An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

[A cyberbullying study: Analysis of cyberbullying, comorbidities and coping mechanisms]

Affiliations.

- 1 EA Clipsy 44 30, laboratoire Evaclipsy, université Paris Ouest, Nanterre-La-Défense, 92, 200, avenue de la République, 92001 Nanterre, France. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 CeRSM (EA 2931 CERSM), centre de recherche sur le sport et le mouvement, université Paris Ouest, Nanterre-La-Défense, 92, 200, avenue de la République, 92001 Nanterre, France.

- 3 EA Clipsy 44 30, laboratoire Evaclipsy, université Paris Ouest, Nanterre-La-Défense, 92, 200, avenue de la République, 92001 Nanterre, France.

- PMID: 25240939

- DOI: 10.1016/j.encep.2014.08.003

Introduction: Cyberbullying is a relatively new form of bullying. This bullying is committed by means of an electronic act, the transmission of a communication by message, text, sound, or image by means of an electronic device, including but limited to, a computer phone, wireless telephone, or other wireless communication device, computer, games console or pager. Cyberbullying is characterized by deliberately threatening, harassing, intimidating, or ridiculing an individual or group of individuals; placing an individual in reasonable fear of harm; posting sensitive, private information about another person without his/her permission; breaking into another person's account and/or assuming another individual's identity in order to damage that person's reputation or friendships.

Literature finding: A review of the literature shows that between 6 and 40% of all youths have experienced cyberbullying at least once in their lives. Several cyberbullying definitions have been offered in the literature, many of which are derived from definitions of traditional bullying. In our study we asked clear definition of cyberbullying. Few studies explicate the psychosocial determinants of cyberbullying, and coping mechanisms. The authors of the literature recommend developing resiliency, but without analyzing the resilience factor.

Objectives: The first aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of adolescents and adults engaged in cyberbullying. The second aim was to examine the coping mechanisms and comorbidity factors associated with the cyberbullied people.

Methodology: The sample was composed of 272 adolescents (from a high school) and adults (mean age=16.44 ± 1). The Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire was used to identify profiles of cyberbullying. Coping mechanisms were investigated using the Hurt Disposition Scale (HDS) and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). Comorbidities were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD), Liebowitz's Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), and the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire (BVAQ).

Results: Almost one student in three was involved in cyberbullying (34.9% as cyber-victim, 16.9 as cyberbully); 4.8% of our sample was concerned by bullying as a victim. The victims of bullying were also victims of cyberbullying. The mean age of victims of cyberbullying was 17.84 ± 5.9 years, and the mean age of victims of bullying was 16.3 ± 4.5 years. Correlation coefficient was significant for HAD, LSAS, BVAQ scales with CQ. The retaliatory variable of HDS scale was not significant. Finally, the coping strategies of students who reported victimization were explored. These strategies include coping, telling someone, figuring out the situation, and avoidant coping. The results showed for the victims of cyberbullying, that they take longer to recover from a stressful event, compared to victims of bullying.

Conclusion: Results have indicated the importance of further study of cyberbullying because its association with comorbidities was distinct from traditional forms of bullying. The biggest risk factor for the adolescents is the severity of the consequences. These are: the adoption of the avoidance coping strategy, the occurrence of offline bullying during the situation, the adoption of the self-control coping strategy, the variety of cyberbullying acts, the victim's level of self-blame, the victim's perception of the duration of the situation, and the frequency of cyberbullying victimization.

Keywords: Adolescents; Anxiety; Cyberbullying; Depression; Harcèlement; Internet; Mécanismes d’adaptations; Resilience; Youth.

Copyright © 2014 L’Encéphale, Paris. Published by Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Bullying through the Internet - Cyberbullying. Krešić Ćorić M, Kaštelan A. Krešić Ćorić M, et al. Psychiatr Danub. 2020 Sep;32(Suppl 2):269-272. Psychiatr Danub. 2020. PMID: 32970646 Review.

- The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP. Waasdorp TE, et al. J Adolesc Health. 2015 May;56(5):483-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002. Epub 2015 Jan 24. J Adolesc Health. 2015. PMID: 25631040

- Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. Chang FC, Lee CM, Chiu CH, Hsi WY, Huang TF, Pan YC. Chang FC, et al. J Sch Health. 2013 Jun;83(6):454-62. doi: 10.1111/josh.12050. J Sch Health. 2013. PMID: 23586891

- [Cyber-bullying in adolescents: associated psychosocial problems and comparison with school bullying]. Kubiszewski V, Fontaine R, Huré K, Rusch E. Kubiszewski V, et al. Encephale. 2013 Apr;39(2):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2012.01.008. Epub 2012 May 28. Encephale. 2013. PMID: 23095590 French.

- Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health. Suzuki K, Asaga R, Sourander A, Hoven CW, Mandell D. Suzuki K, et al. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2012;24(1):27-35. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2012.005. Epub 2011 Nov 29. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2012. PMID: 22909909 Review.

- Fight or Flight? Curvilinear Relations between Previous Cyberbullying Victimization Experiences and Continuous Use of Social Media: Social Media Rumination and Distress as Chain Mediators. Gu C, Liu S, Chen S. Gu C, et al. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022 Oct 30;12(11):421. doi: 10.3390/bs12110421. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022. PMID: 36354398 Free PMC article.

- A Cyberbullying Media-Based Prevention Intervention for Adolescents on Instagram: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Kutok ER, Dunsiger S, Patena JV, Nugent NR, Riese A, Rosen RK, Ranney ML. Kutok ER, et al. JMIR Ment Health. 2021 Sep 15;8(9):e26029. doi: 10.2196/26029. JMIR Ment Health. 2021. PMID: 34524103 Free PMC article.

- Psychological Well-Being in a Connected World: The Impact of Cybervictimization in Children's and Young People's Life in France. Audrin C, Blaya C. Audrin C, et al. Front Psychol. 2020 Jul 17;11:1427. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01427. eCollection 2020. Front Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32765342 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Masson (France)

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Last updated 20/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > BJPsych Bulletin

- > The Psychiatrist

- > Volume 37 Issue 5

- > Cyberbullying and its impact on young people's emotional...

Article contents

The nature of cyberbullying, the impact of cyberbullying on emotional health and well-being, technological solutions, asking adults for help, cyberbullying and its impact on young people's emotional health and well-being.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 January 2018

The upsurge of cyberbullying is a frequent cause of emotional disturbance in children and young people. The situation is complicated by the fact that these interpersonal safety issues are actually generated by the peer group and in contexts that are difficult for adults to control. This article examines the effectiveness of common responses to cyberbullying.

Whatever the value of technological tools for tackling cyberbullying, we cannot avoid the fact that this is an interpersonal problem grounded in a social context.

Practitioners should build on existing knowledge about preventing and reducing face-to-face bullying while taking account of the distinctive nature of cyberbullying. Furthermore, it is essential to take account of the values that young people are learning in society and at school.

Traditional face-to-face bullying has long been identified as a risk factor for the social and emotional adjustment of perpetrators, targets and bully victims during childhood and adolescence; Reference Almeida, Caurcel and Machado 1 - Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 bystanders are also known to be negatively affected. Reference Ahmed, Österman and Björkqvist 7 - Reference Salmivalli 9 The emergence of cyberbullying indicates that perpetrators have turned their attention to technology (including mobile telephones and the internet) as a powerful means of exerting their power and control over others. Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett 10 Cyberbullies have the power to reach their targets at any time of the day or night.

Cyberbullying takes a number of forms, to include:

• flaming: electronic transmission of angry or rude messages;

• harassment: repeatedly sending insulting or threatening messages;

• cyberstalking: threats of harm or intimidation;

• denigration: put-downs, spreading cruel rumours;

• masquerading: pretending to be someone else and sharing information to damage a person’s reputation;

• outing: revealing personal information about a person which was shared in confidence;

• exclusion: maliciously leaving a person out of a group online, such as a chat line or a game, ganging up on one individual. Reference Schenk and Fremouw 11

Cyberbullying often occurs in the context of relationship difficulties, such as the break-up of a friendship or romance, envy of a peer’s success, or in the context of prejudiced intolerance of particular groups on the grounds of gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation or disability. Reference Hoff and Mitchell 12

A survey of 23 420 children and young people across Europe found that, although the vast majority were never cyberbullied, 5% were being cyberbullied more than once a week, 4% once or twice a month and 10% less often. Reference Livingstone, Haddon, Anke Görzig and Ólafsson 13 Many studies indicate a significant overlap between traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Reference Perren, Dooley, Shaw and Cross 5 , Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 , Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 , Reference Ybarra and Mitchell 15 However, a note of caution is needed when interpreting the frequency and prevalence of cyberbullying. As yet, there is no uniform agreement on its definition and researchers differ in the ways they gather their data, with some, for example, asking participants whether they have ‘ever’ been cyberbullied and others being more specific, for example, ‘in the past 30 days’.

Research consistently identifies the consequences of bullying for the emotional health of children and young people. Victims experience lack of acceptance in their peer groups, which results in loneliness and social isolation. The young person’s consequent social withdrawal is likely to lead to low self-esteem and depression. Bullies too are at risk. They are more likely than non-bullies to engage in a range of maladaptive and antisocial behaviours, and they are at risk of alcohol and drugs dependency; like victims, they have an increased risk of depression and suicidal ideation. Studies among children Reference Escobar, Fernandez-Baen, Miranda, Trianes and Cowie 2 - Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpalä, Rantanen and Rimpalä 4 , Reference Kumpulainen, Rasanen and Henttonen 16 and adolescents Reference Salmivalli, Lappalainen and Lagerspetz 17 , Reference Sourander, Helstela, Helenius and Piha 18 indicate moderate to strong relationships between being nominated by peers as a bully or a victim at different time points, suggesting a process of continuity. The effects of being bullied at school can persist into young adulthood. Reference Isaacs, Hodges and Salmivalli 19 , Reference Lappalainen, Meriläinen, Puhakka and Sinkkonen 20

Studies demonstrate that most young people who are cyberbullied are already being bullied by traditional, face-to-face methods. Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 , Reference Dooley, Pyzalski and Cross 21 - Reference Riebel, Jaeger and Fischer 23 Cyberbullying can extend into the target’s life at all times of the day and night and there is evidence for additional risks to the targets of cyberbullying, including damage to self-esteem, academic achievement and emotional well-being. For example, Schenk & Fremouw Reference Schenk and Fremouw 11 found that college student victims of cyberbullying scored higher than matched controls on measures of depression, anxiety, phobic anxiety and paranoia. Studies of school-age cyber victims indicate heightened risk of depression, Reference Perren, Dooley, Shaw and Cross 5 , Reference Gradinger, Strohmeier and Spiel 22 , Reference Juvonen and Gross 24 of psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches, abdominal pain and sleeplessness Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 and of behavioural difficulties including alcohol consumption. Reference Mitchell, Ybarra and Finkelhor 25 As found in studies of face-to-face bullying, cyber victims report feeling unsafe and isolated, both at school and at home. Similarly, cyberbullies report a range of social and emotional difficulties, including feeling unsafe at school, perceptions of being unsupported by school staff and a high incidence of headaches. Like traditional bullies, they too are engaged in a range of other antisocial behaviours, conduct disorders, and alcohol and drug misuse. Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 , Reference Hinduja and Patchin 26

The most fundamental way of dealing with cyberbullying is to attempt to prevent it in the first place, through whole-school e-safety policies Reference Campbell 27 - Reference Stacey 29 and through exposure to the wide range of informative websites that abound (e.g. UK Council for Child Internet Safety (UKCCIS; www.education.gov.uk/ukccis ), ChildLine ( www.childline.org.uk )). Many schools now train pupils in e-safety and ‘netiquette’ to equip them with the critical tools that they will need to understand the complexity of the digital world and become aware of its risks as well as its benefits. Techniques include blocking bullying behaviour online or creating panic buttons for cyber victims to use when under threat. Price & Dalgleish Reference Price and Dalgleish 30 found that blocking was considered as a most helpful online action by cyber victims and a number of other studies have additionally found that deleting nasty messages and stopping use of the internet were effective strategies. Reference Livingstone, Haddon, Anke Görzig and Ólafsson 13 , Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 , Reference Juvonen and Gross 24 However, recent research by Kumazaki et al Reference Kumazaki, Kanae, Katsura, Akira and Megumi 31 found that training young people in netiquette did not significantly reduce or prevent cyberbullying. Clearly there is a need for further research to evaluate the effectiveness of different types of technological intervention.

