What Are Cancer Research Studies?

What is cancer research and why is it important.

Research is the key to progress against cancer and is a complex process involving professionals from many fields. It is also thanks to the participation of people with cancer, cancer survivors, and healthy volunteers that any breakthroughs go on to improve treatment and care for those who need it.

Cancer research studies may lead to discoveries such as new drugs to treat cancer, new therapies to make symptoms less severe, or lifestyle changes to reduce the chances of getting cancer.

Cancer research may also address big picture questions like why cancer is more prevalent in certain populations or how doctors can make existing cancer detection tools more effective in health care settings.

These discoveries can help people with cancer and their caregivers live fuller lives.

Who should join cancer research studies?

When you choose to participate in a research study, you become a partner in scientific discovery. Your generous contribution can make a world of difference for people like you.

As scientists continue to conduct cancer research, anyone can consider joining a research study. The best research includes everyone, and everyone includes you.

Your unique experience with cancer is incredibly valuable and may help current and future generations lead healthier lives.

When more people of all different races, ethnicities, ages, genders, abilities, and backgrounds participate, more people benefit.

It is important for scientists to capture the full genetic diversity of human populations so that the lessons learned are applicable to everyone.

What are the types of cancer research studies?

See below for definitions on the four major types of research and their subtypes:

- basic research

- quality of life/supportive care

- natural history

- longitudinal

- population-based

- epidemiological research

- translational research

Basic Research

Basic cancer research studies explore the very laws of nature. Scientists learn how cancer cells grow and divide, for example, by growing and testing bacteria , viruses , fungi , animal cells, and human cells in a lab. Scientists also study, for example, the genes that make up tumors in mice and rats in the lab. These experiments help build the foundation for further discovery.

Why Participate in a Clinical Trial?

Get information on how to evaluate a clinical trial and what questions to ask.

Clinical Research

Clinical research involves the study of cancer in people. These cancer research studies are further broken down into two types: clinical trials and observational studies .

- Treatment trials test how safe and useful a new treatment or way of using existing treatments is for people with cancer. Test treatments may include drugs, approaches to surgery or radiation therapy , or combinations of treatments.

- Prevention trials are for people who do not have cancer but are at a high risk for developing cancer or for cancer coming back. Prevention clinical trials target lifestyle changes (doing something) or focus on certain nutrients or medicines (adding something).

- Screening trials test how effective screening tests are for healthy people. The goal of these trials is to discover screening tools or methods that reduce deaths from cancer by finding it earlier.

- Quality-of-life/supportive care tests aim to help people with cancer, as well as their family and loved ones, cope with side effects like pain, nutrition problems, nausea and vomiting , sleeping problems, and depression . These trials may involve drugs or activities like therapy and exercising.

Find Observation Studies >

View a studies that are looking for people now.

- Natural history studies look at certain conditions in people with cancer or people who are at a high risk of developing cancer. Researchers often collect information about a person and their family medical history , as well as blood, saliva, and tumor samples. For example, a biomarker test may be used to get a genetic profile of a person’s cancer tissue. This may reveal how certain tumors change over the course of treatment .

- Longitudinal studies gather data on people or groups of people over time, often to see the result of a habit, treatment, or change. For example, two groups of people may be identified as those who smoke and those who do not. These two groups are compared over time to see whether one group is more likely to develop cancer than the other group.

- Population-based studies explore the causes of cancer, cancer trends, and factors that affect cancer care in specific populations. For example, a population-based study may explore the causes of a high cancer rate in a regional Native American population.

Epidemiological Research

Epidemiological research is the study of the patterns, causes, and effects of cancer in a group of people of a certain background. This research encompasses both observational population-based studies but also includes clinical epidemiological studies where the relationship between a population’s risk factors and treatments are tested.

Translational Research

Translational research is when cancer research moves across research disciplines, from basic lab research into clinical settings, and from clinical settings into everyday care. In turn, findings from clinical studies and population-based studies can inform basic cancer research. For example, data from the genetic profile of a tumor during an observational study may help scientists develop a clinical trial to test which drugs to prescribe to cancer patients with specific tumor genes.

Monica Bertagnolli, Director, NIH; former director, NCI; cancer survivor

Participation in Cancer Research Matters

I am so happy to have the opportunity to acknowledge the courage and generosity of an estimated 494,018 women who agreed to participate in randomized clinical trials with results reported between 1971 and 2018.

Their contributions showed that mammography can detect cancer at an early stage, that mastectomies and axillary lymph node dissections are not always necessary, that chemotherapy can benefit some people with early estrogen receptor–positive, progesterone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer but is not needed for all, and that hormonal therapy can prevent disease recurrence.

For just the key studies that produced these results, it took the strength and commitment of almost 500,000 women. I am the direct beneficiary of their contributions, and I am profoundly grateful.

The true number of brave souls contributing to this reduction in breast cancer mortality over the past 30 years? Many millions. These are our heroes.

— From NCI Director’s Remarks by then-NCI Director Monica M. Bertagnolli, M.D., at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, June 3, 2023

- News and Features

- Conferences

Clinical Tools

- Special Collections

- Breast Cancer

Gynecologic Cancer

- General Oncology

- General Medicine

Latest News

- Post-Recurrence Treatment Data Lacking in Cancer Trials

- Substituting Lower-Wage Staff for Registered Nurses Tied to Worse Outcomes

- Drug Shortages Still Affecting US Cancer Centers, Survey Shows

- Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib Provides Some Long-Term Benefits in Melanoma

- Acupuncture Reduces Endocrine Symptoms, Hot Flashes in Breast Cancer

- Black Patients More Likely to Experience MACE After ADT for Prostate Cancer

- Krazati Plus Cetuximab Approved for KRAS G12C-Mutated Advanced Colorectal Cancer

- Ready-to-Use Formulation of Akynzeo Now Available

- Taming the Flames of Burnout in Oncology

- Gastroesophageal cancers: Trying to outfox a “tricky entity”

- Surveillance IDs New Tumors in Children With Cancer Predisposition

- Nearly 1 in 4 Do Not Recover From COVID-19 by 90 Days

Latest Features

Conference Coverage

Featured Conference

- Bladder, kidney, and other urologic cancers

- Bone and connective tissue cancer

- Breast cancer

- CNS cancers

- Colorectal and other GI cancers

- Cytoprotective and supportive care agents

- Gynecologic Cancers

- Head and neck cancer

- Kaposi's sarcoma

- Leukemias, lymphomas, and other hematologic cancers

- Melanoma and other skin cancers

- Pancreatic, thyroid, and other endocrine cancers

- Prostate and other male cancers

- Respiratory and thoracic cancers

- Solid tumors

Ritux 3 Regimen Provides Patients With Pemphigus With Sustained Remission

Efficacy of a Co-Located Bridging Recovery Initiative for Opioid Use Disorder

US Oncologists, Hematologists Receive More Industry Payments Than Their Peers

FDA Withdraws Approval of Pepaxto for Multiple Myeloma

PIDS Updates Guidance on COVID-19 Management in Children, Adolescents

- Bladder Cancer

- Central Nervous System Cancers

- Endocrine Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Head and Neck Cancers

- Hematologic Cancers

- Lung Cancer

- Pediatric Cancer

- Prostate Cancer

- Renal Cell Carcinoma

- Skin Cancers

Cases and Controls

A case-control study compares two groups of people: those with the cancer under study (cases) and those who do not have the cancer (controls). Researchers compare the genetic, environmental, lifestyle, and medical histories of the people in the two groups to identify factors associated with cancer.

Selected examples of DCEG case-control studies:

AsiaLymph , an international hospital-based case-control study of lymphoma among Chinese in Eastern Asia to replicate and extend recent and novel observations made in studies of White populations with distinctly different patterns of environmental and occupational risk factors and genetic loci.

