- Brain Development

- Childhood & Adolescence

- Diet & Lifestyle

- Emotions, Stress & Anxiety

- Learning & Memory

- Thinking & Awareness

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Childhood Disorders

- Immune System Disorders

- Mental Health

- Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Infectious Disease

- Neurological Disorders A-Z

- Body Systems

- Cells & Circuits

- Genes & Molecules

- The Arts & the Brain

- Law, Economics & Ethics

- Neuroscience in the News

- Supporting Research

- Tech & the Brain

- Animals in Research

- BRAIN Initiative

- Meet the Researcher

- Neuro-technologies

- Tools & Techniques

- Core Concepts

- For Educators

- Ask an Expert

- The Brain Facts Book

Is photographic memory real? If so, how does it work?

- Published 17 Apr 2013

- Reviewed 17 Apr 2013

- Author Larry Squire

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Photographic memory is a term often used to describe a person who seems able to recall visual information in great detail. Just as a photograph freezes a moment in time, the implication for people thought to have photographic memory is that they can take mental snapshots and then recall these snapshots without error. However, photographic memory does not exist in this sense.

It is easy to demonstrate this by asking people who think they have photographic memory to read two or three lines of text and then report the text in reverse order. If memory worked like a photograph, these people would be able to rapidly reproduce the text in reverse order by "reading" the photo. However, people cannot do this.

Memory is more like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle than a photograph . To recollect a past event, we piece together various remembered elements and typically forget parts of what happened (the color of the wall, the picture in the background, the exact words that were said). Passing over details helps us to form general concepts. We are good at remembering the gist of what happened and less good at remembering (photographically) all the elements of a past scene. This is advantageous because what is important for memory is the meaning of what was presented, not the exact details present at any given time.

Of course, people vary in their ability to remember the past. How well we remember things depends largely on how well we pay attention when material is presented. Additionally, the extent to which we replay the material in our minds and relate it to what we already know affects our ability to remember.

Some people with excellent memory use elaborate techniques to help them remember. Others are able to effortlessly recall vast amounts of autobiographical information spanning most of the lifetime. Scientists are learning more about memory by studying these people, as well as people who have very poor memory as the result of neurological injury or disease .

About the Author

Larry Squire

Larry Squire is a professor of psychiatry, neurosciences, and psychology at the University of California, San Diego and research career scientist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System. His research explores the organization and neurological foundations of memory.

BrainFacts.org welcomes all your brain-related questions.

Every month, we choose one reader question and get an answer from a top neuroscientist. Always been curious about something?

Disclaimer: BrainFacts.org provides information about the field's understanding of causes, symptoms, and outcomes of brain disorders. It is not intended to give specific medical or other advice to patients. Visitors interested in medical advice should consult with a physician.

Question sent. Thank you.

There was an error sending your feedback. Please try again later.

Ask An Expert

Ask a neuroscientist your questions about the brain.

Submit a Question

Brain Awareness Week

A worldwide celebration of the brain that brings together scientists, families, schools, and communities during the third week in March.

Join the Campaign

Find a Neuroscientist

Engage local scientists to educate your community about the brain.

SUPPORTING PARTNERS

- Accessibility Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Manage Cookies

Some pages on this website provide links that require Adobe Reader to view.

January 1, 2013

Does Photographic Memory Exist?

Sean Gladwell Getty Images

I developed what appears to be a photographic memory when I was 16 years old. Does this kind of memory truly exist, and, if so, how did I develop it?

— Peter Gordon , Scotland

Barry Gordon , a professor of neurology and cognitive science at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (and no relation), offers an explanation:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The intuitive notion of a “photographic” memory is that it is just like a photograph: you can retrieve it from your memory at will and examine it in detail, zooming in on different parts. But a true photographic memory in this sense has never been proved to exist.

Most of us do have a kind of photographic memory, in that most people's memory for visual material is much better and more detailed than our recall of most other kinds of material. For instance, most of us remember a face much more easily than the name associated with that face. But this isn't really a photographic memory; it just shows us the normal difference between types of memory.

Even visual memories that seem to approach the photographic ideal are far from truly photographic. These memories seem to result from a combination of innate abilities, combined with zealous study and familiarity with the material, such as the Bible or fine art.

Sorry to disappoint further, but even an amazing memory in one domain, such as vision, is not a guarantee of great memory across the board. That must be rare, if it occurs at all. A winner of the memory Olympics, for instance, still had to keep sticky notes on the refrigerator to remember what she had to do during the day.

So how does an exceptional, perhaps photographic, memory come to be? It depends on a slew of factors, including our genetics, brain development and experiences. It is difficult to disentangle memory abilities that appear early from those cultivated through interest and training. Most people who have exhibited truly extraordinary memories in some domain have seemed to possess them all their lives and honed them further through practice.

Various parts of the brain mature at different times, and adolescence is a major time for such changes. It's possible Mr. Gordon's ability took a big jump around his 16th birthday, but it's also possible he noticed it only then. Mr. Gordon might want to have formal testing, to see just how good his memory is and in what areas. Then we can debate the nature-nurture question from harder evidence.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Eidetic Memory: The Reality Behind the 'Photographic' Mind

Is perfect recall a myth?

Gary Yeowell/DigitalVision/Getty Images

The Science Behind Eidetic Memory

- Eidetic Memory vs. Regular Memory

Is Eidetic Memory Real?

Examples of people said to have eidetic memory.

- Techniques to Improve Memory Recall

The ability to recall memories can differ from one person to another. Two people who witnessed the same event can have totally different memories of it. But what if one of the people allegedly has an eidetic memory and can accurately remember exactly what happened in complete detail? Do these people actually exist?

Eidetic memory, often (inaccurately) referred to as a photograph memory, Dr. Kimberly Johnson-Hatchett , MD, board-certified neurologist, public speaker, and author of Retrospective Calling explains that eidetic memory is a rare form of memory usually seen in children where they are exposed to an image for 30 seconds or less and are able to recall this object in great detail, but only for a brief period of time.

Someone with a photographic memory is said to be able to recall images after a long time. It’s permanently stored in their minds without any changes to details similar to a camera taking a photo. Some people claim to have a photographic memory but there is no conclusive evidence that shows it actually exists.

Eidetic memory is similar to photographic memory but the recall lasts much shorter.

It’s not really understood how eidetic memory works. However, it might have to do with synesthesia which is the neurological condition where a person can experience one sense through another. For instance, a person may see colors when they hear certain sounds.

An exploratory study looked at the association between eidetic memory and synesthesia. Multiple tests that assessed eidetic imagery, color-hearing and color-mood synesthesia were performed on ten participants with possible eidetic memory and/or synesthetic ability. The results showed a significant correlation between synesthesia and eidetic memory, however, more research is needed.

Eidetic Memory vs. Regular Memory

Imagine you are shown a photo of a downtown scene. Once the photo is taken away, you are asked to talk about what was in the image. Most of us can recall some level detail including colors, shapes, prominent objects, and people in the image. This is your short-term memory working. These are memories you are currently thinking about and paying attention to. You can typically remember short-term memories for about 20 to 30 seconds.

However, someone with eidetic memory has a much greater capacity. In the same exercise, they can remember accurate details including how many windows in the buildings, license plate numbers, street names, types and number of people, and exactly they were wearing down to the number of buttons.

Detective shows love to make use of protagonists with this kind of perfect recall.

Eidetic memory is mostly seen among children and very rarely among adults. Dr. Maya Shetreat , MD, pediatric neurologist, herbalist and author of The Dirt Cure explained that the phenomenon is found far less commonly as we age, likely because adults rely heavily on language and less on visual-spatial memory skills.

One study looked for evidence for the uniqueness of this type of memory in schoolchildren and showed that eidetic imagery did not correlate with superior intellect. Students were classified as eidetic using self-report criteria including objective and subjective measures. The results showed the eidetic subjects performed better on an ‘accuracy of report’ test and a superimposition task; however, the differences weren’t great enough to support evidence for the uniqueness of eidetic imagery.

