How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free results chapter template

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips for writing an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

23 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

For qualitative studies, can the findings be structured according to the Research questions? Thank you.

Do I need to include literature/references in my findings chapter?

This was very helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Analysis

23 Presenting the Results of Qualitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

Qualitative research is not finished just because you have determined the main findings or conclusions of your study. Indeed, disseminating the results is an essential part of the research process. By sharing your results with others, whether in written form as scholarly paper or an applied report or in some alternative format like an oral presentation, an infographic, or a video, you ensure that your findings become part of the ongoing conversation of scholarship in your field, forming part of the foundation for future researchers. This chapter provides an introduction to writing about qualitative research findings. It will outline how writing continues to contribute to the analysis process, what concerns researchers should keep in mind as they draft their presentations of findings, and how best to organize qualitative research writing

As you move through the research process, it is essential to keep yourself organized. Organizing your data, memos, and notes aids both the analytical and the writing processes. Whether you use electronic or physical, real-world filing and organizational systems, these systems help make sense of the mountains of data you have and assure you focus your attention on the themes and ideas you have determined are important (Warren and Karner 2015). Be sure that you have kept detailed notes on all of the decisions you have made and procedures you have followed in carrying out research design, data collection, and analysis, as these will guide your ultimate write-up.

First and foremost, researchers should keep in mind that writing is in fact a form of thinking. Writing is an excellent way to discover ideas and arguments and to further develop an analysis. As you write, more ideas will occur to you, things that were previously confusing will start to make sense, and arguments will take a clear shape rather than being amorphous and poorly-organized. However, writing-as-thinking cannot be the final version that you share with others. Good-quality writing does not display the workings of your thought process. It is reorganized and revised (more on that later) to present the data and arguments important in a particular piece. And revision is totally normal! No one expects the first draft of a piece of writing to be ready for prime time. So write rough drafts and memos and notes to yourself and use them to think, and then revise them until the piece is the way you want it to be for sharing.

Bergin (2018) lays out a set of key concerns for appropriate writing about research. First, present your results accurately, without exaggerating or misrepresenting. It is very easy to overstate your findings by accident if you are enthusiastic about what you have found, so it is important to take care and use appropriate cautions about the limitations of the research. You also need to work to ensure that you communicate your findings in a way people can understand, using clear and appropriate language that is adjusted to the level of those you are communicating with. And you must be clear and transparent about the methodological strategies employed in the research. Remember, the goal is, as much as possible, to describe your research in a way that would permit others to replicate the study. There are a variety of other concerns and decision points that qualitative researchers must keep in mind, including the extent to which to include quantification in their presentation of results, ethics, considerations of audience and voice, and how to bring the richness of qualitative data to life.

Quantification, as you have learned, refers to the process of turning data into numbers. It can indeed be very useful to count and tabulate quantitative data drawn from qualitative research. For instance, if you were doing a study of dual-earner households and wanted to know how many had an equal division of household labor and how many did not, you might want to count those numbers up and include them as part of the final write-up. However, researchers need to take care when they are writing about quantified qualitative data. Qualitative data is not as generalizable as quantitative data, so quantification can be very misleading. Thus, qualitative researchers should strive to use raw numbers instead of the percentages that are more appropriate for quantitative research. Writing, for instance, “15 of the 20 people I interviewed prefer pancakes to waffles” is a simple description of the data; writing “75% of people prefer pancakes” suggests a generalizable claim that is not likely supported by the data. Note that mixing numbers with qualitative data is really a type of mixed-methods approach. Mixed-methods approaches are good, but sometimes they seduce researchers into focusing on the persuasive power of numbers and tables rather than capitalizing on the inherent richness of their qualitative data.

A variety of issues of scholarly ethics and research integrity are raised by the writing process. Some of these are unique to qualitative research, while others are more universal concerns for all academic and professional writing. For example, it is essential to avoid plagiarism and misuse of sources. All quotations that appear in a text must be properly cited, whether with in-text and bibliographic citations to the source or with an attribution to the research participant (or the participant’s pseudonym or description in order to protect confidentiality) who said those words. Where writers will paraphrase a text or a participant’s words, they need to make sure that the paraphrase they develop accurately reflects the meaning of the original words. Thus, some scholars suggest that participants should have the opportunity to read (or to have read to them, if they cannot read the text themselves) all sections of the text in which they, their words, or their ideas are presented to ensure accuracy and enable participants to maintain control over their lives.

Audience and Voice

When writing, researchers must consider their audience(s) and the effects they want their writing to have on these audiences. The designated audience will dictate the voice used in the writing, or the individual style and personality of a piece of text. Keep in mind that the potential audience for qualitative research is often much more diverse than that for quantitative research because of the accessibility of the data and the extent to which the writing can be accessible and interesting. Yet individual pieces of writing are typically pitched to a more specific subset of the audience.

