- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Origins of the Revolution

Aristocratic revolt, 1787–89.

- Events of 1789

- The new regime

- Counterrevolution, regicide, and the Reign of Terror

- The Directory and revolutionary expansion

What was the French Revolution?

Why did the french revolution happen, why did the french revolution lead to war with other nations.

- Who was Maximilien Robespierre?

- How did Maximilien Robespierre come to power?

French Revolution

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- World History Encyclopedia - French Revolution

- GlobalSecurity.org - The French Revolution 1789-1799

- The Victorian Web - French Revolution

- NSCC Libraries Pressbooks - The French Revolution

- Humanities LibreTexts - The French Revolution

- Ancient Origins - The French Revolution and Birth of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

- Alpha History - The French Revolution

- U.S. Department of State - Office of the Historian - The United States and the French Revolution

- Khan Academy - French Revolution (part 1)

- French Revolution - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- French Revolution - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The French Revolution was a period of major social upheaval that began in 1787 and ended in 1799. It sought to completely change the relationship between the rulers and those they governed and to redefine the nature of political power. It proceeded in a back-and-forth process between revolutionary and reactionary forces.

There were many reasons. The bourgeoisie —merchants, manufacturers, professionals—had gained financial power but were excluded from political power. Those who were socially beneath them had very few rights, and most were also increasingly impoverished. The monarchy was no longer viewed as divinely ordained. When the king sought to increase the tax burden on the poor and expand it to classes that had previously been exempt, revolution became all but inevitable.

King Louis XVI of France yielded to the idea of a new constitution and to the sovereignty of the people but at the same time sent emissaries to the rulers of neighbouring countries seeking their help in restoring his power. Many revolutionaries, especially the Girondins , believed that the revolution needed to spread throughout Europe to succeed. An Austro-Prussian army invaded France, and French revolutionary forces pushed outward.

How did the French Revolution succeed?

In some respects, the French Revolution did not succeed. But the ideas of representational democracy and basic property rights took hold, and it sowed the seeds of the later revolutions of 1830 and 1848 .

French Revolution , revolutionary movement that shook France between 1787 and 1799 and reached its first climax there in 1789—hence the conventional term “Revolution of 1789,” denoting the end of the ancien régime in France and serving also to distinguish that event from the later French revolutions of 1830 and 1848 .

The French Revolution had general causes common to all the revolutions of the West at the end of the 18th century and particular causes that explain why it was by far the most violent and the most universally significant of these revolutions. The first of the general causes was the social structure of the West. The feudal regime had been weakened step-by-step and had already disappeared in parts of Europe . The increasingly numerous and prosperous elite of wealthy commoners—merchants, manufacturers, and professionals, often called the bourgeoisie —aspired to political power in those countries where it did not already possess it. The peasants , many of whom owned land, had attained an improved standard of living and education and wanted to get rid of the last vestiges of feudalism so as to acquire the full rights of landowners and to be free to increase their holdings. Furthermore, from about 1730, higher standards of living had reduced the mortality rate among adults considerably. This, together with other factors, had led to an increase in the population of Europe unprecedented for several centuries: it doubled between 1715 and 1800. For France, which with 26 million inhabitants in 1789 was the most populated country of Europe, the problem was most acute .

A larger population created a greater demand for food and consumer goods. The discovery of new gold mines in Brazil had led to a general rise in prices throughout the West from about 1730, indicating a prosperous economic situation. From about 1770, this trend slackened, and economic crises, provoking alarm and even revolt, became frequent. Arguments for social reform began to be advanced. The philosophes —intellectuals whose writings inspired these arguments—were certainly influenced by 17th-century theorists such as René Descartes , Benedict de Spinoza and John Locke , but they came to very different conclusions about political, social, and economic matters. A revolution seemed necessary to apply the ideas of Montesquieu , Voltaire , or Jean-Jacques Rousseau . This Enlightenment was spread among the educated classes by the many “societies of thought” that were founded at that time: masonic lodges, agricultural societies, and reading rooms.

It is uncertain, however, whether revolution would have come without the added presence of a political crisis. Faced with the heavy expenditure that the wars of the 18th century entailed, the rulers of Europe sought to raise money by taxing the nobles and clergy, who in most countries had hitherto been exempt, To justify this, the rulers likewise invoked the arguments of advanced thinkers by adopting the role of “ enlightened despots .” This provoked reaction throughout Europe from the privileged bodies, diets. and estates. In North America this backlash caused the American Revolution , which began with the refusal to pay a tax imposed by the king of Great Britain. Monarchs tried to stop this reaction of the aristocracy , and both rulers and the privileged classes sought allies among the nonprivileged bourgeois and the peasants.

Although scholarly debate continues about the exact causes of the Revolution, the following reasons are commonly adduced: (1) the bourgeoisie resented its exclusion from political power and positions of honour; (2) the peasants were acutely aware of their situation and were less and less willing to support the anachronistic and burdensome feudal system; (3) the philosophes had been read more widely in France than anywhere else; (4) French participation in the American Revolution had driven the government to the brink of bankruptcy ; (5) France was the most populous country in Europe, and crop failures in much of the country in 1788, coming on top of a long period of economic difficulties, compounded existing restlessness; and (6) the French monarchy , no longer seen as divinely ordained , was unable to adapt to the political and societal pressures that were being exerted on it.

The Revolution took shape in France when the controller general of finances, Charles-Alexandre de Calonne , arranged the summoning of an assembly of “notables” (prelates, great noblemen, and a few representatives of the bourgeoisie) in February 1787 to propose reforms designed to eliminate the budget deficit by increasing the taxation of the privileged classes. The assembly refused to take responsibility for the reforms and suggested the calling of the Estates-General , which represented the clergy , the aristocracy , and the Third Estate (the commoners) and which had not met since 1614. The efforts made by Calonne’s successors to enforce fiscal reforms in spite of resistance by the privileged classes led to the so-called revolt of the “aristocratic bodies,” notably that of the parlements (the most important courts of justice), whose powers were curtailed by the edict of May 1788.

During the spring and summer of 1788, there was unrest among the populace in Paris , Grenoble , Dijon , Toulouse , Pau , and Rennes . The king, Louis XVI , had to yield. He reappointed reform-minded Jacques Necker as the finance minister and promised to convene the Estates-General on May 5, 1789. He also, in practice, granted freedom of the press, and France was flooded with pamphlets addressing the reconstruction of the state. The elections to the Estates-General, held between January and April 1789, coincided with further disturbances, as the harvest of 1788 had been a bad one. There were practically no exclusions from the voting; and the electors drew up cahiers de doléances , which listed their grievances and hopes. They elected 600 deputies for the Third Estate, 300 for the nobility, and 300 for the clergy.

