- Skip to main content

- Skip to header right navigation

- Skip to site footer

High Performance. Innovation. Leadership.

What is Creative Problem Solving?

“Every problem is an opportunity in disguise.” — John Adams

Imagine if you come up with new ideas and solve problems better, faster, easier?

Imagine if you could easily leverage the thinking from multiple experts and different points of view?

That’s the promise and the premise of Creative Problem Solving.

As Einstein put it, “Creativity is intelligence having fun.”

Creative problem solving is a systematic approach that empowers individuals and teams to unleash their imagination , explore diverse perspectives, and generate innovative solutions to complex challenges.

Throughout my years at Microsoft, I’ve used variations of Creative Problem Solving to tackle big, audacious challenges and create new opportunities for innovation.

I this article, I walkthrough the original Creative Problem Solving process and variations so that you can more fully appreciate the power of the process and how it’s evolved over the years.

On This Page

Innovation is a Team Sport What is Creative Problem Solving? What is the Creative Problem Solving Process? Variations of Creative Problem Solving Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Criticisms of Creative Problem Solving Creative Problem Solving 21st Century FourSight Thinking Profiles Basadur’s Innovative Process Synetics SCAMPER Design Thinking

Innovation is a Team Sport

Recognizing that innovation is a team sport , I understood the importance of equipping myself and my teams with the right tools for the job.

By leveraging different problem-solving approaches, I have been able to navigate complex landscapes , think outside the box, and find unique solutions.

Creative Problem Solving has served as a valuable compass , guiding me to explore uncharted territories and unlock the potential for groundbreaking ideas.

With a diverse set of tools in my toolbox, I’ve been better prepared to navigate the dynamic world of innovation and contribute to the success and amplify impact for many teams and many orgs for many years.

By learning and teaching Creative Problem Solving we empower diverse teams to appreciate and embrace cognitive diversity to solve problems and create new opportunities with skill.

Creative problem solving is a mental process used to find original and effective solutions to problems.

It involves going beyond traditional methods and thinking outside the box to come up with new and innovative approaches.

Here are some key aspects of creative problem solving:

- Divergent Thinking : This involves exploring a wide range of possibilities and generating a large number of ideas, even if they seem unconventional at first.

- Convergent Thinking : Once you have a pool of ideas, you need to narrow them down and select the most promising ones. This requires critical thinking and evaluation skills.

- Process : There are various frameworks and techniques that can guide you through the creative problem-solving process. These can help you structure your thinking and increase your chances of finding innovative solutions.

Benefits of Creative Problem Solving:

- Finding New Solutions : It allows you to overcome challenges and achieve goals in ways that traditional methods might miss.

- Enhancing Innovation : It fosters a culture of innovation and helps organizations stay ahead of the curve.

- Improved Adaptability : It equips you to handle unexpected situations and adapt to changing circumstances.

- Boosts Confidence: Successfully solving problems with creative solutions can build confidence and motivation.

Here are some common techniques used in creative problem solving:

- Brainstorming : This is a classic technique where you generate as many ideas as possible in a short period of time.

- SCAMPER: This is a framework that prompts you to consider different ways to Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Magnify/Minify, Put to other uses, Eliminate, and Rearrange elements of the problem.

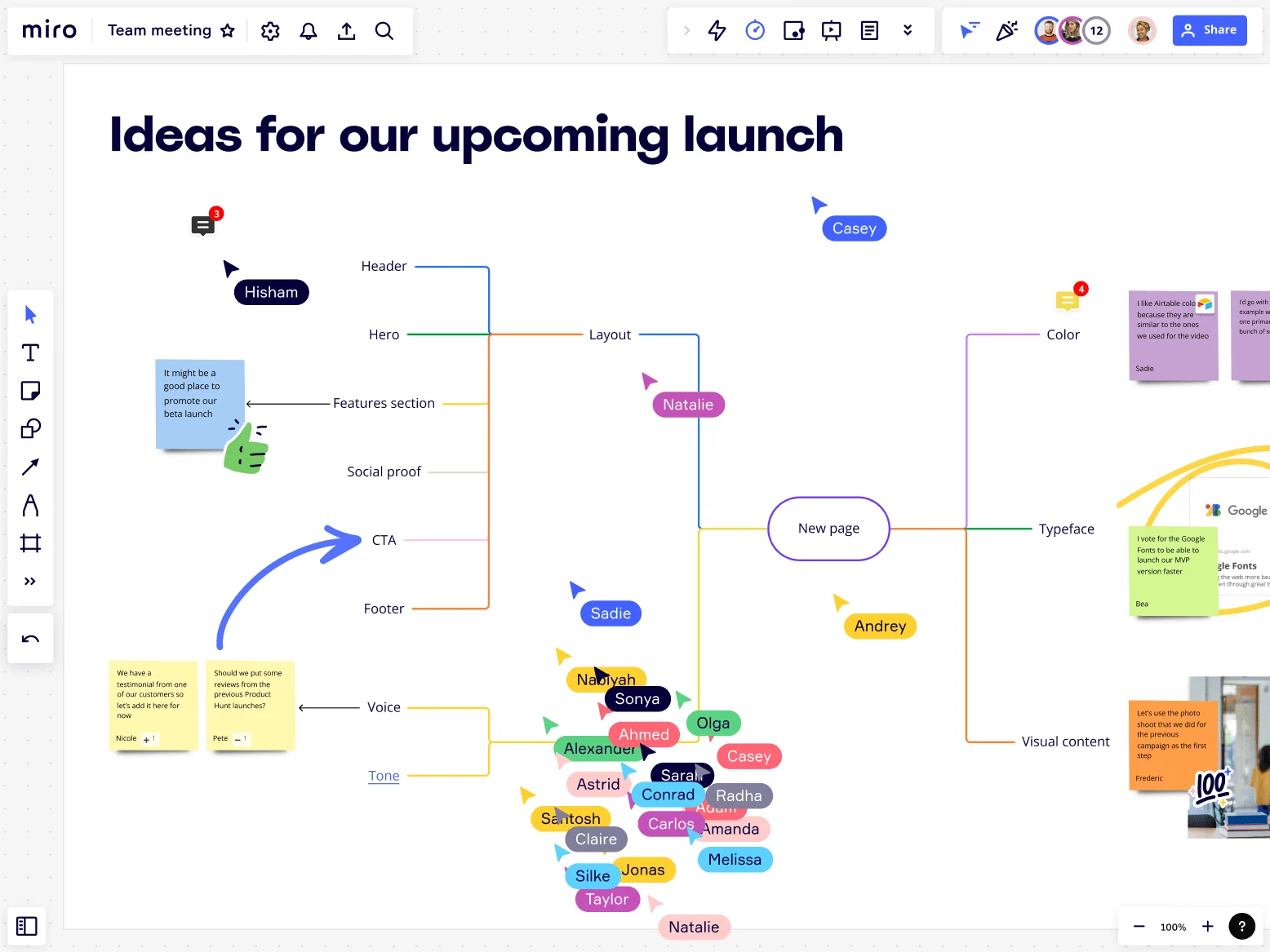

- Mind Mapping: This technique involves visually organizing your ideas and connections between them.

- Lateral Thinking: This approach challenges you to look at the problem from different angles and consider unconventional solutions.

Creative problem solving is a valuable skill for everyone, not just artists or designers.

You can apply it to all aspects of life, from personal challenges to professional endeavors.

What is the Creative Problem Solving Process?

The Creative Problem Solving (CPS) framework is a systematic approach for generating innovative solutions to complex problems.

It’s effectively a process framework.

It provides a structured process that helps individuals and teams think creatively, explore possibilities, and develop practical solutions.