Parents play an important role in prevention by banning websites and setting age-appropriate limits of using the computer and internet. Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 Poor parental monitoring is consistently associated with a higher risk for young people to be involved in both traditional and cyberbullying, whether as perpetrator or target. Reference Ybarra and Mitchell 15 However, adults may be less effective in dealing with cyberbullying once it has occurred. Most studies confirm that it is essential to tell someone about the cyberbullying rather than suffer in silence and many students report that they would ask their parents for help in dealing with a cyberbullying incident. Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett 10 , Reference Stacey 29 , Reference Aricak, Siyahhan, Uzunhasanoglu, Saribeyoglu, Ciplak and Yilmaz 32 On the other hand, some adolescents recommend not consulting adults because they fear loss of privileges (e.g. having and using mobile telephones and their own internet access), and because they fear that their parents would simply advise them to ignore the situation or that they would not be able to help them as they are not accustomed to cyberspace. Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett 10 , Reference Hoff and Mitchell 12 , Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 , Reference Stacey 29 In a web-based survey of 12- to 17-year-olds, of whom most had experienced at least one cyberbullying incident in the past year, Juvonen & Gross Reference Juvonen and Gross 24 found that 90% of the victims did not tell their parents about their experiences and 50% of them justified it with ‘I need to learn to deal with it myself’.

Students also have a rather negative and critical attitude to teachers’ support and a large percentage consider telling a teacher or the school principal as rather ineffective. Reference Aricak, Siyahhan, Uzunhasanoglu, Saribeyoglu, Ciplak and Yilmaz 32 , Reference DiBasilio 33 Although 17% of students reported to a teacher after a cyberbullying incident, in 70% of the cases the school did not react to it. Reference Hoff and Mitchell 12

Involving peers

Young people are more likely to find it helpful to confide in peers. Reference Livingstone, Haddon, Anke Görzig and Ólafsson 13 , Reference Price and Dalgleish 30 , Reference DiBasilio 33 Additionally, it is essential to take account of the bystanders who usually play a critical role as audience to the cyberbullying in a range of participant roles, and who have the potential to be mobilised to take action against cyberbullying. Reference Salmivalli 9 , Reference Cowie 34 For example, a system of young cyber mentors, trained to monitor websites and offer emotional support to cyber victims, was positively evaluated by adolescents. Reference Banerjee, Robinson and Smalley 35 Similarly, DiBasilio Reference DiBasilio 33 showed that peer leaders in school played a part in prevention of cyberbullying by creating bullying awareness in the school, developing leadership skills among students, establishing bullying intervention practices and team-building initiatives in the student community, and encouraging students to behave proactively as bystanders. This intervention successfully led to a decline in cyberbullying, in that the number of students who participated in electronic bullying decreased, while students’ understanding of bullying widened.

Although recommended strategies for coping with cyberbullying abound, there remains a lack of evidence about what works best and in what circumstances in counteracting its negative effects. However, it would appear that if we are to solve the problem of cyberbullying, we must also understand the networks and social groups where this type of abuse occurs, including the importance that digital worlds play in the emotional lives of young people today, and the disturbing fact that cyber victims can be targeted at any time and wherever they are, so increasing their vulnerability.

There are some implications for professionals working with children and young people. Punitive methods tend on the whole not to be effective in reducing cyberbullying. In fact, as Shariff & Strong-Wilson Reference Shariff, Strong-Wilson and Kincheloe 36 found, zero-tolerance approaches are more likely to criminalise young people and add a burden to the criminal justice system. Interventions that work with peer-group relationships and with young people’s value systems have a greater likelihood of success. Professionals also need to focus on the values that are held within their organisations, in particular with regard to tolerance, acceptance and compassion for those in distress. The ethos of the schools where children and young people spend so much of their time is critical. Engagement with school is strongly linked to the development of positive relationships with adults and peers in an environment where care, respect and support are valued and where there is an emphasis on community. As Batson et al Reference Batson, Ahmad, Lishner, Tsang, Snyder and Lopez 37 argue, empathy-based socialisation practices encourage perspective-taking and enhance prosocial behaviour, leading to more satisfying relationships and greater tolerance of stigmatised outsider groups. This is particularly relevant to the discussion since researchers have consistently found that high-quality friendship is a protective factor against mental health difficulties among bullied children. Reference Skrzypiec, Slee, Askell-Williams and Lawson 38

Finally, research indicates the importance of tackling bullying early before it escalates into something much more serious. This affirms the need for schools to establish a whole-school approach with a range of systems and interventions in place for dealing with all forms of bullying and social exclusion. External controls have their place, but we also need to remember the interpersonal nature of cyberbullying. This suggests that action against cyberbullying should be part of a much wider concern within schools about the creation of an environment where relationships are valued and where conflicts are seen to be resolved in the spirit of justice and fairness.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to the COST ACTION IS0801 for its support in preparing this article ( https://sites.google.com/site/costis0801 ).

Declaration of interest

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 37, Issue 5

- Helen Cowie (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.112.040840

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Cyberbullying and mental health: past, present and future.

- 1 University School of Management and Entrepreneurship (USME), Delhi Technological University, New Delhi, India

- 2 Department of Operational Research, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India

- 3 Faculty of Management Sciences, Department of Business Management, Central University of Technology, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Purpose: Cyberbullying has attracted the world's attention, and therefore researchers across the world have contributed to the literature on cyberbullying and mental health. Amongst others, they have conducted bibliometric analyses and associated cyberbullying with various factors but have not determined the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health. Hence, the aim of this study was to conduct bibliometric analyses of cyberbullying and mental health to analyze the academic performance of the literature on impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health; and to propose future research avenues to make further contributions to this field of study.

Methodology: Spreadsheets and VOSviewer were used to conduct the bibliometric analysis. The data were extracted from the SCOPUS database which provided an extensive collection of data and journals.

Findings: Having explored the top active countries publishing on the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health and the academic performance of such research articles by means of a qualitative bibliometric analysis, the results revealed that this research topic is still to be researched extensively. The study also suggests countries/regions where this research topic can be explored further, as well as possible journals for publication of research results, and further studies to be conducted.

Discussion: The literature presents a fragmented view on the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health. Studies on cyberbullying are limited for the reasons as discussed in this article. Hence, bibliometric analysis was conducted to analyze the performance of academic literature on the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health; the academic performance of research articles on cyberbullying and mental health; and to make proposals toward a future research agenda.

Introduction

Mental health has garnered significant attention from the research community, academics, and policymakers across the globe ( Somé et al., 2022 ), and has emerged as a major contributor to the global health crisis ( Wang et al., 2021 ). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as “a state of wellbeing in which the individual realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” ( World Health Organization, 2004 ). According to the definition, a mentally healthy person effectively manages stress, work to his/her optimal output levels, and positively contribute to his/her community. The definition also suggests that the absence of, or an impaired state of mental wellbeing may hinder individuals from realizing their full potential, hamper their productivity, and diminish their ability to contribute positively to their communities ( Somé et al., 2022 ). The WHO report on mental health reveals that nearly one in every eight individuals globally experience mental health issues ( World Health Organization, 2019 ). The report further indicates that depression is one of the major factors contributing to impaired mental health, affecting almost 3.8% of the world's population ( World Health Organization, 2022 ), including 5% of adults, with the rest being children and adolescents ( World Health Organization, 2022 ). Several factors such as genetics ( Shabani et al., 2019 ), environment ( Usher et al., 2019 ), unhealthy lifestyle choices ( Lim et al., 2016 ), extreme conditions such as COVID-19 ( Greenberg, 2020 ; Moreno et al., 2020 ), broken relationships and lack of social support ( Mehtaa et al., 2023 ), excessive usage of social media ( Karim et al., 2020 ), and bullying experiences ( Giumetti and Kowalski, 2022 ) contribute to the rising mental health issues across the globe. People of all ages, professions, genders, geographic regions, colors, castes, and creeds suffer from mental health issues ( Oksanen et al., 2020 ; Achuthan et al., 2023 ; Bansal et al., 2023a , b ). Furthermore, there has been a significant rise in mental health issues since late 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant exponential increase in internet usage. Although COVID-19 is on the decline, the negative repercussions of high internet use are still visible. One of its most annoying and unfortunate consequences is cyberbullying ( Xie et al., 2020 ).

Cyberbullying is defined “as an aggressive, intentional act carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself” ( Smith et al., 2008 , p. 376). In other words, cyberbullying refers to an intentional and repetitive act carried out using electronic media or information communication technology (ICT) to bully an individual or group who is defenseless against these attacks. This type of bullying differs from traditional bullying in various ways. ICT allows bullies to hide their identities and bully others as often as they want to ( Bashir Shaikh et al., 2020 ). Hashemi (2021) also differentiate cyberbullying from traditional bullying, suggesting that cyberbullies can bully a large number of victims at any given point in time. They further suggest that cyberbullying may leave long-lasting memories in its victims' minds, also known as a digital footprint ( Hashemi, 2021 ). It takes diverse forms in different situations. For instance, flaming occurs when a perpetrator uses foul and violent language during online communication ( Maichum et al., 2016 ), and trolling involves taunting a person or a group in a humorous but undignified manner ( Zsa Tajol Asanan, 2017 ). Denigration involves spreading malicious information to damage a victim's reputation ( Zainudin et al., 2016 ). Masquerading is pretending to be someone else, usually the victim ( Peled, 2019 ). Some other modern forms of cyberbullying include outing and cyberstalking ( Wright, 2018 ; Peled, 2019 ).

