5 Internal Communication Case Studies and Best Practices To Follow

Alex Cleary

Updated: May 13, 2024

Internal Communications

From employee engagement to workplace culture to change management, businesses often face similar challenges to each other even if those businesses are radically different. While the specifics of these challenges may differ, how other businesses solve these challenges can give you new insights into addressing your own.

We’re always interested in how our customers use ContactMonkey to solve their internal communications challenges, which is why we publish customer case studies. Learn how other businesses solve their communication challenges and get inspiration on ways you can improve your business by using an internal communications tool .

Real-time analytics that get it right

Discover where your employees are clicking, the best times to engage them, and which content resonates best.

What is an Internal Communication Case Study?

An internal communication case study examines how a company addressed a specific problem facing their organization, or achieved a specific goal. Communication is crucial for every business, and communication challenges can manifest in all kinds of situations.

An effective internal communication case study will clearly outline the problem, solution, and result of the business’ efforts to reach their goal. An internal communication case study should also outline best practices that were developed in this process, and how those best practices serve the business going forward.

Why are internal communication case studies important?

A good internal communication case study should not only explain the circumstances around a specific business’ problems and solution. It should also help others develop new ways to approach their own internal communication challenges , and shed light on common communication pitfalls that face a majority of businesses.

Whenever you’re facing a particular communication problem at your workplace, we recommend searching out a relevant internal communication case study about businesses facing similar issues. Even though the particulars may be different, it’s always important to see how internal communications problems are solved .

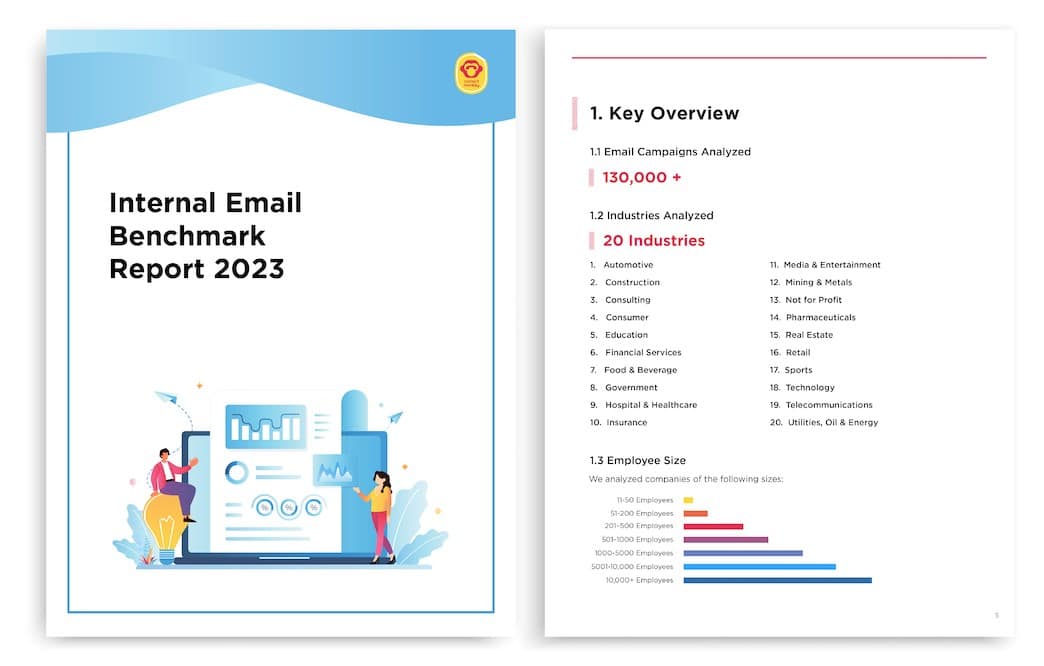

Featured Resource: Internal Email Benchmark Report 2023

How do your internal email performance metrics compare to 20 key industries?

5 Best Internal Communications Case Studies

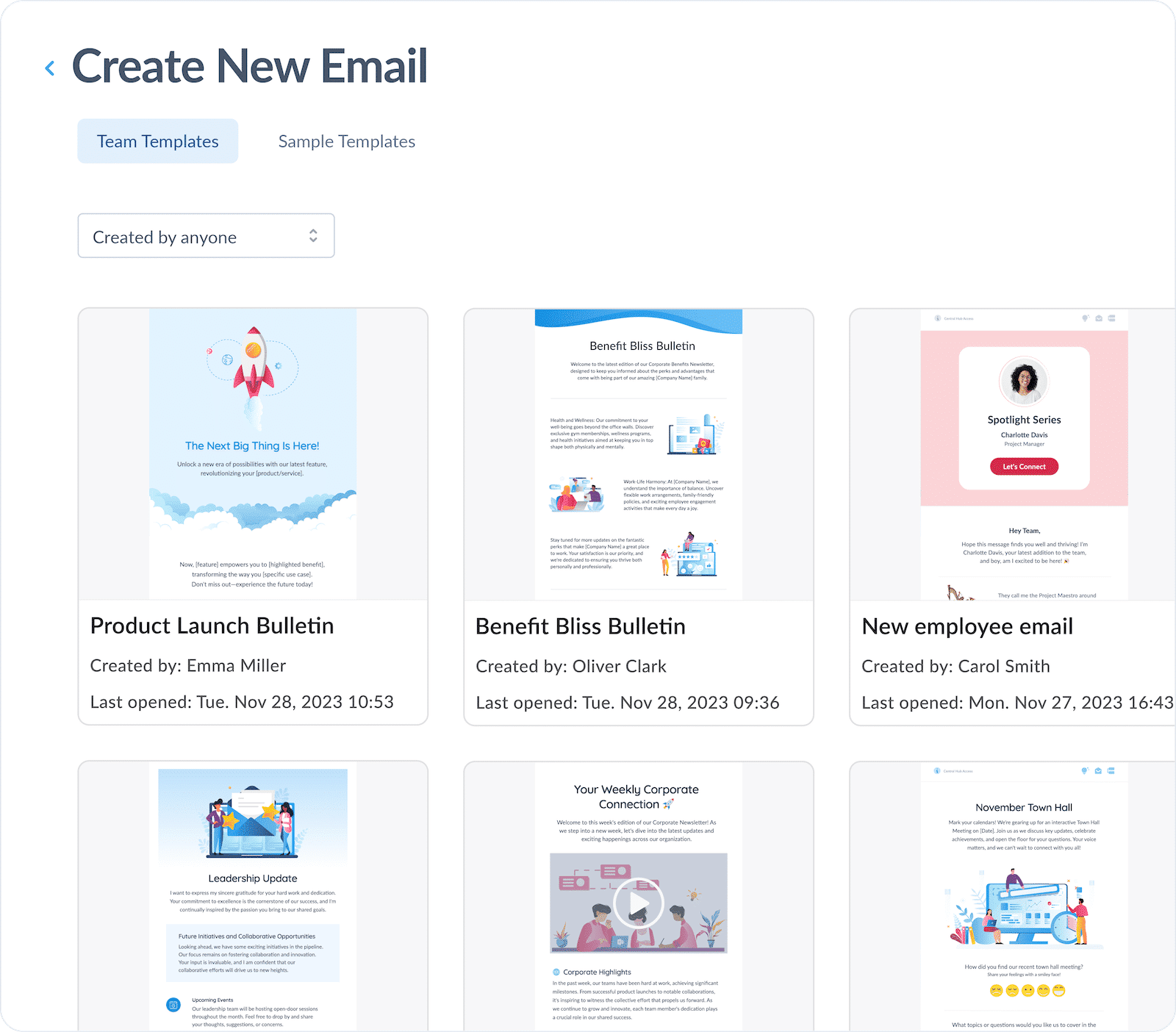

We put together this list of our favourite ContactMonkey case studies that best demonstrate the many problems our internal communications software can be used to solve. If you want to learn more about any of these customers and see other case studies, check out our Customers page .

Start your 14-day free trial of ContactMonkey

Captivating employee emails without IT approvals, new software, or learning curves.

1. Mettler Toledo Saves Days on their Internal Communications with ContactMonkey

When Kate Kraley began as Mettler Toledo’s Marketing Communications Specialist, she wanted to use internal communications to increase engagement and improve communication with employees.

But Mettler Toledo —a global manufacturer of precision instruments for various industries—had a confusing and ineffective array of internal communications channels . Here’s how Kate took charge of internal communications at Mettler Toledo with ContactMonkey.

Kate came to an internal communications department tasked with reaching employees through a number of channels. Email was the main focus of their approach, but this encompassed many forms of communication based on email like employee newsletters, eNews, and quarterly email updates.

Kate wanted to improve the quality of their internal communications. She used a variety of tools to create their newsletters, including using Mailchimp and online HTML template builder. But because Mailchimp is not for internal communications , Kate and her team found themselves spending over 8 hours a week building their internal communications:

“We faced challenges with Mailchimp. Since we had to leave Outlook to use Mailchimp, we found it was double the work to maintain distribution lists in both Outlook and Mailchimp. The HTML builder in Mailchimp was also difficult to use as it didn’t work well with older versions of Outlook, compromising the layout.”

Kate also needed a way to determine whether Mettler Toledo employees were actually reading her internal communications. She used Mailchimp to track open rate, but wanted more in-depth measures of engagement. That’s when she switched to ContactMonkey.

