- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2024

Evaluating competency-based medical education: a systematized review of current practices

- Nouf Sulaiman Alharbi 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 612 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

183 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Few published articles provide a comprehensive overview of the available evidence on the topic of evaluating competency-based medical education (CBME) curricula. The purpose of this review is therefore to synthesize the available evidence on the evaluation practices for competency-based curricula employed in schools and programs for undergraduate and postgraduate health professionals.

This systematized review was conducted following the systematic reviews approach with minor modifications to synthesize the findings of published studies that examined the evaluation of CBME undergraduate and postgraduate programs for health professionals.

Thirty-eight articles met the inclusion criteria and reported evaluation practices in CBME curricula from various countries and regions worldwide, such as Canada, China, Turkey, and West Africa. 57% of the evaluated programs were at the postgraduate level, and 71% were in the field of medicine. The results revealed variation in reporting evaluation practices, with numerous studies failing to clarify evaluations’ objectives, approaches, tools, and standards as well as how evaluations were reported and communicated. It was noted that questionnaires were the primary tool employed for evaluating programs, often combined with interviews or focus groups. Furthermore, the utilized evaluation standards considered the well-known competencies framework, specialized association guidelines, and accreditation criteria.

This review calls attention to the importance of ensuring that reports of evaluation experiences include certain essential elements of evaluation to better inform theory and practice.

Peer Review reports

Medical education worldwide is embracing the move toward outcome-based education (OBME) [ 1 , 2 ]. One of the most popular outcome-based approaches being widely adopted by medical schools worldwide is competency-based medical education (CBME) [ 3 ]. CBME considers competencies as the ultimate outcomes that should guide curriculum development at all steps or stages—that is, implementation, assessment, and evaluation [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. To embrace CBME and prepare medical students for practice, medical educators usually utilize an organized national or international competency framework that describes the abilities that physicians must possess to meet the needs of patients and society. There are numerous global competency frameworks that reflect the characteristics of a competent doctor, for example, CanMEDS, Scottish Doctor, Medical School Projects, ACGME Outcome Project, the Netherlands National Framework, and Saudi Meds [ 1 , 6 , 7 , 8 ].

With the worldwide implementation of CBME and availability of different competency frameworks, educators are expected to evaluate various modifications made to existing medical curricula [ 9 , 10 ]. Such evaluation is intended to explore whether the program is operating as planned and its outcomes are achieved as intended in comparison to predetermined standards as well as to ensure improvement [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Furthermore, program evaluation revolves around two main concepts, that is, merit and worth [ 12 , 14 ]. In 1981, Guba and Lincoln explained that the merits of a program are intrinsic, implicit, and independent and do not refer to a specific context or application, while evaluating a program’s worth entails judging the value of any aspect of it in reference to a certain context or precise application [ 12 , 14 ].

To enable educators to determine the merits and worth of an educational program or curriculum, evaluation experts have proposed several models [ 14 , 15 ]. Evaluation models are guiding frameworks that demonstrate what appropriate evaluation looks like and detail how it should be designed and implemented [ 16 ]. Although almost all evaluation models focus on exploring whether a program attains its objectives, they vary in numerous aspects, including their evaluation philosophy, approaches, and the specific areas that they encompass [ 17 ].

It is essential that educators choose a suitable evaluation model when they implement CBME, as the right model will enable them to pinpoint [ 15 , 18 , 19 ]. In other words, a program helps identify areas of success, challenges, and opportunities for improvement in CBME implementation, leading to a deeper comprehension of CBME strategies and their effectiveness. Moreover, implementing CBME demands significant efforts and a wide range of financial, human, time, and infrastructure resources [ 20 ]. Thus, ensuring that these efforts and resources are well utilized to enhance educational and healthcare outcomes is crucial. In addition, evaluation provides valuable evidence for accreditation, quality assurance, policies, and guidelines. Otherwise put, it supports informed decision-making on many levels [ 21 ]. On another front, sharing evaluation results and being transparent about evaluation processes can enhance public trust in available programs, colleges, and universities [ 19 ]. However, deciding which evaluation model to adopt can be challenging [ 9 ].

Not only can it be difficult to select an appropriate model to evaluate a CBME program, but CBME evaluation itself has numerous challenges, particularly given the lack of a common definition or standardized description of what constitutes a CBME program [ 9 , 22 , 23 ]. The complexity of CBME further tangles evaluation efforts, given the multilayered nature of CBME’s activities and outcomes and the need to engage a wide variety of stakeholders [ 11 ]. Moreover, the scarcity and variable quality of reporting in studies focusing on the evaluation of CBME curricula exacerbate these challenges [ 24 ]. Furthermore, few published articles provide a comprehensive overview of available evidence on the topic.

This review is therefore designed to synthesize the findings of published studies that have reported CBME evaluation practices in undergraduate and postgraduate medical schools and programs. Its objective is to explore which CBME program evaluation practices have been reported in the literature by inspecting which evaluation objectives, models, tools, and standards were described in the included studies. In addition, the review inspects the results of evaluations and how they were shared. Thus, the review will serve in supporting educators to make evidence-based decisions when designing a CBME program. In addition, it will provide a useful resource for educators to embrace what was done right, learn from what was done wrong, improve many current evaluation practices, and compare different CBME interventions across various contexts.

Following a preliminary search within relevant journals for publications addressing evaluation practices utilized to assess competency-based curricula in medical education, the researcher used the PEO (participant, educational aspect, and outcomes) model to set and formulate the search question [ 24 ] as follows: participants : healthcare professionals and healthcare profession students; educational aspect : CBME curricula; outcome : program evaluation practices.

Next, the researcher created a clear plan for the review protocol. This review is classified as a systematized review rather than a systematic review [ 25 ]. While it does not meet the criteria for a systematic review because it relies on a single researcher and does not evaluate the quality of the studies included, it adheres to most of the steps outlined in the “Systematic Reviews in Medical Education: A Practical Approach: AMEE guide 94” [ 26 ]. Moreover, the researcher met with a medical educator with a strong background in CBME, an expert in review methods, and a librarian who is an expert in available databases and provided guidance and support for navigating such databases. Feedback was obtained from all three and used to finalize the review protocol. The protocol was followed to ensure that the research progressed in a consistent and systematized manner.

For this review, full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals in English from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2022 were searched within the following electronic data bases: PubMed, ERIC, Education Source, and CINHAL. The following terms were utilized to conduct the search: (Competency Based Medical Education OR Outcome Based Medical Education) AND (Evaluation OR assessment) AND (Undergraduate OR Postgraduate) AND (Implementing OR Performance OR Framework OR Program* OR Project OR Curriculum OR Outcome) (Additional file 1 ).

The researcher included articles that were published in English and reported evaluation practices for CBME or OBME curricula whether for undergraduate or postgraduate healthcare professionals. The researcher did not consider research reviews, commentaries, perspective articles, conference proceedings, and graduate theses in this review. In addition, articles that addressed students’ assessments rather than program evaluation were not included. Furthermore, articles that focused on teaching a particular skill (e.g., communication skills) or specific educational strategies (e.g., the effectiveness of Problem Based Learning) were excluded from this review.

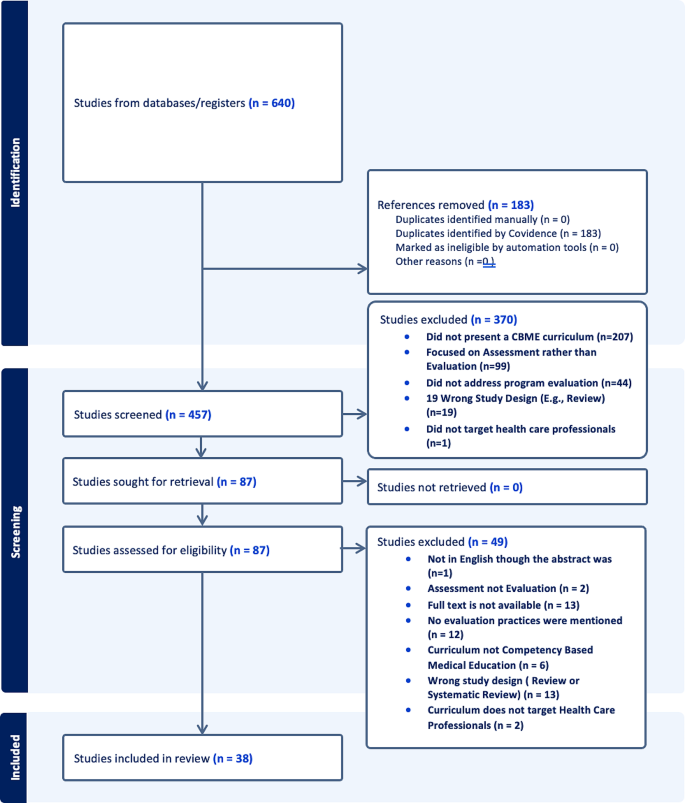

To facilitate the screening of articles and ensure the process was properly documented, an online review software that streamlines the production of reviews (Covidence) was utilized, and all the lists of articles retrieved from the specified databases were uploaded to the tool website (available at www.covidence.org ). The tool set the screening to start with the titles and abstracts then to proceed to full texts. During these stages, the reasons for excluding an article were precisely noted. Moreover, the PRISMA diagram (available at http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) was produced by Covidence to illustrate the process of screening and including articles in this review.