French Revolution Essay - History

- About the French Revolution

Just before the French Revolution, the economic situation was so bad that a loaf of bread would cost a peasant a week’s worth of wages! The poor population of France was starving to death while the nobility continued to live a life of luxury. These atrocities snowballed into the French Revolution. Let us learn about it.

Suggested Videos

Introduction to french revolution.

In the year 1789, French Revolution started leading to a series of the events started by the middle class. The people had revolted against the cruel regime of the monarchy . This revolution had put forth the ideas of liberty, fraternity as well as equality .

The start of the revolution took place on the morning of 14 th July 1789 in the state of Paris with the storming of the Bastille which is a fortress prison. The Bastille stood for the repressive power of the king due to which it was hated by all. The revolt became so strong that the fortress was eventually demolished.

Causes of French Revolution

Although there were innumerable causes and reasons for the French Revolution a few have been found to be the main culprits. These causes can be divided accordingly

Social Cause

As over the old regime, the French society and institution are described much before 1789 wherein the society was divided into three estates–the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners.

The first state included the group of people who were involved in the church matters known as clergy. The second estate includes people who are highly ranked in state administration known as nobility. The first two estates enjoy all the privileges right from the birth and are even exempted from any kind of taxes to the state . The third estate comprises of big businessmen, court, lawyers, officials, artisans, peasants, servants and even landless laborer. This estate usually were the ones who must bear the taxes.

Economic Cause

The population of France had risen between 1715 and 1789 from about 23 million to 28 million. This, in turn, leads to surplus demand for food grains, further leading to lack of pace in the production cycle as relative to demand – ultimately leading to rice in price for the food grains.

Majority of the laborers who worked in the workshops didn’t see any increase in their wages. And the taxes were not lowered. This had eventually lead to a worst-case crisis leading to food grain scarcity or also known as Subsistence Crisis that occurred frequently during the old regime.

Political Cause

The long years of war had turned France into a dry land with almost no financial resources. During the year 1774, Louis XVI came into power and found nothing. In his reign, France helped the 13 American colonies to gain independence from Britain, who was their common enemy.

The state during this time was forced to increase the taxes as they had to meet the regular expense that included the cost of upholding an army, running government offices or universities and running governments.

The Legacy of French Revolution

The most important legacy of the French Revolution were its ideas of Liberty and Democratic rights which spread progressively in the 19 th century from France to the rest of Europe where the feudal system was abolished. These ideas were later adopted by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Tipu Sultan, the famous Indian revolutionary strugglers.

Solved Question for You

Question: Describe the legacy of the French Revolution for the peoples of the world during the 19 th and the 20 th centuries?

Ans: The legacy of the French Revolution for the peoples of the world during the 19 th and the 20 th centuries are as followed –

- The spread of ideas of equality, as well as democratic, brought about a huge difference from France to other European Countries. The feudalism was abolished.

- The ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity was adopted.

- The declaration of Rights of Man and Citizens allowed them the freedom of speech, equality before law and right to life.

- Women were also given rights including where they couldn’t be forced to get married against will, divorce was made legal and right to education was made compulsory to train for their jobs.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

French Revolution

One response to “about the french revolution”.

Please say what are the main reason for French revolution for 9th STD please

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 12, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens radically altered their political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as the monarchy and the feudal system. The upheaval was caused by disgust with the French aristocracy and the economic policies of King Louis XVI, who met his death by guillotine, as did his wife Marie Antoinette. Though it degenerated into a bloodbath during the Reign of Terror, the French Revolution helped to shape modern democracies by showing the power inherent in the will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution , combined with extravagant spending by King Louis XVI , had left France on the brink of bankruptcy.

Not only were the royal coffers depleted, but several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.

In the fall of 1786, Louis XVI’s controller general, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, proposed a financial reform package that included a universal land tax from which the aristocratic classes would no longer be exempt.

Estates General

To garner support for these measures and forestall a growing aristocratic revolt, the king summoned the Estates General ( les états généraux ) – an assembly representing France’s clergy, nobility and middle class – for the first time since 1614.

The meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789; in the meantime, delegates of the three estates from each locality would compile lists of grievances ( cahiers de doléances ) to present to the king.

Rise of the Third Estate

France’s population, of course, had changed considerably since 1614. The non-aristocratic, middle-class members of the Third Estate now represented 98 percent of the people but could still be outvoted by the other two bodies.

In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate began to mobilize support for equal representation and the abolishment of the noble veto—in other words, they wanted voting by head and not by status.

While all of the orders shared a common desire for fiscal and judicial reform as well as a more representative form of government, the nobles in particular were loath to give up the privileges they had long enjoyed under the traditional system.

Tennis Court Oath

By the time the Estates General convened at Versailles , the highly public debate over its voting process had erupted into open hostility between the three orders, eclipsing the original purpose of the meeting and the authority of the man who had convened it — the king himself.

On June 17, with talks over procedure stalled, the Third Estate met alone and formally adopted the title of National Assembly; three days later, they met in a nearby indoor tennis court and took the so-called Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

Within a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles had joined them, and on June 27 Louis XVI grudgingly absorbed all three orders into the new National Assembly.

The Bastille

On June 12, as the National Assembly (known as the National Constituent Assembly during its work on a constitution) continued to meet at Versailles, fear and violence consumed the capital.

Though enthusiastic about the recent breakdown of royal power, Parisians grew panicked as rumors of an impending military coup began to circulate. A popular insurgency culminated on July 14 when rioters stormed the Bastille fortress in an attempt to secure gunpowder and weapons; many consider this event, now commemorated in France as a national holiday, as the start of the French Revolution.

The wave of revolutionary fervor and widespread hysteria quickly swept the entire country. Revolting against years of exploitation, peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and the aristocratic elite.

Known as the Great Fear ( la Grande peur ), the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from France and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism on August 4, 1789, signing what historian Georges Lefebvre later called the “death certificate of the old order.”

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

IIn late August, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen ( Déclaration des droits de l ’homme et du citoyen ), a statement of democratic principles grounded in the philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The document proclaimed the Assembly’s commitment to replace the ancien régime with a system based on equal opportunity, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty and representative government.

Drafting a formal constitution proved much more of a challenge for the National Constituent Assembly, which had the added burden of functioning as a legislature during harsh economic times.

For months, its members wrestled with fundamental questions about the shape and expanse of France’s new political landscape. For instance, who would be responsible for electing delegates? Would the clergy owe allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church or the French government? Perhaps most importantly, how much authority would the king, his public image further weakened after a failed attempt to flee the country in June 1791, retain?

