The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

A decade of research on the rich-poor divide in education

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

Americans like to believe that education can be a great equalizer, allowing even the poorest child who studies hard to enter the middle class. But when I looked at what academic researchers and federal data reports have said about the great educational divide between the rich and poor in our country, that belief turns out to be a myth. Basic education, from kindergarten through high school, only expands the disparities.

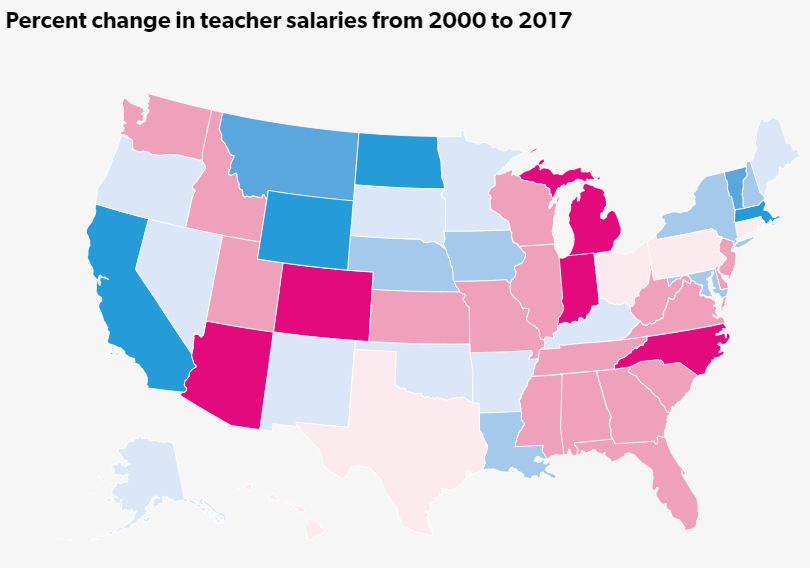

In 2015, during the Obama administration, the federal education department issued a report that showed how the funding gap between rich and poor schools grew 44 percent over a decade between 2001-2 and 2011-12. That meant that the richest 25 percent of school districts spent $1,500 more per student, on average, than the poorest 25 percent of school districts.

I wish I could have continued to track this data between rich and poor schools to see if school spending had grown more fair. But the Trump administration crunched the numbers differently. When it issued a report in 2018 , covering the 2014-15 school year, it found that the wealthiest 25 percent of districts spent $450 more per student than the poorest 25 percent.

That didn’t mean there was a giant 70 percent improvement from $1,500. The Trump administration added together all sources of funds, including federal funding, which amounts to 8 percent of total school spending, while the Obama administration excluded federal funds, counting only state and local dollars, which make up more than 90 percent of education funds. The Obama administration argued at the time that federal funds for poor students were intended to supplement local funds because it takes more resources to overcome childhood poverty, not to create a level playing field.

Rather than marking an improvement, there were signs in the Trump administration data that the funding gap between rich and poor had worsened during the Great Recession if you had compared the figures apples to apples, either including or excluding federal funds. In a follow-up report issued in 2019, the Trump administration documented that the funding gap between rich and poor schools had increased slightly to $473 per student between the 2014-15 and 2015-16 school years.

It’s not just a divide between rich and poor but also between the ultra rich and everyone else. In 2020, a Pennsylvania State University researcher documented how the wealthiest school districts in America — the top 1 percent — fund their schools at much higher levels than everyone else and are increasing their school spending at a faster rate. The school funding gap between a top 1 percent district (mostly white suburbs) and an average-spending school district at the 50th percentile widened by 32 percent between 2000 and 2015, the study calculated. Nassau County, just outside New York City on Long Island, has the highest concentration of students who attend the best funded public schools among all counties in the country. Almost 17 percent of all the top 1 percent students in the nation live in this one county.

Funding inequities are happening in a context of increased poverty in our schools. In 2013, I documented how the number of high poverty schools had increased by about 60 percent to one out of every five schools in 2011 from one out of every eight schools in 2000. To win this unwelcome designation, 75 percent or more of an elementary, middle or high school’s students lived in families poor enough to qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. It’s since gotten worse. In the most recent federal report , covering the 2016-17 school year, one out of every four schools in America was classified as high poverty.

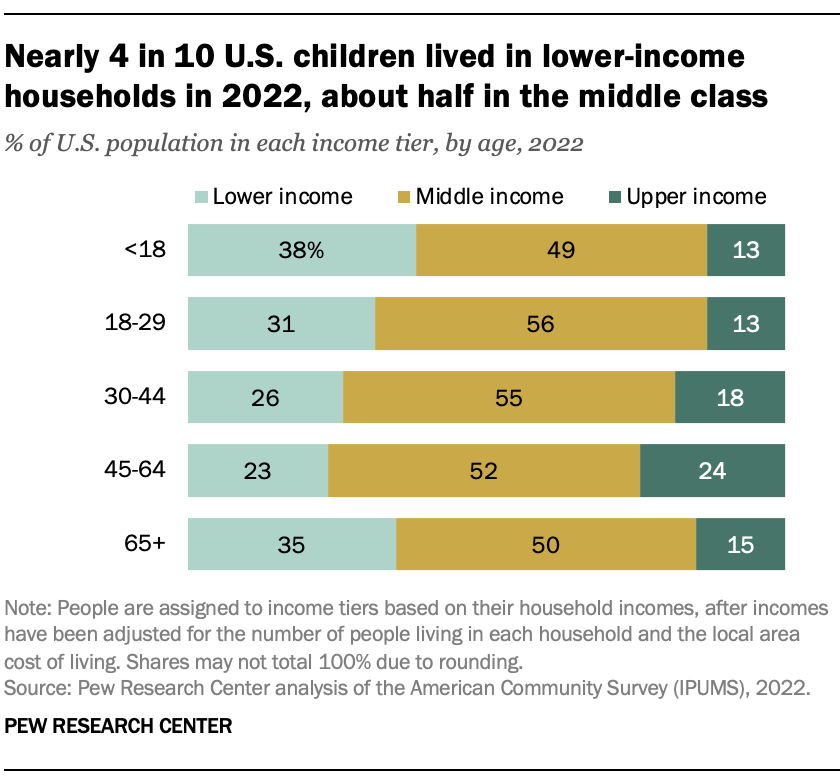

It’s not just that poverty is becoming more concentrated in certain schools; more students in the school system are poor. In 2014, I documented a 40 percent jump in the number of school-aged children living in poverty between 2000 and 2012 from one out of every seven children to one out of every five students. In the most recent report, for the 2016-17 school year, the poverty rate declined from 21 percent in 2010 to 18 percent in 2017. About 13 million children under the age of 18 were in families living in poverty.

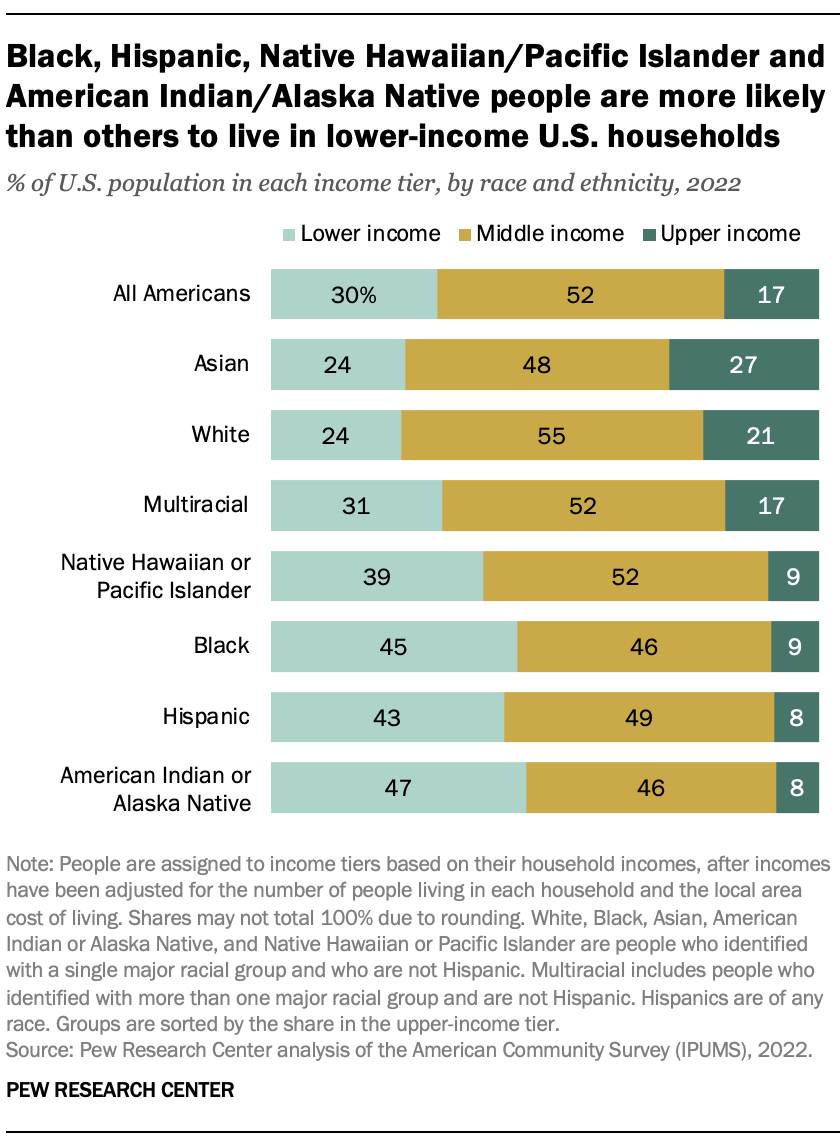

When you break the data down by race, there are other striking patterns. One third of all Black children under 18 were living in poverty in 2016-17, compared with a quarter of Hispanic children. White and Asian children have a similar poverty rate of 11 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

Sociologists like Sean Reardon at Stanford University and Ann Owens at the University of Southern California have built a body of evidence that school segregation by income is what’s really getting worse in America, not school segregation by race. But it’s a complicated argument because Black and Latino students are more likely to be poor and less likely to be rich. So the two things — race and poverty — are intertwined.

In 2019, Reardon studied achievement gaps in every school in America and found that the difference in poverty rates between predominantly Black and predominantly white schools explains the achievement gaps we see and why white schools tend to show higher test scores than Black schools. When white and Black schools have the same poverty rates, Reardon didn’t see a difference in academic achievement. The problem is that Black students are more often poor and attending schools with more poor students. And other than a handful of high-performing charter schools in a few cities, he couldn’t find examples of academic excellence among schools with a high-poverty student body.

“It doesn’t seem that we have any knowledge about how to create high-quality schools at scale under conditions of concentrated poverty,” said Reardon. “And if we can’t do that, then we have to do something about segregation. Otherwise we’re consigning Black and Hispanic and low-income students to schools that we don’t know how to make as good as other schools. The implication is that you have got to address segregation.”

