Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Learning Disabilities - Neurological Bases, Clinical Features and Strategies of Intervention

The Child with Learning Difficulties and His Writing: A Study of Case

Submitted: 30 May 2019 Reviewed: 16 August 2019 Published: 20 November 2019

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.89194

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Learning Disabilities - Neurological Bases, Clinical Features and Strategies of Intervention

Edited by Sandro Misciagna

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

1,171 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

The purpose of this paper is to present one child with learning difficulties writing process in multigrade rural elementary school in México. It presents Alejandro’s case. This boy lives in a rural area. He shows special educational needs about learning. He never had specialized attention because he lives in a marginalized rural area. He was integrated into regular school, but he faced some learning difficulties. He was always considered as a student who did not learn. He has coursed 2 years of preschool and 1 year of elementary school. Therefore, this text describes how child writes a list of words with and without image as support. Analysis consists to identify the child’s conceptualizations about writing, his ways of approaching, and difficulties or mistakes he makes. The results show that Alejandro identifies letters and number by using pseudo-letters and conventional letter. These letters are in an unconventional position. There is no relationship grapheme and phoneme yet, and he uses different writing rules. We consider his mistakes as indicators of the learning process.

- writing difficulties

- learning difficulties

- writing learning

- writing process

- special education

Author Information

Edgardo domitilo gerardo morales *.

- Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, National Autonomous University of Mexico, México City, México

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

One of the purposes of Mexican education system is that students acquire conventional writing during first grades in elementary school [ 1 ]. This purpose consists of students to understand the alphabetical code, its meaning, and functionality. In this way, they can integrate into a discursive community.

The elementary school teacher teaches a heterogeneous group of children [ 1 , 2 ]. Some students show different acquisition levels of the writing. This is due to literacy environment that the family and society provide. Thus, some children have had great opportunities to interact with reading and writing practices than others. Therefore, some students do not learn the alphabetical principle of writing at the end of the scholar year. They show characteristics of initial or intermediate acquisition level of the writing. In this way, it is difficult for children to acquire writing at the same time, at the term indicated by educational system or teachers.

In addition, there may be children with learning difficulties in the classroom. Department of Special Education teaches some children. Students with special educational needs show more difficulties to learn than their classmates [ 3 ]. They require more resources to achieve the educational objectives. These authors point out that special educational needs are relative. These needs arise between students’ personal characteristics and their environment. Therefore, any child may have special educational needs, even if he/she does not have any physical disability. However, some students with learning difficulties do not have a complete assessment about their special educational needs. On the one hand, their school is far from urban areas; on the other hand, there are not enough teachers of special education for every school. In consequence, school teachers do not know their students’ educational needs and teach in the same way. Thereby, students with learning difficulties do not have the necessary support in the classroom.

Learning difficulties of writing may be identified easily. Children with special educational needs do not learn the alphabetical principle of writing easily; that is, they do not relate phoneme with grapheme. Therefore, children show their conceptualizations about writing in different ways. Sometimes, teachers censor their students’ written productions because they do not write in a conventional way. Children with special educational needs are stigmatized in the classroom. They are considered as less favored. At the end of the scholar year, children do not pass.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to present one child with special educational needs writing process in a Mexican multigrade rural school. This text describes how the child writes a list of words with and without image as support. Analysis consists to identify the child’s conceptualizations about writing [ 4 ], his ways of approaching, and difficulties or mistakes he makes. These mistakes are the indicators of learning process [ 5 ].

This paper presents Alejandro’s case. This boy lives in a rural area. He shows special educational needs about learning. He never had specialized attention because he lives in a marginalized rural area. He was integrated into regular school, but he faced some learning difficulties. He was always considered as a student who does not learn. Therefore, this text describes Alejandro’s writing, what he does after 2 years of preschool and 1 year of elementary school.

2. Children with learning difficulties and their diagnosis

According to the National Institute for the Evaluation of Education [ 6 ], Mexican education system provides basic education (preschool, elementary, and secondary school) for students with special educational needs. There are two types of special attention: Center of Multiple Attention (CAM, in Spanish) and Units of Service and Support to Regular Education (USAER, in Spanish). In the first one, children with special educational needs go to this Center. These children receive attention according to basic education and their educational needs. In the second, specialized teachers on special education go to school and provide support to students. These teachers provide information to school teachers too. In this way, there is educational equity and inclusion in Mexican school [ 7 ].

Physical appearance : Teacher describes the child’s physical characteristics. These features indicate the type of food the student eats, care his or her person, the parents’ attention, among other elements.

Behavior observed during the assessment : In this section, the teacher should record the conditions in which the assessment was carried out: child’s attitude, behavior, and interest.

Child’s development history : This section presents conditions in which pregnancy developed, physical development (ages in which child held his/her head, sat, crawled, walked, etc.), language development (verbal response to sounds and voices, age in which said his/her first words and phrases, etc.), family (characteristics of their family and social environment, frequent activities, etc.), hetero-family history (vision, hearing, etc.), medical history (health conditions, diseases, etc.), and scholar history (age at which he/she started school, type of school, difficulties, etc.).

Present condition : In this, there are four aspects:

It refers to student’s general aspects: intellectual area (information processing, attention, memory, understanding, etc.), motor development area (functional skills to move, take objects, position of his/her body, etc.), communicative-linguistic area (phonological, semantic, syntactic and pragmatic levels), adaptation and social interaction area (the child’s skills to initiate or maintain relationships with others), and emotional area (the way of perceiving the world and people). In each one, it mentions the instruments he suggests, although there is not enough information about them [ 3 ].

The second aspect is the curricular competence level. Teacher identifies what the student is capable of doing in relation to established purposes and contents by official curriculum.

The third aspect is about the learning style and motivation to learn. It presents physical-environmental conditions where the child works, their interests, level attention, strategies to solve a task, and the incentives he receives.

The fourth aspect is information about the student’s environment: factors of the school, family, and social context that influence the child’s learning.

Psycho-pedagogical assessment allows to identify children’s general educational needs. In this way, the school teacher could have information about the students’ difficulties. However, it is a general assessment. It contains several aspects and does not go deeper into one.

Therefore, this paper does not propose a new assessment. It consists of presenting one child’s writing difficulties, his ways of conceptualizing writing, and some mistakes he gets to make.

3. Students with learning difficulties and their scholar integration

Since 1993, Mexican system education has tried to offer special education services to students with special educational needs in basic education [ 8 ]. The first step was to promote the integration of these children in regular education classrooms. However, only insertion of the student in the school was achieved. Therefore, the system of education searched for mechanisms to provide advice to teacher. In this way, student with learning difficulties can be attended at the same time in the classroom [ 8 ].

Educational integration has been directly associated with attention of students with learning difficulties, with or without physical disabilities [ 8 ]. However, this process implies a change in the school. For this, it is necessary to provide information and to create awareness to the educational community, permanent updating of teachers, joint work between teacher, family, and specialized teachers.

At present, Mexican education system looks at educational integration as process in which every student with learning difficulties is supported individually [ 9 ]. Adapting the curriculum to the child is the purpose of educational integration.

Curricular adequacy is one of the actions to support students with learning difficulties [ 10 , 11 ]. This is an individualized curriculum proposal. Its purpose is to attend the students’ special educational needs [ 3 ]. At present, Mexican education system indicates that there should be a curricular flexibility to promote learning processes. However, it is important to consider what the child knows about particular knowledge.