Adopted on September 3, 1791, France’s first written constitution echoed the more moderate voices in the Assembly, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the king enjoyed royal veto power and the ability to appoint ministers. This compromise did not sit well with influential radicals like Maximilien de Robespierre , Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, who began drumming up popular support for a more republican form of government and for the trial of Louis XVI.

French Revolution Turns Radical

In April 1792, the newly elected Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and Prussia, where it believed that French émigrés were building counterrevolutionary alliances; it also hoped to spread its revolutionary ideals across Europe through warfare.

On the domestic front, meanwhile, the political crisis took a radical turn when a group of insurgents led by the extremist Jacobins attacked the royal residence in Paris and arrested the king on August 10, 1792.

The following month, amid a wave of violence in which Parisian insurrectionists massacred hundreds of accused counterrevolutionaries, the Legislative Assembly was replaced by the National Convention, which proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French republic.

On January 21, 1793, it sent King Louis XVI, condemned to death for high treason and crimes against the state, to the guillotine ; his wife Marie-Antoinette suffered the same fate nine months later.

Reign of Terror

Following the king’s execution, war with various European powers and intense divisions within the National Convention brought the French Revolution to its most violent and turbulent phase.

In June 1793, the Jacobins seized control of the National Convention from the more moderate Girondins and instituted a series of radical measures, including the establishment of a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity .

They also unleashed the bloody Reign of Terror (la Terreur), a 10-month period in which suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands. Many of the killings were carried out under orders from Robespierre, who dominated the draconian Committee of Public Safety until his own execution on July 28, 1794.

Did you know? Over 17,000 people were officially tried and executed during the Reign of Terror, and an unknown number of others died in prison or without trial.

Thermidorian Reaction

The death of Robespierre marked the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction, a moderate phase in which the French people revolted against the Reign of Terror’s excesses.

On August 22, 1795, the National Convention, composed largely of Girondins who had survived the Reign of Terror, approved a new constitution that created France’s first bicameral legislature.

Executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory ( Directoire ) appointed by parliament. Royalists and Jacobins protested the new regime but were swiftly silenced by the army, now led by a young and successful general named Napoleon Bonaparte .

French Revolution Ends: Napoleon’s Rise

The Directory’s four years in power were riddled with financial crises, popular discontent, inefficiency and, above all, political corruption. By the late 1790s, the directors relied almost entirely on the military to maintain their authority and had ceded much of their power to the generals in the field.

On November 9, 1799, as frustration with their leadership reached a fever pitch, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “ first consul .” The event marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era, during which France would come to dominate much of continental Europe.

Photo Gallery

French Revolution. The National Archives (U.K.) The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State . Versailles, from the French Revolution to the Interwar Period. Chateau de Versailles . French Revolution. Monticello.org . Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French Revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

French Revolution

The French Revolution (1789-1799) was a period of major societal and political upheaval in France. It witnessed the collapse of the monarchy, the establishment of the First French Republic, and culminated in the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and the start of the Napoleonic era. The French Revolution is considered one of the defining events of Western history.

The Revolution of 1789, as it is sometimes called to distinguish it from later French revolutions, originated from deep-rooted problems that the government of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) proved incapable of fixing; such problems were primarily related to France's financial troubles as well as the systemic social inequality embedded within the Ancien Régime . The Estates-General of 1789 , summoned to address these issues, resulted in the formation of a National Constituent Assembly, a body of elected representatives from the three societal orders who swore never to disband until they had written a new constitution. Over the next decade, the revolutionaries attempted to dismantle the oppressive old society and build a new one based on the principles of the Age of Enlightenment exemplified in the motto: " Liberté, égalité, fraternité ."

Although initially successful in establishing a French Republic, the revolutionaries soon became embroiled in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) in which France fought against a coalition of major European powers. The Revolution quickly devolved into violent paranoia, and 20-40,000 people were killed in the Reign of Terror (1793-94), including many of the Revolution's former leaders. After the Terror, the Revolution stagnated until 1799, when Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) took control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire , ultimately transitioning the Republic into the First French Empire (1804-1814, 1815). Although the Revolution failed to prevent France from falling back into autocracy, it managed to succeed in other ways. It inspired numerous revolutions throughout the world and helped shape the modern concepts of nation-states, Western democracies, and human rights.

Most of the causes of the French Revolution can be traced to economic and social inequalities that were exacerbated by the brokenness of the Ancien Régime (“old regime”), the name retroactively given to the political and social system of the Kingdom of France in the last few centuries of its initial existence. The Ancien Régime was divided into three estates, or social orders: the clergy, nobility, and commoners. The first two estates enjoyed many social privileges, including tax exemptions, that were not granted to the commoners, a class that made up well over 90% of the population. The Third Estate was burdened with manual labor as well as paying most of the taxes.

Rapid population growth contributed to the general suffering; by 1789, France was the most populous European state with over 28 million people. Job growth had not kept up with the swelling population, leaving 8- 12 million impoverished. Backwards agricultural techniques and a steady string of terrible harvests led to starvation. Meanwhile, a rising class of wealthy commoners, the bourgeoisie, threatened the privileged position of the aristocracy, increasing tensions between social classes. Ideas of the Age of Enlightenment also contributed to national unrest; people began to view the Ancien Régime as corrupt, mismanaged, and tyrannical. Hatred was especially directed toward Queen Marie Antoinette , who was seen to personify everything wrong with the government.

A final significant cause was France's monumental state debt, accumulated by its attempts to maintain its status as a global power. Expensive wars and other projects had put the French treasury billions of livres into debt, as it had been forced to take out loans at enormously high interest rates. The country's irregular systems of taxation were ineffective, and as creditors began to call for repayment in the 1780s, the government finally realized something had to be done.

The Gathering Storm: 1774-1788

On 10 May 1774, King Louis XV of France died after a reign of nearly 60 years, leaving his grandson to inherit a troubled and broken kingdom. Only 19 years old, Louis XVI was an impressionable ruler who adhered to the advice of his ministers and involved France in the American War of Independence. Although French involvement in the American Revolution succeeded in weakening Great Britain , it also added substantially to France's debt while the success of the Americans encouraged anti-despotic sentiments at home.

In 1786, Louis XVI was convinced by his finance minister, Charles-Alexandre Calonne, that the issue of state debt could no longer be ignored. Calonne presented a list of financial reforms and convened the Assembly of Notables of 1787 to rubberstamp them. The Notables, a mostly aristocratic assembly, refused and told Calonne that only an Estates-General could approve such radical reforms. This referred to an assembly of the three estates of pre-revolutionary France , a body that had not been summoned in 175 years. Louis XVI refused, realizing that an Estates-General could undermine his authority. Instead, he fired Calonne and took the reforms to the parlements .