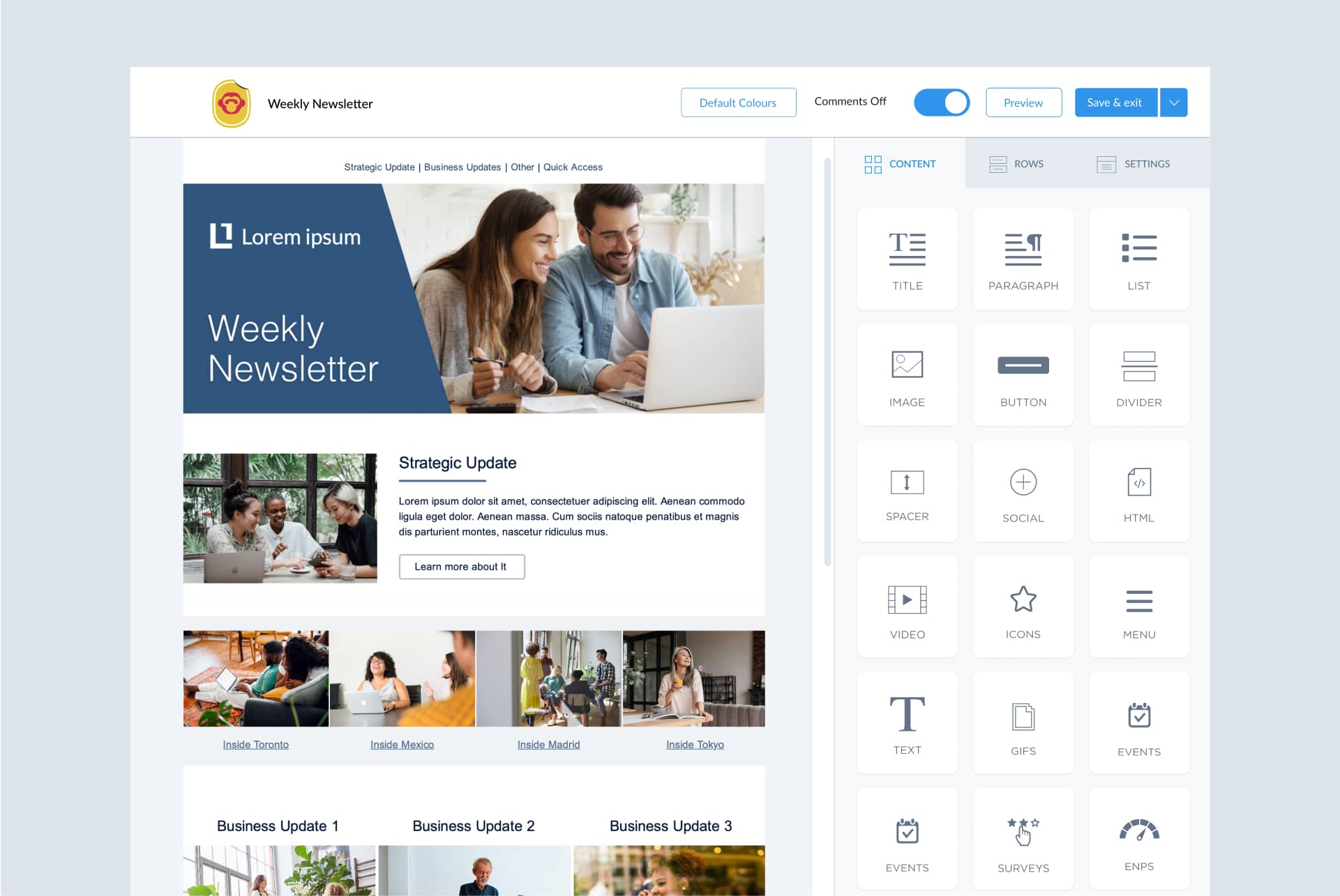

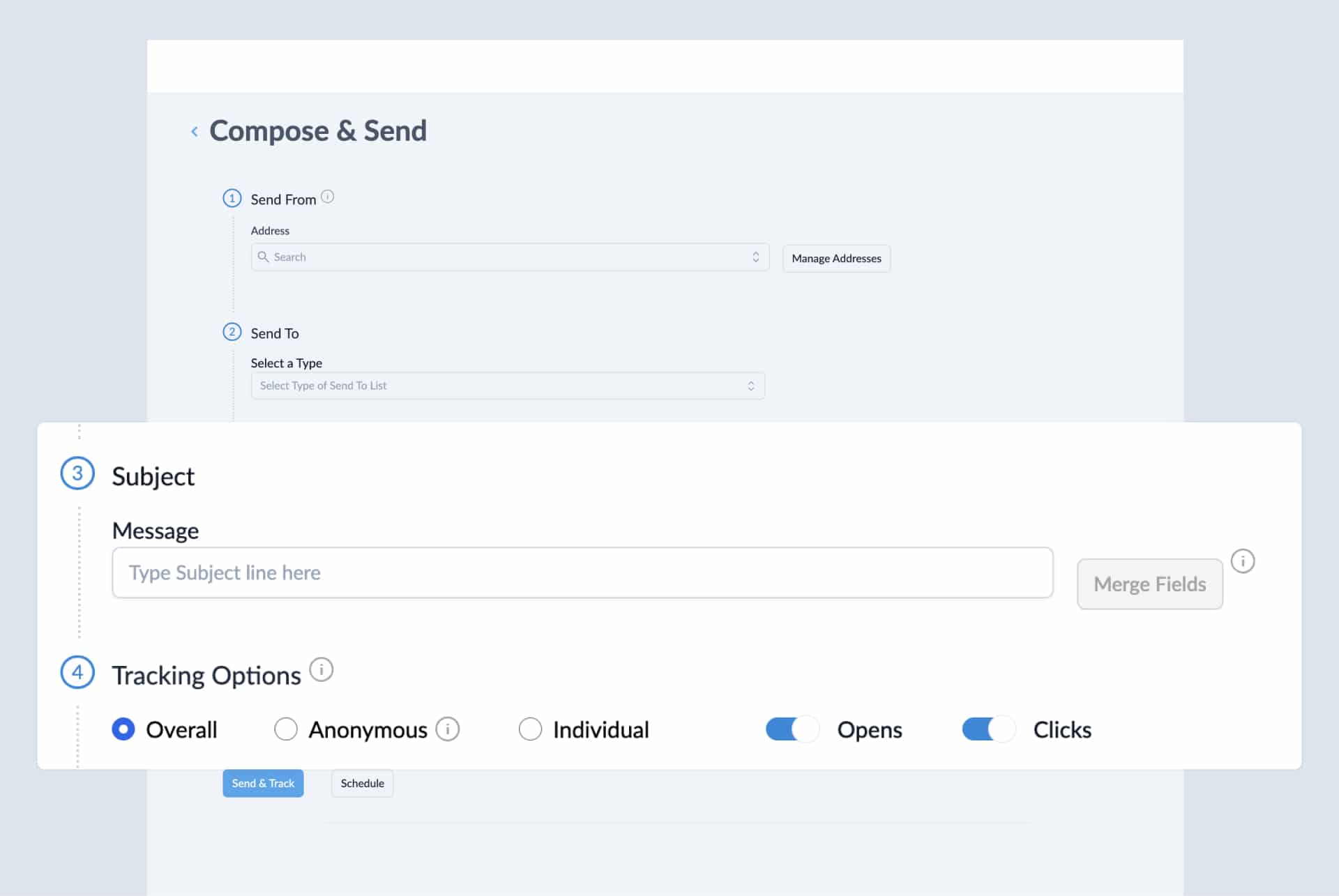

Kate found ContactMonkey via the IABC Hub in 2018, and began testing it out. ContactMonkey’s all-in-one internal communications software removed the need to switch from tool to tool. Using our email template builder , Kate now builds visually stunning email newsletters and templates without having to navigate away from Outlook:

She also now has access to her own analytics dashboard . Kate analyzes numerous email metrics like open rate, click-through rate, read time, opens by device and location, and more to see which communications are driving the most engagement. With this new centralized approach, Kate knew she had found the right solution:

“Once I started using ContactMonkey, I realized I was able to save 4 hours of work a week, which translated to 25 days saved per year! ContactMonkey has helped us understand what employees are interested in!”

2. BASF Manages Their Remote Workforce with ContactMonkey

Mark Kaplan is the Global Communications Manager at BASF’s Agricultural Group —a department of the German chemical company BASF SE. Because BASF has offices and production sites around the world, Mark coordinates with other internal communicators across the company to drive employee engagement.

With the success of any business comes new challenges, and BASF isn’t any different. While Mark knew he had to keep others informed of the latest news from the BASF Agricultural Group, he was aware employees would be receiving news from other parts of the company as well.

With many different departments sending their own internal communications, Mark faced a difficult task: keeping employees engaged while being careful not to overwhelm them with countless emails and updates.

“We try to be very strategic with what we’re sending out because people are already getting a lot.”

Not only did Mark have to find a solution that made his email communications more engaging, but he also had to prove the value of whatever solution he chose to management. How could Mark show that he was increasing employee engagement while avoiding tuning out from oversaturation?

Mark began using ContactMonkey to create better internal communications for BASF employees. Using our drag-and-drop email template builder, he designs emails that maximized communication and minimized distractions, keeping information to just what his recipients needed to know.

Mark uses ContactMonkey’s email template library to save time on his email design process. He also uses the easy drag-and-drop format of the email template builder to add multimedia into his email communications to save space and increase their effectiveness:

Mark uses the email analytics provided by ContactMonkey to determine the best times to send internal emails . Not only does email analytics help Mark increase engagement on his employee emails, but he now has hard data he can show management to prove the value of his internal communications.

“ContactMonkey has been great in that I can download a report, attach it to an email, and send it to our top leadership and say, ‘Oh, wow. 88% of the organization opened this in the last 24 hours, I think we should do more of this.’ It’s that little extra credibility.”

Best way to build engaging employee newsletters

3. alnylam drives remote employee engagement using contactmonkey.

Employee engagement is crucial for ongoing productivity and growth, and Alnylam’s Brendon Pires wanted to leverage their internal communications to increase engagement.

Brendon is an internal communications specialist at Alnylam —the world’s leading RNAi therapeutics company—and is tasked with keeping their 2000+ employees engaged and informed. But Brendon’s existing internal communications process was leading to issues all over the place.

