Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020 Dec.

The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health [Internet].

4 strategies and actions: improving maternal health and reducing maternal mortality and morbidity.

Given the importance of maternal health for our families, communities, and nation, addressing the unacceptable rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity calls for a comprehensive approach that addresses health from well before to well after pregnancy. A singular focus on the perinatal period would ignore upstream health factors associated with chronic conditions as well as other environmental and social factors that contribute to poor outcomes. 3 HHS has laid the framework by providing recommendations for preventive services that promote optimal women’s health. 79 , 80 , 81 The strategies and actions in this document are based on these recommendations as well as consensus statements and recommendations from other organizations. The following sections outline specific actions for addressing the conditions and risk factors outlined above as well as other factors that may impact maternal health. The opportunity for action exists across the spectrum of women and families; states, tribes, and local communities; healthcare professionals; healthcare systems, hospitals and birthing facilities; payors; employers; innovators, and researchers. Individuals, organizations and communities should select and implement actions as applicable to their needs. Regardless of organization or group, everyone can help to improve maternal health in the U.S.

EVERYONE CAN

- Recognize the need to address mental and physical health across the life course—starting with young girls and adolescents and extending through childbearing age. 3

- Support healthy behaviors that improve women’s health, such as breastfeeding, 82 smoking cessation, 83 and physical activity. 84

- Recognize and address factors that are associated with overall health and well-being, including those related to social determinants of health. 22

- Understand that maternal health disparities exist in the U.S., including geographic, racial and ethnic disparities ( Figures 3 – 7 ), and work to address them.

- Acknowledge that maternal age and chronic conditions, such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes are risk factors for poor maternal health outcomes (See prior sections “ Differences in Maternal Mortality and Morbidity ” and “ Risks to Maternal Health ”).

- Learn about early ‘warning signs’ of potential health issues (such as fever, frequent or severe headaches, or severe stomach pain, to name a few 85 ) that can occur at any time during pregnancy or in the year after delivery.

- Work collaboratively to recognize the unique needs of women with disabilities and include this population of women in existing efforts to reduce maternal health disparities. 26 , 27 , 28

- WOMEN AND FAMILIES

Women can play a critical role in promoting, achieving, and maintaining their health and well-being, often with the support of fathers, partners, and other family members. Preventive health and wellness visits can provide women with screenings, risk factor assessment, support for family planning, immunizations, counseling, and education to promote optimal health. 79 Women can engage in healthy practices, monitor their overall health, and address conditions they may have such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity. Many resources in the form of books, mobile applications, social media, and guides provide information about what to expect before, during and after pregnancy as well as information on important health behaviors, preventive care, medications, and potential risks.

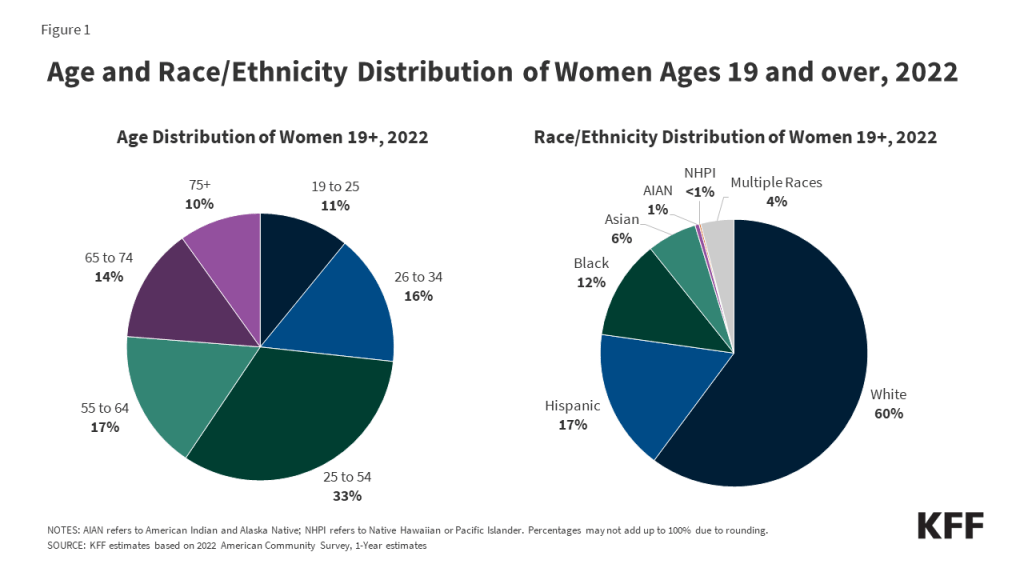

Prenatal appointments provide the opportunity for healthcare professionals to monitor pregnancy, perform prenatal screening tests, 85 discuss questions and concerns that women may have, including plans for delivery and infant feeding, and provide recommendations to promote a healthy pregnancy. 86 A statewide study of all live births in Pennsylvania and Washington showed that starting prenatal appointments in the second trimester instead of the first, or attending fewer prenatal appointments, was associated with a higher risk of unhealthy behaviors and adverse outcomes, including low gestational weight gain, prenatal smoking, and pregnancy complications. 87 Data also show disparities in initiating and/or receiving prenatal care, with non-Hispanic white (82.5 percent) and Asian women (81.8 percent) more likely to receive prenatal care in the first trimester than all other racial and ethnic groups, including Hispanic (72.7 percent), non-Hispanic black (67.1 percent), AI/AN (62.6 percent), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander women (51.0 percent). 17

Women should also be supported after delivery to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes. For example, breastfeeding has demonstrated benefits for infants and can also be beneficial to mothers, including decreased bleeding after delivery and reduced risks of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, breast and ovarian cancer. 88 Black mothers are less likely to initiate breastfeeding than white or Hispanic mothers (74.0 percent versus 86.6 percent and 82.9 percent, respectively). 89 These data suggest opportunities for understanding and addressing these disparities.

WOMEN AND FAMILIES CAN

Focus on improving overall health 90.

Try to engage in healthy behaviors and practices by participating in regular physical activity, 84 eating healthy, 91 getting adequate sleep, 92 , 93 and getting ongoing preventive care that includes immunizations 57 and dental care. 94 Recognize that oral health is part of overall health and that pregnant mothers may be prone to gingivitis and cavities. 95 Abstain from tobacco 96 and other potentially harmful substances, including marijuana, 97 prior to and during pregnancy. As there is no amount of alcohol known to be safe during pregnancy or while trying to become pregnant, women should consider stopping all alcohol use when planning to become pregnant. 98 Follow medical advice for chronic health conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, learn family medical history, and adopt or maintain healthy lifestyles. Women who are planning or may become pregnant should take a daily folic acid supplement. 99 For women who are entering pregnancy at a later age or with chronic diseases or disorders, learn how to minimize associated risks through ongoing preventive and appropriate prenatal care.

PROMOTE POSITIVE INVOLVEMENT OF MEN AS FATHERS/PARTNERS DURING PREGNANCY, CHILDBIRTH, AND AFTER DELIVERY

Promote men’s positive involvement as partners and fathers. 100 Include men in decision-making to support the woman’s health, to the extent that it promotes and facilitates women’s choices and their autonomy in decision-making. 101

ATTEND HEALTH CARE APPOINTMENTS 79

Women should attend primary care, prenatal, postpartum, and any recommended specialty care visits and provide health information, including pregnancy history and complications, to their health care providers during all medical care visits, even in the years following delivery. 101 , 102 Know health numbers, such as blood pressure and body weight, and record them at each visit. If recommended, continue to monitor and record blood pressure in-between visits. 103 Those with diabetes should check and record your blood sugar regularly. 104

COMMUNICATE WITH HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS

Ask questions and talk to healthcare professionals about health concerns, including any symptoms you experience, past health problems, or concerns about potentially sensitive issues, such as IPV and substance use. 105 Be persistent or seek second opinions if a healthcare professional is not taking concerns seriously (See the Joint Commission “Speak Up” guide for ways patients can become active in their care 106 ).

