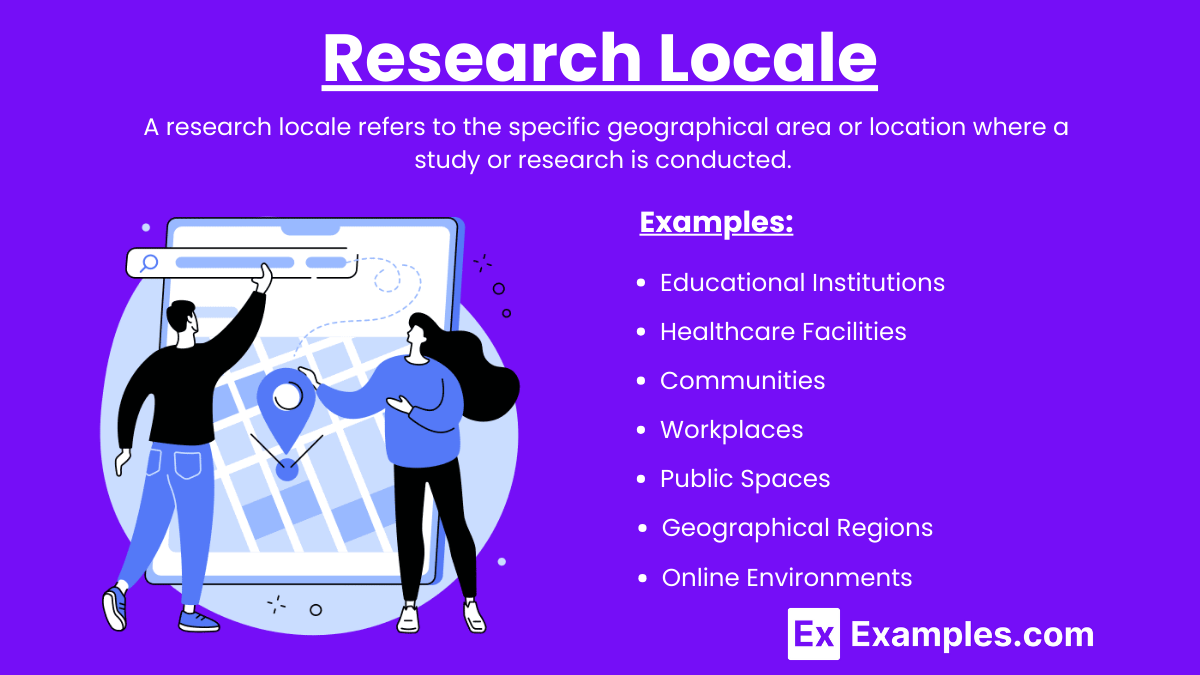

Research Locale

Ai generator.

A research locale refers to the specific geographical area or location where a study or research is conducted. This locale is carefully chosen based on the study’s objectives, the population of interest, and the relevance of the location to the research questions. Selecting an appropriate research locale is crucial as it impacts the validity and generalizability of the study’s findings. The locale provides the context within which data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted, making it a fundamental aspect of the research action plan . In studies focusing on environmental or biological aspects, understanding the endemic species within the research locale is essential, as these species are native to the area and can significantly influence the research outcomes.

What is Research Locale?

Research locale refers to the specific geographical location or setting where a study is conducted. This area is chosen based on the objectives and requirements of the research, as it provides the necessary context and environment for gathering relevant data. The research locale can range from a small community or institution to a larger region or multiple sites, depending on the scope of the study.

Examples of Research Locale

- Schools: Conducting a study on the effectiveness of a new teaching method in elementary, middle, or high schools.

- Universities: Researching student behaviors, learning outcomes, or the impact of specific academic programs in higher education settings.

- Hospitals: Investigating patient recovery rates or the efficacy of new treatments in a hospital setting.

- Clinics: Studying the accessibility and quality of healthcare services in local clinics.

- Urban Areas: Examining the effects of urbanization on residents’ quality of life, health, or social interactions.

- Rural Areas: Researching agricultural practices, rural healthcare accessibility, or educational challenges in rural settings.

- Corporations: Studying employee satisfaction, productivity, or the impact of corporate policies in large companies.

- Small Businesses: Investigating the challenges and successes of small business operations in local communities.

- Parks: Researching the usage patterns and benefits of public parks for community health and well-being.

- Libraries: Examining the role of public libraries in community education and engagement.

- Countries: Conducting cross-national studies on economic development, public health, or educational systems.

- Regions: Researching environmental impacts, cultural practices, or regional policies in specific areas such as the Midwest, the Himalayas, or the Amazon Basin.

- Social Media Platforms: Studying user behavior, misinformation spread, or social interactions on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.

- Virtual Communities: Investigating the dynamics of online forums, gaming communities, or e-learning environments.

Research Locale Examples in School

- Classroom Dynamics: Investigating how seating arrangements affect student interaction and participation in a third-grade classroom.

- Reading Programs: Assessing the impact of a new phonics-based reading program on literacy rates among first graders.

- Bullying Prevention: Studying the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs and policies in reducing incidents of bullying among sixth to eighth graders.

- STEM Education: Evaluating the success of extracurricular STEM clubs in improving students’ interest and performance in science and math subjects.

- College Preparation: Analyzing how different college preparatory programs influence the readiness and success of students applying to universities.

- Sports Participation: Researching the correlation between participation in high school sports and academic performance, self-esteem, and social skills.

- Inclusive Practices: Investigating the effectiveness of inclusive education practices on the social integration and academic achievements of students with special needs.

- Assistive Technologies: Evaluating the impact of various assistive technologies on the learning outcomes of students with disabilities.

- Curriculum Impact: Assessing the impact of specialized curricula (e.g., arts, sciences, or technology-focused) on student engagement and academic performance.

- Student Diversity: Studying the effects of a diverse student body on cultural awareness and interpersonal skills among students.

- Innovative Teaching Methods: Examining the outcomes of innovative teaching methods and curricula implemented in charter schools compared to traditional public schools.

- Parental Involvement: Researching how parental involvement in charter schools affects student motivation and achievement.

- Residential Life: Investigating the effects of boarding school environments on student independence, social development, and academic performance.

- Extracurricular Activities: Studying the role of extracurricular activities in shaping the overall development and well-being of boarding school students.

- Multicultural Education: Examining the impact of multicultural education programs on students’ global awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity.

- Language Acquisition: Researching the effectiveness of bilingual education programs in international schools on students’ proficiency in multiple languages.

Examples of Research Locale Quantitative

- Measuring the effect of a new math curriculum on standardized test scores among fourth-grade students.

- Analyzing the relationship between breakfast programs and student attendance rates.

- Quantifying the impact of restorative justice practices on the frequency of disciplinary actions.

- Assessing the correlation between educational technology use in classrooms and student achievement in science.

