- Accreditation

- Value of Accreditation

- Standards and Process

- Search Accredited Schools

- Educational Membership

- Business Membership

- Find a Member

- Learning and Events

- Conferences

- Webinars and Online Courses

- All Insights

- B-School Leadership

- Future of Work

- Societal Impact

- Leadership and Governance

- Media Center

- Accredited School Search

- Advertise, Sponsor, Exhibit

- Tips and Advice

- Is Business School Right for Me?

Are Education and Training Perfect Partners?

- As we move deeper into the Fourth Industrial Age, it is increasingly critical that we understand the interconnections between education and training.

- We must challenge assumptions that training is suitable primarily for manual workers and education is reserved for professionals—instead, we must imagine a future in which everyone pursues both.

- To be prepared for the future of work, employees will require a combination of immersive training and disciplined education encompassing a wide range of learning experiences.

As young people step from full-time school or higher education into their professional careers, they might assume that they have completed their formal educations. They might anticipate that, if they are fortunate, they will participate in occasional additional training during their careers.

When we think of training, we often think of learning opportunities provided by large corporations to help their employees increase productivity, implement new technology, adopt best practices important to the firm’s management, and advance through the company hierarchy.

Small and medium-sized organizations, which often lack the resources to provide training in-house, may train employees by enrolling them in courses or bringing in world-renowned leaders in their fields. By seeking out premium resources, companies enable their staff members to shape bespoke training journeys for themselves.

By contrast, when we think of education, we think of adults—whether as individuals or with the support of their companies—attending school to pursue broader-based knowledge. This pursuit is often in the form of a degree program.

People so widely share the view that “education” is classroom- and theory-based, while “training” is skills- or practice-based, it has become a truism. Conventional wisdom marks the following contrasts between education and training:

| Pursuit of ability | Pursuit of knowledge |

| Improves performance and productivity | Improves reasoning and judgment |

| Emphasizes skills development | Emphasizes knowledge development |

| Concerned with practical applications | Concerned with theoretical foundations |

| Task-focused | Concept-focused |

| Narrow | Wide |

Yet even if we still generally accept these definitions, the idea of making clear distinctions between education and training as “practice versus theory” is already under strain.

For example, consider common subjects for formal training events such as diversity, unconscious bias, assertiveness, collaboration, and leadership. No instructor can tackle these topics without first teaching the background, principles, and sociopolitical meaning behind them.

In these cases, participants must receive a foundation of education to support any practical training. The same is true in the opposite direction: Education alone will not take a person far in the real world. Or, as author and consultant Ian MacRae puts it in a 2017 article , “It is possible to teach someone about buoyancy, fluid dynamics, water displacement and coastline safety, but that knowledge will not make them a good swimmer.”

If an element of education underpins all training programs and if practical experience is a vital element of education, is there still value in maintaining an entrenched understanding of their differences? I believe there is, if only so we better understand how to deploy both in ways that they reinforce each another.

Training as a ‘Promise to the Community’

People who are privileged to begin their lives with a modern, liberal education—encompassing primary, secondary, and especially higher education—often receive many advantages over their lifetimes. They enjoy a boost to their incomes, health, life expectancies, and life satisfaction, compared to those who grow up in less privileged circumstances. These benefits were shown in a 1999 study by Stacy Berg Dale and Alan Krueger.

Such relative gains are particularly linked to institution-based, conceptual education. They do not relate to training, whether in skills or in awareness of issues relevant to the workplace.

Some might find it distasteful to view education as an investment with a tangible return. Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that a broad education encompassing the humanities, sciences, and liberal arts creates a more “rounded” student. This view is undoubtedly subjective, and yet it’s one that many people share.

By contrast, training is commonly defined as applied knowledge for a particular occupation, and it has immense value for both employers and employees. Also described as human resource development (HRD) or continuing professional development (CPD), training provides a language and conceptual framework for people to advance in their careers. HRD and CPD also enable companies to invest simultaneously in upskilling their workforces and improving productivity.

As Becht, a multinational engineering corporation, explains in a 2019 blog post , “Training is a promise to the employees and the community that your company is doing all that it can to stay safe, up to date, and prepared for any situations that may arise.”

Education Is Not Just for Elites

From a historical perspective, the ideas surrounding training and education represent two different socioeconomic expectations of young people and their prospects. As Thomas N. Garavan explains in a 1997 paper , for centuries, classics-based education was reserved for the ruling elites, while training was a preserve of skilled craftsmen. Most agricultural laborers enjoyed neither schooling nor training.

Before the Industrial Revolution, Garavan writes, “training was essentially designed to equip the apprentice with skills which would be used throughout his/her career. Master status, within the context of the trade guilds in England and Ireland, implied that the craftsperson had acquired the full complement of skills and knowledge for the independent execution of his/her craft.” He continues, saying, “It was assumed that the demands of the job would not alter significantly during the working life to warrant other forms of training.”

As the Industrial Revolution gathered momentum, primary education became more widespread in advanced economies. In the United States and Europe, primary education became compulsory toward the end of the 19th century —England passed its Education Act in 1880, and all U.S. states had made primary education for children ages five to 14 compulsory by 1930. Based on emerging notions of children’s educational needs, the curriculum included arithmetic, reading, and writing.

We can challenge the assumption that training is relevant only for those seeking on-the-job skills and that education is suitable only for the privileged elite.

But once children reached secondary school age, the curriculum for working class children diverged sharply from that for the elite: Private schools taught the classics and philosophy, while church and government schools trained children to enter vocations.

During the mid-20th century, schools increasingly began to resemble factories, with bells ringing in the start and end of each day (shift?) and desks positioned in neat, orderly rows. Students learned to follow directions without questioning either the content or the authority of their teachers.

Although schools have transformed significantly since the days when children were expected to help in the fields during the long summer holiday, it’s easy to wonder whether a whole new approach to education might be overdue. Perhaps as the Fourth Industrial Revolution takes hold, we can challenge the assumption that training is relevant only for those seeking practical, on-the-job skills and that education is suitable only for the gifted or privileged elite .

Rather than dividing the next generation into cadres of manual workers or professionals, could we imagine a future in which everyone benefits from both training and education?

Adaptation Through Apprenticeships

In a 2008 paper , Alan Blinder, economist and former vice-chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, argues that education at both primary and secondary levels needs to adapt to the changing expectations and ambitions of young people. Blinder suggests that, at a time when many service and manufacturing jobs are being off-shored to countries where labor is less costly, young people should pursue careers that must be done in person, such as those in medicine, teaching, social work, plumbing, and even flower arranging.

“The new curriculum for the Information Age must emphasize attributes and skills in which we humans hold comparative advantages over machines,” Blinder explains. “To me, that suggests a style of teaching and a curriculum that features (in addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic) communication and interpersonal skills, group interactions, puzzle solving, learning by doing, experimentation, and perhaps even epistemic video games.”

In professional environments where technology is constantly changing, no workers will utilize only one set of skills throughout their careers. In this case, how can we adapt our understanding of education and training? Traditional distinctions that view education as theoretical and training as vocational no longer reflect the lived experience of the workforce.

One noteworthy example of the way education and training are coalescing is the Degree Apprenticeship program. In partnership with companies, business schools in the U.K. offer a wide variety of apprenticeships in which students study for business degrees while they work full time. This program enables young people who might not think of themselves as typical business school candidates to graduate with business or management degrees without spending years in full-time higher education.

Companies offering degree-based apprenticeships include household names such as Tesco, Aldi, Boots, and Unilever. These degree apprenticeships have rapidly expanded since the scheme was launched in 2015. They now are running at City University, Manchester Metropolitan University, Loughborough University, University of Exeter, Liverpool John Moores, and many other institutions.

Degree apprenticeships go beyond the dichotomy between learning and training to enable students to learn through experience as they work in real-world environments.