Although cyberbullying is a dreadful act, its adverse impact on an individual's physical and mental health necessitates an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon. Rao and Rao (2021) are of the view that cyberbullying may result in the development of mental health issues, depression ( Englander, 2021 ), anxiety, psychological distress, and post-traumatic stress symptoms ( Nochaiwong et al., 2021 ). The events of cyberbullying are traumatizing and psychologically wounding ( Paat and Markham, 2020 ). Victims of cyberbullying may develop depressive symptoms and insomnia ( Kim et al., 2020 ), and counterproductive work behavior, along with experiencing lower job satisfaction levels ( Kowalski et al., 2017 ). Victims may also show lower engagement ( Muhonen et al., 2017 ) and higher attrition intentions ( Li et al., 2018 ). Students are among the worst affected victims ( Kowalski and Limber, 2013 ). They suffer from negative consequences such as higher absenteeism, lack of concentration ( Kowalski et al., 2018 ), feelings of shame and guilt ( Ciucci and Baroncelli, 2014 ), and engaging in anti-social behavior ( Cavalcanti et al., 2019 ). Maurya et al.'s (2022) 3 year longitudinal study reported that the rates of cyberbullying had increased from 3.8% to 6.4% in female and from 1.9% to 5.6% in male respondents over study's period. Also, their study suggested that female respondents have developed a high rate of suicidal ideation compared to male participants due to experiencing cyberbullying. Furthermore, Xia et al. (2023) report that cyberbullying was one of the major reasons for the development of appearance anxiety in the college students, which has further exaggerated the social anxiety in them. The authors further reported that the combined effect of cyberbullying and appearance anxiety has caused higher social anxiety levels in the college students. Additionally, a study from Bangladesh revealed that university students who experienced cyberbullying during their tenure at the university had developed anger issues, self-guilt, and fear of attending college ( Sheikh et al., 2023 ). Likewise, a study on Malaysian youth revealed that victims of cyberbullying had developed anxiety, stress, and exhaustion, which have resulted in an increase in suicidal ideations among them. Therefore, the rising literature on cyberbullying and mental health has necessitated to analyze its academic performance. Also, acknowledging the importance of review and bibliometric studies, several contemporary researchers have suggested that bibliometric studies on cyberbullying and mental health issues should be conducted.

A bibliometric analysis is a research method involving the analysis of published literature to identify patterns and trends in a particular field ( Donthu et al., 2021 ). Its applicability is multidisciplinary ( Andersen, 2019 ), with various researchers having conducted bibliometric analyses in fields such as human resources ( Andersen, 2019 ), journalism ( Bansal et al., 2023a ), corporate governance ( Singhania et al., 2022a , b ) and ecopreneurship ( Guleria and Kaur, 2021 ). This study used bibliometric analysis to analyze the research documents on cyberbullying and mental health. Further, Donthu et al. (2021) have suggested using bibliometric analysis over meta-analysis and structured literature review based on the following differences. Firstly, the scope of the study is broader, and the goal is to summarize vast amounts of bibliometric data for presenting the performance and state of the academic intellect. Secondly, the aim is to analyze the emerging trends of the field. Thirdly, the amount of literature is too large for manual reviewing and the analysis requires a mix of qualitative and quantitative analyses [for detailed comparison, please refer to the Table 1 of Donthu et al. (2021) ]. Therefore, bibliometric analysis could provide insight into the extent and scope of research on cyberbullying and its impact on mental health by identifying top influential articles, journals, and authors, as well as identifying gaps in the literature and potential areas for future research through topical analysis and analyzing new emerging keywords and topics. Consequently, bibliometric analysis was considered the best choice for analyzing the past, present and future of cyberbullying and its impact on the mental health.

Moreover, bibliometric analysis on cyberbullying and mental health have not been conducted extensively. Saif and Purbasha (2023) performed a qualitative systematic literature review on young females in developing countries who have experienced cyberbullying. They differentiated and categorized the instances of cyberbullying those young females faced. Additionally, the bibliometric analysis of Achuthan et al. (2023) focused on studies on cyberbullying and sustainable development and the impact of COVID-19 on this relationship. Shao and Cao (2021) analyzed the existing literature on adolescent cyberbullying retrieved from the Web of Science. Furthermore, Barragán Martín et al. (2021) focused on analyzing literature on cyberbullying from adolescents' perspective published in the Web of Science database, without specifically focusing on mental health. Moreover, the bibliometric analysis conducted by Cretu and Morandau (2022) focused on education setups and cyberbullying in relation to adolescents. Peker and Yalcin (2022) focused on studying cyberbullying literature published in the Web of Science database only. However, their study is limited to studies published up until 24 July 2021, and only addresses topics such as cooperation between countries, institutions, and authors. They did not analyze keywords or identify emerging trends in cyberbullying literature. Their study also did not study the relation between cyberbullying and mental health. Other studies have focused on victims of cyberbullying (e.g., Mäntylä et al., 2018 ; López-Meneses et al., 2020 ; Gómez Tabares and Correa Duque, 2022 ), educational setting ( Moreno and Piqueras, 2020 ), or have been location-specific, such as those conducted in Turkey ( Manap, 2022 ), Spain ( Andrés et al., 2016 ) and Latin America ( Herrera-López et al., 2018 ; Villanueva et al., 2020 ). Finally, Kim et al. (2021) studied literature focusing on workplace cyberbullying in medical and hospital setups. Therefore, our study will cover the highlighted gap and present a fresh perspective on the impact of cyberbullying on the mental health.

Motivation of the present study

This study differs from previous studies on two broad bases. Firstly, the preceding section presented fragmented studies found in the literature. Although previous studies have explored various aspects of cyberbullying, they have their own limitations, such as being limited to location, age group, or even sustainable development topics. Some studies fail to address the relationship between cyberbullying and mental health, or only focus on a particular age or a specific group involved in cyberbullying. Secondly, previous studies have primarily utilized systematic literature reviews to explore the nexus of cyberbullying and mental health. This study aims to address these limitations by conducting a comprehensive analysis of the global literature on cyberbullying and mental health. The study was not confined to a specific geographic location, age group, or work setting. Instead, the aim was to explore the past, present, and future of the knowledge that pertains to the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health. Thirdly, mental health is a serious concern which has attracted global attention. According to various researchers many factors can be associated with degradation of mental health, including cyberbullying ( Schodt et al., 2021 ). Also, as discussed in the preceding section, cyberbullying can negatively affect mental health like developing depressive symptoms in the victims ( Kowalski et al., 2022 ), suicidal ideation ( Kowalski and Limber, 2013 ), stress and anxiety ( Nochaiwong et al., 2021 ; Rao and Rao, 2021 ). Hence, it has become imperative to study effects on cyberbullying on the mental health. Also, with the help of present study we can analyze the academic performance of the literature on the topic under consideration and discuss certain future trends. Additionally, the SCOPUS database was utilized, which has not been extensively used in previous bibliometric studies on this topic. This database was chosen due to its various merits, as will be discussed in the forthcoming sections. Furthermore, a bibliometric approach was adopted, which helps mitigate the risk of bias that can be generated during a systematic literature review. Unlike a systematic literature review, a bibliometric analysis includes all the identified studies on the topic that fall within its scope. Lastly, the current study seeks to address the following:

(a) What are present trends in research publications, citations, and research areas?

(b) What is countries' performance and authors' performance on the topic?

(c) How are the journals performing on the said topic?

(d) How are articles performing? and

(e) What are widely used keywords and emerging topics?

Apart from a general study of these topics, this study explored (a) emerging countries and countries where research on the topic has not been done yet, (b) emerging journals, and (c) top publications on the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health published during the past 5 years. Consequently, the authors systematically extracted and explored literary data (research publications) from the SCOPUS database. This study finds its design on the basis of suggestions and guidelines provided by Donthu et al. (2021) . Lastly, software such as spreadsheets and VOSviewer were used to analyze the final dataset.

Methodology

Database selection.

The SCOPUS database was used to extract data for bibliometric analysis. SCOPUS is the largest database of peer-reviewed scientific literature including journals, books, and conference proceedings. Other databases such as Google Scholar, Pubmed, PsycInfo, and Web of Science (WoS) are also available, but the SCOPUS database was used as it rendered results more relevant to the context of this study. Google Scholar does not provide a dataset in a format suitable for bibliometric analysis. The PubMed dataset predominantly comprises research in life sciences and biomedical topics, whilst the PsycInfo database consists of works in the field of psychology. However, cyberbullying studies are covered under several themes such as psychology, human resources, economics, medical, education, sociology, etc. Also, SCOPUS is the largest database and it provides information regarding the most prominent authors, countries, affiliations, journals, and publication years both in tabular and graphic form. Therefore, the SCOPUS database is preferred over all other available databases.

Data extraction

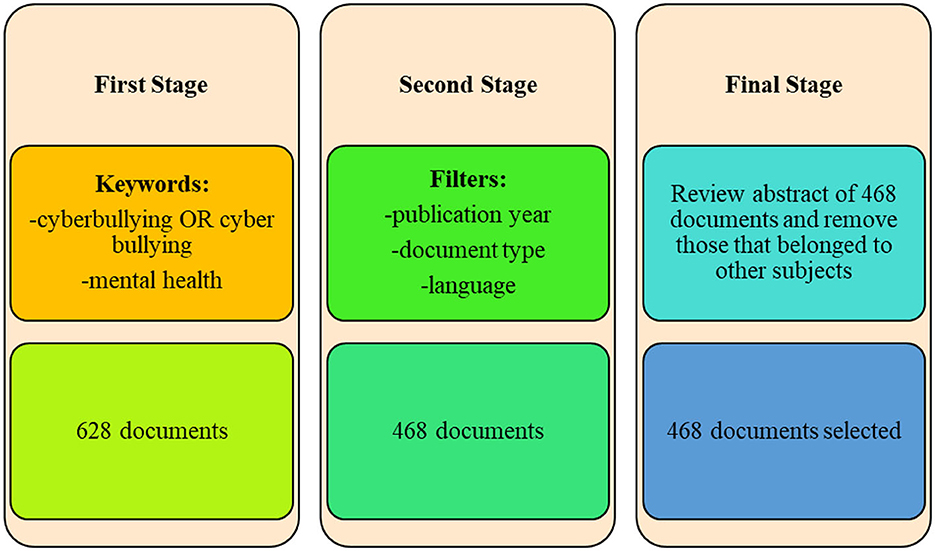

Previous researchers used terms such a “cyberbullying,” “cyber bullying,” “mental health,” “bully,” “victimization,” “perpetration,” and “bystander” in their studies. In the present study, terminology such as perpetrators or victims were not used, as it would have restricted the study to exploring mental health issues experienced either by victims or perpetrators, only. Moreover, based on our previous bibliometric study on cyberbullying, it was found that (a) no bibliometric study had analyzed the literature on the nexus of cyberbullying and mental health and (b) mental health is one of the major fields of study in collaboration with cyberbullying ( Bansal et al., 2023a ). Although various authors have used a vast list of keywords while retrieving a dataset on mental health ( Guo et al., 2023 ), they have skipped many terms; for instance, “suicidal,” “suicidal tendency,” “suicide,” “suicidal ideation,” and “deviant behavior.” Also, it was observed during our extensive literature review, apart from specifying mental disorder, the term “mental health” was also used as one of the keywords or extended keywords. Therefore, we have used “mental health” as an umbrella term to not to skip any study that might have explored any one mental health problem arising out of cyberbullying. Since the objective of the study was to analyze academic knowledge on cyberbullying and mental health from both the victims' and perpetrators' perspectives, “cyberbullying” OR “cyber bullying” AND “mental health” were used in the search string. Consequently, 628 documents were retrieved.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Results that contained 'cyberbullying,' 'cyber bullying' and 'mental health' in the title, abstract and keywords were deemed fit for the study. Documents published only in English until 31 December 2022 were considered as publications for year 2023 were over during the data exploration time frame and time frame limiting is based on the recommendations of various researchers including Singh et al. (2021) and Donthu et al. (2021) . Boolean 'OR' was used to maximize the results, whereas 'AND' was used to limit the research results to mental health issues. Based on this inclusion and exclusion criteria, 576 articles met the requirements. Documents such as book titles and conference papers were excluded, as they are not always subjected to a rigorous peer-review process ( Singh et al., 2021 ). This resulted in the exclusion of 108 documents. Finally, 468 documents were considered for the data screening process.

