Cookie Consent

- Therapist jobs

Why attraction, love, and commitment is important?

Attraction, love, and commitment are all great components to a healthy relationship. Why each of these looks different for every couple, they are all very important to maintain a healthy relationship. These things combined help bring great value to a relationship to help it keep going. The value that these bring are what will help a couple push through the valleys that relationships naturally go through. Some of these components might struggle at certain times, but hopefully the other components can help pick up the slack. For example, when attraction is struggling between a couple, the love and commitment could hopefully help them get through that struggle.

As these components grow and maintain, it can help build trust and security in the relationship, which is very important. That development of security is what will help the relationship be worth it even when times get rough. Try to remember that attraction has an emotional and a physical component. If you can remember that you can hopefully try to see to each of those for your partner and for yourself. It can be really healthy to have discussions with your partner about how you personally develop emotional and physical attraction.

Love is a component that each of us show and receive differently. It can be helpful to try and pinpoint how you receive love so that your partner can know what best to show you. It can also be helpful to understand how you most naturally show love, but make sure to also keep in mind how your partner receives love. For example, some of us are more likely to show love through words of affirmation whereas others might show love through acts of service. Also, how we show and receive love change throughout the course of a relationship and so it is important to check in with yourself about that. With attraction and love hopefully being in a good place, the trust for the commitment should hopefully follow. Try to make sure that you are transparent about what commitment looks like to you so that you and your partner can hopefully be on the same page.

You will be logged out in seconds.

Essays About Commitment: Top 5 Examples and 7 Prompts

If you are writing essays about commitment, read our guide with helpful examples and writing prompts to help you get started.

To be committed to something is to be devoted and willing to put time, energy, and effort into it. Commitment can be directed towards other people, organizations, goals, or beliefs. However, it is more than just a promise; it requires consistent dedication.

Commitment is a broad term and can include committing to tasks, such as chores, or significant commitments in life, like marriage or priesthood. Commitment is an admirable trait that shows courage and determination, but it can also be challenging to commit to a task, lifestyle change, or moral decision. Such a broad topic makes for an exciting essay; keep reading to see our top examples and prompts to help you get started.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

5 Top Essay Examples

1. the difference between love and commitment by howard soto, 2. a short essay on commitment by bleri lleshi, 3. honor, courage, commitment by ada robinson, 4. commitment for a better future. by sheel nidhi tripathi.

- 5. Your Goals Are Nothing Without Commitment by Anthony J. Yeung

1. Why Is Commitment Important?

2. what are you committed to, 3. commitment in action, 4. when i failed at commitment, 5. commitment role models, 6. how to practice commitment, 7. values that align with commitment.

“Commitment is communicated primarily through shared experiences and moments. For example individuals might opt to have some specified moments they associate and share certain experiences and activities such as outdoor activities. This essentially calls for dedications. Love however is communicated by the parties involved being emotionally available for each other. It involves the doing of certain favors for each other without complain regardless of the situation.”

Soto explains how love and commitment are different, yet that commitment is an essential part of love. In summary, anyone can practice commitment, which is essential for creating a successful and loving relationship. Love takes commitment, as you must be willing to make sacrifices.

“Commitment means giving a piece of ourselves in what we do. It sounds simple but it is not. It’s simple nor obvious. The obviousness got lost in the dominance of the ‘everyone for his/her own’ discourse. For those who can not give that piece of his or herself in his or her actions, it is difficult to understand why some of us do commit ourselves. Often we even cannot give an exact reason of why we are committed. Commitment must be experienced and not explained that is why my explanation here, can never match the experience of commitment.”

In his essay, Lleshi writes about why it is more important to be committed than ever. This is because many problems require our attention, such as the spread of individualism. To Lleshi, commitment means sacrificing a part of ourselves to achieve a profound goal. He wants everyone to be committed to a better future and united in our commitment to change global issues, such as stopping pollution and global warming.

“Often we even cannot give a exact reason of why we are committed. Commitment must be experienced and not explained that is why my explanation here, can never match the experience of commitment. We must always abide by an uncompromising code of integrity, taking responsibility for our actions and keeping our word. We shall earn respect up and down the chain of command. Be honest and truthful in our dealings with each other, and with those outside the Navy.”

Robinson, a member of the U.S. Navy, describes the values they are taught, including commitment. The concepts of honor, bravery, courage, and commitment are instilled in every officer in the navy. They are taught to take responsibility for their mistakes, be devoted to protecting and serving the American nation, and be committed to upholding the country’s laws.

“The unknown can be a scary feeling, adventure as an idea is thrilling but not everyone is cut out to live it.I have lost my sleep, and when I fall asleep I get these weird dreams, which shows me all the things that I am thinking subconsciously. Yet, from here on I am letting go all my fears and do all the things I dreamt to do as a kid.”

In her essay, Tripathi writes about how her life has been challenging and that she has always let the influences and rules of others dictate her actions. However, she is now committed to building a healthier lifestyle through fitness, working on her communication and listening skills, and taking an interest in her hobbies.

5. Your Goals Are Nothing Without Commitment by Anthony J. Yeung

“Find a reason for being that inspires you to be earnest with each day. That commitment, in and of itself, will enhance your life in countless ways. I’ve learned there’s no greater feeling than keeping the promises we make to ourselves. There’s an overwhelming feeling of pride, joy, love, and gratitude that goes beyond the goal itself and gives you the confidence you can achieve anything.”

Yeung discusses the importance of setting achievable goals so that we have a reason to be committed. He wants people to stay on course and stop making excuses for failing to achieve goals; he laments that life often distracts people from achieving goals. Instead, he encourages readers to take a deep look into themselves and set goals based on things they enjoy and are inspired by. That way, it will be so much easier to stay committed.

7 Prompts for Essays About Commitment

Commitment is essential to achieving goals and success, but how exactly? Write about why commitment is meaningful and valuable. Then, explore the importance of commitment in different situations. Research the benefits of being committed to a task or person, and describe these benefits within your essay. For help with this topic, read the essay examples above for inspiration.

Everyone has committed to something or someone in their life. In your essay, list some of your goals, explaining why you have chosen to commit to them. If applicable, you can also give examples of people or organizations you are committed to, whether it be loved ones or your job.

You will feel proud and relieved when you fulfill a commitment. Recall a time you showed commitment and were proud of it. Describe the commitment, and explain to your readers how you fulfilled (or continue to fulfill) your commitment. Explain your reasons for dedicating your time and energy to this commitment.

On the other hand, you may also feel it is more appropriate to write about a time you failed to show commitment. Reflect on this experience and explain what you would do if you were allowed to repeat it.

We all have role models that we look up to for inspiration. Who is this to you? Write about who has shown commitment and inspires you to be committed to your goals or loved ones. It can be a loved one, a famous person, or even a fictional character. Make sure you explain how this individual is an excellent example of commitment.

In your essay, discuss habits you can pick up to commit to someone or something. It can include habits such as waking up early, getting adequate sleep, or a consistent dedication to a particular person or task. Describe how to practice these habits and achieve your goals through commitment and hard work.

Commitment is associated with other important traits, such as bravery, honesty, and courage. For your essay, you can also discuss what values you need to practice commitment to the best of your ability, be sure to explain your choices adequately.

If you’re stuck picking an essay topic, check out our guide on how to write essays about depression .

If you’d like to learn more, in this guide, our writer explains how to write an argumentative essay .

Stages of Love: Unraveling the Journey from Attraction to Commitment

We’ve all felt it, that dizzying sensation of falling head over heels for someone. But what exactly is happening in our brains when we tumble into the abyss of love? As an expert in human emotions and relationships, I’d like to delve into the stages of love , exploring each phase from a psychological perspective.

