Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Education, training and skills

- Pupil wellbeing, behaviour and attendance

A review of the literature on anxiety for educational assessments

This review pulls together statistics and academic literature relating to the causes, symptoms and effects of assessment-related anxiety.

Applies to England

A review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments.

PDF , 770 KB , 63 pages

This file may not be suitable for users of assistive technology.

This review is part of a wider collection of material focused on managing test anxiety. It pulls together statistics and academic literature relating to the causes, symptoms and effects of assessment-related anxiety, known as test anxiety in the literature. It is an academic piece of writing that considers what is currently known about test anxiety, by drawing on existing evidence and research, and may be of particular interest to specialists and practitioners working in the field.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

Supporting Student Success: The Role of Test Anxiety, Emotional Intelligence, and Multifaceted Intervention

- First Online: 11 November 2022

Cite this chapter

- Christopher L. Thomas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6804-5318 4 ,

- Kristie Allen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0061-6107 5 ,

- Clara Madison Morales ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5971-5631 4 &

- Jaren Mercer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5545-3504 4

1553 Accesses

1 Citations

Test anxiety is a complex cognitive-motivational phenomenon that impairs the academic performance of learners at all educational levels. Effectively supporting test-anxious students requires understanding the environmental and internal factors that elicit and perpetuate test anxiety. As such, one of the aims of the chapter is to provide an overview of the role of situational appraisal, self-knowledge, and controlled processing in maladaptive reactions to evaluative events as outlined in the Self-Regulatory Executive Function Processing Model. Further, we highlight the role of enduring personality dispositions and emotion-focused self-perceptions (i.e., dimensions of trait emotional intelligence) in test anxiety. Finally, we seek to provide educators with practical ideas about how to reduce test anxiety based on decades of theoretical and applied research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abdollahi, A., & Abu Talib, M. (2015). Emotional intelligence moderates perfectionism and test anxiety among Iranian students. School Psychology International, 36 (5), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315603445

Article Google Scholar

Aldridge, A. A., & Roesch, S. C. (2008). Developing coping typologies of minority adolescents: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 31 (4), 499–517.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Archambault, I., & Dupéré, V. (2017). Joint trajectories of behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in elementary school. The Journal of Educational Research, 110 (2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1060931

Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D., & Mastoras, S. M. (2010). Emotional intelligence, coping, and exam-related stress in Canadian undergraduate students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 52 , 42–50.

Axelson, R. D., & Flick, A. (2010). Defining student engagement. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 43 (1), 38–43.

Bardi, A., & Guerra, V. M. (2011). Cultural values predict coping using culture as an individual difference variable in multicultural samples. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42 (6), 908–927.

Bandura, A. (2005). The evolution of social cognitive theory. In K. G. Smith & M. A. Hitt (Eds.), Great minds in management (pp. 9–35). Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bar-On, R. (1997). The emotional intelligence inventory (EQ–i): Technical manual . Multi-Health Systems.

Ben-Eliyahu, A., Moore, D., Dorph, R., & Schunn, C. D. (2018). Investigating the multidimensionality of engagement: Affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement across science activities and contexts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53 , 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.01.002

Benjamin, M., McKeachie, W. J., Lin, Y., & Holinger, D. P. (1981). Test anxiety: Deficits in information processing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73 , 816–824.

Boyle, C. C., Stanton, A. L., Ganz, P. A., Crespi, C. M., & Bower, J. E. (2017). Improvements in emotion regulation following mindfulness meditation: Effects on depressive symptoms and perceived stress in younger breast cancer survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85 (4), 397–402.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Blankstein, K. R., Flett, G. L., Boase, P., & Toner, B. B. (1990). Thought listing and endorsement measures of selfreferential thinking in test anxiety. Anxiety Research, 2 (2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(89)90001-9

Bracken, B. A., & Brown, E. F. (2006). Behavioral identification and assessment of gifted and talented students. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 24 (2), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282905285246

Brand, S., Ahmadpanah, M., Keshavarz, M., Haghighi, M., Jahangard, L., Bajoghli, H., Sadeghi Bahmani, D., & Holsboer-Trachsler, E. (2016). Higher emotional intelligence is related to lower test anxiety among students. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 1 , 133–136. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s98259

Cao, T. H., Jung, J. Y., & Lee, J. (2017). Assessment in gifted education: A review of the literature from 2005 to 2016. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28(3) , 163–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X17714572

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1988). A control-process perspective on anxiety. Anxiety Research, 1 (1), 17–22.

Cassady, J. C. (2004). The influence of cognitive test anxiety across the learning–testing cycle. Learning and Instruction, 14 (6), 569–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.09.002

Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27 (2), 270–295. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1094

Cassady, J. C., & Thomas, C. L. (2020). Identifying and supporting students with affective disorders in schools: Academic anxieties and emotional information processing. In A. J. Martin, R. A. Sperling, & K. J. Newton (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology and students with special needs (pp. 52–74). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cassady, J. C., & Boseck, J. J. (2008). Educational psychology and emotional intelligence: Toward a functional model for emotional information processing in schools. In J. C. Cassady & M. A. Eissa (Eds.), Emotional intelligence: Perspectives of educational and positive psychology (pp. 3–24).

Cizek, G., & Burg, S. (2006). Addressing test anxiety in a high-stakes environment . Corwin Press.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social-information processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115 , 74–101.

Daly, A. L., Chamberlain, S., & Spalding, V. (2011). Test anxiety, heart rate and performance in A-level French speaking mock exams: An exploratory study. Educational Research, 53 (3), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2011.598660

Deming, D. J., & Figlio, D. (2016). Accountability in US education: Applying lessons from K-12 experience to higher education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30 (3), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.33

Depreeuw, E. A. M. (1984). A profile of the test anxious student. International Review of Applied Psychology, 33 , 221–232.

Dyson, R., & Renk, K. (2006). Freshman adaption to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62 , 1231–1244.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61 , 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7 (2), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336

Eysenck, M. W., & Derakshan, N. (2011). New perspectives in attentional control theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 50 (7), 955–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.019

Federici, R. A., Skaalvik, E. M., & Tangen, T. N. (2015). Students’ perceptions of the goal structure in mathematics classrooms: Relations with goal orientations, mathematics anxiety, and help-seeking behavior. International Education Studies, 8 (3), 146–158.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48 (1), 150–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

Frederickson, N., Petrides, K. V., & Simmonds, E. (2012). Trait emotional intelligence as a predictor of socioemotional outcomes in early adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences, 52 , 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.034

Friedman, I. A., & Bendas-Jacob, O. (1997). Measuring perceived test anxiety in adolescents: A self-report scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57 (6), 1035–1046. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164497057006012

Galassi, J. P., Frierson, H. T., & Sharer, R. (1981). Behavior of high, moderate, and low test anxious students during an actual test situation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49 (1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.49.1.51

Giacobbi, P. R., Lynn, T. K., Wetherington, J. M., Jenkins, J., Bodendorf, M., & Langley, B. (2004). Stress and coping during the transition to university for first-year female athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 18 (1), 1–20.

Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cognitive Psychology, 15 , 1–38.

Hembree, R. (1988). Correlates, causes, effects, and treatment of test anxiety. Review of Educational Research, 58 (1), 47–77. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543058001047

Hultberg, P., Calonge, D. S., & Lee, A. E. S. (2018). Promoting long-lasting learning through instructional design. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 18 (3), 26–43. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v18i3.23179

Johns, M., Inzlicht, M., & Schmader, T. (2008). Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: Examining the influence of emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137 , 691–705.

Kern, C. L., & Crippen, K. J. (2017). The effect of scaffolding strategies for inscriptions and argumentation in a science cyberlearning environment. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 26 (1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-016-9649-x

Lane, S., Raymond, M. R., & Haladyna, T. M. (2016). Handbook of test development (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Lang, P., Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), E motional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). Basic Books.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping . Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1 , 141–169.

Leckie, G., & Goldstein, H. (2019). The importance of adjusting for pupil background in school value‐added models: A study of Progress 8 and school accountability in England. British Educational Research Journal, 45(3) , 518–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3511

Liebert, R. M., & Morris, L. W. (1967). Cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety: A distinction and some initial data. Psychological Reports, 20 , 975–978. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1967.20.3.975

Lovett, B. J., & Nelson, J. M. (2017). Test anxiety and the Americans with disabilities act. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 28 (2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207317710699

Lowe, P. A. (2019). Examination of test anxiety in samples of Australian and US higher education students. Higher Education Studies, 9 (4), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v9n4p33

Lowe, P. A. (2021). The test anxiety measure for college students-short form: Development and examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 39 (2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282920962947

Lowe, P. A., Lee, S. W., Witteborg, K. M., Prichard, K. W., Luhr, M. E., Cullinan, C. M., et al. (2008). The test anxiety inventory for children and adolescents (TAICA) examination of the psychometric properties of a new multidimensional measure of test anxiety among elementary and secondary school students. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 26 (3), 215–230.

