A systematic review of literature on Human capital investment and its significance for human resource development

- Original Article

- Published: 06 July 2023

- Volume 14 , pages 1810–1826, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Lawrence Arokiasamy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1544-1725 1 ,

- Takemi Fujikawa 2 ,

- Shishi Kumar Piaralal 3 &

- Thilageswary Arumugam 4

779 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

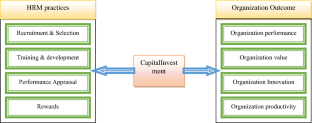

With rising globalization and the overcrowding of the employment market as a result of the recent crisis in numerous economies throughout the world, human capital is receiving more attention. To hasten economic progress by investing the necessary time and effort, both industrialized and emerging nations lay a higher focus on human capital development. Building human capital is therefore the crucial way to participate on the international stage. Companies should invest the essential resources in increasing human capital since it has a big impact on performance. From several critical viewpoints, this research investigates the level where human capital has straight implications on corporate performance. This study also aims to examine 60 publications that are concerned with human capital. A thorough assessment of the sequential review based on the year of each publication is also provided in this paper. Also, each study paper’s evaluation is exposed. This study also focused on and reviews the topic knowledge utilizing a systematic literature review. Eventually, a model explaining the connection among human capital as well as company performance is developed in this work. The finding of the study reveal the impact of human capital on corporate performance and the value of a strong workplace and human resources in enhancing job performance. Human Resource Management (HRM) practices that link employee engagement in the organization.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Perspectives on Human Capital Initiatives

Understanding the Relationship Between Intellectual Capital and Organizational Performance: The Role of e-HRM and Performance Pay

Human Resource Practices and Employee Performance in Indian IT Industry: An Empirical Study of Selected IT Companies

Ajisafe RA, Orifa RA, Balogun JA (2015) Influence of human capital management on organisational performance. J Resour 3:886

Google Scholar

Abraham S (2012) Development of employee engagement programme on the basis of employee satisfaction survey. J Econ Dev Manag IT Finance Mark 4(1):27–37

Arvanitis S, Loukis EN (2009) Information and communication technologies, human capital, workplace organization and labour productivity: a comparative study based on firm-level data for Greece and Switzerland. Inf Econ Policy 21(1):43–61

Ibeh ChijinduJS, G,. O &, Emerole G, .A (2016) Effect of human capital development programmes in optimizing employees productivity: a study of Abia State House of Assembly, Nigeria. Singaporean J Bus Econ Manage Stud 5(4):1–12

Corvers F (1997) The impact of human capital on labour productivity in manufacturing sectors of the European Union. Appl Econ 29(8):975–987

Currie J, Almond D (2011) Human capital development before age five. Handbook of labor economics, vol 4. Elsevier, pp 1315–1486

Namasivayam K, Denizci B (2006) Human capital in service organizations: identifying value drivers. J Intellect Capital 7(3):381–393

Becker GS (2002) The age of human capital. Education in the Twenty-First Century, 3–8

Becker GS (1996) The economic way of looking at behavior: the noble lecture. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, California

Schultz TW (1961) Investment in human capital. Am Econ Rev 51(1):1–17

DiBernardino F (2011) The missing link: measuring and managing financial performance of the human capital investment. People Strat 34(2):44

Burund S, Tumolo S (2004) Leveraging the new human capital: adaptive strategies, results achieved, and stories of transformation. Nicolas Brealey America, Boston, USA

Daft RL (2015) Organization theory and design. Cengage learning, London

Nerdrum L, Erikson T (2001) Intellectual capital: a human capital perspective. J Intellect Capital 2(2):127–135

Thomas D, kapplman A, Richards C (1996) Training empowerment and creating a culture for change. Empow Organ 4:26–29

Çalişkan EN (2010) The impact of strategic human resource management on organizational performance. J Naval Sci Eng 6(2):100–116

Armstrong M, Brown D (2019) Strategic Human Resource Management: back to the future. Institute for Employment Studies reports, pp 1–36

Zeithmal VA, Berry LL, Parasuraman BA (1996) The behavioral consequences of service quality. J Mark 60:31–46

Gonzalez JV, Garazo TG (2006) Structural relationships between organizational service orientation, contact employee job satisfaction, and citizenship behavior. Int J Serv Ind Manag 17(1):23–50

Bapna R, Langer N, Mehra A, Gopal R, Gupta A (2013) Human capital investments and employee performance: an analysis of IT services industry. Manage Sci 59(3):641–658

Wei YC (2014) The benefits of organizational citizenship behavior for job performance and the moderating role of human capital. Int J Bus Manag 9(7):87

Jain S, Ahuja SK (2019) Impact of human capital management practices on employee job performance. In: Proceedings of 10th International Conference on Digital Strategies for Organizational Success

Imran R, Atiya TMS (2020) The role of high-performance work system and human capital in enhancing job performance. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development

Zeb A, Abdullah NH, Javaid M (2018) July. Impact of human capital management practices on employees’ job performance. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol 1049, No 1, p 012020. IOP Publishing

Huang SS, Yu Z, Shao Y, Yu M, Li Z (2020) Relative effects of human capital, social capital and psychological capital on hotel employees’ job performance. In: International journal of contemporary hospitality management

Guo W, Xiao H, Yang X (2012) An empirical research on the correlation between human capital and career success of knowledge workers in enterprise. Phys Procedia 25:715–725

Lyons FW, Akroyd D (2014) The impact of human capital and selected job rewards on community college faculty job satisfaction. Community Coll J Res Pract 38(2–3):194–207

Yaya JA (2016) The effect of human capital development on job satisfaction of librarians in public universities in Nigeria. Am J Bus Soc 1(3):98–117

Alola UV, Avci T, Ozturen A (2018) Organization sustainability through human resource capital: the impacts of supervisor incivility and self-efficacy. Sustainability 10(8):2610

Cik A, Asdar M, Anwar AI, Efendi S (2021) Impact of training and Learning Organization on Employee competence and its implication on job satisfaction and employee performance of Bank in Indonesia. J Psychol Educ 58(1):140–156

Murray R (2016) Human capital and employee attitudes: an investigation of the antecedents of job satisfaction through organizational support and person-organization fit theory. California State University, Fullerton

Alola UV, Alafeshat R (2021) The impact of human resource practices on employee engagement in the airline industry. J Public Affairs 21(1):e2135

Osibanjo A, Adeniji A, Salau O, Atolagbe T, Osoko A, Edewor O, Olowu J (2020) Bolstering human capital management and engagement in the health sectors. Cog Bus Manag 7(1):1794676

Witasari J, Gustomo A (2020) Understanding the effect of human capital management practices, psychological capital, and employee engagement to employee performances. Asian J Technol Manage 13(1):1–15

Al-Sufyani AM, Al-Ameri AQF (2021) Impact of administrative empowerment on Organizational Commitment: a case study of Taj Sheba Hotel in Yemen. 7(16):574–603

Sivasubramanian M Employee Retention Practices for Human Capital and its effectiveness on Financial Performance in Banking Industry* D. Kannan

Bibi P, Ahmad A, Majid AH (2018) HRM practices and employee retention: the moderating effect of work environment. Applying partial least squares in tourism and hospitality research. Emerald Publishing Limited

Nasir J, Ibrahim RM, Sarwar MA, Sabir RI, Nawaz F (2020) Impact of high involvement work practices on employee performances in health sector, Pakistan. In: The Journal of Management Theory and Practice (JMTP), pp 22–32

Gulzar S, Advani A, Jalees T (2017) Impact of performance appraisal on employee retention: a study on banking sector of Pakistan. J Independent Stud Res Manag Soc Sci Econ 15(1):890

Madhumathy Sakthivel DGD (2022) Impact of Human Capital Management on Employee Retention in Automobile Industry with special reference to selected companies in Bengaluru. J Posit School Psychol 6(2):643–669

