Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 December 2020

Project-based learning: an analysis of cooperation and evaluation as the axes of its dynamic

- Berta de la Torre-Neches ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7305-362X 1 ,

- Mariano Rubia-Avi 1 ,

- Jose Luis Aparicio-Herguedas 2 &

- Jairo Rodríguez-Medina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6466-5525 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 7 , Article number: 167 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

11 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

Project-based learning is an active method that develops the maximum involvement and participation of students in the learning process. It requires the teacher to energize the learning scenario by promoting the cooperation of students to investigate, make decisions and respond to the challenges of the project. It also requires activating an evaluation system that promotes awareness, reflexivity and a critical spirit, facilitating deeper learning. This case study aims to understand the functioning of cooperative work established during the application of the method, as well as to know how the evaluation process progresses in the perspective of a group of teachers of secondary education that set up this methodology in their classes. The data obtained from interviews with the teachers involved in the study, teachers’ notebooks, and open-question questionnaire applied to high-school students are analyzed. Although the students were organized in small groups in order to develop their collaborative skills, intragroup frictions and conflicts were not sufficiently addressed or supervised in time by the teachers, thus resulting in an incomplete development of the synergies and collaboration necessaries to the project. From the point of view of the evaluation, the importance of the implementation of training and shared evaluation systems is well recognized, although a more traditional evaluation model, which does not sufficiently address the project development process prevails, and the value of the qualification on the final product achieved still weights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elementary school teachers’ attitudes towards project-based learning in China

Community-oriented engineering co-design: case studies from the Peruvian Highlands

Students’ structured conceptualizations of teamwork in multidisciplinary student teams using concept maps

Introduction.

As a result of the crisis scenario that began in Spain in 2007, the need to incorporate to the Secondary Education stage some subjects with economic contents, was posed in order to introduce and make students understand the socio-economic circumstances in the world. Simultaneously, teaching methods have been incorporating some learning methodologies that aim to make students able to solve, with involvement, the problems presented to them (Martín and Rodríguez, 2015 ). Some of these methods orient learning towards a competitive character such as cooperative methodologies, gamification or project-based learning (PBL) (Hernández March, 2006 ).

The PBL method is a methodological alternative that involves direct contact with the object of study and ends with the realization of a work project by the students initially proposed by the teacher (Bell, 2010 ), applying knowledge and skills and developing an attitude of commitment (Sánchez, 2018 ). In order to do this, students analyze the topic raised, think about it, organize themselves, search for information, work as a team and make decisions. It is, therefore, intended to promote knowledge of the contents as well as the management of skills and attitudes, learning to mobilize those resources said in situation and to solve problems (Perrenoud, 2008 ).

The experience carried out requires students to face real-life problem statements through activities that suit their interests (Krajcik and Blumenfeld, 2006 ), find and use tools to address them and act collaboratively to propose solutions through an action plan (Barret, 2005 ; Bender, 2012 ; Blumenfeld et al., 1991 ). Traditional training models are based in the premise that students have to know the content in order to apply it in solving a problem. The PBL reverses this order and considers that students obtain the knowledge while solving a problem (Jonassen, 2011 ), an aspect that results in a higher quality of the information they handle to solve it, since it is shared, discussed and applied in a concrete situation (Thomas, 2000 ).

Thus, through PBL, students plan, discuss, and implement projects that have real-world impact and are significant to them (Blank, 1997 ; Dickinson et al., 1998 ). They implement skills for the management of interpersonal and team relationships, the teacher acting as a guide and counselor during the learning process (Kolmos, 2012 ; Thomas, 2000 ). This allows students to think about their proposals, develop them and become aware of the process itself and everything that it implies beyond the results achieved (Brundiers and Wiek, 2013 ; García et al., 2010 ).

In this way, the acquisition of social skills, empathetic behavior, dialog and listening (Belland et al., 2006 ), the development of critical and reflective thinking (Mergendoller et al., 2006 ) is favored by activating competencies such as collaboration, decision-making, organization and group responsibility (Blank, 1997 ; Dickinson et al., 1998 ), contributing to the development of a more motivating and participatory learning climate (Lima et al., 2007 ).

This methodological aspect requires, in parallel, the review of the evaluation systems; it appears as necessary to leave behind the traditional cumulative models to introduce a new model of more formative, shared and authentic evaluation that is able to guarantee a greater involvement of the students in the development of their and their peer’s learning process (Brown and Race, 2013 ). An authentic evaluation offers the students opportunities to learn through the evaluation process planned and directed by the teacher. When the evaluation system is carefully designed to articulate with the learning results that are expected to be achieved, it is possible to obtain benefits in terms of greater participation and helps students to advance in the development of their knowledge, skills and attitudes (Brown, 2015 ).

Cooperation as the basis of project-based learning

One of the essential aspects of developing the PBL is the management of cooperation between the group participants, an aspect that must be guaranteed and supervised by offering sufficient feedback (Thomas, 2000 ). For Orlick ( 1986 ) cooperation is directly related to communication, cohesion, trust and skills development for positive social interaction.

However, Díaz-Barriga and Hernández ( 2002 ) consider that group work, which teachers frequently launch in project initiatives, does not necessarily implies true cooperation and there are many interpersonal problems that students face (Prince and Felder, 2006 ). This aspect prevents a real learning of collaboration and its application in action to address the shared phase of project management.

Burdett ( 2007 ) considers that, sometimes within the group, interpersonal relationships are strained since participation in group work involves much more than each member’s knowledge on a given subject: It involves listening, negotiating, giving in; ultimately, skills that favor the dynamics of group work. Such situations of tension and intragroup crises jeopardize the assignment to be developed and the effectiveness of group synergy, as established by Del Canto et al. ( 2009 ), Jhen and Mannix ( 2001 ), Kerr and Bruun ( 1983 ), Putnam ( 1997 ), and Velázquez ( 2013 ) and those are grouped around five critical dimensions: Differences in individual capacities to complete assignments, resulting in the stowaway effect ; imbalance in the functions to be performed; early abandonment in completing assignments due to unresolved discrepancies; struggle to make one’s own ideas prevail and lack of communicative skills.

Also for Kerr and Bruun ( 1983 ) and Slavin ( 2014 ) tensions arise from the lack of a follow-up by the teacher in the group work process entrusted to their students, not monitoring the performance and contribution of each member by thriving the aforementioned stowaway effect, imbalances in workloads borne by each member and unresolved crises in interpersonal relationships, not benefiting the task management, the project development and its fair evaluation.

Intragroup conflicts often cause widespread student complaints, lack of motivation, frustration, and occasionally, a preference for individual work that does seem to guarantee the fair evaluation of the assignment (Gámez and Torres, 2012 ; McConnell, 2005 ).

That is why establishing initial cooperative learning dynamics to learn how to collaborate, assume new responsibilities, communicate and assertively express ideas (Velázquez, 2013 ), is essential to get started in the PBL methodology. Johnson et al. ( 1999a ) define cooperative learning as a work-based methodology in small, usually heterogeneous groups in which students work together to improve their own and other member’s learning.

Several authors understand cooperative learning as an active methodology that favors the reflection of students while completing the assignment; not only des it allow to achieve academic goals, but also social objectives, it stimulates interaction through the proposal of small groups and guides the realization of a type of group work, structured and monitored, to favor the learning of all the members of the group without exception (Dyson, 2002 ; Johnson et al., 1999b ; Kagan, 2000 ; Pujolàs, 2009 ).