After the decision was made to include an article, a data extraction tool created for the purpose of this review was used (Additional file 2 ). Since the term “program evaluation practices” is general and does not clearly define the method or focus of the analysis involved in critiquing evaluation efforts, the analysis of available evaluation practices in this review was based on the Embedded Evaluation Model (EEM) provided by Giancola (2020) for educators to consider when embedding evaluations into educational program designs and development [ 27 ]. The EEM outlines several steps. In the first step, “Define,” educators are expected to build an understanding of the evaluated program, including its logic and context. In the second step, “Plan,” educators must establish the evaluation-specific objectives and questions and select the model or approach along with the methods or tools that will be utilized to achieve those objectives. The next step, “Implement and Analyze,” requires educators to determine how the data will be collected, analyzed, and managed. In the fourth step, “Interpret the Results,” educators are expected to derive insights from the results in terms of how the evaluation can help with resolving issues and improving the program as well as how the results should be communicated and employed. Finally, in the “Inform and Refine” step, educators should focus on applying the results to realize improvements to the program and promote accountability [ 27 ].

In addition to supporting the aim of the current review, the theoretical insights from Giancola (2020) help to ensure alignment with best practices in curriculum evaluation. Thus, for each article, the extraction tool collected the following information: the author, the publication year, the country and name of the institution that implemented the CBME curriculum, the aim and method of the article, the type of curriculum based on the health profession specialty (e.g., medicine, nursing), the level of the curriculum (postgraduate or undergraduate), the evaluation objective, the approach/model or tool, the evaluation standard, the evaluation results, and the sharing of the evaluation results. The extracted information points are essential to contextualize the evaluation and allow educators to make sense of it and adapt or adjust it to their own situations. Understanding the context of an evaluation is important considering the wide variety of available educational environments, the diversity of evaluators, and the differences in goals, modes, and benchmarks for evaluation, all of which influence how an evaluation is framed and conducted [ 27 ].

The author, publication year , and name and country of the institution that implemented the CBME curriculum provide identifiers for the original article and enable educators to seek further information about a study. The aim and method of the article were highlighted because they clarify the general context in which the evaluation was conducted. For example, this information can help educators understand whether an evaluation was carried out as a single action in response to a certain problem or was a phase or part of a larger project. The type of curriculum based on the health profession specialty (e.g., medicine, nursing) along with the level of the curriculum (postgraduate or undergraduate) have specific implications related to the nature of each specialty and the level of the competencies associated with the advancement of the program. All of the previously mentioned information is vital for educators to define and understand the program they are aiming to evaluate, which is the first step in the EEM. The evaluation objective , approach/model or tool , evaluation standard , evaluation results , and sharing of the evaluation results help to answer the research question of the current review by dissecting various aspects of the evaluation activities. In addition, the reporting of these aspects provides valuable insight into evaluation directives, plans, and execution. For educators, the evaluation objective usually clarifies the focus of the evaluation (e.g., how the program was implemented, the action done to execute education or outcomes of the program, and its effectiveness). The approach/model or tool of an evaluation is a core element of the design and implementation of the evaluation, as it determines the theoretical guidelines that underlie the evaluation and the practical steps for its execution. Based on the evaluation standard, which refers to the target used to compare the evidence or results of the evaluation, educators can judge the relevance of the evaluation to their own practices or activities. This information aligns with steps two and three of the EEM. The evaluation results are the results of the evaluation, which form the cornerstone for emerging solutions or future improvements. Finally, sharing the evaluation results , or communicating the evaluation, is a key part of handling the results and working toward their application. This information is aligned with steps four and five of the EEM.

Search results

Searching the identified databases revealed a total of 640 articles, and 183 total duplicates were removed. A total of 457 articles was considered for screening (371 PubMed, 13 ERIC, 23 Education Source, 50 CINHAL) (Fig. 1 ). Of those articles, 87 were retrieved for full-text screening. Ultimately, 38 studies met the inclusion criteria and were considered eligible to be included in the current review.

Flowchart illustrating the process of including articles in the review

Findings of the included studies

The 38 studies that met the inclusion criteria were published between 2010 and 2021, and the majority (15%; n = 6) were published in 2019. The studies represented the following countries: Canada (37%, n = 14) [ 10 , 11 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], USA (27.5%, n = 11) [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ], Australia (5%, n = 2) [ 51 , 52 ], China (5%, n = 2) [ 53 , 54 ], Dutch Caribbean islands (2.5%, n = 1) [ 55 ], Germany (2.5%, n = 1) [ 56 ], Guatemala (2.5%, n = 1) [ 57 ], Korea (2.5%, n = 1) [ 58 ], the Netherlands (2.5%, n = 1) [ 59 ], New Zealand (2.5%, n = 1) [ 60 ], The Republic of Haiti (2.5%, n = 1) [ 61 ], Turkey (2.5%, n = 1) [ 62 ], and the region of West Africa (2.5%, n = 1) [ 63 ].

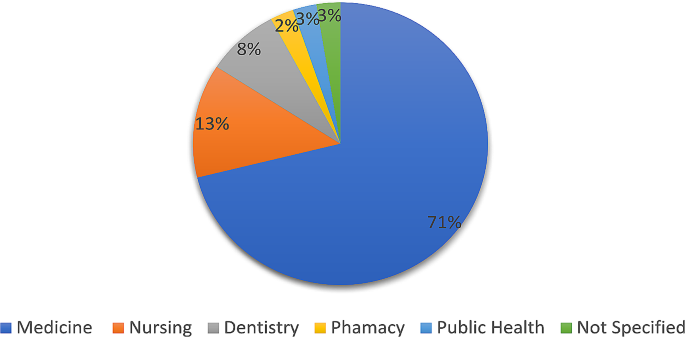

According to the evidence synthesized from the included studies, most of the evaluation practices were reported in competency-based curricula that targeted the level of postgraduate professionals (57%, n = 22) and were medical in nature (71%, n = 27) (Fig. 2 ).

Curricula specialties in included articles

The findings showed that 37% ( n = 14) of the articles did not report the precise objective of evaluating the curriculum. Moreover, 84% ( n = 32) did not report the evaluation approach or model used to assess the described curricula. The approaches or models reported include Pawson’s model of realist program evaluation [ 37 ], theory-based evaluation approaches [ 10 ], Stufflebeam’s context, inputs, processes, and products (CIPP) model [ 62 ], the concerns-based adoption model, sensemaking and outcome harvesting [ 33 ]the CIPP model [ 48 ], and quality improvement (QI) for program and process improvement [ 50 ]. On the other hand, a wide variety of evaluation tools was reported including observations (3%, n = 1) [ 28 ] surveys or questionnaires (58%, n = 22) [ 10 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 63 ] interviews (16%, n = 6) [ 10 , 28 , 37 , 41 , 47 , 62 ], focus groups (13%, n = 5) [ 35 , 37 , 41 , 50 , 59 ], historical document review or analysis (8%, n = 3) [ 10 , 29 , 33 ], educational activity assessment or analysis of the activity by separate reviewers (5%, n = 2) [ 55 , 61 ], stakeholder discussions or reports about their inputs (5%, n = 2) [ 43 , 44 ], curriculum mapping (3%, n = 1) [ 32 ], feedback from external reviews from accrediting bodies (3%, n = 1) [ 32 ], the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) (3%, n = 1) [ 56 ], and students’ or participants’ assessments (5%, n = 2) [ 38 , 46 ].