Maguire, R., Egan, A., Hyland, P., & Maguire, P. (2017). Engaging students emotionally: The role of emotional intelligence in predicting cognitive and affective engagement in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 36 (2), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1185396

Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Morin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49 (6), 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.029

Matthews, G., Hillyard, E. J., & Campbell, S. E. (1999). Metacognition and maladaptive coping as components of test anxiety. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6 , 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199905)

Matthews, G., & Wells, A. (2004). Rumination, depression, and metacognition: The S-REF model. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Rumination: Nature, theory, and treatment (pp. 125–151). Wiley.

Mavroveli, S., & Sanchez-Ruiz, M. J. (2011). Trait emotional intelligence influences on academic achievement and school behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81 , 112–134. https://doi.org/10.1348/2044-8279.002009

Mikolajczak, M., Roy, E., Luminet, O., Fillée, C., & De Timary, P. (2007). The moderating impact of emotional intelligence on free cortisol responses to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32 (8–10), 1000–1012.

Mikolajczak, M., Bodarwé, K., Laloyaux, O., Hansenne, M., & Nelis, D. (2010). Association between frontal EEG asymmetries and emotional intelligence among adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 48 (2), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.001

Mikolajczak, M., Avalosse, H., Vancorenland, S., Verniest, R., Callens, M., Van Broeck, N., et al. (2015). A nationally representative study of emotional competence and health. Emotion, 15(5), 653. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000034

Morris, L. W., & Liebert, R. M. (1970). Relationship of cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety to physiological arousal and academic performance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 35 (3), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030132

Morris, L. W., Davis, M. A., & Hutchings, C. H. (1981). Cognitive and emotional components of anxiety: Literature review and a revised worry–emotionality scale. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73 (4), 541–555. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.4.541

Nairn, R. C., & Merluzzi, T. V. (2019). Enhancing coping skills for persons with cancer utilizing mastery enhancement: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42 (3), 423–439.

Naveh-Benjamin, M. (1991). A comparison of training programs intended for different types of test-anxious students: Further support for an information-processing model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83 (1), 134.

Naveh-Benjamin, M., McKeachie, W. J., & Lin, Y. (1987). Two types of test-anxious students: Support for an information processing model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79 , 131–136.

Newton, P. E. (2007). Clarifying the purposes of educational assessment. Assessment in Education, 14 (2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940701478321

Nonis, S. A., & Hudson, G. I. (2010). Performance of college students: Impact of study time and study habits. Journal of Education for Business, 85 (4), 229–238.

O’Carroll, P. J., & Fisher, P. (2013). Metacognitions, worry and attentional control in predicting OSCE performance test anxiety. Medical Education, 47 (6), 562–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12125

OECD. (2008). Measuring improvements in learning outcomes: Best practices to assess the value-added of schools (Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing & Centre for Educational Research and Innovation). OECD.

Book Google Scholar

Okpala, A. O., Okpala, C. O., & Ellis, R. (2000). Academic efforts and study habits among students in a principles of macroeconomics course. Journal of Education for Business, 75 (4), 219–224.

Owens, M., Stevenson, J., Norgate, R., & Hadwin, J. A. (2008). Processing efficiency theory in children: Working memory as a mediator between trait anxiety and academic performance. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 21 (4), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701847823

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37 (2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Perry, R. P., Kramer, K., Hochstadt, M., & Molfenter, S. (2004). Beyond test anxiety: Development and validation of the test emotions questionnaire (TEQ). Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 17 (3), 287–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800412331303847

Peltier, C., & Vannest, K. J. (2017). A meta-analysis of schema instruction on the problem-solving performance of elementary school students. Review of Educational Research, 87 (5), 899–920. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317720163

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15 (6), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.416

Petrides, K. V., Pérez, J. C., & Furnham, A. (2003, July). The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): A measure of emotional self–efficacy . Paper presented at the 11th Biennial Meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Individual Differences (ISSID). Graz, Austria.

Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N., & Furnham, A. (2004). The role of trait emotional intelligence in academic performance and deviant behavior at school. Personality and Individual Differences, 36 , 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00084-9

Petrides, K. V., Pérez-González, J. C., & Furnham, A. (2007a). On the criterion and incremental validity of trait emotional intelligence. Cognition and Emotion, 21 (1), 26–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930601038912

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., & Kokkinaki, F. (2007b). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology, 98 , 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X120618

Petrides, K. V., Hudry, K., Michalaria, G., Swami, V., & Sevdalis, N. (2011). A comparison of the trait emotional intelligence profiles of individuals with and without Asperger syndrome. Autism, 15 , 671–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310397217

Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sanchez-Ruiz, M. J., Furnham, A., & Pérez-González, J. C. (2016). Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emotion Review, 8 (4), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916650493

Petrides, K. V., Sanchez-Ruiz, M., Siegling, A. B., Saklofske, D. H., & Mavroveli, S. (2018). Emotional intelligence as personality: Measurement and role of trait emotional intelligence in educational contexts. In K. V. Keefer, J. D. A. Parker, & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), Emotional intelligence in education: Integrating research with practice (pp. 49–81). Springer Nature.

Phye, G. D. (1990). Inductive problem solving: Schema inducement and memory-based transfer. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (4), 826–831. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.826

Preiss, R. W., Gayle, B. M., & Allen, M. (2006). Test anxiety, academic self-efficacy, and study skills: A meta-analytic review. In Classroom communication and instructional processes: Advances through meta-analysis (pp. 99–111). Routledge.

Putwain, D. W. (2008). Deconstructing test anxiety. Educational and Behavioral Difficulties, 13 , 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750802027713

Putwain, D. W., & Daly, A. L. (2014). Test anxiety prevalence and gender differences in a sample of English secondary school students. Educational Studies, 40 , 554–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2014.953914

Putwain, D. W., & Symes, W. (2014). The perceived value of maths and academic self-efficacy in the appraisal of fear appeals used prior to a high-stakes test as threatening or challenging. Social Psychology of Education, 17 (2), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9249-7

Putwain, D. W., & Symes, W. (2016). The appraisal of value-promoting messages made prior to a high-stakes mathematics examination: The interaction of message-focus and student characteristics. Social Psychology of Education, 19 (2), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9337-y

Putwain, D. W., & von der Embse, N. P. (2018). Teachers use of fear appeals and timing reminders prior to high-stakes examinations: Pressure from above, below, and within. Social Psychology of Education, 21 , 1001–1019.

Putwain, D. W., Woods, K. A., & Symes, W. (2010). Personal and situational predictors of test anxiety of students in post-compulsory education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80 (1), 137–160.

Putwain, D. W., Shah, J., & Lewis, R. (2014). Performance-evaluation threat does not always adversely affect verbal working memory in high test anxious persons. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 13 , 120–136. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.13.1.120

Putwain, D. W., Symes, W., & Wilkinson, H. M. (2017). Fear appeals, engagement, and examination performance: The role of challenge and threat appraisals. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 , 16–31.

Putwain, D. W., & Symes, W. (2020). The four Ws of test anxiety: What is it, why is it important, where does it come from, and what can be done about it? Psychologica, 63 , 31–52. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8606_63-2_2

Riley, H., & Schutte, N. S. (2003). Low emotional intelligence as a predictor of substance-use problems. Journal of Drug Education, 33 , 391–398. https://doi.org/10.2190/6DH9-YT0M-FT99-2X05

Romano, L., Tang, X., Hietajärvi, L., Salmela-Aro, K., & Fiorilli, C. (2020). Students’ trait emotional intelligence and perceived teacher emotional support in preventing burnout: The moderating role of academic anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (13), 4771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134771

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Roos, A. L., Goetz, T., Voracek, M., Krannich, M., Bieg, M., Jarrell, A., & Pekrun, R. (2021). Test anxiety and physiological arousal: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33 (2), 579–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09543-z

Saklofske, D. H., Austin, E. J., Galloway, J., & Davidson, K. (2007). Individual difference correlates of health-related behaviors: Preliminary evidence for links between emotional intelligence and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 42 , 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.006

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D., & Yoo, S. H. (2009). The positive psychology of emotional intelligence. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 237–248). Oxford University Press.

Sanchez-Ruiz, M. J., Mavroveli, S., & Poullis, J. (2013). Trait emotional intelligence and its links to university performance: An examination. Personality and Individual Differences, 54 , 658–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.013

Sarason, I. G. (1960). Empirical findings and theoretical problems in the use of anxiety scales. Psychological Bulletin, 57 (5), 403–415.

Sarason, I. G. (1984). Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference: Reactions to tests. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46 , 929–938.

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review, 115 , 336–356.