Bhattacharya M, Harold Doty D, Garavan T (2014) The organizational context and performance implications of human capital investment variability. Hum Res Dev Q 25(1):87–113

Odhon’g EA, Omolo J (2015) Effect of human capital investment on organizational performance of pharmaceutical companies in Kenya. Global J Hum Resource Manage 3(6):1–29

Nawaz T (2019) Exploring the nexus between human capital, corporate governance and performance: evidence from islamic banks. J Bus Ethics 157(2):567–587

Kucharčíková A, Mičiak M, Hitka M (2018) Evaluating the effectiveness of investment in human capital in e-business enterprise in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 10(9):3211

Subramony M, Segers J, Chadwick C, Shyamsunder A (2018) Leadership development practice bundles and organizational performance: the mediating role of human capital and social capital. J Bus Res 83:120–129

Ma C, Jiang Y, Jiang Y (2018) The Effect of Specific Human Capital on Firm Performance Improvement. In: 2018 2nd International Conference on Education, Economics and Management Research (ICEEMR 2018), pp 608–612. Atlantis Press

Tran NP, Vo DH (2020) Human capital efficiency and firm performance across sectors in an emerging market. Cog Bus Manag 7(1):1738832

Vomberg A, Homburg C, Bornemann T (2015) Talented people and strong brands: the contribution of human capital and brand equity to firm value. Strateg Manag J 36(13):2122–2131

Özer G, Çam İ (2016) The role of human capital in firm valuation: an application on BIST, vol 235. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, pp 168–177

Özer G, Çam İ, THE MODERATING EFFECT OF HUMAN CAPITAL ON INNOVATION CAPITAL AND FIRM MARKET VALUE RELATIONSHIP (2017) : AN APPLICATION ON BIST. International Journal of Management Economics & Business/UluslararasiYönetimIktisatveIsletmeDergisi

Toszewska-Czerniej W (2018) Creating value of organization through human capital management. Ekonomia i Prawo Economics and Law 17(4):443–457

Sisodia G, Jadiyappa N, Joseph A (2021) The relationship between human capital and firm value: Evidence from Indian firms. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), p.1954317

Bornay-Barrachina M, De la Rosa‐Navarro D, López‐Cabrales A, Valle‐Cabrera R (2012) Employment relationships and firm innovation: the double role of human capital. Br J Manag 23(2):223–240

Bornay-Barrachina M, López-Cabrales A, Valle-Cabrera R (2017) How do employment relationships enhance firm innovation? The role of human and social capital. Int J Hum resource Manage 28(9):1363–1391

Nieves J, Quintana A (2018) Human resource practices and innovation in the hotel industry: the mediating role of human capital. Tourism and Hospitality Research 18(1):72–83

Liu G, Pang L, Kong D (2017) Effects of human capital on the relationship between export and firm innovation. Chinese Management Studies

Capozza C, Divella M (2019) Human capital and firms’ innovation: evidence from emerging economies. Econ Innov New Technol 28(7):741–757

Backman M (2014) Human capital in firms and regions: impact on firm productivity. Pap Region Sci 93(3):557–575

Hussen MS (2020) Exploring the impact of various typologies of human capital on firms’ productivity. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development

ANOSA IC (2021) Human Capital Development and Organizational Productivity in Selected Manufacturing Firms South-East

Piwowar-Sulej K (2021) Human resources development as an element of sustainable HRM–with the focus on production engineers. J Clean Prod 278:124008

AlHamad A, Alshurideh M, Alomari K, Kurdi B, Alzoubi H, Hamouche S, Al-Hawary S (2022) The effect of electronic human resources management on organizational health of telecommuni-cations companies in Jordan. Int J Data Netw Sci 6(2):429–438

Mansour M (2020) The relationship between human resources management practices and job engagement: the mediating role of psychological capital. Manage Sci Lett 10(13):3047–3056

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Associate Professor, Management and Humanities Department, UniversitiTeknologiPETRONAS, Persiaran UTP, 32610, Seri Iskandar, Perak, Malaysia

Lawrence Arokiasamy

Associate Professor, Faculty of International Studies, OtemonGakuin University, 2 Chome-1-15 Nishiai, Ibaraki, Osaka, 567-8502, Japan

Takemi Fujikawa

Associate Professor and Director, OUM Graduate Centre, Open University Malaysia Kelana Centre Point, Menara OUM, Block C, Jalan SS 7/19, 47301, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Shishi Kumar Piaralal

Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Business, International University Malaya Wales City Campus, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Block A, Ground Floor, Administration Wing, Jalan Tun Ismail, 50480, Kuala Lumpur, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Thilageswary Arumugam

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lawrence Arokiasamy .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest, human and animal rights, informed consent, additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Arokiasamy, L., Fujikawa, T., Piaralal, S.K. et al. A systematic review of literature on Human capital investment and its significance for human resource development. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag 14 , 1810–1826 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-023-01985-2

Download citation

Received : 01 April 2023

Revised : 26 May 2023

Accepted : 10 June 2023

Published : 06 July 2023

Issue Date : October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-023-01985-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Organization performance

- Employee engagement

- Job satisfaction

- Organization productivity

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Data Descriptor

- Open access

- Published: 12 June 2024

A dataset of human capital-weighted population estimates for 185 countries from 1970 to 2100

- Guillaume Marois ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2701-6286 1 , 2 ,

- Jesus Crespo Cuaresma 2 , 3 ,

- Jakob Zellmann 3 &

- Claudia Reiter 2 , 4

Scientific Data volume 11 , Article number: 612 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

466 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Developing world

We provide a novel dataset of human capital-weighted population size (HCWP) for 185 countries from 1970 to 2100. HCWP summarizes a population’s productive capacity and human capital heterogeneity in a single metric, enabling comparisons across countries and over time. The weights are derived from Mincerian earnings functions applied to multi-country census data on educational attainment. The model used to compute the returns to schooling accounts for the diminishing positive relative relationship between education and wages as the overall education of populations rises. The population weights are adjusted by a skills assessment factor representing differences in education quality across countries and years. HCWP is calculated by applying these adjusted human capital weights to population estimates and projections disaggregated by age, sex and education, spanning the period 1970–2020 and 2020–2100 for five Shared Socioeconomic Pathway scenarios. Validation analyses demonstrate the utility of the new HCWP data in explaining national income trends. As a more comprehensive population measure than basic size and age-sex indicators, HCWP enhances the power of statistical models aimed at the assessment of socioeconomic change impacts and forecasting.

Similar content being viewed by others

GEOWEALTH-US: Spatial wealth inequality data for the United States, 1960–2020

Declining population and GDP growth

A simple method for measuring inequality

Background & summary.

This dataset provides human capital weighted population (HCWP) estimates for 185 countries at 5-year intervals, spanning 1970–2020 historically and projected for 2020–2100 under five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways scenarios (SSP1-SSP5) 1 . The HCWP adjusts the working-age population (20–64 years) by weights based on educational attainment and education system quality. It summarizes heterogeneity in human capital in a single indicator. Potential uses include assessing past and future economic impacts of demographic and societal changes, comparing productive capacity across countries and historical periods, and predicting income growth making use of econometric models.

Traditional demographic analyses focus on population size and age-sex structure. Age structure, in particular, is an important economic growth predictor. In the decades after a fertility fall, a demographic dividend can emerge, characterized by a high working-age to dependent population ratio. This period tends to see rapid industrialization, education expansion, and economic growth 2 , 3 , 4 . After some decades under this regime, the elderly share of the population begins rising, bringing population aging and its challenges. The standard narrative is that a higher elderly percentage has negative economic consequences: the retired elderly population produce less but require pensions and healthcare, while the working-age share that provides support and tax revenue shrinks.