Similar models also can be found elsewhere in the world : Australia maintains a website that directs students to school-based apprenticeship opportunities, and there are some programs in the U.S. with more limited reach.

Degree apprenticeships go beyond the dichotomy between learning and training. They enable students to learn through experience as they work in real-world environments with inspirational colleagues in professional and academic settings. Though not suitable for everyone, such collaborations between industry and institutions will surely develop and strengthen in the coming decades.

Is All Career Preparation ‘Training’?

Long before degree apprenticeships emerged, educational philosopher Richard Stanley Peters defined education and training differently , in what was then considered a radical new way. He argued in 1972, as well as with co-authors in 1975 , that training could be as theoretical and intellectual as education, and that traditional schooling could no longer be fundamentally separated from lifelong skills development.

Peters sensed that, in the future, preparation for all types of work would require intense training, not only for simple tasks, but also for high-level cognitive activity. In Peters’ view, both education and training require people to dedicate themselves to learning, whether for a tangible purpose or purely for academic attainment.

This delicate shift was summarized in 1995 by educator Peter Mckenzie, who defended the idea that education and training are still different, despite society’s fundamental transformation to an information economy. Mckenzie reinforces Peters’ view that, when the focus is on preparing people to become “competent practitioners” in any context, “we may, by virtue of the directionality and focused nature of the enterprise, reasonably talk about ‘training.’”

Training Will Be a Constant Presence

Without engaging with new ideas, technologies, and practices throughout our lives, we will miss out on an extraordinary wealth of opportunities, experiences, and challenges. That’s why training should and will be a constant presence in young people’s lives, as they explore industries that do not exist today and could not have been imagined in previous generations.

Traditional education is critical for developing an open mind, skepticism of present endeavors, and awe of past achievements. But learning to grow and create the novel rainbow of skills that will shape our future society will require us to take a different approach to learning. We must combine immersive training with disciplined education, in ways that ensure people experience every different shade of learning experiences across this vast spectrum.

- Learning Delivery

- Lifelong Learning

- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Training and Education

These two are so closely intertwined that with the passage of time the difference between training and education is getting increasingly blurred. Nevertheless, these two terms are different in their nature and orientation. The worker, who takes training, in the organization, is said to have had some education and thus, there is no training, without education.

Content: Training Vs Education

Comparison chart.

| Basis for Comparison | Training | Education |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | The process of inculcating specific skills in a person is training. | Theoretical learning in the classroom or any institution is education. |

| What is it? | It is a method of skill development. | It is a typical form of learning. |

| Based on | Practical application | Theoretical orientation |

| Perspective | Narrow | Wide |

| Involves | Job experience | Classroom learning |

| Term | Short term | Comparatively long term |

| Prepares for | Present job | Future job |

| Objective | To improve performance and productivity. | To develop a sense of reasoning and judgement. |

| Teaches | Specific task | General concepts |

Definition of Training

Training is nothing but learning by doing. It is a well-planned program aimed at developing specific skills and knowledge of the manpower. It is a common concept of human resource development where an attempt is made to improve the performance, productivity and competency of the existing and potential employees through learning. The program is specially designed by the organisation to achieve definite goals.

Training helps in imparting job-related skills in the employees so that they can do the job efficiently and effectively. Training can be on-the-job or off-the-job, paid or unpaid, part time or full time, depending on the contract with the employer. At the end of the program, the employees are tested by observing, what they learned during training. Some common types of training are:

- Sensitivity training

- Vestibule training

- Job rotation

- Laboratory training

- Apprenticeship training

- Internship training

- Orientation training

Definition of Education

By the term education, we mean learning in the classroom to acquire certain knowledge. Education does not equal to schooling, but it refers to what a person gains while he is in school or college. It is aimed to deliver knowledge about facts, events, values, beliefs, general concepts, principles, etc. to the students. This helps in developing a sense of reasoning, understanding, judgement and intellect in an individual.

The lessons learned during the process of education helps a person to face future challenges, and it prepares a person for future jobs. Nowadays, education is not confined to classroom learning, but new methods are implemented that offers practical knowledge about the world.

There are various phases of education like kindergarten, primary, high school, higher secondary, undergraduate, post graduate etc. Certificates or degrees are awarded to the students when they clear a particular level of education.

Key Differences Between Training and Education

The significant differences between training and education are mentioned in the following points:

- Training refers to an act of inculcating specific skills in a person. Education is all about gaining theoretical knowledge in the classroom or any institution.

- Training is a way to develop specific skills, whereas education is a typical system of learning.

- Training is completely based on practical application, which is just opposite in the case of education that involves theoretical orientation.

- The concept of training is narrow while the concept of education is comparatively wider.

- Training involves hands-on experience regarding the particular job. On the other hand, education involves learning in the classroom.

- The term of education is longer than the duration of training.

- The training prepares a person for the present job. Conversely, education prepares a person for future job and challenges.

- The purpose of training is to improve the performance and productivity of employees. As opposed to education, where the purpose is to develop a sense of reasoning and judgement.

- During training, a person learns, how to do a specific task. Unlike Education, which teaches about the general concepts.

Though with the changing environment, the approach towards training and education is also getting changed. Normally, it is presumed that every employee who is going to take training, has got some formal education. Moreover, it is also true that there is no training program which is conducted without education.

Education is more important for the employees working on a higher level as compared to the low-level workers. Although education is common for all the employees, regardless of their grades. So, the firms should consider both the elements, at the time of planning their training program because there are instances when the employees need to take decisions themselves regarding their work, where education is as important as training.

You Might Also Like:

Muhammad Hussain says

September 1, 2016 at 8:40 pm

Good research done on the subject of education management and training.

Chetan Singh says

October 22, 2017 at 7:53 pm

Thanks for post. It is simple and useful.

August 7, 2018 at 11:06 pm

A clear and distinct difference!

soumya says

November 15, 2018 at 10:46 am

well explained in simple language

Emmanuel Abah says

January 22, 2019 at 8:08 pm

siyanda says

February 23, 2019 at 3:10 pm

a well encapsulated features thank you

March 31, 2019 at 4:29 pm

Akeju, Wemimo Peace says

June 25, 2019 at 1:48 pm

Well explained.

Marlene Butters says

August 17, 2019 at 1:04 pm

Every weekend I used to visit this web site, as I wish for enjoyment since these site conations actually pleasant funny information too.

Mubo Obajana says

October 13, 2019 at 10:09 pm

thank you very much

William says

January 31, 2020 at 9:07 pm

Very informative.

chinonso says

March 8, 2020 at 8:57 pm

good day the post was really useful for my work but how can I cite it as a reference

shima.h says

October 12, 2020 at 1:42 pm

it is very useful. thank you

January 3, 2021 at 11:17 pm

Thank you very much I gain some thing

Sumita Mukherjee says

September 11, 2021 at 11:54 am

Yes indeed in simple terms education is something which we learn theoretically and training is when we do it practically. I learned a few new concepts from this post. Thank you for sharing.

Parinitha Bhargav says

February 24, 2022 at 10:23 pm

The difference between training and education comparison table explains it so well. Thank you for the helpful explanation.

March 11, 2022 at 6:15 pm

thank you so much really great post.

cygnux says

March 17, 2022 at 2:14 pm

nice great post Thank you for this post

Catherine colloge says

March 20, 2022 at 9:55 pm

you describe the great difference between education and training. Thanks for sharing such amazing information.

coepd BA says

March 24, 2022 at 5:34 pm

Great info keep sharing info

April 18, 2022 at 10:32 pm

Great article! I had a good time browsing your website. I don’t leave very often remarks, but you deservingly get a thumbs up! Keep Posting

sarah okwoma says

April 23, 2022 at 2:46 pm

Great article the difference well elaborated no confusion

tayyab says

May 24, 2022 at 4:50 pm

Thanks, for information

July 22, 2022 at 2:59 am

It’s a nice article, it helps me a lot.

digiworldmag says

August 24, 2022 at 5:53 pm

Informative post! This is a great share thank you.

