- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: https://sites.psu.edu/pedagogicalpractices/case-studies/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the National Science Teaching Association.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.

- A case study seeks to identify the best possible solution to a research problem; case analysis can have an indeterminate set of solutions or outcomes . Your role in studying a case is to discover the most logical, evidence-based ways to address a research problem. A case analysis assignment rarely has a single correct answer because one of the goals is to force students to confront the real life dynamics of uncertainly, ambiguity, and missing or conflicting information within professional practice. Under these conditions, a perfect outcome or solution almost never exists.

- Case study is unbounded and relies on gathering external information; case analysis is a self-contained subject of analysis . The scope of a case study chosen as a method of research is bounded. However, the researcher is free to gather whatever information and data is necessary to investigate its relevance to understanding the research problem. For a case analysis assignment, your professor will often ask you to examine solutions or recommended courses of action based solely on facts and information from the case.

- Case study can be a person, place, object, issue, event, condition, or phenomenon; a case analysis is a carefully constructed synopsis of events, situations, and behaviors . The research problem dictates the type of case being studied and, therefore, the design can encompass almost anything tangible as long as it fulfills the objective of generating new knowledge and understanding. A case analysis is in the form of a narrative containing descriptions of facts, situations, processes, rules, and behaviors within a particular setting and under a specific set of circumstances.

- Case study can represent an open-ended subject of inquiry; a case analysis is a narrative about something that has happened in the past . A case study is not restricted by time and can encompass an event or issue with no temporal limit or end. For example, the current war in Ukraine can be used as a case study of how medical personnel help civilians during a large military conflict, even though circumstances around this event are still evolving. A case analysis can be used to elicit critical thinking about current or future situations in practice, but the case itself is a narrative about something finite and that has taken place in the past.

- Multiple case studies can be used in a research study; case analysis involves examining a single scenario . Case study research can use two or more cases to examine a problem, often for the purpose of conducting a comparative investigation intended to discover hidden relationships, document emerging trends, or determine variations among different examples. A case analysis assignment typically describes a stand-alone, self-contained situation and any comparisons among cases are conducted during in-class discussions and/or student presentations.

The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017; Crowe, Sarah et al. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (2011): doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Works

- Next: Writing a Case Study >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Assessment by Case Studies and Scenarios

Case studies depict real-life situations in which problems need to be solved. Scenario-based teaching may be similar to case studies, or may be oriented toward developing communication or teamwork skills. Both case studies and scenarios are commonly used methods of problem-based learning. Typically, using these methods, teachers aim to develop student reasoning, problem-solving and decision-making skills. Case studies differ from role plays in that in the former, learning takes place largely through discussion and analysis, whereas in the latter, students assume a character or role and "act out" what that character would do in the scenario (The Teaching Gateway page Assessing with Role Plays and Simulations contains more information on using role plays for assessments.) Like role plays and simulations, case studies and scenarios aim for authenticity: allowing students to get a sense of the situations they might face in the real world upon graduation. Students can see how their learning and skills can be applied in a real-world situation, without the pressure of being actually involved in that situation with the associated constraints on research, discussion and reflection time.

Case studies and scenarios are particularly useful when they present situations are complex and solutions are uncertain. Ideally, their complexity requires group members to draw from and share their experiences, work together, and learn by doing to understand and help solve the case-study problem.

You can present a single case to several groups in a class and require each group to offer its solutions, or you can give a different case to each group or individual.

Case studies' effectiveness comes from their abiliity to:

- engage students in research and reflective discussion

- encourage clinical and professional reasoning in a safe environment

- encourage higher-order thinking

- facilitate creative problem solving and the application of different problem-solving theories without risk to third parties or projects

- allow students to develop realistic solutions to complex problems

- develop students' ability to identify and distinguish between critical and extraneous factors

- enable students to apply previously acquired skills

- allow students to learn from one another

- provide an effective simulated learning environment

- encourage practical reasoning

- allow you to assess individuals or teams.