African Esophageal Cancer Consortium (AfrECC) facilitates collaborations to coordinate etiologic and molecular studies of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in East Africa.

Breast, Ovary and Endometrial Cancer Studies in Poland

- Ovarian and Endometrial Cancer Case-Control Study in Poland was conducted among female residents of Warsaw and Lodz (Poland) between 2001 and 2003. Current projects include methylation profiling, tumor gene sequencing, microsatellite instability analysis, and immunohistochemistry to study the etiologic heterogeneity of endometrial and ovarian cancers.

Case-control Studies of Renal Cell Cancer

- Renal Cell Cancer among White and African American Adults in the United States , conducted in the metropolitan areas of Detroit and Chicago in collaboration with Wayne State University and the University of Illinois at Chicago. The aims of this study are to evaluate risk factors for renal cell cancer and examine why rates of this disease are higher among U.S. Black adults than White adults.

- Renal Cell Cancer in Eastern Europe , conducted from 1999 to 2003 in collaboration with the International Agency for Research on Cancer to evaluate kidney cancer risks in relation to occupational and other environmental and lifestyle exposures in six centers across Eastern Europe. Factors being evaluated include occupational exposures, lifestyle factors, medical conditions, markers of genetic susceptibility, and tumor molecular characteristics.

The DETECT Study – Discovery and Evaluation of Testing for Endometrial Cancer in Tampons , a partnership with the University of Alabama Birmingham to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of self-sampling with vaginal tampons for endometrial cancer detection in a racially-diverse population of women undergoing hysterectomy.

Environment And Genetics in Lung cancer Etiology (EAGLE) is a large population-based case-control study designed and conducted to investigate the genetic and environmental determinants of lung cancer and smoking persistence using an integrative approach that allows combined analysis of genetic, environmental, clinical, and behavioral data.

Epidemiology of Burkitt Lymphoma in East African Children and Minors (EMBLEM) , a large, multidisciplinary epidemiological effort designed to evaluate environmental and host factors associated with childhood Burkitt lymphoma in sub-Saharan Africa.

Nasopharyngeal Case-Control Study , conducted in Taiwan between 1991-1994 and 2010-2014, examines the role of viral, environmental, and genetic factors associated with the development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Factors investigated include Epstein-Barr virus, diet, smoking, occupation, HLA, and other genetic polymorphisms.

NCI-SEER Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) Case-Control Study , a multi-center, population-based study of 1,321 NHL cases and 1,057 controls that includes detailed interview data, biospecimens, and environmental samples.

New England Bladder Cancer Study , a population-based, case-control study of bladder cancer in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine, is designed to explain the reasons for the persistent excess of rates of bladder cancer in the northern New England area. Investigators collected data on 2,600 participants via personal interviews, biological samples (blood, buccal cells, urine, toenails, and tumor tissue), as well as drinking water samples.

Testicular Cancer among Military Servicemen: the STEED Study , a case-control study of testicular cancer among military servicemen. The project includes obtaining biosamples and questionnaire data from all participants. Pre-diagnostic serum samples are available from the approximately 1,100 cases and 1,100 controls enrolled in the study.

COVID-19 Resources

What people with cancer should know: https://www.cancer.gov/coronavirus

Guidance for cancer researchers: https://www.cancer.gov/coronavirus-researchers

Get the latest public health information from CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus

Get the latest research information from NIH: https://www.covid19.nih.gov

Help us improve EBCCP and other cancer control resources on Cancer Control P.L.A.N.E.T.

Help us improve EBCCP

- Teach with EBCCP

EBCCP Case Studies for Teaching

Designed specifically for public health instructors, EBCCP Case Studies for Teaching provide structured learning opportunities that facilitate students' development of public health competencies related to research, evaluation, and implementation science. The first case study focuses on evaluation of research evidence for implementation. Additional case studies are under development.

Available materials for each case include

- Instructor's guide indicating competencies addressed, and complete instructions

- Student's guide with instruction and activity worksheet

- Instructor's presentation "When is a Public Health Intervention Evidence-Based Enough for Broader Implementation?" with speaker notes to set up the activity

- Instructor's answer key to student activity

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Different study designs in the epidemiology of cancer: case-control vs. cohort studies

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

- PMID: 19109782

- DOI: 10.1007/978-1-59745-416-2_11

It is only since the 1950s that most of the epidemiology studies on cancer have been conducted. The principal study designs for epidemiologic study of cancer etiology are case-control and cohort studies. These study designs have complimentary roles and distinct advantages and disadvantages. This chapter provides historical perspectives, description of the traditional and variant designs of case-control and cohort studies, and the relative advantages and disadvantages of these study designs.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Methods in epidemiology: observational study designs. DiPietro NA. DiPietro NA. Pharmacotherapy. 2010 Oct;30(10):973-84. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.10.973. Pharmacotherapy. 2010. PMID: 20874034 Review.

- Statistical methods in cancer epidemiological studies. Xue X, Hoover DR. Xue X, et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;471:239-72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-416-2_13. Methods Mol Biol. 2009. PMID: 19109784

- [Common study designs in epidemiology]. Klug SJ, Bender R, Blettner M, Lange S. Klug SJ, et al. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007;132 Suppl 1:e45-7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-959041. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007. PMID: 17530597 German. No abstract available.

- Four different study designs to evaluate vaccine safety were equally validated with contrasting limitations. Glanz JM, McClure DL, Xu S, Hambidge SJ, Lee M, Kolczak MS, Kleinman K, Mullooly JP, France EK. Glanz JM, et al. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Aug;59(8):808-18. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.11.012. Epub 2006 Mar 15. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006. PMID: 16828674

- Logistics and design issues in the use of biological samples in observational epidemiology. Potter JD. Potter JD. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;(142):31-7. IARC Sci Publ. 1997. PMID: 9354909 Review.

- Diets, Dietary Patterns, Single Foods and Pancreatic Cancer Risk: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Gianfredi V, Ferrara P, Dinu M, Nardi M, Nucci D. Gianfredi V, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Nov 10;19(22):14787. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214787. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 36429506 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 19 June 2024

Why do patients with cancer die?

- Adrienne Boire ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9029-1248 1 na1 ,

- Katy Burke 2 na1 ,

- Thomas R. Cox ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9294-1745 3 , 4 na1 ,

- Theresa Guise 5 na1 ,

- Mariam Jamal-Hanjani 6 , 7 , 8 na1 ,

- Tobias Janowitz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7820-3727 9 , 10 na1 ,

- Rosandra Kaplan 11 na1 ,

- Rebecca Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2540-2009 12 , 13 na1 ,

- Charles Swanton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4299-3018 7 , 8 , 14 na1 ,

- Matthew G. Vander Heiden ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6702-4192 15 , 16 na1 &

- Erik Sahai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3932-5086 12 na1

Nature Reviews Cancer ( 2024 ) Cite this article

6638 Accesses

1 Citations

447 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer models

- Cancer therapy

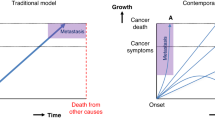

Cancer is a major cause of global mortality, both in affluent countries and increasingly in developing nations. Many patients with cancer experience reduced life expectancy and have metastatic disease at the time of death. However, the more precise causes of mortality and patient deterioration before death remain poorly understood. This scarcity of information, particularly the lack of mechanistic insights, presents a challenge for the development of novel treatment strategies to improve the quality of, and potentially extend, life for patients with late-stage cancer. In addition, earlier deployment of existing strategies to prolong quality of life is highly desirable. In this Roadmap, we review the proximal causes of mortality in patients with cancer and discuss current knowledge about the interconnections between mechanisms that contribute to mortality, before finally proposing new and improved avenues for data collection, research and the development of treatment strategies that may improve quality of life for patients.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The changing landscape of cancer in the USA — opportunities for advancing prevention and treatment

Causes of death among people living with metastatic cancer

Deceptive measures of progress in the NHS long-term plan for cancer: case-based vs. population-based measures

Dillekås, H., Rogers, M. S. & Straume, O. Are 90% of deaths from cancer caused by metastases? Cancer Med. 8 , 5574–5576 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Seyfried, T. N. & Huysentruyt, L. C. On the origin of cancer metastasis. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 18 , 43–73 (2013).

