- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Prose

I. What is a Prose?

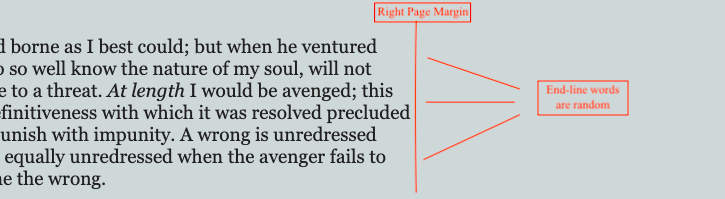

Prose is just non-verse writing. Pretty much anything other than poetry counts as prose: this article, that textbook in your backpack, the U.S. Constitution, Harry Potter – it’s all prose. The basic defining feature of prose is its lack of line breaks:

In verse, the line ends

when the writer wants it to, but in prose

you just write until you run out of room and then start a new line.

Unlike most other literary devices , prose has a negative definition : in other words, it’s defined by what it isn’t rather than by what it is . (It isn’t verse.) As a result, we have to look pretty closely at verse in order to understand what prose is.

II. Types of Prose

Prose usually appears in one of these three forms.

You’re probably familiar with essays . An essay makes some kind of argument about a specific question or topic. Essays are written in prose because it’s what modern readers are accustomed to.

b. Novels/short stories

When you set out to tell a story in prose, it’s called a novel or short story (depending on length). Stories can also be told through verse, but it’s less common nowadays. Books like Harry Potter and the Fault in Our Stars are written in prose.

c. Nonfiction books

If it’s true, it’s nonfiction. Essays are a kind of nonfiction, but not the only kind. Sometimes, a nonfiction book is just written for entertainment (e.g. David Sedaris’s nonfiction comedy books), or to inform (e.g. a textbook), but not to argue. Again, there’s plenty of nonfiction verse, too, but most nonfiction is written in prose.

III. Examples of Prose

The Bible is usually printed in prose form, unlike the Islamic Qur’an, which is printed in verse. This difference suggests one of the differences between the two ancient cultures that produced these texts: the classical Arabs who first wrote down the Qur’an were a community of poets, and their literature was much more focused on verse than on stories. The ancient Hebrews, by contrast, were more a community of storytellers than poets, so their holy book was written in a more narrative prose form.

Although poetry is almost always written in verse, there is such a thing as “prose poetry.” Prose poetry lacks line breaks, but still has the rhythms of verse poetry and focuses on the sound of the words as well as their meaning. It’s the same as other kinds of poetry except for its lack of line breaks.

IV. The Importance of Prose

Prose is ever-present in our lives, and we pretty much always take it for granted. It seems like the most obvious, natural way to write. But if you stop and think, it’s not totally obvious. After all, people often speak in short phrases with pauses in between – more like lines of poetry than the long, unbroken lines of prose. It’s also easier to read verse, since it’s easier for the eye to follow a short line than a long, unbroken one.

For all of these reasons, it might seem like verse is actually a more natural way of writing! And indeed, we know from archaeological digs that early cultures usually wrote in verse rather than prose. The dominance of prose is a relatively modern trend.

So why do we moderns prefer prose? The answer is probably just that it’s more efficient! Without line breaks, you can fill the entire page with words, meaning it takes less paper to write the same number of words. Before the industrial revolution, paper was very expensive, and early writers may have given up on poetry because it was cheaper to write prose.

V. Examples of Prose in Literature

Although Shakespeare was a poet, his plays are primarily written in prose. He loved to play around with the difference between prose and verse, and if you look closely you can see the purpose behind it: the “regular people” in his plays usually speak in prose – their words are “prosaic” and therefore don’t need to be elevated. Heroic and noble characters , by contrast, speak in verse to highlight the beauty and importance of what they have to say.

Flip open Moby-Dick to a random page, and you’ll probably find a lot of prose. But there are a few exceptions: short sections written in verse. There are many theories as to why Herman Melville chose to write his book this way, but it probably was due in large part to Shakespeare. Melville was very interested in Shakespeare and other classic authors who used verse more extensively, and he may have decided to imitate them by including a few verse sections in his prose novel.

VI. Examples of Prose in Pop Culture

Philosophy has been written in prose since the time of Plato and Aristotle. If you look at a standard philosophy book, you’ll find that it has a regular paragraph structure, but no creative line breaks like you’d see in poetry. No one is exactly sure why this should be true – after all, couldn’t you write a philosophical argument with line breaks in it? Some philosophers, like Nietzsche, have actually experimented with this. But it hasn’t really caught on, and the vast majority of philosophy is still written in prose form.

In the Internet age, we’re very familiar with prose – nearly all blogs and emails are written in prose form. In fact, it would look pretty strange if this were not the case!

Imagine if you had a professor

who wrote class emails

in verse form, with odd

line breaks in the middle

of the email.

VII. Related Terms

Verse is the opposite of prose: it’s the style of writing

that has line breaks.

Most commonly used in poetry, it tends to have rhythm and rhyme but doesn’t necessarily have these features. Anything with artistic line breaks counts as verse.

18 th -century authors saw poetry as a more elevated form of writing – it was a way of reaching for the mysterious and the heavenly. In contrast, prose was for writing about ordinary, everyday topics. As a result, the adjective “prosaic” (meaning prose-like) came to mean “ordinary, unremarkable.”

Prosody is the pleasing sound of words when they come together. Verse and prose can both benefit from having better prosody, since this makes the writing more enjoyable to a reader.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Definition of Prose

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it.

Common Examples of First Prose Lines in Well-Known Novels

The first prose line of a novel is significant for the writer and reader. This opening allows the writer to grab the attention of the reader, set the tone and style of the work, and establish elements of setting , character, point of view , and/or plot . For the reader, the first prose line of a novel can be memorable and inspire them to continue reading. Here are some common examples of first prose lines in well-known novels:

Examples of Famous Lines of Prose

Prose is a powerful literary device in that certain lines in literary works can have a great effect on readers in revealing human truths or resonating as art through language. Well-crafted, memorable prose evokes thought and feeling in readers. Here are some examples of famous lines of prose:

Types of Prose

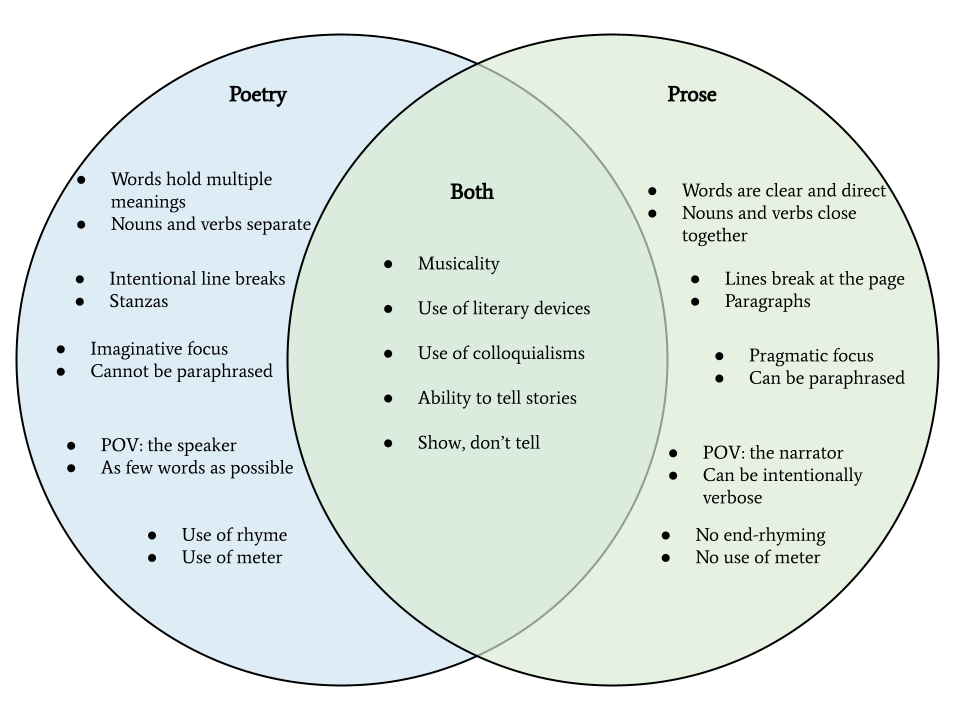

Difference between prose and poetry.