You can use case studies to bridge the gap between teacher-centred lectures and pure problem-based learning. They leave room for you to guide students directly, while the scenarios themselves suggest how students should operate, and provide parameters for their work.

Although some students have reported greater satisfaction with simulations as learning tools than with case studies (Maamari & El-Nakla, 2023), case studies generally require less up-front preparation time, and can be less intimidating for students.

To make case studies an effective form of assessment, instructors and tutors need to be familiar with their use in both teaching and assessment. This applies whether teachers are developing the case studies for their courses themselves or using those developed by others.

Case studies reach their highest effectiveness as a teaching and assessment tool when they are authentic; ensuring that case studies accurately reflect the circumstances in which a student will eventually be practising professionally can require a considerable amount of research, as well as the potential involvement of industry professionals.

Students may need scaffolding as they learn how to problem-solve in the context of case studies; using case studies as low-stakes, formative assessments can prepare them for summative assessment by case study at the end of the course.

Learning outcomes, course outlines, and marking rubrics need to be entirely clear about how case studies will be used in the course and how students will be expected to demonstrate their learning through thee way they analyse and problem-solve in the context of case studies.

Assessment preparation

Typically, the product assessed after case study or scenario work is a verbal presentation or a written submission. Decide who will take part in the assessment: the tutor, an industry specialist, a panel, peer groups or students themselves by self-evaluation? Choose whether to give a class or group mark or to assess individual performance; and whether to assess the product yourself or have it assessed by peers.

Assessment strategies

You can assess students’ interaction with other members of a group by asking open-ended questions, and setting tasks that require teamwork and sharing resources.

Assess the process of analysis

Case studies allow you to assess a student’s demonstration of deeper understanding and cognitive skills as they address the case. These skills include, for example:

- identification of a problem

- hypotheses generation

- construction of an enquiry plan

- interpretation of findings

- investigation of results collected for evidence to refine a hypothesis and construction of a management plan.

During the problem-solving process, you can also observe and evaluate:

- quality of research

- structural issues in written material

- organisation of arguments

- feasibility of solutions presented

- intra-group dynamics

- evidence of consideration of all case factors

- multiple resolutions of the same scenario issue.

Use a variety of questions in case analysis

The Questioning page discusses in detail various ways to use questions in teaching . If your students are using the Harvard Business School case study method for their analysis, use a range of question types to enable the class to move through the stages of analysis:

- clarification/information seeking ( What? )

- analysis/diagnosis ( Why? )

- conclusion/recommendation ( What now? )

- implementation ( How? ) and

- application/reflection ( So what? What does it mean to you?)

Use technology

Learning-management systems such as Moodle can help you track contributions to case discussions . You can assess students' interactions with other members of a group by viewing their responses to open-ended questions or observing their teamwork and sharing of resources as part of the discussion. You can incorporate the use of various tools in these systems, or others such as Survey Monkey, into students' assessment of their peers, or of their group members' contribution to exploring and presenting case studies. You can also set this peer assessment up so that it takes place anonymously.

Assessing by Case Studies: UNSW examples

These videos show examples of how UNSW faculty have implemented case studies in their own courses.

- Boston University. Using Case Studies to Teach

- Columbia University. Case Method Teaching and Learning

- Science Education Resource Center, Carleton College. Starting Point: What is Investigative Case-Based Learning?

Maamari, B. E., & El-Nakla, D. (2023). From case studies to experiential learning. Is simulation an effective tool for student assessment? Arab Economic and Business Journal, 15(1), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.38039/2214-4625.1023

Merret, C. (2020). Using case studies and build projects as authentic assessments in cornerstone courses. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education , 50 (1), 20-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306419020913286

Porzecanski, A. L., Bravo, A., Groom, M. J., Dávalos, L. M., Bynum, N., Abraham, B. J., Cigliano, J. A., Griffiths, C., Stokes, D. L., Cawthorn, M., Fernandez, D. S., Freeman, L., Leslie, T., Theodose, T., Vogler, D., & Sterling, E. J. (2021). Using case studies to improve the critical thinking skills of undergraduate conservation biology students. Case Studies in the Environment , 5 (1), 1536396. https://doi.org/10.1525/cse.2021.1536396