The Creative Problem Solving process framework typically consists of the following stages:

- Clarify : In this stage, the problem or challenge is clearly defined, ensuring a shared understanding among participants. The key objectives, constraints, and desired outcomes are identified.

- Generate Ideas : During this stage, participants engage in divergent thinking to generate a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. The focus is on quantity and deferring judgment, encouraging free-flowing creativity.

- Develop Solutions : In this stage, the generated ideas are evaluated, refined, and developed into viable solutions. Participants explore the feasibility, practicality, and potential impact of each idea, considering the resources and constraints at hand.

- Implement : Once a solution or set of solutions is selected, an action plan is developed to guide the implementation process. This includes defining specific steps, assigning responsibilities, setting timelines, and identifying the necessary resources.

- Evaluate : After implementing the solution, the outcomes and results are evaluated to assess the effectiveness and impact. Lessons learned are captured to inform future problem-solving efforts and improve the process.

Throughout the Creative Problem Solving framework, various creativity techniques and tools can be employed to stimulate idea generation, such as brainstorming, mind mapping, SCAMPER (Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse), and others.

These techniques help break through traditional thinking patterns and encourage novel approaches to problem-solving.

What are Variations of the Creative Problem Solving Process?

There are several variations of the Creative Problem Solving process, each emphasizing different steps or stages.

Here are five variations that are commonly referenced:

- Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving : This is one of the earliest and most widely used versions of Creative Problem Solving. It consists of six stages: Objective Finding, Fact Finding, Problem Finding, Idea Finding, Solution Finding, and Acceptance Finding. It follows a systematic approach to identify and solve problems creatively.

- Creative Problem Solving 21st Century : Creative Problem Solving 21st Century, developed by Roger Firestien, is an innovative approach that empowers individuals to identify and take action towards achieving their goals, wishes, or challenges by providing a structured process to generate ideas, develop solutions, and create a plan of action.

- FourSight Thinking Profiles : This model introduces four stages in the Creative Problem Solving process: Clarify, Ideate, Develop, and Implement. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the problem, generating a range of ideas, developing and evaluating those ideas, and finally implementing the best solution.

- Basadur’s Innovative Process : Basadur’s Innovative Process, developed by Min Basadur, is a systematic and iterative process that guides teams through eight steps to effectively identify, define, generate ideas, evaluate, and implement solutions, resulting in creative and innovative outcomes.

- Synectics : Synectics is a Creative Problem Solving variation that focuses on creating new connections and insights. It involves stages such as Problem Clarification, Idea Generation, Evaluation, and Action Planning. Synectics encourages thinking from diverse perspectives and applying analogical reasoning.

- SCAMPER : SCAMPER is an acronym representing different creative thinking techniques to stimulate idea generation. Each letter stands for a strategy: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Rearrange. SCAMPER is used as a tool within the Creative Problem Solving process to generate innovative ideas by applying these strategies.

- Design Thinking : While not strictly a variation of Creative Problem Solving, Design Thinking is a problem-solving approach that shares similarities with Creative Problem Solving. It typically includes stages such as Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test. Design Thinking focuses on understanding users’ needs, ideating and prototyping solutions, and iterating based on feedback.

These are just a few examples of variations within the Creative Problem Solving framework. Each variation provides a unique perspective on the problem-solving process, allowing individuals and teams to approach challenges in different ways.

Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving (CPS)

The original Creative Problem Solving (CPS) process, developed by Alex Osborn and Sidney Parnes, consists of the following steps:

- Objective Finding : In this step, the problem or challenge is clearly defined, and the objectives and goals are established. It involves understanding the problem from different perspectives, gathering relevant information, and identifying the desired outcomes.

- Fact Finding : The objective of this step is to gather information, data, and facts related to the problem. It involves conducting research, analyzing the current situation, and seeking a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the problem.

- Problem Finding : In this step, the focus is on identifying the root causes and underlying issues contributing to the problem. It involves reframing the problem, exploring it from different angles, and asking probing questions to uncover insights and uncover potential areas for improvement.

- Idea Finding : This step involves generating a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. Participants engage in divergent thinking techniques, such as brainstorming, to produce as many ideas as possible without judgment or evaluation. The aim is to encourage creativity and explore novel possibilities.

- Solution Finding : After generating a pool of ideas, the next step is to evaluate and select the most promising solutions. This involves convergent thinking, where participants assess the feasibility, desirability, and viability of each idea. Criteria are established to assess and rank the solutions based on their potential effectiveness.

- Acceptance Finding : In this step, the selected solution is refined, developed, and adapted to fit the specific context and constraints. Strategies are identified to overcome potential obstacles and challenges. Participants work to gain acceptance and support for the chosen solution from stakeholders.

- Solution Implementation : Once the solution is finalized, an action plan is developed to guide its implementation. This includes defining specific steps, assigning responsibilities, setting timelines, and securing the necessary resources. The solution is put into action, and progress is monitored to ensure successful execution.

- Monitoring and Evaluation : The final step involves tracking the progress and evaluating the outcomes of the implemented solution. Lessons learned are captured, and feedback is gathered to inform future problem-solving efforts. This step helps refine the process and improve future problem-solving endeavors.

The CPS process is designed to be iterative and flexible, allowing for feedback loops and refinement at each stage. It encourages collaboration, open-mindedness, and the exploration of diverse perspectives to foster creative problem-solving and innovation.

Criticisms of the Original Creative Problem Solving Approach

While Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving is a widely used and effective problem-solving framework, it does have some criticisms, challenges, and limitations.

These include:

- Linear Process : CPS follows a structured and linear process, which may not fully capture the dynamic and non-linear nature of complex problems.

- Overemphasis on Rationality : CPS primarily focuses on logical and rational thinking, potentially overlooking the value of intuitive or emotional insights in the problem-solving process.

- Limited Cultural Diversity : The CPS framework may not adequately address the cultural and contextual differences that influence problem-solving approaches across diverse groups and regions.

- Time and Resource Intensive : Implementing the CPS process can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring significant commitment and investment from participants and organizations.

- Lack of Flexibility : The structured nature of CPS may restrict the exploration of alternative problem-solving methods, limiting adaptability to different situations or contexts.

- Limited Emphasis on Collaboration : Although CPS encourages group participation, it may not fully leverage the collective intelligence and diverse perspectives of teams, potentially limiting the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving.

- Potential Resistance to Change : Organizations or individuals accustomed to traditional problem-solving approaches may encounter resistance or difficulty in embracing the CPS methodology and its associated mindset shift.

Despite these criticisms and challenges, the CPS framework remains a valuable tool for systematic problem-solving.

Adapting and supplementing it with other methodologies and approaches can help overcome some of its limitations and enhance overall effectiveness.

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Roger Firestien is a master facilitator of the Creative Problem Solving process. He has been using it, studying it, researching it, and teaching it for 40 years.

According to him, the 21st century requires a new approach to problem-solving that is more creative and innovative.

He has developed a program that focuses on assisting facilitators of the Creative Problem Solving Process to smoothly and confidently transition from one stage to the next in the Creative Problem Solving process as well as learn how to talk less and accomplish more while facilitating Creative Problem Solving.

Creative Problem Solving empowers individuals to identify and take action towards achieving their goals, manifesting their aspirations, or addressing challenges they wish to overcome.

Unlike approaches that solely focus on problem-solving, CPS recognizes that the user’s objective may not necessarily be framed as a problem. Instead, CPS supports users in realizing their goals and desires, providing a versatile framework to guide them towards success.

Why Creative Problem Solving 21st Century?

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century addresses challenges with the original Creative Problem Solving method by adapting it to the demands of the modern era. Roger Firestien recognized that the 21st century requires a new approach to problem-solving that is more creative and innovative.