Lucy martin says

September 12, 2022 at 1:11 pm

Very informative blog. Simple, effective, and useful too. Continue to enlighten us with your knowledge. Thanks for sharing…

Dharmendra Kushwah says

September 23, 2022 at 4:42 pm

Informative blog thanks for sharing this valuable content.

September 27, 2022 at 4:10 pm

Your blog post is just amazing, please keep posting this kind of blog..!!

deteced says

October 1, 2022 at 1:19 am

Great content, it will help in my business Thank you for sharing useful information. Respectfully, David from https://deteced.com/

srislaw says

November 7, 2022 at 10:38 pm

Interesting article. I enjoyed reading it. Thanks for sharing it.

babar cheema says

December 13, 2022 at 9:48 am

Thanks for your information. I read your article. I am very impressed

Surendra says

December 15, 2022 at 12:40 pm

Thanks for sharing the useful information. Really informative post and very helpful. I wish you good luck with your future blogs.

Jayson Musk says

December 27, 2022 at 7:27 pm

Great content; thanks for your information. I read your article and am very impressed and i agree that there is greats difference between education and learning.

olliescharles says

February 6, 2023 at 12:54 pm

Nice article. Thanks for sharing the informative post keep posting

February 20, 2023 at 11:07 am

Thank you for creating such an interesting blog with clear details.

sarthak says

February 22, 2023 at 12:05 pm

I had this confusion; thanks for clearing

February 22, 2023 at 12:06 pm

Thanks for helping me out of the confusion between the two

April 11, 2023 at 1:31 pm

thanks for writing a nice article

Charlotte Mason says

May 31, 2023 at 4:10 am

Thanks for sharing this informative information.

June 1, 2023 at 3:12 pm

Vanshika says

July 1, 2023 at 1:48 pm

Thank you for sharing such valuable insights.

July 23, 2023 at 2:01 pm

Thankyou for sharing the data which is beneficial for me and others likewise to see.

Rechtsanwalt says

July 24, 2023 at 6:26 pm

Excellent work.

July 25, 2023 at 5:19 pm

You’ve completed in excellent work.

suchi sharma says

October 9, 2023 at 11:11 pm

“This blog provides a clear and insightful breakdown of the distinctions between training and education.

Thank you for such an amazing blog.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Apr 7, 2021

Working to Learn: New Research on Connecting Education and Career

New White Paper from the Project on Workforce Highlights Critical Need to Better Connect Education and Career

By: Joseph B. Fuller, Rachel Lipson, Jorge Encinas, Tessa Forshaw, Alexis Gable, & J.B. Schramm

Download the report:

In the wake of covid-19 and growing inequality, america needs more pathways that bridge education and career. new research from the project on workforce at harvard draws on data from new profit's postsecondary initiative for equity to identify opportunities for the education-to-employment field and chart the course for connections to good jobs., press release.

APRIL 7, 2021 -- A new white paper released today by Harvard’s interdisciplinary Project on Workforce - Working to Learn: Despite a growing set of innovators, America struggles to connect education and career - highlights stark challenges and transformative opportunities for the growing field of organizations seeking to connect postsecondary education with employment.

The development of job pathways that integrate work and learning are critical to an equitable recovery and a future where social and economic opportunity are available to all. Workers from underrepresented communities, particularly communities of color, have been most affected by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and traditionally have faced the largest systemic barriers to social and economic opportunity in America. These communities are wellsprings of insight and talent where people are poised to take advantage of stronger pathways to learning and earning amidst accelerating changes in our workforce and economy.

“Our research showed that many organizations purporting to connect both education and career are still struggling to do so,” said Joseph Fuller , Professor of Management Practice at the Harvard Business School and co-author of the report. “While standout organizations exist in the field, too few programs are linking soft and hard skills, prioritizing evidence, working with employers, or providing wraparound supports.”

The research utilized a unique dataset of 316 applications to an open grant competition for programs seeking to connect postsecondary education and employment. Analyzing these organizations, the report’s authors found:

Huge potential to engage employers more deeply: Programs that worked with employers were growing faster than peers, but only about one-third (35 percent) of organizations mentioned that they were working directly with employers. Only about one-quarter mentioned providing learning opportunities in workplace environments.

Opportunities to build bridges between education and employment: Only 16 percent of organizations prioritize relationships with both educational institutions and employers. Success measurement is similarly siloed between education and employment metrics; for organizations that focused on college-related outcomes, only 33 percent also prioritized employment outcomes.

A growing need to develop transferable skills in the future of work : One-third of organizations in the dataset focused on job-specific training, but just nine percent of organizations prioritized foundational soft skills alongside job-specific skills.

A critical opportunity for more investment in wraparound supports: Only 13 percent of organizations cited directly providing wraparound supports like subsidies for transportation, housing, or childcare.

A growing, but still nascent, evidence base: The most common success metric tracked by applicant organizations (59 percent) was whether participants completed the program. About one-quarter of organizations indicated that they measured employment rates and a similar share tracked college attendance. Causal evidence is more rare; nine percent of applicants cited an existing study, quasi-study, or external evaluation of the program model in their application.

Under-leveraging of technology in some areas : Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the field was heavily skewed towards in-person models. Only six percent of programs were fully online; 11 percent had hybrid models.

“To date, the field is fragmented and often siloed between college and employment missions,” said report co-author Rachel Lipson , Project Director of the Project on Workforce at the Harvard Kennedy School. “But there is vast untapped potential to scale innovations both within and across organizations.”

Postsecondary Innovation for Equity initiative

The data for this research comes from the Postsecondary Innovation for Equity (PIE) initiative . The PIE initiative was developed by New Profit, a nonprofit venture philanthropy that supports social entrepreneurs who advance equity and opportunity in the United States. New Profit asked organizations that considered themselves innovators in the education-to-employment sector to apply to receive an unrestricted $100,000 grant and participate in a peer learning community. Of the 316 applications received, New Profit selected 20 organizations for the first round of grants and support. The full data set from the 316 applicants provided rich material for this analysis of the current state of the education-and-employment field.

Advancing the education-and-employment field

The PIE initiative supports innovators working at the intersection of education and employment to develop new approaches to connect young adults from low-income and underrepresented communities with the postsecondary credentials and work experience needed to access upwardly mobile careers. For example, CodePath.org is leveraging technology to help thousands of college students from underrepresented backgrounds gain the skills and connections they need to launch tech careers; Generation USA is forging close partnerships with employers to rapidly train and place adult learners into upwardly mobile jobs; and the Brooklyn STEAM Center is closing the gap between school and work by enabling New York City public high school students to learn through work experience at dozens of companies located at the former Brooklyn Navy Yard site.

“Scaling and disseminating successful models will be key to systemic change,” notes New Profit Associate Partner Glendean Hamilton , co-leader of the PIE initiative. “ Working to Learn points philanthropists and policymakers toward the kind of innovation needed to build a more equitable education-to-employment system in America.”

A virtual report briefing and discussion will be held on April 28, 2021 at 11:00am EDT and open to the public. Please register for the briefing at this link .

For media inquiries:

Nikhil Gehani, [email protected]

Rachel Lipson, [email protected]

About the Project on Workforce at Harvard

The Project on Workforce is an interdisciplinary, collaborative project between the Harvard Kennedy School's Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, the Harvard Business School Managing the Future of Work Project, and the Harvard Graduate School of Education. The Project produces and catalyzes basic and applied research at the intersection of education and labor markets for leaders in business, education, and policy. The Project’s research aims to help shape a postsecondary system of the future that creates more and better pathways to economic mobility and forges smoother transitions between education and careers. Learn more at www.pw.hks.harvard.edu .