- Investigating factors influencing graduation rates, including socio-economic status and teacher-student ratios.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of college preparatory programs by comparing college admission rates of participants versus non-participants.

- Measuring the progress of students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) in academic performance and behavioral improvements.

- Quantifying the impact of different assistive technologies on academic success.

- Comparing academic performance data between students in magnet schools and traditional public schools.

- Analyzing enrollment data to determine the diversity of student populations and its impact on academic outcomes.

- Assessing academic outcomes by comparing standardized test scores between charter school students and traditional public school students.

- Measuring teacher retention rates in charter schools versus public schools.

- Quantifying academic performance by analyzing GPA and standardized test scores of boarding school students.

- Conducting surveys to collect quantitative data on student well-being and correlating it with academic success.

- Measuring language proficiency levels in bilingual programs using standardized language tests.

- Using surveys to quantify students’ cultural competence and its relationship with academic performance.

Examples of Research Locale Qualitative

- Classroom Interaction: Observing and documenting student-teacher interactions to understand the dynamics of effective teaching strategies.

- Playground Behavior: Conducting interviews and focus groups with students to explore their social interactions and conflict resolution methods during recess.

- Peer Relationships: Exploring the nature of peer relationships and their impact on students’ emotional well-being through in-depth interviews.

- Curriculum Implementation: Gathering teacher narratives on the challenges and successes of implementing a new curriculum.

- Extracurricular Activities: Investigating students’ experiences and perceptions of participating in extracurricular activities through case studies and interviews.

- Career Aspirations: Conducting focus groups to understand how students’ backgrounds and school experiences shape their career aspirations.

- Parent Perspectives: Interviewing parents of students with special needs to gather insights into their experiences and satisfaction with the educational services provided.

- Teacher Experiences: Collecting narratives from special education teachers about their experiences, challenges, and strategies in teaching students with diverse needs.

- Student Motivation: Exploring the factors that motivate students to attend and succeed in magnet schools through in-depth interviews.

- Cultural Integration: Studying how students from diverse backgrounds integrate and interact within the specialized environment of magnet schools.

- Teacher Retention: Investigating the reasons behind teacher retention and turnover in charter schools through qualitative interviews with current and former teachers.

- Parent Involvement: Conducting case studies to understand the role and impact of parent involvement in charter school communities.

- Residential Life: Exploring students’ experiences of residential life, focusing on their personal growth and social development through narrative inquiry.

- Alumni Perspectives: Interviewing alumni to gather insights on how their boarding school experience has influenced their post-graduation life.

- Cultural Adaptation: Examining the experiences of expatriate students adapting to new cultural environments through ethnographic studies.

- Multilingual Education: Conducting interviews with teachers and students to explore the challenges and benefits of multilingual education in international schools.

Research locale Sample Paragraph

This study was conducted in three public high schools located in the urban district of Greenville, North Carolina. The selected schools—Greenville High School, Central High School, and Riverside High School—were chosen for their diverse student populations and varying levels of technological integration in the classroom. Each school enrolls approximately 1,200 students, offering a mix of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, vocational training, and special education programs. Greenville High School recently implemented a 1:1 laptop initiative, providing each student with a personal device for educational use. Central High School utilizes a blended learning model with shared computer labs and mobile tablet carts, while Riverside High School maintains a more traditional approach with limited use of digital tools. This study focuses on 11th-grade students enrolled in English and Mathematics courses, examining how different levels of technology integration impact student engagement and academic performance. Data was collected through a combination of student surveys, standardized test scores, classroom observations, and interviews with teachers and administrators, aiming to provide comprehensive insights into the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning environments.

How to write Research Locale?

The research locale section of your study provides a detailed description of the location where the research will be conducted. This section is crucial for contextualizing your research and helping readers understand the setting and its potential influence on your study. Here are the steps to write an effective research locale:

1. Introduction to the Locale

- Name and Description : Start by naming the locale and providing a brief description. Include geographic, demographic, and cultural aspects.

- Relevance : Explain why this locale is suitable for your study.

2. Geographic Details

- Location : Provide precise details about the location, including the city, state, country, and any specific areas within these larger regions.

- Map and Boundaries : If possible, include a map to illustrate the locale and its boundaries.

3. Demographic Information

- Population : Describe the population size, density, and composition. Include information on age, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic status.

- Community Characteristics : Mention any unique characteristics of the community that are relevant to your study.

4. Socio-Economic and Cultural Context

- Economic Activities : Outline the primary economic activities and employment sectors in the locale.

- Cultural Practices : Highlight cultural practices, traditions, and values that might influence the study.

5. Educational and Institutional Context

- Schools and Institutions : If relevant, describe the educational institutions, such as schools or universities, and their role in the community.

- Other Institutions : Mention any other institutions (e.g., healthcare, religious) that might be relevant.

6. Accessibility and Infrastructure

- Transportation : Explain the transportation infrastructure, including roads, public transit, and accessibility.

- Facilities : Mention key facilities like hospitals, libraries, and recreational centers.

7. Environmental Factors

- Climate and Geography : Describe the climate and any geographic features that could impact your research.

- Environmental Conditions : Note any environmental conditions, such as pollution or natural resources, relevant to your study.

FAQ’s

Why is the research locale important.

The research locale is crucial because it influences the study’s context, data collection, and findings’ applicability.

How do you select a research locale?

Selection involves considering relevance to the research question, accessibility, availability of data, and potential impact on results.

What factors influence the choice of a research locale?

Factors include geographical location, demographic characteristics, cultural context, and logistical feasibility.

Can a study have multiple research locales?

Yes, studies can include multiple locales to compare different environments or enhance the study’s generalizability.

How does the research locale affect data collection?

The locale can determine the methods used, participant availability, and types of data collected.

What is the difference between research locale and research setting?

The research locale is the broader geographical area, while the research setting refers to the specific place within that locale.

How do you describe a research locale in a study?

Include geographical details, demographic information, cultural characteristics, and any relevant historical or social context.

Why might a researcher choose an urban research locale?

Urban locales offer diverse populations, accessible resources, and varied social dynamics.

Why might a researcher choose a rural research locale?

Rural locales provide unique insights into less-studied populations, community dynamics, and environmental factors.

What role does the research locale play in qualitative research?

