Civil War Reenactments Were a Thing Even During the Civil War

These ‘practice battles’ are the root of today’s Civil War reenactors

Kat Eschner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/fd/21fd01ba-a410-45fd-a5cc-8beef0bb0a92/2014plainviewmnparadecivilwar.jpg)

Thousands of people participate in Civil War reenactments each year in the United States. They’re sharing a tradition of reenactment that stretches back to the years of the war itself.

To herald Christmas 1861, a year when more than 4,000 fighting men had been killed in Civil War battles and the Union was in disarray, groups of citizens got together to fight mock battles simulating the conflicts raging on battlefields elsewhere. Writes Sue Eisenfeld for The New York Times, " We tend to think of Civil War reenactment as a modern phenomenon, a way for people in the 20th and 21st centuries to experience a taste of what the conflict was like. But in fact, staged battles began while the war was still underway. Known as 'sham battles,' 'mock battles' or 'mimic battles,' these battles were enacted for a variety of reasons: entertainment, practice and to demonstrate to civilians back home what happened during the war."

Shams were especially popular during the holidays for entertainment, and they were mostly confined to the North. On December 5, 1861, the Daily Nashville Patriot published an article noting “the Yankees are great on shams,” she writes. But they were also intended to accustom new soldiers to the pace of the battlefield and help them imagine themselves as fighters, rather than farmers, she writes: "Some places, like Forst Monroe, a Union outpost in Virginia, conducted sham battles daily."

As the New Georgia Encyclopedia records , Civil War reenacting was part of a longer tradition of shams fought with blank ammunition by American militias. Before the Civil War, town festivals often featured a pageant with costumed citizens dressing as Revolutionary War figures.

Directly after the war ended, Eisenfeld writes, veterans were commissioned to serve as reenactors of a conflict they themselves had fought in. ""On April 21, 1865, the town of Massillon, Ohio, was right back into the business of luring crowds with sham battles as part of a day-long 'jubilation over the recent victory of the Federal armies and the surrender of Lee.'" The pageantry and drama of mock warfare offered great entertainment, even when the consequences of the real thing were so bloody.

Later, when public interest in the war revived in the 1880s, the tradition of the sham battle was revived, and many sham battles were conducted purely as entertainment, the Encyclopedia writes. “Although these sham battles were usually not attempts to re-create specific Civil War battles, they were conducted with strong undertones of both sectional pride and national unity.”

The idea of reenacting stuck around, but modern Civil War reenactment was truly born in the early 1960s around the time of the war’s centennial. The first big reenactment, of the First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas , took place on July 21-22, 1961.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Kat Eschner | | READ MORE

Kat Eschner is a freelance science and culture journalist based in Toronto.

The Military Influence on Historical Reenactments Explained

- July 22, 2024

- Military Influence on Culture

The intricate relationship between military influence and historical reenactments reveals a fascinating dynamic of cultural preservation and community engagement. Military influence on historical reenactments serves not only to educate but also to commemorate pivotal moments that have shaped societies.

Throughout history, reenactors have played a significant role in depicting military strategies and events, ensuring that the sacrifices and legacies of former generations are honored. This phenomenon reflects the broader implications of military influence on culture, shaping our understanding of history and its impact on contemporary society.

Table of Contents

Historical Context of Military Reenactments

Military reenactments have deep historical roots, emerging prominently in the 19th century. The practice gained traction during the period when nations sought to commemorate pivotal battles and events, fueling a renewed interest in military history.

As societies evolved, the military’s influence on historical reenactments became significant, reflecting not just past conflicts but also broader cultural narratives. Events like the American Civil War reenactments prominently illustrated these historical contexts, showcasing both the valor and challenges faced by soldiers.

The motivations behind reenactments varied, including educational purposes, community bonding, and patriotic expression. The influence of military events on cultural identity remains apparent even today, as reenactors aim to bring history alive by accurately portraying the experiences of those who lived through significant military upheavals.

Through the lens of history, military reenactments serve as a bridge connecting contemporary society to the past, highlighting the role of military influence on cultural preservation and collective memory.

Military Influence on Cultural Preservation

Military reenactments serve as a vital conduit for cultural preservation, embodying the historical experiences of societies engaged in conflict. Through meticulous recreation of military events, these reenactments provide a tangible connection to the past, fostering an understanding of historical narratives that might otherwise fade from collective memory.

The emphasis on accuracy in uniforms, weaponry, and battle tactics ensures that participants and spectators alike gain insight into military life and the societal values of corresponding eras. This commitment to detail contributes to a broader appreciation of cultural heritage, effectively demonstrating how military influence shapes societal identity and historical consciousness.

By engaging communities in these reenactments, participants foster a sense of pride and awareness regarding their shared history. This process not only educates newer generations about past conflicts but also highlights the cultural elements intertwined with military actions, such as traditions, ceremonies, and the arts reflecting wartime life.

Ultimately, military influence on cultural preservation plays a crucial role in maintaining the legacies of historical events. It transforms historical knowledge into an engaging experience, thereby reinforcing the importance of understanding military history within the larger tapestry of cultural identity.

Types of Military Historical Reenactments

Military historical reenactments can be categorized into several distinct types, each reflecting different periods, events, and aspects of military history. One prominent category includes battle reenactments, which aim to replicate significant historical conflicts such as the Battle of Gettysburg or the Battle of Waterloo. Participants often engage in scripted battles with a focus on tactics, period uniforms, and weaponry.

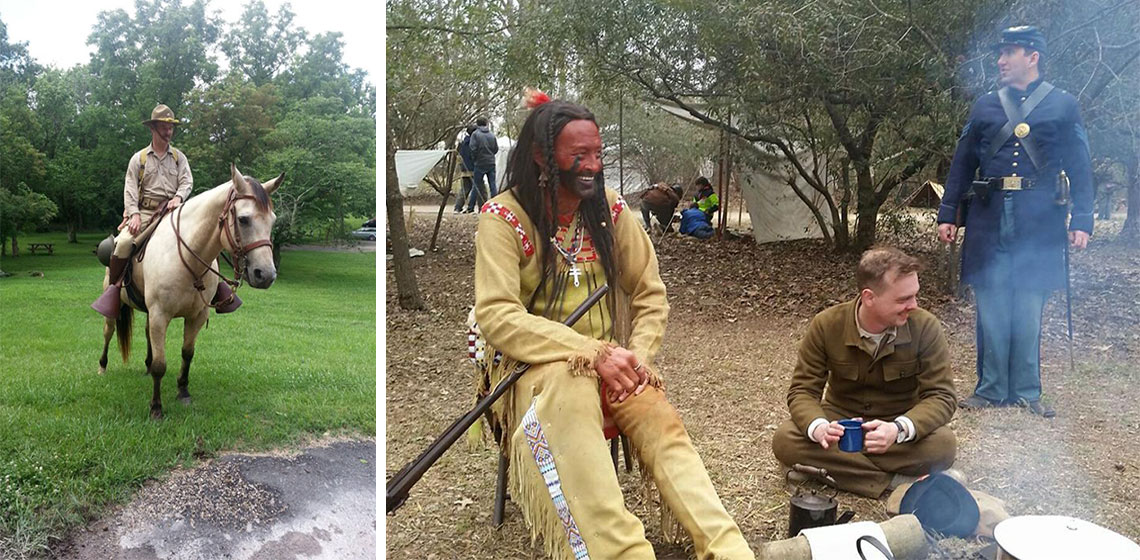

Another type encompasses living history displays, where reenactors portray everyday military life. This may include demonstrations of camp life, medical practices of the time, and interactions with the public, allowing attendees to gain insight into the realities faced by soldiers.

