Uncomplicated Reviews of Educational Research Methods

- Writing a Research Report

.pdf version of this page

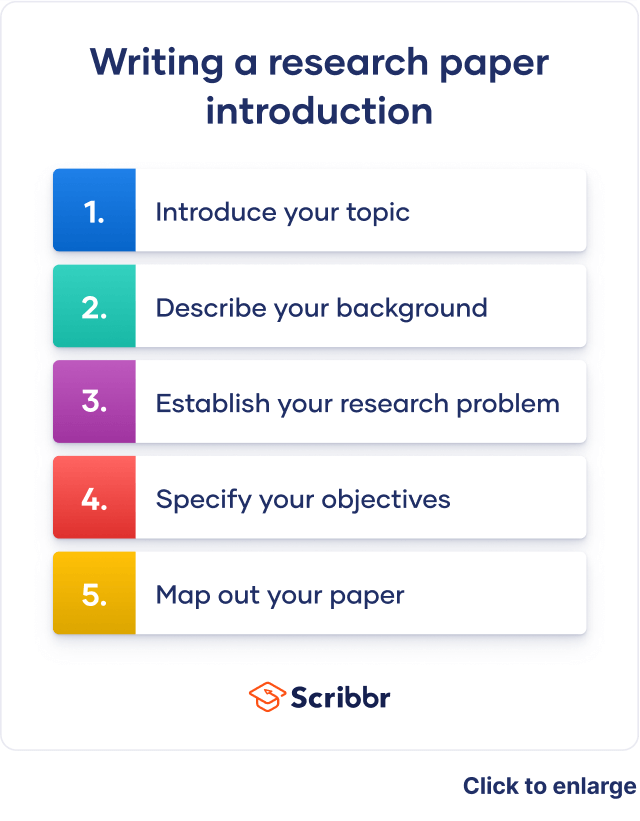

This review covers the basic elements of a research report. This is a general guide for what you will see in journal articles or dissertations. This format assumes a mixed methods study, but you can leave out either quantitative or qualitative sections if you only used a single methodology.

This review is divided into sections for easy reference. There are five MAJOR parts of a Research Report:

1. Introduction 2. Review of Literature 3. Methods 4. Results 5. Discussion

As a general guide, the Introduction, Review of Literature, and Methods should be about 1/3 of your paper, Discussion 1/3, then Results 1/3.

Section 1 : Cover Sheet (APA format cover sheet) optional, if required.

Section 2: Abstract (a basic summary of the report, including sample, treatment, design, results, and implications) (≤ 150 words) optional, if required.

Section 3 : Introduction (1-3 paragraphs) • Basic introduction • Supportive statistics (can be from periodicals) • Statement of Purpose • Statement of Significance

Section 4 : Research question(s) or hypotheses • An overall research question (optional) • A quantitative-based (hypotheses) • A qualitative-based (research questions) Note: You will generally have more than one, especially if using hypotheses.

Section 5: Review of Literature ▪ Should be organized by subheadings ▪ Should adequately support your study using supporting, related, and/or refuting evidence ▪ Is a synthesis, not a collection of individual summaries

Section 6: Methods ▪ Procedure: Describe data gathering or participant recruitment, including IRB approval ▪ Sample: Describe the sample or dataset, including basic demographics ▪ Setting: Describe the setting, if applicable (generally only in qualitative designs) ▪ Treatment: If applicable, describe, in detail, how you implemented the treatment ▪ Instrument: Describe, in detail, how you implemented the instrument; Describe the reliability and validity associated with the instrument ▪ Data Analysis: Describe type of procedure (t-test, interviews, etc.) and software (if used)

Section 7: Results ▪ Restate Research Question 1 (Quantitative) ▪ Describe results ▪ Restate Research Question 2 (Qualitative) ▪ Describe results

Section 8: Discussion ▪ Restate Overall Research Question ▪ Describe how the results, when taken together, answer the overall question ▪ ***Describe how the results confirm or contrast the literature you reviewed

Section 9: Recommendations (if applicable, generally related to practice)

Section 10: Limitations ▪ Discuss, in several sentences, the limitations of this study. ▪ Research Design (overall, then info about the limitations of each separately) ▪ Sample ▪ Instrument/s ▪ Other limitations

Section 11: Conclusion (A brief closing summary)

Section 12: References (APA format)

Share this:

About research rundowns.

Research Rundowns was made possible by support from the Dewar College of Education at Valdosta State University .

- Experimental Design

- What is Educational Research?

- Writing Research Questions

- Mixed Methods Research Designs

- Qualitative Coding & Analysis

- Qualitative Research Design

- Correlation

- Effect Size

- Instrument, Validity, Reliability

- Mean & Standard Deviation

- Significance Testing (t-tests)

- Steps 1-4: Finding Research

- Steps 5-6: Analyzing & Organizing

- Steps 7-9: Citing & Writing

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Research Report: Definition, Types + [Writing Guide]

One of the reasons for carrying out research is to add to the existing body of knowledge. Therefore, when conducting research, you need to document your processes and findings in a research report.

