Theoretical vs Conceptual Framework

What they are & how they’re different (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, sooner or later you’re bound to run into the terms theoretical framework and conceptual framework . These are closely related but distinctly different things (despite some people using them interchangeably) and it’s important to understand what each means. In this post, we’ll unpack both theoretical and conceptual frameworks in plain language along with practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Theoretical vs Conceptual

What is a theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, what is a conceptual framework, example of a conceptual framework.

- Theoretical vs conceptual: which one should I use?

A theoretical framework (also sometimes referred to as a foundation of theory) is essentially a set of concepts, definitions, and propositions that together form a structured, comprehensive view of a specific phenomenon.

In other words, a theoretical framework is a collection of existing theories, models and frameworks that provides a foundation of core knowledge – a “lay of the land”, so to speak, from which you can build a research study. For this reason, it’s usually presented fairly early within the literature review section of a dissertation, thesis or research paper .

Let’s look at an example to make the theoretical framework a little more tangible.

If your research aims involve understanding what factors contributed toward people trusting investment brokers, you’d need to first lay down some theory so that it’s crystal clear what exactly you mean by this. For example, you would need to define what you mean by “trust”, as there are many potential definitions of this concept. The same would be true for any other constructs or variables of interest.

You’d also need to identify what existing theories have to say in relation to your research aim. In this case, you could discuss some of the key literature in relation to organisational trust. A quick search on Google Scholar using some well-considered keywords generally provides a good starting point.

Typically, you’ll present your theoretical framework in written form , although sometimes it will make sense to utilise some visuals to show how different theories relate to each other. Your theoretical framework may revolve around just one major theory , or it could comprise a collection of different interrelated theories and models. In some cases, there will be a lot to cover and in some cases, not. Regardless of size, the theoretical framework is a critical ingredient in any study.

Simply put, the theoretical framework is the core foundation of theory that you’ll build your research upon. As we’ve mentioned many times on the blog, good research is developed by standing on the shoulders of giants . It’s extremely unlikely that your research topic will be completely novel and that there’ll be absolutely no existing theory that relates to it. If that’s the case, the most likely explanation is that you just haven’t reviewed enough literature yet! So, make sure that you take the time to review and digest the seminal sources.

Need a helping hand?

