2024 Theses Doctoral

Coordination of histone chaperones for parental histone segregation and epigenetic inheritance

Fang, Yimeng

Epigenetics involves heritable changes in an individual’s traits resulting from variations in gene expression without alterations to the DNA sequence. In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is usually folded with histones into chromatin. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) on histones not only play crucial roles in regulating various biological processes, including gene expression, but also store the majority of epigenetic information. A fundamental question in this field is how cells transmit these PTMs to their progeny. Before I began my thesis research, a well-established dogma in the field was that parental histones containing PTMs are symmetrically distributed to daughter DNA strands during DNA replication. These modified histones serve as templates for PTM duplication, thereby restoring the original chromatin states on both daughter strands. Several histone chaperones have been identified as regulators of parental histone segregation. However, their impact on epigenetic inheritance is controversial, which I reasoned is due to the lack of proper systems to examine epigenetic inheritance. This prompted me to use the unique characteristics of fission yeast heterochromatin as a model of epigenetic inheritance. In this organism, heterochromatin formation involves two distinct steps: establishment and inheritance. Reporter systems have been established to allow precise examination of heterochromatin inheritance. However, parental histone segregation pathways have not been characterized in this organism, and their impact on heterochromatin inheritance is unknown. My thesis work investigates the role of parental histone chaperones in regulating parental histone segregation and epigenetic inheritance in fission yeast. It comprises 5 chapters: Chapter 1 introduces epigenetics, with a focus on chromatin-based epigenetic inheritance. It also highlights the unique features of fission yeast heterochromatin that make it an excellent model for studying epigenetic inheritance.Chapter 2 is the focus of my thesis work. I employed inheritance-specific reporters in fission yeast to investigate the roles of three parental histone chaperones on epigenetic inheritance. In addition, in collaboration with Dr. Zhiguo Zhang’s lab, I adapted the Enrichment and Sequencing of Protein-Associated Nascent DNA (eSPAN) method, a recently developed technique designed to quantify the bias of specific proteins at replication forks, to examine parental histone segregation in fission yeast. My analyses demonstrated a critical role for parental histone segregation in epigenetic inheritance. Moreover, I discovered that both the symmetric segregation of parental histones and their density on daughter strands are critical for this process. Chapter 3 uncovers a novel function of a DNA replication protein Mrc1 in regulating epigenetic inheritance, distinct from its established roles in DNA replication checkpoint activation and replication speed control. I demonstrated the critical role of Mrc1 in regulating the symmetrical transfer of parental histone and the proper inheritance of heterochromatin. These results provide essential mechanistic insights into the function of Mrc1. Chapter 4 explores the function of an additional DNA replication protein and histone chaperone, Swi7 (Pol alpha). I have found that mutations in Swi7 lead to defects in parental histone segregation and heterochromatin inheritance, laying a strong foundation to further investigate its mechanism of action. Chapter 5 discusses potential future research directions that can build upon my thesis work.In conclusion, my thesis represents a thorough examination of parental histone chaperones in regulating epigenetic inheritance in fission yeast. By combining innovative genetic assays and advanced methodologies such as eSPAN, I have provided critical insights into the molecular mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance. In addition, the assays that I have developed during my thesis work also pave the way for future studies aimed at elucidating the mechanism of epigenetic inheritance in this important model organism.

- Epigenetics

- Gene expression

- Nucleotide sequence

- DNA replication

This item is currently under embargo. It will be available starting 2026-08-01.

More About This Work

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

You are using an unsupported browser ×

You are using an unsupported browser. This web site is designed for the current versions of Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Safari.

Site Feedback

The Office of the Federal Register publishes documents on behalf of Federal agencies but does not have any authority over their programs. We recommend you directly contact the agency associated with the content in question.

If you have comments or suggestions on how to improve the www.ecfr.gov website or have questions about using www.ecfr.gov, please choose the 'Website Feedback' button below.

If you would like to comment on the current content, please use the 'Content Feedback' button below for instructions on contacting the issuing agency

Website Feedback

- Incorporation by Reference

- Recent Updates

- Recent Changes

- Corrections

- Reader Aids Home

- Using the eCFR Point-in-Time System

- Understanding the eCFR

- Government Policy and OFR Procedures

- Developer Resources

- My Subscriptions

- Sign In / Sign Up

Hi, Sign Out

The Electronic Code of Federal Regulations

Enhanced content :: cross reference.

Enhanced content is provided to the user to provide additional context.

Navigate by entering citations or phrases (eg: suggestions#fillExample" class="example badge badge-info">1 CFR 1.1 suggestions#fillExample" class="example badge badge-info">49 CFR 172.101 suggestions#fillExample" class="example badge badge-info">Organization and Purpose suggestions#fillExample" class="example badge badge-info">1/1.1 suggestions#fillExample" class="example badge badge-info">Regulation Y suggestions#fillExample" class="example badge badge-info">FAR ).

Choosing an item from citations and headings will bring you directly to the content. Choosing an item from full text search results will bring you to those results. Pressing enter in the search box will also bring you to search results.

Background and more details are available in the Search & Navigation guide.

- Title 26 —Internal Revenue

- Chapter I —Internal Revenue Service, Department of the Treasury

- Subchapter A —Income Tax

- Part 1 —Income Taxes

- Rules for Computing Credit for Investment in Certain Depreciable Property

Enhanced Content - Table of Contents

The in-page Table of Contents is available only when multiple sections are being viewed.

Use the navigation links in the gray bar above to view the table of contents that this content belongs to.

