Type to search

Cybersecurity Case Studies and Real-World Examples

image courtesy pixabay.com

Table of Contents

In the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity, the battle between hackers and defenders continues to shape the digital domain. To understand the gravity of cybersecurity challenges, one need only examine real-world examples—breaches that have rocked industries, compromised sensitive data, and left organizations scrambling to shore up their defenses. In this exploration, we’ll dissect notable cybersecurity case studies, unravel the tactics employed by cybercriminals , and extract valuable lessons for strengthening digital defenses.

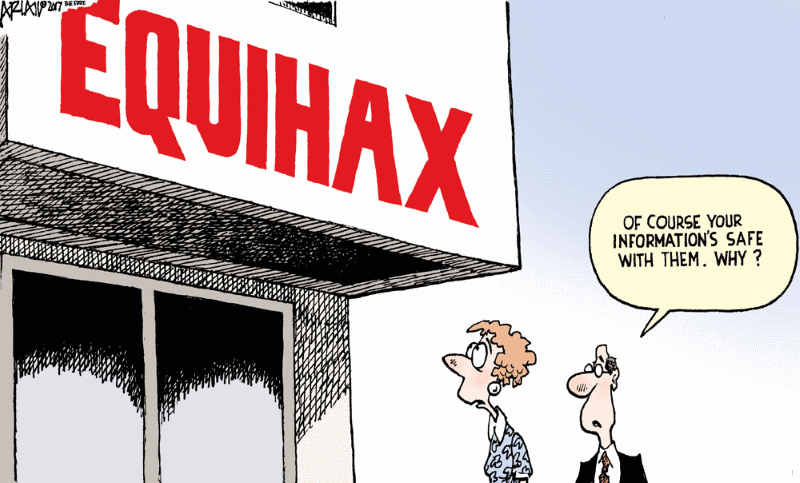

Equifax: The Breach that Shattered Trust

In 2017, Equifax, one of the largest credit reporting agencies, fell victim to a massive data breach that exposed the personal information of nearly 147 million individuals. The breach included sensitive data such as names, Social Security numbers, birthdates, and addresses, leaving millions vulnerable to identity theft and fraud.

Lessons Learned

1. Patch Management is Crucial:

The breach exploited a known vulnerability in the Apache Struts web application framework. Equifax failed to patch the vulnerability promptly, highlighting the critical importance of timely patch management. Organizations must prioritize staying current with security patches to prevent known vulnerabilities from being exploited.

2. Transparency Builds Trust:

Equifax faced severe backlash not only for the breach itself but also for its delayed and unclear communication with affected individuals. Transparency in communication is paramount during a cybersecurity incident. Organizations should proactively communicate the extent of the breach, steps taken to address it, and measures for affected individuals to protect themselves.

Target: A Cybersecurity Bullseye

In 2013, retail giant Target suffered a significant breach during the holiday shopping season. Hackers gained access to Target’s network through a third-party HVAC contractor, eventually compromising the credit card information of over 40 million customers and the personal information of 70 million individuals.

1. Third-Party Risks Require Vigilance:

Target’s breach underscored the risks associated with third-party vendors. Organizations must thoroughly vet and monitor the cybersecurity practices of vendors with access to their networks. Note that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

2. Advanced Threat Detection is Vital:

Target failed to detect the initial stages of the breach, allowing hackers to remain undetected for an extended period. Implementing robust advanced threat detection systems is crucial for identifying and mitigating breaches in their early stages.

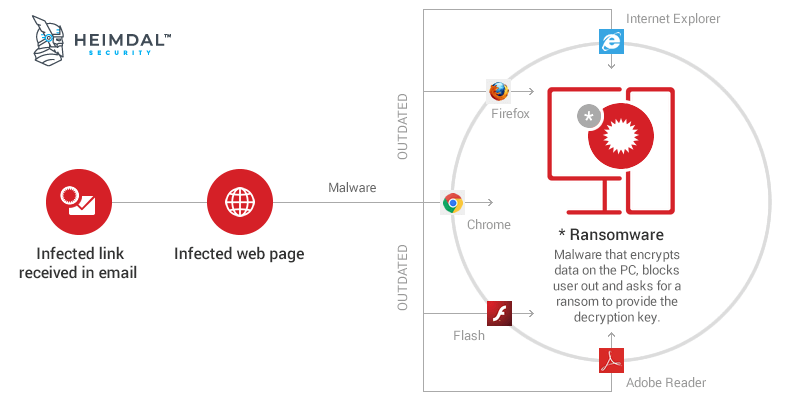

WannaCry: A Global Ransomware Epidemic

In 2017, the WannaCry ransomware swept across the globe, infecting hundreds of thousands of computers in over 150 countries. Exploiting a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows, WannaCry encrypted users’ files and demanded ransom payments in Bitcoin for their release.

1. Regular System Updates are Non-Negotiable:

WannaCry leveraged a vulnerability that had been addressed by a Microsoft security update months before the outbreak. Organizations fell victim due to delayed or neglected updates. Regularly updating operating systems and software is fundamental to thwarting ransomware attacks .

2. Backup and Recovery Planning is Essential:

Organizations that had robust backup and recovery plans were able to restore their systems without succumbing to ransom demands. Implementing regular backup procedures and testing the restoration process can mitigate the impact of ransomware attacks.

Sony Pictures Hack: A Cyber Espionage Saga

In 2014, Sony Pictures Entertainment became the target of a devastating cyberattack that exposed an array of sensitive information, including unreleased films, executive emails, and employee records. The attackers, linked to North Korea, sought to retaliate against the film “The Interview,” which portrayed the fictional assassination of North Korea’s leader.

1. Diverse Attack Vectors:

The Sony hack demonstrated that cyber threats can come from unexpected sources and employ diverse attack vectors. Organizations must not only guard against common threats but also be prepared for unconventional methods employed by cyber adversaries .

2. Nation-State Threats:

The involvement of a nation-state in the attack highlighted the increasing role of geopolitical motivations in cyber incidents. Organizations should be aware of the potential for state-sponsored cyber threats and implement measures to defend against politically motivated attacks.

Marriott International: Prolonged Exposure and Ongoing Impact

In 2018, Marriott International disclosed a data breach that had persisted undetected for several years. The breach exposed personal information, including passport numbers, of approximately 500 million guests. The prolonged exposure raised concerns about the importance of timely detection and response.

1. Extended Dwell Time Matters:

Marriott’s breach highlighted the significance of dwell time—the duration a threat actor remains undetected within a network. Organizations should invest in advanced threat detection capabilities to minimize dwell time and swiftly identify and mitigate potential threats.

2. Post-Breach Communication:

Marriott faced criticism for the delayed communication of the breach to affected individuals. Prompt and transparent communication is vital in maintaining trust and allowing individuals to take necessary actions to protect themselves.

SolarWinds Supply Chain Attack: A Wake-Up Call

In late 2020, the SolarWinds supply chain attack sent shockwaves through the cybersecurity community. Sophisticated threat actors compromised SolarWinds’ software updates, enabling them to infiltrate thousands of organizations, including government agencies and major corporations.

1. Supply Chain Vulnerabilities:

The incident underscored the vulnerability of the software supply chain. Organizations must conduct thorough assessments of their suppliers’ cybersecurity practices and scrutinize the security of third-party software and services.

2. Continuous Monitoring is Essential:

The SolarWinds attack highlighted the importance of continuous monitoring and threat detection. Organizations should implement robust monitoring systems to identify anomalous behavior and potential indicators of compromise.

Notable Lessons and Ongoing Challenges

1. Human Element:

Many breaches involve human error, whether through clicking on phishing emails or neglecting cybersecurity best practices. Cybersecurity awareness training is a powerful tool in mitigating the human factor. Employees should be educated on identifying phishing attempts, using secure passwords, and understanding their role in maintaining a secure environment.

2. Zero Trust Architecture:

The concept of Zero Trust, where trust is never assumed, has gained prominence. Organizations should adopt a mindset that verifies every user, device, and network transaction, minimizing the attack surface and preventing lateral movement by potential intruders.

3. Cybersecurity Collaboration:

Cybersecurity is a collective effort. Information sharing within the cybersecurity community, between organizations, and with law enforcement agencies is crucial for staying ahead of emerging threats. Collaborative efforts can help identify patterns and vulnerabilities that may not be apparent to individual entities.

4. Regulatory Compliance:

The landscape of data protection and privacy regulations is evolving. Compliance with regulations such as GDPR, HIPAA, or CCPA is not only a legal requirement but also a cybersecurity best practice. Understanding and adhering to these regulations enhances data protection and builds trust with customers.

