50 Verbs of Analysis for English Academic Essays

Note: this list is for advanced English learners (CEFR level B2 or above). All definitions are from the Cambridge Dictionary online .

Definition: to have an influence on someone or something, or to cause a change in someone or something.

Example: Experts agree that coffee affects the body in ways we have not yet studied.

Definition: to increase the size or effect of something.

Example: It has been shown that this drug amplifies the side effects that were experienced by patients in previous trials.

Definition: to say that something is certainly true .

Example: Smith asserts that his findings are valid, despite criticism by colleagues.

Characterizes

Definition: Something that characterizes another thing is typical of it.

Example: His early paintings are characterized by a distinctive pattern of blue and yellow.

Definition: to say that something is true or is a fact , although you cannot prove it and other people might not believe it.

Example: Smith claims that the study is the first of its kind, and very different from the 2015 study he conducted.

Definition: to make something clear or easier to understand by giving more details or a simpler explanation .

Example: The professor clarified her statement with a later, more detailed, statement.

Definition: t o collect information from different places and arrange it in a book , report , or list .

Example: After compiling the data, the scientists authored a ten-page paper on their study and its findings.

Definition: to judge or decide something after thinking carefully about it.

Example: Doctor Jensen concluded that the drug wasn’t working, so he switched his patient to a new medicine.

Definition: to prove that a belief or an opinion that was previously not completely certain is true .

Example: This new data confirms the hypothesis many researchers had.

Definition: to join or be joined with something else .

Example: By including the criticisms of two researchers, Smith connects two seemingly different theories and illustrates a trend with writers of the Romanticism period.

Differentiates

Definition: to show or find the difference between things that are compared .

Example: Smith differentiates between the two theories in paragraph 4 of the second part of the study.

Definition: to reduce or be reduced in s i ze or importance .

Example: The new findings do not diminish the findings of previous research; rather, it builds on it to present a more complicated theory about the effects of global warming.

Definition: to cause people to stop respecting someone or believing in an idea or person .

Example: The details about the improper research done by the institution discredits the institution’s newest research.

Definition: to show.

Example: Smith’s findings display the effects of global warming that have not yet been considered by other scientists.

Definition: to prove that something is not true .

Example: Scientists hope that this new research will disprove the myth that vaccines are harmful to children.

Distinguishes

Definition: to notice or understand the difference between two things, or to make one person or thing seem different from another.

Example: Our study seems similar to another one by Duke University: how can we distinguish ourselves and our research from this study?

Definition: to add more information to or explain something that you have said.

Example: In this new paper, Smith elaborates on theories she discussed in her 2012 book.

Definition: to represent a quality or an idea exactly .

Example: Shakespeare embodies English theater, but few can understand the antiquated (old) form of English that is used in the plays.

Definition: to copy something achieved by someone else and try to do it as well as they have.

Example: Although the study emulates some of the scientific methods used in previous research, it also offers some inventive new research methods.

Definition: to improve the quality , amount , or strength of something.

Example: The pharmaceutical company is looking for ways to enhance the effectiveness of its current drug for depression.

Definition: to make something necessary , or to involve something.

Example: The scientist’s study entails several different stages, which are detailed in the report.

Definition: to consider one thing to be the same as or equal to another thing.

Example: Findings from both studies equate; therefore, we can conclude that they are both accurate.

Establishes

Definition: to discover or get proof of something.

Example: The award establishes the main causes of global warming.

Definition: to make someone remember something or feel an emotion .

Example: The artist’s painting evokes the work of some of the painters from the early 1800s.

Definition: to show something.

Example: Some of the research study participants exhibit similar symptoms while taking the medicine.

Facilitates

Definition: to make something possible or easier .

Example: The equipment that facilitates the study is expensive and of high-quality.

Definition: the main or central point of something, especially of attention or interest .

Example: The author focuses on World War II, which is an era she hasn’t written about before.

Foreshadows

Definition: to act as a warning or sign of a future event .

Example: The sick bird at the beginning of the novel foreshadows the illness the main character develops later in the book.

Definition: to develop all the details of a plan for doing something.

Example: Two teams of scientists formulated the research methods for the study.

Definition: to cause something to exist .

Example: The study’s findings have generated many questions about this new species of frog in South America.

Definition: to attract attention to or emphasize something important .

Example: The author, Dr. Smith, highlights the need for further studies on the possible causes of cancer among farm workers.

Definition: to recognize a problem , need, fact , etc. and to show that it exists .

Example: Through this study, scientists were able to identify three of the main factors causing global warming.

Illustrates

Definition: to show the meaning or truth of something more clearly , especially by giving examples .

Example: Dr. Robin’s study illustrates the need for more research on the effects of this experimental drug.

Definition: to communicate an idea or feeling without saying it directly .

Example: The study implies that there are many outside factors (other than diet and exercise) which determine a person’s tendency to gain weight.

Incorporates

Definition: to include something as part of something larger .

Example: Dr. Smith incorporates research findings from 15 other studies in her well-researched paper.

Definition: to show, point , or make clear in another way.

Example: Overall, the study indicates that there is no real danger (other than a lack of sleep) to drinking three cups of coffee per day.

Definition: to form an opinion or guess that something is true because of the information that you have.

Example: From this study about a new medicine, we can infer that it will work similarly to other drugs that are currently being sold.

Definition: to tell someone about parti c ular facts .

Example: Dr. Smith informs the reader that there are some issues with this study: the oddly rainy weather in 2017 made it difficult for them to record the movements of the birds they were studying.

Definition: to suggest , without being direct , that something unpleasant is true .

Example: In addition to the reported conclusions, the study insinuates that there are many hidden dangers to driving while texting.

Definition: to combine two or more things in order to become more effective .

Example: The study about the popularity of social media integrates Facebook and Instagram hashtag use.

Definition: to not have or not have enough of something that is needed or wanted .

Example: What the study lacks, I believe, is a clear outline of the future research that is needed.

Legitimizes

Definition: to make something legal or acceptable .

Example: Although the study legitimizes the existence of global warming, some will continue to think it is a hoax.

Definition: to make a problem bigger or more important .

Example: In conclusion, the scientists determined that the new pharmaceutical actually magnifies some of the symptoms of anxiety.

Definition: something that a copy can be based on because it is an extremely good example of its type .

Example: The study models a similar one from 1973, which needed to be redone with modern equipment.

Definition: to cause something to have no effect .

Example: This negates previous findings that say that sulphur in wine gives people headaches.

Definition: to not give enough c a re or attention to people or things that are your responsibility .

Example: The study neglects to mention another study in 2015 that had very different findings.

Definition: to make something difficult to discover and understand .

Example: The problems with the equipment obscures the study.

Definition: a description of the main facts about something.

Example: Before describing the research methods, the researchers outline the need for a study on the effects of anti-anxiety medication on children.

Definition: to fail to notice or consider something or someone.

Example: I personally feel that the study overlooks something very important: the participants might have answered some of the questions incorrectly.

Definition: to happen at the same time as something else , or be similar or equal to something else .

Example: Although the study parallels the procedures of a 2010 study, it has very different findings.