The Creative Problem Solving 21st Century program focuses on helping facilitators smoothly transition between different stages of the problem-solving process. It also teaches them how to be more efficient and productive in their facilitation by talking less and achieving more results.

Unlike approaches that solely focus on problem-solving, Creative Problem Solving 21st Century acknowledges that users may not always frame their objectives as problems. It recognizes that individuals have goals, wishes, and challenges they want to address or achieve. Creative Problem Solving provides a flexible framework to guide users towards success in realizing their aspirations.

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century builds upon the foundational work of pioneers such as Osborn, Parnes, Miller, and Firestien. It incorporates practical techniques like PPC (Pluses, Potentials, Concerns) and emphasizes the importance of creative leadership skills in driving change.

Stages of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

- Clarify the Problem

- Generate Ideas

- Develop Solutions

- Plan for Action

Steps of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Here are stages and steps of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century per Roger Firestien:

CLARIFY THE PROBLEM

Start here when you are looking to improve, create, or solve something. You want to explore the facts, feelings and data around it. You want to find the best problem to solve.

IDENTIFY GOAL, WISH OR CHALLENGE Start with a goal, wish or challenge that begins with the phrase: “I wish…” or “It would be great if…”

Diverge : If you are not quite clear on a goal then create, invent, solve or improve.

Converge : Select the goal, wish or challenge on which you have Ownership, Motivation and a need for Imagination.

GATHER DATA

Diverge : What is a brief history of your goal, wish or challenge? What have you already thought of or tried? What might be your ideal goal?

Converge : Select the key data that reveals a new insight into the situation or that is important to consider throughout the remainder of the process.

Diverge : Generate many questions about your goal, wish or challenge. Phrase your questions beginning with: “How to…?” “How might…?” “What might be all the ways to…?” Try turning your key data into questions that redefine the goal, wish or challenge.

- Mark the “HITS” : New insight. Promising direction. Nails it! Feels good in your gut.

- Group the related “HITS” together.

- Restate the cluster . “How to…” “What might be all the…”

GENERATE IDEAS

Start here when you have a clearly defined problem and you need ideas to solve it. The best way to create great ideas is to generate LOTS of ideas. Defer judgment. Strive for quantity. Seek wild & unusual ideas. Build on other ideas.

Diverge : Come up with at least 40 ideas for solving your problem. Come up with 40 more. Keep going. Even as you see good ideas emerge, keep pushing for novelty. Stretch!

- Mark the “HITS”: Interesting, Intriguing, Useful, Solves the problem. Sparkles at you.

- Restate the cluster with a verb phrase.

DEVELOP SOLUTIONS

Start here when you want to turn promising ideas into workable solutions.

DEVELOP YOUR SOLUTION Review your clusters of ideas and blend them into a “story.” Imagine in detail what your solution would look like when it is implemented.

Begin your solution story with the phrase, “What I see myself doing is…”

PPCo EVALUATION

PPCo stands for Pluses, Potentials, Concerns and Overcome concerns

Review your solution story .

- List the PLUSES or specific strengths of your solution.

- List the POTENTIALS of your solution. What might be the result if you were to implement your idea?

- Finally, list your CONCERNS about the solution. Phrase your concerns beginning with “How to…”

- Diverge and generate ideas to OVERCOME your concerns one at a time until they have all been overcome

- Converge and select the best ideas to overcome your concerns. Use these ideas to improve your solution.

PLAN FOR ACTION

Start here when you have a solution and need buy-in from others. You want to create a detailed plan of action to follow.

Diverge : List all of the actions you might take to implement your solution.

- What might you do to make your solution easy to understand?

- What might you do to demonstrate the advantages of your solution?

- How might you gain acceptance of your solution?

- What steps might you take to put your solution into action?

Converge : Select the key actions to implement your solution. Create a plan, detailing who does what by when.

Credits for the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Creative Problem Solving – 21st Century is based on the work of: Osborn, A.F..(1953). Applied Imagination: Principles and procedures of Creative Problem Solving. New York: Scribner’s. Parnes, S.J, Noller, R.B & Biondi, A. (1977). Guide to Creative Action. New York: Scribner’s. Miller, B., Firestien, R., Vehar, J. Plain language Creative Problem-Solving Model, 1997. Puccio, G.J., Mance, M., Murdock, M.C. (2010) Creative Leadership: Skills that drive change. (Second Edition), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. Miller, B., Vehar J., Firestien, R., Thurber, S. Nielsen, D. (2011) Creativity Unbound: An introduction to creative process. (Fifth Edition), Foursight, LLC., Evanston, IL. PPC (Pluses, Potentials & Concerns) was invented by Diane Foucar-Szocki, Bill Shepard & Roger Firestien in 1982

Where to Go for More on Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Here are incredible free resources to ramp up on Creative Problem Solving 21st Century:

- PDF of Creative Problem Solving 21st Edition (RogerFirestien.com)

- PDF Worksheets for Creative Problem Solving (RogerFirestien.com)

- Video: Roger Firestien on 40 Years of Creative Problem Solving

Video Walkthroughs

- Video 1: Introduction to Creative Problem Solving

- Video 2: Identify your Goal/Wish/Challenge

- Video 3: Gather Data

- Video 4: Clarify the Problem: Creative Questions

- Video 5: Clarify the Problem: Why? What’s Stopping Me?

- Video 6: Selecting the Best Problem

- Video 7: How to do a Warm-up

- Video 8: Generate Ideas: Sticky Notes + Forced Connections

- Video 9: Generate Ideas: Brainwriting

- Video 10: Selecting the Best Ideas

- Video 11: Develop Solutions: PPCO

- Video 12: Generating Action Steps

- Video 13: Create Your Action Plan

- Video 14: CPS: The Whole Process

FourSight Thinking Profiles

The FourSight Thinking Skills Profile is an assessment tool designed to measure an individual’s thinking preferences and skills.

It focuses on four key thinking styles or stages that contribute to the creative problem-solving process.

The assessment helps individuals and teams understand their strengths and areas for development in each of these stages.

Why FourSight Thinking Profiles?

The FourSight method was necessary to address certain limitations or challenges that were identified in the original CPS method.

- Thinking Preferences : The FourSight model recognizes that individuals have different thinking preferences or cognitive styles. By understanding and leveraging these preferences, the FourSight method aims to optimize idea generation and problem-solving processes within teams and organizations.

- Overemphasis on Ideation : While ideation is a critical aspect of CPS, the original method sometimes focused too heavily on generating ideas without adequate attention to other stages, such as problem clarification, solution development, and implementation. FourSight offers a more balanced approach across all stages of the CPS process.

- Enhanced Problem Definition : FourSight places a particular emphasis on the Clarify stage, which involves defining the problem or challenge. This is an important step to ensure that the problem is well-understood and properly framed before proceeding to ideation and solution development.

- Research-Based Approach : The development of FourSight was influenced by extensive research on thinking styles and creativity. By incorporating these research insights into the CPS process, FourSight provides a more evidence-based and comprehensive approach to creative problem-solving.

Stages of FourSight Creative Problem Solving

FourSight Creative Problem Solving consists of four thinking stages, each associated with a specific thinking preference:

- Clarify : In this stage, the focus is on gaining a clear understanding of the problem or challenge. Participants define the problem statement, gather relevant information, and identify the key objectives and desired outcomes. This stage involves analytical thinking and careful examination of the problem’s context and scope.

- Ideate : The ideation stage involves generating a broad range of ideas and potential solutions. Participants engage in divergent thinking, allowing for a free flow of creativity and encouraging the exploration of unconventional possibilities. Various brainstorming techniques and creativity tools can be utilized to stimulate idea generation.

- Develop : Once a pool of ideas has been generated, the next stage is to develop and refine the selected ideas. Participants shift into a convergent thinking mode, evaluating and analyzing the feasibility, practicality, and potential impact of each idea. The emphasis is on refining and shaping the ideas into viable solutions.