Enhanced Content - Details

26 U.S.C. 7805 , unless otherwise noted. Section 1.1(h)-1 also issued under 26 U.S.C. 1(h) ; Section 1.21-1 also issued under 26 U.S.C. 21(f) ; See Part 1 for more

T.D. 6500, 25 FR 11402 , Nov. 26, 1960; 25 FR 14021 , Dec. 21, 1960; T.D. 9989, 89 FR 17606 , Mar. 11, 2024, unless otherwise noted. T.D. 6500, 25 FR 11402 , Nov. 26, 1960; 25 FR 14021 , Dec. 21, 1960, unless otherwise noted. T.D. 6500, 25 FR 11402 , Nov. 26, 1960; 25 FR 14021 , Dec. 31, 1960, T.D. 9381, 73 FR 8604 , Feb. 15, 2008, unless otherwise noted. See Part 1 for more

Enhanced Content - Print

Generate PDF

This content is from the eCFR and may include recent changes applied to the CFR. The official, published CFR, is updated annually and available below under "Published Edition". You can learn more about the process here .

Enhanced Content - Display Options

The eCFR is displayed with paragraphs split and indented to follow the hierarchy of the document. This is an automated process for user convenience only and is not intended to alter agency intent or existing codification.

A separate drafting site is available with paragraph structure matching the official CFR formatting. If you work for a Federal agency, use this drafting site when drafting amendatory language for Federal regulations: switch to eCFR drafting site .

Enhanced Content - Subscribe

Subscribe to: 26 CFR 1.47-2

Enhanced Content - Timeline

No changes found for this content after 1/03/2017.

Enhanced Content - Go to Date

Enhanced content - compare dates, enhanced content - published edition.

View the most recent official publication:

- View Title 26 on govinfo.gov

- View the PDF for 26 CFR 1.47-2

These links go to the official, published CFR, which is updated annually. As a result, it may not include the most recent changes applied to the CFR. Learn more .

Enhanced Content - Developer Tools

This document is available in the following developer friendly formats:

- Hierarchy JSON - Title 26

- Content HTML - Section 1.47-2

- Content XML - Section 1.47-2

Information and documentation can be found in our developer resources .

eCFR Content

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is the official legal print publication containing the codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the departments and agencies of the Federal Government. The Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR) is a continuously updated online version of the CFR. It is not an official legal edition of the CFR.

§ 1.47-2 “Disposition” and “cessation”.

( a ) General rule —

( 1 ) “Disposition”. For purposes of this section and § 1.47-1 and §§ 1.47-3 through 1.47-6 , the term “disposition” includes a sale in a sale-and-leaseback transaction, a transfer upon the foreclosure of a security interest and a gift, but such term does not include a mere transfer of title to a creditor upon creation of a security interest. See paragraph (g) of § 1.47-3 for treatment of certain sale-and-leaseback transactions.

( 2 ) “Cessation”.

( i ) A determination of whether section 38 property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to the taxpayer must be made for each taxable year subsequent to the credit year. Thus, in each such taxable year the taxpayer must determine, as if such property were placed in service in such taxable year, whether such property would qualify as section 38 property (within the meaning of § 1.48-1 ) in the hands of the taxpayer for such taxable year.

( ii ) Section 38 property does not cease to be section 38 property with respect to the taxpayer in any taxable year subsequent to the credit year merely because under the taxpayer's depreciation practice no deduction for depreciation with respect to such property is allowable to the taxpayer for the taxable year, provided that the property continues to be used in the taxpayer's trade or business (or in the production of income) and otherwise qualifies as section 38 property with respect to the taxpayer.

( iii ) This subparagraph may be illustrated by the following examples:

A, an individual who makes his returns on the basis of the calendar year, on January 1, 1962, acquired and placed in service in his trade or business an item of section 38 property with an estimated useful life of eight years. On January 1, 1965, A removes the item of section 38 property from use in his trade or business by converting such item to personal use. Therefore no deduction for depreciation with respect to such item of property is allowable to A for the taxable year 1965. On January 1, 1965, such item of property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to A.

On January 1, 1965, A placed in service an item of section 38 property with a basis of $10,000 and an estimated useful life of 4 years. A depreciates such item, which has a salvage value of $2,000 (after taking into account section 167(f)), on the declining balance method at a rate of 50 percent (that is, twice the straight line rate of 25 percent). With respect to such item, A is allowed deductions for depreciation of $5,000 for 1965, $2,500 for 1966, and $500 for 1967. A is not allowed a deduction for depreciation for 1968 although he continues to use such item in his trade or business. Such item does not cease to be section 38 property with respect to A in 1968.

( b ) Leased property —

( 1 ) In general. For purposes of paragraph (a) of § 1.47-1 , generally the mere leasing of section 38 property by a lessor who took the basis of such property into account in computing his qualified investment for the credit year shall not be considered to be a disposition. However, in a case where a lease is treated as a sale for income tax purposes such transaction is considered to be a disposition. Leased section 38 property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to the lessor if, in any taxable year subsequent to the credit year, such property would not qualify as section 38 property (as defined in § 1.48-1 ) in the hands of the lessor, the lessee, or any sublessee. Thus, if, in a taxable year subsequent to the credit year, a lessee uses the property predominantly outside the United States, such property shall be considered to have ceased to be section 38 property with respect to the lessor.

( 2 ) Where lessor elects to treat lessee as purchaser. For purposes of paragraph (a) of § 1.47-1 , if, under § 1.48-4 , the lessor of new section 38 property made a valid election to treat the lessee as having purchased such property for purposes of the credit allowed by section 38, the following rules apply in determining whether such property is disposed of, or otherwise ceases to be section 38 property with respect to the lessee:

( i ) Generally, a mere disposition by the lessor of property subject to a lease shall not be considered to be a disposition by the lessee.

( ii ) If the lessor makes a disposition of property subject to a lease to a person who may not, under § 1.48-4 , make a valid election to treat the lessee as having purchased such property for purposes of the credit allowed by section 38 (such as a person described in paragraph (a)(5) of § 1.48-4 ), such property shall be considered to have ceased to be section 38 property with respect to the lessee on the date of such disposition.

( iii ) If a lease is terminated and the property is transferred by the lessee to the lessor or to any other person, such transfer shall be considered to be a disposition by the lessee.

( iv ) If the lessee actually purchases such property in the credit year or in a taxable year subsequent to the credit year, such purchase shall not be considered to be a disposition.