Previous Proof Points columns cited in this column:

The number of high-poverty schools increases by about 60 percent

Poverty among school-age children increases by 40 percent since 2000

The gap between rich and poor schools grew 44 percent over a decade

Data show segregation by income (not race) is what’s getting worse in schools

In 6 states, school districts with the neediest students get less money than the wealthiest

An analysis of achievement gaps in every school in America shows that poverty is the biggest hurdle

Rich schools get richer: School spending analysis finds widening gap between top 1% and the rest of us

This story about education inequality in America written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Jill Barshay SENIOR REPORTER

(212)... More by Jill Barshay

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

Thanks to Jill Barshay for the excellent column reminding us that there is much more to the rich/poor divide in our public schools than just the availability of digital devices and wi-fi. The real problem with equity in education is the lack of equity in school funding, which is an issue both of inequity in society and the ways in which public schools are funded (i.e., primarily local tax revenues).

Other barriers that kept the “school door blocked” for many low income students during this season of remote learning — and, presumably, next school year, as well — include: 1. Some with access to devices and wi-fi have had service disconnected at times due to unpaid (unpayable) bills. 2. Many have no private space in their homes from where to participate in synchronous learning/Zoom calls 3. With loss of family income and no child care, some have work or baby-sitting responsibilities that interfere with participation 4. Deadening effects of online learning cause many low-income students to disconnect and/or “drop out”. 5. In ability to access teacher supports and specialized instruction, esp. for English language learners and children with special needs. 6. Parent inability to assist students with computer routines, glitches, log-ins, etc

As districts address equity in the coming school year, we must also address the modes of learning that we consider both effective and valuable. If the top priority is engaging all students we need high engagement models based in trauma-informed practices, social and racial justice curricula, service learning, interdisciplinary project- and place-based learning, outdoor learning and other innovative ways to make education relevant to all students, regardless of their zip codes. Relax the standards. Cancel high stakes testing. Trust teachers to use their creativity to connect with every student and family. Otherwise, “remote” or “hybrid” learning, regardless of the availability of technology, will only be widening the gaps that structural racism has already created.

Why are we NOT reaching out to the teaching programs started by Marva Collins in Chicago and Ron Clark in Atlanta? Why are we NOT looking at a book called Schools That Work and viewing the achievements and strategies followed by successful programs. Let’s follow successful schools, successful environments in urban, rural, and suburban locations. As an eductor who started teaching in the Ocean-Hill Brownsville area of Brooklyn, N,Y. in 1971, there was a wildcat strike happening and this area was the where decentralization took place in N.Y.C. Rev. Al Sharpton’s church was down the block from I.S. 271. It took 2 years before a no nonsense, BLACK principal, took control over the choas and the movement of 125 teachers going and then coming to this “high poverty” intermediate school. There was stability of staff and the message was, you’re here to learn. I taught there for 7 incredible years and grew to understand what it was like being a minority teacher and human being. I then moved to Columbia, MD. where I lived in a planned community where diversity of color, homes, religions and belief in humanity living together as ONE took place. I taught in a white disadvantaged area for 2 years and observed the same behaviors students exhibited except there was no leadership at the top of this school. Now I teach in a suburban area for the last 31 years with limited diversity and succeeds because of innovative leadership, extraordinary teachers, and pretty high achieving students. Yes, I know every students must have access to technology as a MUST. Yes, I know urban education, rural education, and suburban education do education diffferently. Yes, I know poverty sucks, and I know distant learning may be around for a while. Change must come from the top. Let’s follow the successful educators, the successful programs, the dynamic elected officials who can shake up things so our students, our kids, our educational systems can be the change that can bring poverty to it’s knees.

I live on Long Island and know that whatever is written here about us is true. The Freeport Public School waste millions of taxpayers dollars throwing out teaching equipment, devices books that could be just given to the less fortunate schools next door-Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx; where we see children suffering because of lack of proper learning tools. I am from the Caribbean where l taught for years. Oh l wish we were as privileged as these children. Maybe one day the disparity will end. Hopefully.

I enjoy reading this post. I am currently doing my thesis and the research question is: Do California K-12 public schools in lower-income communities offer the same level of academic curriculum as those in middle-income and wealthy communities? Do you have the reference page for those studies or even any peer reviewers where you got the information? I would like to review those studies and use them for my thesis. Thank you

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Submit a letter

Report | Children

Education inequalities at the school starting gate : Gaps, trends, and strategies to address them

Report • By Emma García and Elaine Weiss • September 27, 2017

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

This report was produced in collaboration with the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education .

What this study finds: Extensive research has conclusively demonstrated that children’s social class is one of the most significant predictors—if not the single most significant predictor—of their educational success. Moreover, it is increasingly apparent that performance gaps by social class take root in the earliest years of children’s lives and fail to narrow in the years that follow. That is, children who start behind stay behind—they are rarely able to make up the lost ground.

Using data from two academic cohorts, the kindergarten classes of 1998 and 2010, this study examines the relationship between children’s socioeconomic status (SES) and their cognitive and noncognitive skills when starting school. We find that large performance gaps exist between children in the lowest and highest socioeconomic-status (SES) quintiles and that these gaps have persisted from the 1998 cohort to the 2010 cohort. The positive news is that the gaps have not grown, even as economic inequalities between these two groups of students have grown. The negative news is that the gaps have not narrowed, despite the fact that low-SES parents have substantially increased their engagement in their children’s early education.

Why it matters: These performance gaps reflect extensive unmet needs and thus untapped talents among low-SES children. The development of strong cognitive and noncognitive skills is essential for success in school and beyond. Low educational achievement leads to lowered economic prospects later in life, perpetuating a lack of social mobility across generations. It is also a loss to society when children’s talents are allowed to go fallow for lack of sufficient supports. The undeniable relationship between economic inequalities and education inequalities represents a societal failure that betrays the ideal of the “American dream.”

What can be done about it: Greater investments in pre-K programs can narrow the gaps between students at the start of school. And to ensure that these early gains are maintained, districts can provide continued comprehensive academic, health, nutrition, and emotional support for children through their academic years, including meaningful engagement of parents and communities. Such strategies have been successfully implemented in districts around the country, as described in this report, and can serve to mitigate the impact of economic inequalities on children’s educational achievement and improve their future life and work prospects.

For further discussion of policy solutions, see the companion to this report, Reducing and Averting Achievement Gaps: Key Findings from the Report ‘Education Inequalities at the School Starting Gate’ and Comprehensive Strategies to Mitigate Early Skills Gaps .

Executive summary

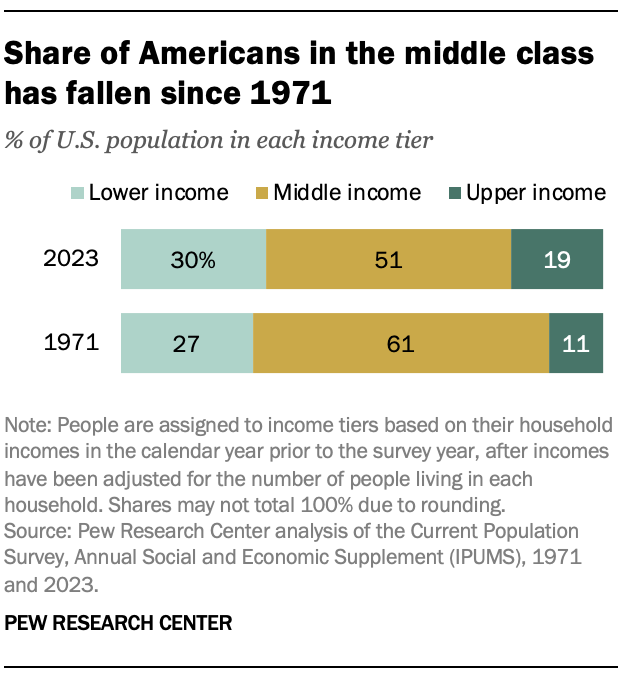

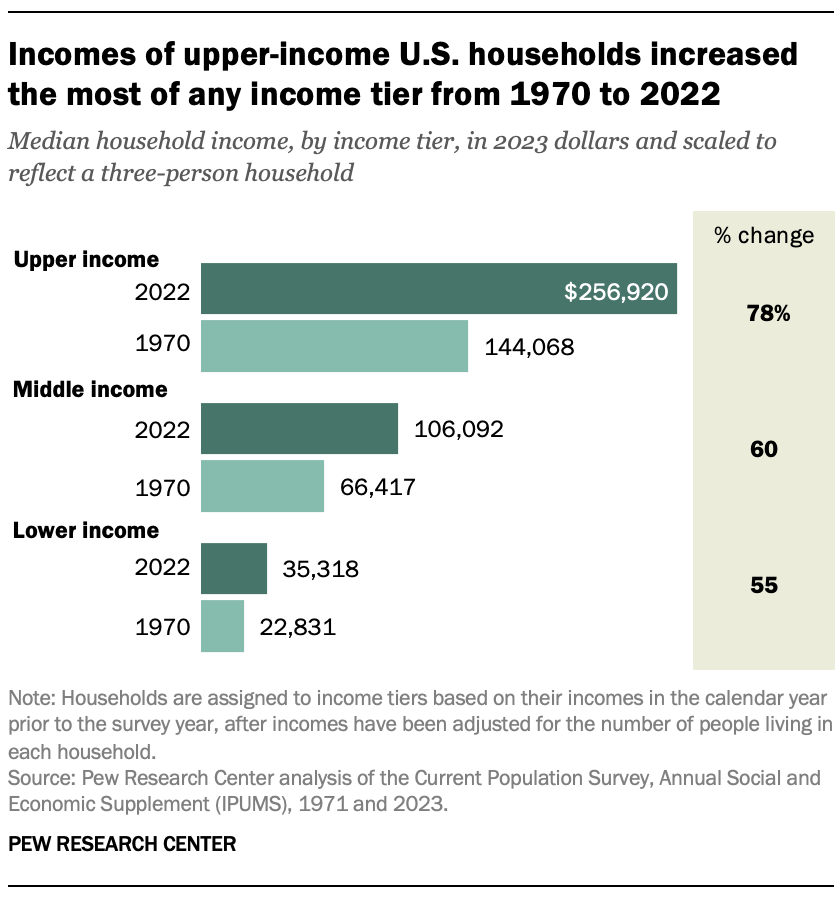

High and rising inequality is one of the United States’ most pressing economic and societal issues. Since the early 1980s, the total share of income claimed by the bottom 90 percent of Americans has steadily decreased, with the majority of income gains going to the top 1 percent. These trends would not be such a major concern if our education system compensated for these inequities by helping level the playing field and enabling children to rise above their birth circumstances.