Converse International School of Languages offers an English for Academic Purposes course for students interested in improving their academic English skills. Students may take this course, which is offered in the afternoon for 12 weeks, at both CISL San Diego and CISL San Francisco . EAP course graduates can go on to CISL’s Aca demic Year Abroad program, where students attend one semester at a California Community College. Through CISL’s University Pathway program, EAP graduates may also attend college or university at one of CISL’s Pathway Partners. See the list of 25+ partners on the CISL website . Contact CISL for more information.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

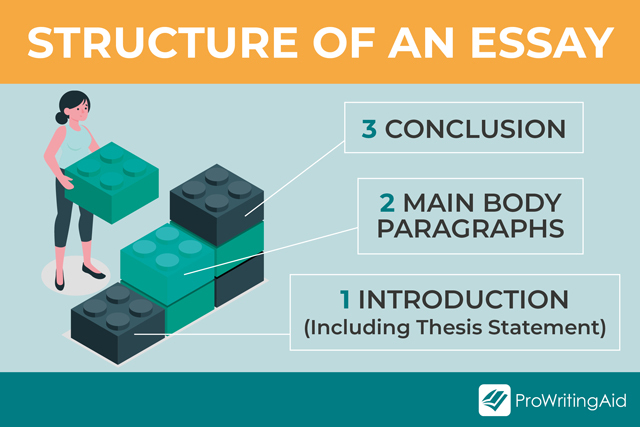

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

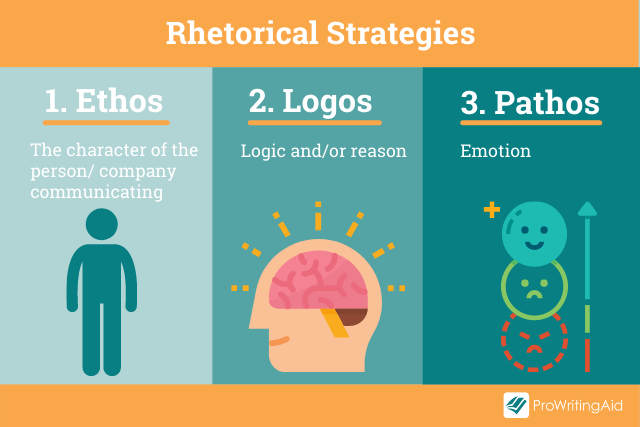

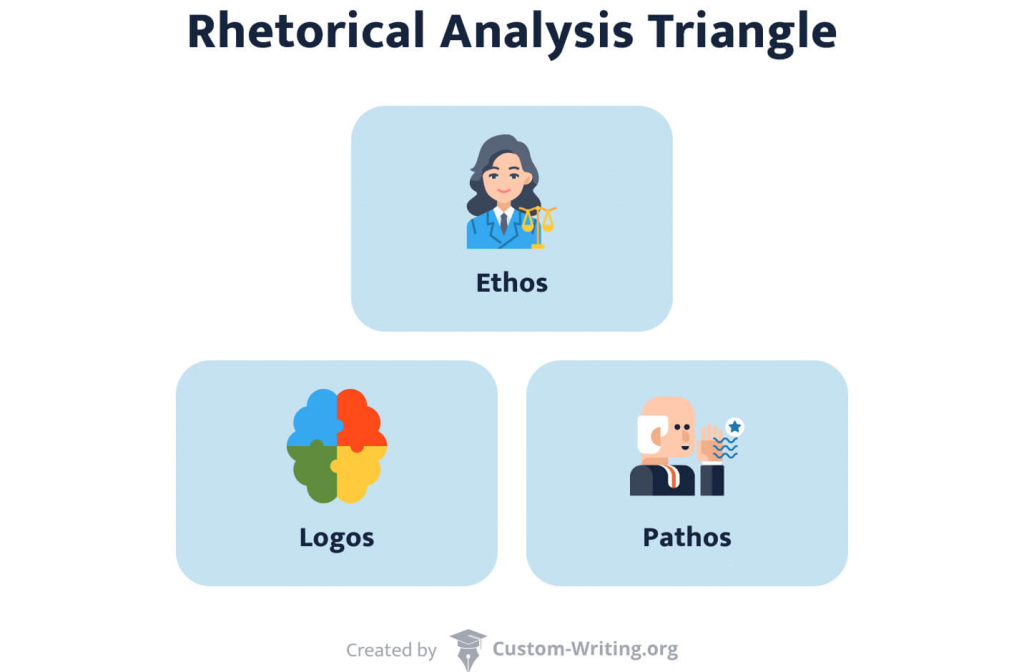

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

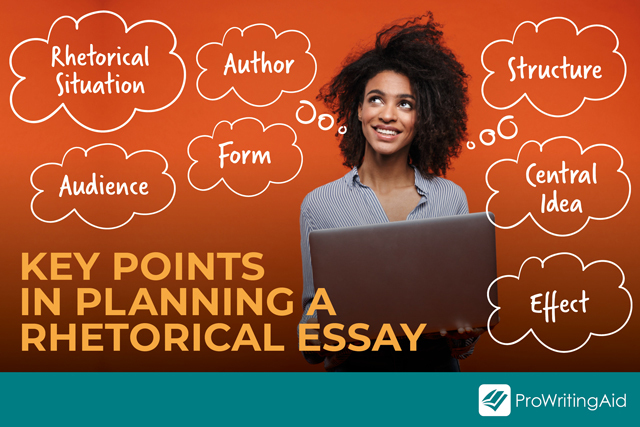

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

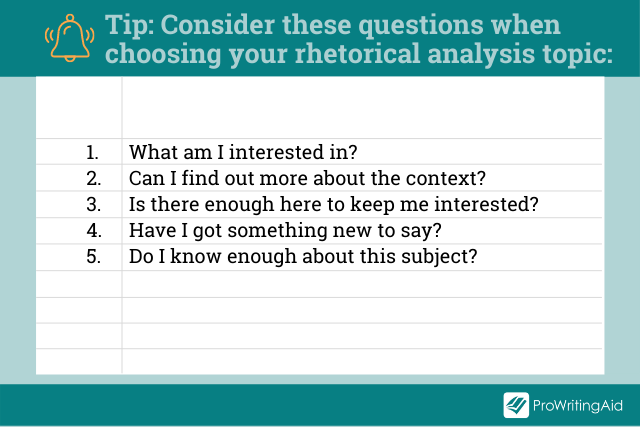

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

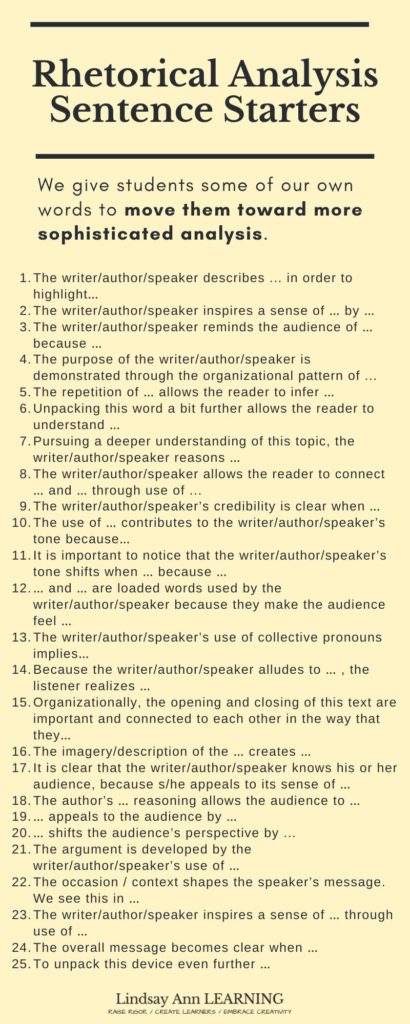

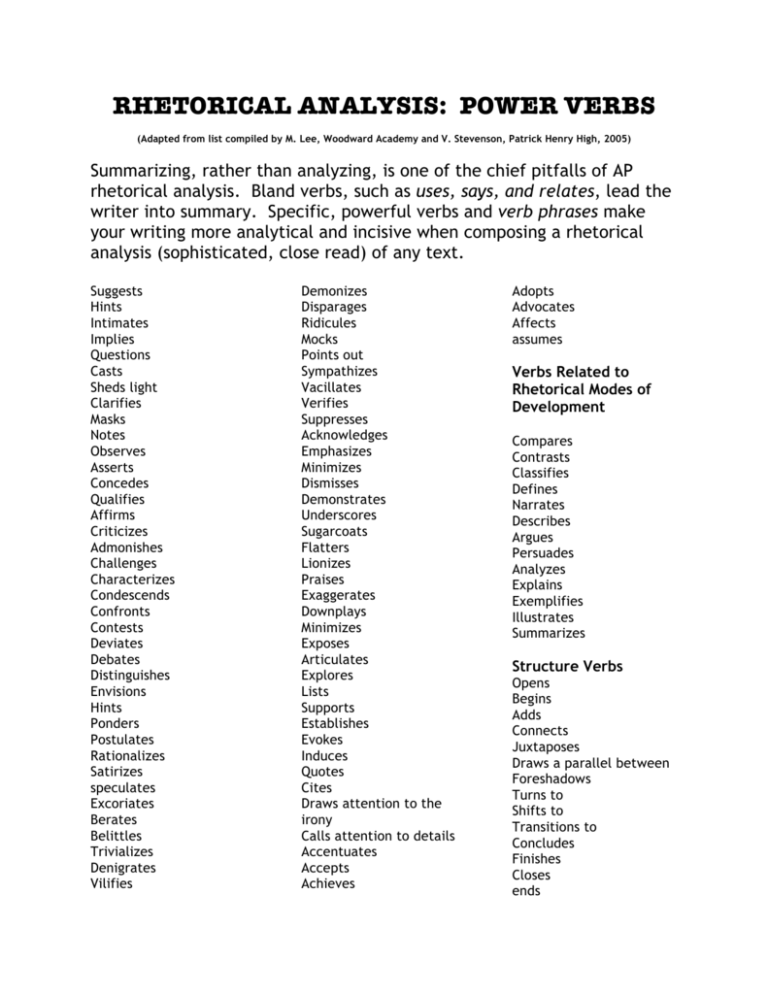

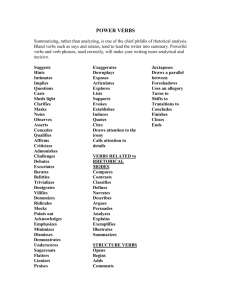

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

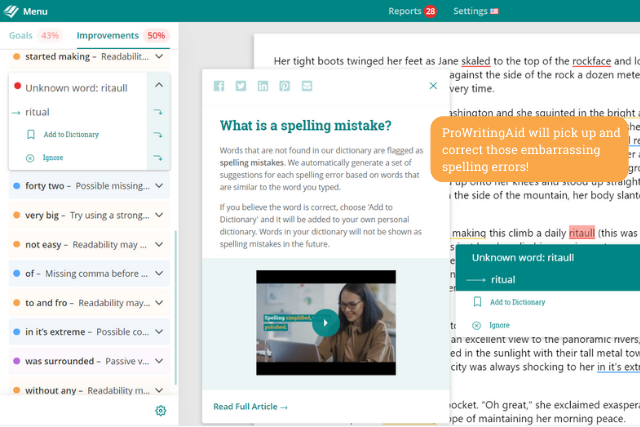

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

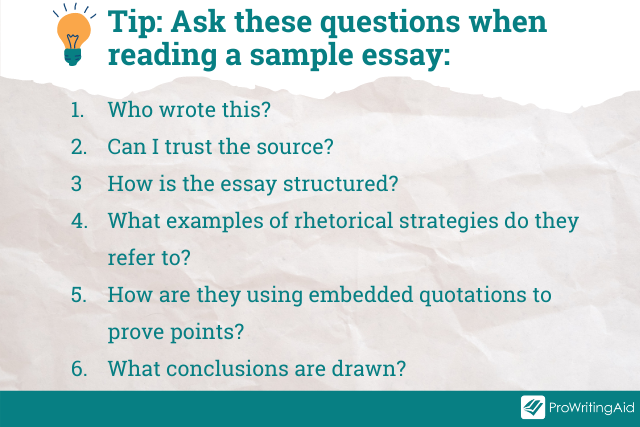

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

A Blog of Writing Resources from The University of Scranton's Writing Center

- BLOG OF RESOURCES FOR WRITERS

- Tutor to Tutor Talk

- STYLE GUIDES & CITATION MACHINES

- PAPER GUIDES

- ELL RESOURCES

- Helpful Handouts

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis

- Read the prompt closely to make sure you understand what you need to do within your essay. Generally, in a rhetorical analysis, your instructor wants you to determine why text is or isn’t effective in persuading the audience. However, you may not always be analyzing text—you may instead be asked to look at speech or an even an image. Sometimes the instructor will present you with the item you have to analyze, but other times you may have the opportunity of choosing your own item. Both situations have pros and cons. Is the prompt asking you to do a task like this? If so, it may be a rhetorical analysis. Check out this sample prompt here.

- Read the text closely. Annotate as you read in order to identify parts of the text that you found to be persuasive or that stood out. Those memorable moments are likely rhetorical devices or appeals. Additionally, try to understand the author’s thesis and organizational strategy as you read. Does the presentation of topics work? Are there any images used? Are any stories used? Are there jokes or word-play? Is the word choice crafted in an unusual way?

- Determine the purpose of the text you are evaluating. Because you are examining the effectiveness of a text, you first need to understand its aim in order to know if it is truly fulfilling its purpose. What is the author’s intention? What is the author trying to convey to the audience? Are they informing their audience? Entertaining their audience? Persuading their audience? Is that goal achieved?

