Qualitative Research Methods

- Gumberg Library and CIQR

- Qualitative Methods Overview

Phenomenology

- Case Studies

- Grounded Theory

- Narrative Inquiry

- Oral History

- Feminist Approaches

- Action Research

- Finding Books

- Getting Help

Phenomenology helps us to understand the meaning of people's lived experience. A phenomenological study explores what people experienced and focuses on their experience of a phenomenon. As phenomenology has a strong foundation in philosophy, it is recommended that you explore the writings of key thinkers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty before embarking on your research. Duquesne's Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center maintains a collection of resources connected to phenomenology as well as hosting lectures, and is a good place to start your exploration.

- Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center

- Husserl, Edmund, 1859–1938

- Heidegger, Martin, 1889–1976

- Sartre, Jean Paul, 1905–1980

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, 1908–1961

Books and eBooks

Online Resources

- Phenomenology Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry.

- << Previous: Qualitative Methods Overview

- Next: Case Studies >>

- Last Updated: Aug 18, 2023 11:56 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/qualitative_research

- Privacy Policy

Home » Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Phenomenology

Definition:

Phenomenology is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with the study of subjective experience and consciousness. It is based on the idea that the essence of things can only be understood through the way they appear to us in experience, rather than by analyzing their objective properties or functions.

Phenomenology is often associated with the work of philosopher Edmund Husserl, who developed a method of phenomenological inquiry that involves suspending one’s preconceptions and assumptions about the world and focusing on the pure experience of phenomena as they present themselves to us. This involves bracketing out any judgments, beliefs, or theories about the phenomena, and instead attending closely to the subjective qualities of the experience itself.

Phenomenology has been influential not only in philosophy but also in other fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology, where it has been used to explore questions of perception, meaning, and human experience.

History of Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a philosophical movement that began in the early 20th century, primarily in Germany. It was founded by Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher who is often considered the father of phenomenology.

Husserl’s work was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, particularly his emphasis on the importance of subjective experience. However, Husserl sought to go beyond Kant’s transcendental idealism by developing a rigorous method of inquiry that would allow him to examine the structures of consciousness and the nature of experience in a systematic way.

Husserl’s first major work, Logical Investigations (1900-1901), laid the groundwork for phenomenology by introducing the idea of intentional consciousness, or the notion that all consciousness is directed towards objects in the world. He went on to develop a method of “bracketing” or “epoche,” which involved setting aside one’s preconceptions and assumptions about the world in order to focus on the pure experience of phenomena as they present themselves.

Other philosophers, such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre, built on Husserl’s work and developed their own versions of phenomenology. Heidegger, in particular, emphasized the importance of language and the role it plays in shaping our understanding of the world, while Sartre focused on the relationship between consciousness and freedom.

Today, phenomenology continues to be an active area of philosophical inquiry, with many contemporary philosophers drawing on its insights to explore questions of perception, meaning, and human experience.

Types of Phenomenology

There are several types of phenomenology that have emerged over time, each with its own focus and approach. Here are some of the most prominent types of phenomenology:

Transcendental Phenomenology

This is the type of phenomenology developed by Edmund Husserl, which aims to investigate the structures of consciousness and experience in a systematic way by using the method of epoche or bracketing.

Existential Phenomenology

This type of phenomenology, developed by philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre, focuses on the subjective experience of individual existence, emphasizing the role of freedom, authenticity, and the search for meaning in human life.

Hermeneutic Phenomenology

This type of phenomenology, developed by philosophers such as Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur, emphasizes the role of interpretation and understanding in human experience, particularly in the context of language and culture.

Phenomenology of Perception

This type of phenomenology, developed by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, emphasizes the embodied and lived nature of perception, arguing that perception is not simply a matter of passive reception but is instead an active and dynamic process of engagement with the world.

Phenomenology of Sociality

This type of phenomenology, developed by philosophers such as Alfred Schutz and Emmanuel Levinas, focuses on the social dimension of human experience, exploring how we relate to others and how our understanding of the world is shaped by our interactions with others.

Methods of Phenomenology

Here are some of the key methods that phenomenologists use to investigate human experience:

Epoche (Bracketing)

This is a key method in phenomenology, which involves setting aside one’s preconceptions and assumptions about the world in order to focus on the pure experience of phenomena as they present themselves. By bracketing out any judgments, beliefs, or theories about the phenomena, one can attend more closely to the subjective qualities of the experience itself.

Introspection

Phenomenologists often rely on introspection, or a careful examination of one’s own mental states and experiences, as a way of gaining insight into the nature of consciousness and subjective experience.

Descriptive Analysis

Phenomenology also involves a careful description and analysis of subjective experiences, paying close attention to the way things appear to us in experience, rather than analyzing their objective properties or functions.

Another method used in phenomenology is the variation technique, in which one systematically varies different aspects of an experience in order to gain a deeper understanding of its structure and meaning.

Phenomenological Reduction

This method involves reducing a phenomenon to its essential features or structures, in order to gain a deeper understanding of its nature and significance.

Epoché Variations

This method involves examining different aspects of an experience through the process of epoché or bracketing, to gain a more nuanced understanding of its subjective qualities and significance.

Applications of Phenomenology

Phenomenology has a wide range of applications across many fields, including philosophy, psychology, sociology, education, and healthcare. Here are some of the key applications of phenomenology:

- Philosophy : Phenomenology is primarily a philosophical approach, and has been used to explore a wide range of philosophical issues related to consciousness, perception, identity, and the nature of reality.

- Psychology : Phenomenology has been used in psychology to study human experience and consciousness, particularly in the areas of perception, emotion, and cognition. It has also been used to develop new forms of psychotherapy, such as existential and humanistic psychotherapy.

- Sociology : Phenomenology has been used in sociology to study the subjective experience of individuals within social contexts, particularly in the areas of culture, identity, and social change.

- Education : Phenomenology has been used in education to explore the subjective experience of students and teachers, and to develop new approaches to teaching and learning that take into account the individual experiences of learners.

- Healthcare : Phenomenology has been used in healthcare to explore the subjective experience of patients and healthcare providers, and to develop new approaches to patient care that are more patient-centered and focused on the individual’s experience of illness.

- Design : Phenomenology has been used in design to better understand the subjective experience of users and to create more user-centered products and experiences.

- Business : Phenomenology has been used in business to better understand the subjective experience of consumers and to develop more effective marketing strategies and user experiences.

Purpose of Phenomenology

The purpose of phenomenology is to understand the subjective experience of human beings. Phenomenology is concerned with the way things appear to us in experience, rather than their objective properties or functions. The goal of phenomenology is to describe and analyze the essential features of subjective experience, and to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of consciousness, perception, and human existence.

Phenomenology is particularly concerned with the ways in which subjective experience is structured, and with the underlying meanings and significance of these structures. Phenomenologists seek to identify the essential features of subjective experience, such as intentionality, embodiment, and lived time, and to explore the ways in which these features give rise to meaning and significance in human life.

Phenomenology has a wide range of applications across many fields, including philosophy, psychology, sociology, education, healthcare, and design. In each of these fields, phenomenology is used to gain a deeper understanding of human experience, and to develop new approaches and strategies that are more focused on the subjective experiences of individuals.