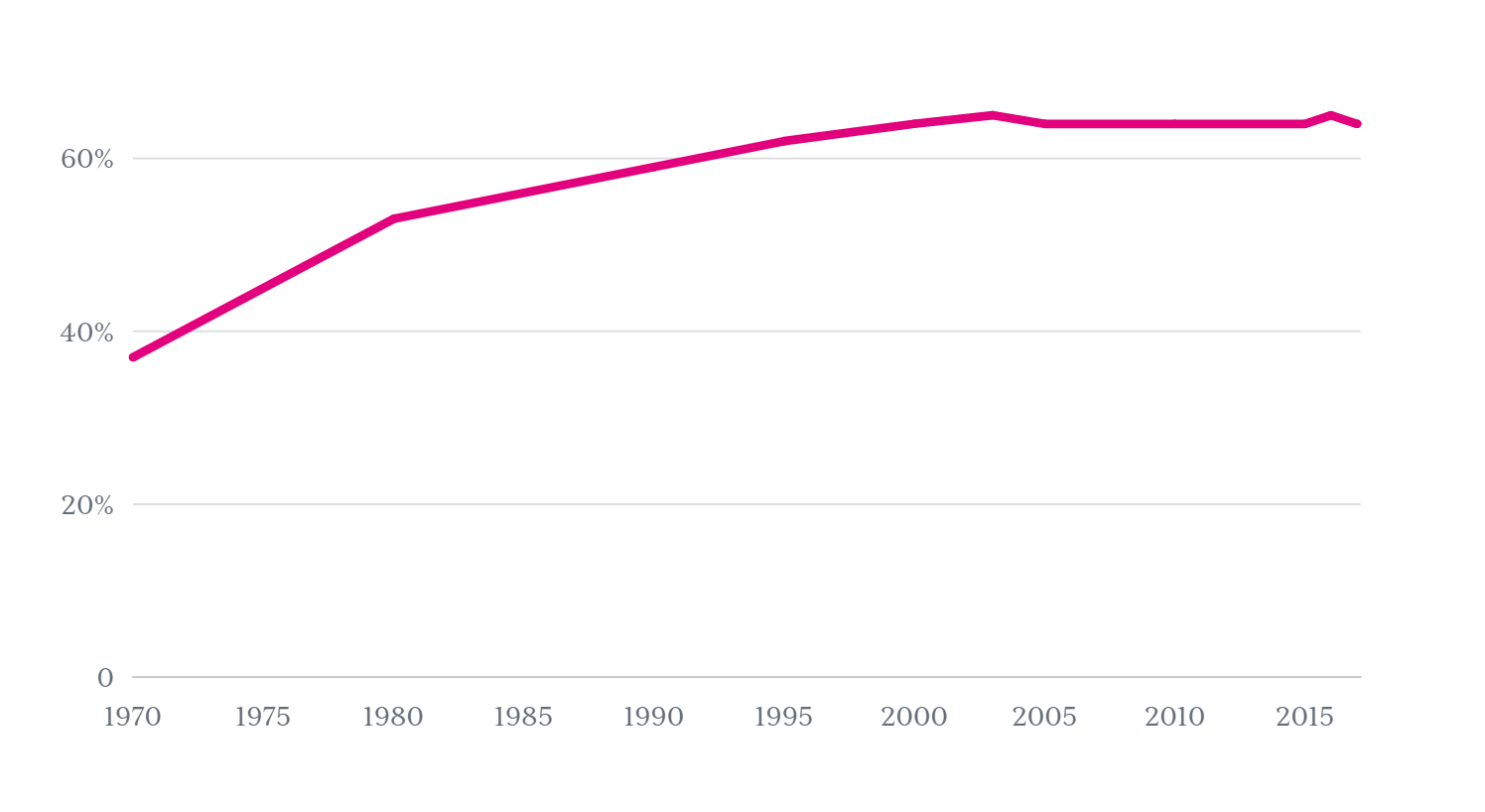

But that is hardly the case. Rather, the fraction of children who earn more than their parents (absolute mobility) has fallen from approximately 90 percent for children born in 1940 to 50 percent for children born in the 1980s. And the tight links between economic inequalities and achievement gaps cast doubt on asserted equality of opportunity that promotes social mobility and puts the “American Dream” within viable reach.

Extensive research has conclusively demonstrated that children’s social class is one of the most significant predictors—if not the single most significant predictor—of their educational success. Moreover, it is increasingly apparent that performance gaps by social class take root in the earliest years of children’s lives and fail to narrow in the years that follow.

Much is known about the determinants and mechanisms that drive early skills gaps among children of different backgrounds, but our failure to narrow social-class-based skills gaps from one generation of students to the next calls for further analysis to determine the degree of influence these factors have and how interventions employed in recent years to address these factors have or have not worked and why. Moreover, shifting economic and demographic landscapes emphasize the need for more robust policy strategies to address the gaps. This three-part study thus combines a statistical analysis of early skills gaps among a recent cohort of children and changes in them over time with a qualitative study of multifaceted, school-district-level strategies to narrow them.

What we do: Questions, data and methodology

In this paper, we:

- Use data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES): the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study of the Kindergarten Classes of 1998–1999 and 2010–2011 to measure gaps in skills by social class. To measure gaps by social class, we use the socioeconomic status (SES) metric (primarily), a composite of information on parents’ educational attainment and job status as well as household income. We compare the average performance of children in the top fifth of the socioeconomic status distribution (high-SES) with the average performance of children in the bottom fifth (low-SES). Skills measured include reading and mathematics, as well as self-control and approaches to learning as reported by both teachers and parents.

- Examine SES-based gaps at kindergarten entry among the most recently surveyed cohort (the kindergarten class of 2010–2011). We study how gaps manifest in both cognitive and so-called noncognitive skills, as both skill types are important components of children’s development.

- Compare these SES gaps with those of an earlier cohort (1998–1999), with a focus on changes in the skills gaps between children in the high- and low-SES quintiles. We also analyze how sensitive gaps are to the inclusion of key determinants of student performance, such as family composition, children’s own characteristics, pre-K participation, and parental and educational practices at home.

- Review a set of 12 case studies of communities that have employed comprehensive educational strategies and wraparound supports to provide more children (especially low-income children) with strong early academic foundations, and to sustain and build on early gains throughout their K–12 school years.

- Based on examples from these diverse communities, we discuss implications: strategies that districts can employ and district and state policy changes to make those strategies easier to adopt and more sustainable. The report ends with conclusions and recommendations for further research, practice, and policy.

What we find

Our quantitative research produces a broad set of findings:

- Very large SES-based gaps in academic performance exist and have persisted across the two most recent cohorts of students when they start kindergarten. The estimated gaps between children in the highest and lowest fifths of the SES distribution are over a standard deviation (sd) in both reading and math in 2010 (unadjusted performance gaps are 1.2 and 1.3 sd respectively). Gaps in noncognitive skills such as self-control and approaches to learning are roughly between one-third and one-half as large (unadjusted performance gaps are about 0.4 sd in self-control, and slightly over 0.5 sd in approaches to learning in 2010).

- SES-based gaps across both types of skills among the 2010 kindergartners are virtually unchanged compared with the prior academic generation of students (the class of 1998). The only unadjusted cognitive skills gap between children in the high-SES and low-SES fifths that changed significantly over this period was the gap in reading skills, which increased by about a tenth of a standard deviation. Gaps in approaches to learning as reported by teachers and in self-control as reported by parents shrank between 1998 and 2010 by roughly the same amount (0.1 sd). Gaps in mathematics, in approaches to learning as reported by parents, and in self-control as reported by teachers did not change significantly.

- This means that though part of the SES gap is attributable to differences in these characteristics and in family investments between children in the high and low parts of the SES distribution, a substantial share of SES-related factors is not captured by these controls, but is important to explaining how and why gaps develop, and thus how to narrow them.

- Moreover, the capacity for these other factors to narrow gaps has decreased over time—as a whole, they accounted for a smaller share of the gaps in 2010 than they had in 1998. This suggests that, while such activities as parental time spent with children and center-based pre-K programs cushion the negative consequences of growing up in a low-SES household, they can do only so much, and that the consequences of poverty are increasingly hard to compensate for. This resistance of gaps to these controls is thus a matter of serious concern for researchers and policymakers alike.

- These children’s likelihood of attending center-based pre-K did not change significantly across generations (about 44 percent for both cohorts: 44.3 percent in 2010 vs. 43.7 percent in 1998). However, in 2010 their parents reported having a somewhat larger number of books at home for the children, and there was also an increase in both indices of activities (literacy/reading activities and other educational and engagement activities).

- In addition to doing more for their children, low-SES parents have greater expectations for their children’s educational attainment—a much smaller share saw them going no further than high school graduation, while a much greater share anticipated their children attaining bachelor’s and even advanced degrees in 2010.

- They were slightly more likely to live with two parents (the share not living with two parents decreased from 11.1 percent in 1998 to 9.6 percent) and to have attended center-based pre-K (the share in center-based pre-K increased from 65.8 in 1998 to 69.9 percent in 2010).

- The share of high-SES homes reporting having more than 200 children’s books slightly increased in 2010, as did parents’ expectations for their children’s educational attainment.

- Although research uses various indicators to measure individuals’ social class, from composite measures such as the socioeconomic status index we use to single indicators such as mother’s education or income, some sensitivity of the results to the indicator used is found. In our analyses, we find that all are equally reliable social-class proxies for the estimation of early achievement gaps, though absolute gaps and trends in them vary slightly depending on the indicator used.

Our qualitative review of community interventions also provides valuable information:

- A growing number of school districts across the country have embraced systems of comprehensive enrichment and supports for many or even all their students, based on the understanding that nurturing healthy child development requires leveraging the entire community. These districts took different approaches to enacting those comprehensive strategies, based on each community’s particular mix of needs and assets, ideological leaning, available sources of funding, and other factors. But all begin very early in children’s lives and align enriching school strategies with a targeted range of supports for children and their families.

- Moreover, school districts embracing what we refer to as “whole-child” approaches to education are seeing better outcomes for students, from improved readiness for kindergarten to higher test scores and graduation rates and narrower achievement gaps. They thus can provide guidance to other districts and to policymakers regarding how to implement such approaches, what to expect in terms of benefits, and which policies at the local and state levels can advance those approaches.

Conclusions

While the persistence of large skills gaps at kindergarten entry is troubling, the fact that, by and large, they did not grow in a generation—despite steadily increasing income inequality compounded by the worst economic crisis in many decades—is a good thing. But we must still be very concerned about these gaps. We would have liked to see evidence that parents’ increased dedication to and investments in their children’s early development, and increased investments in pre-K programs and other early education and economic supports, closed these gaps. However, the data suggest that these efforts simply contained them, and that these positive trends were insufficient to narrow the skills gaps at kindergarten entry. This failure to narrow gaps points to a lack of appropriate policy response at all levels of government, the neglect of decades of research across multiple disciplines on child development, and the resulting waste of critical opportunities to nurture an entire generation of children.

