Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Parents' Ultimate Guide to AI Companions and Relationships

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Jewish Experiences

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Multicultural Books

YouTube Channels with Diverse Representations

Podcasts with Diverse Characters and Stories

Parents' guide to, little women.

- Common Sense Says

- Parents Say 11 Reviews

- Kids Say 61 Reviews

Common Sense Media Review

By Stephanie Dunnewind , based on child development research. How do we rate?

Classic still charms despite outdated gender roles.

Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that Louisa May Alcott's semi-autobiographical Little Women , originally published in 1868, is a lengthy, beloved American classic that tells the story of the four March sisters growing up in Boston during and after the Civil War, as they wait for their father to return home. Generations…

Why Age 10+?

Meg drinks champagne at a party and acts unlike herself. Laurie gives Jo a glass

A pet dies. Mr. Laurence shakes Laurie for not answering him. References to the

A man at a party is described as a "large-nosed Jew."

Any Positive Content?

The books offers mostly positive messages. The girls struggle with their desires

The girls are loyal sisters and friends. Each works on her faults, especially Jo

The book offers a realistic look at life in the Civil War and post-Civil War tim

Drinking, Drugs & Smoking

Meg drinks champagne at a party and acts unlike herself. Laurie gives Jo a glass of wine to help calm her. The family does not serve wine at Meg's wedding because Mr. March "thinks wine should be used only in illness." Meg makes Laurie promise not to drink.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Drinking, Drugs & Smoking in your kid's entertainment guide.

Violence & Scariness

A pet dies. Mr. Laurence shakes Laurie for not answering him. References to the realities of the Civil War.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Violence & Scariness in your kid's entertainment guide.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Language in your kid's entertainment guide.

Positive Messages

The books offers mostly positive messages. The girls struggle with their desires for material things despite their poverty but come to appreciate what they have. The family helps a less-fortunate family by visiting and sending food, including giving up their Christmas breakfast. Religion plays an important role in the family, with the girls trying to overcome their faults. The family spends time together, including singing at the piano in the evening. During a week where the girls decide not to work, Beth forgets to take care of her pet bird, which dies (and everyone learns a lesson about sloth). There are many outdated (and yet true to the time period) examples of gender roles and attitudes, including that women should be docile, skilled in housekeeping ("the womanly skill that keeps home happy"), and submissive to men.

Positive Role Models

The girls are loyal sisters and friends. Each works on her faults, especially Jo. Jo forgives her younger sister for burning one of her stories. And she cuts off her hair ("her one beauty") to help her father. Jo and Amy encourage Laurie to live up to his potential. The older girls work rather than attend school. Jo defies convention and gets chided for liking sports and being active by rowing and running. Laurie pulls a prank on Meg but apologizes. Amy is generous with a selfish girl and is rewarded for her principle.

Educational Value

The book offers a realistic look at life in the Civil War and post-Civil War time period.

Parents need to know that Louisa May Alcott's semi-autobiographical Little Women , originally published in 1868, is a lengthy, beloved American classic that tells the story of the four March sisters growing up in Boston during and after the Civil War, as they wait for their father to return home. Generations of readers have loved its vivid, relatable characters. However, the writing style is old fashioned and the story features outdated (but time-period-appropriate) gender roles. Religion plays an important role in the family, so there are many religious references.

Where to Read

Parent and kid reviews.

- Parents say (11)

- Kids say (61)

Based on 11 parent reviews

An amazing book

Good classic book from the 1860s, what's the story.

LITTLE WOMEN is set in Boston during and just after the Civil War and follows the four March sisters as they struggle to overcome poverty and grow into proper young ladies. Meg, the oldest, is pretty but swayed by material temptations. Jo is a good-hearted tomboy and writer. Beth is a shy, sweet music lover. And Amy, the youngest, is a little selfish but very social and elegant. Even as the girls bicker like all siblings, they keep their loving home together as they wait for their father to return from the war.

Is It Any Good?

The enduring appeal of this novel is its vivid depiction of its 19th-century time period. The Little House books apealr to generation after generation for the same reason. Though the writing style in Little Women can be didactic, even contemporary girls who can't imagine wearing silk dresses or being too ladylike to run will identify with the March sisters' strong bonds and earnest efforts to overcome their faults. Today's reader will especially appreciate Jo, who romps with her best friend (a boy) and cuts her hair short and defies the era's gender conventions.

At nearly 800 pages (for some editions), the book might work better as a read-aloud so parents can skip the occasionally lengthy, boring passages of description, long letters, or the girls' plays. Young readers may struggle with the sometimes archaic language and unfamiliar references.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about the emphasis on "housewifely" duties for women shown in Little Women . How are opportunities and expectations different for women today? How are they similar?

What do you think of how the author breaks in with first-person comments. How does it compare with contemporary novels?

Would you have liked living during the 1860s? Why or why not?

Book Details

- Author : Louisa May Alcott

- Genre : Family Life

- Book type : Fiction

- Publisher : Puffin

- Publication date : September 30, 1868

- Number of pages : 798

- Last updated : January 15, 2019

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

Suggest an Update

What to read next.

The Penderwicks: A Summer Tale of Four Sisters, Two Rabbits, and a Very Interesting Boy

Outside Beauty

The Year My Sister Got Lucky

Books with Strong Female Characters

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

We Need to Talk About Books

Little women by louisa may alcott [a review].

Little Women is a story readers have enjoyed for generations and has influenced a number of aspiring and successful writers. It is a story of growing up, moral betterment, career and marital aspirations and fortitude in the face of disappointment and tragedy. A bit sentimental and juvenile, it may not be for everyone, but that should not deter you from experiencing this classic.

Little Women is a coming-of-age tale centred on the four March sisters – Meg, Jo, Amy and Beth. When the story begins, their father is serving voluntarily in the American Civil War as a chaplain. The girls lament the family’s lack of money – what funds they had were lost after their father came to the aid of an unfortunate friend – which prevents them from having the Christmas celebration of their wishes, with abundant presents and an absence of labour.

I shall have to toil and moil all my days, with only little bits of fun now and then, and get old and ugly and sour, because I’m poor, and can’t enjoy my life as other girls do. It’s a shame!

Though they resolve to make the best of their situation and surprise their mother with a present, even this good spirit is spoiled by a letter from their father. Hearing of hardship that exceeds their own, the girls renounce their complaints over gifts and work. Their mother reminds them of their joint love of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and suggests it as an allegory for their own betterment.

Our burdens are here, our road is before us, and the longing for goodness and happiness is the guide that leads us through many troubles and mistakes to peace which is the true Celestial City.

Though still young, and having a great deal in common, the sisters’ individual personalities are already very evident. Meg, the eldest at sixteen years old, dreams of a future of wealth and luxury and occupies herself as a nursery governess. Jo, a bookworm and aspiring writer is something of a tomboy and, much to her displeasure, spends her time as a companion to an elderly aunt. Beth, at thirteen years old is somewhat quiet and timid. A peacemaker in the family with a love of music, her shyness means she is home-schooled. While Amy, the youngest, is very ladylike, a ‘snow maiden’ with careful manners and an interest in drawing and art.

Next door to the March’s lives Mr Laurence, a very private and wealthy elder gentleman who, despite his gruff exterior, is very kind, hiding a sad past. Living with Mr Laurence is his grandson, who goes by ‘Laurie’ and spends most of his time hard at study, locked away with his tutor with high expectations of excelling in college and entering the family’s international trade business. Somewhat lonely, Laurie blossoms with increased acquaintance with the March girls who find him to be a perfect gentleman. Even Beth is enticed out of her shell by the Laurences and visits regularly to play piano for Mr Laurence.

As the girls grow up, episodes from their lives teach them lessons about modesty and gratitude, repentance and forgiveness, pride and a work-life balance. While able to enjoy some of the pursuits of other young adults of the time, there is also the repeated threat of poverty, illness, damaged reputations and the constant onus of hard work. But there are also new opportunities, for love, marriage, career and travel.