With a research report, it is easy to outline the findings of your systematic investigation and any gaps needing further inquiry. Knowing how to create a detailed research report will prove useful when you need to conduct research.

What is a Research Report?

A research report is a well-crafted document that outlines the processes, data, and findings of a systematic investigation. It is an important document that serves as a first-hand account of the research process, and it is typically considered an objective and accurate source of information.

In many ways, a research report can be considered as a summary of the research process that clearly highlights findings, recommendations, and other important details. Reading a well-written research report should provide you with all the information you need about the core areas of the research process.

Features of a Research Report

So how do you recognize a research report when you see one? Here are some of the basic features that define a research report.

- It is a detailed presentation of research processes and findings, and it usually includes tables and graphs.

- It is written in a formal language.

- A research report is usually written in the third person.

- It is informative and based on first-hand verifiable information.

- It is formally structured with headings, sections, and bullet points.

- It always includes recommendations for future actions.

Types of Research Report

The research report is classified based on two things; nature of research and target audience.

Nature of Research

- Qualitative Research Report

This is the type of report written for qualitative research . It outlines the methods, processes, and findings of a qualitative method of systematic investigation. In educational research, a qualitative research report provides an opportunity for one to apply his or her knowledge and develop skills in planning and executing qualitative research projects.

A qualitative research report is usually descriptive in nature. Hence, in addition to presenting details of the research process, you must also create a descriptive narrative of the information.

- Quantitative Research Report

A quantitative research report is a type of research report that is written for quantitative research. Quantitative research is a type of systematic investigation that pays attention to numerical or statistical values in a bid to find answers to research questions.

In this type of research report, the researcher presents quantitative data to support the research process and findings. Unlike a qualitative research report that is mainly descriptive, a quantitative research report works with numbers; that is, it is numerical in nature.

Target Audience

Also, a research report can be said to be technical or popular based on the target audience. If you’re dealing with a general audience, you would need to present a popular research report, and if you’re dealing with a specialized audience, you would submit a technical report.

- Technical Research Report

A technical research report is a detailed document that you present after carrying out industry-based research. This report is highly specialized because it provides information for a technical audience; that is, individuals with above-average knowledge in the field of study.

In a technical research report, the researcher is expected to provide specific information about the research process, including statistical analyses and sampling methods. Also, the use of language is highly specialized and filled with jargon.

Examples of technical research reports include legal and medical research reports.

- Popular Research Report

A popular research report is one for a general audience; that is, for individuals who do not necessarily have any knowledge in the field of study. A popular research report aims to make information accessible to everyone.

It is written in very simple language, which makes it easy to understand the findings and recommendations. Examples of popular research reports are the information contained in newspapers and magazines.

Importance of a Research Report

- Knowledge Transfer: As already stated above, one of the reasons for carrying out research is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, and this is made possible with a research report. A research report serves as a means to effectively communicate the findings of a systematic investigation to all and sundry.

- Identification of Knowledge Gaps: With a research report, you’d be able to identify knowledge gaps for further inquiry. A research report shows what has been done while hinting at other areas needing systematic investigation.

- In market research, a research report would help you understand the market needs and peculiarities at a glance.

- A research report allows you to present information in a precise and concise manner.

- It is time-efficient and practical because, in a research report, you do not have to spend time detailing the findings of your research work in person. You can easily send out the report via email and have stakeholders look at it.

Guide to Writing a Research Report

A lot of detail goes into writing a research report, and getting familiar with the different requirements would help you create the ideal research report. A research report is usually broken down into multiple sections, which allows for a concise presentation of information.

Structure and Example of a Research Report

This is the title of your systematic investigation. Your title should be concise and point to the aims, objectives, and findings of a research report.

- Table of Contents

This is like a compass that makes it easier for readers to navigate the research report.

An abstract is an overview that highlights all important aspects of the research including the research method, data collection process, and research findings. Think of an abstract as a summary of your research report that presents pertinent information in a concise manner.

An abstract is always brief; typically 100-150 words and goes straight to the point. The focus of your research abstract should be the 5Ws and 1H format – What, Where, Why, When, Who and How.

- Introduction

Here, the researcher highlights the aims and objectives of the systematic investigation as well as the problem which the systematic investigation sets out to solve. When writing the report introduction, it is also essential to indicate whether the purposes of the research were achieved or would require more work.

In the introduction section, the researcher specifies the research problem and also outlines the significance of the systematic investigation. Also, the researcher is expected to outline any jargons and terminologies that are contained in the research.

- Literature Review

A literature review is a written survey of existing knowledge in the field of study. In other words, it is the section where you provide an overview and analysis of different research works that are relevant to your systematic investigation.

It highlights existing research knowledge and areas needing further investigation, which your research has sought to fill. At this stage, you can also hint at your research hypothesis and its possible implications for the existing body of knowledge in your field of study.