Data screening

The authors studied the abstracts of 468 documents and found that they all met the criteria. Figure 1 presents the search model.

Figure 1 . Search model. Source: SCOPUS, Authors' creation.

Data analysis

Spreadsheets and VOSviewer were used to analyze the data obtained from the SCOPUS database. Specifically, descriptive statistics were applied to generate various tables and charts to explore patterns in the data. These charts and tables aided in the analysis of publications and citation trends. VOSviewer was employed to analyze the most influential articles, journals, and authors, rank nations based on their publications and citation activity, and to perform keyword analysis and evolution. The study also examined the evolution of academic knowledge on the subject across different countries, authors, and journals. Citation and co-citation analyses in VOSviewer were utilized to conduct the aforementioned analyses, as suggested by previous researchers such as Singh et al. (2021) and Donthu et al. (2021) .

Results and discussion

Publication and citation trends.

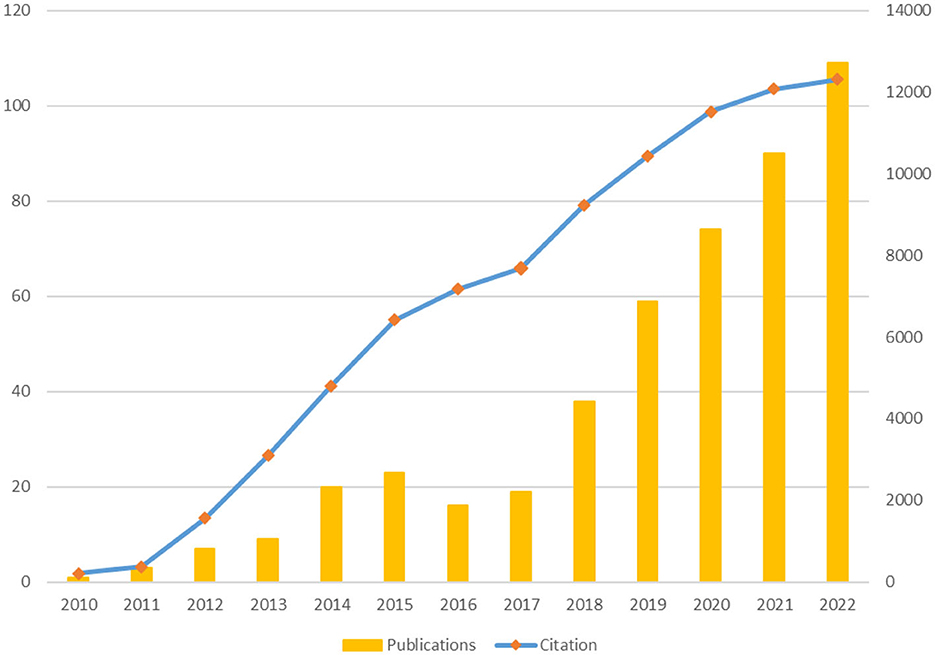

For purposes of this study, 406 articles and 62 reviewed articles were studied. Annual publications on the impact of cyberbullying on people's mental health remained under 10 until 2013, reaching 30 by 2017. In 2018, the annual publications surpassed 50, and in 2022, they exceeded 100. In the last 5 years (2018–2022), there were 370 publications on this topic, accounting for 79.05% of total publications during the thirteen-year period. Over a period of time, the number of articles and review articles increased from 113 to 324, and from 23 to 46, respectively. Furthermore, there were 12,322 citations from 2010 to 2022, with an average of 26.33 citations per publication. Citations from the last 5 years constituted 37.62% of the total citations. Figure 2 illustrates the publication and citation trends in the field of cyberbullying and mental health research, depicting a steady rise in both publications and citations. The earliest document, Wang et al.'s (2010) “Co-occurrence of Victimization from Five Subtypes of Bullying: Physical, Verbal, Social Exclusion, Spreading Rumors, and Cyber,” examined the co-occurrence of subtypes of peer victimization. It assessed victimization related to verbal, spreading rumors, social exclusion, and physical and cyberbullying. The study also found that male participants were more likely to become victims of all the subtypes of bullying.

Figure 2 . Publication and citation trend. Source: SCOPUS database.

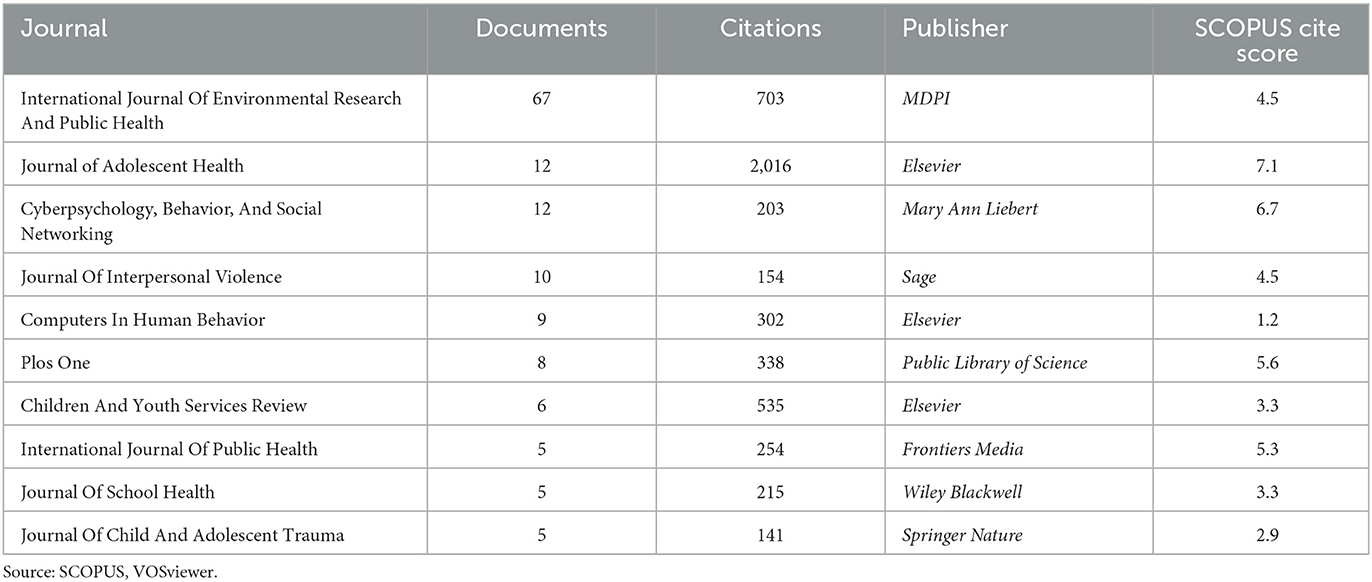

Journal analysis

Table 1 presents the top 10 journals based on the number of documents published. Out of 187 journals that have published at least one article on cyberbullying and mental health, only four journals had 10 or more publications on these topics. The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health had the highest number of publications (67) and citations (703). It is a multidisciplinary journal covering public health, occupational health, and psychology, and is published by MDPI. It is followed by the Journal of Adolescents Health with 12 publications and 2,016 citations. This journal is published by Elsevier and focuses on domains such as medicine, pediatrics, and public health. The third-ranked journal is the Children and Youth Services Review , with 535 citations. It is also published by Elsevier and has a multidisciplinary approach, primarily focusing on sociology, political sciences, and education. The majority of the top 10 journals publish multidisciplinary works, with an emphasis on behavioral sciences, social sciences, and adolescents, indicating the significance of cyberbullying and mental health in these fields. The only journal with more than 1 000 citations is the Journal of Adolescents Health (2 016 citations). It also has the highest citations per document score of 168. The journal with the second-highest citations per document score is the Children and Youth Services Review (89.17 citations per document). Lastly, it is worth noting that only a few studies on cyberbullying and mental health have been published in journals from renowned publishers such as the American Psychological Association (two publications), Taylor and Francis Ltd. (two publications), and Oxford University Press (one publication).

Table 1 . Top 10 most active journals.

