conclusion

- To conclude

- To summarize

- In a nutshell

Discover more tips in The Ultimate Guide to Get a Target Band Score of 7+ » — a book that's free for 🚀 Premium users.

- Check your IELTS essay »

- Find essays with the same topic

- View collections of IELTS Writing Samples

- Show IELTS Writing Task 2 Topics

Money is important in most people's lives. Although some people think it is more important than others. What do you feel are the right uses of money? What other factors are important for a good life? Give reasons for your answer and include any relevant examples from your experience.

More and more people are migrating to cities in search of a better life, but city life can be extremely difficult. explain some of the difficulties of living in a city. how can governments make urban life better for everyone, some people think that teachers should be able to ask disruptive children to leave the class for the overall benefit of the classroom. do you think it is the best way to deal with a disruptive child in the classroom what other solutions are there, some countries have introduced laws to limit working hours for employees. why are these laws introduced do you think this is a positive or negative development, some people say that all popular tv entertainment programmes should aim to educate viewers about important social issues. to what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement.

- Our Mission

Simple Relationship-Building Strategies

Embedding dual-purpose tasks in coursework can help teachers overcome the obstacles to forging strong relationships with students.

Educators all acknowledge that building strong relationships is a vital part of the educational process. In fact, it may be the first and most important step in getting students to learn. Strong relationships increase student motivation and reduce behavioral issues , and they improve student achievement and classroom climate.

Most teachers would love to spend more time building relationships with their students, but obstacles like time, the curriculum, and planning all get in the way. But there are ways for teachers to overcome these obstacles and see strong relationship growth with their students.

Time is a precious commodity in education, and the scant class time teachers have is often lost to outside factors like assemblies, standardized testing, meetings, and other expected and unexpected circumstances.

So it’s important to purposefully schedule class time to get to know students. While students are in groups, sitting with them and sharing in the learning process is a great way to learn more about them and tell them more about you as a person. You may ask relevant questions in the moment, or just listen for things to explore later.

One-on-one conferences are also great opportunities to get to know students. I’ve found that students of all grade levels are more open to sharing individually and also better able to discover things about me. I schedule two 5-minute conferences per week, so it takes weeks to meet with every student. I learn details related to their academic and personal lives, and I share some of those details with the class when appropriate, so the students also come to know each other better.

Lastly, before and after class a short walk with a student doesn’t eat precious class time but can go a long way in the relationship-building process. Try asking one kid per day one question about a non-school-related topic. The time spent uncovering and discovering student interests is time well spent.

Teachers can get overwhelmed teaching the long list of skills that accompany any curriculum and making sure students learn what they need for their class or grade level.

One way I’ve found to both teach the skills necessary to master the curriculum and build strong relationships is to have two purposes for the content and skills. As a high school English teacher, I’m able to form strong connections with my students by getting to know them through their writing.

While English is certainly a content that lends itself to discussions, the content doesn’t matter as much as the venue and the purpose. Choosing content-related activities that involve small-group or individual responses can go a long way. Often, I’ll use a website like Poll Everywhere to gather individual responses from students all at once, so no student is left out. In this way I learn about them collectively. Poll Everywhere is anonymous, but students will often reveal things that they wouldn’t otherwise and then break the anonymity by talking about their responses.

All content areas leave room for the teacher to share relevant personal anecdotes that help students see their teachers as human, opening doors for future interpersonal interactions. In history, ask students how they got their names. In science, ask about a genetic trait they think they inherited from their parents. In math, ask them why they think math is important.

The point is to make the content and curriculum personal and relevant, and to learn about the students while they learn the content. It’s a win-win.

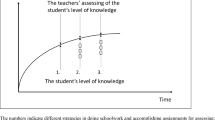

When planning, teachers make sure they’ll be teaching, assessing, and reassessing to measure learning and to form further instruction. They have the opportunity to also carefully plan assignments that bring their students’ interests to light. These interests may also be the catalyst for a strong connection between the teacher and the students.

To start the school year, I have my students do an All About Me presentation in which they share 10 facts about themselves and include pictures or video. I do the same presentation first, to model what I’m looking for—the added benefit is that students get to know me on a more personal level. An exercise like this can be modified for any age, and it can be done in any subject—teachers can modify it by asking a personal question about their discipline like, “How do you think physics plays a role in your everyday life?” or “Why do you think we need to learn geometry?”

I also create opportunities for my students to learn more about me and for me to learn more about them at the beginning of each unit throughout the year. I might share a personal story that revolves around a lesson activator, or we might discuss a big-picture question that lays the foundation for the unit. Because I make it a point to plan these opportunities, I can ensure that I don’t let all the other tasks get in the way.

Relationships are the foundation for everything else involved in teaching and learning. I want my students to know that I care about them, and I want them to care about me. Teaching them Shakespeare doesn’t always show them that, so I try to think creatively about how I can make sure I get to know every student in my room as well as I can, as quickly as I can, and as thoroughly as I can to make them as successful as I can.

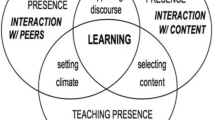

Relationships and Learning

- Posted May 29, 2008

Learning outside the home begins early in life. More than one-third of all U.S. children under the age of five are cared for outside of their homes by individuals not related to them. 1 Research on early childhood education shows that high-quality child care experiences support the development of social and academic skills that facilitate children's later success in school. There is also mounting evidence that close relationships between teachers and children are an important part of creating high-quality care environments and positive child outcomes.

As most parents and teachers know, children gain increasing control over their emotions, attention, and behavior across the early years. These growing abilities allow them to face and overcome new developmental challenges, from getting along with others to learning novel academic skills. 2 Despite their growing abilities, preschoolers sometimes find it difficult to regulate their thoughts and emotions in ways that allow them to succeed at new tasks. At these times, close relationships with meaningful adults, including teachers, can help children learn to regulate their own behavior.

The sense of safety and security afforded by close relationships with teachers provides children with a steady footing to support them through developmental challenges. This support may help the child work through a new academic challenge, such as learning to write a new letter of the alphabet; or the close relationship may help the child maintain a previously learned skill when confronted with a challenging new context. For instance, a child who is quite socially adept during circle time (a prior skill) might have more difficulty navigating these social interactions when he or she is over-tired from a missed nap (a challenging context).

In either case, when children "internalize" their teachers as reliable sources of support, they are more successful at overcoming challenges. In fact, having emotionally close relationships with child-care providers as a toddler has been linked with more positive social behavior and more complex play later as a preschooler. 3 Kindergartners with close teacher relationships have been shown to be more engaged in classroom activities, have better attitudes about school, and demonstrate better academic performance. 4 Thus, teacher-child relationships appear to be an important part of children's social and academic success in school.

Harvard Graduate School of Education Lecturer Jacqueline Zeller 's applied work in the Boston Public Schools and her research have been informed by this literature on teacher-student relationships. In the following interview, Zeller discusses the importance of teacher-student relationships for building students' sense of security and facilitating their readiness to learn at school.