Regarding the subject of the acquisition of written language, it is necessary to know how the children build their knowledge about written. It is not possible to make a curricular adequacy if teachers do not have enough information about their students. However, children are considered as knowledge builders. Therefore, there are learning difficulties at the process.

4. Alejandro’s case

This section presents Alejandro’s personal information. We met him when we visited to his school for other research purposes. We focused on him because the boy was silent in class. He was always in a corner of the work table and did not do the activities. For this, we talked with his teacher and his mother to know more about him.

Alejandro is a student of an elementary multigrade rural school. He was 7 years old at the time of the study. He was in the second grade of the elementary school. His school is located in the region of the “Great Mountains” of the state of Veracruz, Mexico. It is a rural area, marginalized. To get to this town from the municipal head, it is necessary to take a rural taxi for half an hour. Then, you have to walk on a dirt road for approximately 50 min.

Alejandro’s family is integrated by six people. He is the third of the four sons. He lives with his parents. His house is made of wood. His father works in the field: farming of corn, beans, and raising of sheep. His mother is a housewife and also works in the field. They have a low economic income. Therefore, they receive a scholarship. One of his older brothers also showed learning difficulties at school. His mother says both children have a learning problem. But, they do not have any money for attending their sons’ learning difficulties. In addition, there are no special institutes near their house.

The boy has always shown learning difficulties. He went to preschool for 2 years. However, he did not develop the necessary skills at this level. At classes, this child was silent, without speaking. Preschool teachers believed that he was mute. Nevertheless, at scholar recess, he talked with his classmates. Alejandro was slow to communicate with words in the classroom.

When he started elementary school, Alejandro continued to show learning difficulties. At classes, he was silent too. He just watched what his classmates did. He did not do anything in the class. He took his notebook out of his backpack and just made some lines. Occasionally, he talked with his classmates. When the teacher asked him something, Alejandro did not answer. He looked down and did not answer. He just ducked his head and stayed for several minutes.

When Alejandro was in second grade, he did different activities than his classmates. His teacher drew some drawings for him and he painted these drawings. Other occasions, the teacher wrote some letters for him to paint. The child did every exercise during several hours. He did not finish his exercises quickly. Sometimes he painted some drawings during 2 h.

Although Alejandro requires specialized attention, he has not received it. He has not had a full psycho-pedagogical assessment at school by specialized teachers. His school does not have these teachers. Also, the child was not submitted to neurological structural examination or neurophysiological studies to exclude an organic origin of his learning difficulties. His parents do not have enough financial resources to do this type of study for him. In addition, one specialized institution that can do this type of study for free is in Mexico City. It is so far from child’s house. It would be expensive for the child’s parents. Therefore, he is only attended as a regular school student.

For this reason, this paper is interested in the boy’s writing process. This is because Alejandro coursed 2 years of preschool and 1 year of elementary school; however, he does not show a conventional writing yet. In this way, it is interesting to analyze his conceptualizations about writing and difficulties he experiences.

5. Methodology

The purpose of this paper is to know the child’s ways to approach writing spontaneously and his knowledge about the writing system. For this, the author used a clinical interview. He took into account the research interview guide “Analysis of Disturbances in the Learning Process of Reading and Writing” [ 12 ].

The clinical interview was conducted individually. We explored four points, but we only present two in this text: to write words and to write for image.

Interviewer took the child to the library room at school. There were no other students. First, the interviewer gave the child a sheet and asked to write his name. Alejandro wrote his name during long time. Interviewer only asked what it says there. He answered his name: “Alejandro.” Next, the interviewer asked the child to write some letters and numbers he knew. Alejandro wrote them. The interviewer asked about every letter and number. The child answered “letter” or “number,” and its name.

To write words : The interviewer asked the child to write a group of words from the same semantic field in Spanish (because Alejandro is from Mexico) and one sentence. Order of words was from highest to lowest number of syllables. In this case, interviewer used semantic field of animals. Therefore, he used following words: GATO (cat), MARIPOSA (butterfly), CABALLO (horse), PERRO (dog), and PEZ (fish). The sentence was: EL GATO BEBE LECHE (The cat drinks milk). The interviewer questioned every written word. He asked the child to show with his finger how he says in every written production.

To write for image : This task was divided into two parts. The first analyzed the size and second analyzed the number.

Interviewer used the following image cards: horse-bird and giraffe-worm ( Figure 1 ). Every pair of cards represents a large animal and a small animal.

Cards with large and small animals.

The purpose of this first task was to explore how the child writes when he looks at two images of animals with different size. The animal names have three syllables in Spanish: CA-BA-LLO (horse), PA-JA-RO (bird), etc. In this way, we can see how the child writes.

The interviewer used the following pair of cards for second task ( Figure 2 ).

Cards for singular and plural.

First card shows one animal (singular) and the second shows some animals (plural). In this way, we search to explore how the child produces his writings when he observes one or more objects, if there are similarities or differences to write.

The interviewer asked what was in every card. Next, he asked the child to write something. Alejandro wrote something in every picture. Afterward, the interviewer asked the child to read every word that he wrote. Child pointed with his finger what he wrote.

After, the interview was transcribed for analysis. We read the transcription. The author analyzed every written production. He identified the child’s conceptualizations about writing. He compared the written production and what the child said. In this way, the analysis did not only consist to identify the level of writing development. This text describes the child’s writing, the ways in which he conceptualizes the writing, the difficulties he experienced to write, and his interpretations about writing.

6. Alejandro’s writing

This section describes Alejandro’s writing process. As we already mentioned, Alejandro is 7 years old and he studies in the second grade of the elementary school. His teacher says the child should have a conventional writing, because he has already coursed 1 year of elementary school, but it is not like that. Most of his classmates write a conventional way, but he does not.

We organized this section in three parts. The first part presents how Alejandro wrote his name and how he identifies letters and numbers; the second part refers to the writing of words; and the third part is writing for picture.

6.1 Alejandro writes his name and some letters and numbers

The first part of the task consisted of Alejandro writing his name and some letters and numbers he knows. His name was requested for two reasons. The first reason is to identify the sheet, because the interviewer interviewed other children in the same school. Also, it was necessary to identify every written productions of the group of students. The second reason was to observe the way he wrote his name and how he identified letters and numbers.

The interviewer asked the child to write his name at the top of the sheet. When the interviewer said the instructions, Alejandro was thoughtful during a long time. He was not pressed or interrupted. He did not do anything for several seconds. The child looked at the sheet and looked at everywhere. After time, he took the pencil and wrote the following on the sheet ( Figure 3 ).

Alejandro’s name.

The interviewer looked at Alejandro’s writing. He asked if something was lacking. The interviewer was sure that Alejandro knew his name and his writing was not complete. However, Alejandro was thoughtful, and looked at the sheet for a long time. The interviewer asked if his name was already complete. The child answered “no.” The interviewer asked the child if he remembered his name. Alejandro denied with his head. So, they continued with another task.

Alejandro has built the notion of his name. We believe that he has had some opportunities to write his name. Perhaps, his teacher has asked him to write his name on his notebooks, as part of scholar work in the classroom. We observed that Alejandro used letters with conventional sound value. This is because he wrote three initial letters of his name: ALJ (Alejandro). The first two letters correspond to the beginning of his name. Then, he omits “E” (ALE-), and writes “J” (ALJ). However, Alejandro mentions that he does not remember the others. This may show that he has memorized his name, but at that moment he failed to remember the others, or, these letters are what he remembers.