In its infancy, love is a whirlwind of attraction and infatuation. You’re consumed by thoughts of your beloved, with every detail about them seeming absolutely perfect. This honeymoon phase can be intoxicating but it’s also temporary – a fact many people find hard to accept.

Beyond this initial enchantment lies the second stage: deep attachment. Here, comfort and companionship overrule passion as you settle into the rhythm of life together. But don’t be fooled! This isn’t a downgrade from those earlier fireworks; it’s a deeper bond formed through shared experiences and understanding. It may not be as flashy as infatuation but it’s arguably more rewarding.

So why does this transition happen? And how can we navigate these stages effectively? Let’s dive in further, examining the science behind these shifts in emotion and offering some tips on sustaining long-term love.

Understanding the Stages of Love

Ever wonder why love feels like a roller coaster ride? It’s because it doesn’t stand still. It evolves, changes and grows through various stages. Let’s unravel this mystery together.

The first stage is the “Infatuation Stage”. We’ve all been there, haven’t we? When our heart skips a beat every time that special someone comes into view. Butterflies in the stomach become a daily phenomenon. Infatuation can feel exhilarating, but it’s often short-lived.

Next up is the “Honeymoon Phase”. This is when you can’t seem to get enough of each other. You’re both head over heels in love, spending every possible moment together. Studies show that this phase usually lasts from one to two years.

- Stage 1 : Infatuation

- Stage 2 : Honeymoon Phase

Once the honeymoon phase fades away, reality sets in and we enter the “Disillusionment Stage”. This is when couples start noticing each other’s flaws and arguments may become more frequent.

After weathering through disillusionment (if you make it), you’ll find yourself in the “Deep Attachment Stage”. By now, you’ve seen your partner at their best and worst yet choose to stick with them anyway. This stage signifies deep emotional attachment and stability.

Finally, we have what experts call “Mature Love” or lifelong partnership where companionship trumps passion. The bond forged over shared experiences becomes unbreakable here.

Here are these stages again:

- Stage 3 : Disillusionment

- Stage 4 : Deep Attachment

- Stage 5 : Mature Love

Understanding these stages can help navigate relationships better while also managing expectations realistically.

The First Stage: Attraction and Romance

I’m sure we’ve all felt it, that initial spark when you meet someone who piques your interest. It’s the first stage of love, often characterized by physical attraction and a sense of excitement. This is the time when our hearts race, our palms sweat, and we can’t stop thinking about that special someone .

What causes this overwhelming feeling of attraction? Science suggests it’s a cocktail of chemicals racing through our brains. There’s dopamine, responsible for feelings of happiness and desire; adrenaline which fuels those nervous butterflies; and serotonin that keeps us dreaming about our new love interest.

Let me paint a picture with some examples. Remember that high school crush? The one who made your heart flutter every time they passed by your locker? Or maybe it was a friend who slowly transformed into something more in your eyes. This phase is marked by idealization – seeing only the best in the other person – and intense emotions.

| Chemical | Effect |

|---|---|

| Dopamine | Happiness, Desire |

| Adrenaline | Nervous Excitement |

| Serotonin | Obsessive Thoughts |

But remember folks, while these feelings might be intoxicating at first, they’re not designed to last forever. Psychologist Dorothy Tennov coined the term ‘limerence’ to describe this state. Limerence lasts on average between 18 months to 3 years before transitioning into deeper stages of love.

So let’s break it down:

- Physical attraction kicks things off.

- Brain chemicals like dopamine create happy, obsessive thoughts.

- These intense feelings don’t last forever but transition into deeper stages over time.

Although this stage can feel like a whirlwind, it sets up an important foundation for relationship building as we move forward through subsequent stages of love!

The Second Stage: Building a Deeper Connection

If you’ve ever been in love, you’ll know it’s not all rainbows and butterflies. It’s during the second stage of love that we really start to build those deeper connections. Let me tell you, it’s more than just sharing your favorite pizza toppings or TV shows.

During this phase, trust begins to solidify as the foundation of the relationship. You’re starting to reveal your authentic selves, not just the polished versions you presented during the initial attraction stage. Sharing vulnerable moments and stories is typical during this period. For example, you might discuss past relationships or personal insecurities – yes, we’ve all got them!

Now don’t get me wrong; this stage isn’t always easy. It can be uncomfortable getting so emotionally raw with another person. But studies have shown that vulnerability is key in building deep relationships! According to a study by Dr.Brene Brown at the University of Houston:

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| 1 | People who were able to form strong bonds reported feeling comfortable being vulnerable with their partner |

It’s also important to note that communication plays a vital role here too – and I’m not just talking about chatting over dinner! Real communication means expressing needs, desires, fears…the whole shebang.

Here are some pointers for effective communication in this stage:

- Be clear about what you need from your partner.

- Show empathy when they share their feelings.

- Respect boundaries set by each other.

At its core though, building a deeper connection boils down to one thing: understanding one another on an intimate level – physically and emotionally. That’s where real love starts taking root!

So there you have it – that’s the second stage of love for ya! While it may feel like an emotional rollercoaster ride at times (and believe me, it often does), remember that it’s paving way for a stronger bond between you and your partner. But hold on tight, we’re just getting started!

The Third Stage: Disillusionment or Understanding?

I’ve arrived at the third stage of love, and let’s be honest – it’s a bit of a crossroad. We all start off in relationships with hearts full of hope, but then reality sets in. This stage can either lead to disillusionment or understanding. It all depends on how we navigate the twists and turns.

Think back to your first love, when everything seemed perfect. Then suddenly you started noticing flaws in your partner that you’d never seen before. You may have even started questioning if you were right for each other at all. That’s disillusionment setting in, folks! But hold on – don’t hit the panic button just yet.

You see, this stage isn’t necessarily a death sentence for your relationship. In fact, it could be an opportunity for growth – a chance to build deeper understanding and acceptance. For example, instead of focusing on annoying habits like leaving dishes unwashed or forgetting birthdays (yes, we’ve all been there), try focusing on what initially drew you to them: their sense of humor? Their kindness? Their resilience?

Here are some stats to chew on:

| Stat | Detail |

|---|---|

| 85% | Of couples experience disillusionment within the first few years |

| 70% | Of these couples work through it and reach understanding |

Now I’m not saying it’ll be easy; but developing understanding is key for long-term happiness in relationships.

So where does one begin? With communication – that’s where! Talk about your feelings without blaming each other (easier said than done!). Be patient with yourself and your partner during this challenging time.

And remember: every couple goes through this third stage at some point. It’s NORMAL. So take heart – if others have navigated these choppy waters successfully, so can you!

- Understand that disillusionment is part of the journey

- Focus on your partner’s positive traits

- Communicate, communicate, communicate

So here’s to understanding and working through disillusionment – because that’s what love is all about.

A Closer Look at the Fourth Stage: Creating Lasting Bonds

Peeling back the layers of love, we find ourselves nestled in the fourth stage – creating lasting bonds. It’s a step that may seem daunting but is truly rewarding. This phase is all about building on the emotional intimacy you’ve established and solidifying it into a durable, long-term connection.

Let’s get down to brass tacks here. In this stage, you’re no longer just dating or ‘seeing each other’. You’re committed to making this relationship work. The bond that forms during this period isn’t merely based on attraction or romance; it’s anchored in mutual respect, trust, and admiration.

These aren’t just hollow words. Studies back them up too! For instance, a study by Drs John and Julie Gottman found that couples who show mutual respect and admiration are more likely to have long-lasting relationships.

Here are some key aspects of bonding:

- Shared Experiences : Activities like traveling together or overcoming challenges as a team strengthen your bond.

- Mutual Goals : Sharing life goals aligns your path forward as a couple.

- Open Communication : Talking about feelings promotes understanding and closeness.

By now you might be wondering how exactly one goes about creating these lasting bonds? Well fear not! I’ll walk you through some practical steps:

- Practice active listening: Show genuine interest in what your partner says.