Overall, the purpose of phenomenology is to deepen our understanding of human experience and to provide insights into the nature of consciousness, perception, and human existence. Phenomenology offers a unique perspective on the subjective aspects of human life, and its insights have the potential to transform our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Examples of Phenomenology

Phenomenology has many real-life examples across different fields. Here are some examples of phenomenology in action:

- Psychology : In psychology, phenomenology is used to study the subjective experience of individuals with mental health conditions. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of anxiety in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder, or the experience of depression in individuals with major depressive disorder.

- Healthcare : In healthcare, phenomenology is used to explore the subjective experience of patients and to develop more patient-centered approaches to care. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of chronic pain in patients, in order to develop more effective pain management strategies that are based on the patient’s individual experience of pain.

- Education : In education, phenomenology is used to study the subjective experience of students and to develop more effective teaching and learning strategies. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of learning in students, in order to develop teaching methods that are more focused on the individual needs and experiences of learners.

- Business : In business, phenomenology is used to better understand the subjective experience of consumers, and to develop more effective marketing strategies and user experiences. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of using a particular product or service, in order to identify areas for improvement and to create a more user-centered experience.

- Design : In design, phenomenology is used to better understand the subjective experience of users, and to create more user-centered products and experiences. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of using a particular app or website, in order to identify ways to improve the user interface and user experience.

When to use Phenomenological Research

Here are some situations where phenomenological research might be appropriate:

- When you want to explore the meaning and significance of an experience : Phenomenological research is particularly useful when you want to gain a deeper understanding of the subjective experience of individuals and the meanings and significance that they attach to their experiences. For example, if you want to understand the experience of being a first-time parent, phenomenological research can help you explore the various emotions, challenges, and joys that are associated with this experience.

- When you want to develop more patient-centered healthcare: Phenomenological research can be useful in healthcare settings where there is a need to develop more patient-centered approaches to care. For example, if you want to improve pain management strategies for patients with chronic pain, phenomenological research can help you gain a better understanding of the individual experiences of pain and the different ways in which patients cope with this experience.

- When you want to develop more effective teaching and learning strategies : Phenomenological research can be used in education settings to explore the subjective experience of students and to develop more effective teaching and learning strategies that are based on the individual needs and experiences of learners.

- When you want to improve the user experience of a product or service: Phenomenological research can be used in design settings to gain a deeper understanding of the subjective experience of users and to develop more user-centered products and experiences.

Characteristics of Phenomenology

Here are some of the key characteristics of phenomenology:

- Focus on subjective experience: Phenomenology is concerned with the subjective experience of individuals, rather than objective facts or data. Phenomenologists seek to understand how individuals experience and interpret the world around them.

- Emphasis on lived experience: Phenomenology emphasizes the importance of lived experience, or the way in which individuals experience the world through their own unique perspectives and histories.

- Reduction to essence: Phenomenology seeks to reduce the complexities of subjective experience to their essential features or structures, in order to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of consciousness, perception, and human existence.

- Emphasis on description: Phenomenology is primarily concerned with describing the features and structures of subjective experience, rather than explaining them in terms of underlying causes or mechanisms.

- Bracketing of preconceptions: Phenomenology involves bracketing or suspending preconceptions and assumptions about the world, in order to approach subjective experience with an open and unbiased perspective.

- Methodological approach: Phenomenology is both a philosophical and methodological approach, which involves a specific set of techniques and procedures for studying subjective experience.

- Multiple approaches: Phenomenology encompasses a wide range of approaches and variations, including transcendental phenomenology, hermeneutic phenomenology, and existential phenomenology, among others.

Advantages of Phenomenology

Phenomenology offers several advantages as a research approach, including:

- Provides rich, in-depth insights: Phenomenology is focused on understanding the subjective experiences of individuals in a particular context, which allows for a rich and in-depth exploration of their experiences, emotions, and perceptions.

- Allows for participant-centered research: Phenomenological research prioritizes the experiences and perspectives of the participants, which makes it a participant-centered approach. This can help to ensure that the research is relevant and meaningful to the participants.

- Provides a flexible approach: Phenomenological research offers a flexible approach that can be adapted to different research questions and contexts. This makes it suitable for use in a wide range of fields and research areas.

- Can uncover new insights : Phenomenological research can uncover new insights into subjective experience and can challenge existing assumptions and beliefs about a particular phenomenon or experience.

- Can inform practice and policy: Phenomenological research can provide insights that can be used to inform practice and policy decisions in fields such as healthcare, education, and design.

- Can be used in combination with other research approaches : Phenomenological research can be used in combination with other research approaches, such as quantitative methods, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular phenomenon or experience.

Limitations of Phenomenology

Despite the many advantages of phenomenology, there are also several limitations that should be taken into account, including:

- Subjective nature: Phenomenology is focused on subjective experience, which means that it can be difficult to generalize findings to a larger population or to other contexts.

- Limited external validity: Because phenomenological research is focused on a specific context or experience, the findings may have limited external validity or generalizability.

- Potential for researcher bias: Phenomenological research relies heavily on the researcher’s interpretations and analyses of the data, which can introduce potential for bias and subjectivity.

- Time-consuming and resource-intensive: Phenomenological research is often time-consuming and resource-intensive, as it involves in-depth data collection and analysis.

- Difficulty with data analysis: Phenomenological research involves a complex process of data analysis, which can be difficult and time-consuming.

- Lack of standardized procedures: Phenomenology encompasses a range of approaches and variations, which can make it difficult to compare findings across studies or to establish standardized procedures.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Qualitative study design: Phenomenology

- Qualitative study design

Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Used to describe the lived experience of individuals.

- Now called Descriptive Phenomenology, this study design is one of the most commonly used methodologies in qualitative research within the social and health sciences.

- Used to describe how human beings experience a certain phenomenon. The researcher asks, “What is this experience like?’, ‘What does this experience mean?’ or ‘How does this ‘lived experience’ present itself to the participant?’

- Attempts to set aside biases and preconceived assumptions about human experiences, feelings, and responses to a particular situation.

- Experience may involve perception, thought, memory, imagination, and emotion or feeling.

- Usually (but not always) involves a small sample of participants (approx. 10-15).

- Analysis includes an attempt to identify themes or, if possible, make generalizations in relation to how a particular phenomenon is perceived or experienced.

Methods used include:

- participant observation

- in-depth interviews with open-ended questions

- conversations and focus workshops.

Researchers may also examine written records of experiences such as diaries, journals, art, poetry and music.

Descriptive phenomenology is a powerful way to understand subjective experience and to gain insights around people’s actions and motivations, cutting through long-held assumptions and challenging conventional wisdom. It may contribute to the development of new theories, changes in policies, or changes in responses.

Limitations

- Does not suit all health research questions. For example, an evaluation of a health service may be better carried out by means of a descriptive qualitative design, where highly structured questions aim to garner participant’s views, rather than their lived experience.

- Participants may not be able to express themselves articulately enough due to language barriers, cognition, age, or other factors.

- Gathering data and data analysis may be time consuming and laborious.