The policy recommendations of this report strengthen the idea that we need much greater investments in pre-K programs and continued comprehensive support for children through their academic years, including meaningful engagement of parents and communities, if we are to substantially improve the odds for disadvantaged children, in light of their extensive unmet needs and untapped talents.

Introduction: Facts about income inequality and its growth over time

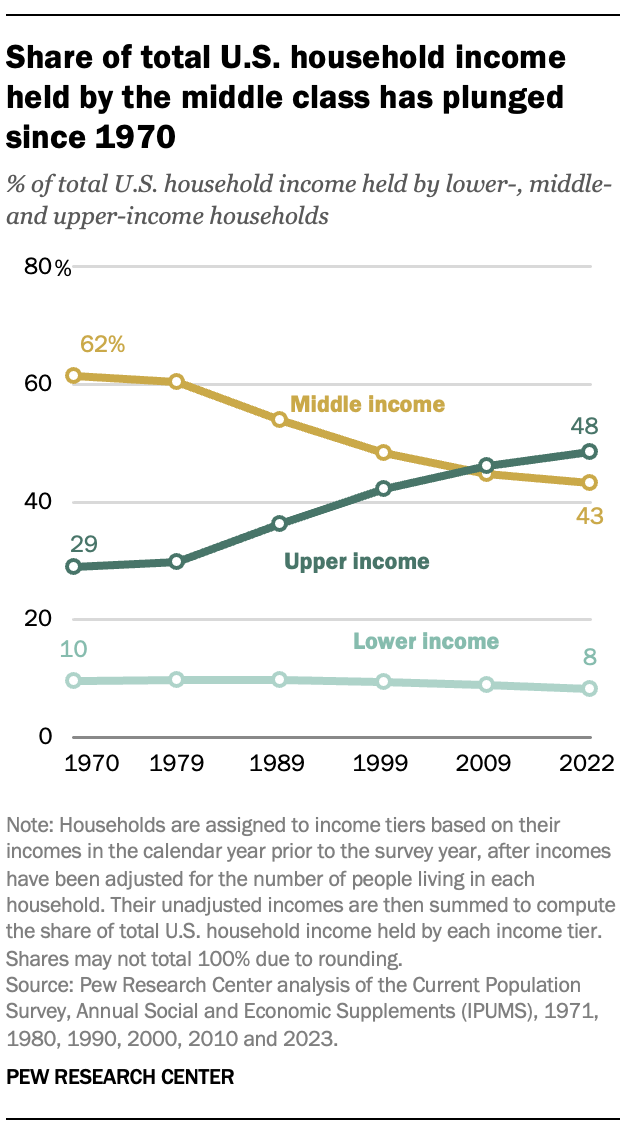

One of today’s most pressing economic issues is the worrisome level of income inequality. Since 1979, the total share of income claimed by the bottom 90 percent of Americans has steadily decreased (Bivens 2016). In 1979, that 90 percent received about 67 percent of cash, market-based income (i.e., pretax income). By 2015, their share had decreased to about 52 percent of pretax income. The majority of income gains during this period went to the top 1 percent (EPI 2013; Mishel and Schieder 2016; Saez 2016). Polls reflect widespread concern about income and wage inequalities and associated trends and the desire for policies to address these inequalities ( New York Times 2015).

Rising inequality might not be such a major concern if our education, economic, and social protection systems acted as compensatory mechanisms, helping individuals, and especially children, rise above their birth circumstances and improve their mobility. But that is hardly the case. Rather, the fraction of children who earn more than their parents (a measure of what social scientists refer to as absolute mobility) has fallen from approximately 90 percent for children born in 1940 to 50 percent for children born in the 1980s (Chetty et al. 2016). Children of certain ethnic and racial minorities who are disproportionately likely to live in concentrated poverty are also more likely to do so over prolonged periods of time (Sharkey 2013). And the close connections between education inequalities and economic inequalities cast doubt on assertions that America provides “equality of opportunities” that promotes social mobility (Mishel 2015).

The influence of income inequality affects multiple aspects of society’s functioning, from health outcomes and even life expectancy to democratic ideals (Putnam 2015; Schanzenbach et al. 2016; Stringhini et al. 2017). In the education arena, children’s socioeconomic status (SES), of which income is a key component, is considered one of the most significant predictors—if not the most significant predictor—of educational success. A number of studies show the strong relationship between social class (of which socioeconomic status is a frequent measure) and test scores, educational attainment, and college attendance and completion (see Duncan, Morris, and Rodrigues 2011; García 2015; García and Weiss 2015; Lee and Burkam 2002; Mishel et al. 2012; Putnam 2015; among others).

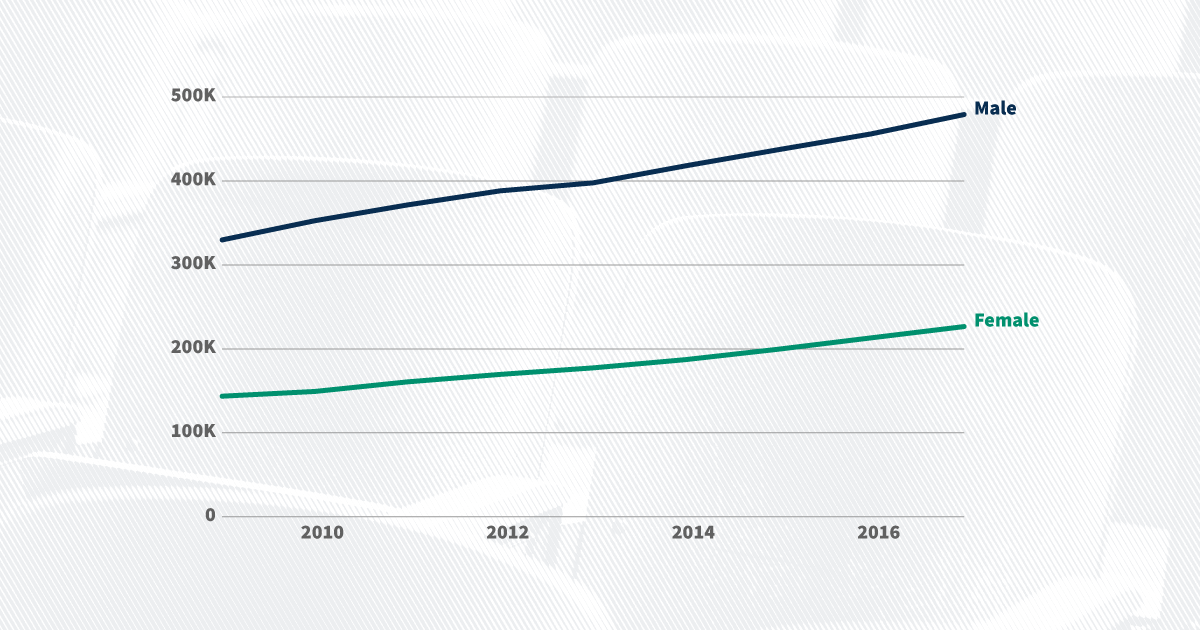

As a result of these trends and associations, achievement gaps by social class have grown substantially since the 1960s, especially between children at the highest end of the income distribution and all of the others (Reardon 2011). Some researchers have identified a large increase in parental investment in education among high-SES parents as one driver of the divergence in education outcomes (Duncan and Murnane 2011), among other contributing factors, such as time parents spend with their children and time parents devote to education-enhancing activities (Morsy and Rothstein 2015; Van Voorhis et al. 2013): Spending on education-enhancing activities by parents in the top income fifth nearly tripled between the 1970s and the 2000s (from $3,500 in 1972 to $8,900 in 2006), while such spending by parents in the bottom income fifth remained low and changed much less (from $800 in 1972 to $1,300 in 2006) (Duncan and Murnane 2011). 1 More time can mean more frequent interactions during playtime, more time spent reading to children, and other parenting practices that contribute to children’s learning and development (Barbarin et al. 2010). In general, more leisure and educational time with children can promote their development and school readiness (Brooks-Gunn and Markman 2005; Hart and Risley 1995; Phillips 2011; Rothstein 2004; Van Voorhis et al. 2013; Waldfogel 2006). Given the evidence that parental engagement and spending directly and continuously translate into improvements in children’s achievement and preparation, the presence of the various achievement gaps are not surprising.

Education researchers and policymakers have long been attentive to issues related to equity—by race/ethnicity, SES, gender, and other characteristics. At least since the 1966 publication of the “Coleman Report” by sociologist James S. Coleman and coauthors, researchers and policymakers have understood the critical impacts of race, poverty, and segregation on educational attainment (Coleman et al. 1966). And educational inequities remain a major problem today. Rigorous research demonstrates that inequalities in both opportunity and outcomes along the lines of race and social class begin early and often persist throughout students’ K–12 years and beyond, and that they are much larger in the United States than in comparable countries (Bradbury et al. 2015; Putnam 2015). Some of the research carefully describes the specific contexts and challenges that minority and lower-social-class students face and how these challenges create early education gaps. Other studies illustrate the consequences of these gaps for children’s later learning and development (Duncan et al. 2007; Duncan and Magnuson 2011). 2 And though this body of research is smaller, a few studies have looked at trends in inequalities across cohorts (Carnoy and García 2017; Magnuson and Duncan 2016; Reardon 2011; Reardon and Portilla 2016), with mixed or inconclusive findings regarding the changes in the gaps. 3 In addition, these latter studies, however, do not address causes that could drive changes in the gaps over time. As such, there is a need both for a better understanding of these causes and for strategies to counter them.

In this paper, we describe recent skills gaps and trends in them by social class, as measured by socioeconomic status; analyze some of the major factors driving the gaps; and explore a set of diverse school district-level initiatives that are helping to narrow gaps. The paper is structured in three sections.

- First, we examine social-class-based gaps at kindergarten entry among the most recently surveyed kindergarten cohort (the kindergarten class of 2010–2011). We study how gaps manifest in both cognitive and so-called noncognitive skills, as both skill types are important components of children’s development.

- Next we compare these gaps with those of an earlier kindergarten cohort. We look at changes from 1998 to 2010 in the skills gaps between children in the top and bottom social-class quintiles (primarily using SES as the proxy for social class). We also analyze how sensitive gaps are to the inclusion of several key determinants of student performance, such as children’s own characteristics, family composition, and parental and education practices at home.

- Then we review a set of case studies of school districts that have employed comprehensive educational strategies to provide more children (especially low-income children) with strong early academic and life foundations, and to sustain and build on early gains throughout the K–12 school years.

- Finally, we look at the implications of our findings, and, based on the case study examples from diverse communities, we discuss strategies that districts can employ along with district and state policy changes that will make those strategies easier to adopt and more sustainable.