- Express appreciation regularly: Small acts of kindness go a long way.

- Keep promises: Trust is built when actions match words.

This stage of love is indeed an art – an art of nurturing, patience, understanding, compromise, and above all else… Love itself! So why don’t we roll up our sleeves and dive deeper into this beautiful journey?

The Fifth and Ultimate Stage of Love: Unconditional Acceptance

Reaching the fifth stage of love, unconditional acceptance, feels like a breath of fresh air. It’s the point where you’ve seen all sides of your partner – the good, bad, and everything in between – and still choose them every single day. You’ve moved past petty disagreements and superficial flaws to understand that no one is perfect.

This stage isn’t about grand gestures or intense passion – it’s about comfort, stability, and an unshakeable bond. Couples in this phase find joy in everyday moments shared together – a quiet dinner at home after a long day or a lazy Sunday morning spent reading newspapers while sipping coffee.

A study published by the Journal of Social Personal Relationships highlights some fascinating statistics regarding couples who reach this stage:

| Percentage | Insight |

|---|---|

| 60% | Couples who reported experiencing unconditional acceptance from their partners showed lesser relationship anxiety |

| 70% | Individuals reporting high levels of acceptance also reported higher levels of relationship satisfaction |

Now don’t mistake unconditional acceptance for complacency. In fact:

- It means recognizing that your partner isn’t perfect but choosing to love them regardless.

- It’s about understanding that people grow and change over time.

- And most importantly, it involves being a consistent source of support for each other without any conditions attached.

Unconditional acceptance doesn’t mean you accept harmful behaviors or disregard your own needs. Instead, it’s all about balance – acknowledging differences but not letting them overshadow the love you share.

Remember that reaching this stage is no small feat but those who do often enjoy relationships characterized by deep respect, mutual understanding, lasting affection…and yes – plenty of laughter too!

Common Challenges During Love’s Various Stages

Navigating the realm of love isn’t always a smooth cruise. Let’s delve into some of the common challenges that crop up during love’s various stages.

The initial stage, often referred to as the ‘honeymoon phase’, is no stranger to pitfalls. It’s characterized by intense attraction and infatuation, which can cloud judgement. We become so engrossed in our partner that we might overlook red flags or potential issues down the road. We’re also likely to idealize our partners during this phase, which can lead to disappointment when reality finally hits.

Moving on to the power struggle stage, couples often wrestle with differences and conflicts. This is where individuality and independence come into play – we start realizing that our partner isn’t perfect and may not align with every aspect of our life. The key challenge here lies in maintaining respect for each other while navigating these differences.

Next up is stability – a stage where many relationships face comfort zone issues. As mundane routines set in, passion may take a back seat leading to feelings of boredom or dissatisfaction. How you keep the spark alive becomes crucial at this point.

Then comes commitment – deciding whether you’re ready for long-term investment can be daunting. Fear of losing personal freedom or making wrong decisions are common challenges faced in this stage.

Lastly, co-creation involves building something together like starting a family or business venture. Balancing personal goals with joint dreams can be tricky here.

Here’s a quick rundown:

- Honeymoon Phase: Overlooking flaws due to infatuation

- Power Struggle Stage: Dealing with differences and conflicts

- Stability: Waning passion due to routine

- Commitment: Deciding on long-term investment

- Co-Creation: Balancing personal goals with joint ventures

So remember folks, love isn’t just about hearts and flowers; it comes bundled with its fair share of trials and tribulations. But hey, that’s what makes the journey worthwhile, doesn’t it?

Conclusion: Navigating the Journey of Love Successfully

We’ve traversed quite a journey, haven’t we? From the exhilarating first stages of infatuation to the profound depths of enduring love, each phase plays its unique role in our love journey. And just like any other expedition, navigating this path requires understanding, patience, and above all, commitment.

Remember that falling in love is easy; it’s staying in love where the real challenge lies. It’s not always about grand gestures or romantic escapades. Sometimes it’s about those quiet moments you share with your partner on a lazy Sunday afternoon or how you communicate during a disagreement.

Don’t be afraid of conflict either. I can’t stress this enough – conflicts are not necessarily bad for your relationship. On the contrary, they’re opportunities to learn more about each other and grow together as a couple.

- Understand your partner’s perspective

- Learn to compromise

- Communicate effectively

The keyword here is resilience. You need to withstand storms and navigate rough seas if you want to keep sailing together.

And let’s not forget the importance of maintaining your individuality while being part of a pair. It’s vital for both partners to have their own hobbies, friends and interests apart from each other because at the end of the day we’re all individuals sharing our lives with another individual.

Lastly but certainly most important – never stop expressing love for one another. Say ‘I love you’ often and mean it every time you say it.

So there we have it! These are my thoughts on successfully navigating through different stages of love:

- Patience and understanding

- Effective communication

- Maintaining individuality

- Never stop expressing love

Love isn’t always going to be perfect but remember – “A great relationship doesn’t happen because of the love you had in the beginning but how well you continue building love until the end.” Go out there and build your love story with courage and conviction.

Related Posts

The Male Mind in Love: Demystifying Men’s Love Journey

Loving You: To the Moon & Back – A Journey of Endless Love

- Mental Health

- Social Psychology

- Cognitive Science

- Psychopharmacology

- Neuroscience

The psychology of love: 10 groundbreaking insights into the science of relationships

(Photo credit: OpenAI's DALL·E)

In the quest to understand the complex dynamics of love and relationships, recent scientific inquiries have unveiled fascinating insights into how our connections with others shape our mental health, preferences, and overall happiness.

From the profound impact of romantic relationships on psychological well-being to the evolutionary roots of love, these studies offer a comprehensive look into the forces driving our closest bonds. This article delves into the latest research findings, shedding light on the science behind love, attraction, and the deep psychological interplay at the heart of human relationships.

The exploration into the psychology of love spans various disciplines, including social psychology, neuroscience, and evolutionary biology, each contributing unique perspectives to our understanding of romantic connections.

These studies collectively reveal how aspects such as relationship quality, partner preferences, humor, and even our value systems play pivotal roles in the formation and maintenance of romantic relationships. Through a closer examination of these elements, we can begin to appreciate the intricate web of factors that not only draw us together but also sustain love over time.

1. The Link Between Romantic Relationships and Mental Health

In a study published in Current Opinion in Psychology , researchers Scott Braithwaite and Julianne Holt-Lunstad explored the intricate relationship between long-term romantic relationships and mental health. They delved into the question of causality—whether being in a marriage leads to better mental health or if individuals with better mental health are more likely to get married. Their review of both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies revealed that while married individuals generally exhibit better mental health than their non-married counterparts, the direction of causality leans more significantly from the quality and presence of romantic relationships towards improved mental health outcomes. This suggests that being in a committed relationship, such as marriage, tends to enhance one’s mental health more profoundly than less committed forms of cohabitation.

The study highlights the significance of relationship quality, noting that individuals in healthy and satisfying relationships experience better mental health. Moreover, improving the quality of a relationship was found to precede improvements in mental health, reinforcing the idea that positive relationship dynamics play a crucial role in fostering mental well-being. This insight underscores the greater impact that negative aspects of mental health, such as depression and depressive symptoms, have on romantic relationships compared to positive mental health constructs. The researchers emphasized the importance of focusing on preventing negative relationship patterns as a means of safeguarding mental health.

The implications of this research are profound, suggesting that interventions aimed at enhancing relationship quality could be as effective as those targeting individual mental health issues. The findings advocate for a shift in focus towards preventing dysfunctional relationships as a strategic approach to improving overall mental health. By establishing that healthy romantic relationships act as a protective factor against mental health problems, the study underscores the necessity of nurturing positive relationship dynamics. This reinforces the concept that investment in the health of personal relationships can lead to significant benefits for mental health, highlighting relationships as a cornerstone of human well-being.