Tactical demonstrations represent yet another form, emphasizing specific military maneuvers, formations, or strategies. These events may focus on less-known battles or specific historical techniques, showcasing the evolution of military tactics influenced by historical contexts.

Lastly, some reenactments highlight specific military units or campaigns, offering detailed narratives around organizations like the 101st Airborne during World War II. Each type of military historical reenactment contributes to a broader understanding of military influence on culture and history.

Educational Value of Military Reenactments

Military reenactments serve as a dynamic educational tool, providing firsthand experiences of historical events and military life. Participants and spectators gain insights into specific epochs, fostering a deeper understanding of the societal impacts of warfare. Such reenactments bring history to life, making it tangible and relatable.

Through military reenactments, individuals learn about various tactics, equipment, and the daily realities faced by soldiers. Detailed explanations and demonstrations highlight the complexities of military strategies, allowing audiences to grasp the nuances of different historical battles. This immersive experience enhances retention and encourages critical thinking.

Moreover, reenactments often include discussions and workshops facilitated by historians and experts. These sessions address historical contexts and analyze the implications of military actions, promoting informed dialogue between participants. This educational value extends beyond entertainment, cultivating a greater appreciation for historical preservation.

In developing an understanding of military influence on historical reenactments, it becomes evident that their educational benefits are invaluable. The combination of engaging activity and factual information supports an enriched learning environment for all involved.

Community Engagement in Reenactments

Community engagement in military historical reenactments serves as a vital connective tissue between the past and present, drawing individuals from diverse backgrounds into a shared experience. Events such as battlefield reenactments, living history camps, and parades encourage local participation, fostering a sense of belonging. Citizens are not just observers; they play active roles in portraying history.

Through collaborative efforts, communities enhance cultural awareness and pride. Reenactments often involve schools, veteran organizations, and local governments, which provide opportunities for education and dialogue about historical events. This engagement cultivates an appreciation for military heritage and its implications within contemporary society.

Moreover, military influence on community engagement manifests through volunteerism. Many reenactors dedicate time and resources to prepare for events, which strengthens bonds among participants. Their commitment ensures that these reenactments honor historical accuracy while also becoming platforms for learning and social connection.

Ultimately, military historical reenactments create environments where communities can gather, learn, and reflect on their historical narratives. This engagement not only enriches the cultural fabric of an area but also instills a deeper understanding of the impacts of military history on community identity.

Economic Impact of Military Reenactments

Military reenactments serve as significant cultural events that contribute markedly to local economies. The convergence of history enthusiasts, participants, and tourists creates a vibrant atmosphere that stimulates various economic activities.

Tourism generated by events is a primary driver, as reenactments attract thousands of visitors. Many come from different regions or cities, significantly impacting local hospitality sectors, as attendees require accommodations, food, and transportation.

Local business support also flourishes during these events. Vendors selling military memorabilia, food, and beverages experience increased patronage. Additionally, surrounding businesses, such as retail shops and restaurants, benefit from a surge in foot traffic, further enhancing economic viability.

Such economic benefits underscore the profound military influence on historical reenactments, illustrating their role as catalysts for community engagement and financial growth.

Tourism generated by events

Military reenactment events have become significant attractions for tourists seeking to engage with history. These events draw large crowds, offering immersive experiences that transport visitors to different eras. The allure of witnessing historical battles and encampments fosters a unique opportunity for cultural exploration.

Many cities and regions host reenactments, which can lead to increased tourism. Events often include historical displays, demonstrations, and interactive sessions. Notably, these events typically draw visitors interested in military history, family groups, and educational institutions.

Tourists are also attracted to the atmosphere and authenticity of military reenactments, resulting in increased local economic activity. The benefits include:

- Higher hotel occupancy rates.

- Increased patronage of local restaurants and shops.

- Opportunities for artists and vendors to sell historical-themed merchandise.

These events engage communities while enhancing appreciation for history, contributing significantly to the tourism sector. In turn, this military influence on historical reenactments enriches not only local culture but also the economic landscape.

Local business support

Local business support during military historical reenactments often manifests through increased sales and community engagement. These events attract participants and spectators, leading to a boost in revenue for nearby businesses.

Local enterprises, including restaurants, hotels, and shops, benefit significantly from the influx of tourists and participants. The demand for food, lodging, and merchandise often multiplies during reenactment weekends, creating a symbiotic relationship between the events and local commerce.

Key areas that witness economic support include:

- Restaurants offering themed menus and promotions.

- Hotels accommodating reenactors and history enthusiasts.

- Local shops selling merchandise related to the historical periods depicted.

By fostering this connection, military influence on historical reenactments not only revitalizes community pride but also strengthens the local economy.

Military Influence on Event Organization

Event organization in military historical reenactments is significantly shaped by military principles and practices. The need for discipline, hierarchy, and role assignment mirrors military structures, ensuring that events run smoothly and efficiently. This influence is exhibited through structured rehearsals and positions, which contribute to the overall authenticity of reenactments.

Key roles are often designated based on military ranks, promoting a sense of realism and fostering a deeper understanding among participants. These roles help delineate responsibilities, from event coordinators to performers, ensuring that all aspects of the reenactments align with historical accuracy. Coordinators often rely on military protocols to organize logistics, such as staging, safety measures, and participant movement.

Military influence extends to the selection of locations and the setup of camps, closely resembling historical scenarios. Often, venues are chosen to replicate authentic military conditions from the respective historical period, enhancing the immersive experience for both participants and audiences. This meticulous attention to detail underscores the profound impact of military organization on the structure and execution of these reenactments.

Depiction of Military Strategies in Reenactments

Military strategies are often meticulously depicted in historical reenactments to provide audiences with an accurate representation of past conflicts. Reenactors study tactics, formations, and operational methods employed during significant battles, ensuring that their portrayals reflect military doctrine of the time.

Using primary source materials, scholars and enthusiasts analyze documented strategies such as the use of the phalanx in ancient Greece or Napoleon’s innovative troop movements. This in-depth research allows for a genuine replication of military engagements, offering insight into how battles were won or lost based on strategic decisions.

Additionally, reenactments often emphasize communication and coordination among troops. Demonstrating the command structure and relay of tactical orders sheds light on the challenges faced by military leaders and their units, enhancing the educational aspect of these events.

Overall, the depiction of military strategies in historical reenactments not only honors the past but also serves to educate audiences about the intricate dynamics of warfare and its impact on history. These portrayals enhance the viewer’s understanding of military influence on culture, grounding reenactments in historical authenticity.

Challenges Faced by Reenactors

Reenactors face a myriad of challenges that can affect both the authenticity and enjoyment of military historical reenactments. One significant issue is balancing authenticity with creativity. Reenactors strive to create an accurate representation of historical events, yet artistic liberties may be taken to enhance engagement for audiences. This tension can lead to debates regarding the legitimacy of certain portrayals.

Historical misinterpretations also pose a challenge. Inaccurate depictions of military tactics or events may misinform audiences about critical historical facts. This can dilute the educational purpose of reenactments, as viewers may leave with skewed perceptions of history, thus undermining the military influence on historical reenactments meant to foster a deeper understanding of the past.

Additionally, the pressure to reproduce genuine military experiences can lead to logistical issues. Ensuring that all equipment, uniforms, and scenarios meet historical standards requires extensive research and resources. This demand can overwhelm smaller reenactment groups, who may struggle with the costs and commitment needed to deliver a credible performance. Balancing these challenges is essential for the ongoing success of military historical reenactments.

Balancing authenticity and creativity

Achieving a balance between authenticity and creativity in military historical reenactments is a complex endeavor. Reenactors strive to accurately reflect the military tactics, uniforms, and cultural context of specific historical periods. This authenticity is vital for educating the audience about military history while preserving the integrity of the events represented.