For the first two analyses, we use two nationally representative studies from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES): the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study of the Kindergarten Classes of 1998–1999 and 2010–2011. These data provide information about children’s skills and about the children themselves, such as their race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language spoken at home, etc. The data also provide information on the children’s experiences in their early years, such as how actively their parents engaged them in enriching activities, whether they attended prekindergarten care, and the number of books the child has (see Appendix A). This information allows us to test the associations between children’s characteristics and their educational outcomes at school entry. For the second analysis, we draw on 12 case studies of community and school districts employing comprehensive educational strategies (Weiss 2016a–h). We explore the qualitative information provided on investments these districts have made in early childhood education, on both within-school and broader K–12 supports for children, and on evidence that these investments are delivering both improved academic achievement and broader gains for children. Based on this evidence, the report ends with conclusions and recommendations for further research, practice, and policy. Appendices A and B provide detailed discussions of the data and methodology used in this paper.

How large are recent performance gaps at kindergarten entry?

This section documents inequalities among the most recently tracked cohort of students as they entered kindergarten in 2010. It provides us with the most recently available view of the various aspects of gaps at the school starting gate, all of which are critically important for understanding the implications of those gaps. The findings below draw on the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study of the Kindergarten Class of 2010–2011, and we use data from the fall measurement in the kindergarten year. (This section partly builds on our previous work; see García 2015 and García and Weiss 2015. See Appendices A and B for details on the variables and methodology used.)

Our decision to examine performance in both cognitive and noncognitive skills reflects growing acceptance that children’s development is a complex process in which both skill types build on and interact with each other, and on evidence of the roles that both types of skills play in the education process and adulthood outcomes (see García 2015; García and Weiss 2016; Levin 2012a, 2012b). Traits and skills such as critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, persistence, and self-control are vitally important to children’s full development, and are nurtured through life and school experiences. These skills, sometimes referred to as noncognitive or social and emotional skills, tend to develop—or lag—in tandem with cognitive skills. Noncognitive or social and emotional skills are thus linked to academic achievement, and also to outcomes in adult life, such as productivity and collegiality at work, good health, and civic participation.

For these analyses, we use a measure of socioeconomic status that has three components: the educational attainment of parents or guardians, parents’ occupational prestige (determined by a score), and household income (see more details about the SES construct in Tourangeau et al. 2013, 7-56 to 7-60). We divide children of the 2010–2011 kindergarten class into five groups based on SES quintile. To measure the gaps in performance by socioeconomic status, we compare the average performance of children in the top fifth of the SES distribution with the average performance of children in the bottom fifth. This provides an estimate of the relative advantage of a child in the top fifth of the SES distribution (referred to in this report as “high-SES”) with respect to a child in the bottom fifth (“low-SES”).

Children are not equally prepared for school when they enter kindergarten, and our analyses show that students’ social class strongly determines their relative position in the performance distribution. Most socioeconomically disadvantaged children lag substantially in both reading and math skills, and these skills levels rise along with socioeconomic status (sometimes referred to as socioeconomic gradients). Children in the highest socioeconomic group score significantly higher in reading and math than children in the lowest socioeconomic group. As Table 1 shows, the relative unadjusted gaps in reading and math, i.e., the advantages of high-SES children relative to low-SES children in 2010 are 1.17 and 1.25 sd, respectively (Table 1 also shows that, after controlling for clustered data, the gaps are 0.94 and 0.91 sd, respectively). 4 Reading and math skills advantages of children in the middle of the SES distribution relative to the lowest SES group are roughly half as large as the advantages of high-SES children to the lowest SES group. 5