What led you to study and consult regarding building positive teacher-student relationships?

Before beginning graduate school in psychology, my experiences teaching in elementary schools led me to believe that the relationships between children and teachers are powerful mechanisms for change. When students felt that I believed in them and supported their growth, they felt more confident both academically and socially at school. This belief was further strengthened in my graduate studies, as I began to apply attachment theories to teacher-child relationships. I decided to study how teachers' characteristics and children's characteristics work together to predict relationship quality, incorporating an attachment perspective. At that same time, I was working in schools, which was a natural venue for me to apply attachment theories to my consultation work, as I tried to help teachers in their efforts to join effectively with their students.

Why do you think socio-emotional development is important to discuss with regard to schools?

Often, we discuss social and emotional development very distinctly from academic growth. However, these ideas are very much intertwined. When children feel more secure at school, they are more prepared to learn. Children who feel this level of security are also generally more open to share how their lives outside of school are connected with ideas introduced in their classrooms. Educators have noted that these personal anecdotes help children build the foundations for literacy.

What do you think is important to think about when reflecting on teacher-student relationships?

Earlier research examining teacher-student relationships has tended to focus on how student's individual characteristics affect their relationships with teachers. While the individual characteristics that students bring to their relationships are very important, we know that as adults, we also bring experiences, beliefs, and characteristics that affect quality of relationships. It is important to consider what each individual brings to the relationship and how the relationship is affected by the contexts in which it is embedded. Most people relate easier with some children over others, but as adults in relationships with youth it is important that we reflect on what we bring to the table and seek support when we need it to most effectively help children and adolescents.

How do you feel that these principles match with your training of students in HGSE's Risk and Prevention and School Counseling program?

A primary goal of the Risk and Prevention and School Counseling Program at HGSE is to train future practitioners who practice prevention and intervention in school settings. We know that children and adolescents do not exist in a vacuum, but rather are bound by their contexts, including their home, schools, and neighborhoods. Students in our program are encouraged to understand how children's experiences are a function of these contexts. A major part of children's school contexts is their classroom environments and relationships with their teachers.

Currently, in addition to teaching at Harvard, I work as a clinician at an elementary school. I try to bring perspectives from my practice work to my courses at HGSE to provide some examples of how these theories are applied in real-world settings. Similarly, at their practicum sites, our students are encouraged to partner with children's teachers to foster safe and supportive relationships between teachers and children.

What are your hopes for where research and practice is heading in this field?

My hope is that researchers continue to examine these relationships contextually and reciprocally, acknowledging the complexity of these relationships. Reflective practice is important to understand how we as adults can help shape children and adolescents' contexts to facilitate their healthy development. Schools have increasing demands placed upon them with each passing year, so providing time for teachers and school staff to discuss and reflect on their relationships can be very difficult. However, I hope that as we continue to understand the powerful implications of these relationships for children, schools will protect time for teachers to discuss these relationships with colleagues, school psychologists, mentors, and consultants.

1 Johnson, J.0 (2005). Current population report: Who's minding the kids? Child care arrangements: Winter 2002. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Available online at http://www.census.gov/prod/2005pubs/p70-101.pdf .

2 Blair, C. (2002). School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children's functioning at school entry. American Psychologist , 57, 111–127.

3 Howes, C., Matheson, C.C., & Hamilton, C.E. (1994). Maternal, teacher, and child care history correlates of children's relationships with peers. Child Development, 65, 264-273.

4 Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). The teacher-child relationship and children's early school adjustment . Journal of School Psychology, 35, 61-79 .

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Costs of Specialized Teaching

Why It Matters: Mandy Savitz-Romer

Learning From Mistakes

Register for our Hosted Whole Educator Collective! | Now Hiring!

Recently Visited

The Science of Relationships

Science: How Relationships Drive Learning

Our work at FuelEd is based on the principle that relationships drive learning. This first in a series of foundational articles outlining the scientific basis for FuelEd's program, how relationships drives learning, and why this knowledge matters to educators.

We talk about the importance of relationships in education a lot —but what does this even mean? What does it look like to build relationships in schools? Why does it even matter? We wrote this blog to help every person working in schools understands that relationships are not just “warm and fuzzy stuff” — they literally change the brain. And, that a focus on strong relationships isn’t another thing to add to an educator’s plate...it is the plate.

Humans are social creatures

For most of human history, humans have lived and learned in small communities, where relationships were our "natural habitat." Strong relationships offered the group: better protection, access to resources like food and water, and better opportunities for mating and caretaking. Strong relationships offered the individual: security, support, and belonging, all critical for survival.

Strong relationships are especially critical for the survival and development of children and youth. Unlike other mammals, many of which are born ready to fend for themselves and survive without support, humans begin life with an intense dependency on adults to meet their every need. We humans are born significantly "underdeveloped" compared to most other mammals, with 70% of our brain development taking place after birth .

We learn through relationships

This matrix of bonding, attachment, and interdependency became the ecological niche that shaped the human brain into a social organ with uniquely social instincts, such as the ability to...

- Anticipate someone’s thoughts based on what you know about them

- Predict someone's actions based on minute emotional expressions

- Convey complex information to diverse groups of people

- Pick up on threat by someone's body language

Over time, the skills that helped us do well in relationship became interwoven with the neuroanatomy and biochemistry of learning. Relationships helped us survive, and so we became wired to connect.

Our first learning happens through our first relationships

Because so much of our brain is unformed at birth, not only do we depend on our caregivers to tend to our every need, but the quality of their care will shape the formation of our brains and the people we become.

One prime example of this is the way our earliest relationships build the brain’s ability to self-regulate . Born without this capacity, humans utilize caregivers as an “external brain” while our own brains are “under construction.” The neural networks of a child’s brain are built through thousands upon thousands of interactions where an infant or child gets upset, a caregiver steps in to help them regulate and the child returns to a baseline of calm.

Each time our caregivers walk alongside us as we move from dysregulation to regulation, they help us form what will eventually become a well-worn path that we can tread — independent of their guidance or support. If our parents are able to help us effectively regulate our emotions, we develop our own abilities to do it ourselves later in life. Not only do our earliest relationships form a template for our brain, they also teach us what to expect from the world and other subsequent relationships:

- When children experience their caregivers as a secure base from which to explore and return to whenever they feel afraid, they come to believe the world is safe.

- When children experience repeated interactions where adults understand and tend to their needs and feelings, they learn that relationships are dependable and trustworthy.

- When children are treated consistently with sensitivity, love, and care, they learn, "I am valuable and worthy." As our very first relationship, the caregiver relationship forms the foundation of our relationship with ourselves.

Conversely, when a child doesn’t have a secure relationship early in life, a very different picture emerges:

- A child that never experiences someone attuning to and soothing their emotions, will struggle to self-regulate.