Let us consider one potential research study, an ethnography involving participant-observation of the same children both when they are at daycare facility and when they are at home with their families to try to understand how daycare might impact behavior and social development. The findings of this study might be of interest to a wide variety of potential audiences: academic peers, whether at your own academic institution, in your broader discipline, or multidisciplinary; people responsible for creating laws and policies; practitioners who run or teach at day care centers; and the general public, including both people who are interested in child development more generally and those who are themselves parents making decisions about child care for their own children. And the way you write for each of these audiences will be somewhat different. Take a moment and think through what some of these differences might look like.

If you are writing to academic audiences, using specialized academic language and working within the typical constraints of scholarly genres, as will be discussed below, can be an important part of convincing others that your work is legitimate and should be taken seriously. Your writing will be formal. Even if you are writing for students and faculty you already know—your classmates, for instance—you are often asked to imitate the style of academic writing that is used in publications, as this is part of learning to become part of the scholarly conversation. When speaking to academic audiences outside your discipline, you may need to be more careful about jargon and specialized language, as disciplines do not always share the same key terms. For instance, in sociology, scholars use the term diffusion to refer to the way new ideas or practices spread from organization to organization. In the field of international relations, scholars often used the term cascade to refer to the way ideas or practices spread from nation to nation. These terms are describing what is fundamentally the same concept, but they are different terms—and a scholar from one field might have no idea what a scholar from a different field is talking about! Therefore, while the formality and academic structure of the text would stay the same, a writer with a multidisciplinary audience might need to pay more attention to defining their terms in the body of the text.

It is not only other academic scholars who expect to see formal writing. Policymakers tend to expect formality when ideas are presented to them, as well. However, the content and style of the writing will be different. Much less academic jargon should be used, and the most important findings and policy implications should be emphasized right from the start rather than initially focusing on prior literature and theoretical models as you might for an academic audience. Long discussions of research methods should also be minimized. Similarly, when you write for practitioners, the findings and implications for practice should be highlighted. The reading level of the text will vary depending on the typical background of the practitioners to whom you are writing—you can make very different assumptions about the general knowledge and reading abilities of a group of hospital medical directors with MDs than you can about a group of case workers who have a post-high-school certificate. Consider the primary language of your audience as well. The fact that someone can get by in spoken English does not mean they have the vocabulary or English reading skills to digest a complex report. But the fact that someone’s vocabulary is limited says little about their intellectual abilities, so try your best to convey the important complexity of the ideas and findings from your research without dumbing them down—even if you must limit your vocabulary usage.

When writing for the general public, you will want to move even further towards emphasizing key findings and policy implications, but you also want to draw on the most interesting aspects of your data. General readers will read sociological texts that are rich with ethnographic or other kinds of detail—it is almost like reality television on a page! And this is a contrast to busy policymakers and practitioners, who probably want to learn the main findings as quickly as possible so they can go about their busy lives. But also keep in mind that there is a wide variation in reading levels. Journalists at publications pegged to the general public are often advised to write at about a tenth-grade reading level, which would leave most of the specialized terminology we develop in our research fields out of reach. If you want to be accessible to even more people, your vocabulary must be even more limited. The excellent exercise of trying to write using the 1,000 most common English words, available at the Up-Goer Five website ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ) does a good job of illustrating this challenge (Sanderson n.d.).

Another element of voice is whether to write in the first person. While many students are instructed to avoid the use of the first person in academic writing, this advice needs to be taken with a grain of salt. There are indeed many contexts in which the first person is best avoided, at least as long as writers can find ways to build strong, comprehensible sentences without its use, including most quantitative research writing. However, if the alternative to using the first person is crafting a sentence like “it is proposed that the researcher will conduct interviews,” it is preferable to write “I propose to conduct interviews.” In qualitative research, in fact, the use of the first person is far more common. This is because the researcher is central to the research project. Qualitative researchers can themselves be understood as research instruments, and thus eliminating the use of the first person in writing is in a sense eliminating information about the conduct of the researchers themselves.

But the question really extends beyond the issue of first-person or third-person. Qualitative researchers have choices about how and whether to foreground themselves in their writing, not just in terms of using the first person, but also in terms of whether to emphasize their own subjectivity and reflexivity, their impressions and ideas, and their role in the setting. In contrast, conventional quantitative research in the positivist tradition really tries to eliminate the author from the study—which indeed is exactly why typical quantitative research avoids the use of the first person. Keep in mind that emphasizing researchers’ roles and reflexivity and using the first person does not mean crafting articles that provide overwhelming detail about the author’s thoughts and practices. Readers do not need to hear, and should not be told, which database you used to search for journal articles, how many hours you spent transcribing, or whether the research process was stressful—save these things for the memos you write to yourself. Rather, readers need to hear how you interacted with research participants, how your standpoint may have shaped the findings, and what analytical procedures you carried out.