I want my daughters to be beautiful, accomplished, and good; to be admired, loved, and respected, to have a happy youth, to be well and wisely married, and to lead useful pleasant lives, with as little care and sorrow to them as God sees fit to send. To be loved and chosen by a good man is the best and sweetest thing which can happen to a woman; and I sincerely hope my girls may know this beautiful experience.

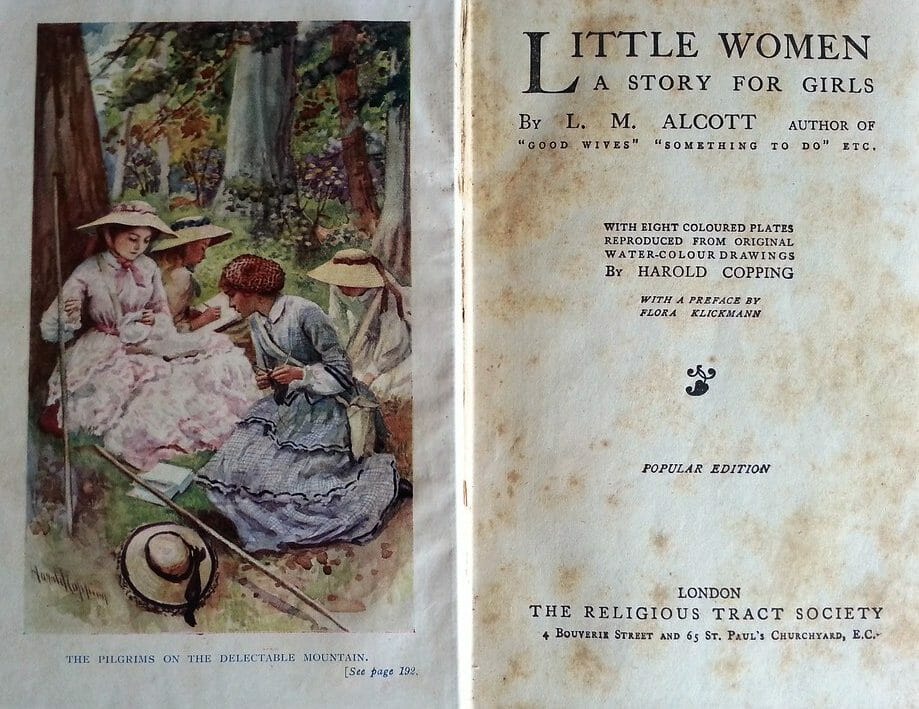

Little Women was originally published in two separate parts in 1868 and 1869. It was reworked in 1880 and made even more sentimental than in already was and it is this 1880 version that most readers are familiar with. The version that I read is a recreation of the original 1868-9 edition with the only changes being corrections for spelling and grammar.

I like to think of myself as an openminded reader. With a few exceptions, I don’t want to consciously restrict my reading in any way and I’m happy to not only read books that catch my interest but that have achieved great appeal to others. I detest the idea that there are certain books for certain people. Literature’s greatest power is to allow the reader to experience vicariously what we otherwise would not. Even if some people will understand or be affected by some books more than others, the generation of empathy is literature’s great strength regardless.

All that being said, Little Women may not be a book for me! I don’t really have a great deal to objectively critique the book for – it is clearly very well written and has influenced and been enjoyed by a great number of people. And there were parts of it that I appreciated and enjoyed as well. My overall feelings for the book are mostly subjective and related to its style and tone – it was just too sentimental, too juvenile, for me. Too much fretting over dresses and hair, too difficult to hop on board with the enthusiasm for children’s pursuits and events.

After I finished the book, I realised that I actually have a copy of the 1994 film adaptation which I have not seen; the one with Winona Ryder and Susan Sarandon among other notables. Normally I always watch an adaptation after finishing a novel and incorporate it into my review, but this time I just could not face it. There have been multiple adaptations of Little Women and another star-studded one will be released at the end of this year, with Meryl Streep and Saoirse Ronan.

As well as its sentimentality, the book is also quite preachy. It is a story about God, country and father-figures; pride, humility and piety; hard work and simple pleasures. John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress , as well as Alcott’s own family hardship and her relationships with her sisters, provided the model for Little Women , with female progress replacing male. I would not necessarily say that I found the preachiness off-putting, even though I don’t always agree with it, but it does accumulate and when transparent it takes away the illusion of realism in the story.

I gave my best to the country I love, and kept my tears till [your father] was gone. Why should I complain, when we both have merely done our duty, and will surely be the happier for it in the end? If I don’t seem to need help, it is because I have a better friend, even than father, to comfort and sustain me. My child, the troubles and temptations of your life are beginning, and may be many; but you can overcome and outlive them all, if you learn to feel the strength and tenderness of your Heavenly Father as you do that of your earthly one. The more you love and trust Him, the nearer you will feel to Him, and the less you will depend on human power and wisdom. His love and care never tire or age, can never be taken from you, but may become a source of lifelong peace, happiness and strength. Believe this heartily, and go to God with all your little cares, and hopes, and sins, and sorrows, as freely and confidently as you come to your mother.

As I said, it is very well-written, so despite by own tastes I found myself getting interested and invested. Probably even more that I realised. When the story took a twist or turn, I surprised myself by how much I was committed.

With regards to technique I have very little to say. Alcott is clearly an excellent writer who manipulates her reader’s thoughts and emotions well. There were times when I thought events were a little too transparent, where it seemed too obvious what the writer has in store. But there was also a chapter, late in the book – whose details I won’t spoil here – that I found to be a standout. There, the characters and the reader move from innocence to hesitancy to confession, to conflict and self-doubt within a very believable interaction. It was a wonderful exploitation and manipulation of the characters and the reader.

The one technical fault I felt the book had was that it was too long. Little Women limps towards the end. I felt there was little story left in the last fifth or so to power my enthusiasm and I had to force myself a little to read on and wished the ending, which seemed pretty clear to see, would hurry on. In the end it becomes a bit of a match-making novel but not one as rich or as compelling as an Austen.

After finishing Little Women , I found support in these thoughts from what I thought would be an unlikely source – the author! Alcott had to be cajoled somewhat into writing the second part to Little Women , by publishers who wanted to build on the success of the first part and by readers eager to see the March sisters married off. Alcott complied but mischievously worked to deny readers the satisfaction of the matches they would have hoped for the sisters. But to make such endings plausible, given what had come before, takes time and stretched out the novel.

“I don’t like sequels, and I don’t think No 2 will be as popular as No 1,” [Alcott] wrote her uncle, “but publishers are very [perverse] & won’t let authors have [their] way so my little women must grow up and be married off in a very stupid style.” She was annoyed when girls wrote to her to ask “who the little women marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life.” At first Alcott resisted the pressures of the standard marriage plot […] but she quickly saw the fictional possibilities in creating a different kind of marriage for [the characters]. – From the Introduction.

While, in Part One of Little Women the focus is shared pretty evenly between the four girls, in Part Two, which begins three years after Part One ends, Jo feels like the star and centre of the story. I don’t think I am alone in finding her – headstrong, intelligent and bookish – my favourite character.

As an aspiring writer, it is not a big leap to speculate as to the autobiographical relationship between Jo and Alcott. There is much of Part Two of Little Women that is about Jo’s pursuit of a writing career – about the difficulties of getting published, the challenges of earning a living as a writer, the conflict of writing what you want versus what publishers and readers want, not to mention the problem of what women writers of the time ‘ought not’ to write about.

Alcott’s own life experiences would have informed the conflicts Jo faces in the novel. Before writing Little Women she had secretly published several lurid thrillers under a pseudonym. She also wrote unpublishable novels of interracial love. The success of Little Women gave her family the financial security they lacked but also confined the style and subject matter of her writing for the rest of her life.