About New Profit

New Profit is a nonprofit venture philanthropy organization that backs breakthrough social entrepreneurs who are advancing equity and opportunity in America. New Profit’s strategy focuses on building a breakthrough portfolio of grantee-partners to take on entrenched systemic challenges in America, including by driving resources and support to Black, Indigenous, and Latino/a/x social entrepreneurs who have unique proximity to solutions, but face stark racial funding disparities in philanthropy; and investing in social entrepreneurs with new systems change models across a range of issues. Learn more at www.newprofit.org .

Funding for the Postsecondary Innovation for Equity (PIE) initiative at New Profit is provided by Lumina Foundation, Siegel Family Endowment, Walmart, Walton Family Foundation, and an anonymous investor.

- EDUCATION & SKILLS

Related Posts

The Workforce Almanac Report: A System-Level View of U.S. Workforce Training Providers

The Workforce Almanac Data Portal: Mapping the workforce development sector

Building the U.S. Construction Workforce

More From Forbes

Hr experts explain 16 benefits of training and development.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Whether employers are offering educational training sessions for their staff members through in-person annual conferences and workshops or a virtual webinar series during a shelter-in-place global pandemic, most business leaders will agree it’s a smart move to invest in the career growth opportunities of your workforce to retain their support.

Below, 16 members of Forbes Human Resources Council discuss the prime benefits of online and in-person educational training programs or events, which have contributed to their team’s success and solidified company loyalty and partnership.

Forbes Human Resources Council members share their insight.

1. It Showcases Top Talent

Organizations that truly care for their talent recognize that the experiential learning opportunities within workspaces can sometimes be limited. Hence offering in-person or online training programs is a strategic way to bridge that gap and showcase to your talent that their growth is valued. In the long run, investing in developing talent always pays off and is in the organization’s best interest. - Rohit Manucha , SIH AGH

2. It Provides Incentive Values

Offering educational programs to our employees is beneficial because it increases their loyalty to the company as they feel we are giving them the tools they need to not only succeed in their role, but to grow. It also demonstrates that we value them as employees. - Alexis Schuman , Sexy Fish

3. It Results In LowerTurnover Rates

A team that is invested in feels valued, which creates loyalty! I have found both online and in-person training has contributed to team success. It creates a positive career trajectory and has resulted in lower turnover. - Robin Page , Bluedot Innovation

4. It Encourages Grade A Effort

Regardless of budget, training and educational opportunities need to be a part of every company’s offerings. Providing high-performing, high-potential employees with specialized training or tailored educational opportunities pays big dividends through their increased expertise and loyalty. In many cases, this extends the amount of time they stay with the company by a year or more. - Danny Speros , Zenefits

5. It Shows Transparency

Loyalty is reciprocal. When leaders provide learning opportunities that align with career path objectives it is a fantastic way to demonstrate commitment to employees. When the two are paired together, there is a transparent vision of what these additional learning opportunities can provide in terms of career growth, knowledge expansion, cross-functional training and succession! - Sandi Wilson , FinTek Consulting

6. It Reinforces Meaningful Career Options

Learning and development helps to reinforce meaningful career options and mobility to include upskilling and reskilling. Skill-based hiring opens candidate aperture and instead of competing for talent, externally, you’re investing in talent, internally. - Britton Bloch , Navy Federal

7. It Boosts L&D Curiosity

Learning and development (L&D) is now a key driver for many people when considering new roles. Loyalty is often seen as one of the main benefits of L&D, but it also helps to attract new candidates. Be sure to highlight your L&D program in your recruitment marketing and feature examples of possible career paths so that candidates and employees are both aware of the opportunities. - Kim Pope , WilsonHCG

8. It Offers Flexible Learning And Networking Opportunities

Most employees are constantly looking to advance their careers, and if you fail to help them, your talent will look for these opportunities elsewhere. People want an upskill learning opportunity that is accessible anywhere and anytime. You also need to ensure your upskilling allows learners to connect with one another. Employees learn best when part of a community. Moreover, they feel more engaged and loyal. - Erik van Vulpen , AIHR | Academy to Innovate HR

Forbes Human Resources Council is an invitation-only organization for HR executives across all industries. Do I qualify?

9. It Drives Employee Self-Initiative And Growth

Accessible on-demand training gives employees agency to pursue their career goals, lean into their interests and take their future into their own hands. Employees are much more likely to stay in a job where they feel support and opportunities to grow. Even if they move to a different position within the company, they will stay with your company because they know they have a future with you. - Courtney Pace , FedEx Employees Credit Assoc.

10. It Prepares A Stronger Workforce

Employees today need more specialized and technical skills as well as the development of soft skills like collaboration and emotional intelligence. The best training programs focus on reskilling, upskilling and coaching for both executives and staff. Companies who aren’t preparing their workforce for the future could quickly find themselves scrambling for talent while those who are preparing reap the rewards - John Morgan , LHH

11. It Contributes To Team Success

In a hybrid work environment, getting people together across locations to keep knowledge current is critical. Digital learning gives us the opportunity to learn in the place of work, create connections across teams and identify opportunities for partnership. This increases engagement, builds a learning culture and contributes to our success. Also, who doesn’t love being recognized as an expert? - Jennifer Rozon , McLean & Company

12. It Highlights Long-Term Career Objectives

Employees are in an unprecedented market where company loyalty is at the forefront for retaining key talent. Employees are looking for companies that are not only focused on the bottom line but their long-term career objectives. Offering, recommending and assigning training within an employees' current and future career interests have made the difference in showing true investment. - Nakisha Griffin , Virtual Enterprise Architects

13. It Fosters Appreciation

Offering training and education will increase engagement because we all know how much that improves the bottom line. If you really want to ramp it up, offer your employees educational opportunities beyond your industry or their core competencies. Help them to expand their horizons. They'll be forever grateful, loyal and have more depth to offer your company and customers. - Richard Polak , American Benefits Council

14. It Keeps The Company Competitive

According to a recent survey by Amdocs , nearly two-thirds of employees say they would leave their jobs due to a lack of growth and training opportunities. In today’s workplace, offering educational training programs is essential to employee engagement and retention. In addition to helping the company remain competitive, it strengthens employee relationships in a team-building environment. - John Feldmann , Insperity

15. It Aligns Employees To New Areas Of Focus

Not only do we offer learning stipends and access to learning platforms, when we launch new programs and offerings, we pulse our employee base to learn who would like to gain expertise in those areas. We then train employees, aligning them to new areas of focus for the company rather than hiring externally. Those employees then become engaged subject matter experts when these services launch. It's a win-win. - Nicole Fernandes , Blu Ivy Group

16. It Breeds Knowledge And Satisfaction

Engaged employees are always learning. We rolled out 350 workshops for more than 10,000 employees to embed our corporate strategy. Our skills-based development approach offers on-demand courses to advance expertise and critical skills for career growth. The impact has been tangible. Our people are among the most knowledgeable in the industry. Investment in our people breeds satisfaction and loyalty. - Sharon Doherty , Finastra