The parlements were the 13 judicial courts that were responsible for registering royal decrees before they went into effect. Consisting of aristocrats, the parlements had long struggled against royal authority, still bitter that their class had been subjugated by the "sun king" Louis XIV of France a century before. Spotting a chance to recover some power, they refused to register the royal reforms and joined the Notables in advocating for an Estates-General. When the crown responded by exiling the courts, riots erupted across the country; the parlements had presented themselves as champions of the people, thereby winning the commoners' support. One of these riots erupted in Grenoble on 7 June 1788 and led the three estates of Dauphiné to gather without the king's consent. Known as the Day of Tiles, this is credited by some historians as the start of the Revolution. Realizing he had been bested, Louis XVI appointed the popular Jacques Necker as his new finance minister and scheduled an Estates-General to convene in May 1789.

Rise of the Third Estate: February-September 1789

Across France, 6 million people participated in the electoral process for the Estates-General, and a total 25,000 cahiers de doléances , or lists of grievances, were drawn up for discussion. When the Estates-General of 1789 finally convened on 5 May in Versailles, there were 578 deputies representing the Third Estate, 282 for the nobility, and 303 for the clergy. Yet the double representation of the Third Estate was meaningless, as votes would still be counted by estate rather than by head. As the upper classes were sure to vote together, the Third Estate was at a disadvantage.

Subsequently, the Third Estate refused to verify its own elections, a process needed to begin proceedings. It demanded votes to be counted by head, a condition the nobility staunchly refused. Meanwhile, Louis XVI's attention was drawn away by the death of his son, paralyzing royal authority. On 13 June, having reached an impasse, the Third Estate commenced roll call, breaking protocol by beginning proceedings without the consent of the king or the other orders. On 17 June, following a motion proposed by Abbé Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès , the Third Estate officially proclaimed itself a National Constituent Assembly. Two days later, the clergy formally voted to join it, and the nobility begrudgingly followed suit. On 20 June, after finding themselves locked out of the assembly hall, the deputies of the National Assembly met in the royal tennis court. There, they swore the Tennis Court Oath, promising never to disband until they had given France a new constitution. The French Revolution had begun.

Louis XVI realized he needed to regain control. In early July, he called over 30,000 soldiers into the Paris Basin, and on 11 July, he dismissed Necker and other ministers considered too friendly to the insolent revolutionaries. Fearing the king meant to crush the Revolution, the people of Paris rioted on 12 July. Their uprising climaxed on 14 July with the Storming of the Bastille , when hundreds of citizens successfully attacked the Bastille fortress to loot it for ammunition. The king backed down, sending away his soldiers and reinstating Necker. Unnerved by these events, the king's youngest brother, Comte d'Artois, fled France with an entourage of royalists on the night of 16 July; they were the first of thousands of émigrés to flee.

In the coming weeks, the French countryside broke out into scattered riots, as rumors spread of aristocratic plots to deprive citizens of their liberties. These riots resulted in mini-Bastilles as peasants raided the feudal estates of local seigneurs, forcing nobles to renounce their feudal rights. Later known as the Great Fear , this wave of panic forced the National Assembly to confront the issue of feudalism . On the night of 4 August, in a wave of patriotic fervor, the Assembly announced that the feudal regime was "entirely destroyed" and ended the privileges of the upper classes. Later that month, it accepted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , a landmark human rights document that championed the general will of the people, separation of powers, and the idea that human rights were universal. These two achievements are considered the most important and longest-lasting accomplishments of the Revolution.

A People's Monarchy: 1789-1791

As the National Assembly slowly drafted its constitution, Louis XVI was sulking in Versailles. He refused to consent to the August Decrees and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, demanding instead that the deputies include his right to an absolute veto in the new constitution. This enraged the people of Paris, and on 5 October 1789, a crowd of 7,000 people, mostly market women , marched from Paris to Versailles in the pouring rain, demanding bread and that the king accept the Assembly's reforms. Louis XVI had no choice but to accept and was forced to leave his isolation at Versailles and accompany the women back to Paris, where he was installed in the Tuileries Palace . Known as the Women's March on Versailles , or the October Days, this insurrection led to the end of the Ancien Régime and the beginning of France's short-lived constitutional monarchy.

The next year and a half marked a relatively calm phase of the Revolution; indeed, many people believed the Revolution was over. Louis XVI agreed to adopt the Assembly's reforms and even appeared reconciled to the Revolution by accepting a tricolor cockade. The Assembly, meanwhile, began to rule France, adopting its own ill-fated currency, the assignat , to help tackle the outstanding debt. Having declawed the nobility, it now turned its attentions toward the Catholic Church. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy , issued on 12 July 1790, forced all clerics to swear oaths to the new constitution and put their loyalty to the state before their loyalty to the Pope in Rome . At the same time, church lands were confiscated by the Assembly, and the papal city of Avignon was reintegrated into France. These attacks on the church alienated many from the Revolution, including the pious Louis XVI himself.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the Bastille, saw a massive celebration on the Champ de Mars . Led by the Marquis de Lafayette , the Festival of the Federation was meant to mark the unity of the newly liberated French people under the magnanimous rule of their citizen-king. But the king had other plans. A year later, on the night of 20-21 June 1791, he and his family left the Tuileries in disguise and attempted to escape France in what has become known as the Flight to Varennes . They were quickly caught and returned to Paris, but their attempt had irrevocably destroyed any trust the people had in the monarchy. Calls began to mount for Louis XVI to be deposed, while some even began to seriously demand a French Republic. The issue divided the Jacobin Club, a political society where revolutionaries gathered to discuss their goals and agendas. Moderate members loyal to the idea of constitutional monarchy split to form the new Feuillant Club, while the remaining Jacobins were further radicalized.

On 17 July 1791, a crowd of demonstrators gathered on the Champ de Mars to demand the king's deposition. They were fired on by the Paris National Guard, commanded by Lafayette , resulting in 50 deaths. The Champ de Mars Massacre sent republicans on the run, giving the Feuillants enough time to push through their constitution, which centered around a weakened, liberal monarchy. On 30 September 1791, the new Legislative Assembly met, but despite the long-awaited constitution, the Revolution was more divided than ever.

Birth of a Republic: 1792-1793

Many deputies of the Legislative Assembly formed themselves into two factions: the more conservative Feuillants sat on the right of the Assembly president, while the radical Jacobins sat to his left, giving rise to the left/right political spectrum still used today. After the monarchs of Austria and Prussia threatened to destroy the Revolution in the Declaration of Pillnitz , a third faction split off from the Jacobins, demanding war as the only way to preserve the Revolution. This war party, later known as the Girondins, quickly dominated the Legislative Assembly, which voted to declare war on Austria on 20 April 1792. This began the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), as the old regimes of Europe , feeling threatened by the radical revolutionaries, joined together in a coalition against France.