Schnurman, Z. et al. Causes of death in patients with brain metastases. Neurosurgery 93 , 986–993 (2023).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gallardo-Valverde, J. M. et al. Obstruction in patients with colorectal cancer increases morbidity and mortality in association with altered nutritional status. Nutr. Cancer 53 , 169–176 (2005).

Swanton, C. et al. Embracing cancer complexity: hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell 187 , 1589–1616 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wheatley-Price, P., Blackhall, F. & Thatcher, N. The influence of sex in non-small cell lung cancer. Onkologie 32 , 547–548 (2009).

Abu-Sbeih, H. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with preexisting inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 38 , 576 (2020).

Neugut, A. I. et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and survival among the elderly. J. Clin. Oncol. 24 , 2368–2375 (2006).

Sullivan, D. R. et al. Association of early palliative care use with survival and place of death among patients with advanced lung cancer receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Oncol. 5 , 1702–1709 (2019).

Sallnow, L. et al. Report of the Lancet Commission on the value of death: bringing death back into life. Lancet 399 , 837–884 (2022).

Abdel-Karim, I. A., Sammel, R. B. & Prange, M. A. Causes of death at autopsy in an inpatient hospice program. J. Palliat. Med. 10 , 894–898 (2007).

Pautex, S. et al. Anatomopathological causes of death in patients with advanced cancer: association with the use of anticoagulation and antibiotics at the end of life. J. Palliat. Med. 16 , 669–674 (2013).

Khorana, A. A., Francis, C. W., Culakova, E., Kuderer, N. M. & Lyman, G. H. Thromboembolism is a leading cause of death in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5 , 632–634 (2007).

Levi, M. & Scully, M. How I treat disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood 131 , 845–854 (2018).

Cines, D. B., Liebman, H. & Stasi, R. Pathobiology of secondary immune thrombocytopenia. Semin. Hematol. 46 , S2 (2009).

Ghanavat, M. et al. Thrombocytopenia in solid tumors: prognostic significance. Oncol. Rev. 13 , 43–48 (2019).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anker, M. S. et al. Advanced cancer is also a heart failure syndrome: a hypothesis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12 , 533 (2021).

Asdahl, P. H. et al. Cardiovascular events in cancer patients with bone metastases — a Danish population-based cohort study of 23,113 patients. Cancer Med. 10 , 4885–4895 (2021).

Sinn, D. H. et al. Different survival of Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage C hepatocellular carcinoma patients by the extent of portal vein invasion and the type of extrahepatic spread. PLoS ONE 10 , e0124434 (2015).

Zisman, A. et al. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus extension: biology, role of nephrectomy and response to immunotherapy. J. Urol. 169 , 909–916 (2003).

Suárez, C. et al. Carotid blowout syndrome: modern trends in management. Cancer Manag. Res. 10 , 5617 (2018).

Lin, A. L. & Avila, E. K. Neurologic emergencies in the cancer patient: diagnosis and management. J. Intensive Care Med. 32 , 99 (2017).

Gamburg, E. S. et al. The prognostic significance of midline shift at presentation on survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 48 , 1359–1362 (2000).

Mokri, B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology 56 , 1746–1748 (2001).

Mastall, M. et al. Survival of brain tumour patients with epilepsy. Brain 144 , 3322–3327 (2021).

Steindl, A. et al. Neurological symptom burden impacts survival prognosis in patients with newly diagnosed non-small cell lung cancer brain metastases. Cancer 126 , 4341–4352 (2020).

Girard, N. et al. Comprehensive histologic assessment helps to differentiate multiple lung primary nonsmall cell carcinomas from metastases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 33 , 1752–1764 (2009).

Lee, P. et al. Metabolic tumor burden predicts for disease progression and death in lung cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 69 , 328–333 (2007).

Kookoolis, A. S., Puchalski, J. T., Murphy, T. E., Araujo, K. L. & Pisani, M. A. Mortality of hospitalized patients with pleural effusions. J. Pulm. Respir. Med. 4 , 184 (2014).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cousins, S. E., Tempest, E. & Feuer, D. J. Surgery for the resolution of symptoms in malignant bowel obstruction in advanced gynaecological and gastrointestinal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev . https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002764 (2016).

Baker, M. L. et al. Mortality after acute kidney injury and acute interstitial nephritis in patients prescribed immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 10 , e004421 (2022).

Bhave, P., Buckle, A., Sandhu, S. & Sood, S. Mortality due to immunotherapy related hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 69 , 976–978 (2018).

Lameire, N. H., Flombaum, C. D., Moreau, D. & Ronco, C. Acute renal failure in cancer patients. Ann. Med. 37 , 13–25 (2005).

Ries, F. & Klastersky, J. Nephrotoxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy with special emphasis on cisplatin toxicity. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 8 , 368–379 (1986).

Wong, J. L. & Evans, S. E. Bacterial pneumonia in patients with cancer: novel risk factors and management. Clin. Chest Med. 38 , 263–277 (2017).

Lee, L. Y. W. et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 395 , 1919–1926 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Williamson, E. J. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584 , 430–436 (2020). This study used a platform of 17.4 million pseudo-anonymized health-care records to determine risk factors for COVID-19.

Pelosof, L. C. & Gerber, D. E. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85 , 838–854 (2010).

Donovan, P. J. et al. PTHrP-mediated hypercalcemia: causes and survival in 138 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100 , 2024–2029 (2015).

Burtis, W. J. et al. Immunochemical characterization of circulating parathyroid hormone-related protein in patients with humoral hypercalcemia of cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 322 , 1106–1112 (1990). First study to show that patients with cancer-associated hypercalcaemia had elevated concentrations of plasma parathyroid hormone-related protein .

Ellison, D. H. & Berl, T. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356 , 2064–2072 (2007).

Okabayashi, T. et al. Diagnosis and management of insulinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 19 , 829–837 (2013).

Giometto, B. et al. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome in the PNS Euronetwork database: a European study from 20 centers. Arch. Neurol. 67 , 330–335 (2010).

Wang, D. Y. et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 4 , 1721 (2018).

Feng, S. et al. Pembrolizumab-induced encephalopathy: a review of neurological toxicities with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12 , 1626–1635 (2017).

Coustal, C. et al. Prognosis of immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced myocarditis: a case series. J. Immunother. Cancer 11 , e004792 (2023).

Kuderer, N. M., Dale, D. C., Crawford, J., Cosler, L. E. & Lyman, G. H. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer 106 , 2258–2266 (2006).

Agarwal, M. A. et al. Ventricular arrhythmia in cancer patients: mechanisms, treatment strategies and future avenues. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. Rev . 12 , e16 (2023).

Zafar, A. et al. The incidence, risk factors, and outcomes with 5-fluorouracil-associated coronary vasospasm. JACC CardioOncol. 3 , 101–109 (2021).

Polk, A. et al. Incidence and risk factors for capecitabine-induced symptomatic cardiotoxicity: a retrospective study of 452 consecutive patients with metastatic breast cancer. BMJ Open 6 , e012798 (2016).

Safdar, A., Bodey, G. & Armstrong, D. Infections in patients with cancer: overview. Princip. Pract. Cancer Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-644-3_1 (2011).

Foster, D. S., Jones, R. E., Ransom, R. C., Longaker, M. T. & Norton, J. A. The evolving relationship of wound healing and tumor stroma. JCI Insight 3 , e99911 (2018).