According to Johnson and Johnson ( 1999 ) the management of cooperative learning by teachers requires, for its effectiveness, guarantees in the management of positive interdependence, making the students understand that work benefits colleagues by prioritizing “us” over “I”, proactive interaction, individual responsibility, interpersonal skills, and group processing at the end of the work sessions performed.

The teacher establishes a structured process of true cooperation easing the development of academic objectives, but also other competitive objectives: cooperation, communication, social skills (Walberg and Paik, 2002 ).

It is important to note in this regard the role of the evaluation on the projects implemented, developed and presented. Pérez-Pueyo and López-Pastor ( 2017 ) propose a model of formative evaluation through the use of cooperative projects, in which a further step is taken in the autonomy of the students by fully involving them in the teaching process through shared tutoring, especially when the realization of projects that require a lot of involvement or levels of complexity in their realization is encouraged. In addition, the use of tools such as auto evaluations and group co-evaluations (Hamodi et al., 2015 ), allow the teacher to give more effective feedback during the process, based on the information provided by the students.

Based on the contributions of the various authors cited above, who understand cooperative learning as an active methodology that allows students to achieve not only academic goals but also social objectives, thus promoting the learning for all the students without exceptions, the present study aims to achieve the following objectives: Understanding the functioning of cooperative work present in the development of the operational dynamics of the PBL launched.

Knowing how the formative evaluation process develops in the operational dynamics of the PBL.

Participants and context

The study included 16 students on their fourth year of Secondary Education (with an average of 15 years old, 8 females and 8 males) attending Cristo Rey Polytechnic Institute in the city of Valladolid, and taking the elective subject of Economics. Also three male teachers and two female teachers (ages [35–57]) who teach at the same center and stage, in which they apply PBL as an active methodology. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

During the development of the research, the ability of students to work through PBL was tested, applying the academic project entitled My Business Plan , throughout the subject of Economics in the compulsory secondary education stage. The students were arranged in groups of 4 to 5 members with different capacities and potentialities.

These heterogeneous groups allowed the development of various skills by the students, with the intention of improving them together with intragroup interpersonal relationships.

Data collection and information analysis tools

An in-depth interview was designed for teachers who were to some extent incorporating PBL as an active methodology in the development of their subjects. They thus form a representation of the faculty imparting subjects such as Economics, Geography and History, Biology and Geology, Physics and Chemistry and Philosophy. At the same time, an open-question questionnaire was designed for students. Finally, a reflexive diary was drafted in which observations were recorded from the experiences carried out in class.

In relation to the analysis of the information obtained, the ATLAS.ti software has been used, confectioning a work of textual analysis of the transcripts of teachers’ interviews, the answers on the open questions of the questionnaire answered by the students, alongside with the teacher’s own reflexive diary.

On the three primary documents, a coding process is carried out inductively and deductively through two cycles (Miles et al., 2014 ). Thus, during the process, a constant circular relationship between the codes already obtained and the new ones I created, refining the concepts, grouping them, to infer in higher-level constructs as groups of explanatory codes (Kalpokaite and Radivojevic, 2019 ).

The codes obtained during the first coding cycle were analyzed critically and independently by the four researchers participating in the study establishing a thoughtful debate. Continuous feedback between researchers and their ongoing participation in the regeneration and refinement of codes and groups of codes supported the credibility, reliability and transparency of the research (Neal et al., 2015 ).

It was considered that saturation had been reached at the time where comparisons between the data ceased to show new relationships and properties between them, depleting that representative wealth of a circular analytical process (Flick, 2007 ).

In order to address the credibility aspects of the research in relation to the interpretative difficulties of the phenomenon studied (Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ), a structure of prolonged over time experimentation was developed, with the presence of the researcher at the location, maintaining the same methodological order, establishing her figure as an observer teacher during the time of research; in the analysis of the data, a process of triangulation was developed from the three aforementioned sources of documentary data, this allowing the contrast of the discoveries.

Forty-one explanatory codes of the phenomenon under investigation were established and grouped around four categories: Learning, interaction-collaboration, motivation, organization.

The use of the ATLAS.ti software as a code co-coordinate tool was convenient, allowing to observe how four codes of the categories Learning and Interaction-Collaboration related to each other: cooperation, conflicts, evaluation and project. Their relational study allows to reflect critically on the several handicaps found and whose consideration is essential for the applicability of the practice.

Thus, to address the first objective of the study—knowing the functioning of cooperative work in the development of the operational dynamics of the PBL launched—taking as a starting point the perceptions of the teachers interviewed and the relationships they establish between PBL and cooperation, they show a formula of practical application using cooperative structures in the form of small groups, which they consider makes it easier for students to encourage communication, to develop skills for interpersonal relationships, as well as individual and group responsibility in the fulfillment of the assignments proposed.

(…) I mix it at first with cooperative work, with small groups, with cooperative structures because being such dense subjects (…) and at the end of the school year, the last quarter, we already work on the project (Male Teaching Interview. 4:69).

In the groups, the smaller the better they work, (I would recommend) four tops, like last year (…) this allows everyone to work, if they are too many, the tasks get diluted and if there are very few, and it also happens sometimes, if one is sick or misses class for some reason for too many days, the groups gets resented… then it rally allows to work on relationships and influences the quality of learning very clearly by what I say… one is good at one thing, the other is good at some other thing, and they end up learning from each other (Male Teaching Interview. 4:358).

The same teacher considers, in the application of the methodology, the creation of small working groups, defending this formula as very valuable to develop the communicative and negotiation abilities to reach agreements and coordinate with others, the students winning from an experiential point of view, in socialization and interaction resources.

I divided the class into 4 groups of 4 students each (…), they had ten minutes to explain in front of the rest of the classmates what their business model was by answering various questions. (…) the idea of the project is that they are the ones who work on this concept throughout the course and thus gradually become familiar with that environment and its vocabulary (Reflexive Diary. 3:394).

Through the PBL they work together, they talk more, they must agree on different aspects, and it requires coordination, that is, an effort of all of them, not depending so much on their individual abilities; this approach is very different from the master class, and I do believe that, from a social point of view, socialization develops more and better this way (Reflexive Diary. 4:412).

However, the same teachers interviewed acknowledge that, during the development of the methodology, applying group work strategies for cooperation, numerous frictions and interpersonal conflicts are often triggered within the working groups. A closer attention is put on those students who does not follow the intended pattern of behavior and unleash conflict because they do not assume or carry out their workload.

The most negative aspect are those students who do not want to participate, or find it difficult to participate, or do not get involved and seriously harm the group, and sometimes problems such as friction and conflicts can appear among them for this reason; working individually, logically, there is no such problem (Female Teacher Interview. 4:150).

That student who is a little lazier, they can take advantage of the group work situation so that others work a little for them (Male teacher interview. 4:343).

This aspect is also observed and recorded by the teacher in her reflexive diary, acknowledging incidents that are likely to occur in the groups, generating some interpersonal conflict and influence on group performance to carry out the tasks of the project.

There is a group of four boys who you have to tell off and who I do not intend to bring together in the future for the groups of the project (Reflexive Diary. 3:296).

Z (…) during group work he plays with the table, gets distracted by what other teammates do (…). I think he’s a boy who is too easily distracted and annoys his peers (Reflexive Diary. 3:160).

The students themselves consider that the project suffers when situations in which not all members of the group work in tune occur, creating imbalances in the effort made and in the management of the workloads and involvement assumed, which have an impact not only on the realization of the tasks and assignments and their final evaluation, but also on the intragroup climate.