However, creativity often enters the equation when adapting these historical elements for modern audiences. The necessity to create engaging displays can sometimes lead to embellishments or deviations from historical accuracy. This blending can enhance the viewer’s experience but risks distorting the genuine narratives and lessons that military history imparts.

Reenactors must navigate this tension carefully, factoring in the expectations of their audience, which can range from history enthusiasts to families seeking entertainment. Ensuring that the military influence on historical reenactments remains rooted in factual representation while still captivating and engaging is essential for fostering a deeper public appreciation of military heritage. Ultimately, a thoughtful approach to creativity complements the pursuit of authenticity, enriching both the event and the audience’s understanding.

Historical misinterpretations

Historical misinterpretations in military reenactments often arise from the complex interplay between storytelling and factual accuracy. These misinterpretations can skew the understanding of military events, leading audiences to form misguided perceptions about historical realities.

Reenactors, while aiming for authenticity, may unintentionally exaggerate certain elements for dramatic effect. This often results in a portrayal that does not accurately reflect the nuances of military strategies, motivations, and the personal experiences of soldiers. Misconceptions about the impact of specific battles or technologies can also emerge.

Factors contributing to historical misinterpretations include:

- Limited scholarly research informing reenactment narratives.

- Overreliance on popular culture and media representations.

- Individual biases of reenactors influencing their portrayals.

It is crucial for participants and organizers to strive for a balanced presentation that respects the historical context while engaging the audience. Acknowledging these misinterpretations can enhance educational value and promote a deeper understanding of military influence on historical reenactments.

The Future of Military Historical Reenactments

The future of military historical reenactments appears promising as it adapts to changing societal interests and technological advancements. Increasingly, reenactors are utilizing digital platforms and social media to reach broader audiences, fostering community engagement beyond traditional events.

As awareness of historical inaccuracies grows, organizers may implement more rigorous standards for authenticity. This adjustment will not only enhance the educational impact but will also deepen the appreciation of military influence on historical reenactments, thereby maintaining their relevance in modern culture.

Technological innovations, including augmented reality and immersive experiences, will likely shape reenactments. These advancements can elevate participation levels and increase the overall audience experience, blending entertainment with education while preserving cultural heritage.

Moreover, collaboration with educational institutions may facilitate further research and resources, creating a feedback loop that enriches the depth of presentations. This approach can ensure that the military influence on historical reenactments continues to foster interest in heritage and encourage ongoing participation in the future.

The military influence on historical reenactments plays a crucial role in shaping cultural understanding and appreciation. By participating in these events, reenactors contribute to the preservation of history while fostering community engagement and stimulating local economies.

As the future of military historical reenactments unfolds, it will remain essential to balance authenticity with creativity. This delicate interplay will ensure that these reenactments continue to educate, inspire, and resonate with audiences, promoting a deeper comprehension of our military heritage.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

American Revolution

Battle of Gettysburg

Gettysburg National Military Park

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing these subjects:

- Warfare and Defence

military reenactments

Quick reference.

The replication of historically significant battles and campaigns by actors or civilian enthusiasts dressed and equipped in period clothing, weapons, and accouterments. Military reenactment, especially the reenactment of Civil War ...

From: reenactments, military in The Oxford Essential Dictionary of the U.S. Military »

Subjects: Social sciences — Warfare and Defence

Historical Reenactment

New ways of experiencing history.

- Edited by: Mario Carretero , Brady Wagoner and Everardo Perez-Manjarrez

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Berghahn Books

- Copyright year: 2022

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Main content: 204

- Keywords: Memory Studies ; Performance Studies

- Published: September 13, 2022

- ISBN: 9781800735415

- < Previous

Home > SAS > History and Social Studies Education > Museum Studies Theses > 31

Museum Studies Theses

Aiming to Reenact: The Efficacy of Military Living History as a Learning Tool

Department Chair

Andrew D. Nicholls, Ph.D.

Leah T. Glenn , State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Follow

Date of Award

Access control.

Open Access

Degree Name

Museum Studies, M.A.

- History and Social Studies Education Department

Cynthia A. Conides

First Reader

Second reader.

Noelle J. Wiedemer

People around the world have been fascinated with recreating the past since antiquity. Over the past century, however, the presentation of historical information using various forms of human interaction and animation has gained increasing attention, at least in the historic site community if not largely accepted among academic historians. Utilizing a number of non-traditional tools to create a multisensory experience for visitors, this “living” history aims at entertaining the public while providing insights into the past not easily gained through more academic means. Further, there have been many sites, particularly those with a military theme, that have chosen to utilize volunteer “reenactors” to augment their regular programming. Encompassing everything from small military encampments to large-scale mock battles, the subject of reenactment has been both popular and controversial.

This thesis will evaluate to what degree military reenactment is an effective tool in interpreting the history of past events. To do so, one must begin with identifying the major principles of historic interpretation, as they have evolved over the past seven decades, providing important definitions along the way to lay the proper groundwork for the study. Within the larger realm of historic interpretation, a survey of the subtopic of “living history” and its employment at historic sites will provide further context against which to examine the use of reenactment to achieve the goals of both.

Recommended Citation

Glenn, Leah T., "Aiming to Reenact: The Efficacy of Military Living History as a Learning Tool" (2021). Museum Studies Theses . 31. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses/31

Since May 11, 2021

Included in

Archival Science Commons , History Commons

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Buffalo State

- E. H. Butler Library

- Buffalo State Archives

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- Submit Research

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Breathing Life Back Into the Past

The hobby of historical re-enactment now has a deep history of its own. The sealed Knot Society, the first reenactment society, was formed as long ago as 1968, the last year steam was used on British Railways.

There is no shortage of history in Britain. Nor is there any noticeable shortage of volunteers to bring it to life. Almost 20,000 enthusiasts give up their time, money and weekends in some 140 reenactment societies the length and breadth of the country.

Time periods brought back to life range from the Viking era up to World War II. Re-enactments even extend to overseas: colonial North America during the Seven Years War, the French and Indian War, the Wild West and the Lone Star state.

Visitors to Britain can find re-enactments at National Trust properties, stately homes, village fetes and other locations that can be easily visited by BHT readers. The majority of these events are staged in the summer and autumn months.

Read more: Does the Queen have secret hand signals?

Revolution!

‘"The shot heard round the world" was the spur for two Leicester men, Alan Ball and James Martin, to found Redcoats and Revolutionaries in 2012. The idea was to be able to put on a show involving both sides of the conflict, rather than just concentrate on one particular military unit or battle. The founders met at the Loaded Dog pub in Leicester to form the group.

Ball says: "I'm just a history junkie. I joined a Viking re-enactment society at 16, mainly to duel my friends with swords. They left after three weeks and I'm still a member 16 years later. Quite a few reenactors get the bug to look more deeply into another period of history; for me it was the War of Independence, something I initially knew very little about apart from the clichés and movie stereotyping.

The more I read, the more interested I became–the smart 18th century aesthetic didn't hurt. But the main thing was the extremely vivid images of the struggle for a nation, a truly global war. Just experiencing a tiny fraction of that is appealing."

The group reenacts the 17th Regiment of Infantry, the "Leicestershire regiment." Extremely active in America throughout the war, it remains part of the modern day British army. A couple of members wanted to portray a light infantry company and chose the 40th Regiment. On the revolutionary side, the group portrays the Lexington Minute Company.

It is not unknown for actors to swap sides. Ball said: “I guess people have such a wide variety of interests that playing the good guy or bad guy either does not concern or interests them more. Arguably, for me at least, the most interesting thing about the War of Independence is that there is no clear good versus bad–unless you believe The Patriot. It was an incredibly messy circumstance born of complicated politics and early globalism.”

Read more: Do we finally know who Jack the Ripper is?

