Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 29 August 2022

Measuring inequality beyond the Gini coefficient may clarify conflicting findings

- Kristin Blesch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6241-3079 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Oliver P. Hauser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9282-0801 4 , 5 &

- Jon M. Jachimowicz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1197-8958 6

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 1525–1536 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3745 Accesses

22 Citations

150 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social policy

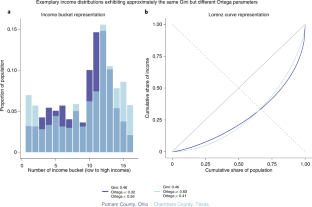

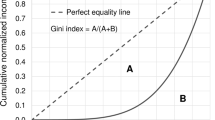

Prior research has found mixed results on how economic inequality is related to various outcomes. These contradicting findings may in part stem from a predominant focus on the Gini coefficient, which only narrowly captures inequality. Here, we conceptualize the measurement of inequality as a data reduction task of income distributions. Using a uniquely fine-grained dataset of N = 3,056 US county-level income distributions, we estimate the fit of 17 previously proposed models and find that multi-parameter models consistently outperform single-parameter models (i.e., models that represent single-parameter measures like the Gini coefficient). Subsequent simulations reveal that the best-fitting model—the two-parameter Ortega model—distinguishes between inequality concentrated at lower- versus top-income percentiles. When applied to 100 policy outcomes from a range of fields (including health, crime and social mobility), the two Ortega parameters frequently provide directionally and magnitudinally different correlations than the Gini coefficient. Our findings highlight the importance of multi-parameter models and data-driven methods to study inequality.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

A simple method for measuring inequality

GEOWEALTH-US: Spatial wealth inequality data for the United States, 1960–2020

A simple method for estimating the Lorenz curve

Data availability.

All data to reproduce the findings discussed in this paper are available at http://www.measuringinequality.com/ .

Code availability

All code to reproduce the findings discussed in this paper are available at http://www.measuringinequality.com/ .

Davies, J., Lluberas, R. & Shorrocks, A. in Credit Suisse Wealth Report 1–157 (Credit Suisse, 2016); https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/global-wealth-databook-2016.pdf

Cornia, G. A. Falling Inequality in Latin America: Policy Changes and Lessons (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (Bloomsbury, 2011).

Pickett, K. E., Kelly, S., Brunner, E., Lobstein, T. & Wilkinson, R. G. Wider income gaps, wider waistbands? An ecological study of obesity and income inequality. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 59 , 670–674 (2005).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kim, D., Wang, F. & Arcan, C. Geographic association between income inequality and obesity among adults in New York State. Prev. Chronic Dis. 15 , E123 (2018).

Ngamaba, K., Panagioti, M. & Armitage, C. Income inequality and subjective well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 27 , 577–596 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Côté, S., House, J. & Willer, R. High economic inequality leads higher-income individuals to be less generous. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 15838–15843 (2015).

Schmukle, S. C., Korndörfer, M. & Egloff, B. No evidence that economic inequality moderates the effect of income on generosity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 9790–9795 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

De Maio, F. Income inequality measures. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 61 , 849–852 (2007).

Tackling High Inequalities Creating Opportunities for All (OECD, 2014); https://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/Tackling-high-inequalities.pdf

Hearing document: Congress must act to reduce inequality for working families. In Hearing before the Committee on the Budget House of Representatives Congress Hearing No. 116-14 (116th Congress, 2019); https://budget.house.gov/sites/democrats.budget.house.gov/files/documents/Inequality%20Post%20Hearing%20Report_Final.pdf

Charles-Coll, J. Understanding income inequality: concept, causes and measurement. Int. J. Econ. Manage. Sci. 1 , 17–28 (2011).

Google Scholar

Giorgi, G. & Gigliarano, C. The Gini concentration index: a review of the inference literature. J. Econ. Surv. 31 , 1130–1148 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Sitthiyot, T. & Holasut, K. A simple method for measuring inequality. Palgrave Commun. 6 , 112 (2020).

Gini Index (World Bank, 2021); https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI

Cowell, F. in Handbook of Income Distribution (eds Atkinson, A. & Bourguignon, F.), Ch. 2 (Elsevier, 2000).

Liu, Y. & Gastwirth, J. L. On the capacity of the Gini index to represent income distributions. METRON 78 , 61–69 (2020).

Fellman, J. Income inequality measures. Theor. Econ. Lett. 08 , 557–574 (2018).

Clementi, F., Gallegati, M., Gianmoena, L., Landini, S. & Stiglitz, J. Mis-measurement of inequality: a critical reflection and new insights. J. Econ. Interact. Coord. 14 , 891–921 (2019).

Atkinson, A. & Bourguignon, F. Handbook of Income Distribution 1st edn, Vol. 1 (Elsevier, 2000); https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:income:1

Davies, J., Hoy, M. & Zhao, L. Revisiting comparisons of income inequality when Lorenz curves intersect. Soc. Choice Welfare 58 , 101–109 (2022).

Davydov, Y. & Greselin, F. Comparisons between poorest and richest to measure inequality. Sociol. Methods Res. 49 , 526–561 (2020).

Atkinson, A. B. On the measurement of inequality. J. Econ. Theory 2 , 244–263 (1970).

Zanardi, G. Della asimmetria condizionata delle curve di concentrazione. lo scentramento. Riv. Ital. Econ. Demogr. Stat. 18 , 431–466 (1964).

Gwatkin, D. Health inequalities and the health of the poor: what do we know? What can we do? Bull. World Health Organ. 78 , 3–18 (2000).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ortega, P., Martín, G., Fernández, A., Ladoux, M. & García, A. A new functional form for estimating Lorenz curves. Rev. Income Wealth 37 , 447–452 (1991).

De Dominicis, L., Florax, R. J. & De Groot, H. L. A meta-analysis on the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. Scott. J. Polit. Econ. 55 , 654–682 (2008).

Kondo, N. et al. Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: meta-analysis of multilevel studies. Br. Med. J. 339 , 1178–1181 (2009).

American Community Survey, 2011–2015: 5-Year Period Estimates (US Census Bureau, 2016); https://data2.nhgis.org/main

Chetty, R. et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA 315 , 1750–1766 (2016).

Chetty, R. & Hendren, N. The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility II: county-level estimates. Q. J. Econ. 133 , 1163–1228 (2018).

Abdi, H. Bonferroni and Šidák corrections for multiple comparisons. Encycl. Meas. Stat. 3 , 103–107 (2007).

Abdullah, A., Doucouliagos, H. & Manning, E. Does education reduce income inequality? A meta-regression analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 29 , 301–316 (2015).

Hauser, O. P. & Norton, M. I. (Mis)perceptions of inequality. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 18 , 21–25 (2017).

Knell, M. & Stix, H. Perceptions of inequality. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 65 , S0176268020300756 (2020).

Phillips, L. T. et al. Inequality in people’s minds. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/vawh9 (2020).

Jachimowicz, J. M. et al. Inequality in researchers’ minds: four guiding questions for studying subjective perceptions of economic inequality. J. Econ. Surv. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12507 (2022).