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

3Q: Evaluating skills, education, and workforce training in the US

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

As part of the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future’s recent series of research briefs, MIT professors Paul Osterman and Kathleen Thelen highlight the critical role skills, education, and workforce training play in providing pathways to employment for low- and moderate-skilled workers and young adults. The briefs explore the highly fragmented U.S. workforce training system and comparable programs in Europe, in which the private sector is significantly engaged in both the classroom and the workplace. In the brief, “ Skill Training for Adults ,” Osterman, professor of human resources and management at the MIT Sloan School of Management, shares findings from a new original survey describing how working adults obtain their job skills. He identifies significant inequalities and disparities in the job market that an effective training policy can address. Thelen, the Ford Professor of Political Science at MIT, teamed with Christian Lyhne Ibsen, associate professor at Michigan State University School of Human Resources and Labor Relations, for the brief, “ Growing Apart: Efficiency and Equality in the German and Danish VET Systems .” They explore examples of Europe’s vocational education and training (VET) systems and compare recent developments in Germany and Denmark, two of the most successful systems of firm-sponsored VET. Osterman and Thelen speak here on their recent work. Q: In your brief, you share findings from a survey about how adults obtain their job skills. What does the survey tell us about how skills are acquired and the role of the public and private sectors in training for these skills? Osterman: The survey you refer to was executed in January 2020, and provides the most complete data available on training provided to adults by their employers and on training that people undertake on their own. Overall, 56 percent of adults received formal employer training in the year prior to the survey and 19 percent sought out skills training on their own. Whether these rates are high or low is somewhat in the eyes of the beholder, but what is clearly unacceptable is that the rates for non-whites are well below those of whites, and the training obtained by those with less than a college degree is below that of people with a four-year degree. Additionally, people who received employer training were more likely than others to seek out training on their own, and so the disparities were reinforced. Q: What are the critical elements of the European training model? What are some key lessons the United States can learn from Europe’s vocational education and training systems? Thelen: Vocational training in many European countries takes place within companies, typically accompanied by a compulsory school-based component offering more theoretical content. Trainees thus acquire skills that are very close to labor-market needs — and apprenticeships sometimes segue directly into employment. At the same time, however, employers who take apprentices are not allowed to train narrowly for their own needs alone. Rather, they are required to train broadly and to standards and occupational profiles decided nationally by committees composed of representatives of business, unions, and the state. These systems are also subject to monitoring and oversight to enforce nationally defined standards in terms of both the content and the quality of training. Such systems ensure smooth school-to-work transitions, while also providing trainees with skills that are certified and portable across the labor market.

Many U.S. employers are afraid that if they invest in worker training, other companies will simply poach their talented workers. European countries have avoided this problem through soft obligations to train or financial incentives through which companies receive support for their training efforts. In Europe, such solutions are sometimes established at the industry level through business associations that collect levies from their members. In the U.S., one could envision the state playing a stronger role in establishing and financing collective training funds to support firms that invest in training workers.

U.S. companies could also learn from their European peers when it comes to providing input to educational providers about what skills they need. State or local governments could establish forums to bring together educational providers, employers, and trade unions to make sure that local skills demands are met and that trainees acquire the skills they need to secure stable, well-paid employment. Q: What are some key examples of creative skill-training initiatives that have been successful in the United States, and what policies should we consider to scale these programs? Osterman: A central argument in my brief is that successful best-practice training models exist. In many respects, we know what works, and hence the issue is how to go to scale. In terms of what works, we know that people who obtain a degree or certificate from community colleges experience significant earnings gains. We also have good models of job training programs such as Project QUEST in San Antonio and JVS in Boston. The core characteristics of these training programs is that they have relationships with employers such that they know what is needed to fill jobs, and they provide support services to trainees for transportation costs, childcare, etc., so that they can complete the training and succeed. The core challenge is how to diffuse these models at scale. Too many community college enrollees fail to complete their programs, and the job-training programs I describe are small relative to the size of their labor markets. Additionally, many employers do not take either community colleges or high-quality training programs seriously as a source of employees. In the brief, I argue that, in part, the problem is resources: public support for community colleges and training programs has fallen or stagnated in recent years. In part, the challenge is organizational reform, notably encouraging community colleges to adopt best practices and expanding quality training programs and weeding out weak ones. But the deepest challenge is building regional compacts of employers, governments, community colleges, and community groups that come together with a shared commitment to build a real skill development system in their region. I describe good starts in several regions around the country.

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future

- Department of Political Science

- School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences

- MIT Sloan School of Management

Related Topics

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

- Political science

- Labor and jobs

- Education, teaching, academics

Related Articles

3 Questions: Thomas Kochan on new policies to shape work of the future

The changing world of work

MIT report examines how to make technology work for society

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Bridging the heavens and Earth

Read full story →

MIT OpenCourseWare sparks the joy of deep understanding

A wobble from Mars could be sign of dark matter, MIT study finds

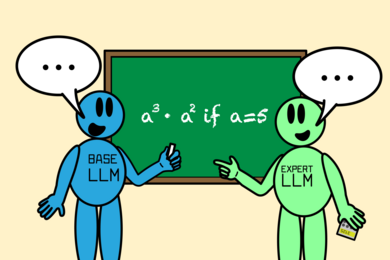

Enhancing LLM collaboration for smarter, more efficient solutions

Affordable high-tech windows for comfort and energy savings

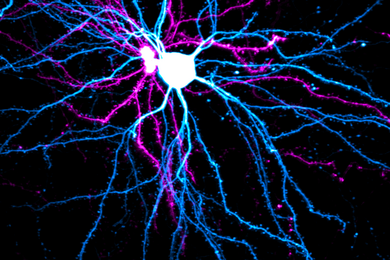

Finding some stability in adaptable brains

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

What works in workforce development—and how can it work better?

Subscribe to global connection, brent orrell , brent orrell senior fellow - american enterprise institute greg wright , greg wright fellow - global economy and development harry holzer , hh harry holzer john lafarge jr. sj professor of public policy - georgetown university mccourt school of public policy rachel lipson , and rl rachel lipson former director, project on workforce - harvard kennedy school weiner center on public policy david deming david deming isabelle and scott black professor of political economy - harvard university.

March 8, 2023

For the past two years, a bipartisan group of researchers and analysts convened by the American Enterprise Institute, the Brookings Institution, and the Harvard Kennedy School’s Project on Workforce has reviewed the evidence on the effectiveness of the United States’ federal-state workforce education and training system. Our group—the Workforce Futures Initiative (WFI)—has reached some surprising and hopefully useful conclusions about how our nation can improve its investments in job training.

The good news is that federal spending on workforce development—including the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) system—improves disadvantaged worker outcomes. The bad news is that improvements are quite modest. In the words of one of our group members, we appear to be “stuck in a low-resource, low-efficacy” equilibrium. Small benefits at low levels of funding discourage higher levels of investment; yet without additional funding, it is unlikely we’ll see substantial improvement. At the same time, students and workers lack other options to finance training—for instance, Pell grants do not cover noncredit or shorter-term training efforts. The WIOA system, and the workers who use it, are caught in a policy catch-22.

Greater public investment in workforce development programs is needed. But these additional investments should be targeted toward programs and practices that have proven successful and can be scaled, or that provide information that is critical to diagnose the needs of a rapidly changing labor market. Examples include sectoral employment programs, job counseling and supportive services, improvements to data systems to better track program performance and improve our understanding of changing skill demands, and pilot programs to test ways of increasing system flexibility and innovation.

Sectoral employment programs substantially improve employment and wage outcomes for workers. These programs are distinctive in their focus on high-growth sectors of the economy such as information technology, health care, and advanced manufacturing. The federal government should substantially increase investment in these programs, focusing on replication and scaling of programs with track records of success. For our most disadvantaged students and workers, who sometimes have difficulty qualifying for participation in these programs, additional supports and “on-ramp” programs should be considered.

We should also strengthen the “connective tissue” of supportive services. Education, training, and employment systems are decentralized, and the bewildering array of options can overwhelm workers who are juggling busy lives on top of their training needs. Barriers related to transportation, child care, and mental health often cause program participants to exit programs early. This is a lost opportunity. Moreover, the evidence shows that counseling and supportive services, both of which are integral to the sectoral strategies mentioned above, substantially increase program completion and labor market success. Investments in support services for post-secondary training participants such as community college students and displaced workers can yield high returns.

A third critical need is for innovation in the nation’s workforce data infrastructure. Workers are pressured by technological change and automation, which makes it critical to modernize our education and training systems to keep up with change. We need better information about which jobs are growing and which programs are effective at developing needed skills. For example, one member of our group is developing a framework for decentralizing regional labor market information systems that will help states and regions develop deep and agile data systems for measuring program performance as well as changing skill and employment needs.