Additional tests were performed to look at the effect of stimulus manipulations on visual retention . The results showed a lack of significant differences in capacity for visual memory between eidetic subjects and a control group. It concluded that the storage capacity is not a factor in the difference between eidetic imagery and visual memory.

Although there has not been any proof that eidetic memory exists in adults, there are prominent people who have claimed to possess this ability. Some of these include the following:

- Nikola Tesla, Serbina-American inventor

- Sergei Rachmaninoff, Russian composer

- C. S. Lewis, author and literary scholar

- Leonardo da Vinci, Italian polymath

- Theodore Roosevelt, 26th US President

- Guillermo Del Toro, filmmaker

Techniques to Improve Memory Recall

Whether or not you have eidetic memory—or even a good memory—your memory can be trained just like a muscle. Here are some ways to strengthen and condition your memory recall:

Improve Your Sleep

Dr. Johnson-Hatchett explained that sleep is where memory consolidation occurs; depriving someone of needed sleep or denying them these sleep cycles can cause cognitive decline and poor memory recall and concentration.

Therefore, one of the most basic things we can do to improve our memory recall is to improve our sleep, specifically our slow wave and REM sleep .

Exercise Your Brain

If you don’t use it, you lose it. Dr. Johnson-Hatchett advised that brain exercises such as activities and games that stimulate and are geared towards memorization have been shown in a randomized study to improve cognitive performance including recall memory.

Ask Yourself To Remember

It’s been shown that the act of predicting whether you would remember specific important tasks can increase your likelihood of recalling these tasks.

So the next time you think of something you need to remember, ask yourself, “Will I remember it tomorrow?”

Test Yourself Regularly

It’s been shown that testing yourself regularly can help improve your memory recall and information retention.

“For instance, learning a topic, then asking yourself questions about that can improve your retention of that material faster and better than just re-reading or re-listening to that same information,” says Dr. Johnson-Hatchett.

Continue To Learn New Things

Strengthening memory—eidetic or otherwise—in adulthood takes practice and it requires you to consistently get outside your comfort zone.

Dr. Shetreat encourages everyone to continually learn new things. This can be learning an instrument, a martial art, a sport, or doing puzzles and reading books. Exercise and spending regular time immersed in nature are also memory enhancers.

“[Continually learning new things] will always cultivate better memory in general and enhance brain plasticity (new connections in the brain) no matter what your age,” shares Dr. Shetreat.

The ability to recall experiences, images and events allows us to make sense of our present and future. A strong memory can help us become lifelong learners. From brain exercises, and puzzles to better sleep, there are many techniques we can try to improve our memory and in turn, help us live long and healthy lives.

Cutts NE, Moseley N. Notes on photographic memory. The Journal of Psychology. 1969;71(1):3–15.

Glicksohn J, Salinger O, Roychman A. An exploratory study of syncretic experience: eidetics, synaesthesia and absorption. Perception . 1992;21(5):637–642.

Miller S, Peacock R. Evidence for the uniqueness of eidetic imagery. Percept Mot Skills. 1982;55(3 Pt 2):1219–1233.

Hardy JL, Nelson RA, Thomason ME, et al. Enhancing cognitive abilities with comprehensive training: a large, online, randomized, active-controlled trial. PLoS One . 2015;10(9):e013446

Meier B, von Wartburg P, Matter S, Rothen N, Reber R. Performance predictions improve prospective memory and influence retrieval experience. Can J Exp Psychol. 2011;65(1):12–18.

Halamish V, Bjork RA. When does testing enhance retention? A distribution-based interpretation of retrieval as a memory modifier. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn . 2011;37(4):801–812.

By Katharine Chan, MSc, BSc, PMP Katharine is the author of three books (How To Deal With Asian Parents, A Brutally Honest Dating Guide and A Straight Up Guide to a Happy and Healthy Marriage) and the creator of 60 Feelings To Feel: A Journal To Identify Your Emotions. She has over 15 years of experience working in British Columbia's healthcare system.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 05 August 2019

The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery

- Joel Pearson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3704-5037 1

Nature Reviews Neuroscience volume 20 , pages 624–634 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

36k Accesses

307 Citations

217 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Object vision

- Sensory systems

- Working memory

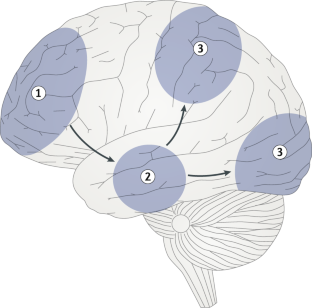

Mental imagery can be advantageous, unnecessary and even clinically disruptive. With methodological constraints now overcome, research has shown that visual imagery involves a network of brain areas from the frontal cortex to sensory areas, overlapping with the default mode network, and can function much like a weak version of afferent perception. Imagery vividness and strength range from completely absent (aphantasia) to photo-like (hyperphantasia). Both the anatomy and function of the primary visual cortex are related to visual imagery. The use of imagery as a tool has been linked to many compound cognitive processes and imagery plays both symptomatic and mechanistic roles in neurological and mental disorders and treatments.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

176,64 € per year

only 14,72 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Early-stage visual perception impairment in schizophrenia, bottom-up and back again

A cognitive profile of multi-sensory imagery, memory and dreaming in aphantasia

Between-subject variability in the influence of mental imagery on conscious perception

Zeman, A., Dewar, M. & Della Sala, S. Lives without imagery — congenital aphantasia. Cortex 73 , 378–380 (2015). This article documents and coins the term aphantasia, described as the complete lack of visual imagery ability .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pearson, J. & Westbrook, F. Phantom perception: voluntary and involuntary non-retinal vision. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19 , 278–284 (2015). This opinion paper proposes a unifying framework for both voluntary and involuntary imagery .

Pearson, J., Naselaris, T., Holmes, E. A. & Kosslyn, S. M. Mental imagery: functional mechanisms and clinical applications. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19 , 590–602 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Egeth, H. E. & Yantis, S. Visual attention: control, representation, and time course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 48 , 269–297 (1997).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dijkstra, N., Zeidman, P., Ondobaka, S., Gerven, M. A. J. & Friston, K. Distinct top-down and bottom-up brain connectivity during visual perception and imagery. Sci. Rep. 7 , 5677 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dentico, D. et al. Reversal of cortical information flow during visual imagery as compared to visual perception. Neuroimage 100 , 237–243 (2014).

Schlegel, A. et al. Network structure and dynamics of the mental workspace. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 16277–16282 (2013).

Ranganath, C. & D’Esposito, M. Directing the mind’s eye: prefrontal, inferior and medial temporal mechanisms for visual working memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15 , 175–182 (2005).

Yomogida, Y. Mental visual synthesis is originated in the fronto-temporal network of the left hemisphere. Cereb. Cortex 14 , 1376–1383 (2004).

Ishai, A., Ungerleider, L. G. & Haxby, J. V. Distributed neural systems for the generation of visual images. Neuron 28 , 979–990 (2000).

Goebel, R., Khorram-Sefat, D., Muckli, L., Hacker, H. & Singer, W. The constructive nature of vision: direct evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of apparent motion and motion imagery. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10 , 1563–1573 (1998).

Mellet, E. et al. Functional anatomy of spatial mental imagery generated from verbal instructions. J. Neurosci. 16 , 6504–6512 (1996).

O’Craven, K. M. & Kanwisher, N. Mental imagery of faces and places activates corresponding stimulus- specific brain regions. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12 , 1013–1023 (2000).

Kosslyn, S. M., Ganis, G. & Thompson, W. L. Neural foundations of imagery. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 , 635–642 (2001).

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D. & Maguire, E. A. Using imagination to understand the neural basis of episodic memory. J. Neurosci. 27 , 14365–14374 (2007).