( v ) The property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to the lessee if in any taxable year subsequent to the credit year such property would not qualify as section 38 property (as defined in § 1.48-1 ) in the hands of the lessor, the lessee, or any sublessee. Thus, for example, if, in a taxable year subsequent to the credit year, a sublessee uses the property predominantly outside the United States, the property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to the lessee.

( c ) Reduction in basis of section 38 property —

( 1 ) General rule. If, in the credit year or in any taxable year subsequent to the credit year, the basis (or cost) of section 38 property is reduced, for example, as a result of a refund of part of the cost of the property, then such section 38 property shall be treated as having ceased to be section 38 property with respect to the taxpayer to the extent of the amount of such reduction in basis (or cost) on the date the refund which results in such reduction in basis (or cost) is received or accrued, except that for purposes of § 1.47-1(a) the actual useful life of the property treated as having ceased to be section 38 property shall be considered to be less than 3 years.

( 2 ) Example. Subparagraph (1) of this paragraph may be illustrated by the following example:

(i) On January 1, 1962, A, a cash basis taxpayer, acquired from X Cooperative an item of section 38 property with a basis of $100 and an estimated useful life of 10 years which he placed in service on such date. The amount of qualified investment with respect to such asset was $100. For the taxable year 1962 A was allowed under section 38 a credit of $7 against his liability for tax. On June 1, 1963, A receives a $10 patronage dividend from X Cooperative with respect to such asset. Under paragraph (c)(2)(i) of § 1.1385-1 , the basis of the asset in A's hands is reduced by $10.

(ii) Under subparagraph (1) of this paragraph, on June 1, 1963, the item of section 38 property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to A to the extent of $10 of the original $100 basis.

( d ) Retirements. A retirement of section 38 property, including a normal retirement (as defined in paragraph (b) of § 1.167(a)-8 , relating to definition of normal and abnormal retirements), whether from a single asset account or a multiple asset account, and an abandonment, are dispositions for purposes of paragraph (a) of § 1.47-1 .

( e ) Conversion of section 38 property to personal use.

( 1 ) If, for any taxable year subsequent to the credit year—

( i ) A deduction for depreciation is allowable to the taxpayer with respect to only a part of section 38 property because such property is partially devoted to personal use, and

( ii ) The part of the property (expressed as a percentage of its total basis (or cost)) with respect to which a deduction for depreciation is allowable for such taxable year is less than the part of the property with respect to which a deduction for depreciation was allowable in the credit year,

then such property shall be considered as having ceased to be section 38 property with respect to the taxpayer to such extent. Further, property ceases to be section 38 property with respect to the taxpayer to the extent that a deduction for depreciation thereon is disallowed under section 274 (relating to disallowance of certain entertainment, etc., expenses).

( 2 ) Examples. Subparagraph (1) of this paragraph may be illustrated by the following examples:

(i) A, a calendar-year taxpayer, acquired and placed in service on January 1, 1962, an automobile with a basis of $2,400 and an estimated useful life of four years. In the taxable year 1962 the automobile was used by A 80 percent of the time in his trade or business and was used 20 percent of the time for personal purposes. Thus, for the taxable year 1962 only 80 percent of the basis of the automobile qualified as section 38 property since a deduction for depreciation was allowable to A only with respect to 80 percent of the basis of the automobile. In the taxable year 1963 the automobile is used by A only 60 percent of the time in his trade or business. Thus, for the taxable year 1963 a deduction for depreciation is allowable to A only with respect to 60 percent of the basis of the automobile.

(ii) Under subparagraph (1) of this paragraph, on January 1, 1963, the automobile ceases to be section 38 property with respect to A to the extent of 20 percent (80 percent minus 60 percent) of the $2,400 basis of the automobile.

(i) The facts are the same as in example 1 and in addition for the taxable year 1964 a deduction for depreciation is allowable to A only with respect to 40 percent of the basis of the property.

(ii) Under subparagraph (1) of this paragraph, on January 1, 1964, the automobile ceases to be section 38 property with respect to A to the extent of 20 percent (60 percent minus 40 percent) of the $2,400 basis of the automobile.

[T.D. 6931, 32 FR 14032 , Oct. 10, 1967, as amended by T.D. 7203, 37 FR 17128 , Aug. 25, 1972]

Reader Aids

Information.

- About This Site

- Legal Status

- Accessibility

- No Fear Act

- Continuity Information

Kentucky judge dismisses core charges against two former officers connected to Breonna Taylor's death

A judge in Kentucky has dismissed core charges against two former Louisville police officials involved in the raid that ended in Breonna Taylor's death.

Judge Charles R. Simpson III of western Kentucky's U.S. District Court on Thursday said Taylor's death was triggered by the actions of her boyfriend, who opened fire when police arrived outside her Louisville apartment March 13, 2020.

Regardless of whether former Louisville Police Detective Joshua Jaynes and former Sgt. Kyle Meany wrote and approved a falsified request for a warrant, it was boyfriend Kenneth Walker 's gunfire at what he believed were intruders that caused a deadly police response, Simpson said.

Taylor, 26, was killed by officers who returned fire.

The case was already being upheld by civil rights activists as an example of police allegedly disregarding the life and rights of a Black woman when George Floyd, a Black man, was murdered by officers in Minneapolis two months later, which gave Taylor's death renewed attention.

A federal grand jury in 2022 returned indictments against Jaynes, 40, and Meany, 35, charging them with depriving Taylor of her constitutional right to be free of unreasonable searches and seizures resulting in death.

The mechanism cited in the case was Jaynes' draft of an allegedly false search warrant application, which Meany approved, that stated there was sufficient evidence tying Taylor’s residence to illicit drugs.

Jaynes was also charged with conspiracy to cover up the search warrant's lack of a foundation by allegedly creating a supporting document after the fact and then lying to investigators; and Meany was charged with lying to federal investigators.

At the time charges were announced, Attorney General Merrick B. Garland said the charges reflected the main reason the Justice Department exists — to protect Americans' civil rights.