In qualitative research, the locale is integral to understanding participants’ lived experiences and contextual factors.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Chapter III METHODOLOGY Research Locale

Related Papers

Amanda Hunn

Petra Boynton

Journal of Chemical Education

Diane M Bunce

André Pereira

Satyajit Behera

Measurement and Data Collection. Primary data, Secondary data, Design of questionnaire ; Sampling fundamentals and sample designs. Measurement and Scaling Techniques, Data Processing

Roberto Jr. P Tacbobo

International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

Reuben Bihu

Questionnaire surveys dominate the methodological designs in educational and social studies, particularly in developing countries. It is conceived practically easy to adopt study protocols under the design, and off course most researchers would prefer using questionnaire survey studies designed in most simple ways. Such studies provide the most economical way of gathering information from representations giving data that apply to general populations. As such, the desire for cost management and redeeming time have caused many researchers to adapt, adopt and apply the designs, even where it doesn’t qualify for the study contexts. Consequently, they are confronted by managing consistent errors and mismatching study protocols and methodologies. However, the benefits of using the design are real and popular even to the novice researchers and the problems arising from the design are always easily address by experienced researchers

Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanità

Chiara de Waure

This article describes methodological issues of the "Sportello Salute Giovani" project ("Youth Health Information Desk"), a multicenter study aimed at assessing the health status and attitudes and behaviours of university students in Italy. The questionnaire used to carry out the study was adapted from the Italian health behaviours in school-aged children (HBSC) project and consisted of 93 items addressing: demographics; nutritional habits and status; physical activity; lifestyles; reproductive and preconception health; health and satisfaction of life; attitudes and behaviours toward academic study and new technologies. The questionnaire was administered to a pool of 12 000 students from 18 to 30 years of age who voluntary decided to participate during classes held at different Italian faculties or at the three "Sportello Salute Giovani" centers which were established in the three sites of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Catholic University of...

Trisha Greenhalgh

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Ebenezer Consultan

RENA MAHINAY LIHAYLIHAY

Rena LihayLihay

Daniela Garcia

De Wet Schutte

International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Sciences (IJMTS)

Srinivas Publication , Sreeramana Aithal

Carrie Bretz

Assessing Governance Matrices in Co-Operative Financial Institutions (CFI's)

Ivan Steenkamp

Sallie Newell

Burcu Akhun

Medical Teacher

Anthony Artino

João Bandeira De Melo Papelo

Nipuni Rangika

DGeanene White

Abla BENBELLAL

Saleha Habibullah

Indian Journal of Anaesthesia

Narayana Yaddanapudi

Student BMJ

Mitra Amini

Maribel Peró Cebollero

Dolores Frias-Navarro

Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care

Gill Wakley

Godwill Medukenya

Edrine Wanyama

Cut Eka Para Samya

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

New York City Neighborhood Research: Locale

- How To Site See

- Local History

- Building Research

- Demographic

- NYPL Research Guides

- What Changed?

- Patterns, Connections, Associations

In approaching a locale for research, there are a number of questions to ask first, as triggers, to get yourself situated, and to inhabit the modes and thinking of a researcher. Each tab in this section covers the types of questions it will help to ask in getting started.

What is there? Make a list of notable locales in the area: monuments, parks, department stores, factories, museums, bars, schools, office buildings, diners. These things are what give a neighborhood its physical, behavioral, and historical character.

What does it look like? What did it look like? At the reference desk, images are one of the most sought after resources in neighborhood research. Photographs might communicate extra dimensions of an area that are not conveyed through nonvisual materials. They also provide a vivid sense of immediacy to the past, as if crossing through the wormhole. Images of the built environment and street life enable a more intimate and possibly more profound understanding of a place.

At the other end of the spectrum - take a look at what is still there, even after all those years. The Bridge Cafe at 279 Water Street is sadly no longer in operation, but the building itself supposedly dates to 1794 , and still appears as if behind the upstairs windows live oystermen and sailmakers. Or, sure, Times Square has been the entertainment district for over 100 years, but the changes in the neighborhood surpass the size of crowds on New Years Eve.

Also, the tour was simply the narrative form: this idea applies to whatever form your research ultimately takes (article, book, exhibit, etc.).

Another pattern might be statues - the statues themselves are the pattern, the art form and mode of representation - which then serves the opportunity to note connections or associations between whatever they may represent.

Patterns, connections, and associations are there. Find them.

- << Previous: How To Site See

- Next: Subject >>

- Last Updated: Jun 22, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.nypl.org/neighborhoodresearch

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 12: Field Research: A Qualitative Research Technique

12.4 Getting In and Choosing a Site

When embarking on a field research project, there are two major aspects to consider. The first is where to observe and the second is what role you will take in your field site. Your decision about each of these will be shaped by a number of factors, over some of which you will have control and others you will not. Your decision about where to observe and what role to play will also have consequences for the data you are able to gather and how you analyze and share those data with others. We will examine each of these contingencies in the following subsections.

Your research question might determine where you observe, by, but because field research often works inductively, you may not have a totally focused question before you begin your observations. In some cases, field researchers choose their final research question once they embark on data collection. Other times, they begin with a research question but remain open to the possibility that their focus may shift as they gather data. In either case, when you choose a site, there are a number of factors to consider. These questions include:

- What do you hope to accomplish with your field research?

- What is your topical/substantive interest?

- Where are you likely to observe behaviour that has something to do with that topic?

- How likely is it that you will actually have access to the locations that are of interest to you?

- How much time do you have to conduct your participant observations?

- Will your participant observations be limited to a single location, or will you observe in multiple locations?

Perhaps the best place to start, as you work to identify a site or sites for your field research, is to think about your limitations . One limitation that could shape where you conduct participant observation is time. Field researchers typically immerse themselves in their research sites for many months, sometimes even years. As demonstrated in Table 12.1 “Field Research Examples”, other field researchers have spent as much or even more time in the field. Do you have several years available to conduct research, or are you seeking a smaller-scale field research experience? How much time do you have to participate and observe per day? Per week? Identifying how available you’ll be in terms of time will help you determine where and what sort of research sites to choose. Also think about where you live and whether travel is an option for you. Some field researchers move to live with or near their population of interest. Is this something you might consider? How you answer these questions will shape how you identify your research site. Where might your field research questions take you?

In choosing a site, also consider how your social location might limit what or where you can study. The ascribed aspects of our locations are those that are involuntary, such as our age or race or mobility. For example, how might your ascribed status as an adult shape your ability to conduct complete participation in a study of children’s birthday parties? The achieved aspects of our locations, on the other hand, are those about which we have some choice. In field research, we may also have some choice about whether, or the extent to which, we reveal the achieved aspects of our identities.

Finally, in choosing a research site, consider whether your research will be a collaborative project or whether you are on your own. Collaborating with others has many benefits; you can cover more ground, and therefore collect more data, than you can on your own. Having collaborators in any research project, but especially field research, means having others with whom to share your trials and tribulations in the field. However, collaborative research comes with its own set of challenges, such as possible personality conflicts among researchers, competing commitments in terms of time and contributions to the project, and differences in methodological or theoretical perspectives (Shaffir, Marshall, & Haas, 1979). When considering something that is of interest to you, consider also whether you have possible collaborators. How might having collaborators shape the decisions you make about where to conduct participant observation?

This section began by asking you to think about limitations that might shape your field site decisions. But it makes sense to also think about the opportunities —social, geographic, and otherwise—that your location affords. Perhaps you are already a member of an organization where you would like to conduct research. Maybe you know someone who knows someone else who might be able to help you access a site. Perhaps you have a friend you could stay with, enabling you to conduct participant observations away from home. Choosing a site for participation is shaped by all these factors—your research question and area of interest, a few limitations, some opportunities, and sometimes a bit of being in the right place at the right time.