Like many companies, Alnylam shifted to remote work when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Brendon knew that employees would be relying on his emails to stay up-to-date on the latest company news and announcements, but their existing internal communications tool wasn’t up to the task:

- Scheduled emails were prevented from being sent out.

- Email design was a chore with a difficult-to-use email builder.

- Intranet traffic was down and Brendon’s emails weren’t driving traffic to it.

- Email tracking was limited as many internal emails were being flagged by their tracking software’s firewall.

“We were having consistent issues and it had been going on for like a couple of months. It was one issue after the other, between emails not sending because they were getting caught in our firewall, and then tracking not being consistent. So at the end of the day it was kind of like that’s really important, you know? Obviously if I can’t send that email that’s a problem. So that’s what really drove us to look at other solutions like ContactMonkey”

Brendon and Alnylam use Outlook for their employee emails, so he began looking for alternatives to his current software. That’s when Brendon found ContactMonkey.

Right away Brendon had a much easier time creating internal emails using our email template builder. He can create stellar internal emails and email templates that drive more engagement.

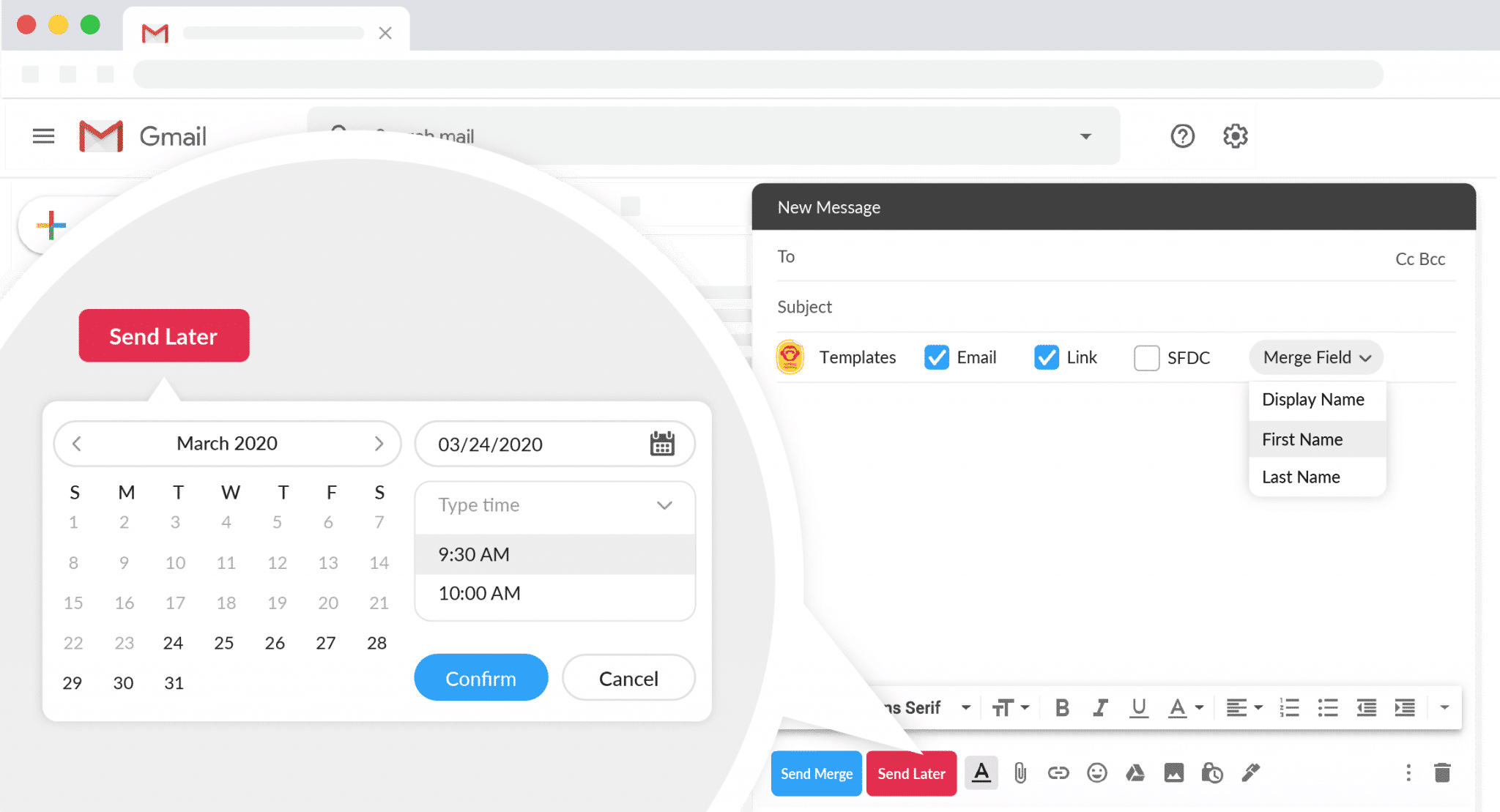

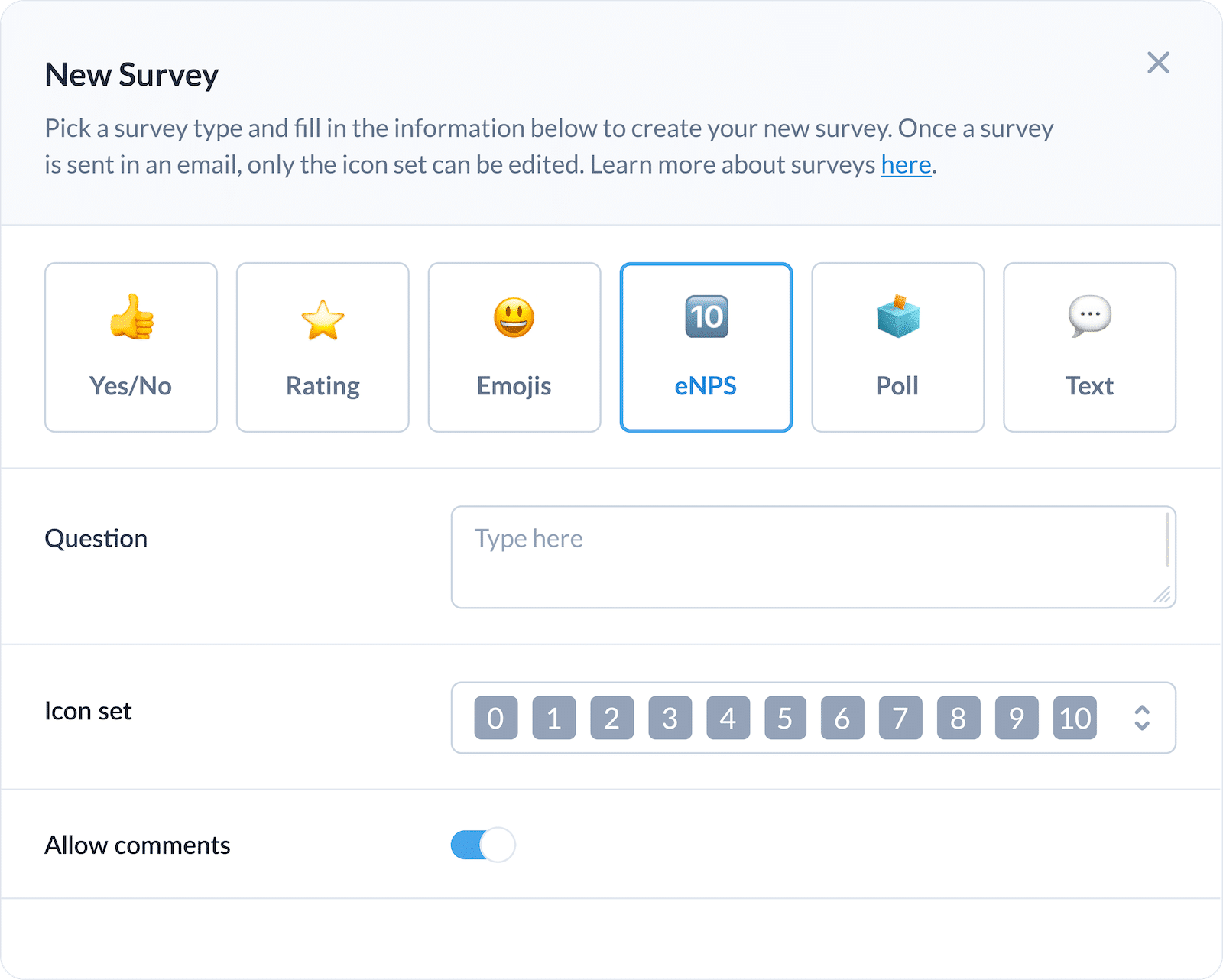

Brendon also uses ContactMonkey’s embedded star ratings to let Alnylam employees rate the emails they’re receiving. This helps Brendon and his team zero-in on their most engaging email content. He also uses our email analytics to measure engagement via open rate and click-through rate. He maximizes his results on these metrics by using ContactMonkey’s scheduled email sending:

Using ContactMonkey, Brendon was able to increase email engagement and drive traffic to Alnylam’s internal intranet . He now sends emails without worry of encountering sending errors that can hinder engagement—like Outlook not rendering HTML emails .

“ContactMonkey is really easy to use and allows me to create really nice content. There’s enough customization so we can do what we really want and have some creative freedom.”

4. Travel Counsellors Ltd. Stays Connected with Remote Employees Using ContactMonkey

In an economy deeply impacted by COVID-19, countless companies had to adapt to new challenges. As Community Manager at Travel Counsellors , Dave Purcell experienced firsthand the effects on morale and engagement his over 1,900 partners experienced as result of the quarantine and resulting societal changes.