Of the studies, 37% ( n = 14) utilized multi methods [ 10 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 48 , 52 , 56 , 59 ]. Furthermore, 7.8% ( n = 3) of the studies reported the nature of the tool, for example, quantitative or qualitative, without specifying the exact tool utilized [ 57 , 60 ]. Moreover, 63% ( n = 24) of the studies included in this review did not report the evaluation standards applied while assessing the competency-based curricula addressed. Yet, those studies that reported their standards were stated in various ways as follows: some publications referred to the standards of specific specialized associations or societies, such as the American Academy of Family Physicians and College of Family Physicians Canada [ 61 ], Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [ 60 ], and The American Association of Occupational Health Nurses [ 45 ]. Other publications utilized known competency frameworks as their standards, such as CanMED [ 36 , 37 , 59 ], or the competencies of the American Board of Surgery [ 43 ] Association of Canadian Faculties of Dentistry [ 31 ], Royal College of Ophthalmologists [ 52 ], The Florida Consortium for Geriatric Medical Education [ 50 ], or the Dutch Advisory Board for Postgraduate Curriculum Development for Medical Specialists [ 59 ]. Furthermore, many of the publications referred to accreditation standards, such as the Accreditation Standards of the Australian Medical Council [ 51 ], Competencies of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [ 43 ], Accreditation Body in the Competency-based Curriculum [ 32 ], and the Commission on Dental Accreditation of Canada [ 31 ]. All the publications included in the review reported the results of their evaluations.

Finally, the results revealed that almost half (52.6%, n = 20) of the authors of the articles mentioned that they were publishing their experience with the intent of sharing lessons learned, yet they did not refer to any other means of sharing the results of their evaluations. In contrast, the other half did not mention any measures taken to communicate and share the evaluation results. Additional file 3 includes the characteristics and details of the data extracted from the studies included addressing evaluation practices in healthcare professionals’ education.

Evaluating a curriculum appropriately is important to ensure that the program is operating as intended [ 13 ]. The present study aimed to review the available literature on the evaluation practices of competency-based undergraduate and postgraduate health professionals’ schools and programs. This review inspected which evaluation objectives, models, tools, and standards were described as well as the results of evaluations and how the results were shared. The synthesized evidence indicates that most of the programs reporting evaluation practices were postgraduate-level medical programs. This focus on CMBE among postgraduate programs can be related to the fact that competency-based education is organized around the most critical competencies useful for health professionals after graduation. Thus, they are better judged at practice [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]. Moreover, although competency-based curricula were introduced to many health professions over 60 years ago, such as pharmacology and chiropractic therapy, within the medical field they have only evolved in the last decade [ 67 ].

Furthermore, the data revealed that there is a discrepancy in how evaluation practices were reported in the literature in terms of evaluation objectives, approaches/models, tools, standards, documenting of results, and communication plans. Each area will be further discussed in the following paragraphs considering the ten-task approach and embedded evaluation model [ 27 , 68 ]. Both guide evaluation as an important step in curriculum development in medical education, detail the evaluation process, and outline many important considerations from design to execution [ 27 , 68 ].

Evaluation is a crucial part of curriculum development, and it can serve many purposes, such as ensuring attaining educational objectives, identifying areas of improvement, improving decision-making, and assuring quality [ 13 , 27 ]. Consequently, when addressing evaluation, it is important for educators to start by explaining the logic of the curriculum by asking, for example, what the program’s outcomes are and whether it is designed for postgraduates or undergraduates [ 27 ]. Moreover, educators must be precise in setting evaluation objectives, which entails answering certain questions: who will use the evaluation data; how will the data be used at both the individual and program level; will the evaluation be summative or formative; and what evaluation questions must be answered [ 27 , 68 , 69 ] However, many of the studies included in this review did not clearly explain the context of the curricula or report the objectives of their evaluation endeavors; rather, they settled for clarifying the objectives of the study or of the publication itself. One reason for this is that evaluation and educational research have many similarities [ 13 ] Nevertheless, the distinction between the two should be clarified, as doing so will enable other medical educators to better understand and benefit from the evaluation experience shared. Moreover, since CBME outcomes are complicated and should be considered on many levels, evaluation plans should include a focus, level, and timeline. The focus of an evaluation can be educational, with outcomes relevant to learners, or clinical, with health outcomes relevant to patients. The level of an evaluation can be micro, meso, or macro, targeting an individual, a program, or a system, respectively. The timeline of an evaluation can investigate outcomes during the program, after the program (i.e., how well learners have put what they learned in a CBME program into practice), and in the long term (i.e., how well learners are doing as practicing physicians) [ 70 ].

Once the evaluation objectives are clearly identified and prioritized, it is logical to start considering the evaluation approach or model that is most appropriate to attain these objectives considering the available resources. In other words, evaluation design should be outlined [ 27 , 68 ]. The choice of an evaluation approach or model affects the accuracy of assessing certain tasks carried out by or to specific subjects in a particular setting [ 68 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 ] This accuracy is referred to as an evaluation’s internal validity. Yet, the external validity of an evaluation entails that the evaluation results are generalizable to other subjects and other settings [ 68 ]. Each model has its own strengths and weaknesses, which require careful examination when planning an evaluation [ 14 , 73 , 74 , 75 ]. Explaining and justifying why a particular evaluation approach was chosen for a specific curriculum can enrich the lessons learned from the evaluation and aid other educators. Furthermore, some of the available models were more utilized within various educational contexts than others [ 17 ] that calls for a continuous documentation of the evaluation approaches or models used to inform theory and practice. Considering the importance of reporting the approaches and models used, it is unfortunate that most of the publications did not indicate the approach/model they used for evaluation, which limits educators’ abilities to utilize the plans and build on their evidence.

Another critical task in the evaluation process is deciding on the measurement tool or instrument to be used. The tool choice will determine what data will be gathered and how they will be collected and analyzed [ 27 , 68 ]. Thus, the choice should consider the evaluation objective as well as the uses, strengths, and limitations of each tool. The evidence in this review indicates that questionnaires or surveys were the most utilized tools in evaluating competency-based curricula. This result can be attributed to the advantages of this method (for example, it is a convenient and economical tool that is easy to administer and analyze and can be utilized with many individuals) [ 27 , 68 ]. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that questionnaires and surveys usually target attitudes and perceptions, which usually entails only a surface-level evaluation, according to the Kirkpatrick model [ 76 ]. The results also showed that in around 50% of the mixed-methods evaluations, the questionnaires were combined with another tool, such as interviews or focus groups. Understandably, utilizing an additional tool aims to deepen the level of the evaluation focus to include learning, behaviors, or results [ 76 ].

The evaluation evidence must be compared with a standard or target for educators to judge the program and make decisions [ 12 ]. Standards can be implicit or explicit, but they usually provide an understanding of what is ideal [ 12 ]. Worryingly, the results of this review revealed that many of the included studies did not clarify the standards they used to judge different CBME curricula. However, the studies that reported their standards used accreditation criteria or broad competencies frameworks, such as CanMeds, which consider the guides of specialized associations, such as family physicians or nursing. Although deciding what standard to use can be challenging to those designing and evaluating programs, evaluating without an understanding of the level of quality desired can lead to many complications and a waste of resources.

Communicating and reporting evaluation results are crucial to attaining the evaluation objectives [ 27 , 68 , 75 ]. Moreover, effective communication strategies have many important functions, such as providing decision makers with the necessary data to make an informed decision. Informing other stakeholders about the results is also important to achieve their support in implementing program changes and nourish a culture of quality [ 77 , 78 ]. Around half of the authors of studies included in this review indicated that they were publishing to share their own evaluation experiences, while the other half did not. Regardless, none of the studies shared or indicated how their results were reported and communicated, which is an important part of the evaluation cycle that should not be overlooked when sharing evaluation lessons within the scientific community. Reporting the results also ensures quality transformation by closing the evaluation cycle and encourages future engagement in evaluation among different stakeholders [ 78 , 79 , 80 ]. Moreover, the results of the evaluation should be shared publicly to contribute to increasing public trust in educational programs and their outcomes [ 19 , 69 ].