- Instead of an expectation of safety, the child receives the message that the world is unpredictable and dangerous .

- The child may learn that relationships are negative, unsafe, and untrustworthy and naturally come to expect this from all future relationships.

- Lastly, without a secure early relationship (also known as a "secure attachment"), the child may learn to believe, "I am inherently defective, unworthy of love and belonging."

An insecure relationship with an early caregiver can create an environment where the very relationship meant to serve as a buffer to stress and threat — becomes the source of stress and threat. This insecure relationship may then trigger an excessive and persistent bodily stress response. Like revving a car engine for days or weeks at a time, persistent stress has a wear-and-tear effect that not only impacts brain development and learning but can have long-term mental and physical repercussions.

It also shapes day-to-day behavior. Children who have experienced trauma are known to be more reactive—they feel terror when faced with normal stressors. Fear and self-protection become an automated and habitual way of responding to the world.

Why does this matter to educators?

Not only does our first learning happen through our first relationships, our first relationships sets up our ability to learn.

While a student with a secure attachment history will come to class ready to learn, explore, connect with peers, seek contact with the teacher when in need, and persevere through difficult tasks, a student with an insecure attachment history will enter class with a shorter attention span, greater anxiety and aggression, poorer performance on cognitive tasks, and an unwillingness to explore the environment or seek out the teacher or peers for help.

It’s obvious that these two students are inequitably equipped to thrive in the classroom environment.

Our hope is that by sharing the science of relationships with educators we can help them to avoid the trap of either personalizing a student’s behavior — "what's wrong with me?" — or blaming a student — "whats wrong with you!?" Instead, hey will be able to see the challenging behavior of students, or colleagues, as a clue to that person’s relationship history and more likely to consider with compassionate curiosity, “what happened to you?”

When educators are able to see through this new lens, they will begin to perceive their own roles differently. One way or another, because learning happens through relationships, teachers are attachment figures. Our work at FuelEd is to ensure that as many teachers as possible become secure attachment figures.

To learn more about how to become a secure attachment figure check out Part Two in our Foundational Blog Series.

Bring FuelEd to your school, district, or organization

Explore more articles by FuelEd Founder & Partner Megan Marcus

About the author

Megan marcus, partner & founder - san diego ca.

Megan holds a B.A. in Psychology from the University of California at Berkeley and Master’s degrees in Psychology from Pepperdine University. While at Pepperdine, Megan studied under Dr. Louis Cozolino and served as the lead researcher for his book, The Social Neuroscience of Education . Megan then completed a Master’s degree in Education, Policy, and Management from Harvard University, where she explored how to translate the elements of a therapists’ professional training to an educational setting. Her research with Dr. Cozolino and studies at Harvard combined to form the core beliefs that became the bedrock of FuelEd. Since 2012, Megan has passionately served the educational community as FuelEd’s Founder.

Get the latest from our blog

Social Emotional Learning for Teachers - Podcast

Join Megan Marcus and Kelley Munger as guests on the Getting Smart Podcast with Rebecca Midles to discuss SEL for Teachers and Relationship Building in classrooms, schools, and districts.

FuelEd Receives $1 Million in Grant Funding From Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

FuelEd is thrilled to announce that we have received a $1 million grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) in order to promote supportive teacher communities and boost teacher well-being, and to promote Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging for educators of color.

Understanding Anxious Attachment Styles

At its core, anxious attachment styles involve amplification of stress behaviors in order to keep caregivers close and available.

FUELED NEWSLETTER

Inspiration & resources on adult sel and educator wholeness, let's get in touch, stay updated, subscribe to our newsletter, invest in fueled, custom form.

- Professional development

Why leadership is about building relationships

- Facebook facebook

- Twitter twitter

- Linkedin linkedin

- Whatsapp whatsapp

- Facebook facebook (opens in a new window)

- Twitter twitter (opens in a new window)

- Linkedin linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Whatsapp whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Developing networks and relationships with peers has always been an important part of successful leadership. Vice-Principal, External Relations at the University of Glasgow, explains why.

Rachel Sandison , Vice-Principal, External Relations at the University of Glasgow, shares why nurturing relationships and expanding networks is crucial for opening doors to new opportunities and becoming an inspiring and successful leader.

Last year, perhaps more so than any other, we witnessed the positive impact of collaboration and partnership.

The pandemic has reinforced the importance of connection and brought into sharp focus the benefits of individual and institutional alliances. But developing networks and relationships with peers has always been an important part of successful leadership, and I am privileged to have the opportunity to engage with colleagues from across the globe who continually help to inform my thinking, share best practice and open the doors to new opportunities.

At an early stage in my career, I took advantage of mentoring opportunities within my organisation, and through this was introduced to volunteering for the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) where I began to make contacts in universities across the sector through conference attendance and informal networking.

As a CASE Global Trustee today, I continue to benefit from these relationships with colleagues that are based on mutual respect and reciprocity. These colleagues, and now friends, I entrust with both my successes and my failures.

In no small part, I am a Vice-Principal now because of the guidance and support I have gained through my many networks, and because these relationships gave me the chance to chart career paths of peers that had either been unknown to me, or discounted as impossibilities.

The adage is that ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’, and being able to see and celebrate the successes of role models within the sector gave me both an indication of what was possible, and the desire to achieve it.

I now have the pleasure of acting as a mentor to others, and always look to encourage the potential of talent both within and outside of my organisation.

My advice to Chevening Scholars, and to anyone who wants to become a successful leader, is to say ‘yes’ wherever possible!

Be open to trying new things, to volunteering your time and expertise, and to fostering relationships with peers that will provide a platform for mutually beneficial exchange and support; and do so always being your authentic self. And, most importantly, enjoy these opportunities and the journey they will take you on.

Related news

Why effective leaders aren’t afraid to ask for help

Few things will help you progress your career as effectively as maintaining active and mutually supportive networks. When and why should we call on them for guidance and support?

Embracing change

Just about the only thing you can guarantee in life is change. How can we learn to embrace it and become inspiring leaders?

Making difficult career choices

Career paths are not always clear. It’s highly likely that there will be times in almost every professional journey where the next step is not obvious. How should we face these difficult decisions?