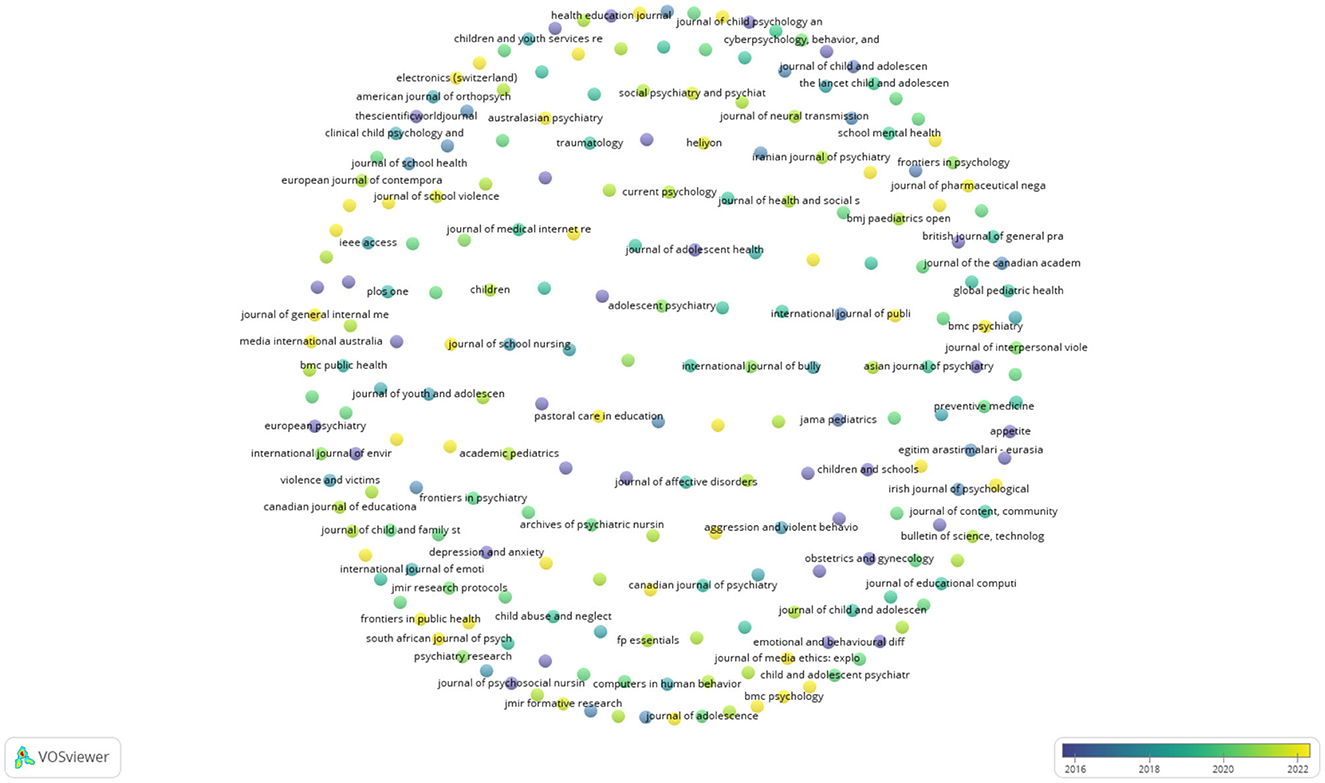

A journal overlay visualization ( Figure 3 ) was conducted to explore the emerging journals and the earliest journals published in the field. Another aim of journal overlay analysis was to determine the shift in research areas that journals publish on. The journals marked in yellow color is emerging journals in this field, whereas those marked in bluish-purple are the earliest journals published in the field. Journals such as the American Journal of Health Promotion, Australian Psychiatry, BMC Psychology , and Frontiers in Digital Health are emerging journals in the field, to name a few.

Figure 3 . Journal overlay map. Source: SCOPUS, VOSviewer.

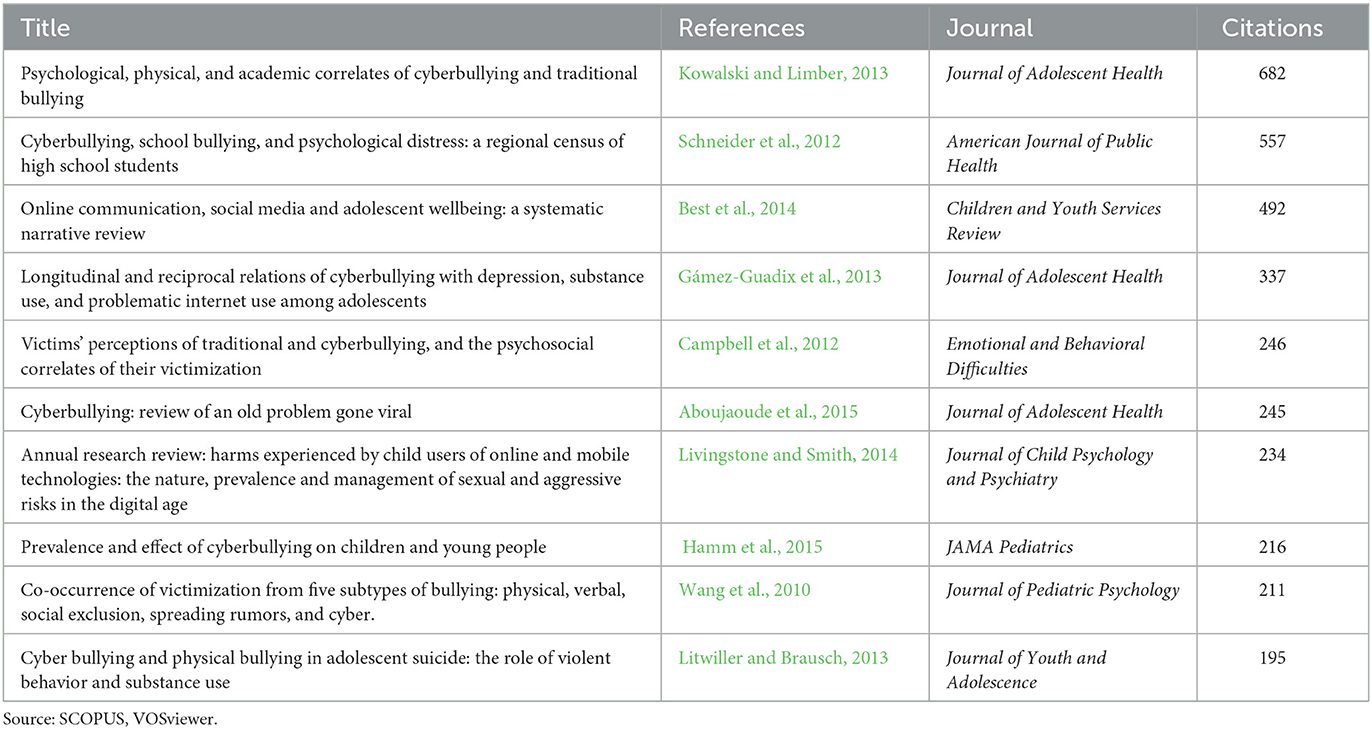

Top cited publications

The top 10 highly cited research articles in the SCOPUS database are presented in Table 2 . One of these articles, “Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying,” authored by Kowalski and Limber (2013) , aimed to analyze the relationship between experiences of cyberbullying and traditional bullying in children and adolescents, and their psychological and physical health as well as academic performance. They conducted a survey comprising of variables such as experiences with traditional bullying and cyberbullying, depression, anxiety, physical wellbeing, and academic performance ( Kowalski and Limber, 2013 ). Participants were divided into four cohorts: cyber victims, bullies, victims/bullies, and not involved in cyberbullying. A similar division was also made for traditional bullying. It was found that students in the victims/bullies' group had the worst scores for their psychological and physical health and academic performance, especially among male participants. In comparison, female participants were more likely to develop both traditional and cyberbullying-related anxiety. The results further highlighted that although cyber victimization and perpetration and traditional bullying victimization and perpetration positively correlated with anxiety, depression, lower self-esteem, suicidal ideation, absenteeism and leaving school early, victimization in both types of bullying was more significantly associated with these outcomes than perpetration. In other words, the study emphasized that victims of traditional and cyberbullying are more likely to develop anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation than perpetrators, especially in school learners.

Table 2 . Top 10 most influential publications.

The second most influential study is “Cyberbullying, School Bullying, and Psychological Distress: A Regional Census of High School Students,” authored by Schneider et al. (2012) . The authors aimed to analyze the relationship between cyberbullying and school bullying victimization and psychological distress ( Schneider et al., 2012 ). Results revealed that 59.7% of students who experienced cyberbullying were also the prey of school bullying, while 36.3% of students who experienced more school bullying were also victims of cyberbullying. Furthermore, results indicated that victims of both school and cyberbullying had significant associations with psychological distress. The tenth most influential publication, titled “Cyber bullying and physical bullying in adolescent suicide: the role of violent behavior and substance use” is authored by Litwiller and Brausch (2013) . The authors analyzed the relationship between physical and cyberbullying victimization and suicidal tendencies in adolescents, considering mediating variables such as violent and sexual behavior. The study's findings suggested that both types of bullying are highly associated with suicidal tendencies and unsafe sexual and violent behaviors. Additionally, the study highlighted an association between both types of bullying and substance abuse. Substance abuse and violent behavior acted as partial mediating variables. They explained “how risk behaviors can increase an adolescent's likelihood of suicidal behavior through habituation to physical pain and psychological anxiety” ( Litwiller and Brausch, 2013 , p. 675).

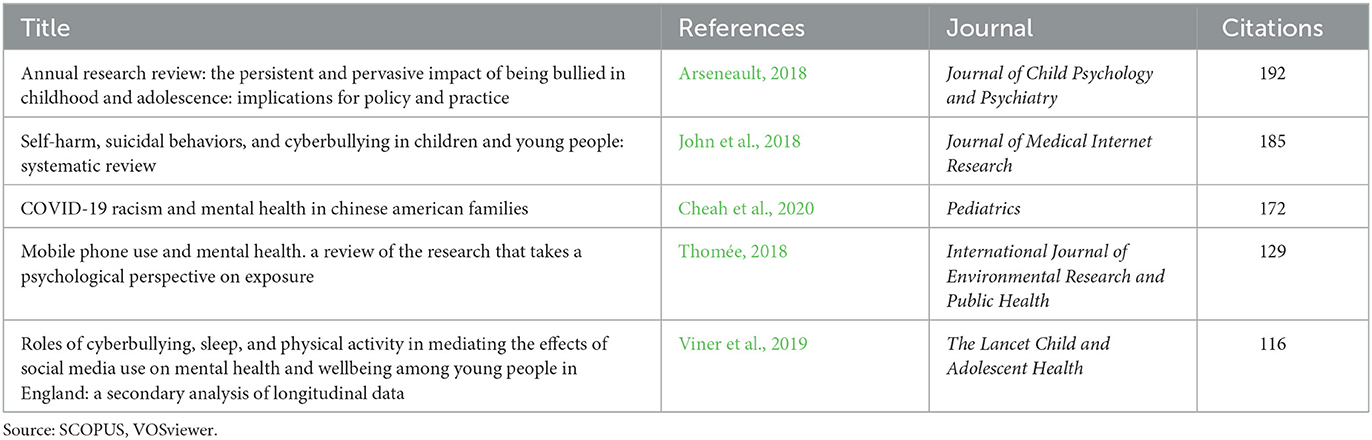

Table 3 illustrates the top five publications in the last 5 years, i.e., 2018 to 2022. At the top of the list is Arseneault's (2018) article titled “Annual Research Review: The persistent and pervasive impact of being bullied in childhood and adolescence: implications for policy and practice”. The article was published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and was cited 192 times. The study highlighted the impact of childhood bullying on mental and physical health as well as socio-economic outcomes. It demonstrated that childhood bullying, including traditional and cyberbullying, contributes to childhood and adolescent adjustment problems and may lead to poor mental and physical health, and the development of socio-economic difficulties. The study emphasized the importance of interventions against childhood bullying that focus on reducing symptoms-based problems in young victims. Furthermore, the study highlighted a need for developing individual level-based interventions to promote resilience against bullying behavior and reduce the risk of being vulnerable to bullying.

Table 3 . Top five publications in the last 5 years.