- First, ask yourself, what is this text about and who would be motivated to read this text? For example, is it the text about updated baseball regulations? Then players, coaches, and sports enthusiasts would be interested.

- Where was this text published? What other materials does that source publish? Who generally reads the content that is published? Is it in a scholarly journal? A newspaper? A magazine? The publisher usually indicates something about the target audience.

- When and where was it published? What was happening at this location when the text was published? What issues were potential readers interested in?

- Who is the author? What makes them a credible source on this topic? What else have they written? Who generally reads their writings?

- How much background knowledge does the author present. Are they writing for content experts or a more general audience?

- In the text, are there any references or allusions the author makes? For example, are there references to shows, events, or trends from this generation or another generation?

- In order to prevent your writing from falling into summary, we suggest you use EMPHATIC ORDER, not Chronological Order, so you will NOT have an essay that mirrors the presentation of topics in the original text (For example, “First, the author presented this idea, and then this idea.”). Instead, organize your essay based on frequency or importance of the rhetorical devices used. (One powerful moment was the use of ethos at in the middle of the text . . . Another important element was the way anaphora was used at the end . . .) You can read more about organizational patterns here .

- Ethos: Are there any places in the text that made you want to trust the author? Does the author demonstrate their credibility or moral code?

- Pathos: Are there any places in the text that caused you to laugh or cringe? Was there any section that made you feel excited or sad?

- Kairos: Are there references to other events that are happening? What made this text relevant when it was published? How is the text “timely”?

- Obviously, logic is a crucial element of an argument. One way to check logic is to look for fallacies or specific flaws in the way logic is used. For example, circular reasoning and proof-by-too-few examples are common fallacies. Here’s some examples of poor logic .

- Rhetorical Devices: anaphora, anthesis, hyperbole, pleonasm, oxymoron, etc . Aside from the appeals, are there other rhetorical devices that convey the information in a specific way to elicit a response from the audience? Some of them may look familiar because they are also literary devices.

- Other Rhetorical Strategies or “Slanters”: euphemisms, down-players, and innuendo . These are some specific techniques used to subtly portray information in a positive or negative light to a target audience.

- Templates: The author uses ________, ________, and ______ to effectively persuade the audience on this topic.

- Example: Smith uses ethos, pathos, logos in his article “Updated Baseball Rules Strike Out” to persuade his readers that the new regulations in baseball hinder the game-play.

- Use the present tense when describing actions in the piece.

