- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Here’s What We Do and Don’t Know About the Effects of Remote Work

Three years into a mass workplace experiment, we are beginning to understand more about how work from home is reshaping workers’ lives and the economy.

By Emma Goldberg

When workplaces are remade by a tectonic shift — women flooding into the work force, the rise of computing — it typically takes some time for economists, psychologists, sociologists and other scholars to gather data on its effects.

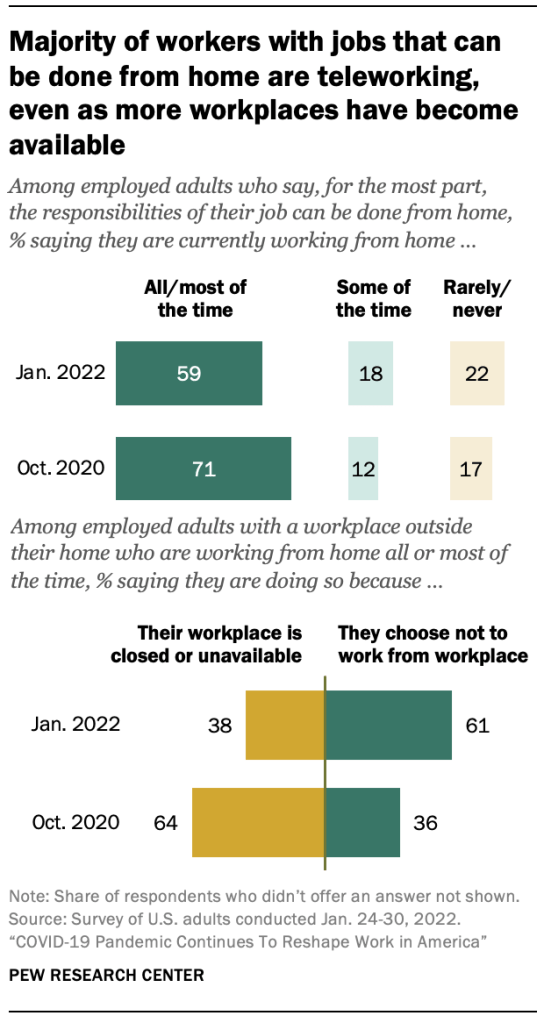

So when employers moved suddenly to adopt remote work during the pandemic, with the share of employed Americans working exclusively from home rising to 54 percent in 2020 from 4 percent in 2019, researchers leaped to examine the effects of remote work on employees and the economy at large. Now the early results are emerging. They reveal a mixed economic picture, in which many workers and businesses have made real gains under remote work arrangements, and many have also had to bear costs.

Broadly, the portrait that emerges is this: Brick-and-mortar businesses suffered in urban downtowns, as many people stopped commuting. Still, some kinds of businesses, like grocery stores, have been able to gain a foothold in the suburbs. At the same time, rents rose in affordable markets as remote and hybrid workers left expensive urban housing.

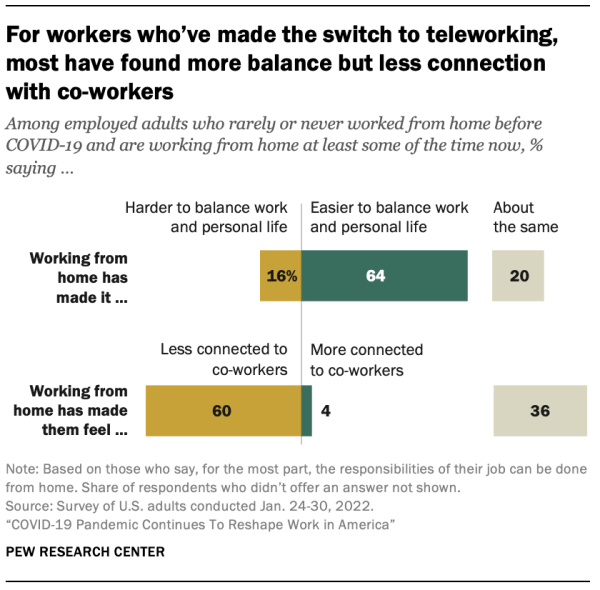

Working mothers have generally benefited from the flexibility of being able to work remotely — more of them were able to stay in the work force. But remote work also seems to bring some steep penalties when it comes to career advancement for women.

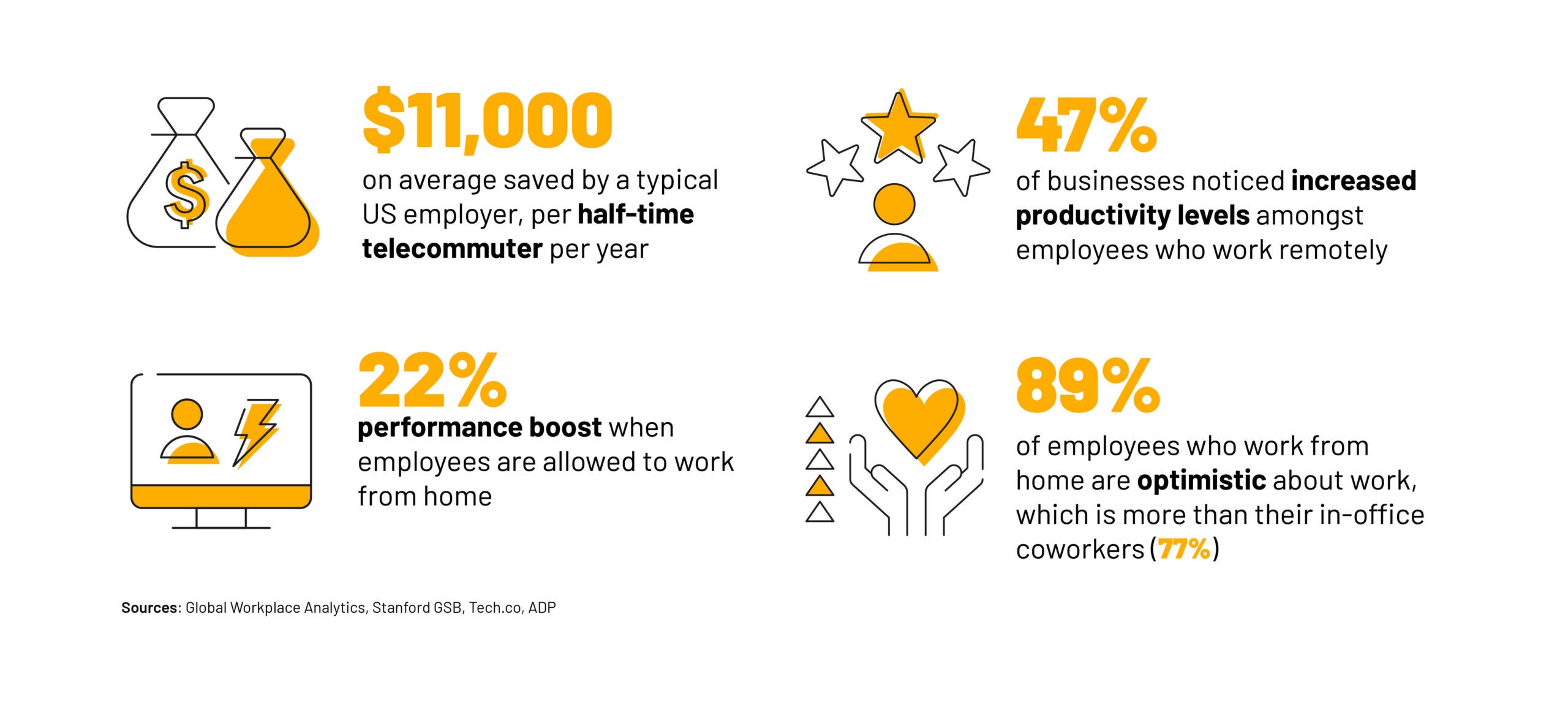

Studies of productivity in work-from-home arrangements are all over the map. Some papers have linked remote work with productivity declines of between 8 and 19 percent , while others find drops of 4 percent for individual workers; still other research has found productivity gains of 13 percent or even 24 percent .

Nick Bloom, an economist at Stanford and a prolific scholar on remote work, said the new set of studies showed that productivity differed among remote workplaces depending on an employer’s approach — how well trained managers are to support remote employees and whether those employees have opportunities for occasional meet-ups.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

The Evolution of Working from Home

Working from home rose five-fold from 2019 to 2023, with 40% of US employees now working remotely at least one day a week. The productivity of remote work depends critically on the mode. Fully remote work is associated with about 10% lower productivity than fully in-person work. Challenges with communicating remotely, barriers to mentoring, building culture and issues with self-motivation appear to be factors. But fully remote work can generate even larger cost reductions from space savings and global hiring, making it a popular option for firms. Hybrid working appears to have no impact on productivity but is also popular with firms because it improves employee recruitment and retention. Looking ahead we predict working from home will continue to grow because of the expansion in research and development into new technologies to improve remote working. Hence, the pandemic generated both a one-off jump and a longer-run growth acceleration in working from home.