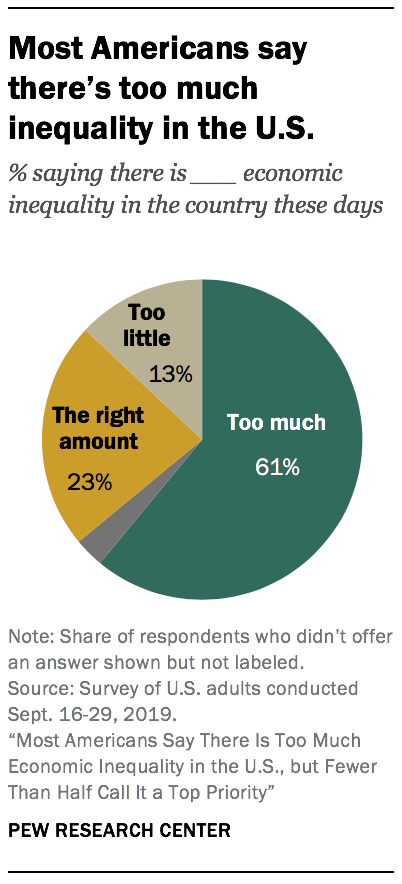

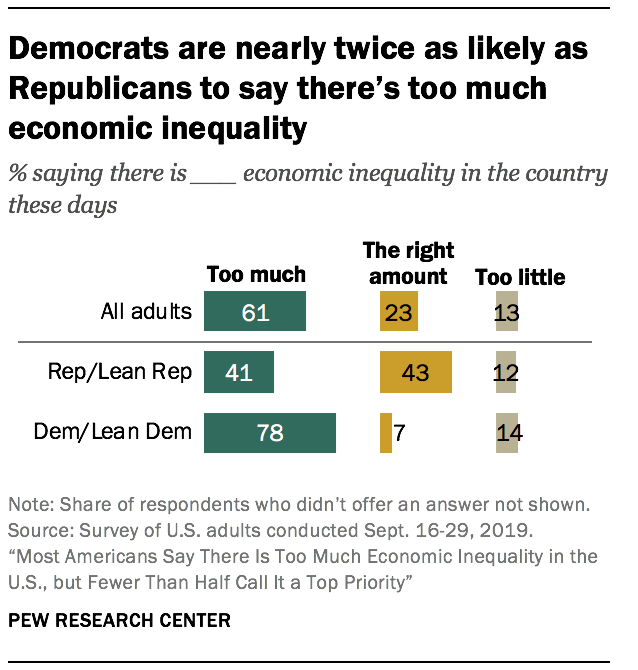

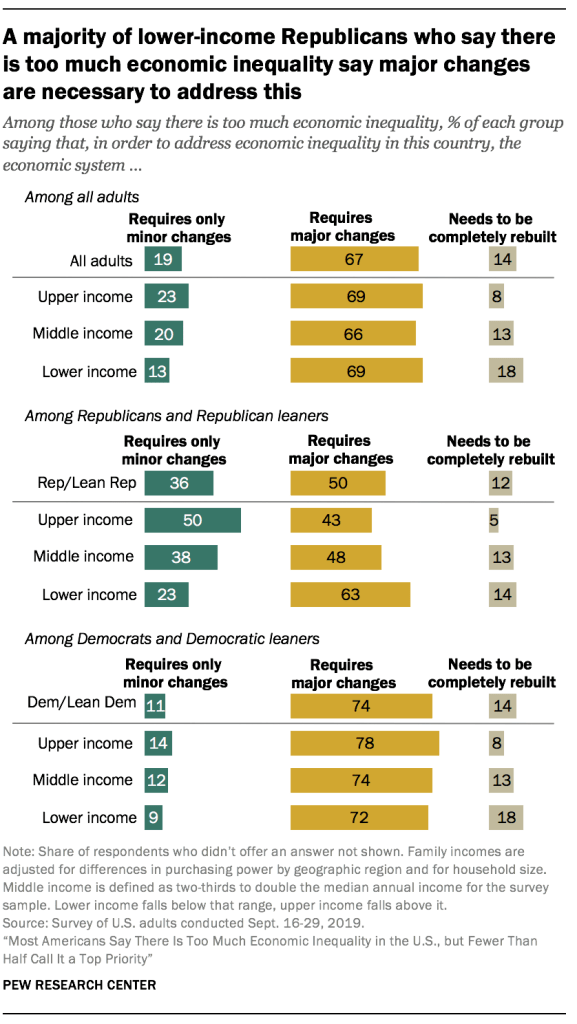

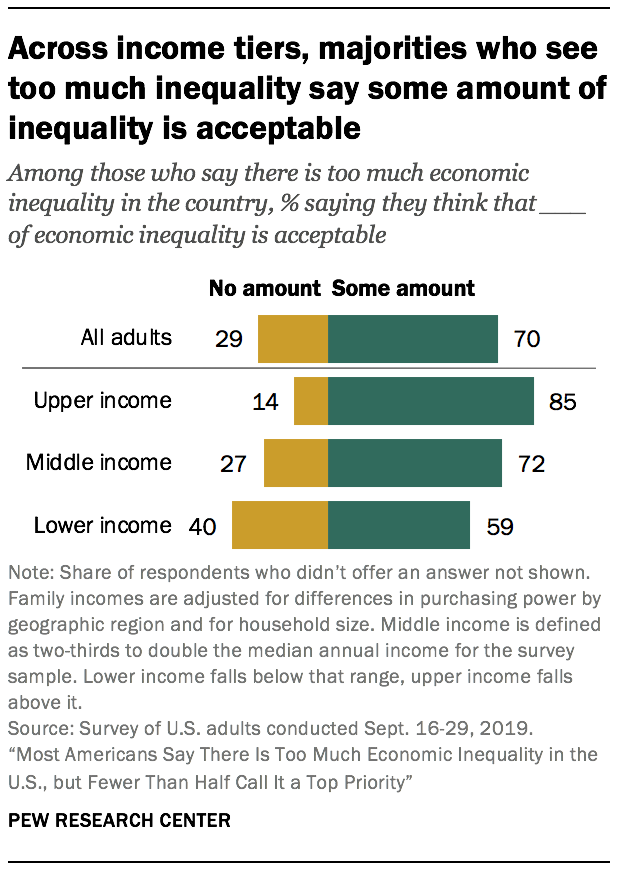

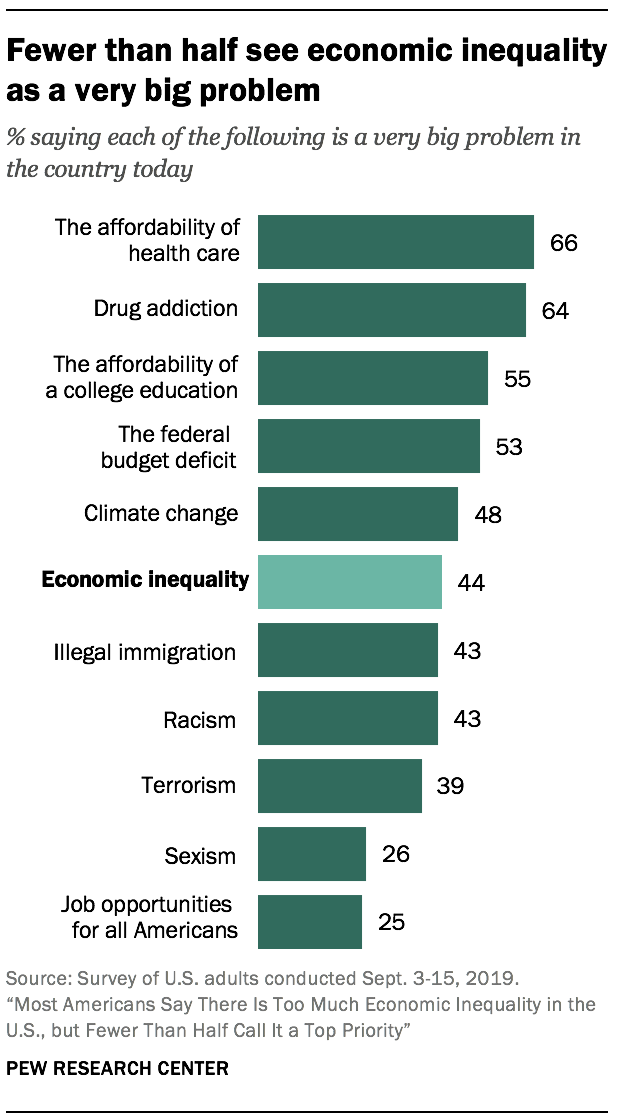

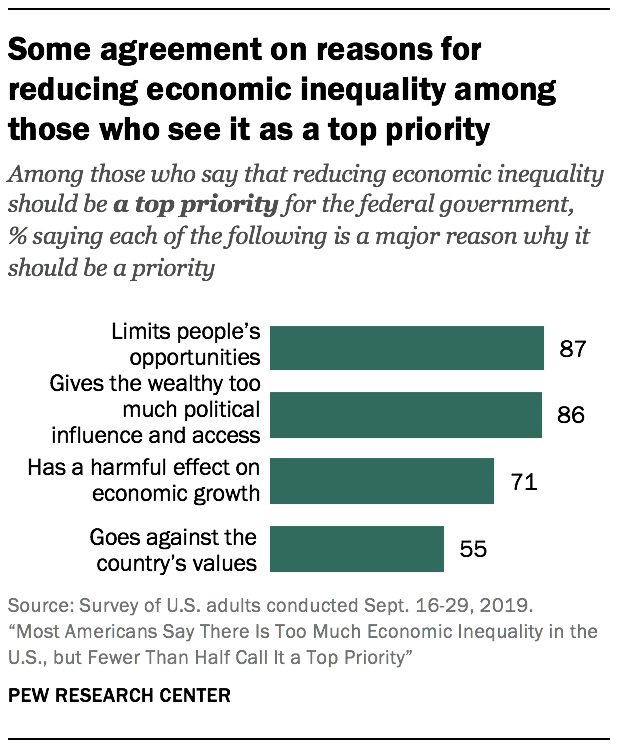

Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call It a Top Priority (Pew Research Center, 2020); https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/01/PSDT_01.09.20_economic-inequailty_FULL.pdf

Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., Lundberg, K. B. & McKee, S. E. Economic inequality and socioeconomic ranking inform attitudes toward redistribution. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 96 , 104180 (2021).