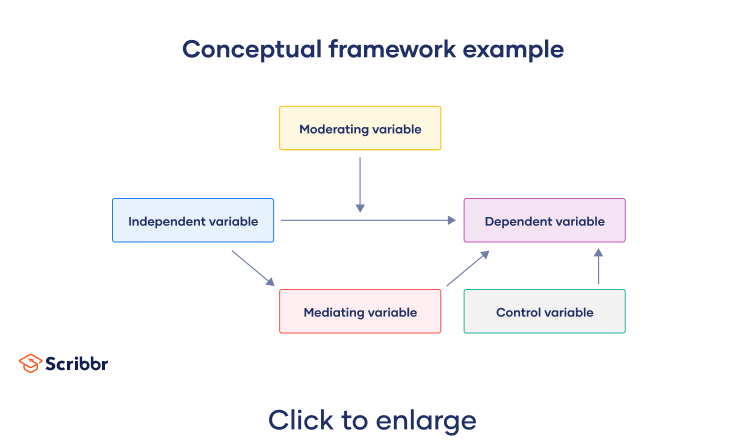

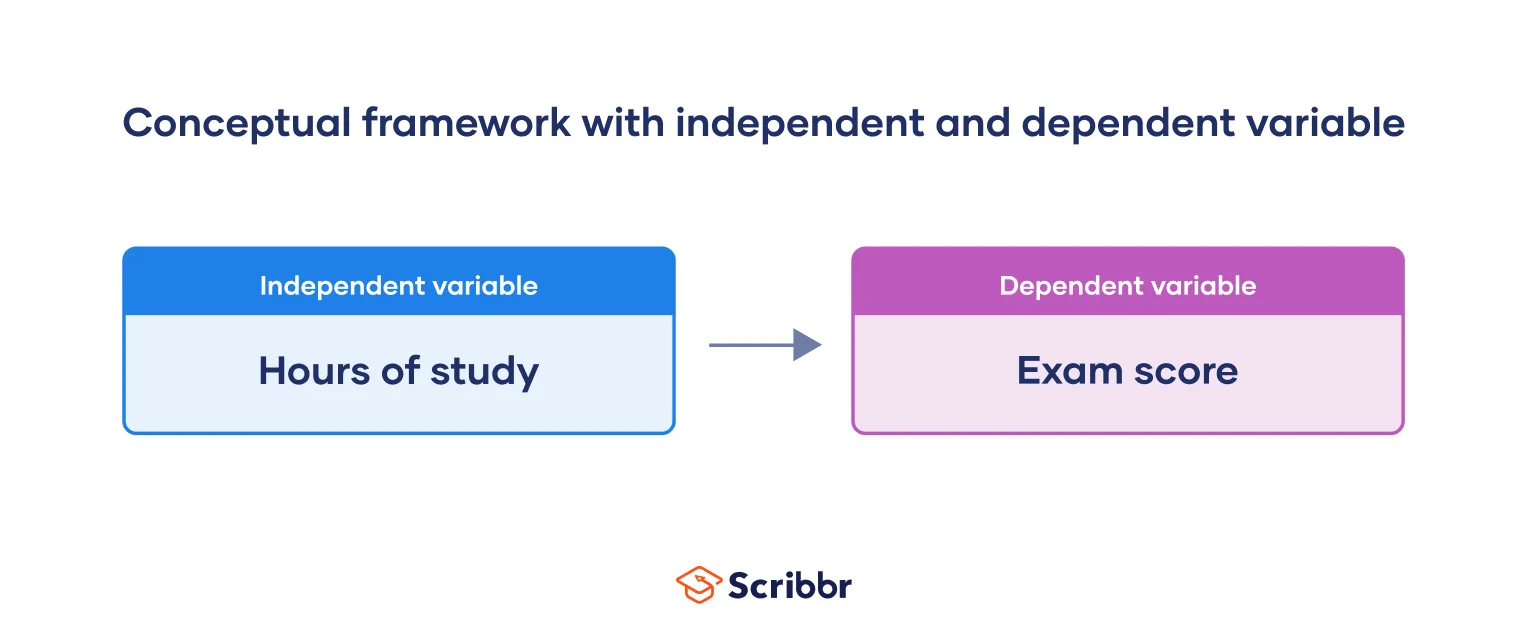

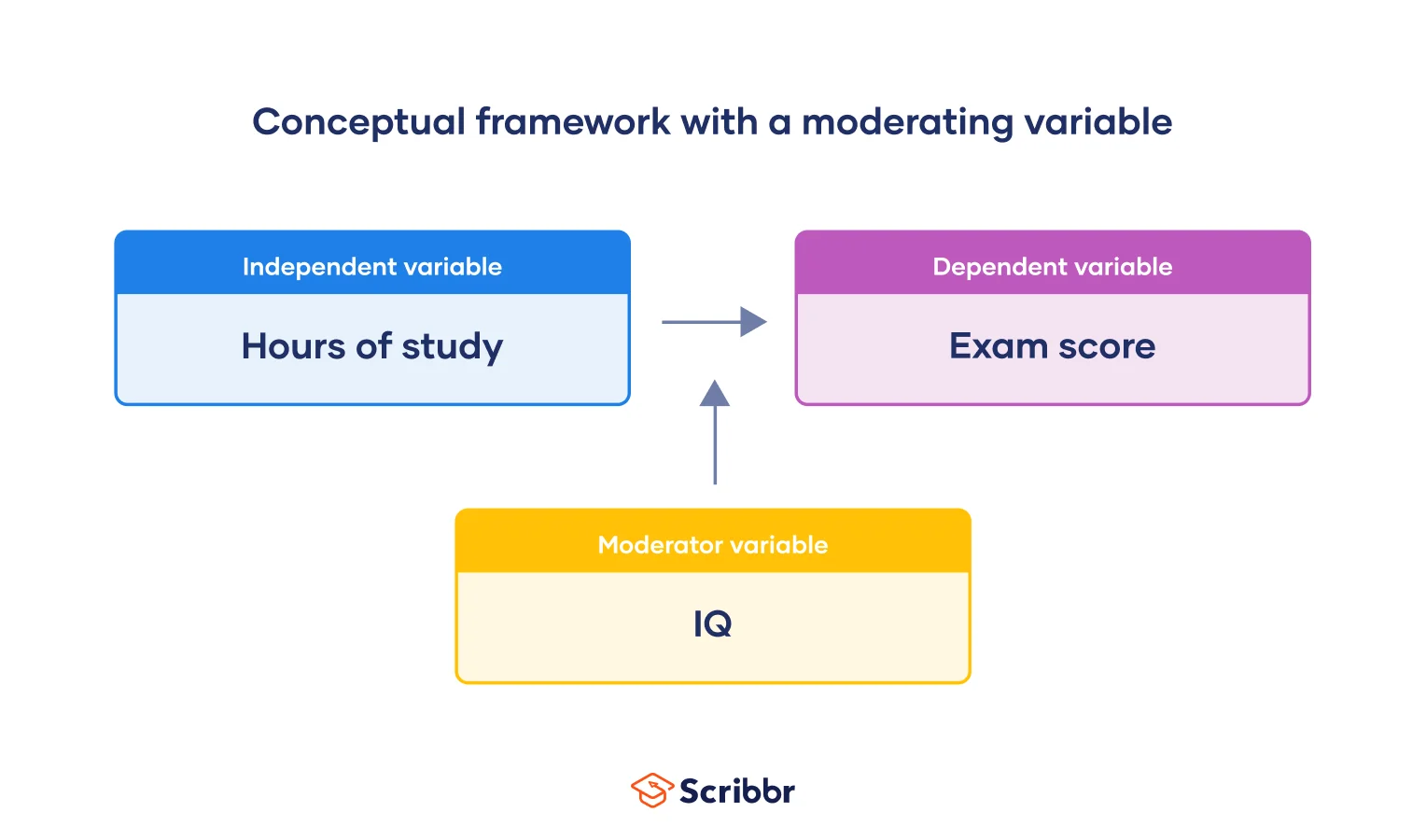

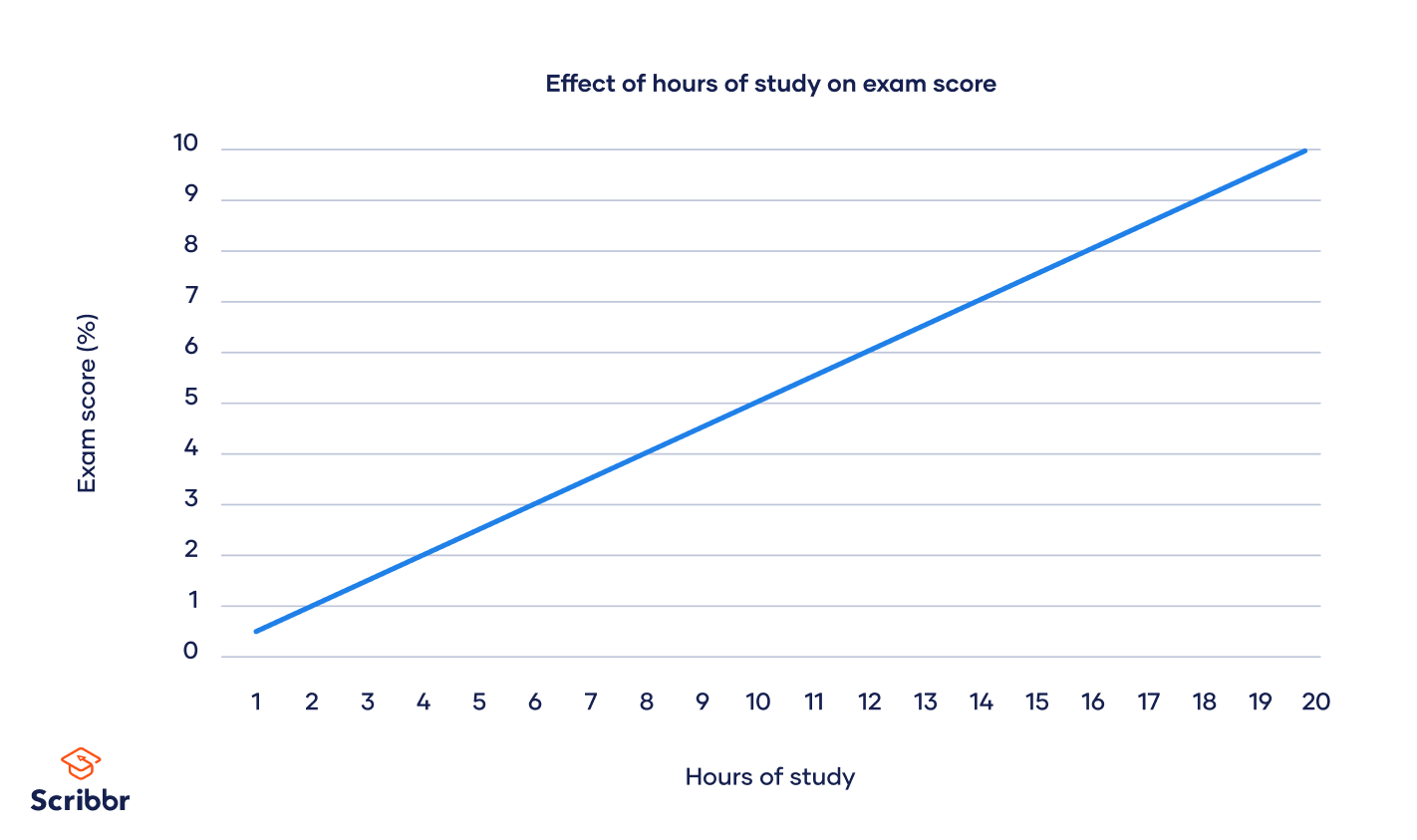

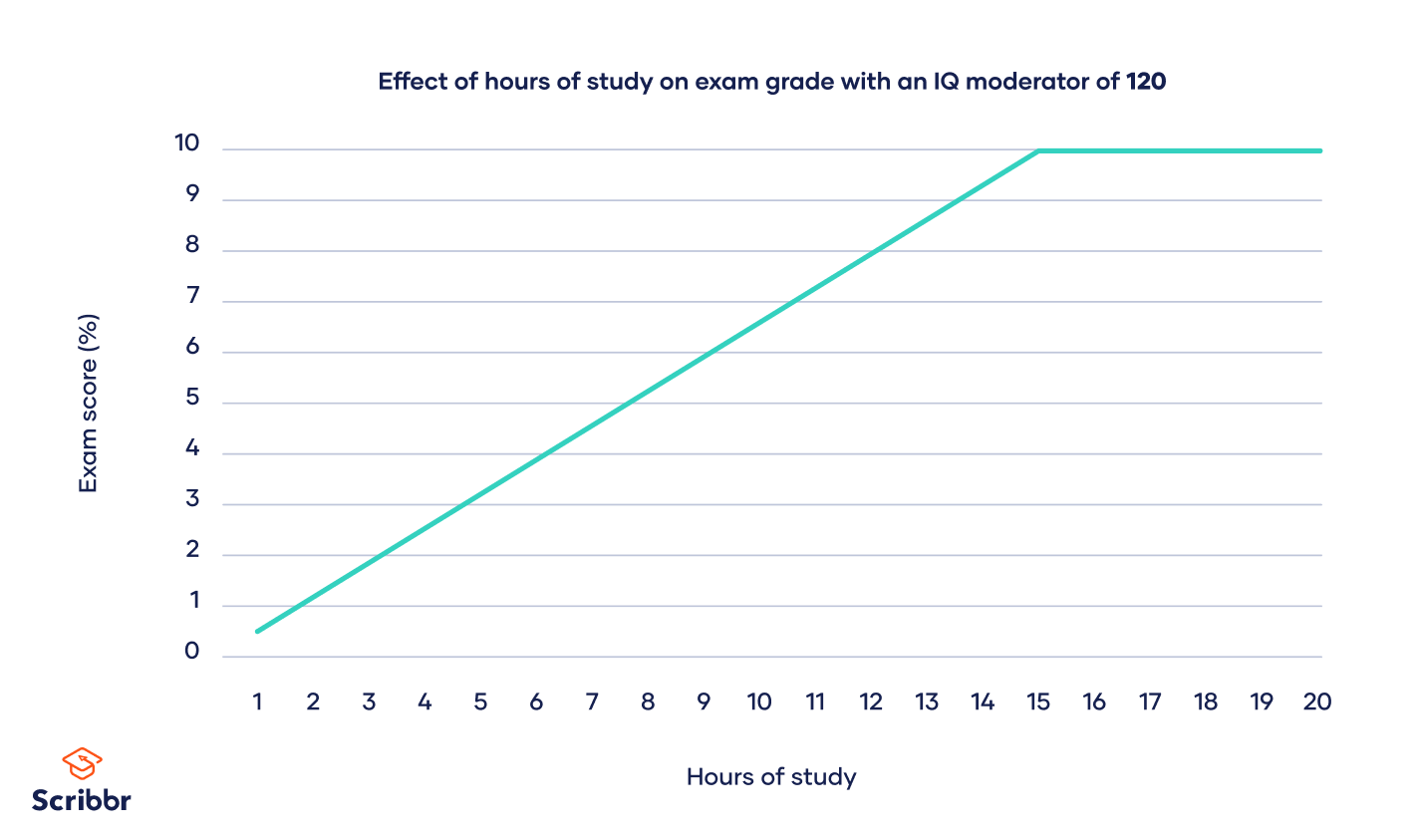

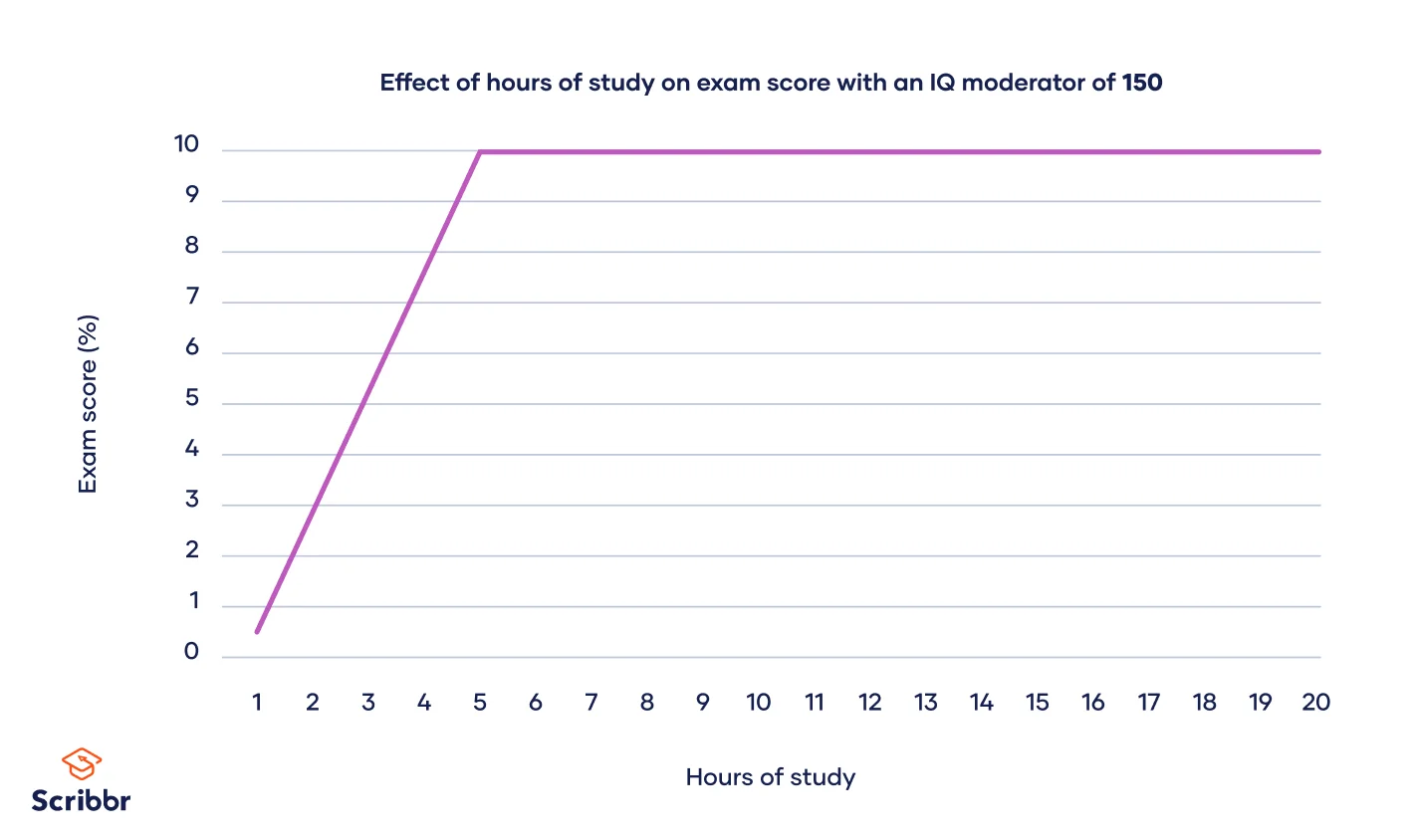

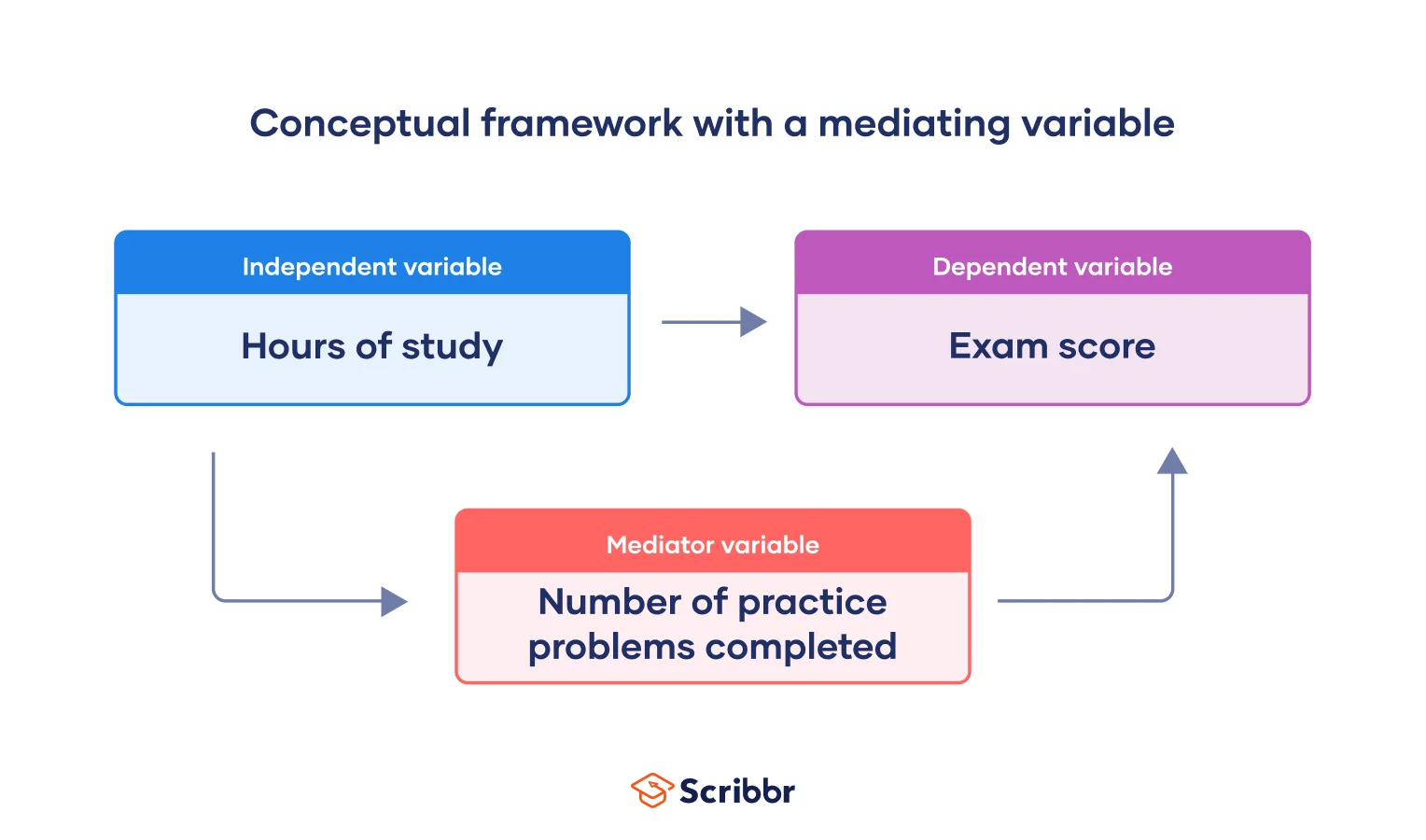

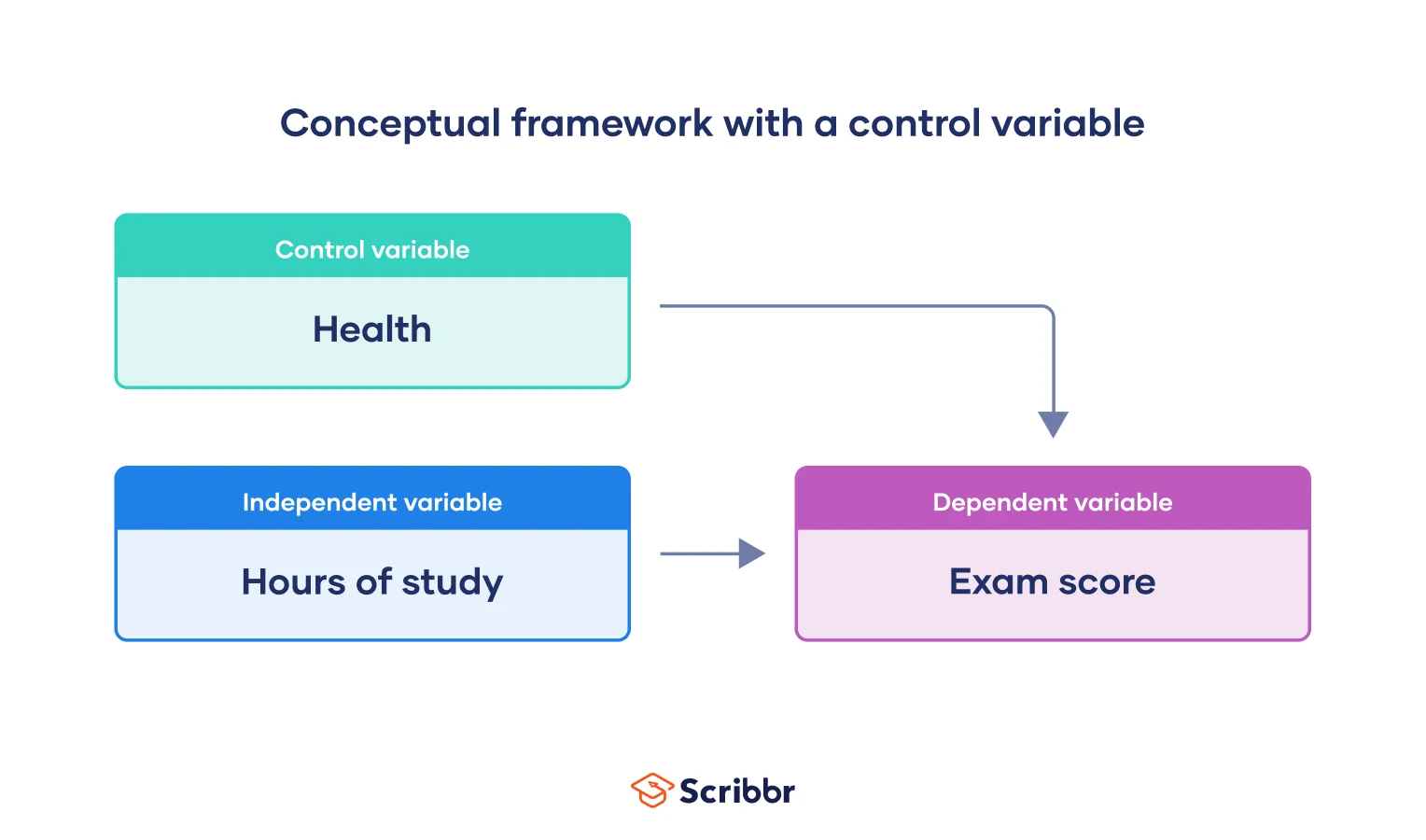

A conceptual framework is typically a visual representation (although it can also be written out) of the expected relationships and connections between various concepts, constructs or variables. In other words, a conceptual framework visualises how the researcher views and organises the various concepts and variables within their study. This is typically based on aspects drawn from the theoretical framework, so there is a relationship between the two.

