We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Cases in pediatric occupational therapy : assessment and intervention

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

103 Previews

5 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station24.cebu on July 12, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Copyright © 2024 OccupationalTherapy.com - All Rights Reserved

Pediatric Case Study: Child with Oculomotor and Perceptual Challenges

Nicole quint, dr.ot, otr/l.

- Early Intervention and School-Based

- Neurological and Physical Disabilities

To earn CEUs for this article, become a member.

unlimit ed ceu access | $129/year

Case introduction.

Thank you so much for having me. I want to introduce you to our case.

- Patrick: 7 y.o. male in 2nd grade that has difficulties with reading, completing homework, and the following instruction during school occupations. He does not finish copying things from the board and tends to have difficulty with writing, coloring, and ball sports. He uses his finger to read, loses his place, and often complains he can’t find things in his books. He is slow with dressing routines, buttons and fasteners are a “nightmare”, and cleaning his room is tough.

- He lives with his mother and father and two siblings. He is a shy child who loves dinosaurs, football, and Avengers. He says he wants to be a firefighter when he grows up, like his father.

- Patrick was a normal delivery without complications. Mom reports he was a fussy baby with colic. She also indicates that he was slow with some developmental motor milestones, particularly balance-related and object manipulation. She said he has always had difficulty following directions and struggles with ADLs. She calls him “clumsy”.

- Patrick also has a history of ear infections and adenoid removal. He is on his second round of ear tubes.

Today, I am doing a case study format. I want to give you a conceptual way to think about how to intervene with a child who has visual challenges that are affecting school performance, ADL performance, or play performance. Patrick is a seven-year-old male in second grade. He has difficulties with reading, completing his homework, and following instructions during his school occupation. He does not finish copying things from the board and tends to have difficulty with writing, coloring, and ball sports. He uses his finger to read, loses his place, and often complains that he cannot find things in his book. He is slow with dressing routines, and buttons and fasteners are a nightmare. He also has a tough time cleaning his room. He lives with his mother, father, and two siblings. He is a shy child who loves dinosaurs, football, and Avengers and says he wants to be a firefighter when he grows up just like his dad. Patrick was a normal delivery without complications, but mom reports he was a fussy baby with colic. She also indicates that he was slow with some developmental milestones related to motor, particularly balance-related ones, and object manipulation. She said that he has always had difficulty following directions and struggles with his ADLs. She calls him clumsy. Patrick has a history of ear infections and adenoid removal, and he is on the second round of ear tubes. This scenario might sound familiar to many of you. This is typical of a lot of the kids that I see. These are "clumsy kids" who have some difficulty in school, and it can often be misconstrued as behavioral. And, if you know Patrick, he is a really sweet kid and he is not behavioral at all.

- Extract, organize info from environment

- AKA: oculomotor skills, visual motor skills

- Interpretation of what is seen

- AKA: visual perceptual skills, visual cognitive skills

I want to start out with defining vision. It is the total process of receiving information and then processing it cognitively. It a very complicated process. How we receive information is related to sensory functions. We have to extract information from the environment. For example, in order for you to take a picture, you have to move your phone camera to the right spot. With a selfie, you might realize that you are cutting off people's heads. You have to angle it the right way to get everyone in the picture. That is an example of reception. You have to make sure that you can actually receive that information. We also refer to this as oculomotor skills or visual-motor skills. This is especially true with vision. Cognition, on the other hand, is the mental functions involved with vision. This is interpreting what is seen and that becomes much more subjective. We could call these visual perceptual skills or visual cognitive skills. Back to our picture metaphor, we look at the picture on our phone in order to process it. These are two different things, but they are very much dependent on each other. Part of the challenge I think in our profession when trying to assess someone is that they use a lot of things synonymously.

- Anatomic, physiologic

- Oculomotor, vestibulo-ocular control

- Visual perceptual skills

- Visual-motor integration

- THEN…Integrate the above functions in occupations

When we think about visual function, this is talking about visual acuity, visual fields, contrast sensitivity, etc. These are the basic functions of vision. However, you can also talk about "functional vision." Functional vision is how we use it. This focuses on ocular motor skills and how we use the two eyes together. Not only do we have to move each eye, but we also need to be able to move them together. On top of that, we have to be able to accommodate or adjust the eyes for near and far stimuli. Accommodation is sort of separate from traditional oculomotor skills because accommodation requires the integration of your lens and your ciliary muscle. Thus, when I am talking about oculomotor skills, I am not talking about accommodation. For me, the only way to really make a change in accommodation is vision therapy. When I have kids that have accommodation issues, I send them straight to vision therapy because the ciliary muscle is smooth muscle, and it is much more challenging to affect change in that. The oculomotor skills that I am talking about are things like convergence, divergence, saccades, tracking, and smooth pursuits.

What are the five functions of a mature visual system? It starts with basic anatomy and physiology. Then, we have to have oculomotor and vestibulo-ocular control. Can I move both my head and my eyes to collect that data? Sometimes the eyes move with the head, and sometimes the eyes move by themselves and do more subtle movements. Some of our kids might struggle with that operation and need to use their whole body to move with their eyes because they have difficulty with that dissociation. Next, we need to effectively interpret visual information. This is where we start to move into the cognitive piece or visual perceptual skills. We then respond to visual cues by moving our limbs for visual-motor integration. Finally, all of this is integrated into occupations. There is a hierarchy of development. Visual-motor integration is extremely complex and a lot of times our kids are missing some of these lower-level functions.

Visual Development

Here is a great link on visual development to review on your own. It is a really cool video.

Skeffington's Model

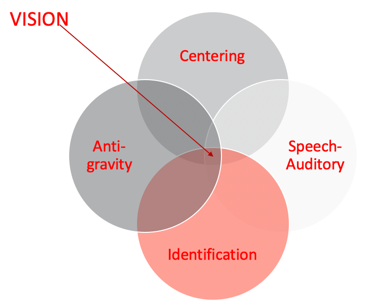

I also want to introduce to you Skeffington's model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Skeffington's model.

I do not know how many of you are familiar with Skeffington's Model. When I started working at the university, I did program development over at the middle school. My background is in brain injury. Now I work with kids who have similar issues with visual abilities and function as well as some struggles with attention in school. I have always worked with optometrists and have had an interest in vision. Optometrists introduced me to Skeffington's model, and it helped me to understand why some of the things that I had been taught and was using with my clients was not working.

- Internal balance

- Attention and orientation

- Directing body, head, eyes toward an area in space

- Gathering meaning from areas of selected attention in external space

- Relationships between details (discrimination and differentiation)

- Analysis and communication of what is seen

Among these four circles, not one is more important than the other. They all need to be balanced. First is the antigravity system or the vestibular system. You cannot think about vision without thinking about the vestibular system. We need an internal balance for postural control. And, postural control is really essential to attending to our environment. There is also a huge relationship between the vestibular system and eye movements. The vestibular ocular reflex helps the body moves to right itself.

Centering is the idea of using attention and orientation to direct your body, head, and eyes towards something in space so you can receive information. Do I have the control to orient to something, attend to it, and dissociate as I need? There has to be underlying proprioceptive function, as well as strength, to be able to do something. The strength either needs to be internal or via external supports.

Identification was one of the pieces I was missing when I was doing a lot of the visual work in the past. Identification is gathering meaning from whatever you are attending to in space and starting to appreciate the relationships between the details. This becomes really important when processing information. These visual perceptual skills help to discriminate and differentiate between things. We are not just talking about being able to label something but label it in a way where you can tell the differences and the little nuances between things that lead to higher-level thinking and awareness.

The speech and auditory area is the ability to analyze and communicate what I am seeing. This is more of a cognitive language piece. This requires the parietal lobe functioning to bring in spatial relation or position in space. I really cannot do that functionally if I do not know that I have two sides of my body or that the right and left sides can do two different things at the same time or together. Can I cross the midline? These things inform my position in space and spatial relations. If I do not understand right versus left on myself or with a person sitting across from me who is giving me directions, I have a problem. I cannot really discriminate and differentiate how to get there from my own perspective, much less yours. This starts to make sense why this is extremely important for visual processing.

Skeffington's model tells us that we see with our whole body.

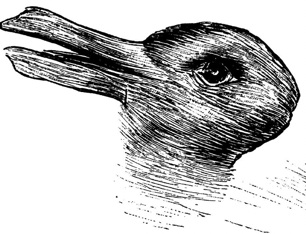

Figure 2. Optical illusion.

Figure 2 is an example of an optical illusion. Some of you might see one animal, while some of you might see another. I will give you a second to see if you can figure it out. Some of you might see both rather quickly, while others only see the one animal. some of you might struggle to see both the rabbit and the duck. Identification informs our visual perceptual skills to be somewhat subjective.