- Use the present tense when describing what the author does.

- Write the author’s name correctly . When you reference the author, write their first and last name the very first time you reference them. Use only the last name when referring to the author later in your paper.

- Use direct quotes from the text . Generally, it’s better to use the quotes than to paraphrase so your reader can see the exact form of rhetoric. Since you are talking about how a text is crafted, the reader needs to see the original text. Here’s some examples of integrating quotes .

- You must provide an explanation of each quote . What is the significance of the quote? What does it show or how does it demonstrate rhetoric?

- Make sure you cite your quotes correctly by using in-text citations. Check out this quick guide . If you have multiple works by the same author, you’ll need to include some extra information.

- Indicate titles correctly. Titles of larger works or containers (like books, plays, anthologies) are italicized . Shorter works within containers (like articles, chapters, poems, short stories) have “quotes” around them.

- Use strong verbs. Let’s avoid “is”, “are”, “has”, “does”, and maybe even move away from “says” and “states”. Check out the list of strong verbs for literary essays here.

- Use your professor’s office hours. Once you have a rough draft, go to your professor’s office hours and see if you’re on the right track. Don’t skip this step. Professors may look for different qualities in papers, and you need to know what they expect from you.

- Beware of the internet and Chat GPT. I know students will browse the internet as a way to get their own ideas flowing. Don’t do it! But, if you can’t resist this temptation, then keep track of each source you read and remember to cite it correctly if you use that idea or a very similar idea anywhere in your paper. Remember, your analysis is your opinion on how devices were used in this text; you don’t need to know what other people think about this text. Instead, learn the rhetorical appeals, devices, and strategies because they will help you approach the text from a critical perspective.

- Take full advantage of peer review or meet with a writing consultant. A reader can help you see the gaps in your argument or indicate where more explanation is needed. They can also help your analysis become more thorough by questioning your claims and adding their own perspectives on the quotes you use as evidence.

- Make sure you are conforming to rules of the format indicated by your instructor. Usually, composition instructors use MLA, but sometimes they use APA. Check out our style guides if you need more information.

Other Tools and Resources

- Resources for Freshmen

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- General Writing Tips

- Resources for English Language Learners

- Resources for Graduate Students

- Resources for Neurodiverse Writers

- Resources for Seniors

- Resources of OT Students

© 2024 Scranton Writes

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

9.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically about Rhetoric

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a rhetorical analysis through multiple drafts.

- Identify and analyze rhetorical strategies in a rhetorical analysis.

- Demonstrate flexible strategies for generating ideas, drafting, reviewing, collaborating, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Give and act on productive feedback for works in progress.

The ability to think critically about rhetoric is a skill you will use in many of your classes, in your work, and in your life to gain insight from the way a text is written and organized. You will often be asked to explain or to express an opinion about what someone else has communicated and how that person has done so, especially if you take an active interest in politics and government. Like Eliana Evans in the previous section, you will develop similar analyses of written works to help others understand how a writer or speaker may be trying to reach them.

Summary of Assignment: Rhetorical Analysis

The assignment is to write a rhetorical analysis of a piece of persuasive writing. It can be an editorial, a movie or book review, an essay, a chapter in a book, or a letter to the editor. For your rhetorical analysis, you will need to consider the rhetorical situation—subject, author, purpose, context, audience, and culture—and the strategies the author uses in creating the argument. Back up all your claims with evidence from the text. In preparing your analysis, consider these questions:

- What is the subject? Be sure to distinguish what the piece is about.

- Who is the writer, and what do you know about them? Be sure you know whether the writer is considered objective or has a particular agenda.

- Who are the readers? What do you know or what can you find out about them as the particular audience to be addressed at this moment?

- What is the purpose or aim of this work? What does the author hope to achieve?

- What are the time/space/place considerations and influences of the writer? What can you know about the writer and the full context in which they are writing?

- What specific techniques has the writer used to make their points? Are these techniques successful, unsuccessful, or questionable?

For this assignment, read the following opinion piece by Octavio Peterson, printed in his local newspaper. You may choose it as the text you will analyze, continuing the analysis on your own, or you may refer to it as a sample as you work on another text of your choosing. Your instructor may suggest presidential or other political speeches, which make good subjects for rhetorical analysis.

When you have read the piece by Peterson advocating for the need to continue teaching foreign languages in schools, reflect carefully on the impact the letter has had on you. You are not expected to agree or disagree with it. Instead, focus on the rhetoric—the way Peterson uses language to make his point and convince you of the validity of his argument.

Another Lens. Consider presenting your rhetorical analysis in a multimodal format. Use a blogging site or platform such as WordPress or Tumblr to explore the blogging genre, which includes video clips, images, hyperlinks, and other media to further your discussion. Because this genre is less formal than written text, your tone can be conversational. However, you still will be required to provide the same kind of analysis that you would in a traditional essay. The same materials will be at your disposal for making appeals to persuade your readers. Rhetorical analysis in a blog may be a new forum for the exchange of ideas that retains the basics of more formal communication. When you have completed your work, share it with a small group or the rest of the class. See Multimodal and Online Writing: Creative Interaction between Text and Image for more about creating a multimodal composition.

Quick Launch: Start with a Thesis Statement

After you have read this opinion piece, or another of your choice, several times and have a clear understanding of it as a piece of rhetoric, consider whether the writer has succeeded in being persuasive. You might find that in some ways they have and in others they have not. Then, with a clear understanding of your purpose—to analyze how the writer seeks to persuade—you can start framing a thesis statement : a declarative sentence that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic the rest of the paper will support.

Complete the following sentence frames as you prepare to start:

- The subject of my rhetorical analysis is ________.

- My goal is to ________, not necessarily to ________.

- The writer’s main point is ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded (or not) because ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded in ________ (name the part or parts) but not in ________ (name the part or parts).

- The writer’s strongest (or weakest) point is ________, which they present by ________.

Drafting: Text Evidence and Analysis of Effect

As you begin to draft your rhetorical analysis, remember that you are giving your opinion on the author’s use of language. For example, Peterson has made a decision about the teaching of foreign languages, something readers of the newspaper might have different views on. In other words, there is room for debate and persuasion.

The context of the situation in which Peterson finds himself may well be more complex than he discusses. In the same way, the context of the piece you choose to analyze may also be more complex. For example, perhaps Greendale is facing an economic crisis and must pare its budget for educational spending and public works. It’s also possible that elected officials have made budget cuts for education a part of their platform or that school buildings have been found obsolete for safety measures. On the other hand, maybe a foreign company will come to town only if more Spanish speakers can be found locally. These factors would play a part in a real situation, and rhetoric would reflect that. If applicable, consider such possibilities regarding the subject of your analysis. Here, however, these factors are unknown and thus do not enter into the analysis.

Introduction

One effective way to begin a rhetorical analysis is by using an anecdote, as Eliana Evans has done. For a rhetorical analysis of the opinion piece, a writer might consider an anecdote about a person who was in a situation in which knowing another language was important or not important. If they begin with an anecdote, the next part of the introduction should contain the following information:

- Author’s name and position, or other qualification to establish ethos

- Title of work and genre

- Author’s thesis statement or stance taken (“Peterson argues that . . .”)

- Brief introductory explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis or stance

- If relevant, a brief summary of context and culture

Once the context and situation for the analysis are clear, move directly to your thesis statement. In this case, your thesis statement will be your opinion of how successful the author has been in achieving the established goal through the use of rhetorical strategies. Read the sentences in Table 9.1 , and decide which would make the best thesis statement. Explain your reasoning in the right-hand column of this or a similar chart.

The introductory paragraph or paragraphs should serve to move the reader into the body of the analysis and signal what will follow.