- Implement : The final stage is focused on implementing the chosen solution. Participants develop an action plan, define specific steps and timelines, assign responsibilities, and identify the necessary resources. This stage requires practical thinking and attention to detail to ensure the successful execution of the solution.

Throughout the FourSight framework, it is recognized that individuals have different thinking preferences. Some individuals naturally excel in the Clarify stage, while others thrive in Ideate, Develop, or Implement.

By understanding these preferences, the FourSight framework encourages collaboration and diversity of thinking styles, ensuring a well-rounded approach to problem-solving and innovation.

The FourSight process can be iterative, allowing for feedback loops and revisiting previous stages as needed. It emphasizes the importance of open communication, respect for different perspectives, and leveraging the collective intelligence of a team to achieve optimal results.

4 Thinking Profiles in FourSight

In the FourSight model, there are four preferences that individuals can exhibit. These preferences reflect where individuals tend to focus their energy and time within the creative problem-solving process.

The four preferences in FourSight are:

- Clarifier : Individuals with a Clarifier preference excel in the first stage of the creative problem-solving process, which is about gaining clarity and understanding the problem. They are skilled at asking questions, gathering information, and analyzing data to define the problem accurately.

- Ideator : Individuals with an Ideator preference thrive in the second stage, which involves generating a wide range of ideas. They are imaginative thinkers who excel at brainstorming, thinking outside the box, and generating creative solutions. Ideators are known for their ability to explore multiple perspectives and come up with diverse ideas.

- Developer : Individuals with a Developer preference excel in the third stage of the process, which focuses on refining and developing ideas. They are skilled at evaluating ideas, analyzing their feasibility, and transforming them into actionable plans or solutions. Developers excel in taking promising ideas and shaping them into practical and effective strategies.

- Implementer : Individuals with an Implementer preference shine in the final stage of the process, which is about planning for action and executing the chosen solution. Implementers are skilled at organizing tasks, creating action plans, and ensuring successful implementation. They focus on turning ideas into tangible outcomes and are known for their ability to execute projects efficiently.

It’s important to note that while individuals may have a primary preference, everyone is capable of participating in all stages of the creative problem-solving process.

However, the FourSight model suggests that individuals tend to have a natural inclination or preference towards one or more of these stages. Understanding one’s preferences can help individuals leverage their strengths and work effectively in a team by appreciating the diversity of thinking preferences.

Right Hand vs. Left Hand

The FourSight model is a way to understand how people approach the creative process. It measures our preferences for different stages of creativity.

A good analogy for this is writing with your right or left hand. Think about writing with your right or left hand. Most of us have a dominant hand that we use for writing. It’s the hand we’re most comfortable with and it comes naturally to us. But it doesn’t mean we can’t write with our non-dominant hand. We can still do it, but it requires more effort and focus.

Similarly, in the creative process, we have preferred stages or parts that we enjoy and feel comfortable in. These are our peak preferences. However, it doesn’t mean we can’t work on the other stages. We can make a conscious effort to spend time and work on those stages, even if they don’t come as naturally to us.

Combinations of FourSight Profiles

Your FourSight profile is determined by four scores that represent your preferences in the creative process. Your profile reveals where you feel most energized and where you may struggle.

If you have a single peak in your profile, refer back to the description of that preference. If you have two or more peaks, continue reading to understand your tendencies when engaging in any kind of innovation.

Here are how the combinations show up, along with their labels:

2-Way Combinations

- High Clarifier & High Ideator = “Early Bird

- High Clarifier & High Developer = “Analyst”

- High Clarifier & High Implementer = “Accelerator”

- High Ideator & High Developer = “Theorist”

- High Ideator & High Implementer = “Driver”

- High Developer & High Implementer = “Finisher”

3-Way Combinations

- High Clarifier, Ideator & Developer = “Hare”

- High Clarifier, Ideator & Implementer = “Idea Broker”

- High Clarifier, Developer & Implementer = “Realist”

- High Ideator, Developer & Implementer = “Optimist”

4-Way Combination Nearly Equal for All Four Preferences = “Integrator”

Where to Go for More On FourSight

- FourSight Home

- FourSight Thinking Profile Interpretive Guide PDF

- FourSight Technical Manual PDF

Basadur’s Innovative Process

The Simplex Process, developed by management and creativity expert Min Basadur, gained recognition through his influential book “The Power of Innovation” published in 1995.

It consists of a sequence of eight steps organized into three distinct stages:

- Problem Formulation

- Solution Formulation

- Solution Implementation

You might hear Bsadur’s Innovative Process referred to by a few variations:

- Simplex Creative Problem Solving

- Basadur SIMPLEX Problem Solving Process

- Basadur System of innovation and creative problem solving

- Simplexity Thinking Process

What is Basadur’s Innovative Process

Here is how Basadur.com explains Basadur’s Innovation Process :

“The Basadur Innovation Process is an innovative thinking & creative problem solving process that separates innovation into clearly-defined steps, to take you from initial problem-finding right through to implementing the solutions you’ve created.

Its beauty is that it enables everyone to participate in an unbiased, open-minded way.

In the absence of negativity, people can think clearly and logically, building innovation confidence. A wide range of ideas can be proposed and the best ones selected, refined and executed in a spirit of openness and collaboration.

“That’s a great idea, but…”

How often have you heard this phrase? In most group decision-making processes, ideas are killed off before they’ve even got off the ground. With The Basadur Process on the other hand, judgment is deferred. Put simply, opinions on ideas don’t get in the way of ideas.”

3 Phases and 8 Steps of Basadur’s Innovative Process

The Basadur’s Innovative Process consists of three phases, subdivided into eight steps:

Phase 1: Problem Formulation

Problem Formulation : This phase focuses on understanding and defining the problem accurately. It involves the following steps:

- Step 1 : Problem Finding . Actively anticipate and seek out problems, opportunities, and possibilities. Maintain an open mind and view problems as opportunities for proactive resolution. Identify fuzzy situations and recognize that they can open new doors.

- Step 2 : Fact Finding . Gather relevant information and facts related to the fuzzy situation. Seek multiple viewpoints, challenge assumptions, listen to others, and focus on finding the truth rather than personal opinions. Utilize different lines of questioning to clarify the situation.

- Step 3 : Problem Definition . Define the problem accurately and objectively. View the problem from different angles and consider new perspectives. Uncover fresh challenges and recognize that the perceived problem might not be the real issue.

Phase 2: Solution Formulation

Solution Formulation . Once the problem is well-defined, this phase revolves around generating and evaluating potential solutions. The steps involved are:

- Step 4 : Idea Finding . Generate ideas to solve the defined problem. Continuously seek more and better ideas, build upon half-formed ideas, and consider ideas from others. Fine-tune seemingly radical or impossible ideas to make them workable solutions.

- Step 5 : Evaluate & Select . Evaluate and select the most promising ideas to convert them into practical solutions. Consider multiple criteria in an unbiased manner, creatively improve imperfect solutions, and re-evaluate them.

Phase 3: Solution Implementation

Solution Implementation . In the final phase, the focus shifts to implementing and executing the selected solution effectively. The steps in this phase include:

- Step 6 : Plan Devise specific measures and create a concrete plan for implementing the chosen solution. Visualize the end result and motivate others to participate and support the plan.

- Step 7 : Acceptance Gain acceptance for the solutions and plans. Communicate the benefits of the solution to others, address potential concerns, and continuously revise and improve the solution to minimize resistance to change.

- Step 8 : Action Implement the solutions and put the plan into action. Avoid getting stuck in unimportant details, adapt the solutions to specific circumstances, and garner support for the change. Emphasize the need for follow-up to ensure lasting and permanent changes.