2. Evolving Preferences in Partner Selection

In a fascinating study published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , researchers led by Julie Driebe delved into how life events and personal growth influence people’s preferences in choosing a romantic partner over time. This research aimed to bridge gaps in understanding whether individuals’ ideal partner preferences evolve and if people are aware of these changes. Through a longitudinal approach, spanning 13 years from an initial speed dating experiment, the study revisited participants to reassess their partner preferences. The findings revealed a complex picture: while core preferences remained relatively stable, significant shifts did occur, notably with less emphasis on physical attractiveness and wealth and more on kindness, humor, and shared values as people aged. The influence of major life events, such as becoming a parent, was also highlighted as a factor contributing to these changes in preferences.

Driebe’s team’s methodology involved recontacting participants from the Berlin Speed Dating Study conducted in 2006, analyzing their responses to understand changes in eight key dimensions of partner preference. Despite the inherent stability in preferences over time, the study identified nuanced shifts, especially an increased value placed on status, resources, and family orientation as individuals aged. Interestingly, the study also discovered discrepancies between participants’ perceptions of their changing preferences and the actual changes observed, particularly regarding status, resources, and intelligence. This discrepancy points to the complexity of self-awareness in how personal growth and life experiences shape partner selection criteria.

The implications of these findings are profound, shedding light on the dynamic interplay between personal development, life experiences, and mate selection. The study underscores the importance of considering how individual experiences and the passage of time mold our desires in romantic partners, suggesting a fluidity in mate preferences that reflects broader personal evolution. Despite limitations, such as the reliance on a specific sample group and the unexplored influence of cultural factors, this research opens new avenues for understanding how and why our criteria for a romantic partner may change as we navigate through life’s milestones. It highlights the importance of acknowledging personal growth and life events in the study of mate selection, suggesting that as individuals evolve, so too do their preferences for a partner, with some changes more perceptible to the individual than others.

3. The Role of Humor in Romantic Attraction

A recent study published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin has illuminated the significant role humor plays in romantic attraction, suggesting that a good sense of humor is not just a desirable trait but is perceived as an indicator of a partner’s creative problem-solving abilities. This research, spearheaded by Erika Langley, a PhD candidate in social psychology at Arizona State University, and her colleague Michelle Shiota, an associate professor, aimed to dissect the underlying reasons why humor is so universally valued in romantic partners. Through a series of six comprehensive studies involving various scenarios—from first-date impressions to long-term relationship dynamics—the researchers discovered that individuals with a keen sense of humor are more appealing as potential partners due to the association of humor with creativity, intelligence, and social competence.

The initial studies focused on participants’ reactions to hypothetical first-date scenarios, revealing that humor significantly influenced the perception of a partner’s creative ingenuity, irrespective of the participant’s gender. This suggests that both men and women value humor for similar reasons, associating it with a partner’s ability to navigate complex situations with inventive solutions. Interestingly, the effect of humor on the perception of creative problem-solving skills was consistent across different relationship contexts, whether the participants were considering a potential partner for a short-term fling or a long-term commitment. Furthermore, humor was valued not only for the immediate joy it brings to interactions but also for the implied cognitive abilities it suggests in a partner, especially in the context of overcoming life’s challenges together.

The latter studies extended these findings, exploring how humor portrayed in online dating profiles and video dating scenarios influences perceptions of potential partners. Profiles and responses infused with humor were not only seen as more creative but also more socially competent, enhancing the individual’s attractiveness for initiating romantic relationships. This comprehensive investigation into the role of humor in romantic attraction underscores its significance beyond mere entertainment, highlighting humor as a key indicator of desirable traits such as creativity and social adeptness.

4. Understanding Love Through the Brain’s Reward System

A study published in Behavioral Sciences by Adam Bode and Phillip S. Kavanagh has unveiled a compelling link between the brain’s reward system and the intensity of romantic love. By crafting a new scale, the Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One (BAS-SLO) Scale, researchers have illuminated how the Behavioral Activation System (BAS)—a mechanism in our brain that drives us towards rewards and motivates our actions—is intricately tied to the depth of romantic feelings we experience. This finding enriches our biological understanding of love, suggesting that the strength of romantic emotions is partially influenced by the same internal system that propels us towards goals and rewards.

The first part of the study involved developing and validating the BAS-SLO Scale with over 1,500 young adults who identified as being in love. This new tool, adapted from the existing Behavioral Activation System Scale, aimed to measure the BAS’s response specifically in romantic contexts. Participants answered questions about their reactions and feelings towards their partners, alongside completing the Passionate Love Scale—30, a measure assessing the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of romantic love. The results indicated that the new scale was reliable and valid for measuring the role of BAS in romantic love, showing that the brain’s reward responsiveness, drive, and fun-seeking behaviors in relation to a partner were closely linked to romantic love intensity.

In the second phase, with a subset of participants, the study further explored how the BAS-SLO scores correlated with the intensity of romantic love, finding that higher sensitivity in the Behavioral Activation System towards a romantic partner was significantly associated with stronger feelings of love. This correlation accounted for almost 9% of the variance in the intensity of romantic feelings, underscoring the substantial role of the BAS in shaping romantic love. Despite some limitations, such as the need for replication in different samples and controlling for the normal functioning of BAS, this research marks a significant step forward in understanding the biological underpinnings of romantic love, opening new avenues for exploring the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral mechanisms that fuel our love lives.

5. Positive Communication’s Impact on Romantic Outcomes

A new study published in Sexual and Relationship Therapy offers insightful findings on the dynamics of positive communication within romantic relationships and its impact on sexual and relationship satisfaction. Conducted by Christine E. Leistner and her team from the Department of Public Health and Health Services Administration at California State University, Chico, the research utilized data from 246 couples to explore how expressions of affection, compliments, and fondness contribute to the satisfaction and desire among partners. Utilizing both traditional statistical analysis and advanced machine learning techniques, the study revealed that positive communication, encompassing acts like showing affection and giving compliments, consistently leads to higher levels of satisfaction and desire in relationships for both individuals and their partners. Interestingly, the study also found nuanced differences in how various forms of positive communication, such as fondness and compliments, uniquely influence sexual satisfaction and desire.

The research highlighted that the impact of positive communication on relationship and sexual satisfaction is complex, with certain combinations of communication types producing different effects based on factors like age and the balance of compliments and affection. For example, while fondness and compliments were identified as strong predictors of sexual satisfaction, the interaction between high levels of compliments and affection showed a surprising nonlinear relationship with sexual satisfaction. In some cases, an abundance of both compliments and affection predicted an increase in sexual satisfaction, whereas, for others, it led to a decrease. Furthermore, the study uncovered age-related differences in how perceived affection from a partner influenced sexual desire, indicating that younger individuals might experience higher sexual desire with less perceived affection, in contrast to older individuals who showed an increase in desire with more affection.

These findings underscore the importance of positive communication in enhancing the quality of romantic relationships, while also pointing to the intricate ways in which such communication interacts with individual and relationship factors. The study’s use of machine learning to reveal nonlinear interactions offers a nuanced understanding of the relationship between communication practices and satisfaction outcomes, suggesting that the effects of positive communication are not universally linear or positive for all couples.

6. Romantic Love’s Evolutionary Roots

In a thought-provoking article published in Frontiers in Psychology , researcher Adam Bode introduces a new theory suggesting that the phenomenon of romantic love may have evolved from the neurobiological and endocrinological mechanisms initially developed for mother-infant bonding. This theory challenges the traditional view, proposed by Helen Fisher, that categorizes sex drive, romantic attraction, and attachment as three distinct emotional systems evolved independently. Bode’s theory posits that romantic love and mother-infant bonding share significant psychological, neurological, and hormonal similarities, indicating that romantic love might be an adaptation of the bonding process between mothers and their infants.