- Teaching for learning

- Assessment Toolkit

- Digital Assessment at UNSW

- Designing Assessment

- Selecting Assessment Methods

- Selecting Assessment Technologies

- Oral Assessment

- Capstone Project

- Case Studies & Scenarios

- Oral Presentations

- Role Play & Simulation

- Competency Assessment and Grading

- Grading & Giving Feedback

- Reviewing Assessment Quality

- Spotlight on Assessment

- Assessment Development Framework

- Teaching Settings

Events & news

- International

- Business & Industry

- MyUNB Intranet

- Activate your IT Services

- Give to UNB

- Centre for Enhanced Teaching & Learning

- Teaching & Learning Services

- Teaching Tips

- Instructional Methods

- Creating Effective Scenarios, Case Studies and Role Plays

Creating effective scenarios, case studies and role plays

Printable Version (PDF)

Scenarios, case studies and role plays are examples of active and collaborative teaching techniques that research confirms are effective for the deep learning needed for students to be able to remember and apply concepts once they have finished your course. See Research Findings on University Teaching Methods .

Typically you would use case studies, scenarios and role plays for higher-level learning outcomes that require application, synthesis, and evaluation (see Writing Outcomes or Learning Objectives ; scroll down to the table).

The point is to increase student interest and involvement, and have them practice application by making choices and receive feedback on them, and refine their understanding of concepts and practice in your discipline.

These types of activities provide the following research-based benefits: (Shaw, 3-5)

- They provide concrete examples of abstract concepts, facilitate the development through practice of analytical skills, procedural experience, and decision making skills through application of course concepts in real life situations. This can result in deep learning and the appreciation of differing perspectives.

- They can result in changed perspectives, increased empathy for others, greater insights into challenges faced by others, and increased civic engagement.

- They tend to increase student motivation and interest, as evidenced by increased rates of attendance, completion of assigned readings, and time spent on course work outside of class time.

- Studies show greater/longer retention of learned materials.

- The result is often better teacher/student relations and a more relaxed environment in which the natural exchange of ideas can take place. Students come to see the instructor in a more positive light.

- They often result in better understanding of complexity of situations. They provide a good forum for a large volume of orderly written analysis and discussion.

There are benefits for instructors as well, such as keeping things fresh and interesting in courses they teach repeatedly; providing good feedback on what students are getting and not getting; and helping in standing and promotion in institutions that value teaching and learning.

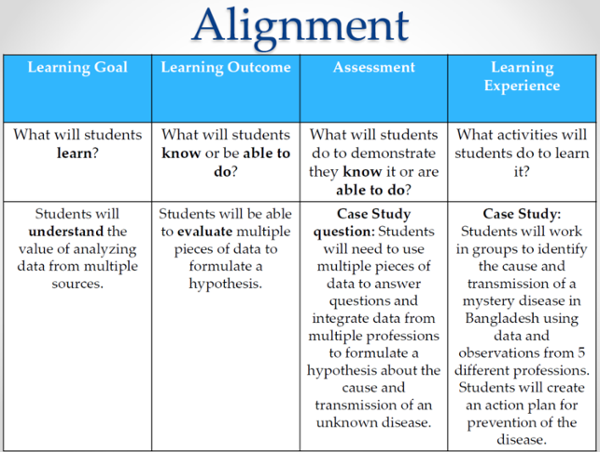

Outcomes and learning activity alignment

The learning activity should have a clear, specific skills and/or knowledge development purpose that is evident to both instructor and students. Students benefit from knowing the purpose of the exercise, learning outcomes it strives to achieve, and evaluation methods. The example shown in the table below is for a case study, but the focus on demonstration of what students will know and can do, and the alignment with appropriate learning activities to achieve those abilities applies to other learning activities.

(Smith, 18)

What’s the difference?