- Results require interpretation without researcher bias.

- Does not produce easily generalisable data.

Example questions

- How do cancer patients cope with a terminal diagnosis?

- What is it like to survive a plane crash?

- What are the experiences of long-term carers of family members with a serious illness or disability?

- What is it like to be trapped in a natural disaster, such as a flood or earthquake?

Example studies

- The patient-body relationship and the "lived experience" of a facial burn injury: a phenomenological inquiry of early psychosocial adjustment . Individual interviews were carried out for this study.

- The use of group descriptive phenomenology within a mixed methods study to understand the experience of music therapy for women with breast cancer . Example of a study in which focus group interviews were carried out.

- Understanding the experience of midlife women taking part in a work-life balance career coaching programme: An interpretative phenomenological analysis . Example of a study using action research.

- Holloway, I. & Galvin, K. (2017). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (Fourth ed.): John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Rodriguez, A., & Smith, J. (2018). Phenomenology as a healthcare research method . Journal of Evidence Based Nursing , 21(4), 96-98. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102990

- << Previous: Methodologies

- Next: Grounded theory >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6: Phenomenology

Darshini Ayton

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify the key terms, concepts and approaches used in phenomenology.

- Explain the data collection methods and analysis for phenomenology.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of phenomenological research.

What is phenomenology ?

The key concept in phenomenological studies is the individual .

Phenomenology is a method and a philosophical approach, influenced by different paradigms and disciplines. 1

Phenomenology is the everyday world from the viewpoint of the person. In this viewpoint, the emphasis is on how the individual constructs their lifeworld and seeks to understand the ‘taken for granted-ness’ of life and experiences. 2,3 Phenomenology is a practice that seeks to understand, describe and interpret human behaviour and the meaning individuals make of their experiences; it focuses on what was experienced and how it was experienced. 4 Phenomenology deals with perceptions or meanings, attitudes and beliefs, as well as feelings and emotions. The emphasis is on the lived experience and the sense an individual makes of those experiences. Since the primary source of data is the experience of the individual being studied, in-depth interviews are the most common means of data collection (see Chapter 13). Depending on the aim and research questions of the study, the method of analysis is either thematic or interpretive phenomenological analysis (Section 4).

Types of phenomenology

Descriptive phenomenology (also known as ‘transcendental phenomenology’) was founded by Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). It focuses on phenomena as perceived by the individual. 4 When reflecting on the recent phenomenon of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear that there is a collective experience of the pandemic and an individual experience, in which each person’s experience is influenced by their life circumstances, such as their living situation, employment, education, prior experiences with infectious diseases and health status. In addition, an individual’s life circumstances, personality, coping skills, culture, family of origin, where they live in the world and the politics of their society also influence their experience of the pandemic. Hence, the objectiveness of the pandemic is intertwined with the subjectiveness of the individual living in the pandemic.

Husserl states that descriptive phenomenological inquiry should be free of assumption and theory, to enable phenomenological reduction (or phenomenological intuiting). 1 Phenomenological reduction means putting aside all judgements or beliefs about the external world and taking nothing for granted in everyday reality. 5 This concept gave rise to a practice called ‘bracketing’ — a method of acknowledging the researcher’s preconceptions, assumptions, experiences and ‘knowing’ of a phenomenon. Bracketing is an attempt by the researcher to encounter the phenomenon in as ‘free and as unprejudiced way as possible so that it can be precisely described and understood’. 1(p132) While there is not much guidance on how to bracket, the advice provided to researchers is to record in detail the process undertaken, to provide transparency for others. Bracketing starts with reflection: a helpful practice is for the researcher to ask the following questions and write their answers as they occur, without overthinking their responses (see Box 1). This is a practice that ideally should be done multiple times during the research process: at the conception of the research idea and during design, data collection, analysis and reporting.

Box 6.1 Example s of bracketing prompts

How does my education, family background (culture), religion, politics and job relate to this topic or phenomenon?

What is my previous experience of this topic or phenomenon? Do I have negative and/or positive reactions to this topic or phenomenon? What has led to this reaction?

What have I read or understood about this topic or phenomenon?

What are my beliefs and attitudes about this topic or phenomenon? What assumptions am I making?

Interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology was founded by Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), a junior colleague of Husserl. It focuses on the nature of being and the relationship between an individual and their lifeworld. While Heidegger’s initial work and thinking aligned with Husserl’s, he later challenged several elements of descriptive phenomenology, leading to a philosophical separation in ideas. Husserl’s descriptive phenomenology takes an epistemological (knowledge) focus while Heidegger’s interest was in ontology 4 (the nature of reality), with the key phrase ‘being-in-the-world’ referencing how humans exist, act or participate in the world. 1 In descriptive phenomenology, the practice of bracketing is endorsed and experience is stripped from context to examine and understand it.

Interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology embraces the intertwining of an individual’s subjective experience with their social, cultural and political contexts, regardless of whether they are conscious of this influence. 4 Interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology moves beyond description to the interpretation of the phenomenon and the study of meanings through the lifeworld of the individual. While the researcher’s knowledge, experience, assumptions and beliefs are valued, they do need to be acknowledged as part of the process of analysis. 4

For example, Singh and colleagues wanted to understand the experiences of managers involved in the implementation of quality improvement projects in an assisted living facility, and thus they conducted a hermeneutic phenomenology study. 6 The objective was to ‘understand how managers define the quality of patient care and administrative processes’, alongside an exploration of the participant’s perspectives of leadership and challenges to the implementation of quality improvement strategies. (p3) Semi-structured interviews (60–75 minutes in duration) were conducted with six managers and data was analysed using inductive thematic techniques.

New phenomenology , or American phenomenology , has initiated a transition in the focus of phenomenology from the nature and understanding of the phenomenon to the lived experience of individuals experiencing the phenomenon. This transition may seem subtle but fundamentally is related to a shift away from the philosophical approaches of Husserl and Heidegger to an applied approach to research. 1 New phenomenology does not undergo the phenomenological reductionist approach outlined by Husserl to examine and understand the essence of the phenomenon. Dowling 1 emphasises that this phenomenological reduction, which leads to an attempt to disengage the researcher from the participant, is not desired or practical in applied research such as in nursing studies. Hence, new phenomenology is aligned with interpretive phenomenology, embracing the intersubjectivity (shared subjective experiences between two or more people) of the research approach. 1

Another feature of new phenomenology is the positioning of culture in the analysis of an individual’s experience. This is not the case for the traditional phenomenological approaches 1 ; hence, philosophical approaches by European philosophers Husserl and Heidegger can be used if the objective is to explore or understand the phenomenon itself or the object of the participant’s experience. The methods of new phenomenology, or American phenomenology, should be applied if the researcher seeks to understand a person’s experience(s) of the phenomenon. 1

See Table 6.1. for two different examples of phenomenological research.