"Those violations resulted in Ms. Taylor’s death," he said in a statement at the time. "Breonna Taylor should be alive today."

In his ruling Thursday, Simpson cited a timeline that relies on what happened at Taylor's residence after the ink on the warrant dried. Jaynes and Meany weren't at the raid, and her death was more directly tied to Walker's decision to open fire, the judge wrote.

"The Court finds that the warrantless entry was not the actual cause of Taylor’s death," he wrote in his decision. "The Court also concludes that the Death-Results charge requires proof of proximate cause and that allegations in this case show that the warrantless entry was not the proximate cause of Taylor’s death and even if it were, K.W.’s decision to open fire is the legal cause of her death, it being a superseding cause."

Simpson’s ruling effectively reduced the felony civil rights violation charges against Jaynes and Meany, which had carried a maximum sentence of life in prison, to misdemeanors

The charges related to covering up the allegedly false search warrant and lying to investigators will remain, according to the decision.

Thomas Clay, lawyer for Jaynes, said, "We are very pleased with the ruling from Judge Simpson. It takes off the table the most serious charge."

He said he expects federal prosecutors to appeal.

"We're not out of the woods yet," Clay said. "If it comes down to going to trial, I am looking forward to trying this case so the truth will come out."

Attorneys for Meany and spokespeople for the Justice Department did not respond to requests for comment from NBC News.

The U.S. Justice Department said in an email to the Associated Press that it “is reviewing the judge’s decision and assessing next steps.”

In a statement to the AP, Taylor's family said they will "continue to fight until we get full justice" for Taylor.

“Obviously we are devastated at the moment by the judge’s ruling with which we disagree and are just trying to process everything,” the statement said. It said prosecutors told the family they plan to appeal Simpson’s ruling.

The federal case also included charges against two other former Louisville police officials, Kelly Goodlett , who pleaded guilty in 2022 to conspiring to falsify the warrant application; and Brett Hankison , charged with endangering the lives of Taylor, Walker and nearby neighbors with unconstitutionally excessive force when he opened fire during the raid.

Hankinson's 2023 prosecution ended in mistrial when a jury deadlocked on the counts against him. Federal prosecutors said they plan to retry him beginning in October.

Dennis Romero is a breaking news reporter for NBC News Digital.

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Burkina Faso nationalises two gold mines mired in legal dispute

To read this article for free, register now.

Once registered, you can: • Read free articles • Get our Editor's Digest and other newsletters • Follow topics and set up personalised events • Access Alphaville: our popular markets and finance blog

Explore more offers.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism. Cancel anytime during your trial.

FT Digital Edition

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

Standard Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FT Edit app

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

- Welcome to Chapter 2

How to Critically Analyze Sources

Learning about synthesis analysis, chapter 2 webinars.

- Student Experience Feedback Buttons

- Library Guide: Research Process This link opens in a new window

- ASC Guide: Outlining and Annotating This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: RefWorks This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Copyright Information This link opens in a new window

- Library Research Consultations This link opens in a new window

Jump to DSE Guide

Need help ask us.

- Research Process An introduction to the research process.

- Determining Information Needs A Review Scholarly Journals and Other Information Sources.

- Evaluating Information Sources This page explains how to evaluate the sources of information you locate in your searches.

- Video: Doctoral Level Critique in the Literature Review This video provides doctoral candidates an overview of the importance of doctoral-level critique in the Literature Review in Chapter 2 of their dissertation.

What D oes Synthesis and Analysis Mean?

Synthesis: the combination of ideas to

- show commonalities or patterns

Analysis: a detailed examination

- of elements, ideas, or the structure of something

- can be a basis for discussion or interpretation

Synthesis and Analysis: combine and examine ideas to

- show how commonalities, patterns, and elements fit together

- form a unified point for a theory, discussion, or interpretation

- develop an informed evaluation of the idea by presenting several different viewpoints and/or ideas

- Article Spreadsheet Example (Article Organization Matrix) Use this spreadsheet to help you organize your articles as you research your topic.

Was this resource helpful?

- Next: Library Guide: Research Process >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2023 11:59 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1007176

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

- Privacy Policy

Home » Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Table of contents.

Definition:

Thesis is a scholarly document that presents a student’s original research and findings on a particular topic or question. It is usually written as a requirement for a graduate degree program and is intended to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and their ability to conduct independent research.

History of Thesis

The concept of a thesis can be traced back to ancient Greece, where it was used as a way for students to demonstrate their knowledge of a particular subject. However, the modern form of the thesis as a scholarly document used to earn a degree is a relatively recent development.

The origin of the modern thesis can be traced back to medieval universities in Europe. During this time, students were required to present a “disputation” in which they would defend a particular thesis in front of their peers and faculty members. These disputations served as a way to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and were often the final requirement for earning a degree.

In the 17th century, the concept of the thesis was formalized further with the creation of the modern research university. Students were now required to complete a research project and present their findings in a written document, which would serve as the basis for their degree.

The modern thesis as we know it today has evolved over time, with different disciplines and institutions adopting their own standards and formats. However, the basic elements of a thesis – original research, a clear research question, a thorough review of the literature, and a well-argued conclusion – remain the same.

Structure of Thesis

The structure of a thesis may vary slightly depending on the specific requirements of the institution, department, or field of study, but generally, it follows a specific format.

Here’s a breakdown of the structure of a thesis:

This is the first page of the thesis that includes the title of the thesis, the name of the author, the name of the institution, the department, the date, and any other relevant information required by the institution.

This is a brief summary of the thesis that provides an overview of the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

This page provides a list of all the chapters and sections in the thesis and their page numbers.

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the research question, the context of the research, and the purpose of the study. The introduction should also outline the methodology and the scope of the research.

Literature Review

This chapter provides a critical analysis of the relevant literature on the research topic. It should demonstrate the gap in the existing knowledge and justify the need for the research.

Methodology

This chapter provides a detailed description of the research methods used to gather and analyze data. It should explain the research design, the sampling method, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures.