[Alcott’s unpublished novel The Long Love Chase (1867) and her later novel A Modern Mephistopheles (1877) both] suggest her guilty sense of having bartered her womanhood and art in the name of financial expedience, to achieve literary and commercial success. […] “Though I do not enjoy writing ‘moral tales’ for the young,” she wrote to an admiring correspondent, “I do it because it pays well.” – From the Introduction.

The edition I read included an introduction by Elaine Showalter who, at the time of publishing, was an English professor at Princeton. Her introductory essay has some interesting information about Alcott, her influences and inspiration for Little Women , some of which I have included above. In addition, she discusses the fact that, despite the book’s popularity and influence, and the author’s body of other work, it took a long time for Little Women to be accepted as serious literature and a classic. She also shares the relationship feminist critics have had with Little Women , championing some aspects, but being disappointed by others, and the change of this relationship over time.

For some feminist critics, Alcott’s lifelong effort to tailor her turbulent imagination to suit the moralism of her father, the commercialism of her publishers, and the puritanism of “gray Concord,” kept her from fulfilling her literary promise. For others Little Women stands as one of the best studies we have of the literary daughter’s dilemma: the tension between female obligation and artistic freedom. – From the Introduction

To me, it is the sustained enjoyment and influence of Little Women over a long period of time that assures its classic status. It is because of such credentials that I was always going to read Little Women according to my approach to reading. Though it was not for me, for purely subjective reasons of style and subject, I still found things to appreciate and I would not discourage others from giving this classic a try.

Share this:

10 comments.

Excellent review! Personally I am of the opinion that I would have enjoyed Little Women far more if Alcott had simply left the book at the first part. I would have enjoyed savoring my own speculation as to the future of the characters and the second portion is indeed a bit winded. It is wonderful to see you being so open-minded despite the fact that this was not an instant hit for you.

Like Liked by 2 people

Thanks! Even though the second part was ‘a bit winded’ as you say, I bet, if she had never written more, she never would have heard the end of fans wanting to read more of the March sisters and there would probably be people still wishing for more today!

Like Liked by 1 person

And then we would have gotten a horrible sequel “discovered” or written by some modern day author.

I often read just Little Women Part 1 on its own 🙂

Agreed. It’s much more satisfying at the end.

I loved Little Women when I was younger, but haven’t re-read it for years. The sentimentality and preachiness didn’t bother me then, but I think it might now! I’m glad you still found things to appreciate, even though the book wasn’t for you.

Thanks! Although I didn’t mention it, I’m certain age would be a factor in how a reader would view Little Women. Adults would take something very different from the book than children or young adults, much like for Narnia.

Its really great how you use those words! ITS JUST MAGIC! Marvelous review!

I loved this review ever so much! Thank you for your candid opinion. I equally loved the book but found it rather imperfect. I was also subject to the unexpected matchmaking twist 😫 I agree with you on how the story turned out to be a game of matchmaking for the March girls. Indeed, Austen would have done a better work at that.

Hi Mara. Thanks for your kind comment. The book probably sits in an awkward spot for modern readers. We may not view match-making and marriage as the completely fulfilling happy ending for the characters as readers of the time did – judging by their letters to the author. But if a story was going that way, we’d like to see it done well! Sorry for the late reply.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- The Hypercritic Project

- Hypercritic for Companies

- Media coverage of Hypercritic’s work

- Meet the Hypercritics

- Collections

- Write To Us

Don’t miss a thing

Supported by

Copyright 2022 © All rights Reserved. Iscrizione registro stampa n. cronol. 4548/2020 del 11/03/2020 RG n. 6985/2020 al Tribunale di Torino. Use of Hypercritic constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use , Privacy Policy , Cookie Policy

- Little Women | An independence story against society’s expectations

Little Women | An independence story against society's expectations

Big - Little

Fast - Slow

Easy - Hard

Clean - Dirty

Original language

It is not unusual for a classic piece of literature to be rediscovered and some stories never get old and are always accurate and modern, as more than one hundred years of adaptations show. Stories like Little Women .

Louisa May Alcott and her sisters

Written by American novelist Louisa May Alcott and published in two volumes dated 1868 and 1869, Little Women is a coming-of-age novel; “a book about girls” was the publisher’s request. Alcott never liked the idea, because she “ never liked girls, or knew many, except [her] sisters “. And that’s what she wrote about.

It follows the lives of four sisters named Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy in their personal journey from childhood to womanhood. Alcott thought of this journey in a similar way as Emily Dickinson , with it being a suffering path of growth.

Little Women conveys four different unique points of view on the March family during the tough times of the American Civil War. With their father serving in the war, the four sisters have to help their family, now in poverty. “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents” is the opening line of the book and it pictures March family’s status, and how the four sisters perceived it.

A two-part success

The first part of the book was a critical and commercial success, and the second part followed the trend. It was a new genre, a sentimental story based mostly on characters readers could sympathize with. And with readers wanting to know more about the March sisters, other books complete the saga: Little Men (1871) and Jo’s Boys (1886).

In 1880 Little Women was published as a single novel and it has been translated into numerous languages ever since, becoming an international phenomenon. Readaptations started with different editions of the book, mostly to make it into a children’s novel, and went on with movies and TV shows.

Timeless strong female character

Jo is the main character of the story. She is a young woman struggling to make her temper fit in and adapt to the role she is supposed to fill in society; a role that is not made for such a boyish girl as she. Humor and creativity are her weapons as she fights her own family to control her stubborn personality. She wants to become a writer; that is why Jo is known to be a representation of Alcott herself. Jo wants her independence; she wants to control it, and she owns it even after falling in love with Professor Bhaer, whom she marries despite always refusing the idea of being a wife. As the strong, independent woman she is, Jo is one of the reasons why Little Women is so up-to-date. A person, someone girls can look up to.

More than a century of adaptations

Alexander Butler’s Little Women (1917), the first adaptation of Alcott’s book, was a movie, now lost. Since then almost every decade has its own movie adaptation, whether it is for cinema or television. The 1949 and the 1994 versions are the most famous.

But a more modern twist was taken in 2014. Produced by Cherrydale Productions and distributed by Pemberley Digital, The March Family Letters is a web series available on YouTube based on the famous novel. A new medium that created a real community with characters even having personal social media accounts.

In 2019 Greta Gerwig wrote and directed the 7th film adaptation of Little Women . The movie was successful, thanks to the cast ( Saoirse Ronan , Emma Watson , Florence Pugh , Eliza Scanlen , Laura Dern , Timothée Chalamet , Meryl Streep ) as well as the fresh and powerful storytelling of such a classic. The key that leads characters is finding their own identity. Every March sister seems to understand Jo’s ambition as they too go down the same road. They need to be just who they are, despite society and morality around them.

Lovingly Related Records

Marzella | The passage from childhood to puberty

Posted on 07 June, 2021

One Hundred Years of Solitude | History in a family saga

Posted on 12 January, 2021

The House of the Spirits | From a letter to Magical feminism

Posted on 27 April, 2021

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

Book Review: “Little Women” By Louisa May Alcott

After seeing Greta Gerwig’s film adaptation of “Little Women” at the start of the year, I was totally captivated by the heart-warming story.

I made a resolution to read the book, partly to further indulge in its uplifting message, and partly to see how closely the film resembled the novel.

