What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the Princeton University Essays 2024-2025

Princeton has two prompts that are required for all applicants, as well as three short-answer questions that give you just 50 words for your response. There is one other prompt, focused on your academic interests, which will be different depending on if you are applying for a Bachelor of Arts or a Bachelor of Science in Engineering. Finally, Princeton has a somewhat unusual requirement—a graded paper to be submitted with your application.

Because Princeton is one of the most competitive schools in the country, you want to be sure that each of your essays, plus the graded paper you submit, will help you stand out from other applicants who have superb academic and extracurricular resumes. In this post, we’ll break down how you should approach each prompt so you can be sure that your essays maximize your chances of acceptance.

Read these Princeton essay examples written by real students to inspire your writing!

Princeton University Supplemental Essay Prompts

All applicants.

Prompt 1: Princeton values community and encourages students, faculty, staff and leadership to engage in respectful conversations that can expand their perspectives and challenge their ideas and beliefs. As a prospective member of this community, reflect on how your lived experiences will impact the conversations you will have in the classroom, the dining hall or other campus spaces. What lessons have you learned in life thus far? What will your classmates learn from you? In short, how has your lived experience shaped you? (500 words)

Prompt 2: Princeton has a longstanding commitment to understanding our responsibility to society through service and civic engagement. How does your own story intersect with these ideals? (250 words)

More About You Prompts (50 words each)

Please respond to each question in 50 words or fewer. There are no right or wrong answers. Be yourself!

What is a new skill you would like to learn in college, what brings you joy, what song represents the soundtrack of your life at this moment.

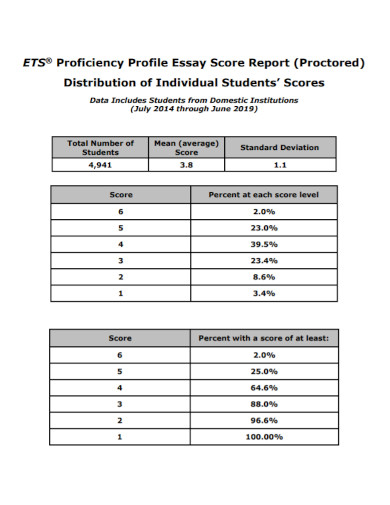

Graded Paper: Princeton requires you to submit a graded written paper as part of your application. You may submit this material now or any time before the application deadline. If you choose not to upload the required paper at this time, you may mail, e-mail, or upload your paper through the applicant portal. Detailed instructions for our graded paper requirement can be found here . (1-2 pages)

Bachelor of Arts Applicants

As a research institution that also prides itself on its liberal arts curriculum, princeton allows students to explore areas across the humanities and the arts, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. what academic areas most pique your curiosity, and how do the programs offered at princeton suit your particular interests (250 words), bachelor of science in engineering applicants, please describe why you are interested in studying engineering at princeton. include any of your experiences in, or exposure to engineering, and how you think the programs offered at the university suit your particular interests. (250 words), all applicants, prompt 1, princeton values community and encourages students, faculty, staff and leadership to engage in respectful conversations that can expand their perspectives and challenge their ideas and beliefs. as a prospective member of this community, reflect on how your lived experiences will impact the conversations you will have in the classroom, the dining hall or other campus spaces. what lessons have you learned in life thus far what will your classmates learn from you in short, how has your lived experience shaped you (500 words).

Brainstorming your topic:

This prompt essentially boils down to its last sentence—how has your lived experience shaped you? Now, that is an incredibly open-ended question, which you could use as a road into just about any topic. That freedom, combined with a pretty long word count, means that the brainstorming process is crucial to writing a strong response. If you don’t already have a clear sense of what you want to say, your essay may end up all over the place.

One good way to focus your brainstorming is through the prompt’s attention to conversations. You’re likely going to share similar things with your peers at Princeton as you do with your friends and family right now. So, questions like the following may help you start figuring out what you want to write about:

- Which stories do you tell most often?

- When you meet someone new, what are some of the first things you usually talk about?

- When you give advice, which experiences do you draw on?

Hopefully, thinking through these slightly more targeted questions will give you some ideas about what you might want to include in your essay. Remember, you have space to work with here, so you don’t have to zero in on just one thing like you would for a shorter prompt. That being said, you also want to make sure that your essay is organized, so you also don’t want to be trying to fit in ten different things.

Rather, select one experience, or 2-4 experiences that are clearly related , to use as the foundation for your essay. Once you have a general structure for your essay, you can then connect bigger picture takeaways to it, which ensures that your essay is cohesive.

For example, maybe you choose to focus your essay on an ice fishing trip you took with your grandfather, and the lessons you learned about patience and the value of cross-generational relationships. Alternatively, you could write about your tradition of getting an owl-themed trinket anywhere you go on vacation, and how this small, seemingly silly routine has given you something consistent across different periods of your life.

Tips for writing your essay:

As noted above, for this prompt, brainstorming is more than half the battle. If you have a clear game plan before you start writing, actually getting the words down will hopefully be more about finding the right phrasing and crafting smooth transitions than actually generating content.

You do want to make sure that, like in any college essay, you’re utilizing the “show, don’t tell” strategy. In other words, rather than telling something to your reader directly, describe a moment or situation that illustrates the point you’re trying to make. To see the benefits of this approach, compare the following two excerpts from hypothetical essays:

Excerpt 1: “For as long as I can remember, I’ve collected owl trinkets on family vacations. In 2009, I got my first one, a ceramic burrowing owl from Tucson, Arizona. The most recent addition to my collection was a dense, bronze owl from Athens, who I was especially excited about since owls are the symbol of Athena, the patron goddess of that city.”