Making Data Come Alive

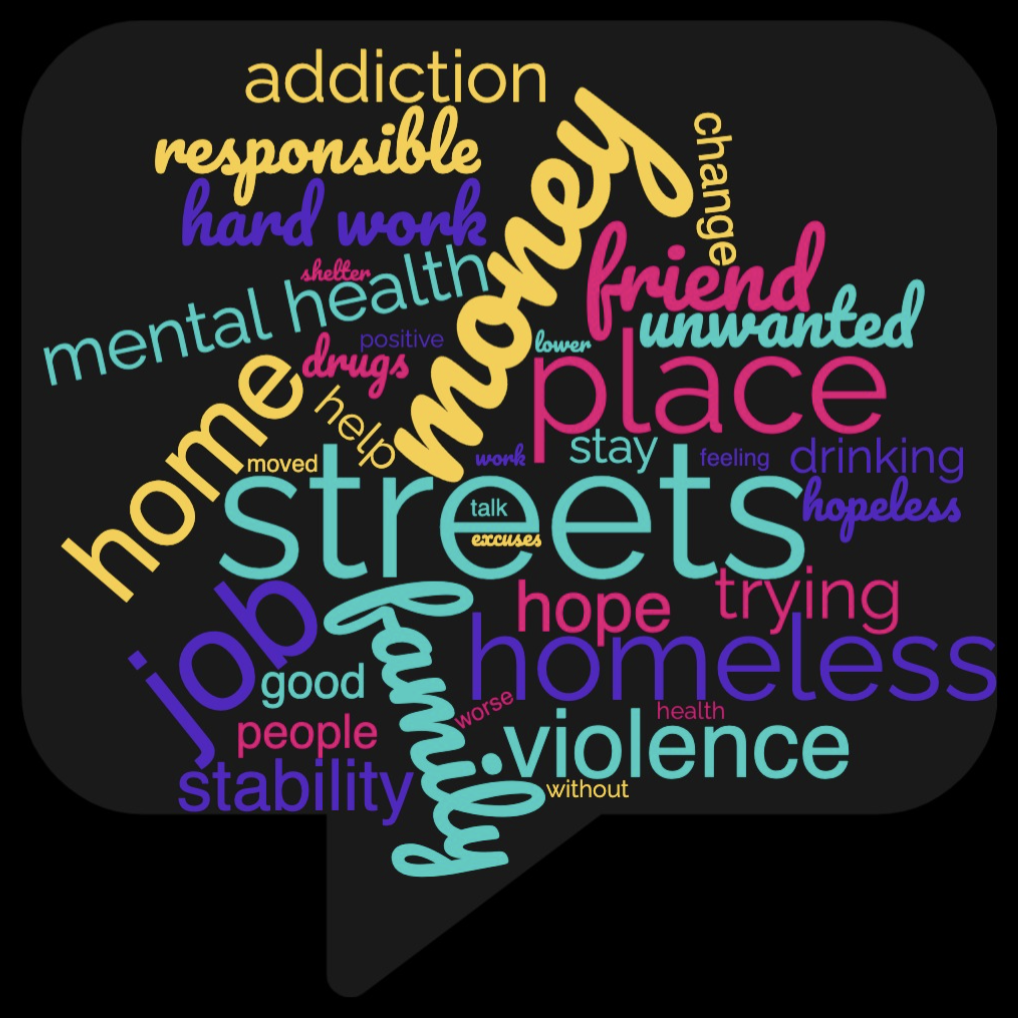

One of the most important parts of writing about qualitative research is presenting the data in a way that makes its richness and value accessible to readers. As the discussion of analysis in the prior chapter suggests, there are a variety of ways to do this. Researchers may select key quotes or images to illustrate points, write up specific case studies that exemplify their argument, or develop vignettes (little stories) that illustrate ideas and themes, all drawing directly on the research data. Researchers can also write more lengthy summaries, narratives, and thick descriptions.

Nearly all qualitative work includes quotes from research participants or documents to some extent, though ethnographic work may focus more on thick description than on relaying participants’ own words. When quotes are presented, they must be explained and interpreted—they cannot stand on their own. This is one of the ways in which qualitative research can be distinguished from journalism. Journalism presents what happened, but social science needs to present the “why,” and the why is best explained by the researcher.

So how do authors go about integrating quotes into their written work? Julie Posselt (2017), a sociologist who studies graduate education, provides a set of instructions. First of all, authors need to remain focused on the core questions of their research, and avoid getting distracted by quotes that are interesting or attention-grabbing but not so relevant to the research question. Selecting the right quotes, those that illustrate the ideas and arguments of the paper, is an important part of the writing process. Second, not all quotes should be the same length (just like not all sentences or paragraphs in a paper should be the same length). Include some quotes that are just phrases, others that are a sentence or so, and others that are longer. We call longer quotes, generally those more than about three lines long, block quotes , and they are typically indented on both sides to set them off from the surrounding text. For all quotes, be sure to summarize what the quote should be telling or showing the reader, connect this quote to other quotes that are similar or different, and provide transitions in the discussion to move from quote to quote and from topic to topic. Especially for longer quotes, it is helpful to do some of this writing before the quote to preview what is coming and other writing after the quote to make clear what readers should have come to understand. Remember, it is always the author’s job to interpret the data. Presenting excerpts of the data, like quotes, in a form the reader can access does not minimize the importance of this job. Be sure that you are explaining the meaning of the data you present.