Park, S. J. & Bejar, R. Clonal hematopoiesis in cancer. Exp. Hematol. 83 , 105 (2020).

Liebman, H. A. Thrombocytopenia in cancer patients. Thromb. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-3848(14)50011-4 (2014).

Chakraborty, R. et al. Characterisation and prognostic impact of immunoparesis in relapsed multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 189 , 1074–1082 (2020).

Allen, B. M. et al. Systemic dysfunction and plasticity of the immune macroenvironment in cancer models. Nat. Med. 26 , 1125–1134 (2020).

Munn, D. H. & Bronte, V. Immune suppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 39 , 1–6 (2016).

Kochar, R. & Banerjee, S. Infections of the biliary tract. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 23 , 199–218 (2013).

Valvani, A., Martin, A., Devarajan, A. & Chandy, D. Postobstructive pneumonia in lung cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 7 , 357–357 (2019).

Rolston, K. V. I. Infections in cancer patients with solid tumors: a review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 6 , 69–83 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. The association between major complications of immobility during hospitalization and quality of life among bedridden patients: a 3 month prospective multi-center study. PLoS One 13 , e0205729 (2018).

The clinicopathological and prognostic role of thrombocytosis in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett . 13 , 5002–5008 (2017).

Kasthuri, R. S., Taubman, M. B. & Mackman, N. Role of tissue factor in cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 27 , 4834 (2009).

Wade, J. C. Viral infections in patients with hematological malignancies. Hematology 2006 , 368–374 (2006).

Article Google Scholar

Ersvaer, E., Liseth, K., Skavland, J., Gjertsen, B. T. & Bruserud, Ø. Intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia differentially affects circulating TC1, TH1, TH17 and TREG cells. BMC Immunol. 11 , 1–12 (2010).

Kuter, D. J. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia in patients with non-hematologic malignancies. Haematologica 107 , 1243 (2022).

Rodgers, G. M. et al. Cancer- and chemotherapy-induced anemia. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 10 , 628–653 (2012).

Nesher, L. & Rolston, K. V. I. The current spectrum of infection in cancer patients with chemotherapy related neutropenia. Infection 42 , 5–13 (2014).

Blijlevens, N. M. A., Logan, R. M. & Netea, M. G. Mucositis: from febrile neutropenia to febrile mucositis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63 , i36–i40 (2009).

Petrelli, F. et al. Association of steroid use with survival in solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 141 , 105–114 (2020).

Bolton, K. L. et al. Cancer therapy shapes the fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis. Nat. Genet. 52 , 1219–1226 (2020). This study identified the molecular characteristics of clonal haematopoiesis that increased risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, with different characteristics associated with different treatment exposures.

Bhatia, R. et al. Do cancer and cancer treatments accelerate aging? Curr. Oncol. Rep. 24 , 1401 (2022).

Eisenstein, T. K. The role of opioid receptors in immune system function. Front. Immunol. 10 , 485158 (2019).

Böll, B. et al. Central venous catheter-related infections in hematology and oncology: 2020 updated guidelines on diagnosis, management, and prevention by the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann. Hematol. 100 , 239 (2021).

Ruiz-Giardin, J. M. et al. Blood stream infections associated with central and peripheral venous catheters. BMC Infect. Dis. 19 , 1–9 (2019).

Lee, D. W. et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood 124 , 188–195 (2014).

Brahmer, J. R. et al. Safety profile of pembrolizumab monotherapy based on an aggregate safety evaluation of 8937 patients. Eur. J. Cancer 199 , 113530 (2024). Analysis of the toxicity profile of anti-PD1 therapy in more than 8,000 patients.

Larkin, J. et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 , 1535–1546 (2019).

Vozy, A. et al. Increased reporting of fatal hepatitis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur. J. Cancer 123 , 112–115 (2019).

Palaskas, N., Lopez-Mattei, J., Durand, J. B., Iliescu, C. & Deswal, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis: pathophysiological characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9 , e013757 (2020).

Janssen, J. B. E. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related Guillain–Barré syndrome: a case series and review of the literature. J. Immunother. 44 , 276–282 (2021).

Camelliti, S. et al. Mechanisms of hyperprogressive disease after immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: what we (don’t) know. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39 , 236 (2020).

Kitamura, W. et al. Bone marrow microenvironment disruption and sustained inflammation with prolonged haematologic toxicity after CAR T-cell therapy. Br. J. Haematol. 202 , 294–307 (2023).

Seano, G. et al. Solid stress in brain tumours causes neuronal loss and neurological dysfunction and can be reversed by lithium. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 3 , 230 (2019).

Madhusoodanan, S., Ting, M. B., Farah, T. & Ugur, U. Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: a review. World J. Psychiatry 5 , 273 (2015).

Gerstenecker, A. et al. Cognition in patients with newly diagnosed brain metastasis: profiles and implications. J. Neurooncol. 120 , 179 (2014).

Krishna, S. et al. Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature 617 , 599–607 (2023). This study demonstrated that high-grade gliomas remodel neural circuits in the human brain, which promotes tumour progression and impairs cognition.

Taylor, K. R. et al. Glioma synapses recruit mechanisms of adaptive plasticity. Nature 623 , 366–374 (2023). This study showed that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)–tropomyosin-related kinase B (TRKB) signalling promotes malignant synaptic plasticity and augments tumour progression.

Hanahan, D. & Monje, M. Cancer hallmarks intersect with neuroscience in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 41 , 573–580 (2023).

Ahles, T. A. & Root, J. C. Cognitive effects of cancer and cancer treatments. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol . 14 , 425–451 (2018).

Allexandre, D. et al. EEG correlates of central origin of cancer-related fatigue. Neural Plast. 2020 , 8812984 (2020).

Büttner-Teleagă, A., Kim, Y. T., Osel, T. & Richter, K. Sleep disorders in cancer — a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 , 11696 (2021).

Walsh, D. & Nelson, K. A. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 10 , 523–528 (2002).

Ghandour, F. et al. Presenting psychiatric and neurological symptoms and signs of brain tumors before diagnosis: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 11 , 1–20 (2021).

Akechi, T. et al. Somatic symptoms for diagnosing major depression in cancer patients. Psychosomatics 44 , 244–248 (2003).

Nho, J. H., Kim, S. R. & Kwon, Y. S. Depression and appetite: predictors of malnutrition in gynecologic cancer. Support. Care Cancer 22 , 3081–3088 (2014).

Thaker, P. H. et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Med. 12 , 939–944 (2006). This study linked chronic behavioural stress to higher levels of tissue catecholamines and tumour angiogenesis, resulting in greater tumor burden and invasion in ovarian cancer.

Chang, A. et al. Beta-blockade enhances anthracycline control of metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Sci. Transl. Med . 15 , eadf1147 (2023).

Magnon, C. et al. Autonomic nerve development contributes to prostate cancer progression. Science 341 , 1236361 (2013). This study showed that the formation of autonomic nerve fibres in the prostate gland regulates prostate cancer development and dissemination in mouse models.

Baracos, V. E., Martin, L., Korc, M., Guttridge, D. C. & Fearon, K. C. H. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 4 , 17105 (2018).

Fearon, K. et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 12 , 489–495 (2011). International consensus definitions of cancer cachexia.

Bossi, P., Delrio, P., Mascheroni, A. & Zanetti, M. The spectrum of malnutrition/cachexia/sarcopenia in oncology according to different cancer types and settings: a narrative review. Nutrients 13 , 1980 (2021).

Farkas, J. et al. Cachexia as a major public health problem: frequent, costly, and deadly. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 4 , 173–178 (2013).

Dennison, E. M., Sayer, A. A. & Cooper, C. Epidemiology of sarcopenia and insight into possible therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13 , 340–347 (2017).

Farasat, M. et al. Long-term cardiac arrhythmia and chronotropic evaluation in patients with severe anorexia nervosa (LACE-AN): a pilot study. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 31 , 432–439 (2020).