Advantages and disadvantages of phenomenological research

Phenomenology has many advantages, including that it can present authentic accounts of complex phenomena; it is a humanistic style of research that demonstrates respect for the whole individual; and the descriptions of experiences can tell an interesting story about the phenomenon and the individuals experiencing it. 7 Criticisms of phenomenology tend to focus on the individuality of the results, which makes them non-generalisable, considered too subjective and therefore invalid. However, the reason a researcher may choose a phenomenological approach is to understand the individual, subjective experiences of an individual; thus, as with many qualitative research designs, the findings will not be generalisable to a larger population. 7,8

Table 6.1. Examples of phenomenological studies

Phenomenology focuses on understanding a phenomenon from the perspective of individual experience (descriptive and interpretive phenomenology) or from the lived experience of the phenomenon by individuals (new phenomenology). This individualised focus lends itself to in-depth interviews and small scale research projects.

- Dowling M. From Husserl to van Manen. A review of different phenomenological approaches. Int J Nurs Stud . 2007;44(1):131-42. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.026

- Creswell J, Hanson W, Clark Plano V, Morales A. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol . 2007;35(2):236-264. doi:10.1177/0011000006287390

- Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals. 2nd ed. SAGE; 1995.

- Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ . 2019;8(2):90-97. doi:10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

- Merleau-Ponty M, Landes D, Carman T, Lefort C. Phenomenology of Perception . 1st ed. Routledge; 2011.

- Singh J, Wiese A, Sillerud B. Using phenomenological hermeneutics to understand the experiences of managers working with quality improvement strategies in an assisted living facility. Healthcare (Basel) . 2019;7(3):87. doi:10.3390/healthcare7030087

- Liamputtong P, Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus . Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Liamputtong P. Qualitative Research Methods . 5th ed. Oxford University Press; 2020.

- Abbaspour Z, Vasel G, Khojastehmehr R. Investigating the lived experiences of abused mothers: a phenomenological study. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences . 2021;10(2)2:108-114. doi:10.22062/JQR.2021.193653.0

- Engberink AO, Mailly M, Marco V, et al. A phenomenological study of nurses experience about their palliative approach and their use of mobile palliative care teams in medical and surgical care units in France. BMC Palliat Care . 2020;19:34. doi:10.1186/s12904-020-0536-0

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Darshini Ayton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Phenomenological Research: Methods And Examples

Ravi was a novice, finding it difficult to select the right research design for his study. He joined a program…

Ravi was a novice, finding it difficult to select the right research design for his study. He joined a program to improve his understanding of research. As a part of his assignment, he was asked to work with a phenomenological research design. To execute good practices in his work, Ravi studied examples of phenomenological research. This let him understand what approaches he needed and areas he could apply the phenomenological method.

What Is Phenomenological Research?

Phenomenological research method, examples of phenomenological research.

A qualitative research approach that helps in describing the lived experiences of an individual is known as phenomenological research. The phenomenological method focuses on studying the phenomena that have impacted an individual. This approach highlights the specifics and identifies a phenomenon as perceived by an individual in a situation. It can also be used to study the commonality in the behaviors of a group of people.

Phenomenological research has its roots in psychology, education and philosophy. Its aim is to extract the purest data that hasn’t been attained before. Sometimes researchers record personal notes about what they learn from the subjects. This adds to the credibility of data, allowing researchers to remove these influences to produce unbiased narratives. Through this method, researchers attempt to answer two major questions:

- What are the subject’s experiences related to the phenomenon?

- What factors have influenced the experience of the phenomenon?

A researcher may also use observations, art and documents to construct a universal meaning of experiences as they establish an understanding of the phenomenon. The richness of the data obtained in phenomenological research opens up opportunities for further inquiry.

Now that we know what is phenomenological research , let’s look at some methods and examples.

Phenomenological research can be based on single case studies or a pool of samples. Single case studies identify system failures and discrepancies. Data from multiple samples highlights many possible situations. In either case, these are the methods a researcher can use:

- The researcher can observe the subject or access written records, such as texts, journals, poetry, music or diaries

- They can conduct conversations and interviews with open-ended questions, which allow researchers to make subjects comfortable enough to open up

- Action research and focus workshops are great ways to put at ease candidates who have psychological barriers

To mine deep information, a researcher must show empathy and establish a friendly rapport with participants. These kinds of phenomenological research methods require researchers to focus on the subject and avoid getting influenced.

Phenomenological research is a way to understand individual situations in detail. The theories are developed transparently, with the evidence available for a reader to access. We can use this methodology in situations such as:

- The experiences of every war survivor or war veteran are unique. Research can illuminate their mental states and survival strategies in a new world.

- Losing family members to Covid-19 hasn’t been easy. A detailed study of survivors and people who’ve lost loved ones can help understand coping mechanisms and long-term traumas.

- What’s it like to be diagnosed with a terminal disease when a person becomes a parent? The conflict of birth and death can’t be generalized, but research can record emotions and experiences.

Phenomenological research is a powerful way to understand personal experiences. It provides insights into individual actions and motivations by examining long-held assumptions. New theories, policies and responses can be developed on this basis. But, the phenomenological research design will be ineffective if subjects are unable to communicate due to language, age, cognition or other barriers. Managers must be alert to such limitations and sharp to interpret results without bias.

Harappa’s Thinking Critically program prepares professionals to think like leaders. Make decisions after careful consideration, engage with opposing views and weigh every possible outcome. Our stellar faculty will help you learn how to back the right strategies. Get the techniques and tools to build an analytical mindset. Effective thinking will improve communication. This in turn can break down barriers and open new avenues for success. Take a step forward with Harappa today!

Explore Harappa Diaries to learn more about topics such as What Are The Objectives Of Research , Fallacy Meaning , Kolb Learning Styles and How to Learn Unlearn And Relearn to upgrade your knowledge and skills.

Reskilling Programs

L&D leaders need to look for reskilling programs that meet organizational goals and employee aspirations. The first step to doing this is to understand the skills gaps and identify what’s necessary. An effective reskilling program will be one that is scalable and measurable. Companies need to understand their immediate goals and prepare for future requirements when considering which employees to reskill.

Are you still uncertain about the kind of reskilling program you should opt for? Speak to our expert to understand what will work best for your organization and employees.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Phenomenological Qualitative Methods Applied to the Analysis of Cross-Cultural Experience in Novel Educational Social Contexts

Ahmed ali alhazmi.

1 Education Department, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Angelica Kaufmann

2 Cognition in Action Unit, PhiLab, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

The qualitative method of phenomenology provides a theoretical tool for educational research as it allows researchers to engage in flexible activities that can describe and help to understand complex phenomena, such as various aspects of human social experience. This article explains how to apply the framework of phenomenological qualitative analysis to educational research. The discussion within this article is relevant to those researchers interested in doing cross-cultural qualitative research and in adapting phenomenological investigations to understand students’ cross-cultural lived experiences in different social educational contexts.