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., et al. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25 , 167–177.

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., & Hine, D. W. (2011). The association of ability and trait emotional intelligence with alcohol problems. Addiction Research and Theory, 19 , 265–265. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2010.512108

Schwarzer, R. (1996). Thought control of action: Interfering self-doubts. In I. G. Sarason, G. R. Pierce, & B. R. Sarason (Eds.), Cognitive interference: Theories, methods, and findings (pp. 99–115). Guilford Publications.

Segool, N. K., Carlson, J. S., Goforth, A. N., Von Der Embse, N., & Barterian, J. A. (2013). Heightened test anxiety among young children: Elementary school students’ anxious responses to high-stakes testing. Psychology in the Schools, 50 (5), 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21689

Segool, N. K., von der Embse, N., Mata, A. D., & Gallant, J. (2014). Cognitive behavioral model of test anxiety in a high-stakes context: An exploratory study. School Mental Health, 6 (1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-013-9111-7

Seipp, B. (1991). Anxiety and academic performance: A meta-analysis of findings. Anxiety Research, 4 (1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08917779108248762

Sirois, F. M., & Hirsch, J. K. (2013). Associations of psychological thriving with coping efficacy, expectations for future growth, and depressive symptoms over time in people with arthritis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 75 (3), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.06.004

Siu, A. F. (2009). Trait emotional intelligence and its relationships with problem behavior in Hong Kong adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 47 (6), 553–557.

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez, H. P., Taylor, D. J., Algaze, B., & Anton, W. D. (1978). Examination stress and test anxiety. In C. D. Spielberger & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Stress and anxiety (Vol. 5). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.022

Suinn, R. M. (1984). Generalized anxiety disorder. In S. M. Turner (Ed.), Behavioral theories and treatment of anxiety (pp. 279–320). Plenum Press.

Symes, W., & Putwain, D. W. (2020). The four Ws of test anxiety. Psychologica, 63 (2), 31–52.

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. In J. P. Mestre & B. H. Ross (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 37–76). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12387691-1.00002-8

Thomas, C. L., & Allen, K. (2021). Driving engagement: Investigating the influence of emotional intelligence and academic buoyancy on student engagement. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45 , 107–119.

Thomas, C. L., & Cassady, J. C. (2019). The influence of personality factors, value appraisals, and control appraisals on cognitive test anxiety. Psychology in the Schools, 56 , 1568–1582.

Thomas, C. L., Cassady, J. C., & Heller, M. (2017). The influence of emotional intelligence, cognitive test anxiety, and coping strategies on undergraduate performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 55 , 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.03.001

Thomas, C. L., Cassady, J. C., & Heath, J. (2020). Examining the psychometric properties of the FRIEDBEN test anxiety scale using exploratory structural equation modeling. International Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 8 , 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2018.1522281

Uphill, M. A., Rossato, C. J., Swain, J., & O’Driscoll, J. (2019). Challenge and threat: A critical review of the literature and an alternative conceptualization. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 1255. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01255

Veenman, M. V. J., Kerseboom, L., & Imthorn, C. (2000). Test anxiety and metacognitive skillfulness: Availability versus production deficiencies. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 13 , 391–412.

von der Embse, N. P., & Putwain, D. W. (2015). Examining the context of instruction to facilitate student success. School Psychology International, 36 (6), 552–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315612144

von der Embse, N. P., Kilgus, S. P., Segool, N., & Putwain, D. (2013). Identification and validation of a brief test anxiety screening tool. International Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 1 , 246–258.

von der Embse, N. P., Mata, A. D., Segool, N., & Scott, E. C. (2014). Latent profile analyses of test anxiety: A pilot study. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 32 (2), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282913504541

von der Embse, N., Jester, D., Roy, D., & Post, J. (2018). Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227 , 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.048

von der Embse, N. P., Putwain, D. W., & Francis, G. (2021). Interpretation and use of the multidimensional test anxiety scale (MTAS). School Psychology, 36 (2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000427

Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1996). Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: The S-REF model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34 (11–12), 881–888.

Wells, A. (2000). Emotional disorders and metacognition: Innovative cognitive therapy . John Wiley & Sons Ltd..

Wells, A. (2019). Breaking the cybernetic code: Understanding and treating the human metacognitive control system to enhance mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 2621.

West, A., Mattei, P., & Roberts, J. (2011). Accountability and sanctions in English schools. British Journal of Educational Studies, 59 (1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2010.529416

Wiggins, G. P. (1993). The Jossey-Bass education series. Assessing student performance: Exploring the purpose and limits of testing . Jossey-Bass.

Wimmer, L., von Stockhausen, L., & Bellingrath, S. (2019). Improving emotion regulation and mood in teacher trainees: Effectiveness of two mindfulness trainings. Brain and behavior, e01390 . https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1390

Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art . Plenum Press.

Zeidner, M., & Matthews, G. (2005). Evaluation anxiety: Current theory and research. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 141–163). Guilford Publications.

Download references

Conflicts of Interest

We have no known conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University of Texas at Tyler, Tyler, TX, USA

Christopher L. Thomas, Clara Madison Morales & Jaren Mercer

Department of Psychology and Counseling, University of Texas at Tyler, Tyler, TX, USA

Kristie Allen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christopher L. Thomas .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center for Integrated Mental Health Care (CIMHC) Federal University of Sao Paulo, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Luiz Ricardo Vieira Gonzaga

Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Letícia Lovato Dellazzana-Zanon

University of Sorocaba – UNISO, São Paulo, Brazil

Andressa Melina Becker da Silva

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Thomas, C.L., Allen, K., Morales, C.M., Mercer, J. (2022). Supporting Student Success: The Role of Test Anxiety, Emotional Intelligence, and Multifaceted Intervention. In: Gonzaga, L.R.V., Dellazzana-Zanon, L.L., Becker da Silva, A.M. (eds) Handbook of Stress and Academic Anxiety. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12737-3_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12737-3_3

Published : 11 November 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-12736-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-12737-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Seeing double at Eurovision

- Access Offers Change of Direction for Dawn

- Calls for better partnerships between youth and education sectors to enrich pupils’ lives

- NWSLC College Apprentice Shortlisted for East Midlands Business Awards

Shopping Cart

No products in the basket.

A review of the literature on anxiety for educational assessments

This review pulls together statistics and academic literature relating to the causes, symptoms and effects of assessment-related anxiety.

A review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments

PDF , 770KB , 63 pages

This file may not be suitable for users of assistive technology. Request an accessible format.

If you use assistive technology (such as a screen reader) and need aversion of this document in a more accessible format, please email [email protected] .Please tell us what format you need. It will help us if you say what assistive technology you use.

This review is part of a wider collection of material focused on managing test anxiety. It pulls together statistics and academic literature relating to the causes, symptoms and effects of assessment-related anxiety, known as test anxiety in the literature. It is an academic piece of writing that considers what is currently known about test anxiety, by drawing on existing evidence and research, and may be of particular interest to specialists and practitioners working in the field.

Published 14 February 2020

Related Articles

SPEED NETWORKING SHOWCASES STEM CAREERS AT THE MTI

Seventy school pupils from across the region have interviewed more than 30 ambassadors from automotive and engineering businesses at a speed networking event at the…

Bath Spa University awards Honorary Degrees to seven outstanding individuals

The current Turner Prize winner and esteemed Sculptor Veronica Ryan OBE was among seven Honorary Doctorates awarded by Bath Spa University at Summer Graduation ceremonies…

GOODWOOD CEO VISITS HSDC HAVANT STUDENTS

Goodwood Chief Executive Officer Chris Woodgate recently visited our Havant Campus to discuss his career journey to date with a large number of enthusiastic students.…

Oxford Business College’s Platinum Support for SMEs

Oxford Business College has been praised after becoming a Platinum sponsor, one of the first educational organisations in the UK to step forward and support…

Study Towards a Degree for Less than the Price of a Daily Meal Deal – learndirect Launches Affordable University Pathway

The UK’s leading online learning provider has launched a range of degree pathway courses for students looking for an alternative to traditional university amid the…

Students awarded prizes for achievements and making a difference

From setting up their own businesses and volunteering in the community, to excelling in their studies, supporting fellow students and making an impact with new…

Leicester College Trainer Assessor wins ‘Advanced Apprentice of the Year’ award

Katy Herrod, Trainer Assessor in Leicester College’s Taste Restaurant has won the ‘Advanced Apprentice of the Year’ award at the Leicester Apprenticeship Hub 2023 awards. …

Albert Education partnership offers green boost to film students

The University of Winchester has signed a new partnership which will boost its film students’ job prospects and make their courses more environmentally sustainable. From…

UA92 and The Moulding Foundation agree £250,000 partnership

The Moulding Foundation has agreed to support a new bursary scheme launched by Manchester education establishment, UA92 (University Academy 92), to support students from disadvantaged…

Apprentice electricians reflect on a successful first year while others look to the future in latest industry podcast from SECTT and SELECT

Apprentices from both ends of the electrical training journey have once again revealed their behind-the-scenes secrets in the second episode of the new industry podcast…

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Privacy Overview

- Browse by Year

- Browse by Organisations

A review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments

Howard, Emma , Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (OFQUAL), corp creator. (2020) A review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments. [ Research and Analysis ]

A review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments - RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS - Gov.uk

- Download HTML

- Download PDF

- Uncategorized

- Health & Fitness

- Hobbies & Interests

- Style & Fashion

- Arts & Entertainment

- Food & Drink

- Cars & Machinery

- Home & Garden

- Government & Politics

- World Around

Education for Mental Health Toolkit - Anxiety and Learning

Anxiety and learning.