This chapter presents the findings of the research. It should include tables, graphs, and charts to illustrate the results.

This chapter interprets the results and relates them to the research question. It should explain the significance of the findings and their implications for the research topic.

This chapter summarizes the key findings and the main conclusions of the research. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

This section provides a list of all the sources cited in the thesis. The citation style may vary depending on the requirements of the institution or the field of study.

This section includes any additional material that supports the research, such as raw data, survey questionnaires, or other relevant documents.

How to write Thesis

Here are some steps to help you write a thesis:

- Choose a Topic: The first step in writing a thesis is to choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. You should also consider the scope of the topic and the availability of resources for research.

- Develop a Research Question: Once you have chosen a topic, you need to develop a research question that you will answer in your thesis. The research question should be specific, clear, and feasible.

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before you start your research, you need to conduct a literature review to identify the existing knowledge and gaps in the field. This will help you refine your research question and develop a research methodology.

- Develop a Research Methodology: Once you have refined your research question, you need to develop a research methodology that includes the research design, data collection methods, and data analysis procedures.

- Collect and Analyze Data: After developing your research methodology, you need to collect and analyze data. This may involve conducting surveys, interviews, experiments, or analyzing existing data.

- Write the Thesis: Once you have analyzed the data, you need to write the thesis. The thesis should follow a specific structure that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, and references.

- Edit and Proofread: After completing the thesis, you need to edit and proofread it carefully. You should also have someone else review it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors.

- Submit the Thesis: Finally, you need to submit the thesis to your academic advisor or committee for review and evaluation.

Example of Thesis

Example of Thesis template for Students:

Title of Thesis

Table of Contents:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Chapter 4: Results

Chapter 5: Discussion

Chapter 6: Conclusion

References:

Appendices:

Note: That’s just a basic template, but it should give you an idea of the structure and content that a typical thesis might include. Be sure to consult with your department or supervisor for any specific formatting requirements they may have. Good luck with your thesis!

Application of Thesis

Thesis is an important academic document that serves several purposes. Here are some of the applications of thesis:

- Academic Requirement: A thesis is a requirement for many academic programs, especially at the graduate level. It is an essential component of the evaluation process and demonstrates the student’s ability to conduct original research and contribute to the knowledge in their field.

- Career Advancement: A thesis can also help in career advancement. Employers often value candidates who have completed a thesis as it demonstrates their research skills, critical thinking abilities, and their dedication to their field of study.

- Publication : A thesis can serve as a basis for future publications in academic journals, books, or conference proceedings. It provides the researcher with an opportunity to present their research to a wider audience and contribute to the body of knowledge in their field.

- Personal Development: Writing a thesis is a challenging task that requires time, dedication, and perseverance. It provides the student with an opportunity to develop critical thinking, research, and writing skills that are essential for their personal and professional development.

- Impact on Society: The findings of a thesis can have an impact on society by addressing important issues, providing insights into complex problems, and contributing to the development of policies and practices.

Purpose of Thesis

The purpose of a thesis is to present original research findings in a clear and organized manner. It is a formal document that demonstrates a student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. The primary purposes of a thesis are:

- To Contribute to Knowledge: The main purpose of a thesis is to contribute to the knowledge in a particular field of study. By conducting original research and presenting their findings, the student adds new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- To Demonstrate Research Skills: A thesis is an opportunity for the student to demonstrate their research skills. This includes the ability to formulate a research question, design a research methodology, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- To Develop Critical Thinking: Writing a thesis requires critical thinking and analysis. The student must evaluate existing literature and identify gaps in the field, as well as develop and defend their own ideas.

- To Provide Evidence of Competence : A thesis provides evidence of the student’s competence in their field of study. It demonstrates their ability to apply theoretical concepts to real-world problems, and their ability to communicate their ideas effectively.

- To Facilitate Career Advancement : Completing a thesis can help the student advance their career by demonstrating their research skills and dedication to their field of study. It can also provide a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

When to Write Thesis

The timing for writing a thesis depends on the specific requirements of the academic program or institution. In most cases, the opportunity to write a thesis is typically offered at the graduate level, but there may be exceptions.

Generally, students should plan to write their thesis during the final year of their graduate program. This allows sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis. It is important to start planning the thesis early and to identify a research topic and research advisor as soon as possible.

In some cases, students may be able to write a thesis as part of an undergraduate program or as an independent research project outside of an academic program. In such cases, it is important to consult with faculty advisors or mentors to ensure that the research is appropriately designed and executed.

It is important to note that the process of writing a thesis can be time-consuming and requires a significant amount of effort and dedication. It is important to plan accordingly and to allocate sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis.

Characteristics of Thesis

The characteristics of a thesis vary depending on the specific academic program or institution. However, some general characteristics of a thesis include:

- Originality : A thesis should present original research findings or insights. It should demonstrate the student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study.

- Clarity : A thesis should be clear and concise. It should present the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions in a logical and organized manner. It should also be well-written, with proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Research-Based: A thesis should be based on rigorous research, which involves collecting and analyzing data from various sources. The research should be well-designed, with appropriate research methods and techniques.

- Evidence-Based : A thesis should be based on evidence, which means that all claims made in the thesis should be supported by data or literature. The evidence should be properly cited using appropriate citation styles.

- Critical Thinking: A thesis should demonstrate the student’s ability to critically analyze and evaluate information. It should present the student’s own ideas and arguments, and engage with existing literature in the field.

- Academic Style : A thesis should adhere to the conventions of academic writing. It should be well-structured, with clear headings and subheadings, and should use appropriate academic language.

Advantages of Thesis

There are several advantages to writing a thesis, including:

- Development of Research Skills: Writing a thesis requires extensive research and analytical skills. It helps to develop the student’s research skills, including the ability to formulate research questions, design and execute research methodologies, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Contribution to Knowledge: Writing a thesis provides an opportunity for the student to contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. By conducting original research, they can add new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- Preparation for Future Research: Completing a thesis prepares the student for future research projects. It provides them with the necessary skills to design and execute research methodologies, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Career Advancement: Writing a thesis can help to advance the student’s career. It demonstrates their research skills and dedication to their field of study, and provides a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

- Personal Growth: Completing a thesis can be a challenging and rewarding experience. It requires dedication, hard work, and perseverance. It can help the student to develop self-confidence, independence, and a sense of accomplishment.