Focusing exclusively on changes in the age structure as a predictor of economic growth trends does not provide a complete picture. The ability of the ‘supporting population’ (the working-age) to actually support the ‘dependent population’ depends to a large extent on its education, labour force status and productivity, all of which are also undergoing drastic changes. Econometric models estimated on historical data have shown that the inclusion of information on education and age structure, as well as their interplay, contribute significantly to the explanatory power of statistical specifications aimed at reproducing differences in past income and income per capita trends across countries of the world. In particular, the empirical results indicate that including variables which account for age-structured educational attainment levels in economic growth models are better able to account for innovation and technology adoption phenomena 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 .

The Wittgenstein Centre (WIC) Population Projections provide standardized estimates and projections of population by educational attainment for all countries, spanning 1970–2100. Since working-age individuals have varying productivity, these projections use education as a proxy for human capital to enable more refined analysis of demographic change impacts 8 , 9 , 10 . Education correlates not just with fertility and mortality, but also labor force participation and productivity 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 . For example, WIC projections show India will have a larger working-age population than China in coming decades, but with much lower educational attainment and therefore less productive workers 17 . While only 13% of the working age population in China had post-secondary attainment in 2015, versus 34% in the US, this gap is projected to narrow over time as older, less-educated Chinese cohorts are replaced by more educated ones.

The role played by education as a catalyst of socioeconomic change is not only a matter of quantity but also modulated by education quality. There is ample evidence of differences in the quality of education systems among countries in the world 18 . A high school diploma does not, on average, provide the same human capital, and its effect on productivity may depend on whether it was obtained in a rich country that spends a lot on education or in a low-income country where schools are underfunded 19 .

The human capital-weighted population (HCWP) estimates presented here are calculated by applying weights to the working-age population estimates by educational attainment, which are adjusted by a factor accounting for education system quality. Following an approach similar to other studies 20 , 21 , education-specific weights are calculated utilizing a Mincerian earnings function 22 on pooled data from all IPUMS-I censuses containing education and income information. The education parameters are interacted with the countries’ average educational attainment to account for the dependence of returns to education on the number of workers sharing that education level. Country and time specific adjustment factors for education quality are derived from skills assessment surveys. These final adjusted weights are then applied to population estimates and projections from the Wittgenstein Centre Data Explorer, spanning 1970–2015 historically and projected to 2100 under five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways scenarios (SSP1-SSP5).

We validate our estimates making use of an out-of-sample prediction exercise for GDP per capita growth applied to a panel dataset covering all countries of the world for which data are available. In this exercise, we estimate alternative regression specifications for the growth rate of GDP per capita based on Crespo Cuaresma 5 and compute several prediction error statistics for the period 2000–2015 (in 5-year steps). In particular, we entertain three different econometric models: a benchmark specification where labor input is measured based on population figures, a second one which includes population by educational attainment level and a third model based on HCWP. Our results indicate that the predictive ability of the model based on HCWP is similar to that of the model based on educational attainment when measured using the global sample, and that these two specifications present a better forecasting performance than the benchmark model.

Estimates of education-specific weights

Data sources and selection of the sample.

In order to derive generalizable weights linked to educational levels, we compiled all available censuses from the IPUMS-International database that included both total personal income as well as education variables. We opted to utilize total income rather than wage income alone due to the lack of wage data across many of the surveys. Given that for the majority of individuals, wages typically constitute the primary component of overall income, and the two measures are therefore highly correlated, we make the assumption that total income can serve as a reasonable proxy for wages in our analysis.

Since Mincerian wage regression models assume a log-linear relationship between wages and years of schooling, those persons not active in the formal labor force as well as those with reported incomes at or below zero were assigned an income value equal to one for modeling purposes. Employed individuals with missing income data (4.3%) were omitted from the sample altogether. The IPUMS-International census data leveraged offers the benefit of standardized definitions and categorical binning of key variables. However, the income figures are expressed in national currency units corresponding to the specific period of each survey. As such, we additionally normalized respondents’ incomes by dividing through by the national average income level in order to render the values more readily comparable across countries and time.

The education variable is provided in two formats - number of years of education or highest educational attainment level, with varying category breadth. We opted to use years of education in our models since broad attainment categories can obscure substantial within-group heterogeneity. For example, in countries with mandatory education, the lowest group comprises those lacking a high school diploma, while in developing countries surveys more typically differentiate individuals with no schooling from those with some primary or lower secondary schooling.

For surveys only reporting educational attainment, levels were converted to estimated years of schooling as follows:

Less than primary completed → 1 year;

Primary completed → 6 years;

Lower secondary complete → 9 years;

Secondary completed → 12 years;

University completed → 16 years.

Surveys were excluded if attainment categories were insufficiently detailed for comparison to other data sources, such as a single category encompassing both high school and university completion.

We excluded individuals aged under 20 and over 64 from the sample. With the pooled censuses still comprising several million cases even after applying age criteria, we randomly selected a large enough sample from each to generate stable and robust estimates while enabling feasible computational runtimes for the regression models. The included surveys and their corresponding sample sizes are listed in Table 1 .

We estimated the education-specific weights from Mincerian earnings function 22 , which is widely used in the literature to measure the return on investment in education 23 . We start by building a simple log-linear model with gamma distribution, predicting the natural log of normalized income (NOR_INC) from years of education (NBEDU), controlling for experience and sex, but ignoring sample design,

\({\beta }_{1}\) thus provides the semi-elasticity of income to years of education. The variable EXPERIENCE is derived by subtracting from the age the number of years of education and the age of entry at school (set by default to 6 for everyone). Since we aim at estimating generalizable weights, a sample of pooled censuses from different years and different countries is used. Therefore, to account for this sample design, we built a multilevel random-effect model (model 2) which allows the intercept \({\beta }_{0}\) to vary across censuses (j).

Finally, we build a final third model to account for the possible variation in the impact of years of education across countries based on the average level of education of their population 23 . This model adds parameters β 5 and \({\beta }_{6}\) for the interaction between the number of years of education at the individual level and a country-level variable that refers to the average years of schooling for the population aged 25 to 54 (NBEDU_MEAN) in each census year.

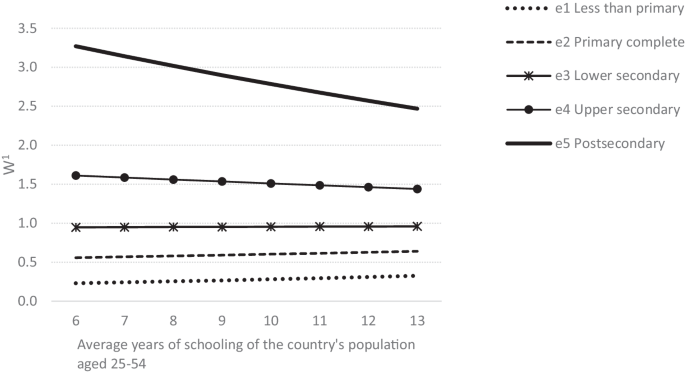

Table 2 shows the parameter estimates for the three models employed. Despite income normalization, the covariance estimates in the model given by Eq. ( 2 ) indicate statistically significant intercept variability across censuses, evidence supporting the mixed model. The introduction of an interaction term between an individual’s years of schooling and the country’s average years of schooling in the model given by Eq. ( 3 ) reveals that the positive relationship between education and wages diminishes in size as a population’s overall education level rises. Specifically, the negative parameter predicts smaller wage gains for marginal increases in an individual’s schooling within societies where higher education is more widespread. This is in line with economic principles, as the marginal value of educational attainment decreases when advanced skills become common, and thus the advantages conferred by an extra year of schooling are attenuated when competing against a highly educated population. Thus, the model given by Eq. ( 3 ) provides evidence that the labor market return of education depends on both relative and absolute skills and declines in contexts where human capital is abundant. Across all model specifications, the estimated parameters for NBEDU (years of schooling) remain remarkably consistent and comparable, underscoring the reliability of these coefficients.