Finally, the evidence of “what works” in training and workforce development programs is remarkably sparse . Even if political will existed for a full-scale, far-reaching reform of WIOA, community colleges, and other elements of our workforce system, it would be imprudent, based on what we know, to recommend a one-size-fits-all model for all regions and priority industries.

In light of this uncertainty, we need strategies that unleash innovation at the state and regional levels and among industries. Part of the answer to this challenge is providing state and local officials substantial flexibility in testing new program structures and models that bridge public, private, and nonprofit institutions; are responsive to fast-changing demand patterns; and meet the differing needs of populations ranging from English language learners to working adults to the formerly incarcerated. Such experiments deserve more financial and implementation support from the federal government, opportunities for administrative flexibility, and comprehensive evaluation to help inform future rounds of system reform.

Related Content

Pam Harder, Greg Wright

February 1, 2023

Dany Bahar, Carlos Daboin Contreras, Greg Wright

October 17, 2022

Mark Muro, Lavea Brachman, Yang You

January 24, 2023

Labor & Unemployment

Global Economy and Development

Quinn Sanderson

July 9, 2024

Simon Hodson

May 8, 2024

Harry J. Holzer

April 16, 2024

What Works: Ten Education, Training, and Work-Based Pathway Changes That Lead to Good Jobs

Ten education, training, and work-based pathway changes that lead to good jobs, good job definition, explore the data, full report, executive summary.

All along the journey from youth to young adulthood, there are critical junctures at which a change in pathway can have a tremendous impact on a young person’s future. What Works: Ten Education, Training, and Work-Based Pathway Changes That Lead to Good Jobs identifies 10 pathway changes with the greatest potential to improve employment outcomes for young adults. The report uses the Pathways-to-Career policy simulation model, developed by CEW researchers using longitudinal data, to identify promising junctures at which strategic interventions could increase the likelihood of working in a good job.

We define a good job as one that pays a minimum of approximately $38,000 in 2020 dollars for workers younger than age 45 and a minimum of approximately $49,000 for workers ages 45 and older. For the young adults who are the focus of this report—30-year-old workers nationwide—these jobs pay a median of approximately $57,000 annually. Among 30-year-old workers who have a good job, one-quarter earn less than $46,000 annually, while one-quarter earn more than $76,000. Workers with good jobs are more likely than those with low-paying jobs to have access to healthcare and retirement benefits at work.

Many of the most promising pathway changes involve increasing educational attainment, especially progressing toward attainment of a bachelor’s degree, while other promising pathway changes replace or combine classroom learning with on-the-job learning. Importantly, the effectiveness of the 10 pathway changes varies by race, gender, and class. For example, specializing in career and technical education (CTE) in high school increases the likelihood of having a good job at age 30 for white and Black/African American young adults, but reduces the likelihood of having a good job at age 30 for Hispanic/Latino young adults. Nearly every pathway change has the potential to put more men, white youth and young adults, and individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in good jobs at age 30.

Explore the number of young people who could benefit from each pathway change, overall and by race, gender, and class:

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), 1997–2015.

Note: Good jobs are those paying approximately $38,000 or more in 2020 dollars, adjusted for geographic differences in cost of living. “M” indicates millions; “k” indicates thousands. For details about who is eligible for each scenario, see Appendix A in the full report. Blue-collar occupations include jobs in farming, fishing, and forestry; construction, extraction, maintenance, and repair; and production, transportation, and material moving. Other high-paying occupations include jobs in business, finance, management, law, social science, and skilled healthcare. Low-paying occupations include jobs in the arts, community services, education, food and personal services, and healthcare support. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Layered Pathway Changes

Layering certain pathway changes can further boost the number of workers in good jobs at age 30. For example, ensuring college completion after putting the 4.8 million eligible academically prepared young adults on the pathway to a bachelor’s degree could result in 1.2 million more young adults in the current cohort in good jobs at age 30 than are expected at present. That’s 435,000 more young adults in good jobs than would result from increasing enrollment in bachelor’s degree programs alone. Ensuring completion of an associate’s or bachelor’s degree after putting young adults on the pathway to an associate’s degree and ensuring continuous employment from ages 20 to 22 after placing young adults in STEM occupations could also enhance the impact of any one of these pathway changes on its own.

Targeted Interventions

Differences in effectiveness and eligibility mean that narrowing the gaps in good jobs is not as simple as making all 10 pathway changes equally available to youth and young adults regardless of race, class, and gender. That approach would more likely increase the good jobs gaps by race and gender than shrink them, and it would have little effect on the good jobs gap by class. To narrow the gaps in the likelihood of having a good job, effective interventions would need to be targeted to underserved groups as part of a coordinated and comprehensive all-one-system approach that addresses persistent inequalities in society arising outside the classroom and workplace.

What Works: Ten Education, Training, and Work-Based Pathway Changes That Lead to Good Jobs identifies 10 pathway changes with the greatest potential to improve employment outcomes for young adults.

- Press Release

Comments are closed.

Privacy Policy

Eit accessibility.

- Book / Chapter

- Media Mentions

- Media Inquiries

- Explore Our ROI Rankings

- Good Jobs Data

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The State of American Jobs

- 4. Skills and training needed to compete in today’s economy

Table of Contents

- 1. Changes in the American workplace

- 2. How Americans assess the job situation today and prospects for the future

- 3. How Americans view their jobs

- 5. The value of a college education

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

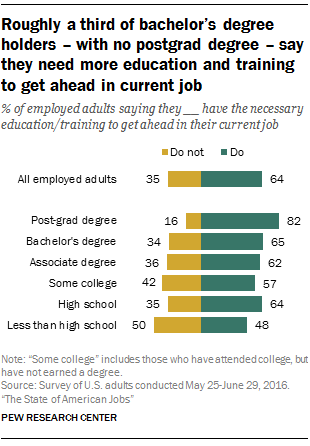

There is a widespread feeling among U.S. adults that the workplace is evolving and they will have to continually update their skills and training in order to succeed in a career. A narrow majority (54%) of adults who are currently in the labor force say that it will be essential for them to get training and develop news skills throughout their work life in order to keep up with changes in the workplace. An additional 33% say this will be important, but not essential. Only 12% of workers say ongoing training will not be important for them. Even among employed adults who say they have the skills and education they need to get ahead in their job, roughly half (47%) say they will need ongoing training throughout their career.

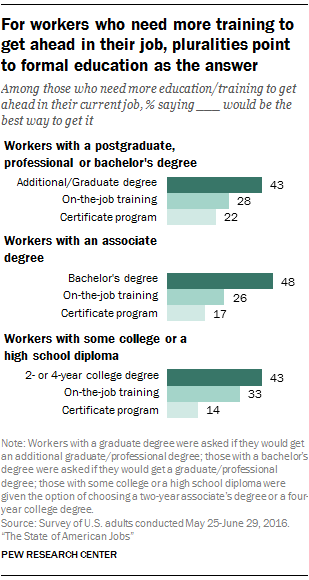

For some people, acquiring new skills won’t be a necessity just in the future: 35% of working adults say they need more education and training now in order to get ahead in their job or career. A plurality of those who say they need more training say the best way for them to get that training would be through additional higher education. This is true across levels of educational attainment: Pluralities of four-year college graduates say they would pursue a graduate degree, two-year college graduates say they would try to get a four-year degree, and high school graduates say they would go to college. About a third of workers who say they need more training believe receiving on-the-job training would be the best way to gain the skills they need to get ahead, while fewer point to certificate programs as the most promising pathway.