Dave wanted to regularly check-in on Travel Counsellors franchisees’ wellbeing, and measure their engagement over time. But Dave’s current method of checking-in on an audience of over 1,900 was not up to the task.

Using their existing email software, Dave encountered all sorts of problems when trying to gauge wellness and drive email engagement. He and his team were unable to create personalized internal communications , as they were told it just wasn’t possible with their existing “solution”. They also experienced numerous tracking issues, as they were receiving tracking numbers that didn’t make any sense.

“The stats we had previously were unusable and that’s the easiest way I can put it. I was getting 200% open rates, which was just impossible.”

Realizing that email tracking and personalization were must-have features for him and his team, Dave sought a new email software that could deliver what he was looking for.

With the aim of sending personalized emails and tracking wellness in his organization, Dave was immediately impressed by ContactMonkey. “I stumbled across ContactMonkey, and everything just screamed: ‘This is the right platform for us’. It’s pretty fantastic.”

Dave uses ContactMonkey’s merge tags to create personalized subject lines and body copy based on the recipient:

He also began using emoji reactions on his weekly employee newsletters , using them as a pulse check survey for his audience.

“Mindset and wellbeing have always been a big part of what we do. It’s even more so now. Our franchisees craved that personal interaction. ‘Welcome to a Brand New Week’ checks in with them on a Monday, sees how they’re feeling with emoji reactions. And we do the same on a Friday.”

In addition to customization and surveys, Dave uses our email template builder’s custom employer branding options to save time on creating his email newsletters. All of this is driven by email analytics that help Dave and his team determine which content is generating the greatest engagement.

“Our commercial team is looking at what people are engaging with in terms of link clicks and what they’re not engaging with and changing our tactic depending on that. We also send an update from our CEO and we can now track this more accurately. We’re getting a 90% open rate within two days.”

5. Exemplis Boosts Internal Communications Engagement with ContactMonkey

When Corey Kachigan arrived at Exemplis as Engagement and Communications Lead, she knew she had her work cut out for her. Exemplis—the largest volume manufacturer of office seating in North America—was experiencing rapid growth but did not have any sort of internal communications strategy . Corey knew if she wanted to properly manage Exemplis’ ongoing growth, she’d need to make internal communications an indispensable part of the business.

Before Corey arrived, Exemplis’ existing internal communications consisted only of random announcements and update emails. They had no defined approach for sending internal communications, which lead to emails that can cause employees to tune out.

“Our receptionist would email: ‘Hey, whoever left their coffee mug in the sink, please clean it and take it back to your desk.’ And it’s like, okay, that just went to 200 people.”

Corey and her team knew they had to harness their email resources better, and wanted a way to measure what employees actually wanted to see.

“We need some metrics to gauge whether this is working or not. We’re rolling out all these things, but we can’t tell if employees are even clicking these emails. Our team is inundated with hundreds of emails a day. How do we know they are reading these and how do we know they find it valuable? We have no idea.”

They also wanted to use emails to align their ever-growing employee base with Exemplis’ core values and vision. Using Mailchimp—an external marketing email tool—resulted in more problems than solutions. Corey experienced issues with importing and tracking emails within Outlook. She realized that Mailchimp is not for internal communications , and set out to find a new solution to power her employee emails.

So Corey began searching for a new email software for internal communications. Creating a definite approach to internal communications was just one priority of hers; she also wanted to prove the value of internal communications to management using hard data.

What first stood out to Corey about ContactMonkey was the crisp layout and that it worked with Exemplis’ existing Outlook system. ContactMonkey uses your company’s existing email services, and this meant Corey would no longer encounter internal email problems caused by an external tool like Mailchimp.

Corey now uses email metrics and employee feedback to inform her internal communications approach. She features pulse surveys on her internal emails, and uses the results in combination with email metrics to pinpoint what Exemplis employees want to see.

With ContactMonkey’s email analytics, Corey can point to real engagement data to back up her internal communications objectives.

“The thing I love about ContactMonkey is that it allows us to communicate more consistently with our team, but also be able to have the data to back it up. When we used to send out newsletters, we didn’t really have a way to see who did or didn’t open it, who clicked what and they couldn’t interact with the communication besides reply to me, which was super cumbersome.”

Turn emails into engaging conversations

Gauge employee satisfaction with embedded pulse surveys in your emails.

Explore engagement features

Achieve Your Internal Communications Goals with ContactMonkey

Although internal communications is a common aspect of all businesses, everyone approaches it differently. Finding out the best email practices that work for your employees is a crucial step in the quest for increased engagement.

Read even one internal communication case study and you’ll see how ContactMonkey stands out among other internal communications tools. You can create, send, and track internal emails, and collect employee feedback and email metrics to develop innovative internal communication tactics . Whether you’re a seasoned internal communicator or new to the field, ContactMonkey can turn your internal communications into a powerful driver of productivity and growth at your organization.

Whip up emails your employees want to open

Want to see ContactMonkey in action? Book a free demo to see how our internal communications software can transform your employee emails:

Revamp your workplace comms with us, right from your inbox. Get started now!

Signup to our newsletter, The Ape Vine

Innovative internal comms content delivered weekly.

Email Template Builder

Outlook Sending

Email Analytics

Integrations

SMS Communications

Multi-Language Emails

Customer Stories

Free Templates

Attend Live Demo

Help Center

Partnerships

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A CASE STUDY OF WORKPLACE COMMUNICATION PROBLEM: STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION TO MAKE THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS MORE EFFECTIVE

Instituting effective organisational communication is imminent for organisations if they want to be relevant in the business world, going forward. Severally, breaches in communication ethics result in conflicts between top management and the labour force. This work examine such a case with a fictitious company name, in order to address the issue, by proffering a way forward using psychological theories and models.

Related Papers

Hesti Nur Syafa'ati

Geet Divekar

This journal was my submission for the course's final assignment. it is my reflection on ethics base on the case studies from Steve May's Case Studies in Organizational Communication. Ethics stand different for every individual and therefore, assuming that the thoughts in this journal are the only right ethical decisions would be wrong.

NHRD Network Journal

Prasenjit Bhattacharya

Journal of Marketing and Consumer Research

Ngorang Philipus

abhilasha ram

Excellent employee communication is must for any thriving organization. Effective internal communication is key to success of any organization. The need for communicating information to an organization's internal public — its employees — has become of utmost importance in the recent years. This research article studied internal / employee communication in terms of openness of communication and adequacy of information. The openness should be followed across the organization – between the employer and employee as well as amongst employees. Giving too little information as well as too much information to the concerned employee makes him/her confused; so, the importance of adequate information. The effectiveness of information studied on the basis of communication tools and practices used in the organization for the proper dissemination of communication.

Carl Harshman

Journal of Communication Management

Robert Beckett

RELATED PAPERS

Mirjana Turkalj

nterdisciplinary Studies of Arts and Humanities

Interdisciplinary Studies of Arts and Humanities (ISAH)

André Viana

Hte Maldives Journal of Research

Mario Castro Gama

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry

azhar ahmad

Emmanuel MUYOMBANO

Valdis Teraudkalns

Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry

Frederico Nave

Novi Widiastuti

Ultrasonics

Kadir Karaman

Proceedings of the 2006 Winter Simulation Conference

Maurício Vieira Kritz

Asian Journal of Probability and Statistics

Abubakar Yahaya

Nuclear Engineering and Design

Borut Mavko

Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Naresh Naik Ramavath

Tauhedi As'ad

ADI Journal on Recent Innovation

Vertika Agarwal

International Journal of Molecular Sciences

Giovanni Ricevuti

American journal of obstetrics and gynecology

Mary D'Alton

Annals of Geophysics

paolo Grigioni

CoreID Journal

Tia Rostiawati

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Effective Communication in the Workplace

Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/social-media-connections-networking-3846597/ is in the Public Domain at Pixabay.com. Retrieved 07.05.2022.

Effective workplace communication helps maintain the quality of working relationships and positively affects employees' well-being. This article discusses the benefits of practicing effective communication in the workplace and provides strategies for workers and organizational leaders to improve communication effectiveness.

Workplace Communication Matters

Effective workplace communication benefits employees' job satisfaction, organizational productivity, and customer service (Adu-Oppong & Agyin-Birikorang, 2014). We summarized Bosworth's (2016) and Adu-Oppong and Agyin-Birikorang's (2014) works below related to the benefits of practicing effective communication in the workplace.

- Reduces work-related conflicts

- Enhances interpersonal relationships

- Increases workers' performance and supervisors' expectations

- Increases workforce productivity through constructive feedback

- Increases employee engagement and job satisfaction

- Builds organizational loyalty and trust

- Reduces employees' turnover rate

- Facilitates the proper utilization of resources

- Uncovers new employees' talents

Strategies to Improve Communication Effectiveness

Effective communication is a two-way process that requires both sender and receiver efforts. We summarized research works and guidelines for good communication in the workplace proposed by Cheney (2011), Keyton (2011), Tourish (2010), and Lunenburg (2010).

Sender's strategies for communication planning

- Clearly define the idea of your message before sharing it.

- Identify the purpose of the message (obtain information, initiate action, or change another person's attitude)

- Be aware of the physical and emotional environment in which you communicate your message. Consider the tone you want to use, the configuration of the space, and the context.

- Consult with others when you do not feel confident or comfortable communicating your message.

- Be mindful of the primary content of the message.

- Follow-up previous communications to verify the information.

- Communicate on time, avoid postponing hard conversations, and be consistent.

- Be aware that your actions support your messages and be coherent in your verbal and behavioral communication style.

- Be a good listener, even when you are the primary sender.

Receiver's strategies during a conversation

- Show interest and attitude to listen.

- Listen more than talk.

- Pay attention to the talker and the message, avoiding distractions.

- Be patient and allow the talker time to transmit the message.

- Be respectful and avoid interrupting a talker.

- Hold your temper. An angry person takes the wrong meaning from words

- Go easy on argument and criticism.