I don’t like it when there’s someone in my group who doesn’t work and gets the same grade as me or we fail the project all because of him, because we don’t all work equally; sometimes I felt that if I didn’t tell them to do something, they wouldn’t do it (Student Questionnaire. 5:242)

There are groups where only one or two people work and it’s not fair. The rest of them get too comfortable and their work is minimal. I would try watching those who do not work, or not giving them the same grade (Student Questionnaire. 5:123)

When the members of the group do not work, the project can be a disaster; and if a person does not want to do their job then discussions arise; for me the experience is negative because I did work and I did it all by myself (Student Questionnaire. 6:134)

With regard to the second objective of the study, knowing how the formative evaluation process develops in the operational dynamics of the PBL, taking into account the teachers involved in the inclusion of PBL in their teaching practice, it seems to show a difficult development, recognizing the constant presence of tests and evaluations as a generalized tool of measurement of the acquired knowledge. However, it recognizes the value of other competence aspects that must necessarily be considered by applying tools that make it easier for students to raise awareness of the developed learnings, as well as the value of the teacher as a guide who oversees the learning process and controls and leads it.

Evaluation is a complex topic because if you base your work on projects and in the end you give them an exam you are giving more value to the contents and not so much to everything else; that is why for the final evaluation we are already working on taking into consideration the valuable opinions of each one, that of the classmates, the ones shared among students and teachers through auto evaluation practices, co-evaluation and heteroevaluation. In this way they develop their critical ability, their capability to value themselves and others (Male Teacher Interview. 4:323).

I like as a teacher to supervise how they perform the practice of PBL, if everyone works and contributes; then I believe that this work is done in front of them (Male teacher interview. 4:442).

When one works in a group within the classroom the relationship between the students and the teacher is reinforced because they are no longer seen as a figure of authority or a superior, but as a guide who knows, who helps, who collaborates with them and listens to them (Female Teacher Interview. 4:388).

The same teacher in her reflexive diary mentions the use of evaluation practices such as co-evaluation allowing the students to express themselves in order to participate and getting them involved through paper presentations and consequent evaluation between classmates; she also references the heteroevaluation allowing the time for student-teacher dialog based on the assignments and a proposal to solve the project addressed.

What I want is for them to work a little bit and, to make sure of that, as they develop the eight sections on their project, they must make a presentation in front of the rest of their classmates that will be evaluated by themselves and commented by the rest of us (Reflexive Diary. 3:701).

Once the presentations were completed, I gave each group a questionnaire to conduct a co-evaluation on the project addressed; for this evaluation, each group would evaluate the work presented by the other groups, grading representatively each of the sections of the project, so that we could have several grades to be used for the final evaluation of the project (Reflexive Diary. 3:335).

To conclude, the students recognize certain limitations in the evaluation of their work, mainly in a key of a non-follow-up of the process established in the classroom to address the project and the assignments required. They propose solutions to develop a greater control on those people in the group who do not contribute in the realization of the aforementioned assignments, as well as a better management of the final grade that, being the same for the whole group, is detrimental, in their perception, to the formation of a fair value in relation to the unequal effort made. Sometimes the proposed solutions are oriented in an opposite direction to the cooperative spirit that the PBL promotes.

The way I would solve the problem of those colleagues who take advantage of the work of others when working as a group is to set them alone to work; to do their own project; that way, at least they would control those who do not work (Student Questionnaire. 5:168).

As a positive experience, I find working with projects more enjoyable and entertaining; the most negative thing is that it is almost never worked equally, and approximately the same grade is received. It is better to grade individually instead of having a final group grade (Student Questionnaire. 3:356).

The problem with those classmates who take advantage of other’s work when working in a group I would solve by telling the teacher, and giving an individual grade on each assignment done by each group member, specifying who did what (Student Questionnaire. 5:206).

When teaching methods such as PBL are used, in which the teacher poses a question, a challenge or a specific problem connected with the reality that students have to solve (Bell, 2010 ), the degree of involvement of these students seems to increase. In the teaching-learning process, they become the protagonists when they are invited to seek, assess, interpret and share information with the rest of the group members, and they apply a more critical way of thinking, since they are constantly and mutually questioned about why and what are they studying for.

In this sense, the students participate collaboratively in all the proposed assignments: understanding and interpretation of data, collection of information, preparation of partial deliveries, writing of the final report, and oral presentation before others, assessing the problem or challenge proposed with the intention of being able to draw their own conclusions.

In the implementation of these formative dynamics as an alternative to more traditional methodological models, a new way of generating and developing learning is consequently activated, applying a cooperative work model, being the management of group activity to face the project a vital aspect.

In relation to the cooperative dynamics of operation of the PBL experiences developed, the implementation of a methodological model is observed; this model is based, as a starting point, on cooperative structures by which the students are intended to address the project. Such structures materialize in the form of small and heterogeneous groups that seek to guarantee communication between their members (Johnson et al., 1999a ), unleashing a strongly competency learning model (Perrenoud, 2008 ) in which students have to combine the knowledge, skills and attitudes that they learn, in a shared way with their classmates, to face the assignments and carry out the project proposed and presented by the teacher (Bell, 2010 ; Thomas, 2000 ).

In the same way, intentionally, the dynamics proposed by teachers through this methodology intend to trigger learning situations in which negotiation, compromise, listening, agreement-reaching and coordination to make decisions and solve problems are aspects of interaction and socialization necessarily to be encouraged, as established by Belland et al. ( 2006 ) and Bender ( 2012 ).

However, there is a general concern about the management in the classroom of the cooperative structures placed in order to develop the project. Friction, conflicts inherent in group life and the consequence of the cooperation dynamics applied to establish in a shared way the action plan to address the entrusted project are recognized. They identify in certain students a lack of willingness for cooperation and commitment, aspects that generate intragroup tension that for Slavin ( 2014 ) is necessary to keep track of by the teacher during the learning process, for example, paying special attention to those situations in which the stowaway effect occurs (Kerr and Bruun, 1983 ; Slavin, 2014 ).

In this matter, the students themselves describe occasional imbalances in the efforts made to carry out the assignments, the weight of the workloads assumed and, ultimately, a certain lack of harmony when relating to each other when it comes to getting involved in the project. For Del Canto et al. ( 2009 ), Jhen and Mannix ( 2001 ), Putnam ( 1997 ), and Velázquez ( 2013 ) cooperation requires attention on these critical aspects during its development, benefiting the group climate itself and thus, the performance on the assignments. For Gámez and Torres ( 2012 ) and McConnell ( 2005 ), intragroup conflict provokes generalized complaints, loss of enthusiasm and motivation for group members, a source of arguments and frustration, an aspect present in the study in the voice of the students involved.

At the same time, the teaching staff, in relation to the evaluation of the formative dynamics based on the PBL put in place, recognize the importance of paying attention to various competency aspects inherent to the cooperative learning process obtained.

This aspect, in line with what is suggested by Blank ( 1997 ), Dickinson et al. ( 1998 ), Mergendoller et al. ( 2006 ) and Belland et al. ( 2006 ), materializes in the attention to capacities such as empathy, listening, critical thinking, collaboration, decision-making, group responsibility, the teacher assuming a role of leader and guide of all these during the process of learning, as considered by Thomas ( 2000 ), Walberg and Paik ( 2002 ) and Kokotsaki et al. ( 2016 ), supporting the maintenance of a more motivating, participatory and facilitating group work climate (Lima et al., 2007 ).

Despite the use of traditional evaluation dynamics presenting a more finalist nature, such as the test or exam, the teaching staff recognize the value of formative and shared evaluation tools, such as self-evaluation, co-evaluation and heteroevaluation. In this sense, it is observed in the group, not without difficulties (Ertmer and Simons, 2005 ) a certain appreciation for the involvement of the students in the evaluation process, giving them a voice to express their own perception through dynamics such as the presentation of resulting works and shared evaluation in this regard. Paradoxically, the students involved consider a certain lack of follow-up by the teachers on the assignments they carry out and that are a part of the project, in correlation with a conflictive management of the grade in this regard. For Pérez-Pueyo and López-Pastor ( 2017 ) it is necessary to take further steps in the autonomy and personal initiative of the students and their involvement in the evaluation process, the teacher being able to apply techniques such as auto-evaluation, peer evaluation, shared evaluation, self-grading and dialogued grading. The same authors, for example, advocate for intervening in a Secondary Education classroom by applying cooperative projects and final presentations of group papers or events preparation, tutoring in a shared way with their students and involving them in their—and other’s—learning process; The teacher can also complete the methodological initiative by developing group auto-evaluations and co-evaluations, the students evaluating the process of effecting the group assignments or the actual completion of the final presentations. Some recommended instruments to lead the aforementioned evaluation techniques are the group class diary, the auto-evaluation reports and the evaluation scales (Hamodi et al., 2015 ; Hernando et al., 2017 ).

In short, the PBL experience carried out contains all the technical elements to facilitate a learning model of the competence type, which addresses both knowledge and skills to carry out the assignments and to offer solutions to the problems inherent to the given project, as well as the abilities to do so jointly and cooperatively. However, it shows that the methodological practice proposed still suffers from a real follow-up on the group process set, establishing feedback means in the action itself, neglecting the potential conflicts that arise and the smooth completion of the assignments.

In relation to evaluation, the importance of a more formative evaluation model is recognized among the teachers involved, appreciating practices that activate the participation and involvement of students, although the weight of the final products continues to be relevant to the process itself.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Barret T (2005) What is problem-based learning. In: O´Neill G, Moore S, McMullin B (eds) Emerging issues in the practice of university learning and teaching. AISHE, Dublin, pp. 55–66

Google Scholar

Bell S (2010) Project-based learning for the 21st century: skills for the future. Clear House 83:39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415

Article Google Scholar

Belland BR, Ertmer PA, Simons KD (2006) Perceptions of the value of problem-based learning among student with special needs and their teachers. Int J Problem-based Learn 1(2):1–18. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1024

Bender W (2012) Project-based learning: differentiating instruction for the 21st Century. Corwin, California

Blank W (1997) Authentic instruction. In: Blank WE, Harwell S (eds.) Promising practices for connecting high school to the real World. University of South Florida, Tampa, pp. 15–21

Blumenfeld PC, Soloway E, Marx R (1991) Motivating Project-based learning: sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educ Psychol 26:369–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653139

Brown S (2015) Authentic assessment: using assessment to help students learn. Electr J Educ Res Assess Eval 21(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.21.2.7674

Brown S, Race P (2013) Using effective assessment to promote learning. In: Hunt L, Chalmers D (eds.) University teaching in focus. A learning-centred approach. Routledge, London, pp. 74–91

Brundiers K, Wiek A (2013) Do we teach what we preach? An international comparative appraisal of problem- and project-based learning courses in sustainability. Sustainability 5(4):1725–1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5041725

Burdett J (2007) Degrees of separation balancing intervention and independence in group work assignments. Aust Educ Res 34(1):55–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216850

Del Canto P, Gallego I, López JM, Mora J, Reyes A, Rodríguez E, Valero M (2009) Conflictos en el trabajo en grupo: cuatro casos habituales. Revista de Formación e Innovación Educativa Universitaria 2(4):344–359

Díaz-Barriga F, Hernández R (2002) Estrategias docentes para un aprendizaje significativo. McGraw-Hill, Barcelona

Dickinson KP, Soukamneuth S, Yu HC, Kimball M, D’Amico R, Perry R, Kingsley C, Curan SP (1998) Providing educational services in the Summer Youth Employment and Training Program [Technical assistance guide]. U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Policy and Research, Washington

Dyson B (2002) The implementation of cooperative learning in an elementary school physical education program. J Teach Phys Educ 22(1):69–85

Ertmer PA, Simons KD (2005) Scaffolding teachers’ efforts to implement problem based learning. Int J Learn 12(4):319–328. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v12i04/46447

Flick U (2007) El diseño de investigación cualitativa. Morata, Madrid

Gámez MJ, Torres C (2012) Las técnicas de grupo como estrategia metodológica en la adquisición de la competencia de trabajo en equipo de los alumnos universitarios. J Educ Teach Train 4:14–25

García I, Gros B, Noguera I (2010) La relación entre las prestaciones tecnológicas y el diseño de las actividades de aprendizaje para la construcción colaborativa del conocimiento. Cultura y Educación 22(4):395–418. https://doi.org/10.1174/113564010793351867

Hamodi C, López-Pastor V, López-Pastor AT (2015) Medios, técnicas e instrumentos de evaluación formativa y compartida del aprendizaje en educación superior. Perfiles Educativos 37(147):146–161

Hernández March A (2006) Metodologías activas para la formación de competencias. Educatio Siglo XXI 24:35–56

Hernando A, Hortigüela D, Pérez-Pueyo A (2017) El proceso de evaluación formativa en la realización de un video tutorial de estiramientos en inglés en un centro bilingüe. In: López-Pastor V, Pérez-Pueyo A (eds) Buenas prácticas docentes: Evaluación formativa y compartida en educación: experiencias de éxito en todas las etapas educativas. Universidad de León, León, pp. 260–271

Jhen KA, Mannix EA (2001) The dynamic nature of conflict: a longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Acad Manag J 44(2):238–251. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3069453

Johnson D, Johnson R (1999) Aprender juntos y solos. Aprendizaje cooperative, competitivo e individualista. Aique, Buenos Aires

Johnson D, Johnson R, Holubec E (1999a) El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Paidós, Buenos Aires

Johnson D, Johnson R, Holubec E (1999b) Los círculos del aprendizaje. La cooperación en el aula y la escuela. Aique, Buenos Aires

Jonassen D (2011) Supporting problem solving in PBL. Interdiscip J Problem-Based Learn 5(2):95–119. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1256

Kagan S (2000) L´apprendimento cooperativo: L´approccio strutturale. Edizioni Lavoro, Roma

Kalpokaite N, Radivojevic I (2019) Demystifying qualitative data analysis for novice qualitative researchers. Qual Rep 24(13):44–57

Kerr NL, Bruun SE (1983) Dispensability of member effort and group motivation losses: free-rider effects. J Pers Soc Psychol 44(1):78–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.78

Kokotsaki D, Menzies V, Wiggins A (2016) Project-based learning: a review of the literature. Improving Schools 19(3):267–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480216659733

Kolmos A (2012) Changing the curriculum to problem based and project-based learning. In: Yusof KM, Azli NA, Kosnin AM, Syed Yusof SK, Yusof YM (eds) Outcome-based science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education: innovative practices. IGI Global, pp. 50–61

Krajcik JS, Blumenfeld PC (2006) Project-based learning. In: Sawyer K (ed) Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–334

Lima RM, Carvalho D, Flores M, Van Hattum-Janssen N (2007) A case study on project led education in engineering: student´s and teacher´s perceptions. Eur J Eng Educ 32(3):337–347

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage, Beverly Hills

Book Google Scholar

Martín A, Rodríguez S (2015) Motivación en alumnos de Primaria en aulas con metodologías basadas en proyectos. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación Extr 1:58–62. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2015.0.01.314

McConnell D (2005) Networked e-learning groups. Stud High Educ 30(1):25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507052000307777

Mergendoller JR, Maxwell NL, Bellisimo Y (2006) The effectiveness of problem-based instruction: a comparative study of instructional methods and student characteristics. Interdiscip J Problem-Based Learn 1(2):49–69. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1026

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J (2014) Qualitative data analysis. A methods sourcebook. Sage, London

Neal JW, Neal ZP, VanDyke E, Kornbluh M (2015) Expediting the analysis of qualitativedata in evaluation: a procedure for the rapid identification of themes fromaudio recordings (RITA). Am J Eval 36(1):118–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214014536601

Orlick T (1986) Juegos y deportes cooperativos. Editorial Popular, Madrid

Pérez-Pueyo A, López-Pastor V (2017) El estilo actitudinal como propuesta metodológica vinculada a la evaluación formativa. In: López-Pastor V, Pérez- Pueyo A (eds) Evaluación formativa y compartida en educación: experiencias de éxito en todas las etapas educativas. Universidad de León, Secretariado de Publicaciones, León, pp. 240–259

Perrenoud P (2008) Construir las competencias, ¿es darle la espalda a los saberes? Revista de Docencia Universitaria 6(11):1–8

Prince MJ, Felder M (2006) Inductive teaching and learning methods: definitions, comparisons and research bases. J Eng Educ 95(2):123–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2006.tb00884.x

Pujolàs P (2009) La calidad en los equipos de aprendizaje cooperativo. Algunas consideraciones para el cálculo del grado de cooperatividad. Revista de Educación 349:225–239

Putnam J (1997) Cooperative learning in diverse classrooms. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Sánchez N (2018) Clase invertida y aprendizaje basado en proyectos en el aula de biología. Un proyecto de innovación para 1° de la ESO. Valoración de la experiencia. Enseñanza Teaching 36(1):81–11. https://doi.org/10.14201/et21836181110

Slavin RE (2014) Cooperative learning and academic achievement: why does groupwork work? Anales de Psicología 30(3):785–791. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201201

Thomas JW (2000) A review of research in project-based learning. Autodesk Foundation, San Rafael, CA

Velázquez C (2013) La pedagogía de la cooperación en educación física. Kínesis, Armenia

Walberg H, Paik S (2002) Prácticas eficaces. Magisterio, Bogotá

Download references

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the teachers, school managers and the children that participated for their collaboration.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pedagogy, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Valladolid, Paseo de Belén, 1, 47011, Valladolid, Spain

Berta de la Torre-Neches & Mariano Rubia-Avi

Deparment of Physical Education, Faculty of Education, University of Valladolid, Plaza de la Universidad, 1, 40005, Segovia, Spain

Jose Luis Aparicio-Herguedas

Department of Methods of Research and Diagnosis in Education I, National Distance Education University, Juan del Rosal, 14, 28040, Madrid, Spain

Jairo Rodríguez-Medina

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Berta de la Torre-Neches .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

de la Torre-Neches, B., Rubia-Avi, M., Aparicio-Herguedas, J.L. et al. Project-based learning: an analysis of cooperation and evaluation as the axes of its dynamic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7 , 167 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00663-z

Download citation

Received : 22 September 2020

Accepted : 05 November 2020

Published : 08 December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00663-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 06 January 2022

The key characteristics of project-based learning: how teachers implement projects in K-12 science education

- Anette Markula 1 &

- Maija Aksela ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9552-248X 1

Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research volume 4 , Article number: 2 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

39 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

The aim of this multiple-case study was to research the key characteristics of project-based learning (PBL) and how teachers implement them within the context of science education. K-12 science teachers and their students’ videos, learning diaries and online questionnaire answers about their biology related PBL units, within the theme nature and environment, were analysed using deductive and inductive content analysis ( n = 12 schools). The studied teachers are actively engaged in PBL as the schools had participated voluntarily in the international StarT programme of LUMA Centre Finland. The results indicate that PBL may specifically promote the use of collaboration, artefacts, technological tools, problem-centredness, and certain scientific practices, such as carrying out research, presenting results, and reflection within science education. However, it appeared that driving questions, learning goals set by students, students’ questions, the integrity of the project activities, and using the projects as a means to learn central content, may be more challenging to implement. Furthermore, although scientific practices had a strong role in the projects, it could not be defined how strongly student-led the inquiries were. The study also indicated that students and teachers may pay attention to different aspects of learning that happen through PBL. The results contribute towards a deeper understanding of the possibilities and challenges related to implementation of PBL and using scientific practices in classrooms. Furthermore, the results and the constructed framework of key characteristics can be useful in promoting research-based implementation and design of PBL science education, and in teacher training related to it.

Introduction

Project-based learning (PBL) can be a useful approach for promoting twenty-first century learning and skills in future-oriented K-12 science education. PBL refers to problem-oriented and student-centred learning that is organised around projects (Thomas, 2000 ). This means that the intended learning of new skills and content happens through the project that students carry out in groups (Condliffe et al., 2017 ; Parker et al., 2013 ; Thomas 2000 ). Thus , PBL can be described as a collaborative inquiry-based teaching method where students are integrating, applying and constructing their knowledge as they work together to create solutions to complex problems (Guo et al., 2020 ). It is important that students practice working like this at school, as future generations will need to be able to overcome global environmental problems. As such, science education has to equip students with deeper learning instead of simple memorising of facts; students need the ability to apply their scientific knowledge in situations requiring problem-solving and decision-making (Miller & Krajcik, 2019 ).

PBL relies on four significant ideas from learning sciences: learning is most effective when students (1) construct their understanding actively and (2) work collaboratively in (3) authentic learning environments, whilst being sufficiently scaffolded with (4) cognitive tools (Krajcik & Shin, 2014 ). Compared to traditional teacher-led instruction, PBL has been found to result in greater academic achievement (Chen & Yang, 2019 ; Balemen & Özer Keskin, 2018 ). Additionally, it has been shown to improve students’ skills in critical thinking and question-posing (Sasson et al., 2018 ). There is also some evidence that PBL might contribute to developing students’ intra- and interpersonal competencies (Kaldi et al., 2011 ).

Within science and technology education, one of the key benefits of PBL is arguably immersing students in using scientific practices, such as asking questions (Novak & Krajcik, 2020 ). Whilst various approaches can be taken to PBL, scientific practices are often considered as one of its key characteristics (see Table 1 for discussion about the key characteristics of PBL). The idea is that in PBL, students should participate in authentic research in which they use and construct their knowledge like scientists would (Novak & Krajcik, 2020 ). Using scientific practices has been found to contribute towards students’ engagement when learning science (Lavonen et al., 2017 ), and PBL does indeed appear to have a positive impact on students’ attitudes and motivation towards science and technology (Kortam et al., 2018 ; Hasni et al., 2016 ). PBL allows students to see and appreciate the connection between scientific practices and the real world, significance of learning, carrying out investigations and the open-endedness of the problems under investigation (Hasni et al., 2016 ).

Nevertheless, according to the review done by Condliffe et al. ( 2017 ), the efficacy of PBL in terms of student outcomes is not entirely clear. In a more recent review, however, Chen & Yang ( 2019 ) found more distinctive benefits to learning compared to previous studies. As they suggest, it may be that implementation of PBL has developed between 2000 and 2010, potentially owing to the better availability of training programmes and materials. Nonetheless, whilst Chen & Yang ( 2019 ) did find that PBL improves students’ academic achievement in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), they also found that the positive effect of PBL appeared to be somewhat bigger in social sciences compared to STEM subjects. Additionally, the various distinctions between different researchers for what makes PBL different from other closely related instructional approaches, such as inquiry-based and problem-based learning, make it challenging to confidently determine exactly how effective PBL is as an instructional method (Condliffe et al., 2017 ).

However, PBL is supported by governments, researchers, and teachers in many countries (Novak & Krajcik, 2020 ; Condliffe et al., 2017 ; Aksela & Haatainen, 2019 ; Annetta et al., 2019 ; Hasni et al., 2016 ) . Studies have found that teachers consider PBL as an approach that promotes both students’ and teachers’ learning and motivation, collaboration and a sense of community at school level, student-centred learning, connects theory with practice and brings versatility to teachers’ instruction (Viro et al., 2020 ; Aksela & Haatainen, 2019 ). However, regardless of teachers’ enthusiasm towards PBL, they can still struggle with its implementation (Tamim & Grant, 2013 ). PBL is a challenging method to use in practice, as it requires a fundamental understanding of its pedagogical foundations (Han et al., 2015 ), and it appears that teachers tend to have limited and differing conceptions about PBL (Hasni et al., 2016 ). For example, PBL is often defined through its distinct characteristics (Hasni et al., 2016 ; Thomas, 2000 ), but these tend to be unknown to teachers (Tamim & Grant, 2013 ). What is more, research has indicated that in order for PBL to be implemented as it is described by researchers, teachers require training and multiple years of practice with it (Mentzer et al., 2017 ). In fact, students display greater learning gains when their teacher is experienced with PBL (Capraro et al., 2016 ; Han et al., 2015 ), and it appears that partial or incorrect implementation of PBL may even have negative consequences for students’ academic performance (Capraro et al., 2016 ; Erdoğan et al., 2016 ).

Both Viro et al. ( 2020 ) and Aksela & Haatainen ( 2019 ) found that according to STEM teachers, the most challenging aspects of implementing PBL are project organisation (for example, time management), technical issues, resources, student-related challenges and collaboration (Viro et al., 2020 ; Aksela & Haatainen, 2019 ). As PBL requires students to study a certain phenomenon in detail by using scientific practices, it takes longer than more traditional approaches (Novak & Krajcik, 2020 ). Researchers have also reported that teachers consider irrelevance to subject teaching and an unfamiliar teaching style among the significant negative aspects of PBL (Viro et al., 2020 ). Implementation of PBL should focus on teaching twenty-first century skills, being student-centred, and building strong and personal interaction between students and teachers (Morrison et al., 2020 ). This requires both teachers and students to take on new roles. In PBL, teachers are often having to act simultaneously as designers, champions, facilitators and managers, and students are expected to be self-directed learners who are able to endure the ambiguity and open-endedness of PBL projects (Pan et al., 2020 ).

Despite the move towards student-centred approaches (for example, inquiry-based teaching) in many national curricula, such as in the United States (National Research Council, 2012 ), Finland (Lähdemäki, 2019 ) and throughout much of Europe (European Commission, 2007 ), there is a distinct lack of research about PBL that is initiated by teachers (Condliffe et al., 2017 ). There is very little research into how teachers understand and use PBL when they are not guided by university researchers, and the models they develop for its implementation (Hasni et al., 2016 ). It is also important to research what kinds of changes teachers make to PBL curricula to adapt them to their classes, and how this process could be supported (Condliffe et al., 2017 ). Often the reality in classrooms differs from the visions in curricula (Abd-El-Khalick et al., 2004 ), and simply reforming the science curricula does not mean that teachers understand how to implement the new concepts into their teaching (Severance & Krajcik, 2018 ). In order to gain a better understanding of how teachers implement PBL and the related possibilities and challenges in practice, and to promote the use of PBL in education, PBL units from K-12 schools were studied from the perspective of key characteristics of PBL. The studied schools were from several different countries and they all had participated in the international StarT programme ( https://start.luma.fi/en/ ) by LUMA Centre Finland (see ‘Participants’).

Key characteristics of PBL

Most projects done at schools are not considered to be PBL, as PBL is often defined more specifically through its distinct characteristics (Hasni et al., 2016 ; Thomas, 2000 ), also referred to as ‘design principles’ (Condliffe et al., 2017 ). However, there is still ambiguity among researchers about what the exact key characteristics or design principles of PBL are (Condliffe et al., 2017 ; Hasni et al., 2016 ). Krajcik & Shin ( 2014 ) propose the following six features as key characteristics of PBL: (1) driving question, (2) learning goals, (3) scientific practices, (4) collaboration, (5) using technological tools, and (6) creating an artefact. These characteristics, including their purpose and features, have been discussed based on the literature review in Table 1 .

In this study, the PBL units were researched by using the six key characteristics found in Table 1 as a framework (Krajcik & Shin, 2014 ). The categories in the content analysis (see Table 2 in ‘Methods’) were based on these characteristics. At the time of doing the analysis, the model proposed by Krajcik & Shin ( 2014 ) was the most recent and detailed description of the characteristics of PBL that allowed study into the quality of the PBL units in practice. Additionally, their framework is in line with the views of other authors who focused on the characteristics of PBL, including the recent systematic review by Hasni et al. ( 2016 ) into the characteristics of STEM PBL used by researchers, and with the reviews done by for example, Condliffe et al. ( 2017 ) and Thomas ( 2000 ). However, in order to study the quality of PBL units under each of the characteristics, the framework was developed further by using the most current literature. For example, the phases of inquiry-based learning (Pedaste et al., 2015 ) were used to study how scientific practices were carried out by the schools.

Most earlier science education studies have looked at teachers’ perceptions of PBL through questionnaires and interviews (Hasni et al., 2016 ), but this study analysed teachers and students’ reports of their projects in practice. Considering the widely recognised challenges in the implementation of PBL, and the shift in many national curricula towards PBL and similar approaches, there is an urgent need to understand how teachers are managing the change, and what kinds of models they are developing for the implementation of the new curricula in their classrooms. The aim of this study is to understand possibilities and challenges related to the implementation of PBL in practice through the key characteristics (Table 1 ). The detailed research questions are: (1) Which key characteristics of PBL do teachers implement in the projects? and (2) How do teachers implement these characteristics in practice?

This study was carried out as a multiple-case study (Yin, 2014 ) on schools that participated in the international StarT programme by LUMA Centre Finland from different countries. A multiple case study allows for comparison between the differences and similarities between the cases (Yin, 2014 ), and therefore to gain a preliminary idea of characteristics or issues that might be common across the schools. The PBL units of twelve K-12 schools were studied (see ‘Participants’ for further details on the selection criteria). The schools participated in the international StarT competition organised by LUMA Centre Finland ( https://start.luma.fi/en/ ) during the academic year of 2016–17 or 2017–18.

The StarT programme

StarT encourages teachers to share their best models for implementing PBL, and students to present the products and research they have done within their groups (StarT programme). The competition has two categories: teachers’ descriptions of the PBL units that were carried out by the schools (‘ best practices’ ), and ‘ students’ projects ’ that describe what individual student groups studied, created and learned during the school’s PBL unit. Each school was able to upload one entry to the teachers’ category, describing the implementation of the project unit from teachers’ perspective as a best practice for other schools, and an unlimited number of students’ projects related to this unit. As such, each ‘ student project ’ is part of the same PBL unit organised by the school, but it describes what one student group produced under the PBL unit implemented by the teachers. Depending on the school and how much freedom the students had in the PBL unit, the student groups might have had completely different research topics, or they might have just produced slightly different artefacts to the same problem.

To participate in each category, the schools needed to upload a three-minute-long video describing the best practice or the project and to answer questions on an online form. Additionally, student groups were required to upload a learning diary, the format of which could be freely chosen. As such, the schools had significant freedom in terms of what they wanted to report about their PBL units. At the time of the data collection, the participants did not receive any professional development training from StarT, but depending on how closely they followed the online channels of StarT, they had access to project ideas and videos from other participants via the programme website, and the programme also included voluntary webinars and newsletters. However, these materials were freely available to anyone on the internet, and participating in the competition did not require any other engagement with the StarT programme.

Content analysis

Deductive content analysis is suitable for research that aims to study an existing model or theory (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005 ). The key characteristics of PBL shown in Table 1 were used as a basis for the deductive and inductive content analysis, where it was determined which characteristics teachers implemented in the projects, and how they did this. In qualitative content analysis, data is analysed by reducing it to concepts that describe the studied phenomenon, for example, through pre-defined categories, whilst also acknowledging the themes rising from the data (Elo et al., 2014 ; Cohen et al., 2007 ). The final categories used in the deductive analysis, and discussion about decisions regarding them, can be seen in Table 2 . The data was looked at inductively within these categories (Marshall & Rossman, 2014 ). An example of the coding combining inductive and deductive content analysis is given in Table 3 .

The analysed materials ( n = 12 project units and n = 17 students’ projects; see details under ‘Participants’ and in Table 5 ) were written responses to questions on an online form, videos and learning diaries. The units considered in the analysis were words, sentences, and paragraphs from verbal communication. As the students’ projects were what individual student groups produced within the PBL unit of the school, all of the materials provided by an individual school were considered as an entity when studying how the school carried out PBL. Therefore, there was no differentiation between the source of the information (for example, learning diary or best practice video) but instead all materials from a single school were treated as equal evidence of how the characteristics of PBL were implemented (see Table 3 ). However, since two schools provided multiple student groups’ works as student projects, and there were differences in the approaches that different student groups took to carrying out their project work, also the number of student projects displaying each of the key characteristics is included in Table 6 under ‘Results’.

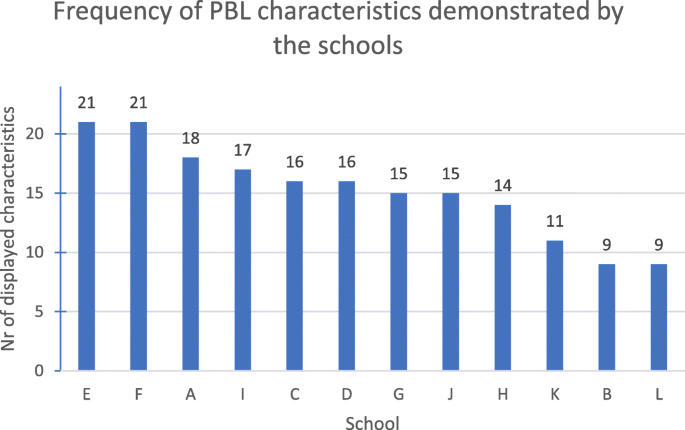

In order to see how the six key characteristics of PBL were distributed across the projects, the overall frequencies of characteristics displayed in a project unit (1 = present, 0 = not present) were counted. Table 4 displays the sections from the coding framework that were included in the frequency count. Each row in the second column was counted as ‘1’ if it was observed and as ‘0’ if it was not. Including these features in the frequency count allows a satisfactory picture of the distribution of the key characteristics across the studied schools to be drawn (See Fig. 1 and Table 6 ). Scientific practices are emphasised in the count due to their many subcategories, but this was deemed appropriate since they are a good indication of how inquiry-based and student-led the projects were. Learning goals and gains have a significant role too, but their role is similarly justified by their importance – they determine largely whether the projects have resulted in their intended purpose, learning. The results regarding the implementation and distribution of the key characteristics can be found under ‘Results’.

In order to improve the reliability and validity of the study, triangulation was employed (Turner et al., 2017 ) through the use of different types of materials as sources of information. This increases the reliability of studies looking at human behaviour (Cohen et al., 2007 ) and case studies (Yin, 2014 ), as that allows cues from different sources to be combined into a more representative image of a case (Baxter & Jack, 2008 ). Firstly, the materials consisted of three different types of media: written descriptions and answers to questions on an online form, videos, and a learning diary, the medium of which was not pre-defined for the participants. Secondly, the studied schools only consisted of learning communities that had participated in both the teacher category of StarT with a ‘best practice’ (a description of the PBL unit from teachers’ point of view) and the student category with at least one ‘student project’ (description of the work one student group did during the PBL unit). As such, this study includes the viewpoints of both teachers and students. Additionally, the results from coding were agreed upon by both of the authors.

Participants

The study analysed students’ projects and teachers’ best educational practices at K-12 school level ( n = 12 project units and n = 17 students’ projects; see Table 5 for details) that were implemented in 2016–2017 or 2017–2018. The projects were mostly ( n = 9) created and implemented by teachers and students, and as such they reflect the reality of schools when it comes to implementing PBL. Only n = 3 schools mentioned that they had participated in a (university-led) development programme. As such, the studied PBL units provide a plausible reflection of the reality of active teachers implementing PBL (see ‘Limitations’ for further discussion).

The studied PBL units within the theme ‘Nature and environment’ were chosen from the learning communities that participated in the international StarT programme in 2016–2017 and in 2017–2018. The other themes that the StarT participants could choose for their projects were ‘Technology around us’, ‘Mathematics around us’, ‘This works! A mobile toy’, ‘Stars and space’, ‘Well-being’, ‘Home, culture and internationality’. ‘Nature and environment’ was the most popular single theme during both years of data collection: n = 132 learning communities from all n = 277 learning communities indicated that they had done a project related to it in 2016–2017, and n = 50 out of n = 229 in 2017–2018. Whilst the studied projects focus on the theme ‘nature and environment’ in the context of biology education, the interdisciplinary nature of the theme makes the results largely applicable for other sciences. The decision to base the study on a single discipline was made in order to gain a more detailed understanding of the implications of STEM PBL for subject teaching; the case in this study focusing on teaching biology through PBL.

The first criteria in selecting the cases for this study was to include only PBL units implemented by K-12 school (ages 7 to 18). Additionally, only projects themed ‘Nature and environment’, where biology had a clear role, were included. Finally, only schools that had provided full sets of materials used in the analysis (written responses, videos and learning diaries) were included. Full sets of materials were required for both teachers’ descriptions of the PBL unit and students’ projects, either in English or Finnish (one school had to be excluded due to an insufficient level of English).

Table 5 presents participants and their school levels: 12 schools matched the criteria described above. In total, 12 project units and 17 students’ projects were analysed, with only two of the schools having provided more than one student project as a part of the project unit. 11 of the studied schools were from six different countries in Europe, and one school was from Southwest Asia. Schools D, E and F (Table 5 ) participated in the same PBL development programme implemented by a local university.

The participants gave permission for using their materials for research purposes upon their participation in StarT. However, as this study looks at the projects from an evaluative perspective, direct quotations or detailed descriptions of individual cases that could be used to identify the schools were not included.

The results for each of the research questions (see end of the chapter “Key characteristics of PBL”) will be presented separately.

(1) The key characteristics of PBL in the projects

The most frequently displayed key characteristics of PBL were collaboration, artefacts, technology, problem-centredness, and out of scientific practices, carrying out research, presenting results and reflection (see Table 6 for more detail). At least some form of collaboration (either between the students, between teachers or with outside partners) took place in all but one of the schools. Any interaction that the schools described as having taken place between different actors was considered as collaboration. Furthermore, technology was used as a part of the projects in all of the schools. Artefacts were also created in all of the studied projects. The results for each of the characteristics are summarised in Table 6 (research question 1), which also outlines how they were implemented (research question 2). As n = 2 schools provided multiple projects by different student groups, the number of projects ( n = 17) is higher than the number of schools ( n = 12).

Regarding scientific practices that students participated in, presenting results (n = 12 schools), interpreting results ( n = 11) and reflection ( n = 10) were most commonly demonstrated. However, not all schools ( n = 4) displayed clearly that students had done any research (such as searching for information, observation and collecting data). As testing hypotheses was not visible in any of the projects ( n = 0), according to the definition of Pedaste et al. ( 2015 ), the research was considered as” exploration” ( n = 8) instead of” experimentation” (n = 0). Only n = 4 schools included a mention of students having presented questions that had an impact on the course of the project or the investigations that were carried out.

Driving questions and learning goals were among the key characteristics that were not described well (Table 6 ). None of the twelve schools that were studied displayed evidence of having used a driving question in their projects. However, the majority of the schools (n = 8) did centre their projects around solving a single problem. According to PBL literature, this is not the same as having a driving question (see Table 1 for a more detailed description), but in the absence of driving questions it was considered useful to study whether the projects were at least centred around solving a single problem. Learning goals (goals with a reference to students’ development) were also not that commonly described; materials from n = 6 schools displayed learning goals set by teachers, but none of the schools displayed learning goals set by students. However, students did appear to set practical goals (goals with no reference to students’ development) in the projects from n = 3 schools, and teachers mentioned these in most schools too ( n = 9). Furthermore, students’ descriptions of what they had learnt as a result of the projects were visible in the materials of n = 10 schools, whereas teachers’ comments regarding that were only visible in those of half ( n = 6) of the schools.

Figure 1 displays the distribution of the characteristics across the project units. The highest frequency values were for the schools E and F, which both had participated in the same development programme organised by a local university. However, although they did not receive help from researchers, schools A (f = 18), I (f = 17) and C (f = 16) still displayed a reasonably high count of PBL characteristics. In fact, school C had the same frequency of PBL characteristics as school D, which was the third school to participate in the university-led development programme. Figure 1 shows that there is a clear difference between schools whose PBL units were most closely in line with the PBL framework used in this study (f = 21, n = 2) and the schools that provided project units with the least resemblance to it (f = 9, n = 2).

Frequency of the PBL characteristics demonstrated by the schools A-L ( n = 12, see Tables 4 and 5 )

(2) Implementation of the key characteristics in the projects

The main results regarding the implementation of the key characteristics are summarised in Table 6 , together with their visibility. The detailed description about the implementation of each of the key characteristics of PBL can be found below: (1) driving question, (2) learning goals, (3) scientific practices, (4) collaboration, (5) using technological tools, and (6) creating an artefact.

Using central problems instead of driving questions did not stop schools from accomplishing some of the characteristics of a good driving question. In all of the schools where the project had a central problem, the problems were related to environmental issues, which meant that they were regarded as socio-scientific issues (Sadler, 2009 ). All of these schools also used local or familiar learning environments, which is another characteristic of a good driving question. For example, they researched everyday phenomena ( n = 7 projects), used family or peers as audience ( n = 6), created an impact on the local environment (n = 6) or studied it ( n = 5). Some also visited local attractions ( n = 2) or collaborated with students’ families (n = 2).

Interestingly, teachers and students seemed to report different kinds of learning gains; students focused on learning biology ( n = 7 schools) more than teachers ( n = 3), who paid attention to progress in learning social skills ( n = 6), other twenty-first century skills ( n = 2) and scientific practices ( n = 2). Students reported these respectively in n = 4, n = 1 and n = 0 schools. Furthermore, teachers did not mention students’ personal development (for example, new perspectives and experiences), which the students themselves noted in n = 2 schools. Students also mentioned development of their environmental values more often ( n = 4 compared to teachers in n = 2 schools). ICT skills were mentioned in n = 2 schools by students and n = 1 by teachers.

When words that referred to the students’ development (for example, “develop”, “apply” or “learn”) were used in conjunction with the aims of the project, the goal was interpreted as a learning goal. However, when they were absent, the goal was interpreted as a concrete practical aim (for example, “creating an herb garden”). N = 5 projects displayed practical goals set by students, all of which were related to biology too. However, none of the goals set by students were learning goals according to the definition described above; they all focused on the practical aims of the work instead. Learning goals set by teachers included learning related to biology ( n = 5 schools), scientific practices ( n = 4), social skills ( n = 3), other twenty-first century skills ( n = 1) and technical skills ( n = 1). The learning goals related to biology could be divided into values ( n = 5 schools), content ( n = 3) and skills ( n = 1).

The materials of the study did not allow extensive assumptions about what was teachers’ and what students’ viewpoint, but in terms of learning goals, it was deemed necessary to make a distinction based on the sentence structures. If a continuous part of the text displayed students as implementers and was written in third person (for example, “in this project students are expected to …” or “their goal is to …” ), the learning was interpreted as having been set by the teacher. However, if a continuous part of the text was presented in first person and the text clearly displayed that “we” referred to students, the part of the text that described learning was interpreted as students’ viewpoint to learning.

With regards to different scientific practices, it was not possible to identify how student-led the implementation was due to lack of teachers’ and students’ comments on this. Hypotheses were not presented in any of the projects, although n = 8 projects included experiments that could have included a hypothesis. The three projects that did not show any signs of doing research and interpreting data were all from the same school and generally vaguely described; these projects did not show evidence of students drawing conclusions either. As all projects were presented to others at least through the video that was shared to StarT, all of them were considered as having presented the results of the project. However, all but one project described having done that in other ways as well, for example, by giving presentations for younger students and parents, and making posters.

Most of the projects were carried out in various learning environments and with a variety of partners. In terms of collaboration, three categories emerged: collaboration between students ( n = 11 schools), collaboration between teachers ( n = 9), and collaboration between the school and outside actors ( n = 9). Collaboration between students was mostly group work ( n = 16 projects) or presenting the work for other students ( n = 9 projects). Teachers collaborated mostly with other teachers in the same school ( n = 8 schools), and in some cases with teachers from another school ( n = 4); however, n = 3 of these schools participated in the same development programme of a local university, and this university organised the event where the collaboration happened. The materials did not provide information of how the teachers collaborated with each other or divided tasks. The outside partners were students’ parents ( n = 9), universities ( n = 5), media ( n = 5), museums ( n = 5), municipalities or other public agencies ( n = 4), local people ( n = 3), other experts ( n = 3), and organisations ( n = 2).