The SIMPLEX process recognizes that implementing a solution can reveal new problems, opportunities, and possibilities, leading back to Step 1 and initiating the iterative problem-solving and innovation cycle again.

Where to Go for More on Basadur’s Innovation Process

- Basadur’s Innovative Process Home

- Simplexity Thinking Explained

- Ambasadur Affiliate Program

Synectics is a problem-solving and creative thinking approach that emphasizes the power of collaboration, analogy, and metaphorical thinking. It was developed in the 1960s by George M. Prince and William J.J. Gordon.

Synectics is based on the belief that the most innovative ideas and solutions arise from the integration of diverse perspectives and the ability to make connections between seemingly unrelated concepts.

The Story of Synetics

Here is the story of Syentics according to SyneticsWorld.com:

“Back in the 1950s, our founders Bill Gordon, George Prince and their team studied thousands of hours of tape recorded innovation sessions to find the answer to

‘What is really going on between the people in the group to help them create and implement successfully?’

They called the answer the Synectics Creative-Problem-Solving Methodology, which has expanded into the Synecticsworld’s expertise on how people work creatively and collaboratively to create innovative solutions to some of the world’s most difficult challenges.

The unique Synecticsworld innovation process to the art of problem solving has taken us to many different destinations. We have worked on assignments in both the public and private sectors, in product and service innovation, business process improvement, cost reduction and the reinvention of business models and strategies.

It is our on-going goal to guide and inspire our clients to engage the Synectics innovation process to create innovative ideas, innovative solutions, and activate new, powerful, and innovative solutions.”

Why Synetics?

Synectics addresses challenges of the original Creative Problem Solving process by introducing a unique set of tools and techniques that foster creative thinking and overcome mental barriers.

Here’s how Synectics addresses some common challenges of the original Creative Problem Solving process:

- Breaking Mental Barriers : Synectics recognizes that individuals often have mental blocks and preconceived notions that limit their thinking. It tackles this challenge by encouraging the use of analogies, metaphors, and connections to break through these barriers. By exploring unrelated concepts and drawing parallels, participants can generate fresh perspectives and innovative solutions.

- Promoting Divergent Thinking : The original CPS process may sometimes struggle to foster a truly divergent thinking environment where participants feel comfortable expressing unconventional ideas. Synectics creates a safe and non-judgmental space for participants to freely explore and share their thoughts, regardless of how unusual or unconventional they may seem. This encourages a wider range of ideas and increases the potential for breakthrough solutions.

- Enhancing Collaboration : Synectics emphasizes the power of collaboration and the integration of diverse perspectives. It recognizes that innovation often emerges through the interaction of different viewpoints and experiences. By actively engaging participants in collaborative brainstorming sessions and encouraging them to build upon each other’s ideas, Synectics enhances teamwork and collective problem-solving.

- Stimulating Creative Connections : While the original CPS process focuses on logical problem-solving techniques, Synectics introduces the use of analogy and metaphorical thinking. By encouraging participants to find connections between seemingly unrelated concepts, Synectics stimulates creative thinking and opens up new possibilities. This approach helps overcome fixed thinking patterns and encourages participants to explore alternative perspectives and solutions.

- Encouraging Unconventional Solutions : Synectics acknowledges that unconventional ideas can lead to breakthrough solutions. It provides a framework that supports the exploration of unorthodox approaches and encourages participants to think beyond traditional boundaries. By challenging the status quo and embracing innovative thinking, Synectics enables the generation of unique and impactful solutions.

Synectics complements and expands upon the original CPS process by offering additional tools and techniques that specifically address challenges related to mental barriers, divergent thinking, collaboration, creative connections, and unconventional solutions.

It provides a structured approach to enhance creativity and problem-solving in a collaborative setting.

Synetic Sessions

In the Synectics process, individuals or teams engage in structured brainstorming sessions, often referred to as “synectic sessions.”

These sessions encourage participants to think beyond conventional boundaries and explore novel ways of approaching a problem or challenge.

The approach involves creating an open and non-judgmental environment where participants feel free to express their ideas and build upon each other’s contributions.

Synectics incorporates the use of analogies and metaphors to stimulate creative thinking. Participants are encouraged to make connections between unrelated concepts, draw parallels from different domains, and explore alternative perspectives.

This approach helps to break mental barriers, unlock new insights, and generate innovative ideas.

Steps of the Synetics Process

The Synectics process typically involves the following steps:

- Problem Identification : Clearly defining the problem or challenge that needs to be addressed.

- Idea Generation: Engaging in brainstorming sessions to generate a wide range of ideas, including both conventional and unconventional ones.

- Analogy and Metaphor Exploration : Encouraging participants to explore analogies, metaphors, and connections to stimulate new ways of thinking about the problem.

- Idea Development: Refining and developing the most promising ideas generated during the brainstorming process.

- Solution Evaluation : Assessing and evaluating the potential feasibility, effectiveness, and practicality of the developed ideas.

- Implementation Planning : Creating a detailed action plan to implement the chosen solution or ideas.

Synectics has been used in various fields, including business, design, education, and innovation. It is particularly effective when addressing complex problems that require a fresh perspective and the integration of diverse viewpoints.

Example of How Synetics Explores Analogies and Metaphors

Here’s an example of how Synectics utilizes analogy and metaphor exploration to stimulate new ways of thinking about a problem:

Let’s say a team is tasked with improving customer service in a retail store. During a Synectics session, participants may be encouraged to explore analogies and metaphors related to customer service. For example:

- Analogy : The participants might be asked to think of customer service in terms of a restaurant experience. They can draw parallels between the interactions between waitstaff and customers in a restaurant and the interactions between retail associates and shoppers. By exploring this analogy, participants may uncover insights and ideas for enhancing the customer experience in the retail store, such as personalized attention, prompt service, or creating a welcoming ambiance.

- Metaphor : Participants could be prompted to imagine customer service as a journey or a road trip. They can explore how different stages of the journey, such as initial contact, assistance during the shopping process, and follow-up after purchase, can be improved to create a seamless and satisfying experience. This metaphorical exploration may lead to ideas like providing clear signage, offering assistance at every step, or implementing effective post-purchase support.

Through analogy and metaphor exploration, Synectics encourages participants to think beyond the immediate context and draw inspiration from different domains .

By connecting disparate ideas and concepts , new perspectives and innovative solutions can emerge.

These analogies and metaphors serve as creative triggers that unlock fresh insights and generate ideas that may not have been considered within the confines of the original problem statement.

SCAMPER is a creative thinking technique that provides a set of prompts or questions to stimulate idea generation and innovation. It was developed by Bob Eberle and is widely used in problem-solving, product development, and brainstorming sessions.

SCAMPER provides a structured framework for creatively examining and challenging existing ideas, products, or processes.

Recognizing the value of Alex Osterman’s original checklist, Bob Eberle skillfully organized it into meaningful and repeatable categories. This thoughtful refinement by Eberle has made SCAMPER a practical and highly effective tool for expanding possibilities, breaking through creative blocks, and sparking new insights.

By systematically applying each prompt, individuals or teams can generate a wide range of possibilities and discover innovative solutions to problems or opportunities.

What Does SCAMPER Stand For?

Each letter in the word “SCAMPER” represents a different prompt to encourage creative thinking and exploration of ideas.

Here’s what each letter stands for:

- S – Substitute : Consider substituting a component, material, process, or element with something different to generate new ideas.

- C – Combine : Explore possibilities by combining or merging different elements, ideas, or features to create something unique.

- A – Adapt : Identify ways to adapt or modify existing ideas, products, or processes to fit new contexts or purposes.

- M – Modify : Examine how you can modify or change various attributes, characteristics, or aspects of an idea or solution to enhance its functionality or performance.