LEARN HOW TO IDENTIFY PHYSICAL AND MENTAL WARNING SIGNS DURING AND AFTER PREGNANCY

Utilize resources that provide information about the changes that occur with a healthy pregnancy and how to recognize the warning signs 85 for complications that may need prompt medical attention. The CDC’s Hear Her campaign seeks to raise awareness of warning signs, empower women to speak up and raise concerns, and encourage their support systems and providers to engage with them in life-saving conversations. 107 Learn to recognize the symptoms of postpartum depression such as feelings of sadness, anxiety, or despair, especially those that interfere with daily activities, and seek support. 108

ENGAGE IN HEALTHY BEHAVIORS IN THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD

If electing to breastfeed, seek support as needed. Resources include healthcare providers, lactation consultants, lactation counselors, peer counselors, and others. Attend postpartum visits as they are the best way to assess physical, social, and psychological well-being and identify any new or unaddressed health issues that could affect future health. 109 Continue engaging in healthy behaviors after pregnancy, such as managing chronic disease and living a healthy lifestyle.

- STATES, TRIBES AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES

States, tribes, and local communities can create environments that are supportive of women’s health and tailored to local needs and challenges. They can create the infrastructure needed to engage in healthier lifestyles and to ensure access to high quality medical care.

Healthy People provides national goals to guide health promotion and disease prevention efforts in the U.S. and highlights the importance of creating social and physical environments that promote good health for all. 22 Often referred to as social determinants of health, the conditions into which people are born, live, work, play, worship, and age can strongly influence their overall health. 22 Examples of social determinants include access to educational opportunities, availability of resources to meet daily needs (e.g., healthy food options), public safety and exposure to crime. 22 Examples of physical determinants include natural and built environments (e.g., green space, sidewalks, bike lanes), and housing and community design, and exposure to physical hazards. 22 Case studies have demonstrated that health outcomes can be improved where there is a concerted and coordinated effort involving both healthcare systems and communities where their patients live. 110 , 111 , 112

Perinatal regionalization or risk-appropriate care 113 is a promising approach for improving maternal safety as it has been shown to be an effective strategy for improving neonatal outcomes, 114 though more research is needed to assess its impact on maternal health outcomes. States can explore this approach as well as other strategies to increase access to quality care, such as the adoption of telemedicine, and the review of the scope of practice laws (what health care professionals are authorized to do), licensure and recruitment policies. Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs) are state or multi-state networks of multidisciplinary teams that work to improve maternal and infant outcomes by advancing evidence-informed clinical practice through quality improvement initiatives. 115

States, tribes and local health agencies play a role in providing essential services to protect the health and promote the well-being of their communities through education, prevention, and treatment. They provide support for community-driven initiatives and evidence-based practices that address topics such as emerging infections (e.g., COVID-19), sexually transmitted infections, and immunizations. The role of public health is changing due to increased demands from chronic disease, new economic forces, and changing policy environment. 116 The National Consortium for Public Health Workforce released a Call to Action addressing the need for strategic skills in the public health workforce to enable collaboration across sectors to address the social and economic factors that drive health. 117

MMRCs Multidisciplinary committees that perform comprehensive reviews of deaths among women during and within a year of the end of pregnancy

Surveillance data can help to monitor trends and focus efforts to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. States, tribes, and communities have the opportunity to assess maternal deaths, injuries and illnesses and identify strategies for preventing these adverse outcomes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) supports states in establishing MMRCs to perform comprehensive reviews of deaths among women during pregnancy or within a year after birth, obtain better data on the circumstances and root causes surrounding each death, and develop recommendations for the prevention of these deaths. 117 However, MMRC reviews can lag by several years, and some states have not yet created MMRCs. Ensuring that MMRCs collect uniform data, such as through the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application (MMRIA), 118 will provide comprehensive national data on maternal mortality and result in more timely and detailed reporting to inform prevention efforts.

Representative population-based data on pregnancy and disability are lacking. 118 State health departments, researchers, and other stakeholders can work together to address gaps in surveillance and identify best practices for reducing health disparities, including among pregnant women with disabilities.

STATES, TRIBES, AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES CAN

Create social and physical environments that promote good health 22.

Improve factors that are associated with health and wellness, including safe communities, clean water and air, stable housing, access to affordable healthy food, public transportation, parks and sidewalks, and other social determinants of health. Support prevention of domestic violence and abuse. Consider addressing areas recognized as “food deserts” (areas with little access to affordable, nutritious food) or “food swamps” (areas with an abundance of fast food and junk food outlets). Encourage healthy eating initiatives tailored to the community such as community gardens, farmer’s markets, school programs, businesses’ support of healthy foods, as well as participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) for eligible women.

PROVIDE BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT AT THE INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNITY LEVELS

Establish policies to support women’s abilities to breastfeed, to reach their breastfeeding goals once they return to their communities and worksites, and thus achieve full health benefits of breastfeeding for their babies and themselves. 119 , 120

STRENGTHEN PERINATAL REGIONALIZATION AND QUALITY IMPROVEMENT INITIATIVES

Consider adopting a classification system for maternal care that ensures women and infants receive risk-appropriate care in every region utilizing national-level resources, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) joint consensus document on levels of maternal care, 121 and other state-level guidelines. Develop coordinated regional systems for risk-appropriate care that address maternal health needs.

PROMOTE COMMUNITY-DRIVEN INITIATIVES 101 AND WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

Pursue promising community-driven initiatives, such as the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s Healthy Start program 122 and the Best Babies Zone Initiative, 123 funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, that aim to reduce disparities in short-term (e.g., access to maternal healthcare), medium-term (e.g., breastfeeding and postpartum visits), and/or long-term outcomes (e.g., premature births and low birth weight infants). Develop or recruit a workforce that supports the maternal health needs of the community. Incentivize healthcare professionals with obstetric training to serve in rural, remote or underserved areas. 124

ENSURE A BROAD SET OF OPTIONS FOR WOMEN TO ACCESS QUALITY CARE

Examine scope of practice and telehealth laws to maximize women’s access to a variety of healthcare professionals, 125 especially in rural regions and underserved areas, 125 while ensuring procedures are in place to address obstetric emergencies. Engage and collaborate with federal and tribal health systems within states to avoid duplication of services and support access to a full range of care. Support partnerships between academic medical centers and rural hospitals for staff education and training and improved coordination and continuity of care. Support state and regional PQCs in their efforts to improve the quality of care and outcomes for mothers and infants.

SUPPORT EVIDENCE-BASED PROGRAMS TO ADDRESS HEALTH RISKS BEFORE, DURING AND AFTER PREGNANCY

Provide funding for local implementation of evidence-based programs, such as home-visiting, substance use disorder treatment, tobacco cessation, mental health services and other programs as recommended by the Community Preventive Services Task Force. 126 Support local efforts to prevent family violence and provide support for women experiencing IPV. Educate the public about risk factors for high-risk pregnancies, pregnancy-related warning signs, risk-reducing behaviors, and the importance of prenatal and postpartum care.

