- Current Issue

- Back Issues

- Article Topics

- ASN Events Calendar

- 2024 Leadership Awards Reception

- Editorial Calendar

- Submit an Article

- Sign Up For E-Newsletter

Social Problem Solving: Best Practices for Youth with ASD

- By: Michael Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP Behavior Therapy Associates

- July 1st, 2014

- assessment , problem solving , social information processing , social skills

- 9238 0

Joey, age 9, has been diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and due to his high functioning has been mainstreamed into a fourth grade classroom with a shadow. His […]

Joey, age 9, has been diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and due to his high functioning has been mainstreamed into a fourth grade classroom with a shadow. His challenging behaviors typically center on his peer interactions in spite of adequate academic performance. When in a group situation he becomes very argumentative when his ideas are not used, becomes very bossy on the playground, and has run out of the classroom when things do not go his way. Megan, age 14, has also been diagnosed with ASD. She isolates herself from her peers and rarely initiates or responds to greetings. Conversations are almost nonexistent unless they are focused on her favorite topics of anime or fashion.

Children with ASD described as above typically have significant social skills impairments and often require direct instruction in order to address these deficits. They often have difficulty in many of the following areas: sharing, handling frustration, controlling their temper, ending arguments calmly, responding to teasing, making/keeping friends, complying with requests. Strong social skills contribute to the initiation and maintenance of positive relationships with others and as a result contribute to peer acceptance. Social skills impairments, on the other hand, contribute to peer rejection. The ability to get along with peers, therefore, is as important to self-esteem as the ability to meet with academic success in the classroom. This article will review the domain of social skills, the assessment of social skills, the importance of social problem-solving and a social skills curriculum which incorporates evidence-based practices to address this very important area.

Social information processing (SIP) is a widely-studied framework for understanding why some children have difficulty getting along with peers. A particularly well-known SIP model developed by Crick and Dodge (1994) describes six stages of information processing that children cycle through when evaluating a particular social situation: encoding (attending to and encoding the relevant cues), interpreting (making a judgment about what is going on), clarifying goals (deciding what their goal is in the particular situation), generating responses (identifying different behavioral strategies for attaining the decided upon goal), deciding on the response (evaluating the likelihood that each potential strategy will help reach their goal and choosing which strategy to implement), and performing the response (doing the chosen response). It is assumed that the steps outlined above operate in real time and frequently outside of conscious awareness. Numerous studies have shown that unpopular children have deficits at multiple stages of the SIP model. For example, they frequently attend to fewer social cues before deciding on peers’ intent, are more likely to assume that peers have acted towards them with hostile intent, are less likely to adopt pro-social goals, are more likely to access aggressive strategies for handling potential conflicts, evaluate aggressive responses more favorably, and are less skillful at enacting assertive and prosocial strategies.

Deficits in social skills are one of the defining characteristics of children with ASD. These impairments manifest in making and keeping friends, communicating feelings appropriately, demonstrating self-control, controlling emotions, solving social problems, managing anger, and generalizing learned social skills across settings. Elliott and Gresham (1991) indicated that social skills are primarily acquired through learning (observation, modeling, rehearsal, & feedback); comprise specific, discrete verbal and nonverbal behaviors; entail both effective and appropriate initiations and responses; maximize social reinforcement; are influenced by characteristics of environment; and that deficits/excesses in social performance can be specified and targeted for intervention. Social skills can be conceptualized as a narrow, discrete response (i.e., initiating a greeting) or as a broader set of skills associated with social problem solving. The former approach results in the generation of an endless list of discrete skills that are assessed for their presence/absence and are then targeted for instruction. Although this approach has an intuitive appeal and is easily understood, the child can easily become dependent on the teacher/parent in order to learn each skill.

An alternative approach focuses on teaching a problem solving model that the child is able to apply independently. Rather than focusing on teaching a specific behavioral skill, the focus is on teaching a social problem solving model that the learner would be able to use as a “tool box.” The well-used saying “give a person a fish and she eats for a day but teach her to fish and she eats for a lifetime” is particularly relevant. The social problem solving approach offers the promise of helping the child with ASD to become a better problem solver, thereby promoting greater independence in social situations and throughout life.

After many years of conducting social skills training using the specific skill approach, the authors have developed a model of social problem solving that uses the easily learned acronym of POWER. The steps of POWER-Solving® include:

P ut problem into words

O bserve feelings

W ork out your goal

E xplore solutions

R eview plan

Each of the five steps of POWER-Solving® has been previously identified as reliably distinguishing between children with emotional/behavioral disorders and psychologically well-adjusted individuals. The ability to “Put problem into words” is critical in order to start the problem solving process. Children with ASD often have difficulties finding the words to identify a problem. Thus, the first step in this approach involves direct training in the use of the rubric “I was… and then…” Upon entering the classroom and finding a peer in his seat Joey immediately pushed the peer in an attempt to get him out of his seat. Through the use of POWER-Solving® Joey was taught to articulate “I was walking into the classroom and then I saw that Billy was in my seat.”

The second step of “Observe feelings” was addressed by helping Joey develop a feelings vocabulary (e.g., angry, frustrated, scared, sad) as well as measuring the intensity of these emotions using a scale from one to ten, with a one being “very weak” and a ten being “very strong.” Photographs and drawings were used extensively to capitalize on his strong visual skills.

The third step of POWER-Solving®, “Work out your goal?” involves identifying the goal and the motivation to reach the chosen goal. This critical step sets the stage for what follows. The goal must be specific and measurable, consistent with Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) principles. Joey was able to identify that his goal consisted of two parts. First, he wanted to get Billy out of his seat and second, he wanted him to still be his friend. He reported that his desire to reach this goal was a nine on the ten-point scale.

The fourth step of POWER-Solving® involves “Explore solutions.” Socially skilled individuals are able to generate a range of effective solutions but those with impairments are more limited and often apply the same rigid solution over and over again in spite of repeated ineffectiveness. Joey was taught to “brainstorm,” which involves generating as many solutions as possible that might reach the stated goal, provided the solution is safe, fair, and effective. Joey was able to identify that approaching Billy and saying “Excuse me but I need to sit in my seat now” would help him to accomplish his goal(s). Behavioral rehearsal, combined with coaching and feedback, helped Joey to become fluent in applying this solution.

The final step of POWER-Solving®, “Review plan,” involved Joey reviewing his plan to use this skill the next time the situation presented and to reward himself by saying “I am proud of myself for figuring this out.”