Many people consider prose and poetry to be opposites as literary devices . While that’s not quite the case, there are significant differences between them. Prose typically features natural patterns of speech and communication with grammatical structure in the form of sentences and paragraphs that continue across the lines of a page rather than breaking. In most instances, prose features everyday language.

Writing a Prose Poem

Prose edda vs. poetic edda, examples of prose in literature, example 1: the grapes of wrath by john steinbeck.

A large drop of sun lingered on the horizon and then dripped over and was gone, and the sky was brilliant over the spot where it had gone, and a torn cloud, like a bloody rag, hung over the spot of its going. And dusk crept over the sky from the eastern horizon, and darkness crept over the land from the east.

Example 2: This Is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams

I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold

Example 3: Harrison Bergeron by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

The year was 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

Synonyms of Prose

Post navigation.

Over 50% Off Writing Classes Today Only . Click Here To Visit The Store

- Short Stories

- Writing Tips

- Fantasy Writing

- Worldbuilding

- Writing Classes

- Writing Tools

- Progress Report

What Is Prose In Writing? Find A Definition And Examples

As a creative writing teacher, a common question I get asked is “what is prose?” The term prose simply refers to spoken or written language. In the context of writing books, it describes a style of written words, distinct from poetry, numbers and metrics.

One of the biggest tasks many writers face is improving their ability to write prose. This guide offers the quickest and easiest solutions.

Below, we take a look at the different styles of writing prose, examples of each one, and advice from expert writers on getting better.

You can jump to the section you’re most interested in below:

Choose A Chapter

What is prose writing an easy definition, what are the main styles of prose, orwellian prose: the clear pane of glass, florid prose: the stained glass window, can you use a hybrid approach, examples of different styles of prose, 13 tips to help you write clear prose, learn more about writing prose, frequently asked questions (faq), join an online writing community.

So what is prose ?

It’s spoken or written language that does not rhyme or contain numbers. How we think, speak and write would be described as prose. When we write prose, we often apply a grammatical structure.

How Are Prose And Poetry Different?

Prose and poetry are different because poetry applies a rhythmic structure whereas prose follows a more standard mode of written language that follows natural speech patterns—an example being this very article you’re reading now.

Prose and poetry are therefore considered opposites.

What Is Purple Prose In Writing?

Purple prose is when a writer uses too many fancy words or describes things in a flowery, exaggerated way. It’s like adding too much frosting on a cupcake; it might look pretty, but it’s too much and can make it hard to enjoy.

There are a few main styles of writing prose. They are:

- Clear, concise prose, referred to as ‘Orwellian’, or the ‘clear pane of glass’, and;

- Florid, literary prose, referred to as the ‘stained glass window’.

- A hybrid of the two, which is an approach I favour.

First, we’ll have a look at each, before looking at some examples.

If you’ve ever heard the phrase “good prose is like a window pane” and wanted to know the meaning behind it, here it is.

George Orwell in his essay, Politics and the English Language , set out what he thinks good prose writing ought to consist of, all the while attacking the British political system for the destruction of good writing practices.

Orwell was very much against the over-complication of language, which at the time (1946), was the direction politics was taking, and unfortunately still takes today.

Orwell believed prose should be like looking through a clear pane of glass at the story unfolding on the other side. It should be clear to understand. The writing should be invisible, drawing as little attention to itself as possible. The reader shouldn’t have to stop to re-read a sentence due to poor construction or stumble over a word used in the wrong way.

Words should be chosen because of their meaning, and to make them clearer, images or idioms, such as metaphors and similes, should be conjured. He encouraged the use of ‘newly invented metaphors’ which “assists thought by evoking a visual image”. Orwell encouraged writers to use the fewest and shortest words that will express the meaning you want.

“ Let the meaning choose the word.”

If you can’t explain something in short, simple terms, you don’t understand it, was his argument.

A change in the language used by politicians provoked Orwell to write his essay. Pretentious diction, as he called it—words such as phenomenon, element, objective, eliminate and liquidate—is used to dress up simple statements. He blamed politics for this, and how politicians adopt hollow words and phrases, mechanically repeating them over and over until they become meaningless.

I’m sure we can all agree we’re fed up of hearing such phrases. Orwell used ‘stand shoulder to shoulder’ as an example, and more recently we’ve seen Theresa May butcher the phrase ‘strong and stable’. These phrases are vague and bland and do not evoke any imagery, and if you’re a writer, they’re things you ought to avoid, Orwell argued.

Orwell’s Six Rules For Achieving Clear Prose

Orwell provided six rules to remember when writing prose. In following them, he argued, you could achieve clear prose that could be understood and enjoyed by all readers:

- Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print;

- Never use a long word where a short one will do;

- If it is possible to cut out a word, always cut it out;

- Never use the passive [voice] where you can use the active;

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent;

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

So in summary, Orwellian prose is writing which is short, simple and understandable. And if you’re looking for a simple and effective method of how to write good prose, this is it.

They’re great guidelines to test out with short stories. With that type of narrative writing you need to make every word count, so they’re a great way to get used to them. It’s also a more preferred prose form among many literary agents, publishers , and editors.

A Video Explainer On Orwellian Prose

If you’d like a more visual explainer on writing Orwellian prose, check out this brilliant video from bestselling author, Brandon Sanderson.

When we explore answers to the question, what is prose writing, one approach we inevitably turn to is the stained glass window—the antithesis to Orwell’s clear pane method.

With a stained glass window approach, you can still see the story on the other side, but the stained glass is colouring it in interesting ways. Language and structure are therefore florid and more creative. And it also tends to lean more heavily on the side of descriptive writing.

It’s used more in literary fiction and requires a mastery of language to pull off well. Brandon Sanderson refers to it as the artist’s style of prose, whereas Orwellian prose he regards as the craftsman’s style.

Above we mentioned the phrase ‘purple prose’. This is an attempt at creating a stained glass window, but the description and structure are poor , rendering the prose incomprehensible.

A blend of the clear pane and stained pane can work well. JRR Tolkien often adopted this, particularly with his descriptions, and other writers, Sanderson and David Gemmell to name but two, like to start chapters in a florid way before transitioning into the clear pane. Sometimes it can depend on the scene.

In fight scenes , for example, simple language is best adopted so the reader’s flow isn’t disrupted. When describing places, people or settings colourful language works well to liven up what would otherwise be quite mundane passages.

My personal preference is toward Orwellian prose writing. Writing should be clear and accessible to all. As writers, that’s what we want—to have our stories read and enjoyed by as many people as possible.

Having spent years working as a lawyer I know it’s not the case, and Orwell’s fears back in 1946 continue to materialise. In the end, I regarded my role as a lawyer as more of a translator of legal jargon. Writing shouldn’t be this way.

So we’ve taken a look at the different styles of prose writing. Now let’s take a look at some examples to better illustrate the different approaches.

Examples Of A Clear Prose Style

One of my favourite writers of clear prose is Ernest Hemingway. His stories are immersive and gripping because they’re simple to follow. A clear pane of glass approach if ever there was one.

Here’s an extract from Old Man And The Sea:

“He was happy feeling the gentle pulling and then he felt something hard and unbelievably heavy. It was the weight of the fish and he let the line slip down, down, down, unrolling off the first of the two reserve coils. As it went down, slipping lightly through the old man’s fingers, he still could feel the great weight, though the pressure of his thumb and finger were almost imperceptible.”

You can see here how clear the language is. “Imperceptible” may be the most difficult word used, but it almost doesn’t matter because what has come before it is so clear and vivid, we can picture the scene in our minds.