Second Grade Occupations

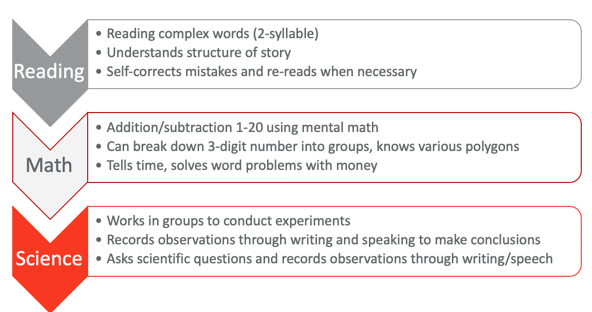

Our friend Patrick is in second grade. What is expected of a second-grader? Figure 3 is an overview.

Figure 3. Overview of 2nd-grade occupations.

These are the universal standards for second grade. They should be able to read complex words which means two-syllable words, understand the structure of a story, self-correct mistakes, and reread when necessary. Those are pretty high-level reading skills. In math, they should be able to add and subtract one through 20 using mental math. I know some adults that struggle with that. They can break down three-digit numbers into groups into ones, tens, or hundreds. They also know various polygons, which would then indicate that they have some awareness of visual discrimination and form constancy starting to develop. They can tell time with an analog clock. You can put an asterisk next to that just from societal changes with technology. They still should be able to in theory to read a clock. They should be able to solve word problems with money, start to manipulate money and coins with some basic adding, and things like that. From a science perspective, they should be able to work in groups to conduct simple experiments. They should also be able to record their observations through writing and speaking to make conclusions about what they have observed. They should also be able to ask scientific questions and record observations throughout the process, not just at the end. What is kind of interesting here about the science piece is that this is universal. This scientific inquiry could be used for other topics as well.

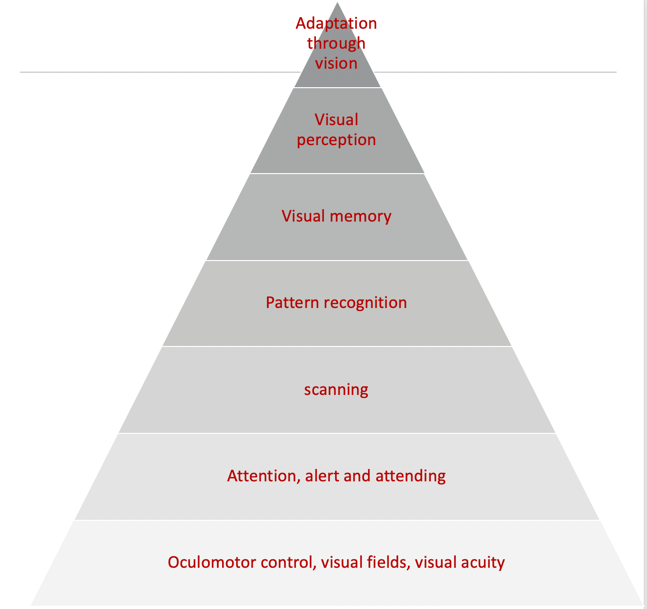

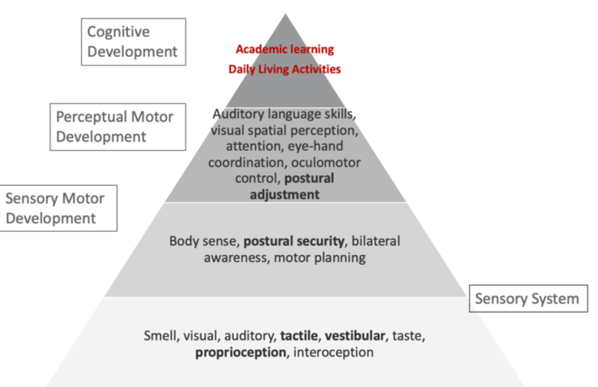

From a visual development standpoint, I cannot emphasize enough how important this hierarchy is in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Visual hierarchy.

I am going to go through it rather quickly, but I want to point out the base of it all is oculomotor control. Once the oculomotor control is there, then there is visual attention as well as vigilance or a persistence toward it. If I am really looking at something to figure it out, I have to have some persistence. Once I can attend to something, the next levels are scanning and pattern recognition. Visual memory starts to kick in once patterns are recognized. With visual memories, this becomes functional visual perception. These are perceptual skills like visual closure, discrimination, spatial relations, position in space, figure-ground, and topographical orientation. These are all higher-level visual perceptual skills that we all test all the time. Once you get through all these levels, the final area is adaptation through vision.

I always use this analogy because in Florida we have hurricanes. One of the big things down here is to get hurricane windows. Hurricane windows are great because they can withstand the impact of debris flying around during a hurricane. So, if you have a strong foundation and hurricane windows, you are kind of safe from the storm or even a tornado. However, if you have a mobile home or a tiny house, even if you add hurricane windows, the whole house will blow away during the storm without a proper foundation. I think about this with our kids as well. Many of our tools are related to visual perception. Back in the day, I would start treatment with something like mazes for visual perception or handwriting for visual-motor integration without going back and appreciating that the child was missing a foundational element. We want to make sure that they have those foundational pieces.

Case Assessment Results

- Assessments: M-FUN, DTVP-3, Beery VMI, oculomotor screening,

- School reports: Below age range in reading, above age range in math, handwriting difficulties, sits in front due to difficulty following directions, no significant behavior concerns but slow with work and often doesn’t complete assignments

- Dislikes PE, but enjoys music, art, and science

For Patrick, I used the M-FUN (Miller Function and Participation Scales), the DTVP-3 (Developmental Test of Visual Perception), the Beery VMI (Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration), and oculomotor screening. I also completed the SFA, which is the School Function Assessment. I used these because I wanted to get some information about vestibular functioning. I also wanted to a sensory profile and take a look at his motor and visual skills as well as non-motor and visual skills (DTVP-3). Oculomotor testing is also important. I often just do tracking kinds of things. I love the King-Devick Test for saccades. There is also the Developmental Eye Movement Test, the DEM, which is also very helpful. I do not know what you have access to, but you can do oculomotor testing just through the basic screenings that you do.

From his school reports, I saw that he was below the age range in reading, which we kind of suspected anyway, but he was above age range in math. He had some handwriting difficulties according to the teacher. She felt that he was slow, and it took him a long time and a lot of effort. She had him sitting in the front because he had such a hard time following directions. He was always kind of behind. His teacher did not feel that he had behavior concerns, but again he was slow with his work and he often did not complete assignments. She felt he was often tired.

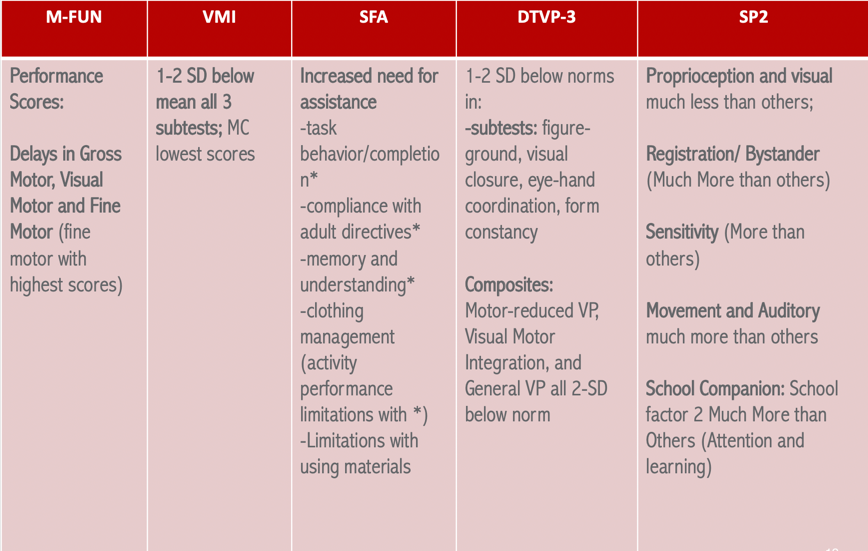

According to the teacher, he disliked PE class, but he seemed to enjoy music and art class and he liked science. She did say he liked math too but sometimes he had a hard time copying the math problems from the board and getting his math finished. So, even though he was good at mental math, the copying of the problems was very difficult for him. Figure 5 shows the assessment results.

Figure 5. Assessment results.