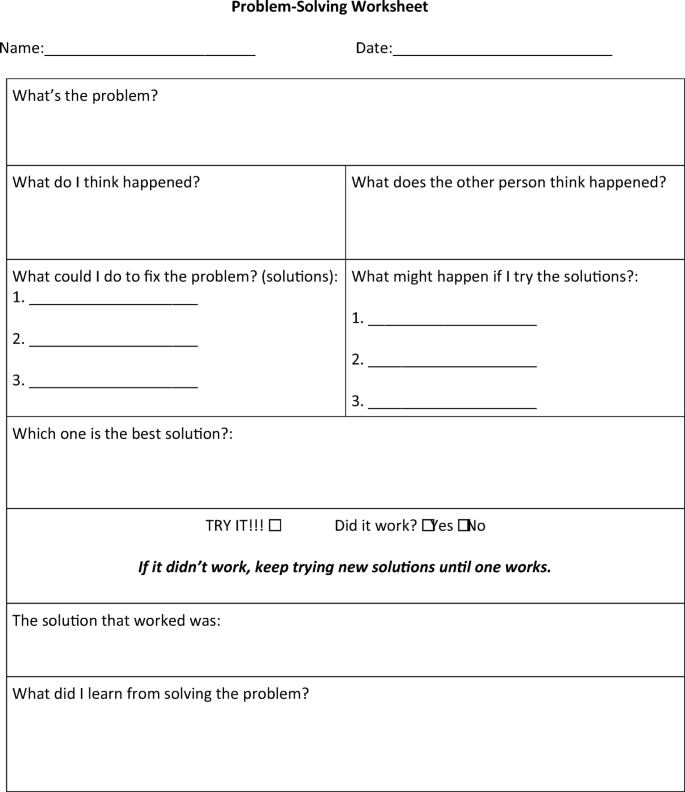

POWER-Solving® has been applied successfully in multiple settings such as the classroom, a summer treatment program, clinical settings and home environments. The curriculum is systematic and relies heavily on visual cues and supports. Children are taught how to problem-solve first using their “toolbox” (i.e., the five steps of POWER-Solving®). The children are presented with specific unit lessons on each of the five steps of POWER-Solving®. All children have an opportunity to practice each step of POWER-Solving®. After learning each step of POWER, the children have acquired a “toolbox” which they can begin to apply to social situations.

When teaching social skills, it is important to coach the children through behavioral rehearsal activities to promote skill acquisition, performance, generalization and fluency. Additionally, daily activities reinforce these skills, some of which include designing their own feelings thermometer, developing novel products via group collaboration, and developing a skit to teach a specific skill.

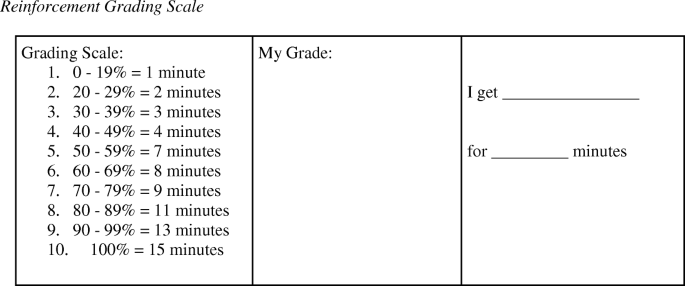

To increase students’ performance of the desired skills, use of a token economy may be helpful, whereby points are earned during the day for displaying appropriate behavior, demonstrating a predetermined individualized social behavioral objective and for using the POWER-Solving® steps. At the end of every day, points could be exchanged for a reward. In addition to the direct instructional format, incidental teaching should be used in anticipation of a challenging situation as well as a consequence for failure to use the steps when confronted with a specific problem. An experienced social skills coach, generalization strategies, and a systematic plan to teach and reinforce skills are critical for success.

Please feel free to contact us at Behavior Therapy Associates for more information about best practices for social skills training, as well as information regarding the POWER-Solving curriculum. We can be reached at 732-873-1212, via email [email protected] or on website at www.BehaviorTherapyAssociates.com .

Crick, N.R., & Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin , 115, 74–101.

Elliott, S.T. & Gresham, F. M. (1991). Social skills intervention guide: Practical strategies for social skills training . Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Related Articles

Using media as an effective tool to teach social skills to adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders.

Media is a powerful educational tool for adolescents and young adults in general; however, for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) it provides a unique opportunity to learn social skills. […]

The Importance of Socialization for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are defined by three main components/deficits. These are deficits in Communication (receptive/expressive speech and language delay), Behaviors (aka self-stimulatory behaviors or stimming) and Socialization. Communication: these […]

Teaching Social Skills – A Key to Success

As young adults with autism transition from high school to college, work or independent living, they need to have good social skills in order to make friends, engage colleagues and […]

Places for Persons with Asperger’s to Meet People

There are many places where persons with Asperger’s can meet people, but too often they don’t know where they can comfortably and satisfactorily do this. Bars, cocktail parties, and other […]

I Finally Feel Like I Belong

I was one of the unpopular kids. I was never invited to birthday parties or sleepovers. I had no friends, and no one wanted to hang out with me. I […]

Have a Question?

Have a comment.

You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Individuals, Families, and Service Providers

View our extensive library of over 1,500 articles for vital autism education, information, support, advocacy, and quality resources

Reach an Engaged Autism Readership Over the past year, the ASN website has had 600,000 pageviews and 425,000 unique readers. ASN has over 60,000 social media followers

View the Current Issue

ASN Summer 2024 Issue "Supporting Autism Service Providers"

10 Achievable IEP Goals for Autism With Action Steps

An Individualized Education Program (IEP) is an educational plan written to support students with learning disabilities. These documents include goals for the student to work towards during the academic year, as well as what supports are needed to meet these goals. For an IEP to be effective and meaningful, a team of professionals works with families to create highly individualized goals for the student. Here, we will discuss the importance of IEP goals, how to write a strong IEP, who should be involved, and how to track progress to ensure the goals are being met.

The Importance of IEPs for Students with Autism

Essential areas to address in iep goals, academic skills development, expressive language skills, promoting emotional regulation and self-control, promoting life skills for future success, monitoring and reviewing progress, individualized instruction and accommodations, understanding individualized education programs (ieps).

An IEP is a personalized plan developed for students with disabilities, including autism. IEPs are part of the Disabilities Education Act to help protect and support students who are struggling educationally. An IEP should cover all aspects of the student’s special education program, including educational goals, supports, and services that the student will need to help them achieve these objectives.

IEPs are created for each student and should be tailored to highlight their learning gaps, skills, and learning styles. IEPs are created through a collaborative effort involving teachers, parents, special education professionals, and other relevant educational team members. This multidisciplinary team works together to develop the goals and strategies for the student, and each member provides a unique insight and perspective. If possible, the student should participate in the IEP process to allow them to self-advocate, identify their areas of improvement, and help with goal creation.

Students with autism can learn and acquire new skills but need specific support to help them learn. IEPs cover academic, social, and behavioral concerns and gross and fine motor skills. A lack of IEP is not only against the law but will result in the child falling further behind in their education and likely increasing challenging behaviors.

As autism is a spectrum condition, it affects each student differently and will impact their learning in individual ways. As such, the IEP should be tailored to each individual, including their unique set of challenges and strengths, as well as the child’s learning style, sensory sensitivities, supports, likes, dislikes, etc. As IEPs are so individualized, having parents collaborate and work jointly with educators is essential to help create the most effective IEPs, as they can provide their unique insight.

Setting Effective IEP Goals

Key Considerations for Setting IEP Goals

When creating an IEP, the team should begin to evaluate and examine previous documentation to assess the student’s current level of achievement. Previous goals that have been met and have been successful, as well as those areas in which the student is struggling, should be reviewed. The areas where the student has made strong progress would indicate that the student can move on and learn new skills. Where the student is stuck or not progressing, there should be an analysis to identify where the skill breakdown occurs to address this in the following IEP.

Furthermore, the student’s learning style should be included and considered throughout. This includes whether the student is a visual learner, kinaesthetic, auditory, or reading/writing. Goals and materials should be made with this in mind to help the student learn these new skills. Moreover, how frequently a student needs breaks and what type of breaks, such as movement breaks, quiet time, etc, should be considered and included.