- Engage in the conversation by asking questions. This attitude helps develop key points and keep a fluid conversation.

Effective communication practices are essential for any successful team and organization. Organizational communication helps to disseminate important information to employees and builds relationships of trust and commitment.

Key points to improve communication in the workplace

- Set clear goals and expectations

- Ask clarifying questions

- Schedule regular one-on-one meetings

- Praise in public, criticize in private

- Assume positive intent

- Repeat important messages

- Raise your words, not your voice

- Hold town hall meetings and cross-functional check-ins.

Adu-Oppong, A. A., & Agyin-Birikorang, E. (2014). Communication in the Workplace: Guidelines for improving effectiveness. Global journal of commerce & management perspective , 3 (5), 208–213.

Bosworth, P. (2021, May 19). The power of good communication in the workplace . Leadership Choice. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

Cheney, G. (2011). Organizational communication in an age of globalization: Issues, reflections, practices . Waveland Press.

Keyton, J. (2011). Communication and organizational culture: A key to understanding work experience . Sage.

Tourish, D. (2010). Auditing organizational communication: A handbook of research, theory, and practice . Routledge

Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). Communication: The process, barriers, and improving effectiveness. Schooling , 1 (1), 1-10.

- Adult leadership

- Volunteerism

- Volunteer management

You may also be interested in ...

Diferencias culturales en el ambiente laboral

Consejos Para Desarrollar una Filosofía Personal de Liderazgo

How to Become a Community Leader

Importance of Incorporating Local Culture into Community Development

Conducting Effective Surveys - 'Rules of the Road'

Conflict Styles, Outcomes, and Handling Strategies

Employee Disengagement and the Impact of Leadership

Dealing with Conflict

Developing Self-Leadership Competencies

Diversity Training in the Workplace

Personalize your experience with penn state extension and stay informed of the latest in agriculture..

- Product overview

- All features

- App integrations

CAPABILITIES

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields

- Status updates

- goal icon Goals and reporting

- Reporting dashboards

- workflow icon Workflows and automation

- portfolio icon Resource management

- Time tracking

- my-task icon Admin and security

- Admin console

- asana-intelligence icon Asana AI

- list icon Personal

- premium icon Starter

- briefcase icon Advanced

- Goal management

- Organizational planning

- Campaign management

- Creative production

- Content calendars

- Marketing strategic planning

- Resource planning

- Project intake

- Product launches

- Employee onboarding

- View all uses arrow-right icon

- Project plans

- Team goals & objectives

- Team continuity

- Meeting agenda

- View all templates arrow-right icon

- Work management resources Discover best practices, watch webinars, get insights

- What's new Learn about the latest and greatest from Asana

- Customer stories See how the world's best organizations drive work innovation with Asana

- Help Center Get lots of tips, tricks, and advice to get the most from Asana

- Asana Academy Sign up for interactive courses and webinars to learn Asana

- Developers Learn more about building apps on the Asana platform

- Community programs Connect with and learn from Asana customers around the world

- Events Find out about upcoming events near you

- Partners Learn more about our partner programs

- Support Need help? Contact the Asana support team

- Asana for nonprofits Get more information on our nonprofit discount program, and apply.

Featured Reads

- Collaboration |

- 12 tips for effective communication in ...

12 tips for effective communication in the workplace

Effective communication transcends simple information exchanges. Understanding the emotions and motives behind the given information is essential. In addition to successfully conveying messages, it's important to actively listen and fully understand the conversation, making the speaker feel heard and understood.

Today, we’re in almost constant contact with our coworkers. You might not put a lot of thought into saying “hi” to your coworker, grabbing virtual coffee with a remote team member, or sending a gif of a cat wearing pajamas to your team—and that’s ok. Even though you’re communicating at work, there’s a difference between these types of messages and communication in the workplace.

Communication in the workplace refers to the communication you do at work about work. Knowing when and how to effectively communicate at work can help you reduce miscommunication, increase team happiness, bolster collaboration, and foster trust. Teams that know how to communicate effectively about work are better prepared for difficult situations. But building good communication habits takes time and effort—and that’s where we come in. Here are 12 ways to take your workplace communication skills to the next level.

What is effective communication?

Effective communication is the exchange of ideas, thoughts, opinions, knowledge, and information so that the message is received and comprehended clearly and purposefully. When we communicate effectively, all stakeholders are fulfilled.

Developing effective communication skills requires a delicate balance of active listening, verbal communication, nonverbal cues, body language, and emotional intelligence to ensure messages are clearly transmitted and understood.

It's about more than just talking; effective communication involves listening skills and a deep understanding of interpersonal dynamics. Individuals can use these communication skills to bridge gaps, make informed decisions, and strengthen relationships.

What does “workplace communication” mean?

Communication in the workplace can happen face-to-face, in writing, over a video conferencing platform, on social media, or in a group meeting. It can also happen in real time or asynchronously , which happens when you’re communicating about work over email, with recorded video, or on a platform like a project management tool . Some examples of workplace communication include:

Team meetings

1:1 feedback sessions

Receiving information

Communicating about project status or progress

Collaboration on cross-functional tasks

Nonverbal communication

Collaboration Report: How the most effective teams in the world collaborate

Explore key traits that have made the most effective teams in the world successful: their strategies, techniques, and tips for working well together.

What makes communication effective?

Now that you know what type of communication can be included in workplace communication, how do you start getting better at it? There are a few key tenets of effective communication that you can use, no matter what type of communication it is. In particular, good communication:

Aims for clarity. Whether you’re sending a Slack message, drafting an email, or giving an off-the-cuff reply, aim to be clear and concise with your communication.

Seeks to solve conflicts, not create them. In the workplace, we're often involved in problem solving and collaborating on projects or tasks. Good communication in the workplace can involve bringing up blockers or providing feedback—but make sure the goal is to get to a better place than where you are now.

Goes both ways. Every instance of effective communication in the workplace represents an exchange of information—even when the information is communicated solely through nonverbal cues.

Benefits of effective communication in the workplace

Clear, effective workplace communication can:

Boost employee engagement and belonging

Improve interpersonal skills and emotional intelligence

Encourage team buy-in

Increase productivity

Build a healthy workplace and organizational culture

Reduce conflict

Increase retention

7 tips for more effective communication in the workplace

Effective communication in the workplace is all about where, how, and when you’re communicating. Try these seven tips to develop better communication skills.

1. Know where to communicate—and about what

Communication happens in many different forms—face-to-face, over email, via instant messages, and in work management platforms. To be most effective, make sure you’re following communication guidelines and messaging about the right things in the right places.

Sometimes, knowing where to communicate is half the battle. Your company may have different communication tools , which makes knowing which tool to use all the more important. Which tool is appropriate for your question or comment? Do you need to communicate in real time, or is it ok to send an asynchronous message? If you’re not sure, ask a team member or manager where you should be sending different types of messages. It is important for everyone to be on the same page. For example, at Asana, we use:

2. Build collaboration skills

Collaboration is the bedrock of effective teamwork. In order to build strong team collaboration skills , you need to practice open and honest communication. This doesn’t necessarily mean always agreeing on things—knowing how to disagree and work through those differences is a key part of collaboration, too.

Collaboration and communication skills are kind of a “chicken and egg” scenario. You can build good collaboration by communicating effectively, but knowing how to collaborate is a key component of strong communication. Essentially, this just means you’ll have to practice improving both collaboration and communication skills over time. As you improve team collaboration, you’ll get better at conveying information and opinions in a work environment—and as a result, that honest communication will make collaboration feel more effortless.

3. Talk face-to-face when you can

Perhaps the most tried-and-true way to avoid miscommunication is to talk face-to-face. If your team is virtual, speaking via video conferencing also works. Eye contact is particularly important if you know a conversation is going to be hard. Tone can be difficult to communicate through writing so ideally, you want your team member to be able to see your facial expressions and body language.

If your team is remote or distributed, communicating via a phone call instead of a video conference could work as well. Video conferencing fatigue is real, and it can make collaboration and communication particularly difficult for remote teams. Communicating over the phone reduces some of the visual strain, while still giving you the ability to hear your team member’s voice and tone.

4. Watch your body language and tone of voice

Communication isn’t just about what you say—it’s also about how you say it. Make sure you aren’t crossing your arms or coming off as curt. Oftentimes, your body language may have nothing to do with the current situation—maybe you’re tired or stressed about something in your personal life. But your team members, who might not have that context, could see your actions and assume you’re angry or upset about something. Particularly for hard conversations, try to relax your body language and facial expressions to avoid giving off any unintentional cues.

5. Prioritize two-way communication

Listening skills are just as important to communication in the workplace as talking. Part of being a collaborative team member is listening to other people’s ideas instead of just trying to put your own ideas out there.

There are two common types of listening : listening to reply and listening to understand. When you listen to reply, you’re focusing on what you’re going to say next, rather than what the other person is saying. With this type of listening, you risk missing key information or even repeating what the other person just said.

Instead, try active listening—that is, listen to what the other person has to say without thinking about how you’re going to reply. If you do think of something you want to say, jot it down so you can go back to listening to understand , instead of trying to remember the thing you want to say next.

6. Stick to facts, not stories

“Facts vs. stories” is a technique recommended by the co-founder of the Conscious Leadership Group, Diana Chapman. In this case, “facts” are things that have actually happened—things that everyone in the room would easily agree on. A “story,” on the other hand, is your interpretation of the situation.

For example, say your manager gives you live feedback during a small team meeting. That is a fact. You weren’t expecting the feedback, and you feel like your manager shared the feedback—instead of saving it for your 1:1—because they’re dissatisfied with your work. This is a “story” because you have no way of knowing if it is true or not.

Stories are inevitable—we all create stories from facts. But try to separate stories from facts, and avoid acting on stories until you’re able to validate them. For example, in this case, you might want to talk to your manager during your next 1:1 and ask why they shared feedback in a team meeting.