A great hobby

Ball says that it is a "great hobby" that takes as much or as little time as a volunteer can offer: “Some groups insist on a minimum commitment; for us the cost of equipment is proof enough of commitment–about £2,000 for a good military impression.

We do about 10 weekends a year, either for ourselves (experimental archaeology) or members of the public. Many of us also meet once a month for a drink. We try to be engaging while being accurate.

“Most of the time we try to be good educators and speak in the third person. I am just a guy dressing up to show you cool stuff about history. But when we're on a site that lends itself to presenting “living history,” we get in character by trying to do the things that people did.

“In terms of military reenactment, that is camp duties, arms drill, sentries, exercises and so on. Our civilians use their practice of historical crafts and make things. We will often try and perform a particular small event from history; a skirmish between troops, a seditious sermon from a preacher, highway robbery and smuggling. All sorts. It's just loads of fun.”

Read more: Ronald Brittain: The loudest voice in the military?

Coining it in.

Last year, the group was contacted by organizers of a two-day display of the Amon Carter Flowing Hair Silver Dollar (worth $10m) alongside an original copy of the Declaration of Independence in London, staged on the 240th anniversary of the Siege of Boston’s last day in 1776.

Ball recalls organizers wanted some Redcoats and Americans: “Sadly none of ours were available, so they hired an actor and costume from a theatrical company.” The volunteers traveled to London fully costumed on the train, making the local news.

When the society was established, there was a fair bit of interest from the re-enactment community in the US. Ball notes: “A few kind souls gave us some much needed help and advice and shared a great deal of knowledge of historical sources and their own research.

We were really keen to get it right–make reproductions to an accurate standard, and study the smaller things that make a re-enactment “live”–mainly the daily duties of soldiers, and the civilians who practice their crafts. One member of the 17th Regiment of Infantry in America visited us a couple of years ago and put us through our paces.

“We have about 10 people that portray Americans, but sadly no actual Americans! All of them portray civilians who have taken up arms in our militia while working their crafts such as blacksmith, gunsmith, tailor, cook and others.”

Are they all just sublimating, frustrated thespians? “Probably,” laughs Ball. “To be honest, there are plenty of shy, retiring kinds in re-enactment who just have a keen interest in history and let the more extrovert “luvvies” do the dramatic stuff. I’m perfectly happy to be a body in the background–an extra if you like–in proceedings, but having started the group I have left my comfort zone on a few occasions and really enjoyed it. Maybe I'm wasted at a desk!”

Read more: 7 of Britain's best tourist attractions

A Voice for the Voiceless

A famous writer who championed the poor is the inspiration behind Gillingham, Kent-based living history group Voices from Victorian London. Carole and Leslie Allman have taken to the 1850s writings of Henry Mayhew to portray those from the wrong side of the tracks.

Leslie says: “Our main characters are Navy, Polly and Beefy, created from the writings and interviews of Henry Mayhew. These writings involved detailed and heart-warming interviews with all sorts of lower class individuals. These provided the perfect base from which to give them a voice again, which means behaving and sounding as they would, together with the addition of some of our own personalities.

“They were the dregs of Victorian society with little or no education, desperately trying to stay away from the workhouse, surviving as best they could from morning to night by whatever means they could find, legally or not. They were classed as criminals simply because they were poor, which of course wasn't their fault. They were the same as we are today with human emotions and frailties. They still laughed, cried, loved and died, but without any hope of something better in life.”

The newly-formed group is barely a year old and focuses on appearances in Kent/Sussex/Surrey. There is a current membership of six, a guest member, an associate member (who is the photographer) plus a newborn “baby” doll and the mysterious Quivering Meg.

Read more: The Battle of Hastings and how the Normans changed England

War of Independence Re-Enactment

Living history

The couple prefer to use the term “living history” rather than re-enactment, because of their detailed attention to characterization, something they consider is lacking from many other historical groups.

Leslie says: “It has never been our intention to re-enact the past, but to become the past! In creating our window into Victorian London, we find that our characters mentally come to life as we are getting costumed, each item of clothing and makeup developing the mindset. Despite what some people think, we are not frustrated actors, for actors have the training and experience to become a multitude of characters with different voices and we do not.

“The very poor in this period are seldom portrayed, unlike the finely dressed ‘posh’ of the period. Unfortunately, however well intentioned, some may be in their portrayal of the period, but many constantly fall down on historical accuracy. Being “down and dirty ”takes a lot more effort and research to get it right, but we consider it to be a lot more fun!”

He admits the research is time consuming but it is fascinating, as they are constantly finding things out that they would not have even thought of inquiring about had they not been portraying this social class of the period.

Leslie notes: “When interacting with our audience we remain totally in character and use period slang and express ions. This has to be restricted as if we went the whole nine yards , no one would understand what we talking about, including us! We have had some American visitors to the events in Rochester and look forward to meeting many more in the future.

Read more: General William Howe and the War of Independence

Catching Up with the Past Summer in Britain is the perfect time to catch up with some of the many reenactment societies that allow you to catch up with the past. Redcoats and Revolutionaries: redsandrevs.co.uk

Voices from Victorian London: voicesfromvictorianlondon.com

Heading up North? Catch Lace Wars.

Lace Wars is a number of regiments depicting both military and civilian life during the 18th century. Specializing in the period of 1740 to 1760, in particular the Jacobite rebellion, it stages events throughout the year at historic sites in the UK and Europe. Catch them in action this summer at Cannock Chase, Staffordshire, August 19-20 or Towneley Hall, Burnley, September 9-10. lacewars.co.uk

BHT newsletter

You may also like.

- Most Recent

Inside Balmoral Castle - Queen E...

Join us as we take a look at the castle that has always been somewh...

Are these the prettiest streets ...

Are these the prettiest streets in Britain? Get the cameras ready b...

The strict rules King Charles ma...

King Charles is quite particular with his tea...

Rare footage of Queen Elizabeth ...

The Royal Family shared a special video.

The legacy of Queen Victoria and...

The coronation of Queen Victoria took place on June 28, 1838, and s...

Aberdulais Falls - Where the wat...

How Aberdulais, in South Wales weathered a 400-year navigation of ...

Abandoned British ghost towns th...

Have you heard of these British ghost towns?

Did Queen Elizabeth really fall ...

Queen Elizabeth met every American president during her time as Que...

An interview with the costume de...

Ever wondered who's behind the magical costumes of The Crown?

Reenacting the Civil War

Rob Hodge discusses the culture and the lessons of Civil War reenactments. This video is part of the Civil War Trust's In4 video series, which presents short videos on basic Civil War topics. Civil War Trust

The Continental Congress

Women and The Civil War

British Parliament and The American Revolution

You may also like.

13 Secrets of Historical Reenactors

While time travel might be impossible (so far), historical reenactors say their hobby is the next best thing. But what’s it really like to take part in a Revolutionary War battle or to live in a Viking village? How—or why—does one get started as a reenactor? And really, aren’t those shoes uncomfortable? Mental_floss spoke with several historical reenactors to get their insights on what it's like to bring history to life.

1. THEY’RE OFTEN JUST REGULAR PEOPLE—IN CHAIN MAIL.

While some historic reenactors are paid museum employees or professional historians, the majority are people with regular jobs who got inspired by a particular period in history. Some say they got hooked visiting a reenactment village, while others describe a more surprising inspiration. Benjamin Bartgis, a Maryland-based reenactor who specializes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, says it was reading the My Name Is America historic novels in elementary school that got him interested. Jack Garrett, founder of the California-based group the Vikings of Bjornstad, says that for him it was the 1958 movie The Vikings — plus a curiosity about what it would feel like to wear chainmail.