Your next step is to start supporting your thesis statement—that is, how Octavio Peterson, or the writer of your choice, does or does not succeed in persuading readers. To accomplish this purpose, you need to look closely at the rhetorical strategies the writer uses.

First, list the rhetorical strategies you notice while reading the text, and note where they appear. Keep in mind that you do not need to include every strategy the text contains, only those essential ones that emphasize or support the central argument and those that may seem fallacious. You may add other strategies as well. The first example in Table 9.2 has been filled in.

When you have completed your list, consider how to structure your analysis. You will have to decide which of the writer’s statements are most effective. The strongest point would be a good place to begin; conversely, you could begin with the writer’s weakest point if that suits your purposes better. The most obvious organizational structure is one of the following:

- Go through the composition paragraph by paragraph and analyze its rhetorical content, focusing on the strategies that support the writer’s thesis statement.

- Address key rhetorical strategies individually, and show how the author has used them.

As you read the next few paragraphs, consult Table 9.3 for a visual plan of your rhetorical analysis. Your first body paragraph is the first of the analytical paragraphs. Here, too, you have options for organizing. You might begin by stating the writer’s strongest point. For example, you could emphasize that Peterson appeals to ethos by speaking personally to readers as fellow citizens and providing his credentials to establish credibility as someone trustworthy with their interests at heart.

Following this point, your next one can focus, for instance, on Peterson’s view that cutting foreign language instruction is a danger to the education of Greendale’s children. The points that follow support this argument, and you can track his rhetoric as he does so.

You may then use the second or third body paragraph, connected by a transition, to discuss Peterson’s appeal to logos. One possible transition might read, “To back up his assertion that omitting foreign languages is detrimental to education, Peterson provides examples and statistics.” Locate examples and quotes from the text as needed. You can discuss how, in citing these statistics, Peterson uses logos as a key rhetorical strategy.

In another paragraph, focus on other rhetorical elements, such as parallelism, repetition, and rhetorical questions. Moreover, be sure to indicate whether the writer acknowledges counterclaims and whether they are accepted or ultimately rejected.

The question of other factors at work in Greendale regarding finances, or similar factors in another setting, may be useful to mention here if they exist. As you continue, however, keep returning to your list of rhetorical strategies and explaining them. Even if some appear less important, they should be noted to show that you recognize how the writer is using language. You will likely have a minimum of four body paragraphs, but you may well have six or seven or even more, depending on the work you are analyzing.

In your final body paragraph, you might discuss the argument that Peterson, for example, has made by appealing to readers’ emotions. His calls for solidarity at the end of the letter provide a possible solution to his concern that the foreign language curriculum “might vanish like a puff of smoke.”

Use Table 9.3 to organize your rhetorical analysis. Be sure that each paragraph has a topic sentence and that you use transitions to flow smoothly from one idea to the next.

As you conclude your essay, your own logic in discussing the writer’s argument will make it clear whether you have found their claims convincing. Your opinion, as framed in your conclusion, may restate your thesis statement in different words, or you may choose to reveal your thesis at this point. The real function of the conclusion is to confirm your evaluation and show that you understand the use of the language and the effectiveness of the argument.

In your analysis, note that objections could be raised because Peterson, for example, speaks only for himself. You may speculate about whether the next edition of the newspaper will feature an opposing opinion piece from someone who disagrees. However, it is not necessary to provide answers to questions you raise here. Your conclusion should summarize briefly how the writer has made, or failed to make, a forceful argument that may require further debate.

For more guidance on writing a rhetorical analysis, visit the Illinois Writers Workshop website or watch this tutorial .

Peer Review: Guidelines toward Revision and the “Golden Rule”

Now that you have a working draft, your next step is to engage in peer review, an important part of the writing process. Often, others can identify things you have missed or can ask you to clarify statements that may be clear to you but not to others. For your peer review, follow these steps and make use of Table 9.4 .

- Quickly skim through your peer’s rhetorical analysis draft once, and then ask yourself, What is the main point or argument of my peer’s work?

- Highlight, underline, or otherwise make note of statements or instances in the paper where you think your peer has made their main point.

- Look at the draft again, this time reading it closely.

- Ask yourself the following questions, and comment on the peer review sheet as shown.

The Golden Rule

An important part of the peer review process is to keep in mind the familiar wisdom of the “Golden Rule”: treat others as you would have them treat you. This foundational approach to human relations extends to commenting on others’ work. Like your peers, you are in the same situation of needing opinion and guidance. Whatever you have written will seem satisfactory or better to you because you have written it and know what you mean to say.

However, your peers have the advantage of distance from the work you have written and can see it through their own eyes. Likewise, if you approach your peer’s work fairly and free of personal bias, you’re likely to be more constructive in finding parts of their writing that need revision. Most important, though, is to make suggestions tactfully and considerately, in the spirit of helping, not degrading someone’s work. You and your peers may be reluctant to share your work, but if everyone approaches the review process with these ideas in mind, everyone will benefit from the opportunity to provide and act on sincerely offered suggestions.

Revising: Staying Open to Feedback and Working with It

Once the peer review process is complete, your next step is to revise the first draft by incorporating suggestions and making changes on your own. Consider some of these potential issues when incorporating peers’ revisions and rethinking your own work.

- Too much summarizing rather than analyzing

- Too much informal language or an unintentional mix of casual and formal language

- Too few, too many, or inappropriate transitions

- Illogical or unclear sequence of information

- Insufficient evidence to support main ideas effectively

- Too many generalities rather than specific facts, maybe from trying to do too much in too little time

In any case, revising a draft is a necessary step to produce a final work. Rarely will even a professional writer arrive at the best point in a single draft. In other words, it’s seldom a problem if your first draft needs refocusing. However, it may become a problem if you don’t address it. The best way to shape a wandering piece of writing is to return to it, reread it, slow it down, take it apart, and build it back up again. Approach first-draft writing for what it is: a warm-up or rehearsal for a final performance.

Suggestions for Revising

When revising, be sure your thesis statement is clear and fulfills your purpose. Verify that you have abundant supporting evidence and that details are consistently on topic and relevant to your position. Just before arriving at the conclusion, be sure you have prepared a logical ending. The concluding statement should be strong and should not present any new points. Rather, it should grow out of what has already been said and return, in some degree, to the thesis statement. In the example of Octavio Peterson, his purpose was to persuade readers that teaching foreign languages in schools in Greendale should continue; therefore, the conclusion can confirm that Peterson achieved, did not achieve, or partially achieved his aim.

When revising, make sure the larger elements of the piece are as you want them to be before you revise individual sentences and make smaller changes. If you make small changes first, they might not fit well with the big picture later on.

One approach to big-picture revising is to check the organization as you move from paragraph to paragraph. You can list each paragraph and check that its content relates to the purpose and thesis statement. Each paragraph should have one main point and be self-contained in showing how the rhetorical devices used in the text strengthen (or fail to strengthen) the argument and the writer’s ability to persuade. Be sure your paragraphs flow logically from one to the other without distracting gaps or inconsistencies.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/9-5-writing-process-thinking-critically-about-rhetoric

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

How to use rhetorical moves in your writing and why they matter

I fear we have lost the word “rhetoric” in its good and original sense, defined by the “American Heritage Dictionary” as “the art or study of using language effectively and persuasively.” That meaning still applies if you are studying Cicero or taking a good English composition course. But a semantic shift is under way, described by a tertiary definition: “Language that is elaborate, pretentious, insincere, or intellectually vacuous.”

No one thought or talked much about rhetoric during the presidency of George W. Bush, his critics focused on gaffes which made him sound and appear the buffoon. But the ascendancy of Barack Obama brought rhetoric back into the foreground, and not in a good way. His political opponents – from Hillary Clinton to Mitt Romney – tried to turn Obama’s word power into a pejorative. In summary, the critics suggested that the candidate and then the president was a good speaker, a good reader from the teleprompter, but not a leader, not a principled person of action.