Advertisement

A Reflective Essay on Creating a Community-of-Learning in a Large Lecture-Theatre Based University Course

- Published: 23 June 2020

- Volume 55 , pages 363–377, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Huibert P. de Vries 1 &

- Sanna Malinen 1

342 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

“Community” It’s everywhere! In thousands of geographical locations throughout the land people gather in small, medium, and large groups (or dispersed associations) for some common purpose. (Lenning and Ebbers 1999 , p. 17)

The benefits of creating learning communities have been clearly established in educational literature. However, the research on ‘community-of-learning’ has largely focused on intermediate and high-school contexts and on the benefits of co-facilitation in the classroom. In this paper, we contribute to educational research by describing an approach for a large (1000 + students/year), lecture-theatre based, university management course. This approach largely excludes co-facilitation, but offers a unified and integrated approach by staff to all other aspects of running the course. By applying an ethnographic methodology, our contribution to the ‘community-of-learning’ literature is a set of strategies that enable a sense of belonging and collective ownership amongst all participants in the course. We describe the experienced benefits, as well as challenges, of such teaching, as we outline the methods we use to enhance students’ perception of belonging to a community-of-learning. We conclude by making recommendations as to the requirements of adopting a community-of-learning teaching approach to tertiary education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Investigating blended learning interactions in Philippine schools through the community of inquiry framework

Swedish students’ everyday school life and teachers’ assessment dilemmas: peer strategies for ameliorating schoolwork for assessment

A systematic review of pedagogies that support, engage and improve the educational outcomes of Aboriginal students

Quotes reflect the views of student feedback from voluntary and anonymous course and teaching evaluations.

The city of Christchurch experienced a number of devastating earthquakes during 2010 and 2011.

Booker, K. C. (2007). Perceptions of classroom belongingness among African American college students. College Student Journal, 41 (1), 178–186.

Google Scholar

Brooks, K., Adams, S. R., & Morita-Mullaney, T. (2010). Creating inclusive learning communities for ELL students: Transforming school principals' perspectives. Scholarship and Professional Work: Education (Paper 2, pp. 1–9). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/coe_papers/2 .

Buckley, F. J. (2000). Team teaching: What, why and how? . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Carpenter, D. M., Crawford, M., & Walden, R. (2007). Testing the efficacy of team teaching. Learning Environments Research, 10 (1), 53–65.

Article Google Scholar

Chanmugam, A., & Gerlach, B. (2013). A co-teaching model for developing future educators’ teaching effectiveness. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 25 (1), 110–117.

Cohen, M. B., & DeLois, K. (2002). Training in tandem: Co-facilitation and role modeling in a group work course. Social Work with Groups, 24 (1), 21–36.

Easterby-Smith, M., & Olve, N. G. (1984). Team-teaching: Making management education more student-centered? Management Education and Development, 15 (3), 221–236.

Gaudent, S., & Robert, D. (2018). A journey through qualitative research . London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10 (3), 157–172.

Gaus, N. (2017). Selecting research approaches and research designs: A reflective essay. Qualitative Research Journal, 17 (2), 99–112.

George, M. A., & Davis-Wiley, P. (2000). Team teaching a graduate course. College Teaching, 48 (2), 75–80.

Hamera, J. (2011). Performance ethnography. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage book of qualitative research (pp. 317–329). Thousand Oak, CA: Sage.

Harris, C., & Harvey, A. N. C. (2000). Team teaching in adult higher education classrooms: Toward collaborative knowledge construction. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 87 , 25–32.

Hatcher, T., & Hinton, B. (1996). Graduate student’s [sic] perceptions of university team-teaching. College Student Journal, 30 (3), 367–376.

Kehrwald, B. (2007, 3–5 December). The ties that bind: Social presence, relations and productive collaboration in online learning environments, Ascilte 2007 , Singapore.

Kerridge, J., Kyle, G., & Marks-Maran, D. (2009). Evaluation of the use of team teaching for delivering sensitive content: A pilot study. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33 (2), 93–103.

Laughlin, K., Nelson, P., & Donaldson, S. (2011). Successfully applying team teaching with adult learners. Journal of Adult Education, 40 (1), 11–17.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate perioheral participation . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lenning, O. T., & Ebbers, L. H. (1999). The powerful potential of learning communities: Improving education for the future. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 26 (6), 1–173.

Lester, J. N., & Evans, K. R. (2009). Instructors' experiences of collaboratively teaching: Building something bigger. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20 (3), 373–382.

Moxley, D. P. (2004). Engaged research in higher education and civic responsibility reconsidered. Journal of Community Practice, 12 (3–4), 235–242.

Neilsen, E. H., Winter, M., & Saatcioglu, A. (2005). Building a learning community by aligning cognition and affect within and across members. Journal of Management Education, 29 (2), 301–318.

Nevin, A. I., Thousand, J. S., & Villa, R. A. (2009). Collaborative teaching for teacher educators: What does the research say? Teaching and Teacher Education, 29 , 569–574.

QS Top Universities. (2018). Business and management studies . Retrieved September 10, 2018 from https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/university-subject-rankings/2018/business-management-studies .

Shapiro, N. S., & Levine, J. H. (1999). Creating learning communities: A practical guide to winning support, organizing for change, and implementing programs . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Sparkes, A. C. (1992). Research in physical education: Exploring alternative visions . London: The Falmer Press.

Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic Interview . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Tedlock, B. (2011). Braiding narrative ethnography with memoir and creative nonfiction. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage book of qualitative research (pp. 331–339). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wenger, M. S., & Hornyak, M. J. (1999). Team teaching for higher level learning: A framework of professional collaboration. Journal of Management Education, 23 (3), 311–327.

Young, M. B., & Kram, K. E. (1996). Repairing the disconnects in faculty teaching teams. Journal of Management Education, 20 (4), 500–515.

Zhao, C., & Kuh, G. D. (2004). Adding value: Learning communities and student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45 (2), 115–138.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand

Huibert P. de Vries & Sanna Malinen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Huibert P. de Vries .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

de Vries, H.P., Malinen, S. A Reflective Essay on Creating a Community-of-Learning in a Large Lecture-Theatre Based University Course. NZ J Educ Stud 55 , 363–377 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-020-00165-1

Download citation

Received : 24 September 2019

Accepted : 11 April 2020

Published : 23 June 2020

Issue Date : November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-020-00165-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Team teaching

- Community-of-learning

- Lecture-theatre based

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Publications

On-demand strategy, speaking & workshops, latest articles, write for us, library/publications.

- Competency-Based Education

- Early Learning

- Equity & Access

- Personalized Learning

- Place-Based Education

- Post-Secondary

- Project-Based Learning

- SEL & Mindset

- STEM & Maker

- The Future of Tech and Work

Lona Running Wolf on Education Reform and Cultural Preservation

Sarah elizabeth ippel on the cultivate project and global citizenship, yu-ling cheng on remake learning days, jennifer mellor and mike huckins on how chambers of commerce can get involved in accelerated pathways, recent releases.

New Pathways Handbook: Getting Started with Pathways

Unfulfilled Promise: The Forty-Year Shift from Print to Digital and Why It Failed to Transform Learning

The Portrait Model: Building Coherence in School and System Redesign

Green Pathways: New Jobs Mean New Skills and New Pathways

Support & Guidance For All New Pathways Journeys

Unbundled: Designing Personalized Pathways for Every Learner

Credentialed Learning for All

AI in Education

For more, see Library | Publications | Books | Toolkits

Microschools

New learning models, tools, and strategies have made it easier to open small, nimble schooling models.

Green Schools

The climate crisis is the most complex challenge mankind has ever faced . We’re covering what edleaders and educators can do about it.