The qualitative literature (1) highlights concern among some academics about what constitutes anxiety, what is a tolerable amount of anxiety or stress, what students should be able to ‘push through’ and what should be treated with concern.

Much of this discussion reflects the general difficulty in understanding mental and emotional states and confusion in language. The word ‘stress,’ for example, can be used in a variety of ways, to mean anything from mild nerves or anticipatory excitement through to high levels of anxiety and fear. This spectrum can potentially be broken up into discrete experiences in theory but, in real life situations, it is difficult to identify absolute dividing lines between what may be helpful, tolerable, intolerable and harmful.

Education for Mental Health

Download a digital copy of the full toolkit, the staff development toolkit and case studies.

In this resource we use the word ‘stretch’ for the experience of being challenged in ways that can be positive for learning, wellbeing and achievement. This experience is sometimes referred to as Eustress in the literature and has been shown to be helpful in motivating someone to engage in helpful behaviours (such as studying and academic performance) (2-4). As the students in our co-creation project highlighted, challenge can be good for wellbeing. Being challenged pushes us to grow and develop. Meeting and overcoming challenges by mastering new skills and knowledge has powerful, positive payoffs for wellbeing.

It should also be borne in mind that boredom can have a negative effect on wellbeing (5-6). A lack of challenge in our lives can lead to low motivation and a lack of meaning and purpose. The students in our co-creation group reported that when they found modules boring, they became disengaged, lost motivation and began to doubt their future, which in turn reduced their mood.

On the other side of this, high levels of stress and anxiety can reduce cognitive functioning at a neurological level. (7) (Our use of the words ‘stress’ and ‘anxiety’ in this resource reflects this experience). This reduces students’ ability to engage in complex thinking, to access old memories or make new, complex memories, to problem solve and to maintain concentration. In other words, anxiety reduces the capacity for learning and academic performance at a biological level.

Anxiety is a fear response to a perceived threat. Students become anxious about education when they view it or the environment as a threat to them (8). This fear may be stimulated by social and cultural experiences, which, for instance, leave students feeling marginalised, ostracised or humiliated. Alternatively, it may arise from a fear of failure or the perceived consequences of failure. These consequences can be emotional and practical. Students can be scared of the emotional pain they will feel if they fail. They can also fear the practical outcomes of failure, which may not be realistic e.g., they may fear that failing an assignment might lead to them having to drop out of university.

The failures some students fear can be more than the technical failure of an assignment. Some students may view a mark of 75% as a failure to achieve against their pre-conceived expectations, as articulated by our co-creation project group. Some may feel that getting an answer wrong in class is an example of failure. All of these types of failure will present risks to them – humiliation, ostracism from their peer group, etc.

The key to understanding the relationship between boredom, anxiety, stretch and learning is finding productive balance. Vygotsky’s (9) concept of scaffolded learning provides a pedagogic framework in which the aim of the curriculum should be to stretch students to their zone of proximal development – just outside their current comfort zone. This is likely to engage students in stretch, avoiding both boredom and anxiety. It may help to explain this explicitly to students and to help them recognise their strengths and successes within this framework.

When students are appropriately stretched, risk is contained and feels within the student’s control. To achieve this, when faced with a learning or assessment task, students will:

- be appropriately prepared and will understand what they have to do and how to do it.

- recognise their own skills and resources.

- have the necessary skills to undertake the task or will be able to develop them as a result of completing the task.

- have the necessary and appropriate support.

- have the resources they need – including time.

- be intrinsically motivated and focussed on the aspects of the task that are meaningful to them.

- be in an environment that feels psychologically safe.

Key lessons

- Being stretched can be good for wellbeing and learning.

- Being pushed into anxiety can reduce cognitive functioning, impacting on students’ ability to learn and perform.

- Balance is key – keep students in their proximal zone of development.

- To do this, students need to be prepared for tasks, have the necessary resources and skills, know and understand what they need to do and have the appropriate support and environment in which to learn.

- A useful guiding maxim is that if students need to know, understand or be able to do something, it must be taught to them first. If students have previous experience of a task and know how to tackle it, they will be less anxious.

- Normalising mistakes in the classroom (online or face to face) can create a learning environment that lowers anxiety and increases learning.

- Use classroom activities to identify students’ current level of knowledge and understanding, so teaching and learning activities can be calibrated to the group’s zone of proximal development.

References

Jones e, priestley m, brewster l, wilbraham sj, hughes g, spanner l. student wellbeing and assessment in higher education: the balancing act. assessment & evaluation in higher education. 2021 apr 3;46(3):438-50. available from: doi: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1782344 , gibbons c. stress, eustress and the national student survey. psychology teaching review. 2015;21(2):86-92., o’sullivan g. the relationship between hope, eustress, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction among undergraduates. social indicators research. 2011 mar 1;101(1):155-72., bourgeois, t. j. (2018). effect of eustress, flow, and test anxiety on physical therapy psychomotor practical examinations (doctoral dissertation, walden university). 2018., pekrun r, goetz t, daniels lm, stupnisky rh, perry rp. boredom in achievement settings: exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. journal of educational psychology. 2010 aug;102(3):531., pekrun r, goetz t, titz w, perry rp. academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. educational psychologist. 2002;37:91–105, marin mf, lord c, andrews j, juster rp, sindi s, arsenault-lapierre g, fiocco aj, lupien sj. chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. neurobiology of learning and memory. 2011 nov 1;96(4):583-95., howard e, a review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments. online: ofqual 2020. available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/865832/a_review_of_the_literature_concerning_anxiety_for_educational_assessment.pdf , vygotsky ls, cole m. mind in society: development of higher psychological processes. harvard university press; 1978..

©Advance HE 2020. Company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales no. 04931031 | Company limited by guarantee registered in Ireland no. 703150 | Registered charity, England and Wales 1101607 | Registered charity, Scotland SC043946 | VAT Registered number GB 152 1219 50. Registered UK Address: Advance HE, Innovation Way, York Science Park, Heslington, York, YO10 5BR, United Kingdom | Registered Ireland Address: Advance HE, First Floor, Penrose 1, Penrose Dock, Cork, T23 Kw81, Ireland.

Systematic review of student anxiety and performance during objective structured clinical examinations

Affiliations.

- 1 Texas Health Harris Methodist Fort Worth Hospital, Fort Worth, Texas, United States; Department of Medical Education, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, Texas, United States. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 University of North Texas System College of Pharmacy, Fort Worth, Texas, United States.

- PMID: 33092780

- DOI: 10.1016/j.cptl.2020.07.007

Introduction: Test anxiety is well studied in higher education, but studies primarily concern traditional assessments, such as written examinations. As use of objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) in pharmacy education increases, a closer examination of non-cognitive factors such as test anxiety is warranted. The purpose of this review was to determine the association between OSCE-associated test anxiety with OSCE performance in health professional students.

Methods: A literature search was conducted to identify peer-reviewed literature concerning test anxiety in health professional students associated with OSCE. Investigators searched for a combination of OSCE-related terms with anxiety-related terms using PubMed. Articles were included if they assessed OSCE-related anxiety by quantitative or qualitative methods. Data extracted from eligible articles included demographic data, type of the anxiety survey, associations between OSCE-related anxiety and performance, and other student-factors associated with OSCE-related anxiety.

Results: The literature search yielded 339 articles. Nine articles met eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Results included students from medical, pharmacy, dental, and nursing professional programs. Anxiety was assessed via multiple scales. Six out of the eight studies assessing the relationship OSCE-related anxiety and OSCE performance found no association between the two measures. Contrary to literature concerning test anxiety in higher education, female gender was not associated with OSCE-related anxiety.

Conclusion: OSCE-related anxiety appears to have minimal to no influence on student performance. Future studies should utilize standardized anxiety assessments and should seek to understand anxiety's effects on student wellbeing and burnout.