2. IT’S NOT JUST DUDES DOING BATTLE SCENES.

One common assumption about historical reenacting is that it mainly consists of people (usually men) recreating specific battles from history. And while battle reenactments are popular, many reenactors are equally passionate about portraying daily activities. Historic villages, like Colonial Williamsburg, and events like the Jane Austen Festival in Kentucky often showcase reenactors carrying out historic trades, such as cooking, tailoring, and blacksmithing, as well as going about other ordinary aspects of daily life. Such “everyday” reenactments may become even more popular in the future: “Millennials are more interested in everyday life and civilian portrayals” compared to older generations, Bartgis says.

3. THEY DON’T WEAR “COSTUMES.”

Some reenactors will bristle if you call what they’re wearing a “costume.” They refer to the clothing and other physical gear needed to create a historical persona as a “kit,” and lavish a lot of time and labor on making their kits as accurate as possible. Period-appropriate, handmade clothing can also get very expensive, with specialty items such as coats and shoes starting at several hundred dollars.

4. EVEN HISTORICAL REENACTMENT IS SUBJECT TO TRENDS.

As with a lot of things, pop culture influences which reenactment eras and activities are popular at any given moment. The release of a smash book, movie, or video game can cause a surge in popularity; WWI and WWII video games have particularly boosted reenactments of those eras in the past few years. Historical anniversaries—like key dates in the Civil War or American Revolution—can also spark a flurry of renewed interest and commemorations.

5. THEY HONE HISTORICAL SKILLS.

Jack Garrett

It’s not just about dressing the part: Reenactors also practice the skills of an earlier era. Albert Roberts, a reenactor who portrays physicians in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, jokes that when he began he didn’t have any practical 18th century skills at all. “I couldn’t hunt, I couldn’t fish, I couldn’t soldier, I couldn’t ride horses, I couldn’t blacksmith, I couldn’t carpenter, I couldn’t birth babies,” he says, “so I had no value.” But after assisting, and then taking over, for the doctor at historic Mansker’s Station in Goodlettsville, Tennessee, he now has a deep knowledge of old medical techniques.

Bartgis, in addition to mastering Colonial penmanship and bookbinding for his 18th century persona, also has a basic grasp of sailing skills for his work with Ship’s Company, a living history organization dedicated to preserving late 18th and early 19th century maritime history.

Plus, many reenactors also have significant craft skills. Garrett notes that his group crafts most of their Viking gear, aside from speciality items like helmets. They even created their own Viking treasure hoard by molding and casting ancient coins.

6. THEY ARE HISTORIANS.

Most reenactors spend countless hours delving into the history of their preferred era and becoming knowledgeable specialists. Steve Santucci, the adjutant (military secretary) for Revolutionary War group the 2nd New Jersey Regiment , tells mental_floss: “the amount of time spent on the field is quadrupled by the time we spend researching.” He refers to the battles themselves, which are fought as much as possible in the same places they originally occurred, as “walking in the footsteps of history.”

But while reenactors pride themselves on their scholarship, there can be some guesswork involved, especially for particularly ancient or less well-documented eras. Garrett (whose own library numbers 700 volumes) says researching 9th through 11th century Vikings often requires testing equipment and theories in order to connect random dots. “A good deal of what we do is what we call ‘experimental archaeology,’” he says, explaining that he will often take information from archaeological sources—like ancient carvings depicting Vikings carrying their swords a particular way—and test it out.

7. THEY GET ASKED SILLY QUESTIONS.

Members of the public seem to love to ask reenactors the same kinds of questions . Among the queries they get tired of hearing: “Are you going to eat that?” (referring to food they’re cooking); “Aren’t you hot?” (referring to period clothing); and “Is that real fire?” (this one seems hard to explain). And inevitably there’s the smart aleck school kid who will ask where they’re hiding their TV.

8. THEY LIKE TO SHARE THEIR KNOWLEDGE.

Bartgis is quick to say that educating the public is one of the best things about being a reenactor. “As much as we like to make fun of questions like [the above], they’re all valid,” Roberts adds. “We’ve done all this research so we’ll have this knowledge that we can pass on to the public.”

Garrett agrees. “It’s very rewarding,” he says. “Nothing makes you feel better about doing this than the smile of someone who may have a different understanding of history.” For instance, he particularly enjoys combating the image of Vikings as “wild, uncouth barbarians intent only on rape, pillage, and slaughter.”

“Without sugar-coating the realities of the Viking age, we try to put that in the context of their times and overlay the image with descriptions of their art, culture, religion and technology,” he explains. “What’s the most common artifact found buried with Vikings? A comb.”

9. THEY DON’T ALWAYS REENACT FOR THE PUBLIC.

As much as they like interacting with the public, reenactors will sometimes stage separate events for themselves. Bartgis describes taking part in a 15-mile overnight march in single digit temperatures as part of a reenactment of the 1777 Occupation of the Jerseys (part of the Revolutionary War). Besides the reenactors’ own enjoyment, the immersive event was staged for museum educators and professionals to enhance their understanding.

But sometimes reenactors will plan private events just for fun. Garrett’s Bjornstad crew convenes with other Viking reenactment groups at a twice-yearly feast held at a historically accurate longfort in Missouri.

10. IT CAN GET CLIQUE-Y.

Asked about the worst part of reenacting, Roberts says it’s the cliques. Reenactors often split themselves up according to their degree of commitment to accuracy and in opposition to the much-maligned, less accurate “farbs” (sometimes said to stand for “far be it from authentic”). Likewise, some professionals working at museums and historic villages take offense as being called “reenactors,” preferring instead the term “living historians.”

“The thing is, if you don’t encourage and educate the farbs, your hobby dies,” Roberts says, noting the need to educate new blood.

11. THEY MIGHT WEAR BREECHES TO THE GROCERY STORE.

“You really know that you’re a reenactor when your reenactor clothes make their way into your modern wardrobe,” Roberts says, explaining that he once wore his 18th century stockings to school, under his pants, because he had no clean socks. “Nobody knew but me, but I was like ‘I may have a legitimate problem.’”

“If you do this for a while,” Bartgis adds, “you end up going and doing grocery shopping in your old-timey clothes ... or putting gas in your car while wearing breeches and stockings and a wig.” He also says that he and his partner have flown on a plane in their kits, and sometimes ended up in a bar kitted up after an event—to the delight of the bartender and patrons.

12. IT’S A CHANCE TO ESCAPE THE EVERYDAY.

Reenactors say they love the chance their hobby offers to get out of the daily grind. Bartgis says the many magic moments he’s experienced are exemplified by “working with a bunch of people to haul a cannon up a hill, while someone is singing a work song, and you’re all pulling together—or coming together on a sail boat that’s under a full press of sail.”

According to Garrett, “The thing that connects all of us is that for a moment it’s nice to get out of traffic and the normal day to day stuff that we all deal with, and just do something different. ”

13. THEY DON’T WANT TO LIVE IN THE PAST.

Most reenactors, while drawn to the past, are happy enough to be living in the modern era. Asked if they’d like to live in the time periods they reenact, the answer is typically a resounding “No!”

“Intestinal parasites and fleas,” says Garrett. “Dysentery and smallpox,” says Santucci. “I like my modern medicine,” says Roberts.

However, Bartgis notes that while studying the past has made him more appreciative of the present, he’s also been able to recognize that many other things have not changed much. “People have been arguing about what kind of country this country should be since the Revolution,” he says. Also, “people have been struggling to make ends meet for a really long time.” He adds that his perspective on the tenuousness of life in the past has given him “a lot of perspective about how we take modern stability for granted.”

All images via Getty except where noted.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Educating in history: thinking historically through historical reenactment.

1. Introduction: Historical Reenactment: Definition, Objectives, Characteristics, and Methods

- show the importance of historical reenactment as an educational tool.