Mehler, P. S., Anderson, K., Bauschka, M., Cost, J. & Farooq, A. Emergency room presentations of people with anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 11 , 16 (2023).

Ferrer, M. et al. Cachexia: a systemic consequence of progressive, unresolved disease. Cell 186 , 1824–1845 (2023).

Bourke, C. D., Berkley, J. A. & Prendergast, A. J. Immune dysfunction as a cause and consequence of malnutrition. Trends Immunol. 37 , 386–398 (2016).

Tisdale, M. J. Biology of cachexia. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 89 , 1763–1773 (1997).

Babic, A. et al. Adipose tissue and skeletal muscle wasting precede clinical diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 14 , 4754 (2023).

Waning, D. L. et al. Excess TGF-β mediates muscle weakness associated with bone metastases in mice. Nat. Med. 21 , 1262 (2015). This study showed that bone metastases cause TGFβ to be released from the bone marrow, resulting in leakage of calcium from skeletal muscle cells contributing to muscle weakness.

Greco, S. H. et al. TGF-β blockade reduces mortality and metabolic changes in a validated murine model of pancreatic cancer cachexia. PLoS ONE 10 , e0132786 (2015).

Johnen, H. et al. Tumor-induced anorexia and weight loss are mediated by the TGF-beta superfamily cytokine MIC-1. Nat. Med. 13 , 1333–1340 (2007). This study showed that GDF15 was elevated in patients with cancer-associated weight loss and that this was a central regulator of appetite and therefore a potential therapeutic target.

Al-Sawaf, O. et al. Body composition and lung cancer-associated cachexia in TRACERx. Nat. Med. 29 , 846–858 (2023). This study showed an association among lower skeletal muscle area, subcutaneous adipose tissue and visceral adipose tissue and decreased survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and these were associated with higher levels of circulating GDF15.

Ahmed, D. S., Isnard, S., Lin, J., Routy, B. & Routy, J. P. GDF15/GFRAL pathway as a metabolic signature for cachexia in patients with cancer. J. Cancer 12 , 1125–1132 (2021).

Rebbapragada, A., Benchabane, H., Wrana, J. L., Celeste, A. J. & Attisano, L. Myostatin signals through a transforming growth factor β-like signaling pathway to block adipogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 , 7230 (2003).

Queiroz, A. L. et al. Blocking ActRIIB and restoring appetite reverses cachexia and improves survival in mice with lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 13 , 1–17 (2022).

Loumaye, A. et al. Role of activin A and myostatin in human cancer cachexia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100 , 2030–2038 (2015).

Barton, B. E. & Murphy, T. F. Cancer cachexia is mediated in part by the induction of IL-6-like cytokines from the spleen. Cytokine 16 , 251–257 (2001).

Webster, J. M., Kempen, L. J. A. P., Hardy, R. S. & Langen, R. C. J. Inflammation and skeletal muscle wasting during cachexia. Front. Physiol. 11 , 597675 (2020).

Strassmann, G., Masui, Y., Chizzonite, R. & Fong, M. Mechanisms of experimental cancer cachexia local involvement of 11-1 in colon-26 tumor. J. Immunol. 150 , 2341–2345 (1993).

Stovroff, M. C., Fraker, D. L., Swedenborg, J. A. & Norton, J. A. Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor: a possible mediator of cancer anorexia in the rat. Cancer Res. 48 , 4567–4572 (1988).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wyke, S. M. & Tisdale, M. J. NF-κB mediates proteolysis-inducing factor induced protein degradation and expression of the ubiquitin–proteasome system in skeletal muscle. Br. J. Cancer 92 , 711 (2005).

Cai, D. et al. IKKβ/NF-κB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 119 , 285–298 (2004). This study showed that activation of NF-κB, through muscle-specific transgenic expression of activated inhibitor of NF-κB kinase subunit β (IKKβ), causes profound muscle wasting in mice.

Patel, H. J. & Patel, B. M. TNF-α and cancer cachexia: molecular insights and clinical implications. Life Sci. 170 , 56–63 (2017).

Mergenthaler, P., Lindauer, U., Dienel, G. A. & Meisel, A. Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends Neurosci. 36 , 587 (2013).

Sillos, E. M. et al. Lactic acidosis: a metabolic complication of hematologic malignancies case report and review of the literature. Cancer 92 , 2237–46 (2000).

Rampello, E., Fricia, T. & Malaguarnera, M. The management of tumor lysis syndrome. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 3 , 438–447 (2006).

Delano, M. J. & Moldawer, L. L. The origins of cachexia in acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 21 , 68–81 (2006).

Lombardi, A., Villa, S., Castelli, V., Bandera, A. & Gori, A. T-cell exhaustion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria infection: pathophysiology and therapeutic perspectives. Microorganisms 9 , 2460 (2021).

Moldawer, L. L. & Sattler, F. R. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated wasting and mechanisms of cachexia associated with inflammation. Semin. Oncol. 25 , 73–81 (1998).

von Kobbe, C. Targeting senescent cells: approaches, opportunities, challenges. Aging 11 , 12844 (2019).

Shafqat, S., Chicas, E. A., Shafqat, A. & Hashmi, S. K. The Achilles’ heel of cancer survivors: fundamentals of accelerated cellular senescence. J. Clin. Invest. 132 , e158452 (2022).

Wang, L., Lankhorst, L. & Bernards, R. Exploiting senescence for the treatment of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 22 , 340–355 (2022).

Terry, W., Olson, L. G., Ravenscroft, P., Wilss, L. & Boulton-Lewis, G. Hospice patients’ views on research in palliative care. Intern. Med. J. 36 , 406–413 (2006).

White, C. & Hardy, J. What do palliative care patients and their relatives think about research in palliative care? A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 18 , 905–911 (2010).

Foster, B., Bagci, U., Mansoor, A., Xu, Z. & Mollura, D. J. A review on segmentation of positron emission tomography images. Comput. Biol. Med. 50 , 76–96 (2014).

Bera, K., Braman, N., Gupta, A., Velcheti, V. & Madabhushi, A. Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19 , 132–146 (2022).

Kaczanowska, S. et al. Immune determinants of CAR-T cell expansion in solid tumor patients receiving GD2 CAR-T cell therapy. Cancer Cell 42 , 35–51.e8 (2024).

Dutta, S. & Sengupta, P. Men and mice: relating their ages. Life Sci. 152 , 244–248 (2016).

Alpert, A. et al. A clinically meaningful metric of immune age derived from high-dimensional longitudinal monitoring. Nat. Med. 25 , 487–495 (2019).

Gyawali, B., Hey, S. P. & Kesselheim, A. S. Evaluating the evidence behind the surrogate measures included in the FDA’s table of surrogate endpoints as supporting approval of cancer drugs. eClinicalMedicine 21 , 100332 (2020).

Hong, W. et al. Automated measurement of mouse social behaviors using depth sensing, video tracking, and machine learning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , E5351–E5360 (2015).

Johnson, D. E., O’Keefe, R. A. & Grandis, J. R. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15 , 234–248 (2018).

Bowden, M. B. et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with suicide in gastric cancer in the United States. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 8 , 897–901 (2017).

Zaorsky, N. G. et al. Suicide among cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 10 , 1–7 (2019).

CAS Google Scholar

Hu, X. et al. Suicide risk among individuals diagnosed with cancer in the US, 2000 – 2016 . JAMA Netw. Open 6 , e2251863 (2023).

Google Scholar

Abdel-Rahman, O. Socioeconomic predictors of suicide risk among cancer patients in the United States: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 63 , 101601 (2019).

Pinquart, M. & Duberstein, P. R. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 40 , 1797–1810 (2010).

Fitzgerald, P. et al. The relationship between depression and physical symptom burden in advanced cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 5 , 381–388 (2015).