Using parameters from the model in Eq. ( 3 ), we calculate relative weights (W) for each educational level (e), which vary depending on the population’s average years of schooling (NBEDU_MEAN) of the country (c) in a given year (t). We postulate that having less than primary completed (e1) corresponds to 1 year of schooling (NBEDU = 1), primary completed (e2) to 6 years, lower secondary (e3) to 9 years, upper secondary (e4) to 12 years and postsecondary (e5) to 16 years. We normalize the weights making use of the value for the world average number of years of schooling in 2015 (9.3). The calculation of W is thus given by

Figure 1 below presents weights by educational attainment and average years of schooling. In a country such as the US in 2020, where the average number of years of education for the population aged 25–54 was 13.2 years, a person with postsecondary education would thus be weighted 2.45 times more than a worker with the world average number of years of education and, assuming that income is a good proxy for productivity 24 , would thus be 2.45 times more productive.

Weights (W) by educational levels and average years of schooling of the 25–54. 1 = world average level of education = 9.3 .

Factorizing for the quality of education

Lutz et al . 18 introduced the Skills in Literacy Adjusted Mean Years of Schooling (SLAMYS) to assess the quality of education and human capital. This indicator multiplies the mean years of schooling (MYS) by a factor that takes into account the quality of education (skill adjusted factor or SAF). SAFs are empirically derived from the scores of adult literacy assessments (for individuals aged 20–64) from surveys such as the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), the Skills toward Employment and Productivity Survey (STEP), and the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). They are calculated cross-sectionally for 185 countries for the period 1970–2015 and normalised to the score for the population-weighted average of OECD countries in 2015 (taken as unity).

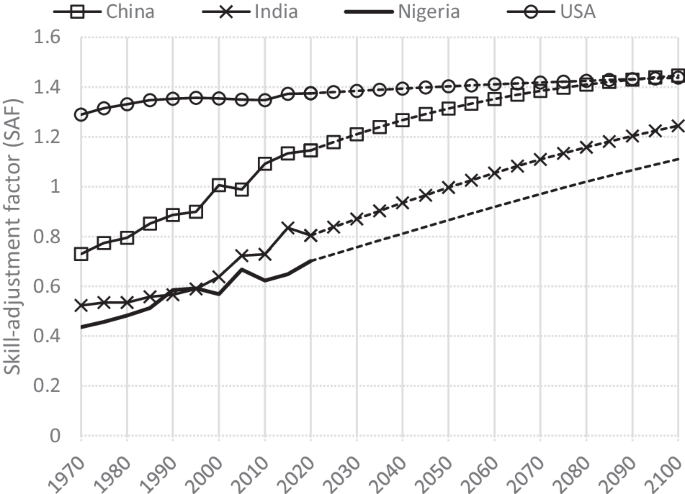

To adjust our education-weights for the quality of the education, we use these country- and period-specific SAF from 1970 to 2015 and perform a logit extrapolation for 2015–2100, with the maximum value being the world’s highest estimate in 2015 (which is 1.13 for Japan), thus leading to a gradual convergence towards the leading country. We then normalize the score to the world average of 2015. Figure 2 shows the estimated SAF for China, India, Nigeria and the US and the projections from 2020 to 2100.

Skill-adjustment factor (1 = world average in 2015) for China, India, Nigeria and the US, estimated (1970–2015) and projected (2020–2100).

SAF estimates are cross-sectional, without disaggregation by age, cohort, or specific level of education. In other words, using these values implies to assume no difference in the quality of education across the different degrees within a country. It is also assumed that the change in the cohort size of the population aged 20–64 has only a marginal effect on the trends. Finally, we use the simplifying assumption that the quality of education does not differ between those in the labor force and those out of the labor force.

Population estimated and projected by age, sex, and education

The calculation of projected HCWP requires inputs from population projections by age, sex, and education. We used the most recent update of the population estimates (middle-of-the-road) for the period 1970–2015 and their population projection under five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways scenarios 25 . The last update of the projections and estimates take into account the impact of COVID-19 on the population structure as well as the latest estimates of demographic components as starting point. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways scenarios for 2020–2100 are built around narratives and storyline describing alternative socio-economic developments. They were developed by climate scientists and economists to be used as a basis for integrated assessments and future climate modeling. The five scenarios are:

SSP-1: Sustainability;

SSP-2: Middle-of-the-road;

SSP-3: Regional rivalry;

SSP-4: Inequality;

SSP-5: Fossil-Fueled Development.

The SSP-2 (Middle-of-the road) scenario can be considered as the reference scenario, as its assumptions are built based on historical patterns. For the mortality assumptions, 75 experts from 30 countries were asked for their opinion on a series of statements on past and future determinants of health and mortality. They concluded that there is room for improvement and that upward trends will continue, with convergence between countries. Country-specific trends are therefore extrapolated with a regional convergence process. Differentials by educational attainment are based on a generalization of estimates where such data are available. For the assumption on international migration, the scenario assumes a continuation of the in and out- migration rates of 1950–2010.

For education, final educational attainment (attained at age 30–34) is extrapolated by gender from country-specific estimates for 1970–2010 with a long-term world convergence. For those with a high level of education, lower levels are imputed at younger ages based on the country’s high school graduation age. In this projection, the educational attainment variable is categorical rather than in years of schooling. Therefore, education-weights are calculated based on the normal number of years of education for each level (see data source and sample selection). The future age- and education- specific fertility rates are determined on the basis of a large expert survey in the field of fertility studies 26 , 27 . The experts assumed a trend towards global convergence in the very long term. More details on the long-term assumptions and in the scenario definition can be found in in Lutz et al . 17 , 28 .

Calculation of the human capital-weighted population

For a country c at time t , the human capital-weighted population (HCWP) is calculated as:

W e,c,t corresponds to the education (e) weights specific to the average educational group of the country c at time t as calculated in the previous section. POP2064 e,c,t is the population aged 20–64 from country c at time t with an educational attainment e . SAF c,t is the Skill-adjustment factor specific to country c at time t .

The population projection outcomes by education are sourced from the WIC (see previous section), in which the educational attainment variable is categorical rather than in number of years of schooling. Therefore, education-weights are calculated based on the assumed number of years of education for each level (see data source and selection of the sample). For instance, there were 76.4 M persons aged 20–64 with a postsecondary education (16 years of schooling) in USA in 2020 (POP2064 e6,USA,2020 ). Since the average number of years of schooling in 2020 was 13.2, the value of W e6,USA,2020 is 2.45. Multiplying W e6,USA,2020 by POP2064 e6,USA,2020 , gives 187 M, which means, in other words, that these 76.4 M persons with upper secondary would have a human capital equivalent 187 M Americans who would have 9.3 years of schooling. The SAF value for USA in 2020 is 1.33. Adjusted for this factor, the human capital figure is 249 M. Assuming that within a country, the income is a good proxy for productivity, and that across countries, there is a linear relationship between the quality of education and productivity, these 76.4 M Americans with postsecondary education would have the productive capacity of 249 M persons with the 2015 world average’s human capital. The HCWP for USA in 2020 is given by the sum of this calculation for each educational group.