5. Encryption and Data Protection:

The importance of encryption and data protection cannot be overstated. In various breaches, including those of Equifax and Marriott, the compromised data was not adequately encrypted, making it easier for attackers to exploit sensitive information. Encrypting data at rest and in transit is a fundamental cybersecurity practice.

6. Agile Incident Response:

Cybersecurity incidents are inevitable, but a swift and agile incident response is crucial in minimizing damage. Organizations should regularly test and update their incident response plans to ensure they can respond effectively to evolving threats.

7. User Awareness and Training:

Human error remains a significant factor in many breaches. User awareness and training programs are essential for educating employees about cybersecurity risks , promoting responsible online behavior, and reducing the likelihood of falling victim to phishing or social engineering attacks.

8. Continuous Adaptation:

Cyber threats constantly evolve, necessitating a culture of continuous adaptation. Organizations should regularly reassess and update their cybersecurity strategies to address emerging threats and vulnerabilities.

Conclusion: Navigating the Cybersecurity Landscape

The world of cybersecurity is a battlefield where the landscape is ever-changing, and the adversaries are relentless. Real-world case studies serve as poignant reminders of the importance of proactive cybersecurity measures . As organizations adapt to emerging technologies, such as cloud computing, IoT, and AI, the need for robust cybersecurity practices becomes more pronounced. Real-world case studies offer invaluable insights into the tactics of cyber adversaries and the strategies employed by organizations to defend against evolving threats.

Prabhakar Pillai

I am a computer engineer from Pune University. Have a passion for technical/software blogging. Wrote blogs in the past on SaaS, Microservices, Cloud Computing, DevOps, IoT, Big Data & AI. Currently, I am blogging on Cybersecurity as a hobby.

14 Comments

Hi, I believe your website mmight be having browser compatibility problems. Whenever I lokok att your blog in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping issues. I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Other than that, excellent blog!

Consider opening in chrome or Microsoftedge. Thank you for the comments

Hey! Loved your post.

This was a very insightful read. I learned a lot from it.

This is fantastic! Please continue with this great work.

Thank you for addressing such an important topic in this post Your words are powerful and have the potential to make a real difference in the world

Your writing is so engaging and easy to read It makes it a pleasure to visit your blog and learn from your insights and experiences

Your blog posts are always full of valuable information, thank you! Share the post on Facebook.

This is a must-read article for anyone interested in the topic. It’s well-written, informative, and full of practical advice. Keep up the good work!

I just wanted to say how much I appreciate your work. This article, like many others on your blog, is filled with thoughtful insights and a wonderful sense of optimism. It’s evident that you put a lot of effort into creating content that not only informs but also uplifts. Thank you.

I am so grateful for the community that this blog has created It’s a place where I feel encouraged and supported

Thank you for this insightful article. It’s well-researched and provides a lot of useful information. I learned a lot and will definitely be returning for more.

Security Framework and Defense Mechanisms for IoT Reactive Jamming Attacks – Download ebook – https://mazkingin.com/security-framework-and-defense-mechanisms-for-iot-reactive-jamming-attacks/

Leave a Comment Cancel Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Unpacking Cyber Crime: In-depth Analysis and Case Studies

- By Donald Korinchak, MBA, PMP, CISSP, CASP, ITILv3

In an era characterized by unprecedented digital connectivity, our reliance on the Internet and other digital technologies has grown exponentially. However, this dependence has also opened gates to a nefarious world of crimes committed in cyberspace, known as cyber crimes. Ranging from the theft of an individual’s personal data to crippling nations’ infrastructures, these digital felonies have evolved to become one of the most sophisticated challenges to law enforcement agencies and national security. This in-depth exploration of cybercrime provides an illumination into its diverse forms, historical progression, notorious instances, societal impact, and viable prevention strategies. This discourse aims to furnish the reader with a lucid understanding of the complex web interweaved by cybercriminals, the extensive damage they perpetrate, and, most importantly, how to arm and protect ourselves in this ongoing battle in the digital world.

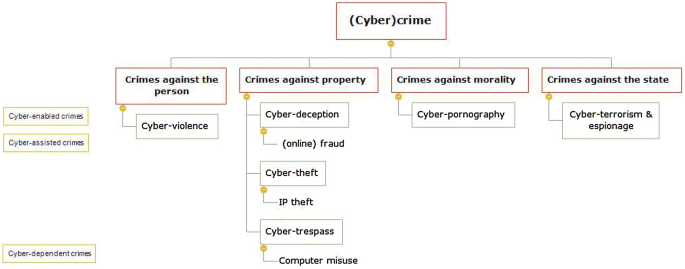

Types of Cyber Crime

Unmasking the multifaceted threat of cybercrime in our digital society.

As the digital era takes firm root, transcending almost all facets of our daily lives, it unveils an ever-evolving landscape of vulnerability to various types of cyber crimes. Understanding the nuanced complexities of these threats is indispensable in guiding our collective response to safeguard the inviolability of our virtual dwellings.

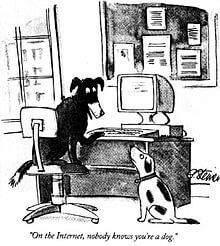

Imperative for discussion is the specter of identity theft, which involves the unlawful acquisition and utilization of another individual’s personal information for illegitimate financial gains. Cybercriminals exploit various avenues, such as phishing schemes and data breaches, to execute this violation, leading to disastrous personal and financial consequences for the victim.

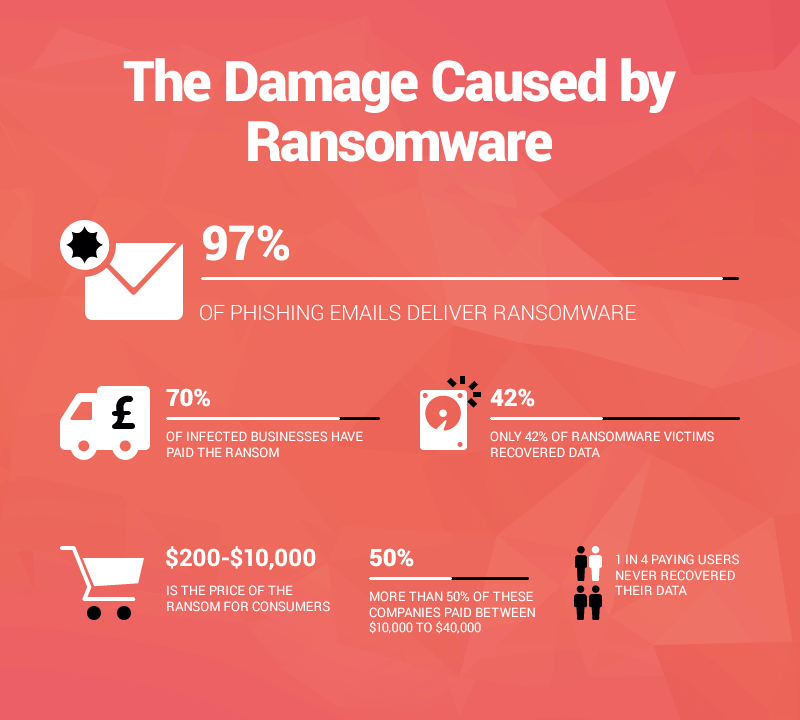

Malware , a portmanteau of malicious software, lingers as another notable threat. Ruthlessly subtle, this category of cybercrime extends to ransomware , which locks users out of their systems or data, holding it hostage until a ransom is paid. Spyware follows closely, covertly monitoring and transmitting the user’s activities to a third party. Both breed a pervasive sense of violation and create vast economic downstream effects.

Cyberstalking and cyberbullying, while demarcated less by economic impacts, remain potent narcotics in the cocktail of cybersecurity threats. These crimes are characterized by intentional intimidation, harassment, or threat to another individual, utilizing digital mediums. The psychological trauma imparted by these infringements reflects the wider societal repercussions that transcend the digital sphere.

Notably, the list would be incomplete without recognizing cyber-terrorism and cyber-warfare. These acts, striking at the intersection of technology and geopolitical maneuvering, involve the use of Internet-based attacks in terrorist activities and warfare, often targeting critical infrastructures and national security or causing a state of panic and fear.

The rapidly evolving universe of financial technology is not untouched by cybercrime. Crypto-jacking emerges as a salient threat where hackers hijack a computer’s resources to mine for cryptocurrency without the owner’s knowledge or consent— a subtle and yet potent symbol of how technology’s greatest strengths can morph into its most haunting vulnerabilities.