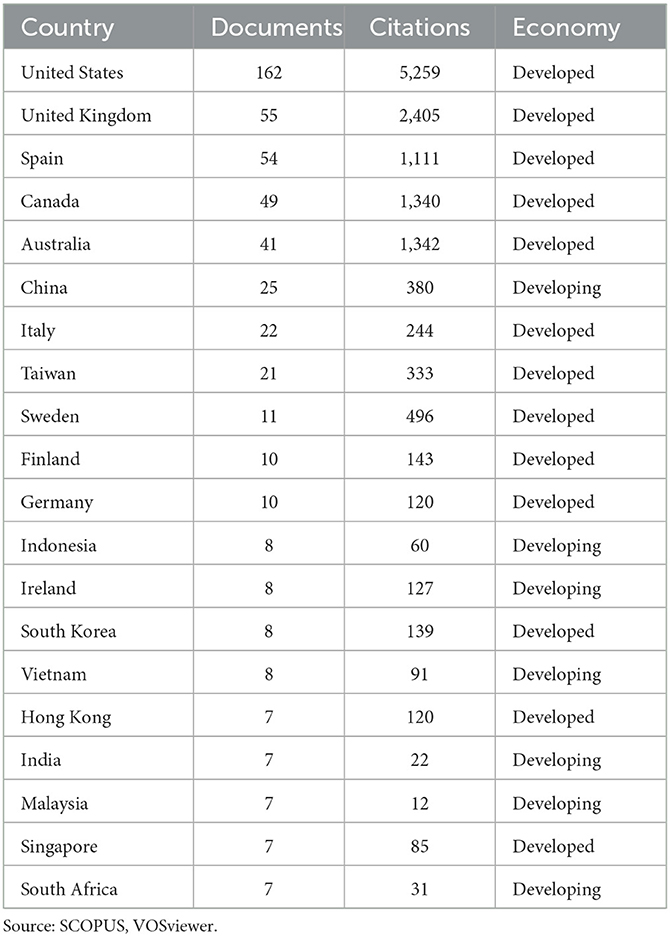

Country/region analysis

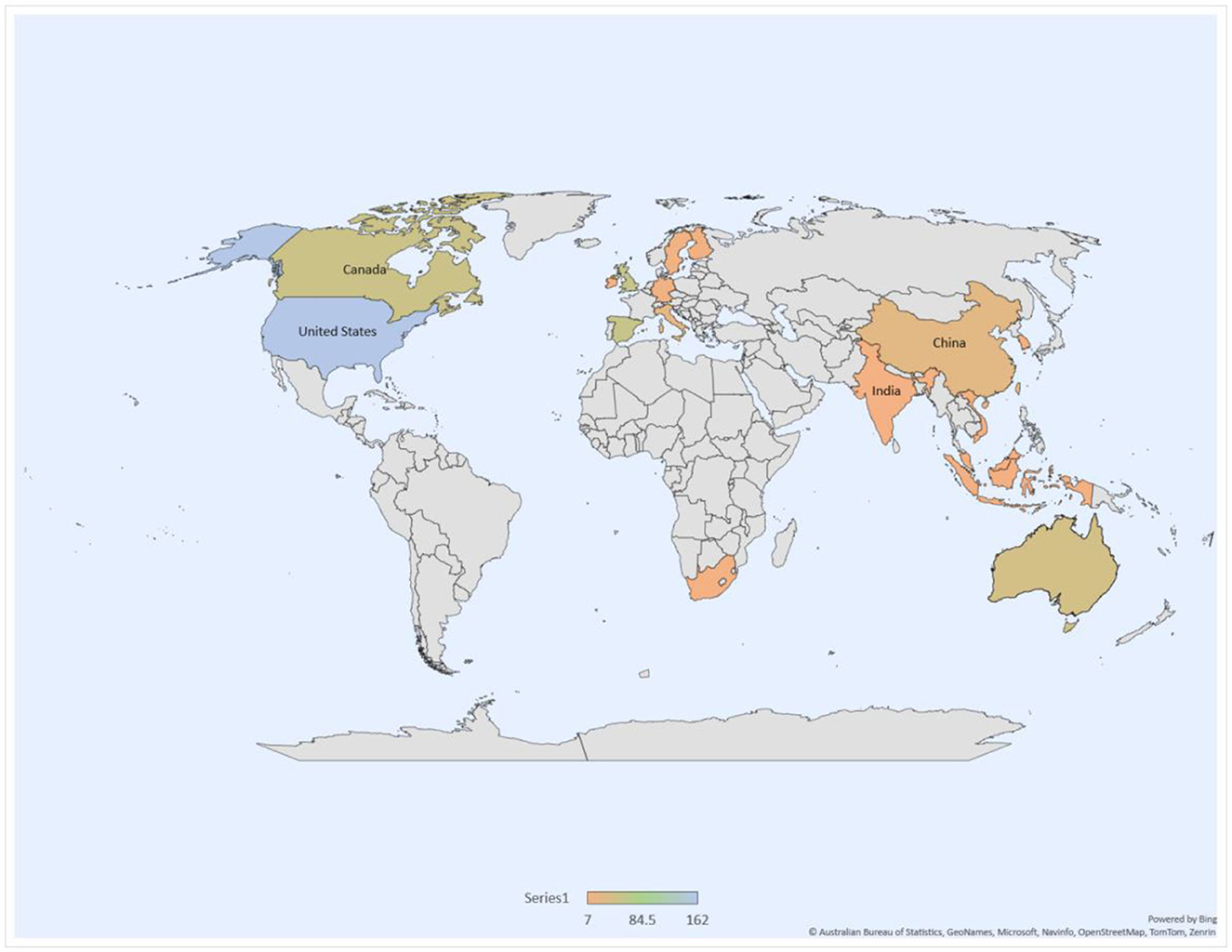

Table 4 and Figures 4 , 5 reports the top 20 countries/regions actively publishing in the cyberbullying and mental health domain. The SCOPUS database revealed that 75 countries have published 468 documents on this topic. The large number of countries involved suggests that cyberbullying and mental health have received global coverage and attention. It is interesting to note that 13 out of the top 20 countries are developed nations ( Figure 4 ). The United States of America (USA) tops the list with 162 publications and 5 259 citations. It is followed by the United Kingdom (UK) with 55 publications and 2,045 citations. These two countries are developed economies that have been utilizing advanced technologies, especially ICT. Moreover, cyberbullying was recognized and addressed in developed countries earlier to any other country ( Bansal et al., 2023a ). Also, the most influential authors on cyberbullying are from developed nations. P. K. Smith tops the list of most influential authors with 454 citations, followed by S. Hinduja (346) and J. W. Patchin (320). China leads the list of most active developing nations with 25 publications and 380 citations. Indonesia follows China with eight publications and 60 citations, followed by Ireland (eight publications and 127 citations), Vietnam (eight publications and 91 citations), India (seven publications and 22 citations) and South Africa (seven publications and 31 citations). While the difference in the number of publications and citations between developing and developed economies is justified by the level of ICT technology used, it does not present a clear picture of the situation. Moreover, it is not justified to conclude that developing countries like India and China are laggers in research on the topic. Therefore, VOSviewer was used for purposes of this research to conduct a country overlay mapping to explore which are the emerging countries based on their paper publication year.

Table 4 . Top 20 countries publishing on cyberbullying and mental health.

Figure 4 . Country map. Source: SCOPUS database, VOSviewer.

Figure 5 . Country overlay map. Source: SCOPUS, VOSviewer.

The results of the country overlay mapping process categorize countries in five different colors. Dark bluish-purple presents the countries that have been active in this field for a very long time, whereas countries in yellow are the emerging countries. As expected, India and China are marked in yellow, suggesting a rise in research on cyberbullying and mental health in emerging countries. Interestingly, it also provides further insights, for example countries marked in dark bluish-purple color are countries with developed economies and with substantial literature based on the subject, as they have been publishing works for several years. On the other hand, countries marked in yellow represent developing economies that are emerging in this field. The ICT advances and the creation of early awareness regarding the impact of cyberbullying on mental health are a few differentiating factors between developing and developed economies. Figure 5 presents a country overlay analysis.

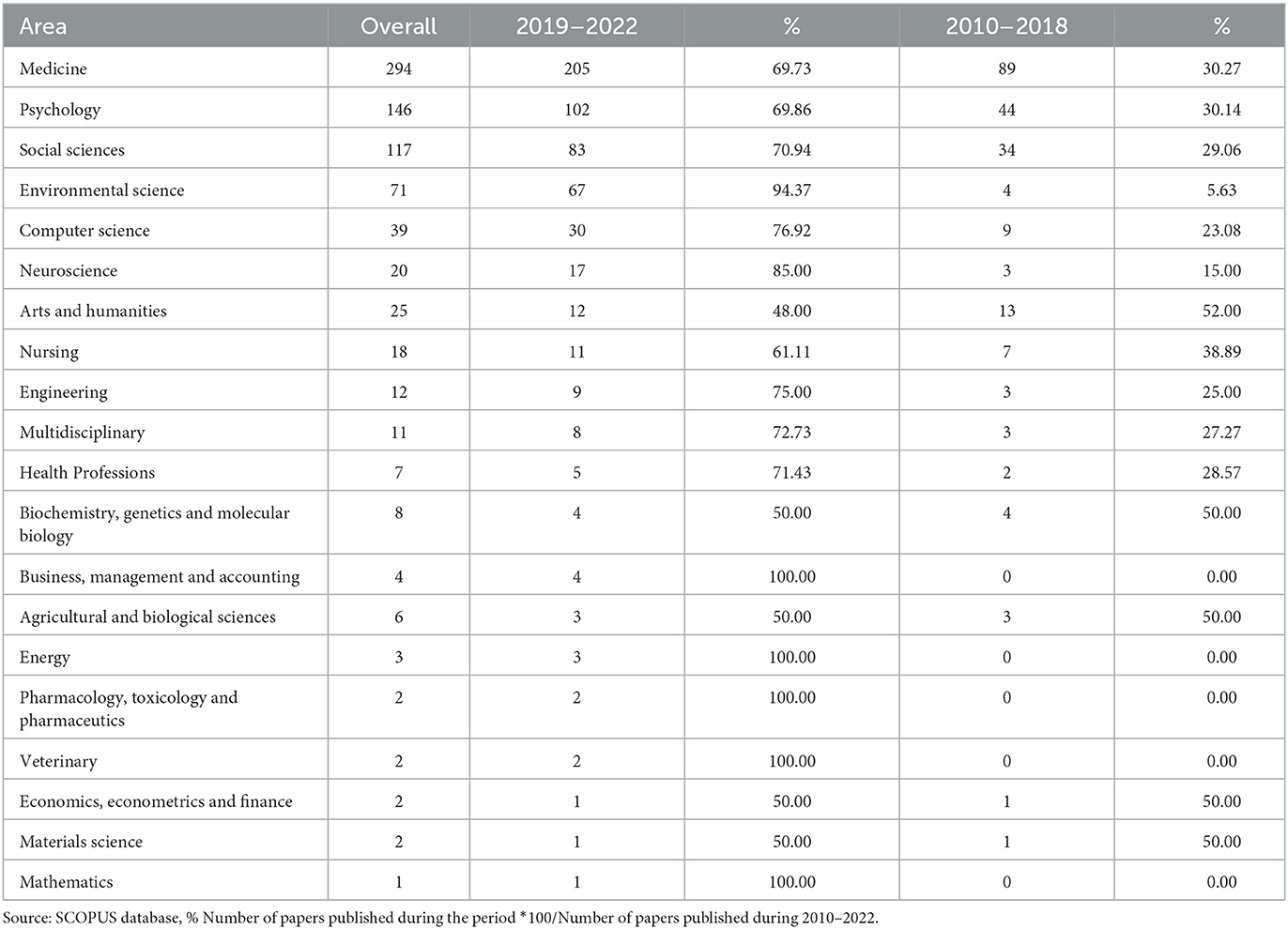

Research area analysis

Table 5 presents the research areas in which studies on cyberbullying and its impact on mental health are being conducted. Medicine has the primary coverage with 36.9% of studies, followed by psychology with 19.1%, and social sciences (14.9%). Other major research areas include environmental science (9.0%), computer science (4.9%), arts and humanities (3.2%) and neuroscience (2.5%), to name a few. The results suggest that although most of the studies were conducted in the medical domain, there are cyberbullying and mental health researchers in other areas such as psychology, social sciences, environmental science, and computer science. Table 5 also reports a comparison between documents published in different research field in two-time frames, i.e. 2010–2018 and 2019–2022. It reports a percentage increase in the publication from 2010–2018 to 2019–2022 in research areas such as medicine, psychology, social sciences, environmental science, computer science, neuroscience, nursing, and engineering. It also reports a percentage decline in arts and humanities research areas during the same period. The table further illustrates the emergence of new research areas, namely business, management and accounting, energy, pharmacology, toxicology and pharmaceutics, and mathematics during 2019–2022. The results suggest that contemporary researchers appear more interested in analyzing medicinal and psychological aspects of cyberbullying and mental health along with developing interests in organizational aspects.