Subsequently, the interviewer asked Alejandro to write some letters and numbers he knew. The sequence was: a letter, a number, a letter, another letter, and number. In every Alejandro’ writing, the interviewer asked the child what he wrote. In this way, Alejandro wrote the following ( Figure 4 ).

Letters and numbers written by Alejandro.

For this task, Alejandro wrote for a long time. He did not hurry to write. He looked at sheet and wrote. The child looked at the interviewer, looked at the sheet again and after a few seconds he wrote. The interviewer asked about every letter or number.

We can observe that Alejandro differentiates between letter and number. He wrote correctly in every indication. That is, when the interviewer asked him to write a letter or number, he did so, respectively. In this way, Alejandro knows what he needs to write a word and what is not, what is for reading and what is not.

Also, we can observe that the child shows a limited repertoire of letters. He did not write consonants. He used only vowels: A (capital and lower) and E (lower). It shows us that he differentiates between capital and lower letter. Also, he identifies what vowels and letters are because the child answered which they were when the interviewer asked about them.

6.2 Writing words from the same semantic field

Asking the child to write words spontaneously is a way to know what he knows or has built about the writing system [ 12 ]. Although we know Alejandro presents learning difficulties and has not consolidated a conventional writing, it is necessary to ask him to write some words. This is for observing and analyzing what he is capable of writing, what knowledge he has built, as well as the difficulties he experiences.

The next picture presents what Alejandro wrote ( Figure 5 ). We wrote the conventional form in Spanish next to every word. We wrote these words in English in the parentheses too.

List of words written by Alejandro.

At the beginning of the interview, Alejandro did not want to do the task. He was silent for several seconds. He did not write anything. He looked at the sheet and the window. The interviewer insisted several times and suspended the recording to encourage the child to write. Alejandro mentioned he could not write, because he did not know the letters and so he would not do it. However, the interviewer insisted him. After several minutes, Alejandro took the pencil and started to write.

Alejandro wrote every word for 1 or 2 min. He required more seconds or minutes sometimes. He looked at the sheet and his around. He was in silence and looking at the sheet other times. We identified that he needs time to write. This shows that he feels insecure and does not know something for writing. He feels insecure because he was afraid of being wrong and that he was punished by the interviewer for it. It may be that in class he is penalized when he makes a mistake. There is ignorance because he does not know some letters, and he has a low repertoire of the writing system. Thus, Alejandro needs to think about writing and look for representing it. Therefore, this is why the child needs more time to write.

We identified that the child does not establish a phoneme-grapheme relationship. He only shows with his finger from left to right when he read every word. He does not establish a relationship with the letters he used. In each word, there is no correspondence with the number of letters. The child also does not establish a constant because there is variation in number and variety of letters sometimes.

Alejandro used letters unrelated to the conventional writing of the words. For example, when he wrote GATO (cat), Alejandro used the following letters: inpnAS. It is possible to identify that no letter corresponds to the word. Perhaps, Alejandro wrote those letters because they are recognized or remembered by him.

Alejandro shows a limited repertoire of conventional letters. This is observed when he uses four vowels: A, E, I, O. The child used these vowels less frequently. There is one vowel in every word at least. When Alejandro wrote PEZ (fish), he used two vowels. We observed that he writes these vowels at the beginning or end of the word. However, we do not know why he places them that way. Maybe this is a differentiating principle by him.

There is qualitative and quantitative differentiation in Alejandro’s writing. That is, he did not write any words in the same way. All the words written by him are different. Every word has different number and variety of letters. When two words contain the same number of letter, they contain different letters.

When Alejandro wrote MARIPOSA (butterfly), he used five letters. The number of letters is less than what he used for GATO (cat). Maybe he wrote that because the interviewer said “butterfly is a small animal.” This is because the cat is bigger than the butterfly. Therefore, it may be possible that he used lesser letters for butterfly.

In Spanish, PERRO (dog) contains five letters. Alejandro wrote five letters. In this case, Alejandro’s writing corresponds to the necessary number of letters. However, it seems that there is no writing rules for him. This is for two reasons: first, because there is no correspondence with the animal size. Horse is larger than dog and Alejandro required lesser letters for horse than for dog. Second, CABALLO (horse) is composed by three syllables and PERRO (dog) by two. Alejandro used more letters to represent two syllables. In addition, it is observed that there is a pseudo-letter. It looks like an inverted F, as well as D and B, horizontally.

When Alejandro wrote PEZ (fish), the interviewer first asked how many letters he needed to write that word. The child did not answer. Interviewer asked for this again and student said that he did not know. Then, interviewer said to write PEZ (fish). For several minutes, Alejandro just looked the sheet and did not say anything. The interviewer questioned several times, but he did not answer. After several minutes, Alejandro wrote: E. The interviewer asked the child if he has finished. He denied with his head. After 1 min, he started to write. We observed that his writing contains six letters. Capital letters are predominated.

Alejandro used inverted letters in three words. They may be considered as pseudo-letters. However, if we observe carefully they are similar to conventional letters. The child has written them in different positions: inverted.

May be there is a writing rule by Alejandro. His words have a minimum of four letters and a maximum of six letters. This rule has been established by him. There is no relation to the length of orality or the object it represents.

We can identify that Alejandro shows a primitive writing [ 4 ]. He is still in writing system learning process. The phoneticization process is not present yet. The child has not achieved this level yet. He only uses letters without a conventional sound value. There is no correspondence to phoneme-grapheme, and he uses pseudo-letters sometimes.

6.3 To write for image

Write for image allows us to know what happens when the child writes something in front of an image [ 12 ]. It is identified if there is the same rules used by the child, number of letters, or if there is any change when he writes a new word. It may happen that the length of the words is related to the size of the image or the number of objects presented. In this way, we can identify the child’s knowledge and difficulties when he writes some words.

6.3.1 The image size variable

The first task is about observing how the child writes when he is in front of two different sized images. That is, we want to identify if the image size influences on his writings. Therefore, two pairs of cards were presented to Alejandro. Every pair of cards contained two animals, one small and one large. The interviewer asked Alejandro to write the name on each one ( Figure 6 ).

Horse and bird writing.

Based on the writing produced by Alejandro, we mentioned the following:

Alejandro delimits his space to write. When he wrote for first pair of words, the child drew a wide rectangle and he made an oval and several squares for the second pair of words. The child wrote some letters to fill those drawn spaces. It seems that Alejandro’s rule is to fill the space and not only represent the word.

When Alejandro writes the words, we identified that he presents difficulty in the conventional directionality of writing. He wrote most of words from left to right (conventional directionality), but he wrote some words from right to left (no conventional). For example, the child started to write the second word on the left. He wrote seven letters. He looked at the sheet for some seconds. After, he continued to write other letters on the right. He wrote and completed the space he had left, from right to left.

Alejandro shows two ways to write: left–right (conventional) and right–left (no conventional). When he wrote the last word, the child wrote one letter under another. There was no limited space on the sheet. Alejandro wrote it there. The child has not learned the writing directionality.

When we compared Alejandro’s writings, we identified that the number of letters used by him does not correspond to the image size. Although the images were present and he looked them when he wrote, the child took into account other rules to write. The six names of animals had three syllables in Spanish and Alejandro used nine letters for CABALLO (horse) and eleven for PÁJARO (bird). The letters used by him are similar to the conventional ones. However, these are in different positions. There are no phonetic correspondences with the words. The child shows a primitive writing. Alejandro has not started the level of relation between phoneme and grapheme yet. We can believe that the boy wrote some letters to cover the space on the sheet. Alejandro takes into account the card size instead of the image size.