- An Account of Investigation

This is a detailed account of the research process, including the methodology, sample, and research subjects. Here, you are expected to provide in-depth information on the research process including the data collection and analysis procedures.

In a quantitative research report, you’d need to provide information surveys, questionnaires and other quantitative data collection methods used in your research. In a qualitative research report, you are expected to describe the qualitative data collection methods used in your research including interviews and focus groups.

In this section, you are expected to present the results of the systematic investigation.

This section further explains the findings of the research, earlier outlined. Here, you are expected to present a justification for each outcome and show whether the results are in line with your hypotheses or if other research studies have come up with similar results.

- Conclusions

This is a summary of all the information in the report. It also outlines the significance of the entire study.

- References and Appendices

This section contains a list of all the primary and secondary research sources.

Tips for Writing a Research Report

- Define the Context for the Report

As is obtainable when writing an essay, defining the context for your research report would help you create a detailed yet concise document. This is why you need to create an outline before writing so that you do not miss out on anything.

- Define your Audience

Writing with your audience in mind is essential as it determines the tone of the report. If you’re writing for a general audience, you would want to present the information in a simple and relatable manner. For a specialized audience, you would need to make use of technical and field-specific terms.

- Include Significant Findings

The idea of a research report is to present some sort of abridged version of your systematic investigation. In your report, you should exclude irrelevant information while highlighting only important data and findings.

- Include Illustrations

Your research report should include illustrations and other visual representations of your data. Graphs, pie charts, and relevant images lend additional credibility to your systematic investigation.

- Choose the Right Title

A good research report title is brief, precise, and contains keywords from your research. It should provide a clear idea of your systematic investigation so that readers can grasp the entire focus of your research from the title.

- Proofread the Report

Before publishing the document, ensure that you give it a second look to authenticate the information. If you can, get someone else to go through the report, too, and you can also run it through proofreading and editing software.

How to Gather Research Data for Your Report

- Understand the Problem

Every research aims at solving a specific problem or set of problems, and this should be at the back of your mind when writing your research report. Understanding the problem would help you to filter the information you have and include only important data in your report.

- Know what your report seeks to achieve

This is somewhat similar to the point above because, in some way, the aim of your research report is intertwined with the objectives of your systematic investigation. Identifying the primary purpose of writing a research report would help you to identify and present the required information accordingly.

- Identify your audience

Knowing your target audience plays a crucial role in data collection for a research report. If your research report is specifically for an organization, you would want to present industry-specific information or show how the research findings are relevant to the work that the company does.

- Create Surveys/Questionnaires

A survey is a research method that is used to gather data from a specific group of people through a set of questions. It can be either quantitative or qualitative.

A survey is usually made up of structured questions, and it can be administered online or offline. However, an online survey is a more effective method of research data collection because it helps you save time and gather data with ease.

You can seamlessly create an online questionnaire for your research on Formplus . With the multiple sharing options available in the builder, you would be able to administer your survey to respondents in little or no time.

Formplus also has a report summary too l that you can use to create custom visual reports for your research.

Step-by-step guide on how to create an online questionnaire using Formplus

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create different online questionnaires for your research by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on Create new form to begin.

- Edit Form Title : Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Research Questionnaire.”

- Edit Form : Click on the edit icon to edit the form.

- Add Fields : Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for questionnaires in the Formplus builder.

- Edit fields

- Click on “Save”

- Form Customization: With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options: Formplus offers various form-sharing options, which enables you to share your questionnaire with respondents easily. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages. You can also send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Always remember that a research report is just as important as the actual systematic investigation because it plays a vital role in communicating research findings to everyone else. This is why you must take care to create a concise document summarizing the process of conducting any research.

In this article, we’ve outlined essential tips to help you create a research report. When writing your report, you should always have the audience at the back of your mind, as this would set the tone for the document.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- ethnographic research survey

- research report

- research report survey

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Ethnographic Research: Types, Methods + [Question Examples]

Simple guide on ethnographic research, it types, methods, examples and advantages. Also highlights how to conduct an ethnographic...

Assessment Tools: Types, Examples & Importance

In this article, you’ll learn about different assessment tools to help you evaluate performance in various contexts

21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2022

In this article, we will discuss a number of chrome extensions you can use to make your research process even seamless

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Research reports

This resource will help you identify the common elements and basic format of a research report.

Research reports generally follow a similar structure and have common elements, each with a particular purpose. Learn more about each of these elements below.

Common elements of reports

Your title should be brief, topic-specific, and informative, clearly indicating the purpose and scope of your study. Include key words in your title so that search engines can easily access your work. For example: Measurement of water around Station Pier.

An abstract is a concise summary that helps readers to quickly assess the content and direction of your paper. It should be brief, written in a single paragraph and cover: the scope and purpose of your report; an overview of methodology; a summary of the main findings or results; principal conclusions or significance of the findings; and recommendations made.