Lastly, the advent of Deepfakes and AI-generated content birthed a new realm of cybercrime. These acts involve the use of artificial intelligence to create or alter video, audio, or image content to depict scenes or convey messages that were never captured or intended, potentially causing severe personal, political, and societal unrest.

In navigating through the labyrinth of cybercrime, it becomes clear that our informational infrastructure functions as a double-edged sword. Heightened awareness and understanding of the multiple types of cyber crimes, corrective measures, and prevention strategies are critical to ensure the security of our accelerated journey into the digital age. As we teeter on the brink of this new epoch, let it be fortified by knowledge, caution, and, above all, a shared responsibility toward a safe and secure online world.

Historical Perspective of Cyber Crime

The evolutionary trajectories of cybercriminal strategies: a deeper dive.

While initial aspects of cybercrime, including identity theft, malware, cyberstalking, and cyber-terrorism, remain relevant, the ingenious adaptability of cybercriminals continues to morph these original paradigms into more complex constructs. Deepfakes and AI-generated content, crypto-jacking, and even cyber warfare itself continue to evolve. More recently, however, these forms of cybercrime are being joined, and in some cases superseded, by other more sophisticated threats.

Spear phishing, a targeted version of phishing, has emerged as one of the most insidious cybercrimes. Cybercriminals no longer toss out a wide net in the hopes of ensnaring an unsuspecting fish but have now shifted to crafting precise, personalized lures to hook specific individuals or organizations. This modality, premised on thorough research and social engineering , typifies today’s cunning adversary, who forgoes brute force for psychological manipulation.

Next in this progression of cybercrime sophistication is the advent of Advanced Persistent Threat s (APTs). Unlike the blitzkrieg assault-style adopted by most traditional cyberattack s, APTs are slow and methodical infiltrations designed to remain undetected for prolonged periods. By leveraging backdoor techniques and a patient, stealthy approach, these threat actors compromise systems to exfiltrate data or create systemic disruption in a silent, protracted manner.

Further underscoring the evolutionary trends, cybercriminals now employ Botnets, networks of compromised devices commanded by a central operator. The damages that can be inflicted range from devastating Distributed Denial-of-Service attacks to enormous volumes of spam mail. Cybercriminals disregard the sanctity of individual autonomy and readily surrender to the collective might of these enslaved devices.

Reflecting a leap from dexterity to craftiness, supply chain attack s represent another ingenious cybercriminal innovation. These comprise a systemic, strategic violation entailing the compromise of trusted software or hardware suppliers. By infiltrating these sources, cybercriminals can lurk undetected, poised to pounce on end-users who implicitly trust their providers and, by extension, become unsuspecting victims.

Lastly, while already touched upon in the subject of deepfakes, weaponized AI and Machine Learning take the potential for harm to unprecedented heights. As these technologies advance, they become double-edged swords, providing enormous potential benefits but also harboring potential hazards. They can be manipulated to carry out highly sophisticated attacks that adapt, learn, and emulate human behaviors, making them harder to detect and counter.

In conclusion, the cybercriminal landscape remains perpetually fluid. It continues to evolve, harboring devastating potential and emphasizing the critical need for robust countermeasures and vigilance. As much as we are captivated by technology’s spell, we must also remain equally committed to fathoming its dark possibilities and approach this evolving challenge with the same unyielding determination.

Depicting Major Cyber Crime Case Studies

When regarding the multifaceted arena of cybercrimes, a few notorious examples have made all the difference in shaping both legislative processes and public perception. These archetypical scenarios paint a stark picture of the danger posed by cybercriminals and the significant, often devastating, consequences for victims.

The infamous Yahoo data breach, which revealed itself from 2013 to 2014, can never be forgotten. It compromised approximately three billion user accounts, rendering it the most prodigious data compromise in history. Personal data, including names, email addresses, and passwords, fell into malevolent hands, leading to a leap in fraudulent activities globally. The ensuing turbulence resulted in the resignation of Yahoo’s CEO, loss of consumer trust, and a $50 million settlement.

Adobe Systems witnessed a devastating blow in October 2013—a data violation exposing approximately 38 million active user accounts. The compromised data included encrypted debit and credit card data paired with user login credentials, creating a substantial identity theft concern. Adobe had to face huge economic losses and significant reputation damage, which took years to recover from.

The Heartland Payment Systems breach in 2008 was another significant incident that stirred the digital world. Dating back to when companies scarcely understood the imminent threat of cybercrime, this attack led to a loss of over 130 million credit and debit card details. Heartland witnessed a significant financial loss of around $140 million in remediation.

In terms of affecting global infrastructure, the WannaCry ransomware attack in May 2017 was a stark example. The ransomware targeted computers running Microsoft Windows, encrypting data and demanding ransom in Bitcoin. Over 200,000 systems across 150 countries, including significant healthcare organizations, were taken hostage. The immense global disruption prompted a surge in infrastructure investment to improve cyber defense capabilities.

While most attacks impact a specific corporation or sector, the Mirai botnet attack of 2016 introduced a broader systemic threat. The malware transformed networked devices such as IP cameras, printers, and routers into a botnet to conduct distributed denial-of-service attacks. With millions of IoT devices compromised, the Mirai botnet was capable of unparalleled distributed destruction, showcasing how vulnerable global digital infrastructure can be.

Cyber espionage provides another multifaceted concern. An example was Operation Aurora in 2009, aiming to steal sensitive information from top companies, including Google and Adobe. This incident underscored the threat toward intellectual property and corporate competitive advantage, galvanizing a reevaluation of digital security measures in businesses across the world.

On the more sinister end of the spectrum, the Stuxnet worm attack showcased how cybercrime could transform into cyber warfare. In 2010, the Stuxnet worm damaged approximately one-fifth of Iran’s nuclear centrifuges, epitomizing how cyber-attacks can transgress the digital realm and enact substantial real-world damage.

Through these examples and more, it becomes perceptibly clear how multifarious the landscape of cybercrimes truly is. It underscores the imperative need for stringent cybersecurity measures, vigorous legislative action, and individual awareness of the perils that lurk in the depths of the digital world. As we further immerse ourselves in an overwhelmingly interconnected society, it is incumbent upon us to study and learn from these sobering lessons of history.

Impact of Cyber Crime on Individuals and Society

Beyond the directly visible forms of cybercrime, such as identity theft, malware, cyberbullying, deepfakes, cyberterrorism, and crypto-jacking, there lies a plethora of repercussions affecting individual victims and wider societal structures. These implications come as a direct result of cybercrime, which infiltrates various sectors, from personal privacy to economic stability, manifesting differently across each strata of society.

When confronted with the repercussions of cybercrime, it is essential to explore the psychological impact on victims. According to research conducted by the American Psychological Association, individuals who have been victims of cyber crimes often suffer from feelings of violation, loss of trust, and feelings of powerlessness. These outcomes equip cybercriminals with a powerful psychological tool – fear, which they can deploy to extort more information or inflict further harm on their victims.

The financial implications of cybercrime are also critical. On an individual level, victims may incur substantial costs to recover from identity theft or ransomware attacks. On a larger scale, businesses are also impacted—with losses in the billions annually due to cyber theft of intellectual property and sensitive corporate information.

Cyber crimes also pose a severe threat to critical infrastructure. A targeted attack, like the Stuxnet worm or the Mirai botnet attack, can disrupt entire networks or systems. This endangerment of critical infrastructures exposes vulnerabilities in sectors such as energy, telecommunications, transportation, and healthcare, upon which our societies heavily rely.

Furthermore, cybercrime disrupts social order by exploiting our increasing reliance on digital platforms. The damage caused by malicious activities in cyberspace can instigate societal tension or even panic. For instance, the spread of false information through deepfakes or AI-generated content can destabilize communities, alter public opinion, and incite fear or chaos within the public domain.

Moreover, the infiltration of educational institutions and exploitation of data breaches, such as those experienced by Adobe Systems and Yahoo, incite concern for the security of personal and academic data, impacting trust in these institutions.

Finally, the global aspect of cyber crime complicates the enforcement of laws and the attribution of criminals. Differing legislation across jurisdictions, coupled with the abstract nature of cyberspace, often leads to perpetrators evading justice, which again amplifies public fear and mistrust.

The increasing sophistication of cyber criminal activities demands a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to cybersecurity involving not only technological solutions but also legislative measures, international cooperation, and public awareness initiatives. Vigilance remains paramount – for both the individual and the broader social structures at risk.