Bird, C. M., Capponi, C., King, J. A., Doeller, C. F. & Burgess, N. Establishing the boundaries: the hippocampal contribution to imagining scenes. J. Neurosci. 30 , 11688–11695 (2010).

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D. & Maguire, E. A. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 1726–1731 (2007).

Kreiman, G., Koch, C. & Fried, I. Imagery neurons in the human brain. Nature 408 , 357–361 (2000).

Maguire, E. A., Vargha-Khadem, F. & Hassabis, D. Imagining fictitious and future experiences: evidence from developmental amnesia. Neuropsychologia 48 , 3187–3192 (2010).

Kim, S. et al. Sparing of spatial mental imagery in patients with hippocampal lesions. Learn. Mem. 20 , 657–663 (2013).

Pearson, J. & Kosslyn, S. M. The heterogeneity of mental representation: ending the imagery debate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 10089–10092 (2015). This paper proposes an end to the ‘imagery debate’ based on the discussed evidence that imagery can be represented in the brain in a depictive manner .

D’Esposito, M. et al. A functional MRI study of mental image generation. Neuropsychologia 35 , 725–730 (1997).

Knauff, M., Kassubek, J., Mulack, T. & Greenlee, M. W. Cortical activation evoked by visual mental imagery as measured by fMRI. Neuroreport 11 , 3957–3962 (2000).

Trojano, L. et al. Matching two imagined clocks: the functional anatomy of spatial analysis in the absence of visual stimulation. Cereb. Cortex 10 , 473–481 (2000).

Wheeler, M. E., Petersen, S. E. & Buckner, R. L. Memory’s echo: vivid remembering reactivates sensory-specific cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97 , 11125 (2000).

Formisano, E. et al. Tracking the mind’s image in the brain I: time-resolved fMRI during visuospatial mental imagery. Neuron 35 , 185–194 (2002).

Sack, A. T. et al. Tracking the mind’s image in the brain II: transcranial magnetic stimulation reveals parietal asymmetry in visuospatial imagery. Neuron 35 , 195–204 (2002).

Le Bihan, D. et al. Activation of human primary visual cortex during visual recall: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90 , 11802–11805 (1993).

Sabbah, P. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5T during sensorimotor and cognitive task. Eur. Neurol. 35 , 131–136 (1995).

Chen, W. et al. Human primary visual cortex and lateral geniculate nucleus activation during visual imagery. Neuroreport 9 , 3669–3674 (1998).

Ishai, A. Visual imagery of famous faces: effects of memory and attention revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage 17 , 1729–1741 (2002).

Ganis, G., Thompson, W. L. & Kosslyn, S. M. Brain areas underlying visual mental imagery and visual perception: an fMRI study. Cogn. Brain Res. 20 , 226–241 (2004).

Article Google Scholar

Klein, I., Paradis, A. L., Poline, J. B., Kossly, S. M. & Le Bihan, D. Transient activity in the human calcarine cortex during visual-mental imagery: an event-related fMRI study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12 (Suppl. 2), 15–23 (2000).

Lambert, S., Sampaio, E., Scheiber, C. & Mauss, Y. Neural substrates of animal mental imagery: calcarine sulcus and dorsal pathway involvement — an fMRI study. Brain Res. 924 , 176–183 (2002).

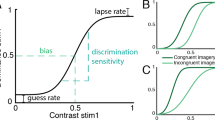

Cui, X., Jeter, C. B., Yang, D., Montague, P. R. & Eagleman, D. M. Vividness of mental imagery: individual variability can be measured objectively. Vision Res. 47 , 474–478 (2007).

Amedi, A., Malach, R. & Pascual-Leone, A. Negative BOLD differentiates visual imagery and perception. Neuron 48 , 859–872 (2005).

Reddy, L., Tsuchiya, N. & Serre, T. Reading the mind’s eye: decoding category information during mental imagery. Neuroimage 50 , 818–825 (2010).

Dijkstra, N., Bosch, S. E. & van Gerven, M. A. J. Vividness of visual imagery depends on the neural overlap with perception in visual areas. J. Neurosci. 37 , 1367–1373 (2017).

Kosslyn, S. M. & Thompson, W. L. When is early visual cortex activated during visual mental imagery? Psychol. Bull. 129 , 723–746 (2003).

Albers, A. M., Kok, P., Toni, I., Dijkerman, H. C. & de Lange, F. P. Shared representations for working memory and mental imagery in early visual cortex. Curr. Biol. 23 , 1427–1431 (2013). This paper shows that both imagery and visual working memory can be decoded in the brain based on training on either, showing evidence of a common brain representation .

Koenig-Robert, R. & Pearson, J. Decoding the contents and strength of imagery before volitional engagement. Sci. Rep. 9 , 3504 (2019). This paper shows that the content and vividness of a mental image can be decoded in the brain up to 11 seconds before an individual decides which pattern to imagine .

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Naselaris, T., Olman, C. A., Stansbury, D. E., Ugurbil, K. & Gallant, J. L. A voxel-wise encoding model for early visual areas decodes mental images of remembered scenes. Neuroimage 105 , 215–228 (2015). This study shows that mental imagery content can be decoded in the early visual cortex when the decoding model is based on depictive perceptual features .

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 9673–9678 (2005).

Smith, S. M. et al. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 13040–13045 (2009).

Østby, Y. et al. Mental time travel and default-mode network functional connectivity in the developing brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109 , 16800–16804 (2012).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Sepulcre, J., Poulin, R. & Buckner, R. L. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron 65 , 550–562 (2010).

Hassabis, D. & Maguire, E. A. Deconstructing episodic memory with construction. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11 , 299–306 (2007).

Gerlach, K. D., Spreng, R. N., Gilmore, A. W. & Schacter, D. L. Solving future problems: default network and executive activity associated with goal-directed mental simulations. Neuroimage 55 , 1816–1824 (2011).

Levine, D. N., Warach, J. & Farah, M. Two visual systems in mental imagery. Neurology 35 , 1010 (1985).

Keogh, R. & Pearson, J. The blind mind: no sensory visual imagery in aphantasia. Cortex 105 , 53–60 (2017).

Sakai, K. & Miyashita, Y. Neural organization for the long-term memory of paired associates. Nature 354 , 152–155 (1991).

Messinger, A., Squire, L. R., Zola, S. M. & Albright, T. D. Neuronal representations of stimulus associations develop in the temporal lobe during learning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98 , 12239–12244 (2001).

Schlack, A. & Albright, T. D. Remembering visual motion: neural correlates of associative plasticity and motion recall in cortical area MT. Neuron 53 , 881–890 (2007).

Bannert, M. M. & Bartels, A. Decoding the yellow of a gray banana. Curr. Biol. 23 , 2268–2272 (2013).

Hansen, T., Olkkonen, M., Walter, S. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Memory modulates color appearance. Nat. Neurosci. 9 , 1367–1368 (2006).

Meng, M., Remus, D. A. & Tong, F. Filling-in of visual phantoms in the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 8 , 1248–1254 (2005).

Sasaki, Y. & Watanabe, T. The primary visual cortex fills in color. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101 , 18251–18256 (2004).

Kok, P., Failing, M. F. & de Lange, F. P. Prior expectations evoke stimulus templates in the primary visual cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26 , 1546–1554 (2014).

Bergmann, J., Genc, E., Kohler, A., Singer, W. & Pearson, J. Smaller primary visual cortex is associated with stronger, but less precise mental imagery. Cereb. Cortex 26 , 3838–3850 (2016). This study shows that stronger but less precise imagery is associated with a smaller primary and secondary visual cortex .

Stensaas, S. S., Eddington, D. K. & Dobelle, W. H. The topography and variability of the primary visual cortex in man. J. Neurosurg. 40 , 747–755 (1974).