Excerpt 2: “As my family enters the small, dimly lit shop at the end of one of Athens’s many winding streets, my eyes immediately lock onto the shelves upon shelves of owls. Huge, marble ones that cost hundreds of euros, and tiny, wooden ones as spindly as a toothpick. After much deliberation, I select a dense bronze fellow who is barely an inch high. I can already envision how he’ll look on my desk at home, lined up next to all the other owls I’ve collected over the years.”

These two excerpts give us basically the same information, but the first presents it to us in a very dry, factual way. The second, on the other hand, drops us right next to the writer as they pick out their latest owl, and includes vivid descriptions that make this excerpt much more engaging to read.

Particularly since you have 500 words at your disposal, you should see this essay as an opportunity to show off your creative writing ability with a stylistic flourish here and there. That being said, in your early drafts, don’t focus on this kind of finer detail. Make sure you have a personal, informative, cohesive essay first, then take the time to add the cherries on top later.

Mistakes to avoid:

As we hinted at in the brainstorming section above, the biggest potential pitfall with this essay is that between the open-ended prompt and the high word count, you may end up adrift, without any clear focus point to anchor you. To avoid that happening, don’t just rattle off a bunch of vague, Hallmark card lessons. Instead, follow the strategies laid out in the previous two sections to ensure that the points you make are clearly connected to your own personal experiences.

The other thing you want to be sure to avoid is repeating information that can already be found elsewhere in your application, namely in your Common App essay. If you already wrote about your owl collection there, you want to pick something else to focus on here. You only get so many opportunities to share your personality with Princeton’s admissions officers, so don’t waste one by telling them things they already know.

All Applicants, Prompt 2

Princeton has a longstanding commitment to understanding our responsibility to society through service and civic engagement. how does your own story intersect with these ideals (250 words).

Keep in mind that the keyword is “story”—this prompt is not an invitation to list all of your achievements in community service as you will on your resume. Rather, Princeton is asking for a deeply held part of your identity through which you’re motivated to perform civic engagement and service. We’ll cover some specific points below, but we also have a detailed blog post on writing service essays that you’ll find useful as well.

Also note that this prompt is a bit more focused on Princeton itself, so devote about 30-40% of your writing to specific programs at Princeton that align with your interests. We always recommend spending a good hour snooping around a college’s website, clicking through links and looking at the different clubs, classes, programs, institutes, and communities. Also check out Princeton’s webpages for service and civic engagement .

A trusty table can be of good help while you brainstorm:

Focus on one interest or concern. Here, less is more—focusing on one key experience or aspect of your identity shows more thought and effort than copying and pasting several experiences. And for this prompt, it’s most effective to focus on the service work about which you can write the most and or to which you can relate the most.

For instance, a student wanting to study literature might help make sandwiches for charity every month, but she probably has a more immediate connection to being a weekly reader and Bible study leader at her church.

Don’t turn your brain on autopilot or regurgitate the prompt. This prompt uses a lot of “admissions-speak,” which should serve as a signpost to direct you, not as suggested wording to include in your response.

“Intersect,” for example, has become an important—but increasingly robotic—buzzword in recent years. Try to avoid repeating it, and instead opt for words with more emotional resonance: “find a home [at Princeton],” “delve into the research [at Princeton],” etc. The same goes for “service” and “civic engagement”—repeat them too much and you’ll start to sound like you’re using the prompt as a crutch. Besides, there are more vivid words at your disposal.

As always, be specific. Pick not just a broad issue (“helping the homeless”), but also a subset of the issue that actually seems manageable (“making sure that the homeless have access to Internet and library services”). From there, look for potential classes offered at Princeton, and student organizations involved in similar missions. It may be worth citing current student activism projects you find on Princeton’s website, and discussing how those same opportunities would allow you to apply your skills in the best way for you personally.

All Applicants, More About You Prompts (50 words each)

“There are no right or wrong answers.” (Alexa, play “Why You Always Lying?”)

There is a wrong answer, and it’s a category—“boring.” In fact, the more unique and genuine your answer is, the more you can break away as a contender. And because you have such a short word limit, you can even add a little mystery. This is the right place for that, too—it’s the end of your application, and a thought-provoking or fascinating answer will just remind your reader that “We have to interview this applicant to find out more.”

For example, a lackluster answer to the “soundtrack” question might be sensible and logical, but flat: “Since I’ve been sick and stuck in quarantine, ‘Circles’ by Post Malone summarizes my repetitive experience.” Well, it’s passable as small talk. But it’s self-contained and doesn’t elicit any curiosity.

A better answer will entertain, provoke a chuckle, frighten, intrigue —any verb you want your reader to have. Recontextualize a song. Pick a weird one. Send your reader to YouTube to look it up. For example, “Early in his career, David Bowie wrote a song about being stalked by a magical gnome . It is friendly, but harasses Bowie. Does it come in peace, or with malice? It is, like both, inescapable. Its voice plays in my dreams. I fear gnomes now.” The weirdness there commands attention.

You can also demonstrate uniqueness by redefining or recontextualizing a word in the prompt. For example, you could write about a niche type of joy, like schadenfreude (well, maybe not that one), fear/excitement, or watching fire. You could redefine “song” to include birdsong, or the indistinct chatter, easy listening music, and whirring of coffee machines at your favorite coffee shop.

A word on the “skill” question: it may be helpful to address a shortcoming or skill gap, then cite the skill and how it will improve your life. Doing so can prove that you’re not going for pure quirkiness or trying, superficially, to be a Manic Pixie Dream Freshman. For example, “juggling!!!” itself might seem a little vacuous, but can be easily deepened by expansion: “juggling as part of the team would help me overcome my fear of performing and presenting in front of crowds.”