In conclusion, while the repercussions of cybercrime are manifold and persistently evolving, the driving force behind combating this modern plague remains undeterred – a relentless commitment to understanding, outwitting, and ultimately neutralizing this digital threat. The continuous enhancement of cybersecurity measures, active legislative action on cybercrimes, and individual awareness of cybercrime risks are just several in the legion of dedicated efforts aimed to equip society with the tools necessary to tackle this complex issue.

Prevention and Mitigation Strategies

Effectively addressing the potential risks and outcomes of cybercrimes necessitates a multi-pronged approach that leans heavily on collaboration, education, and the implementation of cutting-edge cybersecurity strategies. this measure rings especially pertinent against the backdrop of a progressively interconnected world, teetering on the precipice of the much-heralded fourth industrial revolution..

Collaborating across sectors and agencies is a vital strategy for tackling cybercrimes. Internationally, creating a shared understanding of cyber threats and fostering cooperation to deal with them can significantly bolster collective security measures. This includes forming partnerships with international police forces, such as INTERPOL and Europol, to expedite the identification, tracking, and prosecution of cybercriminals regardless of their geographical location.

An educated populace is arguably the first line of defense against cybercrime. The general public must be armed with the knowledge necessary to safeguard sensitive information and thwart the attempts of cybercriminals. Robust security awareness programs must be incorporated into our educational institutions, corporations, and public services, acquainting people with the modus operandi of cybercriminals and how best to respond. This includes increased awareness of the intricacies of social engineering attacks to mitigate risks like whaling and pretexting that have not been previously covered in this article.

Implementing progressive cybersecurity protocols plays a pivotal role in curbing cybercrimes. Organizations should strive for a dynamic, proactive approach as opposed to a static, reactive one. Frequent system audits, vulnerability assessments, and penetration testing can unveil potential security loopholes before cybercriminals can exploit them. A zero-trust architecture that presumes no user or process is intrinsically trustworthy, coupled with behavioral-based threat detection, could significantly bolster an organization’s defense.

Moreover, using encrypted communication channels and urging employees to regularly update their passwords and employ two-factor authentication systems can mitigate unauthorized access risks. Leveraging advanced technologies, like quantum cryptography, can offer foolproof data security, rendering any eavesdropping attempts futile.

Lastly, while strengthening legislative measures against cybercrimes, nations must also create an environment conducive to the reporting of such incidents. Victims often shy away from reporting due to fear of reputational damage or lack of faith in the justice system. Ensuring confidentiality and demonstrating stringent punishment against perpetrators could effectively deter the commission of these crimes.

As we tiptoe into an era dominated by Big Data, 5G, and Artificial Intelligence, our strategies against cybercrime must evolve at a concordant, if not more rapid, pace. A synergized effort spanning individuals, organizations, and countries, buttressed by relentless vigilance, is our best hope in the grand scheme of cybersecurity. Striking that balance between advancing technologically and maintaining cyber hygiene will be the perpetual litmus test for our digitized world.

As we continue to tread through this digital age, understanding the insidious nature of cyber crimes not only informs but empowers us as individuals, organizations, and as a society. We have explored in detail the varied forms of these crimes, their evolution through the years, their devastating impacts exemplified through notable case studies, and the undeniably lasting mark they leave on individuals and societies alike. Furthermore, we have offered a glimpse into the strategies that can be employed to fortify our defenses against these invisible aggressors. The key lies in continual awareness, constant vigilance, and strategic preparedness so that we may navigate this intricate digital universe safely. As we move forward, remember the fight against cybercrime isn’t just for those in the corridors of power but for every Internet user who plays a vital role in this digital ecosystem.

Donald Korinchak, MBA, PMP, CISSP, CASP, ITILv3

Cybercrime case studies

On this page, online grooming, online scams, malware and intimate image abuse.

Online child grooming is befriending a child, and sometimes the family, to make the child more open to sexual abuse. A person who is found guilty of grooming in Victoria is liable to 10 years imprisonment.

What happened?

David is a working dad with three children: Daniel and Matilda (7) and Angie (14). Angie has just commenced her second year of high school. Angie begged David for a smartphone. David finally relents and gives Angie his old smartphone. As a condition for receiving the phone, Angie must share her passcode and must leave the phone to charge overnight in the kitchen.

Angie spends a lot of time on her phone. David will often ask Angie what she is doing on the phone. He tries to monitor her use and keeps track of the phone bill. David has to start working long nights on a special project for work. David is not able to monitor Angie’s phone use as closely. Soon, Angie begins to keep her phone in the room overnight.

As the months go by, David notices Angie’s behaviour changes. She becomes withdrawn and irritable. Her school work starts to suffer.

David receives a call from the school principal – the principal needs an urgent meeting with David. The principal tells David that a parent of one of Angie’s friends told the principal that Angie is in contact with a man online who sends Angie inappropriate messages. David talks to Angie and learns that she met this man on a messaging app and they message constantly.

How was David affected?

David is horrified and feels like he has failed Angie. He feels he has neglected his duty as a parent.

David is devastated that Angie did not tell him what was happening.

David feels powerless to keep his child safe. David starts to suffer from anxiety, affecting his work and relationships.

Romance and dating scams involve scammers taking advantage of people looking for romantic partners, often via dating websites, apps or social media, by pretending to be prospective companions. They play on emotional triggers to extract money, gifts or personal details.

Romance baiting encourages victims to take advantage of a fake investment opportunity.

Amara received and accepted a friend request from Ferenc, a Hungarian serviceman on peacekeeping duties in Afghanistan. Ferenc and Amara grew closer together. Ferenc shared pictures with her and told Amara he had lost his wife to cancer. This was similar to Amara’s own experience – her elderly husband died of cancer two years ago.

Ferenc said he was being posted to Cyprus but that his time in the military was nearly finished. Ferenc told Amara he wanted to set up a jewellery store when he retired.

Ferenc told Amara he was coming to see her but had some trouble with his bank card not working in Cyprus and could not get funds to pay for an export tax on his gemstones. Taking out a loan, Amara transferred Ferenc $15,000 to cover the tax bill. Shortly after, Ferenc told Amara that he had been detained by local authorities in Malaysia on the way to Australia. He needed $20,000 to pay his legal and court fees.

Amara contacted the Malaysian police – they had no knowledge of Ferenc. When Amara told Ferenc she could not send the additional money, he responded with very angry messages, and then ceased contact altogether.

How was Amara affected?

Amara was left confused and hurt. She feels betrayed and cheated. She knows in her head that this was a scam, but in her heart still feels that Ferenc might be out there and she has let him down.

Amara had to re-enter the workforce to service the loan she took. She is also at risk of having her identity stolen because she shared a lot of personal information with the scammer calling himself Ferenc.

Ransomware is a form of extortion using malicious software (malware) that prevents users from accessing their system or personal files and demands ransom payment in order to regain access.

Jin and Bella run a family owned accounting firm that provides outsourced bookkeeping and accounts functions for small businesses across Victoria.

The business operates through an online platform—client companies log in through a website portal and can take care of several bookkeeping needs for their businesses, such as tracking their expenses, processing receipts and calculating deductions.

Jin and Bella’s business computers were infected with ransomware via a suspect email just before tax time. This ransomware locked down the business’ platform so that clients were unable use the portal. The cybercriminals demanded $100,000 in Bitcoin, a cryptocurrency, to restore the network. Jin and Bella refused to pay. The cybercriminals threatened to publish the private information of Jin and Bella’s clients. Jin and Bella did not know what to do. They did not have the money to pay the ransomware. Eventually, Jin and Bella contacted Victoria Police to report the crime.

The majority of Jin and Bella’s clients were unable to submit their tax returns on time. Clients were extremely dissatisfied with the service.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre advises against paying ransoms. Payment of the ransom may increase an individual or organisation’s vulnerability to future ransomware incidents. In addition, there is no guarantee that payment will undo the damage.

How were Jin, Bella and their clients affected?

The reputation of Jin and Bella’s business suffered and as a result, they lost clients. Jin and Bella experienced considerable stress and anxiety from the attack.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre advises against paying ransoms. Payment of the ransom may increase an individual or organisation’s vulnerability to future ransomware incidents. In addition, there is no guarantee that payment will undo the damage.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre has observed cybercriminals successfully using ransomware to disrupt operations and cause reputational damage to Australian organisations across a range of sectors:

- State and Territory governments

- Education and research organisations

The Australian Cyber Security Centre reported a 15% increase in ransomware cybercrime reports in the 2020–21 financial year. 21

Image-based sexual abuse is the creation, distribution or threatened distribution of intimate, nude or sexual image or videos, without the consent of the person pictured. This includes images or videos that have been digitally altered using specialised software.