Keywords: Anxiety; Assessment; Clinical competence; OSCE; Objective structured clinical examination; Performance anxiety; Test anxiety.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Clinical Competence*

- Educational Measurement*

- Physical Examination

🇺🇦 make metadata, not war

A review of the literature concerning anxiety for educational assessments

- Emma Howard

- Document from Web

- NonPeerReviewed

Similar works

Digital Education Resource Archive

This paper was published in Digital Education Resource Archive .

Having an issue?

Is data on this page outdated, violates copyrights or anything else? Report the problem now and we will take corresponding actions after reviewing your request.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

The effects of work on cognitive functions: a systematic review.

- 1 Institute of Clinical Physiology, National Research Council, Pisa, Italy

- 2 Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Epidemiology and Hygiene, Italian Workers' Compensation Authority (INAIL), Rome, Italy

- 3 Occupational Medicine Unit, Foundation IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

- 4 Department of Clinical Science and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

- 5 Department of Public Health and Pediatrics, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Introduction: Cognitive functions play a crucial role in individual’s life since they represent the mental abilities necessary to perform any activity. During working life, having healthy cognitive functioning is essential for the proper performance of work, but it is especially crucial for preserving cognitive abilities and thus ensuring healthy cognitive aging after retirement. The aim of this paper was to systematically review the scientific literature related to the effects of work on cognitive functions to assess which work-related factors most adversely affect them.

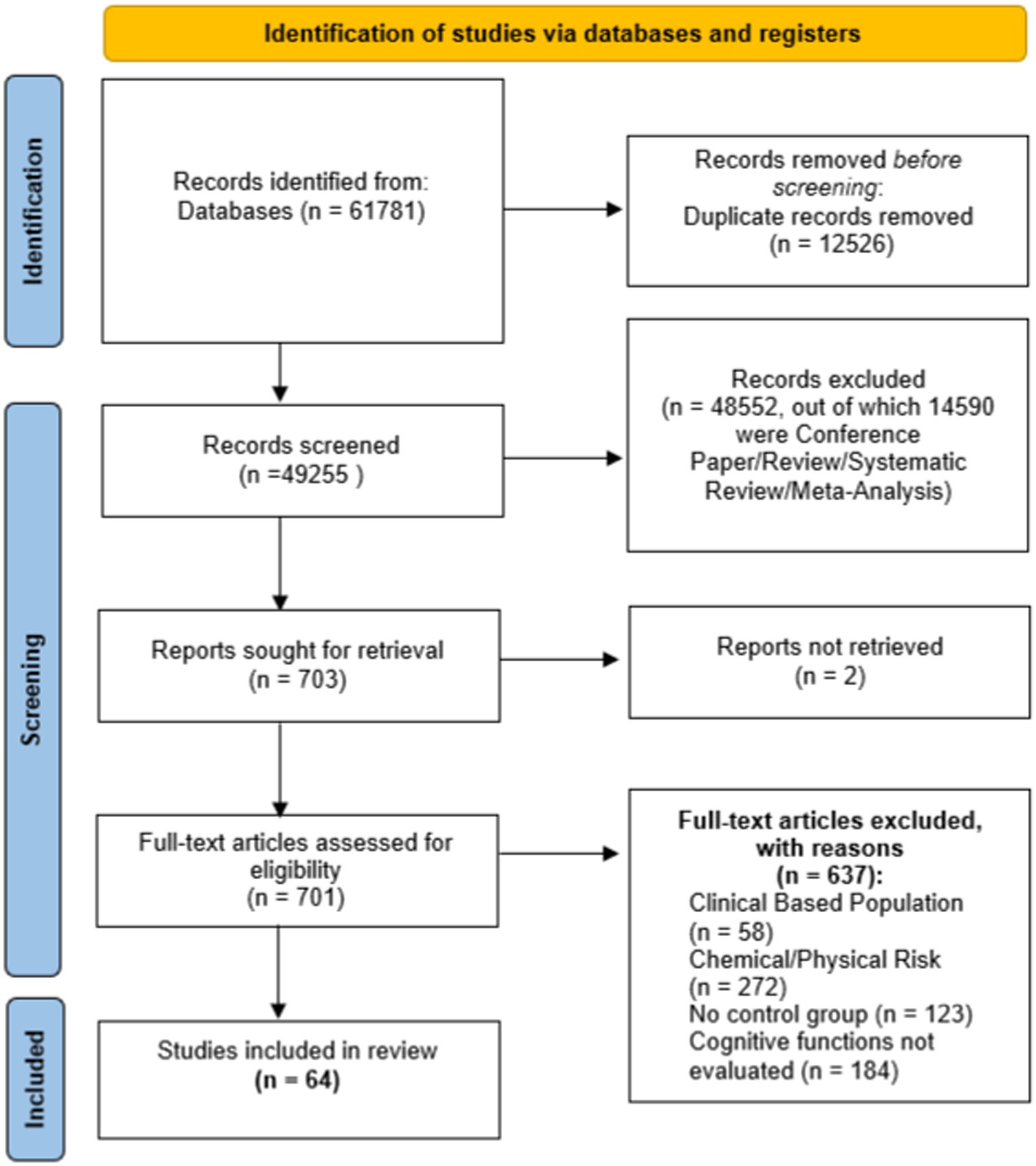

Method: We queried the PubMed and Scopus electronic databases, in February 2023, according to the PRISMA guidelines (PROSPERO ID number = CRD42023439172), and articles were included if they met all the inclusion criteria and survived a quality assessment. From an initial pool of 61,781 papers, we retained a final sample of 64 articles, which were divided into 5 categories based on work-related factors: shift work ( n = 39), sedentary work ( n = 7), occupational stress ( n = 12), prolonged working hours ( n = 3), and expertise ( n = 3).

Results: The results showed that shift work, occupational stress, and, probably, prolonged working hours have detrimental effects on cognitive functioning; instead, results related to sedentary work and expertise on cognitive functions are inconclusive and extremely miscellaneous.

Discussion: Therefore, workplace health and well-being promotion should consider reducing or rescheduling night shift, the creation of less demanding and more resourceful work environments and the use of micro-breaks to preserve workers’ cognitive functioning both before and after retirement.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023439172 , identifier CRD42023439172.

1 Introduction

Cognitive functions play a crucial role in the daily life of every human being because they represent the basic mental abilities for performing any activity. They include attention, memory and learning, perceptual motor function, executive functions, and language; each of these allows human beings to perceive the world around them and to make decisions, but also to perform from the simplest task, such as remembering a telephone number or brushing teeth, to more complex ones such as reading a book or using the internet. Among the various activities that we are able to perform with the support of cognitive functions is clearly included the execution of any kind of work. During working life, having healthy cognitive functioning is essential for the proper performance of work, but it is especially crucial for preserving cognitive abilities and thus ensuring healthy cognitive aging after retirement ( Cohen et al., 2019 ). In everyday life, there are a lot of different factors that can contribute to the preservation of adequate cognitive abilities, such as physical activity and social engagement ( Ihle et al., 2015 ), mental activities (e.g., taking courses, learning new languages) or cognitively stimulating leisure activities (e.g., go to the theatre) ( Hultsch et al., 1993 ; Schooler and Mulatu, 2001 ), and it is well known that even a high cognitive level of one’s job leads to cognitive enrichment ( Stern et al., 1995 ; Schooler et al., 1999 ), in the same way as all other variables. On the contrary, however, there are also many factors that negatively impact cognitive functions such as, for example, prolonged exposure to stress leading to the loss of neurons, particularly in the hippocampus, which is altered by the increase in glucocorticoids and results in cognitive impairment ( McEwen and Sapolsky, 1995 ), sleep problems such as insomnia can induce cognitive impairment ( Brownlow et al., 2020 ) but even acute states of sleep deprivation can trigger deterioration in one or more cognitive functions ( Wang et al., 2021 ; Bufano et al., 2023 ), and sedentary behaviour is associated with lower cognitive performance ( Falck et al., 2017 ). All these factors, both positive and negative, may be intrinsic in different types of work and may contribute to both adequate preservation of cognitive functions and cognitive impairment. Therefore, the study of how work can have an impact on cognitive function, both in a positive way and, above all, in a preventive health perspective, in a negative way, has become a priority in the field of prevention and healthy aging, as shown by the growing interest of the European community ( Salazar-Xirinachs, 2012 ; Vendramin et al., 2012 ; Belin et al., 2016 ) and latest research on the topic ( Vives et al., 2018 ; Rinsky-Halivni et al., 2022 ; Bonzini et al., 2023 ).