This sense is captured best in the phrase “empty rhetoric,” suggesting a chasm between the world of language and ideas and the world of policy and political tactics. That Obama came from an unusual ethnic and culture heritage brought race into the equation. For some early critics in the African-American community, there rose debate about whether the candidate was black enough, and from the extreme right came the sense that this cosmopolitan orator was superior and detached – “uppity” in the old racist parlance.

As a critical reader, I need the ability to sniff out rhetoric that is empty, but as a writer I depend upon a rhetoric that is full. I didn’t attempt to make that last sentence seem “rhetorical,” but it is, a product of the see-saw effect of the parallel phrases “rhetoric that is empty” with “rhetoric that is full.” When I use the phrase “see-saw effect,” you are getting more rhetoric, a metaphor designed to help you “see” an image to help explain a linguistic abstraction: the power of comparison and contrast.

So there are rhetorical moves everywhere. The more you read and listen carefully, the more you will recognize them. The more you recognize, the more you will find opportunities to use these moves in your own speaking and writing.

The ancient rhetoricians had names for just about every language move, so many as to defy memory and utility. But a few names for a few rhetorical moves will help you become a more elegant and persuasive writer.

Let’s take the word zeugma , for example, a move in which a single verb in a sentence creates two different senses by its attachment to two different objects. The AHD offers “He took my advice and my wallet.” Nice. Let me try a couple: “Gingrich dragged out his seven point plan and his blondest wife.” Or, “The County Commission voted to restore fluoride to the water and sanity to the public debate.”

James Geary, an expert on aphorisms, taught me a new move called a chiasmus , the name of the Greek letter X, in which two parallel phrases have their elements inverted. Try to remember the first time you heard that “it’s not the size of the dog in the fight, but the size of the fight in the dog that counts.” The effect is a perfect cross between the catchy and the memorable. How about JFK’s “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country”?

Here are several I found in a collection of inspirational sayings titled “Patches of Godlight” by Jan Karon:

“We do not need to get good laws to restrain bad people. We need to get good people to restrain bad laws.” – G.K. Chesterton “Therefore seek not to understand that you may believe, but believe that you may understand.” — St. Augustine “Courage is not having the strength to go on; it is going on when you don’t have the strength.” – Theodore Roosevelt “The Bible will keep you from sin, or sin will keep you from the Bible.” – D.L. Moody “Those who make religion their god will not have God for their religion.” – Thomas Erskine

Most of these seem devout, but who knew when I first told this old joke that I was passing along a chiasmus: “I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy.” Here the parallels are replaced by the rhythm of the puns. Even Mae West got into the act: “It’s not the men in your life that matters, it’s the life in your men.”

To keep filling you up with rhetoric, let me offer a handful of the most common and useful moves, with definitions from the AHD.

Synecdoche (not to be confused with Schenectady):

“A figure of speech in which a part is used for the whole (as hand for sailor), the whole for the part (as law for police officer), the specific for the general (as cutthroat for assassin)…or the material for the things made from it (as steel for sword).”

Metonymy (not to be confused with monotony):

“A figure of speech in which one word or phrase is substituted for another with which it is closely associated, as in the use of Washington for the United States Government or of the sword for military power.”

Hyperbole (not to be confused with hyperbola):

“A figure of speech in which exaggeration is used for emphasis or effect, as in I could sleep for a year or This book weighs a ton .”

“A figure of speech consisting of an understatement in which an affirmative is expressed by negating its opposite, as in This is no small problem .” (How about this understatement when the Taco Bell chihuahua tries to trap Godzilla: “I think I need a bigger box.”)

Connotation

“The set of associations implied by a word in addition to its literal meaning….” As in Hollywood holds connotations of romance and glittering success .

Add to the list the more commonly known rhetorical moves: parallelism, metaphor, simile, analogy, alliteration, and emphatic word order, and you have on your your lips or at your fingertips figures of speech and tools of writing that can serve you for a thousand years (that’s hyperbole).

Just remember it’s not the rhetoric in the writer that matters most, but the writer in the rhetoric, he said chiasmically.

PolitiFact launches Spanish-language website to serve more than 40 million U.S. Spanish-speakers

PolitiFact en Español is also active on WhatsApp, TikTok and Instagram to sort out political and social media claims

Opinion | The media can’t help but pay attention to startling new Biden-Trump polls

They said they wouldn’t get caught up in the horse race coverage this year. But some new polls have the media buzzing.

Jay-Z didn’t bribe country radio stations to play Beyoncé’s songs. This claim started as satire

The first two singles from ‘Cowboy Carter’ landed on Billboard’s country charts. Some social posts claimed they didn’t get there on their own merit.

Opinion | Donald Trump wants Paul Ryan fired. You can probably guess why.

The former Republican speaker of the House is on the board of Fox Corp.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. says a worm ate part of his brain. Experts said that’s unlikely.

Experts believe the worm was Taenia solium, or a pork tapeworm larva. This worm does not ‘eat’ brain tissue.

Comments are closed.

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

GrammarMill

What Are Rhetorically Accurate Verbs?

Not all verbs are the same because some verbs do more than tell you what’s happening. Rhetorically accurate verbs are like artists adding color and detail to a story. They paint the action into a striking scene by conveying it in a detailed way.

Let’s look closer at these literary tools to understand how they work.

What To Know About Rhetorically Accurate Verbs

What are rhetorically precise verbs? These verbs don’t just tell us what is happening but how it’s happening. They allow you to express actions in the most exact way possible, creating a clear and detailed image that engages senses and emotions.

Specific, powerful verbs and verb phrases can make your writing more analytical. People often use them in academic writing . However, they can also be very effective in narrative writing or storytelling. Using certain rhetorically accurate verbs can create a mood and engage readers.

What Does Rhetorically Accurate Mean?

The concept of rhetoric dates back to Ancient Greece. Aristotle defined this idea as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” Over time, the study of rhetoric has evolved and expanded. Still, it has consistently maintained its emphasis on creation and communication.

When we refer to something as “rhetorically accurate,” we mean it is precise, effective and appropriate within its specific rhetorical context.

What Are Some Examples of Rhetorically Accurate Verbs?

These action words can enhance the analytical nature of your writing.

- Demonstrate

The precision of the verbs makes your writing more authoritative.

Using a rhetorically accurate verb can also add depth to your sentence by providing a clear picture of the action you are describing.

- Whispers instead of says

- Bellows instead of yells

- Glimmers instead of shines

- Devours instead of eats

- Saunters instead of walks

- Beams instead of smiles

These verbs don’t merely tell us what’s happening but give us a sense of how it’s happening, making our writing more engaging and expressive.

Are Rhetorical Verbs the Same as Rhetorically Precise Verbs?

No, rhetorically accurate verbs are not the same as rhetorical verbs. Rhetorical verbs are a broad category of verbs used to describe actions.

However, not all rhetorical verbs are rhetorically accurate verbs. These precise verbs are a subset of rhetorical verbs. They describe the specific moves a writer or speaker makes in the most detailed way possible.

For example, common rhetorical verbs such as “says,” “states,” and “writes” are often replaced with rhetorically accurate verbs for more exactness.

While these verbs do indicate that the author is expressing something, they do not provide specific information about how the author is making their argument. Instead, verbs like “argues,” “implies,” “emphasizes,” and “scribbles” can more accurately describe the rhetorical moves.

Rhetorically Accurate Verbs Are Powerful Tools in Language

Rhetorically accurate verbs precisely convey the action in a sentence, enhancing the clarity and impact of the message. They allow the speaker or writer to describe an action and give the audience more context. Choosing the most fitting verb can transform a simple statement into a compelling narrative, making a rhetorically accurate verb the cornerstone of effective communication.