Examples Of Flowery Prose

On the other side of the coin, we have flowery prose. One of my favourite writers of florid prose is JRR Tolkien. Some people find The Lord Of The Rings quite challenging to read when they first begin, and I was one of them, and it’s down to Tolkien’s unqiue voice. But once you grow accustomed to it, there’s something quite enchanting about it.

So to illustrate this style, here’s an extract from The Lord of The Rings (Book One):

So far in this guide on how to write prose, we’ve looked at the different approaches. Now we’re looking at the practical side of things—how we actually write great prose. Here are a few writing tips to help you achieve a clear style :

- Resist the temptation to get fancy . We all do it. Only the other day I was going through a story of mine with a friend. I’d written the phrase “after thrice repeating the words,” and he pulled me up on it, and rightly so. “Why not just say ‘after the third time’?” he asked. Simpler, more effective.

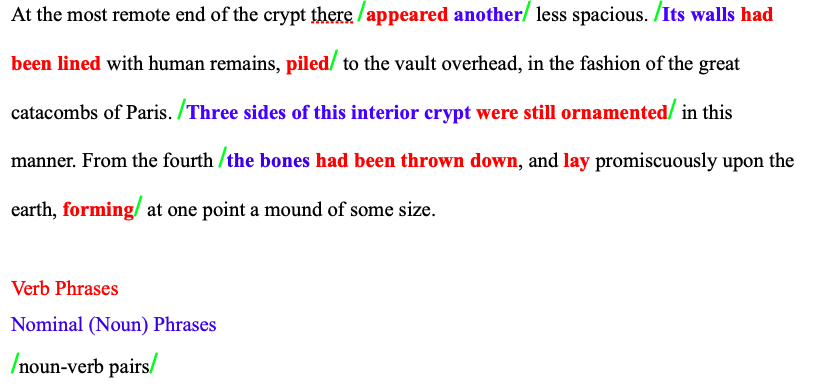

- Make good use of nouns and verbs, and refrain from indulging in adjectives and adverb s. Check out my 7 nifty editing tips which look at the impact too many adjectives and adverbs can have on your writing.

- Show don’t tell . This has cropped up a few times on the blog over the past few weeks, and for good reason. Telling the reader how a character feels is boring! Show it!

- Behead the passive voice . Seek to use active verbs. But this can be harder than it looks. Check out my full guide to passive voice here.

- Use effective dialogue. You can find dialogue writing examples here

- Try poetry and flash fiction . These facets of the craft will teach you the importance of each and every word. You’ll learn the power a single word can have, how it can provoke images, emotions or memories in the reader’s mind.

- Try using deliberate line breaks . Not only does this break up the wall of text to make it easier on the eye for the reader, it can help you emphasise key points as well as a structural device to build tension and suspense.

- Varying line lengths and sentence structure . This is a good one to help you build rhythm to your writing. Go back through your written prose and see how long each sentence is. If your sentences have similar strcutures, it can help to mix them up. Shorter sentences can help build suspense, longer sentences are useful for explanations and description. Keep this in mind as you go back through and edit, breaking up longer sentences into shorter ones or joining others together.

- Cut out extraneous words. Remove unnecessary words that balloon sentences. Let’s look at some prose writing examples:

He quickly crossed to the opposite side of the road.

He crossed the road.

Remember Orwell’s rule: if you can cut out a word, do it. When it comes to writing clear prose, less is more . That’s a good guideline to remember.

- Be specific and concrete . Seek to conjure vivid images and avoid vague phrases. Orwell provides a wonderful example from the book Ecclesiastes of how specificity can create vivid images:

“… The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet the bread to the wise, nor yet the riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill …”

- Pay attention to sentence structure, a.k.a. syntax. Sentences of a similar structure disrupt the flow and creates an awful rhythm. Short sentences increase the pace as well as tension, are effective at hitting home points, or signalling a change in tone. A short sentence I’d say is one less than half a line. Be warned: do not overuse them. A short sentence packs a punch, and you don’t want to bludgeon your reader. For an example of short sentences used well, check out Anna Smith Spark’s debut novel The Court of Broken Knives . Then come the medium-length sentences—one to two lines—which keeps the pace at a steady level. Anything over two lines and I’d say that’s a pretty long sentence. Long sentences are useful for pieces of description, slowing the pace or reducing tension. You can even be clever and use them to throw the reader off-guard. Watch out for your use of commas too and keep an eye on syllables. Read your work aloud to reveal these problems.

- Trust your reader . At some stage, we’ve all been guilty of holding the reader’s hand. Seek to create intrigue by withholding details.

- Avoid clichés and be mindful of tropes . It cheapens your writing and gives the reader the impression of laziness.

- What am I trying to say?

- What words will express it?

- What image or idiom (a group of words that establish a meaning that a single word cannot) will make it clearer?

- Is the image/idiom fresh enough to have an effect?

- Could I put it more shortly?

- Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

I’ve included a few other materials for you to further your reading.

Check out this English literature writing guide by the University of Edinburgh

If you’d like to study creative writing , check out this writing course offered by the University of East Anglia. If you’d like more resources like this, you can also check out my online writing classes .

To learn more about using the 5 senses in writing , which is a vital part of prose, check out this guide.

For some of the best tips around on writing a book for the first time , head here. You can find lots of brilliant advice for first time authors.

A great way to improve your prose is by writing short stories . Head here for a complete guide

Learn about sensory language examples here which can immensely improve your prose.

And head here for advice on when to rewrite your story .

And for more on character development and how to write a plot , head here.

Prose relates to ordinary everyday speech, so it’s arguably easier to write than poetry. However, many writers fall into the trap of writing ‘purple prose’, which is easy to write but not very good to read.

Prose carries with it no formal or set structure. It does, however, apply the general principles of grammar. It often reflects common or conversational speech.

Prose means the ordinary, everyday language that’s spoken or written. It is often distinguished from poetry due to its lack of a rhythmic structure.

In writing, prose relates to any form of written work in which the general rules of grammar and structure are followed. This is distinct from poetry, which follows a more rhythmic structure.

In the context of writing, prose refers to words assembled in a way that we wouldn’t otherwise describe as poetry or non-rthymic.

Written in prose simply means that a piece of text has been written down in a non-rhythmic way.

There are two main types of prose style—George Orwell’s the clear pane of glass, and on the opposite end of the spectrum, the stained glass window. Orwell believed in clear and simple, plain language. The stained glass window, on the other hand, opts for a more florid style.

Thank you for reading this guide on how to write prose. Hopefully, this post has shed light on the mysteries of prose and how you can achieve that clear, readable style.

If you’d like more help with your writing or would like to connect with like-minded writers, why not join my online writing community. There are hundreds of us all sharing advice, tips, calls for submissions, and helping each other out with our stories. We congregate on Facebook and Discord. To join, just click below.

If you need any more help with your prose writing, get in contact .

- Recent Posts

- How To Create A Theme For A Story - June 13, 2024

- A Guide To Siege Warfare And Tactics - June 12, 2024

- 15 Amazing Words To Describe The Moon, With Definitions And Example Sentences - May 22, 2024

richiebilling

About author, related posts, how to create a theme for a story, 15 amazing words to describe the moon, with definitions and example sentences, the best examples of the 5 senses and descriptive writing, 14 comments.

Reblogged this on Richie Billing and commented:

For my 50th post I thought I’d take a look back at the past 5 or so months at what I’ve thrown out into the world for your enjoyment. I was going to share the most popular post to date, but instead I’ve decided to share my personal favourite—the one that’s helped me the most in researching and writing it. So here it is, my guide to writing Orwellian prose.

Thank you to everyone who’s so far subscribed to this blog. It means a hell of a lot. In the months to come I’ll be looking to giveaway more free content and of course keep the articles coming. Here’s to the next 50!