Income Share Held by Highest 20% (World Bank, 2021); https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.DST.05TH.20

Cowell, F. Measuring Inequality 3rd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011); https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oxp:obooks:9780199594047

Campano, F. & Salvatore, D. Income Distribution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2006); https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oxp:obooks:9780195300918

Slottje, D. J. Using grouped data for constructing inequality indices: parametric vs. non-parametric methods. Econ. Lett. 32 , 193–197 (1990).

Jorda, V., Sarabia, J. M. & Jäntti, M. Inequality measurement with grouped data: parametric and non-parametric methods. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 184 , 964–984 (2021).

Gastwirth, J. L. A general definition of the Lorenz curve. Econometrica 39 , 1037–1039 (1971).

Krause, M. Parametric Lorenz curves and the modality of the income density function. Rev. Income Wealth 60 , 905–929 (2014).

Basmann, R., Hayes, K., Slottje, D. & Johnson, J. A general functional form for approximating the Lorenz curve. J. Econ. 43 , 77–90 (1990).

Kakwani, N. On a class of poverty measures. Econometrica 48 , 437–446 (1980).

Chotikapanich, D. & Griffiths, W. E. Estimating Lorenz curves using a Dirichlet distribution. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 20 , 290–295 (2002).

Paul, S. & Shankar, S. An alternative single parameter functional form for Lorenz curve. Empir. Econ. 59 , 1393–1402 (2020).

Sommeiller, E., Price, M. & Wazeter, E. Income Inequality in the US by State, Metropolitan Area, and County Tech. Rep. (EPI, 2016); https://www.epi.org/publication/income-inequality-in-the-us/#epi-toc-1

Sugiura, N. Further analysts of the data by Akaike’ s information criterion and the finite corrections. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 7 , 13–26 (1978).

Hurvich, C. M. & Tsai, C.-L. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika 76 , 297–307 (1989).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 19 , 716–723 (1974).

Brams, S. J. & Fishburn, P. C. in Handbook of Social Choice and Welfare Vol. 1 (eds Arrow, K. J. et al.) 173–236 (Elsevier, 2002); http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S157401100280008X

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33 , 261–304 (2004).

Sarabia, J. M., Castillo, E. & Slottje, D. An ordered family of Lorenz curves. J. Econ. 91 , 43–60 (1999).

Benhabib, J. & Bisin, A. Skewed wealth distributions: theory and empirics. J. Econ. Lit. 56 , 1261–1291 (2018).

Jenkins, S. P. Pareto models, top incomes and recent trends in UK income inequality. Economica 84 , 261–289 (2017).

Arnold, B. C. Pareto Distribution (American Cancer Society, 2015); https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat01100.pub2

Kakwani, N. C. & Podder, N. On the estimation of Lorenz curves from grouped observations. Int. Econ. Rev. 14 , 278–292 (1973).

Rasche, R. H., Gaffney, J., Koo, A. Y. C. & Obst, N. Functional forms for estimating the Lorenz curve. Econometrica 48 , 1061–1062 (1980).

Chotikapanich, D. A comparison of alternative functional forms for the Lorenz curve. Econ. Lett. 41 , 129–138 (1993).

Abdalla, I. M. & Hassan, M. Y. Maximum likelihood estimation of Lorenz curves using alternative parametric model. Metodoloski Zv. 1 , 109–118 (2004).

Rohde, N. An alternative functional form for estimating the Lorenz curve. Econ. Lett. 105 , 61–63 (2009).

Wang, Z., Ng, Y.-K. & Smyth, R. A general method for creating Lorenz curves. Rev. Income Wealth 57 , 561–582 (2011).

Arnold, B. C. & Sarabia, J. M. Majorization and the Lorenz Order with Applications in Applied Mathematics and Economics 1st edn (Springer International, 2018).

Kleiber, C. & Kotz, S. A characterization of income distributions in terms of generalized Gini coefficients. Soc. Choice Welfare 19 , 789–794 (2002).

Dagum, C. Wealth distribution models: analysis and applications. Statistica 3 , 235–268 (2006).

McDonald, J. Some generalized functions for the size distribution of income. Econometrica 52 , 647–663 (1984).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Bhatia, S. Davidai, T. Graeber and J. Tan for helpful discussions and comments that substantially improved this paper; I. Zahn for technical support; and M. Kalisch for his advice on statistics. We also acknowledge funding from the German Academic Scholarship Foundation (to K.B.), Harvard Business School (to J.M.J.), University of Exeter Business School (to O.P.H.) and the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (to O.P.H.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Seminar for Statistics, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Kristin Blesch

Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research & Epidemiology—BIPS, Bremen, Germany

Department of Economics, University of Exeter Business School, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Oliver P. Hauser

Behavioural and Experimental Data Science, Institute for Data Science and Artificial Intelligence, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Organizational Behavior Unit, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA

Jon M. Jachimowicz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

K.B. led the data collection and statistical analysis under the supervision of J.M.J. and O.P.H. All authors wrote and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Kristin Blesch , Oliver P. Hauser or Jon M. Jachimowicz .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Human Behaviour thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Figs. 1–24, Tables 1–11, Methods and Results.

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Blesch, K., Hauser, O.P. & Jachimowicz, J.M. Measuring inequality beyond the Gini coefficient may clarify conflicting findings. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 1525–1536 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01430-7

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2021

Accepted : 13 July 2022

Published : 29 August 2022

Issue Date : November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01430-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Standard deviation vs. gini coefficient: effects of different indicators of classroom status hierarchy on bullying behavior.

- Sarah T. Malamut

- Achiel Fenneman

- Claire F. Garandeau

Journal of Youth and Adolescence (2024)

A statistical examination of wealth inequality within the Forbes 400 richest families in the United States from 2000 to 2023

- Joseph L. Gastwirth

- Richard Luo

METRON (2024)

Subjective socioeconomic status and income inequality are associated with self-reported morality across 67 countries

- Christian T. Elbæk

- Panagiotis Mitkidis

- Tobias Otterbring

Nature Communications (2023)

Perceptions of Income Inequality and Women’s Intrasexual Competition

- Abby M. Ruder

- Gary L. Brase

- Sydni A. J. Basha

Human Nature (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Tracking the impact of COVID-19 on economic inequality at high frequency

Contributed equally to this work with: Oriol Aspachs, Ruben Durante, Alberto Graziano, Josep Mestres, Marta Reynal-Querol, Jose G. Montalvo

Roles Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Caixabank Research, Caixabank, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft

Affiliations Department of Economics and Business, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, ICREA, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, Institute for Political Economy and Governance (IPEG), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, Barcelona Graduate School of Economics (BGSE), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Software

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft

Roles Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Economics and Business, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, Institute for Political Economy and Governance (IPEG), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, Barcelona Graduate School of Economics (BGSE), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

- Oriol Aspachs,

- Ruben Durante,

- Alberto Graziano,

- Josep Mestres,

- Marta Reynal-Querol,

- Jose G. Montalvo

- Published: March 31, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121

- Reader Comments

Pandemics have historically had a significant impact on economic inequality. However, official inequality statistics are only available at low frequency and with considerable delay, which challenges policymakers in their objective to mitigate inequality and fine-tune public policies. We show that using data from bank records it is possible to measure economic inequality at high frequency. The approach proposed in this paper allows measuring, timely and accurately, the impact on inequality of fast-unfolding crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Applying this approach to data from a representative sample of over three million residents of Spain we find that, absent government intervention, inequality would have increased by almost 30% in just one month. The granularity of the data allows analyzing with great detail the sources of the increases in inequality. In the Spanish case we find that it is primarily driven by job losses and wage cuts experienced by low-wage earners. Government support, in particular extended unemployment insurance and benefits for furloughed workers, were generally effective at mitigating the increase in inequality, though less so among young people and foreign-born workers. Therefore, our approach provides knowledge on the evolution of inequality at high frequency, the effectiveness of public policies in mitigating the increase of inequality and the subgroups of the population most affected by the changes in inequality. This information is fundamental to fine-tune public policies on the wake of a fast-moving pandemic like the COVID-19.

Citation: Aspachs O, Durante R, Graziano A, Mestres J, Reynal-Querol M, Montalvo JG (2021) Tracking the impact of COVID-19 on economic inequality at high frequency. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0249121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121

Editor: Shihe Fu, Xiamen University, CHINA

Received: September 18, 2020; Accepted: March 11, 2021; Published: March 31, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Aspachs et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data cannot be shared publicly because they are owned by a third-party commercial bank (Caixabank), and there are legal restrictions to their use. The Legal Services of the bank accepted the use of the microdata only to researchers belonging to their Research Unit. Therefore, the researchers of the team that did not belong to Caixabank Research could not access the microdata. They contributed with the conceptualization of the research, the writing of code, the proposal of different empirical exercises and the writing of the manuscript. Data can be made available by Caixabank Research (contact via [email protected] ) to professional researchers who meet the criteria to access confidential data. Researchers interested in obtaining access to the data are required to submit a written application to Caixabank Research with a detailed research proposal consisting in a research question and motivation, information on the researcher CV, and a detailed explanation of the data needed, and the aggregation criteria to protect the anonymity of the registers. The authors will provide assistance to any researcher willing to analyze the data for replication purposes.