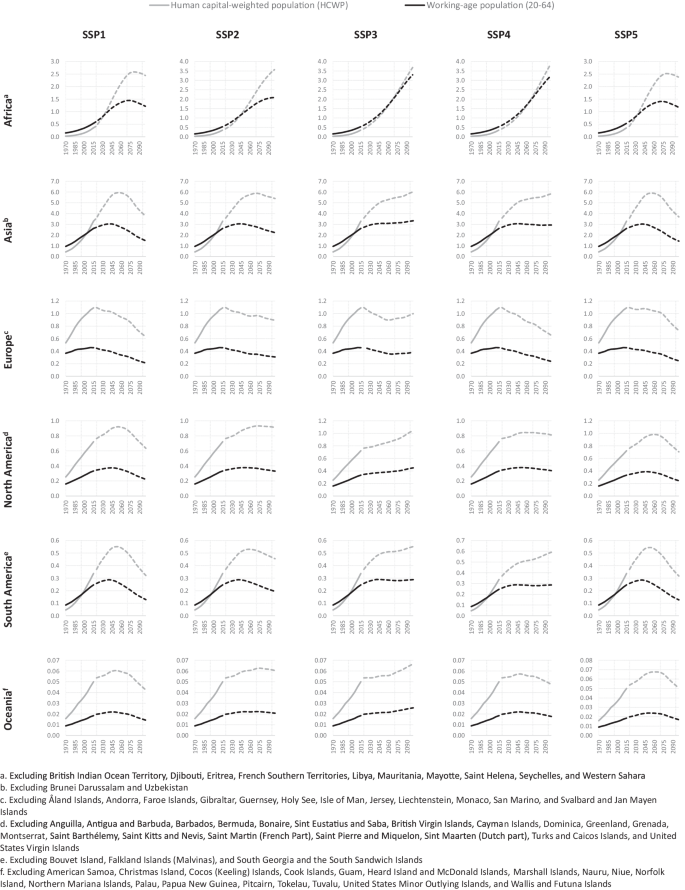

Figure 3 shows the estimated human capital-weighted population together with the working-age (20–64) population size from 1970–2020 by continent and their projection up to 2100 according to the five SSP scenarios.

Working age population (WAP) and human capital-weighted population (HCWP), estimated (1970–2020) and projected (2020–2100) according to five SSP scenarios (in billions).

Data Records

The dataset OUTPUT_HCWP.csv available on Zenodo 1 contains three columns for analytical indicators: human capital-weighted population (HCWP), total working-age population aged 20–64 (WAP) and the total population (POP) for 185 countries (identified in “CountryName” and “CountryCode” columns). The “CountryCode” column corresponds to country codes from the Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (M49) provided by the Statistics Division of the United Nations Secretariat. “Region” and “Continent” correspond to the geographical classification of countries by the United Nations Statistics Division.

The total working-age population and the total population are taken directly from the Wittgenstein Centre’s Data Explorer and are included in the dataset for information purposes, to give a better idea of the contribution of HCWP compared with this conventional indicator. Each variable contains 17,575 values, 185 countries X (10 periods from 1970–2015 + 5 scenarios X 17 periods from 2020 to 2100).

Technical Validation

We validate the HCWP data in the context of out-of-sample economic growth forecasts, by comparing the predictive content of the information of HCWP with that of human capital variables based exclusively on educational attainment. We estimate the econometric model proposed by Crespo Cuaresma 5 using data for GDP per capita and capital stocks from the Penn World Table 10.1 29 , population and educational attainment data from the WIC. The estimated models are based on an aggregate production function where technological progress is assumed to depend on innovation mechanisms (proxied alternatively using educational attainment and HCWP as the human capital stock variable) and technology adoption effects (included in the model as the interaction of the human capital variable and the level of income per capita). Using the estimated panel data models based on the global sample of countries and the period 1970–1995 in 5-year periods, out-of-sample predictions for all countries in 1995–2000 are obtained, and prediction error measures (root mean square error, mean absolute deviation and directional accuracy rate, that is, the share of correctly predicted directions of change) are computed. The exercise is repeated expanding the in-sample period to 1970–2000 and using the out-of-sample period 2000–2005, then for the in-sample period 1970–2005 and predictions for 2005–2010, and finally for models estimated using data for 1970–2010 and forecasts for 2010–2015. We compare the average prediction errors for the different models over all of the out-of-sample observations in this design.

The results of the validation exercise for the models including HCWP as a predictor, the specifications with educational attainment and a benchmark model where total population is used as a human capital variable (without heterogeneity based on education or productivity) are presented in Table 3 . In the global sample, the results for the models based on HCWP are relatively similar to those based on educational attainment, but the specifications that use HCWP as an explanatory variable excel in prediction for the subsample of low and high-income economies. Models based on educational attainment, on the other hand, dominate in terms of forecasting ability for middle-income economies.

While the HCWP model offers a more comprehensive approach by additionally considering educational quality, the complex interplay between human capital accumulation and economic growth at the global level may limit the predictive ability of econometric models built upon the new data. In particular, the assumption of parameter homogeneity which underlies our econometric specification may be restrictive for our global sample of countries, that contains economies with very different institutional, political, and cultural characteristics. Furthermore, synergies between quantity and quality of education are not necessarily linear or additive, and exploring such interactions could be a promising path of future research. Finally, the data used to construct the HCWP model may contain inherent variability and measurement issues, particularly when assessing educational quality across different global contexts. Future research could delve deeper into context-specific analyses to further explore these dynamics.

Usage Notes

The methodology used to produce the human capital-weighted population (HCWP) estimates has some limitations. First, human capital is assessed only in terms of the quality and quantity of education. This approach may oversimplify the multidimensional nature of human capital, as it fails to consider other critical dimensions such as health, which influences educational opportunities, labor force participation, and productivity 30 . By excluding health, our analysis could potentially overestimate the HCWP and underestimate cross-country variations. Indeed, the HCWP takes into account only the gains in human capital resulting from changes in education, neglecting the potential impact of health variables among others. Future research iterations should explore the inclusion of health-related factors to capture a more comprehensive understanding of human capital.

Moreover, the education variable itself may oversimplify the diversity in educational attainment, potentially masking important nuances in educational backgrounds. This approach may not fully capture the varying impacts of different types of education on human capital accumulation. This is particularly true in countries where a large share of the population has post-secondary education, which includes very different specializations and skills.

Furthermore, the use of pooled censuses from different countries and years to estimate human capital weights may overlook country-specific nuances and variations in educational systems, labor markets, and economic conditions, which could significantly influence the relationship between education and human capital. It is also worth noting that although the countries included in our sample cover many degrees of development, many countries are missing from the analysis. Most censuses were from countries in the Americas, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings to other regions with distinct socioeconomic and cultural contexts.

Additionally, our approach of adjusting education weights for quality using cross-sectional data from adult literacy assessments assumes uniform quality across different levels of education within a country. This assumption may overlook potential variations in educational quality that could impact human capital differently across various educational levels.

Finally, projecting future human capital-weights based on assumptions about educational trends and fertility rates introduces uncertainties related to demographic changes, economic developments, and policy interventions that may not materialize as projected. These uncertainties could potentially affect the accuracy of our long-term projections.

Code availability

Regression models to estimate of human capital-weights (Eqs. 1 , 2 and 3 ) were run using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS 9.4.

/* Model 1 */

proc glimmix data = data INITGLM ;

title " Fixed all ";

class sample SEXR ;

model norm_sal = nbedu experience|experience SEXR / solution dist = gamma link = log ;

weight perwt ;

where 0 < norm_sal < 15 and 20 < = agegr < = 64 ;

NLOPTIONS TECH = NRRIDG MAXITER = 100 ;

/* Model 2 */

title " Random intercept ";

random intercept / subject = sample ;

where 0 < norm_sal < 15 and 20 < = agegr < = 64 ;

/* Model 3 */

title " Random intercept with interaction ";

model norm_sal = nbedu|nbedu_mean experience|experience SEXR / solution dist = gamma link = log ;

The code for the calculation of the Human capital weighted population estimates is available on Github ( https://github.com/gmarois/HCWP/blob/main/Code%20for%20HCWP.sas ).

Marois, G., Crespo Cuaresma, J., Zellmann, J. G. & Reiter, C. Human Capital-weighted population estimates for 185 countries from 1970 to 2100 (2.0) Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11484066 (2024).