Finally, the student’s communication needs should be assessed and targeted in the IEP. For example, the IEP should include whether the student is vocal or requires an Alternative and Augmentative Communication (AAC) device, visual supports to help with communication, or any speech impediments with which they need extra support.

SMART Goals

For IEP goals to be effective, there are 4 dimensions that each goal should cover. That is, goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

If a goal is specific, that means it is objective, clearly explained, and concrete. A goal must be specific so that every person who reads the IEP understands the goal and how to implement it.

For a goal to be measurable, it must be defined. For example, a reading goal may contain how many words the child is expected to learn, whereas an attending goal may include how many minutes the child is expected to be on task.

Achievable goals state that the targets need to be realistic and reasonable. That is, goals should be challenging so the student is being pushed, but should also be a goal that the student should be able to master by the end of the year. The goals should not be too difficult or too easy.

For an IEP goal to be relevant, it should be specific to that student and whether or not that skill has any significance for that student’s life. For example, for a cooking-related goal, teaching a student who dislikes coffee how to prepare a cup of coffee would not be a relevant goal, as he will never use this skill outside of class. However, if they like hot chocolate, targeting how to make this would be relevant as it’s important to the student and has an application to his life.

Time-bound goals relate to there being a clear beginning and end. This could be both short-term and long-term. For example, a dressing goal that would be time-bound may specify that a student needs to change clothes within 5 minutes. A long-term goal will typically go from the beginning to the end of the school year.

Depending on the student, different areas of an IEP will receive more or less emphasis. However, an IEP must cover key areas to help develop skills and support the student across numerous areas. After an assessment, an IEP will be developed that targets communication skills, social skills, academic skills, and behavior and emotional regulation.

In the communication domain, the IEP will have goals related to social, expressive, and pragmatic communication. As mentioned, the communication modality will be considered, and there will be goals to target this specific communication type. For social skills, the domain will cover peer goals and group goals. The academic domain will cover most academic subjects, with goals tailored specifically for that child’s level. Behavior and emotional regulation domains typically cover the challenging behaviors that have been targeted for reduction and the alternatives that will be taught in their place.

Get Matched With an ABA Therapist Near You

Enter your details to receive a free, no-obligation consultation:

- Therapists Available

- Medicaid Accepted

- Quick Response programming-hold-laptop

Developing Academic Skills

Improving reading and writing abilities.

Reading and writing goals are essential goals for students with autism. Words are everywhere, and being able to read and understand words opens up opportunities for communication, artistic expression, following recipes, directions, schedules, etc. Reading and writing skills are also the foundational blocks to build more complex academic skills.

IEP assessments should identify the student’s current level and learning style. The goals should be achievable and challenging and broken down into smaller, more digestible chunks to help the student succeed and build confidence.

Enhancing Math and Problem-Solving Skills

Math and problem-solving skills are another crucial aspect of IEP goals for students with autism. Developing these skills is useful to build upon more complex academic skills and help solve real-life problems. This domain should typically cover mathematical operations, fluency, problem-solving, and reasoning.

The IEP goals should help students develop problem-solving strategies and build confidence in their mathematical abilities. The areas in which there are breakdowns in skill acquisition should be identified, and bridges should be built to help the student be successful.

Academic skills development is a vital component of IEP goals for students with autism. In addition to reading, writing, and math, academic domains also cover social sciences, technology skills, and spelling. Goals should be socially significant to students, meaning they apply to their everyday lives. In this way, the academic skills taught will help develop the student’s critical thinking skills and generalize their knowledge to different people and environments.

Communication and Social Skills Development

Developing Communication Skills

Communication deficits are one of the key characteristics of autism. As such, targeting communication is fundamental for students with autism. This is typically done by helping to develop expressive, receptive, and pragmatic language as well as vocabulary development and functional communication.

IEP goals in the communication domain should target the student’s ability to express themselves, their comprehension, and their capacity to engage in meaningful conversations. For this, the goals need to be highly individualized and specific to match the communication type of the student as well as their current level of independence.

Enhancing Social Skills and Interactions

Social skills are another area in which students with autism tend to struggle. Therefore, enhancing social skills and interactions should be incorporated into an IEP for students with autism. Teaching these abilities can positively impact all areas of their lives, such as making friends, improving family relations, and helping with acquiring and maintaining a job.

Depending on the child, useful goals include friendship skills, conflict resolution, conversation skills, perspective-taking, turn-taking, and sharing. Working on goals like these can help students develop appropriate behaviors, navigate social situations, and build relationships. These goals can be targeted in structured and naturally occurring situations to help aid with generalization.

Expressive communication is essential for a child to communicate their basic needs. Students need to be able to communicate their feelings, ideas, and thoughts as well as request what they need, such as breaks, movement, water, snacks, etc. If the student can meet their needs, they will be more open to the learning process and can acquire new skills faster.

The IEP should have goals specifically targeting expressive language skills. There are different modalities of communication, such as speech, AAC, Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), pointing, etc. The IEP goals should be specific and individualized to the student and target all the student’s communication types.

Behavior and Emotional Regulation

Managing challenging behaviors.

Managing challenging behaviors is a vital aspect of IEP goals for students with autism. When selecting which behaviors to target for reduction, the team should choose behaviors that interfere with the child’s ability to learn and integrate into a less restrictive environment.

To reduce these challenging behaviors, IEP goals should focus on teaching the students functional alternatives that they can utilize to meet their needs. Furthermore, interventions should try positive reinforcement techniques to empower and motivate students. Punishment techniques should only be implemented as a last resort and with permission from parents.

Learning about emotional regulation and self-control is essential for students with autism to build positive social relationships and thrive in an academic setting. Here, it is useful to collaborate with occupational therapists to develop strategies to address any sensory deficits or issues affecting a student’s self-regulating ability.

IEP goals should help students identify their feelings and teach them skills that they can use to regulate themselves when they feel different emotions. Collaborating with families is important here so the student can use the same coping strategies both at home and at school.

Independence and Life Skills Development

Encouraging Independence in Daily Activities

Teaching life skills that will help students live more independently and productively should be an integral part of an IEP. Skills covered in this domain could include personal hygiene, dressing, cooking, chores, purchasing skills, etc.

IEP goals should target these skills with careful consideration for increasing independence. Again, collaboration with caregivers and home teams is key here to ensure the student is learning the skills similarly and promote generalization across people and environments.

For teenagers, practicing and learning vocational skills at school can help them transition into the workforce and adulthood. Here, the student’s likes and strengths should be considered when deciding what jobs and skills to teach. Students should be involved in the selection process by suggesting their ideas, as well as giving feedback about whether or not they enjoyed a particular task.

The goals should help students to apply for and hold employment. For example, useful skills could be learning to fill out an application form, filing paperwork, transcribing information, making materials for other teachers, etc.

Collaborating with the IEP Team

Parents’ role in developing iep goals.

Parents are an integral part of the IEP development team as they can offer valuable insight into their child’s strengths and weaknesses and whether the skills the child is learning at school are being generalized to the home setting.

Collaborating with Teachers and Therapists

Collaboration between parents, teachers, and therapists is essential during the IEP creation and implementation. Teachers and therapists can bring their expertise and experience to the table, using their assessment results and their knowledge of the students in the classroom. Parents can offer invaluable advice on how the child behaves at home and can help suggest meaningful and socially significant goals. Including parents in the IEP process also increases the chances of their buy-in, which means they are more likely to work on and carry through on the goals at home.