The M-FUN results are not surprising because we knew he had some motor issues. Gross motor, visual motor and fine motor all came back as delayed. However, his fine motor had higher scores which means that they were not quite as involved as his gross motor and the visual motor functioning. On the VMI, he scored one to two standard deviations below the mean on all three subtests. However, motor coordination had the lowest scores, and that is the activity where you connect the dots. This makes sense as this one requires some motor control. I started to get a hypothesis as he was lacking the control for this subtest and that score was lower than the drawing one. I began to wonder about his oculomotor skills. The SFA said that he had an increased need for assistance on-task behavior and compliance with adult directives. These results are very similar to the teacher's report. He also had issues with memory and understanding, and clothing management. From the DTVP-3, which measures figure-ground visual closure, eye-hand coordination, form constancy, and all those visual perceptual things, he was below the norm by one to two standard deviations. He was also two standard deviations below the norm for motor-reduced VP, visual-motor integration, and general visual perception. What you are beginning to see is that it does not really make a difference if there is a motor component involved (like using a pencil to follow a track) or just using his eyes. This is a red flag that there is something going on at those lower hierarchal levels of development with respect to ocular motor functioning as well as attention. Finally, Sensory Profile 2 (SP2) showed that proprioception and visual were much less than others. He was showing low registration for those, but he also had sensitivity more than others. He also showed much more registration/bystander tendencies. And then for movement and auditory areas, these were much more than others. We are starting to see a picture here of vestibular challenges, proprioceptive challenges, visual challenges, and attention and learning using the SPSC (Sensory Profile School Companion). These results support that he was most likely missing some of those lower-level skills.

When I did the screening to test this by asking him to track and scan and tested functional saccades, I do not think it will be a surprise to tell you that this was all difficult for him. Saccades were really the area of dysfunction as well as cognitive loading with smooth pursuit. To assess cognitive loading was smooth pursuits, you have them follow an object in nice smooth patterns about 10 inches from their face. Then, you start asking them very basic questions that are long term memory kinds of things like, what did you like for breakfast? Or, who is your favorite TV character? What is your dog's name? If you see a huge discrepancy between their smooth pursuits and the cognitive loading, you will then know that there are some significant oculomotor control issues, and they are going to affect school performance. All of this information aligns with not only things we heard from school but also concerns the mom had as well.

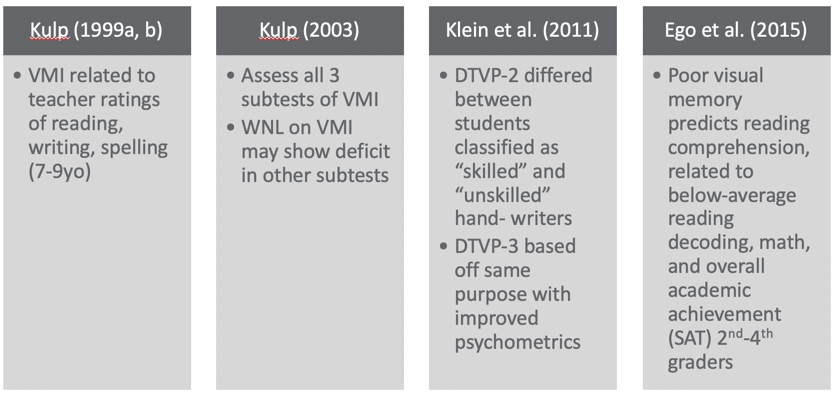

Assessment Research

I wanted to give you just a little bit of information from the research on assessments so that this can inform your clinical reasoning (see Figure 6). Some of this is older but it is quite interesting.

Figure 6. Overview of assessments.

The VMI is commonly used, and it is cheap and easy. In this study by Kulp (1999), it was related to teachers' ratings of reading, writing, and spelling. I think a lot of people use VMI for handwriting. It is not an effective tool to identify handwriting issues, but rather it is more effective at showing us writing, reading, and spelling challenges for ages seven to nine. This is why I chose it for Patrick. Another study, by Kulp (2003), showed that all three subtests of the VMI are really important instead of just doing one. This is because you might get "within normal limits" on one, but you might get that result on another one. For example, the blue subtest focuses on visual discrimination and if they can match a picture. Thus, it does not really give you a lot of information on other areas. Thus, Kulp recommends doing all three subtests. This is very interesting about the DTVP-2 in a study by Klein et al. (2011). The results actually differed between students classified as skilled and unskilled hand writers. So, if you want to look for handwriting challenges and figure out where the difficulties are coming from, the DTVP-3, the new version, is based on the same purpose as it just has better psychometrics. They tightened up the validity of the reliability scores in the newer version. Lastly, poor visual memory predicts reading comprehension (Ego et al., 2015). Kids who have poor visual memory also will have below-average reading, poor math decoding, and academic achievement scores for second to fourth graders. Visual memory becomes very important for this age group if they are struggling in school. This is why I use the DTVP. The TVPS (Test of Visual Perceptual Skills) is okay too but it does not capture the composite of motor versus non-motor.

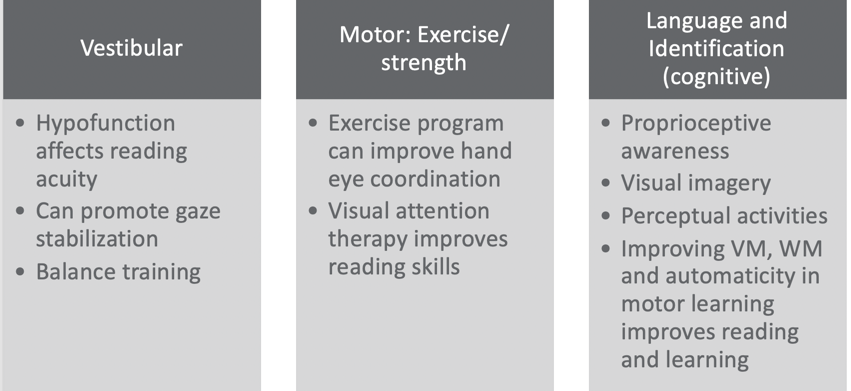

EBP Remediation: Skeffington’s Model

Figure 7. EBP remediation using Skeffington's Model. (Christy, 2019; Shelly-Tremblay et al., 2012; Gibson et al., 2015; Garje Mona et al. 2015; Jamal et al. 2019; Grisham et al., 2007; Sweeney et al., 2014; Mast et al., 2014, Gaymard et al., 2017; Van Hecke et al., 2019.)

Using a Skeffington's Model approach (see Figure 7), if we look at the vestibular function of Patrick, we start to realize that if you have an under-responsive vestibular system, it can affect reading acuity. Vestibular promotes gaze stabilization and balanced training related to your vestibular function for vision. He actually seemed to have a hypo functioning vestibular system according to the SP2; however, he had some over responsiveness when you looked at his post-rotary nystagmus. For the centering or motor area, exercise programs can improve hand-eye coordination. From multiple studies, the reasoning is that as the kids start to have better posture, strength, and endurance, they begin to be more aware of their bodies. Body scheme or kinesthetic awareness can also improve. They also found that visual attention therapy improves reading skills, and that visual attention therapy could result from exercise and strength programs. We also know that if someone can sustain sitting upright for a while and has postural control, they also will have better cognitive attention. However, visual attention really relies more on staying upright and sustaining a gaze on something, then there will be improved visual attention. It makes sense that if I have more postural strength and dissociation, I can do that.

Then, I combined language and identification together as the cognitive components of vision. What is very cool about this one is that proprioceptive awareness becomes very important per the research. The more proprioceptively aware you are, the higher the level of visual perceptual skills. They seem to correlate. Visual imagery became extremely important within this. You have to have some visual imagery and that involves the retina. The vestibular system interacts with the visual system as well as the proprioceptive system to provide stability within your environment. As we negotiate, through our activities, it allows for an image to be obtained by the retina and this happens as you are also moving your head to access things. Your body then integrates it. It starts to get really complicated very quickly. If I put all these things together, I start to become someone who has this dynamic ability to hone in on something, look at it, get that retinal involvement, and then start that whole processing procedure. We need the whole body in order to see. Studies also show that perceptual activities become extremely important. And if you improve visual memory (VM) and working memory (WM), as well as automaticity in motor learning, you will see improved reading and learning. This one I think really speaks to us as OTs. We might not necessarily think that that correlates to reading and learning skills, but it really does fit in this language and identification piece. If you think about it, with visual memory you now have a bank of things from which to pull, and then you can start moving up the hierarchal ladder. Working memory is being able to utilize your functional memory at the moment, and that does require visual memory as well as auditory memory. Automaticity is saying that my motor learning ability has moved beyond the skill level, and I am not in the cognitive learning level of motor learning. I have moved into the third level of motor learning which is that autonomous level where I can do something without really making a lot of errors and having to think about it. If we can get a child to the autonomous level, we will see that reading and learning flourish. This is really focusing on handwriting for the most part because that is often the tool that we use (written communication in our school occupations). If a child is focused on writing, it is really going to be hard for them to do anything else. And, when we are stuck in the motor learning cognitive phase, it can frustrating, exhausting, and hard. If we can get them beyond that level to where they are more automatic, it is much more functional for learning. A child cannot learn if they are dividing their attention. Figure 8 reinforces what we just talked about.