Difference Making

Focusing on how making a difference has emerged as one of the most powerful learning experiences.

New Pathways

This campaign will serve as a road map to the new architecture for American schools. Pathways to citizenship, employment, economic mobility, and a purpose-driven life.

Web3 has the potential to rebuild the internet towards more equitable access and ownership of information, meaning dramatic improvements for learners.

Schools Worth Visiting

We share stories that highlight best practices, lessons learned and next-gen teaching practice.

View more series…

About Getting Smart

Getting smart collective, impact update, prioritize building relationships with your students: what science says.

- Learning Design

By: Devin Vodicka, Sabba Quidwai and Kristin Gagnier

As we enter the one-year mark of the COVID-19 global pandemic, the magnitude of the challenges in education has disrupted the status quo and has compelled a general reconsideration of where we should focus our collective efforts for the optimal benefit of our students. While terms such as “learning loss” are garnering significant attention, this is also a time when it may be helpful to step back and ask some foundational questions such as this: What is most important to our students?

Students want to be valued and to feel connected to their learning environment. For example, the Vista Unified School District (San Diego County, CA) conducted over sixty forums with students in 2013. Students clearly articulated a desire to be recognized for their strengths, have more choices, extend their learning beyond the classroom, and progress at their own rates. Students often expressed frustration about how much of their school experience is focused on individual achievement and that they craved social connectedness and peer interactions. Six years later, the same themes emerged; in a series of forums in 2019 , the XQ Institute asked high school students what they wanted from school. Students want teachers who care about them as individuals.

When we listen to our students they tell us that they want to be engaged in learning, connected to school, motivated to learn, and persist amidst challenges. They want to feel connected to their teachers, peers, and to their learning environment. Unfortunately, our students have also been telling us that their experience does not match their aspirations. Gallup has published data from a massive set of student surveys demonstrating that students tend to be less engaged in their learning as they matriculate from elementary to middle to high school. In the highly-populated state of California, the 2019 California Healthy Kids Survey reported that only 53% of 11th grade students reported feeling connected to their school, a decline from just 62% in 7th grade.

All of this data was collected before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted schooling, compelled social distancing, and has led to a significant level of stress and trauma among our students and throughout society. While data is still being collected, it is almost certain that COVID has exacerbated challenges of engagement, belonging, and motivation with students and teachers feeling disconnected from peers, colleagues, and teachers amidst virtual learning. Many perceive a teacher’s role, and the role of school in general, is to ensure students master academic content and skills. Yet, teaching and learning is, at its core, a relational endeavor. Humans are social beings who learn from and thrive through connections with others. Thus, prioritizing relationship building — between teachers and students, students and peers, and teachers and colleagues – will support a positive learning environment that benefits students, teachers, and the broader community. As a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences on teaching during a crisis notes, “The first priorities need to be equity and the health, well-being, and connections among students, families, and teachers.” This article focuses on the benefits of relationships for students.

How Relationships Benefit Students

High-quality relationships between students and teachers, and students and their peers, have academic and social benefits. Positive emotional states that spark interest, engagement, excitement, and positive emotional relationships, that involve trust, value, and empathy, allow for learning. Students of all ages flourish when their teachers are responsive to their needs, emotionally supportive, and set high expectations for all students. Students learn, perform best, and develop skills and confidence when their educational experiences provide high support to foster engagement, show them they belong and are valued, and are culturally sensitive to the students’ experiences and needs. Feeling connected, valued, and respected by peers is equally important for students’ sense of belonging and engagement in school. Being supported and valued engenders feelings of physical and emotional security, which benefits learning. Emotionally supportive and trustworthy relationships can buffer against the impacts of adversity and trauma (such as violence, crime, abuse, psychological trauma, homelessness, racism, food, and housing insecurity). Negative emotions, such as anxiety, lack of confidence, fear, and negative relationships, that involve coercion and punishment, reduce one’s capacity to learn .

All students will, at some point, feel stressed and experience moments of challenge (academic or social) and failure. To help students develop capacities to successfully manage stress and academic and social setbacks, educators can foster relationships and create emotionally and physically safe environments for students. These include interacting with each and every student, engaging in teaching practices that elevate student voice and creating a collaborative atmosphere between peers, teaching with a variety of diverse materials and strategies, and setting high expectations for all students. Teachers can teach social skills and coping strategies. These include modeling empathy, respect, and compassion, teaching students calming strategies and how to effectively manage emotions, resolve conflicts, and create effective routines. These strategies, combined with supportive relationships with peers and teachers, empower students to believe they can succeed, even in difficult situations.

Taking Action

All educators have an opportunity to reframe our responsibilities and promote positive peer relationships. There are several research-backed strategies that we recommend to develop social and emotional learning capacities to support skills, mindsets, and practices that support learning

- Prioritize building a positive classroom environment in which students and teachers form positive, trusting relationships. Elevate student voice and promote their sense of belonging in the classroom community.

- Foster positive student behaviors by teaching social and emotional skills, intrapersonal awareness, and conflict resolution. Model empathy and engage in instructional strategies that encourage self-directed learning and motivation.

- Provide opportunities to practice social-emotional skills and mindsets inside and outside of the classroom. These skills include self-awareness of one’s emotions and perceptions, self-management of stress and emotions, and social awareness such as empathy, cooperation, communication, and responsibility.

- View disciplinary problems as an indicator of a developmental need or skillset that needs to be taught. Such educative and restorative approaches to classroom management and discipline help teach students how to manage conflicts and self-regulate.

Illustrative Examples: How to Focus on Relationships

Below we provide several illustrative examples to showcase how individual teachers, instructional specialists, principals, and schools have focused on building relationships.

How One Teacher Sets Aside Time to Build Relationships with Students

In a 2018 Edutopia article entitled Simple Relationship-Building Strategies , Sean Cassel shared several strategies to overcome barriers to building relationships with students. For example, Sean noted that teachers’ time often is usurped by other professional duties which make it challenging to devote time to getting to know individual students. To overcome this, Sean sets aside time for one-on-one, get to know you, conferences. Sean notes that “students of all grade levels are more open to sharing individually and also better able to discover things about me.” To make meeting each student feasible, Sean schedules two, 5-minute conferences per week, which means it can take weeks to meet with each student. During these meetings Sean learns details about their academic and personal experiences. When appropriate, Sean shares details of their lives with the larger class, so that students can also get to know each other better.

Sean begins each school year with an “All About Me” presentation in which students share 10 facts about themselves and include pictures or video. Sean does the same presentation first, to model what he is looking for and to allow students to better get to know him. Sean notes that this activity can work with any age and subject and that teachers can modify it by asking a personal question about their discipline like, “How do you think physics plays a role in your everyday life?” or “Why do you think we need to learn geometry?” An added benefit – this activity can be done in-person or virtually.

How to Build Relationships Across the School (during a pandemic!)