The information in the abstract must be presented in the same order as it is in your report. The abstract is usually written last when you have developed your arguments and synthesised the results.

The introduction creates the context for your research. It should provide sufficient background to allow the reader to understand and evaluate your study without needing to refer to previous publications. After reading the introduction your reader should understand exactly what your research is about, what you plan to do, why you are undertaking this research and which methods you have used. Introductions generally include:

- The rationale for the present study. Why are you interested in this topic? Why is this topic worth investigating?

- Key terms and definitions.

- An outline of the research questions and hypotheses; the assumptions or propositions that your research will test.

Not all research reports have a separate literature review section. In shorter research reports, the review is usually part of the Introduction.

A literature review is a critical survey of recent relevant research in a particular field. The review should be a selection of carefully organised, focused and relevant literature that develops a narrative ‘story’ about your topic. Your review should answer key questions about the literature:

- What is the current state of knowledge on the topic?

- What differences in approaches / methodologies are there?

- Where are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

- What further research is needed? The review may identify a gap in the literature which provides a rationale for your study and supports your research questions and methodology.

The review is not just a summary of all you have read. Rather, it must develop an argument or a point of view that supports your chosen methodology and research questions.

The purpose of this section is to detail how you conducted your research so that others can understand and replicate your approach.

You need to briefly describe the subjects (if appropriate), any equipment or materials used and the approach taken. If the research method or method of data analysis is commonly used within your field of study, then simply reference the procedure. If, however, your methods are new or controversial then you need to describe them in more detail and provide a rationale for your approach. The methodology is written in the past tense and should be as concise as possible.

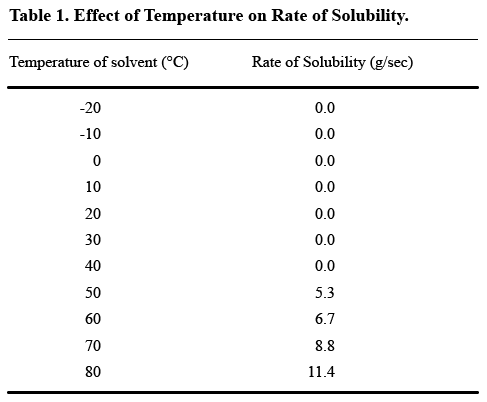

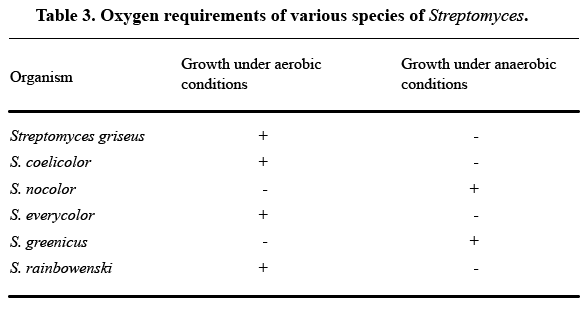

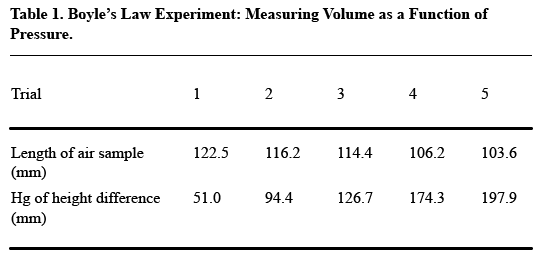

This section is a concise, factual summary of your findings, listed under headings appropriate to your research questions. It’s common to use tables and graphics. Raw data or details about the method of statistical analysis used should be included in the Appendices.

Present your results in a consistent manner. For example, if you present the first group of results as percentages, it will be confusing for the reader and difficult to make comparisons of data if later results are presented as fractions or as decimal values.

In general, you won’t discuss your results here. Any analysis of your results usually occurs in the Discussion section.

Notes on visual data representation:

- Graphs and tables may be used to reveal trends in your data, but they must be explained and referred to in adjacent accompanying text.

- Figures and tables do not simply repeat information given in the text: they summarise, amplify or complement it.

- Graphs are always referred to as ‘Figures’, and both axes must be clearly labelled.

- Tables must be numbered, and they must be able to stand-alone or make sense without your reader needing to read all of the accompanying text.

The Discussion responds to the hypothesis or research question. This section is where you interpret your results, account for your findings and explain their significance within the context of other research. Consider the adequacy of your sampling techniques, the scope and long-term implications of your study, any problems with data collection or analysis and any assumptions on which your study was based. This is also the place to discuss any disappointing results and address limitations.

Checklist for the discussion

- To what extent was each hypothesis supported?

- To what extent are your findings validated or supported by other research?

- Were there unexpected variables that affected your results?

- On reflection, was your research method appropriate?

- Can you account for any differences between your results and other studies?

Conclusions in research reports are generally fairly short and should follow on naturally from points raised in the Discussion. In this section you should discuss the significance of your findings. To what extent and in what ways are your findings useful or conclusive? Is further research required? If so, based on your research experience, what suggestions could you make about improvements to the scope or methodology of future studies?