Song, C., Schwarzkopf, D. S. & Rees, G. Variability in visual cortex size reflects tradeoff between local orientation sensitivity and global orientation modulation. Nat. Commun. 4 , 1–10 (2013).

Google Scholar

Dorph-Petersen, K.-A., Pierri, J. N., Wu, Q., Sampson, A. R. & Lewis, D. A. Primary visual cortex volume and total neuron number are reduced in schizophrenia. J. Comp. Neurol. 501 , 290–301 (2007).

Sack, A. T., van de Ven, V. G., Etschenberg, S., Schatz, D. & Linden, D. E. J. Enhanced vividness of mental imagery as a trait marker of schizophrenia? Schizophr. Bull. 31 , 97–104 (2005).

Maróthi, R. & Kéri, S. Enhanced mental imagery and intact perceptual organization in schizotypal personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 259 , 433–438 (2018).

Morina, N., Leibold, E. & Ehring, T. Vividness of general mental imagery is associated with the occurrence of intrusive memories. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 44 , 221–226 (2013).

Chao, L. L., Lenoci, M. & Neylan, T. C. Effects of post-traumatic stress disorder on occipital lobe function and structure. Neuroreport 23 , 412–419 (2012).

Tavanti, M. et al. Evidence of diffuse damage in frontal and occipital cortex in the brain of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurol. Sci. 33 , 59–68 (2011).

Kavanagh, D. J., Andrade, J. & May, J. Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: the elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychol. Rev. 112 , 446–467 (2005).

Ersche, K. D. et al. Abnormal brain structure implicated in stimulant drug addiction. Science 335 , 601–604 (2012).

Song, C., Schwarzkopf, D. S., Kanai, R. & Rees, G. Reciprocal anatomical relationship between primary sensory and prefrontal cortices in the human brain. J. Neurosci. 31 , 9472–9480 (2011).

Panizzon, M. S. et al. Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb. Cortex 19 , 2728–2735 (2009).

Winkler, A. M. et al. Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage 53 , 1135–1146 (2010).

Bakken, T. E. et al. Association of common genetic variants in GPCPD1 with scaling of visual cortical surface area in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109 , 3985–3990 (2012).

Pearson, J., Rademaker, R. L. & Tong, F. Evaluating the mind’s eye: the metacognition of visual imagery. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 1535–1542 (2011).

Rademaker, R. L. & Pearson, J. Training visual imagery: improvements of metacognition, but not imagery strength. Front. Psychol. 3 , 224 (2012).

Pearson, J. New directions in mental-imagery research: the binocular-rivalry technique and decoding fMRI patterns. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 178–183 (2014).

Keogh, R., Bergmann, J. & Pearson, J. Cortical excitability controls the strength of mental imagery. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/093690v1 (2016).

Terhune, D. B., Tai, S., Cowey, A., Popescu, T. & Kadosh, R. C. Enhanced cortical excitability in grapheme-color synesthesia and its modulation. Curr. Biol. 21 , 2006–2009 (2011).

Chiou, R., Rich, A. N., Rogers, S. & Pearson, J. Exploring the functional nature of synaesthetic colour: dissociations from colour perception and imagery. Cognition 177 , 107–121 (2018).

Arieli, A., Sterkin, A., Grinvald, A. & Aertsen, A. Dynamics of ongoing activity: explanation of the large variability in evoked cortical responses. Science 273 , 1868–1871 (1996).

Wassell, J., Rogers, S. L., Felmingam, K. L., Bryant, R. A. & Pearson, J. Biological psychology. Biol. Psychol. 107 , 61–68 (2015).

Kraehenmann, R. et al. LSD increases primary process thinking via serotonin 2A receptor activation. Front. Pharmacol. 8 , 418–419 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Pearson, J., Clifford, C. W. G. & Tong, F. The functional impact of mental imagery on conscious perception. Curr. Biol. 18 , 982–986 (2008). This study shows that the content of visual imagery can bias or prime subsequent binocular rivalry; this paper was the basis for using binocular rivalry as a measurement tool for imagery .

Ishai, A. & Sagi, D. Common mechanisms of visual imagery and perception. Science 268 , 1772–1774 (1995).

Tartaglia, E. M., Bamert, L., Mast, F. W. & Herzog, M. H. Human perceptual learning by mental imagery. Curr. Biol. 19 , 2081–2085 (2009). This study shows that training with a purely imaged visual stimulus transfers to improve performance in perceptual tasks .

Lewis, D. E., O’Reilly, M. J. & Khuu, S. K. Conditioning the mind’s eye associative learning with voluntary mental imagery. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 1 , 390–400 (2013).

Laeng, B. & Sulutvedt, U. The eye pupil adjusts to imaginary light. Psychol. Sci. 25 , 188–197 (2014).

Brascamp, J. W., Knapen, T. H. J., Kanai, R., van Ee, R. & van den Berg, A. V. Flash suppression and flash facilitation in binocular rivalry. J. Vis. 7 , 12 (2007).

Tanaka, Y. & Sagi, D. A perceptual memory for low-contrast visual signals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95 , 12729–12733 (1998).

Chang, S., Lewis, D. E. & Pearson, J. The functional effects of color perception and color imagery. J. Vis. 13 , 4 (2013).

Slotnick, S. D., Thompson, W. L. & Kosslyn, S. M. Visual mental imagery induces retinotopically organized activation of early visual areas. Cereb. Cortex 15 , 1570–1583 (2005).

Thirion, B. et al. Inverse retinotopy: inferring the visual content of images from brain activation patterns. Neuroimage 33 , 1104–1116 (2006).

Horikawa, T. & Kamitani, Y. Generic decoding of seen and imagined objects using hierarchical visual features. Nat. Commun. 8 , 15037 (2017).

Keogh, R. & Pearson, J. Mental imagery and visual working memory. PLOS ONE 6 , e29221 (2011).

Keogh, R. & Pearson, J. The sensory strength of voluntary visual imagery predicts visual working memory capacity. J. Vis. 14 , 7 (2014).

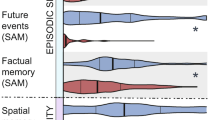

Aydin, C. The differential contributions of visual imagery constructs on autobiographical thinking. Memory 26 , 189–200 (2017).

Schacter, D. L. et al. The future of memory: remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron 76 , 677–694 (2012).

Tong, F. Imagery and visual working memory: one and the same? Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 , 489–490 (2013).

Berger, G. H. & Gaunitz, S. C. Self-rated imagery and encoding strategies in visual memory. Br. J. Psychol. 70 , 21–24 (1979).

Harrison, S. A. & Tong, F. Decoding reveals the contents of visual working memory in early visual areas. Nature 458 , 632–635 (2009).

Borst, G., Ganis, G., Thompson, W. L. & Kosslyn, S. M. Representations in mental imagery and working memory: evidence from different types of visual masks. Mem. Cognit. 40 , 204–217 (2011).

Kang, M.-S., Hong, S. W., Blake, R. & Woodman, G. F. Visual working memory contaminates perception. Psychon Bull. Rev. 18 , 860–869 (2011).

Keogh, R. & Pearson, J. The perceptual and phenomenal capacity of mental imagery. Cognition 162 , 124–132 (2017). This study shows a new method to measure the capacity function of visual imagery and shows that it is quite limited .

Luck, S. J. & Vogel, E. K. Visual working memory capacity: from psychophysics and neurobiology to individual differences. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 , 391–400 (2013).

Pearson, J. & Keogh, R. Redefining visual working memory: a cognitive-strategy, brain-region approach. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28 , 266–273 (2019).

Greenberg, D. L. & Knowlton, B. J. The role of visual imagery in autobiographical memory. Mem. Cognit. 42 , 922–934 (2014).

Sheldon, S., Amaral, R. & Levine, B. Individual differences in visual imagery determine how event information is remembered. Memory 25 , 360–369 (2017).

D’Argembeau, A. & Van der Linden, M. Individual differences in the phenomenology of mental time travel: the effect of vivid visual imagery and emotion regulation strategies. Conscious Cogn. 15 , 342–350 (2006).

Vannucci, M., Pelagatti, C., Chiorri, C. & Mazzoni, G. Visual object imagery and autobiographical memory: object Imagers are better at remembering their personal past. Memory 24 , 455–470 (2015).

Galton, F. Statistics of mental imagery. Mind 5 , 301–318 (1880). This paper was the first formal empirical paper investing imagery vividness, including the first report of what is now called aphantasia .

Holmes, E. A. & Mathews, A. Mental imagery in emotion and emotional disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30 , 349–362 (2010).

Hackmann, A., Bennett-Levy, J. & Holmes, E. A. Oxford Guide to Imagery in Cognitive Therapy (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Blackwell, S. E. et al. Positive imagery-based cognitive bias modification as a web-based treatment tool for depressed adults: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 3 , 91–111 (2015).

Crane, C., Shah, D., Barnhofer, T. & Holmes, E. A. Suicidal imagery in a previously depressed community sample. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 19 , 57–69 (2011).

Hales, S. A., Deeprose, C., Goodwin, G. M. & Holmes, E. A. Cognitions in bipolar affective disorder and unipolar depression: imagining suicide. Bipolar Disord. 13 , 651–661 (2011).

Holmes, E. A. et al. Mood stability versus mood instability in bipolar disorder: a possible role for emotional mental imagery. Behav. Res. Ther. 49 , 707–713 (2011).

Tiggemann, M. & Kemps, E. The phenomenology of food cravings: the role of mental imagery. Appetite 45 , 305–313 (2005).

Connor, J. P. et al. Addictive behaviors. Addict. Behav. 39 , 721–724 (2014).

May, J., Andrade, J., Panabokke, N. & Kavanagh, D. Visuospatial tasks suppress craving for cigarettes. Behav. Res. Ther. 48 , 476–485 (2010).

Michael, T., Ehlers, A., Halligan, S. L. & Clark, D. M. Unwanted memories of assault: what intrusion characteristics are associated with PTSD? Behav. Res. Ther. 43 , 613–628 (2005).

Holmes, E. A., James, E. L., Kilford, E. J. & Deeprose, C. Key steps in developing a cognitive vaccine against traumatic flashbacks: visuospatial tetris versus verbal pub quiz. PLOS ONE 5 , e13706 (2010).

Shine, J. M. et al. Imagine that: elevated sensory strength of mental imagery in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and visual hallucinations. Proc. R. Soc. B 282 , 20142047 (2014).

Foa, E. B., Steketee, G., Turner, R. M. & Fischer, S. C. Effects of imaginal exposure to feared disasters in obsessive-compulsive checkers. Behav. Res. Ther. 18 , 449–455 (1980).

Hunt, M. & Fenton, M. Imagery rescripting versus in vivo exposure in the treatment of snake fear. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 38 , 329–344 (2007).

Holmes, E. A. & Mathews, A. Mental imagery and emotion: a special relationship? Emotion 5 , 489–497 (2005).

Zeman, A. Z. J. et al. Loss of imagery phenomenology with intact visuo-spatial task performance: a case of ‘blind imagination’. Neuropsychologia 48 , 145–155 (2010).

Ungerleider, L. G. & Haxby, J. V. ‘What’ and ‘where’ in the human brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 4 , 157–165 (1994).

Jacobs, C., Schwarzkopf, D. S. & Silvanto, J. Visual working memory performance in aphantasia. Cortex 105 , 61–73 (2017).

Gray, C. R. & Gummerman, K. The enigmatic eidetic image: a critical examination of methods, data, and theories. Psychol. Bull. 82 , 383–407 (1975).

Stromeyer, C. F. & Psotka, J. The detailed texture of eidetic images. Nature 225 , 346–349 (1970).

Haber, R. N. Twenty years of haunting eidetic imagery: where’s the ghost? Behav. Brain Sci. 2 , 616–617 (1979).

Allport, G. W. Eidetic imagery. Br. J. Psychol. 15 , 99–120 (1924).

Kwok, E. L., Leys, G., Koenig-Robert, R. & Pearson, J. Measuring thought-control failure: sensory mechanisms and individual differences. Psychol. Sci. 57 , 811–821 (2019). This study shows that, even when people think they have successfully suppressed a mental image, it is still actually there and biases subsequent perception (a possible candidate for unconscious imagery) .

Kosslyn, S. M. Image and Mind (Harvard Univ. Press, 1980).

Kosslyn, S. M. Mental images and the brain. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 22 , 333–347 (2005).

Pylyshyn, Z. W. What the mind’s eye tells the mind’s brain: a critique of mental imagery. Psychol. Bull. 80 , 1–24 (1973).

Pylyshyn, Z. Return of the mental image: are there really pictures in the brain? Trends Cogn. Sci. 7 , 113–118 (2003). This review provides an updated summary of the imagery debate .

Chang, S. & Pearson, J. The functional effects of prior motion imagery and motion perception. Cortex 105 , 83–96 (2017).

Stokes, M., Thompson, R., Cusack, R. & Duncan, J. Top-down activation of shape-specific population codes in visual cortex during mental imagery. J. Neurosci. 29 , 1565–1572 (2009).

Amit, E. & Greene, J. D. You see, the ends don’t justify the means: visual imagery and moral judgment. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 861–868 (2012).

Dobson, M. & Markham, R. Imagery ability and source monitoring: implications for eyewitness memory. Br. J. Psychol. 84 , 111–118 (1993).

Gonsalves, B. et al. Neural evidence that vivid imagining can lead to false remembering. Psychol. Sci. 15 , 655–660 (2004).

Bird, C. M., Bisby, J. A. & Burgess, N. The hippocampus and spatial constraints on mental imagery. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6 , 142 (2012).

Jones, L. & Stuth, G. The uses of mental imagery in athletics: an overview. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 6 , 101–115 (1997).

Dils, A. T. & Boroditsky, L. Visual motion aftereffect from understanding motion language. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107 , 16396–16400 (2010).

Christian, B. M., Miles, L. K., Parkinson, C. & Macrae, C. N. Visual perspective and the characteristics of mind wandering. Front. Psychol. 4 , 699 (2013).

Palmiero, M., Cardi, V. & Belardinelli, M. O. The role of vividness of visual mental imagery on different dimensions of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 23 , 372–375 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author thanks R. Keogh, R. Koenig-Robert and A. Dawes for helpful feedback and discussion on this paper. This paper, and some of the work discussed in it, was supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council grants APP1024800, APP1046198 and APP1085404, a Career Development Fellowship APP1049596 and an Australian Research Council discovery project grant DP140101560.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Joel Pearson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joel Pearson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Reviews Neuroscience thanks D. Kavanagh, J. Hohwy and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The reverse direction of neural information flow, for example, from the top-down, as opposed to the bottom-up.

Magnetic resonance imaging and functional magnetic resonance imaging decoding methods that are constrained by or based on individual voxel responses to perception, which are then used to decode imagery.

Transformations in a spatial domain.

The conscious sense or feeling of something, different from detection.

A mental disorder characterized by social anxiety, thought disorder, paranoid ideation, derealization and transient psychosis.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pearson, J. The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Nat Rev Neurosci 20 , 624–634 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0202-9

Download citation

Published : 05 August 2019

Issue Date : October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0202-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Representations of imaginary scenes and their properties in cortical alpha activity.