Scenarios are typically short and used to illustrate or apply one main concept. The point is to reinforce concepts and skills as they are taught by providing opportunity to apply them. Scenarios can also be more elaborate, with decision points and further scenario elaboration (multiple storylines), depending on responses. CETL has experience developing scenarios with multiple decision points and branching storylines with UNB faculty using PowerPoint and online educational software.

Case studies

Case studies are typically used to apply several problem-solving concepts and skills to a detailed situation with lots of supporting documentation and data. A case study is usually more complex and detailed than a scenario. It often involves a real-life, well documented situation and the students’ solutions are compared to what was done in the actual case. It generally includes dialogue, creates identification or empathy with the main characters, depending on the discipline. They are best if the situations are recent, relevant to students, have a problem or dilemma to solve, and involve principles that apply broadly.

Role plays can be short like scenarios or longer and more complex, like case studies, but without a lot of the documentation. The idea is to enable students to experience what it may be like to see a problem or issue from many different perspectives as they assume a role they may not typically take, and see others do the same.

Foundational considerations

Typically, scenarios, case studies and role plays should focus on real problems, appropriate to the discipline and course level.

They can be “well-structured” or “ill-structured”:

- Well-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can be simple or complex or anything in-between, but they have an optimal solution and only relevant information is given, and it is usually labelled or otherwise easily identified.

- Ill-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can also be simple or complex, although they tend to be complex. They have relevant and irrelevant information in them, and part of the student’s job is to decide what is relevant, how it is relevant, and to devise an evidence-based solution to the problem that is appropriate to the context and that can be defended by argumentation that draws upon the student’s knowledge of concepts in the discipline.

Well-structured problems would be used to demonstrate understanding and application. Higher learning levels of analysis, synthesis and evaluation are better demonstrated by ill-structured problems.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be authentic or realistic :

- Authentic scenarios are actual events that occurred, usually with personal details altered to maintain anonymity. Since the events actually happened, we know that solutions are grounded in reality, not a fictionalized or idealized or simplified situation. This makes them “low transference” in that, since we are dealing with the real world (although in a low-stakes, training situation, often with much more time to resolve the situation than in real life, and just the one thing to work on at a time), not much after-training adjustment to the real world is necessary.

- By contrast, realistic scenarios are often hypothetical situations that may combine aspects of several real-world events, but are artificial in that they are fictionalized and often contain ideal or simplified elements that exist differently in the real world, and some complications are missing. This often means they are easier to solve than real-life issues, and thus are “high transference” in that some after-training adjustment is necessary to deal with the vagaries and complexities of the real world.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be high or low fidelity :

High vs. low fidelity: Fidelity has to do with how much a scenario, case study or role play is like its corresponding real world situation. Simplified, well-structured scenarios or problems are most appropriate for beginners. These are low-fidelity, lacking a lot of the detail that must be struggled with in actual practice. As students gain experience and deeper knowledge, the level of complexity and correspondence to real-world situations can be increased until they can solve high fidelity, ill-structured problems and scenarios.

Further details for each

Scenarios can be used in a very wide range of learning and assessment activities. Use in class exercises, seminars, as a content presentation method, exam (e.g., tell students the exam will have four case studies and they have to choose two—this encourages deep studying). Scenarios help instructors reflect on what they are trying to achieve, and modify teaching practice.

For detailed working examples of all types, see pages 7 – 25 of the Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS) pdf .

The contents of case studies should: (Norton, 6)

- Connect with students’ prior knowledge and help build on it.

- Be presented in a real world context that could plausibly be something they would do in the discipline as a practitioner (e.g., be “authentic”).

- Provide some structure and direction but not too much, since self-directed learning is the goal. They should contain sufficient detail to make the issues clear, but with enough things left not detailed that students have to make assumptions before proceeding (or explore assumptions to determine which are the best to make). “Be ambiguous enough to force them to provide additional factors that influence their approach” (Norton, 6).

- Should have sufficient cues to encourage students to search for explanations but not so many that a lot of time is spent separating relevant and irrelevant cues. Also, too many storyline changes create unnecessary complexity that makes it unnecessarily difficult to deal with.