Also, consider the practical implications of your results and any recommendations you could make. For example, if your research is on reading strategies in the primary school classroom, what are the implications of your results for the classroom teacher? What recommendations could you make for teachers?

A Reference List contains all the resources you have cited in your work, while a Bibliography is a wider list containing all the resources you have consulted (but not necessarily cited) in the preparation of your work. It is important to check which of these is required, and the preferred format, style of references and presentation requirements of your own department.

Appendices (singular ‘Appendix’) provide supporting material to your project. Examples of such materials include:

- Relevant letters to participants and organisations (e.g. regarding the ethics or conduct of the project).

- Background reports.

- Detailed calculations.

Different types of data are presented in separate appendices. Each appendix must be titled, labelled with a number or letter, and referred to in the body of the report.

Appendices are placed at the end of a report, and the contents are generally not included in the word count.

Fi nal ti p

While there are many common elements to research reports, it’s always best to double check the exact requirements for your task. You may find that you don’t need some sections, can combine others or have specific requirements about referencing, formatting or word limits.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Reports: Definition and How to Write Them

Reports are usually spread across a vast horizon of topics but are focused on communicating information about a particular topic and a niche target market. The primary motive of research reports is to convey integral details about a study for marketers to consider while designing new strategies.

Certain events, facts, and other information based on incidents need to be relayed to the people in charge, and creating research reports is the most effective communication tool. Ideal research reports are extremely accurate in the offered information with a clear objective and conclusion. These reports should have a clean and structured format to relay information effectively.

What are Research Reports?

Research reports are recorded data prepared by researchers or statisticians after analyzing the information gathered by conducting organized research, typically in the form of surveys or qualitative methods .

A research report is a reliable source to recount details about a conducted research. It is most often considered to be a true testimony of all the work done to garner specificities of research.

The various sections of a research report are:

- Background/Introduction

- Implemented Methods

- Results based on Analysis

- Deliberation

Learn more: Quantitative Research

Components of Research Reports

Research is imperative for launching a new product/service or a new feature. The markets today are extremely volatile and competitive due to new entrants every day who may or may not provide effective products. An organization needs to make the right decisions at the right time to be relevant in such a market with updated products that suffice customer demands.

The details of a research report may change with the purpose of research but the main components of a report will remain constant. The research approach of the market researcher also influences the style of writing reports. Here are seven main components of a productive research report:

- Research Report Summary: The entire objective along with the overview of research are to be included in a summary which is a couple of paragraphs in length. All the multiple components of the research are explained in brief under the report summary. It should be interesting enough to capture all the key elements of the report.

- Research Introduction: There always is a primary goal that the researcher is trying to achieve through a report. In the introduction section, he/she can cover answers related to this goal and establish a thesis which will be included to strive and answer it in detail. This section should answer an integral question: “What is the current situation of the goal?”. After the research design was conducted, did the organization conclude the goal successfully or they are still a work in progress – provide such details in the introduction part of the research report.

- Research Methodology: This is the most important section of the report where all the important information lies. The readers can gain data for the topic along with analyzing the quality of provided content and the research can also be approved by other market researchers . Thus, this section needs to be highly informative with each aspect of research discussed in detail. Information needs to be expressed in chronological order according to its priority and importance. Researchers should include references in case they gained information from existing techniques.

- Research Results: A short description of the results along with calculations conducted to achieve the goal will form this section of results. Usually, the exposition after data analysis is carried out in the discussion part of the report.

Learn more: Quantitative Data

- Research Discussion: The results are discussed in extreme detail in this section along with a comparative analysis of reports that could probably exist in the same domain. Any abnormality uncovered during research will be deliberated in the discussion section. While writing research reports, the researcher will have to connect the dots on how the results will be applicable in the real world.

- Research References and Conclusion: Conclude all the research findings along with mentioning each and every author, article or any content piece from where references were taken.

Learn more: Qualitative Observation

15 Tips for Writing Research Reports

Writing research reports in the manner can lead to all the efforts going down the drain. Here are 15 tips for writing impactful research reports:

- Prepare the context before starting to write and start from the basics: This was always taught to us in school – be well-prepared before taking a plunge into new topics. The order of survey questions might not be the ideal or most effective order for writing research reports. The idea is to start with a broader topic and work towards a more specific one and focus on a conclusion or support, which a research should support with the facts. The most difficult thing to do in reporting, without a doubt is to start. Start with the title, the introduction, then document the first discoveries and continue from that. Once the marketers have the information well documented, they can write a general conclusion.

- Keep the target audience in mind while selecting a format that is clear, logical and obvious to them: Will the research reports be presented to decision makers or other researchers? What are the general perceptions around that topic? This requires more care and diligence. A researcher will need a significant amount of information to start writing the research report. Be consistent with the wording, the numbering of the annexes and so on. Follow the approved format of the company for the delivery of research reports and demonstrate the integrity of the project with the objectives of the company.