Initially, the war went disastrously for the French. The summer of 1792 saw a Prussian army accompanied by French royalist émigrés slowly march toward Paris. In August, the invaders issued the Brunswick Manifesto, threatening to destroy Paris should any harm come to the French royal family. This threat sent the people of Paris into a hysterical panic that led to the Storming of the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792, the insurrection that finally toppled the monarchy. Still fearful of counter-revolutionary enemies who might aid the Prussians, Paris mobs then invaded the city's prisons and murdered over 1,100 people in the September Massacres .

On 20 September 1792, a French army finally halted the Prussian invasion at the miraculous Battle of Valmy . The next day, the jubilated Legislative Assembly officially proclaimed the French Republic. The later French Republican calendar dated itself from this moment, which was seen as the ultimate accomplishment of humankind. The Assembly was disbanded, and a National Convention was convened to draft a new constitution. One of the Convention's first tasks was to decide the fate of the deposed Louis XVI; ultimately, he was tried and guillotined on 21 January 1793, his family kept imprisoned in the Tower of the Temple until the trial and execution of Marie Antoinette that October. The trial and execution of Louis XVI shocked Europe, causing Great Britain, Spain, and the Dutch Republic to enter the coalition against France.

Reign of Terror: 1793-1794

After the decline of the Feuillants, the Girondins became the Revolution's moderate faction. In early 1793, they were opposed by a group of radical Jacobins called the Mountain, primarily led by Maximilien Robespierre , Georges Danton , and Jean- Paul Marat. The Girondins and the Mountain maintained a bitter rivalry until the fall of the Girondins on 2 June 1793, when roughly 80,000 sans-culottes , or lower-class revolutionaries, and National Guards surrounded the Tuileries Palace, demanding the arrests of leading Girondins. This was accomplished, and the Girondin leaders were later executed.

The Mountain's victory deeply divided the nation. The assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday occurred amidst pockets of civil war that threatened to unravel the infant republic, such as the War in the Vendée and the federalist revolts . To quell this dissent and halt the advance of coalition armies, the Convention approved the creation of the Committee of Public Safety , which quickly assumed near total executive power. Through measures such as mass conscription, the Committee brutally crushed the civil wars and checked the foreign armies before turning its attention to unmasking domestic traitors and counter-revolutionary agents. The ensuing Reign of Terror, lasting from September 1793-July 1794 resulted in hundreds of thousands of arrests, 16,594 executions by guillotine, and tens of thousands of additional deaths. Aristocrats and clergymen were executed alongside former revolutionary leaders and thousands of ordinary people.

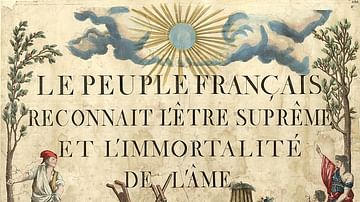

Robespierre accumulated almost dictatorial powers during this period. Attempting to curtail the Revolution's rampant dechristianization, he implemented the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being to ease France into his vision of a morally pure society. His enemies saw this as an attempt to claim total power and, fearing for their lives, decided to overthrow him; the fall of Maximilien Robespierre and his allies on 28 July 1794 brought the Terror to an end, and is considered by some historians to mark the decline of the Revolution itself.

Thermidorians & the Directory: 1794-1799

Robespierre's execution was followed by the Thermidorian Reaction , a period of conservative counter-revolution in which the vestiges of Jacobin rule were erased. The Jacobin Club itself was permanently closed in November 1794, and a Jacobin attempt to retake power in the Prairial Uprising of 1795 was crushed. The Thermidorians defeated a royalist uprising on 13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795) before adopting the Constitution of Year III (1795) and transitioning into the French Directory , the government that led the Republic in the final years of the Revolution.

Meanwhile, French armies had succeeded in pushing back the coalition's forces, defeating most coalition nations by 1797. The star of the war was undoubtedly General Napoleon Bonaparte, whose brilliant Italian campaign of 1796-97 catapulted him to fame. On 9 November 1799, Bonaparte took control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, bringing an end to the unpopular Directory. His ascendency marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Andress, David. The Terror . Time Warner Books Uk, 2005.

- Blanning, T. C. W. The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787-1802 . Hodder Education Publishers, 1996.

- Carlyle, Thomas & Sorensen, David R. & Kinser, Brent E. & Engel, Mark. The French Revolution . Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Davidson, Ian. The French Revolution. Pegasus Books, 2018.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Francois Furet & Mona Ozouf & Arthur Goldhammer. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Fraser, Antonia. Marie Antoinette. Anchor, 2002.

- Lefebvre, Georges & Palmer, R. R. & Palmer, R. R. & Tackett, Timothy. The Coming of the French Revolution . Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Lefebvre, Georges & White, John Albert. The Great Fear of 1789. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander. The Napoleonic Wars. Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Palmer, R. R. & Woloch, Isser. Twelve Who Ruled. Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon. Penguin Books, 2015.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens. Vintage, 1990.

- Scurr, Ruth. Fatal Purity. Holt Paperbacks, 2007.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de & Bevan, Gerald & Bevan, Gerald. The Ancien Régime and the Revolution . Penguin Classics, 2008.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What was the french revolution, what were 3 main causes of the french revolution, what began the french revolution, what ended the french revolution, what are some important events of the french revolution, related content.

Thermidorian Reaction

Georges Danton

Maximilien Robespierre

Fall of Maximilien Robespierre

Power Struggles in the Reign of Terror

Cult of the Supreme Being

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Princeton University Press (2017) |

| , published by Vintage (1990) |

| , published by East India Publishing Company (2023) |

| , published by Oxford University Press (2020) |

| , published by Oxford University Press (2018) |

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2023, January 12). French Revolution . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/French_Revolution/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " French Revolution ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified January 12, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/French_Revolution/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " French Revolution ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 12 Jan 2023. Web. 16 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 12 January 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

History of French Revolution Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Economic situation, malnutrition and hunger, the third estate.

The French Revolution was a time of extreme political and social unrest in Europe and France. France went through an ambitious transformation as privileges of church aristocracy and feudal faded under an unrelenting assault from the other political groups those in the streets and peasants (Spielvogel 526).

The further site abruptly overthrew the preceding ideas of hierarchy and training and brought the balance, rights and citizenship. A governing role played by external threats in the progress of the revolution. It started in 1789 where it looked at the third estate members declaring the human and citizenship rights.