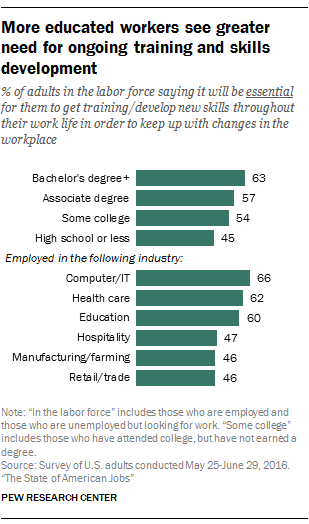

Roughly four-in-ten employed adults (45%) say they have taken a class in the past year or have gotten extra training to learn, maintain or improve their jobs skills. About half of these workers report that they did this at the behest of their employer, but significant shares also report that they sought out additional training in order to earn more money, get a new job or get a promotion.

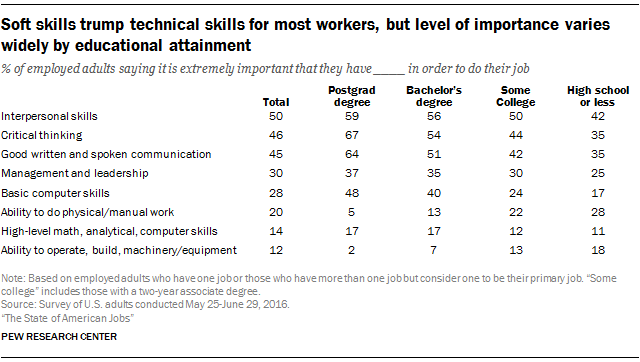

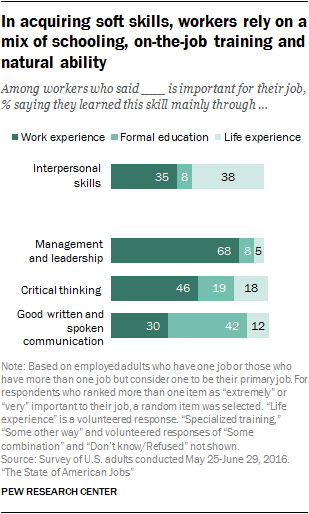

While the skills American workers rely on to do their jobs vary widely by education and industry, interpersonal, communications and analytical skills are the most dominant across fields. And the skills that U.S. workers are using in their jobs these days don’t necessarily coincide with what most Americans view as the cutting-edge job skills of today. While an overwhelming majority of adults (85%) say having a detailed understanding of how to use computer technology is extremely or very important for a worker to be successful in today’s economy, far fewer employed adults say they need this skill set in their current job.

Many say ongoing training and skills acquisition are essential in today’s workplace

Overall, 54% of U.S. adults in the labor force say that, in order to keep up with changes in the workplace, it will be essential for them to get training and develop new skills throughout their work life. A third say, while not essential, it will be important for them to continually update their skills. Young adults are more likely than their older counterparts to see skills and training as essential (61%), perhaps because of the longer trajectory they have ahead of them. Even so, 56% of those ages 30 to 49 say ongoing training will be essential for them, as do roughly four-in-ten workers ages 50 and older.

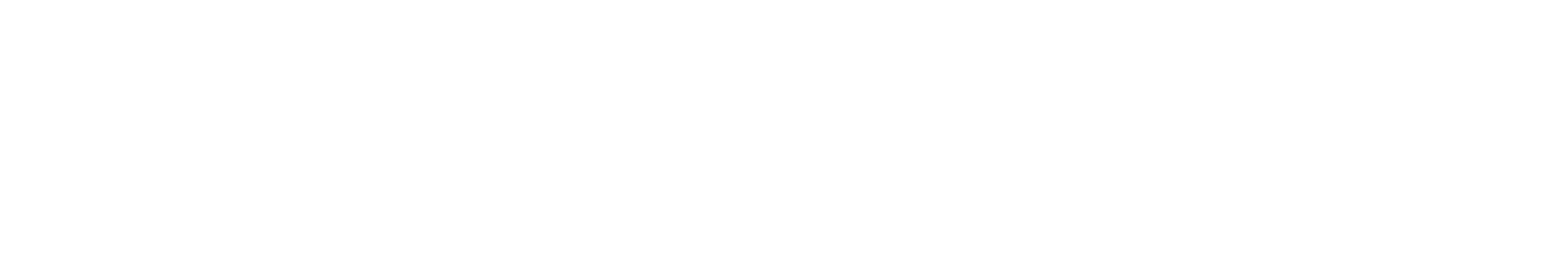

There is a significant education gap in perceptions about the need for ongoing training and skills development. Fully 63% of those with a bachelor’s or graduate degree say it will be essential for them to update their skills in order to keep up with the pace of change in the workplace. Some 57% of those with a two-year college degree say this will be essential for them, as does a similar share of those with some college education but no degree (54%). Among those with a high school diploma or less, 45% say it will be essential for them to get training and develop new skills throughout their career.

Adults who are working in certain STEM-related industries are among the most likely to say ongoing training and skills development will be essential for them. Two-thirds of employed adults (66%) who work in computer programming and information technology say this will be essential for them. And roughly six-in-ten workers who are in the health care industry (62%) say the same. By contrast, about half of adults working in hospitality (47%), manufacturing or farming (46%) or retail or wholesale trade (46%) see training and skills development as an essential part of their future work life. 27

Significant share of workers have taken a class or gotten extra training in the past year

To be sure, many workers are already engaged in an ongoing effort to improve their skills or learn new ones. Fully 45% of employed adults say that, in the past 12 months, they have taken a class or gotten extra training to learn, maintain or improve job skills. Workers younger than 50 are somewhat more likely than those ages 50 and older to say they have sought out this type of training (47% vs. 39%).

In keeping with the finding that more highly educated Americans are among the most likely to say they will need to keep their skills up to date throughout their work life, 56% of working adults with a bachelor’s degree or more education say they have taken a class or gotten training in the past 12 months, as do 54% of those with a two-year college degree. Among those with some college education, 43% say they have taken a class or received training in the past 12 months. By comparison, 30% of workers with a high school diploma or less education say they have done this.

Roughly six-in-ten workers in the health care (58%) and education (62%) fields say they have gotten training or taken a class in the past year. 28 Workers in the hospitality (28%), retail and trade (32%) and manufacturing and farming (34%) sectors are significantly less likely to report the same.

Workers are somewhat less likely to report having taken a class or gotten extra training for a license or certification – 30% of all workers say they have done this over the past year. Once again college graduates are among the most likely to have taken these steps, while those who never attended college are among the least likely.

Adults who work in the health care industry are among the most likely to say they have had training or taken a class related to licensing or certification – fully half (49%) say they have done this in the past year. About a third of workers in the education sector (32%) say they have taken a class related to licensing or certification in the past year, as do roughly a quarter of those working in manufacturing and farming and in hospitality.

Employers often provide the impetus for workers to get additional training, but desire for job advancement is also a motivator

Overall, 37% of employed adults report that they have taken a class or gotten extra training – either to improve their job skills or work toward a license or certification. Among this group, about half (52%) say they did this because their employer required it. Roughly a third (34%) say they needed the extra training in order to earn more money. And about a quarter say they needed the extra training in order to get a new job (26%) or to be promoted in their current job (25%).

Younger workers who took a class or got extra training in the past year are much more likely than their older counterparts to say they needed to do this in order to get a new job – 38% of workers younger than 30 say this is a reason that they got extra training, compared with roughly one-in-five (21%) workers age 30 or older.

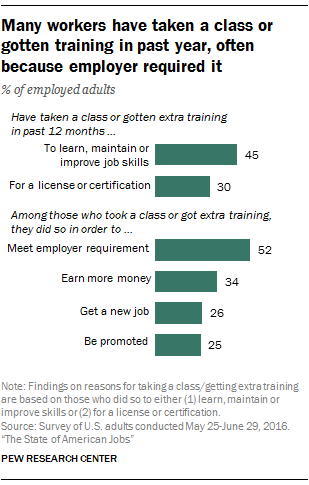

The motivations for seeking additional training are highly correlated with workers’ income. Among those who say they took a class or got additional training in the past year, 47% of workers with annual household incomes less than $30,000 say they did this in order to earn more money. Some 37% of middle-income workers (those earning between $30,000 and $74,999) say the same. And for those with incomes of $75,000 or more, only 27% say earning more money was a reason why they sought additional training.