Introduction: The Qualitative Method in Educational Research

Many scholars in phenomenology hold the view that human beings extract meaning from the world through personal experience ( Husserl, 1931 ; Hycner, 1985 ; Koopmans, 2015 ; Hourigan and Edgar, 2020 ; Gasparyan, 2021 ). Investigating the experience of individuals is a highly complex phenomenon ( Jarvis, 1987 ): annotating and clarifying human experience can be a challenging task not only because of the complexity of human nature, but also because an individual’s experience is a multidimensional phenomenon, that is, psychologically oriented, culturally driven, and socially structured. Hence, much uncertainty and ambiguity are surrounding the description and exploration of an individual’s experience. Such uncertainty is due to the multidimensional aspects that constitute and form an individual’s experiences, including ongoing and “mediated” behaviour ( Karpov and Haywood, 1998 ), feelings, and cognition. In all these respects, the complexity of experience becomes especially evident in certain investigative contexts such as the one we decided to explore, that is the study of the cross-cultural interactions of individuals who experience a transition from their own cultural and educational social context to a different one. In this article, it is argued that a hybrid phenomenological qualitative approach that, as shall be illustrated, brings together aspects of descriptive phenomenology, and aspects of interpretative phenomenology ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Lopez and Willis, 2004 ), could assist researchers in navigating through the complexity of cross-cultural experiences encountered by individuals in novel social educational contexts. Descriptive phenomenology was derived mainly from the philosophical work of Husserl and particularly from the idea of transcendental phenomenology ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Lopez and Willis, 2004 ; Giorgi, 2010 ). In contrast, an interpretive phenomenological methodology was derived from the works of scholars like Merleau-Ponty (1962) , Gadamer (2000) , and Gadamer and Linge (2008) . These two approaches overlap in the research methods and activities and are deployed to assist the research by promoting engagement with responsive and improvised activities rather than with mechanical procedures. The general qualitative methodology of social science research has shaped phenomenology as a methodological approach just as reliable as quantitative and experimental methods, as recently discussed by Høffding et al. (2022) , who stressed the advantages of phenomenology in qualitative research (see also Zahavi, 2019a , b ). Since we are interested in cross-cultural experiences, in the past, for example, we used such phenomenological qualitative type of investigation to find out what it is like for Saudi international students to transition from a gender-segregated society to a mixed-gender environment while studying and living as international students ( Alhazmi and Nyland, 2013 , 2015 ). We were interested in further understanding the phenomenon of transitioning itself rather than collecting students’ opinions and perspectives about the experience of transitioning. The investigation was conducted to capture and describe essential aspects of the participants’ experience, to understand the experience encountered by students in their novel social educational context. Besides this specific study case, the same hybrid methodology, as shall be suggested, may be applied to the study of similar types of social environments and groups. We refer to our past work on cross-cultural transitioning experience to help the reader translate how the phenomenological qualitative methodology can be applied in relatable scenarios in educational research.

As Giorgi (1985) , Van Manen (1990) , Moustakas (1994) , and other phenomenologists have stated, interviewing individuals who experience specific phenomena is the foundation source that phenomenological investigation relies on to understand the phenomenon. Accordingly, aspects that are core to the interviews are the following: (1) general attributes of the conducted interviews, (2) criteria of selection for potential participants, (3) ethical considerations of dealing with human participants, and (4) the interviewing procedures and some examples (these will be presented in section “Practising Phenomenology: Methods and Activities”).

To design a phenomenologically based qualitative investigation, we suggest considering three aspects: (1) the aim of the investigation; (2) the philosophical assumptions about the sought knowledge; and (3) the investigative strategies. These three aspects of the investigation shall be approached while keeping in mind the two following rationals: (1) looking for essence and (2) flexible methods and activities.

- The researcher’s aim is that of identifying the essential and invariant structure (i.e., the essence ) of the lived experience as this is described by the participants ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Crotty, 1998 ; Cresswell, 2008 ). This allows the researcher to ‘return to the concrete aspect of the experience’ ( Moustakas, 1994 , p. 26) by offering a systematic attempt to present the experience as it appears in consciousness ( Polkinghorne, 1989 ) and to focus on the importance of the individuals and their respective views about the lived experience ( Lodico et al., 2006 ). It is essential to keep this aim (i.e., identifying the essence of lived experience ) in mind when conducting a phenomenological qualitative investigation as this is the core aim of phenomenology. According to Finlay (2006 , 2008 ), exploring and understanding the essential structure and themes of the lived experience encountered by individuals is critical. Researchers adopting these perspectives ‘borrow’ the participants’ experience and their reflections on their experience to get a deeper understanding and to grasp the deeper meaning of the investigated experience ( Van Manen, 1990 , p. 62). This is what Finlay (2006 , 2008 ) calls ‘dancing’ between two approaches, and it is also the approach that we endorse. As pointed out by Høffding and Martiny (2016) , in this explorative process the interviewer needs to understand the relation between the interviewee’s experience and their description of it, since the interview constitutes a second person perspective in which one directly encounters another subjectivity and shall not elicit closed answers such as “yes” or “no” (see section “Attributes of the Conducted Interviews”). This feature is useful when exploring an experience that has not been sufficiently explored and discussed.

- The suggested phenomenological qualitative approach offers a strategy that ‘sharpen the level on ongoing practices in phenomenologically inspired qualitative research’ ( Giorgi, 2006a , p. 306). Methods and activities for data collection are flexible, and the analysis is designed to be aligned with the theoretical and philosophical assumptions underlying qualitative research. The present strategy allows a researcher to dialogue with both the participants and the data to produce a multi-layered description of the experience. This feature is academically important in terms of conducting a rigorous qualitative study that provides trustworthy knowledge ( Crotty, 1998 ; Denzin and Lincoln, 2003 ; Creswell, 2007 , 2009 ; Bryman, 2008 ).

The three core aspects of the investigation (1) the aim of the investigation; (2) the philosophical assumptions about the sought knowledge; and (3) the investigative strategies, informed by these two rationals , are essential to developing a phenomenologically oriented qualitative method to examine the lived experience and for identifying its essence.

Aim and Method

Thinking about the actual object of our investigation, that is, the lived experience of individuals is an essential aspect of phenomenological qualitative research. The researchers need to identify their aim very carefully by focusing on the lived experience of the subject being interviewed and on the structure of such experience rather than on the opinion of the participants about the experience.

In our previous studies, we were interested in describing the cross-cultural experience lived by Saudi students transitioning from their home country to another. Call the experience of transitioning ‘experience X’ and call Saudi students ‘group Y’. The research sought to examine the major question and the supplementary questions around which the study revolved, which was the following: “ What does the experience X look like for the individuals belonging to group Y? ”

As the question is broad in scope and quite complex, we decided to address it from a particular angle to grasp the essence of the students’ experience rather than providing a superficial description or a personal reflection of the experience. The efforts were directed to identify the most prominent overt display of the students’ experience; the focus was on investigating the most invariant and essential aspect of their experience. From this viewpoint, the research was directed to the quest of ‘what’ individuals encounter and ‘how’ they encounter it. This aim is characterised by the research design as exploratory (e.g., Blumer, 1986 ; Stebbins, 2001 ; Ritchie and Lewis, 2003 ). Exploratory research design allows researchers to “taste” and experience social phenomena and provides a journey of discovery that consists of adventure ( Willig, 2008 ) and surprise. The researcher, guided by the research inquiry, may arrive to discover an unanticipated phenomenon.