Tension dominated the field in the next few years with the idea of wanting significant reforms. Before 1789, this country had encountered a time of economic growth since it had expanded its foreign trade and increased its production of industry. As a result, the causes of revolution in France can be found by examining the French society.

One of the causes of rioting in France is the ancient rule that had fallen. It became rigid. The intensifying aspiration of the tradesmen, farmers and merchants, associated with distressed peasants, intellectuals and wage-earners prejudiced by philosophers of enlightenment, confronted the aristocrats (Hunt 5).

At the advancement of the revolution, power passed to political bodies, which represented more. Nevertheless, bloodshed and significant discord caused by disagreements among the formerly associated groups of republic.

Ideas of civilization had penetrated the various classes of individuals in the French society, but there was a dispute on the depth of penetration. There was also a debate as to the extent to which the ideas adopted simply because of the self-interest of the bourgeois. The most accepted idea was that revolution was a channel, which facilitated an experiment in the ideas of democracy.

The bourgeoisie was a movement headed by classes while the middle class and the proletariat had no independent classes or divisions of classes (Hunt 6). The proletariats had not evolved their interests that were different from that of the governing class. The group fought for the achievement of the goals of the bourgeoisie, although in a manner of a non-bourgeoisie. The whole French terrorism was a means of dealing with the rivals of the bourgeoisie that is feudalism and absolutism.

Economy is another case of the France revolution. Although France went through some challenges, it was one of the most capable countries of Europe as far as the economy is concerned. France characterized by urbanization, had potential that was crucial in terms of cultivated area, productivity, industrialization level and the coarse domestic product. France effectively bankrupted on the eve of the revolution.

There was also a significant expenses while conducting the war against Britain, and France’ malicious attempt to thrust a finger on British eye by having the Americans in their independence war. After Britain won, the France government decided to make a fleet that was larger and built a coalition of allies against the British. This was to revenge and help France regain its colonies and in contrary resulted in debts.

Malnutrition and hunger in the poor population included in the economic factors. This was because of the inadequate harvests caused by El Nino food prices that was increasing and a transportation system that was inadequate, which prevented the shipment of foods from the rural to urban areas hence resulting to revolution.

In the estates general, there was the clergy, nobility and the rest of the people. After voting, ideas that would have appeared essential before; though supported the organization of the monarchy articulated (Spielvogel 529). Many people implicated that the Estates-general would recommend taxes in future and ideals of the enlightenment were rare.

The requirements of the Third Estate were that males born in French resided the voting place and the people to pay taxes. A financial strain is the most significant source of revolution since the country could do nothing since it had to pay the debts first. Living condition, rise of food prices and property issues are the second since it affected the needy people. It is appropriate for ideas of awareness about how an administration or government should be controlled to be practiced and thus becomes the third.

The fourth is the American war because France had to spend a large amount of money by building navies that could fight against the British as a way of revenge. The fifth is the bourgeoisie in France. Revolution was a medium of dealing with the rivals of the privileged class. The sixth is the system of voting because it allowed one vote per member. The last is the 3rd Estate’s actions where the French born decided on voting place and payment of taxes.

In conclusion, the government was not able to synchronize the parties that were in dispute at court and arriving at the policies of economy.

The fiscal strain of paying old debts and the extremes of the present noble court brought dissatisfaction with the realm, added to unrest of the nation, and ended in the revolution of France of 1789. The enlightenment ideas contributed to the rise of French revolution since it penetrated to all the classes in the French society (Todd 57). Revolution was due to a series of events, which together forever changed how political power organized, exercising of freedoms of individuals and the natural history of society.

Hunt, Jocelyn. The French Revolution. London: Routledge, 1998.

Spielvogel, Jackson. Western Civilization: Since 1300 . Chicago: Cengage Learning, 2011.

Todd, Allan. Revolutions 1789-1917. Cambridge: Cambridge University Publishers, 2001.

- Food Scarcity Factor in French Revolution

- US Government 1789-1821

- Enlightenment Ideas During the French Revolution Period

- Major social groups in France prior to the French revolution

- What Caused the French Revolution?

- Absolutism in French Revolution

- History of the English Population During the 19th Century

- The Renaissance and Its Cultural, Political and Economic Influence

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, June 12). History of French Revolution. https://ivypanda.com/essays/french-revolution/

"History of French Revolution." IvyPanda , 12 June 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/french-revolution/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'History of French Revolution'. 12 June.

IvyPanda . 2018. "History of French Revolution." June 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/french-revolution/.

1. IvyPanda . "History of French Revolution." June 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/french-revolution/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "History of French Revolution." June 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/french-revolution/.

- The French Revolution

Introduction

How a revolution that began with the lofty purposes of the Declaration of Rights and Man and Citizen, a statement of universal individual rights, so rapidly devolved into a Reign of Terror is one of the most vexing questions about the French Revolution. Teachers who have but two or three days (a best-case scenario) to lecture on the French Revolution are often forced to rely on the largely discredited theory that the French Revolution was a creation of the French bourgeoisie and the Terror was a reaction to a proto-socialist worker's movement.

This lesson plan focuses on two competing interpretations of the Terror: one political and the other ideological. The political interpretation claims that the first-generation revolutionaries enshrined individual liberties only to have their aspirations crushed by an escalating set of political crises—the foreign war, the outbreak of civil war in western France, and the political maneuvering of a monarch who became increasingly hostile to the French Revolution. The Terror was, therefore, a political reaction to political and diplomatic circumstances by a revolutionary government under siege.

The ideological interpretation argues that the seeds of the Reign of Terror were already planted in 1789. Rather than creating the individual rights of the citizen, the revolutionaries of 1789, with no political experience on which to draw, drew upon the only political model available, the absolute monarchy. This claim holds that unity of the "nation" was far more important than the rights of the citizen. Onto this, the Revolution grafted the republican ideology of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose concept of a unanimous and infallible "general will" was a comfortable but abstract replacement for the absolute monarchy. However, the abstraction of the nation was a poor substitute for a flesh-and-blood king and thus generated hostility to the Revolution. The foreign and civil wars along with the Reign of Terror, therefore, were symptomatic of the failure to achieve national unity, not the cause of the excesses of the Terror government.

The focus on the debate between individual rights versus the unified nation and the related debate about the origins of the Reign of Terror presented here offers students the opportunity to analyze primary documents, both visual and printed. It also offers a good case study for the interrelationship between ideology and politics. Finally, by focusing on these issues specifically, this lesson should help prepare students for the study of the politics and ideologies of the nineteenth century, especially liberalism, conservatism, and socialism, all of which have connections to the political philosophy of the French Revolution.

To explain the collapse of absolutism in France and the consequences of the political vacuum created by its downfall for the course of the Revolution.