- Be interesting and engaging and relevant but focus on the mundane, not the bizarre or exceptional (we want to develop skills that will typically be of use in the discipline, not for exceptional circumstances only). Students will relate to case studies more if the depicted situation connects to personal experiences they’ve had.

- Help students fill in knowledge gaps.

Role plays generally have three types of participants: players, observers, and facilitator(s). They also have three phases, as indicated below:

Briefing phase: This stage provides the warm-up, explanations, and asks participants for input on role play scenario. The role play should be somewhat flexible and customizable to the audience. Good role descriptions are sufficiently detailed to let the average person assume the role but not so detailed that there are so many things to remember that it becomes cumbersome. After role assignments, let participants chat a bit about the scenarios and their roles and ask questions. In assigning roles, consider avoiding having visible minorities playing “bad guy” roles. Ensure everyone is comfortable in their role; encourage students to play it up and even overact their role in order to make the point.

Play phase: The facilitator makes seating arrangements (for players and observers), sets up props, arranges any tech support necessary, and does a short introduction. Players play roles, and the facilitator keeps things running smoothly by interjecting directions, descriptions, comments, and encouraging the participation of all roles until players keep things moving without intervention, then withdraws. The facilitator provides a conclusion if one does not arise naturally from the interaction.

Debriefing phase: Role players talk about their experience to the class, facilitated by the instructor or appointee who draws out the main points. All players should describe how they felt and receive feedback from students and the instructor. If the role play involved heated interaction, the debriefing must reconcile any harsh feelings that may otherwise persist due to the exercise.

Five Cs of role playing (AOM, 3)

Control: Role plays often take on a life of their own that moves them in directions other than those intended. Rehearse in your mind a few possible ways this could happen and prepare possible intervention strategies. Perhaps for the first role play you can play a minor role to give you and “in” to exert some control if needed. Once the class has done a few role plays, getting off track becomes less likely. Be sensitive to the possibility that students from different cultures may respond in unforeseen ways to role plays. Perhaps ask students from diverse backgrounds privately in advance for advice on such matters. Perhaps some of these students can assist you as co-moderators or observers.

Controversy: Explain to students that they need to prepare for situations that may provoke them or upset them, and they need to keep their cool and think. Reiterate the learning goals and explain that using this method is worth using because it draws in students more deeply and helps them to feel, not just think, which makes the learning more memorable and more likely to be accessible later. Set up a “safety code word” that students may use at any time to stop the role play and take a break.

Command of details: Students who are more deeply involved may have many more detailed and persistent questions which will require that you have a lot of additional detail about the situation and characters. They may also question the value of role plays as a teaching method, so be prepared with pithy explanations.

Can you help? Students may be concerned about how their acting will affect their grade, and want assistance in determining how to play their assigned character and need time to get into their role. Tell them they will not be marked on their acting. Say there is no single correct way to play a character. Prepare for slow starts, gaps in the action, and awkward moments. If someone really doesn’t want to take a role, let them participate by other means—as a recorder, moderator, technical support, observer, props…

Considered reflection: Reflection and discussion are the main ways of learning from role plays. Players should reflect on what they felt, perceived, and learned from the session. Review the key events of the role play and consider what people would do differently and why. Include reflections of observers. Facilitate the discussion, but don’t impose your opinions, and play a neutral, background role. Be prepared to start with some of your own feedback if discussion is slow to start.

An engineering role play adaptation

Boundary objects (e.g., storyboards) have been used in engineering and computer science design projects to facilitate collaboration between specialists from different disciplines (Diaz, 6-80). In one instance, role play was used in a collaborative design workshop as a way of making computer scientist or engineering students play project roles they are not accustomed to thinking about, such as project manager, designer, user design specialist, etc. (Diaz 6-81).

References:

Academy of Management. (Undated). Developing a Role playing Case Study as a Teaching Tool.

Diaz, L., Reunanen, M., & Salimi, A. (2009, August). Role Playing and Collaborative Scenario Design Development. Paper presented at the International Conference of Engineering Design, Stanford University, California.