A few more notes about writing with quotes: avoid patchwriting, whether in your literature review or the section of your paper in which quotes from respondents are presented. Patchwriting is a writing practice wherein the author lightly paraphrases original texts but stays so close to those texts that there is little the author has added. Sometimes, this even takes the form of presenting a series of quotes, properly documented, with nothing much in the way of text generated by the author. A patchwriting approach does not build the scholarly conversation forward, as it does not represent any kind of new contribution on the part of the author. It is of course fine to paraphrase quotes, as long as the meaning is not changed. But if you use direct quotes, do not edit the text of the quotes unless how you edit them does not change the meaning and you have made clear through the use of ellipses (…) and brackets ([])what kinds of edits have been made. For example, consider this exchange from Matthew Desmond’s (2012:1317) research on evictions:

The thing was, I wasn’t never gonna let Crystal come and stay with me from the get go. I just told her that to throw her off. And she wasn’t fittin’ to come stay with me with no money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

A paraphrase of this exchange might read “She said that she was going to let Crystal stay with her if Crystal did not have any money.” Paraphrases like that are fine. What is not fine is rewording the statement but treating it like a quote, for instance writing:

The thing was, I was not going to let Crystal come and stay with me from beginning. I just told her that to throw her off. And it was not proper for her to come stay with me without any money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

But as you can see, the change in language and style removes some of the distinct meaning of the original quote. Instead, writers should leave as much of the original language as possible. If some text in the middle of the quote needs to be removed, as in this example, ellipses are used to show that this has occurred. And if a word needs to be added to clarify, it is placed in square brackets to show that it was not part of the original quote.

Data can also be presented through the use of data displays like tables, charts, graphs, diagrams, and infographics created for publication or presentation, as well as through the use of visual material collected during the research process. Note that if visuals are used, the author must have the legal right to use them. Photographs or diagrams created by the author themselves—or by research participants who have signed consent forms for their work to be used, are fine. But photographs, and sometimes even excerpts from archival documents, may be owned by others from whom researchers must get permission in order to use them.

A large percentage of qualitative research does not include any data displays or visualizations. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider whether the use of data displays will help the reader understand the data. One of the most common types of data displays used by qualitative researchers are simple tables. These might include tables summarizing key data about cases included in the study; tables laying out the characteristics of different taxonomic elements or types developed as part of the analysis; tables counting the incidence of various elements; and 2×2 tables (two columns and two rows) illuminating a theory. Basic network or process diagrams are also commonly included. If data displays are used, it is essential that researchers include context and analysis alongside data displays rather than letting them stand by themselves, and it is preferable to continue to present excerpts and examples from the data rather than just relying on summaries in the tables.

If you will be using graphs, infographics, or other data visualizations, it is important that you attend to making them useful and accurate (Bergin 2018). Think about the viewer or user as your audience and ensure the data visualizations will be comprehensible. You may need to include more detail or labels than you might think. Ensure that data visualizations are laid out and labeled clearly and that you make visual choices that enhance viewers’ ability to understand the points you intend to communicate using the visual in question. Finally, given the ease with which it is possible to design visuals that are deceptive or misleading, it is essential to make ethical and responsible choices in the construction of visualization so that viewers will interpret them in accurate ways.

The Genre of Research Writing

As discussed above, the style and format in which results are presented depends on the audience they are intended for. These differences in styles and format are part of the genre of writing. Genre is a term referring to the rules of a specific form of creative or productive work. Thus, the academic journal article—and student papers based on this form—is one genre. A report or policy paper is another. The discussion below will focus on the academic journal article, but note that reports and policy papers follow somewhat different formats. They might begin with an executive summary of one or a few pages, include minimal background, focus on key findings, and conclude with policy implications, shifting methods and details about the data to an appendix. But both academic journal articles and policy papers share some things in common, for instance the necessity for clear writing, a well-organized structure, and the use of headings.

So what factors make up the genre of the academic journal article in sociology? While there is some flexibility, particularly for ethnographic work, academic journal articles tend to follow a fairly standard format. They begin with a “title page” that includes the article title (often witty and involving scholarly inside jokes, but more importantly clearly describing the content of the article); the authors’ names and institutional affiliations, an abstract , and sometimes keywords designed to help others find the article in databases. An abstract is a short summary of the article that appears both at the very beginning of the article and in search databases. Abstracts are designed to aid readers by giving them the opportunity to learn enough about an article that they can determine whether it is worth their time to read the complete text. They are written about the article, and thus not in the first person, and clearly summarize the research question, methodological approach, main findings, and often the implications of the research.