In summary, this review of evaluation practices within competency-based curricula for undergraduate and postgraduate health professional programs provides valuable insight into the current landscape. The results of the review show that most evaluation practices published pertain to postgraduate medical programs. In addition, by examining the objectives, models, tools, standards, and communication of evaluation results, this study exposes a discrepancy between the reported evaluation practices and identified evaluation elements. This discrepancy extends to the data that are reported, which makes it even more difficult to synthesize a holistic picture and definitively fulfill the aim of the review. Moreover, the issue of missing information poses serious challenges for educators who try to leverage existing knowledge to inform their curriculum development and improvement efforts, and it highlights the need for a more systematic and transparent approach to evaluation within CBME.

This review illustrates the importance of agreeing on the main evaluation elements to be reported when publishing a CBME evaluation. Establishing a shared understanding of these fundamental elements will give educators a framework for enhancing the practical utility of evaluation methodologies. In addition, educators and practitioners can ensure that the evaluation process yields more insightful outcomes and is better tailored to meet the needs of the educational context.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Outcome-Based Medical Education

Competency-Based Medical Education

Embedded Evaluation Model

Zaini R, Bin Abdulrahman K, Alkhotani A, Al-Hayani AA, Al-Alwani A, Jastaniah S. Saudi meds: a competence specification for Saudi medical graduates. Med Teach. 2011;33(7):582–4.

Article Google Scholar

Davis MH, Amin Z, Grande JP, O’Neill AE, Pawlina W, Viggiano TR et al. Case studies in outcome-based education. Med Teach. 2009; 29(7):717–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701691429

Caccia N, Nakajima A, Kent N. Competency-based medical education: The wave of the future. JOGC. 2015; 37(4):349–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30286-3

Danilovich N, Kitto S, Price D, Campbell C, Hodgson A, Hendry P. Implementing competency-based medical education in family medicine: a narrative review of current trends in assessment. Fam Med. 2021;53:9–22.

Hawkins RE, Welcher CM, Holmboe ES, Kirk LM, Norcini JJ, Simons KB et al. Implementation of competency-based medical education: Are we addressing the concerns and challenges? Med Educ. 2015 Oct. 22; 49(11):1086–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12831

Simpson JG, Furnace J, Crosby J, Cumming AD, Evans PA, David MF, Ben et al. The Scottish doctor-learning outcomes for the medical undergraduate in Scotland: A foundation for competent and reflective practitioners. Med Teach. 2002; 24(2):136–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590220120713

Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007; 29(7):648–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701392903

Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: Implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007; 29(7):642–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701746983

van Melle E, Frank JR, Holmboe ES, Dagnone D, Stockley D, Sherbino J. A core components framework for evaluating implementation of competency-based medical education programs. Acad Med. 2019 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Mar 19]; 94(7):1002–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30973365/

Hamza DM, Ross S, Oandasan I. Process and outcome evaluation of a CBME intervention guided by program theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020; 26(4):1096–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13344

Van Melle E, Frank J, Holmboe E, Dagnone D, Stockley D, Sherbino J. A core components framework for evaluating implementation of competency-based medical education programs. Acad Med. 2019;94:1.

Google Scholar

Giancola SP. Program evaluation: Embedding evaluation into program design and development. SAGE Publications; 2020. https://books.google.com.sa/books?id=H-LFDwAAQBAJ

Morrison J, Evaluation. BMJ. 2003; 326(7385):385. http://www.bmj.com/content/326/7385/385.abstract

Glatthorn AA. Curriculum leadership: Strategies for development and implementation. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2016. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910219273702121

Stufflebeam D. Evaluation models. New Dir Eval. 2001; 2001(89):7–98.

Mertens D, Wilson A. Program evaluation theory and practice. 2nd ed. United States of America: The Guilford; 2019.

Nouraey P, Al-Badi A, Riasati M, Maata RL. Educational program and curriculum evaluation models: a mini systematic review of the recent trends. UJER. 2020;8:4048–55.

Sarah Schiekirka, Markus A, Feufel C, Herrmann-Lingen T, Raupach. Evaluation in medical education: a topical review of target parameters, data collection tools and confounding factors. Ger Med Sci. 2015; 13 (16).

Van Melle E, Hall A, Schumacher D, Kinnear B, Gruppen L, Thoma B, et al. Capturing outcomes of competency-based medical education: the call and the challenge. Med Teach. 2021;43:1–7.

Lomis KD, Mejicano GC, Caverzagie KJ, Monrad SU, Pusic M, Hauer KE. The critical role of infrastructure and organizational culture in implementing competency-based education and individualized pathways in undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2021; 43(sup2):S7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1924364

Taber S, Frank JR, Harris KA, Glasgow NJ, Iobst W, Talbot M. Identifying the policy implications of competency-based education. Med Teach. 2010; 32(8):687–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500706

Zaini RG, bin Abdulrahman KA, Al-Khotani AA, Al-Hayani AMA, Al-Alwan IA, Jastaniah SD. Saudi Meds: A competence specification for Saudi medical graduates. Med Teach. 2011 Jul [cited 2022 Mar 19]; 33(7):582–4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21696288/

Leung WC. Competency based medical training: review * Commentary: The baby is thrown out with the bathwater. BMJ. 2002 Sept 28; 325(7366):693–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.325.7366.693

Hall AK, Schumacher DJ, Thoma B, Caretta-Weyer H, Kinnear B, Gruppen L et al. Outcomes of competency-based medical education: A taxonomy for shared language. Med Teach. 2021;43(7):788–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1925643

Masoomi R. What is the best evidence medical education? Res Dev Med Educ. 2012;1:3–5.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009; 26(2):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Sharma R, Gordon M, Dharamsi S, Gibbs T. Systematic reviews in medical education: A practical approach: AMEE Guide 94. Med Teach. 2015; 37(2):108–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.970996

Giancola SP. Program evaluation embedding evaluation into program design and development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication Ltd.; 2020.

Acai A, Cupido N, Weavers A, Saperson K, Ladhani M, Cameron S et al. Competence committees: The steep climb from concept to implementation. Med Educ. 2021; 55(9):1067–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14585

Zhang P, Hamza D, Ross S, Oandasan I. Exploring change after implementation of family medicine residency curriculum reform. Fam Med. 2019;51:331–7.

Thoma B, Hall A, Clark K, Meshkat N, Cheung W, Desaulniers P et al. Evaluation of a national competency-based assessment system in emergency medicine: a CanDREAM Study. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(4).

Schönwetter D, Law D, Mazurat R, Sileikyte R, Nazarko O. Assessing graduating dental students’ competencies: the impact of classroom, clinic and externships learning experiences. Eur J Dent Educ. 2011;15:142–52.

Nousiainen M, Mironova P, Hynes M, Takahashi S, Reznick R, Kraemer W, et al. Eight-year outcomes of a competency-based residency training program in orthopedic surgery. Med Teach. 2018;40:1–13.

Railer J, Stockley D, Flynn L, Hastings Truelove A, Hussain A. Using outcome harvesting: assessing the efficacy of CBME implementation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020; 26(4).

Janssen P, Keen L, Soolsma J, Seymour L, Harris S, Klein M, et al. Perinatal nursing education for single-room maternity care: an evaluation of a competency-based model. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:95–101.

Goudreau J, Pepin J, Dubois S, Boyer L, Larue C, Legault A. A second generation of the competency-based approach to nursing education. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2009;6:Article15.

Fahim C, Bhandari M, Yang I, Sonnadara R. Development and early piloting of a CanMEDS competency-based feedback tool for surgical grand rounds. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(3):409–15.

Ellaway R, Mackay M, Lee S, Hofmeister M, Malin G, Archibald D, et al. The impact of a national competency-based medical education initiative in family medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93:1.

D’Souza L, Jaswal J, Chan F, Johnson M, Tay KY, Fung K et al. Evaluating the impact of an integrated multidisciplinary head & neck competency-based anatomy & radiology teaching approach in radiation oncology: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med Educ. 2014; 14(1):124. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-124

Crawford L, Cofie N, Mcewen L, Dagnone D, Taylor S. Perceptions and barriers to competency-based education in Canadian postgraduate medical education. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(4):1124–31.

Cox K, Smith A, Lichtveld M. A competency-based approach to expanding the cancer care workforce part III—Improving cancer pain and palliative care competency. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:507–14.