Limitations of Thesis

There are also some limitations to writing a thesis, including:

- Time and Resources: Writing a thesis requires a significant amount of time and resources. It can be a time-consuming and expensive process, as it may involve conducting original research, analyzing data, and producing a lengthy document.

- Narrow Focus: A thesis is typically focused on a specific research question or topic, which may limit the student’s exposure to other areas within their field of study.

- Limited Audience: A thesis is usually only read by a small number of people, such as the student’s thesis advisor and committee members. This limits the potential impact of the research findings.

- Lack of Real-World Application : Some thesis topics may be highly theoretical or academic in nature, which may limit their practical application in the real world.

- Pressure and Stress : Writing a thesis can be a stressful and pressure-filled experience, as it may involve meeting strict deadlines, conducting original research, and producing a high-quality document.

- Potential for Isolation: Writing a thesis can be a solitary experience, as the student may spend a significant amount of time working independently on their research and writing.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and...

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing...

Thesis Outline – Example, Template and Writing...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Figures in Research Paper – Examples and Guide

Hoortash Institute

Consultation writing, accepting and publishing articles

How to Write Chapter Two of a Thesis

In “ how to write chapter one; the introduction of thesis ” post, the way of writing the Introduction and its components were discussed.

In chapter 2 of a thesis or dissertation – a literature review or a review of the literature – generally, you need to write a background on the subject and make the conclusion that there is a gap in previous studies and you are going to fill it in your research.

In addition to the gap, the research questions and hypotheses as well as the theories that support your study should be discussed. You have to cover the purpose of your study, too.

How to start a literature review chapter?

This chapter is a component of the whole thesis, so it needs to be related to the previous and next chapters.

Start with stating the most important theories supporting your study. You may write them in Chronological order. Use the theories to emphasize the gap.

How to write subtitles of chapter two?

Your writing in chapter two and other chapters need some headings to organize your writing which are to be H3.

You can organize your thesis’s literature review based on each of these two factors:

Chronological order

It is your choice. You can organize your writing in chronological order, meaning, the timeline in which the theories were proposed. You may also choose to arrange it based on different subjects or variables.

Subjective arrangement

In this kind of arrangement, subtitles are chosen based on different subjects related to the title of your thesis. The content of each will be the theories and discussions on that specific subject.

In this case, the theories discussing in headings can be stated chronologically too.

Tips on writing the literature review chapter

Criticize the theories.

A literature review is not just a collection of previous studies or writing a brief history of them. You need to critic the theories and states made by other researchers. You can also use them in a way that shows the gap.

Support the gap

In conclusion chapter (chapter 5), some researchers propose some topics as further researches needed. Look for the gap of your study in this part and if there is one do not forget to mention it.

Emphasize the importance of the study

Everything you write in chapter two of the thesis (dissertation), should emphasize the existence of the gap as well as the importance of your study. Try to raise the research questions in the readers’ minds so that your research questions become theirs.

Write about everything

Do not forget to write on every component of your research especially the variables. Read the papers which are related to your thesis and write other researchers ideas about them. Then write your own idea (you can criticize them as it was said).

When is writing the literature review chapter done?

It is done when you have written on every topic which is discussed in your thesis. Do not leave a question in the readers’ minds.

While you are searching of some topics, it is possible that some new ideas and subtopics related to your dissertation title come up. In these cases, start a new search, read the related papers, and write about them in chapter two of your thesis too.

You Might Also Like

1 thought on “ How to Write Chapter Two of a Thesis ”

Asalamu ‘alaykum wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuh this section of yours is very informative , Could I just ask if you have a research anything about niqabs in islam? if there are charts and statistics it is highly appreciated jazzakallahu khairan

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Published on June 7, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical early steps in your writing process . It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding the specifics of your dissertation topic and showcasing its relevance to your field.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation , such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

In the final product, you can also provide a chapter outline for your readers. This is a short paragraph at the end of your introduction to inform readers about the organizational structure of your thesis or dissertation. This chapter outline is also known as a reading guide or summary outline.

Table of contents

How to outline your thesis or dissertation, dissertation and thesis outline templates, chapter outline example, sample sentences for your chapter outline, sample verbs for variation in your chapter outline, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis and dissertation outlines.

While there are some inter-institutional differences, many outlines proceed in a fairly similar fashion.

- Working Title

- “Elevator pitch” of your work (often written last).

- Introduce your area of study, sharing details about your research question, problem statement , and hypotheses . Situate your research within an existing paradigm or conceptual or theoretical framework .

- Subdivide as you see fit into main topics and sub-topics.

- Describe your research methods (e.g., your scope , population , and data collection ).

- Present your research findings and share about your data analysis methods.

- Answer the research question in a concise way.

- Interpret your findings, discuss potential limitations of your own research and speculate about future implications or related opportunities.

For a more detailed overview of chapters and other elements, be sure to check out our article on the structure of a dissertation or download our template .

To help you get started, we’ve created a full thesis or dissertation template in Word or Google Docs format. It’s easy adapt it to your own requirements.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

It can be easy to fall into a pattern of overusing the same words or sentence constructions, which can make your work monotonous and repetitive for your readers. Consider utilizing some of the alternative constructions presented below.

Example 1: Passive construction

The passive voice is a common choice for outlines and overviews because the context makes it clear who is carrying out the action (e.g., you are conducting the research ). However, overuse of the passive voice can make your text vague and imprecise.

Example 2: IS-AV construction

You can also present your information using the “IS-AV” (inanimate subject with an active verb ) construction.