IMPROVE THE QUALITY AND AVAILABILITY OF DATA ON MATERNAL MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

Address challenges with vital statistics and data reporting, 127 , 128 such as racial misclassification, 129 and misclassification and documentation of the causes of death, and improve the accuracy of maternal mortality and morbidity reporting for national comparison and analysis. Enhance data and monitoring of racial and ethnic disparities. Expand and strengthen MMRCs to review and assess all pregnancy-associated deaths (the death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of the termination of pregnancy, regardless of the cause) 130 and identify opportunities for prevention.

- HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS

While states, tribes, and local communities help to ensure infrastructure and programmatic support for maternal health, individual healthcare professionals provide education, support, and care for women before, during, and after pregnancy.

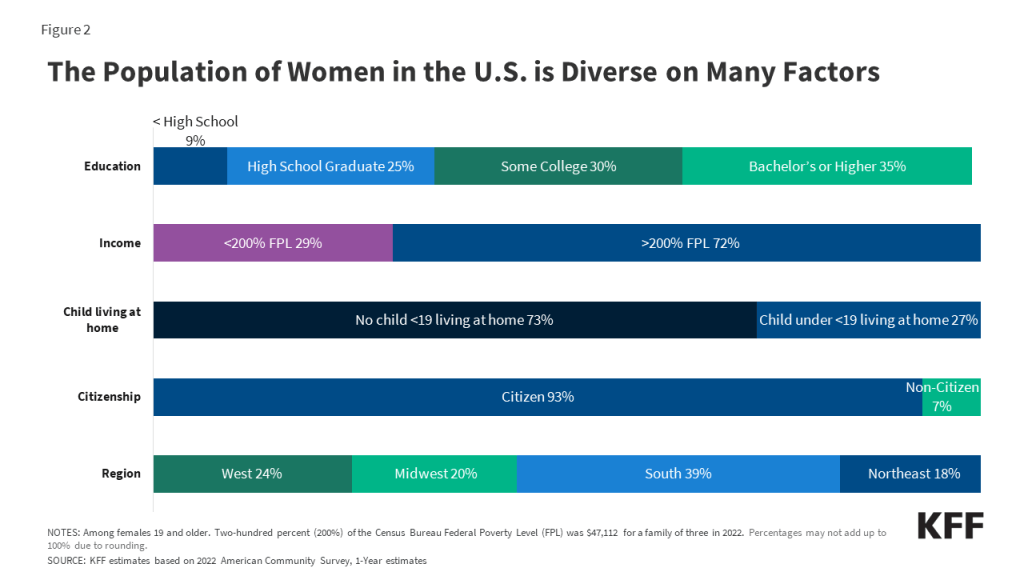

The full range of healthcare professionals and teams should understand factors that contribute to women’s overall health and work to identify and mitigate potential pregnancy risks. Every medical appointment or interaction with health care professionals is an opportunity to ensure that standards of care and the full needs of women are being met. Given the vast diversity in geography, economy, and racial and ethnic make-up of communities across the U.S., healthcare professionals can ensure that the care they provide is scientifically-sound and culturally appropriate to the individual and their respective community. 101

Fragmented care across healthcare settings may inhibit providers from having a full understanding of a patient’s medical condition(s) and risks. 131 , 132 Many opportunities exist across providers to improve communication, including through care coordination, adoption of mobile applications, and enhanced interoperability of electronic health records (EHRs). Even healthcare professionals who do not normally care for pregnant women play a role in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality. Engaging and coordinating care among a diverse set of healthcare professionals, such as primary care providers, emergency department providers, dentists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, psychologists, and social workers, can be challenging, but strengthens the ability to identify, address, and prevent harm.

Various professional associations play a key role in developing standards of care to provide guidance on screenings, preventive care, prenatal and postpartum care, and management of obstetric emergencies. Associations are valuable resources for developing evidence-based guidelines on areas important to maternal health.

HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS CAN

Ensure quality preventive healthcare for all women, children, and families.

Increase knowledge, awareness, and utilization of clinical practice tools such as those associated with recommendations from the USPSTF; 133 the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines; 79 Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents; 134 and the CDC. Use preventive health care and wellness visits to conduct screenings, assess risk factors, provide support for family planning, offer immunizations, and provide education and counseling to promote optimal health. Include such topics as folic acid supplementation for all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy, 100 breastfeeding, nutrition, physical activity, sleep, oral health, substance use, and injury and violence prevention. 91

ADDRESS DISPARITIES SUCH AS RACIAL, SOCIOECONOMIC, GEOGRAPHIC, AND AGE, AND PROVIDE CULTURALLY APPROPRIATE CARE 110 IN CLINICAL PRACTICES

Increase self and situational awareness of and attention to disparities. Participate in research to determine if provider training may improve patient-provider interactions. Learn how to identify and work to address inequities within health systems, processes, and clinical practices using standardized protocols. Provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services that respect and respond to individual needs and preferences. 135

HELP PATIENTS TO MANAGE CHRONIC CONDITIONS

Reduce the burden of chronic conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, as well as mental health and substance use disorders (See prior section “ Risks to Maternal Health ”) on women’s health across the lifespan by helping them to manage these conditions. For example, refer women at risk to diabetes educators, nutritionists, and mental health professionals. Conduct cardiovascular risk evaluation, to include history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes, 136 and provide risk reduction strategies for women of childbearing age before, during, and after pregnancy.

COMMUNICATE WITH WOMEN AND THEIR FAMILIES ABOUT PREGNANCY

Listen to women and their family members’ concerns before, during, and after delivery. Engage the family in creating a supportive environment. Discuss and make available options for traditional practices that may vary by culture and personal preferences. Educate about warning signs 85 during pregnancy and the postpartum period. 137 Use culturally acceptable and easily understandable methods of communication. 138 Link women with a substance use disorder to family-centered treatment approaches. 139

FACILITATE TIMELY RECOGNITION AND INTERVENTION OF EARLY WARNING SIGNS DURING AND UP TO ONE YEAR AFTER PREGNANCY

Track patient vital signs (e.g., blood pressure) across healthcare visits, including prenatal, initial hospital admission, and postpartum visits. Learn to recognize and react to signs and symptoms associated with hemorrhage, pre-eclampsia, hypertension, cardiomyopathy, infection, embolism, substance use, and mental health issues. Use screenings and tools to identify warning signs early so women can receive timely treatment. Coordinate care across obstetrician-gynecologists and primary care providers and consult with specialists, as needed.

IMPROVE HEALTHCARE SERVICES DURING THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD AND BEYOND

Communicate the importance of postpartum visits, including the ACOG recommendation for an initial assessment within the first 3 weeks postpartum followed by ongoing care as needed and a comprehensive visit within 12 weeks after delivery. 110 Non-obstetric providers can have an important role to play. For example, pediatricians could screen for maternal mental health during well-baby visits utilizing validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. 140 Other non-obstetric providers should ask about prior pregnancies when taking medical history and be aware of pregnancy-related morbidities that can occur up to one year post-delivery and those that raise life-time risks, such as gestational diabetes, 141 gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia, 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 and follow recommended guidelines. 102 , 103

PARTICIPATE IN QUALITY IMPROVEMENT AND SAFETY INITIATIVES TO IMPROVE CARE

Engage with state and/or national quality collaboratives and patient safety initiatives to improve maternal health. (See section “ Health Systems, Hospitals, and Birthing Facilities ”). Consider using resources, such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Toolkit for Improving Perinatal Safety 142 which includes patient safety bundles, TeamSTEPPS® (team strategies and techniques to enhance performance and patient safety 143 ) and simulation training.