After writing a list of words, the interviewer asked Alejandro to read and point out every word he wrote. The purpose of this task is to observe how the child relates his writing to the sound length of the word. When Alejandro read CABALLO (horse), he pointed out as follows ( Figure 7 ).

Alejandro reads “caballo” (horse).

Alejandro reads every word and points out what he reads. In this way, he justifies what he has written. In the previous example, Alejandro reads the first syllable and points out the first letter, second syllable with the second letter. At this moment, he gets in conflict when he tries to read the third syllable. It would correspond to the third letter. However, “there are more letters than he needs.” When he reads the word, he shows the beginning of phoneticization: relation between one syllable with one letter. This is the syllabic writing principle [ 4 ]. Nevertheless, he has written more letters. Therefore, Alejandro says “o” in the other letters. In this way, we can point out that Alejandro justifies every letters and there is a correspondence between what he reads and what he writes.

When Alejandro reads the second word, the child pointed out as follows ( Figure 8 ).

Alejandro reads “pájaro” (bird).

Alejandro makes a different correspondence syllable-letter than the first word. Although his writing was in two ways, his reading is only one direction: from left to right. The first syllable is related to first three letters he wrote. The second syllable is related to the fourth letter. But, he faces the same problem as in the previous word: “there are many letters.” So he justifies the other letters as follows. He reads the third syllable in relation to the sixth and seventh letter. And, reads “o” for the other letters.

When interviewer showed the next pair of cards, Alejandro wrote as following ( Figure 9 ).

Giraffe and worm writing by Alejandro.

When the interviewer shows the pair of cards to Alejandro, the child said “It’s a zebra.” So, the interviewer said “It’s a giraffe and it’s a worm” and pointed out every card. The interviewer asked Alejandro to write the name of every animal. First, the child draws a rectangle across the width of the sheet. Next, he started to write on the left side inside the rectangle. He said the first syllable “JI” while writing the first letter. After, he said “ra,” he wrote a hyphen. Then, he said “e” and wrote another letter. At that moment, he looked at the sheet and filled the space he left with some letters ( Figure 10 ).

Giraffe writing.

Alejandro shows different rules of writing. These rules are not the same as previous. He delimited the space to write and filled the space with some letters. The child tries to relate the syllable with one letter, but he writes others. There is a limited repertoire of letters too. In this case, it seems that he used the same letters: C capital and lower letter, A capital and lower letter, and O. We believe that he uses hyphens to separate every letter. However, when he wrote the first hyphen, it reads the second syllable. We do not know why he reads there. Alejandro had tried to use conventional letters. He uses signs without sound value. In addition, there is no relation phoneme and grapheme.

When Alejandro wrote GUSANO (worm), he drew a rectangle and divided it into three small squares. Then, he drew other squares below the previous ones. After, he began to write some letters inside the squares, as seen in the following picture ( Figure 11 ).

Worm writing.

Alejandro used other rules to write. They are different than the previous. Alejandro has written one or two letters into every box. At the end, he writes some letters under the last box. There is no correspondence between what he reads and writes. There are also no fixed rules of writing for him. Rather, it is intuited that he draws the boxes to delimit his space to write.

6.3.2 Singular and plural writing

The next task consists to write singular and plural. For this, the interviewer showed Alejandro the following images ( Figure 12 ).

Cards with one cat and four cats.

Alejandro drew an oval for first card. This oval is on the left half of the sheet. He wrote the following ( Figure 13 ).

Alejandro writes GATO (cat).

Next, the interviewer asked Alejandro to write for the second card, in plural. For this, Alejandro draws another oval from the middle of the sheet, on the right side. The child did not do anything for 1 h 30 min. After this time, he wrote some different letters inside the oval ( Figure 14 ). He wrote from right to left (unconventional direction).

Alejandro writes GATOS (cats).

Alejandro wrote in the opposite conventional direction: from right to left. He tried to cover the delimited space by him. His letters are similar to the conventional ones. Also, there are differences between the first and the second word. He used lesser letters for first word than the second. That is, there are lesser letters for singular and more letters for plural. Perhaps, the child took into account the number of objects in the card.

The writing directionality may have been influenced by the image of the animals: cats look at the left side. Alejandro could have thought he was going to write from right to left, as well as images of the cards. Therefore, it is necessary to research how he writes when objects look at the right side. In this way, we can know if this influences the directionality of Alejandro’s writing.

With the next pair of images ( Figure 15 ), the interviewer asked Alejandro to write CONEJO (rabbit) and CONEJOS (rabbits).

Cards with one rabbit and three rabbits.

Alejandro draws a rectangle in the middle of the sheet for the first card (rabbit). He said “cone” (rab-) and wrote the first letter on the left of the sheet. Then, he said “jo” (bit) and wrote the second letter. He said “jo” again and wrote the third letter. He was thoughtful for some seconds. He started to write other letters. His writing is as follows ( Figure 16 ).

Alejandro writes CONEJO (rabbit).

At the beginning, Alejandro tries to relate the syllables of the word with first two letters. However, he justifies the other letters when he read the word. There is no exact correspondence between the syllable and the letter. As well as his writing is to fill the space he delimited.

Alejandro takes into account other rules for plural writing. He drew a rectangle across the width of the sheet. Starting on the left, he said “CO” and wrote one letter. Then, he said “NE” and drew a vertical line. After, he said “JO” and wrote other letters. His writing is as follows ( Figure 17 ).

Alejandro writes CONEJOS (rabbits).

Alejandro writes both words differently. He reads CONEJO (rabbit) for first word and CONEJOS (rabbits) for the second. Both words are different from each other. But, he wrote them with different rules. This is confusing for us because there are vertical lines between every two letters in the second word. We believe that the child tried to represent every object, although he did not explain it.

In summary, Alejandro shows different writings. He used pseudo-letters and conventional letter. These letters are in unconventional positions. There is no relationship between grapheme and phoneme yet; and, he uses different writing rules.

7. Conclusions

We described Alejandro’s writing process. According to this description, we can note the following:

Alejandro is a student of an elementary regular school. He presents learning difficulties. He could not write “correctly.” However, he did not have a full assessment by specialized teachers. His school is so far from urban areas and his parents could not take him to a special institution. Therefore, he has not received special support. Also, there is not a favorable literacy environment in his home. His teacher teaches him like his classmates. Usually, he has been marginalized and stigmatized because “he does not know or work in class.”

We focused on Alejandro because he was a child who was always distracted in class. We did not want to show his writing mistakes as negative aspects, but as part of his learning process. Errors are indicators of a process [ 5 ]. They inform the person’s skills. They allow to identify the knowledge that is being used [ 13 ]. In this way, errors can be considered as elements with a didactic value.

Alejandro showed some knowledge and also some difficulties to write. The child identifies and distinguishes letters and numbers. We do not know if he conceptualizes their use in every one. When he wrote, he shows his knowledge: letters are for reading, because he did not use any number in the words.

The writing directionality is a difficulty for Alejandro. He writes from left to right and also from right to left. We do not know why he did that. We did not research his reasons. But, it is important to know if there are any factors that influence the child to write like this.

The student does not establish a phoneme-grapheme relationship yet. He is still in an initial level to writing acquisition. He uses conventional letters and pseudo-letters to write. There are no fixed rules to write: number and variety of letters. However, we observed student’s thought about writing. He justifies his writings when he reads them and invents letters to represent some words.