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D. & Sevilla, J. The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change . (2003).

Golley, J. & Tyers, R. Demographic dividends, dependencies, and economic growth in China and India. Asian Econ. Pap. 11 , 1–26 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Mason, A., Lee, R. & Jiang, J. X. Demographic Dividends, Human Capital, and Saving. J. Econ. Ageing 7 , 106–122 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Crespo Cuaresma, J. Income projections for climate change research: A framework based on human capital dynamics. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 226–236 (2017).

Crespo Cuaresma, J., Lutz, W. & Sanderson, W. C. Is the demographic dividend an education dividend? Demography 51 , 299–315 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lutz, W., Crespo Cuaresma, J. & Sanderson, W. C. The demography of educational attainment and economic growth. Science 319 , 1047–1048 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lutz, W. et al . Education rather than age structure brings demographic dividend. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci . 201820362, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820362116 (2019).

KC, S., Wurzer, M., Speringer, M. & Lutz, W. Future population and human capital in heterogeneous India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115 , 8328 (2018).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lutz, W. & KC, S. Global human capital: Integrating education and population. Science 333 , 587–592 (2011).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Martin, T. C. & Juarez, F. The impact of women’s education on fertility in Latin America: Searching for explanations. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 21 , 52–80 (1995).

Valkonen, T. Social inequalities in mortality. in Demography: Analysis and Synthesis Volume 2: A Treatise in Population Studies (eds. Caselli, G., Vallin, J. & Wunsch, G.) vol. 2 195–206 (Academic Press, London, UK, 2006).

Docquier, F. & Marfouk, A. International migration by education attainment, 1990-2000. in International Migration, Remittances and the Brain Drain (eds. Özden, C. & Schiff, M.) 38 (The World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2004).

Skirbekk, V. Fertility trends by social status. Demogr. Res. 18 , 145–180 (2008).

Kravdal, Ø. & Rindfuss, R. R. Changing Relationships between Education and Fertility: A Study of Women and Men Born 1940 to 1964. Am. Sociol. Rev. 73 , 854–873 (2008).

Marois, G., Sabourin, P. & Bélanger, A. How reducing differentials in education and labor force participation could lessen workforce decline in the EU-28. Demogr. Res. 41 , 125–160 (2019).

Demographic and Human Capital Scenarios for the 21st Century . (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018).

Lutz, W. et al . Skills-adjusted human capital shows rising global gap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 , e2015826118 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Heyneman, S. P. International education quality. Spec. Issue Honor Lewis C Solman 23 , 441–452 (2004).

Google Scholar

Marois, G., Bélanger, A. & Lutz, W. Population aging, migration, and productivity in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117 , 7690 (2020).

Marois, G., Gietel-Basten, S. & Lutz, W. China’s low fertility may not hinder future prosperity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 , e2108900118 (2021).

Mincer, J. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings . (Columbia University Press, New York, 1974).

Psacharopoulos, G. & Patrinos, H. A. Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. Educ. Econ. 26 , 445–458 (2018).

Van Biesebroeck, J. How Tight Is the Link between Wages and Productivity? A Survey of the Literature . 47 (2015).

KC, S. et al . Wittgenstein Center (WIC) Population and Human Capital Projections - 2023. Zenodo , https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7921989 (2023).

Basten, S., Sobotka, T. & Zeman, K. Future fertility in low fertility countries. in World Population and Human Capital in the 21st Century (eds. Lutz, W., Butz, W. P. & KC, S.) 39–146 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014).

Fuchs, R. & Goujon, A. Future fertility in high fertility countries. in World Population and Human Capital in the 21st Century (eds. Lutz, W., Butz, W. P. & KC, S.) 147–225 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014).

Lutz, W., Butz, W. P. & KC, S. World Population & Human Capital in the Twenty-first Century: Executive Summary. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/11189/ (2014).

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R. & Timmer, M. P. The Next Generation of the Penn World Table. Am. Econ. Rev. 105 , 3150–3182 (2015).

Gyimah-Brempong, K. & Wilson, M. Health human capital and economic growth in Sub-Saharan African and OECD countries. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance 44 , 296–320 (2004).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Research Fund for International Scientists of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 72250610226].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Asian Demographic Research Institute, School of Sociology and Political Sciences, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

Guillaume Marois

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, OeAW, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, OeAW, University of Vienna), Laxenburg, Austria

Guillaume Marois, Jesus Crespo Cuaresma & Claudia Reiter

Department of Economics, Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU), Vienna, Austria

Jesus Crespo Cuaresma & Jakob Zellmann

Education and Employment research group, Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS), Vienna, Austria

Claudia Reiter

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: G.M. Methodology: G.M., J.C.C. Investigation: G.M., J.C.C. Visualization: G.M. Data Collection: G.M., C.R. Validation: J.Z., J.C.C. Writing – original draft: G.M., J.C.C. Writing – review & editing: J.C.C., C.R.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Guillaume Marois .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Marois, G., Cuaresma, J.C., Zellmann, J. et al. A dataset of human capital-weighted population estimates for 185 countries from 1970 to 2100. Sci Data 11 , 612 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03466-y

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2024

Accepted : 03 June 2024

Published : 12 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03466-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Performance through people: Transforming human capital into competitive advantage

At a glance.

- When companies emphasize skill development, it pays off for workers. Skills learned on the job contribute 46 percent of the average person’s lifetime earnings, and companies that build human capital are more likely to propel their employees into higher earnings brackets over the course of a career.

- Building human capital also pays off for firms in the form of more consistent earnings and greater resilience during crisis. In addition to being more consistent than their sector peers, human capital builders are better at retaining talent, with attrition rates that are about 5 percentage points lower.

- Some firms (“People + Performance Winners”) prioritize developing their employees and manage to deliver top-tier profitability at the same time. These companies are more likely to become large-scale “superstars.” They exist in all sectors and average more than $1 billion in economic profit.

- People + Performance Winners have a distinctive organizational signature that challenges and empowers employees while fostering bottom-up innovation. This form of organizational capital contrasts with that of other top-performing firms, which tend to be more top-down and transactional. This management style seems to activate human capital and create a tangible competitive advantage.

MGI’s previous research has shown that human capital development pays off for workers , with skills learned on the job accounting for almost half of the average person’s lifetime earnings. But does investing in people actually benefit companies? Most business leaders agree that it’s the right thing to do. But they are less clear on how those efforts relate to the bottom line—and why some organizations are so much more effective than others at turning human capital into a real competitive advantage.

To explore these questions, we analyze 1,800 large companies across sectors in 15 countries, sorting them based on two factors: how much they focus on developing human capital and whether they financially outperform their sector peers.

One subset in particular stands out: People + Performance Winners (P+P Winners) excel at creating opportunities for their employees to build skills (which we measure by looking at internal mobility, training hours, and organizational health scores) while consistently clearing the highest bar for financial performance. Another group, Performance-Driven Companies, similarly achieve top-tier financial results but do not put the same kind of emphasis on skills development and the work environment. A third group, People-Focused Companies, put resources into developing employees but are unable to translate that into strong financials. Finally, the majority of firms are Typical Performers that stand out on neither dimension.

P+P Winners distinguish themselves from Performance-Driven Companies in two important ways. They achieve more consistent results and have greater earnings resilience, and they also have a superior ability to attract and retain talent (Exhibit 1). These are important advantages at a time when companies are facing economic headwinds and labor shortages.

While they closely tracked Performance-Driven Companies on profitability and shareholder returns over the prepandemic decade, P+P Winners were roughly 1.5 times more likely to remain in the top tier year after year, and they had about half the earnings volatility.