Throughout the year, the student’s progress should be monitored to ensure they are on track toward meeting the IEP goals. If the student is not progressing, the team should examine the goal and how it’s being taught and make appropriate adjustments. For example, the goal may need to be broken down into smaller components, more prompts may be necessary, or materials may need to be modified. Teachers should also check in with parents regularly to assess whether the student is progressing at home. These check-ins can help highlight whether there is a generalization of skills or whether more parent training should occur.

Data and documentation on what is successful in teaching the student should be taken and graphed regularly. Having this data and information will help guide the next IEP, as the team will be aware of what supports are needed for the student to learn effectively.

Implementing and Evaluating IEP Goals

Individualized instruction and accommodations are crucial for the successful implementation of IEP goals. This means every IEP should be different and specific to meet the learning needs of the child. Teachers should rely on past data documentation and information from parents and home therapists to create an individualized education program to collect a full picture of the child’s needs.

Once the IEP goals are selected, teachers should also consider the student’s accommodations, such as break frequency and length, movement breaks, visual supports, communication accommodations, etc. Having these in place will help support the student’s education and learning.

Mastering IEP Goals for Autism: A Key to Success

Helping students with autism master their IEP goals is a crucial aspect of supporting them and maximizing their potential for success. This helps build their confidence and independence and sets them up for success in their educational journey by helping them master the building blocks to greater and more complex skills.

Working together, parents, educators, and therapists can create meaningful and effective IEP goals that promote the child’s growth and development. Using a collaborative process, students are more likely to show powerful change across multiple environments, including school, home, and the community.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

ABA therapy is evidence-based and has been proven to be effective at helping children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder .

Blue ABA is a family-led business providing outstanding care to children and their families.

We are hiring! BCBAs and RBTs apply here

For More Information

About | Resources | Press | Privacy

Get in Touch

Main Office: 3815 River Crossing Parkway, Suite 100 Indianapolis 46240

Phone: 800.219.4977 Fax: 512.813.5917 E-Mail: [email protected]

Copyright © 2021-2023 Blue ABA

18 Social Skills Activities for Kids with Autism and Sensory Issues

If you’re looking for social skills activities for kids with autism, as well as practical tips to help you teach social skills to a child on the autism spectrum, you’ve come to the right place!

Autism and Social Skills

While no two children with autism are the same, and the range and intensity of symptoms varies from person to person, social dysfunction tends to stand out the most when interacting with a child on the autism spectrum. Some kids find back-and-forth dialogue difficult, preferring to talk only about a topic he or she is interested in, while others prefer to avoid social interactions completely.

To an outsider, it often seems as though these children prefer to play independently, and while that may be the case for some, many kids with autism genuinely want to form friendships with their peers.

They just don’t know how to do it!

In the face of communication challenges, sensory processing sensitivities, an inability to express their own emotions and understand the emotions of others, and problems with impulse control and self-regulation, the world is an overwhelming and confusing place for people with autism, and despite their best intentions, they often fall short when it comes to reading social cues and responding appropriately.

The good news is that it IS possible to teach social skills to kids with autism, and we have 25 tips and social skills activities to help.

Teaching Social Skills for Autism: 7 Tips for Parents

Be a good role model. One of the foundations of teaching social skills for autism is to model what appropriate socialization looks like for your child, and explain what you’re doing and why. This can be uncomfortable for parents and caregivers who are introverted, but when you model consistent and positive social behavior for your child, it will be easier for her to mimic these behaviors over time. Make it a point to greet those you encounter together on a daily basis, and engage in small talk wherever possible.

Role play. Another great way to teach social skills to kids with autism is to role play. You can come up with fictional situations to act out together, or you can re-enact scenes that already happened and discuss more appropriate ways to handle such interactions in the future. Remember to practice often and to be consistent to ensure the principals and ideas you are trying to teach your child resonate with her.

Use social stories and scripts. Social stories are written descriptions of everyday situations and events told from a child’s perspective. They are aimed at providing children with something to rehearse so they feel prepared once the situation described actually takes place, and can be an excellent strategy for teaching social skills to kids with autism. Social scripts are a little more generic in that they provide kids with a pre-defined list of things to say in certain situations, and while they are certainly useful in teaching kids how to start conversations and how to respond to small talk, they should be used with caution as they won’t work in every situation and can make kids sound too scripted.

Develop a list of social rules. If your child struggles to understand some of the nuances of socialization, like the importance of saying ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye’, taking turns while talking, respecting personal space, etc., consider developing a list of ‘Social Rules’ for your child to abide by. Write them down on a white board and keep them somewhere visible so your child can refer to the list often, and if your child struggles to maintain the rules you’ve set forth, consider turning this into a reward system whereby your child earns a small treat for following a certain number of the rules you’ve set forth for her each day.

Enroll your child in social groups. Many major cities offer social groups for kids with autism, which are aimed at pairing children with similar abilities together in an effort to provide opportunities for them to practice important social skills like starting conversations and taking turns talking. This is often done through play, and while social groups can be highly beneficial, the uniqueness of autism can make it difficult to find other kids with similar social skills to your child.

Organize supervised playdates. If you’re interested in providing your child opportunities to socialize with her peers, but struggle to find kids with similar social abilities, consider hosting playdates with some of her school mates at your home and find ways to get involved so as to teach your child how to interact appropriately. Organize games and activities for the kids to enjoy during the playdate so your involvement seems natural, and find subtle ways to prompt your child. Alternatively, if the other parents are open to it, you might consider having one of your child’s therapists participate in the playdate so he/she can more appropriately teach your child what is expected of her.

Read books. There are heaps of great books filled with social learning tips and social skills activities for kids with autism, many of which are geared towards providing ideas to parents and caregivers. Here are of 6 my favorites!

- The Zones of Regulation . The Zones of Regulation is a cognitive behavior based curriculum designed to help children learn how to regulate their emotions independently by teaching them how to identify their feelings and how their behavior impacts those around them. Developed by Leah M. Kuypers, the program teaches children how to recognize when they are in different emotional states called ‘zones’, which are represented by different colors. The Zones of Regulation uses activities to equip children with the tools they need to regulate their actions and stay in one zone (or move from one zone to another), allowing them increased control and problem-solving abilities, which will in turn help them understand how to interact in social settings, and how their actions may be perceived by and impact others. If your child struggles with self-control and lacks the ability to understand her emotions as well as the feelings of others, I highly recommend the program, and this book is a great starting point.

- You Are a Social Detective . This is an introductory book to the Social Thinking curriculum, and kids love it! Through fun cartoons, kids learn to distinguish between ‘expected’ and ‘unexpected’ social behaviors, and as they work through the book with a parent, therapist, or teacher, they will learn other ‘social smarts’, which will help them understand how they should and shouldn’t behave in social settings.

- The New Social Story Book . If you’re interested in using social stories to teach your children social skills and/or need inspiration on how to create your own social stories, this book is a great place to start. With over 150 social stores to choose from, these stories will help you teach your child how to recognize and respond to social cues, and how to make and maintain friendships.

- Social Skills Handbook for Autism: Activities to Help Kids Learn Social Skills and Make Friends . With more than 50 meaningful social skills activities to choose from, this book is packed with ideas to help parents, therapists, and teachers teach social skills to kids with autism.

- How to Make & Keep Friends: Tips for Kids to Overcome 50 Common Social Challenges . This book comes highly recommended from parents with older kids on the autism spectrum who struggle to make and maintain friendships.