If we look at cognitive aging from the perspective of normative aging, there are three main theories explaining the effects of work on cognitive functions and take into account both the level of mental activity experienced during working life and the type of working environment encountered by the worker. The primary theory, which currently guides the line of research, is the “use-it-or-lose-it” hypothesis ( Hultsch et al., 1999 ; Salthouse, 2006 , 2016 ), according to which the individual level of cognitive functioning depends on two mechanisms: differential preservation and preserved differentiation. For the first one, individuals who are mentally active tends to preserve their cognitive functions more than those who are not mentally active; the second one postulates that individuals with higher levels of cognitive functioning during life retain these beneficial levels as they age. There are two other prominent theories: “the Brain or Cognitive reserve hypothesis” ( Mortimer and Graves, 1993 ; Stern, 2002 ; Fratiglioni and Wang, 2007 ) and “Schooler’s theory of environmental influences on cognitive functioning” ( Schooler, 1984 , 1990 ). The cognitive reserve hypothesis states that people who attend mentally stimulating environments will have improved neuronal development, resulting in increased cognitive reserve. This cognitive reserve could be critical in facing neuronal insults and cognitive decline, increasing individual resilience, and thus leading to healthier aging ( Mortimer and Graves, 1993 ; Stern, 2002 ; Fratiglioni and Wang, 2007 ). The Schooler’s theory holds that complex environments that promotes cognitive effort lead people to develop their intellect and apply new cognitive processes, thereby improving cognitive functioning. Conversely, if the environment do not stimulate high levels of cognitive functioning, intellectual abilities will not be maintained and there will be a decrease in cognitive functioning ( Schooler, 1984 , 1990 ). All these theoretical frameworks follow the same line: by stimulating cognitive functions in a positive way, either through mentally active jobs or enriched working environments, cognitive functions are preserved and protected, and people move toward healthier cognitive aging.

On the other hand, however, these theories remain valid and applicable as long as we talk about normative aging, since there are several factors intrinsic to various types of work that can have a negative impact on cognitive functions, causing short-term cognitive impairment and early cognitive decline after retirement. Referring to the negative factors mentioned above (i.e., sleep disturbances, stress, and sedentary behaviour), there are several studies in the literature that relate them to different types of work and show the negative effects they could have on cognitive functioning. Shift work (i.e., an employment practice designed to keep a service or production line operational at all times, even during the night) is certainly linked to sleep disturbances that can induce cognitive impairment, but also to cardiovascular diseases ( Kantermann et al., 2012 ) which can lead to the same outcome ( Picano et al., 2014 ). Highly demanding jobs that induce work-related stress (i.e., a response that people may have when exposed to job demands and pressures that do not match their knowledge and skills) may increase the risk of dementia ( Andel et al., 2012 ), and sedentary behaviour [i.e., any waking behaviour characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs), while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture ( Marconcin et al., 2021 )], caused by office work has as a potential outcome cognitive impairment ( Park et al., 2020 ), although its effects are often mixed ( Magnon et al., 2018 ).

We identified some work-related factors that can adversely affect cognitive functions and lead to cognitive impairment and probable pathological aging after retirement, but they are probably not the only ones; a comprehensive understanding of what all these factors are would be very important both from a prevention perspective and from a care perspective, with the aim of protecting their cognitive health and trying to ensure healthy cognitive aging.

Therefore, to achieve this goal and obtain a comprehensive overview of work-related factors influencing cognitive functions, our idea is to gather all the scientific literature on the topic through a systematic review using both, specific keywords related to the above-mentioned factors that negatively adverse cognitive functions, and generic keywords to try to broaden the search and discover other factors that may also exist.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 study design and search strategy.

We conducted this systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Moher et al., 2009 ; Page et al., 2021 ). PRISMA comprises a 27-item checklist to ensure and promote the quality of systematic reviews; this checklist is reported in Supplementary Tables S1 , S3 (for abstract checklist). The protocol employed in the current systematic review has been submitted for registration (ID number = CRD42023439172) to the international prospective register for systematic reviews database (PROSPERO. Available online https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023439172 ; accessed on July 06, 2023). The retrieval process consisted of three phases.

2.2 Systematic search phases

2.2.1 preliminary research and definition of keywords.

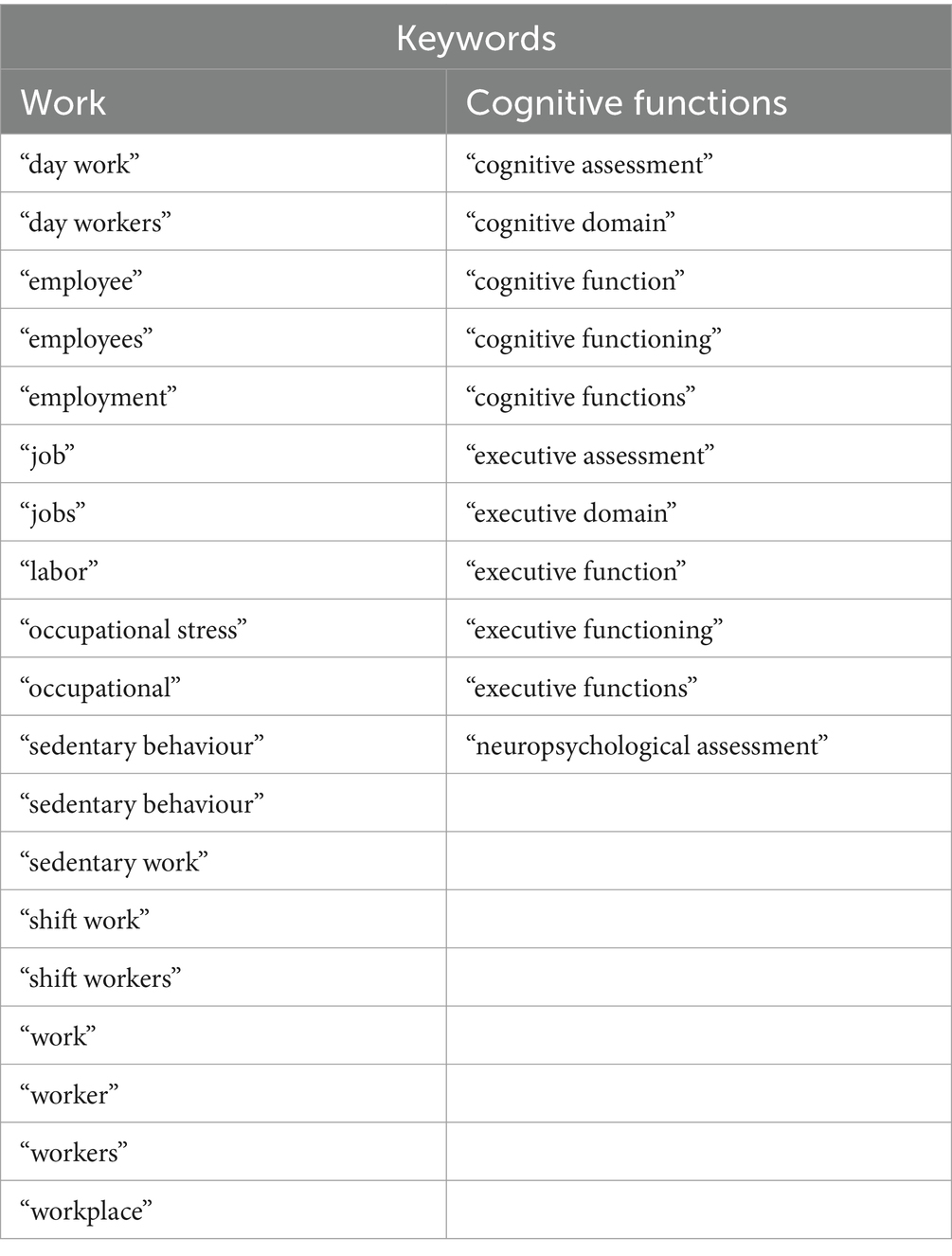

During the first phase, started in February 2023, we carried out preliminary research in absence of specific keywords based on the review of Fisher et al. (2017) , to define search criteria and identify the specific keywords to be used. Before defining the final list of keywords, we started from a very large list that, when entered into search engines, produced a massive number of results. We therefore removed nonspecific keywords and, on the fourth attempt, based on our research question, defined specific keywords (see Table 1 ) related to two domains: “Work” and “Cognitive Functions,” for inclusion in search engines to conduct the systematic research.

Table 1 . List of selected keywords.