Chida, Y., Hamer, M., Wardle, J. & Steptoe, A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 5 , 466–475 (2008).

He, X. Y. et al. Chronic stress increases metastasis via neutrophil-mediated changes to the microenvironment. Cancer Cell 42 , 474–486.e12 (2024). This study found that chronic stress shifts the normal circadian rhythm of neutrophils resulting in increased neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation via glucocorticoid release, resulting in a metastasis-promoting microenvironment.

Fann, J. R., Ell, K. & Sharpe, M. Integrating psychosocial care into cancer services. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 , 1178–1186 (2012).

Jacobsen, P. B. & Wagner, L. I. A new quality standard: the integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 , 1154–1159 (2012).

Gorin, S. S. et al. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 , 539–547 (2012).

Li, M. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Psychooncology 26 , 573–587 (2017).

Bova, G. S. et al. Optimal molecular profiling of tissue and tissue components: defining the best processing and microdissection methods for biomedical applications. Mol. Biotechnol. 29 , 119–152 (2005).

Gundem, G. et al. The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature 520 , 353–357 (2015). This study found that metastasis-to-metastasis spread was common in prostate cancer evolution and that lesions affecting tumour suppressor genes occurred as single events, whereas mutations in genes involved in androgen receptor signalling commonly involved multiple, convergent events in different metastases.

Turajlic, S. et al. Tracking cancer evolution reveals constrained routes to metastases: TRACERx renal. Cell 173 , 581–594.e12 (2018). This study examined evolutionary trajectories of 100 renal cancers and found that metastasis competence was driven by chromosome complexity, not by driver mutation load, and that loss of 9p and 14q was a common driver.

Spain, L. et al. Late-stage metastatic melanoma emerges through a diversity of evolutionary pathways. Cancer Discov. 13 , 1364–1385 (2023). This study examined evolutionary trajectories of melanoma metastasis and observed frequent whole-genome doubling and widespread loss of heterozygosity, often involving antigen-presentation machinery.

Download references

Acknowledgements

A.B. is funded by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute P30 CA008748 and R01-CA245499. K.B. is employed by the UK National Health Service. T.R.C. acknowledges funding support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Ideas (2000937), Project (1129766, 1140125), Development (2013881) and Fellowship (1158590) schemes, a Cancer Institute NSW Career Development Fellowship (CDF171105), Cancer Council NSW project support (RG19-09, RG23-11) and Susan G. Komen for the Cure (CCR17483294). T.G. is funded by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Grant 00011633. M.J.-H. has received funding from CRUK, NIH National Cancer Institute, IASLC International Lung Cancer Foundation, Lung Cancer Research Foundation, Rosetrees Trust, UKI NETs and NIHR. T.J. acknowledges funding from Cancer Grand Challenges (NIH: 1OT2CA278690-01; CRUK: CGCATF-2021/100019), the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research (20-028-EDV), the Osprey Foundation, Fortune Footwear, Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory (CSHL) and developmental funds from CSHL Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA045508. R.K. is funded by the Intramural Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, NIH Clinical Center and the National Institutes of Health (NIH NCI ZIABC011332-06 and NIH NCI ZIABC011334-10). R.L. is supported by a Wellcome Early Career Investigator Award (225724/Z/22/Z). E.S. is supported by the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (CC2040), the UK Medical Research Council (CC2040) and the Wellcome Trust (CC2040) and the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant CAN_ORGANISE, Grant agreement number 101019366). E.S. reports personal grants from Mark Foundation and the European Research Council. C.S. is a Royal Society Napier Research Professor (RSRP\R\210001). His work is supported by the Francis Crick Institute that receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (CC2041), the UK Medical Research Council (CC2041) and the Wellcome Trust (CC2041) and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ERC Advanced Grant PROTEUS Grant agreement number 835297). M.G.V.H. reports support from the Lustgarten Foundation, the MIT Center for Precision Cancer Medicine, the Ludwig Center at MIT and NIH grants R35 CA242379 and P30 CA1405141.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Adrienne Boire, Katy Burke, Thomas R. Cox, Theresa Guise, Mariam Jamal-Hanjani, Tobias Janowitz, Rosandra Kaplan, Rebecca Lee, Charles Swanton, Matthew G. Vander Heiden, Erik Sahai.

Authors and Affiliations

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

Adrienne Boire

University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust Palliative Care Team, London, UK

Cancer Ecosystems Program, The Garvan Institute of Medical Research and The Kinghorn Cancer Centre, Darlinghurst, New South Wales, Australia

Thomas R. Cox

School of Clinical Medicine, St Vincent’s Healthcare Clinical Campus, UNSW Medicine and Health, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Department of Endocrine Neoplasia and Hormonal Disorders, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Theresa Guise

Cancer Metastasis Laboratory, University College London Cancer Institute, London, UK

Mariam Jamal-Hanjani

Department of Oncology, University College London Hospitals, London, UK

Mariam Jamal-Hanjani & Charles Swanton

Cancer Research UK Lung Centre of Excellence, University College London Cancer Institute, London, UK

Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbour, New York, NY, USA

Tobias Janowitz

Northwell Health Cancer Institute, New York, NY, USA

Paediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Rosandra Kaplan

Tumour Cell Biology Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute, London, UK

Rebecca Lee & Erik Sahai

Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Rebecca Lee

Cancer Evolution and Genome Instability Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute, London, UK

Charles Swanton

Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

Matthew G. Vander Heiden

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors researched data for the article. A.B., K.B., T.R.C., T.G., T.J., C.S., M.G.V.H, R.K., M.J.-H. and E.S. contributed substantially to discussion of the content. T.C., R.L. and E.S. wrote the article. All authors reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Thomas R. Cox or Erik Sahai .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

A.B. is an inventor on pending patents 63/449,817, 63/052,139 as well as awarded patents 11,305,014 and 10,413,522; all issued to the Sloan Kettering Institute. She has received personal fees from Apelis Pharmaceuticals and serves as an unpaid member of the Evren Technologies SAB. K.B., T.R.C., T.G., T.J. and R.K. declare no competing interests. M.J.-H. reports support from Achilles Therapeutics Scientific Advisory Board and Steering Committee, Pfizer, Astex Pharmaceuticals, Oslo Cancer Cluster and Bristol Myers Squibb outside the submitted work. R.L. reports personal fees from Pierre Fabre and has research funding from BMS, Astra Zeneca and Pierre Fabre outside the submitted work. E.S. reports grants from Novartis, Merck Sharp Dohme, AstraZeneca and personal fees from Phenomic outside the submitted work. C.S. reports grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche-Ventana, personal fees from Pfizer, grants from Ono Pharmaceutical, Personalis, grants, personal fees and other support from GRAIL, other support from AstraZeneca and GRAIL, personal fees and other support from Achilles Therapeutics, Bicycle Therapeutics, personal fees from Genentech, Medixci, China Innovation Centre of Roche (CiCoR) formerly Roche Innovation Centre, Metabomed, Relay Therapeutics, Saga Diagnostics, Sarah Canon Research Institute, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Illumina, MSD, Novartis, other support from Apogen Biotechnologies and Epic Bioscience outside the submitted work; in addition, C.S. has a patent for PCT/US2017/028013 licensed to Natera Inc., UCL Business, a patent for PCT/EP2016/059401 licensed to Cancer Research Technology, a patent for PCT/EP2016/071471 issued to Cancer Research Technology, a patent for PCT/GB2018/051912 pending, a patent for PCT/GB2018/052004 issued to Francis Crick Institute, University College London, Cancer Research Technology Ltd, a patent for PCT/GB2020/050221 issued to Francis Crick Institute, University College London, a patent for PCT/EP2022/077987 pending to Cancer Research Technology, a patent for PCT/GB2017/053289 licensed, a patent for PCT/EP2022/077987 pending to Francis Crick Institute, a patent for PCT/EP2023/059039 pending to Francis Crick Institute and a patent for PCT/GB2018/051892 pending to Francis Crick Institute. C.S. is Co-chief Investigator of the NHS Galleri trial funded by GRAIL. He is Chief Investigator for the AstraZeneca MeRmaiD I and II clinical trials and Chair of the Steering Committee. C.S. is cofounder of Achilles Therapeutics and holds stock options. M.G.V.H. is a scientific adviser for Agios Pharmaceuticals, iTeos Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, Faeth Therapeutics, Droia Ventures and Auron Therapeutics on topics unrelated to the presented work.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Cancer thanks Vickie Baracos, Clare M. Isacke, who co-reviewed with Amanda Fitzpatrick and Erica Sloan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

An autoimmune encephalitis characterized by complex neuropsychiatric features and the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptors in the central nervous system.