- P – Put to another use : Explore alternative uses or applications for an existing idea, object, or resource to uncover new possibilities.

- E – Eliminate : Consider what elements, features, or processes can be eliminated or removed to simplify or streamline an idea or solution.

- R – Reverse or Rearrange : Think about reversing or rearranging the order, sequence, or arrangement of components or processes to generate fresh perspectives and uncover innovative solutions.

Example of SCAMPER

Let’s take a simple and relatable challenge of improving the process of making breakfast sandwiches. We can use SCAMPER to generate ideas for enhancing this routine:

- S – Substitute : What can we substitute in the breakfast sandwich-making process? For example, we could substitute the traditional bread with a croissant or a tortilla wrap to add variety.

- C – Combine : How can we combine different ingredients or flavors to create unique breakfast sandwiches? We could combine eggs, bacon, and avocado to create a delicious and satisfying combination.

- A – Adapt: How can we adapt the breakfast sandwich-making process to fit different dietary preferences? We could offer options for gluten-free bread or create a vegan breakfast sandwich using plant-based ingredients.

- M – Modify : How can we modify the cooking method or preparation techniques for the breakfast sandwich? We could experiment with different cooking techniques like grilling or toasting the bread to add a crispy texture.

- P – Put to another use : How can we repurpose breakfast sandwich ingredients for other meals or snacks? We could use the same ingredients to create a breakfast burrito or use the bread to make croutons for a salad.

- E – Eliminate : What unnecessary steps or ingredients can we eliminate to simplify the breakfast sandwich-making process? We could eliminate the need for butter by using a non-stick pan or omit certain condiments to streamline the assembly process.

- R – Reverse or Rearrange : How can we reverse or rearrange the order of ingredients for a unique twist? We could reverse the order of ingredients by placing the cheese on the outside of the sandwich to create a crispy cheese crust.

These are just a few examples of how SCAMPER prompts can spark ideas for improving the breakfast sandwich-making process.

The key is to think creatively and explore possibilities within each prompt to generate innovative solutions to the challenge at hand.

Design Thinking

Design thinking provides a structured framework for creative problem-solving, with an emphasis on human needs and aspirations .

It’s an iterative process that allows for continuous learning , adaptation , and improvement based on user feedback and insights.

Here are some key ways to think about Design Thinking:

- Design thinking is an iterative and human-centered approach to problem-solving and innovation. It’s a methodology that draws inspiration from the design process to address complex challenges and create innovative solutions.

- Design thinking places a strong emphasis on understanding the needs and perspectives of the end-users or customers throughout the problem-solving journey.

- Design thinking is a collaborative and interdisciplinary process . It encourages diverse perspectives and cross-functional collaboration to foster innovation. It can be applied to a wide range of challenges, from product design and service delivery to organizational processes and social issues.

What is the Origin of Design Thinking

The origin of Design Thinking can be traced back to the work of various scholars and practitioners over several decades.

While it has evolved and been influenced by multiple sources, the following key influences are often associated with the development of Design Thinking:

- Herbert A. Simon : In the 1960s, Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon emphasized the importance of “satisficing” in decision-making and problem-solving. His work focused on the iterative nature of problem-solving and the need for designers to explore various alternatives before arriving at the optimal solution.

- Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber : In the 1970s, Rittel and Webber introduced the concept of “wicked problems,” which are complex and ill-defined challenges that do not have clear solutions. They highlighted the need for a collaborative and iterative approach to tackling these wicked problems, which aligns with the principles of Design Thinking.

- David Kelley and IDEO : Design firm IDEO, co-founded by David Kelley, played a significant role in popularizing Design Thinking. IDEO embraced an interdisciplinary and human-centered approach to design, focusing on empathy, rapid prototyping, and iteration. IDEO’s successful design projects and methodologies have influenced the development and adoption of Design Thinking across various industries.

- Stanford University : Stanford University’s d.school (Hasso Plattner Institute of Design) has been instrumental in advancing Design Thinking. The d.school has developed educational programs and frameworks that emphasize hands-on experiential learning, collaboration, and empathy in problem-solving. It has played a significant role in spreading the principles of Design Thinking globally.

While these influences have contributed to the emergence and development of Design Thinking, it’s important to note that Design Thinking is an evolving and multidisciplinary approach.

It continues to be shaped by practitioners, scholars, and organizations who contribute new ideas and insights to its principles and methodologies.

Key Principles of Design Thinking

Here are key principles of Design Thinking:

- Empathy : Design thinking begins with developing a deep understanding of the needs, emotions, and experiences of the people for whom you are designing solutions. Empathy involves active listening, observation, and engaging with users to gain insights and uncover unmet needs.

- Define the Problem : In this phase, the problem is defined and reframed based on the insights gained through empathy. The focus is on creating a clear problem statement that addresses the users’ needs and aspirations.

- Ideation : The ideation phase involves generating a wide range of ideas without judgment or criticism. It encourages divergent thinking, creativity, and the exploration of various possibilities to solve the defined problem.

- Prototyping : In this phase, ideas are translated into tangible prototypes or representations that can be tested and evaluated. Prototypes can be physical objects, mock-ups, or even digital simulations. The goal is to quickly and cost-effectively bring ideas to life for feedback and iteration.

- Testing and Iteration : Prototypes are tested with end-users to gather feedback, insights, and validation. The feedback received is used to refine and iterate the design, making improvements based on real-world observations and user input.

- Implementation : Once the design has been refined and validated through testing, it is implemented and brought to life. This phase involves planning for execution, scaling up, and integrating the solution into the intended context.

Where to Go for More on Design Thinking

There are numerous resources available to learn more about design thinking. Here are three highly regarded resources that can provide a solid foundation and deeper understanding of the subject:

- “Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work” (Book) – Nigel Cross: This book offers a comprehensive overview of design thinking, exploring its history, principles, and methodologies. Nigel Cross, a renowned design researcher, delves into the mindset and processes of designers, providing insights into their approaches to problem-solving and creativity.

- IDEO U : IDEO U is an online learning platform created by IDEO, a leading design and innovation firm. IDEO U offers a range of courses and resources focused on design thinking and innovation. Their courses provide practical guidance, case studies, and interactive exercises to deepen your understanding and application of design thinking principles.

- Stanford d.school Virtual Crash Course : The Stanford d.school offers a free Virtual Crash Course in design thinking. This online resource provides an introduction to the principles and process of design thinking through a series of videos and activities. It covers topics such as empathy, ideation, prototyping, and testing. The Virtual Crash Course is a great starting point for beginners and offers hands-on learning experiences.

These resources offer diverse perspectives and practical insights into design thinking, equipping learners with the knowledge and tools to apply design thinking principles to their own projects and challenges.

Additionally, exploring case studies and real-life examples of design thinking applications in various industries can further enhance your understanding of its effectiveness and potential impact.

Dr. John Martin on “Psychological” vs. “Procedural” Approach

Dr. John Martin of the Open University in the UK offers an insightful perspective on how various Creative Problem Solving and Brainstorming techniques differ.

In his notes for the Creative Management module of their MBA Course in 1997, he states:

“In practice, different schools of creativity training borrow from one another. The more elaborate forms of creative problem-solving, such as the Buffalo CPS method (basically brainstorming), incorporate quite a number of features found in Synectics.

However there is still a discernible split between the ‘psychological’ approaches such as Synectics that emphasize metaphor, imagery, emotion, energy etc. and ‘procedural’ approaches that concentrate on private listings, round robins etc.. Of course practitioners can combine these techniques, but there is often a discernible bias towards one or other end of the spectrum”

Brainstorming was the original Creative Problem-solving Technique, developed in the 1930s by Alex Osborn (the O of the advertising agency BBDO) and further developed by Professor Sidney Parnes of the Buffalo Institute.