In particular, the study of cross-cultural experience involves two aspects: first is what we can call a “transitioning experience” between two cultures. The second is the potential impact that “transitioning experience” has upon the identity of those individuals who lived the experience. The conceptualisation of the phenomenon (i.e., cross-cultural experience) must be addressed, and the theoretical perspective informing its conceptualisation should be considered while developing such a phenomenological approach.

Two theoretical perspectives can allow understanding the phenomenon of cross-cultural transition: the first one is the sociocultural theory, which has been developed from Vygotsky’s works (e.g., Vygotsky, 1978 ; Doelling and Goldschmidt, 1981 ; Cole, 1995 ; Wertsch et al., 1995 ); and the second one is symbolic interactionism theory, which draws on the works of Mead, Blumer, and others (e.g., Kuhn, 1964 ; Mead, 1967 ; Blumer, 1986 ; Denzin, 1992 ; Clammer et al., 2004 ; Urrieta, 2007 ). These two perspectives informed the conceptualisation of the research phenomenon and how the phenomenon has been approached methodologically. For what concerns Vygotsky and neo-Vygotskian authors (and their sociocultural perspectives), they facilitate our understanding of the phenomenon of cross-cultural transition and its investigation. For example, Vygotsky and neo-Vygotskian authors conceptualise the individual ability to adjust to the new culture. The assumption that underlies the investigation is that individuals can acquire new cognitive developmental patterns of thought employing what these authors call “mediational assistance of tools, signs, and other cultures” ( Kozulin, 2018 ).

For what concerns instead, the symbolic interactionism approach, this latter allows researchers to understand cross-cultural experienced phenomena by taking into consideration the role of symbolic meanings in forming individuals’ experience. The core assumption developed from this perspective is that symbolic meanings are developed, while individuals acquire their understanding of both their internal and external world.

To analyse cultural identity and this transitioning experience, another relevant aspect to consider is that symbolic interactionists assume that the definition of individual self and identity are both constructed in and played out through interaction with the environment and the other selves surrounding us. As stated by Hollander et al. (2011) , the most basic requisite for symbolic interaction is the existence of social selves who come together to share information, emotions, and goods—the full range of human activities. The conceptions that people have of themselves, and others shape how they present themselves. In turn, how they present themselves allows others to infer what actors privately think of themselves and others (p. 123). Another aspect to be noted is that in the context of cross-cultural transitioning, cultural identity reflects how individuals think and feel about belonging to their culture and to the larger society from which they come from; it is in the essence of their experiences, the sense of belonging to, or attachment with, either or both cultural groupings. To fully appreciate this, we need to “borrow” from different authors’ arguments, ideas, and theoretical perspectives and adopt the hybrid perspective that we mentioned.

With this in mind, we present an overview of our research aims and the attributes that they involve: exploration and philosophical assumptions about sought knowledge.

Exploration

The study process is not a recipe to follow but rather a journey to take, and as Willig (2008 , p. 2) pointed out, the concept of research ‘has moved from a mechanical (how-to-apply-appropriate-techniques-to-the-subject-matter) to a creative (how-can-I-find-out?) mode’.

A study should be designed to maintain the subjective approach of the researcher towards the exploration of the phenomenon being investigated, as well as to appreciate the inter-subjective nature of the approach involved in the investigation of the phenomenon itself. A phenomenological qualitative method allows to track empathy and recognition of both the researcher’s and the participant’s subjectivity in relation to the phenomenon being explored.

The design is aimed to provide the researcher and the audience, with an opportunity to test and experience the phenomenon through descriptions of the essence of the experience. By concentrating on exploration as an essential aim, we evoke flexibility—the type of flexibility that allows researchers to shift between lines of inquiry and move from one activity to another to uncover the structure of the experience. The direction and proposal concerning the activities should be open enough to accommodate the complexity and ambiguity that surrounds any examined phenomenon. Flexibility consists of merging the exploratory research with phenomenological and qualitative practices.

Philosophical Assumptions About Sought Knowledge

We consider ontological assumptions, that is, specific beliefs about some aspect of reality, and epistemological assumptions, that is, specific beliefs about some aspect of knowledge, that constitutes the phenomenon being the object of the investigation. Ontological and epistemological assumptions are considered an essential part of the research design. Therefore, researchers should identify these assumptions while engaging with the research process, as they will play a significant role in framing the research questions and justifying the research methodology, on the one hand, and the methods and activities, on the other hand ( Guba, 1990 ; Guba and Lincoln, 1994 ; Crotty, 1998 ; Denzin and Lincoln, 2003 ; Creswell, 2009 ; Høffding and Martiny, 2016 ; Martiny et al., 2021 ; Høffding et al., 2022 ).

Ontological Assumptions of the Phenomenological Investigation

Ontological assumptions are, here, propositions about the nature of social reality—that is, what exists in a social context ( Crotty, 1998 ; Blaikie, 2000 ). They relate to questions about reality: for example, what reality does exist? Does it have an external existence or is it internally constructed? However, not all phenomenologists consider ontological issues a real concern for designing and practising qualitative inquiry. That is because the ideas of phenomenology appeared as a reaction to the scientific positivist philosophical view of knowledge that dominated the philosophy of science. The phenomenological arguments, when they first appeared, were not concerned with ontological questions but rather they focussed on providing an alternative epistemological approach about how we can access knowledge that tends to be subjective and internally mediated. In other words, phenomenology, in its original form, is an attempt to explore the relationship between the knower and the known, which is an epistemological issue in philosophy rather than an ontological position. The main issue that concerns phenomenology, from these perspectives, is whether we assume or not that reality exists outside of human consciousness, i.e., before or independently of whether we think and reason about it. The epistemological question needs to be answered from both positions. The epistemological question is the real dilemma, and this concerns who is invested in the study of human consciousness. From this perspective, what is provided by human consciousness is our social reality, regardless of its internal existence, before we think about it. Knowledge is what research usually attempts to provide, therefore, it is what should concern a researcher. According to Spinelli (2005 , p. 15), “We have no idea whether ‘things in themselves’ truly exist. All we can say is that, as human beings, we are biased towards interpretations that are centred upon an object-based or ‘thing-based’ world”. In addition, ontological assumptions should be identified clearly before one practice phenomenological research. This perspective has relied on Heidegger’s thesis, which moved the discussions concerning phenomenology to the ontological level when he discussed the philosophy of existence and being from a phenomenological perspective ( Laverty, 2003 ; Tarozzi and Mortari, 2010 ).

The basic philosophical assumption underlying a phenomenological investigation is that truth can be found and can exist within the individual lived experience ( Spiegelberg and Schuhmann, 1982 ). Our study is based on arguments about the existence of a social world as internally mediated, which means that as humans, we must interact with this existence and construct meanings based on our culture and beliefs, historical development, and linguistic symbols.

In our work, we considered an internal reality that was ‘built up from the perception of social actors’ ( Bryman, 2008 , p. 18) and that was consistent with the subjective experiences of the external world ( Blanche and Durrheim, 1999 ). This assumption was supported by Dilthey (1979 , p. 161) who said that ‘undistorted reality only exists for us in the facts of consciousness given by inner experience (, and) the analysis of these facts is the core of the human studies’.