In response to COVID-19 pandemic, the educational landscape changed dramatically. Schools shifted, almost overnight, to online instruction. As teachers, instructional specialists, principals, and schools rapidly prepared for academic instruction online, they were faced with an equally-daunting task; how to prioritize relationships during distance learning? As outlined in the National Academies of Sciences 2020 Publication entitled Teaching K-12 Science and Engineering During a Crisis , many rose to the occasion using inventive approaches.

For example, a K-5 science specialist (working in an East Coast urban school that primarily serves students from low-income families) responded to COVID-19 by providing weekly informal engineering engagement opportunities for students. During these engagements, students tried to identify real-life problems and possible solutions to them. Students’ goal was to build the solution at home. To make this possible for these families, the science specialist partnered with local stores (such as Walmart, Costco, and Home Depot) that donated the building supplies. As noted in the report, these engagement hours were scheduled from 6 – 7 pm on Friday evenings, but students often requested to stay online chatting and sharing ideas and plans engineering designs until 9 pm! Students were so energized and excited by these opportunities that about 90 percent of students who had originally expressed interest, returned weekly for these sessions.

The school’s principal was so impressed by this and immediately recognized the need for building relationships with students, that the principal hosted a schoolwide virtual hangout every Friday. During these hangouts teachers and students danced and played guessing games, and the winner each week received a gift card for at least $25.

How One School Changed Their Culture to Focus on Positive Peer Relationships

Design 39, a public, K-8 school in the Poway Unified School District (San Diego County), has made social-emotional learning, collaboration, and relationships a top priority . Collaborative group work is a cornerstone of instruction and helps students develop relationship skills to establish and maintain supportive relationships and to effectively navigate diverse individuals and groups and social awareness skills to understand the perspectives of and empathize with others. Every day students are randomly assigned a “table group” where they work with different students and each are assigned different roles in the group. This helps students learn to work together, each having a unique role to play in the collaboration. The goal of this table group is to foster experiences that help learners develop strong relationships, collaboration skills, and gain a deeper degree of self-awareness (an understanding of one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behavior).

Relationships are at the heart of meaningful learning. We can and must attend to the social dynamics of learning by providing opportunities for students to develop their emotional awareness and skills by providing a safe, secure environment that promotes interaction in pursuit of creative problem-solving and conflict resolution. By shifting to learner-centered experiences, including the examples shared in this article, we can empower all students to know themselves, see themselves as full of possibilities, and shine as changemakers.

Want to Know More?

We hope you are inspired to take action! Here are some additional resources that might help.

- Strengthening Relationships with Students from Diverse Backgrounds by the Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest

- Resources for Building Teacher-Student Relationships by Education Northwest

- Why you should care about how people are feeling by Katie Martin

- 10 strategies to get to know your students and create an inclusive learner-centered culture by Katie Martin

We encourage you to stay connected with the Global Science of Learning Network and to share your ideas on social media by using #GSOLN

This post was originally published at tdlc.ucsd.edu

Special thanks to Katie Martin for her feedback and ideation for this article.

Kristin Gagnier is the Director of Dissemination, Education, and Translation at the Science of Learning Institute at Johns Hopkins University.

Sabba Quidwai is an education researcher and host of the Sprint to Success with Design Thinking podcast.

Devin Vodicka

Discover the latest in learning innovations.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Related Reading

Multiple Choice

The portrait model.

The Story of Transforming A System: Spring Grove Schools

New Pathways Handbook: The Path to Pathways

Is this the right place for serious responses to this article? I'll post a few comments to see what happens...

"Students want to be valued and to feel connected to their learning environment. " Of course they do. We all want to feel valued and connected. If school is the second most prominent institution in a young person's life, after family, connection is going to be vitally important. We need enquire further by asking, "Should school be number two or would some other identity group be better to attach to?"

"Students clearly articulated a desire to be recognized for their strengths, have more choices, extend their learning beyond the classroom, and progress at their own rates." What would we think of any person who didn't aspire to these conditions? I'm astounded that it takes a "scientific study" to reveal these attitudes. Now that they have been remembered, the challenge is how to implement them. Personal attention and individualized instruction is more resource intensive and therefore more costly than the mass production model. How are we going to pay for them?

"strategies that we recommend to develop social and emotional learning capacities to support skills, mindsets, and practices that support learning" In addition to the strategies suggested in this article, perhaps we should consider easing those educators who still maintain a "spare the rod and spoil the child" attitude out of our school systems. We might want to address the inconsistent use of the concept of "learning" in the phrase above where "social and emotional learning" benefits from explanatory adjectives but "learning", unmodified, refers primarily to academic subjects for which we have standardized testing. Finally, I question whether schools should be saddled with responsibility for repairing the damage done by severely dysfunctional families and violent neighborhoods.

"Relationships are at the heart of meaningful learning." Yes! And relationships are also key to governing, law making and enforcement, family life, productive employment, and elder care. Bringing more effective ways of interpersonal relating into the hallways, classrooms, and administrative offices of schools will certainly be a boon to our larger society. Schools are a great place to start but we can't stop at the edge of the school campus.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Nominate a School, Program or Community

Stay on the cutting edge of learning innovation.

Subscribe to our weekly Smart Update!

Smart Update

What is pbe (spanish), designing microschools download, download quick start guide to implementing place-based education, download quick start guide to place-based professional learning, download what is place-based education and why does it matter, download 20 invention opportunities in learning & development.

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2022

Learning how relationships work: a thematic analysis of young people and relationship professionals’ perspectives on relationships and relationship education

- Simon Benham-Clarke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6053-9804 1 , 2 ,

- Jan Ewing ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1420-1116 3 ,

- Anne Barlow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7628-4589 2 &

- Tamsin Newlove-Delgado ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5192-3724 2

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 2332 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5179 Accesses

2 Citations

170 Altmetric

Metrics details

Relationships in various forms are an important source of meaning in people’s lives that can benefit their health, wellbeing and happiness. Relationship distress is associated with public health problems such as alcohol misuse, obesity, poor mental health, and child poverty, whilst safe, stable, and nurturing relationships are potential protective factors. Despite increased emphasis on Relationship Education in schools, little is known about the views of relationship professionals on relationship education specifically, and how this contrasts with the views of young people (YP). This Wellcome Centre for the Cultures and Environments of Health funded Beacon project seeks to fill this gap by exploring their perspectives and inform the future development of relationship education.

We conducted focus groups with YP ( n = 4) and interviews with relationship professionals ( n = 10). The data was then thematically analysed.

Themes from YP focus groups included: ‘Good and bad relationships’; ‘Learning about relationships’; ‘the role of schools’ and ‘Beyond Relationship Education’. Themes from interviews with relationship professionals included: ‘essential qualities of healthy relationships’; ‘how YP learn to relate’ and ‘the role of Relationship Education in schools’.