The Osborn-Parnes model is the most widely practised form of brainstorming, though the word has become a generic term for any attempt to generate new ideas in an environment of suspending judgement. It may include elements of other techniques, such as de Bono’s Lateral Thinking.”

Creative Problem Solving vs. Brainstorming vs. Lateral Thinking

Creative Problem Solving, brainstorming, and lateral thinking are distinct approaches to generating ideas and solving problems. Here’s a summary of their differences:

Creative Problem Solving:

- Involves a systematic approach to problem-solving, typically following stages such as problem identification, idea generation, solution development, and implementation planning.

- Focuses on understanding the problem deeply, analyzing data, and generating a wide range of potential solutions.

- Encourages both convergent thinking (evaluating and selecting the best ideas) and divergent thinking (generating multiple ideas).

- Incorporates structured techniques and frameworks to guide the problem-solving process, such as the Osborn-Parnes model.

Brainstorming:

- A specific technique within Creative Problem Solving, developed by Alex Osborn, which aims to generate a large quantity of ideas in a short amount of time.

- Involves a group of individuals openly sharing ideas without judgment or criticism.

- Emphasizes quantity over quality, encouraging participants to build upon each other’s ideas and think creatively.

- Typically involves following guidelines, such as deferring judgment, encouraging wild ideas, and combining and improving upon suggestions.

Lateral Thinking (Edward de Bono’s Lateral Thinking):

- Introduced by Edward de Bono, lateral thinking is a deliberate and structured approach to thinking differently and generating innovative ideas.

- Involves deliberately challenging traditional thinking patterns and assumptions to arrive at unconventional solutions.

- Encourages the use of techniques like random stimulation, provocative statements, and deliberate provocation to shift perspectives and break fixed thought patterns.

- Focuses on generating out-of-the-box ideas that may not arise through traditional problem-solving methods.

While there can be overlaps and combinations of these approaches in practice, each approach has its distinct emphasis and techniques.

Creative Problem Solving provides a structured framework for problem-solving, brainstorming emphasizes idea generation within a group setting, and lateral thinking promotes thinking outside the box to arrive at unconventional solutions.

Creative Problem Solving Empowers You to Change Your World

The Creative Problem Solving process is a valuable framework that enables individuals and teams to approach complex problems with a structured and creative mindset.

By following the stages of clarifying the problem, generating ideas, developing solutions, implementing the chosen solution, and evaluating the outcomes, the process guides participants through a systematic and iterative journey of problem-solving.

Throughout this deep dive, we’ve explored the essence of Creative Problem Solving, its key stages, and variations. We’ve seen how different methodologies, such as Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving, FourSight Thinking Profiles, Basadur’s Innovative Process, Synectics, SCAMPER, and Design Thinking, offer unique perspectives and techniques to enhance the creative problem-solving experience.

By embracing these frameworks and techniques, individuals and teams can tap into their creative potential , break free from conventional thinking patterns, and unlock innovative solutions.

Creative Problem Solving empowers us to approach challenges with curiosity, open-mindedness, and a collaborative spirit , fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement.

Remember, creative problem solving is a skill that can be developed and honed over time. By adopting a flexible and adaptable mindset , embracing diverse perspectives, and applying various creativity tools, we can navigate the complexities of problem-solving and uncover solutions that drive positive change.

Let’s enjoy our creative problem-solving journey by embracing the unknown and transforming challenges into opportunities for growth and innovation.

You Might Also Like

Frameworks Library 10 Best Change Management Frameworks 10 Best Go-to-Market Frameworks 10 Best Innovation Frameworks 10 Best Marketing Frameworks Appreciative Inquiry vs. Problem Solving Orientation

About JD Meier

I help leaders change the world.

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

How to Be a More Creative Problem-Solver at Work: 8 Tips

- 01 Mar 2022

The importance of creativity in the workplace—particularly when problem-solving—is undeniable. Business leaders can’t approach new problems with old solutions and expect the same result.

This is where innovation-based processes need to guide problem-solving. Here’s an overview of what creative problem-solving is, along with tips on how to use it in conjunction with design thinking.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Encountering problems with no clear cause can be frustrating. This occurs when there’s disagreement around a defined problem or research yields unclear results. In such situations, creative problem-solving helps develop solutions, despite a lack of clarity.

While creative problem-solving is less structured than other forms of innovation, it encourages exploring open-ended ideas and shifting perspectives—thereby fostering innovation and easier adaptation in the workplace. It also works best when paired with other innovation-based processes, such as design thinking .

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Design thinking is a solutions-based mentality that encourages innovation and problem-solving. It’s guided by an iterative process that Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar outlines in four stages in the online course Design Thinking and Innovation :

- Clarify: This stage involves researching a problem through empathic observation and insights.

- Ideate: This stage focuses on generating ideas and asking open-ended questions based on observations made during the clarification stage.

- Develop: The development stage involves exploring possible solutions based on the ideas you generate. Experimentation and prototyping are both encouraged.

- Implement: The final stage is a culmination of the previous three. It involves finalizing a solution’s development and communicating its value to stakeholders.

Although user research is an essential first step in the design thinking process, there are times when it can’t identify a problem’s root cause. Creative problem-solving addresses this challenge by promoting the development of new perspectives.

Leveraging tools like design thinking and creativity at work can further your problem-solving abilities. Here are eight tips for doing so.

8 Creative Problem-Solving Tips

1. empathize with your audience.

A fundamental practice of design thinking’s clarify stage is empathy. Understanding your target audience can help you find creative and relevant solutions for their pain points through observing them and asking questions.

Practice empathy by paying attention to others’ needs and avoiding personal comparisons. The more you understand your audience, the more effective your solutions will be.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

If a problem is difficult to define, reframe it as a question rather than a statement. For example, instead of saying, "The problem is," try framing around a question like, "How might we?" Think creatively by shifting your focus from the problem to potential solutions.

Consider this hypothetical case study: You’re the owner of a local coffee shop trying to fill your tip jar. Approaching the situation with a problem-focused mindset frames this as: "We need to find a way to get customers to tip more." If you reframe this as a question, however, you can explore: "How might we make it easier for customers to tip?" When you shift your focus from the shop to the customer, you empathize with your audience. You can take this train of thought one step further and consider questions such as: "How might we provide a tipping method for customers who don't carry cash?"

Whether you work at a coffee shop, a startup, or a Fortune 500 company, reframing can help surface creative solutions to problems that are difficult to define.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

If you encounter an idea that seems outlandish or unreasonable, a natural response would be to reject it. This instant judgment impedes creativity. Even if ideas seem implausible, they can play a huge part in ideation. It's important to permit the exploration of original ideas.

While judgment can be perceived as negative, it’s crucial to avoid accepting ideas too quickly. If you love an idea, don’t immediately pursue it. Give equal consideration to each proposal and build on different concepts instead of acting on them immediately.

4. Overcome Cognitive Fixedness

Cognitive fixedness is a state of mind that prevents you from recognizing a situation’s alternative solutions or interpretations instead of considering every situation through the lens of past experiences.

Although it's efficient in the short-term, cognitive fixedness interferes with creative thinking because it prevents you from approaching situations unbiased. It's important to be aware of this tendency so you can avoid it.

5. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

One of the key principles of creative problem-solving is the balance of divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking is the process of brainstorming multiple ideas without limitation; open-ended creativity is encouraged. It’s an effective tool for generating ideas, but not every idea can be explored. Divergent thinking eventually needs to be grounded in reality.

Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is the process of narrowing ideas down into a few options. While converging ideas too quickly stifles creativity, it’s an important step that bridges the gap between ideation and development. It's important to strike a healthy balance between both to allow for the ideation and exploration of creative ideas.