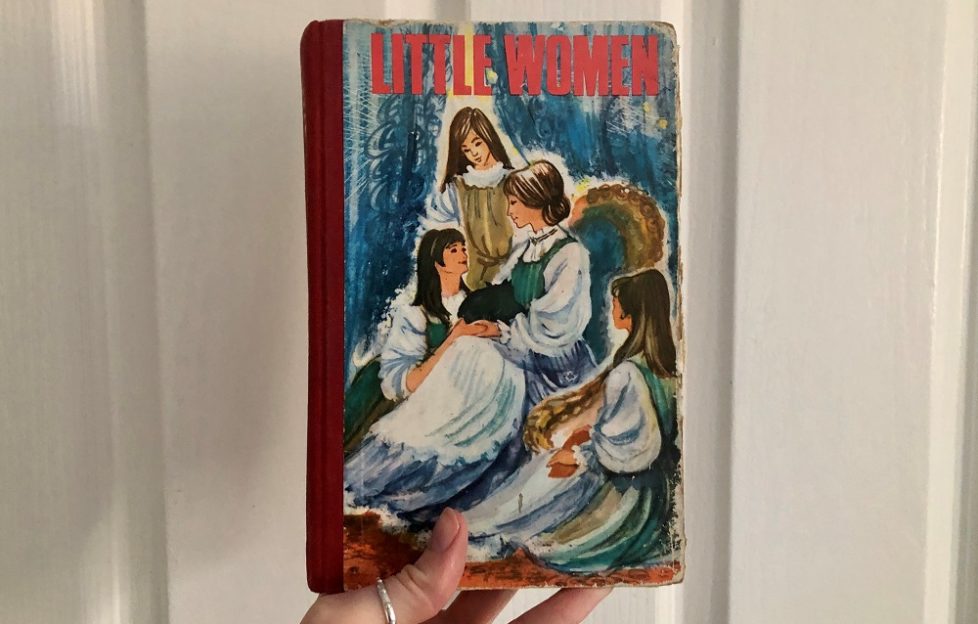

By chance, I found an old copy of “Little Women” which had been my Mum’s when she was young. Unfortunately, her brothers had used it as a colouring in book . . .

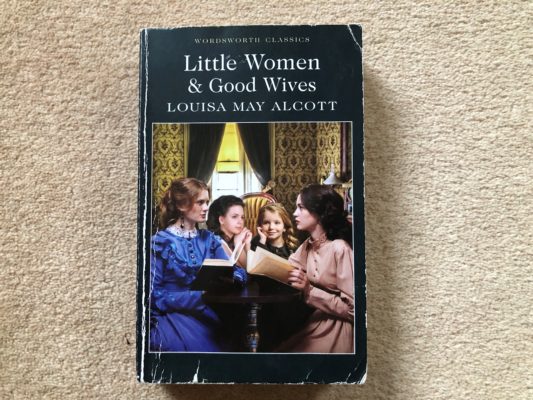

Photograph by Mairi Hughes.

While the book was just about readable, being pre-occupied with other books meant I didn’t manage to make a start on it.

When we went into lockdown, a friend kindly sent me a brand new copy of “Little Women” (graffiti free). As I had a lot of extra time on my hands, I finally got down to reading it.

Uplifting reading

The book I have contains the original “Little Women” story and the sequel, “Good Wives”, both of which are included in Greta Gerwig’s film.

This was the longest novel I’d taken on in a while, with writing so good every word needs savoured, so admittedly it took me a while to get through it!

The story follows the March sisters, Jo, Amy, Meg and Beth, through their childhood and into adulthood. The book is loosely based on Alcott’s own childhood, and has been deemed semi-autobiographical by many scholars.

I enjoyed every page. This is the perfect bedtime read as Alcott’s writing paints an incredibly vivid picture, providing a healthy dose of escapism. The long and captivating chapters meant I often found myself reading for far longer than I had intended.

One of my favourite things about this book was how wholesome it was. The bond depicted between the March sisters will have anyone reminiscing about the purity of childhood friendships. However it wasn’t always smooth sailing, and — without giving too much away — there were definitely some tear-jerking moments.

Alcott perfectly depicts the innocence of childhood, and all the ups and downs of the journey into adulthood. I can guarantee anyone who reads the book will quickly grow attached to the March sisters.

For anyone who enjoyed Greta Gerwig’s “Little Women” film, I would whole-heartedly recommend reading the book.

It allows a deeper insight into the complexities of the characters above and beyond what is portrayed in the film, and ties up a few of the film’s loose ends.

For more book reviews from “The People’s Friend”, click here .

Mairi Hughes

Related Posts

5 Top Reads This Autumn!

As the nights grow darker, light up your evenings with a great read. Here's our top 5 books for autumn 2024!

Richard Osman Releases His New Book ‘We Solve Murders’

Following the instant success of his debut novel 'The Thursday Murder Club', best-selling author Richard Osman has just published a new book.

World Roald Dahl Day

Fiction Ed Lucy pays tribute to the whizzpopping talent of a literary giant on Roald Dahl Day.

Your weekly dose of joy!

Subscribe to The People’s Friend and enjoy a weekly dose of heart-warming fiction stories, practical lifestyle and gardening tips, and inspiring craft projects.

RELATED READS

7 great gift ideas from “the friend”, cheeky chocolate bats, crochet a poppy brooch.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How “Little Women” Got Big

It is doubtful whether any novel has been more important to America’s female writers than Louisa May Alcott’s “ Little Women ,” the story of the four March sisters living in genteel poverty in Massachusetts in the eighteen-sixties. The eldest is Meg, beautiful, maternal, and mild. She is sixteen when the book opens. Then comes Meg’s opposite, fifteen-year-old Jo: bookish and boyish, loud and wild. Jo writes plays that the girls perform, with false mustaches and paper swords, in the parlor. Next comes Beth, thirteen: recessive, unswervingly kind, and doomed to die young. She collects cast-off dolls—dolls with no arms, dolls with their stuffing coming out—and nurses them in her doll hospital. Finally, there is Amy, who is vain and selfish but, at twelve, also the baby of the family, and cute, so everybody loves her anyway. The girls’ father is away from home, serving as a chaplain in the Civil War. Their mother, whom they call Marmee, is with them, and the girls are always nuzzling up to her chair in order to draw on her bottomless fund of loving counsel. Next door live a rich old man and his orphaned grandson, Laurie, who, when he is home from his Swiss boarding school, lurks behind the curtains to get a look at what the March sisters are up to. Jo catches him spying on them, and befriends him. He soon falls in love with her.

These characters are not glamorous, and the events are mostly not of great moment. We witness one death, and it is a solemn matter, but otherwise the book is pretty much a business of how the cat had kittens and somebody went skating and fell through the ice. Yet “Little Women,” published in 1868-69, was a smash hit. Its first part, in an initial printing of two thousand copies, sold out in two weeks. Then, while the publisher rushed to produce more copies of that, he gave Alcott the go-ahead to write a second, concluding part. It, too, was promptly grabbed up. Since then, “Little Women” has never been out of print. Unsurprisingly, it has been most popular with women. “I read ‘Little Women’ a thousand times,” Cynthia Ozick has written. Many others have recorded how much the book meant to them: Nora and Delia Ephron, Barbara Kingsolver, Jane Smiley, Anne Tyler, Mary Gordon, Jhumpa Lahiri, Stephenie Meyer. As this list shows, the influence travels from the highbrow to the middlebrow to the lowbrow. And it extends far beyond our shores. Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, and A. S. Byatt have all paid tribute.

The book’s fans didn’t merely like it; it gave them a life, they said. Simone de Beauvoir, as a child, used to make up “Little Women” games that she played with her sister. Beauvoir always took the role of Jo. “I was able to tell myself that I too was like her,” she recalled. “I too would be superior and find my place.” Susan Sontag, in an interview, said she would never have become a writer without the example of Jo March. Ursula Le Guin said that Alcott’s Jo, “as close as a sister and as common as grass,” made writing seem like something even a girl could do. Writers also used “Little Women” to turn their characters into writers. In Elena Ferrante’s “My Brilliant Friend,” the two child heroines have a shared copy of “Little Women” that finally crumbles from overuse. One becomes a famous writer, inspired, in part, by the other’s childhood writing.