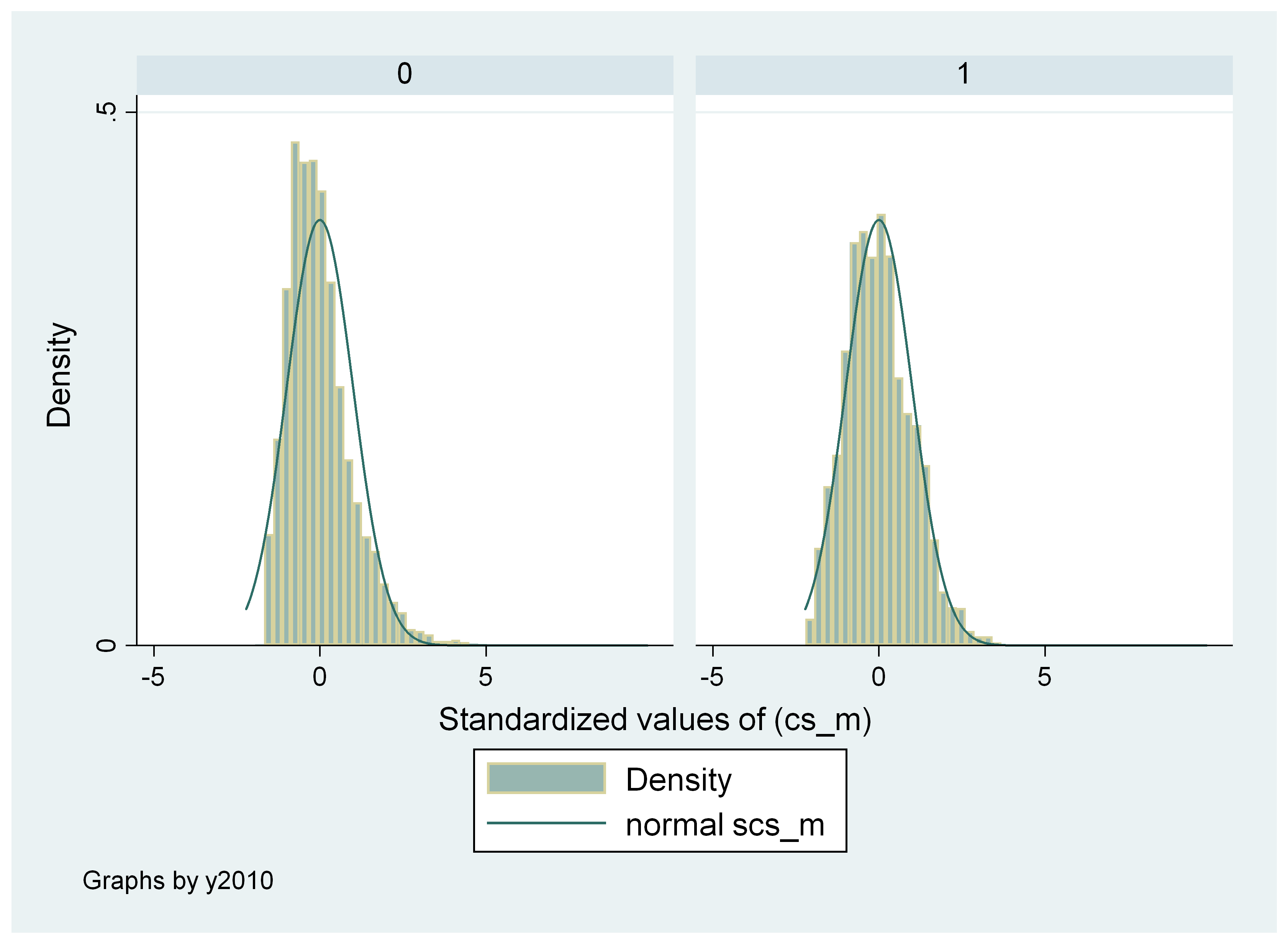

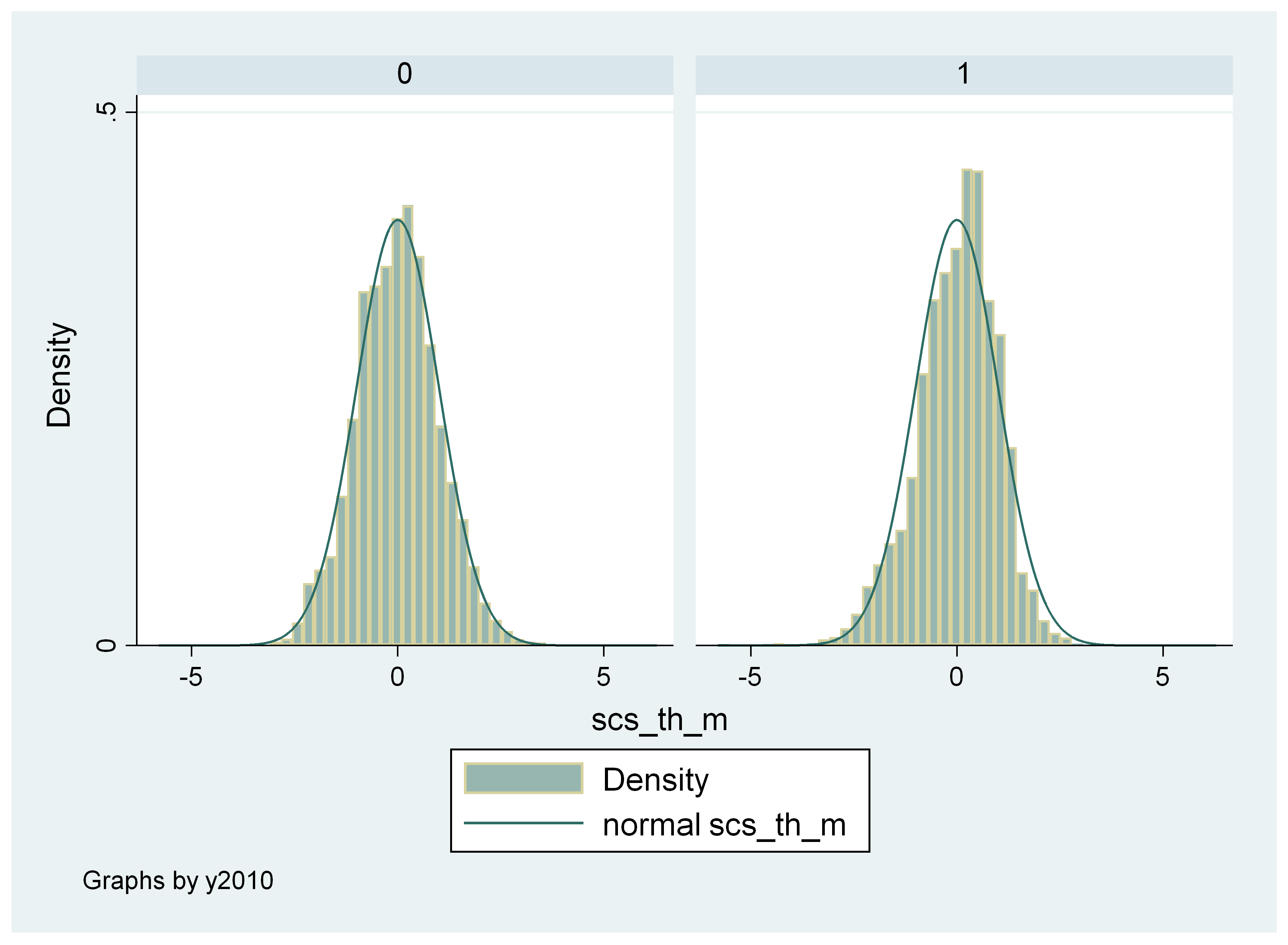

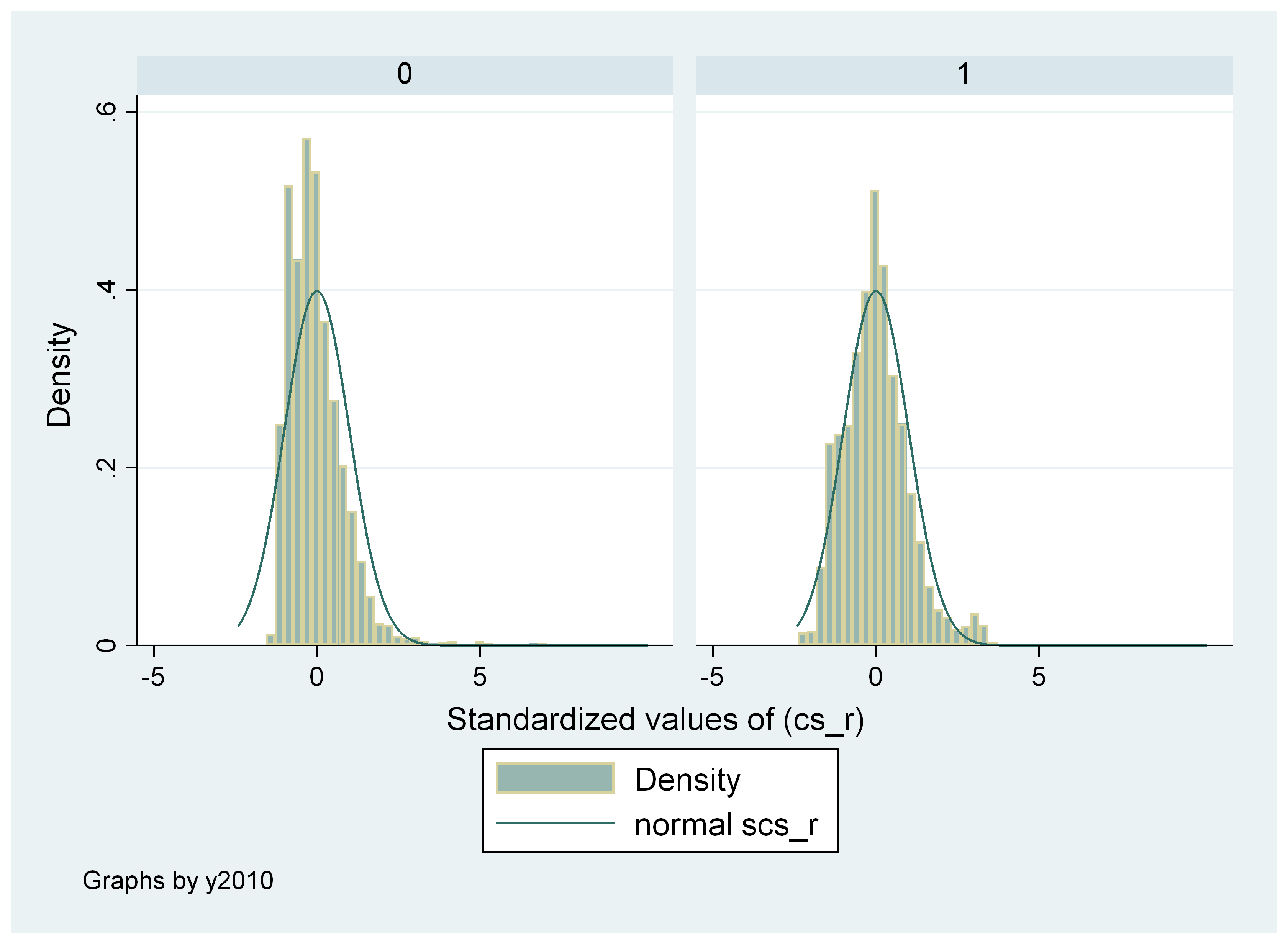

Children in the lowest socioeconomic quintile also lag substantially in noncognitive skills, based on assessments by both parents and teachers, although these gaps are smaller than those in reading and math. Socioeconomic-based gaps in self-control and approaches to learning are approximately one-third to one-half as large as gaps in reading and math. 6 In 2010, children in the high-SES quintile scored 0.38 sd and 0.51 sd higher in self-control and approaches to learning as reported by teachers (0.36 sd and 0.56 sd after clustering; see Table 1) than children at the low-SES quintile (see Figure A ). Using parents’ assessments of the same skills, the gaps are 0.39 sd and 0.56 sd, respectively (0.33 sd and 0.46 sd after clustering; see Table 1).

Our analyses also document stark socioeconomic disparities in inputs, child and family characteristics, and other factors that can affect school readiness ( Table 2 ). Here too we find a correlation between socioeconomic status and other factors that impede educational development. Low-SES students are more likely than their high-SES peers to be immigrants and less likely to speak English at home, to live with two parents, to have participated in center-based pre-K care activities in the previous year, and to have engaged in early literacy practices at home. Among children in the low-SES group, half (50.4 percent) are Hispanic, 23.1 percent are white, 19.6 percent are black, and 2.5 percent are Asian. 7

Though these gaps in both cognitive and noncognitive skills are troubling and call for policy recommendations, better policy solutions can be designed if we understand how these gaps have changed over time and what factors have played a role in those changes. Education outcomes are the product of a combination of multiple factors, which can reinforce or mitigate relative advantages or disadvantages in a dynamic fashion. We examine these issues in the rest of the paper.

How do the performance gaps in the 2010–2011 kindergarten class compare with the gaps in the prior generation?

The analyses presented in this section compare the inequities in inputs and the performance gaps between high-SES and low-SES students who began kindergarten in 2010 with the gaps among high-SES and low-SES schoolchildren in the prior academic generation, the 1998 cohort. We also analyze factors that have had major influences on the changes in performance of kindergartners, and briefly discuss the research and policy implications of our findings.

How have the characteristics of the children in the lowest and highest SES groups changed in a generation?

We first analyze children’s characteristics by SES quintiles in the two cohorts. This enables us to identify differences in the characteristics of low-SES kindergartners in 2010 versus in 1998. These changes may help explain why the performance gaps we are studying grow or shrink (for example, if children in the low-SES quintile in 2010 were more likely than their 1998 peers to have access to public programs such as pre-K, they might be more prepared for kindergarten, and thus the relative advantage of high-SES children might shrink). 8

Table 2 shows the student and family characteristics of the kindergarten classes of 1998–1999 and of 2010–2011, by SES quintile. The table also includes pre-K care arrangements and two indices of developmental activities parents undertake with their children—indices of “literacy/reading activities” and “other activities”). 9 The table also summarizes parents’ expectations regarding their children’s educational attainment. To some extent, expectations are based on hope, but they can also respond to behavioral patterns children are exhibiting that hint at their future success. Expectations can also influence outcomes by representing how motivated parents are for their children’s education. The ECLS-K survey does not ask parents how their expectations (and changes in their expectations) affect their provision of educational activities or support, but their answers to the expectations question can be used as a reasonable proxy of the degree to which parents are aware of their children’s education and willing to support it. 10

The most significant changes in children’s characteristics by SES quintile are for children in the bottom of the distribution. In 2010, a greater share of children in this group are Hispanic (50.4 percent, an increase of 10.6 percentage points relative to the 1998 share of 39.8 percent), live in homes where the main language is not English (40.3 percent, an increase of 9.1 percentage points from 31.2 percent in 1998), and are immigrants (49.8 percent, an increase of 19.5 percentage points from 30.3 percent in 1998). In 2010, a greater share of children do not live with two parents (54.9 percent, an increase of 9.3 percentage points from 45.6 percent in 1998), and live in poverty (84.6 percent, an increase of 13.3 percentage points from 71.3 percent in 1998). These substantially greater disadvantages for children at the bottom of the SES scale could all be reflections of both the much weaker national economic context in 2010 versus 1998 and the growing inequality described above.

These children’s likelihood of attending center-based pre-K did not change significantly across generations (about 44 percent for both cohorts), but they were more likely to be looked after by parents or relatives (with the share increasing from 46.4 percent in 1998 to 50.9 percent in 2010). These children’s parents also reported having a somewhat larger number of books at home for the children, and there were increases in their indices of educational and engagement activities (two composite measures, with the literacy/reading index measuring how frequently parents read books to their child, tell stories, sing songs, and talk about nature and how frequently the child reads picture books and reads outside of school, and the “other” index measuring how frequently parents and children play games or do puzzles, play a sport or exercise together, and build something or play with construction toys; and how often parents help children do arts and crafts and involve children in household chores). These parents’ expectations about their children’s educational attainment also changed significantly: the share who expected their children to attain no more than a high school diploma decreased by more than half (from 24.1 percent in 1998 to 11.4 percent in 2010), and the share of parents who expected their children to attain at least a bachelor’s degree increased, markedly for those expecting their children to obtain an advanced degree (a master’s degree, Ph.D., or M.D.).

Among children in the high-SES quintile, the group in 2010 includes a lower share of white children (falling from 78.8 percent in 1998 to 71.3 percent) and a larger share of Asian children (increasing from 4.7 percent in 1998 to 8.7 percent). Children in the high-SES group became slightly more likely to live with their two parents (the share of children who lived with one parent decreased from 11.1 percent in 1998 to 9.6 percent), and to have attended center-based pre-K (65.8 percent in 1998 and 69.9 percent in 2010). We only see a small increase in the reported number of books at home. 11 The share of homes reporting having more than 200 books—the maximum—increased slightly in 2010, across all SES quintiles except for the middle quintile). As was true of low-SES parents, those in the highest quintile raised their expectations for their children’s educational attainment from 1998 to 2010. Compared with the 1998 cohort, a larger proportion of high-SES children in the 2010 cohort were expected by their parents to attain an advanced degree (master’s degree or higher), while a lower share expected their children to attain a bachelor’s degree only.

How did the performance gaps between the children in the lowest and highest SES groups change in a generation?

Changes over time in the input factors by socioeconomic status (child and family characteristics, early-education practices, and parents’ expectations) explored above have been found by researchers to have major impacts on the outcomes (test scores on reading and math, and measures of noncognitive skills) explored in this section. 12 In other words, we would expect that changes in the unadjusted skills gaps (gap measures that do not include controls for child and family characteristics, early-education practices, and parents’ expectations) would partially reflect the compositional differences between the class of 2010–2011 and the class of 1998–1999. For example, we would anticipate that if the more recent generation’s low-SES parents read to their children more frequently, helped them do more arts and crafts, or had higher expectations for them, these factors would correlate with narrowing skills gaps. Also, we would expect that the adjusted skills gaps (gap measures that are net of the influence of child and family characteristics, early-education practices, and parents’ expectations, and thus reflect the SES gaps) would be different for the two cohorts if the correlations between inputs and outcomes had changed over time or if the share of children’s outcomes the adjustments account for had changed over time.