Conclusions

YP and relationship professionals recognised the importance of building YP’s relational capability in schools with a healthy relationship with oneself at its foundation. Relationship professionals emphasised the need for a developmental approach, stressing the need for flexibility, adaptability, commitment and resilience to maintain relationships over the life course. YP often presented dichotomous views, such as relationships being either good or bad relationships, and perceived a link between relationships and mental health. Although not the focus of current curriculum guidance, managing relationship breakdowns and relationship transitions through the life course were viewed as important with an emphasis on building relational skills. This research suggests that schools need improved Relationship Education support, including specialist expertise and resources, and guidance on signposting YP to external sources of help. There is also potential for positive relationship behaviours being modelled and integrated throughout curriculums and reflected in a school’s ethos. Future research should explore co-development, evaluation and implementation of Relationship Education programmes with a range of stakeholders.

Peer Review reports

Relationships in various forms are an important source of meaning in people’s lives that can benefit their health, well-being and happiness [ 1 ]. ‘A ‘distressed’ relationship is one with a severe level of relationship problems, which has a clinically significant negative impact on their partner’s wellbeing. Those in ‘distressed’ relationships report regularly considering separation/divorce, quarrelling, regretting being in their relationship, being unhappy in their relationship, for example’ [ 2 ]. A growing evidence base shows that distress in relationships is associated with public health priorities such as alcohol misuse, obesity, mental health problems, and child poverty, whilst safe, stable, and nurturing relationships are potential protective factors [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. For young people (YP), there is evidence of a significant link between well-being and romantic relationships, suggesting that these relationships (when healthy) can positively influence self-concept, social integration and social support [ 6 ]. However, research indicates that some early romantic relationships can act as stressors regardless of their nature, whilst YP are negotiating other developmental tasks. For example, Olson and Crosnow’s longitudinal analysis [ 7 ] suggested that adolescent romantic relationships are associated with increased depressive symptomatology, particularly for girls.

The term ‘relationship’ has been defined as an enduring association between two persons [ 8 ]. The terms ‘healthy’ or ‘quality’ relationships have been described, defined and measured in various ways. They are ‘complex and ambiguous constructs’ with factors varying for each type of relationship [ 9 ]. Attempts to reach a definition tend to focus on interaction and positive and negative relationship characteristics and behaviours such as the existence or absence of caregiving, respect, support, emotional regulation, and the ability to learn from experience [ 10 , 11 ]. It has been theorised that early intervention and the development of these relationship skills in YP may allow them to negotiate early romantic relationships better as well as improve the quality and/or health of adult relationships, normalise help-seeking behaviour and prevent or manage relationship breakdown [ 12 , 13 ]. In their 2014 Manifesto, the Relationships Alliance Footnote 1 called upon The Department for Education (DfE) “to develop standards for those delivering RSE (Relationship and Sex Education) and set an expectation that schools recognise that developing relational capability is an important function of education and a child’s future” [ 14 ]. Relational capability refers to the capacity to form and maintain safe, stable, and nurturing relationships [ 15 ].

In 2019, DfE published statutory guidance in England on Relationship and Sex Education (RSE) [ 16 ], following the passing of the Children and Social Work Act 2017 [ 17 ]. The new Act stipulates Footnote 2 that pupils should learn about safety in forming and maintaining relationships; the characteristics of ‘healthy’ relationships and how relationships may affect physical and mental health and well-being. However, schools have been largely left to work out how to deliver this sensitive area of education, with little practical content guidance to date [ 18 ]. Skills for ‘healthy’ romantic relationships have also been relatively neglected both in research and practice. There are several programmes developed for YP that teach about relationships, but those that currently exist are mainly from the US, and generally focussed on sexual health or relationship violence [ 19 , 20 ]. Similarly, research with YP on their perspectives of RSE mostly focus on their views on sex education [ 21 ]. Therefore, despite the increased emphasis on delivering RSE in schools, Footnote 3 little is known about how YP view this aspect of the curriculum, or what outcomes they feel it should deliver. This is an important gap to fill to engage YP with the curriculum, and to lay the groundwork for the design, adaptation and evaluation of healthy relationship programmes. Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) work conducted in a prior project [ 22 ] by some of the authors demonstrated a great appetite in YP to learn more about relationships.

Our Beacon project, funded by The Wellcome Centre for the Cultures and Environments of Health, is focussed on ‘Transforming relationships and relationship transitions with and for the next generation’ in two strands (Healthy Relationship Education (HeaRE) and Healthy Relationship Transitions (HeaRT)). As part of the project, we conducted qualitative interviews and focus groups with young people and relationship professionals, with the aims of exploring their perspectives on relationships and relationship education. This paper presents and integrates the findings of these studies, to inform the development of future Relationship Education.

Recruitment

YP were recruited from a convenience sample of community groups and schools in South-West England, across urban, suburban and rural settings. Young people were contacted through school and youth group leaders, who made the first approach to participants. YP consented for themselves if aged 16 and over; for under 16 s, both parent and young person consent was sought. The YP formed four focus groups with a total of 24 participants. The two focus groups conducted in schools were with Years 9 and 10 pupils (aged 14 to 16 years). Following PPI consultation, these were set up separately for boys and girls; one group with eight girls and one with seven boys. The community group focus groups included young people aged between 14 and 18 and had one group with four boys and one with two boys and three girls.

A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit the relationship professionals, seeking out key people who are likely to provide rich sources of information or data [ 22 ]. Here, ten nationally based relationship professionals (three men and seven women) were purposively sampled for their recognised expertise in the field of romantic relationships either through their research interests or because they were psychotherapists or counsellors. All had a minimum of 15 years of experience in their chosen field, and most had many more. Consent in writing or by audio recording was obtained before the interview.

Focus groups with YP were used due to their suitability for exploring ideas within their social context [ 23 , 24 ]. The topic guides were developed and refined through accompanying consultations with YP in our Youth Panel PPI sessions. Content included questions and prompts around views on relationships, experiences of Relationship Education, and what YP wanted to get from participating in Relationship Education. The first two focus groups were conducted face-to-face in February 2020. Due to COVID-19, the procedure had to be adapted for the latter two, which were conducted on Microsoft Teams in the summer of 2020. The focus groups were audio-recorded and conducted by TND and SBC with each lasting approximately an hour.

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with the relationship professionals by JE. An interview schedule for the relationship professionals was devised, piloted and refined in team discussions. The topics relevant to this paper were the views of the relationship professionals on what constituted an enduring, mutually satisfying intimate partner relationship, how older children can learn the skills needed to identify healthy and unhealthy relationships and the role, content and delivery of Relationship Education. The interviews were conducted by telephone since there are no significant differences between telephone and face-to-face interview data [ 25 ] and given COVID-19 restrictions at the time. The duration of each interview was 64 min on average.