Long before she wrote “Little Women,” Alcott (1832-88) swore never to marry, a decision that was no doubt rooted in her observations of her parents’ union. Her father, Bronson Alcott (1795-1888), was an intellectual, or, in any case, a man who had thoughts, a member of New England’s Transcendental Club and a friend of its other members—Emerson, Thoreau. Bronson saw himself as a philosopher, but he is remembered primarily as a pioneer of “progressive education.” He believed in self-expression and fresh air rather than times tables. But the schools and communities that he established quickly failed. His most famous project was Fruitlands, a utopian community that he founded with a friend in the town of Harvard, Massachusetts, in 1843. This was to be a new Eden, one that eschewed the sins that got humankind kicked out of the old one. The communards would till the soil without exploiting animal labor. Needless to say, they ate no animals, but they were vegetarians of a special kind: they ate only vegetables that grew upward, never those, like potatoes, which grew downward. They had no contact with alcohol, or even with milk. (It belonged to the cows.) They took only cold baths, never warm.

Understandably, people did not line up to join Fruitlands. The community folded after seven months. And that stands as a symbol for most of Bronson Alcott’s projects. His ideas were interesting as ideas, but, in action, they came to little. Nor did he have any luck translating them into writing. Even his loyal friend Emerson said that when Bronson tried to put his ideas into words he became helpless. And so Bronson, when he was still in his forties, basically gave up trying to make a living. “I have as yet no clear call to any work beyond myself,” as he put it. Now and then, he staged a Socratic “conversation,” or question-and-answer session, with an audience, and occasionally he was paid for this, but for the most part his household, consisting of his energetic wife, Abba, and his four daughters, the models for the March girls, had to fend for themselves. Sometimes—did he notice?—they were grievously poor, resorting to bread and water for dinner and accepting charity from relatives and friends. (Emerson was a steady donor.) By the time Louisa, the second-oldest girl, was in her mid-twenties, the family had moved more than thirty times. Eventually, Louisa decided that she might be able to help by writing stories for the popular press, and she soon discovered that the stories that sold most easily were thrillers. Only in 1950, when an enterprising scholar, Madeleine B. Stern, published the first comprehensive biography of Alcott, did the world discover that the author of “Little Women,” with its kittens and muffins, had once made a living producing “ Pauline’s Passion and Punishment ,” “ The Abbot’s Ghost or Maurice Treherne’s Temptation ,” and similar material, under a pen name, for various weeklies.

Soon, however, a publisher, Thomas Niles, sensed something about Louisa. Or maybe he just saw a market opportunity. If there were tales written specifically for boys—adventure tales—why shouldn’t there also be stories about girls’ concerns, written for them? Girls liked reading more than boys did. (This is still true.) So Niles suggested to Louisa that she write a “girls’ story.” She thought this was a stupid idea. “Never liked girls, or knew many, except my sisters,” she wrote in her journal. But her family was terribly strapped, so what she did was write a novel about the few girls she knew, her sisters, and her life with them.

You can get the whole story from a new book, “ Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of ‘Little Women’ and Why It Still Matters ” (Norton), by Anne Boyd Rioux, an English professor at the University of New Orleans. This is a sort of collection of “Little Women” topics: the circumstances that brought Louisa to write the book and the difficult family on which the loving March family is based. It describes the book’s thunderous success: its hundred-and-more editions, its translation into fifty-odd languages (reportedly, it is still the second most popular book among Japanese girls), its sequels, its spinoffs—the Hallmark cards, the Madame Alexander dolls—and, above all, its fabulous sales. Rioux can’t give us a firm count, because in the early days the book was extensively pirated, and then it went into the public domain, but she estimates that ten million copies have been sold, and that’s not including abridged editions. Perhaps worried about how a “girls’ story” would fare in the marketplace, the publisher persuaded Alcott to take a royalty, of 6.6 per cent, rather than a flat fee, which she might well have preferred. In consequence, the book and its sequels supported her and her relatives, plus some of her relatives’ relatives, for the rest of their lives.

Rioux goes on from the book to the plays and the movies. The first “Little Women” play opened in New York, in 1912, and was a hit. It was soon followed by two silent movies, in 1917 and 1918. (Both are lost.) Then came the talkies, starting with George Cukor ’s 1933 version, which cast Katharine Hepburn, hitherto mainly a stage actress, as Jo and helped make her a movie star. Between 1935 and 1950, there were forty-eight radio dramatizations. Toward the end of that run came a second famous movie, Mervyn LeRoy ’s 1949 version, with June Allyson as Jo, Elizabeth Taylor as Amy, Janet Leigh as Meg, and Margaret O’Brien as Beth. In the past few decades, the most important version has been Gillian Armstrong ’s 1994 film, with Winona Ryder as Jo, Kirsten Dunst as Amy, and, as Marmee, Susan Sarandon, who had been enshrined as a feminist icon by “Thelma and Louise.” Recently, it was announced that Greta Gerwig, who had such success last year with “Lady Bird,” her directorial début, is at work on a new “Little Women” movie, with Saoirse Ronan, the star of “Lady Bird,” in the lead role. Ronan seems made to be Jo. And those are just the big-screen versions. By the time Rioux’s book went to press, there had been twelve adaptations for American television, and plenty more elsewhere. In 1987, there was a forty - eight -episode anime version in Japan.

The chapter on the adaptations is a lot of fun. First, it teaches you the problems that face filmmakers adapting famous novels. In “Little Women” movies, the actors are almost always too old, because the directors need experienced people to play these interesting youngsters. June Allyson was thirty-one when she played the fifteen-year-old Jo. Then, partly because the actors are worried that they are too old, they accentuate everything to death. In the Cukor “Little Women,” Katharine Hepburn sometimes looks as though she were going to jump off the screen and sock you in the face, so eager is she to convince you that she is a tomboy. Amy’s vanity is almost always overdone, never more so than by the teen actress Elizabeth Taylor, with a set of blond ringlets that look like a brace of kielbasas. Poor, sickly Beth is almost always sentimentalized; Marmee is often a bore. Whole hunks of the plot may be left out, because this is a twenty-seven-chapter book being squeezed into what is usually a movie of two to three hours.

Rioux apparently finished her book before she could see the most recent entry, a three-hour BBC miniseries directed by a newcomer, Vanessa Caswill . This version’s Jo—Maya Hawke, who had had little acting experience but was blessed with good genes (her parents are Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke)—manages to be Jo-like without being unsexy. Most moving, because the roles are so hard to play, are two other characters. Annes Elwy’s freckle-faced Beth seems to carry her death within her, like an unborn child, from the moment we see her. The movie’s other great standout is Emily Watson, whose features have sometimes seemed too childlike for the roles she has played. Here, as Marmee, she is perfect, both a girl and a mother, her waist a little thicker, her face redder, than what we saw in “ Breaking the Waves ,” in which, at twenty-eight, she became a star. Caswill can’t take her eyes off her, and she gives her an amazing scene that is not in the book. When one of her daughters gives birth—to twins—Marmee is the midwife. At the end of the ordeal, you can read in Watson’s sweaty, exhausted face everything that Alcott hinted at but did not say about how her own mother was left to do everything. Another of Caswill’s additions is a series of dazzling scenes from nature—light-dappled rivers, fat, furry bees circling pink flowers—that could turn you into a Transcendentalist.

Alcott never swerved in her decision not to marry. “I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe,” as she put it. And yet she concluded the first volume of “Little Women” with a betrothal. Meg is proposed to by Laurie’s tutor, John Brook, a good man, and she accepts. Jo, who takes the same position as her creator on the subject of marriage—never!—is scandalized. How could Meg have done such a stupid and heartless thing, and created a breach in the March household? “I just wish I could marry Meg myself, and keep her safe in the family,” she says. The first volume ends with the family adjourning to the parlor, where they all sit and gaze sentimentally at the newly promised couple—all of them, that is, except Jo, who is thinking that maybe something will go wrong and they’ll break up. Now the curtain falls on the March girls, Alcott writes: “Whether it ever rises again, depends upon the reception given the first act of the domestic drama called Little Women.”