- HEALTH SYSTEMS, HOSPITALS, AND BIRTHING FACILITIES

Health systems provide comprehensive care for the full range of women’s health before, during, and after pregnancy. Within these systems, hospitals provide the vast majority of delivery services. In 2018, approximately 98 percent of all live births occurred in hospital settings. 17 Over the past two decades, many rural counties have lost their hospital-based obstetric services. 144 In these areas, women are more likely to have out-of-hospital births and to deliver in hospitals without obstetric units, as compared to those living in rural counties that maintained hospital-based obstetric services. 145 Additionally, in rural or underserved areas, access to maternal care in the prenatal and postpartum period may be limited. 125

Hospitals and health systems can address this through strategies such as telemedicine and linking facilities that do not offer planned childbirth services with those that do, and facilitating prompt consultation and safe transportation to the appropriate level of maternal care. The designation of levels of care, as outlined in the ACOG/SMFM Levels of Maternal Care, helps to ensure that women receive care at facilities that are best equipped to address their needs. 122 The CDC developed the Levels of Care Assessment Tool (LOCATe) to assist states and other jurisdictions in assessing and monitoring levels of care. 146

Quality improvement strategies, such as participation in PQCs 116 and implementation of maternal “safety bundles,” may help hospitals and health systems to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. 147 A safety bundle is a set of practices and policies designed to identify appropriate and timely actions the health care staff can take in response to maternal complications. The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) is a maternal safety and quality improvement initiative that addresses preventable causes of maternal morbidity and mortality through the implementation of bundles to identify and swiftly respond to common pregnancy-related complications. 148 The President’s FY 2021 Budget proposes $15 million to expand the AIM Program. Adoption of safety bundles by hospitals requires leadership and clinical team commitment, as well as training and implementation support.

Offering diverse provider types for maternal care, such as family physicians, midwives and support personnel (e.g., doulas) in hospitals and other healthcare settings may support women’s preferences. Midwifery care is provided in hospital settings, birth centers, and home settings, and can be a valuable part of women’s health care. 148

Medical history associated with pregnancy and delivery does not always travel with women in their future medical records or across different types of providers. Addressing this is key to ensuring coordinated care across providers within and between health systems.

HEALTH SYSTEMS, HOSPITALS AND BIRTHING FACILITIES CAN

Ensure availability of risk-appropriate care across the healthcare system.

Ensure staff, equipment, and services are available to address the health needs of women with both low- and high-risk pregnancies. Implement guidelines for levels of maternal care at all birthing hospitals and facilities and work with states to adopt standardized criteria and uniform definitions for levels of maternal care (See prior section, “ States, Tribes and Local Communities ”).

IMPROVE ACCESS TO CARE AND COMMUNICATION WITH PATIENTS

Adopt methods for improving access to care and communication, especially in rural or underserved areas or when conditions limit face-to-face interactions, while ensuring patient safety and quality of care. These methods can include telehealth and remote monitoring, among others. Work with health insurers to address gaps in access to medical facilities, equipment, information, and transportation for women with disabilities. 149

IMPROVE THE QUALITY AND SAFETY OF PERINATAL CARE

Provide evidence-based clinical practice, including utilization of standardized protocols related to pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period. Consider other resources, such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Toolkit for Improving Perinatal Safety. 143 Participate in state, or regional PQCs to implement quality improvement efforts and monitor progress with standardized data. Consider routine surveillance and monitoring of “near misses” and other SMM events.

PROVIDE COMPREHENSIVE DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS

Ensure discharge processes include education for women and families about warning signs (e.g., Association of Women’s Health, Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses’ Save Your Life discharge instructions 150 ), and the importance of postpartum visits. 110

TRAIN HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS IN NON-OBSTETRIC SETTINGS ABOUT OBSTETRIC EMERGENCIES

Standardize protocols and training to respond to obstetric emergencies in the emergency department 8 and other non-obstetric settings, to include transportation to the most appropriate facility for care. Train non-obstetric clinicians to consider and seek recent pregnancy history when assessing patients. 8

ENCOURAGE OBSTETRIC CARE-TRAINED PROVIDERS TO SERVE IN RURAL, REMOTE AND UNDERSERVED AREAS 125

Support additional training in obstetric care in residencies for family physicians, especially those who will practice in rural, remote or underserved areas.

OFFER A VARIETY OF HEALTHCARE PROVIDER AND SUPPORT OPTIONS TO FIT MATERNAL PREFERENCES AND NEEDS

Leverage and incorporate midwives into hospital obstetric care and other community programs. 126 Support maternal-infant home visiting and away-from-home programs/pre-maternal homes (where pregnant women from remote areas can stay before the birth of their child 101 ) to support care.

ADDRESS DISPARITIES AND PROVIDE CULTURALLY APPROPRIATE CARE IN HEALTHCARE SETTINGS

Provide education and training on disabilities. Identify and work to address inequities within health systems, processes, and clinical practices. Ensure the availability of culturally and linguistically appropriate services that respect and respond to individual needs and preferences. 136

SUPPORT BREASTFEEDING PRACTICES

Implement hospital or birthing center initiatives, such as the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, to help women successfully initiate and continue breastfeeding their infants. 151 Ensure access to lactation support providers for breastfeeding women.

COORDINATE WITH COMMUNITY RESOURCES

Consider coordination with resources, such as group prenatal programs, 152 WIC, 153 home visiting programs, 154 and others that address social determinants of health. Consider alternative approaches to expanding access and education, to include use of community health workers. 155

ENHANCE COMMUNICATION WITHIN AND ACROSS HEALTHCARE SETTINGS

Adopt methods to ensure the seamless transition of information between providers along the care continuum, including strengthening communication and care coordination among obstetrician-gynecologists and other health care professionals.

Health insurance coverage is a key determinant of health care access and utilization. 156 Payors – including private health insurers, state-based Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) -- can play a key role in addressing maternal health by helping to ensure affordability of and access to high quality preconception, prenatal, delivery, and postpartum care. 157 , 158

Reimbursement for, and access to, comprehensive care, such as preventive services recommended by the USPSTF (A or B rating), 134 Women’s Preventive Services Initiative, 79 and Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents, 135 can ensure women and children receive recommended services. These services may include preventive screening (e.g., blood pressure, weight status, diabetes, infectious diseases, sexually transmitted infections, cancer) and vaccinations, breastfeeding support, mental health support, substance use screening and treatment, and screening for intimate partner and family violence.

Ensuring a wide range of healthcare professionals are included in a health plan’s network may broaden women’s access to comprehensive services that address the full spectrum of care. Coverage of programs, such as those that fund transportation to appointments, or technology, such as applications that facilitate chronic condition management and timely and convenient communication, can reduce barriers to care.

Overall, while there are many strategies that payors can consider for helping to improve maternal health, including those outlined below, more research is needed to assess the impact of these actions on maternal health outcomes.

PROMOTE ACCESS AND PAYMENT FOR WOMEN’S HEALTH SERVICES ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

Develop services and networks to provide care before, during, and after pregnancy, including pre-pregnancy counseling. Reimburse time spent with healthcare professionals to discuss healthy lifestyles, family planning, optimal management of chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, obesity), substance use disorders, and mental health conditions. Reduce cost barriers and ensure payment options are understood by women and their families.

ALIGN FINANCIAL INCENTIVES WITH THE FULL RANGE OF PERINATAL CARE

Provide financial reimbursement and quality incentives related to improving maternal care for women of all races and ethnicities and implementing standards of care. Implement value-based payment incentives for innovative ways of delivering high quality care. Support efforts to reduce barriers that patients may face when accessing healthcare, such as transportation, language needs, or geographic isolation. Promote telehealth, as appropriate, for women in underserved, rural or remote areas or under conditions that limit face-to-face interaction and support remote monitoring of highly prevalent and harmful conditions like hypertension and diabetes.