You can also report image-based abuse to the eSafety Commissioner .

Deepfakes use artificial intelligence software to learn from large numbers of images or recordings of a person to create an extremely realistic but false depiction of them doing or saying something that they did not actually do or say. 24

Aisha is a teacher who unknowingly had malware called a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) downloaded onto her smart phone.

Using the RAT, a cybercriminal accessed her email and text messages, and forwarded some private, intimate pictures to colleagues and family members in her contacts.

The cybercriminal also posted these images, as well as some digitally altered “deepfakes”, to several adult websites. Some of these images were found by students at Aisha’s school.

Aisha did not make a report to Victoria Police, but tried to track down the websites where the images were posted to demand that they were taken down. She suspects that her ex-boyfriend – who has a history of control and emotionally abusive behaviour – was behind the attack, but she did not have any way to prove this.

How was Aisha affected?

Aisha has been devastated by these events— both privately and professionally.

Although her school ultimately understood that she was a victim, the damage to her reputation was irreversible. This, coupled with the anxiety that her students had seen these personal and deepfake images of her, led to her giving up her teaching position at the school. This was her primary source of income.

18 Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, 12 February 2021, Romance Baiting Scams on the Rise, https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/romance-baiting-scams-on-the-rise

19 Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, 12 February 2021, Romance Baiting Scams on the Rise, https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/romance-baiting-scams-on-the-rise

20 Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, 12 February 2021, Romance Baiting Scams on the Rise, https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/romance-baiting-scams-on-the-rise

21 Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2021, ACSC Annual Cyber Threat Report: 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021

22 Office of the eSafety Commissioner, October 2017, Image-Based Abuse, National Survey: Summary Report (October 2017) https://www.esafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-07/Image-based-abus…

23 Office of the eSafety Commissioner, October 2017, Image-Based Abuse, National Survey: Summary Report (October 2017) https://www.esafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-07/Image-based-abus…

24 eSafety Commissioner, Deepfake trends and challenges — position statement, https://www.esafety.gov.au/about-us/tech-trends-and-challenges/deepfakes

Updated 30 March 2023

A Comprehensive Analysis of High-Impact Cybersecurity Incidents: Case Studies and Implications

- October 2023

- Thesis for: Master`s Degree

- Advisor: Dr. Anişoara Pavelea

- Babeş-Bolyai University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Himani Mittal

- James Womack

- Christopher Brito

- Xavier-Lewis Palmer

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Hackers and cybercrime prevention

Getty Images

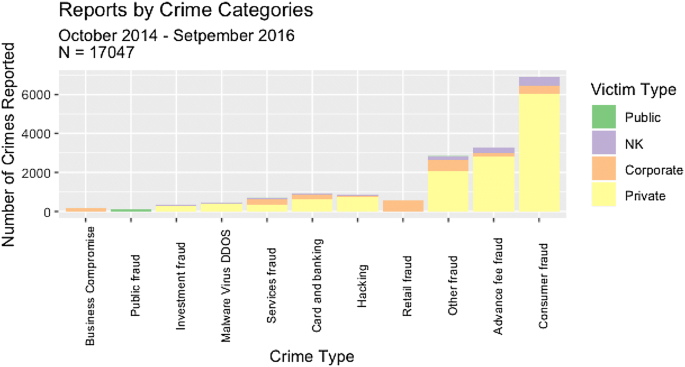

Top 10 cyber crime stories of 2020

Here are computer weekly’s top 10 cyber crime stories of 2020.

- Alex Scroxton, Security Editor

The past 12 months have seen an unprecedented surge in cyber criminal activity, with two key trends explaining much of the increase – the Covid-19 pandemic introduced new attack surfaces and opportunities for malicious actors, while new developments in ransomware extortion tactics saw millions lost to operators such as Maze, Sodinokibi, Egregor and others.

Here are Computer Weekly’s top 10 cyber crime stories of 2020:

1. Cyber gangsters demand payment from Travelex after Sodinokibi attack

Foreign exchange company Travelex is facing demands for payment to decrypt critical computer files after it was hit by one of the most sophisticated ransomware attacks , known as Sodinokibi , which disabled its IT systems on New Year’s Eve .

The company, which has operations in 70 countries, has faced days of disruption after criminal hackers penetrated its computer networks and delivered a devastating attack timed to hit the company when many of its staff were on holiday.

According to security specialists, criminals are demanding a six-figure sum to supply Travelex with decryption tools that will allow it to recover the contents of files across its computer network that have been encrypted by the virus.

2. List of Blackbaud breach victims tops 120

The UK’s National Trust has joined a growing list of education and charity organisations to have had the data of their alumni or donors put at risk in a two-month-old ransomware incident that occurred at US cloud software supplier Blackbaud .

According to the BBC , the Trust, which operates hundreds of important and historical sites across the country, including natural landscapes and landmarks, parks, gardens and stately homes, said that data on its volunteers and fundraisers had been put at risk, but data on its 5.6 million members was secure.

The organisation is conducting an investigation and informing those who may be affected. As per the UK’s data protection rules, it has also reported the incident to the Information Commissioner’s Office, which is now dealing with a high volume of reports, including Blackbaud’s.

3. IT services company Cognizant warns customers after Maze ransomware attack

Cognizant has warned that a cyber attack by the Maze ransomware group has hit services to some customers.

The IT services company, which has a turnover of over $16bn and operations in 37 countries, said the attack, which took place on Friday 17 April, had caused disruption for some of its clients.

Cognizant, which supplies IT services to companies in the manufacturing, financial services, technology and healthcare industries, confirmed the attack in a statement on Saturday 18 April.

4. Phishing scam targets Lloyds Bank customers

Customers of Lloyds Bank are being targeted by a phishing scam that is currently hitting email and text message inboxes.

Legal firm Griffin Law has alerted people to the scam after being made aware of about 100 people who have received the messages.

The email, which looks like official Lloyds Bank correspondence, warns customers that their bank account has been compromised. It reads: “Your Account Banking has been disabled, due to recent activities on your account, we placed a temporary suspension untill [sic] you verify your account.”

5. Coronavirus now possibly largest-ever cyber security threat

The total volume of phishing emails and other security threats relating to the Covid-19 coronavirus now represents the largest coalescing of cyber attack types around a single theme that has been seen in a long time, and possibly ever, according to Sherrod DeGrippo, senior director of threat research and detection at Proofpoint.

To date, Proofpoint has observed attacks ranging from credential phishing, malicious attachments and links, business email compromise, fake landing pages, downloaders, spam, and malware and ransomware strains, all being tied to the rapidly spreading coronavirus.

“For more than five weeks, our threat research team has observed numerous Covid-19 malicious email campaigns, with many using fear to try to convince potential victims to click,” said DeGrippo.

6. Cyber gangsters hit UK medical firm poised for work on coronavirus with Maze ransomware attack

Cyber gangsters have attacked the computer systems of a medical research company on standby to carry out trials of a possible future vaccine for the Covid-19 coronavirus .

The Maze ransomware group attacked the computer systems of Hammersmith Medicines Research , publishing personal details of thousands of former patients after the company declined to pay a ransom.

The company, which carried out tests to develop the Ebola vaccine and drugs to treat Alzheimer’s disease, performs early clinical trails of drugs and vaccines.

7. Cosmetics company Avon offline after cyber attack

Parts of the UK website of Brazilian-owned cosmetics and beauty company Avon remain offline more than a week after an alleged ransomware attack on its IT systems.

The attack is understood to have impacted the back-end systems used by its famous sales representatives in multiple countries besides the UK, including Poland and Romania, which are now back online. This has left people unable to place orders with the company.

Avon disclosed the breach in a notification to the US Securities and Exchange Commission on 9 June 2020 , saying it had suffered a “cyber incident” in its IT environment that had interrupted systems and affected operations.

8. Travelex hackers shut down German car parts company Gedia in massive cyber attack

The criminal group responsible for the cyber attack that has disrupted high-street banks and the foreign currency exchange chain Travelex for more than three weeks has launched what has been described as a “massive cyber attack” on a German automotive parts supplier.

Parts manufacturer Gedia Automotive Group , which employs 4,300 people in seven countries, said today that the attack will have far-reaching consequences for the company, which has been forced to shut down its IT systems and send staff home.

The 100-year-old company, which has its headquarters in Attendorn, said in a statement posted on its website that it would take weeks or months before its systems were fully up and running.