Freedman AM, Simmons S, Lloyd LM, Redd TR, Alperin MM, Salek SS et al. Public health training center evaluation: A framework for using logic models to improve practice and educate the public health workforce. Health Promot Pract. 2014; 15(1 Suppl):80S-8S. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24578370

Kerfoot B, Baker H, Volkan K, Church P, Federman D, Masser B, et al. Development and initial evaluation of a novel urology curriculum for medical students. J Urol. 2004;172:278–81.

Ketteler E, Auyang E, Beard K, McBride E, McKee R, Russell J, et al. Competency champions in the clinical competency committee: a successful strategy to implement milestone evaluations and competency coaching. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:36–8.

Lipp M. An objectified competency-based course in the management of malocclusion and skeletal problems. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:543–52.

Randolph S, Rogers B, Ostendorf J. Evaluation of an occupational health nursing program through competency achievement on-campus and distance education, 2005 and 2008. AAOHN J. 2011;59:387–99.

Stefanidis D, Acker C, Swiderski D, Heniford BT, Greene F. Challenges during the implementation of a laparoscopic skills curriculum in a busy general surgery residency program. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:4–7.

Stucke R, Sorensen M, Rosser A, Jung S. The surgical consult entrustable professional activity (EPA): defining competence as a basis for evaluation. Am J Surg. 2018;219(2):253–7.

Swider S, Levin P, Ailey S, Breakwell S, Cowell J, Mcnaughton D, et al. Matching a graduate curriculum in public/community health nursing to practice competencies: the Rush University experience. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:190–5.

Taleghani M, Solomon E, Wathen W. Non-graded clinical evaluation of dental students in a competency‐based education program. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:644–55.

Zuilen M, Mintzer M, Milanez M, Kaiser R, Rodriguez O, Paniagua M, et al. A competency-based medical student curriculum targeting key geriatric syndromes. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2008;28:29–45.

Gibson K, Boyle P, Black D, Bennett M, Grimm M, McNeil H. Enhancing evaluation in an undergraduate medical education program. Acad Med. 2008;83:787–93.

Succar T, McCluskey P, Grigg J. Enhancing medical student education by implementing a competency based ophthalmology curriculum. Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2017;6:42–6.

Gruber P, Gomersall C, Joynt G, Shields F, Chu CM, Derrick J. Teaching acute care: a course for undergraduates. Resuscitation. 2007;74:142–9.

Zhang H, Wang B, Zhang L. Reform of the method for evaluating the teaching of medical linguistics to medical students. Chinese Education & Society. 2014; 47(3):60–4. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932470305

Koeijers J, Busari J, Duits AJ. A case study of the implementation of a competency-based curriculum in a Caribbean teaching hospital. West Indian Med J. 2012;61:726–32.

Rotthoff T, Ostapczuk MS, de Bruin J, Kröncke KD, Decking U, Schneider M et al. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire to measure the perceived implementation of the mission statement of a competency based curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2012; 12(1):109. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-109

Day S, Garcia J, Antillon F, Wilimas J, Mckeon L, Carty R, et al. A sustainable model for pediatric oncology nursing education in low-income countries. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:163–6.

Lee BH, Chae YM, Hokama T, Kim S. Competency-based learning program in system analysis and design for health professionals. APJPH. 2010; 22(3):299–309. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26723774

Westein M, Vries H, Floor-Schreudering A, Koster A, Buurma H. Development of a postgraduate workplace-based curriculum for specialization of community pharmacists using CanMEDS competencies, entrustable professional activities and programmatic assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;83:ajpe6863.

de Beer W. Is the RANZCP CPD programme a competency-based educational programme? Australas Psychiatry. 2019; 27(4):404–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856219859279

Battat R, Jhonson M, Wiseblatt L, Renard C, Habib L, Normil M, et al. The Haiti Medical Education Project: Development and analysis of a competency based continuing medical education course in Haiti through distance learning. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:275.

İlhan E. Evaluation of competency based medical education curriculum. IJPE. 2021;17(3):153–68.

Ekenze SO, Ameh EA. Evaluation of relevance of the components of Pediatric Surgery residency training in West Africa. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45(4):801–5. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022346809008495

Iobst WF, Sherbino J, Cate O, Ten, Richardson DL, Dath D, Swing SR et al. Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2010; 32(8):651–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500709

Vakani F, Jafri W, Jafri F, Ahmad A. Towards a competency-based postgraduate medical education. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak; 22(7): 476–7.

Pascual TNB, Ros S, Engel-Hills P, Chhem RK. Medical competency in postgraduate medical training programs. Radiology Education. 2012; pp. 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27600-2_4

Frank J, Snell L, Ten Cate O, Holmboe E, Carraccio C, Swing S, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32:638–45.

Lindeman B, Kern D, Lipsett P. Step 6 evaluation and feedback. In: Thomas P, Kern D, Hughes M, Tackett S, Chen B, editors. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. 4th ed. Johns Hopkins University; 2022. pp. 142–97.

Morrison J. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Evaluation. BMJ. 2003; 326(7385):385–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.326.7385.385

Wang MC, Ellett CD. Program validation. Topics Early Child Spec Educ. 1982; 1(4):35–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112148200100408

McCray E, Lottes JJ. The validation of educational programs. 1976.

Toosi M, Modarres M, Amini M, Geranmayeh M. Evaluation model in medical education: A systematic review. 2016.

Balmer DF, Rama JA, Simpson D. Program evaluation models: Evaluating processes and outcomes in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2019; 11(1):99–100. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01084.1

Vassar M, Wheeler DL, Davison M, Franklin J. Program evaluation in medical education: An overview of the utilization-focused approach. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2010; 7:1. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2010.7.1

Kirkpatrick JD, Kirkpatrick WK. Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation. Association for Talent Development; 2016. (BusinessPro collection). https://books.google.com.sa/books?id=mo--DAAAQBAJ

Moreau KA, Eady K. Program evaluation use in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2023; 15(1):15–8. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00397.1

Durning SJ, Hanson J, Gilliland W, McManigle JM, Waechter D, Pangaro LN. Using qualitative data from a program director’s evaluation form as an outcome measurement for medical school. Mil Med. 2010; 175(6):448–52. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-09-00044

Kek M, Hunt L, Sankey M. Closing the loop: A case study of a post-evaluation strategy. 1998.

Wolfhagen HAP, Gijselaers WH, Dolmans D, Essed G, Schmidt HG. Improving clinical education through evaluation. Med Teach. 2009; 19(2):99–103. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421599709019360

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the support that Prof. Ahmad Alrumayyan and Dr. Emad Masuadi gave this research by reviewing its protocol and providing general feedback. In addition, the author would like to acknowledge Dr. Noof Albaz for the discussions about educational program evaluation, which contributed to improving the final version of this manuscript. Thanks, are also due to Mr. Mohammad Alsawadi for reviewing the utilized search terminologies and participating in the selection of appropriate databases and searching them to obtain the needed lists of articles.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Nouf Sulaiman Alharbi

King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Ministry of the National Guard - Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author takes full responsibility for study conception, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nouf Sulaiman Alharbi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical clearance for conducting this review was attained from King Abdullah International Research Center (KAIMRC), King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (RYD-22-419812-52334).

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, supplementary material 3, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alharbi, N.S. Evaluating competency-based medical education: a systematized review of current practices. BMC Med Educ 24 , 612 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05609-6

Download citation

Received : 13 November 2023

Accepted : 27 May 2024

Published : 03 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05609-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Competency-based medical education

- Program evaluation

- Undergraduate medical education

- Postgraduate medical education

- Curriculum development

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

Heuristic evaluation: Definition, case study, template

Imagine yourself faced with the challenge of assembling a tricky puzzle but not knowing where to start. Elements such as logical reasoning and meticulous attention to detail become essential, requiring an approach that goes beyond the surface level to achieve effectiveness. When evaluating the user experience of an interface, it is no different.

In this article, we will cover the fundamental concepts of heuristic evaluation, how to properly perform a heuristic evaluation, and the positive effects it can bring to your UX design process. Let’s learn how you can solve challenges with heuristic evaluation.

What is heuristic evaluation?

The heuristic evaluation principles, understanding nielsen’s 10 usability heuristics, essential steps in heuristic evaluation, prioritization criteria in the analysis of usability problems, communicating heuristic evaluation results effectively, dropbox’s heuristic evaluation approach, incorporating heuristic evaluation into the ux process.

The heuristic evaluation method’s main goal is to evaluate the usability quality of an interface based on a set of principles, based on UX best practices. From the identification of the problems, it is possible to provide practical recommendations and consequently improve the user experience.