There is still a limited repertoire of letters. He used a few letters of the alphabet. Therefore, Alejandro needs to interact with different texts, rather than teaching him letter by letter. Even if “he does not know those letters.” In this way, he is going to appropriate other elements and resources of the writing system.

Time he takes to write is an important element for us. He refused to write for several minutes at the beginning. After, he wrote during 1 or 2 min every word. As we mentioned previously, we believe that Alejandro did not feel sure to do the task. Perhaps, he thought that the interviewer is going to penalize for his writing “incorrectly.” He felt unable to write. Therefore, it is important that children’s mistakes are not censored in the classroom. Mistakes let us to know the child’s knowledge and their learning needs.

We considered that class work was not favorable for Alejandro. He painted letters, drawings, among others. These were to keep him busy. Therefore, it is important for the child to participate in reading and writing practices. In this way, he can be integrated into the scholar activities and is not segregated by his classmates.

About children with learning difficulties, it is important that these children write as they believe. Do not censor their writings. They are not considered as people incapable. It is necessary to consider that learning is a slow process. Those children will require more time than their classmates.

Special education plays an important role in Mexico. However, rather than attending to the student with learning difficulties in isolation, it is necessary that the teacher should be provided with information and the presence of specialized teachers in the classroom. In this way, the student with learning difficulties can be integrated into class, scholar activities, and reading and writing practices.

We presented Alejandro’s writing process in this paper. Although he was considered as a child with learning difficulties, we identified he shows some difficulties, but he knows some elements of the writing system too.

Acknowledgments

I thank Alejandro, his parents, and his teacher for the information they provided to me about him.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- 1. SEP. Aprendizajes Clave Para la Educación Integral. Plan y Programas de Estudio Para la Educación Básica. México, D.F.: Secretaria de Educación Pública; 2017. ISBN: 970-57-0000-1

- 2. SEP. Propuesta Educativa Multigrado 2005. México: Secretaria de Educación Pública; 2005

- 3. García-Cedillo E, Escalante I, Escandón M, Fernández L, Mustre A, Puga I. La Integración Educativa en el Aula Regular. Principios, Finalidades y Estrategias. México: Secretaría de Educación Pública; 2000. ISBN: 978-607-8279-18-0

- 4. Ferreiro E, Teberosky A. Los Sistemas de Escritura en el Desarrollo del Niño. México, D.F.: Editorial Siglo XXI; 1979. ISBN 968-23-1578-6

- 5. Dolz J, Gagnon R, Vuillet Y. Production écrite et Difficultés D’apprentisage. Genève: Carnets des Sciences de L’education. Université de Genéve; 2011. ISBN: 2-940195-44-7

- 6. INEE. Panorama Educativo de México. Indicadores del Sistema Educativo Nacional 2017. Educación Básica y Media Superior. México: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación; 2018

- 7. SEP. Modelo Educativo: Equidad e Inclusión. México: Secretaria de Educación Pública; 2017. ISBN: 978-607-97644-4-9

- 8. SEP. Orientaciones Generales Para el Funcionamiento de los Servicios de Educación Especial. México: Secretaria de Educación Pública; 2016. ISBN: 970-57-0016-8

- 9. SEP. Estrategia de Equidad e Inclusión en la Educación Básica: Para Alumnos con Discapacidad, Aptitudes Sobresalientes y Dificultades Severas de Aprendizaje, Conducta o Comunicación. México, DF: Secretaria de Educación Pública; 2018

- 10. Durán M. Las Adecuaciones Curriculares Individuales: Hacia la Equidad en Educación Especial. México: Secretaría de Educación Pública; 2016. ISBN 968-9082-33-7

- 11. CONAFE. Discapacidad Intelectual. Guía Didáctica Para la Inclusión en Educación Inicial y Básica. México: Secretaria de Educación Pública; 2010

- 12. Ferreiro E, Gómez M. Análisis de las Perturbaciones en el Proceso de Aprendizaje de la Lecto-Escritura. Fascículo 1. México: SEP-DGEE; 1982

- 13. Vaca J. Así Leen (Textos) los Niños. Textos Universitarios. México: Universidad Veracruzana; 2006. ISBN: 968-834-753-1

© 2019 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Learning disabilities.

Published: 17 June 2020

By Rakgadi Grace Malapela and Gloria Thupayagale-Tshw...

787 downloads

By Tatiana Volodarovna Tumanova and Tatiana Borisovna...

660 downloads

By Maria Tzouriadou

1021 downloads

- Armenia response

- Gaza response

- High contrast

- Press centre

Search UNICEF

Case studies on disability and inclusion.

To document UNICEF’s work on disability and inclusion in Europe and Central Asia region, UNICEF Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia has developed a set of five case studies.

UNICEF takes a comprehensive approach to inclusion, working to ensure that all children have access to vital services and opportunities. When UNICEF speaks about “inclusion” this encompasses children with and without disabilities, marginalized and vulnerable children, and children from minority and hard-to-reach groups.

The case studies have a specific focus on children with disabilities and their families. However, many of the highlighted initiatives are designed for broad inclusion and benefit all children. In particular, this case study, covers such topics as: Inclusive Preschool, Assistive Technologies (AT), Early Childhood intervention (ECI), Deinstitutionalisation (DI).

Case studies

Case study 1: “Open source AAC in the ECA Region”

Files available for download (1).

Case study 2: “Inclusive Preschool in Bulgaria”

Case study 3: “Assistive technology in Armenia"

Case study 4: “Early childhood intervention in the ECA region”

Case study 5: “Deinstitutionalization in the ECA region”

Living with Learning Difficulties: Two Case Studies Exploring the Relationship Between Emotion and Performance in Students with Learning Difficulties

- Conference paper

- Open Access

- First Online: 07 September 2020

- Cite this conference paper

You have full access to this open access conference paper

- Styliani Siouli 13 ,

- Stylianos Makris 14 ,

- Evangelia Romanopoulou 15 &

- Panagiotis P. D. Bamidis 15

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNISA,volume 12315))

Included in the following conference series:

- European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning

4562 Accesses

1 Citations

Research demonstrates that positive emotions contribute to students’ greater engagement with the learning experience, while negative emotions may detract from the learning experience. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of a computer-based training program on the emotional status and its effect on the performance of two students with learning difficulties: a second-grade student of a primary school with Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome and a fourth-grade student of a primary school with learning difficulties. For the purpose of this study, the “BrainHQ” web-based cognitive training software and the mobile app “AffectLecture” were used. The former was used for measuring the affective state of the students before and after each intervention. The latter was used for improving students’ cognitive development, in order to evaluate the possible improvement of their initial emotional status after the intervention with “BrainHQ” program, the possible effect of positive/negative emotional status on their performance, as well as the possible effect of high/poor performance on their emotional status. The results of the study demonstrate that there is a positive effect of emotion on performance and vice versa and the positive effect of performance on the emotional status and vice versa. These findings suggest that the affective state of students should be taken into account by educators, scholars and policymakers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

From perceived competence to emotion regulation: assessment of the effectiveness of an intervention among upper elementary students

Considering the emotional needs of students in a computer-based learning environment

Relationships between academic self-efficacy, learning-related emotions, and metacognitive learning strategies with academic performance in medical students: a structural equation model

- Learning difficulties

- Cognitive training

- Emotional status

- AffectLecture

- Performance

1 Introduction

Educational policy has traditionally paid attention to the cognitive development of students without focusing on how emotions adjust their psychological state and how this affects their academic achievement. Emotions have a large influence over mental health, learning and cognitive functions. Students go through various emotional states during the education process [ 1 ] thus their mental state is considered to play a major role in obtaining internal motivation [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Existing research in the field of education has shown however that students’ cognitive processes were far more important than emotional processes [ 5 ]. Therefore, educational research should take into consideration the experience of people with disabilities, including those with learning difficulties [ 6 ].