9. Carnival cruise lines hit by ransomware, customer data stolen

Cruise ship operator Carnival Corporation has reported that it has fallen victim to an unspecified ransomware attack which has accessed and encrypted a portion of one of its brand’s IT systems – and the personal data of both its customers and staff may be at risk.

Carnival, which like the rest of the travel industry has been stricken by the Covid-19 pandemic – it also operates Princess Cruises, owner of the ill-fated Diamond Princess , which found itself at the centre of the initial outbreak – reported the incident to the US Securities and Exchange Commission on 17 August.

In its form 8-K filing, the company said the cyber criminals who accessed its systems also downloaded a number of its data files, which suggests it may be at imminent risk of a double extortion attack of the sort perpetrated by the Maze and ReVIL/Sodinokibi groups.

10. Law firm hackers threaten to release dirt on Trump

The cyber criminal gang behind the ReVIL or Sodinokibi ransomware attack on New York celebrity law firm Grubman, Shire, Meiselas and Sacks (GSMS) have doubled their ransom demand to $42m and threatened to publish compromising information on US president Donald Trump , according to reports.

In a statement seen by entertainment news website Page Six , the Sodinokibi group – which has also gone by the name Gold Southfield – said they had found “a ton of dirty laundry” on Trump.

The threat reportedly reads: “Mr Trump, if you want to stay president, poke a sharp stick at the guys [GSMS], otherwise you may forget this ambition forever. And to you voters, we can let you know that after such a publication, you certainly don’t want to see him as president. The deadline is one week.”

Read more on Hackers and cybercrime prevention

Top 10 investigations and national security stories of 2020

Maze ransomware shuts down with bizarre announcement

Cyber attack combined with Covid-19 puts Travelex into administration

Canon said to be latest Maze ransomware victim

The next U.S. president will set the tone on tech issues such as AI regulation, data privacy and climate tech. This guide breaks ...

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz supports climate action and released a Climate Action Framework detailing steps for the state to become ...

Remedies in the Google online search antitrust case could include eliminating the company's use of distribution contracts that ...

Highlights from Black Hat USA 2024 include a keynote panel on securing election infrastructure as well as several sessions on ...

Although Flashpoint is known for their cybersecurity threat intelligence services, the vendor also provides physical security ...

Cutting through an EDR tool's marketing hype is difficult. Ask vendors questions, and conduct testing before buying a tool to ...

Network architects face challenges when considering a network upgrade, but enterprises can keep problems to a minimum by ...

Wireshark is a useful tool for capturing network traffic data. Network pros can make the most of the tool by analyzing captured ...

IP addressing and subnetting are important and basic elements of networks. Learn how to calculate a subnet mask based on the ...

Tests off coastlines around the world are measuring the feasibility of underwater data centers. With proper maintenance and ...

Sustainable and renewable energy sources are necessary for data centers to meet emissions requirements by 2030. Nuclear power is ...

Intel's failure to profit from the red-hot AI market is behind plans to cut 15,000 jobs. The workforce reduction is part of a $10...

Vector databases excel in different areas of vector searches, including sophisticated text and visual options. Choose the ...

Generative AI creates new opportunities for how organizations use data. Strong data governance is necessary to build trust in the...

Snowpark Container Services aims to provide the vendor's users with a secure environment for deploying and managing models and ...

Partner Overview

Join Us for Growth, Innovation and Cybersecurity Excellence.

Become a Channel Partner

Be a Valued Partner and Embark on a Journey of Profitability.

Partner Portal

Unified Security Platform

Latest Content and Resources

Threat Report 2023

NRGi Holding Case Study

The 15 Internet Crime Stories That Make Cybersecurity Measures Essential

Read the best, most fascinating tech stories that cover the risks of the digital landscape and find out how to stay safe

Last updated on February 28, 2024

Internet crime stories are dime a dozen but these examples will show you why online security is essential. From ethical hacking to blackmail and car hijacking, these true stories show how you must act now to secure your well-being in the digital landscape. We carefully curated the best, most fascinating tech stories that cover the risks involved in any digital activity of device, so use the links below to navigate them.

- The mom whose laptop was locked down by a ransomware attack

- Tom was blackmailed because of his hacked Ashley Madison account

- How ethical hackers took over her PC

- They remote hacked his car

- Ransomware deletes 2 years of academic papers

- His WoW account got hacked. Twice

- Your data has been breached

- Catfish isn’t dinner, it’s lies, manipulation, and theft

- Hillary Clinton’s Aides Got Phished And Lost Her The Election

- He fell prey to the same scam twice and lost $1,350

- Who would want to be you? Some can even become You.

- When your workplace, a gaming giant, gets hit

- The casual, public Wi-Fi hack

- Customer support falls prey to a social engineering hack

- Hotel managers and clients had nightmares due to one lock hack posted

Cyber security incidents and getting hacked seem like distant, fascinating things where other people get hurt, but you stay safe. Truth is, getting hacked or scammed can happen to anyone and it might even have happened to you in the past.

The average number of devices used by you and most people have increased exponentially in the recent years. We’re surrounded by IoT devices, wear smart bracelets, have friends who are betting their savings on cryptocurrency, and we sign up to dozens of social media platforms.

This means cyber attacks have a lot of ways to get to you – either by targeting you specifically or by simply compromising your info in large-scale attacks. The best way to learn is through experience, so let’s do just that.

Here are the real stories of people who got hacked and what they learned, plus some actionable tips to enhance your security.

1. The mom whose laptop was locked down by a ransomware attack

Two days before Thanksgiving, Alina’s mother got hit by a ransomware attack. 5,726 files got locked by CryptoWall , an encryption malware so powerful it is almost impossible to recover the information.

Alina’s mom contacted the attacker through the ransomware’s communication feature.

As all ransomware creators, he told her she can either pay to get her files back or lose them forever.

The price to unlock her files was 500$ in the first week and 1000$ in the second one, after which the files would be deleted.

Payment was to be done in Bitcoin, a complicated process which she had to learn on the fly.

Because of a major snowstorm that closed down the banks, Alina’s mom couldn’t pay the ransom in the first week, and ended up having to plead with her attacker to not increase the price to 1,000$.

Surprisingly, he accepted and gave her the key to unlock her files. However, no one should ever pay a ransom, the risks far outweigh the benefits.

T he full story is here: How my mom got hacked & What I’ve learned after my mom got hacked (and her data held for ransom)

Find out what steps to take for your protection: WHAT IS RANSOMWARE AND 9 EASY STEPS TO KEEP YOUR SYSTEM PROTECTED

2. tom was blackmailed because of his hacked ashley madison account.

After the Ashley Madison hack, cyber criminals contacted him and demanded 500$ to remove his name from a publicly searchable registry.

If not, they would also send an email to his family, informing them of Tom’s affair. Tom refused, believing that if he paid them, they would know that he had something to lose and could be blackmailed further.

He was wise, but that didn’t mean he didn’t suffer. In the end, Tom had to live knowing his affairs on AM could be exposed at any time by the hackers.

Moreover, there were also people who took it up upon themselves to impart justice on people in circumstances they couldn’t, or wouldn’t, understand.

The story: In Ashley Madison’s wake, here’s one man’s story of sex, sorrow and extortion

Securing your pc doesn’t have to be expensive: 13 free pc security hacks to build your online protection, 3. how ethical hackers took over her pc.

Sophie is a technology reporter at the Daily Telegraph.

As part of an assignment, she accepted to be part of an ethical hacking experiment. Basically, a group of ethical hackers would try to compromise her system without her knowing how, when and where.

They pretended to be whistleblowers in control of sensitive government information and sent her an email with some of the files attached.

The malware infection occurred the moment she opened the file, and the attackers got access to everything, including email address and web cam. And it wasn’t even that difficult to do.

The story: How hackers took over my computer

This is how you can protect your email address: the complete guide to email security, 4. they remote hacked his car.

Andy Greenberg, a senior writer at Wired, once took part in a groundbreaking experiment which tested how car hacking could be done.

Next, the transmission was cut and finally, they remotely activated the breaks. And they did all of these things with Andy behind the wheel.

The experiment uncovered a massive flaw in Jeep’s cars which was later fixed. Today, this is even easier to achieve, due to the rise of electric cars and the huge push towards autonomous vehicles like trucks, taxis and more.

The story: Hackers Remotely Kill a Jeep on the Highway—With Me in It

Learn more about how software can expose you, something that works the same way whether we’re talking about computers or self-driving cars: 8 vulnerable software apps exposing your computer to cyber attacks, 5. ransomware deletes 2 years of academic papers.