Overall, use these “More About You” questions to showcase another part of your story, personality, or character that you didn’t have the chance to showcase before. When answering this prompt, it can also be helpful to astral-project yourself into another student or someone who’s assessing you as a potential friend.

With this outside perspective in mind , look over your answers: would you want to grab lunch or share a dorm with the person who has written them? Would you be inspired to befriend the engineering major who answers the first “More About You” question with yet another example of her love of engineering? Or would you rather befriend the engineering major who answers the same question with her love for candlemaking and Dolly Parton? The main point is that answering these prompts successfully takes a degree of self-awareness and quirkiness.

All Applicants, Graded Paper

Princeton requires you to submit a graded written paper as part of your application. you may submit this material now or any time before the application deadline. if you choose not to upload the required paper at this time, you may mail, e-mail, or upload your paper through the applicant portal. detailed instructions for our graded paper requirement can be found here . (1-2 pages).

Unlike with the other essays, Princeton isn’t assessing your personality and interests from the graded written paper you’re submitting. Rather, this paper will give the admissions officers insight into your academic capabilities as a student. While the admissions officers can already see your physical grades and reports from teachers, this is a unique chance for you to showcase your talents for conveying an academic idea in writing—a crucial skill you’ll need in college and in life.

We have an entire post dedicated to the requirements for the paper, tips for choosing your paper, and instructions for submitting it. You can read it here !

Bachelor of Arts Applicants, Prompt 1

This essay is only required for those who have indicated on their application an interest in pursuing a Bachelor of Arts.

This prompt somewhat fits into the “Why This Major?” essay archetype . The main difference is that rather than being asked about one specific major, you’re being asked about your general academic interests. This prompt is intended to get a sense of your passion and thirst for knowledge. Princeton only wants to admit the most intellectually curious students, so your essay should convey your academic passions and how you’ll explore them at Princeton.

You want to be sure your essay reveals meaningful emotional reasons for wanting to pursue the fields you want to explore. Asking yourself these questions will help you explain why you’re interested in your chosen topic(s):

- What are specific examples of concepts or things that you enjoy in this field?

- What positive skills or traits are exemplified by this field?

- How might majoring in/studying this topic serve your life and/or career goals?

- What is your state of mind or the emotional experience you have when you explore this topic? Why do you find that state or experience appealing?

Note: The above questions are phrased in a singular way, but the prompt does allow you to talk about multiple areas of study. If you’re interested in multiple things, you should consider writing about them in this essay. Bear in mind the 250-word limit, though, so don’t get too carried away with the number of areas you choose.

After you’ve figured out why you’re interested in your chosen field(s), you can start writing. A good essay will introduce the field(s), articulate your core reasons as to why you’re interested in the field (ideally through anecdotes or specific examples from inside and outside the classroom), and explain how this field might help you in the future.

Here are some examples of responses that include all of these elements:

1) A student who is interested in geosciences might write about how he has grown up by the beach and spent his whole life surfing. He could describe how he became fascinated with how the largest waves he loved to surf were formed.

He might then discuss the independent research he’s done on the tectonic plates, and his study of topographical maps of the Pacific Ocean floor to find the best locations for waves in California. Finally, he would explain how understanding the physics, chemistry, and biology of the ocean can help him predict areas at risk of climate crises as a future environmental consultant.

2) A student who is interested in politics could write about her experience volunteering for her local representative’s campaign. She could describe how she offered to run the social media accounts for her representative since she has an eye for graphic design.

Through attending strategy meetings, reading policy briefs, and speaking to constituents, the student got an inside look at what it means to be a representative, which sparked her interest in politics. After her experience in local government, she got very excited to learn the intricacies of national government and public relations in her classes. She feels that these classes will prepare her to be a press secretary on the Hill one day.

3) A student who is interested in architecture might talk about the trip he took to Barcelona, where he saw the most unique architecture he’s ever seen. After his trip, he researched the architects who created some of the structures he saw. His research inspired his portfolio in art class, in which he painted a collection of houses inspired by the Barcelona style. He hopes to learn more about architectural fundamentals so he can turn his creative designs into practical structures.

Since the prompt asks explicitly about the programs offered at Princeton, make sure you include specific opportunities unique to Princeton that make it the perfect place to pursue this field. You could talk about things like these:

- The specific approach the University takes in teaching specific fields (perhaps you are fascinated by approaching biology from an evolutionary standpoint in the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology major)

- Classes or professors you are excited to have (e.g., Philosophy of Mind , or Turning Points in European Culture )

- Extracurricular opportunities that align with your interests (research projects, study abroad programs, and community service organizations, etc.)

Remember, name-dropping will get you nothing! For every resource you mention, you should have a concrete explanation as to what you hope to gain or contribute when you engage with the resource. Also, make every effort to avoid praising a subject without explaining its significance to you personally. And finally, don’t talk about how you might want to pursue a subject because it pays well or because your parents want you to pursue it.

Bachelor of Science in Engineering Applicants, Prompt 1

This essay is only required for those who have indicated on their application an interest in pursuing a Bachelor of Science in Engineering.

The key here is to be specific ; an implicit aspect of this question is “Why Princeton engineering? What makes Princeton’s engineering program different from other programs? Why would this be a better fit for you than any other?” In essence, this is sort of like the common “Why This Major?” prompt , but it’s referring to a specialized program rather than a specific major.

Rather than vaguely discussing the reasons that Princeton’s engineering program is something you wish to be a part of, mention specific resources and appeal to the philosophy of an engineering education. For instance, if there’s a particular class that interests you, don’t be afraid to directly mention it and connect the class back to your overall interest in engineering.