- Rico Stecher

- Daniel Kaiser

Scientific Reports (2024)

Predicting the subjective intensity of imagined experiences from electrophysiological measures of oscillatory brain activity

- Derek H. Arnold

- Blake W. Saurels

- Dietrich S. Schwarzkopf

Visual hallucinations induced by Ganzflicker and Ganzfeld differ in frequency, complexity, and content

- Oris Shenyan

- Matteo Lisi

- Tessa M. Dekker

Volume development changes in the occipital lobe gyrus assessed by MRI in fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly correlate with neurological development in infancy and early childhood

- Zhaoji Chen

- Hongsheng Liu

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

Neural signatures of imaginary motivational states: desire for music, movement and social play

- Giada Della Vedova

- Alice Mado Proverbio

Brain Topography (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

CogniFit Blog: Brain Health News

Brain Training, Mental Health, and Wellness

Is Photographic Memory Real? Case Studies & Brain Processes

A photographic memory is usually used to describe when someone has the remarkable ability to recall visual information in great detail. Pop culture today portrays geniuses as those with photographic memories . B ut do our brains actually hold onto memories with inner photos or videos?

Let’s take a closer look…

Perception vs. Reality

In the world of neuroscience, Photographic memory is also known as eidetic imagery .

It’s the ability to remember an unlimited amount of visual information in great detail. A camera can freeze a moment in time in the form of a photograph. Someone with a photographic memory is supposed to be able to take mental snapshots and then later recall these snapshots without error.

However, according to the University of Chicago, San Diego Professor Larry Squire (who specializes in Psychiatry, Neuroscience, and Psychology) the brain simply does not actually work this way .

In Professor Squire’s lab, he has asked people who think they have photographic memories to read two or three lines of text. After, they had to report the text in reverse order. If memory works like a photograph, then these people should be able to accomplish the task with ease.

However, none of the participants could do this successfully.

For Professor Squire, “Memory is more like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle than a photograph. To recollect a past event, we piece together various remembered elements and typically forget parts of what happened (examples: the color of the wall, the picture in the background, the exact words that were said)…We are good at remembering the gist of what happened and less good at remembering (photographically) all the elements of a past scene.”

And this works to our advantage.

Our brains sift through what is important for us to remember and holds onto it. But it also throws away any unneeded details.

To show that photographic memory is non-existent among most people, cognitive psychologist Adriaan de Groot did an experiment with expert chess players to test their memory functioning . The players were first shown a chessboard with pieces on it for a brief period (about 15 seconds). Next, they had to reconstruct what they had seen on a new chessboard.

The expert chess players succeeded at this task with higher efficiency than novice players.

De Groot hypothesized that the experts had developed an enhanced ability to memorize visual information. In another experiment, the expert chess players were asked to do the same thing. However, this time, they were shown boards with pieces arranged in ways that would never occur in a game of chess.

Not only did their ability to remember the positions go down, but it dropped to the level of the novice players. De Groot concluded that the original, enhanced performance of the chess players came from their ability to mentally organize the information they had observed, not from any ability to “photograph” the visual scene.

How to Explain Cases of Photographic Memory

There have been a few well-documented cases of such remarkable photographic recall, such as “S.” This person was subject of Alexander Luria’s book, The Mind of a Mnemonist . He could memorize anything from the books on Luria’s office shelves to complex math formulas. Luria also documents a woman named “Elizabeth,” who could mentally project images composed of thousands of tiny dots onto a black canvas.

Both also had the ability to reproduce poetry in languages they could not understand years after seeing it written. This type of recall seems to be connected to the phenomenon of flashbulb memory . This means in highly emotional situations, people tend to remember events so vividly that the memories take on photographic quality.

Until recently, such memories were thought to be permanent, always strong in quality. However, recent studies have indicated that over time, people’s memories of such events will inevitably fade away.

People vary in their ability to remember the past.

In the article How to Improve Your Short-Term Memory: Study Tips to Remember Everything , we go over how pieces of information go through a series of stages before they are retained in your long-term memory:

- First, the information is sent as a sensory input to your visual system

- Then it is received by the visual cortex

- Next, it is processed by your short-term memory

- Finally, it is stored in your long-term memory

How well we remember things largely depends on how well we pay attention when information is presented to us. Also, how much we replay/connect material affects our memory as well .

Since there are only isolated examples of people with eidetic memory throughout the study of neuroscience , many have concluded that there isn’t any explanation for how this phenomenon works neurologically.

In these rare cases, visual information gets stored as an actual image in the sensory input/reception stage. Since photographic memory involves seeing visual images , it must be on the very basic sensory level that eidetic memory functions.

The Neuroscience Behind Photographic Memory

Neuroscience researchers hypothesize that photographic memory involves something in the brain being wired incorrectly. This has caused sensory stimuli to last in the memory for longer durations than most people.

Memory is thought to be facilitated by changes at the neuronal level due to long-term potentiation. Over time, the synapses that work to hold onto our memories are strengthened through repeated usage, producing long-term memories.

Normally, this induction takes many rounds of stimulation to start working so our brain can hold onto memories for long periods of time. This could be a reason why we don’t remember many events of our childhood.

Neuroscientists assume that people with photographic memories have a genetic mutation that lowers their threshold for long-term potentiation to hold onto memories. This then results in more visual images being stored as sensory memories and then long-term memories in the brain. Multiple stimulations do not seem to be necessary to retain the visual images; rather, one brief presentation of a stimulus would be sufficient.

Future Research on Photographic Memory

So, is photographic memory real?

It may be so rare that it appears to be almost fictional. Mostly because it could be the result of an uncommon genetic mutation.

Advancing the study of photographic memory requires scientists to find more subjects with unusual memory abilities. One recent case is that of “AJ”. This woman seems to remember every detail of even the most trivial events during her lifetime.

Neurological testing may yield a greater understanding of what causes such clear and detailed memories to form.

With neuroscience technology increasing and the hope that more people with exceptional memories will come forward, it is possible that more research can be done to answer interesting questions about photographic memory.

- Category: Brain Health & Neuroscience

- Tag: brain health , improving memory , long-term memory , memory , Neuroscience

Pin It on Pinterest

Share this post with your friends!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Photographic Memory: The Effects of Volitional Photo Taking on Memory for Visual and Auditory Aspects of an Experience

Affiliations.

- 1 1 Stern School of Business, New York University.

- 2 2 Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California.

- 3 3 The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

- 4 4 The Yale School of Management, Yale University.

- PMID: 28650721

- DOI: 10.1177/0956797617694868

How does volitional photo taking affect unaided memory for visual and auditory aspects of experiences? Across one field and three lab studies, we found that, even without revisiting any photos, participants who could freely take photographs during an experience recognized more of what they saw and less of what they heard, compared with those who could not take any photographs. Further, merely taking mental photos had similar effects on memory. These results provide support for the idea that photo taking induces a shift in attention toward visual aspects and away from auditory aspects of an experience. Additional findings were in line with this mechanism: Participants with a camera had better recognition of aspects of the scene that they photographed than of aspects they did not photograph. Furthermore, participants who used a camera during their experience recognized even nonphotographed aspects better than participants without a camera did. Meta-analyses including all reported studies support these findings.

Keywords: auditory memory; autobiographical memory; experiences; open data; photographs; visual memory.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Point-and-shoot memories: the influence of taking photos on memory for a museum tour. Henkel LA. Henkel LA. Psychol Sci. 2014 Feb;25(2):396-402. doi: 10.1177/0956797613504438. Epub 2013 Dec 5. Psychol Sci. 2014. PMID: 24311477

- The role of visual imagery in autobiographical memory. Greenberg DL, Knowlton BJ. Greenberg DL, et al. Mem Cognit. 2014 Aug;42(6):922-34. doi: 10.3758/s13421-014-0402-5. Mem Cognit. 2014. PMID: 24554279

- How taking photos increases enjoyment of experiences. Diehl K, Zauberman G, Barasch A. Diehl K, et al. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016 Aug;111(2):119-40. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000055. Epub 2016 Jun 6. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016. PMID: 27267324

- Memory for sound, with an ear toward hearing in complex auditory scenes. Snyder JS, Gregg MK. Snyder JS, et al. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2011 Oct;73(7):1993-2007. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0189-4. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2011. PMID: 21809152 Review.