Funding: JGM & MRQ: ECO2017-82696P, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation ( http://www.ciencia.gob.es/ ); CEX 2019-000915S Severo Ochoa Program for Centers of Excellence ( http://www.ciencia.gob.es/ ). The Research Department of CaixaBank provided support in the form of salaries for authors OA, AG and, JM. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section. JGM, MRQ and RD acknowledge the financial support of the "Ayudas Fundación BBVA a Equipos de Investigación Científica SARS-CoV-2 y COVID-19.” The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: OA, AG, and JM are employees of the Research Department of CaixaBank. There are no patents, products in development or marketed products to declare. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a massive impact on economic activity around the globe. To tackle the economic consequences of the pandemic, most governments have used a combination of family income support and credit facilities for firms. In particular, expanded unemployment insurance and furlough schemes have been adopted to stabilize the income of the workers, and contain the impact of the crisis on consumption and economic inequality. The concern is that a surge in inequality may erode social cohesion and spur support for populist or even undemocratic views.

Yet, how appropriate and effective these policies are remains unclear, mainly due to a lack of reliable indicators allowing to track economic activity at a fine temporal resolution. Indeed, most official statistics on inequality are available only at yearly frequency and often with long delays. This limits the ability of policymakers to rapidly adjust their responses in the effort to “flatten the recession curve” [ 1 ] after flattening the infection curve.

The COVID-19 has pushed new international initiatives to track economic activity in real time [ 2 – 6 ]. Researchers analyze the impact of economic stimulus packages to mitigate the effect of the COVID-19 epidemic on economic activity using high-frequency administrative data. Two examples are the effect on aggregate employment of the Paycheck Protection Program of the US [ 7 ] or the effect on consumption of the stimulus checks sent by the US Administration [ 8 ] using the data from financial aggregation and service apps [ 9 – 12 ].

One characteristic aspect of pandemics is their impact on inequality [ 13 , 14 ]. However, official inequality measures are calculated with long lags and low frequency. In the context of a fast-moving pandemic it is important to have a high-frequency measure of inequality to evaluate the mitigating effect of policy measures. This is particularly important in countries, like Spain, that suffered very intensively the financial crisis of 2008 and that have experienced an important increase in inequality since then. This process increased the support for populist parties, which in 2008 were not represented in the parliament and in 2020 accounted for 32.8% of the representatives in Congress. It is interesting to notice that inequality increased significantly from 2008 to 2012 but the process of growing political representation of populist parties happens mostly after 2013, even though inequality was decreasing since 2013. This seems to imply that there may be a threshold level of inequality that, once overcome, can trigger a set of popular grievances that persist over time, generating increasing support for populist parties. Therefore, a further increase in inequality, even in the short run, could imply reaching a level of inequality above the threshold that triggers future tension and political unrest. It could also ignite a process of increasing support for populist parties that could easily produce a significant deterioration of the institutional stability. Ultimately, this could have a long run effect on economic performance.

This paper uses bank account data and proposes a methodology to track the impact of government policies on inequality immediately after they are taken. Inequality is a multifaceted object and can concern dimensions as different as income, wealth, education etc. Our analysis focuses on wage inequality which, in countries with a high proportion of wage-earners, is a very precise indicator of overall income inequality (as we document for Spain). We do not look at wealth inequality mainly because, using information from just one financial institution, there is a high risk of not gauging a complete picture of the financial holdings of an individual. Bank account data have many advantages to study the effect of policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. They provide timely and reliable information on wages and government benefits. Being able to use very granular data, and to construct a high-frequency measure of inequality, allows to tailor policies to contain the increase of inequality in general, and by subgroups of the population classified by income level, gender, age, and county of birth.

Recent research has also used bank account data to study the evolution of different macro-magnitudes at very high frequency and, in particular, the effects of the pandemic on consumption [ 15 – 17 ]. Our contribution to this literature is threefold. First, and opposite to many papers in this literature [ 9 , 10 ], our sample is very representative of the population of Spanish wage-earners. As we show in next section, the distribution by gender and age are almost identical to the figures reported by the National Statistical Office. Second, and in contrast with a large part of the literature that uses banks accounts data, we are not analyzing the evolution of expenditure but the changes in the distribution of wages over time. Finally, the papers that have data on expenditure and income, like [ 16 ], deal with the issue of the sensitivity of consumption to income and do not consider the evolution of inequality, which is our basic objective.

We study empirically the evolution of inequality, before and after considering government support, comparing the period before the lockdown with the lockdown stage. We apply this methodology to data from a large Spanish bank. Spain is one of the countries most affected by the pandemic not only in terms of the number of people infected, but also regarding the economic impact. The comparison of the situation before and after the activation of the new policies of income support allows analyzing the effect of government interventions in the mitigation of inequality.

Using these bank account data, and our research design, we find that the largest impact of COVID-19 on inequality is transmitted through the movement of the distribution of salary changes among low wage earners. Second, we also find that most of the increase of inequality in the period after the beginning of the pandemic is mitigated by the action of the new extended unemployment benefits and furlough schemes activated by the government. There are no other changes in other government benefits during the period of analysis. We provide further details on the public income measures to support workers in the next section. Third we show that the policy response could not fully mitigate the large increase in inequality among young people and foreign-born individuals.

Materials and methods

We study the effect of COVID-19 on inequality using bank account data from CaixaBank, the second largest Spanish bank. Caixabank had monthly records on more than 3 million wage earners in 2020, and accounted for 27.1% of the wages, salaries and benefits deposited monthly in the Spanish financial sector. In Spain, differently from other countries like the US, the payment of the salaries or benefits using checks is a very rare event. Almost all the payments of salaries and benefits use direct deposits on bank accounts.

The wages and government benefits recorded by CaixaBank provide a large, precise and granular data source. Banks’ administrative data avoid most of the problems of surveys: there are no measurement errors or imperfect recollection mistakes, and they are obtained with short delays compared to surveys. For instance, the CaixaBank data provides the universe of wages through June 15, 2020 while the latest official measure of wage inequality in Spain, produced by the National Institute of Statistics, was published at the end of June of 2020, but referred to the situation in 2018.

The granularity of CaixaBank data allows also calculating inequality for subgroups of the population. Unlike other financial institutions, such as digital banks and personal finance management software, CaixaBank collects demographic information directly (gender, age, province, country of birth). We also provide a methodology to calculate monthly Gini indices and Lorentz curves, before and after accounting for public benefits, to analyze if the schemes to support workers temporarily out of the labor market are being effective at containing inequality.

The raw data are the wages and salaries deposited monthly at CaixaBank, and they present some challenges in order to construct wage inequality measures. We restrict our sample to accounts with either only one account holder or with multiple account co-holders but only one employer paying-in wages. This way, we ensure that payrolls or transfers recorded correspond to only one individual and avoid recording multiple payrolls or transfers from multiple account holders. In addition, we exclude from the sample those individuals who died during our period of study or who did not use the bank account for their usual financial transactions during the period. Finally, to ensure some stability on the sample of individuals studied, we require observing either wages or government benefits during two months (that is, in December 2019 and in January 2020) prior to the beginning of the period of study (February 2020). The S1 File explains all the details of our methodology to select the data.

Our reference sample includes individuals aged 16-64 who received either wages or unemployment benefits in December of 2019 and January of 2020. We follow those individuals in the months starting in February 2020. Since our main source of data is related with holding a bank account it is important to start analyzing the level of financial inclusion in Spain. The data of the Global Findex, the index of financial inclusion of the World Bank, shows that 97.6% of Spanish people over 15 years old holds a bank account when the average in high income countries is 93.7%.

We exclude the self-employed from our sample since it is difficult to calculate their net monthly income from bank account data: they receive payments from many different sources, and it is complicated to calculate expenses associated with their business. However, it is important to note that the proportion of wage earners among the Spanish working population was 84.4% in the first quarter of 2020 (Labor Force Survey of Spain, EPA). The relevance of wages as the main source of income can also be seen in the similarity of the inequality measures using income or gross wages. For instance, for the last period for which both measures are available, income inequality in Spain, measured by the Gini index, was 0.345 while wage inequality was 0.343.