The evidence supporting this theory includes observed behaviors and emotional patterns common to both mother-infant bonding and romantic love, such as intense emotional connections, a desire for physical closeness, and exclusive attention to the loved one. Brain imaging studies have also shown overlapping activity in regions associated with love and bonding, including areas rich in oxytocin and vasopressin receptors, which are crucial for social and emotional behaviors. Furthermore, the presence of high levels of oxytocin in individuals in the early stages of romantic relationships mirrors the hormonal patterns observed in new mothers, reinforcing the idea that these types of love share common biological pathways.

Bode’s theory suggests a fundamental shift in how we understand romantic love, framing it as an evolutionarily repurposed mechanism that builds on the foundation of maternal-infant attachment. This perspective not only deepens our comprehension of human emotional and social bonds but also underscores the intricate ways in which evolutionary processes have shaped our experiences of love and attachment. As this theory continues to be explored and tested through future research, it holds the potential to offer new insights into the evolution of human relationships and the universal nature of love.

7. Goal Coordination and Life Satisfaction in Couples

A study published in the International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology explored the dynamics of how romantic couples in Hungary support each other in achieving personal goals and how this support influences their life satisfaction. The research, led by Orsolya Rosta-Filep and colleagues, focused on the concept of goal coordination, which involves partners aligning their efforts and resources to help each other reach their personal objectives. Through the analysis of 215 heterosexual couples, the study found that those who effectively coordinated on their personal goals not only made more progress in attaining these goals but also experienced higher levels of life satisfaction. This suggests that when couples work together towards their individual ambitions, they not only become better partners but also enjoy a more satisfying life together.

The methodology of the study involved participants evaluating their personal projects and the level of coordination with their partners at the beginning of the study and then assessing their progress and life satisfaction a year later. The findings indicated a clear link between successful goal attainment and increased life satisfaction, highlighting the importance of communication, cooperation, and emotional support in this process. However, the study also noted that goal coordination alone did not directly lead to life satisfaction; the key was the effectiveness of these coordinated efforts. If couples felt supported by their partners and saw tangible results from their joint efforts, this led to long-term life satisfaction, underscoring the value of not just supporting each other’s goals but doing so in a way that yields actual progress.

The research provides valuable evidence on the significance of couples supporting each other’s personal goals and the positive impact this can have on their relationship and overall happiness. The findings advocate for couples to not only coordinate their efforts around each other’s goals but also to ensure these efforts are effective, enhancing both individual and shared life satisfaction.

8. Sexual Activity, Health, and Longevity in Hypertensive Patients

A recent study published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine has found that regular sexual activity may lead to improved health outcomes and longer life spans for middle-aged individuals diagnosed with hypertension (high blood pressure). This research, which analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the United States between 2005 and 2014, involved over 4,500 participants. It revealed that hypertensive patients engaging in more frequent sexual activities tend to have a significantly lower risk of dying from any cause compared to those with less sexual activity.

The significance of this study lies in its exploration of the link between sexual frequency and survival rates in people with hypertension, a condition known for its severe complications and absence of symptoms, making it a silent threat to public health. Researchers discovered that participants who reported having sexual intercourse 12-51 times a year, or more than 51 times a year, demonstrated a notably lower risk of all-cause mortality than those who had sexual activity less than 12 times a year. This association persisted even after adjusting for factors like age, gender, education level, body mass index, smoking status, and existing medical conditions, highlighting a potentially protective effect of sexual activity on overall health in hypertensive patients.

9. Humor’s Vital Role in Sustaining Romantic Connections

A study published in Psychological Science by Kenneth Tan and colleagues from Singapore Management University reveals the significant role of humor in strengthening and maintaining romantic relationships. This research, which involved 108 couples from a large university in Singapore, utilized a daily-diary method to collect 1,227 daily assessments over seven consecutive days. Participants reported their daily experiences of humor within their relationships, as well as their levels of relationship satisfaction, commitment, and perceived partner commitment. The findings suggest that humor acts as a powerful tool for signaling and maintaining interest in a romantic partner, with individuals reporting greater humor engagement on days when they felt more satisfied and committed to their relationships.

The study supports the “interest-indicator model” of humor, proposing that humor is not merely a trait that attracts individuals to each other during the early stages of a relationship but continues to play a crucial role in expressing and reinforcing commitment and satisfaction within established relationships. The researchers found that positive relationship quality was associated with increased humor production and perception, indicating that couples use humor to enhance their relationship quality and signal ongoing interest. Interestingly, the study did not find significant gender differences in the use of humor, challenging the stereotype that men use humor more frequently to attract mates.

These insights highlight the importance of humor in romantic relationships, suggesting that engaging in humorous interactions can contribute to a more satisfying and committed relationship. The research opens up new avenues for exploring the impact of humor in various relationship contexts, including work and parent-child relationships, and how humor might influence perceptions of a partner’s other positive traits, such as creativity, intelligence, and warmth.

10. The Influence of Self-Transcendence Values on Relationship Satisfaction

A study published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin by Reine C. van der Wal and colleagues delves into how personal values, specifically self-transcendence values such as equality, kindness, and compassion, influence the quality of romantic relationships. Through four studies involving over a thousand participants, the researchers explored the connection between these values and relationship satisfaction. They discovered that individuals who prioritize self-transcendence values tend to report higher relationship satisfaction. Interestingly, the presence of these values in one partner did not significantly affect the other partner’s sense of relationship quality, suggesting that these values enhance satisfaction mainly for the individuals who hold them.

This research builds on Schwartz’s Value Theory, which categorizes human values into dimensions like self-enhancement versus self-transcendence and openness to change versus conservation. The study specifically found that self-transcendence values, which focus on caring for and accepting others, are positively associated with the quality of romantic relationships. In contrast, values related to self-enhancement, such as seeking power or personal success, were linked to lower relationship quality. The findings underscore the importance of altruistic values in fostering a healthy and satisfying romantic partnership, highlighting how personal values play a crucial role in relationship dynamics.

Overall, the study provides valuable evidence that prioritizing self-transcendence values within romantic relationships can contribute to greater satisfaction and underscores the potential impact of personal values on the health and longevity of these relationships.

These studies, each shining a light on different facets of romantic relationships, collectively contribute to a deeper understanding of the psychology of love. By exploring the myriad factors that influence our connections with romantic partners, science offers valuable insights into the art of maintaining healthy, fulfilling relationships.

Symbiosexuality: New study validates attraction to established couples as a real phenomenon

New research sheds light on symbiosexuality, a phenomenon where individuals are attracted to the dynamics within the established relationships of others. This surprising and often overlooked form of attraction challenges traditional views on human desire.

Insecure attachment to fathers linked to increased mental health issues and alcohol use

Adolescents with insecure attachment to their fathers are more likely to develop internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms, which can lead to increased alcohol use. Attachment to mothers did not show a similar association with these outcomes.

How a woman dresses affects how other women view her male friendships, study suggests

Women who prefer male friends are often seen by other women as less trustworthy and more promiscuous, but dressing in a masculine way can reduce these perceptions, making them appear less of a romantic threat.

Women experience men’s orgasm as a femininity achievement, new study suggests

New research reveals that women often view a male partner's orgasm as a validation of their femininity, while the absence of it can feel like a failure, especially for those sensitive to traditional gender roles

Neuroscience uncovers unique brain bond between romantic partners

How do our brains react differently in love versus friendship? New research explores the neural dynamics that might explain the deeper emotional connection between romantic partners, offering fresh insights into the science of relationships.

Fear of being single, romantic disillusionment, dating anxiety: Untangling the psychological connections

A study found that fear of being single is associated with higher dating anxiety, while those seeking romantic relationships through online dating reported lower romantic disillusionment.