Guess I”m more George Orwel than John Milton … 🙂 Just one thing (from a Jesuit-trained Old Xav with penchant for Latin grammar) The Passive voice gets a lot of ‘bad press’ which IMHO is often undeserved. You use an Active verb when you’re doing somehing. But you still need a Passive verb when someone is DOInG SOMETHING to you! Also: it’s almost impossible to write a grammatical French sentence without using a Reflexive verb. The Reflexive (s’asseoir, ‘to sit’ OR se plaire, ‘to please’) is a variation on Passive. They also use what in English grammar is called the subjunctive Mood, particularly in speech and even when Grammar insists that an Active verb is required … you can’t trust the French! LOL

- Pingback: Getting To Grips With Passive Voice – Richie Billing

- Pingback: What Is Passive Voice? – Richie Billing

- Pingback: The Magic Of Books | Celebrating World Book Day - Richie Billing

- Pingback: Great Examples Of The 5 Senses In Writing | Richie Billing

- Pingback: How To Edit A Novel - Richie Billing

- Pingback: How Do You Know When To Rewrite Your Story? - Richie Billing

- Pingback: The Ultimate Guide To Fantasy Armor - Richie Billing

- Pingback: What Is Foreshadowing In A Story? [With Examples] - Richie Billing

- Pingback: The Medieval Lord - The Complete Guide - Richie Billing

- Pingback: What makes good prose writing? And how does Brandon Sanderson’s prose compare – charzpov

- Pingback: The Best Show Don't Tell Examples For Writers - Richie Billing

- Pingback: 5 Easy Ways To Improve Your Writing Skills – Dutable

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Read my debut fantasy novel, Pariah’s Lament

Sign Up For Free Stories!

Email address

Read my guide to writing fantasy, A Fantasy Writers’ Handbook

A Guide To Siege Warfare And Tactics

Mastering dialogue: the very best tips, quick links.

- Get In Touch

- Reviews And Testimonials

- Editorial Policy

- Terms Of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Equality, Diversity And Inclusivity (EDI) Policy

- Affiliate Marketing Policy

- Payment Information

Follow On Social Media

Forgot your password?

Lost your password? Please enter your email address. You will receive mail with link to set new password.

Back to login

No thanks, close this box

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, definition of prose, common examples of prose, significance of prose in literature, examples of prose in literature.

I shall never be fool enough to turn knight-errant. For I see quite well that it’s not the fashion now to do as they did in the olden days when they say those famous knights roamed the world.

( Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes)

The ledge, where I placed my candle, had a few mildewed books piled up in one corner; and it was covered with writing scratched on the paint. This writing, however, was nothing but a name repeated in all kinds of characters, large and small—Catherine Earnshaw, here and there varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and then again to Catherine Linton. In vapid listlessness I leant my head against the window, and continued spelling over Catherine Earnshaw—Heathcliff—Linton, till my eyes closed; but they had not rested five minutes when a glare of white letters started from the dark, as vivid as spectres—the air swarmed with Catherines; and rousing myself to dispel the obtrusive name, I discovered my candle wick reclining on one of the antique volumes, and perfuming the place with an odour of roasted calf-skin.

( Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë)

“I never know you was so brave, Jim,” she went on comfortingly. “You is just like big mans; you wait for him lift his head and then you go for him. Ain’t you feel scared a bit? Now we take that snake home and show everybody. Nobody ain’t seen in this kawn-tree so big snake like you kill.”

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing, in fact he disliked it, but he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton.

( The Sun also Rises by Ernest Hemingway)

Ernest Hemingway wrote his prose in a very direct and straightforward manner. This excerpt from The Sun Also Rises demonstrates the directness in which he wrote–there is no subtlety to the narrator’s remark “Do not think I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title.”

The Lighthouse was then a silvery, misty-looking tower with a yellow eye, that opened suddenly, and softly in the evening. Now— James looked at the Lighthouse. He could see the white-washed rocks; the tower, stark and straight; he could see that it was barred with black and white; he could see windows in it; he could even see washing spread on the rocks to dry. So that was the Lighthouse, was it? No, the other was also the Lighthouse. For nothing was simply one thing. The other Lighthouse was true too.

And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking. . .ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: “It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish.”

Test Your Knowledge of Prose

1. Choose the best prose definition from the following statements: A. A form of communicating that uses ordinary grammar and flow. B. A piece of literature with a rhythmic structure. C. A synonym for verse. [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #1″] Answer: A is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove

A. It has a rhythmic structure. B. It contains rhymes. C. It does not use ordinary grammar. D. All of the above. [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #2″] Answer: D is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

You’re sad because you’re sad. It’s psychic. It’s the age. It’s chemical. Go see a shrink or take a pill, or hug your sadness like an eyeless doll you need to sleep.

“A Sad Child” B.

I would like to believe this is a story I’m telling. I need to believe it. I must believe it. Those who can believe that such stories are only stories have a better chance. If it’s a story I’m telling, then I have control over the ending. Then there will be an ending, to the story, and real life will come after it. I can pick up where I left off.

The Handmaid’s Tale C.

No, they whisper. You own nothing. You were a visitor, time after time climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming. We never belonged to you. You never found us. It was always the other way round.

“The Moment” [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #3″] Answer: B is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

paper-free learning

- conjunctions

- determiners

- interjections

- prepositions

- affect vs effect

- its vs it's

- your vs you're

- which vs that

- who vs whom

- who's vs whose

- averse vs adverse

- 250+ more...

- apostrophes

- quotation marks

- lots more...

- common writing errors

- FAQs by writers

- awkward plurals

- ESL vocabulary lists

- all our grammar videos

- idioms and proverbs

- Latin terms

- collective nouns for animals

- tattoo fails

- vocabulary categories

- most common verbs

- top 10 irregular verbs

- top 10 regular verbs

- top 10 spelling rules

- improve spelling

- common misspellings

- role-play scenarios

- favo(u)rite word lists

- multiple-choice test

- Tetris game

- grammar-themed memory game

- 100s more...

What Is Prose?

The Quick Answer

Table of Contents

The Difference between Prose and Poetry

The difference between prose and prosaic writing, examples of prose, why prose is important.

- I'm not lying when I say a dog is full of love. I know from experience that a wet dog loves you the most.

- The truth I do not stretch or shove When I state the dog is full of love. I've also proved, by actual test, A wet dog is the lovingest. (US poet Ogden Nash)

Anastrophe (deliberately using the wrong word order)

- A stare long and threatening

Assonance (repeating vowel sounds in nearby words)

- The concept of mothering more overtly

Consonance (repeating consonant sounds in nearby words)

- Pick a lock and crack it.

Deliberate repetition (deliberately repeating ideas or words)

- I shall tell you, and you shall listen, and we shall agree.

Euphemisms (using agreeable words to replace offensive ones)

- He was so well oiled he lost his lunch .

Logosglyphs (using words that look like what they represent)

- With eyes like pools

Metaphors (saying something is something else)

- The volcano spewed its flaming Earth sauce .

Onomatopoeia (using words that sound like what they represent)

- Don't growl at customers.

Oxymoron (using contradictory terms)

- Non-prosaic prose

Similes (describing something as being like something else)

- The British accepted her absence like Americans accept the missing full stop in "Dr Pepper".

- Use literary devices to create non-prosaic prose.

- Flair in prose is like salt in soup. None is usually fine. A little is often an improvement. A lot is always a disaster.

This page was written by Craig Shrives .

Learning Resources

more actions:

This test is printable and sendable

Help Us Improve Grammar Monster

- Do you disagree with something on this page?

- Did you spot a typo?

Find Us Quicker!

- When using a search engine (e.g., Google, Bing), you will find Grammar Monster quicker if you add #gm to your search term.

You might also like...

Share This Page

If you like Grammar Monster (or this page in particular), please link to it or share it with others. If you do, please tell us . It helps us a lot!

Create a QR Code

Use our handy widget to create a QR code for this page...or any page.

< previous lesson

next lesson >

What Is Prose?

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Prose is ordinary writing (both fiction and nonfiction ) as distinguished from verse. Most essays , compositions , reports , articles , research papers , short stories, and journal entries are types of prose writings.