Norton, L. (2004). Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS): A practical introduction to problem-based learning using vignettes for psychology lecturers . Liverpool Hope University College.

Shaw, C. M. (2010). Designing and Using Simulations and Role-Play Exercises in The International Studies Encyclopedia, eISBN: 9781444336597

Smith, A. R. & Evanstone, A. (Undated). Writing Effective Case Studies in the Sciences: Backward Design and Global Learning Outcomes. Institute for Biological Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Campus Maps

- Campus Security

- Careers at UNB

- Services at UNB

- Conference Services

- Online & Continuing Ed

Contact UNB

- © University of New Brunswick

- Accessibility

- Web feedback

How to... Write a teaching case study

- What is a teaching case study?

A discussion-based case study is an education tool to facilitate learning about, and analysis of, a real-world situation.

A case study provides a well-researched and compelling narrative about an individual, or a group of people, that needs to make a decision in an organisational setting.

The case study narrative includes relevant information about the situation, and gives multiple perspectives on the problem or decision that needs to be taken, but does not provide analysis, conclusions, or a solution.

On this page...

How does a case study work in education, top tips for writing a case study, what is the difference between teaching cases and research focused cases.

- Writing the case study

How to write a teaching note

- Final thoughts

The Emerald Cases Hub

Which publication would suit my case study.

Read about getting ready to publish and visit the Emerald Cases Hub for courses and guides on writing case studies and teaching notes.

Teaching cases expose students to real-world business dilemmas in different cultural contexts.

Students are expected to read the case study and prepare an argument about the most appropriate course of action or recommendation, which can be debated in a facilitated case study class session, or documented in a case study assignment or examination.

A case teaching note, containing recent and relevant theoretical and managerial frameworks, will be published alongside the teaching case, and can be used to demonstrate the links between course content and the case situation to support teaching of the case method.

Teaching case studies have a distinctive literary style: they are written in the third person, in the past tense, and establish an objectivity of core dilemmas in the case.

We have gathered some top tips for you to think about as your write your case study.

Collect information

Cases can be based on primary or secondary data; however, carrying out interviews with the protagonist and others in the organisation, where possible, often results in a better and more balanced case study.

Make sure that you have all the materials you will need before you start the writing process. This will speed up the actual process. Most case studies have a mixture of primary and secondary sources to help capture the spirit of the protagonist.

Structure the narrative

Tell the story in chronological order and in the past tense. Identify and establish the central protagonist and their dilemma in the first paragraph and summarise the dilemma again at the end of the case.

Develop the protagonist

Ensure the protagonist is a well-developed character and that students can identify with their motivations throughout the case.

Get permission

When you submit your case study and teaching note, you must include signed permission from the relevant protagonist or company featured in the case and for any material for which you don’t own the copyright.

Be clear on your teaching objective

The case method offers a variety of class participation methods, such as discussion, role-play, presentation, or examination. Decide which method best suits the case you want to write.

Identify case lead author

You might want to consider writing your case study in partnership with colleagues. However, if you are writing a case with other people you need to make sure that the case reads as one voice.

You do not have to share the work evenly. Instead, play to your individual strengths: one author might be better at data analysis, one a better writer. Agree and clarify the order of appearance of authors. This is very important since this cannot be changed after publication.

Write a thorough teaching note

A well-written case study needs an equally well-written teaching note to allow instructors to adopt the case without the need for additional research. The standard teaching note provides key materials such as learning objectives, sample questions and answers, and more. See 'What to include in your teaching note' to produce effective teaching note for your case.

Writing a teaching case requires a distinctive literary style; it should be written in the third person, in the past tense, and establish objectivity of the core dilemmas in the case.

To begin with, a case has to have a hook: an overriding issue that pulls various parts together, a managerial issue or decision that requires urgent attention.

The trick is to present the story so that the hook is not immediately apparent but ‘discovered’ by students putting the relevant pieces together. More importantly, the hook must be linked to a particular concept, theory, or methodology.