To be able to describe and contrast the two competing ideologies by which French revolutionaries reconstituted France as a nation, rather than a kingdom, and individuals as citizens instead of subjects.

To comprehend and analyze interpretations of the causes of the Reign of Terror as either the creation of specific political circumstances or as the logical consequence of the ideologies of the early Revolution.

To be able to interpret products of revolutionary political culture, such as written and visual political propaganda, as tools in understanding political ideology.

I. The Pre-Revolution Period

While it will be important to explain the various aspects of the pre-Revolution period, such as the financial crisis of the monarchy and the division of French society into distinct orders of clergy, nobility, and commoners, this lesson plan relies heavily on an understanding of Enlightenment philosophy.

The eighteenth-century philosophical movement known as the Enlightenment challenged both the social order and absolute monarchy by questioning the assumptions on which these institutions were based. Rather than accepting tradition as a basis for rule, reason dictated what was best for society and government. Thus, the philosophes of the Enlightenment began to speak of the social contract as a basis for governance and of individual rights.

John Locke, the English philosopher who was influential in France, argued that humans had "inalienable liberties" as individuals. In France, philosophes such as Voltaire promoted the ideology of individual liberty, but Voltaire was far from becoming a democrat. He believed in "enlightened absolutism" as the surest defender of individual liberty. Nevertheless, many of the philosophes of the later Enlightenment, the last two decades prior to the Revolution, such as the Marquis de Condorcet, would support both republicanism and the rights of the individual.

The focus on individual rights, however, was by no means the only voice of the Enlightenment concerning the social contract. The political philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau similarly dealt with the basis of a just form of government and the rights of citizens within that ideal state. However, unlike Locke, who believed that the rights of the individual could never be lost, Rousseau claimed that in the perfect form of government, citizens willingly alienated their rights in the name of the "general will"—that is, the unanimous consent of the citizenry who acted out of civic virtue rather than individual self-interest. The text of Rousseau's Social Contract can be found at the Enlightenment and Human Rights section of George Mason University's website Exploring the French Revolution .

II. The Revolution Begins

A. the meeting of the estates-general.

Prior to the meeting of the Estates-General, the issue of voting procedures became the dominant political theme, overshadowing specific grievances and reform proposals drawn up by each estate, known as Cahiers de doleances . Tradition mandated that each estate meet separately and vote as an estate, that is, one vote for the clergy, one for the nobility, and one for the commoners.

The Third Estate protested that because they represented the vast majority of the French population, voting should be by head, one vote per delegate. The crown turned the matter over to the Parlement of Paris, who decided that voting initially must be done in the traditional format, but did not forbid the possibility that the format could be amended by the Estates-General itself.

One argument, which certainly contemporaries believed, was that the Parlement's decision was part of an aristocratic reaction to prevent the Third Estate from having a legitimate voice. Abbé Sieyes's pamphlet "What Is the Third Estate?" is one of the more hostile responses to the Parlement's decision.

Once convened at Versailles, the Estates-General became bogged down in a debate over voting. The Third Estate hoped to debate the issue with the other two groups, but the crown provided no clear instruction on how to proceed, other than that the edict of the Paris court should be followed. The impasse led to the breakdown of the Estates-General and the Third Estate's declaration that they alone represented the French nation as the "National Assembly."

This was the beginning of the French Revolution. The defection of members of the First Estate, mostly parish clergy, and a handful of liberal members of the Second Estate to the National Assembly forced the crown to recognize the National Assembly as legitimate.

One approach to the opening of the Estates-General is to examine various images that represented the three orders of France. Some, such as the "The Joyous Accord" and Jacques-Louis David's "The Tennis Court Oath," emphasize the Estates-General and the creation of the National Assembly as a unifying experience. Others, such as "The Third Estate Awakens," stress the divisions between the orders. These images are available on the Exploring the French Revolution website. Search by title.

Activity: Reenacting the Estates-General

Divide the class into three “estates.” The numbers should be roughly divided so that half the class is divided into the First and Second Estates and the remaining half into the Third Estate—this is how the breakdown actually occurred in 1789.

Without the support of some members of the First or Second Estates, even "voting by head" was no guarantee of political victory for the Third Estate. Any proposals by the Third Estate must therefore appeal to some of the other two groups. Some students can be identified as impoverished priests or "enlightened" aristocrats. Have students "fix" the crown's financial crisis.

Students may very well ask how to proceed with their debate, much as did the Estates-General itself. Acting as the crown, the instructor should in fact give little indication of procedure. Hopefully, students will find the only way to agree as to procedure will be through uniting the three separate estates into one group.

Assignment: Document Analysis

Have students write an essay analyzing Sieyes's "What Is the Third Estate?" Is the primary ideological basis for Sieyes Voltaire's individual liberties or Rousseau's general will? Does this foreshadow what would actually transpire in 1789?

B. Popular Reaction and Creating a Constitutional Response

The "people" of France became a force in the Revolution through the taking of the Bastille in Paris on July 14, 1789, and the anti-aristocratic "Great Fear" of the peasantry during the entire summer. These are both important events in the course of the Revolution; however, for the purpose of this lesson plan, they form the backdrop against which the National Assembly was forced to create a new constitution for France.

A response to the Great Fear was the abolition of feudalism on August 5, 1789. This may be viewed as an immediate political response to the Great Fear or as part of the logic of creating a nation that was founded on the general will and therefore unified. The same analysis can be made with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of August 26, 1789. This text and the decree abolishing feudalism are also available on the Exploring the French Revolution website.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1791 was more complicated. Rather than drawing on the American model, which prohibited the establishment of a state church, the Assembly made the Catholic Church an organ of the State, and members of the clergy paid civil servants.

Papal condemnation of the Civil Constitution polarized French society into groups of "good Catholics" versus "good Revolutionaries." However, it is possible to argue that the Civil Constitution of the Clergy was necessary not only because the new government needed to gain control over Church income but also because ideologically, like feudalism, a "separate" corps of clergy prevented true national unity. Therefore, even priests and monks needed to become incorporated into the general will. See, for example, the image "Monks Learning to Exercise" on the Exploring the French Revolution site.

Divide students into groups representing "individual liberties" versus the "general will." Have them debate the merits and failings of specific aspects of the Abolition of Feudalism, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, and the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Is there ideological consistency in these documents and/or images?