- identify the relation between historical thinking and historical reenactment.

- analyze the presence of second-order concepts in reenactment practices.

2. Discussion

2.1. developing historical thinking through historical reenactment.

“In the 1970s, the term ‘public history’ gradually became acknowledged as a historical sub-discipline. Public history became institutionalized with the founding of graduate programmes, specific journals, and associations. [...]”

“As the observer of the past is always situated in a present which influences his/her view of the past, historical thinking is also about building an understanding of and reflecting on the complex relationship between past, present, and future. […] In formal history education at secondary schools, historical thinking has increasingly been adopted as the main aim of the school subject. In the history curricula of provinces, states, and countries such as British Columbia (Canada), California (United States), Flanders (Belgium), the Netherlands, Sweden, England, and Finland, historical thinking and historical reasoning occupy the centre stage (see particularly the related chapters in Metzger and Harris 2018)”. ( Grever and Nieuwenhuyse 2020, pp. 487–89 )

“Against these criticisms, scholars with a more social-constructionist approach have ventured that the essentialist distinction between authentic and inauthentic is untenable [...] Reenactment may have a genuine investigative dimension in which the quest for authenticity is not solely about dramatising an already well-known past but generating new knowledge through the activity itself (Crang 1996, pp. 419–20; Cook 2004, pp. 487–88)”. ( Brædder et al. 2017, pp. 172–73 )

2.2. Socializing Knowledge through Historical Reenactment and Its Didactic Use

2.3. some examples of historical reenactment worldwide, 2.4. the metaconcepts of history instruction, the key for historical reenactment.

“An all-encompassing, yet in-depth view of not only change processes but also of diverse and sometimes opposing forces that have led to these changes, and of resistance and continuity factors, as well as the meaning of these series of changes and the very nature of change in history”. ( Paricio Royo 2018, p. 236 )

3. Final Reflections and Conclusions

Author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Agnew, Vanessa. 2004. Introduction: What is reenactment? Criticism 46: 327–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Agnew, Vanessa. 2007. History’s affective turn: Historical reenactment and its work in the present. Rethinking History 11: 299–312. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Agnew, Vanessa, and Juliane Tomann. 2019. Authenticity. In The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies . Edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb and J. Tomann. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, chp. 3. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anderson, J. 1984. Times Machines: The World of Living History . Nashville: Amer Assn for State & Local. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aquillué Domínguez, Daniel. 2019. La recreación histórica y las asociaciones culturales de recreación histórica en Aragón. In El Recreacionismo Histórico, el Patrimonio y la Arqueología Como Motores del Turismo en el Territorio . Edited by Marisancho S. Menjón, E. Val, I. Lasobras and A. Celma. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, pp. 45–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arcega Morales, Jesús Ángel. 2018. Las recreaciones históricas en Aragón. Un teatro en auge. Sigma 27: 147–70. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Balbás, Yeyo. 2019. Recreación histórica del alto Medievo: Esclareciendo una época oscura. HER&MUS 20: 70–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bardavio, Antoni, and Paloma González Marcén. 2003. Objetos en el Tiempo. Las Fuentes Materiales en la Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales . Barcelona: Horsoi Editorial. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barton, Keith. C. 2017. Shared Principles in History and Social Science Education. In Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education . London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 449–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brædder, Anne. 2019. Expertise and amateurism. In The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies . Edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb and J. Tomann. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, chp. 14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brædder, Anne, Kim Esmark, Tove Kruse, Carsten Tage Nielsen, and Anette Warring. 2017. Doing pasts: Authenticity from the reenactors’ perspective. Rethinking History 21: 171–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cardona Gómez, Gemma, and María Feliu Torruella. 2014. Arqueología, vivencia y comprensión del pasado. Iber: Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 78: 15–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carneiro, Maria João, Celeste Eusébio, Ana Caldeira, and Ana Cláudia Santos. 2019. The influence of eventscape on emotions, satisfaction and loyalty: The case of re-enactment events. International Journal of Hospitality Management 82: 112–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cavanna, Floriano, Laura Jiménez Martínez, and Noé Valtierra Pereiro. 2021. Reconstrucción histórica. Algunas experiencias en historia pública y educación reglada. In Recreación Histórica y Didáctica del Patrimonio. Nuevos Horizontes para un Cambio de Modelo en la Difusión del Pasado . Edited by Dario Español Solana and Jesús G. Franco-Calvo. Gijón: Trea, pp. 30–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chaparro Sainz, Álvaro, María del Mar Felices de la Fuente, and Laura Triviño Cabrera. 2020. La investigación en pensamiento histórico. Un estudio a través de las tesis doctorales de Ciencias Sociales (1995–2020). Panta Rei. Revista digital de Historia y Didáctica de la Historia 14: 93–147. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cook, Alexander. 2004. The Use and Abuse of Historical Reenactment: Thoughts on Recent Trends in Public History. Criticism 46: 487–96. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Corral Lafuente, José Luis. 2019. Origen del recreacionismo histórico y el rigor como esencia de la consolidación. In El recreacionismo Histórico, el Patrimonio y la Arqueología Como Motores del Turismo en el Territorio . Edited by Marisancho S. Menjón, E. Val, I. Lasobras and A. Celma. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, pp. 27–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cózar Llistó, Guillermo. 2013. La recreación histórica en España. Definición, caracterización y perspectivas de aplicación. Glyphos Revista de Arqueología 2: 6–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Certau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life . Berkley: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Del Barco Díaz, Miguel. 2010. La recreación histórica como medio para la divulgación de la historia. In La Divulgación de la Historia y Otros Estudios Sobre Extremadura . Edited by Félix Iñesta Mena. Llerena: Sociedad Extremeña de Historia, pp. 243–54. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Paz Sánchez, José Juan, and Mario Ferreras Listán. 2010. La recreación histórica en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en las ciencias sociales: Metodología, buenas prácticas y desarrollo profesional. In Metodología de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales . Edited by Rosa M. Ávila, M. P. Rivero and Pedro L. Domínguez. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, pp. 525–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Domínguez Castillo, José. 2015. Pensamiento Histórico y Evaluación de Competencias . Barcelona: Graó. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doñate Campos, Olga, and Carmen Ferrete Sarria. 2019. Vivir la Historia: Posibilidades de la empatía histórica para motivar al alumnado y lograr la comprensión efectiva de los hechos históricos. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 36: 47–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- d’Oro, Giuseppina. 2004. Re-Enactment and Radical Interpretation. History and Theory 43: 198–208. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Egberts, Linde. 2014. Battlefield of Histories. In Companion to European Heritage Revivals . Cham: Springer, pp. 53–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Egea Vivancos, Alejandro, and Laura Arias Ferrer. 2018. El desafío de enseñar a pensar históricamente a través de la arqueología. In Y la Arqueología Llegó al Aula . Edited by Alejandro Egea, Laura Arias and Joan Santacana. Gijón: Ediciones TREA, pp. 329–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Endacott, Jason L., and Sarah Brooks. 2018. Historical Empathy: Perspectives and Responding to the Past. In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning . Edited by Scott Alan Metzger and Lauren McArthur Harris. Medford: Wiley, pp. 203–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Español-Solana, Darío. 2019a. Los distintos modelos de recreación histórica; hacia la consolidación de una industria cultural en el siglo XXI. In El Recreacionismo Histórico, el Patrimonio y la Arqueología Como Motores del Turismo en el Territorio . Edited by Marisancho S. Menjón, E. Val, I. Lasobras and A. Celma. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, pp. 11–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Español-Solana, Darío. 2019b. Historia para todos: Recreación histórica, didáctica y democratización del conocimiento. HER&MUS 20: 7–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Español-Solana, Darío. 2019c. New perspectives for the dissemination of medieval history: Re-enactment in southern Europe, a view from the perspective of didactics. Imago Temporis. Medium Aevum 13: 333–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Español-Solana, Darío. 2021. Historia y Cultura Militar Durante la Expansión Feudal en el valle del Ebro, Siglos XI y XII. Presupuestos Metodológicos para una Didáctica de la Guerra en la Edad Media. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain. [ Google Scholar ]