7. Make sure you’re speaking to the right person

Effective workplace communication is as much about who you’re talking to as it is about what you’re saying. Poor communication often occurs when you’re talking to the wrong people or trying to share information in the wrong setting.

To avoid this, make sure the right people are in the room or receiving the message. If you aren’t sure who that would be, go through an exercise to identify any important project stakeholders who might be missing.

5 tips to build effective communication skills in the workplace

If you’re a leader, you have the power to set and establish communication conventions on your team. Effective communication skills can build healthy company culture , foster trust among your employees, and break down silos between cross-functional teams. Here’s how:

1. Address any underlying changes

Before you start improving your team’s communication skills, ensure there are no underlying issues that keep everyone from communicating honestly. Does everyone feel comfortable talking openly? Is there anything that might make a team member feel like they can’t be their full selves?

One of the most valuable things you can do as a leader is to make sure your employees feel comfortable showing up to work as their whole selves (or as much of themselves as they want to bring). Whether that means voicing disagreements, talking about their passions outside of work, or being honest about what type of communication works best for them, make sure to understand each team member’s needs and ensure they’re being met in the team environment.

One theme that kept coming up in our employee engagement surveys was that we could improve information sharing and communication across the organization, so we looked for a way to do that.”

2. Frequently ask for feedback

If you don’t ask for feedback on your communication style, you may never get it. Even though communication in the workplace impacts every other interaction, team members might not immediately think of it as something to provide feedback on. By asking your employees for feedback on your communication style, you can continue to improve and develop clear communication strategies for your team.

3. Understand team communication styles

Another effective way to communicate with your team is to ask them how they want to communicate. Communication preferences shouldn’t be a secret—or a guessing game—and knowing off the bat if your team members prefer video conferences or phone calls, early morning meetings, or afternoon jam sessions can help you create an environment where they can thrive.

Important questions to ask include:

Are they an early bird or a night owl?

Do they like structured meetings or prefer free-flow brainstorming sessions?

Do they do their best thinking out loud, on the spot, or on paper?

What personality type do they identify with: introvert, extrovert, or ambivert?

Do they feel like they know their team members, or would they prefer more team bonding activities?

What types of meetings or tasks are most energizing for them?

4. Make time for team building or icebreakers

Getting to know your team is critical to developing good communication skills. It’s particularly important to make time to get to know your team outside of a workplace setting. Icebreaker questions can help bring an element of personality and fun to every meeting, so consider starting with a light chat before diving into your meeting agenda.

5. Set the tone

Remember: the way you communicate and collaborate will impact your entire team. It’s up to you to set the standard for open and clear communication in the workplace. Once you establish this standard, your team will follow suit.

Every few months, make a note to follow up with how everyone is feeling about team communication. Are there any habits that have cropped up in the last few months that you want to cull or encourage? Regularly thinking about how your team communicates—instead of “setting and forgetting” your team practices—can help you be more intentional about your communication methods.

As an organization grows, communication starts to bottleneck. At Hope for Haiti, we’ve seen those inefficiencies hurt us: when we can’t run like a well-oiled machine, we’re not serving as many people as we could be—and it’s our responsibility to improve upon that.”

More types of workplace communication

Most discussions about communication in the workplace assume the “workplace” is in person. But there are various forms of communication across different locations—from global offices to remote teams. Most effective communication best practices still apply to any type of team, but there are a few additional considerations and best practices you can use to help team members truly connect.

Distributed teams

Distributed teams work across multiple national or global offices. These teams might span different time zones and languages, and each office will have its own culture and habits. Don’t expect each distributed team to communicate in the same way—in fact, one of the advantages of distributed teams is the variety of thought you’re exposed to by working with teammates from all over the world.

If you work on a distributed team, it’s critical to over-communicate so that team members in different time zones and offices stay in the loop. Make sure to document everything in a central source of truth that team members can access when they’re online, and look for a tool that updates in real-time so no one has to slow down due to information lag.

Keep in mind that time zones might affect how people come to a conversation. Try to schedule meetings when everyone is available, or offer recordings and notes if team members can’t make it. It’s also critical to double check that the right people are in the loop, and that they aren’t just being left out because they’re in a different office than the majority of your team.

Online coworkers

If you’re working with a virtual team, it’s critical to establish where you’re going to communicate and how frequently. Knowing exactly what each communication tool should be used for can help team members feel connected—even while they’re remote.

While working remotely, we’ve had to re-learn how to communicate in many ways. Slack, Asana, and integrations between these tools has replaced or supplemented a lot of in-person ways we used to communicate.”

Remote team members can feel isolated and disconnected from one another, so consider doing an exercise with your entire team about preferred business communication habits. Some team members might love cold calls, while others might prefer scheduled meetings with concise agendas. Because team members have fewer chances to interact in person, it’s critical to establish these forms of communication as a team so you can keep the communication channels open.

Finally, make sure to bring team members in for regular team bonding events. Whether you’re doing icebreaker activities at the beginning of every meeting or scheduling some time to just chat at the end of each week, dedicated team time can help team members connect, no matter where they’re dialing in from.

The cherry on top of effective workplace communication

The last component of great communication is having a central source of truth for all of your communication and work information. Using a centralized system like a work management tool can help you coordinate work across all levels of your team. Learn more about how work management makes project coordination and communication easier in our introduction to work management article .

FAQ: Effective communication in the workplace

What are the best ways of communicating with your work colleagues.

The best ways of communicating with your work colleagues involve concise, respectful, and timely exchanges. This can be achieved through various channels, such as emails, instant messaging, face-to-face meetings, and video calls. Selecting the right medium based on the context of your communication (e.g., using emails for formal requests or Slack for quick queries) and ensuring you're concise and to the point can enhance the effectiveness of your communication.

Why is effective communication important?

Effective communication ensures that information is accurately conveyed and understood, resulting in improved efficiency, fewer misunderstandings, and better working relationships. It promotes teamwork, decision-making, and problem solving, which makes effective communication a cornerstone of successful operations and a positive work environment.

What constitutes effective communication?

Effective communication is characterized by clarity, conciseness, coherence, and considerateness, also known as the 5 Cs of communication. It means the message is delivered in a clear and understandable manner, is direct and to the point, logically organized, and sensitive to the receiver's needs and perspectives. It also involves active listening, openness to feedback, and the ability to adjust or paraphrase the message according to the audience and context.

How can you become an effective communicator?

To become an effective communicator, focus on clarity and brevity in your messages, actively listen to others, and provide constructive feedback. Pay attention to both verbal and nonverbal cues, such as body language and tone, to ensure your message is received as intended. Practice empathy by considering the receiver's perspective, and be open to feedback to continuously improve your public speaking skills.

Related resources

How to find alignment on AI

How to scale your creative and content production with Asana

Smooth product launches are simpler than you think

Fix these common onboarding challenges to boost productivity

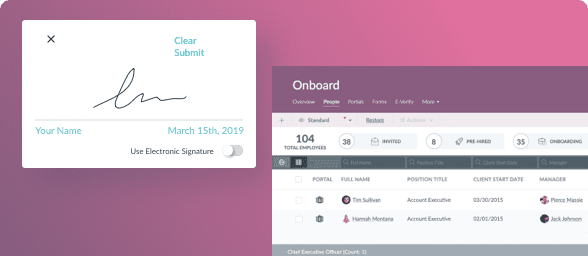

Try Onboard Interactive Demo

Click through it yourself with an interactive demo.

The Best ROI Calculator

In just a few clicks, you'll see how the HR Cloud Onboardig Solution delivers...

Onboard by HR Cloud Demo Video

Employee Communication Platform

Recognition and Rewards Platfrom

The Leading Employee Engagement Platform

The Digital Heart of Your Organization

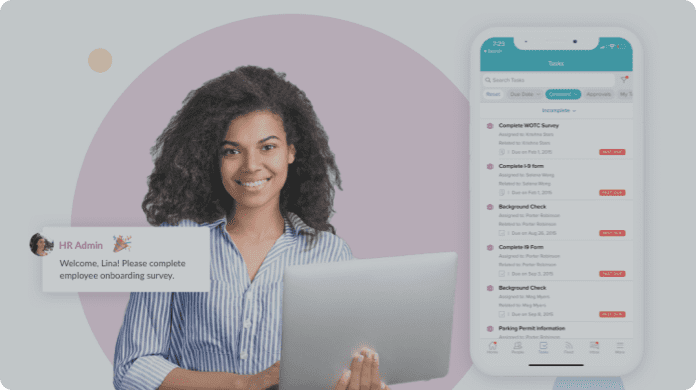

7 effective employee engagement case studies and strategies for a productive workplace.

- 1. Acknowledgment and Appreciation

- 2. Emphasis on Employee’s Holistic Wellness

- 3. Initiatives that are Development-Focused

- 4. Develop a Sense of Purpose, Values & Mission

- 5. Maintain Transparent Communication Channels

- 6. Create Conducive Working Conditions

7. Create Space for Fun & Happiness

Are you looking for employee engagement case studies? Learn from some of the best companies out there that have successfully increased employee engagement. See how they did it and what worked for them.

As more and more employers in today’s corporate world realize the importance of employee engagement , the demand for effective and result-oriented employee engagement programs is rising. The internet may present many employee engagement initiatives, but here’s something more: case studies to prove that certain employee engagement strategies are really effective. Follow our blog to learn more about employee satisfaction and ensure that your company is teeming with higher employee engagement initiatives.

According to Johnson and Johnson “ the degree to which employees are satisfied with their jobs, feel valued, and experience collaboration and trust. Engaged employees will stay with the company longer and continually find smarter, more effective ways to add value to the organization. The end result is a high-performing company where people are flourishing and productivity is increased and sustained.”