In his book The Establishment of Modern English Prose (1998), Ian Robinson observed that the term prose is "surprisingly hard to define. . . . We shall return to the sense there may be in the old joke that prose is not verse."

In 1906, English philologist Henry Cecil Wyld suggested that the "best prose is never entirely remote in form from the best corresponding conversational style of the period" ( The Historical Study of the Mother Tongue ).

From the Latin, "forward" + "turn"

Observations

"I wish our clever young poets would remember my homely definitions of prose and poetry: that is, prose = words in their best order; poetry = the best words in the best order." (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Table Talk , July 12, 1827)

Philosophy Teacher: All that is not prose is verse; and all that is not verse is prose. M. Jourdain: What? When I say: "Nicole, bring me my slippers, and give me my night-cap," is that prose? Philosophy Teacher: Yes, sir. M. Jourdain: Good heavens! For more than 40 years I have been speaking prose without knowing it. (Molière, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme , 1671)

"For me, a page of good prose is where one hears the rain and the noise of battle. It has the power to give grief or universality that lends it a youthful beauty." (John Cheever, on accepting the National Medal for Literature, 1982)

" Prose is when all the lines except the last go on to the end. Poetry is when some of them fall short of it." (Jeremy Bentham, quoted by M. St. J. Packe in The Life of John Stuart Mill , 1954)

"You campaign in poetry. You govern in prose ." (Governor Mario Cuomo, New Republic , April 8, 1985)

Transparency in Prose

"[O]ne can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one's own personality. Good prose is like a window pane." (George Orwell, "Why I Write," 1946) "Our ideal prose , like our ideal typography, is transparent: if a reader doesn't notice it, if it provides a transparent window to the meaning, then the prose stylist has succeeded. But if your ideal prose is purely transparent, such transparency will be, by definition, hard to describe. You can't hit what you can't see. And what is transparent to you is often opaque to someone else. Such an ideal makes for a difficult pedagogy." (Richard Lanham, Analyzing Prose , 2nd ed. Continuum, 2003)

" Prose is the ordinary form of spoken or written language: it fulfills innumerable functions, and it can attain many different kinds of excellence. A well-argued legal judgment, a lucid scientific paper, a readily grasped set of technical instructions all represent triumphs of prose after their fashion. And quantity tells. Inspired prose may be as rare as great poetry--though I am inclined to doubt even that; but good prose is unquestionably far more common than good poetry. It is something you can come across every day: in a letter, in a newspaper, almost anywhere." (John Gross, Introduction to The New Oxford Book of English Prose . Oxford Univ. Press, 1998)

A Method of Prose Study

"Here is a method of prose study which I myself found the best critical practice I have ever had. A brilliant and courageous teacher whose lessons I enjoyed when I was a sixth-former trained me to study prose and verse critically not by setting down my comments but almost entirely by writing imitations of the style . Mere feeble imitation of the exact arrangement of words was not accepted; I had to produce passages that could be mistaken for the work of the author, that copied all the characteristics of the style but treated of some different subject. In order to do this at all it is necessary to make a very minute study of the style; I still think it was the best teaching I ever had. It has the added merit of giving an improved command of the English language and a greater variation in our own style." (Marjorie Boulton, The Anatomy of Prose . Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1954)

Pronunciation: PROZ

- Genres in Literature

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- Are Literature and Fiction the Same?

- An Introduction to Prose in Shakespeare

- Translation: Definition and Examples

- What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- Figure of Sound in Prose and Poetry

- Overview of Baroque Style in English Prose and Poetry

- Interior Monologues

- Everything You Need to Know About Shakespeare's Plays

- 12 Classic Essays on English Prose Style

- style (rhetoric and composition)

- Overview of Imagism in Poetry

- What You Need to Know About the Epic Poem 'Beowulf'

adjective or adverb

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of prose

(Entry 1 of 4)

Definition of prose (Entry 2 of 4)

Definition of prose (Entry 3 of 4)

intransitive verb

Definition of pro se (Entry 4 of 4)

Examples of prose in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'prose.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Noun, Adjective, and Verb

Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin prosa , from feminine of prorsus, prosus , straightforward, being in prose, contraction of proversus , past participle of provertere to turn forward, from pro- forward + vertere to turn — more at pro- , worth

Adjective or adverb

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Adjective Or Adverb

1861, in the meaning defined above

Phrases Containing prose

- polyphonic prose

Articles Related to prose

Poetic Forms: 13 Ways of Looking at a...

Poetic Forms: 13 Ways of Looking at a Poem

Sestina, anyone?

Dictionary Entries Near prose

Cite this entry.

“Prose.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/prose. Accessed 23 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of prose, legal definition, legal definition of pro se.

Adverb or adjective

More from Merriam-Webster on prose

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for prose

Nglish: Translation of prose for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of prose for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, more commonly misspelled words, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, birds say the darndest things, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), games & quizzes.

Prose vs Essay - What's the difference?

As nouns the difference between prose and essay, as verbs the difference between prose and essay, derived terms, related terms.

What is Prose? Definition, Examples of Literary Prose

Prose is a form of written language that does not have a formal meter structure. Prose more closely mimics normal patterns of speech.

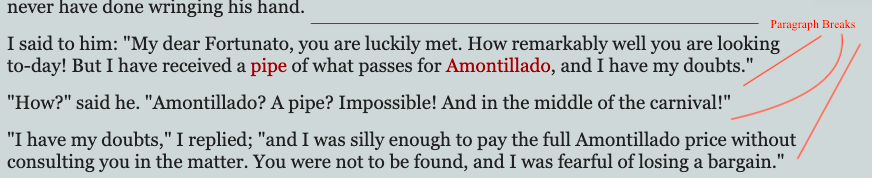

What is Prose?

Prose is a style of writing that does not follow a strict structure of rhyming and/or meter. Prose uses normal grammatical structures. Elements of prose writing include regular grammar and paragraph structures that organize ideas, forgoing more stylistic and aesthetic forms of writing found in poetry and lyrics.

Prose can include normal dialogue, speeches, novels, news reports, etc. Prose is distinguished from poetry which uses line breaks and has meter that tends to defy normal grammar rules.

In today’s literature, most stories are told in prose. There is no longer much emphasis on the oral tradition of storytelling, to which verse was very well suited. Since print came to be commonplace, storytellers tend to rely on prose to tell their stories because of the freedom it allows.

Different Types of Prose

There are different genres of writing that use prose style. Here are a few:

Nonfiction Prose

Nonfiction is a work of writing that is based on fact. Examples of nonfiction include memoirs, essays, instructions, biographies, etc.

Fiction Prose

Fiction is a genre of writing that is imagined or untrue. Novels use prose in order to tell stories. Subgenres of fiction can include fantasy, historical fiction, science fiction, etc.

Heroic Prose

Heroic prose uses the hero archetype in order to tell stories of bravery and travel in which good triumphs over evil. These stories are meant to be recited orally. Heroic prose may use tricks such as rhyme and a slight rhythmic structure in order to enhance the effects of being read out loud but are not the same as the ancient hero tales which were written in strict poetic verse.

Prose Poetry

Prose poetry uses certain poetic qualities in order to add a lyrical or aesthetic value to the writing. However, it stops short of any regular or strict metered form. This style of writing creates bolder emotional effects and often relies on metaphors and imagery in order to create similar reactions in readers that poetry would, while still maintaining the prose style.

The Function of Prose

Prose provides a loose structure for writers which offers freedom and creativity in expression. With prose, a writer can be as imaginative and creative as they want—or they can write very dryly in order to convey a specific point. It all comes down to the writer’s purpose and intended effect. With prose, the sky is the limit.

Ultimately, prose is an efficient way to write and convey ideas. There is a reason why news reporters and journalists write in prose—they can clearly express details, key facts, and updates in a way that is accessible to all. If everything was written in poetry/verse, there might be some conflicts in how news and important messages were spread.