Study reveals evolving sexual attitudes in China, influenced by age, urban-rural divide, and political status

New research shows that while Chinese attitudes toward premarital sex and homosexuality have liberalized over time, views on extramarital sex remain conservative, with age, urbanization, and political status influencing these attitudes.

Women fail to spot heightened infidelity risk in benevolently sexist men, study finds

A new study shows both hostile and benevolent sexism in men are significant predictors of infidelity, with women often underestimating the infidelity risk posed by benevolently sexist men, mistaking their attitudes for commitment and protectiveness.

STAY CONNECTED

Mothers adhering to healthy dietary patterns at lower risk of having children with autism, gut health tied to psychological resilience: new research reveals gut-brain stress connection, new research shows dogs can smell your stress — and it affects their behavior, “intersectional hallucinations”: the ai flaw that could lead to dangerous misinformation, new psychology research links parental well-being to feeling valued, study finds little evidence linking violent video games to increased aggression in adolescents, surprisingly strong link found between political party affiliation and sleep quality.

- Privacy policy

- Terms and Conditions

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Add New Playlist

- Select Visibility - Public Private

- Cognitive Science Research

- Mental Health Research

- Social Psychology Research

- Drug Research

- Relationship Research

- About PsyPost

- Privacy Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Towards a Comprehensive Theory of Love: The Quadruple Theory

Scholars across an array of disciplines including social psychologists have been trying to explain the meaning of love for over a century but its polysemous nature has made it difficult to fully understand. In this paper, a quadruple framework of attraction, resonance or connection, trust, and respect are proposed to explain the meaning of love. The framework is used to explain how love grows and dies and to describe brand love, romantic love, and parental love. The synergistic relationship between the factors and how their variations modulate the intensity or levels of love are discussed.

Introduction

Scholars across an array of disciplines have tried to define the meaning and nature of love with some success but questions remain. Indeed, it has been described as a propensity to think, feel, and behave positively toward another ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 1986 ). However, the application of this approach has been unsuccessful in all forms of love ( Berscheid, 2010 ). Some social psychologists have tried to define love using psychometric techniques. Robert Sternberg Triangular Theory of Love and Clyde and Susan Hendrick’s Love Attitudes Scale (LAS) are notable attempts to employ the psychometric approach ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 1986 ; Sternberg, 1986 ). However, data analysis from the administration of the LAS, Sternberg’s scale and the Passionate Love Scale by Hatfield and Sprecher’s (1986) found a poor association with all forms of love ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 1989 ). Other studies have found a poor correlation between these and other love scales with different types of love ( Whitley, 1993 ; Sternberg, 1997 ; Masuda, 2003 ; Graham and Christiansen, 2009 ).

In recent years, the neuropsychological approach to study the nature of love has gained prominence. Research has compared the brain activity of people who were deeply in love while viewing a picture of their partner and friends of the same age using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and concluded that there is a specialized network of the brain involved in love ( Bartels and Zeki, 2000 ). Indeed, several lines of investigation using fMRI have described a specialized area of the brain mediating maternal love ( Noriuchi et al., 2008 ; Noriuchi and Kikuchi, 2013 ) and, fMRI studies have implicated multiple brain systems particularly the reward system in romantic love ( Aron et al., 2005 ; Fisher et al., 2005 , 2010 ; Beauregard et al., 2009 ). Brain regions including ventral tegmental area, anterior insula, ventral striatum, and supplementary motor area have been demonstrated to mediate social and material reward anticipation ( Gu et al., 2019 ). Although brain imaging provides a unique insight into the nature of love, making sense of the psychological significance or inference of fMRI data is problematic ( Cacioppo et al., 2003 ).

Also, there has been growing interests in the neurobiology of love. Indeed, evidence suggests possible roles for oxytocin, vasopressin, dopamine, serotonin, testosterone, cortisol, morphinergic system, and nerve growth factor in love and attachment ( Esch and Stefano, 2005 ; De Boer et al., 2012 ; Seshadri, 2016 ; Feldman, 2017 ). However, in many cases, definite proof is still lacking and the few imaging studies on love are limited by selection bias on the duration of a love affair, gender and cultural differences ( De Boer et al., 2012 ).

So, while advances have been made in unraveling the meaning of love, questions remain and a framework that can be employed to understand love in all its forms remains to be developed or proposed. The objective of this article is to propose a novel framework that can be applied to all forms of love.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development (The AAC Model)

In the past few decades, the psychological literature has defined and described different forms of love and from these descriptions, the role of attraction, attachment-commitment, and caregiving (AAC), appears to be consistent in all forms of love.

Attraction theory is one of the first approaches to explain the phenomenon of love and several studies and scholarly works have described the importance of attraction in different forms of love ( Byrne and Griffitt, 1973 ; Berscheid and Hatfield, 1978 ; Fisher et al., 2006 ; Braxton-Davis, 2010 ; Grant-Jacob, 2016 ). Attraction has been described as an evolutionary adaptation of humans for mating, reproduction, and parenting ( Fisher et al., 2002a , 2006 ).

The role of attachment in love has also been extensively investigated. Attachment bonds have been described as a critical feature of mammals including parent-infant, pair-bonds, conspecifics, and peers ( Feldman, 2017 ). Indeed, neural networks including the interaction of oxytocin and dopamine in the striatum have been implicated in attachment bonds ( Feldman, 2017 ). The key features of attachment include proximity maintenance, safety and security, and separation distress ( Berscheid, 2010 ). Multiple lines of research have proposed that humans possess an innate behavioral system of attachment that is essential in love ( Harlow, 1958 ; Bowlby, 1977 , 1988 , 1989 ; Ainsworth, 1985 ; Hazan and Shaver, 1987 ; Bretherton, 1992 ; Carter, 1998 ; Burkett and Young, 2012 ). Attachment is essential to commitment and satisfaction in a relationship ( Péloquin et al., 2013 ) and commitment leads to greater intimacy ( Sternberg, 1986 ).

Also, several lines of evidence have described the role of caregiving in love. It has been proposed that humans possess an inborn caregiving system that complements their attachment system ( Bowlby, 1973 ; Ainsworth, 1985 ). Indeed, several studies have used caregiving scale and compassionate love scale, to describe the role of caring, concern, tenderness, supporting, helping, and understanding the other(s), in love and relationships ( Kunce and Shaver, 1994 ; Sprecher and Fehr, 2005 ). Mutual communally responsive relationships in which partners attend to one another’s needs and welfare with the expectation that the other will return the favor when their own needs arise ( Clark and Mills, 1979 ; Clark and Monin, 2006 ), have been described as key in all types of relationships including friendship, family, and romantic and compassionate love ( Berscheid, 2010 ).

Attachment and caregiving reinforce each other in relationships. Evidence suggests that sustained caregiving is frequently accompanied by the growth of familiarity between the caregiver and the receiver ( Bowlby, 1989 , p. 115) strengthening attachment ( Berscheid, 2010 ). Several studies have proposed that attachment has a positive influence on caregiving behavior in love and relationships ( Carnelley et al., 1996 ; Collins and Feeney, 2000 ; Feeney and Collins, 2001 ; Mikulincer, 2006 ; Canterberry and Gillath, 2012 ; Péloquin et al., 2013 ).