P+P Winners are not only consistent through the normal ups and downs of business cycles; they are also more resilient in times of crisis. When the pandemic struck, they were more likely to weather the crisis and avoid taking major hits. Only 54 percent of P+P Winners saw a reduction of more than 0.5 percentage point in return on invested capital from 2019 to 2020, compared to 65 percent of Performance-Driven Companies. In fact, 36 percent of P+P Winners saw an increase of more than 0.5 percentage point (versus 29 percent of Performance-Driven Companies). More P+P Winners found growth opportunities in the crisis years as well. From 2019 to 2021, they grew revenue twice as fast as Performance-Driven Companies (8 percent versus 4 percent). Organizations that had spent years building reserves of loyalty, goodwill, and innovative capacity by investing in people may have had more internal resources to draw on when the chips were down.

Investing in human capital is associated with consistency and resilience for other companies, too. In the two segments that are not top performers financially, People-Focused Companies demonstrated greater stability than Typical Performers. Typical Performers were 1.5 times more likely than an average firm in our sample to remain in the bottom quintile of profitability in nine out of ten years, while People-Focused Companies were only 1.1 to 1.3 times as likely. The latter also demonstrated greater resilience during the pandemic, growing their revenue twice as fast as Typical Performers (6 percent versus 3 percent) from 2019 to 2021.

A McKinsey event on "Performance through people: Transforming human capital into competitive advantage"

P+P Winners are also talent magnets, with attrition rates almost five percentage points lower than those of Performance-Driven Companies. Their employees report higher job satisfaction and are 1.3 times more likely to move into higher lifetime earnings brackets than employees of Performance-Driven Companies. People-Focused Companies have similarly high levels of employee satisfaction and even lower attrition than P+P Winners, although not with the same stellar financial performance.

How do P+P Winners manage to succeed on both fronts? While investing in people is important, our research shows that another ingredient is needed to bring out their best and channel their efforts into results: organizational capital—that is, the management practices, systems, and culture within each company. This concept encompasses everything from training programs to workflows, department and team structures, employee communications, norms, culture, and leadership. When these elements are effective, they can turn a collection of talented individuals into a cohesive team.

Organizational capital is the fabric that surrounds employees, and its pattern matters. We compare the practices of each group of companies using McKinsey’s Organizational Health Index diagnostic and other firm-level metrics. P+P Winners have a distinctive signature characterized by consultative and challenging leadership styles; bottom-up innovation and collaboration; positive and inclusive work environments; and rewards and advancement opportunities for employees (Exhibit 2). Performance-Driven Companies have similar leadership styles but are more externally oriented to customers and competitors, with less emphasis on engaging their people through company-wide innovation, motivation, work environment, and on-the-job coaching. People-Focused Companies have many practices in common with P+P Winners (such as motivating employees and creating positive work environments), but they are less results-oriented, and they do not emphasize bottom-up innovation.

On average, companies spend about one-third of their revenue on human and organizational capital (which we measure by using the proxy of compensation for the former and adjusted selling, general, and administrative spending for the latter). This is a significant investment, and companies need to make it as productive as possible. P+P Winners achieve roughly 30 percent higher revenue growth than both Performance-Driven and People-Focused Companies for every dollar they invest in human and organizational capital. By contrast, Performance-Driven Companies generate higher return on R&D and sales and marketing investment—but they have the potential to boost their overall results even further by making their investments in people and workplace systems more effective.

Corporate leaders need a deeper focus on the nuances of organizational capital. Human capital is not merely a labor input; people are any company’s core asset. The workplace should work for employees, with coaching to help them develop, structures for support, and workflows that remove frustrations. Employees know what works on the front lines, and their voices and viewpoints should inform any redesign. Beyond improving the day-to-day experience for workers at every level, these principles can enhance competitiveness and adaptability in a fast-moving world.

In some cases, altering company-wide policies and systems could spur positive change. In others, it will take behavior change from leaders. While C-suite executives can articulate the vision and set the example, frontline and middle managers are key actors since they set the tone for individual teams, have greater visibility into what’s working, and can be the biggest influence on the employee experience.

Not every company will choose to follow the P+P Winner template. Some are singularly driven by financial results; focusing on people may not be in their DNA. Remaking organizational culture is a difficult, ongoing commitment that requires energy, self-reflection, and a willingness to change familiar patterns.

But companies that adopt a more people-oriented focus along with a more challenging and empowering organizational culture have a lot to gain. In addition to boosting financial returns, they can improve their consistency, resilience, talent retention, employee loyalty, and reputation—and these are the hallmarks of companies that thrive over the long term.

Want to know more about Performance through People?

Download the full report

Anu Madgavkar is a McKinsey Global Institute partner in New Jersey; Bill Schaninger is a McKinsey senior partner in the Philadelphia office; Dana Maor is a senior partner in the Tel Aviv office; Olivia White is an MGI director in San Francisco; Sven Smit , MGI’s chair, is based in Amsterdam; Hamid Samandari is a McKinsey senior partner in the New York office; Lola Woetzel is an MGI director in Shanghai; Davis Carlin is a McKinsey partner in New York; and Kanmani Chockalingam is an MGI fellow in Bengaluru.

This article was edited by Lisa Renaud, an MGI executive editor in Los Angeles.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Human capital at work: The value of experience

‘Great Attrition’ or ‘Great Attraction’? The choice is yours

- My Favorites

You have successfully logged in but...

... your login credentials do not authorize you to access this content in the selected format. Access to this content in this format requires a current subscription or a prior purchase. Please select the WEB or READ option instead (if available). Or consider purchasing the publication.

- Disclaimers

Introduction

Human capital is among the main oecd structural policy priorities, human capital as a driver of economic outcomes: definition and conceptual framework, empirical microeconomic evidence of the outcomes of education for individuals, empirical macroeconomic evidence of the aggregate impact of education, a new measure of human capital to improve estimates of the macroeconomic outcomes of education, 1. the importance of human capital for economic outcomes.

Human capital is widely regarded as a fundamental input in growth theory. Furthermore, recommendations to boost human capital feature prominently among structural policy priorities identified by the OECD for a number of countries. However, the empirical evidence linking human capital with macroeconomic outcomes has been problematic. This chapter first provides an overview of the role of human capital in determining economic outcomes and reviews existing evidence on this topic. It then presents a new measure of human capital based on OECD education data surveys, which better incorporates both quality and quantity dimensions. Drawing on the proposed measure of human capital, this chapter suggests a substantial scope for long-run productivity gains from human capital, with a larger effect from quality as compared to quantity improvements, although the lags are typically much longer than for other policies that boost productivity.

The fiscal response of OECD governments to the COVID-19 crisis has been swift. Across the OECD, governments have committed billions of dollars to support public health systems, prevent massive business failures and protect households from the impact of the crisis. The additional spending (or forgone revenue) amounts to around 10% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on average in OECD countries over 2020-2021, with wide disparities across countries (IMF, 2022[1]) . The aid to the health sector represents on average 1.5% of GDP. Public debt ratios in 2023 are projected to exceed 2019 levels considerably (by 15 percentage points in the median OECD economy) (OECD, 2022[2]) . They will need to be adjusted over the medium term given future demands on public finances from long-term trends such as ageing populations (Guillemette and Turner, 2021[3]) and climate change. Boosting growth will help reduce the debt-to-GDP ratios. However, more recent developments related to the consequences of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine are likely to further strain public finances. While stagnating economic growth will lower fiscal revenues, increased expenditures are expected in many OECD countries: rocketing energy costs call for efforts to support households and small businesses, rising interest rates put pressure on public debt, and spending on defence gains new priority in the new geopolitical context (OECD, 2022[4] ; NATO, 2022[5]) .

Substantial public resources will continue to be needed to support the health sector further, to address the economic consequences of the new geopolitical situation and to accelerate the green and energy transitions in an effort to limit climate change and enhance energy sovereignty. Finance ministries will therefore be faced with complex choices and competing budgetary priorities in seeking to balance short-term and long-term economic, geopolitical, environmental and social goals. In this context, it is useful to undertake a critical assessment of the importance of various pillars of economic growth, and more specifically the importance of education, for economic outcomes.