Similarly, while 45% of lower-income workers say they took a class or got more training in order to get a new job, fewer middle-income (28%) and higher-income (17%) workers say the same.

Among workers who have not taken a class or gotten extra training in the past year, the vast majority (74%) say they didn’t need to take these steps in order to advance in their job or career. For the remaining 25% of this group, having the time and resources to seek out additional training can be significant barriers.

Among those who may have needed training in order to advance in their job but did not get it, some 57% say that the inability to take time off from work or from other responsibilities was a contributing factor. (This translates into 14% of all workers who did not take a class or get extra training in the past 12 months.) And 45% of these workers say they couldn’t afford to take a class or get additional training. Relatively few (26%) say that they didn’t know this type of training was available.

Roughly one-in-four job seekers took a class or got skills training in the past year

Among adults who are unemployed but looking for work, 26% say they took a class or got extra training in the past year to help them get a job. Those with at least some college education are significantly more likely than those who never attended college to say they took this step (34% vs. 18%).

Among those who did not take a class or get additional training in order to help them get a job, 64% say they couldn’t afford to do so. Some 55% say they couldn’t take time away from other responsibilities, and 35% say they didn’t know this type of training was available.

About a third of today’s workers say they don’t have the education and training they need to get ahead at work

While most workers expect training and skills development to be an integral part of their work life in the future, and many are taking classes and getting certifications in real time, about a third (35%) of workers say they lack the education and training necessary to get ahead in their current job; 64% of employed adults say they have the education and training needed to get ahead.

Not surprisingly, younger workers are among the most likely to say they do not have the necessary training to get ahead in their current job. Some 46% of workers younger than 30 say they don’t have the education and training they need to get ahead in their job. About a third (34%) of workers age 30 to 49 say the same, as do 26% of workers ages 50 and older.

Educational attainment is linked to workers’ feelings of job preparedness, but mainly at the extremes. Workers with a postgraduate degree are by far the most likely to say they have the necessary education and training to get ahead in their job or career. Among this group, 82% say they have what they need to get ahead; only 16% say they need more education and training.

Among workers with a bachelor’s degree, a two-year college degree, some college or a high school diploma, roughly equal shares say they need more education and training in order to get ahead in their current job. Workers who lack a high school diploma are among the most likely to say they need more education and training (50%); only about half (48%) say they have the training they need to get ahead.

Higher education and on-the-job training are seen as best avenues for further skills development

For workers who feel ill-equipped to get ahead in their current job, there is no clear-cut solution for obtaining more education and training. Pluralities say going back to school to obtain a higher degree would be the best way to get the training they need. But a significant share say on-the-job training aimed at learning or improving a specific skill would be the best approach for them to take. A smaller share say pursuing a certificate program in a professional, technical or vocational field would be the best way for them to get the training they need.

Among workers with a bachelor’s or graduate degree who say they need more education or training to get ahead in their career, 43% say the best way for them to get the training they need would be to pursue postgraduate education (a graduate degree for those with a bachelor’s, and an additional graduate or professional degree for those who’ve already completed graduate schooling). About three-in-ten (28%) of these workers say on-the-job training would be the best avenue to pursue, and 22% say they would complete a certificate program.

The pattern is similar for workers with less formal education who say they need more training to get ahead in their job. Among those with a two-year college degree, 48% say they would get a four-year degree, while 26% say on-the-job training would be the best approach to take and 17% say they would complete a certificate program.

And for those who haven’t completed college, a plurality (43%) say they would pursue a two-year or four-year college degree in order to gain the training they need to get ahead at work, a third would turn to on-the-job training and 14% say they would complete a certificate program.

Across levels of educational attainment, women are more likely than men to say that pursuing formal education would be the best way to get the training they need to get ahead in their current job. Among those who say they need more education and training, 52% of women and 35% of men say getting a higher degree would be the best approach. Men are more likely than women to say that on-the-job training would be best (36% vs. 25%) or to say they would pursue a certificate program in order to get the training they need (20% vs. 13%).

Workers who say they would opt for on-the-job training are mostly positive about their prospects for getting it. A majority (65%) say their employer offers this type of training. An additional 14% say that while the training may not be offered in their workplace, their employer would help them get the training they need. Some 16% say their employer would not assist them in getting training.

Among adults who are unemployed and looking for work, only about half (46%) feel they have the education and training needed to get the kind of job they want; 52% say they need more education or training. These job seekers are divided over the best approach to getting the qualifications they need. About four-in-ten (42%) say getting additional formal education would be the best way. Roughly the same share (37%) say completing a certificate program in a professional, technical or vocational field would be a better strategy. An additional 16% point to some other approach.

Half of all workers say interpersonal skills are crucial to their job

In today’s high-tech, information economy, most American workers rely more on soft skills than on technical skills to do their jobs. Fully half of employed adults say interpersonal skills such as patience, compassion and getting along with people are extremely important in their job. An additional 40% say these skills are very important. This skill set is especially important for workers who are in the health care and education sectors – 64% of health care workers and 67% of education workers say it’s extremely important for them to have interpersonal skills in order to do their job.

A similar share of workers say they rely heavily on critical thinking skills such as evaluating facts and making decisions in doing their jobs. Some 46% of all workers say these skills are extremely important in doing their job, and 40% say they are very important. Again, these skills are more important to workers in the health care and education fields than they are for workers in the hospitality, manufacturing and farming, and retail sectors.

Good written and spoken communications skills are highly important as well. Some 45% of workers say it is extremely important that they have good communications skills in order to do their job, and 44% say this is very important. These skills are most important for people working in education.

Management and leadership skills are extremely important for three-in-ten of today’s workers, and an additional 40% say these skills are very important. These skills cut across industries, with roughly equal shares of workers saying they rely on them to do their job.

About three-in-ten workers (28%) say computer skills such as word processing or creating spreadsheets are extremely important for their job.

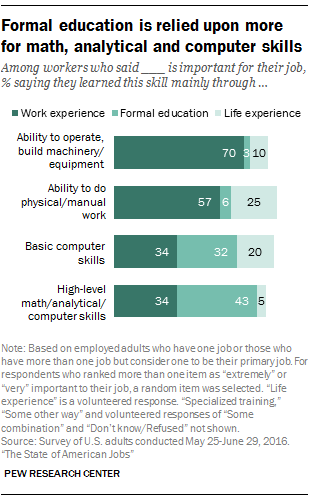

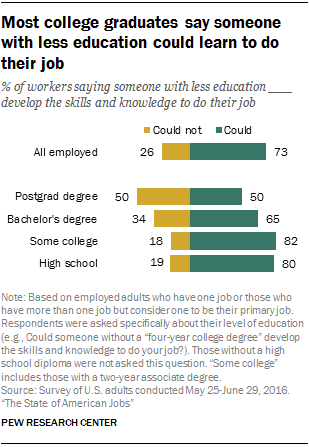

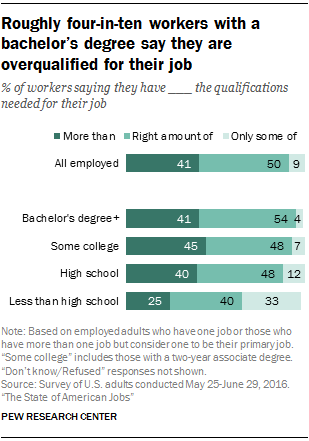

A third tier of job skills includes a mix of analytical and manual skills. Some 14% of workers say it’s extremely important for them to have high-level math, analytical or computer skills in order to do their job, and an additional 25% say these skills are very important.