After the abstract comes an “introduction” of a page or two that details the research question, why it matters, and what approach the paper will take. This is followed by a literature review of about a quarter to a third the length of the entire paper. The literature review is often divided, with headings, into topical subsections, and is designed to provide a clear, thorough overview of the prior research literature on which a paper has built—including prior literature the new paper contradicts. At the end of the literature review it should be made clear what researchers know about the research topic and question, what they do not know, and what this new paper aims to do to address what is not known.

The next major section of the paper is the section that describes research design, data collection, and data analysis, often referred to as “research methods” or “methodology.” This section is an essential part of any written or oral presentation of your research. Here, you tell your readers or listeners “how you collected and interpreted your data” (Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault 2016:215). Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault suggest that the discussion of your research methods include the following:

- The particular approach to data collection used in the study;

- Any theoretical perspective(s) that shaped your data collection and analytical approach;

- When the study occurred, over how long, and where (concealing identifiable details as needed);

- A description of the setting and participants, including sampling and selection criteria (if an interview-based study, the number of participants should be clearly stated);

- The researcher’s perspective in carrying out the study, including relevant elements of their identity and standpoint, as well as their role (if any) in research settings; and

- The approach to analyzing the data.

After the methods section comes a section, variously titled but often called “data,” that takes readers through the analysis. This section is where the thick description narrative; the quotes, broken up by theme or topic, with their interpretation; the discussions of case studies; most data displays (other than perhaps those outlining a theoretical model or summarizing descriptive data about cases); and other similar material appears. The idea of the data section is to give readers the ability to see the data for themselves and to understand how this data supports the ultimate conclusions. Note that all tables and figures included in formal publications should be titled and numbered.

At the end of the paper come one or two summary sections, often called “discussion” and/or “conclusion.” If there is a separate discussion section, it will focus on exploring the overall themes and findings of the paper. The conclusion clearly and succinctly summarizes the findings and conclusions of the paper, the limitations of the research and analysis, any suggestions for future research building on the paper or addressing these limitations, and implications, be they for scholarship and theory or policy and practice.

After the end of the textual material in the paper comes the bibliography, typically called “works cited” or “references.” The references should appear in a consistent citation style—in sociology, we often use the American Sociological Association format (American Sociological Association 2019), but other formats may be used depending on where the piece will eventually be published. Care should be taken to ensure that in-text citations also reflect the chosen citation style. In some papers, there may be an appendix containing supplemental information such as a list of interview questions or an additional data visualization.

Note that when researchers give presentations to scholarly audiences, the presentations typically follow a format similar to that of scholarly papers, though given time limitations they are compressed. Abstracts and works cited are often not part of the presentation, though in-text citations are still used. The literature review presented will be shortened to only focus on the most important aspects of the prior literature, and only key examples from the discussion of data will be included. For long or complex papers, sometimes only one of several findings is the focus of the presentation. Of course, presentations for other audiences may be constructed differently, with greater attention to interesting elements of the data and findings as well as implications and less to the literature review and methods.

Concluding Your Work

After you have written a complete draft of the paper, be sure you take the time to revise and edit your work. There are several important strategies for revision. First, put your work away for a little while. Even waiting a day to revise is better than nothing, but it is best, if possible, to take much more time away from the text. This helps you forget what your writing looks like and makes it easier to find errors, mistakes, and omissions. Second, show your work to others. Ask them to read your work and critique it, pointing out places where the argument is weak, where you may have overlooked alternative explanations, where the writing could be improved, and what else you need to work on. Finally, read your work out loud to yourself (or, if you really need an audience, try reading to some stuffed animals). Reading out loud helps you catch wrong words, tricky sentences, and many other issues. But as important as revision is, try to avoid perfectionism in writing (Warren and Karner 2015). Writing can always be improved, no matter how much time you spend on it. Those improvements, however, have diminishing returns, and at some point the writing process needs to conclude so the writing can be shared with the world.

Of course, the main goal of writing up the results of a research project is to share with others. Thus, researchers should be considering how they intend to disseminate their results. What conferences might be appropriate? Where can the paper be submitted? Note that if you are an undergraduate student, there are a wide variety of journals that accept and publish research conducted by undergraduates. Some publish across disciplines, while others are specific to disciplines. Other work, such as reports, may be best disseminated by publication online on relevant organizational websites.

After a project is completed, be sure to take some time to organize your research materials and archive them for longer-term storage. Some Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols require that original data, such as interview recordings, transcripts, and field notes, be preserved for a specific number of years in a protected (locked for paper or password-protected for digital) form and then destroyed, so be sure that your plans adhere to the IRB requirements. Be sure you keep any materials that might be relevant for future related research or for answering questions people may ask later about your project.