The definition of ‘learning difficulties’ (LD) is commonly used to describe students with intellectual/learning disabilities. For further specification, this group may be considered as a sub-group of all those students who face several disabilities such as physical, sensory, and emotional-behavioral difficulties, as well as learning difficulties [ 7 ].

Learning difficulties are considered to be a developmental disorder that occurs more frequently in school years. It is commonly recognized as a “special” difficulty in writing, reading, spelling and mathematics affecting approximately 15% to 30% of students total [ 8 ]. The first signs of the disorder are most frequently diagnosed from preschool age, either within the variety of speech disorders or within the variety of visual disturbances.

Students with learning difficulties (LD) within the middle school years typically display slow and effortful performance of basic academic reading and arithmetic skills. This lack of ability in reading and calculating indicates incompetence in cognitive processes that have far-reaching connotations across learning, teaching, and affective domains [ 9 ].

When it comes to obtaining certain academic skills, the majority of students with LD during their middle school years achieve fewer benefits in learning and classroom performance. Therefore, it’s inevitable the fact that as the time goes by, the gap becomes wider year after year and their intellectual achievements are considered to be less than the ones made by their peers [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. In addition to deficiencies in basic academic skills, many students with LD in the middle years of schooling may even have particular cognitive characteristics that slow the process of their learning, like reduced working memory capacity and also the use of unproductive procedures for managing the components of working memory. In conclusion, learners with LD require a more sufficient way of academic instruction [ 13 ].

Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome (SGBS) is a rare, sex-linked (X) disorder with prenatal and postnatal overgrowth, physical development and multiple congenital abnormalities. The primary reference to the disorder was made by Simpson et al. [ 14 ]. The phenotype of the syndrome broad and includes typical countenance, macroglossia, organomegaly, Nephrolepis, herniation, broad arms and legs, skeletal abnormalities, supraventricular neck, conjunctivitis, more than two nipples and constructional dysfunctions [ 15 ]. In line with Neri et al. [ 16 ], men have an early mortality rate and an expanded possibility of developing neoplasms from fetal age. Women are asymptomatic carriers of the gene, who frequently present coarse external features in the face and mental incapacity [ 17 ].

The psychomotor development of patients with SGBS is diverse and ranges from normal intelligence to moderate and severe disorder that may be appeared at birth [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Speech delay occurs in 50% of cases and motor delay in 36% [ 18 ].

Moreover, speech difficulties were appeared in most affected people, which are partially justified by macroglossia and cleft lip or palate. Affected boys show mild cognitive disorders that are not always related to speech delay and walking. Moreover, they face difficulty in fine and gross motor development [ 20 ].

Learning difficulties are frequently related to behavioral problems and ambiguities, attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity, concentration and writing disorders [ 21 ]. However, there has been limited research about the behavioral phenotype and the problematic behavior that progress during puberty, as well as the behavioral difficulties during the school years, which need mental health support and therapy [ 22 ].

There is a wide range of syndrome characteristics, which have not been identified or examined yet. Every new case being studied, found not to have precisely the same characteristics as the previous one. As new cases of SGBS appear, the clinical picture of the syndrome is consistently expanding [ 23 ].

1.1 Related Work and Background

Research has shown that children’s and youngsters’ emotions are associated with their school performance. Typically, positive emotions such as enjoyment of learning present positive relations with performance, while negative emotions such as test anxiety show negative relations [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Related work in the field of education, has indicated that students’ learning is related to their emotional state. Thus, negative emotions decrease academic performance, while positive emotions increase it [ 27 , 28 ]. However, recent studies have been based on specific emotions, disregarding the possible presence of other emotions that may have a significant impact on motivation and/or school performance [ 29 ].

At this same educational level, Yeager et al. [ 30 ] investigated the possible negative correlation between boredom and math activities, while Na [ 31 ] observed a negative correlation between anxiety and English learning. Likewise, Pulido and Herrera [ 32 ] carried out a study with primary, secondary and university students which revealed that high levels of fear predict low academic performance, irrespective of the school subject.

In addition, Trigueros, Aguilar-Parra, Cangas, López-Liria and Álvarez [ 33 ] in their study with adolescents indicated that shame is negatively related to motivation, which negatively adversely impacts learning and therefore academic performance. Moreover, Siouli et al. carried out a study with primary students which showed that emotion influences academic performance in all class subjects and that the teaching process can induce an emotional change over a school week [ 34 ]. The results of the aforementioned studies confirm a strong relationship between academic performance and students’ emotional state.

Several research studies have examined the relationship between emotions and school performance. For students with syndromes and learning difficulties, however, the only data that occur from our case studies.

2.1 Cognitive Training Intervention

The Integrated Healthcare System Long Lasting Memories Care-LLM Care [ 35 ] was exploited in this study, as an ICT platform that combines cognitive exercises (BrainHQ) with physical activity (wFitForAll). LLM Care was initially exploited in order to offer the important training for enhancing the elderly’s cognitive and physical condition of their health [ 36 ], as well as the quality of life and autonomy of vulnerable people [ 37 ].

BrainHQ [ 38 ], as the cognitive component of LLM Care, it is a web-based training software developed by Posit Science. It is the sole software available in Greek being used to any portable computing device (tablet, cell phone, etc.) as an application either on Android or on IOS provided in various languages. Unquestionably, enhancement of brain performance can lead to multiple benefits to everyday life. Both research studies and the testimonials of users themselves show that BrainHQ offers benefits in enhancing thinking, memory and hearing, attention and vision, improving reaction speed, safer driving, self-confidence, quality discussion and good mood. BrainHQ includes 29 exercises divided into 6 categories: Attention, Speed, Memory, Skills, Intelligence and Navigation [ 38 ].

Students’ training intervention attempts to fill some of the identified gaps in research and practice concerning elementary school students with learning difficulties and syndromes. Specifically, it aims to produce an intensive intervention to provide students with the required skills in order to engage them more successfully with classroom instruction. This intervention was designed as a relatively long-term, yet cost-effective, program for students with poor performance in elementary school.

BrainHQ software has therefore been used as an effort to cognitively train students with genetic syndromes and complex medical cases with psychiatric problems that go beyond cognitive function [ 39 , 40 ]. An intervention using BrainHQ could be a promising approach for individuals with Simpson-Golabi-Behmel and individuals with Learning Difficulties.

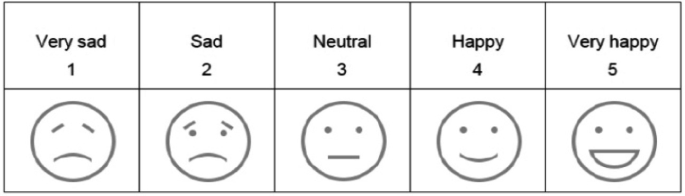

2.2 The AffectLecture App

AffectLecture application (courtesy of the Laboratory of Medical Physics AUTH: accessible for download through the Google Play market place) was utilized to measure the students’ emotional status. It is a self-reporting, emotions-registering tool and it consists of a five-level Likert scale measuring a person’s emotional status ranging from 1 (very sad) to 5 (very happy) [ 41 ].