What’s the first thing people do when they get hit by a malware attack? They panic and ask for help in a dedicated forum: “My PC is infected.

Please, can anyone help me? ”

For this user however, it was too little, too late. For 2 years he worked on his academic papers, and then they got encrypted by ransomware.

The timing was awful as well: it happened right before they were due. Antivirus didn’t help and he had no backup.

We hope he didn’t pay.

What we do know is that ransomware attacks are much more frequent that you can imagine and they target individuals and businesses alike.

The story: My PC got hacked by troldesh ransomware. please is there anyone who can help.

Find out how to backup your data so ransomware does not affect you: how to backup your computer – the best advice in one place, 6. his wow account got hacked. twice.

Gamers are favorite targets for cyber criminals, since they don’t want to lose the time and money invested in a character and are willing to pay the ransom.

As a result of a potential phishing attempt, this guy had his WoW account hacked and all his progress lost. And it happened to him not once, but twice!

The same type of attack happens in most popular online games.

League of Legends phishing volumes are truly legendary, so we talked to their security team to find out how to avoid getting your account stolen.

The story: So my WoW account got hacked… twice.

Learn more about security and gaming: gamers, time to take your cyber security to the next level, 7. your data has been breached.

The Office of Personnel Management, OPM for short, can be considered the US Government’s HR Department.

Among other things, it keeps records of employee personal information, such as height, weight, hair and eye color.

In 2014, the OPM got hacked, and the information of 22 million government employees leaked, most likely in the hands of a foreign government.

143 million US consumers had their sensitive personal information exposed. That’s 44% of the population and today we’re still seeing reports of more Equifax leaks.

Odds are, if you’re a US citizen, your info is floating around on the dark web , at the mercy of cyber criminals. What do you think the US government did to deal with the Equifax hack?

After less than one month since the incident, the IRS awarded Equifax a contract for fraud detection. Clearly, it’s up to you and you alone to protect your identity.

The story: OPM got hacked and all I got was this stupid e-mail

Learn how to stay as safe as possible from identity theft: how to prevent identity theft in 20 essential steps, 8. catfish isn’t dinner, it’s lies, manipulation and theft.

Some people hack you not with malware or suspicious links, but by gaining your trust and love.

This journalist’s mother started using the online dating site Match.com, and eventually formed a connection with a soldier on active duty in Afghanistan.

After a while, the soldier asked for a 30,000$ loan to help him clear a sizeable inheritance of gold and jewelry from US customs.

By now, the journalist and her brother intervened, suspecting the soldier was catfishing their mother.

In the Match.com case, the victims confronted the man with their suspicions and other evidence they had accumulated over time.

The supposed soldier revealed he was a man from Ghana trying to support his sisters, and scamming people online was the best way he knew how to do that.

The story: My mom fell for a scam artist on Match.com—and lived to tell the tale

Learn about the top online scams and how to avoid them: top 11 scams used by online criminals to trick you, 9. hillary clinton’s aides got phished and lost her the election.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you definitely know why Hillary Clinton lost the US Election to Donald Trump.

When forwarding the phishing email to a computer technician, he wrote “This is a legitimate email” instead of “illegitimate”. This gave hackers from Russia access to about 60,000 emails from Podesta’s private Gmail account.

They stole all that data, gave it to Wikileaks, and the rest is actual history.

“The FBI’s laid-back approach meant that Russian hackers were able to roam inside the DNC’s computer systems for almost seven months before Democratic officials finally realised the gravity of the attack and brought in external cybersecurity experts.”

But it was too late, as the election results have shown.

The story: Top Democrat’s emails hacked by Russia after aide made typo, investigation finds

Learn why phishing is so effective and how you can avoid it: 15 steps to maximize your financial data protection, 10. he fell prey to the same scam twice and lost $1,350.

In 2007, Justin was at a difficult point in his life.

Unemployed, with a weak skill set and verging on alcoholism, Justin decided to turn his life around by moving to Italy.

Determined to find a cheap flight, Justin searched for sellers of frequent flyer miles.

He found two sellers and talked to them over the phone. One of them even sent him a photo of his driver’s license. In a twisted sequence of events, both of them scammed him for a total sum of 1350$.

Sounds unlikely?

Think again. Justin tried to find a cheap shortcut and get that ‘too good to be true’ deal and became blind to any potential scammers.

Plus, the phone conversations and photos helped dispel any suspicions he might have. This is how most scamming attempts succeed, by preying on people who give in to the fear of missing out.

The story: How I Lost $1,350 by Falling for the Same Internet Scam Twice in One Week

Learn more about how social scams work and how to avoid them: social scams – the full breakdown and protection plan, 11. who would want to be you some can even become you..

One day, Laura received a call from her credit card company, saying someone else had tried to obtain a credit card using her name, address and social security number.

Eventually, she guessed the answers and saw the extent of the damage.

The impersonator had created more than 50 accounts in Laura’s name, and got credit for utilities such as heat, cable, electricity and even a newspaper subscription.

What’s more, the companies went after Laura in order to get their money back.

After notifying the police and tracking down the impersonator, Laura got a court order and managed to fix a lot of the damage, but only after a lot of sweat and stress.

While her case was a fortunate one, few people share her luck and this story should act as a reminder to always safeguard your personal information.

Another stolen identity case created a buzz on Reddit . This user had an argument with an old roommate, who then decided to take revenge.

He created social media accounts using the victim’s name, photoshopping the person with an ISIS flag and posting questionable content The story: ‘Someone had taken over my life’

While a scary and multifaceted attack, it is possible to protect yourself against these types of threats. Here are 20 SECURITY STEPS YOU SHOULD TAKE TO PREVENT IDENTITY THEFT.

12. when your workplace, a gaming giant, gets hit.

In late 2014, one of the biggest and most expensive hacks ever recorded took place at Sony and one employee reveals the inside situation.

Half of the companies 6800 computers and servers were rendered dead and had ALL of their information stolen and deleted.

As a result, employees had to rewrite every single deleted file by hand. Paper became the main form of communication, used in written memos and to-do-lists, even their salaries were paid using hand-written checks.

The damage didn’t stop there.

The hackers got a hold of employee personal information. The source of the article had to change all her credit card passwords, Facebook, Amazon and eBay accounts, almost 30 accounts in total.

The story: I work at Sony Pictures. This is what it was like after we got hacked.

Because of their size and income, companies are frequent targets for hackers. here is a list of 10 critical corporate cybersecurity risks, 13. the casual, public wi-fi hack.

Maurits Martijn, a Dutch journalist at De Correspondent, entered a busy Amsterdam café with Wouter Slotboom, an ethical hacker.

Within a few minutes, Slotboom had set up his gear, consisting of a laptop and a small black device and connected to the coffeehouses Wi-Fi.

All you needed was around $80-90 worth of software and equipment, an average intelligence and that was it, a few minutes was all it took to get a hold of a few dozen users personal information.

Slotboom’s small, black device could fool a phone into connecting to his own Wi-Fi network, giving him control over the entire traffic coming and going from a device.

If Slotboom wanted to, he could wait until one user wrote in his email address and password and then take it over.

With it, he could control most of the services registered on that email.

While you don’t need to be paranoid every time you connect to a public Wi-Fi, it’s best if you know the risks of doing so.

The story: Don’t use public Wi-Fi when reading this article.

There are ways in which you can stay safe on public hotspots: 11 security steps to stay safe on public wi-fi networks, 14. customer support falls prey to a social engineering hack.

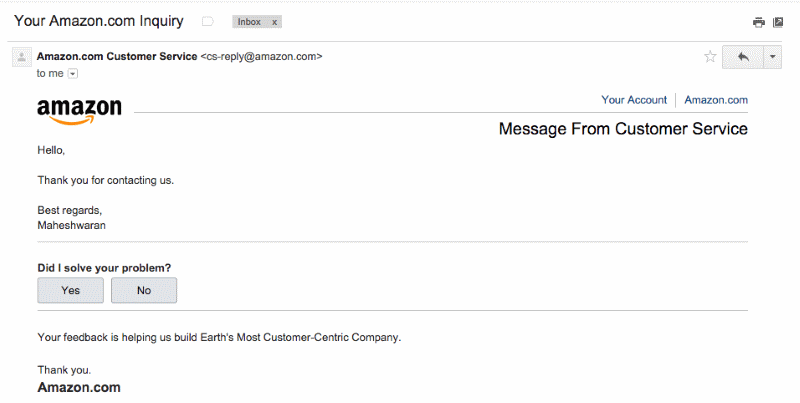

The impersonator then used Eric’s fake information in a conversation with an Amazon customer support representative and found out his real address and phone number.