So where did heuristic evaluation come from, and how do we use these principles? Read on.

Heuristic evaluation was created by Jakob Nielsen, recognized worldwide for his significant contributions to the field of UX. The method created by Nielsen is based on a set of heuristics from human-computer interaction (HCI) and psychology to inspect the usability of user interfaces.

Therefore, Nielsen’s 10 usability heuristics make up the principles of heuristic evaluation by establishing carefully established foundations. These foundations serve as a practical guide to cover the main usability problems of projects. These heuristics work as cognitive shortcuts used by the brain for efficient decision making, especially in redesign projects. Heuristics also help to complement the UX process when understanding user problems and supporting UX research and evaluation.

When you are getting ready to conduct a heuristic evaluation, the first step is to set clear goals. Then, during the evaluation, you should make notes on what you find considering usability issues, always based on the criteria. Once this is done, you can prepare a report that might include information on which issues to tackle first, which makes the evaluation even better. All these steps matter because they help make sure interfaces match what users want and expect, leading to better interactions overall.

Preparation for the heuristic evaluation: Defining usability objectives and criteria

As with the puzzle example in the intro, fully understanding the problem is critical to applying heuristic evaluation effectively. Thus, during the preparation phase, you need to establish the evaluation criteria, also defining how these criteria will be evaluated.

Select evaluators based on their experience. By involving a diverse set of evaluators, you can obtain different perspectives on the same challenge. Although an expert is able to point out most of the problems in a heuristic evaluation, collaboration is essential to generate more comprehensive recommendations.

Although it follows a set of heuristics, the evaluation is less formal and less expensive than a user test, making it faster and easier to conduct. Therefore, heuristic evaluation can be performed in the early stages of design and development when making changes is more cost effective.

Nielsen’s usability heuristics are like a tactical set for methodically making things work, providing valuable clues that designers and creators follow to piece together the usability puzzle. These heuristics act as master guides, helping us intelligently fit each piece of the puzzle together so that everything makes sense and is easy to understand to create amazing experiences in the products and websites we use.

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

Here are Nielsen’s 10 usability heuristics, each with its own relevance and purpose:

1. System status visibility

Continuously inform the user about what is happening.

2. Correspondence between the system and the real world

Use words and concepts familiar to the user.

3. User control and freedom

Allow users to undo actions and explore the system without fear of making mistakes.

4. Consistency and standards

Maintain a consistent design throughout the system, so users can apply what they learned in one part to the rest.

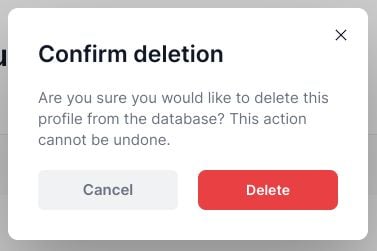

5. Error prevention

Design in a manner that prevents users from committing mistakes or provides means to easily correct wrong decisions.

6. Recognition instead of memorization

Provide contextual hints and tips to help users accomplish tasks without needing to remember specific information.

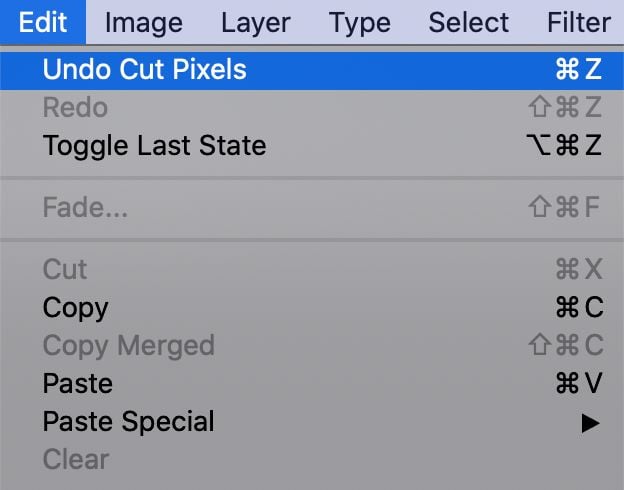

7. Flexibility and efficiency of use

Allow users to customize keyboard shortcuts or create custom profiles to streamline their interactions.

8. Aesthetics and minimalist design

Keep the design clean and simple, focusing on the most relevant information to avoid overwhelming users using proper spacing, colors, and typography.

9. Help and documentation

Provide helpful and accessible support in case users need extra guidance.

10. User feedback

Give immediate feedback to users when they take an action.

Together, these pieces of the usability heuristics puzzle help us build a complete picture of digital experiences. Thus, by following these guidelines, evaluators can identify problems and prioritize them for correction at the evaluation stage.

In the evaluation phase, evaluators should look at the product or system interface and document any usability issues based on heuristics. By using heuristics consistently across different parts of the interface, it is still possible to balance conflicting heuristics to find optimal design solutions.

There may be challenges during the evaluation phase, which is why it is important that evaluators suggest strategies to overcome them from the definition of priorities. Evaluators should therefore, in consensus, discuss how these heuristics can be applied to identify and address usability problems.

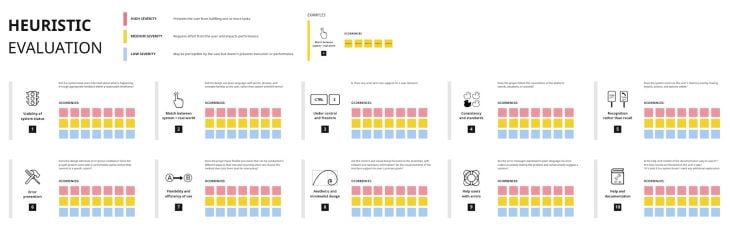

One of the interesting ways to do heuristic evaluation is through real-time collaboration tools like Miro. On the template below, you will be able to collaborate in real-time to conduct heuristic evaluations of your project with your team, evaluating the problems by criteria and dividing them by colors, based on the level of complexity to be solved.

You can download the Miro Heuristic Evaluation template for free .

After performing a heuristic assessment, evaluators should analyze the findings and prioritize usability issues, trying to identify the underlying causes of usability issues rather than just addressing surface symptoms.

Usability issues discovered during the assessment can be given severity ratings to prioritize fixes.

Below is an example of categorization by severity according to the challenge presented:

- High severity : Prevents the user from performing one or more tasks

- Medium severity : Requires user effort and affects performance

- Low severity : May be noticeable to the user but does not impede execution or performance

The classification will help the team to have greater clarity regarding what is most relevant to be faced considering the impact on the user experience. By prioritizing the most critical issues based on their impact on the user experience, it will be easier to effectively allocate them throughout the project.

Finally, during the reporting phase, evaluators should present their findings and recommendations to stakeholders and facilitate discussions on identified issues.

Evaluators typically conduct multiple iterations of the assessment to uncover different issues in subsequent rounds based on the need for the project and the issues identified.

Heuristic evaluation provides qualitative data, making it important to interpret the results with a deeper understanding of user behavior. When reporting and communicating the results of a heuristic assessment, assessors should follow best practices by presenting findings in visual representations that are easy to read and understand, and that highlight key findings, whether using interactive boards, tables or other visuals.

Problem descriptions should be clear and concise so they can be actionable. Instead of generating generic problems, for example, break the problems into distinct parts to be easier to deal with. If necessary, try to analyze the interface component and its details, thinking not only analytically in an abstract way but also understanding that that problem will be solved by a UX Designer, considering all its elements. In this scenario, a well-applied context makes all the difference.

It is also important to involve stakeholders and facilitate discussions around identified issues. As a popular saying goes: a problem communicated is a problem half solved.