- The Autism Activities Handbook: Activities to Help Kids Communicate, Make Friends, and Learn Life Skills . With more than 30 games and activities to help children on the spectrum learn different developmental skills like following directions, interacting with peers, developing social skills, and improving their communication and language skills, I highly recommend this book!

Social Skills Activities for Kids with Autism

And now for the fun part! If you’re looking for social skills activities for kids with autism and other developmental delays, this collection of 18 ideas is perfect for home, school, therapy, and social group settings, and double as fabulous one-on-one activities you can enjoy with your child when you want to spend some good ‘ole quality time together.

Kids Activities that Teach Emotions

Emotions Match Up | Teachers Pay Teachers Teachers Pay Teachers offers all kinds of helpful activities and games to help kids work on specific skills, and this Uno-inspired match-up game presents thought-probing questions about emotions, situations, and strategies which not only serve as an excellent teaching tool, but also helps foster conversation skills!

Emotions Sorting Game | Mom Endeavors If your child struggles with emotional regulation, this is a great activity to explore. It’s based on the movie Inside Out , and these Inside Out figures provide so many opportunities to teach kids about anger, sadness, fear, disgust, and joy!

Zones of Regulation Twister | Unknown If your kids enjoy the classic game Twister , this is a great Zones of Regulation activity, and you can set this up so many different ways. For example, when your child puts a hand on a certain color, he must tell you about a time he was in that colored zone, and when he puts his foot on a certain color, he must tell you about a strategy he used while in that colored zone to help him get back to the green zone.

Kids Activities that Teach Self-Regulation

Self-Control Bubbles | Love, Laughter and Learning in Prep! If you want an excuse to get outside and enjoy some sunshine with your little ones, grab a couple of bottles of bubbles and give this self-control activity a try!

Musical Statues I remember this being a favorite birthday party game when I was growing up, and recently learned it’s a fabulous game to teach kids the art of self-control. All you have to do is pump some good tunes, let your child dance off some energy, and periodically stop the music and yell ‘FREEZE!’ The idea is for your child to go from dancing to standing completely still in an instant, which isn’t an easy task for kids who struggle with self-control.

Distraction This game is equal parts hilarious and educational, and can be enjoyed in the classroom or as a family. Players take turns drawing number cards and must remember the growing sequence of numbers until a player pulls a ‘distraction card’. This person must then answer a silly question before reciting the sequence of numbers in the exact order they were drawn. It’s so much fun and a great therapy toy to help kids with challenges develop their cognitive skills in a non-threatening way.

Blurt! Geared towards older kids, Blurt! is a fun game the whole family can participate in, but it’s also a great way to teach kids self-control. The premise behind the game is simple – one person reads a definition, and the person to blurt out the corresponding word first wins – and when you organize the game such that only 2 people are playing against one another at a time, it forces the rest of the family to exercise self-control as they refrain from yelling out the answer.

Kids Activities that Teach Communication Skills

Social Skills Board Games This set contains six unique board games in one box, which are focused on helping kids learn about morals, manners, empathy, friendship, and emotions. It’s a great bundle to consider and the games are perfect for family game night!

Size of the Problem Activity Pack | Teachers Pay Teachers The activities in this set help kids identify the size of their problems and the feelings they create, identify which reactions are/are not appropriate, and strategize possible solutions, making it a great way to engage in meaningful back-and-forth communication with your child while simultaneously teaching appropriate communication skills and responses.

Learning Resources Conversation Cubes With 36 conversation starters to choose from, these Conversation Cubes offer a fun way for older kids to practice starting and maintaining conversations with others. You can practice at home, or set-up conversation groups within a classroom setting, allowing children the opportunity to practice how to initiate a conversation, and how to listen when others are speaking.

All About You Thumball Whether you’re practicing social skills at home, or hosting a social group for your child, the All About You ball offers a great way to break the ice, teach kids appropriate social conversation starters, and get them talking.

Social Skills Challenge | Teachers Pay Teachers This is a fun classroom activity, but you can easily use it at home or in a therapy setting as well. The idea is to provide your child(ren) with a social challenge each day, and then have them reflect on how they felt while completing each activity. It’s an innovative way to get kids thinking about appropriate socialization throughout the day, and by offering your child a way to reflect on their feelings afterward, you will gain a greater understanding of how she perceives certain social settings and interactions.

Kids Activities that Teach Problem Solving Skills

Describing and Solving Problems | Teachers Pay Teachers This is a great activity for kids who struggle to distinguish between big and small problems as well as appropriate reactions.

Scrabble Scrabble is a great game for kids who struggle with planning and organization. As the game progresses, they must strategize and anticipate how they can build their own words off of those already played by others. This is also a great game for kids who struggle with spelling and/or vocabulary, and it gets them talking!

Memory Also known as ‘Concentration’, there are many versions of the classic game Memory available for purchase to help develop a child’s focus and concentration skills. The idea is pretty easy and can be enjoyed with 2 or more players. Simply lie all of the tiles from the game facing downwards, and then take turns turning over 2 tiles at a time until you find a match. Children naturally build their working memory as they try to remember where specific cards are. We love our Despicable Me Memory Game , and I highly recommend Melissa & Doug’s Flip to Win Travel Memory Game as it can be played independently (or as a family) for on-the-go fun.

Problems in a Jar Mosswood Connections is one of my favorite resources for ideas to help kids with developmental delays like autism and sensory processing disorder, and I recently found this Problems in a Jar activity on their site. It’s designed to help kids with executive function disorder learn how to define a problem, generate possible solutions, evaluate and select the best solution, and then implement the solution independently. It’s a great social skills activity to work through with your child at home.

Team Sports Another great way to help a child develop her social skills is to sign her up for team sports she enjoys, like soccer or basketball. Organized activities such as these require kids to practice a whole range of social and problem-solving skills, like following directions, planning, strategizing, and even controlling their emotions in the event that they lose a game.

Swish I’m new to this game, but so far I really like it. To play, you lay out your cards and then try to find as many matches as possible. The cards are transparent and have different colored hoops on them in different positions. Players must look for matches (aka ‘swishes’), and the player to find the most wins. Swishes are created when a player can line up 2 cards such that the hoops are identical when they are stacked one on top of another. Cards can be rotated in order to make a swish, requiring players to use a variety of executive functions. In addition to exercising their visual-spatial abilities, they must focus and concentrate, and work quickly to beat their opponent, making it a great interactive game for kids who struggle with socialization.

I hope this collection of teaching tips and social skills activities for kids with autism proves helpful to you. Remember to be a good role model, to practice patience and consistency, and to keep things FUN!

This post contains affiliate links.

If you liked this collection of teaching tips and social skills activities for kids with autism, please share this post on Pinterest!

And if you’re looking for more autism-related tips and tricks, please follow our Autism board where we share all kinds of helpful ideas we find each day!

Share this post:

16 Best Portable Airplane Snacks for Kids

13 Protective Hairstyles for Sleeping for All Hair Lengths

How to Make Egg Rolls (+15 Easy Recipes!)

Common Problem Behaviors in Children with Autism and How to Handle Them

by haleydoyle7 | Jun 2, 2021 | Autism Treatment | 0 comments

- Aggression toward others

- Elopement (wandering off)

- Destruction

Problem behaviors in children with autism can make everyday life more stressful and overwhelming. Not just for you, but them as well. That’s because challenging behaviors often stem from their desire to communicate what they need or want. But they often don’t know how to do that effectively.