To understand these factors’ potential influence on gaps, we examine both unadjusted and adjusted gaps in the tables in this section. We also examine gaps by some of the components of the SES index, such as household income or mother’s educational attainment, and by other variables that are sometimes used as proxies of the child’s socioeconomic background, such as number of books in the home. If the gaps by SES components and proxies somewhat differ, this tells us that researchers’ choices about how to divide children into groups and compare them matter—both for their findings and for their policy recommendations.

Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted gaps between the standardized scores in reading and math of kindergarten children in the top SES quintile relative to the bottom SES quintile in 1998 and the change in that gap by 2010. 13 Table 4 performs the same analysis for gaps in measured noncognitive skills. The tables show two somewhat perplexing patterns. On the one hand, the cognitive and noncognitive skills gaps between high-SES and low-SES children are large and statistically significant in both cohorts. But while significant social-class-based performance gaps persist from one kindergarten generation to the next, there is not the same consistency in how the high-SES to low-SES gaps change. For some cognitive and noncognitive skills, the performance gaps grow, while for others the gaps shrink, or remain the same from one generation to the next (which may complicate the process of understanding why performance gaps have changed over time).

Beginning with our unadjusted model (data column one), the only substantial increase in the gap between high- and low-SES children from 1998 to 2010 was in reading skills, which increased by one-tenth of a standard deviation. There were no significant changes in gaps in math skills, which, as the literature indicates, are less sensitive than reading skills to parents’ activities at home (see Rothstein 2004, 2010). Similarly, gaps in approaches to learning as reported by parents and in self-control as reported by teachers did not change significantly, and gaps in approaches to learning as reported by teachers and in self-control as reported by parents shrank by roughly the same amount as the reading gap (about a tenth of a standard deviation—0.12 and 0.08 sd, respectively). Figure A provides a graphic illustration of the unadjusted gaps in cognitive and noncognitive skills of high- and low-SES children across the two cohorts.

The additional models estimated for each outcome and shown in Tables 3 and 4 offer other key findings. In Model 1, we used the full samples for the two cohorts but did not include any controls that capture characteristics of children or their parents or the early education practices in which families engage. Model 2 partitions the data into schools and classes, or clusters, so that the subjects in the clusters are more similar to one another than to those in other groups. Under this adjustment, the gaps shrink substantially, by between 15 and 25 percent across the skills, and the regression fit improves significantly (see increased adjusted R-squared, i.e., this model explains more of the total variation in the outcomes than the first model). This clustering takes into account school segregation, that is, that children are not randomly distributed but tend to concentrate in schools or classrooms with children of the same race, social class, etc. Clustered estimates provide a comparison of the skills gaps of peer students—those in the same schools and classrooms—rather than a comparison across schools. García (2015) and Magnuson and Duncan (2016) offer these estimates too.

How do child and family characteristics, activities, and expectations affect SES-based performance and performance gaps?

We next examine the contribution of the certain variables of interest to SES-based performance gaps. We approach this in two ways. First, we examine the changes in the gaps (Tables 3 and 4, Models 3 and 4) and the overall reduction in the gaps that results from controlling for children and their family characteristics, early literacy practices, and parental expectations of educational achievement ( Table 5 ). Second, we assess the influence of select early educational practices on performance and how that influence has changed over time by looking at the associations between these inputs and performance ( Table 6 ).

Models 3 and 4 in Tables 3 and 4 use the samples that result from removing observations without full information for the controls of interest. 14 Adding controls is important because performance gaps based on socioeconomic status may be explained by differences in variables other than the child’s socioeconomic status. In other words, we aim to determine which part of the gap is attributable to children’s SES, net of other factors that matter for performance. Thus, in the third data column (Model 3), we add controls for individual and family characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, whether English is the primary language spoken at home, disability, age, whether children live with two parents) and early educational and play activities (center-based pre-K care, indices for literacy/reading activities and other activities, and total number of books the child has). Model 3 also includes the interactions between the early education variables with time. 15 In the fourth data column (Model 4), we control for the same factors as in Model 3 but add controls for parental expectations of children’s educational attainment (whether they expect their children’s highest level of education attained will be high school diploma or less, some college or vocational studies, bachelor’s degree, or advanced degree) and their interaction with time. 16 We describe these results in the next section.

Including covariates changes the estimates of SES-based skills gaps in various ways. First, the gaps between the top- and bottom-SES quintiles shrink, showing that SES-based gaps are partially explained by the variation in the controls (which is not visible in the tables). 17 Second, controls do not significantly change the SES-based gaps over time, in general; i.e., the coefficients associated with changes in the gaps between high- and low-SES children remain almost the same, or change very minimally, depending on the skill measured. The statistical significance of the SES-based skills gaps in 1998 is not affected by the inclusion of the controls (see rows “Gap in 1998–1999” in tables), but the statistical significance of the changes in the gaps between 1998 and 2010 (see rows “Change in gap by 2010–2011” in tables) is somewhat affected by the inclusion of the controls (note that the sizes of the coefficients measuring gaps in 1998 change after the inclusion of the controls, but that the sizes of the coefficients measuring changes in them between 1998 and 2010 do not change significantly). In reading, the change in the gap between 1998 and 2010 diminishes and becomes statistically insignificant in the last model (the relative gap increases by 0.08 sd but this change is not statistically significant), meaning that adding parental expectations of education accounts for some of the increase in the gap detected in Models 1 to 3. The only SES-based skills gap that shows a statistically significant increase from 1998 to 2010 once parental expectations are controlled for is the gap associated with parents’ assessment of approaches to learning, which increases by 0.11 sd. Gaps between high- and low-SES children in cognitive and noncognitive skills after adjustments are made are shown in Figure B .

As mentioned above, the fact that the skills gaps decrease after controls are taken into consideration affirms that SES-based gaps are due in part to variation in the controls among high- versus low-SES children. This trend can be seen in Table 5, which, as noted above, shows the overall reduction in gaps that results from controlling for child and family characteristics, early literacy practices, and parental expectations of educational achievement. With respect to cognitive skills, the 1998 gaps shrink by 46 percent and 53 percent, respectively, after the inclusion of the covariates. About half of the gaps are thus due to other factors that are associated both with SES status and with the outcomes themselves. The reduction in the 1998 gaps for noncognitive skills varies from 28 percent (approaches to learning as reported by teachers) to 74 percent (approaches to learning as reported by parents). (For self-control as reported by teachers, the reduction is 51 percent versus 35 percent when reported by parents.)

While the gaps hold after the inclusion of controls across outcomes, gaps in 2010 are less sensitive to the inclusion of the covariates than they were in 1998. This trend can also be seen in Table 5. 18 Declining values from 1998 to 2010 indicate that factors such as early literacy activities and other controls are not, as a group, explaining SES-based gaps as much as they had a decade prior. This change could be due to the failure of the index to fully capture parents’ efforts to nurture their children’s development and/or the index becoming somewhat out-of-date. In any event, the resistance of gaps to these controls should worry researchers and policymakers. The waning influence of these controls makes it harder to understand what drives SES gaps. It also suggests that the gaps may be growing more intractable or, at least are less easily narrowed via the enactment of known policy interventions.

Finally, we examine the association of performance outcomes (not performance gaps) with selected early educational practices, including having attended center-based pre-K, literacy/reading activities and other activities, and total number of children’s books in the home (Table 6). 19 We are mainly interested in two potential patterns: whether these factors are associated with outcomes (and, if so, how intense the associations are), and whether the relationships have changed over time.

In keeping with established research, having attended center-based pre-K is positively associated with children’s early reading and math skills. For 1998, the estimated coefficients are 0.11 sd for reading skills and 0.10 sd for math skills, substantial associations that do not change significantly over time. In other words, attending pre-K in 1998 improved kindergartners’ reading skills by 0.11 sd and improved kindergartners’ math skills by 0.10 sd relative to not attending pre-K. However, while center-based pre-K continues to reduce self-control as reported by teachers in 2010, the effect is less negative in 2010 (the 0.06 improvement from 1998 to 2010 shown in the bottom panel of the table shows us that the effect in 2010 was -0.07 [-0.13 plus 0.06], compared with -0.13 sd in 1998). We find no independent effect of center-based prekindergarten schooling (i.e., no effect in addition to SES, in addition to other individual and family characteristics, or in addition to other SES-mediated factors), on approaches to learning or on self-control as reported by parents. 20

The number of books children have at home likewise supports their skills at the beginning of kindergarten. Indeed, this factor is positively associated with all outcomes but self-control reported by parents. The coefficients are very small, of about 0.01 to 0.02 sd (associated with changes in outcomes for each 10 additional/fewer books the child has, as expressed by the continuous scale with which number of books in the home is measured, which is divided by 10 for the analyses (as mentioned in Appendix A), and these relationships do not change over the time period.

The two types of parenting activities that are summarized by the indices “reading/literacy activities” and “other activities” show interesting correlations with performance and patterns over time. On the one hand, the “reading/literacy activities” index (a composite of how frequently parents read books to their child, tell stories, sing songs, and talk about nature, and how frequently the child reads picture books and reads outside of school) is strongly and positively associated with all outcomes other than children’s self-control as reported by the teacher. The associations with cognitive skills, especially with reading, are strong and statistically significant—0.17 sd for reading performance and 0.07 sd for math—and these associations did not change significantly between 1998 and 2010. For noncognitive skills, the relationships are strong for those assessed by parents, though they shrink by about half over time: self-control is 0.14 sd in 1998 and decreases by 0.08 sd by 2010; approaches to learning is 0.32 sd in 1998 and decreases by 0.17 sd by 2010). The relationship is much weaker, though still statistically significant, for teachers’ assessed approaches to learning (it is 0.03 sd in 1998 and does not change significantly by 2010).

On the other hand, the index that measures other enrichment activities that parents do with their children (a composite of how frequently parents and children play games, do sports, build things, work on puzzles, do arts and crafts, and do chores) shows significant correlations with all of the skills, but they may be either positively correlated or negatively correlated, depending on the skill. For cognitive skills, the associations are statistically significant and negative, though stronger and somewhat more meaningful or more intense with reading achievement (-0.12 sd in 1998) than with math achievement (-0.04 sd). 21 These associations did not intensify nor weaken over time. For noncognitive skills the associations are highly positive and statistically significant, and very strong for parents’ assessment of approaches to learning (0.29 sd in 1998). As explained by García (2015), these correlations between “other activities” and noncognitive skills as assessed by parents could be bidirectional: engaging children in enrichment activities might enhance their noncognitive skills, but, at the same time, parents who are more inclined to participate in their children’s early play and educational time are probably more likely to perceive or judge that their engagement has an impact on their children’s skills. But the fact that both the frequency with which parents engage in most of these activities and the importance of this index for parent-assessed skills increased noticeably from 1998 to 2010 (by 0.22 sd for self-control and 0.27 sd for approaches to learning) suggests that parents are growing more informed and involved in their children’s early education over time. It also indicates that parents are increasingly acting on this knowledge and that this involvement will continue to grow, albeit potentially with decreasing marginal returns to time and resources invested. The association between “other activities” and teachers’ assessments of children’s noncognitive skills is also positive but weaker than that of parents’ assessments (about 0.03 sd for approaches to learning and 0.05 sd for self-control), and remained unchanged during the time period studied.