Figure 8. Sensory, motor, and cognitive development (Hk playgroup, n.d.).

The bottom part of this triangle is the very basic sensory system. The next one is the sensory-motor development. This includes body sense, postural security, bilateral awareness, and motor planning. This 2nd tier has been informed by the sensory system. Once this is pretty good, you start to develop more perceptual-motor development which is auditory language skills, visual-spatial skills, eye-hand coordination, oculomotor control, and postural adjustment. You start to see how this developmental pattern starts to make sense with vision and cognition. The top tier is academic learning, daily living activities, and the occupations that we focus on. They need a lot of these underlying skills to be able to do it. The foundation or the sensory piece is so important to vision, but all of these sensory pieces inform our subjective processing of visual information.

Remediation Approaches

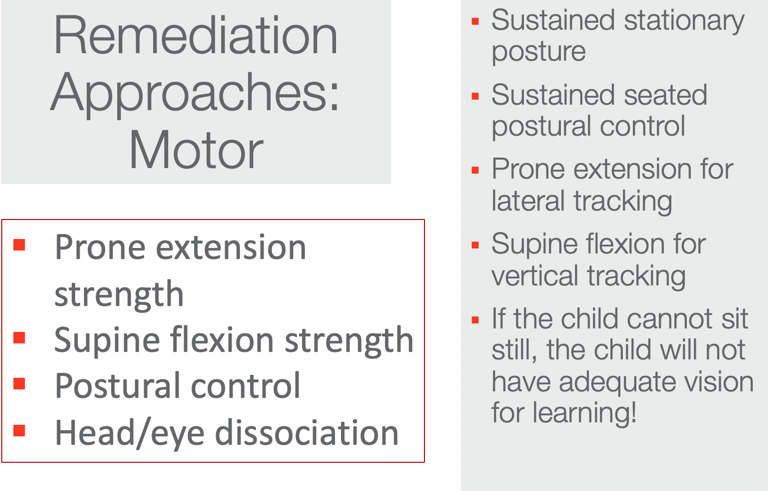

Let's now see some of the remediation approaches that were used with Patrick (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Motor approaches.

If I am going to treat oculomotor skills to try to build visual attention, I need to focus on postural strength, endurance, postural control, and head eye association. Now, all of a sudden, they become little visual receptors. They can receive information while moving within their environment. What does that look like in therapy? These can be all sorts of cool activities that really work on improving that strength like yoga and crawling around doing things to get stronger. It is important to have this postural strength and control for tracking and adequate vision for learning. I want to explain to you a little bit more about prone extension and supine flexion. I want you to take your fingers and put them on the back of your neck. In the middle of your neck, lightly palpate while your eyes are tracking laterally or horizontally. I want you to feel what is happening in the back of your neck as you are scanning. You should feel a contraction. There is a direct relationship between your lateral or horizontal tracking and your posterior or extensor neck muscles. This is the same if you go into the front of your neck. This is a little trickier to find. Lightly palpate the front of your neck during vertical tracking, and you should also feel a very slight contraction. These areas can facilitate improved tracking if you can strengthen them.

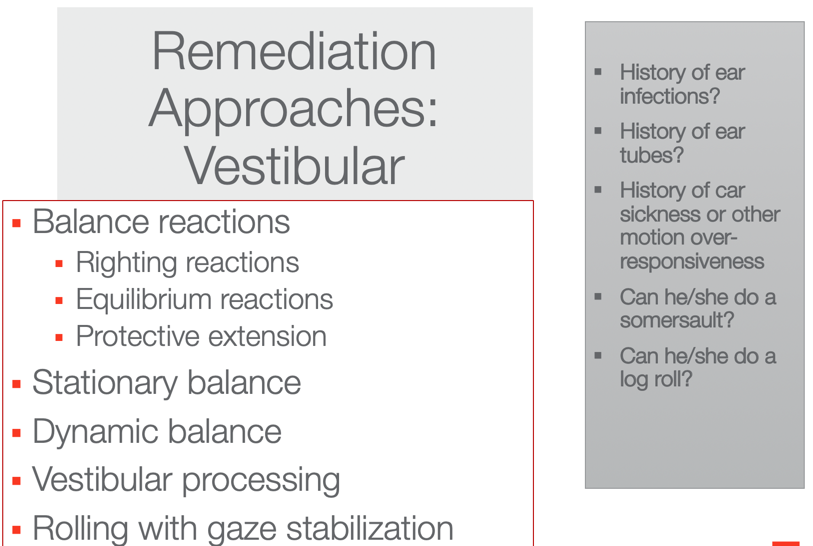

Figure 10. Vestibular approaches.

We want to determine a history of ear infections, ear tubes, or car sickness. Can they somersault? Can they log roll? These can tell us how their vestibular system is working. And, these are activities that we want to work on with these kids to really get that antigravity circle of Skeffington's Model working. I also want to make sure that their balance reactions are working. I like to use an onion swing for this kind of thing. Another activity is rolling with gaze stabilization. When they are ready and are not getting nauseous from these movements, we can have them log roll or somersault forward or backward and then have them stop and practice gaze stabilization on something. Then, we can have them roll again, stop, focus their gaze, and so on. There are a million ways to do it that can be fun. With these types of approaches, you are going to see a huge change in the function of the saccades.

Case Application: Patrick

- Perform top-down occupational analysis and find a discrepancy

- Identify and incorporate occupation-based practice to address discrepancies

- Final occupation-based activity mimics real activity in context

- Incorporate adaptations as needed (including education and consulting)

- Embed vestibular, motor, and cognitive-perceptual based upon visual hierarchy and discrepancies

Let's apply a top-down approach to our friend Patrick. During this top-down occupational analysis, we want to incorporate occupation-based practice to address those discrepancies as we do not function without occupation. Thus, the final occupation-based activity should mimic a real activity in context. We want to incorporate adaptations as needed including educating the parents and the teachers. We also want to embed vestibular, antigravity, motor, centering and cognitive-perceptual activities. This is where it can get a little tricky. What I want you to appreciate here is that if you see a deficit, like pattern recognition, you treat one level below. You do not start at the level of dysfunction in the hierarchal development, but you always start one level below.

If I find that Patrick's issue is at the lowest level, there really is not anything lower to go so that is where we are going to start. I would send them to optometry anyway to make sure visual acuity is okay. If I had a kid whose issue was visual memory and that was the deficit that really stuck out to me on whatever assessments I did, I would start with pattern recognition. Again, it is important to go one level below.

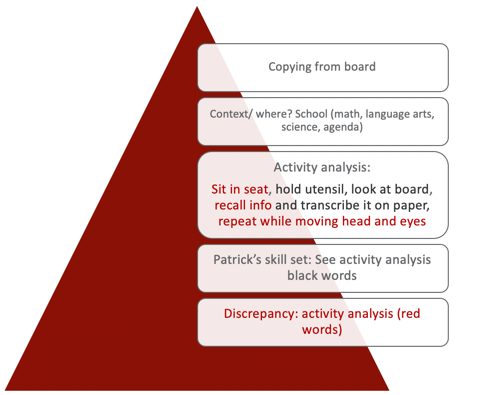

Figure 11 shows this top-down approach that I was just talking about.

Figure 11. Top-down analysis 1.

If the goal if for Patrick to copy from the board, we want Patrick to be able to copy from the board. In his class, he had to copy a journal topic, math problems, and spelling words from the board. I could have gotten a little more focused on this pyramid, but I kept it general. What is the context? Where does it happen? This activity happens in school during math, language arts, science, and also his agenda. The next thing we would do is an activity analysis. As OTs, this is our special sauce. This is what makes us really unique. I realized this the more I do presentations to other disciplines. We really know how to do an activity or occupational analysis. I did a very basic one here but he has to sit in his seat, hold the utensil, look at the board, recall the information, transcribe it on the paper, and then repeat that as he moves his head and eyes until he gets everything copied. The next level of the process is looking at Patrick's skill set. Those are the black words in the activity analysis. He could hold the utensil, he could look at the board, and he could transcribe it. If this is true, what is the discrepancy between the activity analysis and Patrick's skills? This information is the red text. Sitting in the seat, recalling the information, and then repeating it over and over while moving his head and eyes was difficult for him. Right away that tells me that he has difficulty with centering, vestibular function, and probably something to do with the language like the recalling or identification of the information. I suspect this is because he has difficulty with proprioception. The focus of my treatment then is getting towards a sustained posture, working on the association of head and eyes with gaze stabilization, and visual memory. Activities that I could do in our therapy sessions would be things like Mad Libs. Some of you might have done these as kids. I love Mad Libs and the kids really enjoy them. Secret decoding is another fun one. Other activities I use are scavenger hunts and obstacle courses. I can then embed the things that I need a child to work on like vestibular gaze stabilization and postural strengthening. We used to do something called "Patrick Olympics" which was where we would just come up with different activities. I would pick some and he would pick some. He would try to do all of the activities to get a gold medal. Here's another one in Figure 12.