A teaching case reflects the ambiguity of the situation and need not have a single outcome, as the intent is to create a dialogue with students, encourage critical thinking and research, and evaluate recommendations.

Research cases are a methodology used to support research findings and add to the body of theoretical knowledge, and as such are more academically-focused and evidence-based.

Writing a case study

How to write & structure a case

- Write in the past tense

- Identify and establish an issue/problem which can be used to teach a concept or theory

The opening paragraph should make clear:

- Who the main protagonist is

- Who the key decision maker is

- What the nature of the problem or issue is

- When the case took place, including specific dates

- Why the issue or problem arose

The body of the case should:

- Tell the whole story – usually in a chronological order

- Typically contain general background on business environment, company background, and the details of the specific issue(s) faced by the company

- Tell more than one side of the story so that students can think of competing alternatives

The concluding paragraph should:

- Provide a short synthesis of the case to reiterate the main issues, or even to raise new questions

Before you start, choose where to publish your case study and familiarise yourself with the style and formatting requirements.

Get ready to publish

What to include in your teaching note

Case synopsis.

Provide a brief summary (approximately 150-200 words) describing the case setting and key issues. Include:

- Name of the organisation

- Time span of the case study

- Details of the protagonist

- The dilemma facing the protagonist

- Sub-field of academia the case is designed to teach (e.g., market segmentation in the telecommunications sector).

Target audience

Clearly identify the appropriate audience for the case (e.g., undergraduate, graduate, or both). Consider:

- Possible courses where the case can be used

- Level of difficulty

- Specific pre-requisites

- Discipline(s) for which the case is most relevant

If there are multiple target audiences, discuss different teaching strategies.

Top tip: remember that the deciding factor for most instructors looking to find a case for their classroom is relevancy. Working with a specific audience in mind and sharing guidance on case usage helps develop the applicability of your case.

Learning objectives

Set a minimum of one objective for a compact case study and three to four for a longer case. Your objectives should be specific and reflective of the courses you suggest your case be taught in. Make it clear what students can expect to learn from reading the case.

Top tip: Good learning objectives should cover not only basic understanding of the context and issues presented in the case, but also include a few more advanced goals such as analysis and evaluation of the case dilemma.

Research methods

Outline the types of data used to develop the case, how this data was gathered, and whether any names/details/etc. within the case have been disguised. Please note that you will need to obtain consent from the case protagonist/organisation if primary data has been used. Cases based on secondary data (i.e., any information that is publicly available) are not required to obtain consent.

Teaching plan and objectives

Provide a breakdown of the classroom discussion time into sections. Include a brief description of the opening and closing 10-15 minutes, as well as challenging case discussion questions with comprehensive sample answers.

Provide instructors a detailed breakdown of how you would teach the case in 90 minutes. Include:

- Brief description of the opening 10-15 minutes.

- Suggested class time, broken down by topics, assignment questions, and activities.

- Brief description of the closing 10-15 minutes. Reinforce the learning objectives and reveal what actually happened, if applicable

Assignment questions and answers

Include a set of challenging assignment questions that align with the teaching objectives and relate to the dilemma being faced in the case.

Successful cases will provide:

- Three to five questions aligned to the learning objectives.

- A combination of closed, open-ended, and even controversial questions to create discussion.

- Questions that prompt students to consider a dilemma from all angles.

Successful sample answers should:

- Provide an example of an outstanding (A+) response to each question. To illustrate the full range of potential answers, good teaching notes often go on to provide examples of marginal and even incorrect responses as well.

- Draw from recent literature, theory, or research findings to analyse the case study.

- Reflect the reality that a case may not necessarily have a single correct answer by highlighting a diversity of opinions and approaches.

Supporting material

Supporting materials can include any additional information or resources that supplement the experience of using your case. Examples of these materials include such as worksheets, videos, reading lists, reference materials, etc. If you are including classroom activities as part of your teaching note, please provide detailed instructions on how to direct these activities.

Test & learn

When you have finished writing your case study and teaching note, test them!