2.2.2 Systematic search and definition of PICOS

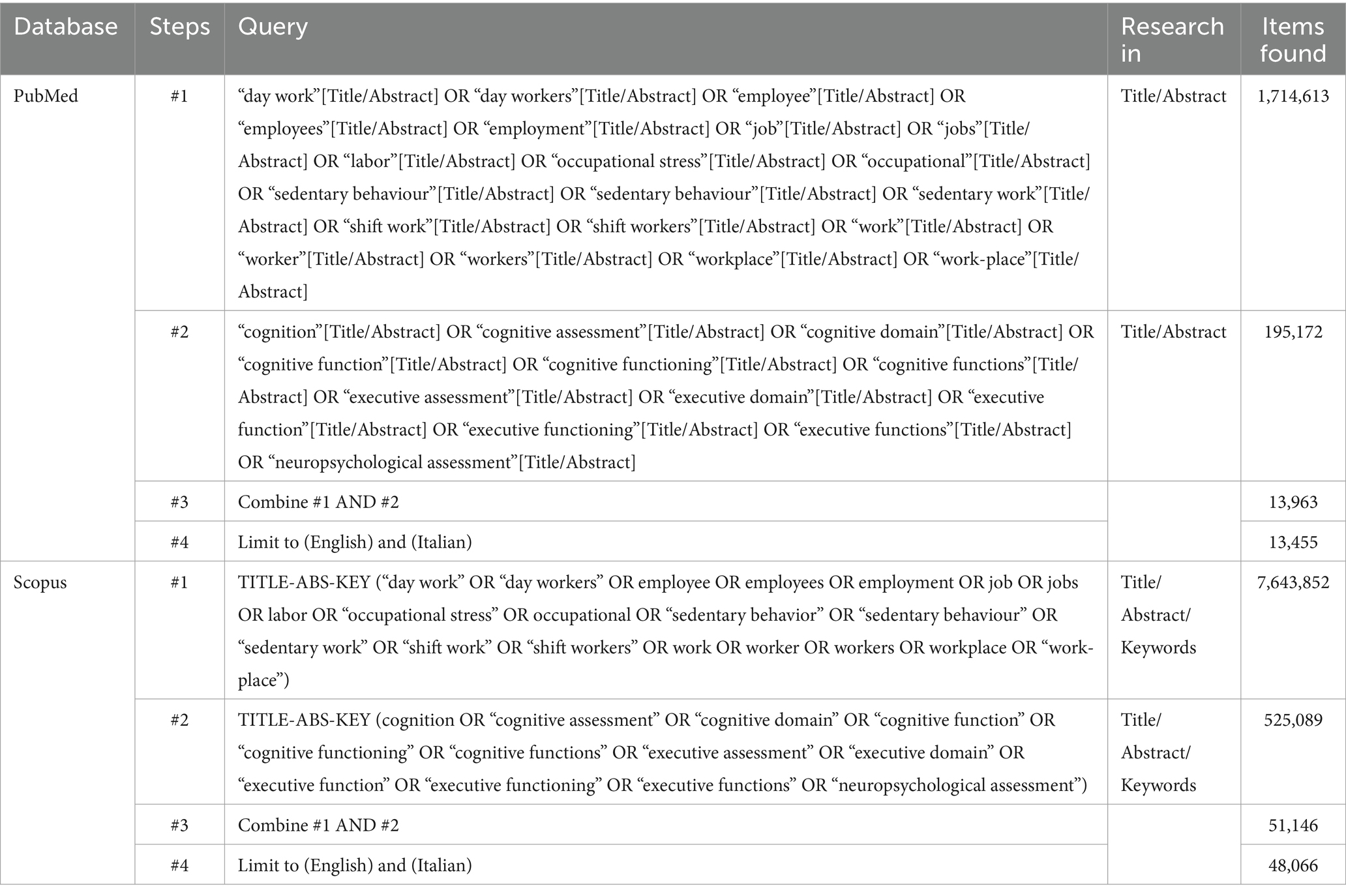

The second phase, conducted in February 2023, consisted of a systematic search among titles, abstracts, and keywords of scientific papers, using the electronic databases PubMed and Scopus, based on the selected keywords, properly combined through the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”; no temporal restriction was set, so all articles published up to February 2023 in Italian and English were included in the systematic search. The search strategy, including all keywords used and the number of studies found from each database, was analytically reported in Table 2 .

Table 2 . Search strategy.

The final selection of papers for inclusion was carried out according to the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design (PICOS) worksheet ( Moher et al., 2009 ; Page et al., 2021 ), summarised in Table 3 . We defined the following PICOS criteria: Population, we chose “Healthy Workers (or not diagnosed)” as the inclusion criteria and “Clinical based population” as exclusion criteria because we aimed to avoid including populations in which, an organic disease or mental disorder could affect cognitive functions by generating a bias in the assessment; Interventions, we chose as inclusion criteria “Assessment of cognitive function without chemical/ or neurotoxic, or physical hazard exposure” to avoid including jobs where the worker’s exposure to various substances could create a bias in the assessment of cognitive function; Comparisons, we chose as inclusion criteria “Control Group (Between or Within design)” in order to have a comparison between two populations working different jobs (e.g., shift work vs. non-shift work), or between the same population during different shifts (night shift work vs. day shift work), in order to see if there was a variation in cognitive functioning due to the factor the study was investigating; Outcomes, we chose as inclusion criteria “Change or non-change of cognitive function according to different conditions,” to have a real evaluation of cognitive functioning through the use of cognitive test, thus studies with a quantitative measure of cognitive functioning; Study Design, we chose “Review, Scoping Review, Narrative Review, Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, Editorial, Book, Case Report, Conference Review, and Conference Paper” as exclusion criteria following the guidelines to carry out a Systematic Review.

Table 3 . Population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study design (PICOS) worksheet.

2.2.3 Application of PICOS study design exclusion criteria

The final phase consisted of a first step in which, following PICOS criteria related to the Study Design section, we excluded all reviews, both narrative and systematic ones, meta-analyses, and conference papers, to substantially reduce the number of included studies.

2.2.4 Title and abstract selection

By reading the titles and abstract we excluded all studies that did not match with the research question.

2.2.5 Full-text selection according to PICOS criteria

Finally, we included in the systematic review only clinical or epidemiological studies that investigated the effects of work on cognitive functions in groups of workers. The included papers were read thoroughly to obtain the data of our interest.

2.2.6 Synthesis method

The included papers were clustered according to the work-related factors that may affect cognitive functions and then, for each study, we extracted all the information shown in Tables 4 – 8 as described next:

Table 4 . Shift work and cognitive function: retrieved studies and their main outcomes.

Table 5 . Sedentary work and cognitive function: retrieved studies and their main outcomes.

Table 6 . Occupational stress and cognitive function: retrieved studies and their main outcomes.

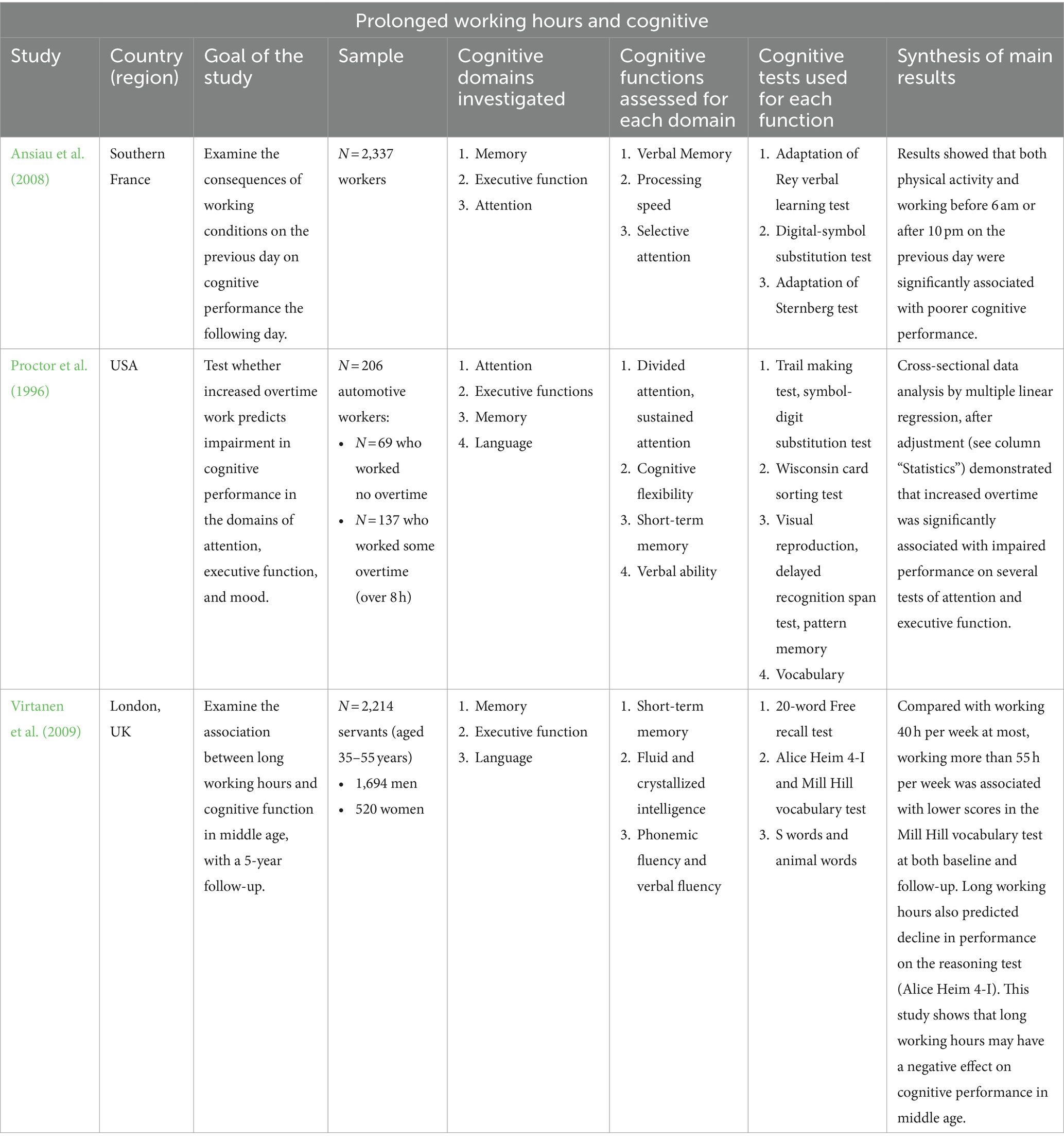

Table 7 . Prolonged working hours and cognitive function: retrieved studies and their main outcomes.