Since most of the individuals in the sample are workers, to analyze its representativeness in terms of the distribution of wages we compare our data with the data of the latest Spanish National Statistical Office’s Wage Survey (Encuesta de Estructura Salarial, EES). For this purpose we consider the individuals in our sample who were working in February of 2020. First, we compare the distribution of individuals by gender and age with other sources. Table 1 summarizes the comparisons. In general, samples from digital banks and financial aggregation services have more young males than the general population. This is not the case with large and diversified traditional banks like our data source, CaixaBank. Table 1 shows that the gender and age distribution of our data is very similar to the working population.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.t001

In our sample, 54% of the individuals are male. This compares satisfactorily with the 52% of males in the sample of the last official survey (EES). In order to compare with more recent estimates, columns 3 and 4 include the proportions of males among employees in the Labor Force Survey of the last quarter of 2019 and first quarter of 2020. February of 2020 is between the last quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020. The proportion of males is identical to the one in the EES and very close to the one in our sample. With respect to age, we also find that the proportions of workers in each age bracked in our sample are very similar to those reported in the EES and the EPA.

Fig 1 shows the distribution of the monthly wages of our sample compared with the distribution of monthly net salaries in the EES. The wages received by workers in their bank accounts are net of payroll taxes. In order to compare our data with the EES we have calculated the distribution of net salaries transforming the gross salaries of the EES into net salaries by subtracting social insurance payments and taxes withheld. The S1 File includes a detailed explanation of this transformation. Since there is a time difference between the last EES available and our data we have adjusted the wages by moving the whole distribution by the increase in the average wage since the last available EES. We can see that the histogram of the net wages of our sample is very well adjusted by the density estimation of the adjusted distribution of net salaries in the official wage survey. Both distributions are remarkably similar. The similarity of the distribution of wages, and also the characteristics of the workforce, confirms the representativeness of our sample.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.g001

Since the distributions are so similar it is not surprising to see that the quantile ratios used regularly to describe inequality are very similar in both distributions as shown in S1 Table in S1 File .

Government support schemes for workers

The public policy response to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Spain has been large, as in most developed countries. For a detailed description of the economic impact of COVID-19 on the Spanish economy and the public policy reaction see [ 18 ]. The Spanish government has deployed income and liquidity support measures that are expected to reach 3.7% of GDP in discretionary measures and around 15.6% of GDP in off-budget measures [ 19 ].

Income measures to support workers have consisted mostly in the deployment of a furlough scheme (“Expediente de Regulación Temporal de Empleo”, or ERTEs) that was scarcely used until then. This scheme consists in a temporary job suspension (or a reduction in working hours) that avoids dismissals while maintaining the employment relationship. The Spanish government facilitated the use of this ERTE scheme due to COVID-19 (considering coronavirus as a force majeure, etc.) and increased coverage to all workers affected by a temporary job suspension. In addition, the benefits received did not reduce future unemployment benefit entitlements.

In addition to the job retention scheme, the government facilitated and extended the coverage of unemployment benefits. Regular unemployment benefits require a minimum of 360 days of contract employment in the previous 6 years and its duration is proportional to the amount of time worked (up to 18 months). Due to the pandemic, however, special unemployment subsidies were created for those who exhausted their unemployment benefits.

Those workers affected by job retention schemes and by unemployment received unemployment benefit transfers, which normally amounts to 70% of their social security contribution base. The schemes ensured an income stream during the duration of the contract suspension or unemployment, although of a lower amount than the regular salary.

Public transfers programs partially compensated wage losses for those workers that received them. However, despite the increase in coverage not all affected workers were entitled or had the same degree of coverage. In particular, those workers already unemployed before the pandemic or in temporary contracts that expired might not have had the right to unemployment benefits or only to reduced amounts. In addition, many of the beneficiaries experienced several months of delay before actually receiving their unemployment benefits in their bank accounts. All these developments might have affected the effectiveness of the government support to reduce inequality. This is of particular relevance in a country as Spain, which suffers from a very high labour market duality. In particular, subgroups of the population like young and foreign-born individuals are most likely to be in temporary contracts, and thus more heavily affected.

Large effect of the shutdown on pre-benefits inequality mostly due to low wage earners

To analyze the role of government benefits on inequality our analysis considers two scenarios: pre- and post-government benefits. In the pre-benefits scenario, we consider monthly wages before taking into account the benefits. The post-benefits scenario also considers unemployment insurance benefits, subsidies and furlough schemes.

Fig 2 shows the distribution of changes in pre-benefit wages between February and April 2020 (i.e., before vs. during the lockdown), represented by the solid lines. The x-axis reports the percentage change in wages experienced between the two months, while the y-axis reports the share of account holders in each category. The dashed lines represent the distribution for the same months of 2019, i.e., prior to the pandemic. The top left panel reports the distribution for the entire sample; the other panels report the distribution for each of five wage brackets (measured as of February of 2020): i) the interval between 900 to 1,000 euros, which includes the 25th percentile of the wage distribution; the interval between 1,200 to 1,300 euros, which includes the median; the interval between 1,700 to 1,800 euros, which includes the 75th percentile; the interval between 2,900 and 3,000 euros, which includes the 95 percentile, and the interval between 4,700 and 4,800, which represents the top 1%.

Pre-benefits scenario. Comparing 2020 and 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.g002

Several interesting facts emerge from Fig 2 . First, in 2020 the probability mass of the no-change interval is about half than in 2019. Compared to 2019, in 2020 a sizeable portion has moved to the no-income category. Furthermore, and most interestingly, in 2020 the probability of shifting to the no-income category is higher for individuals in the lower wage brackets.

Another noticeable aspect is that a substantial share of the highest wage earners experience a drastic wage reduction in April relative to February. This seasonal pattern, observed both in 2019 and 2020, is due to the payment of bonuses which occurs in February, and reaches over 30% for the top earners in our sample (i.e., the top 0.01%, not shown in the figure). There is no evidence of an analogous pattern for low wage earners.

S1 Fig in S1 File shows the difference in payments received by account holders between April and February after accounting for extended unemployment insurance and other benefits. Compared to the pre-benefits wages depicted in Fig 2 , the shift to the no-income category is much less pronounced. There is still a large wage reduction for high earners who are largely unaffected by government transfers.

S2 Fig in S1 File compares in the same graph all the levels of initial wages, before and after government benefits, to facilitate the comparisons.

To account for seasonality Fig 3 shows the difference in the proportion of changes in salaries between April and March of 2020 net of the the difference between the same two months in 2019. The S1 File shows the precise transformation to deal with seasonality. When seasonality is controlled for, the effect of the February bonuses for high wage earners disappears. Interestingly, the effect of the pandemic on pre-transfer earnings is very different for low and high wages. For wages below 1,300 euros the lower mass in the no-change brackets is associated with a corresponding shift to no-income category. The importance of the decline of employment for the lowest-income workers is common to other countries like the US [ 20 ]. For wages above 1,700 euros, instead, the lower mass in the no-change brackets is associated with a higher share of individuals experiencing small wage cuts. S3 Fig in S1 File shows the changes for all wage categories in the same figure.

April vs February—2020 vs 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.g003

To summarize the evolution of inequality we compute the Gini index. The S1 File presents a discussion of its calculation. Fig 4 Panel (a) depicts the evolution of the Gini index between February and May for 2020 and 2019, respectively. Both the pre- and post-benefits curves are basically parallel until April 2020, when the pre-benefits Gini index increases considerably while the post-benefit one only moderately. In May 2020 the pre-benefits Gini index remains very high, while the post-benefits index returns to the pre-pandemic level. From February until April of 2020 the pre-benefits Gini index increased close to 0.11 points. This implies a 25% increase in just two months. To evaluate the statistical significance of this large movement in the Gini index we can calculate the confidence intervals around our estimate. There are basically two possible procedures: using a Jakknife or a WLS estimator [ 21 ]. The S1 File describes the calculation of the standard error of the Gini index using a WLS estimator. As expected, given our large sample size, the standard error is very low (0.0002). This implies that the increase of 0.11 points observed in the Gini index between February and April of 2020 is highly statistically significant (well over the level of significance of 1%). Since the confidence intervals are tiny they cannot be visualized in the figures.

(a) Gini index (b) Theil index ( α = 1) (c) Lorentz curve: Pre-benefits, 2020 (d) Lorentz curve: Post-benefits, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.g004

To confirm the robustness of the documented pattern to alternative measures of inequality, in Fig 4 Panel (b) we show the evolution of the Theil index, an inequality measure related to the concept of entropy and to Shannon’s index. The S1 File discusses the computation of this index. The Theil index shows a pattern very similar to the Gini index: a sizeable increase in March for both the pre- and post-benefits distribution which persists in April for the pre-benefit measure but not for the post-benefit one.

Panels (c) and (d) of Fig 4 show the changes in the pre- and post-benefits Lorenz curves respectively for every month between February and May 2020. It is apparent that, for the pre-benefits curve, the downward movement accelerates in April and stabilizes in May, while, for the post-benefit curve, the evolution is smoother.