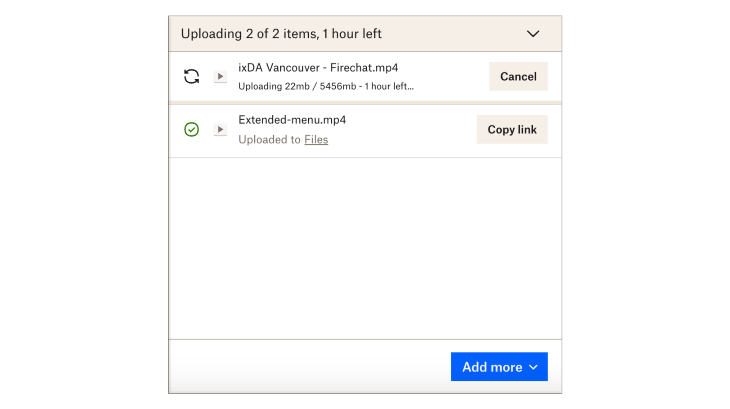

The Dropbox team really nails it when it comes to giving users a smooth and user friendly experience. Let’s dive into a few ways they have put these heuristic evaluation principles to work in their platform:

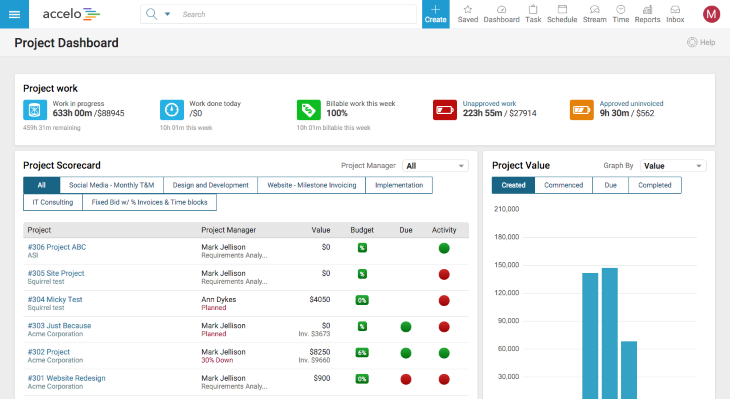

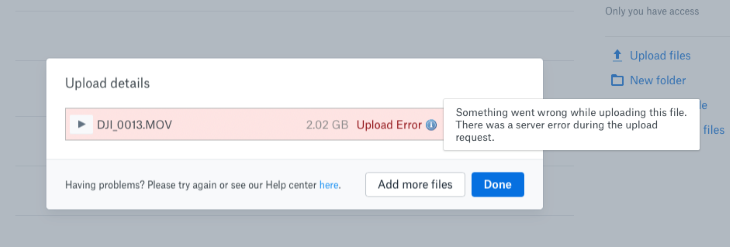

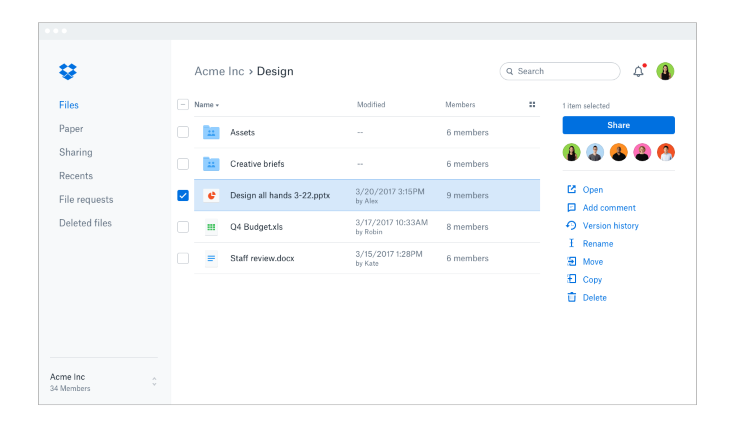

Dropbox keeps things clear by using concise labels to show the status of your uploaded files. They also incorporate a convenient progress bar that provides a time estimate for the completion of the upload. This real-time feedback keeps you informed about the ongoing status of your uploads on the platform:

The ease of moving, deleting, and renaming files between different folders and sharing with other people means that Dropbox offers users control over fundamental actions, allowing them to work in a personalized way, increasing their sense of ownership:

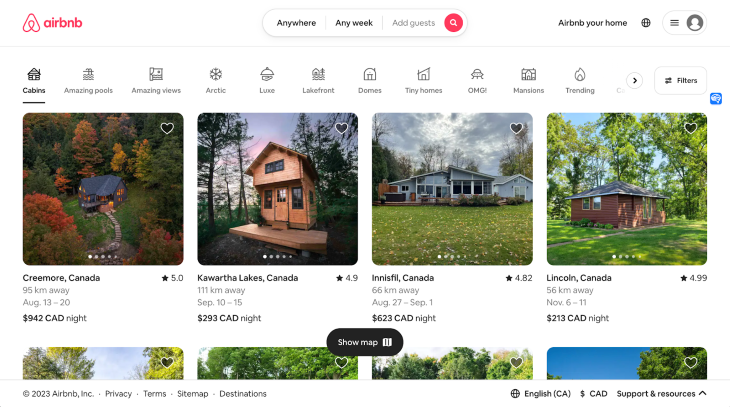

Making it a breeze for users to navigate no matter if they’re on a computer or a mobile device, Dropbox keeps things consistent in both: website and mobile app design:

To prevent errors from happening, Dropbox has implemented an interesting feature. If a user attempts to upload a file that’s too large, Dropbox triggers an error message. This message is quite helpful, as it guides the user to select a smaller file and clearly explains the issue. It’s a nifty feature that ensures users know exactly which steps to take next:

Dropbox cleverly employs affordances to ensure that users can easily figure out how to navigate the app. Take, for instance, the blue button located at the top of the screen — it’s your go-to for creating new files and folders. This is a familiar and intuitive pattern that users can quickly grasp:

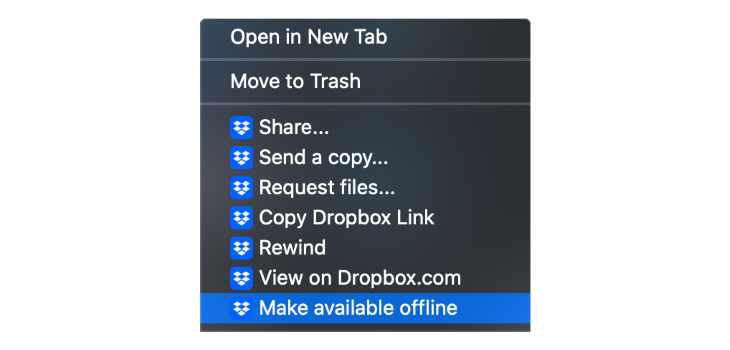

Consider now flexibility and efficiency. On Dropbox, the user can access their files from any gadget, and they can keep working even when they are offline without worrying about losing anything. It makes staying productive a breeze, no matter where the users finds themselves:

Dropbox has a clean and minimalist design that’s a breeze to use and get around in. Plus, it’s available in different languages, ensuring accessibility for people all around the world:

Dropbox goes the extra mile by using additional methods alongside heuristic evaluation, demonstrating a high positive impact on their services. All this dedication to applying the best heuristics on their products has made Dropbox one of the most popular storage services globally.

Heuristic evaluation fits into the broader UX design process and can be conducted iteratively throughout the design lifecycle, despite being commonly used early in the design process.

It provides valuable insights to inform design decisions and improvements and enables UX designers to effectively identify and address usability issues.

Conclusion and key takeaways

In this article, we have seen that heuristic evaluation is a systematic and valuable approach to identifying usability problems in systems and products. Through the use of general usability guidelines, it is possible to highlight gaps in the user experience, addressing areas such as clarity, consistency and control. This evaluation is conducted by a multidisciplinary team, and the problems identified are recorded in detail, allowing for further prioritization and refinement.

Much like a complex puzzle, improving usability and user experience requires identifying patterns and providing instructive feedback when working collaboratively.

Checking interfaces using heuristic evaluation can uncover many issues, but it’s not a replacement for what you learn from watching actual users. Think of it as an extra tool to understand users better.

Remember that heuristic evaluation not only reveals challenges but also empowers you as a UX professional to create more intuitive and impactful solutions.

When you mix in heuristic evaluation while making your designs, you can end up with products and systems that are more helpful and user-friendly without spending too much. This helps make your products or services even better by following good user experience tips.

So don’t hesitate: make the most of the potential of heuristic evaluation to push usability to the next level in your UX project.

LogRocket : Analytics that give you UX insights without the need for interviews

LogRocket lets you replay users' product experiences to visualize struggle, see issues affecting adoption, and combine qualitative and quantitative data so you can create amazing digital experiences.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today .

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- #ux research

Stop guessing about your digital experience with LogRocket

Recent posts:.

The essential principles of a good homepage

To ensure your homepage effectively captivates visitors and drives desired actions, you should follow these fundamental principles.

How to measure and improve user retention

Tracking metrics like user retention provides a way to measure the impact of your work on the growth and success of digital products.