ENSURE A WIDE RANGE OF HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS ARE INCLUDED IN A HEALTH PLAN’S NETWORK

Also, consider coverage for supportive services, such as doulas, lactation support, and home visiting programs.

MONITOR POPULATION-LEVEL TRENDS AND IDENTIFY OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVEMENT

Utilize data to inform strategies for improving maternal health and support provider participation in quality improvement efforts in states and local communities, such as PQCs. Track trends in quality of care and health care utilization and develop approaches that may reduce identified disparities.

Employers play a key role in establishing norms and expectations around the support of working mothers, including paid family leave and workplace policies.

The postpartum period is a crucial time for women to recover from birth, bond with their new infant(s), and firmly establish breastfeeding practices. Lawmakers have been working to prioritize parental leave for the American people. In 1993, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) 159 was signed into law to provide certain employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave, including after the birth or adoption of a child. 160 FMLA applies to public agencies (local, state, or federal government agencies), public and private elementary and secondary schools, and private-sector employers with 50 or more employees. 161 FMLA covers more than half of the workforce, however, some eligible women may be unable to take this unpaid leave for financial reasons. 161

In December 2019, Congress passed and the President signed into law a major improvement in the compensation and benefits package for the government’s 2.1 million Federal civilian employees as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). 162 The Act provides Federal civilian employees with up to 12 weeks of paid parental leave to care for a new child, whether through birth, adoption, or foster care, beginning in October 2020.

In addition to parental leave, other federal worker protection laws have been enacted, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which ensures that American workers receive a minimum wage. 163 In 2010, the FLSA was amended to require employers to provide reasonable break time and a space for an employee to express breast milk for her nursing child for one year after the child’s birth. 164

Employers have an opportunity to play a key role in supporting women during their pregnancies and in the postpartum period. Due to the recognized health and economic benefits, ACOG endorses paid parental leave, including full benefits and 100% of pay for at least six weeks after delivery. 165 In addition to paid leave 166 in the postpartum period, other family-friendly benefits such as flexible work schedules, preventive medical care, and childcare for sick children may improve recruitment of potential employees and greater retention of current employees.

Employers who offer health insurance are in a position to advocate for comprehensive care coverage to support maternal health. Effective workplace programs and policies can also reduce health risks and improve the quality of life for workers, including women and their families. 167

Overall, there are many strategies that employers can consider that may help to improve maternal health, including those outlined below, however, more research is needed to assess the impact of these actions on maternal health outcomes.

EMPLOYERS CAN

Adopt and support family-friendly policies.

Consider paid family leave 168 and other family-friendly policies, such as flexible work schedules and on-site or easy-to-access high quality childcare. These policies may also help with recruitment and retention of valuable employees. 167

SUPPORT BREASTFEEDING

Provide lactation spaces for breastfeeding mothers, including for those who do not qualify under the FLSA. 166 Consider going beyond what is required in the FLSA 164 (e.g., break time, private rooms) by providing hospitable and welcoming environments, including access to refrigerators, comfortable chairs, sinks and microwaves, for applicable employees.

ENSURE ROBUST MATERNAL CARE THROUGH EMPLOYER-SPONSORED COVERAGE

Negotiate with health insurers on behalf of employees for comprehensive care, including expanding options for receiving care (e.g., telehealth), reducing out-of-pocket costs, and implementing innovative approaches to monitor and manage risk factors (See prior section, “ Payors ”).

DEVELOP A WORKPLACE HEALTH PROGRAM

Develop or adopt workplace programs and policies that promote healthy behaviors, such as ready access to local fitness facilities, healthy vending or cafeteria options, tobacco-free environments and work settings free of environmental threats. Provide worksite blood pressure screening, health education, and lifestyle counseling to help employees control their blood pressure. 169

Innovative approaches across the health care arena can improve maternal health outcomes through policies, technology, systems, products, services, delivery methods, and models of care.

For example, while diabetes educators and nutritionists may already be included in some models of obstetric care, the inclusion of hypertension educators may be an innovative approach to further enhance comprehensive care in the obstetric setting. Technological innovation, such as mobile or computer-based applications, may help to monitor and/or manage women’s health during and beyond pregnancy. This could include mobile applications or monitoring systems that can help to manage conditions, such as diabetes or hypertension. For example, HRSA’s Remote Pregnancy Monitoring Challenge supports innovative-technology-based solutions to help providers remotely monitor the health of pregnant women while empowering these women to monitor their own health and healthcare. 170

Improvements and innovations in EHR technology offer an opportunity for improving maternal health. Interoperability between systems can allow providers to have a more complete view of a woman’s health by incorporating information from various clinical settings and systems. However, the demands of the current EHR systems may take time away from direct patient-provider communication. EHR systems should be improved to ensure they are provider-friendly and valuable to health care professionals. They should also incorporate improvements such as recommended care guidelines and clinical decision support tools, and facilitate linkage of maternal health records with infant health records.

Finally, innovation in delivery methods can address access issues for women who have barriers to care, such as those living in rural or underserved areas, or with limited transportation, or when conditions limit face-to-face interactions. Telehealth innovators can help states and providers identify opportunities for connecting women with a broad range of services to meet their needs. This could include providing remote access to obstetricians, maternal-fetal medicine and other specialists.

Listed below are some topic areas for innovators to consider that may improve maternal health. Innovations should be evaluated to assess their impact on maternal health outcomes.

INNOVATORS CAN

Improve communication between providers and women.

Decrease burden of EHRs on providers to allow more time for communication with patients. Develop mobile applications to facilitate communications during and after pregnancy so that women can conveniently raise issues or concerns to providers and providers can remotely monitor key vital signs. Such applications can focus on various aspects of prenatal and postpartum care and can involve a team of healthcare professionals. Consider developing applications tailored to a variety of cultures, health literacy levels, and racial and ethnic populations and incorporating human-centered design in the development of these applications.

PROMOTE COORDINATION OF CARE ACROSS HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS

Help to address a fragmented system by facilitating communication across different providers using innovative approaches.

DEVELOP AND/OR PARTICIPATE IN NEW MODELS OF MATERNAL CARE

Consider models of care that address maternal health risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, unhealthy weight, substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and IPV, to name a few. For example, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) Model supports the coordination of care and integration of critical health services for pregnant and postpartum Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid use disorder. This, and other innovative payment and delivery models have the potential to improve quality of care for mothers and infants. 171

EXPAND DELIVERY METHODS FOR ACCESSING SPECIALTY CARE

For example, telehealth companies can better meet maternal health needs by designing technology that connects women to needed specialty care providers (e.g., obstetricians, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, pulmonologists, nephrologists, nutritionists, and mental health professionals) and services.

- RESEARCHERS

A critical component of developing solutions and monitoring their impact is the ability to glean information from reliable and comprehensive data; however, there are substantial data limitations and gaps in existing research on maternal health. Further, clinical studies often exclude pregnant women due to an increased risk or concern for adverse outcomes in this population, particularly in research for therapeutic products. Researchers have opportunities to advance this area by adding to the field of evidence on clinical outcomes and by improving the quality of data that are available for analysis.

In clinical arenas, more outcomes-based research would be valuable for understanding the interaction of comorbidities during and after pregnancy and the effectiveness of selected interventions on improving maternal health. More research is needed on disease processes and clinical interventions, protective factors, demographic risk factors, racial disparities, and health system factors. 172

Research is also needed to fill clinical gaps in knowledge related to the defining and treating medical conditions that are known risk factors for maternal mortality, including preeclampsia, cardiovascular disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy, and hemorrhage. 173 , 174 , 175 Research on screening algorithms, risk assessments, and diagnosis involving biomarkers could help to improve timeliness of the identification of women with these conditions and their referral to treatment. 175 , 176 The National Institutes of Health (NIH) supports research addressing many aspects of maternal health.