Let us know what you think about these writing tips ! We invite you to enrich our discussion by commenting below.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Outline: Examples & Strategies

Rhetorical analysis is never a simple task. This essay type requires you to analyze rhetorical devices in a text and review them from different perspectives. Such an assignment can be a part of an AP Lang exam or a college home task. Either way, you will need a solid outline to succeed with your writing. And we can help you nail it.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

In this article by our custom-writing team, you will find:

- the structure of a rhetorical analysis essay;

- a detailed guide and tips for writing a rhetorical essay outline;

- an example and a template for you to download.

- 📚 Rhetorical Analysis Structure

Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

- 📑 Example Outline & Template

🔍 References

📚 structure of a rhetorical analysis essay: pre-writing.

The first thing you need to know before you start working on your essay is that the analysis in your paper is strictly rhetorical. In other words, you don’t need to discuss what the author is saying. Instead, it’s a take on how the author says it.

And to understand “how,” you need to find rhetorical appeals. An appeal is a technique that the author uses to convince the reader. The main ones are logos, ethos, and pathos.

The whole analysis is structured around them and divided into 3 parts: appeals in the text’s introduction, in the body paragraphs, and in its conclusion.

Remember that it’s essential to structure your essay in chronological order. To put it simply, it’s better not to describe the appeals from the conclusion before the ones in the introduction. Follow the structure of the text you’re analyzing, and you’ll nail it.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Rhetorical Analysis Triangle

We’ve already mentioned ethos, pathos, and logos. The rhetorical triangle is another name for these 3 main appeals. Let’s examine them in more detail:

In your essay, it’s best to mention all 3 appeals. It’s also necessary to measure their effectiveness and give examples. A good strategy is to find the appeals in the text, underline them, and analyze them before writing the outline.

Each appeal can be characterized by the following:

- Diction. Diction is the words that the author uses to describe the idea. When analyzing diction, you want to find words that stand out in the text.

- Syntax. Simply put, syntax is the order of words used by the author. You can also look at the sentence length as a part of the syntax.

- Punctuation. This characteristic is all about the usage of punctuation marks. Aside from commas, it’s good to pay attention to colons and dashes. Authors can use them to focus the audience’s attention on something or create a dramatic disjunction.

- Tone. It’s the author’s attitude towards the discussed idea. The tone is a combination of diction, syntax, and punctuation. For example, you can tell if the author is interested or not by evaluating the length of sentences.

Remember that all 3 appeals are artistic proofs, and you shouldn’t confuse them with factual evidence. The difference between them lies in the amount of effort:

- Citing factual evidence requires no skill. You create proof just by mentioning the fact.

- In the case of artistic proof , you must use your knowledge of rhetoric to create it.

SOAPS: Rhetorical Analysis

SOAPS is a helpful technique for conducting a rhetorical analysis. It’s fairly popular and is recommended for AP tests. SOAPS stands for:

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 15% off your first order!

Answering the questions above will make it easy for you to find the necessary appeals.

✍️ How to Write an Outline for a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

Now that you’ve found the appeals and analyzed them, it’s time to write the outline. We will explain it part by part, starting with the introduction.

How to Write an Introduction for a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

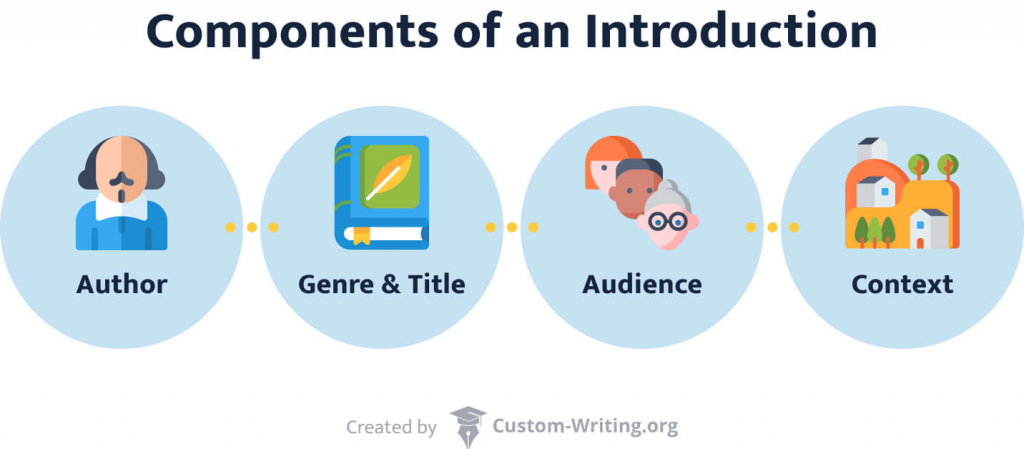

In a rhetorical analysis, the introduction is different from that of a regular essay. It covers all the necessary information about the author of the text:

- Name (or names, if there are several authors.)

- Genre and title of the reviewed work.

The author claims that cats are better pets than dogs.

- The target audience that the writer is aiming at.

- The context in which the text was produced, e.g. a specific event.

Aside from that, a rhetorical essay introduction should include a hook and a thesis statement. Want to know how to write them? Keep reading!

How to Write a Hook for a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

A hook is a sentence that grabs the reader’s attention. You can do it by presenting an interesting fact about the author. You may also use an inspiring or amusing quote. Make sure your hook is connected with the text you are writing about.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

For example, if you’re analyzing MLK’s I Have a Dream speech, you can hook the reader with the following sentence:

Martin Luther King is widely considered the most famous speaker in history.

Our article on hooks in writing can provide you with e great ideas.

Thesis Statement for Rhetorical Analysis Essay

In a rhetorical analysis essay, you don’t need to create a thesis statement in the usual sense. Instead, you describe the main point made by the author using a rhetorically accurate verb (such as “claims” or “asserts”) followed by a “that” clause.

For example, your thesis can focus on the techniques that the author uses to convince the audience. If we look at the I Have a Dream speech, we will notice several stylistic elements:

It’s not a complete list, but that’s enough to form a decent thesis.

We also need to mention the ideas behind the speech. The main idea is, obviously, equality. So, we’ll put it in our thesis as well. As a result, we have something like this:

Through the skillful usage of metaphor, repetition, and symbolism Martin Luther King effectively fills his audience’s hearts with the idea of unity and equality.

Rhetorical Analysis Body Paragraphs

If you are writing a generic 5-paragraph essay, you can divide your essay’s body into 3 parts:

- A paragraph about appeals in the text introduction.

- A section about rhetorical devices in the text’s body.

- A paragraph about rhetorical devices in the text’s conclusion.

Sometimes there is no distinct structure in a text. If that’s the case, just analyze the appeals in chronological order. You can also split the analysis based on the type of appeals. For example:

- A paragraph about emotional appeals.

- A section about logical appeals.

- A paragraph about ethical appeals.

Each of your essay’s body paragraphs should have 3 key elements:

- Topic sentence that shows what appeal you will discuss in the section.

- Examples that illustrate the rhetorical device you want to showcase.

- Your take on the effectiveness of the given device.

It’s good to remember that every appeal you talk about needs an example. If you can illustrate your claim about a strategy with more examples, then go for it. The more examples, the better.

Good Transition Words for Rhetorical Analysis Essay

Transition words allow you to follow up one idea with another. They also help build connections between paragraphs. Choosing correct transition words depends on the strategy you use. If you want to build a sequence of a cause and its effect, you will need words like “thus” or “hence.” If you’re going to clarify something, you should use a different set of words.

Here’s a list of helpful transition words suitable in different contexts:

Rhetorical Analysis Verbs to Use

A rhetorical analysis essay is a serious work that often touches on complex topics. Regular verbs like “tells us” or “shows” don’t always fit it. To make your paper more inclusive and precise, consider using strong verbs .