Nokia Siemens describes employee engagement as “ an emotional attachment to the organization, pride and a willingness to be an advocate of the organization, a rational understanding of the organization’s strategic goals, values, and how employees fit, and motivation and willingness to invest the discretionary effort to go above and beyond”.

While we learn what employee engagement means and its importance, incorporating practical and effective employee engagement programs as part of company culture is the right recipe for success. Here are certain strategies for best employee engagement with case studies.

1. Acknowledgment and Appreciation

The first and foremost step to boost employee engagement is making sure your employees are valued, acknowledged, and appreciated. This motivates employees to become more productive , stay on track with tasks, and perform well. This can be done in many ways and you need to choose an approach that your employees can relate with. While some enjoy public recognition, others don’t. Hence, you can work on innovative recognition ideas .

According to a study , social workers in a company received personalized letters of recognition at their home addresses. The workers were chosen randomly and half of them received letters while the rest half didn’t receive any. The first half of the letter was chosen from a few positive motivational sayings and the second half of the letter had a personal note of appreciation written by managers. After a month of the letter experiment, the workers who received letters felt more recognized and appreciated for their efforts, compared to those who didn’t get any. This also had a positive effect on their motivation levels and well-being, according to the results of this study.

Let Us Help You with Engaging Your Employees!

2. Emphasis on Employee’s Holistic Wellness

There are many components of employee wellness like nutrition, work-life balance , mental health, and stress management, to name a few. A healthy employee will be more productive and employees who are mentally and physically healthy will exhibit positive motivation, and better morale and resulting in a win-win for both employers and employees. A wellness program can be a good way to start where employees get a chance to explore yoga, in addition to vacation days. A wellness room provides employees with a personal space for their personal needs.

The indispensable role of wellness and an overall effective wellness strategy for an organization can be best understood based on a study that explored the objective of workplace wellness programs and their impact on employees health and medical expenses and so on. The study identifies certain key factors to boost wellness ideas in a corporate setup such as:

Effective communication strategy

Organizations that were part of this research emphasized the importance of how a wellness program is communicated to employees, both in-person and mass information campaigns, with messaging and clear interaction getting the highest priority.

Accessibility of wellness programs

Making wellness programs accessible for all employees is an effective strategy to boost the levels of employee engagement in their organization.

Engaged leadership

According to this study, for wellness programs to be successful, senior leadership should imbibe wellness as an integral and important part of the company culture.

Effective use of existing resources

Organizations leverage the existing resources and then build relationships, which also include health plans to provide employees with more options.

Ongoing assessment

Most companies agree that continuous assessments are required for employers to better understand their employee’s wellness needs.

Employee-Centric Engagement, Internal Communications, and Recognition

3. Initiatives that are Development-Focused

Ongoing development is key for every employee and there are a few development-focused initiatives that you can adopt actively to help your employees gain professional growth like professional networking, master’s or even Ph.D. programs, industry seminars, training courses and conferences, internal promotions, mentoring groups, and career coaching.

This study titled A Study on the Influence of Career Growth on Work Engagement among New Generation Employees involved six companies from diverse industries like consulting, finance, management, real estate, and so on. The findings of this study show that:

Organizational identification (IO) is very important for engagement levels and career growth.

Employee career growth positively impacts work engagement;

Person-organization value is positively linked to career growth and organizational identification (IO).

If employees recognize that they can make career progress in a company, they feel more attached and this increases employee loyalty, particularly for the new generation. It motivates them to put in the extra effort, improve performance, work on new skills, and so on.

4. Develop a Sense of Purpose, Values & Mission

A visible employee engagement program to achieve higher employee satisfaction levels requires employees to gain a sense of purpose, portray the company’s values and understand the mission. It is important to also understand what each of these attributes stands for.

Purpose

A company's purpose is the reason it exists in the first place. Purpose-driven companies are devoted to achieving goals that are bigger than just making money and increasing shareholder value. They also want to make a positive impact on the world around them and approach their work sustainably and ethically. In other words, they're committed to making a difference.

Mission

The mission of a company is similar but not identical to its purpose. Many people use the terms interchangeably, but we see the main difference as follows: the mission statement focuses on what the company has been built to achieve.

Values

Values are important because they act as a compass for the overall expectations of an organization - they guide how employees do their jobs, how managers communicate with clients and partners, and how workers interact with their peers. By understanding and sharing company values, employers can make better decisions that reflect the priorities of the business.

According to a study by Deloitte , a company’s purpose and mission impact corporate confidence as well, as indicated by the results of this study.

Nearly half of all executives (47%) say that they can identify with their company's purpose, while only 30% of employees feel the same way.

A whopping 44% of executives believe that exemplary leadership involves setting an example that lives and breathes the company's purpose - but only 25% of employees share this belief.

41% of executives believe that a company's purpose plays a significant role in major corporate decisions, whereas only 28% of employees feel the same way.

38% of leaders claim that their company's purpose is communicated clearly and openly to all, but only 31% of employees actually think this is the case.

Ultimately, teaching your employees about the company's purpose, mission, and vision takes time and patience. It's a gradual process, but when done correctly, it has numerous benefits for employers. Creating a sense of purpose for your employees allows you to see numerous benefits in the long run such as a more committed workforce and less employee turnover.

Social Intranet Software that Encourages Employee Communication

5. Maintain Transparent Communication Channels

Many employees feel reluctant to share their concerns and opinions with their managers or peers, either due to a perception that their managers don’t pay much attention to them or maybe they tried earlier but no action was taken by the leadership. Encouraging employees to share their concerns with leaders has its own benefits.

Practicing reflective listening helps managers to understand the message, through attentive communication.

Making employees understand they are respected helps them to respect you back and this is an employee engagement strategy based on common sense.

Acknowledging employee views is a way of recognizing a diverse range of ideas and respecting what they say, even though in the end you may still agree to disagree.

Seeking employee’s input actively helps to boost job satisfaction levels.

A research study analyzed communication between employers and employees and its impact on engagement levels. The findings supported the general definition of engagement as a sense of shared responsibility between both supervisors and employees, proving that establishing communication with your employees has a wide range of benefits and can work wonders for a company’s employee engagement levels .

6. Create Conducive Working Conditions

While expecting high performance from employees by an organization is quite natural, it is also equally important to provide necessary conditions for employees to do their best, by supporting them in any way you can. You can encourage positive and healthy competition in the workplace, show zero tolerance for toxic behavior, maintain a clean and healthy workplace ambiance, and create supportive teams . One way to support your workforce is by encouraging them to focus on things that are already good in their lives.

According to a consultant, Stephanie Pollack , a visible change is possible when employees are encouraged to know more about the benefits of gratitude and become aware of good things already existing in their lives. Showing gratitude has a plethora of benefits that range from reducing stress to making people feel better about themselves. It's important to build a culture of appreciation in your company so that employees feel comfortable expressing gratitude to one another and also feel appreciated in their jobs. This will not only lead to employees appreciating their jobs and coworkers more, but it will also help them appreciate themselves on a whole new level. Creating a grateful environment takes time, but it's worth it to see the positive transformation it can have on your organization as a whole.

Workers who are content with their jobs are more likely to be motivated, productive, and engaged than those who are unhappy with their work. And happiness usually comes with having fun. However, this doesn't mean that employees should neglect their tasks or ignore deadlines. Learning how to balance work and play is key to being successful in both areas.

Employees should get the chance to do fun stuff to uplift their moods and refresh their minds and thoughts. This will make them more productive while handling their daily tasks. This can be in the form of having lunch together, organizing joke sessions, quizzes, celebrating employee milestones and birthdays, hosting parties, sports activities, recreational outings, and so on. According to a study “ Finding Fun in Work: The Effect of Workplace Fun on Taking Charge and Job Engagement” , having fun in the workplace motivates employees in a positive way improving their job satisfaction levels, productivity, commitment, energy, and creativity. It also helps to reduce anxiety, turnover, stress, and absenteeism.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to improving employee engagement in the workplace. You can employ one or more of these strategies based on case studies and see what works best for you and your workforce. Creating a nurturing and fun-filled productive place can make a great difference for your company and its growth in the years to come.

Try Workmates Interactive Demo

Author Bio:

This article is written by a marketing team member at HR Cloud. HR Cloud is a leading provider of proven HR solutions, including recruiting, onboarding, employee communications & engagement, and rewards & recognition. Our user-friendly software increases employee productivity, delivers time and cost savings, and minimizes compliance risk.

Keep Reading

Top 8 workvivo alternatives for 2024.

Meta recently announced that it is shutting down its employee communications tool

27 Great Ideas for Employee Recognition

Everyone appreciates being praised for their efforts in the workplace. In fact,

Write for the HR Cloud Blog!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.1: Preface: Learning with Case Studies

Learning objectives.

- Identify the use of case studies in learning scenarios

- Describe the types of case studies available for learning use

Case Studies: Definition and Uses

Case studies are detailed “stories” about a business situation that allow us to consider a number of aspects of the business world:

- the diversity of everyday business situations we might encounter;

- the seriousness of some of the dilemmas business professionals routinely deal with;

- the consequences involved if a difficult situation is mishandled (if those involved do or say the wrong thing);

- the difficulty to choose the best response in a complicated business situation (sometimes, there is no ideal solution, and we might have to choose the least damaging solution instead).

These “stories” typically provide detailed information about the business situation in question, the problem encountered, how it was approached, and to what results. They can be shorter or longer, and strictly descriptive (most cases used for training purposes in college tend to be descriptive, and students are asked to analyze them) or analytical (some academic case studies provide analysis, too, and they might also make suggestions regarding better ways to address similar situations in the future). For instance, an academic article tracing Target’s failure to operate in Canada (2013-2015) would summarize in detail the facts of the case and analyze where the company went wrong; it might also suggest what the company should have done instead to secure a place on the Canadian market.