Step One: Identify Your Child’s Needs

Helping your child overcome problem behaviors may seem daunting, especially if they display several challenging behaviors you’d like to change. First, make a list of these behaviors, from the most disruptive or dangerous to the least common. Tackling these behaviors one at a time can help the process run more smoothly. Many times, when you start addressing one behavior, the occurrence of other problem behaviors may also diminish.

Step Two: Determine Triggers

Identifying what triggers your child’s problem behaviors can take some time since several variables are involved. Keep a journal of the behaviors you identified in step one, spanning over a couple of weeks. Since changes in routine often trigger challenging behaviors, it’s best to include both weekdays and weekends when schedules change.

It’s crucial to keep in mind you may not understand why your child gets triggered by certain things. Try your best to remain nonjudgmental. Instead, look at it as a scientist would observe a subject. Yes, this can be challenging, especially when your child’s problematic autism behaviors disrupt daily living. But remember, by observing your child’s behaviors, you’re learning how you can help them reach their full potential.

Common triggers for children with autism can be broken down into two categories:

- External environment

- Internal environment

External Environment Triggers

Understanding problem behavior triggers in your child’s external environment, meaning outside of themselves, is critical. When you identify these triggers, you can anticipate things that may cause your child to act out and make any necessary changes to avoid issues going forward.

- Social: Social situations can be difficult for children with autism, causing them anxiety. Whether in a controlled environment where you are with your child as they attempt to interact with another child or in large gatherings like assemblies, play dates with lots of children, picnics, or recess time at school.

Any kind of unplanned or unannounced social event can trigger your child with autism to display problem behaviors.

- Sensory overload: One common trigger for children with autism is an overwhelming amount of sensory information. Sensory overload can occur at any time and in any space. Your child could be triggered by loud noises, crowds, smells, food, dental or medical issues, bathing, clothing, or even ambient sounds like your refrigerator humming.

- Disinterest: Really, this means boredom. Suppose your child is uninterested in something, such as listening to a teacher talk about animals when they are more interested in construction equipment. In that case, they are more likely to display challenging behaviors.

- Unrealistic expectations: Sometimes, parents, caregivers, peers, and teachers can put too much pressure on a child with autism to do certain things they “think” they should be able to do. For example, some children with autism have difficulty dressing themselves. So when they are expected to perform this task when they don’t have the skills to do so, they may get frustrated, leading to problem behavior.

It’s essential to understand your child’s needs before putting too much pressure on them to do things they aren’t ready to do on their own.

- Communication issues: Problem behaviors in children with autism can stem from an inability to communicate their wants and needs to you, their teacher, or their peers. Whether your child is verbal or nonverbal, they could have issues communicating effectively. This leads to frustration and challenging behavior.

Internal Environment Triggers

These problem behavior triggers can be a little more challenging to pinpoint, but they are crucial to understanding how to help your child. And because communication skills aren’t always strong in children with autism, determining these triggers may take a little more work on your part.

- Food allergies or sensitivities: Keep a close eye on how your child responds to food. Keep a diary of what they are eating and any possible physical triggers such as diarrhea or flushed cheeks. If a particular food is bothering your child with autism, they may not communicate it properly. Instead, they may display challenging behaviors such as flapping their arms are exhibiting repetitive behaviors. If you notice any negative responses, try eliminating the food to see if it helps.

- Physical Pain: If your child with autism has a cut, abscess, bruise, cavity, acid reflux, or a sprain, they may not be able to communicate that to you. Pay attention to any localized behaviors, as they may indicate to you where your child could be experiencing pain.

- Seizures: Sometimes, seizures can be difficult to spot. You may think your child is just exhibiting typical challenging behaviors. But if you see any unmotivated, odd behaviors that seem out of the norm, it may be time to make an appointment with your child’s doctor.

- Coordination issues: If your child has trouble with their motor skills or is not very coordinated when they walk or play, they can become anxious and frustrated, leading to problem behaviors.

- Fatigue, thirst, and hunger: This is an easier internal trigger since it is the same for any child. If they are tired, hungry, or thirsty, they are more likely to display challenging behavior.

- Emotional concerns: Children pick up on emotions easily. If you are stressed, struggling with a difficult life or health situation, or experiencing anxiety and fear, your child will notice. And because they don’t have any control over your emotions, they may begin to display troubling behavior as a coping mechanism.

Step Three: Enact an Intervention Plan

Once you’ve identified your child’s triggers, it’s time to act on ensuring you minimize them. Before you begin, remind yourself, patience is key— patience with your child with autism and yourself. Sometimes avoiding triggers or teaching your child new coping mechanisms involves trial and error. But if you stick with it, you’ll set your child up for success.

Here are some ideas on helping your child overcome problem behaviors:

Sensory breaks help balance your child’s vestibular sense, which is the sense that controls balance and the sense of their body in a given space. Often when children with autism get overstimulated, they may resort to repetitive behavior because their vestibular sense is off-balance. To bring it more in balance, consider any of the following sensory break practices:

- Wearing a weighted vest or blanket

- Rubbing something with a desirable texture

- Listening to music

- Spinning or rocking

- Going for a walk or run

- Chewing something crunchy

How often your child needs sensory breaks varies. They may need one as often as every two hours. But if they are highly agitated or stressed on a given day, they may need more.

- Create a visual routine schedule: Children, especially children with autism, thrive on routine. Put together a routine on posterboard with visual cues, so your child knows what to expect each day. You could show a picture of them brushing their teeth, followed by breakfast with mom, dad, and siblings, then playtime, learning time, break time, snack time, etc.

- Prepare your child for changes in routine: This can be as simple as giving your child a 10-minute warning before going to do something different or leave to go somewhere. You could use pictures, a clock, or a timer. You could also use social stories.

- Introduce your child to overstimulating environments slowly: Overstimulation is a common trigger for many children with autism. You don’t want to avoid everything that may stimulate your child. Instead, consider slowly introducing an environment that may be difficult for them. For example, if your child with autism exhibits problem behaviors when you are out grocery shopping, try introducing the activity gradually. You could go to the store for five minutes on the first trip and then work your way up to a whole shopping trip.

- Set ground rules: Remember, when you are trying to change your child’s problem behaviors, they are learning new skills, and it can be challenging for them. It’s important to set ground rules slowly. Start small by showing them pictures of the rules, such as, “If you finish your breakfast, you get 15 minutes on the iPad,” with corresponding images. Or, “If you behave in the store, I’ll get you a treat.

- Use calming devices: There are several fidget tools, calming blankets, and sensory calming devices for children with autism. Keep these items in your car, purse, and backpack to make sure you have a way to calm down if they become agitated.

- Don’t give in to problem behaviors: Yes, it can be difficult not to give your child what they want when they exhibit problem behaviors, especially in public. Remind them of the ground rules. It’s okay to reinforce positive behaviors, but you make it more challenging to overcome them if you give into problem behaviors.

Ensure Your Child’s Success with ABA Therapy

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is one of the most studied and proven treatment approaches to help children with autism break problem behaviors. If you’re overwhelmed at the thought of trying to do this alone, arming yourself with the tools and skills to help your child succeed by getting them into an ABA treatment program is your best bet.