Quite commonly, conceptual frameworks are used to visualise the potential causal relationships and pathways that the researcher expects to find, based on their understanding of both the theoretical literature and the existing empirical research . Therefore, the conceptual framework is often used to develop research questions and hypotheses .

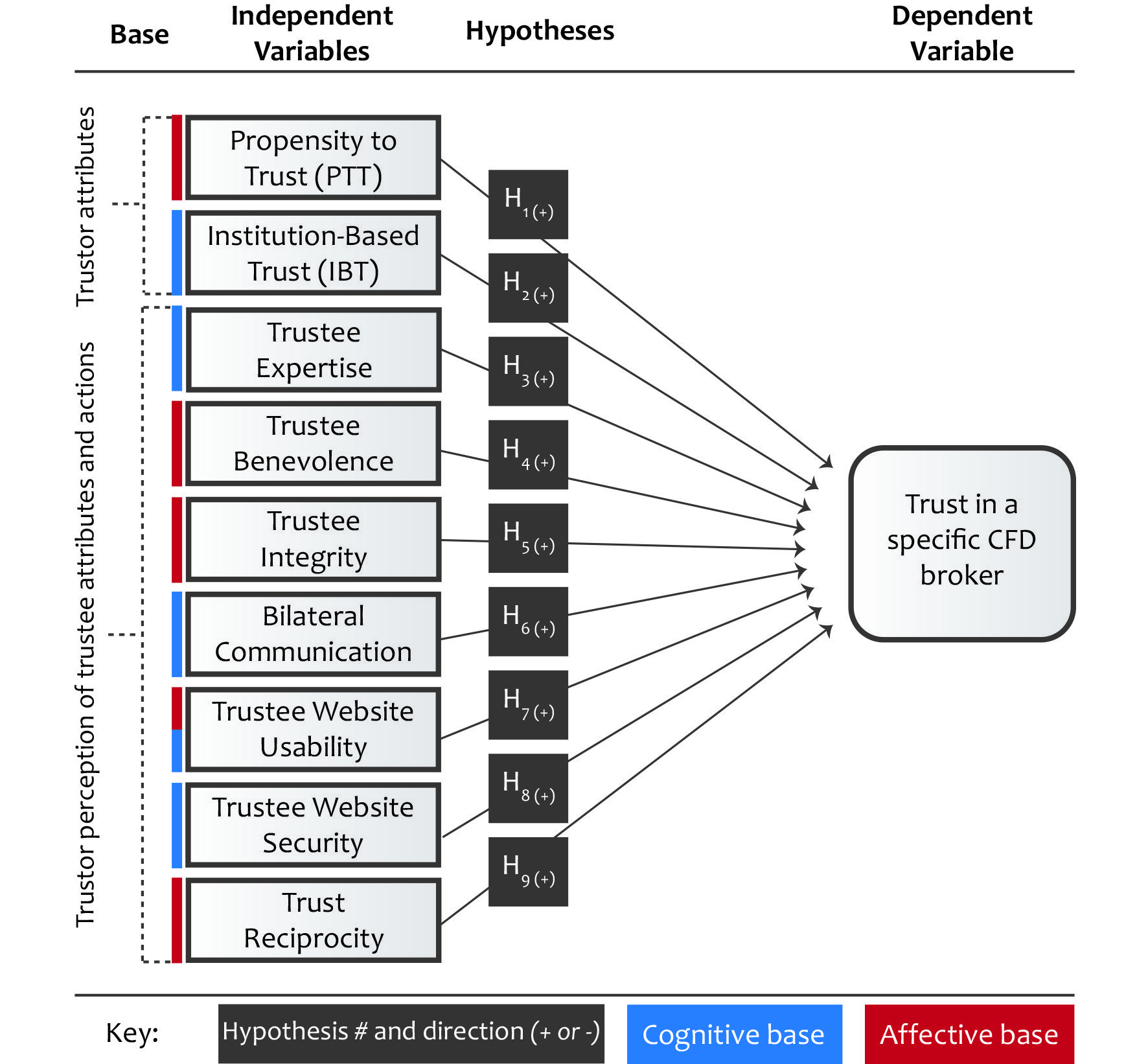

Let’s look at an example of a conceptual framework to make it a little more tangible. You’ll notice that in this specific conceptual framework, the hypotheses are integrated into the visual, helping to connect the rest of the document to the framework.