Choosing a Role

As with choosing a research site, some limitations and opportunities beyond your control might shape the role you take once you begin your participant observation. You will also need to make some deliberate decisions about how you enter the field and who you will be once you are in.

In terms of entering the field, one of the earliest decisions you will need to make is whether to be overt or covert. As an overt researcher, you enter the field with your research participants having some awareness about the fact that they are the subjects of social scientific research. Covert researchers, on the other hand, enter the field as though they are full participants, opting not to reveal that they are also researchers or that the group they’ve joined is being studied. As you might imagine, there are pros and cons to both approaches. A critical point to keep in mind is that whatever decision you make about how you enter the field will affect many of your subsequent experiences in the field.

As an overt researcher, you may experience some trouble establishing rapport at first. Having an insider at the site who can vouch for you will certainly help, but the knowledge that subjects are being watched will inevitably (and understandably) make some people uncomfortable and possibly cause them to behave differently than they would, were they not aware of being research subjects. Because field research is typically a sustained activity that occurs over several months or years, it is likely that participants will become more comfortable with your presence over time. Overt researchers also avoid a variety of moral and ethical dilemmas that they might otherwise face.

As a covert researcher, “getting in” your site might be quite easy; however, once you are in, you may face other issues. Some questions to consider are:

- How long would you plan to conceal your identity?

- How might participants respond once they discover you’ve been studying them?

- How will you respond if asked to engage in activities you find unsettling or unsafe?

Researcher, Jun Li (2008) struggled with the ethical challenges of “getting in” to interview female gamblers as a covert researcher. Her research was part of a post-doctoral fellowship from the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre to study female gambling culture. In response to these ethical aspects, she changed her research role to overt; however, in her overt role female gamblers were reluctant to “speak their minds” to her (p. 100). As such, she once again adjusted her level of involvement in the study to one who participated in female gambling culture as an insider and observed as an outsider. You can read her interesting story .

Beyond your own personal level of comfort with deceiving participants and willingness to take risks, it is possible that the decision about whether or not to enter the field covertly will be made for you. If you are conducting research while associated with any federally funded agency (and even many private entities), your institutional review board (IRB) probably will have something to say about any planned deception of research subjects. Some IRBs approve deception, but others look warily upon a field researcher engaging in covert participation. The extent to which your research site is a public location, where people may not have an expectation of privacy, might also play a role in helping you decide whether covert research is a reasonable approach.

Having an insider at your site who can vouch for you is helpful. Such insiders, with whom a researcher may have some prior connection or a closer relationship than with other site participants, are called key informants. A key informant can provide a framework for your observations, help translate what you observe, and give you important insight into a group’s culture. If possible, having more than one key informant at a site is ideal, as one informant’s perspective may vary from another’s.

Once you have made a decision about how to enter your field site, you will need to think about the role you will adopt while there. Aside from being overt or covert, how close will you be to participants? In the words of Fred Davis (1973), [12] who coined these terms in reference to researchers’ roles, “will you be a Martian, a Convert, or a bit of both”? Davis describes the Martian role as one in which a field researcher stands back a bit, not fully immersed in the lives of his subjects, in order to better problematize, categorize, and see with the eyes of a newcomer what’s being observed. From the Martian perspective, a researcher should remain disentangled from too much engagement with participants. The Convert, on the other hand, intentionally dives right into life as a participant. From this perspective, it is through total immersion that understanding is gained. Which approach do you feel best suits you?

In the preceding section we examined how ascribed and achieved statuses might shape how or which sites are chosen for field research. They also shape the role the researcher adopts in the field site. The fact that the authors of this textbook are professors, for example, is an achieved status. We can choose the extent to which we share this aspect of our identities with field study participants. In some situations, sharing that we are professors may enhance our ability to establish rapport; in other field sites it might stifle conversation and rapport-building. As you have seen from the examples provided throughout this chapter, different field researchers have taken different approaches when it comes to using their social locations to help establish rapport and dealing with ascribed statuses that differ from those of their “subjects

Whatever role a researcher chooses, many of the points made in Chapter 11 “Quantitative Interview Techniques” regarding power and relationships with participants apply to field research as well. In fact, the researcher/researched relationship is even more complex in field studies, where interactions with participants last far longer than the hour or two it might take to interview someone. Moreover, the potential for exploitation on the part of the researcher is even greater in field studies, since relationships are usually closer and lines between research and personal or off-the-record interaction may be blurred. These precautions should be seriously considered before deciding to embark upon a field research project

Field Notes

The aim with field notes is to record your observations as straightforwardly and, while in the field, as quickly as possible, in a way that makes sense to you . Field notes are the first—and a necessary—step toward developing quality analysis. They are also the record that affirms what you observed. In other words, field notes are not to be taken lightly or overlooked as unimportant; however, they are not usually intended for anything other than the researcher’s own purposes as they relate to recollections of people, places and things related to the research project.

Some say that there are two different kinds of field notes: descriptive and analytic. Though the lines between what counts as description and what counts as analysis can become blurred, the distinction is nevertheless useful when thinking about how to write and how to interpret field notes. In this section, we will focus on descriptive field notes. Descriptive field notes are notes that simply describe a field researcher’s observations as straightforwardly as possible. These notes typically do not contain explanations of, or comments about, those observations. Instead, the observations are presented on their own, as clearly as possible. In the following section, we will define and examine the uses and writing of analytic field notes more closely.

Analysis of Field Research Data

Field notes are data. But moving from having pages of data to presenting findings from a field study in a way that will make sense to others requires that those data be analyzed. Analysis of field research data is the focus in this final section of the chapter.

From Description to Analysis

Writing and analyzing field notes involves moving from description to analysis. In Section 12.4 “Field Notes”, we considered field notes that are mostly descriptive in nature. In this section we will consider analytic field notes. Analytic field notes are notes that include the researcher’s impressions about his observations. Analyzing field note data is a process that occurs over time, beginning at the moment a field researcher enters the field and continuing as interactions happen in the field, as the researcher writes up descriptive notes, and as the researcher considers what those interactions and descriptive notes mean.

Often field notes will develop from a more descriptive state to an analytic state when the field researcher exits a given observation period, with messy jotted notes or recordings in hand (or in some cases, literally on hand), and sits at a computer to type up those notes into a more readable format. We have already noted that carefully paying attention while in the field is important; so is what goes on immediately upon exiting the field. Field researchers typically spend several hours typing up field notes after each observation has occurred. This is often where the analysis of field research data begins. Having time outside of the field to reflect upon your thoughts about what you have seen and the meaning of those observations is crucial to developing analysis in field research studies.