Using Eric’s real information, the impersonator got in touch with various services and even managed to issue a new credit card in Eric’s name.

Eric got wind of his impersonator’s efforts by reading the customer support transcripts, and also found out his real purpose: to get the last 4 digits of his credit card.

Amazon didn’t do anything to protect Eric’s account, even though he repeatedly signaled the problem, so he finally decides to switch from Amazon to Google.

As a parting note, he gets an email from Amazon implying they have provided the impersonator with the last 4 digits of his credit card.

This story about this guy’s tumultuous experience with Amazon will make you think twice about storing confidential information in your online accounts.

The fact that Amazon failed to protect his account and look into the matter shows how a lack of cyber security education can endanger users

The story: Amazon’s customer service backdoor

Here is a guide on how to protect yourself against social engineering attacks, 15. hotel managers and clients had nightmares due to one lock hack.

In this Forbes story , reporters chronicles the chaos experienced by hotel managers and the panic felt by their customers after a burglar used online hacking tools to bypass the electronic locks on the doors.

He then used that Onity-lock hack to do a series of break-ins. How did this cautionary tale end?

On a bittersweet note.

The original burglar is serving a prison sentence, but the electronic locks in question can still be easily hacked.

A Wired reporter tried it himself, almost 6 years after the original Onity hack, and it still worked. He managed to break into a hotel room.

His story is amazing and it follows the birth of the original hacking method, how the burglar got to it and what came out of the entire publicized event.

The story: The Hotel Room Hacker

If you rely on electronic locks and other IoT devices to secure your belongings, this guide will be very useful: IOT SECURITY – All You Need To Know And Apply

16. the moderna conundrum.

According to Reuters and other major publications , Moderna Inc, one of the three biotech companies developing an efficient COVID-19 vaccine, has come under attack in late July. US’s Justice Department and the FBI have accused two Chinese nationals in this case.

They have been charged with spying on the American biotech company and three other targets in a bid to slow down or effectively stop the development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Source from inside the FBI has revealed that the two arrested Chinese citizens are part of a hacking group funded by the Chinese government.

The company has emerged unscathed from the incident. No data has left Moderna’s databanks and the network remains intact.

The story: China-backed hackers ‘targeted COVID-19 vaccine firm Moderna’

These stories may help you realize that not protecting your information and relying on other Internet users to be nice and play fair is not a viable strategy.

Cyber criminals don’t care about the consequences of their attacks.

They only want to reach their purpose, and sometimes that purpose may have nothing to do with you.

You could just be a collateral victim, but the aftermath would be all too real for you.

Ana Dascalescu

Cyber Security Enthusiast

The Atlantic wrote about cyberflâneur and I think that's the best way to describe myself. Or maybe a digital jack-of-all-trades with a long background in blogging, video production and streaming. I spend my waking hours snooping through online communities of all types, from Reddit to security forums, from gaming blogs to banal social media platforms like Instagram. Sometimes I even contribute to those communities.

Related Articles

CHECK OUR SUITE OF 11 CYBERSECURITY SOLUTIONS

- Cyber Resources And Beginners

- Cyber Security Glossary

- The Daily Security Tip

- Cyber Security For Small Business Owners

- Cybersecurity Webinars

- About Heimdal®

- Press Center

- Partner with us

- Affiliate Program

© 2024 Heimdal ®

Vat No. 35802495, Vester Farimagsgade 1, 2 Sal, 1606 København V

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

https://www.nist.gov/itl/smallbusinesscyber/cybersecurity-basics/case-study-series

Small Business Cybersecurity Corner

Small business cybersecurity case study series.

Ransomware, phishing, and ATM skimming are just a few very common and very damaging cybersecurity threats that Small Businesses need to watch out for. The following Case Studies were created by the National Cyber Security Alliance , with a grant from NIST, and should prove useful in stimulating ongoing learning for all business owners and their employees.

- Case 1: A Business Trip to South America Goes South Topic: ATM Skimming and Bank Fraud

- Case 2: A Construction Company Gets Hammered by a Keylogger Topic: Keylogging, Malware and Bank Fraud

- Case 3: Stolen Hospital Laptop Causes Heartburn Topic: Encryption and Business Security Standards

- Case 4: Hotel CEO Finds Unwanted Guests in Email Account Topic: Social Engineering and Phishing

- Case 5: A Dark Web of Issues for a Small Government Contractor Topic: Data Breach

Landmark Cyber Law cases in India

- Post author By ashwin

- Post date March 1, 2021

By:-Muskan Sharma

Introduction

Cyber Law, as the name suggests, deals with statutory provisions that regulate Cyberspace. With the advent of digitalization and AI (Artificial Intelligence), there is a significant rise in Cyber Crimes being registered. Around 44, 546 cases were registered under the Cyber Crime head in 2019 as compared to 27, 248 cases in 2018. Therefore, a spike of 63.5% was observed in Cyber Crimes [1] .

The legislative framework concerning Cyber Law in India comprises the Information Technology Act, 2000 (hereinafter referred to as the “ IT Act ”) and the Rules made thereunder. The IT Act is the parent legislation that provides for various forms of Cyber Crimes, punishments to be inflicted thereby, compliances for intermediaries, and so on.

Learn more about Cyber Laws Courses with Enhelion’s Online Law Course !

However, the IT Act is not exhaustive of the Cyber Law regime that exists in India. There are some judgments that have evolved the Cyber Law regime in India to a great extent. To fully understand the scope of the Cyber Law regime, it is pertinent to refer to the following landmark Cyber Law cases in India:

- Shreya Singhal v. UOI [2]

In the instant case, the validity of Section 66A of the IT Act was challenged before the Supreme Court.

Facts: Two women were arrested under Section 66A of the IT Act after they posted allegedly offensive and objectionable comments on Facebook concerning the complete shutdown of Mumbai after the demise of a political leader. Section 66A of the IT Act provides punishment if any person using a computer resource or communication, such information which is offensive, false, or causes annoyance, inconvenience, danger, insult, hatred, injury, or ill will.

The women, in response to the arrest, filed a petition challenging the constitutionality of Section 66A of the IT Act on the ground that it is violative of the freedom of speech and expression.

Decision: The Supreme Court based its decision on three concepts namely: discussion, advocacy, and incitement. It observed that mere discussion or even advocacy of a cause, no matter how unpopular, is at the heart of the freedom of speech and expression. It was found that Section 66A was capable of restricting all forms of communication and it contained no distinction between mere advocacy or discussion on a particular cause which is offensive to some and incitement by such words leading to a causal connection to public disorder, security, health, and so on.

Learn more about Cyber Laws with Enhelion’s Online Law firm certified Course!

In response to the question of whether Section 66A attempts to protect individuals from defamation, the Court said that Section 66A condemns offensive statements that may be annoying to an individual but not affecting his reputation.

However, the Court also noted that Section 66A of the IT Act is not violative of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution because there existed an intelligible difference between information communicated through the internet and through other forms of speech. Also, the Apex Court did not even address the challenge of procedural unreasonableness because it is unconstitutional on substantive grounds.

- Shamsher Singh Verma v. State of Haryana [3]

In this case, the accused preferred an appeal before the Supreme Court after the High Court rejected the application of the accused to exhibit the Compact Disc filed in defence and to get it proved from the Forensic Science Laboratory.

The Supreme Court held that a Compact Disc is also a document. It further observed that it is not necessary to obtain admission or denial concerning a document under Section 294 (1) of CrPC personally from the accused, the complainant, or the witness.

- Syed Asifuddin and Ors. v. State of Andhra Pradesh and Anr. [4]

Facts: The subscriber purchased a Reliance handset and Reliance mobile services together under the Dhirubhai Ambani Pioneer Scheme. The subscriber was attracted by better tariff plans of other service providers and hence, wanted to shift to other service providers. The petitioners (staff members of TATA Indicom) hacked the Electronic Serial Number (hereinafter referred to as “ESN”). The Mobile Identification Number (MIN) of Reliance handsets were irreversibly integrated with ESN, the reprogramming of ESN made the device would be validated by Petitioner’s service provider and not by Reliance Infocomm.

Questions before the Court: i) Whether a telephone handset is a “Computer” under Section 2(1)(i) of the IT Act?

- ii) Whether manipulation of ESN programmed into a mobile handset amounts to an alteration of source code under Section 65 of the IT Act?