Within group inequality post benefits has increased among young and foreign-born people

Given the granularity of the data we can also analyze the evolution of inequality within different subgroups of the population, differentiating by gender, age, and country of origin. Panel (a) in Fig 5 shows that there are not major differences in within inequality of males and females before the shock. The magnitude of the increase in the Gini index after the beginning of the pandemic is similar across genders before public transfers, but slightly higher for females in the post-benefits case.

(a) By gender. (b) By age group. (c) By place of birth.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.g005

Panel (b) of Fig 5 shows the evolution of inequality for different age groups. For the youngest cohort (i.e., 16 to 29 years old), there is a considerable increase in the Gini index for pre-transfer earnings. The other groups also experience an increase in inequality though much smaller than for the young. The spike in the Gini index for the young is mitigated when considering the distribution of post-benefit earnings. Yet, the level of post-benefits inequality for this group is still remarkable, both in absolute and in relative terms. Such increase is arguably related to the fact that young workers account for a high proportion of temporary jobs in low wage occupations.

Panel (c) of Fig 5 shows the evolution of the Gini index separately for foreign-born individuals and for natives. As of January 1st 2020, foreign-born individuals represented 14.77% of the total Spanish resident population. Looking at the distribution of pre-benefits earnings, it is clear that inequality increases much more among foreign born than among natives. Such increase is less pronounced when looking at the post-benefits distribution, though, in this case as well, the Gini index for foreign born is significantly higher than for natives.

Interesting differences emerge when dividing foreign-born individuals by the per capita GDP level of the country of origin. For example, as shown in S4 Fig in S1 File , while post-benefits inequality decreases over time for both natives and foreign-born from high-income countries, it remains high for foreign-born from low-income countries.

The disproportionate increase in post-benefit inequality among poorer migrants attests to their vulnerability in times of crisis as their social welfare net is thinner. Foreign born workers from low income countries tend to have occupations with low salaries, and a high proportion of temporary jobs. In many cases they work without a formal contract which means that they cannot prove they were working before the pandemic and, therefore, they cannot get the benefits that other workers get. On the other hand expatriates from high income countries still enjoy a high salary.

Finally, inequality increases more in regions that rely heavily on tourism (e.g., Balearic and Canary Islands) than in other parts of the country (S5 Fig in S1 File ). This is not surprising since the touristic sector is characterized by a high proportion of low wage workers who, as shown above, are the ones most affected by the job losses and wage cuts caused by the pandemic.

The financial crisis of 2008 generated a large increase in inequality in many countries. When some countries were still trying to recover from the financial crisis a new shock, the COVID-19, has hit the economy. Recent research shows that social distancing laws are not responsible for the economic harm [ 15 ] and the responses to emergency declarations are strongly differentiated by income [ 22 ]. In this paper we show that the economic impact is also very heterogeneous by income level which, in turn, is reflected in large increases in inequality before governments policy response.

Our findings contribute to a recent literature on the measurement of economic indicators in real-time, or at very high frequency. Most of the economic research on the impact of COVID-19 has concentrated on its effect on consumption [ 6 , 8 , 15 – 17 ]. We present evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on economic inequality. Our findings show that, before accounting for extended unemployment insurance and furlough benefits, the economic impact of the pandemic caused a large increase of inequality. After considering public benefits the effect of the crisis on inequality is mitigated. We show how bank account data of a representative financial institution can be used to track inequality and monitor the effect of economic polity on its evolution. In contrast with some previous research that uses data on personal finance websites and bank accounts, our data replicates very precisely the distribution of the population of wage earners.

We present evidence that shows a very heterogeneous impact of the pandemic on inequality by income level, age and country of birth of the individuals. Our methodology could be applied to many other countries that have introduced income-support schemes similar to the ones considered in Spain (furlough benefits and extended unemployment insurance). Tracking, at high frequency, the effect of policy responses on inequality allows tuning the policy instruments to mitigate inequality, targeting the groups that contribute the most to the increase of inequality.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249121.s001

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Miguel Angel Barcia for his helpful suggestions. Daniele Alimonti provided excellent research assistance.

- 1. Gourinchas PO. “Flattening the Pandemic and Recession Curves” in Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever, Ed. Baldwin R., Weder di Mauro B. (Chapter 2, 31–40). CEPR Press, London, UK), 2020.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 14. Scheidel Walter. The great leveler: Violence and the history of inequality from the stone age to the twenty-first century. Princeton University Press, 2018.

- 16. Hacioglu S., Kanzig D., and Surico P. The distributional impact of the pandemic. CEPR Discussion Paper 15101, 2020.

- 17. Bachas N., Ganong P., Noel P., Vara J., Wong A., Farrell D., et al. Initial impact of the pandemic on consumer behavior: evidence from linked income, spending, and savings data. NBER Working Paper 27617, 2020.

- 19. IMF. Spain 2020 article iv consultation. 2020.

Advertisement

Gender inequality as a barrier to economic growth: a review of the theoretical literature

- Open access

- Published: 15 January 2021

- Volume 19 , pages 581–614, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Manuel Santos Silva 1 &

- Stephan Klasen 1

55k Accesses

29 Citations

24 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this article, we survey the theoretical literature investigating the role of gender inequality in economic development. The vast majority of theories reviewed argue that gender inequality is a barrier to development, particularly over the long run. Among the many plausible mechanisms through which inequality between men and women affects the aggregate economy, the role of women for fertility decisions and human capital investments is particularly emphasized in the literature. Yet, we believe the body of theories could be expanded in several directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender Inequality and Growth in Europe

The effect of gender inequality on economic development: case of african countries.

The Feminization U

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Theories of long-run economic development have increasingly relied on two central forces: population growth and human capital accumulation. Both forces depend on decisions made primarily within households: population growth is partially determined by households’ fertility choices (e.g., Becker & Barro 1988 ), while human capital accumulation is partially dependent on parental investments in child education and health (e.g., Lucas 1988 ).

In an earlier survey of the literature linking family decisions to economic growth, Grimm ( 2003 ) laments that “[m]ost models ignore the two-sex issue. Parents are modeled as a fictive asexual human being” (p. 154). Footnote 1 Since then, however, economists are increasingly recognizing that gender plays a fundamental role in how households reproduce and care for their children. As a result, many models of economic growth are now populated with men and women. The “fictive asexual human being” is a dying species. In this article, we survey this rich new landscape in theoretical macroeconomics, reviewing, in particular, micro-founded theories where gender inequality affects economic development.

For the purpose of this survey, gender inequality is defined as any exogenously imposed difference between male and female economic agents that, by shaping their behavior, has implications for aggregate economic growth. In practice, gender inequality is typically modeled as differences between men and women in endowments, constraints, or preferences.

Many articles review the literature on gender inequality and economic growth. Footnote 2 Typically, both the theoretical and empirical literature are discussed, but, in almost all cases, the vast empirical literature receives most of the attention. In addition, some of the surveys examine both sides of the two-way relationship between gender inequality and economic growth: gender equality as a cause of economic growth and economic growth as a cause of gender equality. As a result, most surveys end up only scratching the surface of each of these distinct strands of literature.

There is, by now, a large and insightful body of micro-founded theories exploring how gender equality affects economic growth. In our view, these theories merit a separate review. Moreover, they have not received sufficient attention in empirical work, which has largely developed independently (see also Cuberes & Teignier 2014 ). By reviewing the theoretical literature, we hope to motivate empirical researchers in finding new ways of putting these theories to test. In doing so, our work complements several existing surveys. Doepke & Tertilt ( 2016 ) review the theoretical literature that incorporates families in macroeconomic models, without focusing exclusively on models that include gender inequality, as we do. Greenwood, Guner and Vandenbroucke ( 2017 ), in turn, review the theoretical literature from the opposite direction; they study how macroeconomic models can explain changes in family outcomes. Doepke, Tertilt and Voena ( 2012 ) survey the political economy of women’s rights, but without focusing explicitly on their impact on economic development.

To be precise, the scope of this survey consists of micro-founded macroeconomic models where gender inequality (in endowments, constraints, preferences) affects economic growth—either by influencing the economy’s growth rate or shaping the transition paths between multiple income equilibria. As a result, this survey does not cover several upstream fields of partial-equilibrium micro models, where gender inequality affects several intermediate growth-related outcomes, such as labor supply, education, health. Additionally, by focusing on micro-founded macro models, we do not review studies in heterodox macroeconomics, including the feminist economics tradition using structuralist, demand-driven models. For recent overviews of this literature, see Kabeer ( 2016 ) and Seguino ( 2013 , 2020 ). Overall, we find very little dialogue between the neoclassical and feminist heterodox literatures. In this review, we will show that actually these two traditions have several points of contact and reach similar conclusions in many areas, albeit following distinct intellectual routes.