6. Use Creative Tools

Using creative tools is another way to foster innovation. Without a clear cause for a problem, such tools can help you avoid cognitive fixedness and abrupt decision-making. Here are several examples:

Problem Stories

Creating a problem story requires identifying undesired phenomena (UDP) and taking note of events that precede and result from them. The goal is to reframe the situations to visualize their cause and effect.

To start, identify a UDP. Then, discover what events led to it. Observe and ask questions of your consumer base to determine the UDP’s cause.

Next, identify why the UDP is a problem. What effect does the UDP have that necessitates changing the status quo? It's helpful to visualize each event in boxes adjacent to one another when answering such questions.

The problem story can be extended in either direction, as long as there are additional cause-and-effect relationships. Once complete, focus on breaking the chains connecting two subsequent events by disrupting the cause-and-effect relationship between them.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool encourages you to consider how people from different backgrounds would approach similar situations. For instance, how would someone in hospitality versus manufacturing approach the same problem? This tool isn't intended to instantly solve problems but, rather, to encourage idea generation and creativity.

7. Use Positive Language

It's vital to maintain a positive mindset when problem-solving and avoid negative words that interfere with creativity. Positive language prevents quick judgments and overcomes cognitive fixedness. Instead of "no, but," use words like "yes, and."

Positive language makes others feel heard and valued rather than shut down. This practice doesn’t necessitate agreeing with every idea but instead approaching each from a positive perspective.

Using “yes, and” as a tool for further idea exploration is also effective. If someone presents an idea, build upon it using “yes, and.” What additional features could improve it? How could it benefit consumers beyond its intended purpose?

While it may not seem essential, this small adjustment can make a big difference in encouraging creativity.

8. Practice Design Thinking

Practicing design thinking can make you a more creative problem-solver. While commonly associated with the workplace, adopting a design thinking mentality can also improve your everyday life. Here are several ways you can practice design thinking:

- Learn from others: There are many examples of design thinking in business . Review case studies to learn from others’ successes, research problems companies haven't addressed, and consider alternative solutions using the design thinking process.

- Approach everyday problems with a design thinking mentality: One of the best ways to practice design thinking is to apply it to your daily life. Approach everyday problems using design thinking’s four-stage framework to uncover what solutions it yields.

- Study design thinking: While learning design thinking independently is a great place to start, taking an online course can offer more insight and practical experience. The right course can teach you important skills , increase your marketability, and provide valuable networking opportunities.

Ready to Become a Creative Problem-Solver?

Though creativity comes naturally to some, it's an acquired skill for many. Regardless of which category you're in, improving your ability to innovate is a valuable endeavor. Whether you want to bolster your creativity or expand your professional skill set, taking an innovation-based course can enhance your problem-solving.

If you're ready to become a more creative problem-solver, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses . If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

- Back to All Programs /

Creative Thinking: Innovative Solutions to Complex Challenges

Learn how to grow a culture of creativity to innovate competitive solutions.

All Start Dates

8:30 AM – 4:30 PM ET

2 consecutive days

$2,990 Programs fill quickly — free cancellation up to 14 days prior

Registration Deadline

October 8, 2024

$3,100 Programs fill quickly — free cancellation up to 14 days prior

April 22, 2025

July 8, 2025

Overview: Creative Thinking Skills Course

The tech breakthrough that makes smartphones irrelevant, a new viral ad campaign, your company’s next big revenue generator — ideas like these could be sitting in your brain; all you need are the creative thinking skills and strategies to pull them out.

This interactive program focuses explicitly on the creative thinking skills you need to solve complex problems and design innovative solutions. Learn how to transform your thinking from the standard “why can’t we” to the powerful “how might we.” Crack the code on how to consistently leverage your team’s creative potential in order to drive innovation within your organization. Explore how to build a climate for innovation, remove barriers to creativity, cultivate courage, and create more agile, proactive, and inspired teams.

You will leave this program with new ideas about how to think more productively and how to introduce creative thinking skills into your organization. You can apply key takeaways immediately to implement a new leadership vision, inspire renewed enthusiasm, and enjoy the skills and tools to tackle challenges and seize opportunities.

Innovation experts Anne Manning and Susan Robertson bring to this highly-interactive and powerful program their decades of experience promoting corporate innovation, teaching the art of creative problem solving, and applying the principles of brain science to solve complex challenges.

Who Should Take Creative Thinking Skills Training?

This program is ideal for leaders with at least 3 years of management experience. It is designed for leaders who want to develop new strategies, frameworks, and tools for creative problem solving. Whether you are a team lead, project manager, sales director, or executive, you’ll learn powerful tools to lead your team and your organization to create innovative solutions to complex challenges.

Benefits of Creative Thinking Skills Training

The goal of this creative thinking program is to help you develop the strategic concepts and tactical skills to lead creative problem solving for your team and your organization. You will learn to:

- Retrain your brain to avoid negative cognitive biases and long-held beliefs and myths that sabotage creative problem solving and innovation

- Become a more nimble, proactive, and inspired thinker and leader

- Create the type of organizational culture that supports collaboration and nurtures rather than kills ideas

- Gain a practical toolkit for solving the “unsolvable” by incorporating creative thinking into day-to-day processes

- Understand cognitive preferences (yours and others’) to adapt the creative thinking process and drive your team’s success

- Develop techniques that promote effective brainstorming and enable you to reframe problems in a way that inspires innovative solutions

All participants will earn a Certificate of Completion from the Harvard Division of Continuing Education.

The curriculum in this highly interactive program utilizes research-based methodologies and techniques to build creative thinking skills and stimulate creative problem solving.

Through intensive group discussions and small-group exercises, you will focus on topics such as:

- The Creative Problem Solving process: a researched, learnable, repeatable process for uncovering new and useful ideas. This process includes a “how to” on clarifying, ideating, developing, and implementing new solutions to intractable problems

- The cognitive preferences that drive how we approach problems, and how to leverage those cognitive preferences for individual and team success

- How to develop—and implement— a methodology that overcomes barriers to innovative thinking and fosters the generation of new ideas, strategies, and techniques

- The role of language, including asking the right questions, in reframing problems, challenging assumptions, and driving successful creative problem solving

- Fostering a culture that values, nurtures, and rewards creative solutions

Considering this program?

Send yourself the details.

Related Programs

- Design Thinking: Creating Better Customer Experiences

- Agile Leadership: Transforming Mindsets and Capabilities in Your Organization

October Schedule

- Creative Challenges: A Team Sport

- The Place to Begin: Reframe the Challenge

- Ideas on Demand

- Building a Creative Organization

April Schedule

July schedule, instructors, anne manning, susan robertson.

I really enjoyed the way the instructors facilitated the program. The combination of theory and practical exercises was powerful and effectively reinforced the concepts.

Innovation and Educational Research, Director, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Certificates of Leadership Excellence

The Certificates of Leadership Excellence (CLE) are designed for leaders with the desire to enhance their business acumen, challenge current thinking, and expand their leadership skills.

This program is one of several CLE qualifying programs. Register today and get started earning your certificate.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Table of Contents

What is creative problem-solving?

An introduction to creative problem-solving.

Creative problem-solving is an essential skill that goes beyond basic brainstorming . It entails a holistic approach to challenges, melding logical processes with imaginative techniques to conceive innovative solutions. As our world becomes increasingly complex and interconnected, the ability to think creatively and solve problems with fresh perspectives becomes invaluable for individuals, businesses, and communities alike.

Importance of divergent and convergent thinking

At the heart of creative problem-solving lies the balance between divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking encourages free-flowing, unrestricted ideation, leading to a plethora of potential solutions. Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is about narrowing down those options to find the most viable solution. This dual approach ensures both breadth and depth in the problem-solving process.