Table 5 . Research areas.

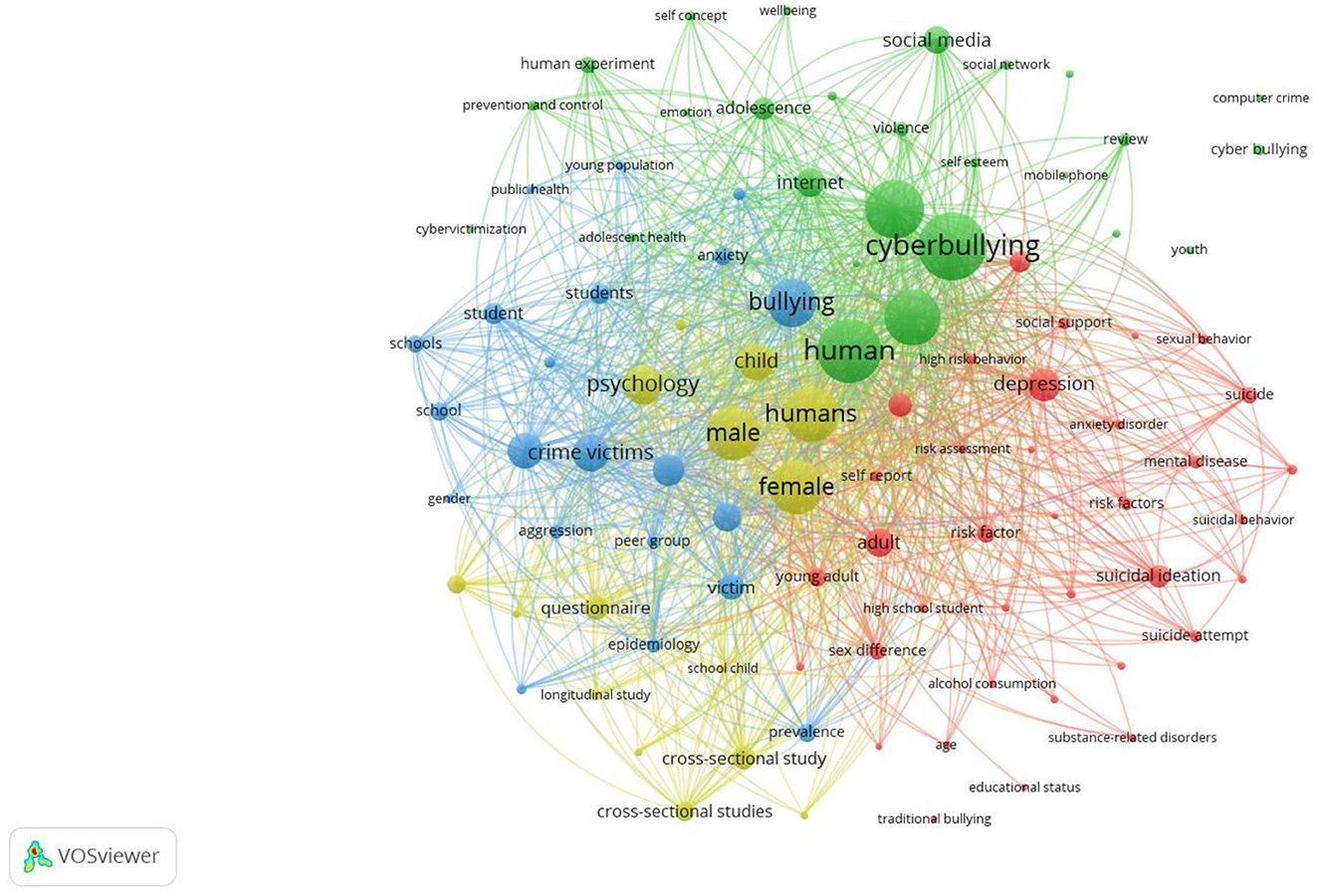

Topical analysis

Figure 6 illustrate the topical analysis based on keywords co-occurrence analysis, which suggest that 98 out of 2 420 keyword topics met the threshold criteria of 15 co-occurrences per keyword. The prominent keywords were cyberbullying (353 occurrences) followed by human (324 occurrences), mental health (228 occurrences), adolescent (268 occurrences), and humans (265 occurrences), male (254 occurrences), and female (254 occurrences). The keyword visualization map highlighted five major clusters based on their link to strength co-occurrence.

Figure 6 . Keyword network visualization. Source: SCOPUS, VOSviewer.

Cluster 1: early studies on cyberbullying and mental health

This cluster (in green color) includes keywords such as cyberbullying, human, mental health, adolescent, internet, prevention and control, adolescent health, etcetera. It appears to comprise early studies that theorized cyberbullying and mental health. For example, Wang et al. (2010) analyzed and recognized cyberbullying as a subtype of bullying. Williams and Godfrey (2011) conceptualized how psychiatric-mental health nurses can recognize cyberbullying. Keung (2011) assessed the relationship between internet addiction and antisocial internet behavior like cyberbullying in adolescents. Goebert et al. (2011) explored the relationship between cyberbullying, substance abuse, and mental health. Additionally, this cluster includes publications studying coping behaviors and the need to develop preventive measures against degraded mental health due to cyberbullying. For instance, school students try to cope with cyberbullying in three ways: reactive, preventive, and in no way to prevent cyberbullying ( Parris et al., 2012 ). Reactive coping strategy may involve ignoring or deleting bullying messages, while preventing coping strategies may involve seeking help or increasing awareness about their security. The study further highlighted that when these strategies fail, students feel defenseless and that there is no way to reduce cyberbullying. Furthermore, Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton (2015) highlighted the need to develop preventive interventions against cyberbullying. Their study suggested that cyberbullying victimization mediated the relationship between the use of social networking sites (SNS), psychological distress and suicidal ideations.

Cluster 2: gender in cyberbullying and mental health

The yellow-colored cluster contains keywords such as humans (265 occurrences), female (254 occurrences), male (254 occurrences), psychology (167 occurrences), child (147 occurrences), sex factors (20 occurrences), etcetera. It seems to present studies on gender-based differences in cyberbullying and mental health, often referred to as the gender debate cluster. This cluster contains studies contributing to the ongoing gender-based debate on cyberbullying and mental health. Various researchers have presented differing views on gender-based differences affecting cyberbullying and mental health. For example, Bannink et al. (2014) suggested that male participants showed resilience toward cyberbullying victimization, thereby not developing any mental health problems, whereas it was the opposite in the case of females. Merrill and Hanson (2016) also suggested higher cyberbullying victimization in female participants than in males, and that females sometimes bully other females as a way to release their mental pressure and emotional bursts. On the other hand, Kim et al. (2019) suggested a higher direct effect of cyberbullying victimization on depression in males compared to females. Hood and Duffy (2018) contributed to this debate by revealing that gender differences did not affect the cyberbullying intentions of adolescents. Fletcher et al. (2014) also reported no association of gender with cyberbullying in school learners. Additionally, this cluster consists of longitudinal studies that examine the relationship between cyberbullying and mental health over time. For instance, one of these longitudinal studies predicts cyber victimization in year one followed by developing anxiety in the following year. Similar results were predicted for cybervictimization in year two and anxiety in the following year. Another longitudinal study found a significant moderating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between homophobic cyberbullying, depression, and anxiety ( Wright et al., 2022 ).

Cluster 3: clinical and criminal studies on cyberbullying and mental health

This cluster in blue color illustrates studies related to clinical assessments and criminology on cyberbullying and mental health. Some of the keywords are bullying (219 occurrences), crime victims (147 occurrences), major clinical studies (105 occurrences), offender (24 occurrences), etcetera. One of the studies in the field of criminology suggested no significant differences in psychosomatic issues between victims of cyberbullying and traditional bullying ( Beckman et al., 2012 ). Paat and Markham's (2020) review study highlighted the modern-day cyber risks teenagers face, particularly focusing on the hidden dangers associated with cyberbullying, SNSs, cyberdating, and sexting, aiming to raise awareness about these crimes. Another clinical study analyzed the frequency of cyberbullying as a contributing factor to youth suicide in Canada ( Cénat et al., 2015 ). Though cyberbullying was not directly associated with suicide-related deaths, the presence of other mental health issues combined with traditional bullying and cyberbullying contributed to a higher prevalence of identified mental health issues, increasing the risk of suicide attempts and, in some cases, resulting in death ( Cénat et al., 2015 ). Patchin and Hinduja (2017) , two prominent authors in the field of cyberbullying, conducted a study to analyze the prevalence of digital self-harm in adolescents. They suggested that males were more likely to engage in digital self-harm activities than females. They also highlighted various factors including sexual orientation, experience with cyberbullying and depressive symptoms which significantly correlated with digital self-harm in adolescents.

Cluster 4: associating cyberbullying with mental health

This cluster in red color presents studies that have expanded the literature on cyberbullying and mental health. These studies have used more robust statistical methods to study various variables' moderation and mediation effects on the relationship between cyberbullying and mental health. Some of the keywords present in this cluster are depression (127 occurrences), adult (106 occurrences), and social support (33 occurrences). Feinstein et al. (2014) suggested that rumination significantly mediated the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and depressive symptoms in women. Elgar et al. (2014) examined the importance of family dinners, specifically family communication and contacts, in mitigating the negative impacts of cyberbullying victimization on mental health. They suggested that improved family communication helps alleviate mental stress and reduces suicidal tendencies, depression, and anxiety in cyberbullying victims. Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton (2015) highlighted the need to explore the use of social networking sites in light of cyberbullying victimization to prevent adolescents' mental health issues. They also suggested that cyberbullying victimization mediates the linkages between social networking sites usage and mental health issues such as psychological distress and suicide attempts. Yu and Chao (2016) suggested that internet addiction significantly moderates the relationship between cyberbullying, cyber-pornography, and mental health. They suggested that parents and academics regulate the digital behavior of adolescents and guide them to use the internet better. Lin et al. (2022) indicated that people with higher resilience scores are well protected against depression resulting from cyberbullying victimization. Hence, studies clearly showed the importance of studying individual-level interventions to protect against cyberbullying and resulting mental issues.