Finally, we find a strong association between parental expectations for their children’s educational attainment and all measured skills. In other words, net of socioeconomic status, the higher the expectations, the higher cognitive skills children have, and the higher the assessments by parents and teachers of children’s noncognitive skills. The parental expectations portion of the table measures children’s performance relative to children whose parents’ expectations are the lowest (high school diploma or less). While the expectation that a child will pursue some vocational education or complete college has a statistically positive influence on all skills measures except for reading, the expectation that their children will complete a bachelor’s degree or more education has a stronger influence, including on reading skills: between 0.11 to 0.16 sd higher in reading and between 0.17 to 0.22 sd higher in math in 1998. High expectations for children’s educational attainment also have a statistically positive effect on noncognitive skills. When the expectation is for an advanced degree (master’s or higher), coefficients vary from 0.12 sd in self-control by teachers to 0.38 sd in approaches to learning by parents in 1998. In addition, most of these associations—particularly the cognitive gradients—grow in 2010. Relative to children whose parents have low expectations, children whose parents have the highest expectations for their children’s attainment (graduate studies) perform much better in reading and math than in 1998 (relative gaps grow by 0.19 and 0.12 sd respectively). A similarly stronger association is noted for noncognitive skills assessed by teachers (though not for parents’ assessments of their children’s skills).

Sensitivity analyses: Do performance gaps vary based on which proxy for social class (socioeconomic status) is used?

Part of the challenge to making conclusive statements about trends in education gaps by social class is the existence of multiple valid proxies for measuring children’s social class or socioeconomic status. 22 Although researchers treat these proxies as equivalent, and even interchangeable, the lack of a comparison of results obtained using various indicators limits our capacity to extract major conclusions on social-class trends and their drivers, and hence hinders the plausibility and effectiveness of the policy recommendations that build on any specific indicator’s findings (net of other methodological and instrumental differences that may exist across studies).

We thus conduct analyses using several of the main proxies employed to measure socioeconomic status. The purpose of these analyses is twofold. The first purpose is to test the sensitivity of the estimated relative gaps, and of trends in them, to changes in the measurement of this key predictor of education performance. (In other words, if all the indicators are reliable proxies of SES, gaps and trends obtained using the various metrics should be similar.) The second purpose is to increase the comparability of the results of studies addressing trends in education inequalities that use various metrics of social class. This is an important issue; in addition to helping reconcile diverse results found in the literature, these analyses may reveal why patterns differ, and have significant policy implications.

As such, instead of the SES composite measure we use to estimate SES-based gaps in this report, we use three alternative indicators to run our analyses: mother’s educational attainment, household income, and number of books the child has in the home. Unlike the SES composite measure, two of these measures offer the advantage of being directly comparable over time. Both mother’s educational attainment and number of books the child has are objective categories. As a limitation, and mainly associated with the information that is available in the raw data, none of these categories can be transformed into a percentile-variable without major transformations. (The adjustments to ensure comparability over time are explained in Appendix A. See Reardon and Portilla 2016 for an analysis with a transformation of the income variable that offers a proper percentile comparison, based on the methodology developed by Reardon 2011.) Still, they are variables associated with social class and can be ordered in groups or categories that identify high- and low-social-class statuses. Thus, with the necessary caution when interpreting and using the findings, we offer this comparison of results as a sensitivity analysis.

We create five categories with these indicators, maintaining the structure of comparing “high-SES” (top quintile) with “low-SES” (bottom quintile) as in Tables 1–5 (note that we are using “SES” interchangeably with “social class” here). For simplicity, Tables 7–9 show only the results from two models: one without covariates (Model 1, baseline estimates) and one with all covariates (Model 4, fully adjusted estimates). We focus on the findings for the baseline relative gaps in 1998 and 2010 first ( Figures C–E ). The overall patterns found in the results suggest that all social-class gaps are statistically significant and sizable. However, the exact sizes of the gaps vary depending on the social-class indicator used and the outcome being assessed. Also, the changes in the gaps over time vary depending on the indicator used to capture children’s social class.

In addition to these general findings, we note some more detailed ones. For 1998, gaps by mother’s educational attainment (Figure C; Table 7) are the largest across all indicators (except for the gap in self-control as assessed by teachers, which is slightly smaller than the gaps as measured using household income and number of books the child has), while gaps by number of books (Figure E; Table 9) are the smallest across all indicators (except for the gap in approaches to learning as assessed by parents, which is slightly larger than the gap for household income). Again, according to the 1998 data, the coefficients of gaps by mother’s educational attainment are generally larger—and in three cases much larger—than those obtained using number of books in the home as the indicator of social class. For example, the relative gap is 1.29 sd in reading and 1.46 sd in math when mother’s education is the SES proxy, compared with gaps of 0.74 sd and 0.97 sd when number of books in the home is the SES proxy.

It is also important to note that gaps by mother’s educational attainment (Figure C; Table 7) and income (Figure D; Table 8)—two of the five components of the SES construct—are very close to the ones obtained by our SES composite measure (as shown in Figure A). All in all, results seem internally consistent as well as generally consistent with prior results on this topic (Reardon and Portilla 2016).

In terms of changes in the performance gaps over time (unadjusted), the findings vary depending on which indicators of social class are used, with mother’s education and household income being the indicators associated with the largest changes in the gaps. Changes in the performance gaps in cognitive skills between 1998 and 2010 by our composite SES measure and books are similar: an increase in the reading gap between children in the top and bottom quintiles of about a tenth of a standard deviation (0.10 sd with the composite SES measure [Figure A] and 0.08 sd if SES is proxied with books), and no significant change in mathematics (there are some differences in the noncognitive outcomes).

However, by mother’s educational attainment, there are no changes in relative reading and approaches to learning gaps reported by parents over time, and a significant reduction in the gaps in the remaining outcomes. Meanwhile, income-based gaps for the two cognitive skills—reading and math—decreased by -0.13 and -0.23 sd respectively, and for approaches to learning as reported by teachers by -0.13 sd. No significant changes occurred for the remaining noncognitive skills.

In sum, this sensitivity analysis demonstrates that all of the indicators are reliable proxies of SES for the estimation of early achievement gaps, though absolute gaps may vary slightly depending on the indicator used. However, the proxies are not equally reliable when we assess trends in the gaps by SES or their drivers. As such, aside from differences in the definitions and procedures used to construct each SES proxy, the proxies should not be treated as fully equivalent. The decomposition conducted here helps clarify the different weights that various components of SES may have in driving changes in gaps by social class. For example, variation in income across groups over time is associated with decreased performance gaps in the cognitive skills between 1998 and 2010, and variation in educational attainment quintiles or categories over time is associated with decreased performance gaps across cohorts in most noncognitive skills. But variation in books in the home over time and among groups is associated with increased gaps in reading and in parents’ assessed approaches to learning. Such findings also point to very different policy solutions: if mothers’ education is the main driver, enhancing that will improve children’s prospects. On the other hand, findings that indicate that income inequality is the larger culprit would point to the need for policies that reduce such inequalities. Future research should consider and look more closely into these questions.

What can we learn from these analyses?

The multiple factors and relationships examined in this section can now be examined from a policy perspective. If the aim is to increase equity, to improve children’s development across the board, and to improve our understanding of children’s development, there are two major policy recommendations:

- Directly support less-resourced families so that they have greater access to educational and economic resources (for the latter, see García and Weiss 2017). All the early educational and play activities measured, which include center-based pre-K care and literacy/reading and other activities, as well as the number of books a child has, are positively associated with children’s readiness, and in part account for social-class gaps, but are much less accessible to children of lower socioeconomic status. Virtually all of the associations between these factors and outcomes were strong and positive (with a handful of exceptions), and some even grew over time. A related research recommendation of particular interest would be to examine whether the intensity of these activities or practices has any threshold level of effectiveness (after which point they no longer affect children’s development). 23 Also, it would be helpful to understand why parents’ expectations of their children’s educational attainment increased so much and how this has affected children’s development. For example, do parents have a better understanding of the relationship between educational attainment and prospects for success in life and the workforce? Are children performing better because their parents expect more, or because parents who expect more are also delivering more in the form of enriching activities?

- Design and implement strategies that compensate at the community level for children’s lack of access to key foundational resources (economic and educational). These strategies can be considered indirect supports for less-resourced families that reduce inequities and complement the direct supports described above. Examples of communities that have enacted such comprehensive support initiatives provide a good starting point to explore how and why they emerge; the types of supports they provide (from preschool programs and home visits with parents to enriching summer programs, school-based health clinics, and more); the challenges of scaling them up and sustaining them; the benefits they deliver for students, and particularly for disadvantaged students; and their implications for policy at the local, state, and even federal levels. The next section of this report thus presents an analysis based on qualitative data from promising initiatives in a dozen school districts across the country (Weiss 2016a–h).

What are pioneering school districts doing to combat these inequities and resulting gaps?

This section of the report draws on a set of case studies published by the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education (BBA), a national campaign that advances evidence-based strategies to mitigate the impacts of poverty-related disadvantages on teaching and learning. 24 The case studies feature school districts that have employed comprehensive educational strategies to ensure that more children, especially low-income children, have strong early academic and life foundations, and that resulting early gains are sustained and built on through children’s K–12 years. (These strategies are often referred to as “whole-child” approaches to education, in reflection of their holistic nature.) We explore the premise that school districts that take a whole-child approach to education and a whole-community approach to delivering it are likely to enjoy larger gains in academic achievement and to narrow their race- and income-based achievement gaps. In doing so, we are building on evidence suggesting that consistent, strong supports for children and their families—both in and out of school—can avoid the “fade-out” seen among graduates of many pre-K programs and even enhance those programs’ early benefits.

This section is thus divided into four parts: (1) an introduction to the case study districts, followed by discussions of (2) how these districts invest in early childhood care and education, (3) how the districts’ investments in K–12 strategies sustain and boost the early childhood investments, and (4) how academic gains and narrowing achievement gaps indicate that the investments are paying off. Table 10 provides basic information on the 12 school districts/communities studied; Appendix E at the end of this report provides more information on key characteristics of these districts. 25

Introduction to the case studies: Why these districts enacted whole-child strategies