Professionals in different fields often use case studies as part of their research into various issues of interest for their organization (for instance, when they decide to launch a new product and/or service and want to learn from other companies’ success/failure before they plan their course of action). In college/university courses, case studies are used in order to connect the course material more effectively to the types of tasks the students will have to perform at work once they graduate.

Main advantages of learning with case studies — in general and in COMM 6019 :

- Case studies allow us to apply the theoretical knowledge we have acquired, so we can see how we can take advantage of our knowledge in everyday business situations.

- Case studies encourage critical thinking and collaborative learning.

- Based on what we know about professional business communication, we can use case studies to assess situations, examine options, trace a course of action for each option, and decide which might be the best. In so doing, we have to keep our focus on our goal.

- For each case study, we should try to make suggestions that would allow those involved to reach their goal, if possible, or get as close to their initial expectations as possible.

- people who are equally valuable in an organization might have very different leadership, management, or communication styles – and they might fail to appreciate each other for these reasons;

- depending on our boss and coworkers’ personality, background, and preferences, different approaches must be taken to ensure success (a direct approach might work with some of them, whereas others might prefer an indirect approach; there might also be situations when certain issues should not be brought up at all in order to avoid making a bad situation worse;

- choosing the wrong words in expressing an idea might have serious consequences for our career, even if we had the best of intentions in initiating contact with the other person(s) involved and did not mean to offend anyone.

Approaching Case Studies Analytically and Making Suggestions

Understanding the situation.

Whenever we work with a case study, we should take an analytical approach. First, we should make sure we understand the situation clearly. That includes identifying the following:

1. The problem/ issue:

What is the problem, exactly? In complex business situations, this question might not be as easy to answer as it seems. For example, there might be several problems involved, and trying to solve them all or treating them all as equally important might cause us to get lost in details and give insufficient attention to the one issue that might have the most damaging effect on our organization. In identifying the problem, we need to clearly distinguish between major concerns and peripheral aspects.

2. The context/background:

What caused the problem? Again, the answer might not be easy to formulate. There might be multiple causes, and some might have had more impact than others. Some of these causes might be out of anyone’s control: unpredictable market fluctuations due to natural disasters, etc. Others might be mistakes people made: lack of foresight in analyzing the market, communication problems, etc.

We also need to analyze the context in terms of the options available in addressing the problem. For example, the context might not allow for a certain type of approach (some obvious examples would be differences in legislation or in cultural norms between different countries).

3. The key aspects/facts of the situation:

Again, distinguishing between major and minor aspects might not be an easy task. Making this distinction might be particularly difficult for people who are directly involved in the situation. This may seem counterintuitive, but if, say, a project leader is more invested in some parts of a project than others for whatever reason, he/she might not be able to judge the key facts correctly in a crisis.

4. The decision-maker’s priorities and goal:

We need to understand exactly what the decision-maker is hoping to achieve, as well as what he/she can – realistically – achieve. We also need to understand the decision-maker’s and the company’s priorities. Caution is recommended here: the decision-maker might not be aware that there is a mismatch between the goal he/she has set and the company’s priorities. If that is the case, our recommendations may have to include cautious explanations that might help the decision-maker redefine his/her goal.

Analyzing Options

Next, we should try to see how many options the decision-maker might have. The key question at this stage is the following: Can the problem be solved (can all negative aspects or effects be completely eliminated) or is reducing the negative effects the best we can hope for?

Many professionals sometimes make a situation worse because they naïvely assume that every conflict or problem can be completely eliminated, in all its overt and hidden implications/ consequences. Thus, they set the wrong goal (an unreachable goal ) and choose their strategies based on that goal. In such situations, the results can be disastrous – financial losses, loss of reputation, etc. — because resources will be wasted on aspects that were hopeless to begin with. Setting a more realistic goal (say, to improve specific aspects of the situation in a limited, achievable way) would allow decision-makers to select the right strategies to reduce losses as much as possible, and to get the most out of the resources available.

Presenting Persuasive Suggestions

Finally, after analyzing the situation and the available options, case studies allow us to present and motivate our recommendation as we would at work. To make our recommendation persuasive, we should offer several options (typically, at least two or three) and discuss them in detail, to show that the one we recommend is the most likely to lead to a positive outcome.

Here are some aspects to consider in choosing the solutions we should discuss and then selecting the best one:

- If other decision-makers involved seem to favour an approach with which we disagree, we need to include that approach as one of the options, analyze it, and show that it will have limited success or that it comports serious risks.

- Potential improvements, as well as potential risks need to be discussed in detail for the solution we want to recommend, too. If we do not mention some obvious drawbacks of the solution we support, we can lose our credibility.

- The idea is to show that we have carefully weighed all relevant options and that we chosen the option that seems to be the most advantageous.

Case Study Work in COMM 6019 and Workplace Applications

Depending on your course section and professor, you might have to do more or less case study-related work in this course, but you are likely going to be asked to complete at least two case study-related assignments. Specifically, your professors might use information from case studies to create scenarios for your written assignments, or they may ask you to find and/or analyze case studies specific to your field, always with a focus on communication aspects. Case study elements can also be used in the Research Report, although they are not mandatory.

Our work with case studies in COMM 6019 is meant to help you assimilate the necessary strategies in analyzing any business situation (from a communication perspective, as well as in general). This experience will prove particularly useful when you are asked to complete analytical reports and recommendation reports at work. Any routine business situation, as well as any crisis, can be analyzed in this manner to make sure we arrive at the best decision.

Whenever you are assigned this type of task in the workplace, make sure you understand what you are expected to do and that you do just that:

- In some cases, you might be asked for a recommendation, whereas in others you might just be asked to analyze options.

- If you are asked to analyze options, you can still explain which option you think is best, to show initiative – but only if you think your reader(s) would be open to accepting a recommendation. (Some upper-management employees might think that you are overstepping your mandate if you do that. Always consider your primary audience carefully when you make such decisions.)

In courses focused on field-specific skills, professors usually use complex case studies, and the students are expected to produce lengthy case study-related assignments (reports). Thus, the case studies provided to students would be at least 4 pages long (usually much longer), and the reports the students would be expected to write might be 2000-word reports that include information from several research sources.

In COMM 6019, our focus is on teaching students how to analyze situations and make recommendations in objective language and without saying anything that might be perceived as unnecessarily negative, insensitive, or offensive . To this end, we typically use short case studies and short articles reporting various real-life business/professional incidents as “prompts” for assignments – to help you understand what kinds of problems professionals have to deal with in the business/professional world and what might be the best approach from a communication perspective . Your professors might also ask you to read a longer, more complex case study but focus on just one particular aspect of the situation instead of providing a full-length case study analysis (a long report). This is meant to stimulate your critical thinking skills while maintaining the focus on the main objective of this course – helping students to acquire the writing and communication techniques they need in order to make their case effectively in any business situation, however difficult/ sensitive.

A Sample Case Study

Here is an example of a case study we might use in a Professional Communication class:

- https://www.iveycases.com/ProductView.aspx?id=35525

This is a tricky case study – as case studies usually are. In class discussions, some students rush to suggest that the two business people involved should set up a meeting and solve their financial disagreements immediately, so that they can work together on the new task they have been assigned. However, a more careful analysis of the case study would show that this is a naïve approach. The details provided about the two individuals’ educational background, personality, work history, and history of business conflict (including a lawsuit!) clearly indicate that they won’t be able to “solve the problem” in a meeting (or two, or ten). Therefore, what they need to do is agree to focus on the new task and never mention their previous problems in meetings related to the new task, allowing the old conflict to be solved in court.

Once this aspect of the situation is clarified, a good way to use this case study for an assignment in COMM 6019 would be to ask students to pick one of the two business professionals and write a short recommendation report from a Communication perspective, advising the person of their choice that the best way to approach the situation is to keep the old conflict and the new task separate. To be persuasive and useful, the report would have to include the following sections:

- an analysis of the situation, explaining why this is the best option;

- a section of detailed suggestions concerning exactly how the person they are advising should behave, exactly what he should say, etc.

In order to help you to understand a little better the relevance of the content studied in this course for the work you will do as professionals, your professors may relate case studies or media coverage of business/ professional/ corporate incidents to any number of themes covered in this course, from effective social media use to workplace diversity and intercultural communication to employment interviews.

Case Studies and Workplace Communication: Quick Example

Here is an example of a costly communication mistake concerning the channel of communication chosen by the sender of the initial message and the role the receiver decided to assume — a mistake with serious international consequences, as you are about to see.

You might have heard that Hillary Clinton is assumed to have lost quite a few votes in the US election in 2016 after some emails exchanged between individuals in high-ranking positions in her campaign were “leaked” as a result of hacking. According to a December 2016 New York Times article, FBI agent Adrian Hawkins called the Democratic National Committee in September 2015 to warn them that their computers are being hacked by “The Dukes,” a cyberespionage team linked to the Russian Government. He was transferred to the Help Desk and spoke to Yared Tamene, a tech-support contractor working for the DNC, who did a routine check of the DNC computer system logs to look for evidence of a cyberattack and did not find any.

Tamene was not an expert in cyberattacks, and “The Dukes” appear to be a sophisticated group – they are suspected of having hacked the unclassified email systems of the White House and the State Department, among other cybercrimes. Apparently, Tamene was not sure if Hawkins was a real FBI agent or an impostor – sohe did not conduct a more thorough search for signs of hacking and did not transmit the information to higher-ranking DNC officials, although Special Agent Hawkins called repeatedly, over several weeks.

You can read a New York Times article on this topic here if you are not familiar with the incident:

- The Perfect Weapon: How Russian Cyberpower Invaded the U.S . (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/us/politics/russia-hack-election-dnc.html?_r=0)

It is easy to see that several communication mistakes are to blame for the fact that the cyberattack was not stopped right away. Most importantly,

- The FBI agent spoke on the phone with a tech desk employee instead of setting up an official face-to-face meeting with a top DNC official (he made a serious error in choosing the channel of communication and the person to contact).