Related Topics

- Working Paper

- Innovation and Technology

More Publications

Health insurance: choices, changes, and policy challenges, the funding status of independent public employee pension systems in california, a solution concept for majority rule in dynamic settings.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 15 July 2023

Family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity: do work engagement and self-efficacy mediate?

- Seng-Su Tsang 1 ,

- Zhih-Lin Liu 1 &

- Thi Vinh Tran Nguyen 1 , 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 419 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4666 Accesses

2 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

The shift towards remote work has been expedited by the COVID-19 pandemic, and COVID-19 has increased the need to understand the factors affecting remote work productivity such as family–work conflict, work engagement, and self-efficacy. However, the previous research may not comprehensively capture the intricacies associated with remote work amidst the pandemic. This study proposes a model to explore the relationship between family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity based on role conflict and resource drain theories as well as the family–work-conflict literature. The quantitative approach was used. A questionnaire was distributed using a convenience sampling technique and a response rate of 90.1% (1177 respondents) was achieved. After data cleaning, 785 valid cases were analysed. SPSS 22 and AMOS 20 were used to test the descriptive statistics, reliability, and validity, and the proposed hypotheses were evaluated using Process Macro (Model 5). The findings found that family–work-conflict negatively affected work engagement, self-efficacy, and work-from-home productivity. The negative effect of family–work-conflict on work-from-home productivity was stronger for employees with more work-from-home days than those with fewer. The partial mediation of work engagement and self-efficacy was established. This study contributes to the understanding of remote work productivity during the pandemic, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprise employees. It highlights the regulatory role of working hours when working from home and examines the mediation of self-efficacy in the association between family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity. This study also confirms the gender differences in work-from-home productivity which has been previously inconsistent in the literature. Managerially, the research has practical implications for employers, managers, and the government. Employers should adopt family-friendly policies and offer training programmes to enhance work-from-home productivity. Employers need to pay extra attention to their female employees’ work and family responsibilities and guarantee positive working outcomes through online surveys and two-way communication strategies. Professional training and work-from-home skill development programmes should be provided to boost employee confidence and self-efficacy. Governments and employers should also consider implementing regulations on the duration of working-from-home to avoid negative impacts on work efficiency and family–work conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

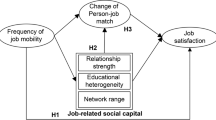

Role of job mobility frequency in job satisfaction changes: the mediation mechanism of job-related social capital and person‒job match

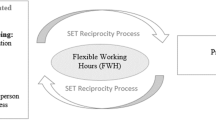

An investigation into employees’ factors of flexible working hours (FWH) for productivity in Saudi: a mixed qualitative triangulation

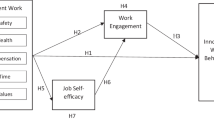

Decent work and innovative work behavior of academic staff in higher education institutions: the mediating role of work engagement and job self-efficacy

Introduction.

This study investigated the association between family–work conflict (FWC) and work-from-home productivity (WFHP) among Taiwanese work-from-home employees in the COVID-19 context. Although Taiwan is recognised as having one of the most successful pandemic response models in Asia and worldwide, the country experienced a COVID-19 outbreak during the time of the study, with more than 14,634 cases recorded as of June 2021. This was considered to be the first wave of COVID-19 in Taiwan. Many preventive measures were implemented during this period including mandatory social distancing, which included a requirement to work from home for many employees. Taiwanese companies and schools adapted to remote work and learning, respectively, and working from home became a key means of social distancing.

Various enterprises worldwide, especially leading companies in developed countries, had long considered the work-from-home (WFH) model as one of the new forms of work, even before COVID-19 appeared (Vyas and Butakhieo, 2021 ). Academics have been interested in the topic of WFH and have undertaken associated studies (Bloom et al., 2014 ; Crosbie and Moore, 2004 ; Dockery and Bawa, 2014 ; Nakrošienė et al., 2019 ). WFH has been a work option for both employers and employees for some time (Rupietta and Beckmann, 2018 ). However, with the COVID-19 outbreak, WFH became mandatory in some countries (Bonacini et al., 2021 ; Wong et al., 2020 ; Yabe et al., 2020 ), attracting the attention of many scholars around the world (Davies, 2021 ). The present research on WFH focuses not only on policy aspects but also on the quantitative aspects that explore the effects of WFH on human psychology (Galanti et al., 2021 ; Song and Gao, 2020 ), job satisfaction, work engagement (WE) (Ahmadi et al., 2022 ; Irawanto et al., 2021 ; Purwanto et al., 2020 ), and work-life balance (WLB) (Putri and Amran, 2021 ).

Other studies have investigated employee performance and WFHP (Afrianty et al. 2022 ; Farooq and Sultana, 2021 ; Feng and Savani, 2020 ; Morikawa, 2022 ; Ramos and Prasetyo, 2020 ; Sutarto et al., 2021 ). Feng and Savani ( 2020 ), for example, examined the gender gaps in WFH outcomes under pandemic conditions. The authors found that the pandemic generated a gender gap in perceived WFHP. The authors argued that women were expected to dedicate more time to the family when both parents worked from home during the day and schools were closed. On the other hand, Morikawa’s ( 2022 ) research on WFH in Japan during the pandemic revealed that WFHP reached ~60–70% of normal workplace productivity. The study also found that productivity was lower for people and businesses who had begun practicing WFH only after the pandemic had spread. The potential impact of the pandemic on working from home (WFH) and productivity was further investigated by Farooq and Sultana ( 2021 ). They found a negative association between WFH and productivity, including a moderating effect of gender on the relationship. Sutarto et al. ( 2021 ) explored the association between employee mental health and productivity during the crisis to ascertain whether the relationship differed depending on select socio-demographic characteristics. The authors found a negative correlation between the WFH employees’ psychological wellbeing and productivity. Further, gender, age, education level, job experience, marital status, and number of children were found to have no association with productivity. In contrast, the issue of working hours has been shown to be negatively related to productivity (Collewet and Sauermann, 2017 ). Nonetheless, based on our literature review, it appears that only a few works have assessed the effect of working hours on WFH productivity within the COVID-19 context.

Although various studies have focused on WFH in the COVID-19 period, as discussed above, and even though many have explored WFHP and the mediating effect of WE, no works have explored the mediating effect of self-efficacy (SE) in terms of predicting WFHP, especially when family–work conflict (FWC) is treated as an antecedent. In terms of the effect that demographic variables have when predicting WFH performance, the productivity effect remains inconsistent. Hanaysha ( 2016 ) suggested broadening the sample to different industry employees in WE and productivity studies to generalise the findings. Additionally, based on our literature review, few studies to date relate to WFHP in Taiwan during the pandemic period, especially for the employees of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). During the first wave of the pandemic, the Taiwanese Government applied strict social distancing policies, including WFH (Cheng et al., 2020 ). This study is therefore pioneering in exploring WFHP in Taiwan during the pandemic period.

Consequent to these research gaps, the differences present in the findings in the literature, and answering the call of Hanaysha ( 2016 ), the present study is based on role conflict and resource drain theories, the FWC literature, and previous empirical studies. It proposes a multiple mediator model to predict the WFHP of employees in Taiwan’s SMEs during the COVID-19 level 3 alert. The primary purpose of this research is to expand on what is currently known about the effects of FWC on WFHP by investigating the mediating effects of WE and SE to determine their effect mechanism. The secondary purpose of the research is to investigate whether the element of working hours moderates the effects of FWC on WFHP to address the research gap in the existing literature concerning the role of working hours in work-from-home productivity, and the below research questions (RQs) which served as a roadmap for the current study:

RQ1: How does Family–Work Conflict affect Work-from-Home Productivity, and what is the mechanism behind their effect?

RQ2: How do working hours moderate the negative association between Family–Work Conflict and Work-from-Home Productivity?

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: the section “Literature review” provides a comprehensive review of the pertinent literature, including the theoretical background, contextual literature, and core literature, and also presents the research model and hypotheses. Section “Methodology” outlines the research methodology and details the data collection process, while the section “Findings” presents the findings of the study. Finally, the section “Discussion” presents the discussion, conclusions, and comments on the significance and limitations of this research.

Literature review

Working from home: from a flexible working method to a mandatory requirement in the covid-19 era.