Extracurricular programs are another area you should definitely mention. If you’re passionate about sustainability, you could discuss your interest in the Princeton chapter of Engineers Without Borders , commenting on how you will use your membership to promote sustainable engineering. If you enjoy working with kids, perhaps Princeton Engineering Education for Kids is more appealing. No matter your interests, be sure to mention a club or organization that could allow you to pursue these interests outside of the classroom.

If you have a preferred area of specialization, such as bioengineering or chemical engineering, it would be great if you’re able to tie this back to your current passions or activities. Maybe you’re already involved in an organization at your current school that deals with these more specialized areas of engineering. If so, make sure to emphasize this, as that would allow your passion to shine through and showcase previous relevant experience.

Be warned, however, that listing all your engineering related activities can make your essay sound like a resume. Rather than simply providing a list, connect each activity to each other in order to construct a more cohesive essay. Make sure that any change in topic flows smoothly from one to the next to avoid transforming your essay into a laundry list of your achievements.

Another direction that you might take when discussing previous engineering experience is to discuss your state of mind when partaking in these activities. Perhaps working on complex engineering problems gets your adrenaline pumping, or maybe you find it quite therapeutic and relaxing. It’s always a good idea to show the admissions officers how you feel when partaking in subjects or activities you’re passionate about.

As always, remember to show Princeton another piece of yourself by highlighting your passions, interests, and goals, and by connecting these back to Princeton’s academic environment.

There are a few things you should avoid when writing this essay:

- First, don’t simply praise Princeton for being a prestigious institution. It’s not a bad thing to be nice, but you should save the limited space you have for substantive, meaningful reasons.

- Second, as mentioned before, don’t simply list your experiences without elaborating on their importance. You don’t want your essay to read more like a list than an essay.

- Finally, don’t state that you want to study engineering for the money or because your parents are forcing you to. These are seen as insincere reasons that won’t make you the most desirable applicant.

Where to Get Your Princeton Essays Edited For Free

Do you want feedback on your Princeton essays? After rereading your essays countless times, it can be difficult to evaluate your writing objectively. That’s why we created our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

Need feedback faster? Get a free, nearly-instantaneous essay review from Sage, our AI tutor and advisor. Sage will rate your essay, give you suggestions for improvement, and summarize what admissions officers would take away from your writing. Use these tools to improve your chances of acceptance to your dream school!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Expository Essay: 3 Building Blocks to Propose an Idea and Defend It

by Dixie-Ann Belle | 0 comments

If you saw the words “expository essay” on a writing assignment, would your mind draw a blank? Would you immediately feel as if you had stumbled into unexplored territory?

Well there's good news.

This post is written by guest writer Dixie-Ann Belle. You can learn more about Dixie-Anne at the end of this article. Welcome Dixie-Ann!

You might not realize it, but chances are this is not your first encounter with this type of essay. Once you have been writing essays in academic environments, you have probably already worked on expository writing.

In this article, I hope to help you recognize this essay type and understand the expository essay outline. Comprehending the building blocks is instrumental in knowing how to construct an exceptional expository essay.

Lay a Strong Foundation

Over the years, I have taught and tutored college students one on one as they write academic essays, in face to face classrooms and online, and I have noticed a pattern. They often approach essays in one of two ways.

Some consider them with apprehension and are fearful of making mistakes. Others feel confident that they have written many essays before and think they have already mastered expository writing.

Interestingly, it's the latter who often end up the most shaken when they realize that they are not as familiar as they think with this type of writing.

What I hope to instill in my students is that they should not feel intimidated whatever their situation or essay assignment.

I encourage them to make sure they understand the foundations of the expository essay structure. I try to get them to grasp the basic blocks that need to be there, and once they do, they have a good chance of crafting a substantial piece of writing.

What is an Expository Essay?

Students are typically assigned one of at least four types of essays: the persuasive/argumentative essay, the descriptive essay, the technical essay, or the expository essay.

Writing an expository essay is one of the most important and valuable skills for you to master.

An expository essay definition according to the Purdue Online Writing Lab:

The expository essay is a genre of essay that requires the student to investigate an idea, evaluate evidence, expound on the idea, and set forth an argument concerning that idea in a clear and concise manner.

Keep in mind that your expository writing centers on giving your reader information about a given topic or process. Your goal is to inform, describe, or define the subject for your readers.

As you work to achieve this, your essay writing must be formal, objective, and concise. No matter what your discipline, it's almost guaranteed that you will be required to write this common type essay one day.

Some expository essay examples could include:

- Define the term ‘democracy'

- Compare and contrast the benefits of cable television vs streaming

- Outline the process that generates an earthquake

- Classify the different types of tourism

- Outline the aspects of a good fitness program

The possibilities are endless with expository writing, and it can cover a wide variety of topics and specialties.

3 Building Blocks of a Great Expository Essay

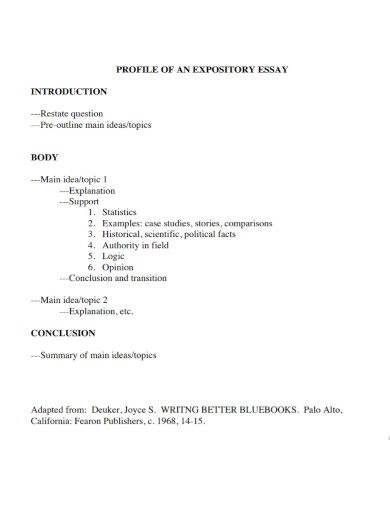

To make sure you're on the right track with this type of paper, it helps to understand the three building blocks of the expository essay format and how to apply them to the final expository essay structure .

1. Write an introduction

Most students know that an introductory paragraph should grab the interest of the reader. However, they might not realize that it should also provide context for the essay topic.

Ask yourself : What are you talking about in this essay? Why is this topic important? Some background details could help to establish the subject for your reader.