The focus groups with YP and the interviews with professionals were analysed separately rather than in combination, as interview schedules and formats were different for both. Transcription was conducted by an approved University service. NVivo 12 was used to manage the data, analysed using the thematic approach described by Braun and Clark [ 26 ]. In both datasets, a second author coded the first transcripts. Variations between coders were discussed by the team. Themes were developed separately for the YP and the relationship professionals; in this paper we present and compare these themes, identifying difference and similarities in the Discussion section.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was gained from the University of Exeter Medicine School (UEMS) Research Ethics Committee (reference: Jun20/D/229∆1) for the research with YP and the University of Exeter College of Social Sciences and International Studies Research Ethics Committee for research involving relationship professionals (reference: 201,920–017).

The ethical approach we took is based on the successful and tested approach used by the Shackleton Project (UEMS ethics number 201617–018). We developed a protocol, agreed with teachers and community group leaders, for actions to be taken should a participant appear distressed, wish to withdraw, or should concerns be raised. We were highly aware that this could be a sensitive area, and emphasised to participants that they could withdraw at any point, as well as ensuring that they were aware of sources of support, and of confidential ways to contact the researchers, teachers, or community group leaders (e.g. through private chat on Teams) if they needed to. Researchers were alert throughout the groups for verbal and non-verbal signs that YP might wish to leave or take a break from the discussions, and strategic pauses or break points were included to facilitate this. The researchers were both experienced and well placed to conduct the focus groups with YP. The topics discussed with YP were framed to young people as being around ‘healthy relationships’ and existing RSE guidance. Our approach throughout the research was to engage young people in helping us to understand how Relationship Education could be improved for all YP in general. We used and explained Chatham House Rules to participants but were aware that this is not sufficient as the only measure. Therefore, we used appropriate distancing techniques, discouraging and steering conversations away from personal disclosures as needed and framing questions accordingly, for example, ‘what should young people get out of Relationship Education? We developed a protocol, agreed with teachers and community group leaders, for actions to be taken should a participant appear distressed, wish to withdraw, or should concerns be raised.

All names referred to below are pseudonyms.

- Young people

‘Good’ and ‘bad’ relationships

When asking what was meant by relationships YP appeared to be most comfortable and forthcoming in discussing relationships using dichotomous terms. Typically, relationships were categorised as positive or negative, such as good, bad, right, wrong, comfortable, uncomfortable, successful, unsuccessful, healthy and unhealthy. There was also a frequently expressed concept of ‘normal’ versus ‘abnormal’ relationships, which linked to a desire to be taught how to have a ‘normal relationship’, although few participants challenged this.

’Like there are bad sides of a relationship, there’s the good side of the relationship’. (Male) ’I don’t think I was ever taught in school about what a normal relationship is or how a relationship works’. (Male) ‘… I don’t want to be too forceful in this cookie-cutter idea of what good and bad relationships are, ... people are free to do what they want’. (Female)

YP attempted to define the qualities involved in ‘healthy’ or ‘normal’ relationships differently. Trust, respect and having common ground were often mentioned. Communication was also seen as being crucial, which linked to handling conflict the ‘right’ way. They also recognised that these qualities were involved in the different stages of relationships.

‘Well, I think a lot about healthy relationships in general is to do with communication. And starting a relationship and establishing what you want from the relationship is very important, and the same with finishing a relationship and saying to someone “I’m not happy with this because of this, this and this … . So, I think all of those stages really are about communication’. (Female)

Some YP introduced different sources of influence on relationships. They attributed importance to the role of upbringing and parental models. Again, ‘normality’ in relationships was present as a concept.

‘I think our parents are our closest role models really’. (Male) ‘ if you’ve been brought up in a domestic violence place or household, you’re never going to know until you grow up “Oh, that’s not okay, that’s not a normal thing ’. (Male)

In response to a question about how Relationship Education might help young people in different stages of their lives others commented on the influence of fairy tales, and Disney in particular; this was linked most strongly to gender roles and expectations in relationships.

‘I think it actually does create this toxic image to some degree… it’s very much the female is feeble, and she must be saved by the male, and it kind of creates a toxic masculinity’. (Female) ’It’s embedded into our heads that it’s always Prince Charming and it’s always the prince and the princess … you don’t understand it until you actually get to it, and that’s when you realise that it’s not like Disney movies or anything ...’. (Female).

Participants recognised that these ‘bad’ relationships early in life could have long-lasting impacts, including on mental health. This extended to the relationships between parents and children.

‘I’ve got so many friends who have fallen down mental health spirals due to bad relationships’. (Female) “Some parents, because they had such a rough childhood, treat their children the same thinking that it is the right way’. (Female).

Learning about relationships

There was a general feeling from many participants that Relationship Education would have a range of benefits for YP, across different kinds of relationships. Communication and conflict were critical areas where participants felt that there were skills, or ways of coping or doing things that they could learn.

’how to communicate effectively with our peers and partners, family members’. (Female) ’ [I would like to learn] Probably how to defuse an argument, … instead of having to shout at each other and maybe possibly break stuff and maybe even harm each other, and you can talk about it responsibly’. (Male)

Some of the desired outcomes involved learning how to manage different stages in relationships; for example, how to sustain happy relationships, and how to end relationships that could not be sustained, and cope with the aftermath. There was also a sense that they were sometimes taught about ‘red flags’ (signs that relationships are unhealthy), but not how then to end the relationships.

’ the basic foundations of relationships, like how to keep it running, happy…’. (Male) ’if you’ve tried to maintain them but it… keeps happening, you just need to know how to end it nicely’. (Male) ’It is all well knowing the signs, but if you don’t know how to get out of an unhealthy relationship what is the point of knowing that it is unhealthy?’ (Female)

Some participants felt that focussing on relationships with themselves as a first step would have greater long-term benefits and could help YP avoid abusive relationships. One participant had their own experience of where they felt Relationship Education had an impact on their well-being but thought it would have been more beneficial if taught sooner.

’… that is a big thing for people our age more – accepting themselves rather than being in a relationship with other people. Their mental health more than other people’. (Female). ’ it has made me be more… conscious of my relationships and friendships, and I’m able to see which ones are bad and been able to cut off bad relationships…my mental health would be better now if that education had happened earlier’. (Female)

Some YP were thinking about how relationships might be challenged after leaving school or relocating, and how Relationship Education might prepare them for that, whilst others thought further ahead to when they might have families, and the potential impacts of Relationship Education in the longer term.

‘[after relationship education] If they were a parent, they would know how to treat their children and instead of the way their parents treated them, treat them a different way’. (Female)

The role of schools

YP saw schools as offering a neutral setting in which Relationship Education can be taught free from the potential influences and biases. This was thought to be critical, particularly for those who might have more challenging backgrounds, however a desire was expressed for a greater focus in schools on how relationships ‘work’ rather than on sex education.

‘people need to be taught about relationships in quite an unbiased environment, and school is the most likely place that’s going to happen’. (Female) ‘[Relationship lessons have] been very clinical. It’s not really teaching you anything to do with how the relationship works … For me, it’s just been the clinical side of sex, basically’. (Male)