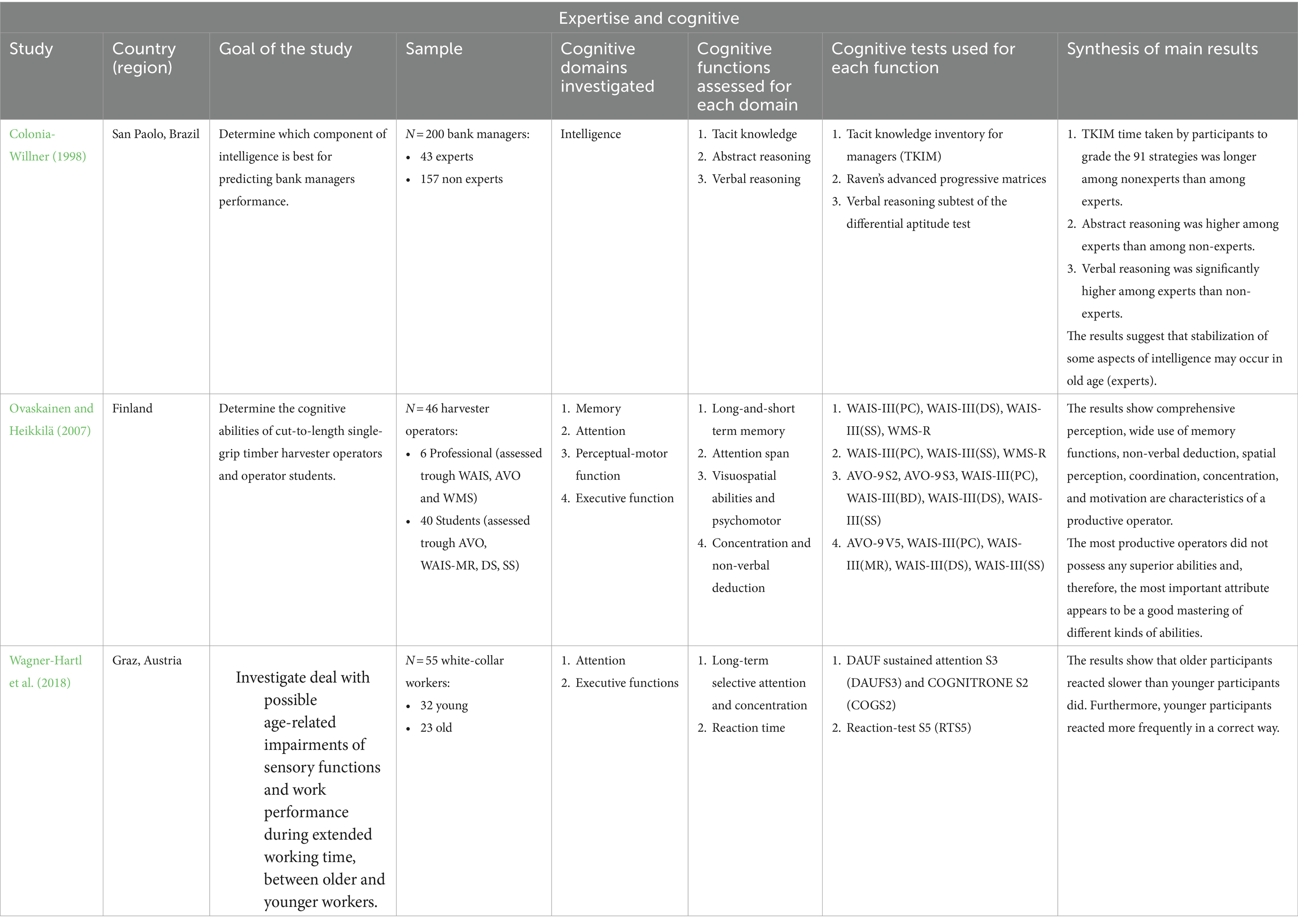

Table 8 . Expertise and cognitive function: retrieved studies and their main outcomes.

Study = name of authors, year; Country (Region) = where the study took place; Goal of study = Objective of the study; Sample = sample size; Cognitive domains investigated = which cognitive domain were investigated; Cognitive functions assessed for each domain = which cognitive functions were investigated for each domain; Cognitive tests used for each function = which cognitive test were used to evaluate each cognitive function; Synthesis of main results = narrative summary of results.

2.2.7 Study risk of bias assessment

We assessed the risk of bias for each study in Supplementary Table S2 by compiling the AXIS tool ( Downes et al., 2016 ).

3.1 Flow diagram

Figure 1 shows all the phases in the systematic review process. The research carried out on PubMed and Scopus yielded 13,455 and 48,066 studies, respectively. These 61,781 papers were merged in a non-redundant database and 49,255 papers remained. Then, by eliminating all studies not related to our research question and all studies that did not match PICOS criteria related to Study Design (exclusion for all types of reviews, meta-analysis, and conference papers), the number of studies was reduced to 703, of which 2 were not retrieved. Finally, by applying all the PICOS criteria, we obtained 64 studies to be included in the systematic review.

Figure 1 . Flow diagram.

3.2 Study selection and characteristics

Two independent reviewers (P.B. and M.L.) checked the pool of 49,255 abstracts collected from PubMed and Scopus search engine outputs; any disagreement was discussed with M.B. as the arbiter. Titles and abstracts were screened, and 48,550 were removed through a semi-automatic script created via MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, United States), according to PICOS criteria related to Study Design (14,590 papers) and irrelevance to the research question (34,258 papers). The remaining 703 papers were checked for eligibility according to the remaining PICOS criteria, all clinical based population studies (58), all studies regarding chemical/physical risk (272), all studies with no control group (123) and lastly, all studies without a quantitative evaluation of cognitive functions (184) were excluded, 2 papers were not retrieved even after explicit request to the corresponding authors. Finally, 64 articles were included, summarized in Tables 4 – 8 , which shows the main information of each, divided according to work-related factors that may affect cognitive functions.

3.3 Synthesized findings

In this subsection, for each study, we reported the main findings of pertinence for this systematic review grouped according to work-related factors that may affect cognitive functions.

3.3.1 Shift work and cognitive functions

Among 64 studies included in the systematic review, 39 were related to the effect of shift work on cognitive functions ( Table 4 ) ( Deary and Tait, 1987 ; Orton and Gruzelier, 1989 ; Lingenfelser et al., 1994 ; Smith et al., 1995 ; Petru et al., 2005 ; Rouch et al., 2005 ; Saricaoğlu et al., 2005 ; Griffiths et al., 2006 ; Chang et al., 2011 , 2013a , b ; Anderson et al., 2012 ; Shwetha and Sudhakar, 2012 , 2014 ; Niu et al., 2013 ; Özdemir et al., 2013 ; Veddeng et al., 2014 ; Kazemi et al., 2016 , 2018 ; Maltese et al., 2016 ; Titova et al., 2016 ; Vajravelu et al., 2016 ; Haidarimoghadam et al., 2017 ; Soares and de Almondes, 2017 ; Williams et al., 2017 ; Persico et al., 2018 ; Taylor et al., 2019 ; Abdelhamid et al., 2020 ; Adams and Venter, 2020 ; Athar et al., 2020 ; James et al., 2021 ; Prasad et al., 2021 ; Stout et al., 2021 ; Sun et al., 2021 ; Zhao et al., 2021 ; An et al., 2022 ; Benítez-Provedo et al., 2022 ; Esmaily et al., 2022 ; Peng et al., 2022 ).