And then what? Well, then it is time to move on to your next research project. Research is a long-term endeavor, not a one-time-only activity. We build our skills and our expertise as we continue to pursue research. So keep at it.

- Find a short article that uses qualitative methods. The sociological magazine Contexts is a good place to find such pieces. Write an abstract of the article.

- Choose a sociological journal article on a topic you are interested in that uses some form of qualitative methods and is at least 20 pages long. Rewrite the article as a five-page research summary accessible to non-scholarly audiences.

- Choose a concept or idea you have learned in this course and write an explanation of it using the Up-Goer Five Text Editor ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ), a website that restricts your writing to the 1,000 most common English words. What was this experience like? What did it teach you about communicating with people who have a more limited English-language vocabulary—and what did it teach you about the utility of having access to complex academic language?

- Select five or more sociological journal articles that all use the same basic type of qualitative methods (interviewing, ethnography, documents, or visual sociology). Using what you have learned about coding, code the methods sections of each article, and use your coding to figure out what is common in how such articles discuss their research design, data collection, and analysis methods.

- Return to an exercise you completed earlier in this course and revise your work. What did you change? How did revising impact the final product?

- Find a quote from the transcript of an interview, a social media post, or elsewhere that has not yet been interpreted or explained. Write a paragraph that includes the quote along with an explanation of its sociological meaning or significance.

The style or personality of a piece of writing, including such elements as tone, word choice, syntax, and rhythm.

A quotation, usually one of some length, which is set off from the main text by being indented on both sides rather than being placed in quotation marks.

A classification of written or artistic work based on form, content, and style.

A short summary of a text written from the perspective of a reader rather than from the perspective of an author.

Social Data Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Subject Research

- Qualitative Research Resources

- Writing Up Your Research

Qualitative Research Resources: Writing Up Your Research

Created by health science librarians.

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Qualitative Research Basics

- Special Topics

- Training Opportunities: UNC & Beyond

- Help at UNC

- Qualitative Software for Coding/Analysis

- Software for Audio, Video, Online Surveys

- Finding Qualitative Studies

- Assessing Qualitative Research

About this Page

Writing conventions for qualitative research, sample size/sampling:.

- Integrating Qualitative Research into Systematic Reviews

- Publishing Qualitative Research

- Presenting Qualitative Research

- Qualitative & Libraries: a few gems

- Data Repositories

Why is this information important?

- The conventions of good writing and research reporting are different for qualitative and quantitative research.

- Your article will be more likely to be published if you make sure you follow appropriate conventions in your writing.

On this page you will find the following helpful resources:

- Articles with information on what journal editors look for in qualitative research articles.

- Articles and books on the craft of collating qualitative data into a research article.

These articles provide tips on what journal editors look for when they read qualitative research papers for potential publication. Also see Assessing Qualitative Research tab in this guide for additional information that may be helpful to authors.

Belgrave, L., D. Zablotsky and M.A. Guadagno.(2002). How do we talk to each other? Writing qualitative research for quantitative readers . Qualitative Health Research , 12(10),1427-1439.

Hunt, Brandon. (2011) Publishing Qualitative Research in Counseling Journals . Journal of Counseling and Development 89(3):296-300.

Fetters, Michael and Dawn Freshwater. (2015). Publishing a Methodological Mixed Methods Research Article. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 9(3): 203-213.

Koch, Lynn C., Tricia Niesz, and Henry McCarthy. (2014). Understanding and Reporting Qualitative Research: An Analytic Review and Recommendations for Submitting Authors. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 57(3):131-143.

Morrow, Susan L. (2005) Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology ; Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(2):250-260.

Oliver, Deborah P. (2011) "Rigor in Qualitative Research." Research on Aging 33(4): 359-360.

Sandelowski, M., & Leeman, J. (2012). Writing usable qualitative health research findings . Qual Health Res, 22(10), 1404-1413.

Schoenberg, Nancy E., Miller, Edward A., and Pruchno, Rachel. (2011) The qualitative portfolio at The Gerontologist : strong and getting stronger. Gerontologist 51(3): 281-284.

Weaver-Hightower, M. B. (2019). How to write qualitative research . [e-book]

Sidhu, Kalwant, Roger Jones, and Fiona Stevenson (2017). Publishing qualitative research in medical journals. Br J Gen Pract ; 67 (658): 229-230. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp17X690821 PMID: 28450340

- This article is based on a workshop on publishing qualitative studies held at the Society for Academic Primary Care Annual Conference, Dublin, July 2016.

Smith, Mary Lee.(1987) Publishing Qualitative Research. American Educational Research Journal 24(2): 173-183.

Tong, Allison, Sainsbury, Peter, Craig, Jonathan ; Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups , International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 19, Issue 6, 1 December 2007, Pages 349–357, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 .

Tracy, Sarah. (2010) Qualitative Quality: Eight 'Big-Tent' Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry 16(10):837-51.