Evidence has been provided throughout this document for many strategies and actions, however, more research is needed for others, particularly those in the “ Payors ” and “ Employers ” section. Researchers should consider examining those areas, as well as those listed below.

RESEARCHERS CAN

Identify biological, environmental, and social factors that affect maternal health.

Consider analyzing data from NIH’s PregSource®, a crowdsourcing research project designed to improve the understanding of pregnancy by gathering information directly from pregnant women via confidential online questionnaires. 177 The Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS) 178 and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 179 are examples of publicly available data sources that can be used for analysis. The Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) also has data and research-ready files specific to Medicaid and CHIP information. 180

ADVANCE A RESEARCH AGENDA, SUCH AS DISCUSSED IN THE HHS ACTION PLAN 181 , TO IDENTIFY EFFECTIVE, EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL BEST PRACTICES AND HEALTHCARE SYSTEM FACTORS, INCLUDING RESEARCH ON REDUCING DISPARITIES

Conduct research to identify, develop, and rigorously test clinical interventions to address risk factors; identify healthcare factors (e.g., quality of care); and provide insights into healthcare delivery approaches (e.g., care coordination, innovative models of care) for improving access to high-quality maternal health care. Support research to understand, prevent, and reduce adverse maternal health outcomes among racial and ethnic minority women, those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, and those in rural, remote and/or underserved areas. This should include exploring the potential effects of inequities within health systems, processes, and clinical practices on maternal health outcomes.

EXPAND RESEARCH TO DEVELOP SUFFICIENT EVIDENCE ON MEDICATIONS AND TREATMENT

Adopt recommendations made by the HHS Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women (PRGLAC), 182 to increase research for therapeutic products already in use by pregnant or lactating women and for existing therapeutic products not currently licensed for use during pregnancy, but with potential benefit for pregnant women and their infants, and to increase discovery and development of new therapeutic products for these populations.

ENHANCE MATERNAL HEALTH SURVEILLANCE BY IMPROVING THE ACCURACY, QUALITY, CONSISTENCY, SPECIFICITY, TRANSPARENCY, TIMELINESS, AND STANDARDIZATION OF EPIDEMIOLOGICAL DATA ON MATERNAL HEALTH

Improve data quality and timeliness; enhance data and monitoring of racial, ethnic and geographic disparities, and disparities among women with disabilities; and assess strategies to leverage and harmonize national data systems for monitoring maternal health.

Unless otherwise noted in the text, all material appearing in this work is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission. Citation of the source is appreciated.

- Cite this Page Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020 Dec. 4, STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS: IMPROVING MATERNAL HEALTH AND REDUCING MATERNAL MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY.

- PDF version of this title (15M)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General

Recent Activity

- STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS: IMPROVING MATERNAL HEALTH AND REDUCING MATERNAL MORTALIT... STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS: IMPROVING MATERNAL HEALTH AND REDUCING MATERNAL MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY - The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Handbook and Its Effect on Maternal and Child Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

2017, Journal of Community Medicine & Public Health

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 4

National chlorhexidine coverage and factors associated with newborn umbilical cord care in Bangladesh and Nepal: a cross-sectional analysis using household data

Preventable newborn deaths are a global tragedy with many of these deaths concentrated in the first week and day of life. A simple low-cost intervention, chlorhexidine cleansing of the umbilical cord, can prev...

- View Full Text

Racial and ethnic differences in the risk of recurrent preterm or small for gestational age births in the United States: a systematic review and stratified analysis

The risk of recurrent adverse birth outcomes has been reported worldwide, but there are limited estimates of these risks by social subgroups such as race and ethnicity in the United States. We assessed racial ...

Hydrocolpos causing bowel obstruction in a preterm newborn: a case report

Imperforate hymen is the most common congenital defect of the female urogenital tract. The spectrum of clinical manifestations is broad, ranging from mild cases undiagnosed until adolescence to severe cases of...

Neonatal blood pressure by birth weight, gestational age, and postnatal age: a systematic review

Blood pressure is a vital hemodynamic marker during the neonatal period. However, normative values are often derived from small observational studies. Understanding the normative range would help to identify i...

Assessing the agreement of chronic lung disease of prematurity diagnosis between radiologists and clinical criteria

Chronic lung disease of prematurity (CLD) is the most prevalent complication of preterm birth and indicates an increased likelihood of long-term pulmonary complications. The accurate diagnosis of this conditio...

Perinatal dengue and Zika virus cross-sectional seroprevalence and maternal-fetal outcomes among El Salvadoran women presenting for labor-and-delivery

Despite maternal flavivirus infections’ linkage to severe maternal and fetal outcomes, surveillance during pregnancy remains limited globally. Further complicating maternal screening for these potentially tera...

Examination of risk factors for high Edinburgh postnatal depression scale scores: a retrospective study at a single university hospital in Japan

Perinatal mental health, such as postpartum depression, is an important issue that can threaten the lives of women and children. It is essential to understand the risk factors in advance and intervene before t...

Evaluating mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width as predictors of early-onset pre-eclampsia: a prospective cohort study

Platelets are pivotal players in the pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia, with observed lower counts in affected individuals compared to normotensive counterparts. Despite advancements, the elusive cause of pre-e...

Association between social relationship of mentors and depressive symptoms in first-time mothers during the transition from pregnancy to 6-months postpartum

First-time motherhood is characterized by high psychosocial distress, which untreated, has serious consequences. Informal social support provided by specially trained mentors may be protective against postpart...

Dietary supplement use among lactating mothers following different dietary patterns – an online survey

Breastfeeding is important for the healthy growth and development of newborns, and the nutrient composition of human milk can be affected by maternal nutrition and supplementation. In Germany, iodine supplemen...

Unconditional cash transfers for preterm neonates: evidence, policy implications, and next steps for research

To address socioeconomic disparities in the health outcomes of preterm infants, we must move beyond describing these disparities and focus on the development and implementation of interventions that disrupt th...

That head lag is impressive! Infantile botulism in the NICU: a case report

Infantile botulism (IB) is a devastating and potentially life-threatening neuromuscular disorder resulting from intestinal colonization by Clostridium botulinum and the resultant toxin production. It can present ...

Maternal education and its association with maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes in live births conceived using medically assisted reproduction (MAR)

To examine the association between maternal education and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in women who conceived using medically assisted reproduction, which included fertility medications, intrauterine...

The use of projected autonomy in antenatal shared decision-making for periviable neonates: a qualitative study

In this study, we assessed the communication strategies used by neonatologists in antenatal consultations which may influence decision-making when determining whether to provide resuscitation or comfort measur...

Sub-optimal maternal gestational gain is associated with shorter leukocyte telomere length at birth in a predominantly Latinx cohort of newborns

To assess in utero exposures associated with leukocyte telomere length (LTL) at birth and maternal LTL in a primarily Latinx birth cohort.

Maternal and perinatal outcomes of women with vaginal birth after cesarean section compared to repeat cesarean birth in select South Asian and Latin American settings of the global network for women’s and children’s health research

Our objective was to analyze a prospective population-based registry including five sites in four low- and middle-income countries to observe characteristics associated with vaginal birth after cesarean versus...