When you enroll your child in an ABA treatment plan at the Autism Therapy Group (ATG), you become a part of our family. At ATG, your child’s ABA therapy team is made up of an experienced group of Board Certified Behavior Analysts, Registered Behavior Technicians (RBT), and Client Services Managers with extensive training in helping children with autism achieve goals in:

- Communication

- Social skills

Here at The Autism Therapy group, all you need to do is contact us, and we’ll walk you through the next steps. After your child’s initial evaluation, we’ll work with you to develop the perfect treatment plan, whether it takes place in your home or our brand new autism center in Lombard, IL. We’ve partnered with hundreds of parents and caregivers just like you to help their children breakthrough problem behaviors and achieve their full potential.

Discover more from The Autism Therapy Group - ABA Therapy

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Embedded Change and Teaching Problem Solving

If you want your students to grow up to be functionally independent adults it is essential and critical to make life harder on them now. We don’t want to coddle them. We don’t want them to rely on us. We want them to do it for themselves. I tell teachers and paraprofessionals all the time – your job is to lose your job. We want our kids to not need us.

A great way you can start to do this is by sabotaging your students. Again – it sounds mean but in the long run we’d rather have twenty year olds who can advocate for themselves versus twenty year olds who need an adult to follow them around. It’s time to get tough. If you want your students to develop problem solving skills – they need to run into problems.

On a daily basis, we need to create situations in the classroom where students run into a problem.

- Using TAH Curriculum for Homeschooling from a Homeschooling Parent - September 10, 2022

- Using The Autism Helper Curriculum for Homeschool - August 8, 2022

- Literacy Subject Overview in The Autism Helper Curriculum - August 2, 2022

I love your ideas and am wondering if you can please add me to your newsletter and subscription.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

10 Tips for Collaboration

In the world of consulting, developing an effective and conceptually systematic behavior plan is only half the battle. Having staff or parents accurately and consistently implement the plan will determine program success. Time, resources, and staff participation are big obstacles facing effective consultations. In this session, learn 10 actionable strategies for developing collaborative consultative relationships that lead to better follow through on behavioral programs. These strategies are not only real world based but also aligned to the BACB’s ethical guidelines. Each tip is supported by a specific guideline.

3 Biggest Mistakes in Behavior Plans & How to Fix Them

Positive behavior change involves focusing on the WHY behind a behavior and teaching the missing skills. The results of real behavior change are long-lasting, generalize to new settings, and socially significant for the individual. However, when moving towards this goal there can be significant challenges. Several common missteps in creating behavior plans can lead us astray from our goal of positive behavior change. In this session, learn the three most common mistakes that impact the success of a behavior plan. These mistakes include inconsistency with strategies, not including a replacement behavior, and lack of consistency with staff. Then explore strategies to combat these missteps and ensure that your behavior plan is on track for success.

3 Reasons Staff Training Can Make or Break the Success of Your Classroom

In the role of a special education teacher you are also placed with the responsibility of being a manager to your team. That responsibility can be challenging and overwhelming. Often teachers have very little training on this. In this session, learn why staff training is so essential to the success of your classroom. We explore how this gives your students more instructional time, behavior plans are implemented more consistently, and more reliable prompt fading leads to more student independence. Participants will learn actionable strategies to create time for staff training and then utilize that time efficiently to build a team approach.

Adapted Books

Learn how to target a wide range of literacy goals for early childhood students using interactive and hands-on adapted books. An adapted book is any book that has been modified in some way that makes it more accessible. Adding moveable pieces, simplified text, and visually based comprehension activities to your existing favorite books can help increase student engagement. In this session, we will explore ways to create your own adapted books that build both foundational language skills and more advanced literacy concepts. Adapted Books can be used to build basic literacy and language skills such as matching, sequencing, sorting, following directions, categorizing, using prepositions, and more. Take it the next level by building advanced skills such as making inferences, using context clues, and identifying emotions. Learn how to utilize these books in small group instruction efficiently and effectively!

Adapting Academics

Working in the special education field, we are often tasked with the daunting job of creating a curriculum for our students. We don’t have a roadmap to follow. Nobody hands you the perfect text book for each of your students. Many individuals with autism or special needs have skills that are scattered, varied, and difficult to assess. As educators and parents, we have to the heavy lifting to determine what our students know and what they need to learn next.

In this session, learn how to create a functional and appropriate curriculum guide for a wide range of types of learners. We will discuss how to incorporate assessments, state standards, and functional needs to develop appropraite goals. Then we will explore ways to teach and build both academic and functional skills. This presentation will guide you through the planning stages, IEP goal writing, and finish with the creation of materials.

Behavior Contingency Maps

Ca and classroom setup.

Learn how to structure an effective classroom and utilize The Autism Helper Curriculum Access in this dynamic and jam-packed session! For Curriculum Access users, this workshop will walk teachers through how to set up and use the curriculum. We will cover placement assessments and determining levels, lesson planning, running instructional lessons, making data-based decisions, and troubleshooting challenging areas. This framework works best when incorporated into a highly structured and routine-based classroom that uses small-group instruction. Teachers will learn how to effectively set up this structure to prevent problem behaviors and allow for maximum instructional time. We will discuss independent work, staff training, and schedules as well!

Can’t Do or Won’t Do

The goal for ALL students is to be learning, engaged, and independent. When are students are struggling to achieve this goal, we need to get to the root of the problem. Begin this process by identifying each learning and behavioral challenge as a Can’t Do or Won’t Do. Is the work or work process beyond your child’s skill level or is the motivation to complete the task not there? Explore learning obstacles by improving executive functioning skills. Learn how to identify executive functioning strengths and weaknesses. Match student strengths with activities they can excel at while simultaneously directly teaching skill deficits. For students who demonstrate the skills need but struggle with the motivation, add a proactive element to your behavior management system by implementing positive reinforcement to increase positive behaviors within your class. Learn best practices related to reinforcement and why it may not be working right now in your classroom. This session is jam packed with ready to use strategies for general education and special education classrooms.

Classroom Environment As a Tool

The way the learning environment is set up is one of the most valuable tools you have. This can drastically impact the success of academic instruction and lead to decreases in negative behavior and anxiety as well as increases in student independence. In this session, learn how to take a proactive approach and build your toolbox of strategies. These antecedent interventions will help you create an optimal learning environment based on student needs. We will also explore how to support teams in utilizing these strategies with efficacy.

Data Driven Classroom

This workshop breaks down the data collection process for special education classrooms. Attendees will learn how to streamline the data collection process and collect data that will truly informs instruction. Learn how to analyze and use data to drive your instruction, IEP goals, and behavior plans.

The key to successful data collection is to make it easy and doable! We will discuss ways to take data that are efficient, time saving, and useful for both academic and behavior data. In this session, we will review using rubrics, rate of responding, frequency count, and tracking prompt levels to take data on both functional and academies skills. Next learn how to take frequency, duration, and rubric data for problem behaviors to develop your behavior plans. Organization is the major component to a successful data system. Learn how to create specific and individualized data sheets in a fast and simple way and explore a range methods of organizing your data so you can access it readily. Staff training is also essential. Learn how to work with your staff so data is taken consistently across all areas of your classroom!

Executive Functions

This workshop teaches the importance of building executive functioning skills and how to build those skills within a wide range of learners. Attendees will learn the entire process from assessment and goal identification to instructional strategies and data collection. Walk away with a toolbox of strategies to teach essential skills such as flexibility, emotional control, sustained attention, and so much more!