- Español-Solana, Darío, and Jesús Gerardo Franco-Calvo. 2021a. Education and Heritage of Medieval Warfare. A Study on the Transmission of Knowledge by Informal Educators in Defensive Spaces. Education Sciences 11: 320. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Español-Solana, Darío, and Jesús Gerardo Franco-Calvo. 2021b. Recreación Histórica y Didáctica del Patrimonio. Nuevos Horizontes Para un Cambio de Modelo en la Difusión del Pasado . Gijón: TREA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Español-Solana, Darío, Jesús Gerardo Franco-Calvo, and José-Manuel González-González. 2020. Recreaciones y conmemoraciones históricas, diferencias y posibilidades didácticas desde Aragón (España). Didattica della Storia 2: 413–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Felices de la Fuente, María del. Mar, and Julia Hernández Salmerón. 2019. La recreación histórica como recurso didáctico: Usos y propuestas para el aula. HER&MUS 20: 7–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fontal, Olaia. 2008. La importancia de la dimensión humana en la didáctica del patrimonio. In La comunicación Global del patrimonio Cultural . Edited by S. Mateos. Gijón: TREA, pp. 53–109. [ Google Scholar ]

- Franco-Calvo, Jesús Gerardo, Antonio Hernández Pardos, and Jesús Javier Jambrina Campos. 2020. Una forma didáctica de acercarnos al patrimonio: La recreación histórica «Peracense siglo XIII». HER&MUS 20: 85–101. [ Google Scholar ]

- Franco-Calvo, Jesús Gerardo. 2021. Pensar históricamente a través de la recreación histórica. El caso del castillo de Peracense. In Recreación Histórica y Didáctica del Patrimonio. Nuevos Horizontes para un Cambio de Modelo en la Difusión del Pasado . Edited by Darío Español Solana and Jesús Gerardo Franco-Calvo. Gijón: Trea, pp. 175–203. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gardner, Howard. 1993. Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice . Nueva York: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goering, Christian Z., and Bradley J. Burenheide. 2010. Exploring the Role of Music in Secondary English and History Classrooms through Personal Practical Theory. SRATE Journal 19: 44–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gómez Carrasco, Cosme Jesús, Jorge Ortuño Molina, and Sebastián Molina Puche. 2014. Aprender a pensar históricamente. Retos para la historia en el siglo XXI. Revista Tempo e Argumento 6: 5–27. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gómez, Cosme Jesús, and Arthur Chapman. 2016. Pensamiento histórico y evaluación de competencias en el currículum inglés y español. Un estudio comparativo. In Actas del VII Simposio Internacional de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales en el ámbito Iberoamericano . Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, pp. 433–45. [ Google Scholar ]

- González Monfort, Neus, Rodrigo Henriquez Vazquez, Joan Pagès Blanch, and Antoni Santisteban Fernández. 2009. El aprendizaje de la empatía histórica (EH) en educación secundaria: Análisis y proyecciones de una investigación sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del conflicto y la convivencia en la Edad Media. In Un progetto Educativo per la «Strategia di Lisbona . Edited by Rosa M. Ávila Ruiz, Beatrice Borghi and Ivo Mattozzi. Bologna: Pàtron Editore, pp. 283–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grever, Maria, and Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse. 2020. Popular uses of violent pasts and historical thinking. Journal for the Study of Education and Development 43: 483–502. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Handler, Richard, and William Saxton. 1988. Dyssimulation: Reflexivity, Narrative, and the Quest for Authenticity in “Living History”. Cultural Anthropology 3: 242–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hernàndez Cardona, Francisco Xavier. 2001. Los juegos de simulación y la didáctica de la historia. Íber. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 30: 23–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ishee, Nell, and Jeanne Goldhaber. 1990. Story Re-Enactment: Let the Play Begin! Young Children 45: 70–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jardón Giner, Paula, and Clara Isabel Pérez Herrero. 2019. La reconstrucción dramatizada en espacios arqueológicos: Interacciones en yacimientos valencianos. HER&MUS 20: 24–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez Torregrosa, Lorena, and María del Carmen Rojo Ariza. 2014. Recreación histórica y didáctica. Iber: Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 78: 35–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kneebone, Roger, and Abigail Woods. 2014. Recapturing the history of surgical practice through simulation-based re-enactment. Medical History 58: 106–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lévesque, Stephane. 2009. Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the Twenty-First Century . Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- López Cruz, Inmaculada, and José María Cuenca López. 2014. El patrimonio y las personas: Símbolos e identidad cultural como elementos claves para la educación. In Reflexionar Desde las Experiencias. Una visión Complementaria Entre España, Francia y Brasil. Actas del II Congreso Internacional de Educación Patrimonial . Edited by Olaia Fontal, Alex Ibáñez and Lorenzo Martín. Madrid: IPCE/OEPE, pp. 1161–71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meylan, Karine. 2013. From research to mediation. A perspective for experimental archaeology. Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa Bilanz 12: 171–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Motos Teruel, Tomás, and Antoni Navarro Amorós. 2003. El paper de la dramatització en el currículum. Articles: Revista de Didáctica de la Llengua i de la Literatura 29: 10–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paricio Royo, Javier. 2018. El valor de la historia. Estudio de alternativas curriculares en Secundaria (1): Una visión integrada de las transformaciones (cambio/continuidad) que conducen y modelan el presente (conciencia histórica). Clío: History and History Teaching 4: 232–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paricio Royo, Javier. 2019. El valor de la historia. Estudio de alternativas curriculares en Secundaria (2): Aprender sobre la alteridad y la naturaleza humana a través de la empatía o toma de perspectiva histórica. Clío: History and History Teaching 45: 330–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paricio Royo, Javier. 2020. El valor de la historia. Estudio de alternativas curriculares en Secundaria (3): Aprender a pensar desde múltiples perspectivas. Clío: History and History Teaching 46: 202–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Plá, Sebastián. 2005. Aprender a Pensar Históricamente. La Escritura de la Historia en el Bachillerato . México: Plaza y Valdés. [ Google Scholar ]