From an economic perspective, sustained high-quality education constitutes a long-term investment in the knowledge, skills and competencies of people, leading to higher productivity, earnings and quality of life for individuals. At the macro level, a well-educated workforce is a key factor in achieving greater aggregate productivity, innovation and long-term economic growth. Yet, these economic benefits are not always straightforward to measure, in part due to data constraints.

Human capital is widely regarded as a fundamental input in the theoretical growth literature. 1 Furthermore, recommendations to boost human capital feature prominently among structural policy priorities identified by the OECD for a number of countries (OECD, 2021[6]) . However, despite this emphasis in both economic theory and policy practice, the empirical evidence linking human capital with economic outcomes has been problematic, especially at the macroeconomic level.

This chapter provides a short overview of the role of human capital in determining economic outcomes, including both microeconomic and macroeconomic evidence, and concludes by summarising a proposal for a new measure of human capital, which better incorporates both quality and quantity dimensions by using OECD data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC). Incorporating this new measure of human capital within the OECD’s standard framework for assessing structural reforms suggests substantial scope for long-run productivity gains from human capital, with greater potential from improvements in the quality than the quantity component of human capital, although the lags are typically much longer compared to other policies that boost productivity.

This chapter is organised around five sections:

First, the chapter provides a brief account of the literature on the role of human capital for economic outcomes, and its importance as a key structural policy priority in OECD countries.

Second, the chapter elaborates on the definition of human capital and the conceptual framework underpinning the concept.

Third, the chapter reviews the empirical microeconomic evidence on rates of return to education for individuals, in terms of employability premia and equilibrium effects.

Fourth, the chapter outlines the empirical macroeconomic evidence deriving from growth accounting and cross-country regression analyses.

Finally, the chapter offers a proposal for a new measure of human capital based on OECD PISA and PIAAC and mean years of schooling data and examines the effects of this new measure of human capital on multi-factor productivity.

The OECD has consistently singled out education and skills development as a key structural policy priority in its economic reviews of OECD and non-OECD countries…

Boosting human capital is one of the main structural policy priorities recommended by the OECD for a large number of OECD and non-OECD countries (OECD (2021[6]) and Figure 1.1. ). In both cases, recommendations related to education and skills development account for the second largest share of total policy priorities behind product market reform. Further, the recommendations concern all levels of formal education and training in the workplace ( Figure 1.2. ):

Expanding the quality of pre-school childcare. Evidence shows that early childhood education and care provide the basis for a child’s future skills development and learning. This is particularly true for disadvantaged children (OECD, 2018[7]) . Expansion of pre-primary education improves educational attainment, labour market attachment and welfare dependency (Braga et al., 2013[8] ; Havnes and Mogstad, 2011[9]) .

Improving teacher quality . Within schools, teaching quality is the single most important factor that affects students learning (OECD, 2005[10]) . The quality of teachers is an elusive concept that cannot be directly measured reliably, but it has been proxied, for instance, by the share of certified teachers, the PIAAC score of teachers, or teachers’ wages, which have all been found to show a positive association with student test scores (Hanushek, Piopiunik and Wiederhold, 2019[11] ; Dolton and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, 2011[12]) . These findings suggest that teacher quality does indeed matter, although the exact mechanisms at play remain to be investigated.

Improving tertiary education . Tertiary education has an impact on wage earnings of its graduates. Higher education institutions that have the autonomy to manage their financial resources, staff policies and the selection of students have been often shown to achieve better education outcomes (Oliveira Martins et al., 2007[13]) .

Developing lifelong learning . While technology is evolving rapidly, workers need to adapt quickly to the new requirements of the labour market. Skills acquired in formal education or in previous jobs become obsolete more quickly. Lifelong learning is key to help workers upgrade and expand their skills and adapt to technological change (OECD, 2021[14]) . On average across OECD countries, 57% of medium- and high-income adults participate in adult learning, while only 35% of low-income adults do so (OECD, 2019[15]) . Policies should aim at raising the participation of people with low levels of education in lifelong learning. Denmark, Sweden and Norway managed to attain the same participation of workers regardless of income level (OECD, 2019[16]) .

This emphasis on education and skills development is consistent with the prominence of human capital as a key driver of productivity and growth in economic theory

The prominence of education policy recommendations in structural reform priorities is not surprising considering the strong theoretical underpinnings of the importance in human capital in productivity and income developments. However, efforts at providing empirical evidence have been more mixed, not least because of the difficulty of developing a measure of human capital that can adequately capture intangible characteristics such as knowledge and skills. This is briefly reviewed in the next sections.

Source: Adapted from OECD, (2021[6]) Economic Policy Reforms 2021: Going for Growth: Shaping a Vibrant Recovery, https://doi.org/10.1787/18132723 , Figure 2 .

Source: OECD (2021[6]) , Economic Policy Reforms 2021: Going for Growth: Shaping a Vibrant Recovery, https://doi.org/10.1787/18132723 , Figure 1.A.8 .

Economic theory has long envisaged human capital as a limited stock of knowledge and skills conceived as a production factor with a finite impact on GDP per capita

Human capital can be broadly defined as the stock of knowledge, skills and other personal characteristics embodied in people that help them to be more productive. Investment in human capital includes investment in formal education (early childhood, formal school and higher education system, adult training programmes), but also informal and on-the-job learning and work experience. A wider definition includes health as well.

Understanding the determinants of economic growth has occupied economists for decades. Starting with a standard aggregate production function where the output of the economy is a function of labour, capital and technological change (Solow, 1956[17]) , the augmented neoclassical growth models incorporated human capital as a production factor (Mankiw, Romer and Weil, 1992[18]) . In these models, the change in gross domestic product per worker is linked to the change in human capital, the latter having only a limited impact as the capacity for a country to invest in human capital faces natural constraints (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2021[19]) .

But endogenous growth models have reinforced interest in human capital, arguing that it also contributes to long-term growth indirectly, through innovation diffusion and TFP 2

By contrast, the endogenous growth literature argues that growth is eventually driven by innovation and that human capital is key to raise the innovative capacity of a country (Schumpeter (2006[20]) , Lucas (1988[21]) ; Romer (1990[22]) ; Aghion and Howitt (1997[23]) ). In these models, the changes in GDP per worker are linked to the level of human capital, the latter influencing long-run growth rates. A last strand of literature argues that human capital facilitates the diffusion of technologies (Nelson and Phelps (1966[24]) ; Welch (1970[25]) ; Benhabib and Spiegel (2005[26]) ). In these models, human capital influences growth directly and indirectly through its impact on total factor productivity.

A key question is whether the relationship between human capital and growth is causal i.e. if higher human capital generates more growth or if higher growth leads to higher human capital. This question is essential as policy makers expect the policies directed to improve human capital to have a positive effect on long-term growth. The first studies analysing the link between the years of schooling and growth may have encountered reverse causality issues (Bils and Klenow, 2000[27] ; Hanushek and Woessmann, 2021[19]) . By contrast, using student performance as a measure of human capital should be less prone to misinterpretation, as it is unlikely that higher growth leads to higher student performance. Indeed, academic literature has found little impact of an increase in education spending on student performance, so there is little chance that higher growth-induced expenditure alters student performance (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2011[28]) .

In human capital theory (Becker, 1967[29]) , schooling is seen as an optimising investment decision based on future benefits and the costs of education. While there are costs associated with the pursuit of studies, the individual returns to education can be large (Schultz, 1961[30] ; Mincer, 1974[31]) . More education is supposed to increase the productivity of individuals which will translate into higher salaries and higher employability probability.

Empirical estimates of rates of return to education show positive returns to more time spent in education