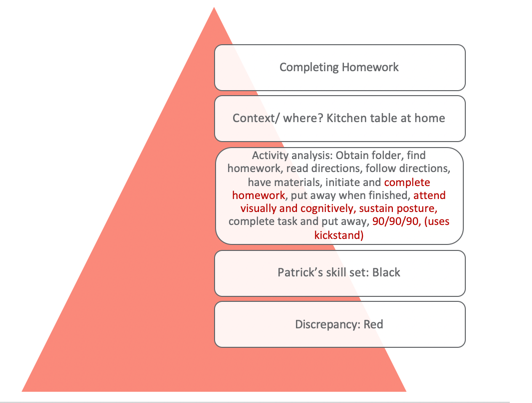

Figure 12. Top-down analysis 2.

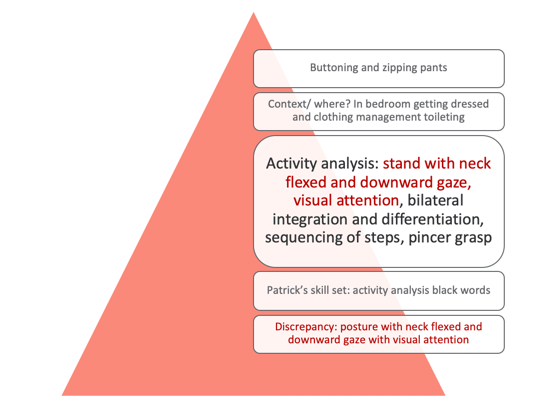

This one is for completing homework. You can see in the activity analysis the different steps involved. Again, Patrick's skills are the ones that are in black and then the discrepancies are those in red. Our focus is going to be completing the task which requires sustained attention, postural and bilateral integration, and environmental supports, which I am going to get to in a second. Activities we used included Mad Libs and fantasy football. For the fantasy football activity, we had to come up with something that would be similar to completing a homework assignment. I made it second grade appropriate but it had football charts and plays as he is really into that. He loved that because he got to draw up these little football charts and he got to teach them to me. The goal was that he had to finish the assignment. He also loved to mimic a fireman so I had him "stop, drop and roll" through an obstacle course. This tapped into his vestibular system. Figure 13 looks at buttoning and zipping his pants.

Figure 13. Top-down analysis 3.

Again, you can see in the activity analysis that his skill set is in black and the discrepancies are in red. With this one, I am focusing on his posture with sustained neck flexion and downward gaze with sustained visual attention. This can be a very hard task for kids. For occupations, we did mini golf which was great for this posture. We also did an egg game. The egg game is where you have to carry an egg in a little pouch. While you are walking, you have to watch the egg with a downward gaze and go very slow or the egg will fall out. If it breaks, you lose. It is silly but kids love it. Crab soccer is another great one as it facilitates that neck flexion in sustained pattern. We also did a game called fire rescue. This was done on a scooter board in supine. He had to find "fires" throughout the environment, and he had to keep his neck in a flexed position. Again, it is important to embed some of these activities that align with the Skeffington model approach.

Evidence-Based Approaches: Adaptive Approaches

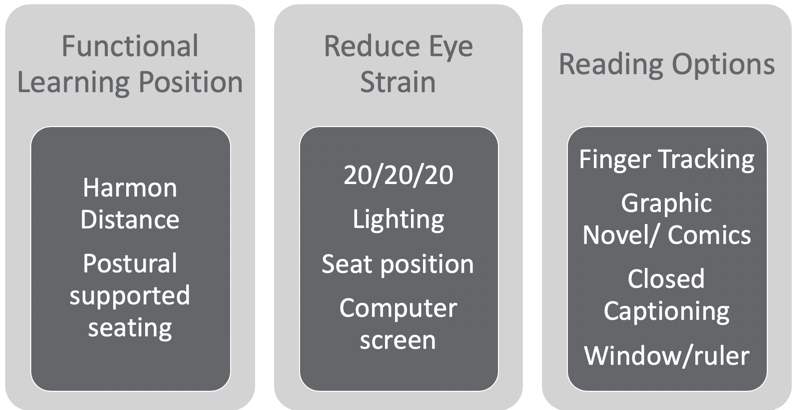

Figure 14 shows some adaptive approaches.

Figure 14. Adaptive approaches.

The functional learning position is really important and this is called the Harmon distance. The Harmon distance is the distance from your fist resting on your cheek to your elbow. This is an evidence-based approach for maximizing visual learning. We also need to look at postural supported seating. If somebody is struggling, we want to make sure that they are supported. This is not news to any of you but really making sure that the desk and the table fit the kid. You know that in the school system or even at home, that is not always the case.

Another approach is to reduce eye strain. A great tip is the 20/20/20 rule. Every 20 minutes, you stare at an object 20 feet away for 20 seconds to recalibrate your eyes and relax the tension. You also want to make sure the lighting is good, and fluorescent lights are not ideal. Again, the seated position is important. We want to make sure that they are not somewhere where they constantly have to strain. For computer use, they really should take a break every 20 minutes from the computer screen. And, if you can get them on a black background with a white font instead of white with black, it's better. The other thing with reading on the computer is that there is no point of reference. For example, on a post-it note or piece of paper, there are four corners of orientation. If I turn it to the backside, again, there are four corners of orientation. There is a sequence to how you read with the boundaries. This does not happen when you are reading a book on a Kindle or on a computer. You lose those corners of orientation. You and I know how to read so we do not need those corners of orientation as our skills are already intact. However, kids are still learning and gaining skills. They need those corners of orientation for reading comprehension, sequencing of events, and trying to find things. It really sort of happens in a vacuum when you are in a Kindle or an online book. Some of you might have even experienced that when you are unable to find a passage or page. Researchers are starting to find that reading online is not good for learning to read or for school development.

Figure 15. Adaptive approaches.

If kids use their fingers to read, let them. It helps them so do not take that approach away. Graphic novels and comics are fantastic. They give them a visual supplement to the reading, and the text is usually not as dense. Closed captioning is probably one of the best ways to help. You can have them watch videos and have the closed captioning at the bottom. This has been shown to cause parts of the brain for reading to light up in a functional MRI. That also works really well for kids with dyslexia. I also like using the window method or a ruler to help with reading. This can be used to block out whatever is below and helps them to focus.

Patrick tends to use a kickstand, or his arm to support his head. Can we set up his desk to achieve the Harmon distance (see Figure 15) and give him proper support? We already know that Patrick is using his finger so we would want to let him keep doing that. I also think the closed captioning would be great. I could recommend that his mom use closed captioning for tv and movies. I could also investigate if he would like to read graphic novels or comics.

- https://www.trianglevisions.com/blog/your-childs-vision-development/

- https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/children-vision-development

- http://www.healthofchildren.com/E-F/Eye-and-Vision-Development.html

- VERA vision screening program https://visualscreening.com/

- https://www.covd.org

- AMAZING blog with lots of sections: https://visionhelp.wordpress.com/

Here are some helpful resources. VERA is a free vision screening program, and they invite occupational therapists to join in. It is awesome, and I highly recommend you check it out. I also love the VisionHelp blog on the bottom. There are a bunch of sections to help you learn some in-depth stuff about vision. The developmental optometrist on there is amazing, and he explains everything. COVD is a group of vision folks that come together so that is a good one as well.

Alenizi, M. A. K. (2019). Effectiveness of a program based on a multi-sensory strategy in developing visual perception of primary school learners with learning disabilities: A contextual study of Arabic learners. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 8 (1), 72-104.

Bense, M. S. (2016). The effect of an oculomotor-vestibular-proprioceptive sensory stimulation programme on reading skills in children aged 8 to 12 years 11 months (Doctoral dissertation).

Chokron, S., & Dutton, G. N. (2016). Impact of cerebral visual impairments on motor skills: implications for developmental coordination disorders. Frontiers in psychology, 7 , 1471.

Christy, J. (2019). Use of vestibular rehabilitation in the pediatric population. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4 (6), 1399-1405.

Cohen, D., & Xavier, J. (2017). Oculomotor impairments in developmental dyspraxia. The Cerebellum, 16 (2), 411-420.

Ego, A., Lidzba, K., Brovedani, P., Belmonti, V., Gonzalez‐Monge, S., Boudia, B., ... & Cans, C. (2015). Visual–perceptual impairment in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57 , 46-51.

Garje Mona, P., Dhadwad, V., Yeradkar, M. R., Adhikari, A., & Setia, M. (2015). Study of visual perceptual problems in children with a learning disability. Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research, 4 (3), 492-97.