The meanings emerged from the research methods and activities, and from this systematic interaction with the participants in this research and from sharing their experience, for example, about our work on students transitioning from their home country to the novel educational social context. These meanings should be considered a central part of the social reality that a study should report upon. This assumption underlies and merges implicitly with the second level of assumptions, the epistemological assumptions of phenomenology.

Epistemological Assumptions of the Phenomenological Investigation

In qualitative research, the researcher can be considered the subject who acts to know the phenomenon that is considered as the object. Accordingly, the phenomenon of cross-cultural transition between two cultures can be seen as an (object) for the deed of the investigator who is seen as (subject). Identifying the relationship between subject and object is essential to developing a coherent and sound research design. The following epistemological considerations are relevant to the current investigation.

Intentional Knowledge

The first element is intentionality. This concept is at the heart of the phenomenological approach ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Crotty, 1998 ; Husserl and Hardy, 1999 ; Barnacle, 2001 ; Creswell et al., 2006 ; Tarozzi and Mortari, 2010 ). The original idea of phenomenology was built on this concept, introduced by Brentano (1874) . Intentionality is the direction of the content of a mental state. This is a pervasive feature of many different mental states: beliefs, hopes, judgements, intentions, love, and hatred. According to Brentano, intentionality is the mark of the mental: all and only mental states exhibit intentionality. To say that a mental state has intentionality is to say that it is a mental representation and that it has content. Husserl, who was Brentano’s student, assumed that this essential property of intentionality, the directedness of mental states onto something, is not contingent upon whether some real physical target exists independently of the intentional act itself. This is regardless of whether the appearance of the thing is an appearance of the thing itself or an appearance of a mediated thing. Such consciousness and knowledge of the thing amount to perspectival understanding. Therefore, a person’s understanding is an understanding of a thing or an aspect of a thing (object). The key epistemological assumption, derived from Husserl’s concept of intentionality, is that the phenomenon is not present to itself; it is present to a conscious subject ( Barnacle, 2001 ). Therefore, the knowledge that an individual hold about the phenomenon is mediated and one cannot have ‘pure or unmediated access’ which is other than a subjective mediated knowledge ( Barnacle, 2001 , p. 7). We have access only to the world that is presented to us. We have an intention to act, to know what is out there, and we only can have access to an intentional knowledge that the knower can consciously act towards ( Hughes and Sharrock, 1997 ). Therefore, the assumption held here is that knowledge is the outcome of a conscious act towards the thing to be known ( Hughes and Sharrock, 1997 ).

Subjectively Mediated Knowledge

The second epistemological assumption is related to the previous one, that of intentionality. It is that we either assume that the social world and a phenomenon do exist outside of our consciousness (see, for example, Vygotsky, 1962 ; Burge, 1979 , 1986 ), or that they do not, but we are able only, as individuals, to interact with it and produce meaning for it through a conscious act. Consciousness is the ‘medium of access to whatever is given to awareness’ ( Giorgi, 1997 , p. 236); therefore, epistemologically, only subjective knowledge can be known about the experienced world. This assumption leads to the next epistemological assumption held in this investigation, which claims that knowing other people’s experiences is the outcome of constructed and dialogical knowledge.

Constructed Dialogical Knowledge

By stating that the knowledge obtained from a phenomenological study is constructed dialogically, we differentiated between philosophical knowledge on life experiences, and the knowledge provided by certain research practices that explore and understand other people’s descriptions of their lived experience ( Giorgi, 2006a , b ; Finlay, 2008 ).

From a phenomenological perspective, we assume that knowledge provided through the research activities is a result of the researcher’s and participants’ interactions with the phenomenon that is subject to the investigation. The essence of the argument here is that the ‘experience’ is best known and represented only through dialogical interaction: an interpretative methodology that analyses (spoken or written) utterances or actions for their embedded communicative significance ( Linell, 2009 ). For what concerns us, interaction occurred between two inseparable domains: between the conscience of the researcher and the participants, and between these consciousnesses and the phenomenon explored. The qualitative methodology provided a direction for this study by way of navigating through the first domain, which was the interaction between researcher and participants. The first domain had two levels of interaction, with the first being the relationship between researcher, participants, and raw data as a dialogical relationship—a dialogical relationship in the sense that the researcher is actively engaged, through dialogue (in the form of spoken or written communicative utterances or actions), in constructing reasonable and sound meanings from the data collected from the participants ( Rossman and Rallis, 2003 ; Steentoft, 2005 ). The importance of such a dialogical relationship, in phenomenological research, is supported by Rossman and Rallis (2003) .

Phenomenological Qualitative Methods and Strategies

Two forms of phenomenological methodologies can be noticed in the literature of qualitative research: descriptive phenomenology and interpretive phenomenology ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Lopez and Willis, 2004 ). Descriptive phenomenology was derived mainly from the philosophical work of Husserl and particularly from the idea of transcendental phenomenology ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Lopez and Willis, 2004 ; Giorgi, 2010 ). In contrast, an interpretive phenomenological methodology was derived from the works of scholars like Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty (1962) , Gadamer (2000) , and Gadamer and Linge (2008) .

These approaches overlap in the research methods and activities and are used to assist the research by promoting engagement with responsive and improvised activities rather than with mechanical procedures. In fact, key principles of both descriptive and interpretative phenomenology are peoples’ subjective experiences and the meanings they ascribe to their lived world and how they relate to it ( Langdridge, 2007 ). No definite line distinguishes or separates these two approaches or attitudes. Deploying both binaries is what differentiates our phenomenological qualitative approach from other qualitative approaches in the field (see, for example, Finlay, 2008 ; Langdridge, 2008 ).

Descriptive Attitude

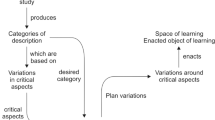

The descriptive attitude in ‘the sense of description versus explanation’ ( Langdridge, 2008 , p. 1132; Ihde, 2012 ) occurs where the emphasis is on describing what the researcher hears, reads, and perceives when entering the participants’ description of their experience. According to Ihde (2012 , p. 19) it is that attitude that consists in ‘describe phenomena phenomenologically, rather than explain them’. The whole phenomenological qualitative approach process is not description vs. interpretation, since interpretation is inevitably involved in describing and understanding the description of other people’s lived experiences ( Langdridge, 2008 ). As presented in Figure 1 , the descriptive attitude is served by the bracketing mode and by the reduction process in order to generate a textural description of the described lived experience ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Creswell, 2007 ).

The hybrid phenomenological qualitative method.

Bracketing refers to the efforts that should be made to be open to listening to and observing the described phenomenon with fresh eyes. It is an attempt to put aside any prejudgements regarding the phenomenon being investigated ( Salsberry, 1989 ; Moustakas, 1994 ; LeVasseur, 2003 ; also see a critical discussion in Zahavi, 2019a , 2020 , 2021 , and in Zahavi and Martiny, 2019 ). This mode also allows one to engage phenomenologically with the reduction process concerning the participants’ descriptions of their lived experiences. What the bracketing mode offers to a phenomenological qualitative study is: (1) temporary suspension of any prejudgements or assumptions related to the examined phenomenon that might have limited and restricted how the phenomenon appeared for the participants, while being aware that it is impossible to be completely free from any presuppositions; and (2) assistance in maintaining the involvement of previous experiences and perceptions about the phenomenon to recognise and realise what constitutes other aspects of the explored experience. According to Moustakas (1994 , p. 85) adopting a bracketing status allows that ‘whatever or whoever appears in our consciousness is approached with an openness’. The bracketing mode influences most stages of the research activities about the following aspects:

- – Forming descriptive research questions free from presuppositions to guide and direct the research enquiry, leading to the achievement of a study’s aims.