As you can see, conceptual frameworks often make use of different shapes , lines and arrows to visualise the connections and relationships between different components and/or variables. Ultimately, the conceptual framework provides an opportunity for you to make explicit your understanding of how everything is connected . So, be sure to make use of all the visual aids you can – clean design, well-considered colours and concise text are your friends.

Theoretical framework vs conceptual framework

As you can see, the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework are closely related concepts, but they differ in terms of focus and purpose. The theoretical framework is used to lay down a foundation of theory on which your study will be built, whereas the conceptual framework visualises what you anticipate the relationships between concepts, constructs and variables may be, based on your understanding of the existing literature and the specific context and focus of your research. In other words, they’re different tools for different jobs , but they’re neighbours in the toolbox.

Naturally, the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework are not mutually exclusive . In fact, it’s quite likely that you’ll include both in your dissertation or thesis, especially if your research aims involve investigating relationships between variables. Of course, every research project is different and universities differ in terms of their expectations for dissertations and theses, so it’s always a good idea to have a look at past projects to get a feel for what the norms and expectations are at your specific institution.

Want to learn more about research terminology, methods and techniques? Be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for hands-on help, have a look at our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research process, step by step.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

19 Comments

Thank you for giving a valuable lesson

good thanks!

VERY INSIGHTFUL

thanks for given very interested understand about both theoritical and conceptual framework

I am researching teacher beliefs about inclusive education but not using a theoretical framework just conceptual frame using teacher beliefs, inclusive education and inclusive practices as my concepts

good, fantastic

great! thanks for the clarification. I am planning to use both for my implementation evaluation of EmONC service at primary health care facility level. its theoretical foundation rooted from the principles of implementation science.

This is a good one…now have a better understanding of Theoretical and Conceptual frameworks. Highly grateful

Very educating and fantastic,good to be part of you guys,I appreciate your enlightened concern.

Thanks for shedding light on these two t opics. Much clearer in my head now.

Simple and clear!

The differences between the two topics was well explained, thank you very much!

Thank you great insight

Superb. Thank you so much.

Hello Gradcoach! I’m excited with your fantastic educational videos which mainly focused on all over research process. I’m a student, I kindly ask and need your support. So, if it’s possible please send me the PDF format of all topic provided here, I put my email below, thank you!

I am really grateful I found this website. This is very helpful for an MPA student like myself.

I’m clear with these two terminologies now. Useful information. I appreciate it. Thank you

I’m well inform about these two concepts in research. Thanks

I found this really helpful. It is well explained. Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format.

Updated on August 28, 2023

What are frameworks in research?

Both theoretical and conceptual frameworks have a significant role in research. Frameworks are essential to bridge the gaps in research. They aid in clearly setting the goals, priorities, relationship between variables. Frameworks in research particularly help in chalking clear process details.

Theoretical frameworks largely work at the time when a theoretical roadmap has been laid about a certain topic and the research being undertaken by the researcher, carefully analyzes it, and works on similar lines to attain successful results.

It varies from a conceptual framework in terms of the preliminary work required to construct it. Though a conceptual framework is part of the theoretical framework in a larger sense, yet there are variations between them.

The following sections delve deeper into the characteristics of conceptual frameworks. This article will provide insight into constructing a concise, complete, and research-friendly conceptual framework for your project.

Definition of a conceptual framework

True research begins with setting empirical goals. Goals aid in presenting successful answers to the research questions at hand. It delineates a process wherein different aspects of the research are reflected upon, and coherence is established among them.

A conceptual framework is an underrated methodological approach that should be paid attention to before embarking on a research journey in any field, be it science, finance, history, psychology, etc.

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format. Your conceptual framework establishes a link between the dependent and independent variables, factors, and other ideologies affecting the structure of your research.

A critical facet a conceptual framework unveils is the relationship the researchers have with their research. It closely highlights the factors that play an instrumental role in decision-making, variable selection, data collection, assessment of results, and formulation of new theories.

Consequently, if you, the researcher, are at the forefront of your research battlefield, your conceptual framework is the most powerful arsenal in your pocket.

What should be included in a conceptual framework?

A conceptual framework includes the key process parameters, defining variables, and cause-and-effect relationships. To add to this, the primary focus while developing a conceptual framework should remain on the quality of questions being raised and addressed through the framework. This will not only ease the process of initiation, but also enable you to draw meaningful conclusions from the same.

A practical and advantageous approach involves selecting models and analyzing literature that is unconventional and not directly related to the topic. This helps the researcher design an illustrative framework that is multidisciplinary and simultaneously looks at a diverse range of phenomena. It also emboldens the roots of exploratory research.

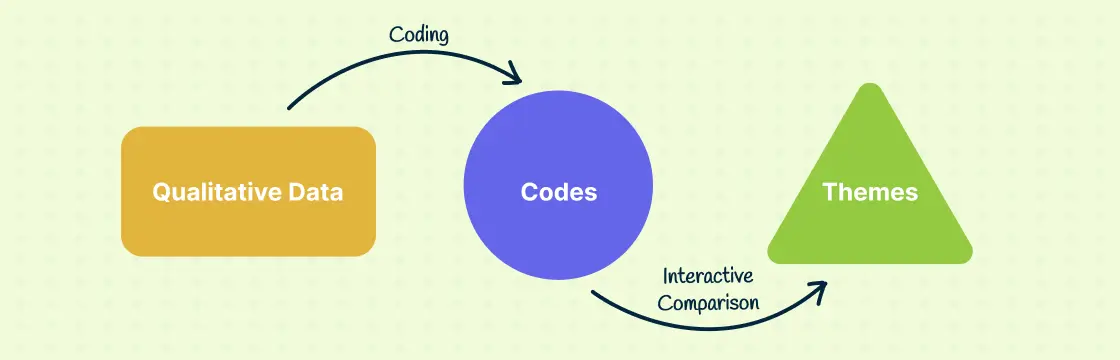

Fig. 1: Components of a conceptual framework

How to make a conceptual framework

The successful design of a conceptual framework includes:

- Selecting the appropriate research questions

- Defining the process variables (dependent, independent, and others)

- Determining the cause-and-effect relationships

This analytical tool begins with defining the most suitable set of questions that the research wishes to answer upon its conclusion. Following this, the different variety of variables is categorized. Lastly, the collected data is subjected to rigorous data analysis. Final results are compiled to establish links between the variables.

The variables drawn inside frames impact the overall quality of the research. If the framework involves arrows, it suggests correlational linkages among the variables. Lines, on the other hand, suggest that no significant correlation exists among them. Henceforth, the utilization of lines and arrows should be done taking into cognizance the meaning they both imply.

Example of a conceptual framework

To provide an idea about a conceptual framework, let’s examine the example of drug development research.

Say a new drug moiety A has to be launched in the market. For that, the baseline research begins with selecting the appropriate drug molecule. This is important because it:

- Provides the data for molecular docking studies to identify suitable target proteins

- Performs in vitro (a process taking place outside a living organism) and in vivo (a process taking place inside a living organism) analyzes

This assists in the screening of the molecules and a final selection leading to the most suitable target molecule. In this case, the choice of the drug molecule is an independent variable whereas, all the others, targets from molecular docking studies, and results from in vitro and in vivo analyses are dependent variables.

The outcomes revealed by the studies might be coherent or incoherent with the literature. In any case, an accurately designed conceptual framework will efficiently establish the cause-and-effect relationship and explain both perspectives satisfactorily.

If A has been chosen to be launched in the market, the conceptual framework will point towards the factors that have led to its selection. If A does not make it to the market, the key elements which did not work in its favor can be pinpointed by an accurate analysis of the conceptual framework.

Fig. 2: Concise example of a conceptual framework

Important takeaways

While conceptual frameworks are a great way of designing the research protocol, they might consist of some unforeseen loopholes. A review of the literature can sometimes provide a false impression of the collection of work done worldwide while in actuality, there might be research that is being undertaken on the same topic but is still under publication or review. Strong conceptual frameworks, therefore, are designed when all these aspects are taken into consideration and the researchers indulge in discussions with others working on similar grounds of research.

Conceptual frameworks may also sometimes lead to collecting and reviewing data that is not so relevant to the current research topic. The researchers must always be on the lookout for studies that are highly relevant to their topic of work and will be of impact if taken into consideration.

Another common practice associated with conceptual frameworks is their classification as merely descriptive qualitative tools and not actually a concrete build-up of ideas and critically analyzed literature and data which it is, in reality. Ideal conceptual frameworks always bring out their own set of new ideas after analysis of literature rather than simply depending on facts being already reported by other research groups.

So, the next time you set out to construct your conceptual framework or improvise on your previous one, be wary that concepts for your research are ideas that need to be worked upon. They are not simply a collection of literature from the previous research.

Final thoughts

Research is witnessing a boom in the methodical approaches being applied to it nowadays. In contrast to conventional research, researchers today are always looking for better techniques and methods to improve the quality of their research.

We strongly believe in the ideals of research that are not merely academic, but all-inclusive. We strongly encourage all our readers and researchers to do work that impacts society. Designing strong conceptual frameworks is an integral part of the process. It gives headway for systematic, empirical, and fruitful research.

Vridhi Sachdeva, MPharm

See our "Privacy Policy"

Get an overall assessment of the main focus of your study from AJE

Our Presubmission Review service will provide recommendations on the structure, organization, and the overall presentation of your research manuscript.

How to Use a Conceptual Framework for Better Research

A conceptual framework in research is not just a tool but a vital roadmap that guides the entire research process. It integrates various theories, assumptions, and beliefs to provide a structured approach to research. By defining a conceptual framework, researchers can focus their inquiries and clarify their hypotheses, leading to more effective and meaningful research outcomes.

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework is essentially an analytical tool that combines concepts and sets them within an appropriate theoretical structure. It serves as a lens through which researchers view the complexities of the real world. The importance of a conceptual framework lies in its ability to serve as a guide, helping researchers to not only visualize but also systematically approach their study.

Key Components and to be Analyzed During Research

- Theories: These are the underlying principles that guide the hypotheses and assumptions of the research.