2.3 Participants

I.M. (Participant A) is an 8-year-old student with Simpson-Golabi-Behmel Syndrome, who completed the second grade of Elementary School in a rural area of Greece and S.D. (Participant B) is a 10-year-old student with Learning Difficulties who completed the fourth grade of Elementary School in a provincial area in Greece.

Participant A performed a 30-session cognitive training intervention applied during school time (3–4 sessions/week for 45 min each). Few interventions were also conducted at the student’s house in order to complete the cognitive intervention program.

Participant B attended a 40-session training intervention at school during school time and at the student’s house (3 sessions/week for 45 min each for 8 weeks and then everyday sessions for the last two weeks of the interventions).

The cognitive training interventions were performed in classrooms, meaning that both students were in their own school environments and they received an equivalent cognitive training, although they faced different learning difficulties

Prior to the beginning of this study, both students were informed about the use of AffectLecture app by exploiting their tablets, in which the app was installed. The students’ were urged to state how they felt by selecting an emoticon. The emotional status was being measured before the start and by the end of each training intervention, for the entire duration of the training sessions. In Fig. 1 the students had to choose between five emoticons and select the one that best expressed them at that moment.

AffectLecture Input

Teachers provided at the beginning of each training intervention a unique 4-digit PIN, which let the students have access to the session and vote before and after it, so they could state their emotional status.

2.4 Research Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Students’ positive emotional state will have a positive effect on their performance, while students’ negative emotional state will have a negative effect on their performance.

Hypothesis 2: High students’ performance will have a positive effect on their emotional status, while poor students’ performance will have a negative effect on their emotional status.

2.5 Data Collection Methods

Students’ performance was assessed by the online interactive BrainHQ program. The detailed session results of BrainHQ and the students’ emotional status as measured by the AffectLecture app before and after each intervention were used in order to collect crucial data for the purpose of the study.

2.6 Data Collection Procedure

Before the beginning of the study, students were informed about the use of BrainHQ and the AffectLecture app, and they were instructed to have their tablets with them. The AffectLecture app was installed in both students’ devices. Accommodated test scores in 6 categories (Attention, Speed, Memory, Skills, Intelligence and Navigation cognitive performance) were being measured by BrainHQ interactive program. During each session students were trained equally in all six categories starting with Attention and moving on to Memory, Brain Speed, People Skills, Intelligence, and Navigation in order to benefit the most. Training time was equally spaced. Each time students completed an exercise level, they earned “Stars” according to their performance and progress in order to understand how their brain is performing and improving. The students’ emotional status was being measured before the beginning and by the end of each cognitive training session, throughout the intervention period.

2.7 Evaluation Methodology

A non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed-rank test was conducted to compare within interventions’ differences in emotional status. The AffectLecture responses of each student, before and after every intervention with BrainHQ cognitive training interactive program, were used for this comparison. Following that, a Spearman rank test was conducted to discover the relation between performance and emotional status variables. The significance threshold was set to 0.01 for all tests.

Concerning intervention results revealed a statistically significant difference in the emotional status before and after the intervention for participant A (Wilcoxon Z = −3.000, p = 0.003 < 0.01), as well as for participant B (Wilcoxon Z = −3.382, p = 0.001 < 0.01) as shown in Table 1 .

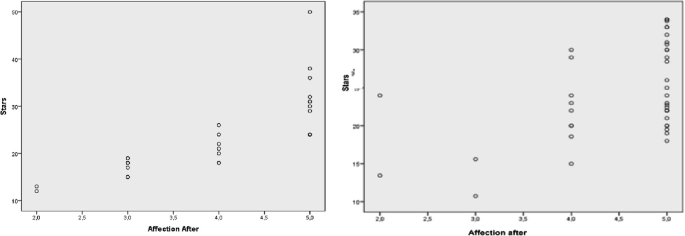

Furthermore, correlation coefficient Spearman Rho was used to measure the intensity of the relationship between the performance indicator provided by cognitive training program BrainHQ (stars) and the emotional status of participant A and participant B. As hypothesized, the performance may have a correlation with the affective state of the students.

The scatter diagrams (see Fig. 2 ) suggest a strong positive correlation between emotional status before the intervention and performance (BrainHQ stars) for participant A (Spearman rho r = 0.77, p = 0.000 < 0.01), as well as for participant B (Spearman rho r = −0.255, p = 0.112 > 0.01). Following the 0.01 criteria, the interpretation of the results shows that positive emotional status before the intervention tends to increase students’ performance during the cognitive training. More specifically, these findings illustrate the importance of positive emotions in the performance and other outcomes in relation with achievement, meaning that cognitive training intervention positively influenced students’ experiences in the level of performance.

Scatter Diagrams for emotional status before the intervention and performance in BrainHQ cognitive training interactive program for Participant A and B.

The scatter diagrams (see Fig. 3 ) also suggest a strong positive correlation between performance (BrainHQ stars) and emotional status for participant A (Spearman rho r = 0.896, p = 0.000 < 0.01), as well as for participant B (Spearman rho r = 0.433, p = 0.005 < 0.01). Following the 0.01 criteria, the interpretation of the results show that high performance during interventions tends to increase students’ emotional status after the cognitive training. Data on positive and negative emotions were obtained by asking each student to report their final emotional status on AffectLecture. An increase in happiness and motivation, was also observed when students’ performance was increased, while totally different emotions were expressed and signs of demotivation were observed when students’ performance was poor. These findings identify the impact of general well-being and happiness on performance.

Scatter Diagrams for emotional status after the intervention and performance in BrainHQ cognitive training interactive program for Participant A and B.

The correlation values coefficients (between emotional status before/after the intervention and performance) and their corresponding p- are included in Tables 2 and 3 .

4 Discussion

The present study was designed to investigate the influence of emotional state on students’ performance, as well as to identify the relations between cognitive performance and emotion. Specifically, the affective state of two elementary school students with learning difficulties was measured for long periods of time, by the AffectLecture app, before and after intervention with BrainHQ. Additionally, cognitive performance was measured by the online interactive BrainHQ program at the end of each session.

As hypothesized students’ positive emotional state had a positive effect on their performance. By contrast, students’ negative emotional state had a negative effect on their performance. It can be also concluded that high students’ performance had a positive effect on their emotional status, while poor students’ performance had a negative effect on their emotional status. Repeated measures revealed a significant positive effect of emotion on performance and vice versa and a positive effect of performance on emotional status and vice versa.

The results imply that performance influences students’ emotions, suggesting that successful performance attainment and positive feedback can develop positive emotions, while failure can escalate negative emotions. This set of case studies adds to the small body of empirical data regarding the importance of emotions in children with learning difficulties and syndromes.

The findings are in agreement with previous studies reporting that achievement emotions can profoundly affect students’ learning and performance. Positive activating emotions can positively affect academic performance under most conditions. Conversely, negative deactivating emotions are posited to uniformly reduce motivation implying negative effects on performance [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Numerous research studies have explored the relationship between emotional state and academic achievement. However, for pupils with Simpson Golabi Behmel syndrome and learning difficulties, the only available data comes from our case studies.