Because reviewers are not always familiar with qualitative methods, they may ask for explanation or justification of your methods when you submit an article. Because different disciplines,different qualitative methods, and different contexts may dictate different approaches to this issue, you may want to consult articles in your field and in target journals for publication. Additionally, here are some articles that may be helpful in thinking about this issue.

Bonde, Donna. (2013). Qualitative Interviews: When Enough is Enough . Research by Design.

Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. (2006) How Many Interviews are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 18(1): 59-82.

Hennink, Monique and Bonnie N. Kaiser. (2022) Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests . Social Science & Medicine 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523. Epub 2021 Nov 2. PMID: 34785096.

Morse, Janice M. (2015) "Data Were Saturated..." Qualitative Health Research 25(5): 587-88 . doi:10.1177/1049732315576699.

Nelson, J. (2016) "Using Conceptual Depth Criteria: Addressing the Challenge of Reaching Saturation in Qualitative Research." Qualitative Research, December. doi:10.1177/1468794116679873.

Patton, Michael Quinn. (2015) "Chapter 5: Designing Qualitative Studies, Module 30 Purposeful Sampling and Case Selection. In Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, Fourth edition, pp. 264-72. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. ISBN: 978-1-4129-7212-3

Small, Mario Luis. (2009) 'How Many Cases Do I Need?': On Science and the Logic of Case-Based Selection in Field-Based Research. Ethnography 10(1): 538.

Search the UNC-CH catalog for books about qualitative writing . Selected general books from the catalog are listed below. If you are a researcher at another institution, ask your librarian for assistance locating similar books in your institution's catalog or ordering them via InterLibrary Loan.

Oft quoted and food for thought

- Morse, J. M. (1997). " Perfectly healthy, but dead": the myth of inter-rater reliability. DOI:10.1177/104973239700700401 Editorial

- Silberzahn, R., Uhlmann, E. L., Martin, D. P., Anselmi, P., Aust, F., Awtrey, E., ... & Carlsson, R. (2018). Many analysts, one data set: Making transparent how variations in analytic choices affect results. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychologi

- << Previous: Assessing Qualitative Research

- Next: Integrating Qualitative Research into Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 23, 2024 11:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/qual

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE: Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2024 1:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to Write an Effective Results Section

Affiliation.

- 1 Rothman Orthopaedics Institute, Philadelphia, PA.

- PMID: 31145152

- DOI: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000845

Developing a well-written research paper is an important step in completing a scientific study. This paper is where the principle investigator and co-authors report the purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions of the study. A key element of writing a research paper is to clearly and objectively report the study's findings in the Results section. The Results section is where the authors inform the readers about the findings from the statistical analysis of the data collected to operationalize the study hypothesis, optimally adding novel information to the collective knowledge on the subject matter. By utilizing clear, concise, and well-organized writing techniques and visual aids in the reporting of the data, the author is able to construct a case for the research question at hand even without interpreting the data.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Rules to be adopted for publishing a scientific paper. Picardi N. Picardi N. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:1-3. Ann Ital Chir. 2016. PMID: 28474609

- How to Write Effective Discussion and Conclusion Sections. Makar G, Foltz C, Lendner M, Vaccaro AR. Makar G, et al. Clin Spine Surg. 2018 Oct;31(8):345-346. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000687. Clin Spine Surg. 2018. PMID: 29979216

- The rites of writing papers: steps to successful publishing for psychiatrists. Brakoulias V, Macfarlane MD, Looi JC. Brakoulias V, et al. Australas Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;23(1):32-6. doi: 10.1177/1039856214560180. Epub 2014 Dec 2. Australas Psychiatry. 2015. PMID: 25469001

- How to write a research paper. Alexandrov AV. Alexandrov AV. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(2):135-8. doi: 10.1159/000079266. Epub 2004 Jun 23. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004. PMID: 15218279 Review.

- How to write an original radiological research manuscript. Bannas P, Reeder SB. Bannas P, et al. Eur Radiol. 2017 Nov;27(11):4455-4460. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4879-8. Epub 2017 Jun 14. Eur Radiol. 2017. PMID: 28616726 Free PMC article. Review.

- Essential Guide to Manuscript Writing for Academic Dummies: An Editor's Perspective. Aga SS, Nissar S. Aga SS, et al. Biochem Res Int. 2022 Sep 1;2022:1492058. doi: 10.1155/2022/1492058. eCollection 2022. Biochem Res Int. 2022. PMID: 36092536 Free PMC article. Review.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.74(8); 2010 Oct 11

Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research

The purpose of this paper is to help authors to think about ways to present qualitative research papers in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education . It also discusses methods for reviewers to assess the rigour, quality, and usefulness of qualitative research. Examples of different ways to present data from interviews, observations, and focus groups are included. The paper concludes with guidance for publishing qualitative research and a checklist for authors and reviewers.