- Assumptions: These are the accepted truths that are not tested within the scope of the research but are essential for framing the study.

- Beliefs: These often reflect the subjective viewpoints that may influence the interpretation of data.

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

Together, these components help to define the conceptual framework that directs the research towards its ultimate goal. This structured approach not only improves clarity but also enhances the validity and reliability of the research outcomes. By using a conceptual framework, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and focus on essential variables and relationships.

For practical examples and to see how different frameworks can be applied in various research scenarios, you can Explore Conceptual Framework Examples .

Different Types of Conceptual Frameworks Used in Research

Understanding the various types of conceptual frameworks is crucial for researchers aiming to align their studies with the most effective structure. Conceptual frameworks in research vary primarily between theoretical and operational frameworks, each serving distinct purposes and suiting different research methodologies.

Theoretical vs Operational Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are built upon existing theories and literature, providing a broad and abstract understanding of the research topic. They help in forming the basis of the study by linking the research to already established scholarly works. On the other hand, operational frameworks are more practical, focusing on how the study’s theories will be tested through specific procedures and variables.

- Theoretical frameworks are ideal for exploratory studies and can help in understanding complex phenomena.

- Operational frameworks suit studies requiring precise measurement and data analysis.

Choosing the Right Framework

Selecting the appropriate conceptual framework is pivotal for the success of a research project. It involves matching the research questions with the framework that best addresses the methodological needs of the study. For instance, a theoretical framework might be chosen for studies that aim to generate new theories, while an operational framework would be better suited for testing specific hypotheses.

Benefits of choosing the right framework include enhanced clarity, better alignment with research goals, and improved validity of research outcomes. Tools like Table Chart Maker can be instrumental in visually comparing the strengths and weaknesses of different frameworks, aiding in this crucial decision-making process.

Real-World Examples of Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Understanding the practical application of conceptual frameworks in research can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your studies. Here, we explore several real-world case studies that demonstrate the pivotal role of conceptual frameworks in achieving robust research conclusions.

- Healthcare Research: In a study examining the impact of lifestyle choices on chronic diseases, researchers used a conceptual framework to link dietary habits, exercise, and genetic predispositions. This framework helped in identifying key variables and their interrelations, leading to more targeted interventions.

- Educational Development: Educational theorists often employ conceptual frameworks to explore the dynamics between teaching methods and student learning outcomes. One notable study mapped out the influences of digital tools on learning engagement, providing insights that shaped educational policies.

- Environmental Policy: Conceptual frameworks have been crucial in environmental research, particularly in studies on climate change adaptation. By framing the relationships between human activity, ecological changes, and policy responses, researchers have been able to propose more effective sustainability strategies.

Adapting conceptual frameworks based on evolving research data is also critical. As new information becomes available, it’s essential to revisit and adjust the framework to maintain its relevance and accuracy, ensuring that the research remains aligned with real-world conditions.

For those looking to visualize and better comprehend their research frameworks, Graphic Organizers for Conceptual Frameworks can be an invaluable tool. These organizers help in structuring and presenting research findings clearly, enhancing both the process and the presentation of your research.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Own Conceptual Framework

Creating a conceptual framework is a critical step in structuring your research to ensure clarity and focus. This guide will walk you through the process of building a robust framework, from identifying key concepts to refining your approach as your research evolves.

Building Blocks of a Conceptual Framework

- Identify and Define Main Concepts and Variables: Start by clearly identifying the main concepts, variables, and their relationships that will form the basis of your research. This could include defining key terms and establishing the scope of your study.

- Develop a Hypothesis or Primary Research Question: Formulate a central hypothesis or question that guides the direction of your research. This will serve as the foundation upon which your conceptual framework is built.

- Link Theories and Concepts Logically: Connect your identified concepts and variables with existing theories to create a coherent structure. This logical linking helps in forming a strong theoretical base for your research.

Visualizing and Refining Your Framework

Using visual tools can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your conceptual framework. Decision Tree Templates for Conceptual Frameworks can be particularly useful in mapping out the relationships between variables and hypotheses.

Map Your Framework: Utilize tools like Creately’s visual canvas to diagram your framework. This visual representation helps in identifying gaps or overlaps in your framework and provides a clear overview of your research structure.

Analyze and Refine: As your research progresses, continuously evaluate and refine your framework. Adjustments may be necessary as new data comes to light or as initial assumptions are challenged.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your conceptual framework is not only well-defined but also adaptable to the changing dynamics of your research.

Practical Tips for Utilizing Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Effectively utilizing a conceptual framework in research not only streamlines the process but also enhances the clarity and coherence of your findings. Here are some practical tips to maximize the use of conceptual frameworks in your research endeavors.

- Setting Clear Research Goals: Begin by defining precise objectives that are aligned with your research questions. This clarity will guide your entire research process, ensuring that every step you take is purposeful and directly contributes to your overall study aims. \

- Maintaining Focus and Coherence: Throughout the research, consistently refer back to your conceptual framework to maintain focus. This will help in keeping your research aligned with the initial goals and prevent deviations that could dilute the effectiveness of your findings.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Use your conceptual framework as a lens through which to view and interpret data. This approach ensures that the data analysis is not only systematic but also meaningful in the context of your research objectives. For more insights, explore Research Data Analysis Methods .

- Presenting Research Findings: When it comes time to present your findings, structure your presentation around the conceptual framework . This will help your audience understand the logical flow of your research and how each part contributes to the whole.

- Avoiding Common Pitfalls: Be vigilant about common errors such as overcomplicating the framework or misaligning the research methods with the framework’s structure. Keeping it simple and aligned ensures that the framework effectively supports your research.

By adhering to these tips and utilizing tools like 7 Essential Visual Tools for Social Work Assessment , researchers can ensure that their conceptual frameworks are not only robust but also practically applicable in their studies.

How Creately Enhances the Creation and Use of Conceptual Frameworks

Creating a robust conceptual framework is pivotal for effective research, and Creately’s suite of visual tools offers unparalleled support in this endeavor. By leveraging Creately’s features, researchers can visualize, organize, and analyze their research frameworks more efficiently.

- Visual Mapping of Research Plans: Creately’s infinite visual canvas allows researchers to map out their entire research plan visually. This helps in understanding the complex relationships between different research variables and theories, enhancing the clarity and effectiveness of the research process.

- Brainstorming with Mind Maps: Using Mind Mapping Software , researchers can generate and organize ideas dynamically. Creately’s intelligent formatting helps in brainstorming sessions, making it easier to explore multiple topics or delve deeply into specific concepts.

- Centralized Data Management: Creately enables the importation of data from multiple sources, which can be integrated into the visual research framework. This centralization aids in maintaining a cohesive and comprehensive overview of all research elements, ensuring that no critical information is overlooked.

- Communication and Collaboration: The platform supports real-time collaboration, allowing teams to work together seamlessly, regardless of their physical location. This feature is crucial for research teams spread across different geographies, facilitating effective communication and iterative feedback throughout the research process.

Moreover, the ability t Explore Conceptual Framework Examples directly within Creately inspires researchers by providing practical templates and examples that can be customized to suit specific research needs. This not only saves time but also enhances the quality of the conceptual framework developed.

In conclusion, Creately’s tools for creating and managing conceptual frameworks are indispensable for researchers aiming to achieve clear, structured, and impactful research outcomes.

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

Chiraag George is a communication specialist here at Creately. He is a marketing junkie that is fascinated by how brands occupy consumer mind space. A lover of all things tech, he writes a lot about the intersection of technology, branding and culture at large.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers

Julie a. luft.

† Department of Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Education, Mary Frances Early College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7124

Sophia Jeong

‡ Department of Teaching & Learning, College of Education & Human Ecology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

Robert Idsardi

§ Department of Biology, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, WA 99004

Grant Gardner

∥ Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

Associated Data

To frame their work, biology education researchers need to consider the role of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks as critical elements of the research and writing process. However, these elements can be confusing for scholars new to education research. This Research Methods article is designed to provide an overview of each of these elements and delineate the purpose of each in the educational research process. We describe what biology education researchers should consider as they conduct literature reviews, identify theoretical frameworks, and construct conceptual frameworks. Clarifying these different components of educational research studies can be helpful to new biology education researchers and the biology education research community at large in situating their work in the broader scholarly literature.

INTRODUCTION

Discipline-based education research (DBER) involves the purposeful and situated study of teaching and learning in specific disciplinary areas ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Studies in DBER are guided by research questions that reflect disciplines’ priorities and worldviews. Researchers can use quantitative data, qualitative data, or both to answer these research questions through a variety of methodological traditions. Across all methodologies, there are different methods associated with planning and conducting educational research studies that include the use of surveys, interviews, observations, artifacts, or instruments. Ensuring the coherence of these elements to the discipline’s perspective also involves situating the work in the broader scholarly literature. The tools for doing this include literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks. However, the purpose and function of each of these elements is often confusing to new education researchers. The goal of this article is to introduce new biology education researchers to these three important elements important in DBER scholarship and the broader educational literature.

The first element we discuss is a review of research (literature reviews), which highlights the need for a specific research question, study problem, or topic of investigation. Literature reviews situate the relevance of the study within a topic and a field. The process may seem familiar to science researchers entering DBER fields, but new researchers may still struggle in conducting the review. Booth et al. (2016b) highlight some of the challenges novice education researchers face when conducting a review of literature. They point out that novice researchers struggle in deciding how to focus the review, determining the scope of articles needed in the review, and knowing how to be critical of the articles in the review. Overcoming these challenges (and others) can help novice researchers construct a sound literature review that can inform the design of the study and help ensure the work makes a contribution to the field.

The second and third highlighted elements are theoretical and conceptual frameworks. These guide biology education research (BER) studies, and may be less familiar to science researchers. These elements are important in shaping the construction of new knowledge. Theoretical frameworks offer a way to explain and interpret the studied phenomenon, while conceptual frameworks clarify assumptions about the studied phenomenon. Despite the importance of these constructs in educational research, biology educational researchers have noted the limited use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in published work ( DeHaan, 2011 ; Dirks, 2011 ; Lo et al. , 2019 ). In reviewing articles published in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) between 2015 and 2019, we found that fewer than 25% of the research articles had a theoretical or conceptual framework (see the Supplemental Information), and at times there was an inconsistent use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Clearly, these frameworks are challenging for published biology education researchers, which suggests the importance of providing some initial guidance to new biology education researchers.

Fortunately, educational researchers have increased their explicit use of these frameworks over time, and this is influencing educational research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. For instance, a quick search for theoretical or conceptual frameworks in the abstracts of articles in Educational Research Complete (a common database for educational research) in STEM fields demonstrates a dramatic change over the last 20 years: from only 778 articles published between 2000 and 2010 to 5703 articles published between 2010 and 2020, a more than sevenfold increase. Greater recognition of the importance of these frameworks is contributing to DBER authors being more explicit about such frameworks in their studies.