III. The Revolution Radicalizes

The radical phase of the French Revolution, or the Reign of Terror, is currently analyzed as either a reaction to specific events, such as foreign wars and internal counterrevolution, or as the logical consequence of the ideologies of 1789. Historians who view the guiding political ideology of the early Revolution as one dedicated to protecting the individual liberties of "citizens" interpret the stripping away of those liberties as an unfortunate response to the crises created by foreign and civil war. However, many other historians view the Terror as a completion of the ideology of the general will—that in order to create a nation, the rights of the citizen became subordinate to the rights of the nation. War and counterrevolution thus were the symptoms, not the cause, of the failure to achieve unity, and the Terror was the attempt to enshrine the unified general will by force.

There is no question that the Reign of Terror was a complicated and confusing phenomenon. To account for details of the foreign and civil wars, the political struggles between the Jacobins and Girondins, the economic crisis, and urban unrest could take almost an entire course itself. One way to approach the Reign of Terror is by using the trial of Louis XVI as a case study. Royal recalcitrance toward the Revolutionary government, which accelerated following his failed attempt to flee France in 1791, eventually led to his arrest, trial as a traitor, and execution.

Analysis of the numerous documents in the Exploring the French Revolution database (search: "trial King") exposes both interpretations of the Reign of Terror. Having the monarch become an enemy of the Revolution certainly created a political crisis to which the Reign of Terror may well have been a response. However, many of the documents also demonstrate that the king was no more exempt from the dictates of the general will and therefore no more or less a part of the greater nation than any other individual.

Activity: The King's Trial

Assign roles to individual students and recreate the trial of Louis XVI (or Citizen Capet, as the charge formally read). Students without specific parts serve as the Constituent Assembly (formerly the National Assembly) and the jury. Those on the side of the prosecution can be further divided into advocates for the general will and those who support the trial because of political necessity. Similarly, the defense can be divided into two groups: one of "absolutists" who might argue that the king by definition can never be a traitor, and another of "individual rights" supporters who might claim that although the monarch was no different than any other citizen, his trial was a violation of his individual rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen.

Assignment: The Constitutions of 1789 and 1793

A second approach to the Reign of Terror is through a document analysis of the Declaration of Rights within the French constitutions of 1789 and 1793. Again, the theory of circumstance will see the rights outlined in 1789 to be basic and individual while those of 1793 to be radically different. The alternate interpretation would view the rights outlined in 1793 as only an intensification of the same political ideology present in the Declaration of 1789. Ask students to write an essay comparing and contrasting the two views.

IV. The Rise of Napoleon

In many ways, the downfall of Robespierre and the collapse of the Terror government set the stage for the Napoleonic dictatorship, just as 1789 perhaps set the stage for the Terror. Over the course of the Directory, the government hoped to avoid the excesses of the radical revolution by maintaining a "middle ground" between Jacobinism and the resurgent aristocratic and monarchical movement that returned to France after the Thermidorian Reaction.

In order to preserve moderate politics, the Directory interfered with elections for the Council of 500 (the lower house of the post-Terror government) by nullifying election results that leaned either too far to the left or the right. Hence, the Directory increasingly invalidated its own constitution, was ineffective in governing, and made the 1799 Brumaire Coup of Napoleon, Abbé Sieyes, and Roger Ducos possible.

Napoleon is, of course, as controversial as the Terror. Having claimed, "The revolution is over!" upon his seizure of power during the Brumaire Coup, he portrayed himself as the savior of the Revolution, bringing it to a successful completion. Indeed, his Civil Code, although harsh, was perhaps no worse than the laws passed by the Terror government. And with the Code, France was truly unified under a single code of law, with a political leader who possessed the power to enforce it.

However, Napoleon also restored the aristocracy, although his nobility was open to men of talent, not birthright, and he plunged France into a war of empire. In the end, Napoleon did not look much different than the absolute monarchs of the pre-Revolution period.

Additional Resources

Baker, Keith Michael. Inventing the French Revolution: Essays on French Political Culture in the Eighteenth Century . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. This is one of the best studies of the impact of Rousseau's political philosophy on the French Revolution.

de Tocqueville, Alexis. The Old Regime and the French Revolution . Translated by Stuart Gilbert. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1955. This nineteenth-century classic originated the interpretation that the Terror originated in 1789.

Doyle, William. The Origins of the French Revolution . Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. See part 1 of this book for an excellent overview of the various interpretations of the French Revolution, including strengths and weaknesses of each.

Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution . New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. This study favors the interpretation of individual rights and the circumstantial origins of the Reign of Terror, stressing the role of the foreign war.

Furet, Francois. "The Revolution Is Over." In Interpreting the French Revolution . Edited by Francois Furet. Translated by Elborg Forster. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981. This essay focuses on the relationship between the events of 1789 and Old Regime absolutism leading to the Reign of Terror.

Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. An excellent study of revolutionary imagery, offers a compelling synthesis between the individual rights and circumstantial interpretations of the origins of the Terror.

Sutherland, Donald M. G. France, 1789-1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution . London: Fontana Press/Collins, 1985. This falls into the circumstantial origins of the Terror interpretation and emphasizes internal social divide and conflict.

- Early Modern Empires

- The Structures of Nineteenth-Century Government

- German Unification

- The Russian Revolution

- The Cold War

- German Reunification, 1989-90

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The 1789 revolution took place at a time when the French monarchy had absolute power, governing the whole country and implementing high tax due to massive debt caused by wars that King Louis XVI had participated in including the American war of independence.

The French Revolution was a period of major social upheaval that began in 1787 and ended in 1799. It sought to completely change the relationship between the rulers and those they governed and to redefine the nature of political power.

The French revolution that took place in 1789-1799 was a period of political and social upheaval in France. However, the revolution did not only affect France alone but also the whole of Europe (Lefebvre 6).

This essay delves into the causes, key events, and lasting impact of the French Revolution, illuminating its significance in the evolution of democracy and social change.

Introduction To French Revolution. In the year 1789, French Revolution started leading to a series of the events started by the middle class. The people had revolted against the cruel regime of the monarchy. This revolution had put forth the ideas of liberty, fraternity as well as equality.

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens...

The French Revolution was a period of major social and political upheaval in France that lasted from 1789-1799. Its goals were to dismantle France's oppressive old regime and create a new society based around Enlightenment Age principles such as the general will of the people and natural rights.

Introduction. The French Revolution was a time of extreme political and social unrest in Europe and France. France went through an ambitious transformation as privileges of church aristocracy and feudal faded under an unrelenting assault from the other political groups those in the streets and peasants (Spielvogel 526).

From a general summary to chapter summaries to explanations of famous quotes, the SparkNotes The French Revolution (1789–1799) Study Guide has everything you need to ace quizzes, tests, and essays.

Introduction. How a revolution that began with the lofty purposes of the Declaration of Rights and Man and Citizen, a statement of universal individual rights, so rapidly devolved into a Reign of Terror is one of the most vexing questions about the French Revolution.