Strong verbs (or power verbs) are typically used when talking about the author. That includes their strategies, attitude, personality, or ideas.

For example, instead of “the author says,” you can use “suggests” or “clarifies,” depending on the context.

Some other rhetorically accurate verbs include:

- Sheds light

You don’t have to use strong verbs only. If you feel like “says” suits your point better than any strong verb, feel free to use it.

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Conclusion

The conclusion is the ending of your paper. It sums your essay up and underlines the points you’ve made in the body paragraphs. A good conclusion should accomplish several things:

- Paraphrasing the thesis . You shouldn’t just rewrite the thesis from the introduction. The restatement is usually used to demonstrate a deeper understanding of your point.

- A summary of the body paragraphs . Again, simple repetition is not enough. We need to link the points to our thesis and underline the importance of our statements.

- Final thoughts . A powerful epilogue will leave a good impression about your work.

Make sure to avoid including any new ideas or statements. The conclusion is exclusively for summarizing. If you found yourself putting a new assertion in the ending, it’s probably a good idea to restructure your body paragraphs.

📑 Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example Outline & Template

To make the writing process even easier for you, we will show you what an outline for your essay can look like. As an example, we will outline a rhetorical analysis of MLK’s I Have a Dream speech. We are going to structure it according to the appeals.

Have a look:

- Hook . An interesting fact about the MLK or his quote. An emotional start about the importance and the lasting legacy of the speech will also work.

- The speaker’s name, occupation, and years of life.

- The context in which the subject of our essay was produced.

- The speech’s target audience.

- Thesis statement . Point out the appeals you are going to write about. Describe their impact on the author’s general argumentation.

Body paragraphs

- Underline the often use of metaphor. Set “lonely island of poverty” and “ocean of material prosperity” as examples.

- Talk about the usage of repetition. Use the constant repetition of “I have a dream…” as an illustration.

- Demonstrate the use of logos. Mention King citing President Lincoln as an authority for his argumentation.

- Showcase the ethos of the speech. Notice that MLK’s Civil Rights Movement logic correlates with social ethics at the time.

- Comparing segregation to a “bad check.”

- Referring to the Civil Rights Movement as “my people.”

- Comparing the acquisition of equality to “cashing a check.”

- Restate the thesis. Demonstrate a deeper understanding of the point made in the introduction.

- Summary of the body paragraphs. Connect them to the thesis statement. Give a final take on King’s rhetorical strategies and evaluate their effectiveness.

- Closing thought. Finish by stating the primary goal of your analysis.

Alternatively, you can structure your essay in chronological order. Below you’ll find a template you can use for this type of rhetorical analysis. Simply download the PDF file below and fill in the blanks.

Rhetorical Analysis Outline Template

(your essay’s title)

Introduction.

The speaker/author is (state the author’s name.) The purpose of the text is to (state the text’s purpose.) The text is intended for (describe the text’s intended audience.)

Check out the rhetorical analysis samples below to get some ideas for your paper.

- Greta Thunberg’s Speech: Rhetorical Analysis

- Rhetorical Analysis: “In Defense of the ‘Impractical’ English Major” by C. Gregoire and “Top 10 Reasons You’re Not Wasting Your Time as an English Major” by S. Reeves

- Steve Jobs’ Commencement Speech Rhetorical Analysis

- The Speech “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” by Martin Luther King, Jr: Rhetorical Analysis

- Rhetorical Analysis Through Lyrics: “The Times They Are A-Changing” and “The Wind of Change”

- Roiphe’s Confessions of a Female Chauvinist Sow: Rhetorical Analysis

- “Snack Attack”: Rhetorical Analysis

- Rhetorical Analysis of “Hidden Intellectualism” by Gerald Graff

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Topics

- Analyze rhetorical appeals of a Hallmark’s commercial

- Rhetorical devices and the atmosphere of Hamlet’s To Be or Not to Be monologue

- The author’s argument in Us film

- Compare pathos, ethos, and logos in two advertisements

- Google Analytics : rhetorical analysis

- The background and the audience of the Gillette commercial short film

- Rhetorical analysis of capitalism and socialism

- What makes John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address iconic?

- The significance of the historical parallel in Susan B. Anthony’s speech

- Sarcasm and skepticism in Shikha Dalmia’s article

- Rhetorical analysis of political debates between Biden, Harris, and Booker

- What makes Letter From Birmingham Jail powerful?

- Problems of the modern education in Moore’s Idiot Nation and Gatto’s Against School

- Rhetorical techniques in Learning to Read and Write by Frederick Douglass

- Compare and contrast Antigone and Creon

- The word framing of Michelle Obama’s TED speech

- James Q. Wilson’s arguments on gun ownership laws

- Analyze ethos, pathos, and logos in a video advertisement

- What makes the 2005 speech by Steve Jobs remarkable?

- How does Jenna Berko convince readers in her essay?

- Successful persuasion in the film Henry V

- Margaret Fuller and Frederick Douglass : a rhetorical comparison

- Characters, setting, and emotions in Of Mice and Men

- Web blogs rhetorical analysis

- Rhetorical devices in Barbara Holland’s collection of thoughts

- Conduct a rhetorical analysis of Louis C. K.’s Shameless

- What makes Claire Giordano’s essay convincing?

- Biblical allusions in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas

- Ali Siddiq’s ‘Prison Riot’ standup: a rhetorical analysis

- Presentation of interracial romance in Get Out movie

- Rhetoric Instruments in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States

- How does Barack Obama try to change reality with his speech?

- Target and purpose of L’Oreal EverCrème advertisement

- Perform a rhetorical analysis of Pop Can: Popular Culture in Canada

- The Myth of the Charioteer by Plato : rhetorical devices

- Rhetorical goals of the authors of African-American history articles

- The effectiveness of the Michelin advertising campaign

- Rhetorical analysis of the Double Cola Company’s image

- Compare the use of argument in Lincoln’s and Dickinson’s works

- Rhetoric analysis of anti-communist and anti-Islam promotion

We hope this article helped you with your assignment. Make sure to tell us what part helped you the most in the comments. And good luck with your studies!

Further reading:

- How to Write a Reflection Paper: Example & Tips

- How to Write a Narrative Essay Outline: Template & Examples

- What Is a Discourse Analysis Essay: Example & Guide

- How to Write a Critical Thinking Essay: Examples & Outline

- How to Write a Precis: Definition, Guide, & Examples

- How to Write a Process Analysis Essay: Examples & Outline

🤔 Rhetorical Analysis Essay Outline FAQs

According to SOAPS, the main 5 elements of a rhetorical analysis are:

1. Subject, or the author’s ideas. 2. Occasion, or the text’s background. 3. Audience, or the people who would find the text interesting. 4. Purpose, or the reasoning behind the writing. 5. Speaker’s characteristics, or the author’s personal beliefs.

1. Logos— the appeal to logic. It includes argumentation, statistics, and facts. 2. Ethos— the ethical appeal. Ethos appeal to the morality and ethical norms of the target audience. 3. Pathos —the appeal to the reader’s emotions. 4. Kairos— the time of the argument.

Every rhetorical analysis ends with a conclusion. A good conclusion should:

1. Restate the thesis. 2. Summarize the points and strategies described in the body paragraphs. 3. End with concluding thoughts on the analysis.

A thesis for a rhetorical analysis is a bit different from the usual one. It needs to include the author’s appeals and the main point the author is trying to make. Like any other thesis, it must structure the further analysis and be connected to every paragraph.

Kairos is the timeliness of the argument. It is the appeal of the right time. The usage of kairos usually means that the author’s text is relevant for a certain period of time only.

- Rhetorical Analysis: Miami University

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay: Formatting: California State University, East Bay

- The Rhetorical Triangle: Understanding and Using Logos, Ethos, and Pathos: Louisiana State University