Collectively, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks work to guide methodological decisions and the elucidation of important findings. Each offers a different perspective on the problem of study and is an essential element in all forms of educational research. As new researchers seek to learn about these elements, they will find different resources, a variety of perspectives, and many suggestions about the construction and use of these elements. The wide range of available information can overwhelm the new researcher who just wants to learn the distinction between these elements or how to craft them adequately.

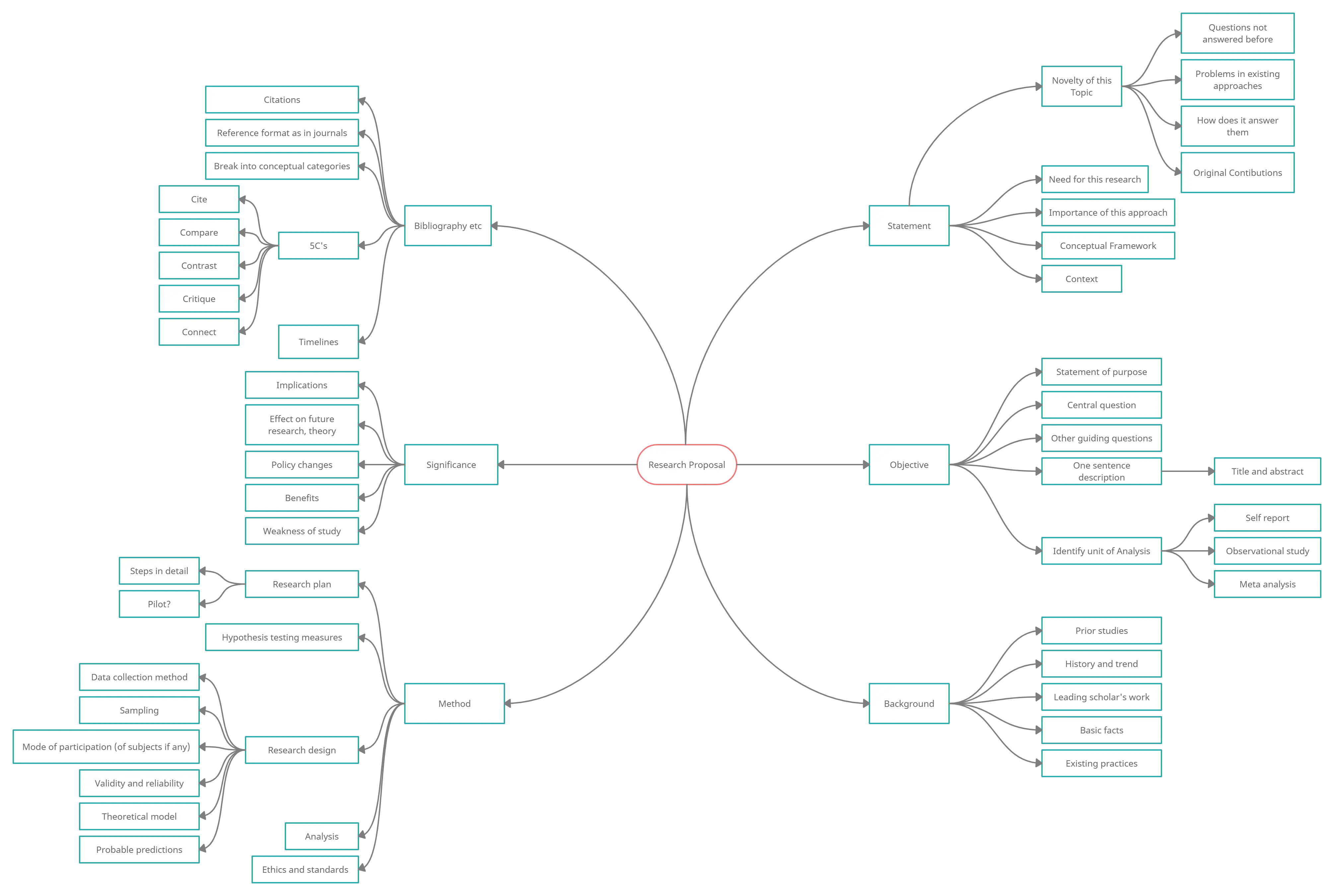

Our goal in writing this paper is not to offer specific advice about how to write these sections in scholarly work. Instead, we wanted to introduce these elements to those who are new to BER and who are interested in better distinguishing one from the other. In this paper, we share the purpose of each element in BER scholarship, along with important points on its construction. We also provide references for additional resources that may be beneficial to better understanding each element. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions among these elements.

Comparison of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual reviews

This article is written for the new biology education researcher who is just learning about these different elements or for scientists looking to become more involved in BER. It is a result of our own work as science education and biology education researchers, whether as graduate students and postdoctoral scholars or newly hired and established faculty members. This is the article we wish had been available as we started to learn about these elements or discussed them with new educational researchers in biology.

LITERATURE REVIEWS

Purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is foundational to any research study in education or science. In education, a well-conceptualized and well-executed review provides a summary of the research that has already been done on a specific topic and identifies questions that remain to be answered, thus illustrating the current research project’s potential contribution to the field and the reasoning behind the methodological approach selected for the study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). BER is an evolving disciplinary area that is redefining areas of conceptual emphasis as well as orientations toward teaching and learning (e.g., Labov et al. , 2010 ; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; Nehm, 2019 ). As a result, building comprehensive, critical, purposeful, and concise literature reviews can be a challenge for new biology education researchers.

Building Literature Reviews

There are different ways to approach and construct a literature review. Booth et al. (2016a) provide an overview that includes, for example, scoping reviews, which are focused only on notable studies and use a basic method of analysis, and integrative reviews, which are the result of exhaustive literature searches across different genres. Underlying each of these different review processes are attention to the s earch process, a ppraisa l of articles, s ynthesis of the literature, and a nalysis: SALSA ( Booth et al. , 2016a ). This useful acronym can help the researcher focus on the process while building a specific type of review.

However, new educational researchers often have questions about literature reviews that are foundational to SALSA or other approaches. Common questions concern determining which literature pertains to the topic of study or the role of the literature review in the design of the study. This section addresses such questions broadly while providing general guidance for writing a narrative literature review that evaluates the most pertinent studies.

The literature review process should begin before the research is conducted. As Boote and Beile (2005 , p. 3) suggested, researchers should be “scholars before researchers.” They point out that having a good working knowledge of the proposed topic helps illuminate avenues of study. Some subject areas have a deep body of work to read and reflect upon, providing a strong foundation for developing the research question(s). For instance, the teaching and learning of evolution is an area of long-standing interest in the BER community, generating many studies (e.g., Perry et al. , 2008 ; Barnes and Brownell, 2016 ) and reviews of research (e.g., Sickel and Friedrichsen, 2013 ; Ziadie and Andrews, 2018 ). Emerging areas of BER include the affective domain, issues of transfer, and metacognition ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Many studies in these areas are transdisciplinary and not always specific to biology education (e.g., Rodrigo-Peiris et al. , 2018 ; Kolpikova et al. , 2019 ). These newer areas may require reading outside BER; fortunately, summaries of some of these topics can be found in the Current Insights section of the LSE website.

In focusing on a specific problem within a broader research strand, a new researcher will likely need to examine research outside BER. Depending upon the area of study, the expanded reading list might involve a mix of BER, DBER, and educational research studies. Determining the scope of the reading is not always straightforward. A simple way to focus one’s reading is to create a “summary phrase” or “research nugget,” which is a very brief descriptive statement about the study. It should focus on the essence of the study, for example, “first-year nonmajor students’ understanding of evolution,” “metacognitive prompts to enhance learning during biochemistry,” or “instructors’ inquiry-based instructional practices after professional development programming.” This type of phrase should help a new researcher identify two or more areas to review that pertain to the study. Focusing on recent research in the last 5 years is a good first step. Additional studies can be identified by reading relevant works referenced in those articles. It is also important to read seminal studies that are more than 5 years old. Reading a range of studies should give the researcher the necessary command of the subject in order to suggest a research question.

Given that the research question(s) arise from the literature review, the review should also substantiate the selected methodological approach. The review and research question(s) guide the researcher in determining how to collect and analyze data. Often the methodological approach used in a study is selected to contribute knowledge that expands upon what has been published previously about the topic (see Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation, 2013 ). An emerging topic of study may need an exploratory approach that allows for a description of the phenomenon and development of a potential theory. This could, but not necessarily, require a methodological approach that uses interviews, observations, surveys, or other instruments. An extensively studied topic may call for the additional understanding of specific factors or variables; this type of study would be well suited to a verification or a causal research design. These could entail a methodological approach that uses valid and reliable instruments, observations, or interviews to determine an effect in the studied event. In either of these examples, the researcher(s) may use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods methodological approach.

Even with a good research question, there is still more reading to be done. The complexity and focus of the research question dictates the depth and breadth of the literature to be examined. Questions that connect multiple topics can require broad literature reviews. For instance, a study that explores the impact of a biology faculty learning community on the inquiry instruction of faculty could have the following review areas: learning communities among biology faculty, inquiry instruction among biology faculty, and inquiry instruction among biology faculty as a result of professional learning. Biology education researchers need to consider whether their literature review requires studies from different disciplines within or outside DBER. For the example given, it would be fruitful to look at research focused on learning communities with faculty in STEM fields or in general education fields that result in instructional change. It is important not to be too narrow or too broad when reading. When the conclusions of articles start to sound similar or no new insights are gained, the researcher likely has a good foundation for a literature review. This level of reading should allow the researcher to demonstrate a mastery in understanding the researched topic, explain the suitability of the proposed research approach, and point to the need for the refined research question(s).

The literature review should include the researcher’s evaluation and critique of the selected studies. A researcher may have a large collection of studies, but not all of the studies will follow standards important in the reporting of empirical work in the social sciences. The American Educational Research Association ( Duran et al. , 2006 ), for example, offers a general discussion about standards for such work: an adequate review of research informing the study, the existence of sound and appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and appropriate conclusions that do not overstep or underexplore the analyzed data. The Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation (2013) also offer Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development that can be used to evaluate collected studies.

Because not all journals adhere to such standards, it is important that a researcher review each study to determine the quality of published research, per the guidelines suggested earlier. In some instances, the research may be fatally flawed. Examples of such flaws include data that do not pertain to the question, a lack of discussion about the data collection, poorly constructed instruments, or an inadequate analysis. These types of errors result in studies that are incomplete, error-laden, or inaccurate and should be excluded from the review. Most studies have limitations, and the author(s) often make them explicit. For instance, there may be an instructor effect, recognized bias in the analysis, or issues with the sample population. Limitations are usually addressed by the research team in some way to ensure a sound and acceptable research process. Occasionally, the limitations associated with the study can be significant and not addressed adequately, which leaves a consequential decision in the hands of the researcher. Providing critiques of studies in the literature review process gives the reader confidence that the researcher has carefully examined relevant work in preparation for the study and, ultimately, the manuscript.

A solid literature review clearly anchors the proposed study in the field and connects the research question(s), the methodological approach, and the discussion. Reviewing extant research leads to research questions that will contribute to what is known in the field. By summarizing what is known, the literature review points to what needs to be known, which in turn guides decisions about methodology. Finally, notable findings of the new study are discussed in reference to those described in the literature review.

Within published BER studies, literature reviews can be placed in different locations in an article. When included in the introductory section of the study, the first few paragraphs of the manuscript set the stage, with the literature review following the opening paragraphs. Cooper et al. (2019) illustrate this approach in their study of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). An introduction discussing the potential of CURES is followed by an analysis of the existing literature relevant to the design of CUREs that allows for novel student discoveries. Within this review, the authors point out contradictory findings among research on novel student discoveries. This clarifies the need for their study, which is described and highlighted through specific research aims.

A literature reviews can also make up a separate section in a paper. For example, the introduction to Todd et al. (2019) illustrates the need for their research topic by highlighting the potential of learning progressions (LPs) and suggesting that LPs may help mitigate learning loss in genetics. At the end of the introduction, the authors state their specific research questions. The review of literature following this opening section comprises two subsections. One focuses on learning loss in general and examines a variety of studies and meta-analyses from the disciplines of medical education, mathematics, and reading. The second section focuses specifically on LPs in genetics and highlights student learning in the midst of LPs. These separate reviews provide insights into the stated research question.

Suggestions and Advice

A well-conceptualized, comprehensive, and critical literature review reveals the understanding of the topic that the researcher brings to the study. Literature reviews should not be so big that there is no clear area of focus; nor should they be so narrow that no real research question arises. The task for a researcher is to craft an efficient literature review that offers a critical analysis of published work, articulates the need for the study, guides the methodological approach to the topic of study, and provides an adequate foundation for the discussion of the findings.

In our own writing of literature reviews, there are often many drafts. An early draft may seem well suited to the study because the need for and approach to the study are well described. However, as the results of the study are analyzed and findings begin to emerge, the existing literature review may be inadequate and need revision. The need for an expanded discussion about the research area can result in the inclusion of new studies that support the explanation of a potential finding. The literature review may also prove to be too broad. Refocusing on a specific area allows for more contemplation of a finding.

It should be noted that there are different types of literature reviews, and many books and articles have been written about the different ways to embark on these types of reviews. Among these different resources, the following may be helpful in considering how to refine the review process for scholarly journals:

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book addresses different types of literature reviews and offers important suggestions pertaining to defining the scope of the literature review and assessing extant studies.

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. This book can help the novice consider how to make the case for an area of study. While this book is not specifically about literature reviews, it offers suggestions about making the case for your study.

- Galvan, J. L., & Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (7th ed.). Routledge. This book offers guidance on writing different types of literature reviews. For the novice researcher, there are useful suggestions for creating coherent literature reviews.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of theoretical frameworks.

As new education researchers may be less familiar with theoretical frameworks than with literature reviews, this discussion begins with an analogy. Envision a biologist, chemist, and physicist examining together the dramatic effect of a fog tsunami over the ocean. A biologist gazing at this phenomenon may be concerned with the effect of fog on various species. A chemist may be interested in the chemical composition of the fog as water vapor condenses around bits of salt. A physicist may be focused on the refraction of light to make fog appear to be “sitting” above the ocean. While observing the same “objective event,” the scientists are operating under different theoretical frameworks that provide a particular perspective or “lens” for the interpretation of the phenomenon. Each of these scientists brings specialized knowledge, experiences, and values to this phenomenon, and these influence the interpretation of the phenomenon. The scientists’ theoretical frameworks influence how they design and carry out their studies and interpret their data.

Within an educational study, a theoretical framework helps to explain a phenomenon through a particular lens and challenges and extends existing knowledge within the limitations of that lens. Theoretical frameworks are explicitly stated by an educational researcher in the paper’s framework, theory, or relevant literature section. The framework shapes the types of questions asked, guides the method by which data are collected and analyzed, and informs the discussion of the results of the study. It also reveals the researcher’s subjectivities, for example, values, social experience, and viewpoint ( Allen, 2017 ). It is essential that a novice researcher learn to explicitly state a theoretical framework, because all research questions are being asked from the researcher’s implicit or explicit assumptions of a phenomenon of interest ( Schwandt, 2000 ).

Selecting Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are one of the most contemplated elements in our work in educational research. In this section, we share three important considerations for new scholars selecting a theoretical framework.

The first step in identifying a theoretical framework involves reflecting on the phenomenon within the study and the assumptions aligned with the phenomenon. The phenomenon involves the studied event. There are many possibilities, for example, student learning, instructional approach, or group organization. A researcher holds assumptions about how the phenomenon will be effected, influenced, changed, or portrayed. It is ultimately the researcher’s assumption(s) about the phenomenon that aligns with a theoretical framework. An example can help illustrate how a researcher’s reflection on the phenomenon and acknowledgment of assumptions can result in the identification of a theoretical framework.

In our example, a biology education researcher may be interested in exploring how students’ learning of difficult biological concepts can be supported by the interactions of group members. The phenomenon of interest is the interactions among the peers, and the researcher assumes that more knowledgeable students are important in supporting the learning of the group. As a result, the researcher may draw on Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory of learning and development that is focused on the phenomenon of student learning in a social setting. This theory posits the critical nature of interactions among students and between students and teachers in the process of building knowledge. A researcher drawing upon this framework holds the assumption that learning is a dynamic social process involving questions and explanations among students in the classroom and that more knowledgeable peers play an important part in the process of building conceptual knowledge.

It is important to state at this point that there are many different theoretical frameworks. Some frameworks focus on learning and knowing, while other theoretical frameworks focus on equity, empowerment, or discourse. Some frameworks are well articulated, and others are still being refined. For a new researcher, it can be challenging to find a theoretical framework. Two of the best ways to look for theoretical frameworks is through published works that highlight different frameworks.

When a theoretical framework is selected, it should clearly connect to all parts of the study. The framework should augment the study by adding a perspective that provides greater insights into the phenomenon. It should clearly align with the studies described in the literature review. For instance, a framework focused on learning would correspond to research that reported different learning outcomes for similar studies. The methods for data collection and analysis should also correspond to the framework. For instance, a study about instructional interventions could use a theoretical framework concerned with learning and could collect data about the effect of the intervention on what is learned. When the data are analyzed, the theoretical framework should provide added meaning to the findings, and the findings should align with the theoretical framework.

A study by Jensen and Lawson (2011) provides an example of how a theoretical framework connects different parts of the study. They compared undergraduate biology students in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups over the course of a semester. Jensen and Lawson (2011) assumed that learning involved collaboration and more knowledgeable peers, which made Vygotsky’s (1978) theory a good fit for their study. They predicted that students in heterogeneous groups would experience greater improvement in their reasoning abilities and science achievements with much of the learning guided by the more knowledgeable peers.

In the enactment of the study, they collected data about the instruction in traditional and inquiry-oriented classes, while the students worked in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups. To determine the effect of working in groups, the authors also measured students’ reasoning abilities and achievement. Each data-collection and analysis decision connected to understanding the influence of collaborative work.

Their findings highlighted aspects of Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of learning. One finding, for instance, posited that inquiry instruction, as a whole, resulted in reasoning and achievement gains. This links to Vygotsky (1978) , because inquiry instruction involves interactions among group members. A more nuanced finding was that group composition had a conditional effect. Heterogeneous groups performed better with more traditional and didactic instruction, regardless of the reasoning ability of the group members. Homogeneous groups worked better during interaction-rich activities for students with low reasoning ability. The authors attributed the variation to the different types of helping behaviors of students. High-performing students provided the answers, while students with low reasoning ability had to work collectively through the material. In terms of Vygotsky (1978) , this finding provided new insights into the learning context in which productive interactions can occur for students.

Another consideration in the selection and use of a theoretical framework pertains to its orientation to the study. This can result in the theoretical framework prioritizing individuals, institutions, and/or policies ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Frameworks that connect to individuals, for instance, could contribute to understanding their actions, learning, or knowledge. Institutional frameworks, on the other hand, offer insights into how institutions, organizations, or groups can influence individuals or materials. Policy theories provide ways to understand how national or local policies can dictate an emphasis on outcomes or instructional design. These different types of frameworks highlight different aspects in an educational setting, which influences the design of the study and the collection of data. In addition, these different frameworks offer a way to make sense of the data. Aligning the data collection and analysis with the framework ensures that a study is coherent and can contribute to the field.

New understandings emerge when different theoretical frameworks are used. For instance, Ebert-May et al. (2015) prioritized the individual level within conceptual change theory (see Posner et al. , 1982 ). In this theory, an individual’s knowledge changes when it no longer fits the phenomenon. Ebert-May et al. (2015) designed a professional development program challenging biology postdoctoral scholars’ existing conceptions of teaching. The authors reported that the biology postdoctoral scholars’ teaching practices became more student-centered as they were challenged to explain their instructional decision making. According to the theory, the biology postdoctoral scholars’ dissatisfaction in their descriptions of teaching and learning initiated change in their knowledge and instruction. These results reveal how conceptual change theory can explain the learning of participants and guide the design of professional development programming.

The communities of practice (CoP) theoretical framework ( Lave, 1988 ; Wenger, 1998 ) prioritizes the institutional level , suggesting that learning occurs when individuals learn from and contribute to the communities in which they reside. Grounded in the assumption of community learning, the literature on CoP suggests that, as individuals interact regularly with the other members of their group, they learn about the rules, roles, and goals of the community ( Allee, 2000 ). A study conducted by Gehrke and Kezar (2017) used the CoP framework to understand organizational change by examining the involvement of individual faculty engaged in a cross-institutional CoP focused on changing the instructional practice of faculty at each institution. In the CoP, faculty members were involved in enhancing instructional materials within their department, which aligned with an overarching goal of instituting instruction that embraced active learning. Not surprisingly, Gehrke and Kezar (2017) revealed that faculty who perceived the community culture as important in their work cultivated institutional change. Furthermore, they found that institutional change was sustained when key leaders served as mentors and provided support for faculty, and as faculty themselves developed into leaders. This study reveals the complexity of individual roles in a COP in order to support institutional instructional change.

It is important to explicitly state the theoretical framework used in a study, but elucidating a theoretical framework can be challenging for a new educational researcher. The literature review can help to identify an applicable theoretical framework. Focal areas of the review or central terms often connect to assumptions and assertions associated with the framework that pertain to the phenomenon of interest. Another way to identify a theoretical framework is self-reflection by the researcher on personal beliefs and understandings about the nature of knowledge the researcher brings to the study ( Lysaght, 2011 ). In stating one’s beliefs and understandings related to the study (e.g., students construct their knowledge, instructional materials support learning), an orientation becomes evident that will suggest a particular theoretical framework. Theoretical frameworks are not arbitrary , but purposefully selected.

With experience, a researcher may find expanded roles for theoretical frameworks. Researchers may revise an existing framework that has limited explanatory power, or they may decide there is a need to develop a new theoretical framework. These frameworks can emerge from a current study or the need to explain a phenomenon in a new way. Researchers may also find that multiple theoretical frameworks are necessary to frame and explore a problem, as different frameworks can provide different insights into a problem.

Finally, it is important to recognize that choosing “x” theoretical framework does not necessarily mean a researcher chooses “y” methodology and so on, nor is there a clear-cut, linear process in selecting a theoretical framework for one’s study. In part, the nonlinear process of identifying a theoretical framework is what makes understanding and using theoretical frameworks challenging. For the novice scholar, contemplating and understanding theoretical frameworks is essential. Fortunately, there are articles and books that can help:

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book provides an overview of theoretical frameworks in general educational research.

- Ding, L. (2019). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research. Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 (2), 020101-1–020101-13. This paper illustrates how a DBER field can use theoretical frameworks.

- Nehm, R. (2019). Biology education research: Building integrative frameworks for teaching and learning about living systems. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research , 1 , ar15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0017-6 . This paper articulates the need for studies in BER to explicitly state theoretical frameworks and provides examples of potential studies.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage. This book also provides an overview of theoretical frameworks, but for both research and evaluation.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of a conceptual framework.

A conceptual framework is a description of the way a researcher understands the factors and/or variables that are involved in the study and their relationships to one another. The purpose of a conceptual framework is to articulate the concepts under study using relevant literature ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ) and to clarify the presumed relationships among those concepts ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Conceptual frameworks are different from theoretical frameworks in both their breadth and grounding in established findings. Whereas a theoretical framework articulates the lens through which a researcher views the work, the conceptual framework is often more mechanistic and malleable.

Conceptual frameworks are broader, encompassing both established theories (i.e., theoretical frameworks) and the researchers’ own emergent ideas. Emergent ideas, for example, may be rooted in informal and/or unpublished observations from experience. These emergent ideas would not be considered a “theory” if they are not yet tested, supported by systematically collected evidence, and peer reviewed. However, they do still play an important role in the way researchers approach their studies. The conceptual framework allows authors to clearly describe their emergent ideas so that connections among ideas in the study and the significance of the study are apparent to readers.

Constructing Conceptual Frameworks

Including a conceptual framework in a research study is important, but researchers often opt to include either a conceptual or a theoretical framework. Either may be adequate, but both provide greater insight into the research approach. For instance, a research team plans to test a novel component of an existing theory. In their study, they describe the existing theoretical framework that informs their work and then present their own conceptual framework. Within this conceptual framework, specific topics portray emergent ideas that are related to the theory. Describing both frameworks allows readers to better understand the researchers’ assumptions, orientations, and understanding of concepts being investigated. For example, Connolly et al. (2018) included a conceptual framework that described how they applied a theoretical framework of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) to their study on teaching programs for doctoral students. In their conceptual framework, the authors described SCCT, explained how it applied to the investigation, and drew upon results from previous studies to justify the proposed connections between the theory and their emergent ideas.

In some cases, authors may be able to sufficiently describe their conceptualization of the phenomenon under study in an introduction alone, without a separate conceptual framework section. However, incomplete descriptions of how the researchers conceptualize the components of the study may limit the significance of the study by making the research less intelligible to readers. This is especially problematic when studying topics in which researchers use the same terms for different constructs or different terms for similar and overlapping constructs (e.g., inquiry, teacher beliefs, pedagogical content knowledge, or active learning). Authors must describe their conceptualization of a construct if the research is to be understandable and useful.

There are some key areas to consider regarding the inclusion of a conceptual framework in a study. To begin with, it is important to recognize that conceptual frameworks are constructed by the researchers conducting the study ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Maxwell, 2012 ). This is different from theoretical frameworks that are often taken from established literature. Researchers should bring together ideas from the literature, but they may be influenced by their own experiences as a student and/or instructor, the shared experiences of others, or thought experiments as they construct a description, model, or representation of their understanding of the phenomenon under study. This is an exercise in intellectual organization and clarity that often considers what is learned, known, and experienced. The conceptual framework makes these constructs explicitly visible to readers, who may have different understandings of the phenomenon based on their prior knowledge and experience. There is no single method to go about this intellectual work.

Reeves et al. (2016) is an example of an article that proposed a conceptual framework about graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. The authors used existing literature to create a novel framework that filled a gap in current research and practice related to the training of graduate teaching assistants. This conceptual framework can guide the systematic collection of data by other researchers because the framework describes the relationships among various factors that influence teaching and learning. The Reeves et al. (2016) conceptual framework may be modified as additional data are collected and analyzed by other researchers. This is not uncommon, as conceptual frameworks can serve as catalysts for concerted research efforts that systematically explore a phenomenon (e.g., Reynolds et al. , 2012 ; Brownell and Kloser, 2015 ).

Sabel et al. (2017) used a conceptual framework in their exploration of how scaffolds, an external factor, interact with internal factors to support student learning. Their conceptual framework integrated principles from two theoretical frameworks, self-regulated learning and metacognition, to illustrate how the research team conceptualized students’ use of scaffolds in their learning ( Figure 1 ). Sabel et al. (2017) created this model using their interpretations of these two frameworks in the context of their teaching.

Conceptual framework from Sabel et al. (2017) .

A conceptual framework should describe the relationship among components of the investigation ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). These relationships should guide the researcher’s methods of approaching the study ( Miles et al. , 2014 ) and inform both the data to be collected and how those data should be analyzed. Explicitly describing the connections among the ideas allows the researcher to justify the importance of the study and the rigor of the research design. Just as importantly, these frameworks help readers understand why certain components of a system were not explored in the study. This is a challenge in education research, which is rooted in complex environments with many variables that are difficult to control.

For example, Sabel et al. (2017) stated: “Scaffolds, such as enhanced answer keys and reflection questions, can help students and instructors bridge the external and internal factors and support learning” (p. 3). They connected the scaffolds in the study to the three dimensions of metacognition and the eventual transformation of existing ideas into new or revised ideas. Their framework provides a rationale for focusing on how students use two different scaffolds, and not on other factors that may influence a student’s success (self-efficacy, use of active learning, exam format, etc.).

In constructing conceptual frameworks, researchers should address needed areas of study and/or contradictions discovered in literature reviews. By attending to these areas, researchers can strengthen their arguments for the importance of a study. For instance, conceptual frameworks can address how the current study will fill gaps in the research, resolve contradictions in existing literature, or suggest a new area of study. While a literature review describes what is known and not known about the phenomenon, the conceptual framework leverages these gaps in describing the current study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). In the example of Sabel et al. (2017) , the authors indicated there was a gap in the literature regarding how scaffolds engage students in metacognition to promote learning in large classes. Their study helps fill that gap by describing how scaffolds can support students in the three dimensions of metacognition: intelligibility, plausibility, and wide applicability. In another example, Lane (2016) integrated research from science identity, the ethic of care, the sense of belonging, and an expertise model of student success to form a conceptual framework that addressed the critiques of other frameworks. In a more recent example, Sbeglia et al. (2021) illustrated how a conceptual framework influences the methodological choices and inferences in studies by educational researchers.

Sometimes researchers draw upon the conceptual frameworks of other researchers. When a researcher’s conceptual framework closely aligns with an existing framework, the discussion may be brief. For example, Ghee et al. (2016) referred to portions of SCCT as their conceptual framework to explain the significance of their work on students’ self-efficacy and career interests. Because the authors’ conceptualization of this phenomenon aligned with a previously described framework, they briefly mentioned the conceptual framework and provided additional citations that provided more detail for the readers.

Within both the BER and the broader DBER communities, conceptual frameworks have been used to describe different constructs. For example, some researchers have used the term “conceptual framework” to describe students’ conceptual understandings of a biological phenomenon. This is distinct from a researcher’s conceptual framework of the educational phenomenon under investigation, which may also need to be explicitly described in the article. Other studies have presented a research logic model or flowchart of the research design as a conceptual framework. These constructions can be quite valuable in helping readers understand the data-collection and analysis process. However, a model depicting the study design does not serve the same role as a conceptual framework. Researchers need to avoid conflating these constructs by differentiating the researchers’ conceptual framework that guides the study from the research design, when applicable.

Explicitly describing conceptual frameworks is essential in depicting the focus of the study. We have found that being explicit in a conceptual framework means using accepted terminology, referencing prior work, and clearly noting connections between terms. This description can also highlight gaps in the literature or suggest potential contributions to the field of study. A well-elucidated conceptual framework can suggest additional studies that may be warranted. This can also spur other researchers to consider how they would approach the examination of a phenomenon and could result in a revised conceptual framework.

It can be challenging to create conceptual frameworks, but they are important. Below are two resources that could be helpful in constructing and presenting conceptual frameworks in educational research:

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Chapter 3 in this book describes how to construct conceptual frameworks.

- Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2016). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book explains how conceptual frameworks guide the research questions, data collection, data analyses, and interpretation of results.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks are all important in DBER and BER. Robust literature reviews reinforce the importance of a study. Theoretical frameworks connect the study to the base of knowledge in educational theory and specify the researcher’s assumptions. Conceptual frameworks allow researchers to explicitly describe their conceptualization of the relationships among the components of the phenomenon under study. Table 1 provides a general overview of these components in order to assist biology education researchers in thinking about these elements.

It is important to emphasize that these different elements are intertwined. When these elements are aligned and complement one another, the study is coherent, and the study findings contribute to knowledge in the field. When literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks are disconnected from one another, the study suffers. The point of the study is lost, suggested findings are unsupported, or important conclusions are invisible to the researcher. In addition, this misalignment may be costly in terms of time and money.

Conducting a literature review, selecting a theoretical framework, and building a conceptual framework are some of the most difficult elements of a research study. It takes time to understand the relevant research, identify a theoretical framework that provides important insights into the study, and formulate a conceptual framework that organizes the finding. In the research process, there is often a constant back and forth among these elements as the study evolves. With an ongoing refinement of the review of literature, clarification of the theoretical framework, and articulation of a conceptual framework, a sound study can emerge that makes a contribution to the field. This is the goal of BER and education research.

Supplementary Material

- Allee, V. (2000). Knowledge networks and communities of learning . OD Practitioner , 32 ( 4 ), 4–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen, M. (2017). The Sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1–4 ). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. 10.4135/9781483381411 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2011). Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: A call to action . Washington, DC. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anfara, V. A., Mertz, N. T. (2014). Setting the stage . In Anfara, V. A., Mertz, N. T. (eds.), Theoretical frameworks in qualitative research (pp. 1–22). Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barnes, M. E., Brownell, S. E. (2016). Practices and perspectives of college instructors on addressing religious beliefs when teaching evolution . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 15 ( 2 ), ar18. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-11-0243 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boote, D. N., Beile, P. (2005). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation . Educational Researcher , 34 ( 6 ), 3–15. 10.3102/0013189x034006003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]