- Retz, Tyson. 2018. Empathy and History: Historical Understanding in Re-Enactment, Hermeneutics and Education . New York City: Berghahn. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rivero Gracia, María Pilar, and Julián Pelegrín Campo. 2015. Aprender historia desde la empatía. Experiencias en Aragón. Aula de Innovación Educativa 240: 18–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rivero Gracia, María Pilar, and Julián Pelegrín Campo. 2019. ¿Qué Historia consideran relevante los futuros docentes de Educación Infantil? Cadernos de Pesquisa 49: 96–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson, Jessica, and Hillary Yerbury. 2015. Re-enactment and its information practices; tensions between the individual and the collective. Journal of Documentation 71: 591–608. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodríguez-Medina, Jairo, Cosme Jesús Gómez-Carrasco, Ramón López-Facal, and Pedro Miralles-Martínez. 2020. Tendencias emergentes en la producción académica de educación histórica. Revista de Educación 389: 211–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rojas Rabaneda, Antonio. 2019. La recreación histórica en Cataluña como recurso de la socialización del conocimiento. HER&MUS 20: 123–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rüsen, Jörn. 2005. History: Narration, Interpretation, Orientation . Nueva York: Berghahn Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Samida, Stephanie. 2019. Material culture. In The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies . Edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb and J. Tomann. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, chp. 26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandwell, Ruth, and Amy von Heyking. 2014. Becoming a History Teacher: Sustaining Practices in Historical Thinking and Knowing . Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Santisteban, Antoni, Alfredo Gomes, and Edda Sant. 2021. El currículum de historia en Inglaterra, Portugal y España: Contextos diferentes y problemas comunes. Educar em Revista 37: 1–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Santisteban Fernández, Antoni. 2010. La formación de competencias de pensamiento histórico. Clío & Asociados 14: 34–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Scanlan, Emma. 2017. Reimagining National Identity through Reenactment in the Pacific and Australia. Wasafiri 32: 60–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sebares Valle, Gemma. 2017. Recreación histórica y educación: El caso de Tarragona como gran espacio patrimonial. Iber: Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 89: 66–71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Seixas, Peter, and Tom Morton. 2013. The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts . Toronto: Nelson College Indigenous. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shaw, Emma. 2021. Historical thinking and family historians: Renovating the house of history? Historical Encounters 8: 83–96. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sheffield, Caroline C., and Stephen B. Swan. 2012. Digital Reenactments: Using Green Screen Technology to Recreate the Past. Social Education 76: 92–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Solé, Gloria. 2019. A «história ao vivo»: Recriação histórica de uma feira medieval no castelo de Lindoso em Portugal. HER&MUS 20: 102–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soria López, Gabriela Margarita. 2015. El pensamiento histórico en la educación primaria: Estudio de casos a partir de narraciones históricas. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 14: 83–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stueber, Karsten R. 2002. The psychological basis of historical explanation: Reenactment, simulation, and the fusion of horizons. History and Theory 41: 25–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thelen, David. 2003. Learning from the past: Individual experience and re-enactment. The Indiana Magazine of History 99: 155–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- Turner, Thomas N. 1985. Historical Reenactment—Can it Work as a Standard Tool of the Social Studies? The Social Studies 76: 220–23. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Van der Plaetsen, Peter. 2014. When the Past Comes to Life. In Companion to European Heritage Revivals . Edited by Linde Egberts and Koos Bosma. Cham: Springer, pp. 151–67. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wineburg, Sam. 2018. Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone) . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

González-González, J.-M.; Franco-Calvo, J.-G.; Español-Solana, D. Educating in History: Thinking Historically through Historical Reenactment. Soc. Sci. 2022 , 11 , 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060256

González-González J-M, Franco-Calvo J-G, Español-Solana D. Educating in History: Thinking Historically through Historical Reenactment. Social Sciences . 2022; 11(6):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060256

González-González, José-Manuel, Jesús-Gerardo Franco-Calvo, and Darío Español-Solana. 2022. "Educating in History: Thinking Historically through Historical Reenactment" Social Sciences 11, no. 6: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060256

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Emerging Revolutionary War Era

Offering engaging perspectives on the Revolutionary War Era

The First Re-enactment?

We often think of re-enacting as a modern phenomenon. Those of us familiar with the hobby can attest that re-enacting has evolved greatly since the 1960s and 70s. In those decades participants often made their own clothing and accoutrements, with varying degrees of accuracy. It was not uncommon to see jeans and modern military gear mixed in with poor copies of historic clothing.

Today there is a thriving reenactment community and an industry to support it. Various suppliers offer reproduction clothing, weapons, gear, camping supplies, food, and every imaginable item for nearly every time period.

Yet the roots of reenacting to back earlier than most might suspect. In fact reenactments were held during the American Revolution. The occasions were combinations of training exercises and patriotic celebrations. What follows are descriptions of early reenactments held during the war.

In September, 1778, the Continental Army was camped near Fredericksburg, NY. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Dearborn of the 1st New Hampshire wrote, “Our men had a Gill of Rum Extra to Day on account of its being the annivercery of the Glorious victory Obtained over the British army at bemus Heights- & the Officers in General had a Meeting at Evning had a social Drink & gave several toasts suitable for the Occasion- & our men had a Grand sham fight.” This, was, perhaps, the first battle re-enactment in American history. Unfortunately there are no details of this ‘sham fight.’

During the second Morristown encampment in New Jersey an even larger re-enactment was held by the army on May 29, 1780. There seems to have been nothing else like it, either before or since, during the conflict. Several participant’s accounts give good details, and unlike in many battle accounts, they all agree! Lieutenant Colonel Josiah Harmar of Pennsylvania wrote of this dusty and hot day, “Several Manouvers perform’d this day in presence of the Honble Comitte of Congress, the firings with black cartridges well executed.”

It was a dusty and hot day, recalled Ensign Jeremiah Greenman of Rhode Island. He wrote, “This day 4 Battalion paraded & went to Morris Town where they fired 14 rounds of cartridges & saluted the Committee of Congress which was here on business, settling the affairs of the army.”

Dr. James Thacher of Jackson’s Additional Massachusetts Regiment also wrote “4 Battalions of our troops were paraded for review by the committee of Congress, in the presence of Gen Washington, they were duly honored with the military salute.”

Lieutenant Ellias Parker of the artillery wrote of a “Review and sham fight to day by the Committee from Congress the maneuvers were performed exceedingly well by 4 battalions- I was ordered to & took the command of a 3 pounder on the Left of the 3rd Battalion- after which we had done maneuvering all the officers go to Col Abeals where we get a plenty of Grog .. the soldiers are all furnished with rum.”

Private Joseph Plumb Martin of the 8th Connecticut wrote, “About this time there were about 3,000 men ordered out for a particular field day, for the Prussian Gen Von Steuben to exercise his maneuvering … We marched off our regimental parades at dawn of day, and went 3 or 4 miles to Morristown, to a fine plain, where we performed a variety of military evolutions. We were furnished with a plenty of blank cartridges, had 8 or 10 field pieces, and made a great noise, if nothing more. About 1 or 2 o’clock we ceased, and were supplied with a gill of rum each. Having had nothing to eat since the night before, the liquor took violent hold . . .”

Captain Samuel Richards of the 3rd Connecticut wrote, “On one fine day the army which then consisted of about 11,000 was paraded and divided into 2 separate bodies, one occupying a small hill and the other moved on to attack them. In this sham fight the various maneuverings common in a real battle were acted over.”

Richards concludes with, “After the assailants had continued the attack for some time the reserves came up which turned the battle in their favor. The usual shouting of the victors ensued, while the defeated retreated. The victor then took possession of the hill and pitched their tents on the battle ground.”

Lieutenant Ekuries Beatty of the 4th Pennsylvania was not present but heard the racket: “I now hear a very heavy firing of cannon and musketry which is 4 battalions maneuvering at Morristown before Marquis de Lafyette and I am very sorry I had not the chance of seeing them.”

The soldiers used blank cartridges: powder only, without ball, for these sham battles. This was not only for safety, but to preserve precious lead. Were the reenactments valuable for training? Most accounts don’t reference the experiences being helpful in real combat. Interestingly these ‘sham battles’ as they were called, were not done by armies in the Civil War.

When the Revolution began to be commemorated a century later, sometimes ‘sham battles’ or pageants were held. Wildly popular in the early 1900s, they were planned more for dramatic effect than accuracy. Although many battles have been re-enacted, the Morristown re-enactment of 1780 has yet to be re-enacted.

In 1802 a sham battle was fought at Bennington, Vermont to commemorate the American victory of 1777. What makes this and other early battle re-enactments noteworthy is that Revolutionary War veterans, revered and celebrated as living connections to the conflict, actually would have been on hand.

Re-enactment proved to have practical value in the War of 1812. At Fort Meigs, Ohio in 1813, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh used a sham battle to draw the American defenders out of the fort. It was hoped they would be lured out by thinking that reinforcements were coming. The ruse failed it but was unorthodox.