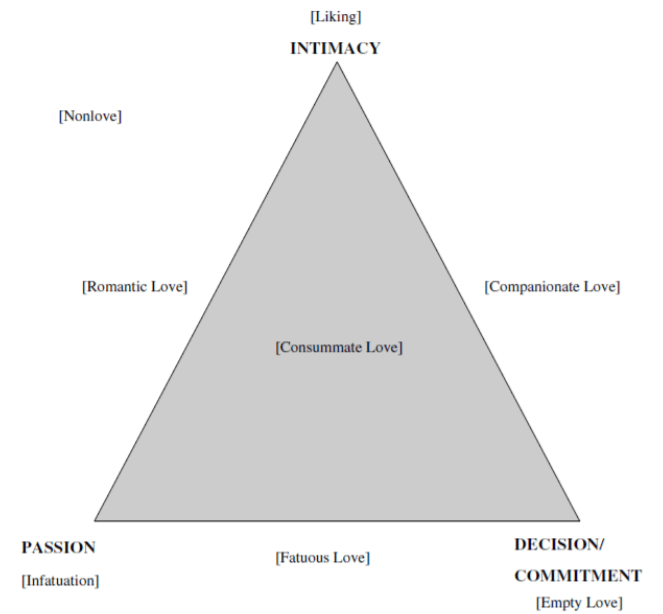

The AAC model can be seen across the literature on love. Robert Sternberg triangular theory of love which proposes that love has three components —intimacy, passion, and commitment ( Sternberg, 1986 ), essentially applies the AAC model. Passion, a key factor in his theory, is associated with attraction ( Berscheid and Hatfield, 1978 ), and many passionate behaviors including increased energy, focused attention, intrusive thinking, obsessive following, possessive mate guarding, goal-oriented behaviors and motivation to win and keep a preferred mating partner ( Fisher et al., 2002b , 2006 ; Fisher, 2005 ). Also, evidence indicates that attachment is central to intimacy, another pillar of the triangular theory ( Morris, 1982 ; Feeney and Noller, 1990 ; Oleson, 1996 ; Grabill and Kent, 2000 ). Commitment, the last pillar of the triangular theory, is based on interdependence and social exchange theories ( Stanley et al., 2010 ), which is connected to mutual caregiving and secure attachment.

Hendrick and Hendrick’s (1986) , Love Attitudes Scale (LAS) which measures six types of love ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 1986 ) is at its core based on the AAC model. Similarly, numerous works on love ( Rubin, 1970 ; Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ; Fehr, 1994 ; Grote and Frieze, 1994 ), have applied one or all of the factors in the ACC model. Berscheid (2010) , proposed four candidates for a temporal model of love including companionate love, romantic love, and compassionate love and adult attachment love. As described, these different types of love (romantic, companionate, compassionate, and attachment) all apply at least one or all of the factors in the AAC model.

New Theory (The Quadruple Framework)

The AAC model can be fully captured by four fundamental factors; attraction, connection or resonance, trust, and respect, providing a novel framework that could explain love in all its forms. Table 1 shows the core factors of love, and the four factors derived from them.

Factors of love.

| Core factors | Factors of love | Strengthening or driving factors | Behavioral traits |

| Attraction Attachment | Attraction | Physical attributes, personality, wealth, value, etc. | Passion, intimacy, commitment. |

| Attachment-Commitment Caregiving | Connection/resonance | Similarity, proximity, familiarity, positive shared experiences, interdependence, novelty. | Friendship, separation distress, worry, and concern, commitment and Intimacy, compassion or caregiving. |

| Attachment-Commitment Caregiving | Trust | Reliability, familiarity, mutual self-disclosures, positive shared experiences. | Intimacy, commitment, compassion or caregiving |

| Attachment-Commitment Caregiving | Respect | Reciprocal appreciation, admiration, consideration, concern for wellbeing, and tolerance | Commitment, intimacy, compassion or caregiving |

Evidence suggests that both attachment and attraction play a role in obsession or passion observed in love ( Fisher et al., 2005 ; Honari and Saremi, 2015 ). Attraction is influenced by the value or appeal perceived from a relationship and this affects commitment ( Rusbult, 1980 ).

Connection or Resonance

Connection is key to commitment, caregiving, and intimacy. It creates a sense of oneness in relationships and it is strengthened by proximity, familiarity, similarity, and positive shared experiences ( Sullivan et al., 2011 ; Beckes et al., 2013 ). Homogeneity or similarity has been observed to increase social capital and engagement among people ( Costa and Kahn, 2003a , b ), and it has been described as foundational to human relationships ( Tobore, 2018 , pp. 6–13). Research indicates that similarity plays a key role in attachment and companionship as people are more likely to form long-lasting and successful relationships with those who are more similar to themselves ( Burgess and Wallin, 1954 ; Byrne, 1971 ; Berscheid and Reis, 1998 ; Lutz-Zois et al., 2006 ). Proximity plays a key role in caregiving as people are more likely to show compassion to those they are familiar with or those closest to them ( Sprecher and Fehr, 2005 ). Similarity and proximity contribute to feelings of familiarity ( Berscheid, 2010 ). Also, caregiving and empathy are positively related to emotional interdependence ( Hatfield et al., 1994 ).

Trust is crucial for love ( Esch and Stefano, 2005 ) and it plays an important role in relationship intimacy and caregiving ( Rempel and Holmes, 1985 ; Wilson et al., 1998 ; Salazar, 2015 ), as well as attachment ( Rodriguez et al., 2015 ; Bidmon, 2017 ). Familiarity is a sine qua non for trust ( Luhmann, 1979 ), and trust is key to relationship satisfaction ( Simpson, 2007 ; Fitzpatrick and Lafontaine, 2017 ).

Respect is cross-cultural and universal ( Frei and Shaver, 2002 ; Hendrick et al., 2010 ) and has been described as fundamental in love ( Hendrick et al., 2011 ). It plays a cardinal role in interpersonal relations at all levels ( Hendrick et al., 2010 ). Indeed, it is essential in relationship commitment and satisfaction ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 2006 ) and relationship intimacy and attachment ( Alper, 2004 ; Hendrick et al., 2011 ).

Synergetic Interactions of the Four Factors

Connection and attraction.

Similarity, proximity, and familiarity are all important in connection because they promote attachment and a sense of oneness in a relationship ( Sullivan et al., 2011 ; Beckes et al., 2013 ). Research indicates that proximity ( Batool and Malik, 2010 ) and familiarity positively influence attraction ( Norton et al., 2015 ) and several lines of evidence suggests that people are attracted to those similar to themselves ( Sykes et al., 1976 ; Wetzel and Insko, 1982 ; Montoya et al., 2008 ; Batool and Malik, 2010 ; Collisson and Howell, 2014 ). Also, attraction mediates similarity and familiarity ( Moreland and Zajonc, 1982 ; Elbedweihy et al., 2016 ).

Respect and Trust

Evidence suggests that respect promotes trust ( Ali et al., 2012 ).

Connection, Respect, Trust, and Attraction

Trust affects attraction ( Singh et al., 2015 ). Trust and respect can mediate attitude similarity and promote attraction ( Singh et al., 2016 ).

So, although these factors can operate independently, evidence suggests that the weakening of one factor could negatively affect the others and the status of love. Similarly, the strengthening of one factor positively modulates the others and the status of love.

Relationships are dynamic and change as events and conditions in the environment change ( Berscheid, 2010 ). Love is associated with causal conditions that respond to these changes favorably or negatively ( Berscheid, 2010 ). In other words, as conditions change, and these factors become present, love is achieved and if they die, it fades. Figure 1 below explains how love grows and dies. Point C in the figure explains the variations in the intensity or levels of love and this variation is influenced by the strength of each factor. The stronger the presence of all factors, the higher the intensity and the lower, the weaker the intensity of love. The concept of non-love is similar to the “non-love” described in Sternberg’s triangular theory of love in which all components of love are absent ( Sternberg, 1986 ).

Description: (A) Presence of love (all factors are present). (B) Absence of love (state of non-love or state where all factors are latent or dormant). (C) Different levels of love due to variations in the four factors. (D) Movement from non-love toward love (developmental stage: at least one but not all four factors are present). (E) Movement away from love toward non-love (decline stage: at least one or more of the four factors are absent).