WFH refers to the practice of working from home (away from the main office) on one or more days per week (Hill et al., 2003 ). WFH offers employees a multitude of advantages such as flexibility and autonomy, balancing work, performing non-work activities, saving on commuting time, and the additional conveniences of WFH (Afrianty et al., 2022 ; O’Hara, 2014 ). The concept of WFH, first advanced in the 1970s as telework, is the option to perform work at different locations based on technological assistance (van Meel, 2011 ). WFH is a flexible working method for employees that many enterprises and organisations have used for some time (Farooq and Sultana, 2021 ). It has long been linked to workplace programmes that promote WLB and has been frequently used by large corporations in many Western countries to support WLB (Mestre, 1998 ). From a human resource management (HRM) perspective, the positive influence of WFH on employee work attitudes, behaviour, and performance is widely recognised (Crosbie and Moore, 2004 ).

With the COVID-19 outbreaks, WFH has been implemented in 213 countries and territories worldwide (Mukhtar, 2020 ). The ongoing pandemic has brought about significant changes in the way that people work and, in some cases, whether they work at all. A considerable number of individuals have chosen to stay in their homes, either to protect themselves from the disease or due to government-imposed shelter-in-place orders (Farooq and Sultana, 2021 ). Furthermore, many governments have strictly applied social distancing policies, limited mass gatherings, reduced the number of workers in offices, promoted WFH, and applied information technology media to work online (Brodeur et al., 2021 ). Following the implementation of social distancing policies, numerous companies worldwide are still planning to reduce the number of employees working in traditional office settings, thereby enabling and promoting remote work opportunities for their workforce (Xiao et al., 2021 ). As a result, the pandemic has prompted governments and organisations to reconsider their perspectives on WFH and its effectiveness (Farooq and Sultana, 2021 ), with WFH becoming a mandatory government requirement during the pandemic period (Vyas and Butakhieo, 2021 ; Waizenegger et al., 2020 ).

Work from home during the COVID-19 Level 3 Alert in Taiwan

As with other countries and territories worldwide, Taiwan is not immune to the impacts of the pandemic (Lei and Klopack, 2020 ). Although considered one of the more successful countries in fighting the disease (Chien et al., 2020 ; Shokoohi et al., 2020 ) with only 1244 cases recorded up to May 2021, Taiwan faced the first wave of the pandemic with 14,634 cases as reported in June 27 (Taiwan Centers for Disease Control, 2022 ). Currently, the COVID-19 pandemic is a level 3 alert. Prevention solutions are being strictly applied, social distancing is required, and WFH is being promoted by the government and businesses (Kuo, 2021 ; Tan et al., 2021 ).

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Theoretical foundation, role conflict theory.

Kahn et al. ( 1964 ) proposed the Role Conflict Theory, wherein role conflicts address the “simultaneous occurrence of two (or more) sets of pressures, such that compliance with one would make more difficult compliance with the other” (Kahn et al., 1964 ). FWC is rooted in role conflict theory and posits that individuals possess a limited pool of resources, such as time and energy, which must be allocated among various roles. Consequently, conflicts arising from multiple roles can lead to stress and subsequently diminish employee engagement, efficiency, and productivity (Foy et al., 2019 ; Garg, 2015 ; Wang et al., 2022 ).

Resource drain theory

Resource Drain Theory states that individuals are unable to match the expectations of an additional domain because they must make compromises when distributing their time and energy across two domains (Rothbard and Edwards, 2003 ). According to this theory, the conflict between family and work roles arises frequently due to the finite resources that individuals have, such as energy and time, which must be allocated between the demands of their personal lives and any professional responsibilities (Bozoğlu Batı and Armutlulu, 2020 ). Investing resources in one domain increases the likelihood of not being able to meet the expectations of the other domain. This notion is based on the understanding that work and family are interconnected and intertwined, rather than being separate and distinct entities (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985 ; Windeler et al., 2017 ). Role conflict theory and resource drain theory constitute the theoretical background underpinning the present study.

Hypothesis development

Family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity.

Work and family, formerly examined as two independent systems, have been investigated as one system more recently, referred to as the work–family system (Tsang et al., 2023 ). Working parents can suffer from stress due to the intersection between the family and work domains which manifests as a sense of FWC. This is when the demands or expectations of one role are incompatible with the demands or expectations of another role, and conflicts arise (Ren and Foster, 2011 ). The more time and energy individuals allocate to one role, the less time and energy they have available for the other role. Insufficient time and energy to fulfill the demands of both family and job responsibilities are therefore key factors contributing to FWC (Marks, 1977 ). In the setting of FWC, various studies have identified two distinct types of role conflict: work interfering with family duties, known as work–family conflict (WFC), and family interfering with work responsibilities, known as FWC (Gutek et al., 1991 ). For research purposes, this research explores FWC as a separate factor. Meanwhile, productivity is commonly defined as the measure of output or quantity of production that results from performance behaviours along with external contextual factors and opportunities (Farooq and Sultana, 2021 ). In the current study, it refers to the employees’ perceived work productivity during the practice of WFH.

FWC has been explored to date in studies on employee satisfaction, engagement, performance, and productivity, including during the COVID-19 period (Graham et al., 2021 ; Karakose et al., 2021 ; Kulik and Ramon, 2022 ). Several studies have found that conflict between family and work had negative consequences on emotional health, physical well-being, and life satisfaction (Cohen and Liani, 2009 ; Schieman et al., 2003 ; Singh and Nayak, 2015 ). As a result, FWC can lower employee productivity and performance (Mohsin and Zahid, 2012 ). For example, an employee’s personal issues spilling into the workplace can cause the employee to waste time and lose focus on the job (Perry, 1982 ). Therefore, the person must rearrange their schedule to accommodate the competing demands of family and work (Barnett, 1994 ).

Another issue that arises is psychological interference which refers to the transfer of moods or emotional states generated in the work domain to the family domain (Hughes et al., 1992 ). At home, psychological interference has an impact on a worker’s mood and energy levels which can subsequently contribute to role conflicts, in turn negatively impacting the employee’s performance at work. Home-to-work spillover, according to Crouter ( 1984 ), is defined as the employee’s distressing objective demands and thoughts on family matters. Additionally, several prior research es have identified a significant negative association between FWC and work productivity (Anderson et al., 2002 ; Reina et al., 2017 ; Witt and Carlson, 2006 ). Based on this theorisation, it is hypothesised that:

H1: FWC has a significant negative effect on WFHP

Work engagement and self-efficacy as mediators

“ WE refers to employees emotional commitment to their company. Engagement is described as the ‘harnessing of the self of organisation members to their job roles; people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally in engagement during role performances” (Nguyen et al., 2021 , p. 205). Moreover, WE is recognised as a positive and fulfilling state of mind related to work. It is characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption in one’s job or tasks (Nguyen et al., 2021 ; Schaufeli et al., 2002 ). Employees are considered to be engaged with their organisations when they put their all into their work (Nguyen et al., 2021 ). In this study, the definition was adapted to the WFH context. Previous research found that employees who work in a resourceful workplace were energised, enthusiastic, and immersed in their tasks (Bakker and Demerouti, 2014 ; Suan and Nasurdin, 2014 ). Stressful, conflictual, and demanding settings, on the other hand, can undermine employee WE (Coetzee and De Villiers, 2010 ). As a result, FWC is able to negatively affect WE. Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H2: FWC has a significant negative effect on WE.

Additionally, WE is a critical motivational concept that leads to positive outcomes (C. Barnes and E. Collier, 2013 ), and research suggests that engaged employees contribute to positive organisational outcomes. Business leaders acknowledge that highly engaged employees can significantly enhance productivity and improve a firm’s performance, especially in rapidly evolving markets (Tsang et al., 2023 ). In simpler terms, engaged employees exhibit enthusiasm toward their work, feel a sense of happiness when working for their company, and demonstrate an eagerness to come to work each day (Hanaysha, 2016 ). Furthermore, engaged employees are critical to their organisations’ ability to maintain a competitive advantage and increase work productivity (Albrecht et al., 2015 ; Hanaysha, 2016 ; Takahashi et al., 2022 ). Studies also indicate that WE positively affect employee performance and productivity. Enhancing employee engagement is a positive way to improve work performance and productivity (Demerouti and Cropanzano, 2010 ; Geldenhuys et al., 2014 ). Aryee et al. ( 2016 ) and Şahin and Yozgat ( 2021 ) found that WE mediate the significant negative relationship between FWC and work performance. Based on the above discussion, we argue that in a WFH setting, employee engagement plays a mediating role in the negative effect of FWC on WFHP. Hence, it is hypothesised that:

H3: WE has a significant positive effect on WFHP.

H4: WE mediates the negative relationship between FWC and WFHP.

SE is a critical personal resource that mitigates the negative effects of job demands (Mihalca et al., 2021 ; Perrewé et al., 2002 ) because SE pertains to the individual’s beliefs in their own capabilities to meet the demands of a given situation and successfully perform specific tasks (Mihalca et al., 2021 ). In this study, SE is defined as occupational self-efficacy based on the self-efficacy energy concept of Rigotti et al. ( 2008 ), which describes the level of SE during WFH. As mentioned above, resource drain theory proposes that people who are heavily invested in one position will inevitably lack the resources required to fulfil their other responsibilities. People with FWC devote more time and attention to their family responsibilities, leaving them with fewer resources to meet their professional demands (Peng et al., 2010 ). Cohen and Kirchmeyer ( 1995 ) suggest that having inadequate resources available for work may jeopardise an employee’s ability to fulfil job tasks, lowering their sense of personal competence. Additionally, research findings indicate that trainees who experience more situational constraints, such as conflicting time demands, were less likely to believe that they could master the training materials successfully (Mathieu et al., 1993 ). Prior research also indicates a negative association between FWC and SE (Netemeyer et al., 1996 ; Peng et al., 2010 ). Therefore, the below hypothesis is stated:

H5: FWC has a negative effect on SE.

Previous studies have demonstrated that employees with high self-efficacy (SE) beliefs are more likely to possess confidence in their ability to effectively fulfil the job requirements, even in the presence of various job-related stressors (Nguyen et al., 2021 ; Stetz et al., 2006 ). Therefore, their productivity also tends to be relatively high. According to Walumbwa et al. ( 2005 ), a higher level of job self-efficacy is associated with more positive work attitudes. Additionally, employees with a high level of self-efficacy are more likely to enhance their work performance and productivity (Tabatabaei et al., 2013 ). Therefore, the below hypothesis is stated:

H6: SE has a significant positive effect on WFHP.

Furthermore, there are currently few studies investigating the mediation of SE in the association between FWC and WFHP, especially in the context of the pandemic. However, several studies found that there is a mediation due to SE in the association between FWC and job satisfaction (Peng et al., 2010 ) and between job performance and other input variables (Beltrán-Martín et al., 2017 ). As a result, we argue that SE is a mediator in the relationship between FWC and WFHP, and we hypothesise that:

H7: SE mediates the negative relationship between FWC and WFHP.

Working hours as a moderator between family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity

Collewet and Sauermann ( 2017 ) found that working hours negatively relate to productivity. Moreover, role conflict theory and resource drain theory maintain that people have limited resources, such as time and energy, to distribute across several responsibilities (Kahn et al., 1964 ). Based on this view, an increase in working hours can cause conflicts that affect productivity (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985 ). In the present study, working hours are measured by the number of assigned WFH days (WFHDs) per week per employee. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H8: The negative relationship between FWC and WFHP is stronger for employees with more work-from-home days than for the employees with less work-from-home days.

Control variables

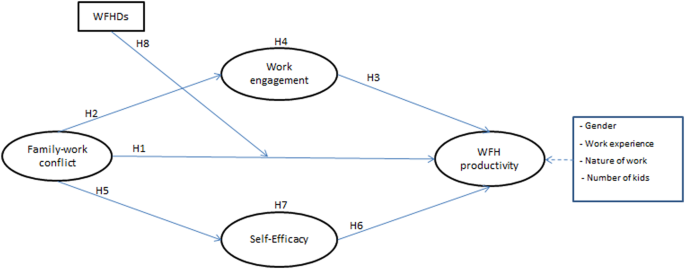

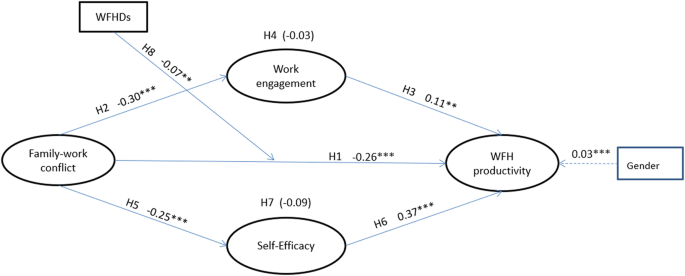

Some demographic variables, including gender, age, work experience, the work field, and a number of children, may significantly affect WFHP (Kattenbach et al., 2010 ; Schieman and Glavin, 2008 ; White et al., 2003 ). According to traditional views, work is the role of men while housework and family responsibilities are the duties of women (Gutek et al., 1981 ). This custom has survived despite changes in recent decades. Women continue to devote more time to their children, the household, and the family than men do (Peng et al., 2010 ). Taiwan is strongly influenced by Confucianism, so the view that housework is the duty of women is very evident (Takeuchi and Tsutsui, 2016 ). Therefore, the present study also examines whether WFHP varies between the different categories of these variables. The research model is drawn in Fig. 1 .

A framework for analysing the relationship between family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity, with work engagement and self-efficacy as mediators and work-from-home days (WFHDs) as moderators.

Methodology

Research design.

On the basis of the existing literature, the current study plans to tackle two research questions: ‘How does FWC affect WFHP and what is the mechanism behind the effect?’ and ‘How do working hours moderate the negative association between FWC and WFHP?’ To answer these two research questions, the present study adopted the form of descriptive research because the prior studies have demonstrated that descriptive research explores the relationships between the selected variables (de Vaus, 2001 ; Dulock, 1993 ). Based on two well-known theories, namely the role conflict and resource drain theories, we propose a multiple mediator model to investigate whether FWC has a negative effect on WFHP through the mediating role of WE and SE, as well as whether working hours play a moderating role in the negative association between FWC and WFHP. The research findings will have some theoretical and practical implications in the field.

Research approach

Based on the research design, our study adopted a quantitative approach. The primary data was collected based on a questionnaire survey and then processed using specialised statistical software, SPSS, and AMOS, to test the proposed hypotheses. We adopted the quantitative approach for the following reasons:

Firstly, quantitative research is a systematic and empirical approach that gathers and analyses data using statistical and numerical methods in order to test hypotheses and make generalisations about a population (Mohajan, 2020 ). Through the moderating roles of work engagement and self-efficacy, this method is good for studying complex relationships between the selected variables, such as the association between FWC and WFHP.

Secondly, using a quantitative approach in the current study allowed the authors to determine the strength and direction of the relationships between the variables (Choy, 2014 ; Nardi, 2018 ; Queirós et al., 2017 ) as well as to test the mediating effect of work engagement and self-efficacy on the relationship between family–work conflict and work from home productivity. This was achieved through statistical methods such as regression analysis and path analysis, which helped us identify the relationships between the variables and estimate their effects (Bazeley, 2004 ; Somekhe and Lewin, 2005 ).

Thirdly, a quantitative approach allowed the authors to gather data from a large sample of the population compared to the qualitative approach, which increased the external validity of the findings (Yilmaz, 2013 ).

A printed questionnaire was developed to have two sections. The first section measured the respondents’ basic information. The second section included subscales to measure four constructs, namely FWC, WE, SE, and WFHP.

The first section was comprised of seven questions. The first question, gender, was categorised as (1) female and (2) male. The second question asks for the participant’s age, with four levels (1) 18–30, (2) 31–40, (3) 41–50, and (4) more than 50. The third question, working experience, was divided into four categories, including (1) <2 years, (2) 2–5 years, (3) 6–10 years, and (4) more than 10 years. The fourth question, the working field, included five options, namely: (1) production management, (2) marketing, (3) administrative affairs, (4) financial accounting, and (5) other. The fifth question, the number of children, consisted of four categories including (1) no child, (2) 1 child (3) 2 children, and (4) more than 2 children. The sixth question asked the respondents for the number of WFH days they worked during the COVID–19 level 3 alert in 2021 with four options, specifically (1) <2 days, (2) 2–3 days, (3) 4–5 days, and (4) more than 5 days. The final question, a yes/no question, asked the respondents whether they WFH during the COVID-19 level 3 alert from May 2021 onward. The purpose of this question was to eliminate from our research sample respondents with the answer “no” to ensure that the research object, employees with WFH experiences during the COVID-19 period, was valid.

The second section comprised four subsections. The first subsection, FWC, included five items adapted from Netemeyer et al. ( 1996 ): “My home life interferes with my responsibilities at work, such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, and working overtime”, for example. The second subsection was comprised of nine items adapted from Schaufeli et al. ( 2006 ) to assess WE. An example item is “When I work from home, I feel full of energy.” The third subsection, SE, consisted of six items adapted from Rigotti et al. ( 2008 ). An example item is “I can stay calm when I encounter difficulties at work because I can rely on my own abilities.” The final subsection, WFHP, included seven items adapted from Irawanto et al. ( 2021 ): for example, “I’m productive when I work from home.”

In this study, all of these constructs were self-reporting scales using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The original Cronbach’s Alpha value for the constructs was >0.6 (Nunnally, 1978 ).

Instrument validity and reliability

The instrument’s validity and reliability were ensured. In the beginning, the constructs were chosen from prior studies. After that, they were adjusted for the current investigation. To collect data in Taiwan, the research team employed a multi-step process. Firstly, two high school English teachers translated the original English questionnaire into Chinese. Subsequently, two different English teachers performed a back-translation to ensure the validity of the instrument. Additionally, three professionals in the field of human resource management were invited to assess the suitability of the questions. To enhance face validity, five employees completed the survey and provided feedback for further improvements. A pilot test involving 50 participants was then conducted to ensure comprehensibility and ease of answering the questions. It’s important to note that these participants were excluded from the official survey. Prior to administering the official survey, Cronbach’s alpha value was pre-tested using the pilot test data. The item’s total correlation exceeded 0.3, and Cronbach’s alpha values for the four constructs in the pilot test surpassed the minimum acceptable value of 0.60 (Nunnally, 1978 ).

Sampling method

In the current study, we adopted a non-probability convenience sampling technique to recruit the research participants and select the sample size. Although probability sampling techniques are generally preferred in quantitative research due to their ability to ensure representativeness and to reduce the risk of bias in the sample (DeVellis and Thorpe, 2021 ), other researchers also argue that in some circumstances, non-probability sampling may be used when the population of interest is difficult to define or when the sample size is small and the research question is exploratory in nature (Creswell and Creswell, 2017 ).

In the present study, our population of interest was difficult to define. Moreover, our study was in the context of COVID-19, which can change rapidly within hours, so we, therefore, needed to obtain data quickly for the exploratory research questions. Moreover, other researchers have argued that despite its limitations, non-probability sampling can still provide valuable insights and serve as a starting point for future studies that utilise probability sampling (Creswell and Creswell, 2017 ). Therefore, we believe that it was the most appropriate method for our study given the specific circumstances and research questions.

Data collection and procedure

The questionnaire was developed specifically for the purpose of gathering data from WFH employees in Taiwan. Because it is impossible to know the total number of the target population, we calculated the minimum sample size using the formula proposed by Tabachnick and Fidell ( 1996 ) in addition to regression analysis: n = 50 + 8 ∗ m (where m is the number of independent variables). Other researchers have similarly noted that larger sample sizes provide a more accurate representation of the characteristics of the populations that they are drawn from (Cronbach et al., 1972 ; Marcoulides and Heck, 1993 ). Therefore, the present study collected higher than the minimum sample size suggested. With the support of the Rotary International Group in Taiwan, a questionnaire was sent directly to 1307 employees of SMEs in Taipei (8 enterprises), New Taipei (7 enterprises), Taichung (7 enterprises), and Tainan (8 enterprises). The questionnaire was distributed between November 11 and December 29, 2021. Returned questionnaires numbered 1177, with a response rate of 90.1%. In order to increase the response rate, besides support from the Rotary International Group, we also gave the respondents gifts, such as medical masks or convenience store vouchers of 20 NTD.

Because of the purpose of the research, the research participants had to be employees who had WFH during the COVID-19 period. As a result, after collecting the data, we eliminated cases where there was no work-from-home status, cases where data was missing, and other outliers; 785 valid cases were used for the analysis. The participants’ information is shown in Table 1 .

Data analysis strategy

The SPSS v.22 programme was used to conduct the primary analysis and descriptive statistical analysis. To assess univariate normality, cases with z scores exceeding ±3.29 ( p < 0.001) were identified as outliers, following the approach outlined by Tabachnick et al. ( 2007 ). In order to mitigate issues of multicollinearity, all variance inflation factors (VIFs) needed to be <5 (Hair et al., 2019 ), as recommended by Hair et al. ( 2019 ). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the AMOS v.20 software to examine the convergent and discriminant validity. Finally, the proposed hypotheses were tested using Process Macro (Model 5).

Common method variance and descriptive statistics

Common method variance (CMV) refers to the potential bias that arises when data for two or more variables are collected from the same source, leading to a correlation between the variables that may be misleadingly inflated (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). This study collected data from the same source utilising self-reported data which could lead to common technique bias. Harman’s single-factor matrix was used to determine the CMV of all items. The results show that the factor with the highest variance was 30.42%, which is less than the threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). Hence, there was no CMV in the present study. All VIFs were <5 (Hair et al., 1995 ). Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the study construct.

Measurement model evaluation

To evaluate the measurement model, a two-step analysis was conducted. Firstly, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to assess the construct validity of the variables included in the study. A factor loading of 0.5 or higher (Hair et al., 1995 ) was used as the threshold to determine satisfactory construct validity. Additionally, an eigenvalue of at least 1 was considered, and the Varimax rotation method with Kaiser normalisation was applied during the analysis. The results of the PCA are presented in Table 3 with no items omitted.

After performing the PCA, we also checked the Cronbach’s alpha values of the main variables. The results indicate that all Cronbach’s alphas were higher than 0.8, thus exceeding the minimum permitted value of 0.60 (Nunnally, 1978 ). In the second step, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilised to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity. Construct reliability was assessed by examining the composite reliability (CR) values with a threshold of 0.70 commonly considered acceptable (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988 ). All factor loadings were higher than 0.6, and all were significant (Hair et al., 2010 ). All average variance extracted (AVE) estimations exceeded 0.50, indicating convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010 ) (see Table 4 ).

Table 5 further demonstrates that the CFA measurement model (fit indices: CMIN/df < 3, RMSEA < 0.05, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.90, Incremental Fit Index (IFI) > 0.90) implies a good level of fitness. Table 6 shows that all correlations between each pair of constructs were less than the square root of the AVE, indicating that the discriminant validity was sufficient.

Hypothesis testing

Preacher and Hayes’s ( 2004 ) mediation analysis, i.e. PROCESS Macro (model 5), was employed to test the proposed hypotheses. The results show that FWC was negatively related to WFHP ( β = −0.26, p < 0.001), supporting H1. This finding is in accordance with the previous findings demonstrating the effect of FWC on WFHP (Anderson et al., 2002 ; Reina et al., 2017 ; Witt and Carlson, 2006 ). FWC negatively influenced WE ( β = −0.30, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Although this relationship has been identified in previous studies (Bakker and Demerouti, 2014 ; Suan and Nasurdin, 2014 ), our results confirm the negative relationship between FWC and WE in the context of COVID-19. Furthermore, WE was positively related to WFHP ( β = 0.11, p < 0.01), supporting H3. This finding is in line with the previous studies (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008 ; Markos and Sridevi, 2010 ). Additionally, the PROCESS (model 5) showed that WE mediated the relationship between FWC and WFHP ( β = −0.03 , LLCI = −0.0634 , ULCI = −0.0063), supporting H4. This study has explored the mediator of WE in relation to the association between FWC and WFHP (Aryee et al., 2016 ; Şahin and Yozgat, 2021 ), and this mediating role was also evident in the COVID-19 context. On the other hand, FWC was negatively associated with SE ( β = −0.25, p < 0.001), confirming H5 and the previous findings (Netemeyer et al., 1996 ; Peng et al., 2010 ). SE positively affects WFHP ( β = 0.37, p < 0.001), supporting H6. This result echoes the previous findings (Tabatabaei et al., 2013 ). In addition, SE mediated the association between FWC and WFHP ( β = −0.09, LLCI = −0.1242 , ULCI = −0.0621), confirming H7. This is one of the notable findings of our study. As a result, these research findings indicate that FWC negatively affects WFHP and that this effect’s mechanism includes both direct and indirect effects through the partial mediation roles of WE and SE. The findings solve the first research question.

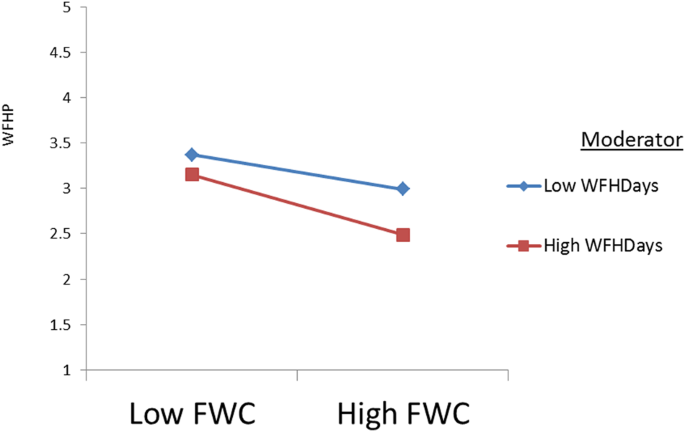

The results of the PROCESS also indicate that the interaction between FWC and WFHDs ( β = −0.07, SE = 0.02, t = −2.87, p < 0.01, LLCI = −0.1150, ULCI = −0.0216) negatively affected WFHP. The slope test indicated that the negative effect of FWC on WFHP was stronger for employees with more work-from-home days than for those with less, supporting H8. The findings show the role of WFHDs in the negative relationship between FWC and WFHP. According to the research findings, the negative relationship between FWC and WFHP will reduce when the employees are assigned fewer WFHDs. The moderating role of WFHDs can be attributed to the employees’ limited resources, such as time and energy, that they need to distribute across several responsibilities (Kahn et al., 1964 ). As a result, an increase in working hours may result in conflicts that reduce productivity (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985 ). We examined the conditional effect of FWC on WFHP at three values of WFHDs: at the mean value ( β = −0.28, p < 0.001), at 1 SD below ( β = −0.14, p < 0.01), and at 1 SD above the mean ( β = −0.35, p < 0.001). The interaction plot is depicted in Fig. 2 .

WFHDs strengthen the negative relationship between FWC and WFHP. Note: Work-from-home days: WFHDs, family–work conflict: FWC, work-from-home productivity: WFHP.

The effect of the control variables, such as gender, age, work experience, working field, and the number of children, on WFHP, was investigated to determine whether there were any significant differences between the levels of the control variables. The ANOVA results indicated that there were no significant differences between the levels of work experience, working field, and number of children in relation to WFHP. In contrast, there were significant differences between males ( M = 3.60, SE = 0.03) and females ( M = 3.37, SE = 0.04) in relation to WFHP ( F (1, 783) = 20.478, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.03). This difference can be attributed to the strong influence of Confucianism in Taiwan which results in many believing that housework is the duty of women (Takeuchi and Tsutsui, 2016 ). Therefore, the WFHP among women was lower than that among men. Table 7 presents the ANOVA table, and Fig. 3 presents the study’s model for the results.

Work engagement and self-efficacy mediate the relationship between family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity. Work-from-home days (WFHDs) strengthen the negative relationship between family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity. Note: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, coefficients for indirect effects are in parentheses.

This study has proposed a new model to investigate the association between FWC and WFHP in Taiwan during the COVID-19 period. All proposed hypotheses in the research were found to be supported. The findings indicate that FWC negatively affects WE, SE, and WFHP because, according to role conflict theory and resource drain theory, people have a limited number of resources (in terms of time and energy) to allocate to various roles. Consequently, conflicting roles can cause stress and reduce employee engagement, efficiency, and productivity (Foy et al., 2019 ; Garg, 2015 ; Wang et al., 2022 ). Moreover, resource drain theory indicates that investing resources in one function raises the likelihood of not being able to fulfil the expectations of the other. Therefore, employees with FWC may exhibit reduced productivity. These findings echo the prior studies (Anderson et al., 2002 ; Bakker and Demerouti, 2014 ; Coetzee and De Villiers, 2010 ; Suan and Nasurdin, 2014 ; Mohsin and Zahid, 2012 ; Peng et al., 2010 ; Reina et al., 2017 ).

The results show that when WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic, employees could encounter conflicts with their family responsibilities which influenced their productivity, SE and WE (Graham et al., 2021 ; Karakose et al., 2021 ; Kulik and Ramon, 2022 ; Peng et al., 2010 ). In contrast, when these conflicts were controlled, SE, WE, and productivity were enhanced (Schieman et al., 2003 ). Furthermore, our study found that WE was an antecedent of WFHP, in that WE positively affects WFHP. This can be attributed to employees with a higher level of WE being enthusiastic about their work and happy to work every day (Hanaysha, 2016 ). Engaged employees are thus critical to increased work productivity in their organisations (Albrecht et al., 2015 ; Hanaysha, 2016 ; Takahashi et al., 2022 ). These findings echo the previous findings that work productivity and work performance are influenced by WE (Demerouti and Cropanzano, 2010 ; Geldenhuys et al., 2014 ). Similarly, the positive association between SE and WFHP was confirmed in our study. Various studies on HRM determined that a higher level of SE will increase a positive work attitude, performance, and productivity (Lim and Loo, 2003 ; Tabatabaei et al., 2013 ; Walumbwa et al., 2005 ), and our research confirms the relationship in the WFH context under COVID-19 conditions.

Our findings explored the partial mediation of WE in the relationship between FWC and WFHP. WE has been identified as a mediator between FWC and work performance or productivity (Aryee et al., 2016 ; Şahin and Yozgat, 2021 ). One of the interesting results of our research was the partial mediation of SE in the negative association between FWC and WFHP. As discussed in the literature review, there is currently little research assessing the mediation of SE in the link between FWC and WFHP, particularly in light of the current pandemic situation. Limited studies have discovered that SE plays a mediating function in the relationship between FWC and job satisfaction (Peng et al., 2010 ) or that there is a mediation function due to SE in the association between job performance and other input factors (Beltrán-Martín et al., 2017 ; Walumbwa and Hartnell, 2011 ). This is a striking finding in our research, specifically how SE mediates the negative association between FWC and WFHP, especially in the COVID-19 context.

Although not yet noted in studies on WFH in the pandemic context, our research has established the moderating role of working hours. The present study indicates that during the COVID-19 situation in Taiwan, an increase in FWC caused a decrease in WFHP and that this negative relationship was stronger for employees with more work-from-home days than for those with less. This is in line with the role conflict theory and resource drain theory perspectives (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985 ), and previous HRM studies (Collewet and Sauermann, 2017 ; Kattenbach et al., 2010 ). Further, WFHP was found to be higher for Taiwanese male employees than for females. This echoes the prior research on HRM (Bezabih et al., 2016 ; Sandström and Hällsten, 2008 ). However, although Taiwanese society is modernising, the responsibility of taking care of the family still belongs to women (Takeuchi and Tsutsui, 2016 ). This is one of the main causes of the differences in the results.

In conclusion, our findings have determined that WE and SE partially mediate the negative association between FWC and WFHP. The findings provide evidence for the importance of psychological factors when it comes to explaining the impact of family–work conflict on WFHP during the pandemic. Specifically, employees with higher levels of WE and SE are less likely to experience negative effects on their productivity as a result of FWC. One of our new findings, which has filled in the research gaps in the existing literature, is the partial mediating role of SE in the association between FWC and WFHP.

Additionally, the findings show that working hours moderate the association between FWC and WFHP, with the negative effects of FWC being stronger for employees who spend more time working from home. These findings are important for organisations and employees as they navigate the challenges of WFH arrangements in light of the pandemic.

Theoretical implications

Firstly, our study is one of the pioneers in terms of proposing a predictive model for WFHP among small and medium-sized enterprise employees in Taiwan during the COVID-19 period. We propose that our research adds to the knowledge base on remote work and remote worker productivity during the pandemic. Furthermore, the research results are notable because they show how family and work problems affect the productivity of workers who have had to switch to full-time WFH.

Secondly, our research answered Hanaysha’s ( 2016 ) call to focus on a larger sample of SME employees, a factor that is often neglected in previous studies on WFH, especially in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research fills in a gap in the literature on the regulatory role of working hours in the context of WFH, especially in terms of the association between FWC and WFHP during the pandemic, by showing that working hours are different when it comes to the relationship between FWC and WFHP. Although prior research has reported inconsistent results concerning whether WFHP differs between men and women, our study demonstrates that WFHP does vary between men and women, adding to the body of evidence for a gender difference in WFHP.

Thirdly, an important extension of our study can be found in the inclusion of SE in the predictive model of WFHP for workers in Taiwan during the pandemic. Our study adds to the body of knowledge about the mediation of SE in the negative association between FWC and WFHP that has largely been overlooked in previous research.

Managerial implications

Our findings provide some practical implications for managers, the government, and management.

Firstly, FWC was found to be one of the determinants of the decrease in WFHP. This implies that the harmonious resolution of family and work conflicts will contribute to improving the employees’ working productivity in the process of WFH. Therefore, it is necessary for Taiwanese SMEs to transfer family-friendly human resource management practices and related policies from Western contexts to Taiwan. Moreover, employers who consider their employees to be a competitive resource may consider implementing family-friendly policies to help their employees balance work and family tasks. Our results show that employers and managers should pay extra attention to how women employees balance their work and family responsibilities.

Secondly, the current study provides evidence that WE improve employee productivity significantly, even in an emergency situation like COVID-19. Therefore, companies should place a high value on employee engagement and monitor their progress on a regular basis to ensure positive working outcomes. To do so, we strongly recommend employers undertake frequent online surveys during WFH to gain a thorough understanding of their employees’ levels of job engagement and FWC. As a result of such actions, employers will be able to establish appropriate methods for addressing emergent difficulties more quickly. Employers should use an online two-way communication strategy with their employees throughout the WFH time to allow employees to communicate their thoughts on their employment, challenges, and any concerns that may impair their productivity. If such attention were paid to employees, they would be more interested in and motivated by their work.

Thirdly, SE was found to be a mediator in the negative association between FWC and WFHP. Hence, employers should recognise their employees’ SE and provide support to improve it during their WFH time. Schunk et al. ( 2012 ) indicated that verbal persuasion and vicarious modelling are two sources of SE that employers can focus on. Offering professional training and WFH skills development programmes can greatly boost employee confidence and SE (verbal persuasion) and by assigning mentors and team leaders who exhibit highly self-efficacious behaviours during the WFH period (vicarious modelling). Companies can also provide employees with continual encouragement and emotional support by setting up communication channels to hear their voices during WFH time. In addition, companies can prioritise SE in their recruitment process by conducting staff selection interviews and requiring candidates to complete SE tests. This will assist businesses in attracting strong-SE employees.