- Capturing life or missing it: How mindful photo-taking can affect experiences. Diehl K, Zauberman G. Diehl K, et al. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022 Aug;46:101334. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101334. Epub 2022 Mar 5. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022. PMID: 35468368 Review.

- Outsourcing Memory to External Tools: A Review of 'Intention Offloading'. Gilbert SJ, Boldt A, Sachdeva C, Scarampi C, Tsai PC. Gilbert SJ, et al. Psychon Bull Rev. 2023 Feb;30(1):60-76. doi: 10.3758/s13423-022-02139-4. Epub 2022 Jul 5. Psychon Bull Rev. 2023. PMID: 35789477 Free PMC article. Review.

- Understanding Why Tourists Who Share Travel Photos Online Give More Positive Tourism Product Evaluation: Evidence From Chinese Tourists. Tang X, Gong Y, Chen C, Wang S, Chen P. Tang X, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Apr 8;13:838176. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.838176. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 35465489 Free PMC article.

- Hunters and Gatherers of Pictures: Why Photography Has Become a Human Universal. Kislinger L, Kotrschal K. Kislinger L, et al. Front Psychol. 2021 Jun 8;12:654474. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.654474. eCollection 2021. Front Psychol. 2021. PMID: 34168589 Free PMC article.

- How Digital Food Affects Our Analog Lives: The Impact of Food Photography on Healthy Eating Behavior. Andersen T, Byrne DV, Wang QJ. Andersen T, et al. Front Psychol. 2021 Apr 6;12:634261. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.634261. eCollection 2021. Front Psychol. 2021. PMID: 33889111 Free PMC article. Review.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources, other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

The Truth About Photographic Memory

It's impossible to recover images with perfect accuracy..

By William Lee Adams published March 1, 2006 - last reviewed on June 9, 2016

59-year-old Akira Haraguchi recited from memory the first 83,431 decimal places of pi, earning a spot in the Guinness World Records.

He must have a photographic memory, right? Not so. According to mounting evidence, it's impossible to recall images with near perfect accuracy.

Certainly, some people do have phenomenal memories. Chess masters can best multiple opponents while blindfolded. Super card sharks can memorize the order of a shuffled deck of cards in less than a minute. But people with Herculean memories tend to be adept at one specific task—i.e., a person who memorizes cards may be inept at recognizing faces.

Alan Searleman, a professor of psychology at St. Lawrence University in New York, says eidetic imagery comes closest to being photographic. When shown an unfamiliar image for 30 seconds, so-called "eidetikers" can vividly describe the image—for example, how many petals are on a flower in a garden scene. They report "seeing" the image, and their eyes appear to scan across the image as they describe it. Still, their reports sometimes contain errors, and their accuracy fades after just a few minutes. Says Searleman, "If they were truly 'photographic' in nature, you wouldn't expect any errors at all."

While people can improve their recall through tricks and practice, eidetikers are born, not made, says Searleman. The ability isn't linked to other traits, such as high intelligence . Children are more likely to possess eidetic memory than adults, though they begin losing the ability after age six as they learn to process information more abstractly.

Although psychologists don't know why children lose the ability, the loss of this skill may be functional: Were humans to remember every single image, it would be difficult to make it through the day.

- Find Counselling

- Find Online Therapy

- South Africa

- Johannesburg

- Port Elizabeth

- Bloemfontein

- Vereeniging

- East London

- Pietermaritzburg

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Photography and Memory

- Living reference work entry

- Latest version View entry history

- First Online: 13 September 2023

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Ali Shobeiri 3

76 Accesses

The affinity between photography and memory is rather axiomatic: We take photos to preserve our memories. This formulation considers photographs as aide-mémoire and photography as a mnemotechnique . Such a basic analogy, however, falls short in explaining the spatiotemporality and materiality of photography and overlooks the mediated aspects of memory in narrating the past. The difficulty with describing the conjunction of memory and photography lies in the fact that neither of them has a static essence: Both remembering and photography are inherently dynamic processes. While for some the photograph simply is a representational image that embodies past events, for others the photograph’s materiality and social uses are equally crucial in the way it continually reshapes our memories. In addition, debates on “prosthetic memory,” “postmemory,” and trauma have already shown how photography plays a role in the disembodied, transgenerational, and retroactive operations of memory work. To classify diverse approaches toward memory and photography without ignoring the dynamic aspects of either of them, this entry is divided into two parts: “conceiving photography through memory” and “perceiving memory through photography.” While the first section explains how the medium of photography has been historically defined via its approaches to memory and remembrance, the second section shows how some salient views on memory are largely founded on photographic lexicons and metaphors. Among others, the first part draws on the work of thinkers such as Siegfried Kracauer, Roland Barthes, and Elizabeth Edwards, and the second part discusses the work of Sigmund Freud, Marianne Hirsch, and Ulrich Baer.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Baer U (2005) Spectral evidence: the photography of trauma. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Google Scholar

Barthes R (2000) Camera Lucida. Vintage Books, London. (Originally published in French in 1980, under the title of La Chamber Claire)

Batchen G (1997) Burning with desire: the conception of photography. MIT Press, Cambridge

Bate D (2010) The memory of photography. Photographies 3(2):243–257

Article Google Scholar

Bazin A (1967) Ontology of the photographic image. In: Bazin A (ed) What is cinema. University of California Press, Berkeley/Los Angeles, pp 9–17

Benjamin W (1999) Little history of photography. In: Jennings MW, Eiland H, Smith G (eds) Walter Benjamin: selected writings: volume 2, part 2. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 507–530

Berger J (2002) The ambiguity of the photograph. In: Askew K, Wilk R (eds) The anthropology of the media. Blackwell, Oxford

Berger J (2013) Understanding of a photograph, John Berger. Penguin Books, London

Caruth C (2016) Unclaimed experience: trauma, narrative and history. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

Book Google Scholar

Cavell S (1979) The world viewed: reflections on the ontology of film. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Ceila L (1997) Prosthetic culture: photography, memory and identity. Taylor & Francis, Abingdon

de Duve T (1978) Time exposure and snapshot: the photograph as paradox. October 5(1):113–125

Edwards E (2001) Raw histories: photographs, anthropology and museums. Berg, Oxford

Edwards E (2006) Photographs and the sound of history. Vis Anthropol Rev 21(1–2):27–46

Edwards E (2009) Photographs as objects of memory. In: Candlin F, Guins R (eds) The object reader. Routledge, New York, pp 331–341

Edwards E (2012) Objects of affect: photography beyond the image. Annu Rev Antropol 41(1):221–234

Edwards E, Hart J (eds) (2004) Photographs objects histories: on the materiality of images. Routledge, London

Freud S (1925) The mystic writing-pad. Metapsychol Theory Psychoanal 11(1):427–433

Gunning T (2004) What’s the point of an index? Or, faking photographs. Nordicum Rev 25(1):39–49

Hirsch M (2001) Surviving images: holocaust photographs and the work of postmemory. Yale J Criti 14(1):5–37

Hirsch M (2012) The generation of postmemory: writing and visual culture after the holocaust. Columbia University Press, New York

Holmes OW (1859) The Stereoscope and the Stereograph. The Atlantic Monthly 3(2):738–748

Kracauer S (2014) Photography. In: Despoix P, Zinfert M (eds) The past’s threshold: essays on photograph. Diaphanes, Zurich, pp 27–44. (Originally published in German in 1927, as an assay in Frankurter Zeitung)

Kuhn A, McAllister KE (eds) (2006) Locating memory: photographic acts. Berghahn Books, New York

Landsberg A (1995) Prosthetic memory: Total recall and blade runner. Body Soc 1(3–4):175–189

Metz C (2003) Photography and fetish. In: Wells L (ed) The photography reader. Routledge, New York, pp 138–148