This sounds, now, as though she is teasing her readers, knowing full well that she will shortly receive huge bags of mail demanding that she get going on Part 2. In any case, that’s what happened, and the letter writers wanted to know one thing above all: Whom did the girls marry? Meg is taken, but what about Amy and Beth? Most important, what about Jo? Clearly, Jo had to marry Laurie. Everyone was crazy about her, so she had to be given the best, and wasn’t Laurie the best? He was handsome; he was rich; he spoke French; he loved her. In the final scene of Part 1, as everyone is cooing over Meg and John, Laurie, leaning over Jo’s chair, “smiled with his friendliest aspect, and nodded at her in the long glass which reflected them both.” They’re next, obviously.

Not so fast, Alcott wrote in a letter to a friend: “Jo should have remained a literary spinster but so many enthusiastic young ladies wrote to me clamorously demanding that she should marry Laurie, or somebody, that I didn’t dare refuse & out of perversity went & made a funny match for her.” Laurie, as Alcott has been telling us between the lines from the beginning, is a twit. Yes, he is handsome, and rich, but he is not a serious person. He does not, like Jo, think hard about things and fight his way through them in darkness.

So Jo does what she has long known she would have to do. She tells Laurie that she can’t love him otherwise than as a friend. She breaks his heart, insofar as a heart like his can be broken. Then, perhaps to relieve herself of guilt, she takes to thinking that Beth, her favorite sister, is in love with him. Beth has told Jo she has a secret, which she cannot tell her just yet. That must be the secret! That Beth loves Laurie! The thing for Jo to do, then, is to get out of the way. So she takes a job as governess to two children of one of her mother’s friends, who runs a boarding house in New York City.

On her second day there, she is doing her needlework when she hears someone singing in the next room. She pulls aside the curtain and discovers a man named Friedrich Bhaer, who, we are told, was a distinguished professor in his native Germany but is now a tutor of German, poor, and getting on in years (forty). He is stout; his hair sticks out every which way. His clothes are rumpled. He and Jo become friends, but there is a bump in their road. Jo, like her creator, writes lurid tales for the newspaper in order to make money. Bhaer sees some of this writing. “He did not say to himself, ‘It is none of my business,’ ” Alcott writes. He remembered that Jo was young and poor, and “he moved to help her with an impulse as quick and natural as that which would prompt him to put out his hand to save a baby from a puddle.” He tells her that it is wrong to write such trash. Jo has great respect for Professor Bhaer. She listens to what he has to say, goes back to her room, and consigns all her upcoming stories to the fire.

Link copied

Soon, Jo gets the news that Beth is seriously ill. This was Beth’s secret: not that she was in love with Laurie but that she was dying. Jo rushes home and nurses her sister for the short time that remains to her. Beth dies without much protest, whereupon the book sinks for a while into a rather boring peacefulness. The world of the Marches becomes gentle, kind—beige, as it were—as if nothing could bring back the hour of real happiness, so we’re all just going to get used to half measures. Amy is in Europe, where Laurie tracks her down, and the two fall quietly in love, or in like. They marry in Paris. Jo, at home with her parents, tries to content herself by doing the household chores that were once Beth’s. She has nothing else.

Then the novel starts to build toward one of the most satisfying love scenes in our literature. Professor Bhaer suddenly arrives at the March house. He tells Jo that he has been offered a good teaching job in the West, and that he has come to say goodbye. But, strange to say, this formerly untidy man now seems quite soigné, in a new suit and with his hair smoothed down. “Dear old fellow!” Jo says to herself. “He couldn’t have got himself up with more care if he’d been going a-wooing”—whereupon, oh, my God, she suddenly realizes what’s going on. For two weeks, Bhaer calls on her every day. Then, abruptly, he vanishes. One day, two days, three days pass. Jo starts to go crazy. Finally, she runs to town to look for him. It turns out that Bhaer had come in order to find out whether or not Jo was promised to Laurie, and he overheard something that gave him the impression that she was. Now he finds her in some rough part of town—warehouses, counting houses—where, as even he can figure out, she is searching for him. “I feel to know the strong-minded lady who goes so bravely under many horse noses,” he says to her. I don’t know if this is how German-Americans spoke English in the eighteen-sixties, but the two innocents eventually make themselves understood. Jo weeps; Bhaer weeps; the sky weeps. Great sheets of rain come down on them. They stand there in the road, completely drenched, looking into each other’s eyes. “Ah,” Bhaer says. “Thou gifest me such hope and courage, and I haf nothing to give back but a full heart and these empty hands.” “Not empty now,” Jo says, and she puts her hands in his. We then see what we have never seen before in this book, and won’t see again: a serious kiss between a man and a woman.

Ravishing as this is, it still disappointed many of Alcott’s contemporaries, because Jo didn’t marry Laurie. And it has disappointed many of our contemporaries, too, because why did Jo, our hero, have to marry at all, not to speak of marrying a man who told her to stop writing? The problem is made worse by the fact that Alcott herself appeared to vacillate. It seems unlikely that anyone would honor her claim that she came up with a “funny match” for Jo in order to spite the fans who were demanding a marriage plot. But this may actually have been the case, because she goes back and forth about matrimony. On one page, Marmee, the font of all wisdom, tells Meg and Jo that to be loved by a good man is the best thing that can happen to a woman, but, a few sentences later, Marmee says that it is better to be happy old maids than unhappy wives. Which did Alcott believe? Was she just fooling around? If so, she left a lot of confused feminists in her wake. Even more displeased were the queer theorists. In an 1883 interview, Alcott said, “I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body . . . because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with a man.” Hmm. And so we are not surprised that she herself did not marry, but then why did she have to force a husband on her most Louisa-like character, and one who had expressed similar sentiments? (“I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy,” Jo says, in the novel’s first scene.) In recent “Little Women” scholarship, all this bewilderment was compounded by postmodern critics’ emphasis on ambivalence, on conflict, on the dark truths lurking in what had once seemed clean, honest books.

Rioux tries to make everything O.K. by saying that, if Jo married, at least she didn’t make a would-be romantic match, the kind that women have been historically bamboozled by, but a “companionate union.” Elizabeth Lennox Keyser, a children’s-literature scholar, has offered a more negative view: “Seeing no way to satisfy self, she adopts a policy of selflessness and, thus diminished, succumbs to the marriage proposal of fatherly Professor Bhaer.” Both interpretations assume that Jo, by marrying someone old and fat—a foreigner, too!—doesn’t so much take a husband as find a nice person to room with. I think that the situation is exactly the opposite, and that a “diminished” girl does not go running through the town, under so many horse noses, to find a booby prize. The heavens do not burst open when Meg says yes to John, or Amy to Laurie, but only when Jo and Bhaer, these two souls with no money or beauty or luck, come together.

There are other clues that Bhaer is a character very close to Alcott’s heart. When Jo, on her second day in New York, hears the professor singing in the next room, Alcott tells us what the song is. It was originally sung by a strange little character, Mignon, in Goethe’s 1795 novel, “ Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship .” Mignon is a girl dressed as a boy, who, having been kidnapped in her native Italy by a gang of ruffians, is travelling with a troupe of actors. They treat her badly. She appeals to Wilhelm Meister to rescue her. Here, in Thomas Carlyle’s translation, is the start of the poem, “Kennst Du das Land,” that she sings to him:

Know’st thou the land where lemon-trees do bloom, And oranges like gold in leafy gloom; A gentle wind from deep blue heaven blows, The myrtle thick, and high the laurel grows? Know’st thou it, then? ’Tis there! ’tis there, O my belov’d one, I with thee would go!