A guide to data visualization

When creating data visualizations, you want to ensure clarity and accessibility — bonus points if the format allows for interactivity too.

I did a designathon as an experienced designer — here’s what I learned

Designathons bring design professionals from all levels and backgrounds gather — sometimes with guests such as project managers, developers, or researchers.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Master's programmes in English

- For exchange students

- PhD opportunities

- All programmes of study

- Language requirements

- Application process

- Academic calendar

- NTNU research

- Research excellence

- Strategic research areas

- Innovation resources

- Student in Trondheim

- Student in Gjøvik

- Student in Ålesund

- For researchers

- Life and housing

- Faculties and departments

- International researcher support

Språkvelger

Course - assessment and evaluation in education: policy, research, and practice - los8032, course-details-portlet, los8032 - assessment and evaluation in education: policy, research, and practice.

Lessons are not given in the academic year 2024/2025

Course content

Assessment and evaluation are key processes in education, spanning from teachers’ day-to-day observations in the classroom to international evaluations of policy initiatives and student learning outcomes. Research on assessment and evaluation therefore typically comprises both classroom practices and large-scale studies. Research-based knowledge is also used for policymaking purposes, to identify gaps in existing knowledge, and to improve practice in schools. This PhD course provides an introduction to key concepts and case studies in research on educational assessment and evaluation. The course gives an overview of these interconnected issues through engaging with concepts such as feedback, formative and summative assessments, classroom based vs. standardized assessment, data use in education, policy implementation and evaluation, and teachers' assessment literacy. The interplay between policy, research, and practice will be given special attention.

Learning outcome

Students will

- use theoretical lenses to analyze and evaluate assessment practices and policy initiatives, curriculum goals and learning outcomes, and the consequences of educational reforms

- be familiar with key concepts and issues in assessment and evaluation research, such as validity and reliability, accountability, and psychometric tests vs. classroom assessment

- understand how research-based knowledge can be used to improve practice in schools and across systems

- be familiar with a range of research strategies useful for assessment and evaluation in research, policy development, and practice

- collaborate with others on critiquing research, policy, and practices from various theoretical positions

Generic competencies

- write analyses of both policy and research documents

- collaborate with practitioners and policy makers to improve education

- combine knowledge from various fields to understand how systems can be improved through data use and evaluation

Learning methods and activities

The course will combine lectures, analysis of selected studies in groups, and individual writing tasks. In our seminars, we will use triangular discussions, an innovative approach to group work in which participants analyze examples from the three perspectives of policy, research, and practice. This approach will allow participants to understand the knowledge needs, epistemological stances, and possible biases of various actors and stakeholders in the field of education. By examining policies and research contributions from the perspectives of both policymakers, practitioners and researchers, participants will gain insight into how research-based knowledge is generated and used in various ways for assessment and evaluation purposes. Furthermore, development of participants' academic writing through shared writing and peer response seminars will be emphasized. If the course have English students, the teaching will be in English. Assignments can be handed in in Norwegian or English.

Compulsory assignments

- 80 % attendance

Further on evaluation

Individual paper.

Text submitted for assessment in the required academic coursework may be included in the thesis in revised form .

For a retake of a failed exam, the candidate can submit a revised version of a previously submitted text in the course. If the submission is a revised version of a previously submitted text, this must be clarified in the text.

Specific conditions

Limited admission to classes. For more information: https://i.ntnu.no/wiki/-/wiki/English/Admission+to+courses+with+restricted+admission

Required previous knowledge

Master's degree in education or similar research area. Admission restrictions*: The course is limited to a of maximum 25 students, where 6 spots are reserved for applicants from other institutions affiliated with NorTED (www.nor-ted.com). If there are less than 5 applicants, the Department of Teacher Education reserves the right to cancel the course. * Applicants will be ranked based on the following criteria and deadline for applications can be found here: https://www.ntnu.no/ilu/phd-emner

- Lecturers page

Version: 1 Credits: 5.0 SP Study level: Doctoral degree level

Language of instruction: English, Norwegian

Location: Trondheim

- Teacher Education

Department with academic responsibility Department of Teacher Education

Examination

- * The location (room) for a written examination is published 3 days before examination date. If more than one room is listed, you will find your room at Studentweb.

For more information regarding registration for examination and examination procedures, see "Innsida - Exams"

More on examinations at NTNU

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

research@BSPH

The School’s research endeavors aim to improve the public’s health in the U.S. and throughout the world.

- Funding Opportunities and Support

- Faculty Innovation Award Winners

Conducting Research That Addresses Public Health Issues Worldwide

Systematic and rigorous inquiry allows us to discover the fundamental mechanisms and causes of disease and disparities. At our Office of Research ( research@BSPH), we translate that knowledge to develop, evaluate, and disseminate treatment and prevention strategies and inform public health practice. Research along this entire spectrum represents a fundamental mission of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

From laboratories at Baltimore’s Wolfe Street building, to Bangladesh maternity wards in densely packed neighborhoods, to field studies in rural Botswana, Bloomberg School faculty lead research that directly addresses the most critical public health issues worldwide. Research spans from molecules to societies and relies on methodologies as diverse as bench science and epidemiology. That research is translated into impact, from discovering ways to eliminate malaria, increase healthy behavior, reduce the toll of chronic disease, improve the health of mothers and infants, or change the biology of aging.

120+ countries

engaged in research activity by BSPH faculty and teams.

of all federal grants and contracts awarded to schools of public health are awarded to BSPH.

citations on publications where BSPH was listed in the authors' affiliation in 2019-2023.

publications where BSPH was listed in the authors' affiliation in 2019-2023.

Departments

Our 10 departments offer faculty and students the flexibility to focus on a variety of public health disciplines

Centers and Institutes Directory

Our 80+ Centers and Institutes provide a unique combination of breadth and depth, and rich opportunities for collaboration

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversees two IRBs registered with the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections, IRB X and IRB FC, which meet weekly to review human subjects research applications for Bloomberg School faculty and students

Generosity helps our community think outside the traditional boundaries of public health, working across disciplines and industries, to translate research into innovative health interventions and practices

Introducing the research@BSPH Ecosystem

The research@BSPH ecosystem aims to foster an interdependent sense of community among faculty researchers, their research teams, administration, and staff that leverages knowledge and develops shared responses to challenges. The ultimate goal is to work collectively to reduce administrative and bureaucratic barriers related to conducting experiments, recruiting participants, analyzing data, hiring staff, and more, so that faculty can focus on their core academic pursuits.

Research at the Bloomberg School is a team sport.

In order to provide extensive guidance, infrastructure, and support in pursuit of its research mission, research@BSPH employs three core areas: strategy and development, implementation and impact, and integrity and oversight. Our exceptional research teams comprised of faculty, postdoctoral fellows, students, and committed staff are united in our collaborative, collegial, and entrepreneurial approach to problem solving. T he Bloomberg School ensures that our research is accomplished according to the highest ethical standards and complies with all regulatory requirements. In addition to our institutional review board (IRB) which provides oversight for human subjects research, basic science studies employee techniques to ensure the reproducibility of research.

Research@BSPH in the News

Four bloomberg school faculty elected to national academy of medicine.

Considered one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine, NAM membership recognizes outstanding professional achievements and commitment to service.

The Maryland Maternal Health Innovation Program Grant Renewed with Johns Hopkins

Lerner center for public health advocacy announces inaugural sommer klag advocacy impact award winners.

Bloomberg School faculty Nadia Akseer and Cass Crifasi selected winners at Advocacy Impact Awards Pitch Competition

- Refer A Friend

- Accreditation

- Testimonials

- Resource Center

- NP Continuing Education

- Case Study Approach To Asthma Management: Focus On Pharmacology And Guidelines

Case Study Approach to Asthma Management: Focus on Pharmacology and Guidelines

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1 introduction, 2 case study: shunde polytechnic, 3 methodology, 4 results and discussion, 5 conclusions, acknowledgements, author contributions.

- < Previous

Study on the effects of low-carbon education on the carbon emissions of college students: a case study in Guangdong Province

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Zhang Junting, Lyu Shun, Chen Zefeng, Study on the effects of low-carbon education on the carbon emissions of college students: a case study in Guangdong Province, International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies , Volume 19, 2024, Pages 1425–1431, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlct/ctae097

- Permissions Icon Permissions