Although the incorporation of gender in macroeconomic models of economic growth is a recent development, the main gendered ingredients of those models are not new. They were developed in at least two strands of literature. First, since the 1960s, “new home economics” has applied the analytical toolbox of rational choice theory to decisions being made within the boundaries of the family (see, e.g., Becker 1960 , 1981 ). Footnote 3 A second literature strand, mostly based on empirical work at the micro level in developing countries, described clear patterns of gender-specific behavior within households that differed across regions of the developing world (see, e.g., Boserup 1970 ). Footnote 4 As we shall see, most of the (micro-founded) macroeconomic models reviewed in this article use several analytical mechanisms from "new home economics”; these mechanisms can typically rationalize several of the gender-specific regularities observed in early studies of developing countries. The growth theorist is then left to explore the aggregate implications for economic development.

The first models we present focus on gender discrimination in (or on access to) the labor market as a distortionary tax on talent. If talent is randomly distributed in the population, men and women are imperfect substitutes in aggregate production, and, as a consequence, gender inequality (as long as determined by non-market processes) will misallocate talent and lower incentives for female human capital formation. These theories do not rely on typical household functions such as reproduction and childrearing. Therefore, in these models, individuals are not organized into households. We review this literature in section 2 .

From there, we proceed to theories where the household is the unit of analysis. In sections 3 and 4 , we cover models that take the household as given and avoid marriage markets or other household formation institutions. This is a world where marriage (or cohabitation) is universal, consensual, and monogamous; families are nuclear, and spouses are matched randomly. The first articles in this tradition model the household as a unitary entity with joint preferences and interests, and with an efficient and centralized decision making process. Footnote 5 These theories posit how men and women specialize into different activities and how parents interact with their children. Section 3 reviews these theories. Over time, the literature has incorporated intra-household dynamics. Now, family members are allowed to have different preferences and interests; they bargain, either cooperatively or not, over family decisions. Now, the theorist recognizes power asymmetries between family members and analyzes how spouses bargain over decisions. Footnote 6 These articles are surveyed in section 4 .

The final set of articles we survey take into account how households are formed. These theories show how gender inequality can influence economic growth and long-run development through marriage market institutions and family formation patterns. Among other topics, this literature has studied ages at first marriage, relative supply of potential partners, monogamy and polygyny, arranged and consensual marriages, and divorce risk. Upon marriage, these models assume different bargaining processes between the spouses, or even unitary households, but they all recognize, in one way or another, that marriage, labor supply, consumption, and investment decisions are interdependent. We review these theories in section 5 .

Table 1 offers a schematic overview of the literature. To improve readability, the table only includes studies that we review in detail, with articles listed in order of appearance in the text. The table also abstracts from models’ extensions and sensitivity checks, and focuses exclusively on the causal pathways leading from gender inequality to economic growth.

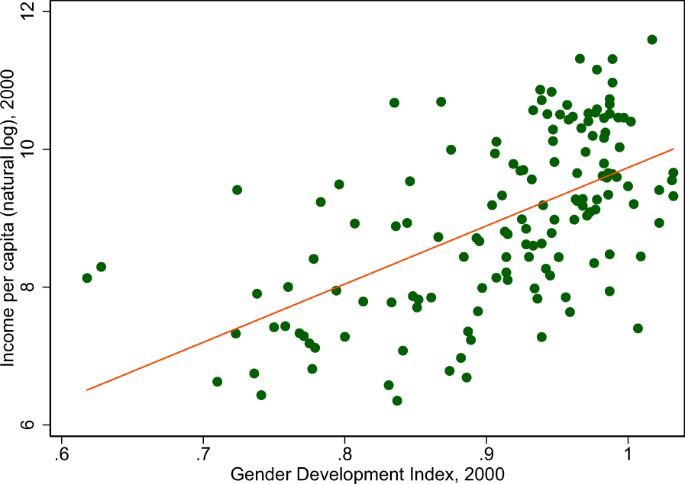

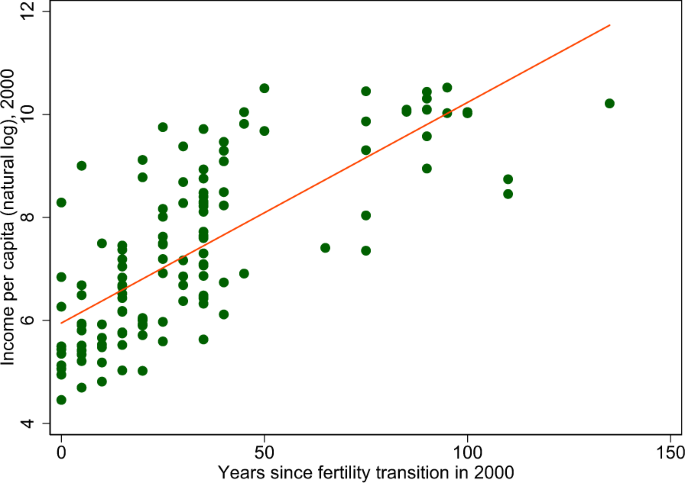

The vast majority of theories reviewed argue that gender inequality is a barrier to economic development, particularly over the long run. The focus on long-run supply-side models reflects a recent effort by growth theorists to incorporate two stylized facts of economic development in the last two centuries: (i) a strong positive association between gender equality and income per capita (Fig. 1 ), and (ii) a strong association between the timing of the fertility transition and income per capita (Fig. 2 ). Footnote 7 Models that endogenize a fertility transition are able to generate a transition from a Malthusian regime of stagnation to a modern regime of sustained economic growth, thus replicating the development experience of human societies in the very long run (e.g., Galor 2005a , b ; Guinnane 2011 ). In contrast, demand-driven models in the heterodox and feminist traditions have often argued that gender wage discrimination and gendered sectoral and occupational segregation can be conducive to economic growth in semi-industrialized export-oriented economies. Footnote 8 In these settings—that fit well the experience of East and Southeast Asian economies—gender wage discrimination in female-intensive export industries reduces production costs and boosts exports, profits, and investment (Blecker & Seguino 2002 ; Seguino 2010 ).

Income level and gender equality. Income is the natural log of per capita GDP (PPP-adjusted). The Gender Development Index is the ratio of gender-specific Human Development Indexes: female HDI/male HDI. Data are for the year 2000. Sources: UNDP

Income level and timing of the fertility transition. Income is the natural log of per capita GDP (PPP-adjusted) in 2000. Years since fertility transition are the number of years between 2000 and the onset year of the fertility decline. See Reher ( 2004 ) for details. Sources: UNDP and Reher ( 2004 )

In most long-run, supply-side models reviewed here, irrespectively of the underlying source of gender differences (e.g., biology, socialization, discrimination), the opportunity cost of women’s time in foregone labor market earnings is lower than that of men. This gender gap in the value of time affects economic growth through two main mechanisms. First, when the labor market value of women’s time is relatively low, women will be in charge of childrearing and domestic work in the family. A low value of female time means that children are cheap. Fertility will be high, and economic growth will be low, both because population growth has a direct negative impact on long-run economic performance and because human capital accumulates at a slower pace (through the quantity-quality trade-off). Second, if parents expect relatively low returns to female education, due to women specializing in domestic activities, they will invest relatively less in the education of girls. In the words of Harriet Martineau, one of the first to describe this mechanism, “as women have none of the objects in life for which an enlarged education is considered requisite, the education is not given” (Martineau 1837 , p. 107). In the long run, lower human capital investments (on girls) lead to slower economic development.

Overall, gender inequality can be conceptualized as a source of inefficiency, to the extent that it results in the misallocation of productive factors, such as talent or labor, and as a source of negative externalities, when it leads to higher fertility, skewed sex ratios, or lower human capital accumulation.

We conclude, in section 6 , by examining the limitations of the current literature and pointing ways forward. Among them, we suggest deeper investigations of the role of (endogenous) technological change on gender inequality, as well as greater attention to the role and interests of men in affecting gender inequality and its impact on growth.

2 Gender discrimination and misallocation of talent

Perhaps the single most intuitive argument for why gender discrimination leads to aggregate inefficiency and hampers economic growth concerns the allocation of talent. Assume that talent is randomly distributed in the population. Then, an economy that curbs women’s access to education, market employment, or certain occupations draws talent from a smaller pool than an economy without such restrictions. Gender inequality can thus be viewed as a distortionary tax on talent. Indeed, occupational choice models with heterogeneous talent (as in Roy 1951 ) show that exogenous barriers to women’s participation in the labor market or access to certain occupations reduce aggregate productivity and per capita output (Cuberes & Teignier 2016 , 2017 ; Esteve-Volart 2009 ; Hsieh, Hurst, Jones and Klenow 2019 ).