Partial collapse or incomplete inflation of the lung.

Pressure-induced movement of brain tissue.

An ageing-associated process in which haematopoiesis becomes dominated by one or a small number of genetically distinct stem or progenitor cells. Clonal haematopoiesis is linked to an increased risk of haematological malignancies.

Inability of the heart to pump blood properly.

Constriction of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.

(CRH). One of the major factors that drives the response of the body to stress.

(DIC). A rare but serious condition in which abnormal blood clotting occurs throughout the blood vessels of the body.

Inflammation of the brain.

An abnormal connection that forms between two body parts, such as an organ or blood vessel and another often unrelated structure in close proximity.

A rare disorder in which the immune system of a body attacks the nerves, which can lead to paralysis.

The stopping of flow of blood, typically associated with the bodies response to prevent and stop bleeding.

A build-up of fluid within the cavities of the brain.

Elevated calcium levels in the blood, often caused by overactive parathyroid glands. Hypercalcaemia is linked to kidney stones, weakened bones, altered digestion and potentially altered cardiac and brain function.

(HPD). Rapid tumour progression sometimes observed during immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

The condition that occurs when the level of sodium in the blood is low.

Harm, which is often unavoidable, caused by cancer treatments.

The marked suppression of polyclonal immunoglobulins in the body.

(LEMS). A neuromuscular junction disorder affecting communication between nerves and muscles, which manifests as a result of a paraneoplastic syndrome or a primary autoimmune disorder. Many cases are associated with small-cell lung cancer.

When cancer cells spread to the tissue layers covering the brain and spinal cord (the leptomeninges).

Also known as pulmonary oedema is a condition caused by excess fluid in the lungs. This fluid collects in the alveoli compromising function and making it difficult to breathe.

The observation of displacement of brain tissue across the centre line of the brain, suggestive of uneven intracranial pressure.

Decreased blood flow to the myocardium, commonly called a heart attack.

Inflammation specifically of the middle layer of the heart wall.

A group of rare disorders that occur when the immune system reacts to changes in the body triggered by the presence of a neoplasm.

A dense network of nerves that transmit information from the brain (efferent neurons) to the periphery and conversely transmit information from the periphery to the brain (afferent neurons). A component of the peripheral nervous system is the autonomic nervous system.

A build-up of fluid between the tissues that line the lungs and the chest wall.

A condition characterized by loss of skeletal muscle mass and function.

The lodging of a circulating blood clot within a vessel leading to obstruction. Thromboembolisms may occur in veins (venous thromboembolism) and arteries (arterial thromboembolism).

A key component of the pathway regulating blood clotting, specifically the receptor and cofactor for factor VII/VIIa.

A syndrome occurs when tumour cells release their contents into the bloodstream, either spontaneously or more typically, in response to therapeutic intervention.

Devices worn on the body, typically in the form of accessories or clothing, that incorporate advanced electronics and technology to monitor, track or enhance various aspects of human life. Examples include smartwatches and fitness trackers.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Boire, A., Burke, K., Cox, T.R. et al. Why do patients with cancer die?. Nat Rev Cancer (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-024-00708-4

Download citation

Accepted : 15 May 2024

Published : 19 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-024-00708-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The road less travelled.

Nature Reviews Cancer (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Cancer newsletter — what matters in cancer research, free to your inbox weekly.

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2024

End-of-life care needs in cancer patients: a qualitative study of patient and family experiences

- Mario López-Salas 1 ,

- Antonio Yanes-Roldán 1 ,

- Ana Fernández 1 ,

- Ainhoa Marín 1 ,

- Ana I. Martínez 1 ,

- Ana Monroy 1 ,

- José M. Navarro 1 ,

- Marta Pino 1 ,

- Raquel Gómez 1 ,

- Saray Rodríguez 1 ,

- Sergio Garrido 1 ,

- Sonia Cousillas 1 ,

- Tatiana Navas 1 ,

- Víctor Lapeña 1 &

- Belén Fernández 1

BMC Palliative Care volume 23 , Article number: 157 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

191 Accesses

Metrics details

Cancer is a disease that transcends what is purely medical, profoundly affecting the day-to-day life of both patients and family members. Previous research has shown that the consequences of cancer are greatly aggravated in patients at the end of life, at a time when they must also grapple with numerous unmet needs. The main objective of this study was to obtain more in-depth insight into these needs, primarily in patients with end-stage cancer nearing death.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in Spain with cancer patients at the end of life ( n = 3) and their family members ( n = 12). The findings from the interviews were analyzed using qualitative thematic analysis and a grounded theory approach.

Four major themes emerged from the interviews that explored the needs and concerns of patients with cancer at the end of life: (1) physical well-being (2) emotional well-being (3) social well-being and (4), needs relating to information and autonomous decision-making. The interviews also shed light on the specific needs of family members during this period, namely the difficulties of managing increased caregiver burden and maintaining a healthy work-life balance.

Conclusions

A lack of support, information and transparency during a period of immense vulnerability makes the end-of-life experience even more difficult for patients with cancer. Our findings highlight the importance of developing a more in-depth understanding of the needs of this population, so that informed efforts can be made to improve palliative healthcare and implement more comprehensive care and support at the end of life.

Peer Review reports

The concept of end of life reflects both the irreversible progression of a life-limiting disease, and a life expectancy of six months or less [ 1 ]. Cancer patients in the end-stage of the disease, facing end-of-life issues, undergo significant physical, psychological and social alterations, as do family members, whose lives and environment are drastically changed during this period. It is therefore of vital importance to improve the quality of life of all of those affected by this diagnosis. During this stage, numerous needs emerge regarding the care and well-being of the cancer patient and their caregivers which are not always acknowledged or identified. Recognition and awareness of these needs can ensure early access and comprehensive treatment for cancer patients with palliative care needs, while also meeting the needs of their caregivers [ 2 , 3 ].

In regard to patients, the literature provides some insight into the needs that emerge at this stage of the disease, yet there are still many areas that require further investigation. In a review by Wang et al. [ 4 ], which analyzed patients’ unmet needs in 38 studies, the authors identified seven major categories of needs. These included physical needs and symptom control, the need to maintain functionality and day-to-day activities, the need for information, psychological needs, social and financial needs, and spiritual needs. The relationship between various sociodemographic variables and patients’ unmet needs has also been studied. Several studies found that female patients had a higher frequency of unmet physical and psychological needs than male patients [ 5 , 6 ]. Similarly, patients with a high education level reported more unmet needs in physical domains, functionality, day-to-day activities [ 7 ] and information [ 8 ]. In addition, social needs appeared to a lesser extent in high-income patients [ 9 ]. Severe symptoms of emotional stress, the presence of anxiety and/or depression, a greater lack of problem-focused coping, and poorer quality of life of caregivers were identified as negative predictors of patient satisfaction [ 10 ]. Finally, when regarding primary caregivers, patients reported more unmet needs when their caregivers were male, young, or showed high levels of emotional distress [ 6 ].

For informal (or family) caregivers, the supportive care process is physically and psychologically challenging, especially when caring for patients with advanced cancer at the end of life [ 11 ]. However, assessing the unmet needs of caregivers remains an uncommon practice. Many family members, including those who do not view care giving as a burden, suffer from a wide range of problems, including sleep alterations, anxiety, depression, difficulty balancing caregiving and daily tasks, and financial burdens [ 12 ]. Wang and colleagues [ 4 ] found that caregivers had unmet needs regarding information about the disease and its treatment [ 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ], as well as psychological [ 17 , 18 ], economic [ 19 ] and spiritual needs [ 20 ]. Researchers also reported that younger caregivers had a higher number of unmet needs than older caregivers regarding care, information and economic needs [ 13 , 14 ]. Caregivers with physical problems experienced a greater number of unmet needs. Similarly, family caregivers reported more needs when patients suffered from anxiety, depression, or poor physical performance [ 14 ]. Family members also experienced a need for clear and reliable information that would help them prepare for their loved one’s death and the grieving process [ 21 , 22 ].

There is a genuine necessity for studies that integrate patient and caregiver needs, in part to illustrate and conceptualize a unique family unit, given that the different elements that comprise this unit interact and impact on one another. The literature clearly shows that the unmet needs of patients can increase the physical and emotional burden of the caregiver [ 23 ]. In turn, caregiver issues are closely related to patient well-being [ 24 ]. The unresolved issues or unmet needs of caregivers will not only diminish their own quality of life, but also negatively impact on patients’ health outcomes [ 25 ].

Finally, it should be noted that few studies focus on the changing needs of patients and family members at the end of life, or of bereaved caregivers coping with grief. Our research aims to help fill this gap in the literature, using qualitative methodology to identify the unmet needs and potential barriers [ 3 , 26 , 27 , 28 ] encountered by these patients and their families, and thus provide greater insight into what the end of life is, as opposed to what it could and should be, for all those involved.

An exploratory descriptive qualitative study was carried out using semi-structured interviews with patients with end-stage cancer at the end of life and their family members. Fieldwork was conducted in May and June 2023. The Charmaz grounded theory approach to thematic analysis was implemented [ 29 , 30 ]. Categories of analysis have been generated inductively and deductively, following a grounded theory approach, and then grouped into themes. This methodology allows researchers to delve into areas of knowledge and reality from a novel perspective, making it possible to explore common perceptions and experiences as part of the subjective social structure of the participants. The study was designed and developed following the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [ 31 ].

Participants

In this study, purposive sampling was used to identify participants, and obtain the maximum variation of the designed sample. This type of sampling is a strategy used to gather participants in a given context with expertise in the study phenomenon. Participants were recruited by health and social professionals through an association of cancer patients. The health professionals in direct contact with the participants informed them about the study and its objectives. Subsequently, and after signing the written informed consent sheet, the research team contacted the participants directly via e-mail or telephone call to confirm the interview. From an initial contact with 35 participants, the research team finally conducted 11 interviews with 15 participants. The variables chosen for the participants were: phase of the disease/after death (advanced, end of life, recent bereavement, bereavement after 6 + months), place of residence (rural, urban), age (< 65 or > 65) and gender. The sample also had ample experience with palliative care services, both at home and in hospital outpatient visits.

The final sample included 15 participants: 3 patients with end-stage cancer diagnosis and 12 caregivers who cared for terminally ill family members and experienced bereavement. A total of 10 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted, two of them in pairs (patient and relative), and another in a group composed of three caregivers. By including relatives of different ages, marital statuses and roles within the family, different narratives can be explored through the diverse perspectives, conflicts and connections collected.

Initially, 16 participants were proposed for the sample. However, theoretical saturation was reached at 15 participants, referring to the point in the research where new interviews added nothing novel or relevant to the study objectives [ 32 ], resulting in the final inclusion of 15 subjects. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of these participants.

Data collection

All interviews were conducted online through a videoconferencing platform, except for two that were conducted by telephone at the request of the interviewees. They were conducted by two professionals with experience in qualitative research on healthcare and palliative care who had no previous contact with the participants in order to avoid bias in data collection. The interviews were based on a broad directive script, designed by a team of oncology psychologists and social workers with extensive experience in palliative care. This script was adapted to the context and profile of each person that was interviewed. Family caregivers were asked about the needs of the patients and as well as their own needs. The main topics discussed were: (1) Perceptions about end-of-life and palliative care; (2) Difficulties in the end-of-life process and the needs detected, both met and unmet; (3) The demands and proposals at professional and institutional level for the resolution of these needs (see Supplementary Materials). Interviews lasted an average of 45 min.

The interviews were audio recorded with the consent of the participants, and later verbatim transcribed and anonymized in their entirety. Written informed consent sheet was provided to participants by the professionals who made the recruitment. In addition, the researcher who conducted the interviews asked for oral consent to the participants right before the interviews. They were also provided the opportunity to ask questions and dispel doubts before starting the interview process. No payment was offered in exchange for participation in the study. Personal data and digital rights of participants were protected in accordance with the LOPDGDD 03/2018 [ 33 ].

Data analysis

To get an overview of the information before starting with the initial coding, 5 researchers of the team read the entire transcriptions repeatedly. The transcripts were then segmented into text units relevant to the analysis, which were subsequently read by all researchers. Finally, segments from the interviews were coded based on degree of relevance. A code tree was produced, combining closed categories previously discussed by the research group with categories that emerged inductively from the collected data. This tree was tested in the coding of certain interviews and adapted throughout the field research process to improve its scope and effectiveness. Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. The information from the codes generated was compared with each other in order to create new categories. The codes were analyzed using both an inductive and a deductive approach that identifies similar, interrelated patterns and allows the theoretic categories described in the study to emerge from the raw data itself. Analytical rigor was assured through a rigorous process of peer review, since other researchers from the team were invited to review the initial analysis, in order to confirm the consistency of the findings and to identify and diminish potential biases. All the researchers agreed with the results of the coding process and the generation of the main categories. Data analysis was performed using ATLAS.ti version 9.

The results were divided into two main sections: the needs of people diagnosed with cancer at the end of life and the needs of family caregivers during this final phase of care.

End-of-life needs for cancer patients

The main results are shown in Table 2 . The needs of these patients are modified in accordance with disease progression and proximity to death.

Physical well-being

One of the main themes that emerged from participant responses was the need to maintain a sense of physical well-being. This set of needs is aimed at improving their quality of life by monitoring the symptoms of both the disease and its treatment. The main codes indicated by participants were the need to control pain and the adverse effects of medication, to find cures and clinical procedures to ensure quality of life, and to organize the administration of medication.

“That I, her daughter, have to act as a nurse, as I watch my mother dying and being told on the phone: ‘inject this, inject that’.” P12 .

The other codes regarding physical well-being were functional problems related to care. These needs include optimal rest and sleep, adapting diet and eating habits to allay weight gain or lack of appetite, and maintaining personal hygiene and physical activity.

“Well, you have to be aware of the circumstances. In terms of strength, it depends on the day…I’ve lost a lot of weight and I don’t sleep well, but I used to sleep very well. And this, of course, limits you.” P1 .

“I have my doubts about what the best diet is. The oncologist doesn’t know. I found a nutritionist, and it’s a little clearer now, but I think I lack information. Nothing is said about the diet…” P1 .

Emotional well-being

Another theme that concerned participants was their emotional well-being. Participants put a high priority on addressing emotional needs related to illness, dependency and death, as well as having access to assistance in effectively expressing and communicating these needs.

“Nobody talks about the psychological burden that this disease can place on the patient. How your life changes, all that it entails. The pain, going to the hospital continuously, and not knowing what will happen in the near future. More help is needed so we can understand how to relate to the disease rather than confront it.” P1 .