Once the analytic field notes have been written or typed up, the field researcher can begin to look for patterns across the notes by coding the data. This will involve the iterative process of open and focused coding that is outlined in Chapter 10, “Qualitative Data Collection & Analysis Methods.” As mentioned in Section 12.4 “Field Notes”, it is important to note as much as you possibly can while in the field and as much as you can recall after leaving the field because you never know what might become important. Things that seem decidedly unimportant at the time may later reveal themselves to have some relevance.

As mentioned in Chapter 10, analysis of qualitative data often works inductively. The analytic process of field researchers and others who conduct inductive analysis is referred to as grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2006). The goal when employing a grounded theory approach is to generate theory. Its name not only implies that discoveries are made from the ground up but also that theoretical developments are grounded in a researcher’s empirical observations and a group’s tangible experiences. Grounded theory requires that one begin with an open-ended and open-minded desire to understand a social situation or setting and involves a systematic process whereby the researcher lets the data guide her rather than guiding the data by preset hypotheses.

As exciting as it might sound to generate theory from the ground up, the experience can also be quite intimidating and anxiety-producing, since the open nature of the process can sometimes feel a little out of control. Without hypotheses to guide their analysis, researchers engaged in grounded theory work may experience some feelings of frustration or angst. The good news is that the process of developing a coherent theory that is grounded in empirical observations can be quite rewarding, not only to researchers, but also to their peers, who can contribute to the further development of new theories through additional research, and to research participants who may appreciate getting a bird’s-eye view of their every day.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Factors That May Promote an Effective Local Research Environment

1 Program in Epithelial Biology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA

2 Department of Dermatology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA

3 Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Healthcare System, Palo Alto, California, USA

Carolyn S. Lee

M. peter marinkovich, howard y. chang.

4 Center for Personal Dynamic Regulomes, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA

Anthony E. Oro

Paul a. khavari.

Rapid progress in high-dimensional data generation offers unprecedented opportunities to advance biomedical research and precision health at the same time that regulatory and funding pressures appear to be increasing. In this context, local research environments can play an important role in facilitating investigative success. In this editorial, we note factors that may be helpful in promoting an effective local bench research environment. We note these factors from subjective personal experience as opposed to a systematic comparative study. The co-authors believe, however, that these factors may contribute to a research environment where investigators can effectively pursue research and where trainees can successfully grow toward independence. These factors include (i) a critical mass of investigators as well as trainees, (ii) a research space configuration that promotes interaction, (iii) a focus on technical innovation, (iv) collaboration with colleagues engaged in both fundamental science and patient-centric studies, and (v) a set of investigator research interests and community culture that promotes synergy. We believe that optimization of these factors may facilitate an effective research environment.

The local environment where research is conducted can help produce an effective research community in health-related fields, such as Dermatology. For such clinically connected biomedical fields, such a local research environment is commonly, but not exclusively, embodied organizationally at the level of the department. Additional organizational forms include institutes, multidisciplinary programs, and thematically focused research buildings. However, for the purposes of this discussion, we define the local research environment as the context around physically proximal investigators with a shared research field. Measurable features of success emerging from such an environment may include discovery of new insights and approaches that improve health, publication of high impact scholarship that advances the field, innovation of new biomedical technologies of broad utility to the global community, successful training of new independent principal investigators (PIs), sustainability in obtaining peer reviewed funding, and synergy in applying advances from other fields. Sustained achievement of such positive features is designed to catalyze the advances that will ultimately improve human health.

But what are important features of an effective local research environment? Surprisingly, given the importance of this question to progress in biomedicine, this issue has not, to our knowledge, been subjected to a large-scale systematic study. Although numerous publications exist on individual researcher career success, successful grant proposals, and even how to put together large disease-focused multi-institutional networks, factors important to the establishment and maintenance of effective local research communities have received less attention. Over the past decade, the co-authors have developed a shared perspective on this question. This perspective is not based on systematic data collection and analysis and is thus subjective, with the limitations that accompany such an approach. We believe, however, that a successful local bench research community benefits from a critical mass of investigators and trainees, research space that promotes interaction, a focus on technical innovation, collaboration with fundamental scientists as well as patient-centric investigators, interlocking investigator research interests, and a community culture that promotes synergy ( Table 1 ). We acknowledge the substantial limitations of this perspective in that it is both preliminary and subjective, yet offer it in the hope stimulating future systematic studies of this question.

Selected potential factors that may support an effective local research environment

| Critical mass of investigators | Research space configuration |

| Critical mass of trainees | Technical innovation focus |

| Collaboration with basic scientists | Collaboration with patient-centric researchers |

| Interlocking investigator interests | Culture of synergy |

A critical mass of investigators and trainees can be important to research community success for multiple reasons. For example, having a large enough pool of investigators within a local research community can provide the opportunity for intellectual synergy, depth of knowledge, and diversity of perspectives that can be helpful in solving difficult research problems. It can also enlarge the scope of immediately accessible practical technical expertise to effectively address research questions experimentally. It can, moreover, facilitate successfully funded multi-investigator research proposals as well as disease-focused philanthropic support by bringing together a critical mass of different expertise to address specific questions comprehensively. A substantial trainee population may also be very helpful in the rapid flow of information between individual laboratories, leading to their rapid adoption throughout a local research community. Substantial research community size can also help assure that critical technical and theoretical knowledge is not lost to the community with the departure of any single individual or small group of individuals. Critical mass thus can support a sustainably effective local research environment in multiple ways.

Research space configured to promote interaction among PIs, staff, and trainees is another factor that can promote an effective local research environment. Many bench researchers can recall seemingly random encounters in labs, hallways, or other common spaces that led to discussions that ultimately accelerated research progress. A space arrangement such as a large shared lab space, shared hallway or shared common area may lead to frequent daily contact among members of a local research community in a manner that may help facilitate collaborative exchange of ideas. Such productive proximity can facilitate fruitful exchange of ideas and technologies. Such space is also ideal to capture cost reductions associated with adjacent shared equipment, the use of which can itself further promote synergistic interactions. Although the balance between person-to-person contact and focused experimental execution can differ among fields and institutional cultures, a lack of daily contact within the local research environment can impair the free flow of ideas and synergistic discussions. Research space that encourages frequent contact among all members of the community may therefore help facilitate a successful local research environment.

The capacity to address new questions in biomedicine is often enabled by new technologies, and, thus, a focus on technical innovation within a local research community can also contribute to an effective local research environment. Cross-investigator subgroups of individuals focused on technical innovation in specific areas in a local community of researchers may synergistically develop additional new technologies in these areas. Such collaborative innovation can yield particularly valuable fruits when the resulting methodologies are quickly applied to questions of interest by immediately proximal laboratory neighbors, who have themselves seen firsthand the advantages and limitations of the new technology as it has been developed. In this context, investigators trying to address a specific research question may find themselves equipped with a powerful new locally developed and validated technology that enhances their progress before that technology’s more general acceptance and adoption by the global research community. A culture of technical innovation within a local research environment can thus accelerate progress by the community members involved.