Hsieh et al. ( 2019 ) represent the US economy with a model where individuals sort into occupations based on innate ability. Footnote 9 Gender and race identity, however, are a source of discrimination, with three forces preventing women and black men from choosing the occupations best fitting their comparative advantage. First, these groups face labor market discrimination, which is modeled as a tax on wages and can vary by occupation. Second, there is discrimination in human capital formation, with the costs of occupation-specific human capital being higher for certain groups. This cost penalty is a composite term encompassing discrimination or quality differentials in private or public inputs into children’s human capital. The third force are group-specific social norms that generate utility premia or penalties across occupations. Footnote 10

Assuming that the distribution of innate ability across race and gender is constant over time, Hsieh et al. ( 2019 ) investigate and quantify how declines in labor market discrimination, barriers to human capital formation, and changing social norms affect aggregate output and productivity in the United States, between 1960 and 2010. Over that period, their general equilibrium model suggests that around 40 percent of growth in per capita GDP and 90 percent of growth in labor force participation can be attributed to reductions in the misallocation of talent across occupations. Declining in barriers to human capital formation account for most of these effects, followed by declining labor market discrimination. Changing social norms, on the other hand, explain only a residual share of aggregate changes.

Two main mechanisms drive these results. First, falling discrimination improves efficiency through a better match between individual ability and occupation. Second, because discrimination is higher in high-skill occupations, when discrimination decreases, high-ability women and black men invest more in human capital and supply more labor to the market. Overall, better allocation of talent, rising labor supply, and faster human capital accumulation raise aggregate growth and productivity.

Other occupational choice models assuming gender inequality in access to the labor market or certain occupations reach similar conclusions. In addition to the mechanisms in Hsieh et al. ( 2019 ), barriers to women’s work in managerial or entrepreneurial occupations reduce average talent in these positions, resulting in aggregate losses in innovation, technology adoption, and productivity (Cuberes & Teignier 2016 , 2017 ; Esteve-Volart 2009 ). The argument can be readily applied to talent misallocation across sectors (Lee 2020 ). In Lee’s model, female workers face discrimination in the non-agricultural sector. As a result, talented women end up sorting into ill-suited agricultural activities. This distortion reduces aggregate productivity in agriculture. Footnote 11

To sum up, when talent is randomly distributed in the population, barriers to women’s education, employment, or occupational choice effectively reduce the pool of talent in the economy. According to these models, dismantling these gendered barriers can have an immediate positive effect on economic growth.

3 Unitary households: parents and children

In this section, we review models built upon unitary households. A unitary household maximizes a joint utility function subject to pooled household resources. Intra-household decision making is assumed away; the household is effectively a black-box. In this class of models, gender inequality stems from a variety of sources. It is rooted in differences in physical strength (Galor & Weil 1996 ; Hiller 2014 ; Kimura & Yasui 2010 ) or health (Bloom et al. 2015 ); it is embedded in social norms (Hiller 2014 ; Lagerlöf 2003 ), labor market discrimination (Cavalcanti & Tavares 2016 ), or son preference (Zhang, Zhang and Li 1999 ). In all these models, gender inequality is a barrier to long-run economic development.

Galor & Weil ( 1996 ) model an economy with three factors of production: capital, physical labor (“brawn”), and mental labor (“brain”). Men and women are equally endowed with brains, but men have more brawn. In economies starting with very low levels of capital per worker, women fully specialize in childrearing because their opportunity cost in terms of foregone market earnings is lower than men’s. Over time, the stock of capital per worker builds up due to exogenous technological progress. The degree of complementarity between capital and mental labor is higher than that between capital and physical labor; as the economy accumulates capital per worker, the returns to brain rise relative to the returns to brawn. As a result, the relative wages of women rise, increasing the opportunity cost of childrearing. This negative substitution effect dominates the positive income effect on the demand for children and fertility falls. Footnote 12 As fertility falls, capital per worker accumulates faster creating a positive feedback loop that generates a fertility transition and kick starts a process of sustained economic growth.

The model has multiple stable equilibria. An economy starting from a low level of capital per worker is caught in a Malthusian poverty trap of high fertility, low income per capita, and low relative wages for women. In contrast, an economy starting from a sufficiently high level of capital per worker will converge to a virtuous equilibrium of low fertility, high income per capita, and high relative wages for women. Through exogenous technological progress, the economy can move from the low to the high equilibrium.

Gender inequality in labor market access or returns to brain can slow down or even prevent the escape from the Malthusian equilibrium. Wage discrimination or barriers to employment would work against the rise of relative female wages and, therefore, slow down the takeoff to modern economic growth.

The Galor and Weil model predicts how female labor supply and fertility evolve in the course of development. First, (married) women start participating in market work and only afterwards does fertility start declining. Historically, however, in the US and Western Europe, the decline in fertility occurred before women’s participation rates in the labor market started their dramatic increase. In addition, these regions experienced a mid-twentieth century baby boom which seems at odds with Galor and Weil’s theory.

Both these stylized facts can be addressed by adding home production to the modeling, as do Kimura & Yasui ( 2010 ). In their article, as capital per worker accumulates, the market wage for brains rises and the economy moves through four stages of development. In the first stage, with a sufficiently low market wage, both husband and wife are fully dedicated to home production and childrearing. The household does not supply labor to the market; fertility is high and constant. In the second stage, as the wage rate increases, men enter the labor market (supplying both brawn and brain), whereas women remain fully engaged in home production and childrearing. But as men partially withdraw from home production, women have to replace them. As a result, their time cost of childrearing goes up. At this stage of development, the negative substitution effect of rising wages on fertility dominates the positive income effect. Fertility starts declining, even though women have not yet entered the labor market. The third stage arrives when men stop working in home production. There is complete specialization of labor by gender; men only do market work, and women only do home production and childrearing. As the market wage rises for men, the positive income effect becomes dominant and fertility increases; this mimics the baby-boom period of the mid-twentieth century. In the fourth and final stage, once sufficient capital is accumulated, women enter the market sector as wage-earners. The negative substitution effect of rising female opportunity costs dominates once again, and fertility declines. The economy moves from a “breadwinner model” to a “dual-earnings model”.

Another important form of gender inequality is discrimination against women in the form of lower wages, holding male and female productivity constant. Cavalcanti & Tavares ( 2016 ) estimate the aggregate effects of wage discrimination using a model-based general equilibrium representation of the US economy. In their model, women are assumed to be more productive in childrearing than men, so they pay the full time cost of this activity. In the labor market, even though men and women are equally productive, women receive only a fraction of the male wage rate—this is the wage discrimination assumption. Wage discrimination works as a tax on female labor supply. Because women work less than they would without discrimination, there is a negative level effect on per capita output. In addition, there is a second negative effect of wage discrimination operating through endogenous fertility. Since lower wages reduce women’s opportunity costs of childrearing, fertility is relatively high, and output per capita is relatively low. The authors calibrate the model to US steady state parameters and estimate large negative output costs of the gender wage gap. Reducing wage discrimination against women by 50 percent would raise per capita income by 35 percent, in the long run.

Human capital accumulation plays no role in Galor & Weil ( 1996 ), Kimura & Yasui ( 2010 ), and Cavalcanti & Tavares ( 2016 ). Each person is exogenously endowed with a unit of brains. The fundamental trade-off in the these models is between the income and substitution effects of rising wages on the demand for children. When Lagerlöf ( 2003 ) adds education investments to a gender-based model, an additional trade-off emerges: that between the quantity and the quality of children.

Lagerlöf ( 2003 ) models gender inequality as a social norm: on average, men have higher human capital than women. Confronted with this fact, parents play a coordination game in which it is optimal for them to reproduce the inequality in the next generation. The reason is that parents expect the future husbands of their daughters to be, on average, relatively more educated than the future wives of their sons. Because, in the model, parents care for the total income of their children’s future households, they respond by investing relatively less in daughters’ human capital. Here, gender inequality does not arise from some intrinsic difference between men and women. It is instead the result of a coordination failure: “[i]f everyone else behaves in a discriminatory manner, it is optimal for the atomistic player to do the same” (Lagerlöf 2003 , p. 404).

With lower human capital, women earn lower wages than men and are therefore solely responsible for the time cost of childrearing. But if, exogenously, the social norm becomes more gender egalitarian over time, the gender gap in parental educational investment decreases. As better educated girls grow up and become mothers, their opportunity costs of childrearing are higher. Parents trade-off the quantity of children by their quality; fertility falls and human capital accumulates. However, rising wages have an offsetting positive income effect on fertility because parents pay a (fixed) “goods cost” per child. The goods cost is proportionally more important in poor societies than in richer ones. As a result, in poor economies, growth takes off slowly because the positive income effect offsets a large chunk of the negative substitution effect. As economies grow richer, the positive income effect vanishes (as a share of total income), and fertility declines faster. That is, growth accelerates over time even if gender equality increases only linearly.