Gaymard, B., Giannitelli, M., Challes, G., Rivaud-Péchoux, S., Bonnot, O., Cohen, D., & Xavier, J. (2017). Oculomotor impairments in developmental dyspraxia. The Cerebellum, 16 (2), 411-420.

Klein, S., Guiltner, V., Sollereder, P., & Cui, Y. (2011). Relationships between fine-motor, visual-motor, and visual perception scores and handwriting legibility and speed. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 31 (1), 103-114.

Kulp, M. T., & Sortor, J. M. (2003). Clinical value of the Beery visual-motor integration supplemental tests of visual perception and motor coordination. Optometry & Vision Science, 80 (4), 312-315.

KULP, M. T., Edwards, K. E., & Mitchell, G. L. (2002). Is visual memory predictive of below-average academic achievement in second through fourth graders? Optometry & Vision Science, 79 (7), 431-434.

Jamal, K., Leplaideur, S., Leblanche, F., Raillon, A. M., Honoré, T., & Bonan, I. (2019). The effects of neck muscle vibration on postural orientation and spatial perception: A systematic review. Neurophysiologie Clinique .

Mast, F. W., Preuss, N., Hartmann, M., & Grabherr, L. (2014). Spatial cognition, body representation, and affective processes: The role of vestibular information beyond ocular reflexes and control of posture. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 8 , 44.

Quaid, P., & Simpson, T. (2013). Association between reading speed, cycloplegic refractive error, and oculomotor function in reading disabled children versus controls. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 251 (1), 169-187.

Sales, R., & Colafêmina, J. F. (2014). The influence of eye movement and the vestibularocular reflex in reading and writing. Revista CEFAC, 16 (6).

Solan, H. A., Shelley-Tremblay, J., & Larson, S. (2007). Vestibular function, sensory integration, and balance anomalies: A brief literature review. Optometry and Vision Development, 38(1), 13.

Van Hecke, R., Danneels, M., Dhooge, I., Van Waelvelde, H., Wiersema, J. R., Deconinck, F. J., & Maes, L. (2019). Vestibular function in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 1-23.

Quint, N. (2020) . Pediatric case study: Child with oculomotor and perceptual challenges. OccupationalTherapy.com , Article 5120. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com

Nicole Quint has been an occupational therapist for over 15 years, currently serving as an Associate Professor in the Occupational Therapy Department at Nova Southeastern University, teaching in both the Masters and Doctoral programs. She provides outpatient pediatric OT services, specializing in children and adolescents with Sensory Processing Disorder and concomitant disorders. She also provides consultation services for schools, professional development, and special education services. She provides continuing education on topics related to SPD, pediatric considerations on the occupation of sleep, occupational therapy and vision, reflective therapist, executive functions, leadership in occupational therapy and social emotional learning.

What is Pediatric Occupational Therapy? Scenarios of OT for Kids

by Niagara Therapy, LLC | September 12, 2022

What is Pediatric Occupational Therapy? Pediatric OT Scenarios

Occupational therapy is a form of physical and mental rehabilitation that focuses on performing activities required in daily life. In the case of pediatric occupational therapy, this generally focuses on getting children to engage in play, school, and peer interactions. Pediatric occupational therapy helps children develop skills including vision, perception, coordination, strength, sensory processing, writing, emotional management, and social interaction.

The overall goal of occupational therapy is to improve a child’s ability to effectively interact with and learn from the environment in order to develop skills necessary for daily function. Often this simply looks like play to a bystander, but play is the way children learn! An occupational therapist can use many fun materials or even games to encourage development of new skills in a fun and creative way.

What Specific Areas Can OT Address?

Occupational therapy can help children with many different aspects of life. For example, it can help children with using appropriate social skills and regulating emotions. Being able to dress oneself and having the appropriate self care fine motor skills to use utensils, pencils, button a button or zip up a zipper, are all areas of focus in occupational therapy. Many children have difficulty with knowing left from right, which can affect the ability to orient clothing for dressing, scan to read a book or know how to tie shoes. Occupational therapy can address this left/right awareness or “laterality” in daily activities.

Sensory integration is another area that occupational therapy can address. Improved sensory integration is often achieved by expanding the variety of textures and tastes in a child’s diet and improving tolerance to various clothing textures. An OT could help develop a sensory “diet” with the goal to improve attention or transitions between tasks that are necessary in the school setting.

Many times kids will present with difficulty with visual perception and ocular motor skills . OT can provide exercises and activities to improve these skills which can affect school and homework activities as well as participation in many sporting activities. OT can also address gross motor skills, motor planning and executive function.

There are times children exhibit symptoms of retained primitive reflexes in their function. Primitive reflexes are involuntary motions that often help to protect infants. Typically these are integrated into more mature and voluntary responses; however, if not integrated, these reflexive patterns can create functional concerns. Retained reflexes can look like difficulty paying attention, anxiety, impaired fine or gross motor coordination, difficulty with balance or reading, difficulty with left-right awareness or a multitude of other concerns. Occupational therapy can provide guidance to integrate primitive reflexes. With this developmental foundation, children can improve the skills needed to make daily function more efficient.

There are times that the most effective way for a child to complete a task is to utilize adaptive equipment. Some examples of adaptive equipment are adapted eating utensils or pencil grips, slant boards, wheelchairs or crutches, and splints. An OT will also often recommend sensory equipment for the home or school setting as well.

Does My Child Need Occupational Therapy?

Occupational therapy can be helpful for a wide variety of challenges that children face, and can help children improve skills related to school, play, and daily life in general. Occupational may be helpful for your child if they are dealing with any of the following:

- Sensory integration difficulties or limited emotional management

- Limited diet and food sensitivity

- Weak and uncoordinated movements

- Poor handwriting

- Difficulty focusing in school

- Difficulty reading

- Difficulty tying shoes, buttoning, and dressing

- Spasms/Muscle Cramps/Spasticity

- Needing specialty equipment (writing, eating, sensory tools, etc.)

Feel free to get in touch with us to learn more about how our team of expert occupational therapists can help your child reach their maximum potential.

Common Scenarios and Case Studies of Pediatric Occupational Therapy

Niagara Therapy’s team of occupational therapists has helped many children over the years. We’ve outlined some common scenarios to help give you a better understanding of what occupational therapy looks like in the real world.

JH is a 6 year old girl who has a difficult time playing on the playground. Her teacher noticed that she falls frequently and seems clumsy. She loves the social aspect of tee ball, but has a hard time connecting the bat to the ball.

She was referred to occupational therapy, and we noted that she had difficulty with visual perception, using both hands together, and had a hard time crossing midline in activity. Each of these areas is vital when trying to swing a bat or catch a ball. She also had some retained primitive reflexes that have affected development of these skills.

We determined that occupational therapy intervention would be helpful for JH. Treatment would focus on improving visual perception, bimanual use, midline crossing, and primitive reflex integration.

Scenario 2

PR is really struggling with handwriting and copying his assignments from the board at school. His OT found that he has hand weakness and poor fine motor skills as well as limited core strength affecting sitting posture and balance. He also demonstrates difficulty with visual perception and ocular motor skills which contribute to the challenge of handwriting.

We determined that occupational therapy services would help to improve core strength, fine motor skills, and address visual concerns. By regularly completing tasks or exercises as recommended by an OT, PR should gain skills to improve his abilities in these areas, and his parents and teachers should see improvements in school work.

HC is an 8 year old who cannot tie his shoes or button a shirt. He also requires some assistance to put on his clothing and has trouble crossing midline in activity. In OT, he demonstrates impaired hand strength and fine motor skills as well as some retained primitive reflexes.

We determined that occupational therapy can help him learn left/right and spatial awareness to

improve his ability to orient clothing. He is also given exercises and activities to do at home to improve strength and fine motor skills that would allow him to more easily tie a shoe or button a button. Reflex integration can also develop underlying skills to help to make these tasks easier.

YG sustained a concussion, has been experiencing headaches, and has difficulty organizing schoolwork or cleaning her room. When evaluated in OT she was found to have ocular motor and visual perceptual impairments that are contributing to headaches and difficulty with reading.

We determined that occupational therapy can help to improve visual deficits and address executive function.

Scenario 5

KL is unable to tolerate wearing various textures of clothing and is a very picky eater. This has made getting ready for school and mealtimes very frustrating for everyone in the house.

Our occupational therapist had KL’s caregiver complete a sensory profile to evaluate the various areas of sensory processing in order to determine how those sensory abilities affect daily function. The OT also observed and interacted with the child to determine how to plan the best intervention for KL. We evaluated sensory preferences and assisted in exploring strategies to make these areas less stressful for both the child and parent.

What Do All of These Children Have in Common?