The findings of this research in sequence with BrainHQ available data (collected stars) reveal the significant contribution of the online brain training program (BrainHQ) to the cognitive enhancement of both students. The results from cognitive exercises and assessments in addition to students’ daily observation indicate that intervention with the BrainHQ program had a positive impact on cognitive function mainly in the area of visual/working memory and the capacity to retrieve and process new information, processing speed affecting daily life activities, attention, and concentration. Besides that, cognitive training improved students’ performance in solving learning problems and in the area of Memory, Speed, Attention, Skills, Navigation, and Intelligence [ 47 ].

At this point it is important to identify possible limitations of the present study design. The measurements that were performed cannot cover the total range of affecting factors that possibly impact participants’ cognitive performance and emotional state. Some of those factors, which were not included, could be: the level of intellectual disability/difficulty, language proficiency, family’s socioeconomic background, living conditions, intelligence, skills, and learning style.

The limitations of this study also consist of the research method (case study) that has often been criticized for its lack of scientific generalizability. For this reason the results of this study must be treated with caution and contain bias toward verification. Larger-scale studies should be conducted to prove the effect of emotional state on the cognitive function of children with learning difficulties/disabilities. On the other hand, case study research provides great strength in investigating units consisting of multiple variables of importance and it allows researchers to retain a holistic view of real-life events, such as behavior and school performance [ 48 ].

At this point, we should take into account that students tend to present their emotions as ‘more socially acknowledged’ when they are being assessed. Furthering this thought consideration must be given as to whether students consequently and intentionally modified their emotions and behaviours due to the presence of an observer, introducing further bias to the study.

Moreover, the knowledge of being observed can modify emotions and behaviour. Such reactivity to being watched is sometimes referred to as the “Hawthorne Effect”. The Hawthorne Effect refers to a phenomenon in which people alter their behaviour as a result of being studied or observed [ 49 ]. They attempt to change or improve their behaviour simply because it is being evaluated or studied. The Hawthorne Effect is the intrinsic bias that must be taken into consideration when studying findings.

5 Conclusions

The current study provides evidences that learning difficulties can be ameliorated by intensive adaptive training and positive emotional states. The results of a strong positive correlation between affective state and cognitive performance on BrainHQ indicate that the better the affective state of the student, the higher the performance, which was the hypothesis set by the authors. However, the causal direction of this relationship requires further investigation by future studies.

Developing and sustaining an educational environment, which celebrates the diversity of all learners, is circumscribed by the particular political-social environment, as well as the capacity of school communities and individual teachers to confidently embed inclusive attitudes and practice into their everyday actions. In addition, identifying and accounting for the various dynamics which influence and impact the implementation of inclusive practice, is fundamentally bound to the diversity or disability encountered in the classroom.

At the same time, it would be useful and promising to perform further research over a long period of time to investigate the influence of positive, neutral and negative affective states on students’ with cognitive and learning difficulties performance. Also, the findings could have significant implications understanding the effect of positive or negative emotions on cognitive function and learning deficits of children with learning disabilities. These findings obtained from the children after adaptive training suggest that positive emotional status during computer cognitive training may indeed enhance and stimulate cognitive performance with generalized benefits in a wide range of activities. It is essential, that this research continues throughout the school years of both students to evaluate the learning benefits.

Ultimately, more research on the relation between emotion and performance is needed for better understanding students’ emotions and their relations with important school outcomes. Social and emotional skills are key components of the educational process to sustain students’ developmental process and conduct an effective instruction. These findings may also suggest guidelines for optimizing cognitive learning by strengthening students’ positive emotions and minimizing negative emotions and the need to be taken into consideration by educators, parents and school psychologists.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., Perry, R.P.: Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37 , 91–105 (2002)

Article Google Scholar

Bergin, D.A.: Influences on classroom interest. Educ. Psychol. 34 , 87–98 (1999)

Krapp, A.: Basic needs and the development of interest and intrinsic motivational orientations. Learn. Instr. 15 , 381–395 (2005)

Hidi, S., Renninger, K.A.: The four-phase-model of interest development. Educ. Psychol. 41 , 111–127 (2006)

Frenzel, A.C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O.: Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: a reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 110 , 628–639 (2018)

Lambert, R., et al.: “My Dyslexia is Like a Bubble”: how insiders with learning disabilities describe their differences, strengths, and challenges. Learn. Disabil. Multidiscip. J. 24 , 1–18 (2019)

Woolfson, L., Brady, K.: An investigation of factors impacting on mainstream teachers’ beliefs about teaching students with learning difficulties. Educ. Psychol. 29 (2), 221–238 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802708895

Kaplan, H.I., Sadock, B.J.: Modern Synopsis of Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, IV. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore (1985)

Google Scholar

Graham, L., et al.: QuickSmart: a basic academic skills intervention for middle school students with learning difficulties. J. Learn. Disabil. 40 (5), 410–419 (2007)

Hempenstall, K.J.: How might a stage model of reading development be helpful in the classroom? Aust. J. Learn. Disabil. 10 (3–4), 35–52 (2005)

Cawley, J.F., Fan Yan, W., Miller, J.H.: Arithmetic computation abilities of students with learning disabilities: implications for instruction. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 11 , 230–237 (1996)

Swanson, H.L., Hoskyn, M.: Instructing adolescents with learning disabilities: a component and composite analysis. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 16 , 109–119 (2001)

Westwood, P.: Mixed ability teaching: issues of personalization, inclusivity and effective instruction. Aust. J. Remedial Educ. 25 (2), 22–26 (1993)

Simpson, J.L., Landey, S., New, M., German, J.: A previously unrecognized X-linked syndrome of dysmorphia. Birth Defects Original Art. Ser. 11 (2), 18 (1975)

Neri, G., Marini, R., Cappa, M., Borrelli, P., Opitz, J.M.: Clinical and molecular aspects of the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 30 (1–2), 279–283 (1998)

Gertsch, E., Kirmani, S., Ackerman, M.J., Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.: Transient QT interval prolongation in an infant with Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 152 (9), 2379–2382 (2010)

Golabi, M., Rosen, L., Opitz, J.M.: A new X-linked mental retardation-overgrowth syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 17 (1), 345–358 (1984)

Spencer, C., Fieggen, K., Vorster, A., Beighton, P.: A clinical and molecular investigation of two South African families with Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. S. Afr. Med. J. (SAMJ) 106 (3), 272–275 (2016)

Terespolsky, D., Farrell, S.A., Siegel-Bartelt, J., Weksberg, R.: Infantile lethal variant of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome associated with hydrops fetalis. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 59 (3), 329–333 (1995)

Hughes-Benzie, R.M., et al.: Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome: genotype/phenotype analysis of 18 affected males from 7 unrelated families. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 66 (2), 227–234 (1996)

Cottereau, E., et al.: Phenotypic spectrum of Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome in a series of 42 cases with a mutation in GPC3 and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 163C (2), 92–105 (2013)

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Behmel, A., Plöchl, E., Rosenkranz, W.: A new X-linked dysplasia gigantism syndrome: follow up in the first family and report on a second Austrian family. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 30 (1–2), 275–285 (1988)

Young, E.L., Wishnow, R., Nigro, M.A.: Expanding the clinical picture of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. Pediatr. Neurol. 34 (2), 139–142 (2006)

Goetz, T., Bieg, M., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., Hall, N.C.: Do girls really experience more anxiety in mathematics? Psychol. Sci. 24 (10), 2079–2087 (2013)

Pekrun, R., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L.: Introduction to emotions in education. In: International Handbook of Emotions in Education, pp. 11–20. Routledge (2014)