Finally, although WFH is considered to be an effective solution in the context of the pandemic, our study reported a stronger negative relationship between FWC and WFHP in employees with an excessive WFH duration. It may therefore be advisable for governments and employers to consider implementing specific regulations on how long each person should work from home in a week. The duration should not be too long to avoid affecting work efficiency or an increase in FWC.

Limitations and suggestions for further study

There were several limitations in the research. Firstly, we adopted a non-probability convenience sampling technique, which limits the generalisability of our findings. We recommend that future studies employ a random sampling technique. Secondly, the cross-sectional design was a limitation because while it allowed us to trace the links between the investigated constructs, it did not allow us to determine whether there were any causal links between the variables. In addition, future studies should also test the moderating role of some of the demographic variables such as gender and number of children. This study only examined employees in Taiwan, and future research can include samples from more than one country to enable researchers to compare and contrast the results in light of the differences in national contexts and levels of socioeconomic development.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SL0ZQD or upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Afrianty TW, Artatanaya IG, Burgess J (2022) Working from home effectiveness during Covid-19: evidence from university staff in Indonesia. Asia Pac Manag Rev 27(1):50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.05.002

Ahmadi F, Zandi S, Cetrez ÖA, Akhavan S (2022) Job satisfaction and challenges of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study in a Swedish academic setting. Workforce-Costa Mesa 71(2):357–370

Google Scholar

Albrecht SL, Bakker AB, Gruman JA, Macey WH, Saks AM (2015) Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. J Organ Eff 2(1):7–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042

Article Google Scholar

Anderson SE, Coffey BS, Byerly RT (2002) Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: links to work–family conflict and job-related outcomes. J Manage 28(6):787–810. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800605

Aryee S, Walumbwa FO, Gachunga H, Hartnell CA (2016) Workplace family resources and service performance: the mediating role of work engagement. Afr J Manag 2(2):138–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2016.1175265

Bagozzi R, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structure equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16:74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2008) Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev Int 13(3):209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2014) Job demands—resources theory. In: Wellbeing: a complete reference guide. pp. 1–28

Barnett RC (1994) Home-to-work spillover revisited: a study of full-time employed women in dual-earner couples. J Marriage Fam 56(3):647–656. https://doi.org/10.2307/352875

Bazeley P (2004) Issues in mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches to research. Qual Res Organ Manag 141:156

Beltrán-Martín I, Bou-Llusar JC, Roca-Puig V, Escrig-Tena AB (2017) The relationship between high performance work systems and employee proactive behaviour: role breadth self-efficacy and flexible role orientation as mediating mechanisms. Hum Resour Manag J 27(3):403–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12145

Bezabih M, Holden S, Mannberg A (2016) The role of land certification in reducing gaps in productivity between male- and female-owned farms in rural Ethiopia. J Dev Stud 52(3):360–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1081175

Bloom N, Liang J, Roberts J, Ying ZJ (2014) Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q J Econ 130(1):165–218

Bonacini L, Gallo G, Scicchitano S (2021) Working from home and income inequality: risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19. J Popul Econ 34(1):303–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00800-7

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bozoğlu Batı G, Armutlulu İH (2020) Work and family conflict analysis of female entrepreneurs in Turkey and classification with rough set theory. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0498-0

Brodeur A, Gray D, Islam A, Bhuiyan S (2021) A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J Econ Surv 35(4):1007–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12423

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Barnes CD, Collier EJ (2013) Investigating work engagement in the service environment. J Serv Mark 27(6):485–499. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-01-2012-0021

Cheng HY, Jian SW, Liu DP, Ng TC, Huang WT, Lin HH (2020) Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med 180(9):1156–1163

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chien LC, Beÿ CK, Koenig KL (2020) Taiwan’s successful COVID-19 mitigation and containment strategy: achieving quasi population immunity. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.357

Choy LT (2014) The strengths and weaknesses of research methodology: Comparison and complimentary between qualitative and quantitative approaches. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci 19(4):99–104

Coetzee M, De Villiers M (2010) Sources of job stress, work engagement and career orientations of employees in a South African financial institution. South Afr Bus Rev 14:1

Cohen A, Kirchmeyer C (1995) A multidimensional approach to the relation between organizational commitment and nonwork participation. J Vocat Behav 46(2):189–202. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1995.1012

Cohen A, Liani E (2009) Work‐family conflict among female employees in Israeli hospitals. Pers Rev 38(2):124–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480910931307

Collewet M, Sauermann J (2017) Working hours and productivity. J Labor Econ 47:96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.03.006

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage, California

MATH Google Scholar

Cronbach L, Gleser G, Nanda HR, Rajaratnam M (1972) The dependability of behavioral measurements: The generalizability of scores profiles. Wiley, New York, pp. 1–33

Crosbie T, Moore J (2004) Work–life balance and working from home. Soc Policy Soc 3(3):223–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746404001733

Crouter AC (1984) Spillover from family to work: the neglected side of the work-family interface. Hum Relat 37(6):425–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678403700601

Davies A (2021) COVID-19 and ICT-supported remote working: opportunities for rural economies. World 2(1):139–152. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-4060/2/1/10

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

de Vaus D (2001) Research design in social research. Sage, California

Demerouti E, Cropanzano R (2010) From thought to action: employee work engagement and job performance. In: Bakker A, Leiter M (ed) Work engagement: a handbook of essential theory and research. Psychology Press, New York, pp. 147–163

DeVellis RF, Thorpe CT (2021) Scale development: theory and applications. Sage, California

Dockery AM, Bawa S (2014) Is working from home good work or bad work? Evidence from Australian employees. Aust. J Labour Econ 17(2):163–190

Dulock HL (1993) Research design: descriptive research. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 10(4):154–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/104345429301000406

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Farooq R, Sultana A (2021) The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work from home and employee productivity. Meas Bus Excell. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBE-12-2020-0173

Feng Z, Savani K (2020) Covid-19 created a gender gap in perceived work productivity and job satisfaction: implications for dual-career parents working from home. Gend Manag 35(7/8):719–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2020-0202

Foy T, Dwyer RJ, Nafarrete R, Hammoud MSS, Rockett P (2019) Managing job performance, social support and work–life conflict to reduce workplace stress. Int J Product Perform Manag 68(6):1018–1041. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2017-0061

Galanti T, Guidetti G, Mazzei E, Zappalà S, Toscano F (2021) Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: the impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J Occup Environ Med 63(7):e426–e432. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002236

Garg N (2015) Organizational role stress in dual-career couples: mediating the relationship between HPWPs, employee engagement and job satisfaction. IUP J Knowl Manag 13:3

Geldenhuys M, Taba K, Venter CM (2014) Meaningful work, work engagement and organisational commitment. J Ind Psychol 40(1):1–10

Graham M, Weale V, Lambert KA, Kinsman N, Stuckey R, Oakman J (2021) Working at home: the impacts of COVID 19 on health, family–work–life conflict, gender, and parental responsibilities. J Occup Environ Med 63(11):938–943. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002337

Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ (1985) Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev 10(1):76–88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

Gutek BA, Nakamura CY, Nieva VF (1981) The interdependence of work and family roles. J Organ Behav 2(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020102

Gutek BA, Searle S, Klepa L (1991) Rational versus gender role explanations for work–family conflict. J Appl Psychol 76(4):560

Hair J, Black W, Babin B, Anderson R (2010) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall, London

Hair J, Black W, Babin B, Anderson R (2019) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall, London

Hair JFJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1995) Multivariate data analysis, 3rd edn. Macmillan, New York

Hanaysha J (2016) Improving employee productivity through work engagement: evidence from higher education sector. Manag Sci Lett 6(1):61–70

Hill EJ, Ferris M, Märtinson V (2003) Does it matter where you work? A comparison of how three work venues (traditional office, virtual office, and home office) influence aspects of work and personal/family life. J Vocat Behav 63(2):220–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00042-3

Hughes D, Galinsky E, Morris A (1992) The effects of job characteristics on marital quality: specifying linking mechanisms. J Marriage Fam 54(1):31–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/353273

Irawanto DW, Novianti KR, Roz K (2021) Work from home: measuring satisfaction between work–life balance and work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 9(3):96, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7099/9/3/96

Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn RP, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA (1964) Organizational stress: studies in role conflict and ambiguity. John Wiley

Karakose T, Yirci R, Papadakis S (2021) Exploring the interrelationship between COVID-19 phobia, work–family conflict, family–work conflict, and life satisfaction among school administrators for advancing sustainable management. Sustainability 13(15):8654, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/15/8654