Expressed breast milk and maternal expression of breast milk for the prevention and treatment of neonatal hypoglycemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Worldwide, many guidelines recommend the use of expressed breast milk (EBM) and maternal expression of breast milk for the prevention and treatment of neonatal hypoglycemia. However, the impact of both practic...

Maternal healthcare use by women with disabilities in Rajasthan, India: a secondary analysis of the Annual Health Survey

Women with disabilities face a number of barriers when accessing reproductive health services, including maternal healthcare. These include physical inaccessibility, high costs, transportation that is not acce...

Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of congenital parvovirus B19 induced anemia - a case report

Parvovirus is a common childhood infection that could be very dangerous to the fetus, if pregnant women become infected. The spectrum of effects range from pure red blood cell aplasia with hydrops fetalis to m...

Benzylpenicillin concentrations in umbilical cord blood and plasma of premature neonates following intrapartum doses for group B streptococcal prophylaxis

Dutch obstetrics guideline suggest an initial maternal benzylpenicillin dose of 2,000,000 IU followed by 1,000,000 IU every 4 h for group-B-streptococci (GBS) prophylaxis. The objective of this study was to ev...

What are the barriers preventing the screening and management of neonatal hypoglycaemia in low-resource settings, and how can they be overcome?

Over 25 years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged the importance of effective prevention, detection and treatment of neonatal hypoglycaemia, and declared it to be a global priority. Neonatal ...

Correction to: Congenital pleuropulmonary blastoma in a newborn with a variant of uncertain significance in DICER1 evaluated by RNA-sequencing

The original article was published in Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology 2023 9 :4

Benefits of maternally-administered infant massage for mothers of hospitalized preterm infants: a scoping review

Infant massage (IM) is a well-studied, safe intervention known to benefit infants born preterm. Less is known about the benefits of maternally-administrated infant massage for mothers of preterm infants who of...

Burden of intestinal parasitic infections and associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis

The ultimate goal of preventing intestinal parasites among pregnant women is to reduce maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. Numerous primary studies were conducted in East Africa presented intestinal ...

Congenital pleuropulmonary blastoma in a newborn with a variant of uncertain significance in DICER1 evaluated by RNA-sequencing

Pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) is a rare mesenchymal malignancy of the lung and is the most common pulmonary malignancy in infants and children. Cystic PPB, the earliest form of PPB occurring from birth to app...

The Correction to this article has been published in Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology 2023 9 :7

Association of maternal nationality with preterm birth and low birth weight rates: analysis of nationwide data in Japan from 2016 to 2020

The rate of low birth weight or preterm birth is known to vary according to the birth place of mothers. However, in Japan, studies that investigated the association between maternal nationalities and adverse b...

Systemic vasculitis diagnosed during the post-partum period: case report and review of the literature

The vasculitis diagnosed specifically in the post-partum period are less well known. We report here such a case followed by a descriptive review of the literature.

Addressing ethical issues related to prenatal diagnostic procedures

For women of advanced maternal age or couples with high risk of genetic mutations, the ability to screen for embryos free of certain genetic mutations is reassuring, as it provides opportunity to address age-r...

Retraction Note: Prevalence and associated factors of early initiation of breastfeeding among women delivered via Cesarean section in South Gondar zone hospitals Ethiopia, 2020

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-020-00121-3.

Non-invasive sensor methods used in monitoring newborn babies after birth, a clinical perspective

Reducing the global new-born mortality is a paramount challenge for humanity. There are approximately 786,323 live births in the UK each year according to the office for National Statistics; around 10% of thes...

Analysis of association between low birth weight and socioeconomic deprivation level in Japan: an ecological study using nationwide municipal data

Several international studies have indicated an association between socioeconomic deprivation levels and adverse birth outcomes. In contrast, those investigating an association between socioeconomic status and...

Case report of congenital methemoglobinemia: an uncommon cause of neonatal cyanosis

Methemoglobinemia can be an acquired or congenital condition. The acquired form occurs from exposure to oxidative agents. Congenital methemoglobinemia is a rare and potentially life-threatening cause of cyanos...

Prenatal exposure to tobacco and adverse birth outcomes: effect modification by folate intake during pregnancy

Fetal exposure to tobacco increases the risk for many adverse birth outcomes, but whether diet mitigates these risks has yet to be explored. Here, we examined whether maternal folate intake (from foods and sup...

Nasolabial and distal limbs dry gangrene in newborn due to hypernatremic dehydration with disseminated intravascular coagulation: a case report

Gangrene is the death of an organ or tissue due to lack of blood supply or bacterial infection. In neonates, gangrene is usually caused by sepsis, dehydration, maternal diabetes, asphyxia, or congenital antico...

Evidence based recommendations for an optimal prenatal supplement for women in the US: vitamins and related nutrients

The blood levels of most vitamins decrease during pregnancy if un-supplemented, including vitamins A, C, D, K, B1, B3, B5, B6, folate, biotin, and B12. Sub-optimal intake of vitamins from preconception through...

Effects of inter-pregnancy intervals on preterm birth, low birth weight and perinatal deaths in urban South Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study

Preterm birth, low birth weight and perinatal deaths are common adverse perinatal outcomes that are linked with each other, and a public health problems contributing to neonatal mortality, especially in develo...

Prematurity and low birth weight: geospatial analysis and recent trends

Prematurity and low birth weight are of concern in neonatal health. In this work, geospatial analysis was performed to identify the existence of statistically significant clusters of prematurity and low birth ...

CNS Malformations in the Newborn

Structural brain anomalies are relatively common and may be detected either prenatally or postnatally. Brain malformations can be characterized based on the developmental processes that have been perturbed, ei...

Outcomes of multiple gestation births compared to singleton: analysis of multicenter KID database

The available data regarding morbidity and mortality associated with multiple gestation births is conflicting and contradicting.

Outcomes of neonatal hypothermia among very low birth weight infants: a Meta-analysis

Neonatal admission hypothermia (HT) is a frequently encountered problem in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and it has been linked to a higher risk of mortality and morbidity. However, there is a disparit...

Incidence and determinants of perinatal mortality among women with obstructed labour in eastern Uganda: a prospective cohort study

In Uganda, the incidence and determinants of perinatal death in obstructed labour are not well documented. We determined the incidence and determinants of perinatal mortality among women with obstructed labour...

The risk of diabetes after giving birth to a macrosomic infant: data from the NHANES cohort

Gestational diabetes (GDM) increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and thus warrants earlier and more frequent screening. Women who give birth to a macrosomic infant, as defined as a birthweight great...

Methods for exploring the faecal microbiome of premature infants: a review

The premature infant gut microbiome plays an important part in infant health and development, and recognition of the implications of microbial dysbiosis in premature infants has prompted significant research i...

Determinants of stillbirths among women who gave birth at Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital, Hawassa, Sidama, Ethiopia 2019: a case-control study

Globally over 2.6 million pregnancy ends with stillbirth annually. Despite this fact, only a few sherds of evidence were available about factors associated with stillbirth in Ethiopia. Therefore, the study aim...

Traditional medicine utilisation and maternal complications during antenatal care among women in Bulilima, Plumtree, Zimbabwe

As part of the expectation enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals, countries are expected to ensure maternal health outcomes are improved. It follows that under ideal circumstances, pregnant women shou...

Prevalence of rhesus D-negative blood type and the challenges of rhesus D immunoprophylaxis among obstetric population in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Transplacental or fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH) may occur during pregnancy or at delivery and lead to immunization to the D antigen if the mother is Rh-negative and the baby is Rh-positive. This can result in ...

Antibiotic exposure and growth patterns in preterm, very low birth weight infants

Antibiotic exposure in term infants has been associated with later obesity. Premature, very-low-birth-weight (birth weight ≤ 1500 g) infants in the neonatal intensive care unit frequently are exposed to antibi...