Mitchel WJT (1992) The reconfigured eye: visual truth in the post-photographic era. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Olick J, Robbins J (1998) Social memory studies: from ‘collective memory’ to the historical sociology of mnemonic practices. Annu Rev Sociol 24:105–140

Olin M (2002) Touching photographs: Roland Barthes’s mistaken identification. Representations 80:99–118

Sekula A (1984) On the invention of photographic meaning. In: Bergin V (ed) Thinking photography. Macmillan, London, pp 84–109

Shevchenko O (2015) The mirror with a memory: placing photography in memory studies. In: Lisa TA, Hagen T (eds) Routledge international handbook of memory studies. Routledge, London, pp 294–309

Sliverman K (2000) World spectators. Cornel University Press, Stanford

Sontag S (1977) On photography. Penguin Books, London

Trachtenberg A (2008) Through a glass darkly: photography and cultural memory. Soc Res Int Q 75(1):111–132

van Dijck J (2007) Mediated memories in the digital age. Stanford University Press, Stanford

van Dijck J (2008) Digital photography: communication, identity, memory. Vis Commun 7(1):1–21

White H (1978) The historical text as a literary artifact. In: Tropics of discourse. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Chapter Google Scholar

Wigoder M (2001) History begins at home: photography and memory in the writings of Siegfried Kracauer and Roland Barthes. Hist Memory 13(1):19–59

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for the Arts in Society (LUCAS), Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

Ali Shobeiri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ali Shobeiri .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science and Tech, Trondheim, Norway

Lucas M. Bietti

Institute of Culture and Memory Studies, Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Martin Pogacar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Shobeiri, A. (2024). Photography and Memory. In: Bietti, L.M., Pogacar, M. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Memory Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93789-8_33-2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93789-8_33-2

Received : 03 April 2023

Accepted : 14 April 2023

Published : 13 September 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-93789-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-93789-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93789-8_33-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93789-8_33-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Photographic Memory: The Effects of Volitional Photo Taking on Memory for Visual and Auditory Aspects of an Experience

Psychological Science¸ August 2017, Vol 28, Issue 8, p.1056 - 1066

29 Pages Posted: 18 Sep 2017

Alixandra Barasch

INSEAD; New York University (NYU) - Leonard N. Stern School of Business

Kristin Diehl

University of Southern California - Marshall School of Business

Jackie Silverman

University of Pennsylvania

Gal Zauberman

Date Written: September 13, 2017

How does volitional photo taking affect unaided memory for visual and auditory aspects of experiences? Across one field and three lab studies, we found that, even without revisiting any photos, participants who could freely take photographs during an experience recognized more of what they saw and less of what they heard, compared with those who could not take any photographs. Further, merely taking mental photos had similar effects on memory. These results provide support for the idea that photo taking induces a shift in attention toward visual aspects and away from auditory aspects of an experience. Additional findings were in line with this mechanism: Participants with a camera had better recognition of aspects of the scene that they photographed than of aspects they did not photograph. Furthermore, participants who used a camera during their experience recognized even nonphotographed aspects better than participants without a camera did. Meta-analyses including all reported studies support these findings.

Keywords: photographs, visual memory, auditory memory, autobiographical memory, experiences

JEL Classification: M30

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

INSEAD ( email )

Boulevard de Constance Fontainebleau, 77305 France

New York University (NYU) - Leonard N. Stern School of Business ( email )

44 West 4th Street Suite 9-160 New York, NY NY 10012 United States

Kristin Diehl (Contact Author)

University of southern california - marshall school of business ( email ).

701 Exposition Blvd Los Angeles, CA California 90089 United States

HOME PAGE: http://https://www.marshall.usc.edu/personnel/kristin-diehl

University of Pennsylvania ( email )

Philadelphia, PA 19104 United States

Yale ( email )

165 Whitney Avenue New Haven, CT 06511 United States

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, usc marshall school of business research paper series.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Cognitive Social Science eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Biology & Cognitive Science eJournal

Psychological anthropology ejournal, cognitive psychology ejournal, visual anthropology, media studies & performance ejournal.

Advertisement

Did you know? Fewer than 100 people have a photographic memory

By Alexander McNamara and Matt Hambly

25 May 2021

Barbara Ferra Fotografia/Getty Images

Photographic memory is the ability to recall a past scene in detail with great accuracy – just like a photo. Although many people claim they have it, we still don’t have proof that photographic memory actually exists. However, there is a condition called Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) that allows people to recall past events in detail, along with the exact dates when they occurred. For example, they may be able to tell you what they ate for lunch on 1 May 1999 and what day of the week it was (Saturday). But HSAM has been identified in fewer than 100 people worldwide, and while their memories are exceptional, they still aren’t as reliable as photographs.

The East Antarctic plateau is the coldest place on Earth

Ted Scambos, NSIDC

The coldest temperature ever recorded was a frosty -94°C, taken at the East Antarctic plateau, a region that stretches for more than 1000 kilometres. This measurement means the plateau is the coldest place on Earth – not that anyone was actually there to record such a temperature, though. The reading was collected using data from satellites across Dome Argus and Dome Fuji, two ice domes that sit at thousands of metres above sea level. Results suggested the air temperature could be around -94°C, but researchers think that the dry air around the area could cause temperatures to get even colder.

Queen bees can lay more than 1500 eggs in a day

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Queen honeybees live for up to seven years and can lay more than 1500 eggs a day, which equates to more than their body weight. Rather than working, like the vast majority of colony members, queens spend their lives devoted to laying eggs while other bees serve them. Instead of pollen and honey, the queen is fed royal jelly, which workers secrete from glands in their heads. When a queen grows old, a colony will select a new one, but in some colonies there may be multiple new queens, who have to fight each other to the death. The survivor will fly to a drone congregation area and mate with around a dozen drones, storing up to 6 million sperm in her body.

Laughing gas may have ended the last glacial period

Monica Bertolazzi/Getty Images

Laughing gas, otherwise known as nitrous oxide , has been used as an anaesthetic since the 19th century. These days, it is most commonly found in small, steel cartridges sold to the catering industry for making whipped cream. However, nitrous oxide is also a potent greenhouse gas and ozone-depleting chemical. Although it is present in the atmosphere at much lower concentrations than carbon dioxide – just 330 parts per billion – it has 300 times the heat-trapping capability. Indeed, a pulse of nitrous oxide released from plants 14,500 years ago may have hastened the end of the last glaciation.

We don’t necessarily yawn because we are tired

Gints Ivuskans / Alamy

We tend to think of yawning as a sign of being tired or bored. That probably explains the popular perception that it is a way to get more oxygen into the blood to increase alertness. However, psychologist Robert Provine at the University of Maryland tested this idea and found people were just as likely to yawn when breathing air high in oxygen. A closer look at when people yawn suggests another explanation. It turns out that most spontaneous yawning actually happens when we are limbering up for activity such as a workout, performance or exam, or simply when we wake up. That has led to the idea that yawning helps us gear up by increasing blood flow to the brain.

The placebo effect can depend on whether a pill is colourful

Derek Croucher / Alamy

The placebo effect is the mysterious reduction in a patient’s medical symptoms via the power of suggestion or expectation, the cause of which remains unexplained. However, what we do know is that a number of different factors can affect the power of the placebo effect . It can be triggered by administering pills, injections or surgery, or even just an authority figure assuring a patient that a treatment will be effective. In fact, experiments have shown that the power of the placebo effect depends on surprising factors like the appearance of tablets. For example, colourful pills work better as a placebo than white ones.

- environment /

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Environment

New scientist recommends a moving antarctica memoir, breaking the ice.

Subscriber-only

Why overcoming your cynicism could be key to a healthier, happier life

Glaciers in the Andes are the smallest they’ve been for 130,000 years

We're ignoring easy ways to encourage children to be physically active

Popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

How authentic are photographic memories?

Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Aston University

Disclosure statement