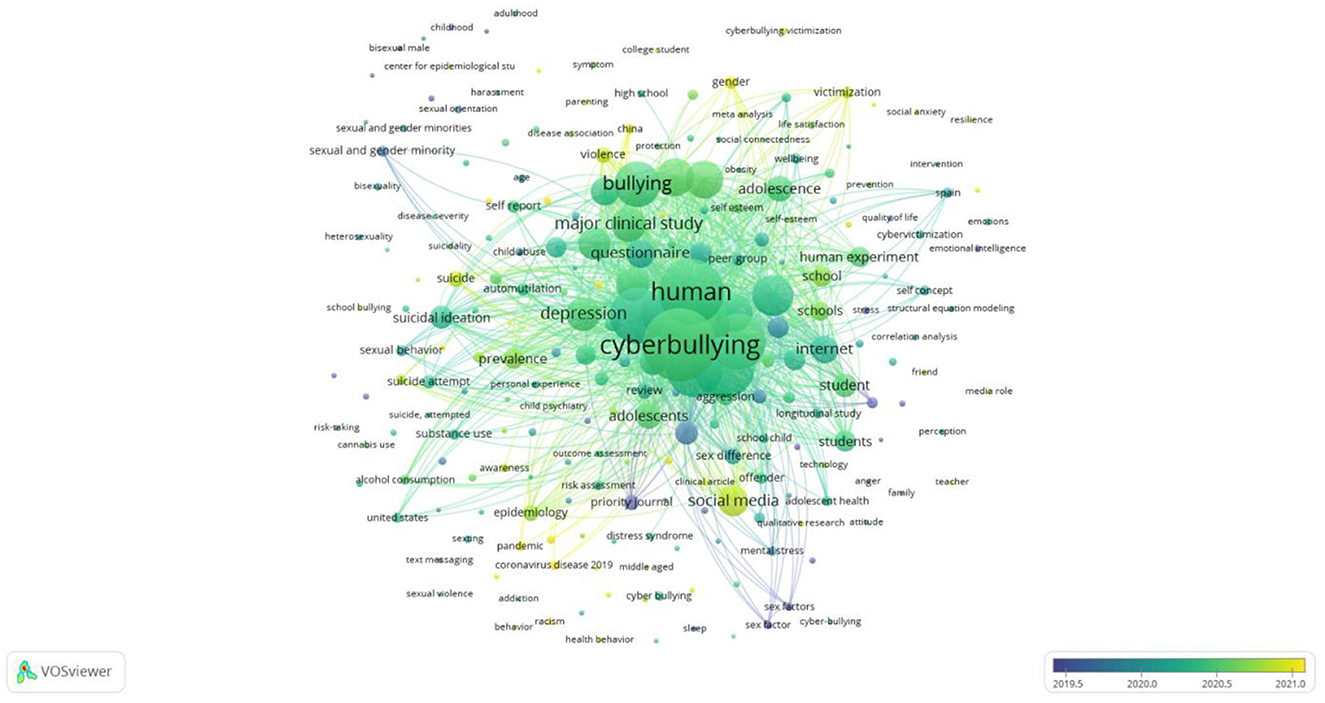

Recent trends

Figure 7 represents the keyword overlay map of emerging topics and evolution/shifts in topics during the last 5 years, i.e., 2018–2022. Again, clusters are formed but based on the time of occurrence of keywords. Keywords presented in yellow and light-green colors indicate the emerging topics.

Figure 7 . Keyword overlay map. Source: SCOPUS, VOSviewer.

Cluster 1: most emerging cluster

This yellow-colored cluster presents the most emerging topics on cyberbullying and mental health. This cluster has keywords such as social anxiety, racism, pandemics, physiological distress, COVID-19, college students, workplace, etc. According to Hou et al. (2022) , there has been an increase in cyberbullying cases due to increased screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies on college students suggest that the unguided authority to surf the internet has made the collegiate to fall prey to cyberbullies or, in some cases, become one, knowingly or unknowingly ( Naik et al., 2021 ). Bansal et al. (2023a) also reported a positive correlation between depressive symptoms and cyberbullying perpetration in college students. Moreover, Baiden et al. (2022) and Cheah et al. (2020) indicated that racial minorities experience online discrimination, which contributes to increased mental health issues. Cheah et al. (2020) further recommended that healthcare professionals pay special attention to victims of online discrimination during COVID-19.

Cluster 2: second most emerging cluster

This parrot-green colored cluster includes studies on the second most emerging topics. It contains keywords such as social media, prevalence, violence, epidemiology, suicide, and gender. For example, Tamarit et al. (2021) explored the relationship between social network sites' addiction, self-esteem and sexo-erotic risk behavior like sexting and grooming in adolescents. Their findings also suggest that online addiction predicts sexo-erotic behavior, and such behavior is moderated by self-esteem. Rakic et al. (2021) suggest that individual and family factors including gender and family affluence status predict cyberbullying exposure in Serbian school students. Marengo et al. (2021) examined the occurrences of cyberbullying and problematic social media use in school students. They found that the risk of being cyber-victimized was higher when problematic social media use was present, and the reports of such cases were higher in female students than in males.

Cluster 3: interventions for cyberbullying and mental health

This cluster in teal color contains studies on preventing the degradation of mental health due to cyberbullying. This cluster contains words such as life satisfaction, prevention, mental health, cybervictimization, interventions, etcetera. Several studies have discussed interventions aimed at preventing cyberbullying and promoting sound mental health. For instance, Yosep et al. (2022) and Berardelli et al. (2018) explored and reviewed the literature on interventions that can decrease cyberbullying incidences and mitigate its negative effects on mental health. Yosep et al. (2022) suggested that nursing interventions such as prevention activities, peer-group support, and resilience programs can assist to reduce the occurrence of cyberbullying incidences and help improve mental health. Further, Berardelli et al. (2018) found that lifestyle behavior including cyberbullying, substance abuse, low exercise, and poor diet can severely affect mental health. They indicated that community-wide programs such as social skills training and psychoeducational family treatments can act as interventions against such behaviors and help elevate mental health. Myers and Cowie (2019) reviewed the fragmented literature on cyberbullying victimization in educational institutions and suggested some helpful interventions. They emphasized that educational institutions might adopt social and emotional learning programs to enhance emotional intelligence and empathy among students. The authors also highlighted Smith et al.'s (2016) restorative methods to create a co-operative and positive environment in schools, fostering positive relationships and bolstering the participation of academics and students in implementing such methods.

Cluster 4: adolescents and research techniques

This bluish-purple cluster presents studies on adolescent behavior and data gathering techniques. Keywords include adolescent behavior, surveys and questionnaires, psychological wellbeing, priority journal, internet addiction, mental disorders, sexual and gender minority. Various researchers including Barlett et al. (2016) , Cavalcanti et al. (2019) , Bansal et al. (2022) , Tanrikulu and Erdur-Baker (2021) and Reif et al. (2021) have explored the psychometric properties of various scales or inventories measuring cyberbullying in countries like the USA, Brazil, India, Turkey, Spain and Germany, respectively. Studies within this cluster also investigate and suggest the associations between cyber intimate partner victimization and alcohol use ( Trujillo et al., 2020 ), the relationship between cyberbullying experiences, gender, and depression ( Alrajeh et al., 2021 ). Additionally, authors like Reed et al. (2019) suggest that cyber sexual harassment from unknown males is prevalent among teenage girls and negatively affects their mental wellbeing. Some participants from their study also reported the prevalence of cyber sexual harassment from known males.

Studies have shown that cyberbullying has severely affected both the victims' and bullies' physical and mental wellbeing ( Kowalski et al., 2014 ; Bansal et al., 2023a ). For instance, incidences of cyberbullying have led to the development of psychological issues such as depression ( Litwiller and Brausch, 2013 ), and suicidal thoughts ( Islam et al., 2021 ). Therefore, numerous researchers have made significant contributions to the literature in order to deepen our understanding of the phenomenon and to explore various aspects, including prevention and interventions. Consequently, a vast body of knowledge has been generated, examining cyberbullying from different perspective such as economics, adolescents, and mental health. This vast literature has provided valuable insights through literature reviews, systematic literature reviews, meta-analyses, and bibliometric analyses. Although these studies have deepened our understanding, they have their own limitations. Hence, this study analyzed the academic performance of research articles through a qualitative bibliometric analysis of cyberbullying and mental health. It explores the development of knowledge in the field of cyberbullying and mental health. Lastly, this study was based on the suggestions and guidelines provided by Donthu et al. (2021) in relation to identifying trends in a field of study through the analysis of published literature.

The very first question answered was based on analyzing the publication and citation trends. Initially, there were < 10 publications per year on the link between cyberbullying and mental health, which increased over a period of time. Similarly, the cumulative citations have also increased to 12,322 by 2022. There could be various reasons for these results. During the initial years of research on cyberbullying, researchers focused on understanding the phenomenon of cyberbullying ( Kowalski et al., 2014 ). Also, during those years, present-day ICT infrastructure was developing, and few people had access to such infrastructure. After the advancements in SNS and ICT, the world saw a boom in ICT ( Yang and Hu, 2019 ). Furthermore, the rise of social media, attributed by the availability of ICT tools and wider accessibility of internet services, made many people spend their time on online activities. This rendered an opportunity for the cyberbullies to deter their acts ( Chan et al., 2019 ). This trend was fuelled further by the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions on social and outdoor activities and the shift of study and workplace from offline to online during the pandemic caused people to increase their screen time ( Singh et al., 2021 ). Due to increased screen time, people fell prey to the hands of cyber bullies, especially the younger generation ( Bansal et al., 2023a ). Zhu et al. (2021) and Han et al. (2021) state that cyberbullying during COVID-19 also contributed to increased mental health issues, including anxiety and depression. These reasons supported the advancements in the research from understanding the phenomenon of cyberbullying to studying its consequences, specifically understanding its impact on the mental health of its victims and perpetrators ( Kowalski et al., 2018 ).

Next, a journal analysis was conducted. The most influential journals and emerging journals were identified. The researchers aimed to determine a shift in the publication area of these identified journals. The Journal of Adolescents Health ranked first with 2 016 citations, followed by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (703 citations) and the Children and Youth Services Review (535 citations). With the help of overlay analysis, the emerging journals were identified and marked in yellow. The American Journal of Health Promotion, Australian Psychiatry, BMC Psychology, and Frontiers in Digital Health are some of the emerging journals. The overlay analysis was also used to explore the shift in the preferred research areas which journals publish. The earlier journals, like the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, focused on publishing studies related to cyberbullying, the psychological wellbeing of children and youth, and social work practices. The studies published in these journals analyzed cyberbullying not only as a single but also explored its associations with other fields, including medicine and social sciences. This made these fields the best possible fields to conduct research on cyberbullying. Hence, the multidisciplinary nature of these journals confirms that cyberbullying is a multidisciplinary phenomenon with vast future potential for researchers.