At first, it sounds as though Mignon is asking Wilhelm to take her back to Italy, but as the poem proceeds it becomes clear that she means someplace farther away. (She dies at the end of the book.) The poem was set to music by dozens of composers in the nineteenth century. Alcott does not tell us which version Bhaer is singing. All we know is that he is speaking of some lost paradise—such as, for example, the Eden that Bronson Alcott tried to emulate at Fruitlands. Goethe was an idol of the members of the Transcendental Club, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Emerson, generous as ever, had given Louisa the run of his library when she was in her teens. There she found a translation of a book, “ Goethe’s Correspondence with a Child ,” a collection of enraptured letters to the revered master from a young admirer, Bettina von Arnim. Louisa decided that she, likewise, would write a “heart-journal.” She would take the part of Bettina, and her correspondent would be Emerson, whom she adored. Years later, in her diary, she recalled, “I wrote letters to him, but never sent them; sat in the tall cherry-tree at midnight, singing to the moon till the owls scared me to bed; left wild flowers on the doorstep of my ‘Master,’ and sang Mignon’s song under his window in very bad German.”

When Bhaer arrives to visit the Marches, Jo asks him to sing “Kennst Du das Land” again. The first line, Alcott writes, was once Bhaer’s favorite, because, before, “das Land” to him meant Germany, his homeland. “But now,” Alcott writes, “he seemed to dwell, with peculiar warmth, and melody, upon the words ‘There, there, might I go with thee / O, my beloved, go’ and one listener was so thrilled by the tender invitation that she longed to say that she did know the land,” and was ready to start packing. These, I believe, are the fragments still floating in the air of “Little Women” after the combustion that, in Alcott’s brain, produced Professor Bhaer, a lover for her most cherished character. He is not a “funny match.” He, together with Beth, is a sort of angel, like the souls in the Divine Comedy, beings who turn to us and say exactly who they are and what they stand for.

Behind these two angelic beings stands another, this one not a literary character but a real person: Bronson Alcott. It is hard to like Bronson, because he took so little care of his family. For a long time, Louisa appears to have despised him, or at least regarded him with considerable irony. She once wrote to him that her goal in her work was to prove that “though an Alcott I can support myself.” It would be hard to find an English-language work of fiction more autobiographical than “Little Women.” For almost every person in Louisa’s immediate family, there is a corresponding character, an important one, in this book. The one exception is Bronson. Father March comes home from the war, stumbles into the back room, and thereafter mostly stays offstage, reading books. Occasionally, he wanders in and says something or other. Then he wanders back out. In one sense, we could say that Louisa erased him—a sort of revenge, perhaps. In another sense, this may just be an erasure of her feelings about him: she didn’t want to talk about it.

Yet, while Bronson was more or less written out of the book, the ideals to which he held so stubbornly inform every page. Bronson’s obsession was with the transcendence of the material world, with seeing through appearances to a moral and spiritual truth. He took this passion to extremes, and that is what made him eccentric, not to speak of irresponsible. But that is also the cast of mind that, with the addition of common sense and humor and an attachment to regular things—life, family, dinner—makes Alcott’s most admirable characters admirable.

In addition to supplying the book’s moral architecture, Bronson provided, by his neglect, the need for its creation. Louisa’s one wish, as an adult, was to make her mother’s life comfortable. With “Little Women” she did it, and then, with the work’s two sequels—“ Little Men ” (1871) and “ Jo’s Boys ” (1886), both having to do with a school that Jo and Bhaer eventually establish—she did it some more. When she was in the middle of a book, she wrote “in a vortex,” as she put it, often remaining at her desk for fourteen hours a day. “Little Women” was written in less than six months. “Her health is by no means yet restored,” Bronson wrote philosophically in his journal in 1869, soon after the book’s publication. But it didn’t bother him that she had just about killed herself to write it. In the words of his excellent biographer, John Matteson, Bronson regarded a physical person as “a lapsed soul, a debased descendant of pure being.” A soul did not need to go to bed. A soul could work fourteen hours a day.

Louisa eventually developed chronic health problems, and her exhaustion showed in her work. “Little Men” is occasionally touching. You cry, and you wish you hadn’t, because the book also feels like “ The Three Bears ,” with the plumped-up beds all in a row. As for “Jo’s Boys,” it is actually a chore to read. Alcott tries to whip up some excitement—there is a shipwreck, an explosion in a mine—but you can sense how bored she is, and how much she wants to go upstairs and take a nap.

In time, Louisa seems to have forgiven her father. At the age of fifty-five, she went to visit him at the convalescent home where he was then living (at her expense, no doubt). Kneeling at his bedside, she said, “Father, here is your Louy. What are you thinking of as you lie here so happily?” “I am going up ,” he said. “ Come with me .” She obliged him. Three days after their conversation, Bronson breathed his last. But Louisa never knew of it; she was in a coma, after a stroke, and died two days after him.

Of some novelists it is said that they had only one book in them, or only one outstanding book. Such novels tend to have certain things in common. They are frequently autobiographical: Thomas Wolfe’s “ Look Homeward, Angel ,” Sybille Bedford’s “ A Legacy ,” Betty Smith’s “ A Tree Grows in Brooklyn .” And they often have a force or a charisma, an ability to get under your skin and stay there, that other books, even many better-written books, don’t have. Some people complain that university syllabuses don’t accord “Little Women” the status of “Huckleberry Finn,” which they see as its male counterpart. But no piece of literature is the counterpart of “Little Women.” The book is not so much a novel, in the Henry James sense of the term, as a sort of wad of themes and scenes and cultural wishes. It is more like the Mahabharata or the Old Testament than it is like a novel. And that makes it an extraordinary novel. ♦

An earlier version of this piece misstated the name of Meg March’s suitor.

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to c. 500 AD)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Books for Toddlers and Babies

- Books for Preschoolers

- Books for Kids Age 6-8

- Books for Kids Age 9-12

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2024

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2024

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2024

- Best Kids' Books of 2024

- Mystery & Crime

- Travel Writing

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- NBCC Awards (biography & memoir)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

- Wilbur Smith Prize (adventure)

The Best Fiction Books

Little women, by louisa may alcott.

This classic work contains a powerful message to young women, namely that they do not have to marry in order to achieve success.

Recommendations from our site

“This book is about a family of four American sisters, living in genteel poverty during the American Civil War…..The March sisters have grown up together and I think it’s interesting when you see the tension between the fact that they have a shared upbringing and shared values, and yet they are such obviously different personalities that they can have disagreements. They don’t just agree about everything, and they’re forceful and vocal in their disagreement, but the book is still built upon the strength of the bond between them. I find that interesting, that you can have conflict and love and support all wrapped up in that relationship, and I think it’s really a tender look at the dynamic between the four of them..” Read more...

The Best Coming-of-Age Novels About Sisters

Laura Wood , Children's Author

“Marmee is a character that really resonates for me. She’s obviously not Chinese, but she believes that integrity and hard work are the most important things in life. She holds her daughters to very high standards. She doesn’t sugarcoat much. She also reveals to her rebellious daughter Jo, the star of the book and a character loosely modeled on Louisa May Alcott herself, that she had a bad temper too when she was younger. That’s exactly what I did with my own daughter Louisa…….The kinds of mistakes that Marmee allows her daughters to make are very similar to the kinds of mistakes that I allow my daughters to make.” Read more...

The best books on Being a Mother

Amy Chua , Lawyer

“This is an iconic American text. It was written in the years immediately following the American Civil War. Alcott presents a portrait of a northern family of women managing on their own while their husband/father is serving as an army chaplain. This classic work contains a powerful message to young women, namely that they do not have to marry in order to achieve success. Jo is one of the first in a long line of what might be described as ‘plucky’ heroines who follow their own destiny. She doesn’t end up marrying her leading man in this book although she finally does in a later volume.” Read more...

The best books on The History of American Women

Jay Kleinberg , Historian

Our most recommended books

Jane eyre by charlotte brontë, middlemarch by george eliot, dracula by bram stoker, beloved by toni morrison, war and peace by leo tolstoy, frankenstein (book) by mary shelley.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

Adventures in reading

Little Women: Book Review

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.

It’s very much a domestic novel. Most of the action takes place either in the March’s home or in other homes close by and many of the episodes revolve around domestic activities like cleaning, cooking and sewing. It’s not until Good Wives that the March daughters get to venture further away from the family home.

Given the target audience it’s not surprising that the central characters are mainly female. Men don’t get much of a look in in this novel. They’re outnumbered and some of them are conspicuously absent (most notably Mr March who is serving as a chaplain in the Civil War). When they do make an appearance they seem to a hapless lot, suffering from broken hearts or physical injuries and utterly reliant on the women to sustain and care for them. There’s the family neighbour Mr Lawrence, who is grieving over the death of his daughter but finds solace in the gentleness of young Beth March. There’s Mr March who has to be nursed back to health by the love of his wife and daughters on his return from the war. And then there is the March girls’ new-found friend Laurie, who prefers the warmth and affection of the March home than the richness of his grandfather’s mansion.

The men seem rather insignificant and drippy in comparison to the strong individuals who comprise the female side of the March family. Although Alcott confided to her journal that she “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters” she succeeded in creating girls to whom her readers could relate. Apparently she used her own sisters as models for the four sisters and used a lot of her own experiences and attitudes to develop the character of the second eldest girl Jo March. This vivacious, intelligent girl who cares nothing for outward appearance, struggles repeatedly against her tendency to lose her temper and to hold a grudge. Her sisters (the other ‘little women’) have their fans too — Amy, the proud artistic sister with a passionate interest in her own appearance and in being popular; Meg, the eldest girl who becomes the closest in temperament to her mother; and little Beth, the shy and fragile girl whose disposition is always sweet and selfless.

It’s the trials and tribulations of these girls as they grow into adulthood and deal with the difficulties posed by lack of wealth, that form the focus of the book. It’s told in a series of episodes, some amusing, some touching, in which they win friends, make their own fun, fall in love and worry about their absent father.

But if you think this book is simply about a series of entertaining episodes. This is a book that has a serious purpose. It’s meant to instruct not merely to amuse. If you’re in any doubt about this, look at the Preface which alludes to John Buynan’s Pilgrims Progress and expresses a wish that the novel might affect its readers to the point that “they choose to be Pilgrims better.”

So even before we get to page 1, the didactic nature of the book is evident. And just in case young readers miss the point, it’s reinforced early in Chapter 1 where Mrs March reminds the girls how much they loved playing as pilgrims in their younger days and encourages them to take up their journey again.

We are never too old for this… because it is a play we are playing all the time in one way or another. Our burdens are here, our road is before us and the longing for goodness and happiness is the guide that leads us through many troubles and mistakes to the peace which is a true Celestial City.

The Christian overtone means that Little Women can be seen as part of a long tradition of improving literature for children. Also in keeping with the cultural norm of mid nineteenth century society, is the fact that it’s the mother figure who takes on the role of guide and mentor (a reflection of the ideology about the traditional role of women as nurturer.) Hence we see it’s Mrs March, a strong and confident woman herself, who seeks to teach her daughters – and through them, young female readers – how to be happy and fulfilled individuals. Not for Mrs March are the outward accoutrements of wealth or status; what she wants for her daughters is the contentment that comes from self respect and love:

Money is a needful and precious thing, and when well used, a noble thing, but I never want you to think it is the first or only prize to strive for. I’d rather see you poor men’s wives, if you were happy, beloved, contented, than queens on thrones, without self-respect and peace.

Whenever one of the girls gets into difficulties, Mrs March always seems on hand to provide some wise words and to dole out another of life’s lessons. In one episode, a disastrous attempt by the girls to take over the cooking and cleaning, ends with Marmee teaching them the dangers of thinking only of themselves:

I thought, as a little lesson, I would show you what happens when everyone thinks only of herself. Don’t you feel that it is pleasanter to help one another, to have daily duties which make leisure sweet when it comes, and to bear and forbear, that home may be comfortable and lovely to us all?

Similar scenes happen again and again throughout the book so that by the halfway mark, I felt I was drowning in saccharin.

Clearly, the passage of time has not helped here. My advancing years have made me more critical and, I will admit it, more cynical also. Reading the book as a child I don’t remember noticing the sentimental, sermonising tone — I was too caught up in the tomboy antics of my favourite character, Jo — but reading it again as an adult I found the little homilies from Marmee became too predictable an element of the story. The sermonising was so overt I could not ignore it, which consequently robbed me of interest in the novel. I know the book has a huge fan club. But I shall not be signing up for membership.

Bits and pieces

- Alcott never anticipated her book would prove popular. In her journal she wrote that ” our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”

- if you have a hankering to own an early edition of the novel, you’ll need deep pockets. A hardback copy of a first edition will set you back $25,000.

- After the success of Little Women and Good Wives, Alcott went on to write twice more about the March family in Little Men and then Jo’s Boys

- Alcott became active in the women’s suffrage movement and canvassing door to door trying to encourage women to register to vote.

- Despite the homely image of an author conjured up by Little Women, Alcott was a prolific writer of a vastly different kind of fiction – under the pen name A M Banard, she wrote sensation style stories for several magazines. Behind the Mask is one I would recommend.

Thanks for sharing

- What kind of heroine are you?

- Classic Club: Favourite opening sentence

What do you need to know about me? 1. I'm from Wales which is one of the countries in the UK and must never be confused with England. 2. My life has always revolved around the written and spoken word. I worked as a journalist for nine years then in international corporate communications 3. My tastes in books are eclectic. I love realism and hate science fiction and science fantasy. 4. I am trying to broaden my reading horizons geographically by reading more books in translation

17 thoughts on “ Little Women: Book Review ”

Pingback: Ten Hard To Forget Bookish Characters In Fiction : BookerTalk

Hi Karen. Of those insignificant and drippy men Alcott could not entirely ignore…I always chuckled a bit when she, on more than one occasion, referred to the entire male gender as “the lords of creation”…dripping not with contempt, but irony. She was a magnificent writer, ahead of her time…truly Alcott’s own Marmee was ahead of her time, but the novel remains timeless. Marvelous review! My review: https://tinyurl.com/yb9gq6h2

I prefer some of the sensationalist material she wrote though I understand how immensely popular Little Women was

Pingback: 10 literary mothers – the good, the bad and the ugly | BookerTalk

Pingback: Little Women | Dewey Decimal's Butler

Really excellent review 🙂 This was the one book I revisited every time I went to the library as a child and your review has made me want to revisit all over again!

now you’ve got me thinking whether I have any childhood favourites….

I read this for the first time last year. I thought it was really lovely and only wish I had read it as a child!

I think it’s best read as a child so the. I didn’t notice all the sermons so much

Never read this classic. As a child, I was busy with other books, and then never dipped into as an adult. I think I would have found the language too stuffy as a kid. Interesting review — particularly the overtones.

There are a lot of books now considered classics of children’s lit that I never got to read either. C s Lewis Narnia series for one.

Have you read Geraldine Brooks novel,’March’, which gives a very interesting rethink to the family? I enjoyed it, but I know it wasn’t to everyone’s taste. If you want to read Alcott in her real didactic mode, then do read ‘Eight Cousins’ and ‘Rose in Bloom’. She is very definite there about how girls ought to be educated.

I confess not to have read anything by Brooks so far. Nor the other Alcott stories. I was hoping to find her sensation stories but Gutenburg doesn’t have them unfortunately.

Sent from my iPad

Wonderful review! I loved this book.

Thanks for taking the time to comment. Responding to comments is the fun part of blogging

This is a classic I really need to go back and re-read. I remember being determined to read it in 5th grade after my teacher told me I couldn’t. So I did. I adored it, but I definitely feel like I missed quite a bit because of my age.

Wonder why she told you that you couldn’t read it. Couldn’t have been that she thought the subject inappropriate so I’m baffled at her attitude.

We're all friends here. Come and join the conversation Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from BookerTalk

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

After 150 years, 'little women' still resonates.

Ilana Masad

Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

About once a year I turn to one particularly tattered book, its red cover worn, its two halves taped together after falling apart from frequent use years ago.