A chapter is an inanimate object, so it is not capable of taking an action itself (e.g., presenting or discussing). However, the meaning of the sentence is still easily understandable, so the IS-AV construction can be a good way to add variety to your text.

Example 3: The “I” construction

Another option is to use the “I” construction, which is often recommended by style manuals (e.g., APA Style and Chicago style ). However, depending on your field of study, this construction is not always considered professional or academic. Ask your supervisor if you’re not sure.

Example 4: Mix-and-match

To truly make the most of these options, consider mixing and matching the passive voice , IS-AV construction , and “I” construction .This can help the flow of your argument and improve the readability of your text.

As you draft the chapter outline, you may also find yourself frequently repeating the same words, such as “discuss,” “present,” “prove,” or “show.” Consider branching out to add richness and nuance to your writing. Here are some examples of synonyms you can use.

| Address | Describe | Imply | Refute |

| Argue | Determine | Indicate | Report |

| Claim | Emphasize | Mention | Reveal |

| Clarify | Examine | Point out | Speculate |

| Compare | Explain | Posit | Summarize |

| Concern | Formulate | Present | Target |

| Counter | Focus on | Propose | Treat |

| Define | Give | Provide insight into | Underpin |

| Demonstrate | Highlight | Recommend | Use |

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

The title page of your thesis or dissertation goes first, before all other content or lists that you may choose to include.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review , research methods , avenues for future research, etc.)

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, November 21). Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/dissertation-thesis-outline/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation table of contents in word | instructions & examples, figure and table lists | word instructions, template & examples, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Advertise with us

- Thursday, August 29, 2024

Most Widely Read Newspaper

PunchNG Menu:

- Special Features

- Sex & Relationship

ID) . '?utm_source=news-flash&utm_medium=web"> Download Punch Lite App

Project Chapter Two: Literature Review and Steps to Writing Empirical Review

Kindly share this story:

- Conceptual review

- Theoretical review,

- Empirical review or review of empirical works of literature/studies, and lastly

- Conclusion or Summary of the literature reviewed.

- Decide on a topic

- Highlight the studies/literature that you will review in the empirical review

- Analyze the works of literature separately.

- Summarize the literature in table or concept map format.

- Synthesize the literature and then proceed to write your empirical review.

All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from PUNCH.

Contact: [email protected]

Stay informed and ahead of the curve! Follow The Punch Newspaper on WhatsApp for real-time updates, breaking news, and exclusive content. Don't miss a headline – join now!

VERIFIED NEWS: As a Nigerian, you can earn US Dollars with REGULAR domains, buy for as low as $24, resell for up to $1000. Earn $15,000 monthly. Click here to start.

Latest News

Zinwe's eviction, age drama between topher and anita, chelsea academy player anjorin signs for empoli, fg restates support for local industry development, fg, ifad empower 121,000 smallholder farmers in nine states, enugu gov sets up minimum wage implementation committee.

BREAKING: Osigwe sworn in as 32nd NBA president

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, conse adipiscing elit.

Research Methods

Chapter 2 introduction.

Maybe you have already gained some experience in doing research, for example in your bachelor studies, or as part of your work.

The challenge in conducting academic research at masters level, is that it is multi-faceted.

The types of activities are:

- Finding and reviewing literature on your research topic;

- Designing a research project that will answer your research questions;

- Collecting relevant data from one or more sources;

- Analyzing the data, statistically or otherwise, and

- Writing up and presenting your findings.

Some researchers are strong on some parts but weak on others.

We do not require perfection. But we do require high quality.

Going through all stages of the research project, with the guidance of your supervisor, is a learning process.

The journey is hard at times, but in the end your thesis is considered an academic publication, and we want you to be proud of what you have achieved!

Probably the biggest challenge is, where to begin?

- What will be your topic?

- And once you have selected a topic, what are the questions that you want to answer, and how?

In the first chapter of the book, you will find several views on the nature and scope of business research.

Since a study in business administration derives its relevance from its application to real-life situations, an MBA typically falls in the grey area between applied research and basic research.

The focus of applied research is on finding solutions to problems, and on improving (y)our understanding of existing theories of management.

Applied research that makes use of existing theories, often leads to amendments or refinements of these theories. That is, the applied research feeds back to basic research.

In the early stages of your research, you will feel like you are running around in circles.

You start with an idea for a research topic. Then, after reading literature on the topic, you will revise or refine your idea. And start reading again with a clearer focus ...

A thesis research/project typically consists of two main stages.

The first stage is the research proposal .

Once the research proposal has been approved, you can start with the data collection, analysis and write-up (including conclusions and recommendations).

Stage 1, the research proposal consists of he first three chapters of the commonly used five-chapter structure :

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- An introduction to the topic.

- The research questions that you want to answer (and/or hypotheses that you want to test).

- A note on why the research is of academic and/or professional relevance.

- Chapter 2: Literature

- A review of relevant literature on the topic.

- Chapter 3: Methodology

The methodology is at the core of your research. Here, you define how you are going to do the research. What data will be collected, and how?

Your data should allow you to answer your research questions. In the research proposal, you will also provide answers to the questions when and how much . Is it feasible to conduct the research within the given time-frame (say, 3-6 months for a typical master thesis)? And do you have the resources to collect and analyze the data?

In stage 2 you collect and analyze the data, and write the conclusions.

- Chapter 4: Data Analysis and Findings

- Chapter 5: Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

This video gives a nice overview of the elements of writing a thesis.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to structure a thesis

A typical thesis structure

1. abstract, 2. introduction, 3. literature review, 6. discussion, 7. conclusion, 8. reference list, frequently asked questions about structuring a thesis, related articles.

Starting a thesis can be daunting. There are so many questions in the beginning:

- How do you actually start your thesis?

- How do you structure it?

- What information should the individual chapters contain?

Each educational program has different demands on your thesis structure, which is why asking directly for the requirements of your program should be a first step. However, there is not much flexibility when it comes to structuring your thesis.

Abstract : a brief overview of your entire thesis.