Each of these children has some observable functional difficulties with underlying causes that can be addressed in occupational therapy! As you can see, OT addresses a variety of areas. Undeveloped or underdeveloped skills can make everyday tasks challenging. Determining and addressing these areas is crucial for improved function. An occupational therapist will look at the big picture to help determine what skills may need improved to ultimately affect function.

Pediatric Occupational Therapy with Niagara Therapy

Your kids are important to us at Niagara Therapy, and we love to get to know them and their interests in order to help them enjoy every moment and be as independent as possible every day. We utilize tools and techniques that are not available anywhere else in the region. Interactive Metronome and Brain beats are computerized programs that can help improve coordination and attention as well as auditory processing. The Neuro Sensoriomotor Integrator or NSI is a fun & interactive technological tool we can use to improve letter and number recognition as well as ocular motor and visual perceptual skills. Our therapists use various programs to improve body awareness, visual perception, handwriting, emotional regulation and explore new foods.

We offer speech, physical and occupational therapies at Niagara Therapy and use a team approach driven by your goals. We offer sessions between 7 AM and 7 PM and focus on only one client at each session. If your child is experiencing difficulties with independent function or meeting developmental milestones, call us at 814-464-0627.

Quick Links

- PT for Kids

- PT for Adults

- OT for Kids

- OT for Adults

- Speech Therapy for Kids

- Speech Therapy for Adults

Mon- Fri: 7 AM – 7 PM

- Meet The Team

- How To Get Started

- Advanced Therapies in Erie, PA

- Pediatric Physical Therapy

- Pediatric Occupational Therapy

- Pediatric Speech Therapy

- Physical Therapy

- Occupational Therapy

- Speech Therapy

EMAIL [email protected] PHONE 814-464-0627 ADDRESS 2631 W 8th St Erie, Pennsylvania 16505

Let us know what’s on your mind!

Occupational Therapy Interventions for Children and Youth Ages 5 to 21 Years

- Standard View

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Stephanie Beisbier , Susan Cahill; Occupational Therapy Interventions for Children and Youth Ages 5 to 21 Years. Am J Occup Ther July/August 2021, Vol. 75(4), 7504390010. doi: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.754001

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Evidence Connection articles provide a clinical application of practice guidelines developed in conjunction with the American Occupational Therapy Association’s (AOTA’s) Evidence-Based Practice Program. Each article in the series summarizes the evidence from the published reviews on a given topic and presents an application of the evidence to a related clinical case. The articles illustrate how the research evidence from the practice guidelines can be used to inform and guide clinical decision making. In this Evidence Connection article, we describe a case report of a child receiving occupational therapy services and summarize the evaluation and intervention processes for supporting sleep, activities of daily living, and social participation. The practice guideline on this topic was published in the July/August 2020 issue of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy ( Cahill & Beisbier, 2020 ).

Occupational therapy practitioners work with children and families to identify meaningful goals for performance and participation and to make decisions about the types of intervention that will be used as well as the context in which services will be provided. In using child- and family-centered care principles, occupational therapy practitioners incorporate the priorities and perspectives of both the child and the family. Occupational therapy practitioners provide habilitative services that promote skill acquisition and participation in meaningful daily life activities.

- Self-Care Routines

Children often receive occupational therapy services to address issues with participation and performance in activities of daily living (ADLs) typical for their age group. Successful completion of self-care routines helps them to build confidence and autonomy. Significant positive outcomes are associated with the use of functional tasks to improve children’s performance of self-care routines ( Laverdure & Beisbier, 2021 ). Explicit skills training in ADLs and structured practice, including tasks with graded difficulty provided in natural contexts, is effective in supporting development and engagement in self-care skills. Caregiver and family involvement is critical to providing occupational therapy services to children, and increased family involvement allows occupational therapy practitioners to model strategies to encourage the child’s participation and leads to skill mastery. Caregiver coaching and feedback are particularly effective in promoting children’s independence with ADL tasks and reducing the need for caregiver assistance ( Laverdure & Beisbier, 2021 ).

- Play and Social Participation

Play is an important occupation of children. Statistically significant positive outcomes are associated with the use of play-based interventions to increase the skills associated with children’s social participation ( Cahill & Beisbier, 2020 ). Play-based activities that involve peers and support the child’s use of intrinsic motivation are effective for increasing playfulness. Coaching, peer modeling, and instruction on how and when to use specific skills (e.g., showing empathy) are effective in increasing collaborative play and play engagement ( Laverdure & Beisbier, 2021 ). Caregiver and family involvement is also critical to the development of play and the skills associated with sustained social participation ( Cahill & Beisbier, 2020 ).

Sleep is a factor in overall health, and it can affect the daily functioning of children and their caregivers. Consideration of sleep quality and sleep routines should be part of each child’s occupational profile. The use of rigorous exercise as an intervention should include guided practice for the child and caregiver and follow-up to assess effectiveness and considerations for modification to the exercise and activity plan ( Cahill & Beisbier, 2020 ). Interventions that include coaching of caregivers and focus on building sleep routines and healthy sleep habits can have a significant impact on overall quality of sleep and daily functioning for both the child and members of the household ( Cahill & Beisbier, 2020 ).

- Clinical Case

Jacob is a 9-yr-old boy who is in third grade and attends a public elementary school, where he has an Individualized Education Program and receives special education instruction for math as well as school-based occupational therapy and speech-language pathology services. Jacob lives with his father, his younger sister, and his paternal grandmother in a three-bedroom home. Jacob’s father works full time and commutes approximately an hour to and from work. Jacob’s grandmother helps Jacob get ready for school in the morning and greets him when the bus drops him off at home at the end of the day.

Jacob’s favorite pastime is reading comic books and graphic novels alone in his room. He also enjoys being outdoors and doing a weekly swimming activity with his father and sister. Jacob remembers to put dirty dishes in the sink after meals and clean up his toys at the end of the day. Jacob is quiet and slow to warm to strangers, including children his own age. Although Jacob likes to be at the park, he does not try to interact with other children and seems fearful when they approach to ask him to play. His grandmother has noticed that he has difficulty completing self-care tasks that other children his age perform independently, such as brushing his teeth and dressing himself. Jacob also has trouble falling asleep and sleeping through the night. Jacob was referred to occupational therapy by his pediatrician with a diagnosis of delayed milestone in childhood (Code R62.0; International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision; World Health Organization, 1992 ) after receiving low scores on a developmental screening checklist.

Occupational Therapy Assessment and Findings

In advance of the evaluation session and on the basis of the referral, the occupational therapist provided Jacob’s father with a sleep tracking document and the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire ( Owens et al., 2000 ) to complete at home. On the day of the evaluation session, the occupational therapist met the family at their home. The occupational therapist began the initial evaluation by interviewing Jacob, his father, and his grandmother to develop an occupational profile ( American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2021 ). During the interview, the occupational therapist learned about Jacob’s occupational history and gained important information about Jacob’s interests and values, strengths, performance patterns, and performance skills. The occupational therapist was also able to ask questions about how Jacob performed occupations in different contexts and identified contextual aspects that supported and inhibited his engagement. During the interview, Jacob and his father and grandmother identified barriers and challenges related to Jacob’s initiating and performing ADLs, following and maintaining sleep routines, and sustaining peer interactions.

The occupational therapist also completed the Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale ( Maenner et al., 2013 ) and reviewed the sleep record with Jacob and his family. The occupational therapist walked with Jacob and his father to the local playground and used the Test of Playfulness in observing Jacob ( Skard & Bundy, 2008 ). Table 1 summarizes the evaluation findings.

Goal Setting and Priorities for Intervention

Jacob and his family reviewed the evaluation findings with the occupational therapist and identified priorities for intervention. The occupational therapist learned that Jacob’s sleep routine (or sleep pattern) has a significant impact on the family. Jacob and his family identified getting to sleep and getting enough hours of consecutive sleep as the main barriers to his occupational performance and daily routine. Jacob expressed pride in being able to prepare a cold snack and help with dishes after dinner. However, he expressed a desire to brush his teeth and hair and get dressed independently. Jacob’s grandmother would also like him to be able to blow his nose without support. Jacob and his family recognized his relative strength in social interaction with family members and expressed a desire to increase Jacob’s opportunities to play with peers and initiate social interactions.

Occupational Therapy Intervention

The occupational therapist used a combination of practice experience, information from current literature, and the unique client context to collaborate with Jacob and his family to develop an intervention plan that was informed by evidence and would maximize Jacob’s strengths and leverage his current support systems. The occupational therapist used the Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Children and Youth Ages 5–21 Years ( Cahill & Beisbier, 2020 ) as a tool to guide decision making and considered Jacob’s presentation in relation to the diagnoses addressed in the practice guidelines. The occupational therapist then reviewed the practice guidelines, paying special attention to the information in the clinical recommendations table and the implications specific to outcomes that were aligned with Jacob’s priorities.