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kattenbach R, Demerouti E, Nachreiner F (2010) Flexible working times: effects on employees’ exhaustion, work–nonwork conflict and job performance. Career Dev Int 15(3):279–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011053749

Kulik L, Ramon D (2022) The relationship between family–work conflict and spousal aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Community Work Fam 25(2):240–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.1985434

Kuo CC (2021) COVID-19 in Taiwan: economic impacts and lessons learned. Asian Econ Pap 20(2):98–117

Lei MK, Klopack ET (2020) Social and psychological consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: the experiences of Taiwan and Hong Kong. Psychol. Trauma 12(S1):S35

Somekhe B, Lewin C (2005) Research methods in the social sciences. Sage, London, pp. 215–225

Lim VKG, Leng Loo G (2003) Effects of parental job insecurity and parenting behaviors on youth’s self-efficacy and work attitudes. J Vocat Behav 63(1):86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00020-9

Ling Suan C, Mohd Nasurdin A (2014) An empirical investigation into the influence of human resource management practices on work engagement: the case of customer-contact employees in Malaysia. Int J Cult Tour Hosp Res 8(3):345–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-12-2013-0083

Marcoulides GA, Heck RH (1993) Organizational culture and performance: proposing and testing a model. Organ Sci 4(2):209–225

Markos S, Sridevi MS (2010) Employee engagement: the key to improving performance. Int J Bus Manag 5(12):89

Marks SR (1977) Multiple roles and role strain: some notes on human energy, time and commitment. Am Sociol Rev 42(6):921–936. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094577

Mathieu JE, Martineau JW, Tannenbaum SI (1993) Individual and situational influences on the development of self-efficacy: implications for training effectiveness. Pers Psychol 46(1):125–147. 10.1111/j.1744- 6570.1993.tb00870.x

Mestre J (1998) Work at home. CIC 322:80–91

Mihalca L, Ratiu LL, Brendea G, Metz D, Dragan M, Dobre F (2021) Exhaustion while teleworking during COVID-19: a moderated-mediation model of role clarity, self-efficacy, and task interdependence. Oecon Copernic 12(2):269–306

Mohajan HK (2020) Quantitative research: a successful investigation in natural and social sciences. J Econom Dev Environ People 9(4):50–79

Mohsin M, Zahid H (2012) The predictors and performance-related outcomes of bi-directional work–family conflict: an empirical study. Afr J Bus 6:46

Morikawa M (2022) Work-from-home productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Japan. Econ Inq 60(2):508–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.13056

Mukhtar S (2020) Psychological health during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66(5):512–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020925835

Nakrošienė A, Bučiūnienė I, Goštautaitė B (2019) Working from home: characteristics and outcomes of telework. Int J Manpow 40(1):87–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0172

Nardi PM (2018) Doing survey research: a guide to quantitative methods. Routledge

Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R (1996) Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol 81(4):400

Nguyen PV, Nguyen LT, Van Doan KN, Tran HQ (2021) Enhancing emotional engagement through relational contracts, management receptiveness, and employee commitment as a stimulus for job satisfaction and job performance in the public sector. Equilibrium 16(1):203–224

Nunnally JC (1978) An overview of psychological measurement. In: Wolman BB (ed) Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: a handbook. Springer, Boston, pp. 97–146

Chapter Google Scholar

O’Hara C (2014) 5 ways to work from home more effectively. Harv Bus Rev. https://hbr.org/2014/10/5-ways-to-work-from-home-more-effectively

Peng W, Lawler JJ, Kan S (2010) Work-family conflict, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and gender: evidences from Asia. J Leadersh Organ Stud 17(3):298–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051810368546

Perrewé PL, Hochwarter WA, Rossi AM, Wallace A, Maignan I, Castro SL, Van Deusen CA (2002) Are work stress relationships universal? A nine-region examination of role stressors, general self-efficacy, and burnout. J Int Manag 8(2):163–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(02)00052-2

Perry K S (1982) Employers and child care: establishing services through the workplace (No. 23). US Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2004) SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 36(4):717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

Purwanto A, Asbari M, Fahlevi M, Mufid A, Agistiawati E, Cahyono Y, Suryani P (2020) Impact of work from home (WFH) on Indonesian teachers performance during the Covid-19 pandemic: an exploratory study. Int J Adv Sci Eng Inf Technol 29(5):6235–6244

Putri A, Amran A (2021) Employees work–life balance reviewed from work from home aspect during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Inf Manage 1(1):30–34. https://doi.org/10.35870/ijmsit.v1i1.231

Queirós A, Faria D, Almeida F (2017) Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Eur J Educ Stud 3:369–387

Ramos JP, Prasetyo YT (2020) The impact of work-home arrangement on the productivity of employees during COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: a structural equation modelling approach. In: The 6th International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineering, Macau. pp. 135–140

Reina CS, Peterson SJ, Zhang Z (2017) Adverse effects of CEO family-to-work conflict on firm performance. Manage Sci 28(2):228–243. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1114

Ren X, Foster D (2011) Women’s experiences of work and family conflict in a Chinese airline. Asia Pac Bus Rev 17(3):325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602380903462159

Rigotti T, Schyns B, Mohr G (2008) A short version of the occupational self-efficacy scale: structural and construct validity across five countries. J Career Assess 16(2):238–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305763

Rothbard NP, Edwards JR (2003) Investment in work and family roles: a test of identity and utilitarian motives. Personal Psychol Rev 56(3):699–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00755.x

Rupietta K, Beckmann M (2018) Working from home. Schmalenbach Bus Rev 70(1):25–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41464-017-0043-x

Şahin S, Yozgat U (2021) Work–family conflict and job performance: mediating role of work engagement in healthcare employees. J Manag Organ 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.13

Sandström U, Hällsten M (2008) Persistent nepotism in peer-review. Scientometrics 74(2):75–189

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M (2006) The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ Psychol Meas 66(4):701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-romá V, Bakker AB (2002) The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud 3(1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schieman S, Glavin P (2008) Trouble at the border?: gender, flexibility at work, and the work–home interface. Soc Probl 55(4):590–611

Schieman S, McBrier DB, Gundy KV (2003) Home-to-work conflict, work qualities, and emotional distress. Sociol Forum (Randolph, NJ) 18(1):137–164. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022658929709

Schunk DH, Meece JR, Pintrich PR (2012) Motivation in education: theory, research, and applications. Pearson Higher Education, Boston

Shokoohi M, Osooli M, Stranges S (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: what can the west learn from the east. Int J Health Policy Manag 9(10):436–438. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.85

Singh R, Nayak JK (2015) Life stressors and compulsive buying behaviour among adolescents in India. South Asian. South Asian J Bus Res 4(2):251–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJGBR-08-2014-0054

Song Y, Gao J (2020) Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. J Happiness Stud 21(7):2649–2668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00196-6

Stetz TA, Stetz MC, Bliese PD (2006) The importance of self-efficacy in the moderating effects of social support on stressor–strain relationships. Work Stress 20(1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370600624039

Sutarto AP, Wardaningsih S, Putri WH (2021) Work from home: Indonesian employees’ mental well-being and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Workplace Health Manag 14(4):386–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-08-2020-0152

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (1996) Using multivariate statistics. Harper Collins, California

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB (2007) Using multivariate statistics, vol 5. Pearson, Boston

Tabatabaei S, Jashani N, Mataji M, Afsar NA (2013) Enhancing staff health and job performance through emotional intelligence and self-efficacy. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 84:1666–1672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.011

Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (2022) Confirmed Covid-19 cases on 23 of July 2022. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/BfYetzBF23lIlj7dGFgnTw?typeid=158 . Accessed 30 Aug

Takeuchi M, Tsutsui J (2016) Combining Egalitarian Working Lives with Traditional Attitudes: Gender Role Attitudes in Taiwan, Japan, and Korea. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol 25:100–116

Takahashi K, Yokoya R, Higuchi T (2022) Mediation of work engagement towards productive behaviour in remote work environments during pandemic: testing the job demands and resources model in Japan. Asia Pac Bus Rev 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2022.2084848

Tan TW, Tan HL, Chang MN, Lin WS, Chang CM (2021) Effectiveness of epidemic preventive policies and hospital strategies in combating COVID-19 outbreak in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(7):3456, https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/7/3456

Tsang S-S, Liu ZL, Nguyen TVT (2023) Work-from-home intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: a perspective integrating inclusive leadership and protection motivation theory. Int J Manpow. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-11-2022-0541

van Meel J (2011) The origins of new ways of working. Facilities 29(9–10):357–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/02632771111146297

Vyas L, Butakhieo N (2021) The impact of working from home during COVID-19 on work and life domains: an exploratory study on Hong Kong. Policy Des Pract 4(1):59–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1863560

Waizenegger L, McKenna B, Cai W, Bendz T (2020) An affordance perspective of team collaboration and enforced working from home during COVID-19. Eur J Inf Syst 29(4):429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1800417