Executive Functions are the skills needed to accomplish goal directed behavior and are critical for every day success. The skills of planning, organization, shifting and sustaining attention, impulse control, and more are key to everything from making friends to having a job to completing a math test. In this session, learn how to identify the skill deficits that your students are struggling with under the area of executive functioning skills. Learn how to approach teaching and developing these skills with the same rigor and systematic planning that we give to other areas of need. Identify ways to setup an environment that promotes independence and problem solving. Finally, learn how to track progress and fade assistance.

Fluency is accuracy plus speed and is a must-have when it comes to making the skills we teach functional in the real world. Learn how to implement fluency instruction in your classroom with this interactive workshop. This presentation covers instructional strategies for a wide range of learners including both functional and academic skills. Attendees will walk away with actionable ideas to implement fluency instruction in their classroom!

Functional Literacy

Literacy is a key component to being a functionally independent adult. We live in a text rich world and our students need to know how to navigate through it successfully. As a teacher it’s often a struggle to balance academic and functional instruction. In this session, learn how to make your literacy curriculum real world applicable and engaging for your students!

This session will examine literacy instruction for all types of students. We will examine instructional planning, activity ideas, and specific interventions. Many struggling learners benefit from structured tasks, the use of visuals, multiple exemplars, discrimination training, and routine based instruction. Learn how you can incorporate these strategies into your functional literacy instruction.

Let’s Play

In this full day workshop, we will explore methods to increase communication, social skills, literacy, and independence through play based instruction. This session is geared for early childhood educators and clinicians. In this workshop, we break down the critical elements of play and why play is essential for building foundational skills. This session is focused on action strategies. Learn how to utilize easy to use informal assessments, identify goals, plan play based instruction, facilitate learning during play, and take efficient data. Attendees will walk away with a toolbox of resources, ideas, and activities for increasing a wide range of skills.

Classroom Schedules

Schedules are one of the most essential components to any effective classroom! Schedules let us know when transitions will occur, the order of activities, and alerts us to changes. Children with autism, receptive language challenges, anxiety, and a history of trauma, schedules are even more important. Effective use of schedules can increase functional independence and decrease negative behaviors. However, there are some common pitfalls we fall into when it comes to appropriate schedule use. Learn my 10 dos and don’ts for classroom schedules and make the most out of this must-have strategy!

Literacy Mindset

In this session, learn the 3 keys to teaching reading to struggling learners and students with special needs. Embracing the big picture goal, organization, and a comprehensive approach are essential to efficiently and effectively building reading skills for a range of struggling learners. Participants will walk away with actionable strategies for planning and creating opportunities for literacy instruction.

Positive Behavior Change

This workshop will breaks down the Functional Behavior Plan process and teaches how to create a function based behavior intervention plan. Attendees will learn solutions to foster increases in positive, communicative behaviors and decreases in problem behaviors. This session will begin by exploring how to apply these strategies to everyday situations in an applicable and proactive way. This approach will focus on the changing outcomes of behaviors by looking at the entire context and approaching behavior change from a function based perspective. The key is not only teaching communication, but teaching the right type of communication in order to produce long lasting behavior change. However, we all know – there are those times when things do not go as planned. Learn how to tackle those high-stress situations where no option seems like the right one and all bets are off. This workshop highlights ready to use interventions and real-life scenarios. The concepts can be applied to a wide range of environments

Practical Behavior Approach

The Practical Behavior Approach is a comprehensive workshop designed to help attendees successfully reduce problem behaviors and improve cooperation, independence, and engagement of children of all ages. Learn how to prevent problem behaviors and respond effectively when negative behaviors occur while building essential positive skills. Discover how a child’s diagnosis, history of trauma, and sensory needs impact behavior and the strategies we use. The strategies in this session can apply to students of all ages with and without a disability.

Preschool Vocabulary

In this full day workshop, we will explore methods to increase vocabulary, literacy skills, independence, and communication skills in your preschool students! The day begins with an in-depth look at the importance of building vocabulary for all preschoolers. Increased vocabulary will lead to more advanced reading skills in early elementary and overall school achievement. In this session, we will review the importance of building vocabulary and ways to identify vocabulary deficits. We will explore a range specific strategies for increasing word knowledge and use at a variety of levels for delayed learners. We will explore how to increase language through the use of Higher Order Thinking Questions, play based learning, and classroom based read aloud.

Next we will examine how appropriate and purposeful use of visuals helps build executive functioning skills with our younger learners. Many students with special needs struggle with receptive language. This delay in language development can cause issues with many executive functioning skills. In this session, learn how to utilize visuals to improve organization, planning, following directions, problem solving, and cognitive flexibility with preschool students. We will explore specific strategies and examples of how to create visuals, teach appropriate use, and utilize on a daily basis.

Reinforcement, Bribery, and Negotiation

A key component to all behavior management strategies is the effective use of reinforcement. In this session, participants will learn how to correctly utilize reinforcement. We breakdown how making simple changes to the way you are approaching challenging behaviors can make a huge impact in teaching positive, prosocial, communicative behaviors. Participants will walk away with a clear understanding of the difference between reinforcement and bribery as well as the knowledge of how to ensure their behavior plans are set up correctly.

Roadmap to Reading

The Roadmap to Reading gives an overview of how to provide effective and individualized reading instruction to struggling or reluctant readers. This workshops covers assessment, planning and setup, implementation, data, and staff training. The Roadmap to Reading is based on the Science of Reading’s foundational 5 components of reading. These components are taught through the 3-Part Framework of Direct Instruction, Fluency Instruction, and Guided Reading Groups. This workshop reviews how to schedule, setup, and run each center. We go in-depth into best practices and evidence based strategies for this multi-tiered approach.

Schedules and Task Organization

For your classroom to run smoothly, the use of schedules and visuals are a must. However the setup can be overwhelming and maintaining these systems can be very time consuming. Learn the most efficient and time saving ways to use visual schedules and how to incorporate visuals throughout your classroom so they are there when you need them! These interventions will help prevent behavior problems, ease student anxiety, and allow maximum communication opportunities!

In this session we will also focus on creating materials and resources that are appropriate for your students to meet their IEP goals. We will discuss implementing appropriate and useful independent work systems that give students the opportunity to generalize and maintain previously learned skills.

Seven Steps for Setting Up Stellar Autism Room

The optimal setup of the classroom environment is essential to increase engagement and cooperation as well as decrease negative behaviors. In this session learn how to organize, setup, and structure your classroom effectively. Start out with purposeful planning to lead to a structured and routine based environment. Attendees will learn how to create staff and student schedules, setup and utilize behavior and academic visuals, create data systems, setup independent work, and begin curriculum planning. Staff training is integrated into each section in order to get the whole team on board!

Small Group Instrucition

Small Group Instruction is essential for providing individualized instruction within a classroom of learners with diverse needs. In this session, learn the evidence based strategies on how to provide small group instruction in an effective, efficient, and functional way. This session provides an overview on considerations for grouping students, how to schedule groups, and what back end organization is vital to keep groups running smoothly. Then, attendees will learn the specific steps to utilize while running groups. These antecedent based interventions will help prevent problem behavior during the work session, allow for consistent data collection, and maximize learning opportunities.

Sensory Processing by Katie McKenna, MS, OTR/L

Sensory processing impacts everyone and is an essential foundation for learning. In this session, participants will learn about the eight sensory systems and why they are important. Participants will learn how to identify different ways individuals may respond to sensory input and how that impacts behavior and participation in daily activities. Finally, specific sensory strategies and tools that can be used to support students of all ages and sensory profiles will be explored.

Movement and Learning by Katie McKenna, MS, OTR/L