For example:

If you were writing an essay on the impact smartphones have on society, you might want to start with some information on the evolution of smartphones, the number of smartphones in society, the way people use the phones and more.

The introduction should start off with general information.

You then work your way down to the more specific and principal part of your introduction and the crown of your whole essay, the thesis statement.

What is the thesis statement?

Your thesis statement states in concise language what this essay is going to be about. It is one clear sentence which expresses the subject and the focus of this piece of writing. If there is a prompt, the thesis statement should directly answer that prompt.

Our smart phones topic might create a thesis statement like: Smart phones have many positive impacts for adults in the business world.

Right away the reader has some idea of what's ahead.

2. Write your body paragraphs

With your thesis statement clear in your mind and your introduction setting the scene, it is time to write your body paragraphs.

Each body paragraph contains supporting information including factual evidence for your essay topic. Each paragraph should each focus on one idea.

Depending on your word count and the teacher requirements, you can write any number of body paragraphs, but there are usually at least three for a basic five paragraph essay.

Each body paragraph should start with a topic sentence. A topic sentence is one single statement that explains the point of the paragraph. It directly refers to your thesis statement and tells you what the body paragraph is going to be about.

Remember our smart phone thesis statement? You need something that will relate to that thesis sentence and will alert the reader to what is to come.

Here's one possibility:

Smart phones can help increase productivity for professional adults.

This topic sentence not only reminds us that you are talking about positive impacts for adults with smart phones, it now shows us what the following paragraph will cover.

The best body paragraphs will go on to include different types of details, all of which would support your topic sentence. A good abbreviation to encapsulate the different details is spelt TEEES.

The TEEES Body Paragraph Structure

Let's break down this abbreviation and explore the types of details you'll need in your body paragraphs

T: Topic sentence

You'll begin with your topic sentence establishing the purpose of this paragraph. We'll use our example from above:

Smartphones can help increase productivity for professional adults.

E: Explanation

This is where you expand on your topic and include additional supportive information.

If you were talking about smartphones and productivity, maybe you could mention what elements of the smartphone make it optimal for productivity.

E: Evidence

This is the information from reputable sources you researched for your topic. Here's where you can talk about all the information you have discovered from experts who have carefully studied this subject.

For our smartphone essay, perhaps you could mention a quote from a technology reporter who has been following the rise of smartphones for years.

E: Examples

This would be concrete subject matter to support your point.

Maybe here you can list some of the smartphone apps which have proven to increase productivity in the workplace.

S: Significant/Summarizing sentence

This is the last sentence in the body paragraph which summarizes your point and ends this part of your essay. There should be no doubt in the reader's mind that you have finished talking about your topic, and you are moving on to another in the next paragraph. Here's how we could conclude this paragraph on smartphones and productivity:

Smartphones have transformed the productivity of the modern workforce.

3. Write the conclusion

Once you have written your body paragraphs, you're in the home stretch. You have presented all of your points and supported them with the appropriate subject matter. Now you need to conclude.

A lot of students are confused by conclusions. Many of them have heard different rules about what is supposed to be included.

One of the main requirements to keep in mind when ending an expository essay is that you do not add new information.

This is not the time to throw in something you forgot in a previous body paragraph. Your conclusion is supposed to give a succinct recap of the points that came before.

Sometimes college students are instructed to re-state the thesis, and this puzzles them. It doesn't mean re-writing the thesis statement word for word. You should express your thesis statement in a new way.

For example, here's how you could approach the conclusion for our smartphone essay.

You've come up with three points to support your thesis statement, and you've explored these three points in your body paragraphs. After brainstorming, you might decide the benefits of smartphones in the workplace are improved productivity, better communication, and increased mobility.

Your conclusion is the time to remind your reader of these points with concise language. Your reader should be able to read the conclusion alone and still come away with the basic ideas of your essay.

Plan Your Essay Based on an Expository Essay Outline

While writing fiction, it is sometimes okay to “pants” it and just leap into writing your story.

When writing essays in academia, this is rarely a good idea. Planning your essay helps organize your ideas, helps you refine many of your points early on and saves time in the long run.

There are lots of great brainstorming techniques you can use to get your ideas together, but after that, it's time to create a topic to sentence outline.

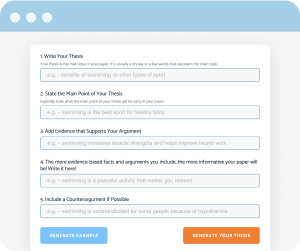

There are three steps to creating your topic to sentence essay outline.

- Develop a powerful thesis statement. Remember, this is the overarching idea of your entire essay, so you have completed a significant step once you have one done.

- Come up with the ideas you would like to support your thesis statement.

- Based on your points, craft your topic sentences.

Here is an example of a topic to sentence outline:

Having these important foundation details completed is a great way to develop your essay as you build on each part. It is also an effective method to make sure you are on the right track.

Depending on your instructor (or tutor, if you have one), you can show your outline to them to get feedback before you launch into your entire essay.

Even if you don't have anyone to provide a critique, the outline can make it easier to revise how you will approach the rest of your paragraph essay.

You now have some firm foundations to help you as you construct your expository essay.

How do you organize an expository essay? Let us know in the comments .

Take fifteen minutes to practice writing your own expository essay.

First, choose an expository writing assignment topic. If you can't think of one, use one of the expository essay examples below .

- What are the nutritional elements of a healthy breakfast?

- What are some of the most influential types of music?

- Compare and contrast the benefits of electric and gas cars.

- What are the major steps to planning a stress-free vacation?

- How do smartphones affect mental health?

- Define true love.

Craft a thesis statement about your topic. Then, write three topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

With the time you have left, start writing your essay. You might be surprised how much you can write in fifteen minutes when you have a clear outline for your essay!