- – Responding to and engaging with previous works that were concerned with the same experience.

- – Conducting descriptive interviews that allow participants to share and describe their lived experiences.

- – Re-describing the described experience with careful treatment of the data included, maintaining the involvement of the researcher, and avoiding being selective or discriminating in the re-description of the experience.

Phenomenological Reduction

Phenomenological reduction is the process of re-describing and explicating meaning from the described experience ( Giorgi, 1985 , 2006a , b ; Moustakas, 1994 ; Crotty, 1998 ; Todres, 2005 ; Creswell, 2007 ; Finlay, 2008 ). Such strategies are used to underlie the data analysis process. For Moustakas (1994) and others (e.g., Todres, 2005 , 2007 ), the phenomenological reduction of human experience deals with two dimensions of the experience: texture and structure.

The texture is the ‘thickness’ of an experience ( Todres, 2007 , p. 47); it is a description of what the experience is like. Accordingly, the texture is an extensive description of what happened and how it appears to the researcher. The texture is the qualitative feature of the experience ( Moustakas, 1994 ; Creswell, 2007 ). The structure of the experience deals with emergent themes, and these describe the essential aspect of the experience. Such themes ‘can be grasped only through reflection’ on the textural descriptions of the participant’s experience ( Keen, 1975 , as cited in Moustakas, 1994 , p. 79).

Interpretive Attitude

The interpretive attitude is the second strategy to be used to approach the data. It is part of the phenomenological approach towards discovering the essential structure and meanings of the experience as described by the participants. The interpretive attitude is part of the methodological strategies used to search for the essence of the experience. This approach is used mainly in the final stages of the research activities when the data analysis is being conducted.

As Finlay (2008 , 2009 ) argued, ‘interpretation (in phenomenological practice) is not an additional procedure: It constitutes an inevitable and basic structure of our “being-in-the-world.” We experience a thing as something that has already been interpreted’ (p. 10). Therefore, to achieve a meaningful description and understanding of the essential aspect of an experience, we should move from the bracketing mode to an imaginative variation mode to reflect on the first step of the phenomenological reduction, which is a textural description.

Imaginative Variation Mode

In the phenomenological literature, imaginative variation is akin to the induction process in that it aims to extract themes and essential meanings that constitute the described experiences ( Klein and Westcott, 1994 ; Moustakas, 1994 ; Giorgi, 2006a , b , 2009 ; Creswell, 2009 ). It should be mentioned, however, that in the phenomenological practise, shifting from a descriptive to an interpretive attitude is ‘interpretive so far’ ( Klein and Westcott, 1994 , p. 141). It shall be noted that usually applying phenomenology within qualitative methods is seen as working with a version of ‘factual variation’ that, in comparison to ‘imaginative variation’, works with qualitative data (as described in Høffding and Martiny, 2016 ). However, since our approach is not purely fitting within the epistemological assumptions of positivism and neo-positivism, but rather it reflects the epistemological assumptions of the hermeneutical approach, we prefer to adopt ‘imaginative variation’, and remain consistent with our hybrid view that attempts to balance descriptive and interpretative methods of investigation. The imaginative variation mode enables a thematic and structural description of the ‘experience’ to be derived within the process of phenomenological reduction. This mode assists in focusing on the second aspect of the research, which requires an examination of how the experience might affect the cultural identity of the participants, that is, that part of their self-conception that is typically influenced by the cultural background of their country of origin, and that is responsible for shaping their social values and beliefs. This strategic mode can guide the researcher to shift from the descriptive to the interpretive attitude. According to Von Eckartsberg (1972 , p. 166) such a mode ‘constitutes the reflective work, looking back and thinking about this experience, discovering meaningful patterns and structures, universal features that are lived out concretely in a unique fashion’. This will be considered describing “past experience” as “mediated experience” in the final analysis. And mediation is an essential process that individuals engage with in relation to their experience. Reflecting on people’s personal experiences requires mutual and reciprocal respect between researcher and participants ( Klein and Westcott, 1994 ). This aspect allows the researcher to engage with the texture of the participant’s personal experience, to reflect on it, and to decide on possible meanings in relation to the whole context. It also allows the participants to evaluate the researcher’s reflection. This methodological mode can play a significant role in the process and activity of data analysis.

Practising Phenomenology: Methods and Activities

We provided an overview of the methodology that we endorse as hybrid since it embeds both descriptive and interpretive phenomenological attitudes. To implement and explicate this approach in the practice of the research, we can take suggestion of Moustakas (1994) about organising the phenomenological methods around three categories: (1) methods of preparation, (2) methods of collecting data and gaining descriptions about the phenomenon, and (3) methods of analysing and searching for the meaning. These categories are useful when it comes to conducting a phenomenological qualitative study because they allow for the reporting of the most significant methods and ensure that activities are conducted in a logical order.

Methods of Preparation, Activities, and Data Collection

If the nature of the study is emergent, like in most qualitative research (e.g., Creswell, 2009 ; Hays and Singh, 2011 ), the research purpose and questions are emergent too; they grew initially from personal experience and then emerge through the process of conceptualising a research topic around experience being investigated, for example, the experience of cross-cultural transition lived by individuals who move from their own cultural and educational context to a different one. In our past work, this was the transition of Saudi students, both males and females, from Saudi Arabia to Australia. These students experienced the transition from a gender-segregated, deeply religious cultural and educational social context to a different one, where gender-mixed interactions are not limited to members of one’s own family, such as in Saudi Arabia. In Australia, these students experienced life in a gender-mixed educational social context that is not built on religious pillars. The experience that we investigated consisted of: the cross-cultural transition to a different educational social context. As Giorgi (1985) , Van Manen (1990) , Moustakas (1994) , and other phenomenologists have stated, aspects that are core to the interviews are the following: (1) general attributes of the conducted interviews, (2) criteria of selection for potential participants, (3) ethical considerations of dealing with human participants, and (4) the interviewing procedures and some examples.

Attributes of the Conducted Interviews

The main attributes of the interviews may be summarised as follows:

As an interview is influenced by the mode of bracketing, prior to each of the interviews it is necessary to elicit the participant’s experience separately from any comparison with one’s own. The interviews are about what the participants want to say rather than what the main researcher wants them to say or what the main researcher expect them to say. It is important to point out that the interviews are designed in such a way to encourage discursive answers rather than affirmative or negative answers (as discussed in Høffding and Martiny, 2016 ). Engaging with the interviews has the scope of seeking new views and perspectives about the phenomenon that is being investigated, and not simply to confirm or disconfirm what is already known about that phenomenon.