A case study of the first pregnant woman with COVID-19 in Bukavu, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo

Vertical transmission of covid-19 is possible; its risk factors are worth researching. The placental changes found in pregnant women have a definite impact on the foetus.

Effects of timing of umbilical cord clamping on preventing early infancy anemia in low-risk Japanese term infants with planned breastfeeding: a randomized controlled trial

Japanese infants have relatively higher risk of anemia and neonatal jaundice. This study aimed to assess the effects of delayed cord clamping (DCC) on the incidence of anemia during early infancy in low-risk J...

Case report: necrotizing enterocolitis with a transverse colonic perforation in a 2-day old term neonate and literature review

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), while classically discussed in preterm and low birth weight neonates, also occurs in the term infant and accounts for 10% of all NEC cases. Despite there being fewer reported c...

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

Annual Journal Metrics

2023 Speed 11 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 111 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 303,952 downloads 71 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology

ISSN: 2054-958X

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2024

Key barriers to the provision and utilization of maternal health services in low-and lower-middle-income countries; a scoping review

- Yaser Sarikhani 1 ,

- Seyede Maryam Najibi 2 &

- Zahra Razavi 1

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 325 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

61 Accesses

Metrics details

The preservation and promotion of maternal health (MH) emerge as vital global health objectives. Despite the considerable emphasis on MH, there are still serious challenges to equitable access to MH services in many countries. This review aimed to determine key barriers to the provision and utilization of MH services in low- and lower-middle-income countries (LLMICs).

In this scoping review, we comprehensively searched four online databases from January 2000 to September 2022. In this study, the approach proposed by Arksey and O’Malley was used to perform the review. Consequently, 117 studies were selected for final analysis. To determine eligibility, three criteria of scoping reviews (population, concept, and context) were assessed alongside the fulfillment of the STROBE and CASP checklist criteria. To synthesize and analyze the extracted data we used the qualitative content analysis method.

The main challenges in the utilization of MH services in LLMICs are explained under four main themes including, knowledge barriers, barriers related to beliefs, attitudes and preferences, access barriers, and barriers related to family structure and power. Furthermore, the main barriers to the provision of MH services in these countries have been categorized into three main themes including, resource, equipment, and capital constraints, human resource barriers, and process defects in the provision of services.

Conclusions

The evidence from this study suggests that many of the barriers to the provision and utilization of MH services in LLMICs are interrelated. Therefore, in the first step, it is necessary to prioritize these factors by determining their relative importance according to the specific conditions of each country. Consequently, comprehensive policies should be developed using system modeling approaches.

Peer Review reports

Maternal care encompasses a series of interventions aimed at mitigating the effects of risk factors, managing illnesses, and ultimately safeguarding the well-being of both women and children. Maternal health (MH) services are concerned with maintaining the health of women before and during pregnancy, during childbirth, and in the postnatal period. Maternal care, which involves a broad spectrum of services including screening, early disease detection, prompt treatment, and health education, plays a vital role in decreasing mortality rates and improving women’s health outcomes [ 1 ]. Despite the advancements in medical science and the provision of guidelines and operational instructions, health policymakers have consistently prioritized the maintenance and improvement of MH. This concern is especially prominent in low-income countries, where addressing the issue remains a top priority [ 2 ]. The significance of maternal mortality extends beyond being a mere indicator of poor health conditions; it also represents a formidable challenge for healthcare systems [ 3 ].

Annually, over 500,000 women across the globe lose their lives due to pregnancy and childbirth-related complications. It is noteworthy that developing countries experience an alarming 99% of maternal deaths, underscoring the pressing need for targeted interventions to address this issue [ 4 ]. Despite the particular focus on MH, the maternal mortality rate in 2019 was 145 per 100,000 live births worldwide. Meanwhile, in developing countries, this ratio is estimated at 276 deaths for every 100,000 live births [ 5 ]. Studies also show that maternal mortality decreased from 11.2 to 5.01 per 100,000 population worldwide between 1999 and 2019. In low-income countries, this index fell from 43.31 to 21.10. Moreover, from 1999 to 2019, the rate of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in the 100,000 population due to maternal disorders decreased from 695 to 394 globally and from 2,536 to 1,262 in low-income countries [ 6 ]. Consequently, even though the global maternal mortality rates are decreasing, there remains a substantial disparity between the average global rates and those observed in low-income countries. This emphasizes the critical need to prioritize MH services in numerous nations.

According to available reports, the main direct factors associated with maternal death and injury are heavy bleeding, infections, hypertension, and unsafe abortion, while the main indirect causes are anemia, malaria, and heart disease [ 4 ]. Meanwhile, the goal of maternal care standards is to improve access to effective services, make the efficient use of available resources to achieve desired outcomes, help healthcare providers improve the quality of services, improve people’s satisfaction, and promote the use of services [ 7 ]. Nonetheless, even with the considerable attention given to maternal care, numerous obstacles hinder the successful implementation of maternal care programs. These challenges are present at both the level of mothers as recipients of services and the level of service providers. Numerous research from different parts of the world have investigated the barriers to accessing MH care services. In 2020, Shibata et al. showed that prenatal care utilization was significantly associated with geographic location, household income, and education level [ 8 ]. Transportation to access health facilities [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], high cost of services [ 12 , 13 ], and lack of competence of health professionals [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] were also among the barriers mentioned in different studies.

Effective MH care is vital for reaching the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this context, adopting comprehensive strategies is essential for the provision of suitable MH services and the reduction of maternal mortality rates globally [ 14 ]. Identifying key obstacles to the provision and utilization of MH services can provide policymakers with insights to develop the necessary strategies to address and overcome these obstacles. In light of this matter, it is feasible to provide communities with timely and high-quality services to address the pressing challenges of reducing maternal mortality. This is especially vital for low-income countries [ 15 ], as it can substantially contribute to the improvement of public health. Therefore, this study aims to determine the main barriers to the provision and utilization of MH services in low- and lower-middle-income countries (LLMICs), using a scoping review approach.

We used a scoping review method to identify barriers to the provision and utilization of MH services. A comprehensive review was conducted, resulting in the creation of an evidence map associated with the topic. The provision of mental health services is largely determined by the socioeconomic conditions of communities. Therefore, this study investigated these factors in LLMICs to leverage the findings for policy interventions in countries with similar contexts. The classification of countries is based on the information provided by the World Bank. Countries with a gross national income (GNI) per capita of less than US$1,045 were classified as low-income countries using the Atlas method. Additionally, countries where the above index ranged from $1046 to $4095 were classified as lower-middle-income countries [ 16 ].

A scoping review is used in this study because this type of review provides the possibility of involving studies with different designs and sampling methods [ 17 ]. This type of research also allows for the identification of key components of a topic to provide a map of evidence and reveal the research gap in the considered area [ 18 ]. In this study, the approach proposed by Arksey and O’Malley was used to perform a scoping review. This approach involves five separate steps: 1- determining the research question, 2- finding and extracting studies, 3- selecting relevant studies, 4- tabulating data, and 5- summarizing information, analyzing themes, and presenting results [ 17 ].

Determining the research question

The scope and extent of a review study is usually determined by the research question. However, because scoping research has a continuous and iterative process of searching, selecting articles, and modifying the research question, the research question of this review study was finalized during the study process. In this study, barriers to the provision and utilization of MH services in LLMICs were considered as the expected result. This research was conducted to answer the question: “What are the main barriers to the provision and utilization of MH services in LLMICs?”

Finding and extracting studies