When your time is up, share your outline and your essay in the Pro Practice Workshop here . After you post, please be sure to give feedback to your fellow writers.

Happy writing!

Dixie-Ann Belle

Since she started scribbling stories in her notebooks as a child, Dixie-Ann Belle has been indulging her love of well crafted content. Whether she is working as a writing teacher and tutor or as a freelance writer, editor and proofreader, she enjoys helping aspiring writers develop their work and access their creativity.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Best Resources for Writers Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How to Edit Your Own Writing

Writing is hard, but don’t overlook the difficulty — and the importance — of editing your own work before letting others see it. Here’s how.

By Harry Guinness

The secret to good writing is good editing. It’s what separates hastily written, randomly punctuated, incoherent rants from learned polemics and op-eds, and cringe-worthy fan fiction from a critically acclaimed novel. By the time this article is done, I’ll have edited and rewritten each line at least a few times. Here’s how to start editing your own work.

Understand that what you write first is a draft

It doesn’t matter how good you think you are as a writer — the first words you put on the page are a first draft. Writing is thinking: It’s rare that you’ll know exactly what you’re going to say before you say it. At the end, you need, at the very least, to go back through the draft, tidy everything up and make sure the introduction you wrote at the start matches what you eventually said.

My former writing teacher, the essayist and cartoonist Timothy Kreider, explained revision to me: “One of my favorite phrases is l’esprit d’escalier, ‘the spirit of the staircase’ — meaning that experience of realizing, too late, what the perfect thing to have said at the party, in a conversation or argument or flirtation would have been. Writing offers us one of the rare chances in life at a do-over: to get it right and say what we meant this time. To the extent writers are able to appear any smarter or wittier than readers, it’s only because they’ve cheated by taking so much time to think up what they meant to say and refining it over days or weeks or, yes, even years, until they’ve said it as clearly and elegantly as they can.”

The time you put into editing, reworking and refining turns your first draft into a second — and then into a third and, if you keep at it, eventually something great. The biggest mistake you can make as a writer is to assume that what you wrote the first time through was good enough.

Now, let’s look at how to do the actual editing.

Watch for common errors

Most writing mistakes are depressingly common; good writers just get better at catching them before they hit the page. If you’re serious about improving your writing, I recommend you read “The Elements of Style” by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White, a how-to guide on writing good, clear English and avoiding the most common mistakes. “ Politics and the English Language ” by George Orwell is also worth studying if you want to avoid “ugly and inaccurate” writing.

Some of the things you’ll learn to watch for (and that I have to fix all the time in my own writing) are:

Overuse of jargon and business speak . Horrible jargon like “utilize,” “endeavor” or “communicate” — instead of “use,” “try” or “chat” — creep in when people (myself included) are trying to sound smart. It’s the kind of writing that Orwell railed against in his essay. All this sort of writing does is obscure the point you want to make behind false intellectualism. As Orwell said, “Never use a long word when a short one will do.”

Clichés. Clichés are as common as mud but at least getting rid of them is low-hanging fruit. If you’re not sure whether something is a cliché, it’s better to just avoid it. Awful, right? Clichés are stale phrases that have lost their impact and novelty through overuse. At some point, “The grass is always greener on the other side” was a witty observation, but it’s a cliché now. Again, Orwell said it well: “Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.” Oh, and memes very quickly become clichés — be warned.

The passive voice. In most cases, the subject of the sentence should be the person or thing taking action, not the thing being acted on. For example, “This article was written by Harry” is written in the passive voice because the subject (“this article”) is the thing being acted on. The equivalent active construction would be: “Harry wrote this article.” Prose written in the passive voice tends to have an aloofness and passivity to it, which is why it’s generally better to write an active sentence.

Rambling . When you’re not quite sure what you want to say, it’s easy to ramble around a point, phrasing it in three or four different ways and then, instead of cutting them down to a single concise sentence, slapping all four together into a clunky, unclear paragraph. A single direct sentence is almost always better than four that tease around a point.

Give your work some space

When you write something, you get very close to it. It’s almost impossible to have the distance to edit properly straight away. Instead, you need to step away and come back later with fresh eyes. The longer you can leave a draft before editing it, the better. I have some essays I go back to every few months for another pass — they’re still not done yet. For most things, though, somewhere from half an hour to two days is enough of a break that you can then edit well. Even 10 minutes will do in a pinch for things like emails.

And when you sit down to edit, read your work out loud.

By forcing yourself to speak the words, rather than just scanning them on a computer screen, you’ll catch more problems and get a better feel for how everything flows. If you stumble over something, your reader will probably stumble over it, too. Some writers even print out their drafts and make edits with a red pen while they read them aloud.

Cut, cut, cut

Overwriting is a bigger problem than underwriting. It’s much more likely you’ve written too much than too little. It’s a lot easier to throw words at a problem than to take the time to find the right ones. As Blaise Pascal, a 17th-century writer and scientist (no, not Mark Twain) wrote in a letter, “I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.”

The rule for most writers is, “If in doubt, cut it.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning writer John McPhee has called the process “writing by omission.” Novelist Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (and not William Faulkner, although he may have popularized this version of it) exhorted a version of the oft-repeated phrase, “In writing you must kill all your darlings.” This is true at every level: If a word isn’t necessary in a sentence, cut it; if a sentence isn’t necessary in a paragraph, cut it; and if a paragraph isn’t necessary, cut it, too.

Go through what you’ve written and look for the bits you can cut without affecting the whole — and cut them. It will tighten the work and make everything you’re trying to say clearer.