Literature review : an evaluation of previous research on your topic that includes a discussion of gaps in the research and how your work may fill them.

Methods : outlines the methodology that you are using in your research.

Thesis : a large paper, or multi-chapter work, based on a topic relating to your field of study.

The abstract is the overview of your thesis and generally very short. This section should highlight the main contents of your thesis “at a glance” so that someone who is curious about your work can get the gist quickly. Take a look at our guide on how to write an abstract for more info.

Tip: Consider writing your abstract last, after you’ve written everything else.

The introduction to your thesis gives an overview of its basics or main points. It should answer the following questions:

- Why is the topic being studied?

- How is the topic being studied?

- What is being studied?

In answering the first question, you should know what your personal interest in this topic is and why it is relevant. Why does it matter?

To answer the "how", you should briefly explain how you are going to reach your research goal. Some prefer to answer that question in the methods chapter, but you can give a quick overview here.

And finally, you should explain "what" you are studying. You can also give background information here.

You should rewrite the introduction one last time when the writing is done to make sure it connects with your conclusion. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our thesis introduction guide .

A literature review is often part of the introduction, but it can be a separate section. It is an evaluation of previous research on the topic showing that there are gaps that your research will attempt to fill. A few tips for your literature review:

- Use a wide array of sources

- Show both sides of the coin

- Make sure to cover the classics in your field

- Present everything in a clear and structured manner

For more insights on lit reviews, take a look at our guide on how to write a literature review .

The methodology chapter outlines which methods you choose to gather data, how the data is analyzed and justifies why you chose that methodology . It shows how your choice of design and research methods is suited to answering your research question.

Make sure to also explain what the pitfalls of your approach are and how you have tried to mitigate them. Discussing where your study might come up short can give you more credibility, since it shows the reader that you are aware of its limitations.

Tip: Use graphs and tables, where appropriate, to visualize your results.

The results chapter outlines what you found out in relation to your research questions or hypotheses. It generally contains the facts of your research and does not include a lot of analysis, because that happens mostly in the discussion chapter.

Clearly visualize your results, using tables and graphs, especially when summarizing, and be consistent in your way of reporting. This means sticking to one format to help the reader evaluate and compare the data.

The discussion chapter includes your own analysis and interpretation of the data you gathered , comments on your results and explains what they mean. This is your opportunity to show that you have understood your findings and their significance.

Point out the limitations of your study, provide explanations for unexpected results, and note any questions that remain unanswered.

This is probably your most important chapter. This is where you highlight that your research objectives have been achieved. You can also reiterate any limitations to your study and make suggestions for future research.

Remember to check if you have really answered all your research questions and hypotheses in this chapter. Your thesis should be tied up nicely in the conclusion and show clearly what you did, what results you got, and what you learned. Discover how to write a good conclusion in our thesis conclusion guide .

At the end of your thesis, you’ll have to compile a list of references for everything you’ve cited above. Ideally, you should keep track of everything from the beginning. Otherwise, this could be a mammoth and pretty laborious task to do.

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to format and organize your citations. Paperpile allows you to organize and save your citations for later use and cite them in thousands of citation styles directly in Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or LaTeX:

🔲 Introduction

🔲 Literature review

🔲 Discussion

🔲 Conclusion

🔲 Reference list

The basic elements of a thesis are: Abstract, Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, Conclusion, and Reference List.

It's recommended to start a thesis by writing the literature review first. This way you learn more about the sources, before jumping to the discussion or any other element.

It's recommended to write the abstract of a thesis last, once everything else is done. This way you will be able to provide a complete overview of your work.

Usually, the discussion is the longest part of a thesis. In this part you are supposed to point out the limitations of your study, provide explanations for unexpected results, and note any questions that remain unanswered.

The order of the basic elements of a thesis are: 1. Abstract, 2. Introduction, 3. Literature Review, 4. Methods, 5. Results, 6. Discussion, 7. Conclusion, and 8. Reference List.

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

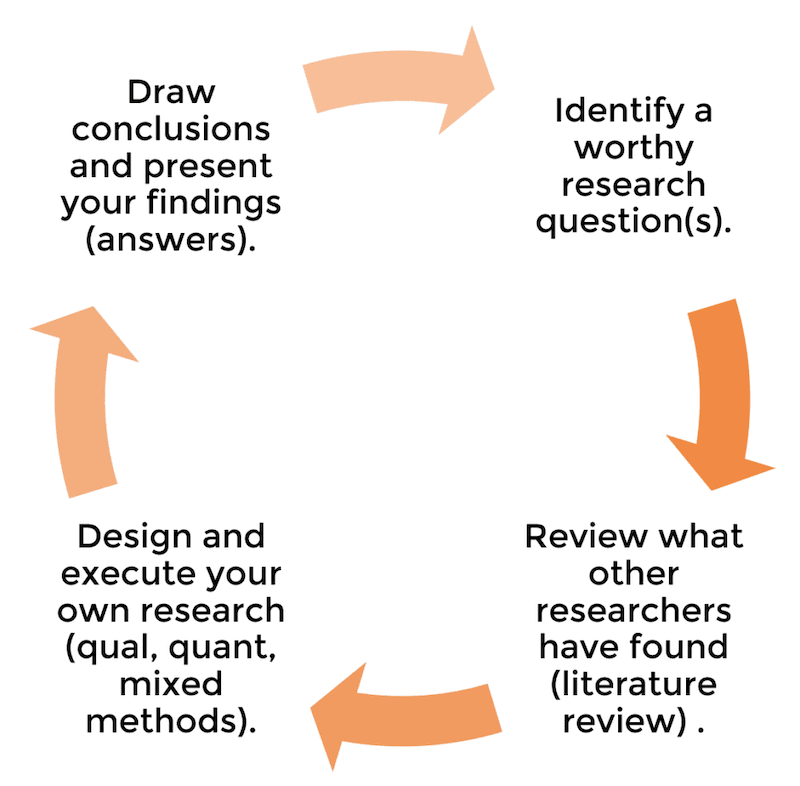

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.