Examples of Prose in Literature

In fiction, prose can be manipulated in order to create very specific stylistic effects. For example, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights tends to use long, winding sentence structures in order to convey the tendency to become obsessive, which is a trait found in several characters.

This writing, however, was nothing but a name repeated in all kinds of characters, large and small—Catherine Earnshaw, here and there varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and then again to Catherine Linton. In vapid listlessness I leant my head against the window, and continued spelling over Catherine Earnshaw—Heathcliff—Linton, till my eyes closed; but they had not rested five minutes when a glare of white letters started from the dark, as vivid as spectres—the air swarmed with Catherines; and rousing myself to dispel the obtrustive name, I discovered my candle wick reclining on one of the antique volumes, and perfuming the place with an odour of roasted calf-skin.

Speeches are another place where prose is used to convey ideas. Consider the “No Easy Walk to Freedom” Speech by Nelson Mandela :

You can see that there is no easy walk to freedom anywhere, and many of us will have to pass through the valley of the shadow again and again before we reach the mountain tops of our desires.

Essays are also written in prose. The philosopher Sir Francis Bacon , who influenced founders of the American colonies, wrote the essay “On Nobility” in which he speaks on nobility in government.

For nobility attempers sovereignty, and draws the eyes of the people, somewhat aside from the line royal. But for democracies, they need it not; and they are commonly more quiet, and less subject to sedition, than where there are stirps of nobles. For men’s eyes are upon the business, and not upon the persons; or if upon the persons, it is for the business’ sake, as fittest, and not for flags and pedigree.

Recap: What is Prose in Literature?

Prose is the style of writing that does not use a metered format like poetry does. It more closely resembles normal patterns of speech, with normal grammatical structures such as full sentences and paragraphs.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay + Example

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered

What is the ap lit prose essay, how will ap scores affect my college chances.

AP Literature and Composition (AP Lit), not to be confused with AP English Language and Composition (AP Lang), teaches students how to develop the ability to critically read and analyze literary texts. These texts include poetry, prose, and drama. Analysis is an essential component of this course and critical for the educational development of all students when it comes to college preparation. In this course, you can expect to see an added difficulty of texts and concepts, similar to the material one would see in a college literature course.

While not as popular as AP Lang, over 380,136 students took the class in 2019. However, the course is significantly more challenging, with only 49.7% of students receiving a score of three or higher on the exam. A staggeringly low 6.2% of students received a five on the exam.

The AP Lit exam is similar to the AP Lang exam in format, but covers different subject areas. The first section is multiple-choice questions based on five short passages. There are 55 questions to be answered in 1 hour. The passages will include at least two prose fiction passages and two poetry passages and will account for 45% of your total score. All possible answer choices can be found within the text, so you don’t need to come into the exam with prior knowledge of the passages to understand the work.

The second section contains three free-response essays to be finished in under two hours. This section accounts for 55% of the final score and includes three essay questions: the poetry analysis essay, the prose analysis essay, and the thematic analysis essay. Typically, a five-paragraph format will suffice for this type of writing. These essays are scored holistically from one to six points.

Today we will take a look at the AP Lit prose essay and discuss tips and tricks to master this section of the exam. We will also provide an example of a well-written essay for review.

The AP Lit prose essay is the second of the three essays included in the free-response section of the AP Lit exam, lasting around 40 minutes in total. A prose passage of approximately 500 to 700 words and a prompt will be given to guide your analytical essay. Worth about 18% of your total grade, the essay will be graded out of six points depending on the quality of your thesis (0-1 points), evidence and commentary (0-4 points), and sophistication (0-1 points).

While this exam seems extremely overwhelming, considering there are a total of three free-response essays to complete, with proper time management and practiced skills, this essay is manageable and straightforward. In order to enhance the time management aspect of the test to the best of your ability, it is essential to understand the following six key concepts.

1. Have a Clear Understanding of the Prompt and the Passage

Since the prose essay is testing your ability to analyze literature and construct an evidence-based argument, the most important thing you can do is make sure you understand the passage. That being said, you only have about 40 minutes for the whole essay so you can’t spend too much time reading the passage. Allot yourself 5-7 minutes to read the prompt and the passage and then another 3-5 minutes to plan your response.

As you read through the prompt and text, highlight, circle, and markup anything that stands out to you. Specifically, try to find lines in the passage that could bolster your argument since you will need to include in-text citations from the passage in your essay. Even if you don’t know exactly what your argument might be, it’s still helpful to have a variety of quotes to use depending on what direction you take your essay, so take note of whatever strikes you as important. Taking the time to annotate as you read will save you a lot of time later on because you won’t need to reread the passage to find examples when you are in the middle of writing.

Once you have a good grasp on the passage and a solid array of quotes to choose from, you should develop a rough outline of your essay. The prompt will provide 4-5 bullets that remind you of what to include in your essay, so you can use these to structure your outline. Start with a thesis, come up with 2-3 concrete claims to support your thesis, back up each claim with 1-2 pieces of evidence from the text, and write a brief explanation of how the evidence supports the claim.

2. Start with a Brief Introduction that Includes a Clear Thesis Statement

Having a strong thesis can help you stay focused and avoid tangents while writing. By deciding the relevant information you want to hit upon in your essay up front, you can prevent wasting precious time later on. Clear theses are also important for the reader because they direct their focus to your essential arguments.

In other words, it’s important to make the introduction brief and compact so your thesis statement shines through. The introduction should include details from the passage, like the author and title, but don’t waste too much time with extraneous details. Get to the heart of your essay as quick as possible.

3. Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument

One of the requirements AP Lit readers are looking for is your use of evidence. In order to satisfy this aspect of the rubric, you should make sure each body paragraph has at least 1-2 pieces of evidence, directly from the text, that relate to the claim that paragraph is making. Since the prose essay tests your ability to recognize and analyze literary elements and techniques, it’s often better to include smaller quotes. For example, when writing about the author’s use of imagery or diction you might pick out specific words and quote each word separately rather than quoting a large block of text. Smaller quotes clarify exactly what stood out to you so your reader can better understand what are you saying.

Including smaller quotes also allows you to include more evidence in your essay. Be careful though—having more quotes is not necessarily better! You will showcase your strength as a writer not by the number of quotes you manage to jam into a paragraph, but by the relevance of the quotes to your argument and explanation you provide. If the details don’t connect, they are merely just strings of details.

4. Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Evidence to Your Argument

As the previous tip explained, citing phrases and words from the passage won’t get you anywhere if you don’t provide an explanation as to how your examples support the claim you are making. After each new piece of evidence is introduced, you should have a sentence or two that explains the significance of this quote to the piece as a whole.

This part of the paragraph is the “So what?” You’ve already stated the point you are trying to get across in the topic sentence and shared the examples from the text, so now show the reader why or how this quote demonstrates an effective use of a literary technique by the author. Sometimes students can get bogged down by the discussion and lose sight of the point they are trying to make. If this happens to you while writing, take a step back and ask yourself “Why did I include this quote? What does it contribute to the piece as a whole?” Write down your answer and you will be good to go.

5. Write a Brief Conclusion

While the critical part of the essay is to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs, a conclusion provides a satisfying ending to the essay and the last opportunity to drive home your argument. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of extra time spent in the preceding paragraphs, do not worry, as that is not fatal to your score.

Without repeating your thesis statement word for word, find a way to return to the thesis statement by summing up your main points. This recap reinforces the arguments stated in the previous paragraphs, while all of the preceding paragraphs successfully proved the thesis statement.

6. Don’t Forget About Your Grammar

Though you will undoubtedly be pressed for time, it’s still important your essay is well-written with correct punctuating and spelling. Many students are able to write a strong thesis and include good evidence and commentary, but the final point on the rubric is for sophistication. This criteria is more holistic than the former ones which means you should have elevated thoughts and writing—no grammatical errors. While a lack of grammatical mistakes alone won’t earn you the sophistication point, it will leave the reader with a more favorable impression of you.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

[amp-cta id="9459"]

Here are Nine Must-have Tips and Tricks to Get a Good Score on the Prose Essay:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key instruction s in the prompt.

- Briefly outlin e what you want to cover in your essay.

- Be sure to have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title in your introduction. Refer to characters by name.

- Quality over quantity when it comes to picking quotes! Better to have a smaller number of more detailed quotes than a large amount of vague ones.

- Fully explain how each piece of evidence supports your thesis .

- Focus on the literary techniques in the passage and avoid summarizing the plot.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

Here is an example essay from 2020 that received a perfect 6:

[1] In this passage from a 1912 novel, the narrator wistfully details his childhood crush on a girl violinist. Through a motif of the allure of musical instruments, and abundant sensory details that summon a vivid image of the event of their meeting, the reader can infer that the narrator was utterly enraptured by his obsession in the moment, and upon later reflection cannot help but feel a combination of amusement and a resummoning of the moment’s passion.

[2] The overwhelming abundance of hyper-specific sensory details reveals to the reader that meeting his crush must have been an intensely powerful experience to create such a vivid memory. The narrator can picture the “half-dim church”, can hear the “clear wail” of the girl’s violin, can see “her eyes almost closing”, can smell a “faint but distinct fragrance.” Clearly, this moment of discovery was very impactful on the boy, because even later he can remember the experience in minute detail. However, these details may also not be entirely faithful to the original experience; they all possess a somewhat mysterious quality that shows how the narrator may be employing hyperbole to accentuate the girl’s allure. The church is “half-dim”, the eyes “almost closing” – all the details are held within an ethereal state of halfway, which also serves to emphasize that this is all told through memory. The first paragraph also introduces the central conciet of music. The narrator was drawn to the “tones she called forth” from her violin and wanted desperately to play her “accompaniment.” This serves the double role of sensory imagery (with the added effect of music being a powerful aural image) and metaphor, as the accompaniment stands in for the narrator’s true desire to be coupled with his newfound crush. The musical juxtaposition between the “heaving tremor of the organ” and the “clear wail” of her violin serves to further accentuate how the narrator percieved the girl as above all other things, as high as an angel. Clearly, the memory of his meeting his crush is a powerful one that left an indelible impact on the narrator.

[3] Upon reflecting on this memory and the period of obsession that followed, the narrator cannot help but feel amused at the lengths to which his younger self would go; this is communicated to the reader with some playful irony and bemused yet earnest tone. The narrator claims to have made his “first and last attempts at poetry” in devotion to his crush, and jokes that he did not know to be “ashamed” at the quality of his poetry. This playful tone pokes fun at his childhood self for being an inexperienced poet, yet also acknowledges the very real passion that the poetry stemmed from. The narrator goes on to mention his “successful” endeavor to conceal his crush from his friends and the girl; this holds an ironic tone because the narrator immediately admits that his attempts to hide it were ill-fated and all parties were very aware of his feelings. The narrator also recalls his younger self jumping to hyperbolic extremes when imagining what he would do if betrayed by his love, calling her a “heartless jade” to ironically play along with the memory. Despite all this irony, the narrator does also truly comprehend the depths of his past self’s infatuation and finds it moving. The narrator begins the second paragraph with a sentence that moves urgently, emphasizing the myriad ways the boy was obsessed. He also remarks, somewhat wistfully, that the experience of having this crush “moved [him] to a degree which now [he] can hardly think of as possible.” Clearly, upon reflection the narrator feels a combination of amusement at the silliness of his former self and wistful respect for the emotion that the crush stirred within him.

[4] In this passage, the narrator has a multifaceted emotional response while remembering an experience that was very impactful on him. The meaning of the work is that when we look back on our memories (especially those of intense passion), added perspective can modify or augment how those experiences make us feel

More essay examples, score sheets, and commentaries can be found at College Board .

While AP Scores help to boost your weighted GPA, or give you the option to get college credit, AP Scores don’t have a strong effect on your admissions chances . However, colleges can still see your self-reported scores, so you might not want to automatically send scores to colleges if they are lower than a 3. That being said, admissions officers care far more about your grade in an AP class than your score on the exam.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Scriptwriting

What is Prose — Definition and Examples in Literature

- What is a Poem

- What is a Stanza in a Poem

- What is Dissonance

- What is a Sonnet

- What is a Haiku

- What is Prose

- What is an Ode

- What is Repetition in Poetry

- How to Write a Poem

- Types of Poems Guide

- What is an Acrostic Poem

- What is an Epic Poem

- What is Lyric Poetry

P rose can be a rather general literary term that many use to describe all types of writing. However, prose by definition pertains to specific qualities of writing that we will dive into in this article. What is the difference between prose and poetry and what is prose used for? Let’s define this essential literary concept and look at some examples to find out.

What is Prose in Literature?

First, let’s define prose.

Prose is used in various ways for various purposes. It's a concept you need to understand if your goal to master the literary form. Before we dive in, it’s important to understand the prose definition and how it is distinguished from other styles of writing.

PROSE DEFINITION

What is prose.

In writing, prose is a style used that does not follow a structure of rhyming or meter. Rather, prose follows a grammatical structure using words to compose phrases that are arranged into sentences and paragraphs. It is used to directly communicate concepts, ideas, and stories to a reader. Prose follows an almost naturally verbal flow of writing that is most common among fictional and non-fictional literature such as novels, magazines, and journals.

Four types of prose:

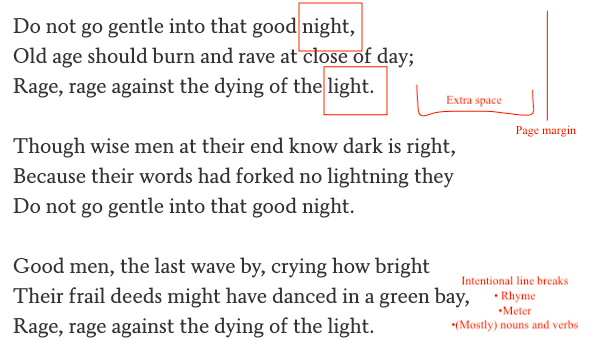

Nonfictional prose, fictional prose, prose poetry, heroic prose, prose meaning , prose vs poetry.

To better understand prose, it’s important to understand what structures it does not follow which would be the structure of poetry. Let’s analyze the difference between prose vs poetry.

Poetry follows a specific rhyme and metric structure. These are often lines and stanzas within a poem. Poetry also utilizes more figurative and often ambiguous language that purposefully leaves room for the readers’ analysis and interpretation.

Finally, poetry plays with space on a page. Intentional line breaks, negative space, and varying line lengths make poetry a more aesthetic form of writing than prose.

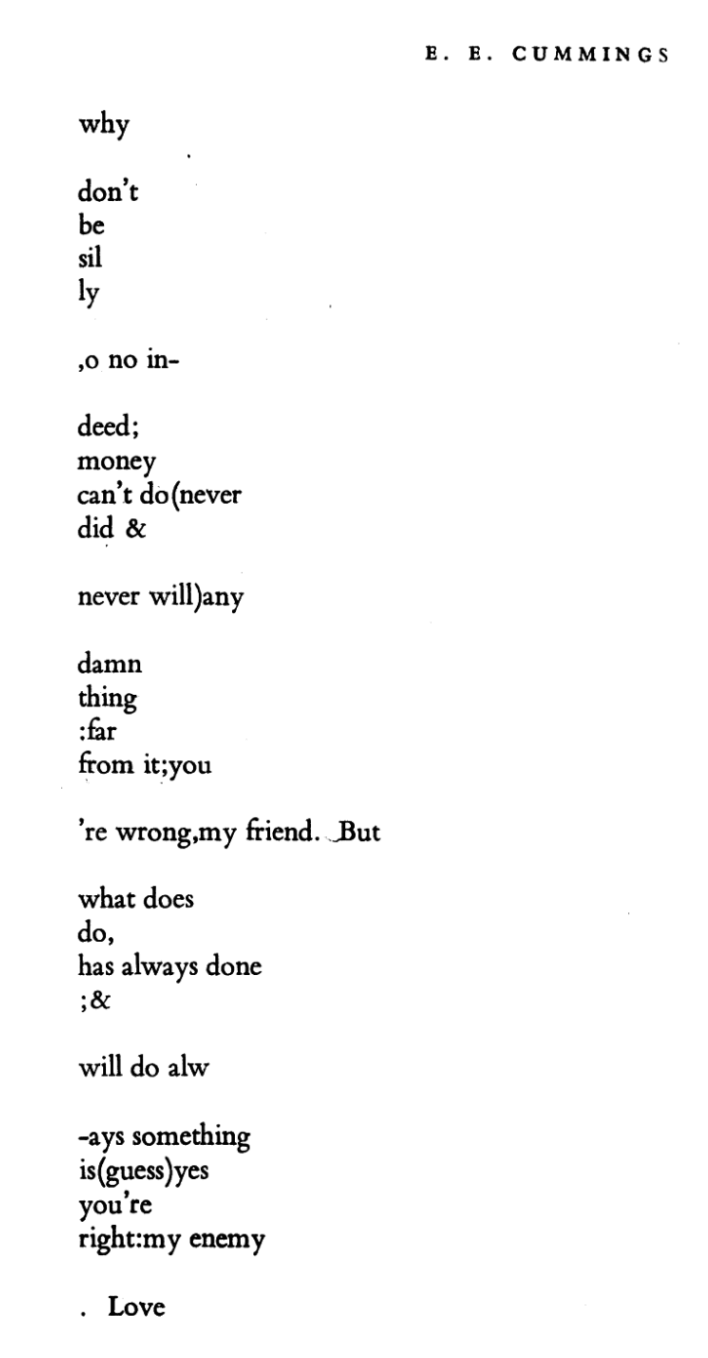

Take, for example, the structure of this [Why] by E.E. Cummings. Observe his use of space and aesthetics as well as metric structure in the poem.

E.E. Cummings Poem

E.E. Cummings may be one of the more stylish poets when it comes to use of page space. But poetry is difference in structure and practice than prose.

Prose follows a structure that makes use of sentences, phrases, and paragraphs. This type of writing follows a flow more similar to verbal speech and communication. This makes it the best style of writing to clearly articulate and communicate concepts, events, stories, and ideas as opposed to the figurative style of poetry.

What is Prose in Literature?

Take, for example, the opening paragraph of JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye . We can tell immediately the prose is written in a direct, literal way that also gives voice to our protagonist .

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

From this example, you can see how the words flow more conversationally than poetry and is more direct with what information or meaning is being communicated. Now that you understand the difference between poetry, let’s look at the four types of prose.

Related Posts

- What is Litotes — Definition and Examples →

- Different Types of Poems and Poem Structures →

- What is Iambic Pentameter? Definition and Examples →

Prose Examples

Types of prose.

While all four types of prose adhere to the definition we established, writers use the writing style for different purposes. These varying purposes can be categorized into four different types.

Nonfictional prose is a body of writing that is based on factual and true events. The information is not created from a writer’s imagination, but rather true accounts of real events.

This type can be found in newspapers, magazines, journals, biographies, and textbooks. Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl , for example, is a work written in nonfictional style.

Unlike nonfictional, fictional prose is partly or wholly created from a writer’s imagination. The events, characters, and story are imagined such as Romeo and Juliet , The Adventures of Tom Sawyer , or Brave New World . This type is found as novels, short stories, or novellas .

Heroic prose is a work of writing that is meant to be recited and passed on through oral or written tradition. Legends, mythology, fables, and parables are examples of heroic prose that have been passed on over time in preservation.

Finally, prose poetry is poetry that is expressed and written in prose form. This can be thought of almost as a hybrid of the two that can sometimes utilize rhythmic measures. This type of poetry often utilizes more figurative language but is usually written in paragraph form.

An example of prose poetry is “Spring Day” by Amy Lowell. Lowell, an American poet, published this in 1916 and can be read almost as hyper short stories written in a prose poetry style.

The first section can be read below:

The day is fresh-washed and fair, and there is a smell of tulips and narcissus in the air.

The sunshine pours in at the bath-room window and bores through the water in the bath-tub in lathes and planes of greenish-white. It cleaves the water into flaws like a jewel, and cracks it to bright light.

Little spots of sunshine lie on the surface of the water and dance, dance, and their reflections wobble deliciously over the ceiling; a stir of my finger sets them whirring, reeling. I move a foot, and the planes of light in the water jar. I lie back and laugh, and let the green-white water, the sun-flawed beryl water, flow over me. The day is almost too bright to bear, the green water covers me from the too bright day. I will lie here awhile and play with the water and the sun spots.

The sky is blue and high. A crow flaps by the window, and there is a whiff of tulips and narcissus in the air."

While these four types of prose are varying ways writers choose to use it, let’s look at the functions of them to identify the strengths of the writing style.

What Does Prose Mean in Writing

Function of prose in literature.

What is prose used for and when? Let’s say you want to tell a story, but you’re unsure if using prose or poetry would best tell your story.

To determine if the correct choice is prose, it’s important to understand the strengths of the writing style.

Direct communication

Prose, unlike poetry, is often less figurative and ambiguous. This means that a writer can be more direct with the information they are trying to communicate. This can be especially useful in storytelling, both fiction and nonfiction, to efficiently fulfill the points of a plot.

Curate a voice

Because prose is written in the flow of verbal conversation, it’s incredibly effective at curating a specific voice for a character. Dialogue within novels and short stories benefit from this style.

Think about someone you know and how they talk. Odds are, much of their character and personality can be found in their voice.

When creating characters, prose enables a writer to curate the voice of that character. For example, one of the most iconic opening lines in literature informs us of what type of character we will be following.

Albert Camus’ The Stranger utilizes prose in first person to establish the voice of the story’s protagonist.

“Mother died today. Or, maybe, yesterday; I can’t be sure. The telegram from the Home says: YOUR MOTHER PASSED AWAY. FUNERAL TOMORROW. DEEP SYMPATHY. Which leaves the matter doubtful; it could have been yesterday.”

Build rapport with the reader

Lastly, in addition to giving character’s a curated voice, prose builds rapport with the reader. The conversational tone allows readers to become familiar with a type of writing that connects them with the writer.

A great example of this is Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels . As a nonfiction work written in prose, Thompson’s voice and style in the writing is distinct and demands a relationship with the reader.

Whether it is one of contradiction or agreement, the connection exists through the prose. It is a connection that makes a reader want to meet or talk with the writer once they finish their work.

Prose is one of the most common writing styles for modern writers. But truly mastering it means understanding both its strengths and its shortcomings.

Different Types of Poems

Curious about learning about the counterpart to prose? In our next article we dive in different types of poems as well as different types of poem structures. Check out the complete writer’s guide to poetry types up next.

Up Next: Types of Poems →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Dramatic Irony? Definition and Examples

- What is Situational Irony? Definition and Examples

- What is Verbal Irony? Definition and Examples

- How to Create Script Sides for Film & TV [with Examples]

- 1 Pinterest

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, writing a prose essay.

I've got an assignment to write a prose essay, but I'm not exactly sure what that means. Can any of you help me understand the definition of a prose essay and maybe some tips on how to write one?

A prose essay is a type of essay written in prose, which is a natural, flowing form of language, as opposed to verse or poetry. Essentially, when you're asked to write a prose essay, you're being asked to write an essay in complete sentences, organized into paragraphs, that clearly communicates your thoughts and ideas.

To write a prose essay, follow these steps:

1. Understand the prompt: Read the essay prompt or question carefully and make sure you fully comprehend what is being asked of you. Ask your teacher if you're unclear about what the point of the question is.

2. Brainstorm and outline: Jot down your thoughts and ideas related to the prompt and begin organizing them into a logical structure. Create an outline to serve as the framework for your essay, with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.