Spend the most time on the beginning

The beginning of anything you write is the most important part. If you can’t catch someone’s attention at the start, you won’t have a chance to hold it later. Whether you’re writing a novel or an email, you should spend a disproportionate amount of time working on the first few sentences, paragraphs or pages. A lot of problems that can be glossed over in the middle are your undoing at the start.

Pay attention to structure

The structure is what your writing hangs on. It doesn’t matter how perfectly the individual sentences are phrased if the whole thing is a nonsensical mess. For emails and other short things, the old college favorite of a topic sentence followed by supporting paragraphs and a conclusion is hard to get wrong. Just make sure you consider your intended audience. A series of long, unrelenting paragraphs will discourage people from reading. Break things up into concise points and, where necessary, insert subheads — as there are in this article. If I’d written this without them, you would just be looking at a stark wall of text.

For longer pieces, structure is something you’ll need to put a lot of work into. Stream of consciousness writing rarely reads well and you generally don’t have the option to break up everything into short segments with subheads. Narratives need to flow and arguments need to build. You have to think about what you’re trying to say in each chapter, section or paragraph, and consider whether it’s working — or if that part would be better placed elsewhere. It’s normal (and even desirable) that the structure of your work will change drastically between drafts; it’s a sign that you’re developing the piece as a whole, rather than just fixing the small problems.

A lot of the time when something you’ve written “just doesn’t work” for people, the structure is to blame. They might not be able to put the problems into words, but they can feel something’s off.

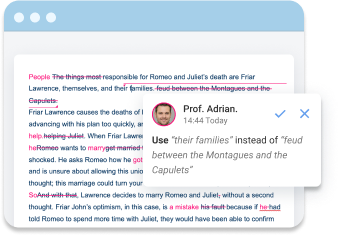

Use all the resources you can

While you might not be lucky enough to have access to an editor (Hey, Alan!), there are services that can help.

Grammarly is a writing assistant that flags common writing, spelling and grammatical errors; it’s great for catching simple mistakes and cleaning up drafts of your work. A good thesaurus (or even Thesaurus.com ) is also essential for finding just the right word. And don’t neglect a second pair of eyes: Ask relatives and friends to read over your work. They might catch some things you missed and can tell you when something is amiss.

Editing your work is at least as important as writing it in the first place. The tweaking, revisiting and revising is what takes something that could be good — and makes it good. Don’t neglect it.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that the phrase “kill your darlings,” originated with novelist Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch , who actually said “murder your darlings,” and not William Faulkner, to whom the phrase is often attributed.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2024 10:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Film Analysis

What this handout is about.

This handout introduces film analysis and and offers strategies and resources for approaching film analysis assignments.

Writing the film analysis essay

Writing a film analysis requires you to consider the composition of the film—the individual parts and choices made that come together to create the finished piece. Film analysis goes beyond the analysis of the film as literature to include camera angles, lighting, set design, sound elements, costume choices, editing, etc. in making an argument. The first step to analyzing the film is to watch it with a plan.

Watching the film

First it’s important to watch the film carefully with a critical eye. Consider why you’ve been assigned to watch a film and write an analysis. How does this activity fit into the course? Why have you been assigned this particular film? What are you looking for in connection to the course content? Let’s practice with this clip from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Here are some tips on how to watch the clip critically, just as you would an entire film:

- Give the clip your undivided attention at least once. Pay close attention to details and make observations that might start leading to bigger questions.

- Watch the clip a second time. For this viewing, you will want to focus specifically on those elements of film analysis that your class has focused on, so review your course notes. For example, from whose perspective is this clip shot? What choices help convey that perspective? What is the overall tone, theme, or effect of this clip?

- Take notes while you watch for the second time. Notes will help you keep track of what you noticed and when, if you include timestamps in your notes. Timestamps are vital for citing scenes from a film!

For more information on watching a film, check out the Learning Center’s handout on watching film analytically . For more resources on researching film, including glossaries of film terms, see UNC Library’s research guide on film & cinema .

Brainstorming ideas

Once you’ve watched the film twice, it’s time to brainstorm some ideas based on your notes. Brainstorming is a major step that helps develop and explore ideas. As you brainstorm, you may want to cluster your ideas around central topics or themes that emerge as you review your notes. Did you ask several questions about color? Were you curious about repeated images? Perhaps these are directions you can pursue.

If you’re writing an argumentative essay, you can use the connections that you develop while brainstorming to draft a thesis statement . Consider the assignment and prompt when formulating a thesis, as well as what kind of evidence you will present to support your claims. Your evidence could be dialogue, sound edits, cinematography decisions, etc. Much of how you make these decisions will depend on the type of film analysis you are conducting, an important decision covered in the next section.

After brainstorming, you can draft an outline of your film analysis using the same strategies that you would for other writing assignments. Here are a few more tips to keep in mind as you prepare for this stage of the assignment:

- Make sure you understand the prompt and what you are being asked to do. Remember that this is ultimately an assignment, so your thesis should answer what the prompt asks. Check with your professor if you are unsure.

- In most cases, the director’s name is used to talk about the film as a whole, for instance, “Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo .” However, some writers may want to include the names of other persons who helped to create the film, including the actors, the cinematographer, and the sound editor, among others.

- When describing a sequence in a film, use the literary present. An example could be, “In Vertigo , Hitchcock employs techniques of observation to dramatize the act of detection.”

- Finding a screenplay/script of the movie may be helpful and save you time when compiling citations. But keep in mind that there may be differences between the screenplay and the actual product (and these differences might be a topic of discussion!).

- Go beyond describing basic film elements by articulating the significance of these elements in support of your particular position. For example, you may have an interpretation of the striking color green in Vertigo , but you would only mention this if it was relevant to your argument. For more help on using evidence effectively, see the section on “using evidence” in our evidence handout .

Also be sure to avoid confusing the terms shot, scene, and sequence. Remember, a shot ends every time the camera cuts; a scene can be composed of several related shots; and a sequence is a set of related scenes.

Different types of film analysis

As you consider your notes, outline, and general thesis about a film, the majority of your assignment will depend on what type of film analysis you are conducting. This section explores some of the different types of film analyses you may have been assigned to write.

Semiotic analysis

Semiotic analysis is the interpretation of signs and symbols, typically involving metaphors and analogies to both inanimate objects and characters within a film. Because symbols have several meanings, writers often need to determine what a particular symbol means in the film and in a broader cultural or historical context.

For instance, a writer could explore the symbolism of the flowers in Vertigo by connecting the images of them falling apart to the vulnerability of the heroine.

Here are a few other questions to consider for this type of analysis:

- What objects or images are repeated throughout the film?

- How does the director associate a character with small signs, such as certain colors, clothing, food, or language use?

- How does a symbol or object relate to other symbols and objects, that is, what is the relationship between the film’s signs?

Many films are rich with symbolism, and it can be easy to get lost in the details. Remember to bring a semiotic analysis back around to answering the question “So what?” in your thesis.

Narrative analysis

Narrative analysis is an examination of the story elements, including narrative structure, character, and plot. This type of analysis considers the entirety of the film and the story it seeks to tell.

For example, you could take the same object from the previous example—the flowers—which meant one thing in a semiotic analysis, and ask instead about their narrative role. That is, you might analyze how Hitchcock introduces the flowers at the beginning of the film in order to return to them later to draw out the completion of the heroine’s character arc.

To create this type of analysis, you could consider questions like:

- How does the film correspond to the Three-Act Structure: Act One: Setup; Act Two: Confrontation; and Act Three: Resolution?

- What is the plot of the film? How does this plot differ from the narrative, that is, how the story is told? For example, are events presented out of order and to what effect?

- Does the plot revolve around one character? Does the plot revolve around multiple characters? How do these characters develop across the film?

When writing a narrative analysis, take care not to spend too time on summarizing at the expense of your argument. See our handout on summarizing for more tips on making summary serve analysis.

Cultural/historical analysis

One of the most common types of analysis is the examination of a film’s relationship to its broader cultural, historical, or theoretical contexts. Whether films intentionally comment on their context or not, they are always a product of the culture or period in which they were created. By placing the film in a particular context, this type of analysis asks how the film models, challenges, or subverts different types of relations, whether historical, social, or even theoretical.

For example, the clip from Vertigo depicts a man observing a woman without her knowing it. You could examine how this aspect of the film addresses a midcentury social concern about observation, such as the sexual policing of women, or a political one, such as Cold War-era McCarthyism.

A few of the many questions you could ask in this vein include:

- How does the film comment on, reinforce, or even critique social and political issues at the time it was released, including questions of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality?

- How might a biographical understanding of the film’s creators and their historical moment affect the way you view the film?

- How might a specific film theory, such as Queer Theory, Structuralist Theory, or Marxist Film Theory, provide a language or set of terms for articulating the attributes of the film?

Take advantage of class resources to explore possible approaches to cultural/historical film analyses, and find out whether you will be expected to do additional research into the film’s context.

Mise-en-scène analysis

A mise-en-scène analysis attends to how the filmmakers have arranged compositional elements in a film and specifically within a scene or even a single shot. This type of analysis organizes the individual elements of a scene to explore how they come together to produce meaning. You may focus on anything that adds meaning to the formal effect produced by a given scene, including: blocking, lighting, design, color, costume, as well as how these attributes work in conjunction with decisions related to sound, cinematography, and editing. For example, in the clip from Vertigo , a mise-en-scène analysis might ask how numerous elements, from lighting to camera angles, work together to present the viewer with the perspective of Jimmy Stewart’s character.

To conduct this type of analysis, you could ask:

- What effects are created in a scene, and what is their purpose?

- How does this scene represent the theme of the movie?

- How does a scene work to express a broader point to the film’s plot?

This detailed approach to analyzing the formal elements of film can help you come up with concrete evidence for more general film analysis assignments.

Reviewing your draft

Once you have a draft, it’s helpful to get feedback on what you’ve written to see if your analysis holds together and you’ve conveyed your point. You may not necessarily need to find someone who has seen the film! Ask a writing coach, roommate, or family member to read over your draft and share key takeaways from what you have written so far.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Aumont, Jacques, and Michel Marie. 1988. L’analyse Des Films . Paris: Nathan.

Media & Design Center. n.d. “Film and Cinema Research.” UNC University Libraries. Last updated February 10, 2021. https://guides.lib.unc.edu/filmresearch .

Oxford Royale Academy. n.d. “7 Ways to Watch Film.” Oxford Royale Academy. Accessed April 2021. https://www.oxford-royale.com/articles/7-ways-watch-films-critically/ .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Essay Title: Rules, Tips, Mistakes to Avoid

Table of contents

- 1 What Makes a Good Title?

- 2.1 Use your essay to develop your topic

- 2.2 Identify keywords and take advantage of them

- 2.3 Use Multiple Titles

- 3.1 MLA Format

- 3.2 APA Format

- 3.3 Chicago Format

- 4 What to Avoid When Writing a Title for an Essay?

- 5 Take into account Your Paper Style

- 6 Types Of Papers and the Best Titles For Them

- 7.1 Questions make Catchy

- 7.2 Describe the Paper in 5 Words

- 7.3 Use One Direct Word

- 7.4 Extract a Sentence from the Paper

- 7.5 Take advantage of Pop-Culture

- 7.6 Put “On” at the beginning

- 7.7 Start with a Verb in “-ing”

- 7.8 Give a Mental Visualization of Your Topic

- 7.9 Modify a Title that was Rejected