- Have a clear research objective: A researcher should read the entire proposal again, and make sure that the data they provide contributes to the objectives that were raised from the beginning. Remember that speculations are for conversations, not for research reports, if a researcher speculates, they directly question their own research.

- Establish a working model: Each study must have an internal logic, which will have to be established in the report and in the evidence. The researchers’ worst nightmare is to be required to write research reports and realize that key questions were not included.

Learn more: Quantitative Observation

- Gather all the information about the research topic. Who are the competitors of our customers? Talk to other researchers who have studied the subject of research, know the language of the industry. Misuse of the terms can discourage the readers of research reports from reading further.

- Read aloud while writing. While reading the report, if the researcher hears something inappropriate, for example, if they stumble over the words when reading them, surely the reader will too. If the researcher can’t put an idea in a single sentence, then it is very long and they must change it so that the idea is clear to everyone.

- Check grammar and spelling. Without a doubt, good practices help to understand the report. Use verbs in the present tense. Consider using the present tense, which makes the results sound more immediate. Find new words and other ways of saying things. Have fun with the language whenever possible.

- Discuss only the discoveries that are significant. If some data are not really significant, do not mention them. Remember that not everything is truly important or essential within research reports.

Learn more: Qualitative Data

- Try and stick to the survey questions. For example, do not say that the people surveyed “were worried” about an research issue , when there are different degrees of concern.

- The graphs must be clear enough so that they understand themselves. Do not let graphs lead the reader to make mistakes: give them a title, include the indications, the size of the sample, and the correct wording of the question.

- Be clear with messages. A researcher should always write every section of the report with an accuracy of details and language.

- Be creative with titles – Particularly in segmentation studies choose names “that give life to research”. Such names can survive for a long time after the initial investigation.

- Create an effective conclusion: The conclusion in the research reports is the most difficult to write, but it is an incredible opportunity to excel. Make a precise summary. Sometimes it helps to start the conclusion with something specific, then it describes the most important part of the study, and finally, it provides the implications of the conclusions.

- Get a couple more pair of eyes to read the report. Writers have trouble detecting their own mistakes. But they are responsible for what is presented. Ensure it has been approved by colleagues or friends before sending the find draft out.

Learn more: Market Research and Analysis

MORE LIKE THIS

Exploring Types of Correlation for Patterns and Relationship

Jun 10, 2024

Life@QuestionPro: The Journey of Kristie Lawrence

Jun 7, 2024

How Can I Help You? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jun 5, 2024

Why Multilingual 360 Feedback Surveys Provide Better Insights

Jun 3, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Section 1- Evidence-based practice (EBP)

Chapter 6: Components of a Research Report

Components of a research report.

Partido, B.B.

Elements of research report

| Introduction | What is the issue? |

| Methods | What methods have been used to investigate the issue? |

| Results | What was found? |

| Discussion | What are the implications of the findings? |

The research report contains four main areas:

- Introduction – What is the issue? What is known? What is not known? What are you trying to find out? This sections ends with the purpose and specific aims of the study.

- Methods – The recipe for the study. If someone wanted to perform the same study, what information would they need? How will you answer your research question? This part usually contains subheadings: Participants, Instruments, Procedures, Data Analysis,

- Results – What was found? This is organized by specific aims and provides the results of the statistical analysis.

- Discussion – How do the results fit in with the existing literature? What were the limitations and areas of future research?

Formalized Curiosity for Knowledge and Innovation Copyright © by partido1. All Rights Reserved.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Research Paper Structure: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

Writing a research paper is a daunting task, but understanding its structure can make the process more manageable and lead to a well-organized, coherent paper. This article provides a step-by-step approach to crafting a research paper, ensuring your work is not only informative but also structured for maximum impact.

Introduction

In any form of written communication, content structure plays a vital role in facilitating understanding. A well-structured research paper provides a framework that guides readers through the content, ensuring they grasp the main points efficiently. Without a clear structure, readers may become lost or confused, leading to a loss of interest and a failure to comprehend the intended message.

When it comes to research papers, structure is particularly important due to the complexity of the subject matter. Research papers often involve presenting and analyzing large amounts of data, theories, and arguments. Without a well-defined structure, readers may struggle to navigate through this information overload, resulting in a fragmented understanding of the topic.

How Structure Enhances Clarity and Coherence

A well-structured research paper not only helps readers follow the flow of ideas but also enhances the clarity and coherence of the content. By organizing information into sections, paragraphs, and sentences, researchers can present their thoughts logically and systematically. This logical organization allows readers to easily connect ideas, resulting in a more coherent and engaging reading experience.

One way in which structure enhances clarity is by providing a clear roadmap for readers to follow. By dividing the research paper into sections and subsections, researchers can guide readers through the different aspects of the topic. This allows readers to anticipate the flow of information and mentally prepare themselves for the upcoming content.

In addition, a well-structured research paper ensures that each paragraph serves a specific purpose and contributes to the overall argument or analysis. By clearly defining the main idea of each paragraph and providing supporting evidence or examples, researchers can avoid confusion and ensure that their points are effectively communicated.

Moreover, a structured research paper helps researchers maintain a consistent focus throughout their writing. By organizing their thoughts and ideas, researchers can ensure that they stay on track and avoid going off on tangents. This not only improves the clarity of the paper but also helps maintain the reader's interest and engagement.

Components of a Research Paper Structure

Title and abstract: the initial impression.

The title and abstract are the first elements readers encounter when accessing a research paper. The title should be concise, informative, and capture the essence of the study. For example, a title like "Exploring the Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity in Tropical Rainforests" immediately conveys the subject matter and scope of the research. The abstract, on the other hand, provides a brief overview of the research problem, methodology, and findings, enticing readers to delve further into the paper. In a well-crafted abstract, researchers may highlight key results or implications of the study, giving readers a glimpse into the value of the research.

Introduction: Setting the Stage

The introduction serves as an invitation for readers to engage with the research paper. It should provide background information on the topic, highlight the research problem, and present the research question or thesis statement. By establishing the context and relevance of the study, the introduction piques readers' interest and prepares them for the content to follow. For instance, in a study on the impact of social media on mental health, the introduction may discuss the rise of social media platforms and the growing concerns about its effects on individuals' well-being. This contextual information helps readers understand the significance of the research and why it is worth exploring further.

Furthermore, the introduction may also outline the objectives of the study, stating what the researchers aim to achieve through their research. This helps readers understand the purpose and scope of the study, setting clear expectations for what they can expect to learn from the paper.

Literature Review: Building the Foundation

The literature review is a critical component of a research paper, as it demonstrates the researcher's understanding of existing knowledge and provides a foundation for the study. It involves reviewing and analyzing relevant scholarly articles, books, and other sources to identify gaps in research and establish the need for the current study. In a comprehensive literature review, researchers may summarize key findings from previous studies, identify areas of disagreement or controversy, and highlight the limitations of existing research.

Moreover, the literature review may also discuss theoretical frameworks or conceptual models that have been used in previous studies. By examining these frameworks, researchers can identify the theoretical underpinnings of their study and explain how their research fits within the broader academic discourse. This not only adds depth to the research paper but also helps readers understand the theoretical context in which the study is situated.

Methodology: Detailing the Process

The research design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques used in the study are described in the methodology section. It should be presented clearly and concisely, allowing readers to understand how the research was conducted and evaluated. A well-described methodology ensures the study's reliability and allows other researchers to replicate or build upon the findings.

Within the methodology section, researchers may provide a detailed description of the study population or sample, explaining how participants were selected and why they were chosen. This helps readers understand the generalizability of the findings and the extent to which they can be applied to a broader population.

In addition, researchers may also discuss any ethical considerations that were taken into account during the study. This could include obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity, and following ethical guidelines set by relevant professional organizations. By addressing these ethical concerns, researchers demonstrate their commitment to conducting research in an ethical and responsible manner.

Results: Presenting the Findings

The results section represents the study findings. Researchers should organize their results in a logical manner, using tables, graphs, and descriptive statistics to support their conclusions. The results should be presented objectively, without interpretation or analysis. For instance, for a study on the effectiveness of a new drug in treating a specific medical condition, researchers may present the percentage of patients who experienced positive outcomes, along with any statistical significance associated with the results.

In addition to presenting the main findings, researchers may also include supplementary data or sub-analyses that provide further insights into the research question. This could include subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, or additional statistical tests that help explore the robustness of the findings.

Discussion: Interpreting the Results

In the discussion section, researchers analyze and interpret the results in light of the research question or thesis statement. This is an opportunity to explore the implications of the findings, compare them with existing literature, and offer insights into the broader significance of the study. The discussion should be supported by evidence and it is advised to avoid speculation.

Researchers may also discuss the limitations of their study, acknowledging any potential biases or confounding factors that may have influenced the results. By openly addressing these limitations, researchers demonstrate their commitment to transparency and scientific rigor.

Conclusion: Wrapping It Up

The conclusion provides a concise summary of the research paper, restating the main findings and their implications. It should also reflect on the significance of the study and suggest potential avenues for future research. A well-written conclusion leaves a lasting impression on readers, highlighting the importance of the research and its potential impact. By summarizing the key takeaways from the study, researchers ensure that readers walk away with a clear understanding of the research's contribution to the field.

Tips for Organizing Your Research Paper

Starting with a strong thesis statement.

A strong and clear thesis statement serves as the backbone of your research paper. It provides focus and direction, guiding the organization of ideas and arguments throughout the paper. Take the time to craft a well-defined thesis statement that encapsulates the core message of your research.

Creating an Outline: The Blueprint of Your Paper

An outline acts as a blueprint for your research paper, ensuring a logical flow of ideas and preventing disorganization. Divide your paper into sections and subsections, noting the main points and supporting arguments for each. This will help you maintain coherence and clarity throughout the writing process.

Balancing Depth and Breadth in Your Paper

When organizing your research paper, strike a balance between delving deeply into specific points and providing a broader overview. While depth is important for thorough analysis, too much detail can overwhelm readers. Consider your target audience and their level of familiarity with the topic to determine the appropriate level of depth and breadth for your paper.

By understanding the importance of research paper structure and implementing effective organizational strategies, researchers can ensure their work is accessible, engaging, and influential. A well-structured research paper not only communicates ideas clearly but also enhances the overall impact of the study. With careful planning and attention to detail, researchers can master the art of structuring their research papers, making them a valuable contribution to their field of study.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

Writing up a Research Report

- First Online: 04 January 2024

Cite this chapter

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

466 Accesses

A research report is one big argument about how and why you came up with your conclusions. To make it a convincing argument, a typical guiding structure has developed. In the different chapters, there are distinct issues that need to be addressed to explain to the reader why your conclusions are valid. The governing principle for writing the report is full disclosure: to explain everything and ensure replicability by another researcher.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barros, L. O. (2016). The only academic phrasebook you’ll ever need . Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

Google Scholar

Field, A. (2016). An adventure in statistics. The reality enigma . SAGE.

Field, A. (2020). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE.

Früh, M., Keimer, I., & Blankenagel, M. (2019). The impact of Balanced Scorecard excellence on shareholder returns. IFZ Working Paper No. 0003/2019. https://zenodo.org/record/2571603#.YMDUafkzZaQ . Accessed: 9 June 2021.

Pearl, J., & Mackenzie, D. (2018). The book of why: The new science of cause and effect. Basic Books.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wirtschaft/IFZ, Campus Zug-Rotkreuz, Hochschule Luzern, Zug-Rotkreuz, Zug, Switzerland

Stefan Hunziker & Michael Blankenagel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Hunziker .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Hunziker, S., Blankenagel, M. (2024). Writing up a Research Report. In: Research Design in Business and Management. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42739-9_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42739-9_4

Published : 04 January 2024

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-42738-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-42739-9

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

Structure of a Research Paper

Structure of a Research Paper: IMRaD Format

I. The Title Page

- Title: Tells the reader what to expect in the paper.

- Author(s): Most papers are written by one or two primary authors. The remaining authors have reviewed the work and/or aided in study design or data analysis (International Committee of Medical Editors, 1997). Check the Instructions to Authors for the target journal for specifics about authorship.

- Keywords [according to the journal]

- Corresponding Author: Full name and affiliation for the primary contact author for persons who have questions about the research.

- Financial & Equipment Support [if needed]: Specific information about organizations, agencies, or companies that supported the research.

- Conflicts of Interest [if needed]: List and explain any conflicts of interest.

II. Abstract: “Structured abstract” has become the standard for research papers (introduction, objective, methods, results and conclusions), while reviews, case reports and other articles have non-structured abstracts. The abstract should be a summary/synopsis of the paper.

III. Introduction: The “why did you do the study”; setting the scene or laying the foundation or background for the paper.

IV. Methods: The “how did you do the study.” Describe the --

- Context and setting of the study

- Specify the study design

- Population (patients, etc. if applicable)

- Sampling strategy

- Intervention (if applicable)

- Identify the main study variables

- Data collection instruments and procedures

- Outline analysis methods

V. Results: The “what did you find” --

- Report on data collection and/or recruitment

- Participants (demographic, clinical condition, etc.)

- Present key findings with respect to the central research question

- Secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

VI. Discussion: Place for interpreting the results

- Main findings of the study

- Discuss the main results with reference to previous research

- Policy and practice implications of the results

- Strengths and limitations of the study

VII. Conclusions: [occasionally optional or not required]. Do not reiterate the data or discussion. Can state hunches, inferences or speculations. Offer perspectives for future work.

VIII. Acknowledgements: Names people who contributed to the work, but did not contribute sufficiently to earn authorship. You must have permission from any individuals mentioned in the acknowledgements sections.

IX. References: Complete citations for any articles or other materials referenced in the text of the article.

- IMRD Cheatsheet (Carnegie Mellon) pdf.

- Adewasi, D. (2021 June 14). What Is IMRaD? IMRaD Format in Simple Terms! . Scientific-editing.info.

- Nair, P.K.R., Nair, V.D. (2014). Organization of a Research Paper: The IMRAD Format. In: Scientific Writing and Communication in Agriculture and Natural Resources. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03101-9_2

- Sollaci, L. B., & Pereira, M. G. (2004). The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: a fifty-year survey. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA , 92 (3), 364–367.

- Cuschieri, S., Grech, V., & Savona-Ventura, C. (2019). WASP (Write a Scientific Paper): Structuring a scientific paper. Early human development , 128 , 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.09.011

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.