Active collaboration across the spectrum of biomedical research, from fundamental scientists to patient-centered clinical investigators, can contribute to a successful local research environment, especially with respect to bringing fundamental scientific advances closer to human clinical application. In this regard, research communities organized around a specific clinical field or disease, such as Dermatology or Oncology, are positioned to recognize and apply fundamental new approaches to clinically relevant problems. For example, strong collaborations with computational biologists innovating new algorithms toward big data analysis may help unlock information of clinical relevance to precision health applications. Collaborations with patient-centric investigators can likewise be synergistic, as seen, for example, in the new clinical trials emerging from laboratory-based insights into the pathogenesis of specific skin cancers. Meaningful collaborations across the full spectrum of biomedical research are thus of potentially strong utility in creating and maintaining an effective local research environment.

Interlocking investigator research interests combined with a community culture that promotes synergy, as opposed to direct competition, are additional factors that can help facilitate local research environment success. Interlocking research interests among local investigators can enhance engagement and interest among investigators in each other’s work. For example, PIs focused on different aspects of cancer may be able to both contribute to and benefit from cancer work of common interest being done by adjacent colleagues, often bringing complementary expertise to bear on challenges of interest. A happy medium somewhere between a perfect overlap of community PI interests and a complete unrelatedness of research foci is helpful in this regard, however, to forestall both direct competition and disengagement, respectively. A culture where synergy is expected and potentially destructive competition is unacceptable to all PIs may be particularly important in promoting an atmosphere of trust that enables intellectual sharing and synergy among members of the local research community. Younger investigators, who may be particularly vulnerable to damage from direct local competition, may benefit most from a culture of generous synergy, although we suggest that such a culture can benefit all who participate in it. Clear PI adherence to norms of synergy, transparency, and local collaboration is particularly helpful in preserving a positively interacting culture in those inevitable situations where experimentalists in different groups arrive at a similar result or develop a similar new methodology that could lead to direct intracommunity competition. Shared general interests and a high-trust culture of synergy are therefore a potentially important component of a successful local research community.

We note here that a critical mass of investigators and trainees, research space configured to promote interaction, a focus on technical innovation, collaboration with fundamental scientists as well as patient-centric investigators, interlocking investigator research interests, and a community culture that promotes synergy may all help foster local research environment health. As noted, these features are identified based on the subjective impressions of the co-authors. It is our hope that this perspective will help stimulate systematic work designed to quantitatively characterize the impact of these features, as well as additional elements, that contribute to an effective local research environment.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

How to Write a Research Paper | A Beginner's Guide

A research paper is a piece of academic writing that provides analysis, interpretation, and argument based on in-depth independent research.

Research papers are similar to academic essays , but they are usually longer and more detailed assignments, designed to assess not only your writing skills but also your skills in scholarly research. Writing a research paper requires you to demonstrate a strong knowledge of your topic, engage with a variety of sources, and make an original contribution to the debate.

This step-by-step guide takes you through the entire writing process, from understanding your assignment to proofreading your final draft.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Understand the assignment, choose a research paper topic, conduct preliminary research, develop a thesis statement, create a research paper outline, write a first draft of the research paper, write the introduction, write a compelling body of text, write the conclusion, the second draft, the revision process, research paper checklist, free lecture slides.

Completing a research paper successfully means accomplishing the specific tasks set out for you. Before you start, make sure you thoroughly understanding the assignment task sheet:

- Read it carefully, looking for anything confusing you might need to clarify with your professor.

- Identify the assignment goal, deadline, length specifications, formatting, and submission method.

- Make a bulleted list of the key points, then go back and cross completed items off as you’re writing.

Carefully consider your timeframe and word limit: be realistic, and plan enough time to research, write, and edit.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

There are many ways to generate an idea for a research paper, from brainstorming with pen and paper to talking it through with a fellow student or professor.

You can try free writing, which involves taking a broad topic and writing continuously for two or three minutes to identify absolutely anything relevant that could be interesting.

You can also gain inspiration from other research. The discussion or recommendations sections of research papers often include ideas for other specific topics that require further examination.

Once you have a broad subject area, narrow it down to choose a topic that interests you, m eets the criteria of your assignment, and i s possible to research. Aim for ideas that are both original and specific:

- A paper following the chronology of World War II would not be original or specific enough.

- A paper on the experience of Danish citizens living close to the German border during World War II would be specific and could be original enough.

Note any discussions that seem important to the topic, and try to find an issue that you can focus your paper around. Use a variety of sources , including journals, books, and reliable websites, to ensure you do not miss anything glaring.

Do not only verify the ideas you have in mind, but look for sources that contradict your point of view.

- Is there anything people seem to overlook in the sources you research?

- Are there any heated debates you can address?

- Do you have a unique take on your topic?

- Have there been some recent developments that build on the extant research?

In this stage, you might find it helpful to formulate some research questions to help guide you. To write research questions, try to finish the following sentence: “I want to know how/what/why…”

A thesis statement is a statement of your central argument — it establishes the purpose and position of your paper. If you started with a research question, the thesis statement should answer it. It should also show what evidence and reasoning you’ll use to support that answer.

The thesis statement should be concise, contentious, and coherent. That means it should briefly summarize your argument in a sentence or two, make a claim that requires further evidence or analysis, and make a coherent point that relates to every part of the paper.

You will probably revise and refine the thesis statement as you do more research, but it can serve as a guide throughout the writing process. Every paragraph should aim to support and develop this central claim.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

A research paper outline is essentially a list of the key topics, arguments, and evidence you want to include, divided into sections with headings so that you know roughly what the paper will look like before you start writing.

A structure outline can help make the writing process much more efficient, so it’s worth dedicating some time to create one.

Your first draft won’t be perfect — you can polish later on. Your priorities at this stage are as follows:

- Maintaining forward momentum — write now, perfect later.

- Paying attention to clear organization and logical ordering of paragraphs and sentences, which will help when you come to the second draft.

- Expressing your ideas as clearly as possible, so you know what you were trying to say when you come back to the text.

You do not need to start by writing the introduction. Begin where it feels most natural for you — some prefer to finish the most difficult sections first, while others choose to start with the easiest part. If you created an outline, use it as a map while you work.

Do not delete large sections of text. If you begin to dislike something you have written or find it doesn’t quite fit, move it to a different document, but don’t lose it completely — you never know if it might come in useful later.

Paragraph structure

Paragraphs are the basic building blocks of research papers. Each one should focus on a single claim or idea that helps to establish the overall argument or purpose of the paper.

Example paragraph

George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” has had an enduring impact on thought about the relationship between politics and language. This impact is particularly obvious in light of the various critical review articles that have recently referenced the essay. For example, consider Mark Falcoff’s 2009 article in The National Review Online, “The Perversion of Language; or, Orwell Revisited,” in which he analyzes several common words (“activist,” “civil-rights leader,” “diversity,” and more). Falcoff’s close analysis of the ambiguity built into political language intentionally mirrors Orwell’s own point-by-point analysis of the political language of his day. Even 63 years after its publication, Orwell’s essay is emulated by contemporary thinkers.

Citing sources

It’s also important to keep track of citations at this stage to avoid accidental plagiarism . Each time you use a source, make sure to take note of where the information came from.

You can use our free citation generators to automatically create citations and save your reference list as you go.

APA Citation Generator MLA Citation Generator

The research paper introduction should address three questions: What, why, and how? After finishing the introduction, the reader should know what the paper is about, why it is worth reading, and how you’ll build your arguments.

What? Be specific about the topic of the paper, introduce the background, and define key terms or concepts.

Why? This is the most important, but also the most difficult, part of the introduction. Try to provide brief answers to the following questions: What new material or insight are you offering? What important issues does your essay help define or answer?

How? To let the reader know what to expect from the rest of the paper, the introduction should include a “map” of what will be discussed, briefly presenting the key elements of the paper in chronological order.

The major struggle faced by most writers is how to organize the information presented in the paper, which is one reason an outline is so useful. However, remember that the outline is only a guide and, when writing, you can be flexible with the order in which the information and arguments are presented.

One way to stay on track is to use your thesis statement and topic sentences . Check:

- topic sentences against the thesis statement;

- topic sentences against each other, for similarities and logical ordering;

- and each sentence against the topic sentence of that paragraph.

Be aware of paragraphs that seem to cover the same things. If two paragraphs discuss something similar, they must approach that topic in different ways. Aim to create smooth transitions between sentences, paragraphs, and sections.

The research paper conclusion is designed to help your reader out of the paper’s argument, giving them a sense of finality.

Trace the course of the paper, emphasizing how it all comes together to prove your thesis statement. Give the paper a sense of finality by making sure the reader understands how you’ve settled the issues raised in the introduction.

You might also discuss the more general consequences of the argument, outline what the paper offers to future students of the topic, and suggest any questions the paper’s argument raises but cannot or does not try to answer.

You should not :

- Offer new arguments or essential information

- Take up any more space than necessary

- Begin with stock phrases that signal you are ending the paper (e.g. “In conclusion”)

There are four main considerations when it comes to the second draft.

- Check how your vision of the paper lines up with the first draft and, more importantly, that your paper still answers the assignment.

- Identify any assumptions that might require (more substantial) justification, keeping your reader’s perspective foremost in mind. Remove these points if you cannot substantiate them further.

- Be open to rearranging your ideas. Check whether any sections feel out of place and whether your ideas could be better organized.

- If you find that old ideas do not fit as well as you anticipated, you should cut them out or condense them. You might also find that new and well-suited ideas occurred to you during the writing of the first draft — now is the time to make them part of the paper.

The goal during the revision and proofreading process is to ensure you have completed all the necessary tasks and that the paper is as well-articulated as possible. You can speed up the proofreading process by using the AI proofreader .

Global concerns

- Confirm that your paper completes every task specified in your assignment sheet.

- Check for logical organization and flow of paragraphs.

- Check paragraphs against the introduction and thesis statement.

Fine-grained details

Check the content of each paragraph, making sure that:

- each sentence helps support the topic sentence.

- no unnecessary or irrelevant information is present.

- all technical terms your audience might not know are identified.

Next, think about sentence structure , grammatical errors, and formatting . Check that you have correctly used transition words and phrases to show the connections between your ideas. Look for typos, cut unnecessary words, and check for consistency in aspects such as heading formatting and spellings .

Finally, you need to make sure your paper is correctly formatted according to the rules of the citation style you are using. For example, you might need to include an MLA heading or create an APA title page .

Scribbr’s professional editors can help with the revision process with our award-winning proofreading services.

Discover our paper editing service

Checklist: Research paper

I have followed all instructions in the assignment sheet.

My introduction presents my topic in an engaging way and provides necessary background information.

My introduction presents a clear, focused research problem and/or thesis statement .

My paper is logically organized using paragraphs and (if relevant) section headings .

Each paragraph is clearly focused on one central idea, expressed in a clear topic sentence .

Each paragraph is relevant to my research problem or thesis statement.

I have used appropriate transitions to clarify the connections between sections, paragraphs, and sentences.

My conclusion provides a concise answer to the research question or emphasizes how the thesis has been supported.

My conclusion shows how my research has contributed to knowledge or understanding of my topic.

My conclusion does not present any new points or information essential to my argument.

I have provided an in-text citation every time I refer to ideas or information from a source.

I have included a reference list at the end of my paper, consistently formatted according to a specific citation style .

I have thoroughly revised my paper and addressed any feedback from my professor or supervisor.

I have followed all formatting guidelines (page numbers, headers, spacing, etc.).

You've written a great paper. Make sure it's perfect with the help of a Scribbr editor!

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

- Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide

- Research Paper Format | APA, MLA, & Chicago Templates

More interesting articles

- Academic Paragraph Structure | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Checklist: Writing a Great Research Paper

- How to Create a Structured Research Paper Outline | Example

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- How to Write Topic Sentences | 4 Steps, Examples & Purpose

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Research Paper Damage Control | Managing a Broken Argument

- What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Get unlimited documents corrected

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Selecting Research Area

Selecting a research area is the very first step in writing your dissertation. It is important for you to choose a research area that is interesting to you professionally, as well as, personally. Experienced researchers note that “a topic in which you are only vaguely interested at the start is likely to become a topic in which you have no interest and with which you will fail to produce your best work” [1] . Ideally, your research area should relate to your future career path and have a potential to contribute to the achievement of your career objectives.

The importance of selecting a relevant research area that is appropriate for dissertation is often underestimated by many students. This decision cannot be made in haste. Ideally, you should start considering different options at the beginning of the term. However, even when there are only few weeks left before the deadline and you have not chosen a particular topic yet, there is no need to panic.

There are few areas in business studies that can offer interesting topics due to their relevance to business and dynamic nature. The following is the list of research areas and topics that can prove to be insightful in terms of assisting you to choose your own dissertation topic.

Globalization can be a relevant topic for many business and economics dissertations. Forces of globalization are nowadays greater than ever before and dissertations can address the implications of these forces on various aspects of business.

Following are few examples of research areas in globalization:

- A study of implications of COVID-19 pandemic on economic globalization

- Impacts of globalization on marketing strategies of beverage manufacturing companies: a case study of The Coca-Cola Company

- Effects of labour migration within EU on the formation of multicultural teams in UK organizations

- A study into advantages and disadvantages of various entry strategies to Chinese market

- A critical analysis of the effects of globalization on US-based businesses

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is also one of the most popular topics at present and it is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. CSR refers to additional responsibilities of business organizations towards society apart from profit maximization. There is a high level of controversy involved in CSR. This is because businesses can be socially responsible only at the expense of their primary objective of profit maximization.

Perspective researches in the area of CSR may include the following:

- The impacts of CSR programs and initiatives on brand image: a case study of McDonald’s India

- A critical analysis of argument of mandatory CSR for private sector organizations in Australia

- A study into contradictions between CSR programs and initiatives and business practices: a case study of Philip Morris Philippines

- A critical analysis into the role of CSR as an effective marketing tool

- A study into the role of workplace ethics for improving brand image

Social Media and viral marketing relate to increasing numbers of various social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube etc. Increasing levels of popularity of social media among various age groups create tremendous potential for businesses in terms of attracting new customers.

The following can be listed as potential studies in the area of social media:

- A critical analysis of the use of social media as a marketing strategy: a case study of Burger King Malaysia

- An assessment of the role of Instagram as an effective platform for viral marketing campaigns

- A study into the sustainability of TikTok as a marketing tool in the future

- An investigation into the new ways of customer relationship management in mobile marketing environment: a case study of catering industry in South Africa

- A study into integration of Twitter social networking website within integrated marketing communication strategy: a case study of Microsoft Corporation

Culture and cultural differences in organizations offer many research opportunities as well. Increasing importance of culture is directly related to intensifying forces of globalization in a way that globalization forces are fuelling the formation of cross-cultural teams in organizations.

Perspective researches in the area of culture and cultural differences in organizations may include the following:

- The impact of cross-cultural differences on organizational communication: a case study of BP plc

- A study into skills and competencies needed to manage multicultural teams in Singapore

- The role of cross-cultural differences on perception of marketing communication messages in the global marketplace: a case study of Apple Inc.

- Effects of organizational culture on achieving its aims and objectives: a case study of Virgin Atlantic

- A critical analysis into the emergence of global culture and its implications in local automobile manufacturers in Germany

Leadership and leadership in organizations has been a popular topic among researchers for many decades by now. However, the importance of this topic may be greater now than ever before. This is because rapid technological developments, forces of globalization and a set of other factors have caused markets to become highly competitive. Accordingly, leadership is important in order to enhance competitive advantages of organizations in many ways.

The following studies can be conducted in the area of leadership:

- Born or bred: revisiting The Great Man theory of leadership in the 21 st century

- A study of effectiveness of servant leadership style in public sector organizations in Hong Kong

- Creativity as the main trait for modern leaders: a critical analysis

- A study into the importance of role models in contributing to long-term growth of private sector organizations: a case study of Tata Group, India

- A critical analysis of leadership skills and competencies for E-Commerce organizations

COVID-19 pandemic and its macro and micro-economic implications can also make for a good dissertation topic. Pandemic-related crisis has been like nothing the world has seen before and it is changing international business immensely and perhaps, irreversibly as well.

The following are few examples for pandemic crisis-related topics:

- A study into potential implications of COVID-19 pandemic into foreign direct investment in China

- A critical assessment of effects of COVID-19 pandemic into sharing economy: a case study of AirBnb.

- The role of COVID-19 pandemic in causing shifts in working patterns: a critical analysis

Moreover, dissertations can be written in a wide range of additional areas such as customer services, supply-chain management, consumer behaviour, human resources management, catering and hospitality, strategic management etc. depending on your professional and personal interests.

[1] Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6th edition, Pearson Education Limited.

John Dudovskiy

- 3b- Selecting a Research Site

Now that you are aware of some of the things you will be looking for and reading as a researcher, you can begin to think about possible sites for your primary research. Over the years, students using this text, engaging in ethnographic research projects, have studied a wide range of sites and communities. These sites have been both physical and virtual, dealing with online and real-time communities. Sometimes students see themselves as complete insiders, and sometimes students are less able to find that connection immediately, and choose a location because of another interest, such as cultural background, personal belief, or even social interest. Examples of research sites chosen by students in first year writing classrooms:

Dog parks Ethnic restaurants Art activist projects Laundromats Family holiday parties Smoking lounges Dorm spaces Workspaces Online discussion groups focusing on any number of topics

No matter what, the most important factor when selecting your own site is choosing a place or space or group of people to whom you already feel connected in some way, either by direct membership, burgeoning interest, or cultural/political belief. That last statement is so important that it merits repetition. The most important consideration as you narrow your search for a research site is to identify some kind of a connection with the place/space, even if you might not consider yourself a complete insider, even if you believe you know very little about the culture. We recommend that students have a personal connection with their site for a few reasons:

- One semester is not enough time to conduct research and then write an enthographic essay discussing the behaviors and/or beliefs concerning a particular site/group/community about which you know, and initially care, absolutely nothing. You want to give yourself a leg up and choose your site based on a genuine interest or personal connection with a site so that you have a starting point for your observations and analysis.

- The site you select will be a place you go or a group you meet with for many, many, many hours over the next weeks. Your site will be your text. If you are not “into†your research or “into†your site, chances are that you’ll be bored and not want to conduct your research. And, then writing an essay will become more of a chore than a challenge.

- If you have an identifiable connection with the site, you will be better able to embrace and understand the role of the participant-observer in ethnographic data collection. To some degree, you will need to see yourself as part of, rather than separate, above, or beyond the community/site you’re researching. Choosing a research site based upon personal connection allows you to more easily become one of the subjects of your own research, thereby increasing your own abilities to conduct reflexive analysis of the community and yourself.

There is an important caveat if you are considering writing as an insider and selecting a group or site to which you already belong. The “insider†perspective is challenging because it can be quite difficult to see yourself and your friends with the eyes of a researcher and observer when you are not confronted with anything unfamiliar, if you are simply doing what is “normal.†You also may find that it becomes awkward to talk and write about some of the observations you make. Being able to see patterns and find the rituals and rules that members of a community take for granted is a challenge if you are a part of that community.

An example: One student decided to look at how Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was able to form such strong support networks. This was an “insider†group for him because he attended an AA meeting every day. As a writer and ethnographer, his challenge was to take that very familiar world and to see it with the new eyes of a cultural observer. While he could see and report on the very obvious rituals and “rules†of AA and AA meetings, he was not comfortable writing about some of the deeply personal issues that came up in the meetings in which he was both an active participant and an observer. He was not ready, nor was he ethically able, to share some of those things with the world outside of AA. Ultimately he was able to write a very good essay about how AA created a “safe†space for him. The struggles he faced in writing a very personal, close-to-home ethnography are not uncommon when researching as an “insider,†so you should keep these things in mind as you consider possible research sites.

The challenge in writing from more of an outsider perspective, though making sure to choose a site based upon some genuine interest that is not driven by voyeurism, is the opposite of that of the insider challenge. You will probably find many patterns and interesting things to explore, but you may have more difficulty becoming a participant in the community and finding the meaning in your observations. Deciding which behaviors are meaningful (rituals) and which are just done (habit) can be problematic. If you are able to discern between those to things, you then have to move on to presenting an interpretation of what the meaning might be. You will need to be very aware of your own filters and make sure that you find out how the members of the community see things.