Application of the Quadruple Framework on Romantic, Brand and Parental Love

Romantic, parental and brand love have been chosen to demonstrate the role of these factors and their interactions in love because there is significant existing literature on them. However, they can be applied to understand love in all its forms.

Romantic Love

Attraction and romantic love.

Attraction involves both physical and personality traits ( Braxton-Davis, 2010 ; Karandashev and Fata, 2014 ). To this end, attraction could be subdivided into sexual or material and non-sexual or non-material attraction. Sexual or material attraction includes physical attributes such as beauty, aesthetics, appeal, wealth, etc. In contrast, non-sexual or non-material attraction includes characteristics such as personality, social status, power, humor, intelligence, character, confidence, temperament, honesty, good quality, kindness, integrity, etc. Both types of attraction are not mutually exclusive.

Romantic love has been described as a advanced form of human attraction system ( Fisher et al., 2005 ) and it fits with the passion component of Sternberg’s triangular theory of love which he described as the quickest to recruit ( Sternberg, 1986 ). Indeed, research indicates that physical attractiveness and sensual feelings are essential in romantic love and dating ( Brislin and Lewis, 1968 ; Regan and Berscheid, 1999 ; Luo and Zhang, 2009 ; Braxton-Davis, 2010 ; Ha et al., 2010 ; Guéguen and Lamy, 2012 ) and sexual attraction often provides the motivational spark that kickstarts a romantic relationship ( Gillath et al., 2008 ). Behavioral data suggest that love and sex drive follow complementary pathways in the brain ( Seshadri, 2016 ). Indeed, the neuroendocrine system for sexual attraction and attachment appears to work synergistically motivating individuals to both prefer a specific mating partner and to form an attachment to that partner ( Seshadri, 2016 ). Sex promotes the activity of hormones involved in love including arginine vasopressin in the ventral pallidum, oxytocin in the nucleus accumbens and stimulates dopamine release which consequently motivates preference for a partner and strengthens attachment or pair-bonding ( Seshadri, 2016 ).

Also, romantic love is associated with non-material attraction. Research indicates that many people are attracted to their romantic partner because of personality traits like generosity, kindness, warmth, humor, helpfulness, openness to new ideas ( Giles, 2015 , pp. 168–169). Findings from a research study on preferences in human mate selection indicate that personality traits such as kindness/considerate and understanding, exciting, and intelligent are strongly preferred in a potential mate ( Buss and Barnes, 1986 ). Indeed, character and physical attractiveness have been found to contribute jointly and significantly to romantic attraction ( McKelvie and Matthews, 1976 ).

Attraction is key to commitment in a romantic relationship ( Rusbult, 1980 ), indicating that without attraction a romantic relationship could lose its luster. Also, romantic attraction is weakened or declines as the reason for its presence declines or deteriorates. If attraction is sexual or due to material characteristics, then aging or any accident that compromises physical beauty would result in its decline ( Braxton-Davis, 2010 ). Loss of fortune or social status could also weaken attraction and increase tension in a relationship. Indeed, tensions about money increase marital conflicts ( Papp et al., 2009 ; Dew and Dakin, 2011 ) and predicted subsequent divorce ( Amato and Rogers, 1997 ).

Connection and Romantic Love

Connection or resonance fits with the intimacy, and commitment components of Sternberg’s triangular theory of love ( Sternberg, 1986 ). Connection in romantic love involves intimacy, friendship or companionship and caregiving and it is strengthened by novelty, proximity, communication, positive shared experiences, familiarity, and similarity. It is what creates a sense of oneness between romantic partners and it is expressed in the form of proximity seeking and maintenance, concern, and compassion ( Neto, 2012 ). Evidence suggests that deeper levels of emotional involvement or attachment increase commitment and cognitive interdependence or tendency to think about the relationship in a pluralistic manner, as reflected in the use of plural pronouns to describe oneself, romantic partner and relationship ( Agnew et al., 1998 ).

Research indicates that both sexual attraction and friendship are necessary for romantic love ( Meyers and Berscheid, 1997 ; Gillath et al., 2008 ; Berscheid, 2010 ), indicating that connection which is essential for companionship plays a key role in romantic love. A study on college students by Hendrick and Hendrick (1993) found that a significant number of the students described their romantic partner as their closest friend ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 1993 ), reinforcing the importance of friendship or companionship in romantic love.

Similarity along the lines of values, goals, religion, nationality, career, culture, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, language, etc. is essential in liking and friendship in romantic love ( Berscheid and Reis, 1998 ). Research indicates that a partner who shared similar values and interests were more likely to experience stronger love ( Jin et al., 2017 ). Indeed, the more satisfied individuals were with their friendships the more similar they perceived their friends to be to themselves ( Morry, 2005 ). Also, similarity influences perceptions of familiarity ( Moreland and Zajonc, 1982 ), and familiarity plays a role in the formation of attachment and connectedness because it signals safety and security ( Bowlby, 1977 ). Moreover, similarity and familiarity affect caregiving. Sprecher and Fehr (2005) , found compassion or caregiving were lower for strangers, and greatest for dating and marital relationships, indicating that similarity and familiarity enhance intimacy and positively influences caregiving ( Sprecher and Fehr, 2005 ).

Proximity through increased exposure is known to promote liking ( Saegert et al., 1973 ), familiarity and emotional connectedness ( Sternberg, 1986 ; Berscheid, 2010 ). Exposure through fun times and direct and frequent communication is essential to maintaining and strengthening attachment and connectedness ( Sternberg and Grajek, 1984 ). In Sternberg’s triangular theory, effective communication is described as essential and affects the intimacy component of a relationship ( Sternberg, 1986 ). Indeed, intimacy grows from a combination of mutual self-disclosure and interactions mediated by positive partner responsiveness ( Laurenceau et al., 1998 , 2005 ; Manne et al., 2004 ), indicating that positive feedback and fun times together strengthens connection.

Also, sexual activity is an important component of the reward system that reinforces emotional attachment ( Seshadri, 2016 ), indicating that sexual activity may increase emotional connectedness and intimacy. Over time in most relationships, predictability grows, and sexual satisfaction becomes readily available. This weakens the erotic and emotional experience associated with romantic love ( Berscheid, 2010 ). Research shows that a reduction in novelty due to the monotony of being with the same person for a long period is the reason for this decline in sexual attraction ( Freud and Rieff, 1997 , p. 57; Sprecher et al., 2006 , p. 467). According to Sternberg (1986) , the worst enemy of the intimacy component of love is stagnation. He explained that too much predictability can erode the level of intimacy in a close relationship ( Sternberg, 1986 ). So, novelty is essential to maintaining sexual attraction and strengthening connection in romantic love.

Jealousy and separation distress which are key features of romantic love ( Fisher et al., 2002b ), are actions to maintain and protect the emotional union and are expressions of a strong connection. Research has found a significant correlation between anxiety and love ( Hatfield et al., 1989 ) and a positive link between romantic love and jealousy in stable relationships ( Mathes and Severa, 1981 ; Aune and Comstock, 1991 ; Attridge, 2013 ; Gomillion et al., 2014 ). Indeed, individuals who feel strong romantic love tend to be more jealous or sensitive to threats to their relationship ( Orosz et al., 2015 ).

Connection in romantic love is weakened by distance, a dearth of communication, unsatisfactory sexual activity, divergences or dissimilarity of values and interests, monotony and too much predictability.

Trust and Romantic Love

Trust is the belief that a partner is, and will remain, reliable or dependable ( Cook, 2003 ). Trust in romantic love fits with the intimacy, and commitment components of Sternberg’s triangular theory of love which includes being able to count on the loved one in times of need, mutual understanding with the loved one, sharing of one’s self and one’s possessions with the loved one and maintaining the relationship ( Sternberg, 1986 ).