The occupational therapist found

strong strength of evidence for the use of functional tasks and cognitive-based interventions to improve performance and engagement in self-care activities and routines;

strong strength of evidence for the use of play-based interventions to improve social participation; and

moderate strength of evidence for education, coaching, and cognitive strategies to improve sleep.

Evidence from the practice guideline, Jacob’s interests, and the family’s preferences informed the occupational therapy intervention plan. Sessions were conducted in the natural environment (i.e., home, playground, and community swimming pool) and included training, coaching, and consultation during the occupations of play, self-care, and social participation. Sleep was addressed through a coaching and consultation model. Family-centered, community-based sessions occurred 2 times per week over 8 wk.

Intervention 1: Self-Care

The occupational therapist collaborated with Jacob and his family to address grooming and dressing and establish a plan that included graded introduction of more complex tasks and shaping, thought restructuring, and parent involvement ( Drahota et al., 2011 ). For example, during dressing, the occupational therapist first introduced a short-sleeved pullover t-shirt. Once Jacob demonstrated independent performance with the short-sleeved t-shirt, a long-sleeved t-shirt was introduced and then, finally, a button-down shirt. The occupational therapist challenged Jacob’s negative statements (e.g., “My grandma won’t ever help me again”) and supported positive thought restructuring (e.g., “My grandma will still help me if I need it, but I can try to do this on my own”). Jacob’s grandmother was coached to support his attempts at mastery and to provide feedback and praise. Shaping, or providing positive reinforcement when Jacob’s performance approximated the desired performance, was used to encourage him to complete tasks independently and in accordance with established social norms (i.e., using own toothbrush rather than a family member’s and blowing his nose with a tissue instead of a hand towel). The occupational therapist used the shaping technique when praising Jacob as he made attempts at mastery or completed a small component of a task, such as putting his arm through a sleeve, even when he was unsuccessful at fully donning the shirt.

Intervention 2: Social Participation

The occupational therapist formed an after-school play group for same-age peers with the purpose of providing opportunities for all the children to develop relationships, practice social communication skills, and expand play repertoires ( Wolfberg et al., 2015 ). The group included five children with varying levels of communication and interaction skills and used a consistent routine, which included a greeting activity, peer-mediated play choices, and a closing activity. Visual supports, such as activity choice boards, were provided, and all participants were encouraged to engage in spontaneous and flexible play with others.

The occupational therapist facilitated Jacob’s play initiations by encouraging him to speak to children who appeared to capture his interest and helped peers interpret the ways in which Jacob expressed interests and enjoyment, such as squeezing his hands together while jumping up and down. The occupational therapist challenged all the play group participants to extend their play by systematically adjusting the amount of adult support needed and encouraged them to gain one another’s attention and engagement in reciprocal play during games such as catch. The therapist provided parent-friendly information that outlined the importance of peer interaction for developing skills associated with meaningful social participation. The therapist actively coached Jacob’s father as they used problem-solving strategies to identify appropriate games and activities to maximize interaction with peers and assisted them in determining the appropriate level and timing of support to provide Jacob ( Kretzman et al., 2015 ).

Intervention 3: Daily Routines Promoting Sleep

After each 30-min playground session, the family (Jacob, Jacob’s father, and his sister) and the occupational therapist went to the nearby community swimming pool. Swimming is part of the family’s weekly routine. The therapist coached the family through a 45- to 60-min aquatic activity sequence ( Oriel et al., 2016 ). The aquatic sequence included warm-up movements, such as arm circles and marching, and a cardio segment with options such as jogging and performing jumping jacks in the pool. The warm-up activities were followed by a series of pool games that involved the family members and willing peers. The games included tag and other imaginative and action-oriented games (e.g., “hot and cold” and “sharks and minnows”). The last two elements of the aquatic sequence included time for unstructured play or swimming and a cool-down activity.

The occupational therapist provided Jacob and his family with encouragement to remain active and brainstormed other activities that could be done in the pool. Each night, Jacob’s father logged Jacob’s sleep behaviors to share with the occupational therapist. Jacob’s family and the occupational therapist discussed the difference in Jacob’s sleep patterns and noted improvements when he had the opportunity to go to the pool compared with days when he engaged in less physical activity. To support Jacob on days when the pool visit is not feasible, the therapist used sleep coaching strategies ( Sciberras et al., 2011 ) aimed at building consistent bedtime routines and habits. The family actively identified unhealthy bedtime habits and problem solved ways to shift to healthy practices.

Occupational Therapy Outcomes

After 8 wk, Jacob demonstrated significant progress and achieved the outcomes that were established at the beginning of occupational therapy intervention. Jacob began initiating and performing ADLs, following and maintaining sleep routines, and sustaining peer interactions. Jacob fell asleep, on average, within 20 min of going to bed and slept for an average of 7 hr. His grandmother reported improved daily functioning for the family (i.e., less conflict) because the sleep quality of everyone in the home had improved. Jacob’s ratings on the Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale ( Maenner et al., 2013 ) increased from “does with help” to “does independently” for dressing and grooming. Jacob initiated play with two peers on the playground within 10 min and engaged in parallel play (e.g., swinging on swings and singing with a peer) and cooperative play (e.g., playing tag) without adult assistance.

Occupational therapy practitioners use child- and family-centered care principles to provide services to children in their natural environments. The child’s natural or typical context provides opportunities to practice skills while contending with unique and sometimes unanticipated factors. Such occasions encourage problem solving and collaboration among the occupational therapy practitioner, the child, and the child’s family members. Occupational therapy practitioners should collaborate with family to design interventions to address self-care, sleep, and social participation through the use of functional tasks, play-based activities, education, coaching, and cognitive strategies.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Data & Figures

Evaluation Findings

| Assessment Tool | Results |

| Occupational Profile ( ) | exploring environments, expressing emotions, showing preferences, making choices, and following transitions with adult support difficulty initiating and performing activities of daily living, following and maintaining sleep routines, sustaining peer interactions Jacob’s priorities are to feel more comfortable playing with other children and to dress without his grandmother’s assistance. |

| Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire ( ) | unafraid of the dark, unafraid of sleeping alone, no presence of parasomnias (e.g., grinding teeth, sleep walking, or night terrors) amount of time to fall asleep, amount of sleep per night, restless sleep, and tired upon awakening |

| Sleep record completed by father for 7 consecutive days | >90 min time to sleep 5 of 7 days. 60–75 min time to sleep 2 of 7 days. Sleep duration 4–5 consecutive hours of sleep 7 of 7 days. |

| Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale ( ) | independent with toileting, eating, drinking, bathing, putting away toys, preparing a cold snack, and clearing table after dinner inconsistent and below-age expectations for performance with brushing teeth and hair, dressing, and nose blowing because of limited motor and process skills |

| Test of Playfulness ( ) | appears to feel safe during play and is beginning to incorporate people into play. Two incidences of peer social engagement (responded to peer’s question) after parent prompt; one incident of cooperative play on playground equipment with parent directive and ongoing support limited communication and interaction skills for cooperative play, responding to other’s facial or body cues, and engaging in challenges. Does not independently initiate peer play in 30 min in familiar setting with familiar peers; 2 additional attempts for cooperative play on playground with parent directive failed. Demonstrates onlooker play behaviors. Does not try to overcome obstacles or barriers to play. |

Supplements

- Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Children and Youth Ages 5–21 Years

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

- Special Collections

- Conference Abstracts

- Browse AOTA Taxonomy

- AJOT Authors & Issues Series

- Online ISSN 1943-7676

- Print ISSN 0272-9490

- Author Guidelines

- Permissions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Copyright © American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc.

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Occupational Therapy Pediatric Case Study Examples

Select the pediatric case for study, review child's diagnosis and medical history, set up an initial meeting with the child and parents or guardians, prepare a detailed initial assessment plan, conduct initial assessment on physical, cognitive and emotional capabilities of the child, record observations during the initial assessment, evaluate child's clinical reports, develop an occupational therapy treatment plan based on findings, approval: treatment plan.

- Develop an occupational therapy treatment plan based on findings Will be submitted

Prepare necessary therapy materials and equipment

Conduct therapy sessions.

- 1 Sensory integration activities

- 2 Fine motor skill exercises

- 3 Hand-eye coordination games

- 4 Social skills building exercises

- 5 Cognitive tasks

Monitor and record the child's progress during each therapy session

Provide feedback and recommendations to parents or guardians, regularly update the treatment plan based on child's progress, re-evaluate the child's capabilities periodically, prepare a comprehensive final report based on case study, approval: final report.

- Prepare a comprehensive final report based on case study Will be submitted

Discuss final report and future recommendations with parents or guardians

Final Report and Future Recommendations - {{form.Meeting_Date}}