INTRODUCTION

Policy and practice decisions, including those in education, increasingly are informed by findings from qualitative as well as quantitative research. Qualitative research is useful to policymakers because it often describes the settings in which policies will be implemented. Qualitative research is also useful to both pharmacy practitioners and pharmacy academics who are involved in researching educational issues in both universities and practice and in developing teaching and learning.

Qualitative research involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data that are not easily reduced to numbers. These data relate to the social world and the concepts and behaviors of people within it. Qualitative research can be found in all social sciences and in the applied fields that derive from them, for example, research in health services, nursing, and pharmacy. 1 It looks at X in terms of how X varies in different circumstances rather than how big is X or how many Xs are there? 2 Textbooks often subdivide research into qualitative and quantitative approaches, furthering the common assumption that there are fundamental differences between the 2 approaches. With pharmacy educators who have been trained in the natural and clinical sciences, there is often a tendency to embrace quantitative research, perhaps due to familiarity. A growing consensus is emerging that sees both qualitative and quantitative approaches as useful to answering research questions and understanding the world. Increasingly mixed methods research is being carried out where the researcher explicitly combines the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the study. 3 , 4

Like healthcare, education involves complex human interactions that can rarely be studied or explained in simple terms. Complex educational situations demand complex understanding; thus, the scope of educational research can be extended by the use of qualitative methods. Qualitative research can sometimes provide a better understanding of the nature of educational problems and thus add to insights into teaching and learning in a number of contexts. For example, at the University of Nottingham, we conducted in-depth interviews with pharmacists to determine their perceptions of continuing professional development and who had influenced their learning. We also have used a case study approach using observation of practice and in-depth interviews to explore physiotherapists' views of influences on their leaning in practice. We have conducted in-depth interviews with a variety of stakeholders in Malawi, Africa, to explore the issues surrounding pharmacy academic capacity building. A colleague has interviewed and conducted focus groups with students to explore cultural issues as part of a joint Nottingham-Malaysia pharmacy degree program. Another colleague has interviewed pharmacists and patients regarding their expectations before and after clinic appointments and then observed pharmacist-patient communication in clinics and assessed it using the Calgary Cambridge model in order to develop recommendations for communication skills training. 5 We have also performed documentary analysis on curriculum data to compare pharmacist and nurse supplementary prescribing courses in the United Kingdom.

It is important to choose the most appropriate methods for what is being investigated. Qualitative research is not appropriate to answer every research question and researchers need to think carefully about their objectives. Do they wish to study a particular phenomenon in depth (eg, students' perceptions of studying in a different culture)? Or are they more interested in making standardized comparisons and accounting for variance (eg, examining differences in examination grades after changing the way the content of a module is taught). Clearly a quantitative approach would be more appropriate in the last example. As with any research project, a clear research objective has to be identified to know which methods should be applied.

Types of qualitative data include:

- Audio recordings and transcripts from in-depth or semi-structured interviews

- Structured interview questionnaires containing substantial open comments including a substantial number of responses to open comment items.

- Audio recordings and transcripts from focus group sessions.

- Field notes (notes taken by the researcher while in the field [setting] being studied)

- Video recordings (eg, lecture delivery, class assignments, laboratory performance)

- Case study notes

- Documents (reports, meeting minutes, e-mails)

- Diaries, video diaries

- Observation notes

- Press clippings

- Photographs

RIGOUR IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is often criticized as biased, small scale, anecdotal, and/or lacking rigor; however, when it is carried out properly it is unbiased, in depth, valid, reliable, credible and rigorous. In qualitative research, there needs to be a way of assessing the “extent to which claims are supported by convincing evidence.” 1 Although the terms reliability and validity traditionally have been associated with quantitative research, increasingly they are being seen as important concepts in qualitative research as well. Examining the data for reliability and validity assesses both the objectivity and credibility of the research. Validity relates to the honesty and genuineness of the research data, while reliability relates to the reproducibility and stability of the data.

The validity of research findings refers to the extent to which the findings are an accurate representation of the phenomena they are intended to represent. The reliability of a study refers to the reproducibility of the findings. Validity can be substantiated by a number of techniques including triangulation use of contradictory evidence, respondent validation, and constant comparison. Triangulation is using 2 or more methods to study the same phenomenon. Contradictory evidence, often known as deviant cases, must be sought out, examined, and accounted for in the analysis to ensure that researcher bias does not interfere with or alter their perception of the data and any insights offered. Respondent validation, which is allowing participants to read through the data and analyses and provide feedback on the researchers' interpretations of their responses, provides researchers with a method of checking for inconsistencies, challenges the researchers' assumptions, and provides them with an opportunity to re-analyze their data. The use of constant comparison means that one piece of data (for example, an interview) is compared with previous data and not considered on its own, enabling researchers to treat the data as a whole rather than fragmenting it. Constant comparison also enables the researcher to identify emerging/unanticipated themes within the research project.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH