Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved June 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

Literary Analysis Essay

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

Last updated on: May 21, 2023

Literary Analysis Essay - Ultimate Guide By Professionals

By: Cordon J.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Dec 3, 2019

A literary analysis essay specifically examines and evaluates a piece of literature or a literary work. It also understands and explains the links between the small parts to their whole information.

It is important for students to understand the meaning and the true essence of literature to write a literary essay.

One of the most difficult assignments for students is writing a literary analysis essay. It can be hard to come up with an original idea or find enough material to write about. You might think you need years of experience in order to create a good paper, but that's not true.

This blog post will show you how easy it can be when you follow the steps given here.Writing such an essay involves the breakdown of a book into small parts and understanding each part separately. It seems easy, right?

Trust us, it is not as hard as good book reports but it may also not be extremely easy. You will have to take into account different approaches and explain them in relation with the chosen literary work.

It is a common high school and college assignment and you can learn everything in this blog.

Continue reading for some useful tips with an example to write a literary analysis essay that will be on point. You can also explore our detailed article on writing an analytical essay .

On this Page

What is a Literary Analysis Essay?

A literary analysis essay is an important kind of essay that focuses on the detailed analysis of the work of literature.

The purpose of a literary analysis essay is to explain why the author has used a specific theme for his work. Or examine the characters, themes, literary devices , figurative language, and settings in the story.

This type of essay encourages students to think about how the book or the short story has been written. And why the author has created this work.

The method used in the literary analysis essay differs from other types of essays. It primarily focuses on the type of work and literature that is being analyzed.

Mostly, you will be going to break down the work into various parts. In order to develop a better understanding of the idea being discussed, each part will be discussed separately.

The essay should explain the choices of the author and point of view along with your answers and personal analysis.

How To Write A Literary Analysis Essay

So how to start a literary analysis essay? The answer to this question is quite simple.

The following sections are required to write an effective literary analysis essay. By following the guidelines given in the following sections, you will be able to craft a winning literary analysis essay.

Introduction

The aim of the introduction is to establish a context for readers. You have to give a brief on the background of the selected topic.

It should contain the name of the author of the literary work along with its title. The introduction should be effective enough to grab the reader’s attention.

In the body section, you have to retell the story that the writer has narrated. It is a good idea to create a summary as it is one of the important tips of literary analysis.

Other than that, you are required to develop ideas and disclose the observed information related to the issue. The ideal length of the body section is around 1000 words.

To write the body section, your observation should be based on evidence and your own style of writing.

It would be great if the body of your essay is divided into three paragraphs. Make a strong argument with facts related to the thesis statement in all of the paragraphs in the body section.

Start writing each paragraph with a topic sentence and use transition words when moving to the next paragraph.

Summarize the important points of your literary analysis essay in this section. It is important to compose a short and strong conclusion to help you make a final impression of your essay.

Pay attention that this section does not contain any new information. It should provide a sense of completion by restating the main idea with a short description of your arguments. End the conclusion with your supporting details.

You have to explain why the book is important. Also, elaborate on the means that the authors used to convey her/his opinion regarding the issue.

For further understanding, here is a downloadable literary analysis essay outline. This outline will help you structure and format your essay properly and earn an A easily.

DOWNLOADABLE LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE (PDF)

Types of Literary Analysis Essay

- Close reading - This method involves attentive reading and detailed analysis. No need for a lot of knowledge and inspiration to write an essay that shows your creative skills.

- Theoretical - In this type, you will rely on theories related to the selected topic.

- Historical - This type of essay concerns the discipline of history. Sometimes historical analysis is required to explain events in detail.

- Applied - This type involves analysis of a specific issue from a practical perspective.

- Comparative - This type of writing is based on when two or more alternatives are compared

Examples of Literary Analysis Essay

Examples are great to understand any concept, especially if it is related to writing. Below are some great literary analysis essay examples that showcase how this type of essay is written.

A ROSE FOR EMILY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE GREAT GATSBY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

If you do not have experience in writing essays, this will be a very chaotic process for you. In that case, it is very important for you to conduct good research on the topic before writing.

There are two important points that you should keep in mind when writing a literary analysis essay.

First, remember that it is very important to select a topic in which you are interested. Choose something that really inspires you. This will help you to catch the attention of a reader.

The selected topic should reflect the main idea of writing. In addition to that, it should also express your point of view as well.

Another important thing is to draft a good outline for your literary analysis essay. It will help you to define a central point and division of this into parts for further discussion.

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Literary analysis essays are mostly based on artistic works like books, movies, paintings, and other forms of art. However, generally, students choose novels and books to write their literary essays.

Some cool, fresh, and good topics and ideas are listed below:

- Role of the Three Witches in flaming Macbeth’s ambition.

- Analyze the themes of the Play Antigone,

- Discuss Ajax as a tragic hero.

- The Judgement of Paris: Analyze the Reasons and their Consequences.

- Oedipus Rex: A Doomed Son or a Conqueror?

- Describe the Oedipus complex and Electra complex in relation to their respective myths.

- Betrayal is a common theme of Shakespearean tragedies. Discuss

- Identify and analyze the traits of history in T.S Eliot’s ‘Gerontion’.

- Analyze the theme of identity crisis in The Great Gatsby.

- Analyze the writing style of Emily Dickinson.

If you are still in doubt then there is nothing bad in getting professional writers’ help.

We at 5StarEssays.com can help you get a custom paper as per your specified requirements with our do essay for me service.

Our essay writers will help you write outstanding literary essays or any other type of essay. Such as compare and contrast essays, descriptive essays, rhetorical essays. We cover all of these.

So don’t waste your time browsing the internet and place your order now to get your well-written custom paper.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should a literary analysis essay include.

A good literary analysis essay must include a proper and in-depth explanation of your ideas. They must be backed with examples and evidence from the text. Textual evidence includes summaries, paraphrased text, original work details, and direct quotes.

What are the 4 components of literary analysis?

Here are the 4 essential parts of a literary analysis essay;

No literary work is explained properly without discussing and explaining these 4 things.

How do you start a literary analysis essay?

Start your literary analysis essay with the name of the work and the title. Hook your readers by introducing the main ideas that you will discuss in your essay and engage them from the start.

How do you do a literary analysis?

In a literary analysis essay, you study the text closely, understand and interpret its meanings. And try to find out the reasons behind why the author has used certain symbols, themes, and objects in the work.

Why is literary analysis important?

It encourages the students to think beyond their existing knowledge, experiences, and belief and build empathy. This helps in improving the writing skills also.

What is the fundamental characteristic of a literary analysis essay?

Interpretation is the fundamental and important feature of a literary analysis essay. The essay is based on how well the writer explains and interprets the work.

Law, Finance Essay

Cordon. is a published author and writing specialist. He has worked in the publishing industry for many years, providing writing services and digital content. His own writing career began with a focus on literature and linguistics, which he continues to pursue. Cordon is an engaging and professional individual, always looking to help others achieve their goals.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics for Students

- Write a Perfect Literary Analysis Essay Outline

People Also Read

- essay writing old

- qualitative research method

- how to write a compare and contrast essay

- illustration essay writing

- writing a book review

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the 31 literary devices you must know.

General Education

Need to analyze The Scarlet Letter or To Kill a Mockingbird for English class, but fumbling for the right vocabulary and concepts for literary devices? You've come to the right place. To successfully interpret and analyze literary texts, you'll first need to have a solid foundation in literary terms and their definitions.

In this article, we'll help you get familiar with most commonly used literary devices in prose and poetry. We'll give you a clear definition of each of the terms we discuss along with examples of literary elements and the context in which they most often appear (comedic writing, drama, or other).

Before we get to the list of literary devices, however, we have a quick refresher on what literary devices are and how understanding them will help you analyze works of literature.

What Are Literary Devices and Why Should You Know Them?

Literary devices are techniques that writers use to create a special and pointed effect in their writing, to convey information, or to help readers understand their writing on a deeper level.

Often, literary devices are used in writing for emphasis or clarity. Authors will also use literary devices to get readers to connect more strongly with either a story as a whole or specific characters or themes.

So why is it important to know different literary devices and terms? Aside from helping you get good grades on your literary analysis homework, there are several benefits to knowing the techniques authors commonly use.

Being able to identify when different literary techniques are being used helps you understand the motivation behind the author's choices. For example, being able to identify symbols in a story can help you figure out why the author might have chosen to insert these focal points and what these might suggest in regard to her attitude toward certain characters, plot points, and events.

In addition, being able to identify literary devices can make a written work's overall meaning or purpose clearer to you. For instance, let's say you're planning to read (or re-read) The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. By knowing that this particular book is a religious allegory with references to Christ (represented by the character Aslan) and Judas (represented by Edmund), it will be clearer to you why Lewis uses certain language to describe certain characters and why certain events happen the way they do.

Finally, literary techniques are important to know because they make texts more interesting and more fun to read. If you were to read a novel without knowing any literary devices, chances are you wouldn't be able to detect many of the layers of meaning interwoven into the story via different techniques.

Now that we've gone over why you should spend some time learning literary devices, let's take a look at some of the most important literary elements to know.

List of Literary Devices: 31 Literary Terms You Should Know

Below is a list of literary devices, most of which you'll often come across in both prose and poetry. We explain what each literary term is and give you an example of how it's used. This literary elements list is arranged in alphabetical order.

An allegory is a story that is used to represent a more general message about real-life (historical) issues and/or events. It is typically an entire book, novel, play, etc.

Example: George Orwell's dystopian book Animal Farm is an allegory for the events preceding the Russian Revolution and the Stalinist era in early 20th century Russia. In the story, animals on a farm practice animalism, which is essentially communism. Many characters correspond to actual historical figures: Old Major represents both the founder of communism Karl Marx and the Russian communist leader Vladimir Lenin; the farmer, Mr. Jones, is the Russian Czar; the boar Napoleon stands for Joseph Stalin; and the pig Snowball represents Leon Trotsky.

Alliteration

Alliteration is a series of words or phrases that all (or almost all) start with the same sound. These sounds are typically consonants to give more stress to that syllable. You'll often come across alliteration in poetry, titles of books and poems ( Jane Austen is a fan of this device, for example—just look at Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility ), and tongue twisters.

Example: "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers." In this tongue twister, the "p" sound is repeated at the beginning of all major words.

Allusion is when an author makes an indirect reference to a figure, place, event, or idea originating from outside the text. Many allusions make reference to previous works of literature or art.

Example: "Stop acting so smart—it's not like you're Einstein or something." This is an allusion to the famous real-life theoretical physicist Albert Einstein.

Anachronism

An anachronism occurs when there is an (intentional) error in the chronology or timeline of a text. This could be a character who appears in a different time period than when he actually lived, or a technology that appears before it was invented. Anachronisms are often used for comedic effect.

Example: A Renaissance king who says, "That's dope, dude!" would be an anachronism, since this type of language is very modern and not actually from the Renaissance period.

Anaphora is when a word or phrase is repeated at the beginning of multiple sentences throughout a piece of writing. It's used to emphasize the repeated phrase and evoke strong feelings in the audience.

Example: A famous example of anaphora is Winston Churchill's "We Shall Fight on the Beaches" speech. Throughout this speech, he repeats the phrase "we shall fight" while listing numerous places where the British army will continue battling during WWII. He did this to rally both troops and the British people and to give them confidence that they would still win the war.

Anthropomorphism

An anthropomorphism occurs when something nonhuman, such as an animal, place, or inanimate object, behaves in a human-like way.

Example: Children's cartoons have many examples of anthropomorphism. For example, Mickey and Minnie Mouse can speak, wear clothes, sing, dance, drive cars, etc. Real mice can't do any of these things, but the two mouse characters behave much more like humans than mice.

Asyndeton is when the writer leaves out conjunctions (such as "and," "or," "but," and "for") in a group of words or phrases so that the meaning of the phrase or sentence is emphasized. It is often used for speeches since sentences containing asyndeton can have a powerful, memorable rhythm.

Example: Abraham Lincoln ends the Gettysburg Address with the phrase "...and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth." By leaving out certain conjunctions, he ends the speech on a more powerful, melodic note.

Colloquialism

Colloquialism is the use of informal language and slang. It's often used by authors to lend a sense of realism to their characters and dialogue. Forms of colloquialism include words, phrases, and contractions that aren't real words (such as "gonna" and "ain't").

Example: "Hey, what's up, man?" This piece of dialogue is an example of a colloquialism, since it uses common everyday words and phrases, namely "what's up" and "man."

An epigraph is when an author inserts a famous quotation, poem, song, or other short passage or text at the beginning of a larger text (e.g., a book, chapter, etc.). An epigraph is typically written by a different writer (with credit given) and used as a way to introduce overarching themes or messages in the work. Some pieces of literature, such as Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick , incorporate multiple epigraphs throughout.

Example: At the beginning of Ernest Hemingway's book The Sun Also Rises is an epigraph that consists of a quotation from poet Gertrude Stein, which reads, "You are all a lost generation," and a passage from the Bible.

Epistrophe is similar to anaphora, but in this case, the repeated word or phrase appears at the end of successive statements. Like anaphora, it is used to evoke an emotional response from the audience.

Example: In Lyndon B. Johnson's speech, "The American Promise," he repeats the word "problem" in a use of epistrophe: "There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem."

A euphemism is when a more mild or indirect word or expression is used in place of another word or phrase that is considered harsh, blunt, vulgar, or unpleasant.

Example: "I'm so sorry, but he didn't make it." The phrase "didn't make it" is a more polite and less blunt way of saying that someone has died.

A flashback is an interruption in a narrative that depicts events that have already occurred, either before the present time or before the time at which the narration takes place. This device is often used to give the reader more background information and details about specific characters, events, plot points, and so on.

Example: Most of the novel Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë is a flashback from the point of view of the housekeeper, Nelly Dean, as she engages in a conversation with a visitor named Lockwood. In this story, Nelly narrates Catherine Earnshaw's and Heathcliff's childhoods, the pair's budding romance, and their tragic demise.

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is when an author indirectly hints at—through things such as dialogue, description, or characters' actions—what's to come later on in the story. This device is often used to introduce tension to a narrative.

Example: Say you're reading a fictionalized account of Amelia Earhart. Before she embarks on her (what we know to be unfortunate) plane ride, a friend says to her, "Be safe. Wouldn't want you getting lost—or worse." This line would be an example of foreshadowing because it implies that something bad ("or worse") will happen to Earhart.

Hyperbole is an exaggerated statement that's not meant to be taken literally by the reader. It is often used for comedic effect and/or emphasis.

Example: "I'm so hungry I could eat a horse." The speaker will not literally eat an entire horse (and most likely couldn't ), but this hyperbole emphasizes how starved the speaker feels.

Imagery is when an author describes a scene, thing, or idea so that it appeals to our senses (taste, smell, sight, touch, or hearing). This device is often used to help the reader clearly visualize parts of the story by creating a strong mental picture.

Example: Here's an example of imagery taken from William Wordsworth's famous poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud":

When all at once I saw a crowd, A host of golden Daffodils; Beside the Lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Irony is when a statement is used to express an opposite meaning than the one literally expressed by it. There are three types of irony in literature:

- Verbal irony: When someone says something but means the opposite (similar to sarcasm).

- Situational irony: When something happens that's the opposite of what was expected or intended to happen.

- Dramatic irony: When the audience is aware of the true intentions or outcomes, while the characters are not . As a result, certain actions and/or events take on different meanings for the audience than they do for the characters involved.

- Verbal irony: One example of this type of irony can be found in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado." In this short story, a man named Montresor plans to get revenge on another man named Fortunato. As they toast, Montresor says, "And I, Fortunato—I drink to your long life." This statement is ironic because we the readers already know by this point that Montresor plans to kill Fortunato.

- Situational irony: A girl wakes up late for school and quickly rushes to get there. As soon as she arrives, though, she realizes that it's Saturday and there is no school.

- Dramatic irony: In William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet , Romeo commits suicide in order to be with Juliet; however, the audience (unlike poor Romeo) knows that Juliet is not actually dead—just asleep.

Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is the comparing and contrasting of two or more different (usually opposite) ideas, characters, objects, etc. This literary device is often used to help create a clearer picture of the characteristics of one object or idea by comparing it with those of another.

Example: One of the most famous literary examples of juxtaposition is the opening passage from Charles Dickens' novel A Tale of Two Cities :

"It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair …"

Malapropism

Malapropism happens when an incorrect word is used in place of a word that has a similar sound. This misuse of the word typically results in a statement that is both nonsensical and humorous; as a result, this device is commonly used in comedic writing.

Example: "I just can't wait to dance the flamingo!" Here, a character has accidentally called the flamenco (a type of dance) the flamingo (an animal).

Metaphor/Simile

Metaphors are when ideas, actions, or objects are described in non-literal terms. In short, it's when an author compares one thing to another. The two things being described usually share something in common but are unalike in all other respects.

A simile is a type of metaphor in which an object, idea, character, action, etc., is compared to another thing using the words "as" or "like."

Both metaphors and similes are often used in writing for clarity or emphasis.

"What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun." In this line from Romeo and Juliet , Romeo compares Juliet to the sun. However, because Romeo doesn't use the words "as" or "like," it is not a simile—just a metaphor.

"She is as vicious as a lion." Since this statement uses the word "as" to make a comparison between "she" and "a lion," it is a simile.

A metonym is when a related word or phrase is substituted for the actual thing to which it's referring. This device is usually used for poetic or rhetorical effect .

Example: "The pen is mightier than the sword." This statement, which was coined by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1839, contains two examples of metonymy: "the pen" refers to "the written word," and "the sword" refers to "military force/violence."

Mood is the general feeling the writer wants the audience to have. The writer can achieve this through description, setting, dialogue, and word choice .

Example: Here's a passage from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit: "It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots and lots of pegs for hats and coats -- the hobbit was fond of visitors." In this passage, Tolkien uses detailed description to set create a cozy, comforting mood. From the writing, you can see that the hobbit's home is well-cared for and designed to provide comfort.

Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia is a word (or group of words) that represents a sound and actually resembles or imitates the sound it stands for. It is often used for dramatic, realistic, or poetic effect.

Examples: Buzz, boom, chirp, creak, sizzle, zoom, etc.

An oxymoron is a combination of two words that, together, express a contradictory meaning. This device is often used for emphasis, for humor, to create tension, or to illustrate a paradox (see next entry for more information on paradoxes).

Examples: Deafening silence, organized chaos, cruelly kind, insanely logical, etc.

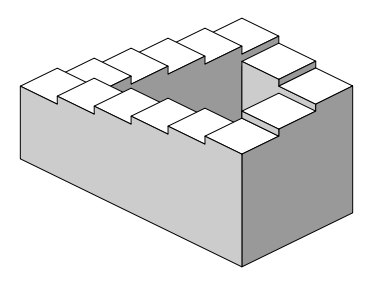

A paradox is a statement that appears illogical or self-contradictory but, upon investigation, might actually be true or plausible.

Note that a paradox is different from an oxymoron: a paradox is an entire phrase or sentence, whereas an oxymoron is a combination of just two words.

Example: Here's a famous paradoxical sentence: "This statement is false." If the statement is true, then it isn't actually false (as it suggests). But if it's false, then the statement is true! Thus, this statement is a paradox because it is both true and false at the same time.

Personification

Personification is when a nonhuman figure or other abstract concept or element is described as having human-like qualities or characteristics. (Unlike anthropomorphism where non-human figures become human-like characters, with personification, the object/figure is simply described as being human-like.) Personification is used to help the reader create a clearer mental picture of the scene or object being described.

Example: "The wind moaned, beckoning me to come outside." In this example, the wind—a nonhuman element—is being described as if it is human (it "moans" and "beckons").

Repetition is when a word or phrase is written multiple times, usually for the purpose of emphasis. It is often used in poetry (for purposes of rhythm as well).

Example: When Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote the score for the hit musical Hamilton, gave his speech at the 2016 Tony's, he recited a poem he'd written that included the following line:

And love is love is love is love is love is love is love is love cannot be killed or swept aside.

Satire is genre of writing that criticizes something , such as a person, behavior, belief, government, or society. Satire often employs irony, humor, and hyperbole to make its point.

Example: The Onion is a satirical newspaper and digital media company. It uses satire to parody common news features such as opinion columns, editorial cartoons, and click bait headlines.

A type of monologue that's often used in dramas, a soliloquy is when a character speaks aloud to himself (and to the audience), thereby revealing his inner thoughts and feelings.

Example: In Romeo and Juliet , Juliet's speech on the balcony that begins with, "O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefore art thou Romeo?" is a soliloquy, as she is speaking aloud to herself (remember that she doesn't realize Romeo's there listening!).

Symbolism refers to the use of an object, figure, event, situation, or other idea in a written work to represent something else— typically a broader message or deeper meaning that differs from its literal meaning.

The things used for symbolism are called "symbols," and they'll often appear multiple times throughout a text, sometimes changing in meaning as the plot progresses.

Example: In F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby , the green light that sits across from Gatsby's mansion symbolizes Gatsby's hopes and dreams .

A synecdoche is a literary device in which part of something is used to represent the whole, or vice versa. It's similar to a metonym (see above); however, a metonym doesn't have to represent the whole—just something associated with the word used.

Example: "Help me out, I need some hands!" In this case, "hands" is being used to refer to people (the whole human, essentially).

While mood is what the audience is supposed to feel, tone is the writer or narrator's attitude towards a subject . A good writer will always want the audience to feel the mood they're trying to evoke, but the audience may not always agree with the narrator's tone, especially if the narrator is an unsympathetic character or has viewpoints that differ from those of the reader.

Example: In an essay disdaining Americans and some of the sites they visit as tourists, Rudyard Kipling begins with the line, "Today I am in the Yellowstone Park, and I wish I were dead." If you enjoy Yellowstone and/or national parks, you may not agree with the author's tone in this piece.

How to Identify and Analyze Literary Devices: 4 Tips

In order to fully interpret pieces of literature, you have to understand a lot about literary devices in the texts you read. Here are our top tips for identifying and analyzing different literary techniques:

Tip 1: Read Closely and Carefully

First off, you'll need to make sure that you're reading very carefully. Resist the temptation to skim or skip any sections of the text. If you do this, you might miss some literary devices being used and, as a result, will be unable to accurately interpret the text.

If there are any passages in the work that make you feel especially emotional, curious, intrigued, or just plain interested, check that area again for any literary devices at play.

It's also a good idea to reread any parts you thought were confusing or that you didn't totally understand on a first read-through. Doing this ensures that you have a solid grasp of the passage (and text as a whole) and will be able to analyze it appropriately.

Tip 2: Memorize Common Literary Terms

You won't be able to identify literary elements in texts if you don't know what they are or how they're used, so spend some time memorizing the literary elements list above. Knowing these (and how they look in writing) will allow you to more easily pinpoint these techniques in various types of written works.

Tip 3: Know the Author's Intended Audience

Knowing what kind of audience an author intended her work to have can help you figure out what types of literary devices might be at play.

For example, if you were trying to analyze a children's book, you'd want to be on the lookout for child-appropriate devices, such as repetition and alliteration.

Tip 4: Take Notes and Bookmark Key Passages and Pages

This is one of the most important tips to know, especially if you're reading and analyzing works for English class. As you read, take notes on the work in a notebook or on a computer. Write down any passages, paragraphs, conversations, descriptions, etc., that jump out at you or that contain a literary device you were able to identify.

You can also take notes directly in the book, if possible (but don't do this if you're borrowing a book from the library!). I recommend circling keywords and important phrases, as well as starring interesting or particularly effective passages and paragraphs.

Lastly, use sticky notes or post-its to bookmark pages that are interesting to you or that have some kind of notable literary device. This will help you go back to them later should you need to revisit some of what you've found for a paper you plan to write.

What's Next?

Looking for more in-depth explorations and examples of literary devices? Join us as we delve into imagery , personification , rhetorical devices , tone words and mood , and different points of view in literature, as well as some more poetry-specific terms like assonance and iambic pentameter .

Reading The Great Gatsby for class or even just for fun? Then you'll definitely want to check out our expert guides on the biggest themes in this classic book, from love and relationships to money and materialism .

Got questions about Arthur Miller's The Crucible ? Read our in-depth articles to learn about the most important themes in this play and get a complete rundown of all the characters .

For more information on your favorite works of literature, take a look at our collection of high-quality book guides and our guide to the 9 literary elements that appear in every story !

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

Literary Elements: What are the 7 Elements of Literature?

by Fija Callaghan

Literary elements in storytelling can cause a lot of confusion, and even a bit of fear, among new writers. Once you’re able to recognize the literary elements of a story you’ll realize that they’re present in absolutely everything.

All stories are made up of basic structural building blocks such as plot, character, and theme, whether it’s a riveting Friday night TV series, a two-hundred-thousand-word Dickensian novel of redemption, or a trashy paperback about fifty shades of highly inappropriate workplace relations. Once you understand how these elements of story take shape from our literary elements list, you’ll be able to use them to explore entire worlds of your own.

What are literary elements?

Literary elements are the common structural elements that every story needs to be successful. The seven elements of literature are character, setting, perspective, plot, conflict, theme, and voice. These elements are the building blocks of good stories because if any are missing, the story will feel incomplete and unsatisfying. Applying these elements is critical to crafting an effective story.

Here’s an example of why literary elements matter in storytelling:

The cat sat on the chair is an event. A small, quiet happenstance with a beginning and an ending so closely entwined that you almost can’t tell one from the other.

The cat sat on the dog’s chair is a story.

Why? Because with the addition of one little word, suddenly this quiet happenstance is glowing with possibility. We have our characters—a cat and a dog, whose relationship is gently hinted at with the promise of being further explored. We have our setting—a chair, which has taken on new importance as the central axis of this moment. And, perhaps most importantly, we have our conflict. An inciting moment where two characters want something and we know that these desires can’t exist side by side. This is a story.

All stories come from these basic building blocks that we call “literary elements.” Without them, seeds of a story like this one can’t grow into rich, full narratives.

You may already be able to identify some or all of these literary elements from the stories you’ve experienced throughout your life, whether that’s through reading them or from watching them in films or on television. Once you know what these literary elements of a story are and how they fit together, you’ll be able to create vivid, engaging stories from your own little seeds.

What’s the difference between literary elements vs. literary devices?

Sometimes you’ll see a “literary elements list” or “literary devices list” that toss the two together in one big storytelling melange, but literary elements and literary devices are actually two very distinct things. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Literary elements

These are things that every single story needs to have in order to exist—they’re the architectural foundation. Without them, your story is like a house without any supports; it’ll collapse into a sad, lifeless pile of rubble, and you’ll hear your parents tossing around unfeeling words like “day job” when talking about your writing.

Literary devices

A literary device , on the other hand, refers to the many tools and literary techniques that a writer uses to bring a story to life for the reader. The difference is like the difference between making a home instead of merely building a house.

You can have a very simple story without any literary devices at all, but it would do little other than serve a functional purpose of showing a beginning, middle, and end. Literary devices are what bring that basic story scaffolding to life for the reader. They’re what make the story yours .

Some of the most common literary devices are things like metaphors, similes, imagery, language, and tons more. By experimenting with different literary devices and literary techniques in your own writing, you open up the full expanse of potential in creating literary works.

Once you’ve got a handle on the literary elements that we’re going to show you and how to apply them to your own narrative, you can check out our lesson on popular literary devices to find ways to bring new richness and depth to your work.

The 7 elements of literature

1. character.

The most fundamental of the literary elements, the root of all storytelling, is this: character .

No matter what species your main character belongs to, what their socio-ethno-economic background is, what planet they come from, or what time period they occupy, your characters will have innate needs and desires that we as human beings can see within ourselves. The longing for independence, the desire to be loved, the need to feel safe are all things that most of us have experienced and can relate to when presented through the filter of story.

The first step to using this literary element is easy, and what most new writers think of when they start thinking about characters. it’s simply asking yourself, who is this person? (And again, I’m using “person” in the broadest possible sense.) What makes them interesting? Why is this protagonist someone I might enjoy reading about?

The second step is a little harder. Ask yourself, what does this person want? To be chosen for their high school basketball team? To get accepted into a university across the country? To find a less stressful job?

The third step is the most difficult, and the most important. Ask yourself what they need . Do they want to join the basketball team because they need the approval of their parents? Do they want to move across the country because they need a fresh start in a new place? Do they want a new job because they need to feel that their contribution is valued?

Once you’re able to answer these questions you’ll already feel the bones of a narrative taking shape.

Types of characters you’ll find in every story

Since character is the primary building block of all good literature, you’ll want your character to be as engaging and true to real life as can be. Let’s take a quick look at some of the different character types you’ll encounter in your story world.

Protagonist

Your protagonist is the main character of your story. Often they’ll be the hero, but not always—antiheroes and complex morally grey leads make for interesting plots, too. This is the character through which your reader goes on a journey and learns the valuable lessons illustrated in your themes (more on theme down below).

Your antagonist is the person standing in the way of your protagonist’s goal. These two central characters have opposing desires, and it’s the conflict born out of that opposition that drives the events of the plot. Sometimes an antagonist will be a villain bent on world destruction, and sometimes it’ll be an average person who simply sees the world in a different way.

Supporting characters

Once you have those two essential leads, your story needs its supporting cast. This is where you get to have fun with other characters like friends, love interests, family dynamics, and a whole range of character archetypes that bring your story to life.

Foil characters

As a bonus, many stories may also feature foil characters. A foil character in literature refers to two characters who may or may not be at odds with each other, but are opposite in every way. This literary technique works effectively to highlight aspects of each character. Your foil characters may be the protagonist and the antagonist, or the protagonist and one of the supporting characters, or both.

Your setting is where , when , and to some degree how your story takes place. It’s also your character’s relationship with the world around them. A story setting might be as small as a cupboard under the stairs, or it might be as wide and vast as twenty thousand leagues of endless grey sea. A short story might have only one setting, the heart of where the story takes place; longer works such as novels will probably have several. You can use all five senses to develop your setting.

Setting often gets overlooked as a less important literary element than character, plot, or conflict, but in reality a setting can drive all of these things. So much of who we are is shaped by the social setting we grew up, the places we spend our time, the time period we grew up in, and major events of the time that impacted our cultural awareness. Your characters are no different.

Someone who has spent their life on a sprawling country estate bordering a dark and spooky wood will naturally grow into someone very different than someone living in the narrow back alleys of a noisy, gritty city—just as someone living in the Great Depression of the 1930s will grow to develop different habits and perspectives than someone living in the technological advancements of the late 1990s.

Layers of setting to explore in your writing

Setting isn’t just about place—it’s about building your story world from the ground up. Here are the three different layers of setting you’ll need to consider when crafting your tale.

Temporal settings

Temporal setting refers to the time in which your story is set. This means the period of history—whether that’s in contemporary times, at the turn of the century, or in a distant future—as well as the season of the year, time of day or night, and point in your protagonist’s life cycle.

Environmental settings

This is the wider world of your story—what fantasy and science-fiction writers call “worldbuilding.” It refers to the natural landscape your characters find themselves in as well as cultural, political, and socioeconomic values and the way your characters interact with those values.

Individual settings

This is the fine details of setting, and what we most often tend to think about when we consider setting in a story. These are the stages on which your story takes place: an elementary school, a police station, a city park, a pirate ship. Your story needs the support of temporal and environmental setting, but individual settings are what really bring the world to life.

3. Narrative

The way you’re telling your story to the reader is as essential as the story that’s being told. In literary terms, narrative is the perspective from which the events of the story are unfolding and the way that you, as the author, have chosen to communicate them.

Every single character brings a different perspective to the story. They may have prejudices, limitations, prior knowledge, or deep character flaws that colour the way they see the world around them.

Some stories stay with only one character throughout the entire journey; others may explore the thoughts and feelings of many. As an exercise, you may want to try writing a story from multiple perspectives to gain a better understanding of your story world. You’d be surprised how much you can learn about your characters that you never imagined.

Types of PoV used in fiction writing

Point of view, or PoV, is one of the most important choices a writer makes when beginning a new work of fiction. Here’s a quick overview of the different points of view you’ll find in all narratives.

First Person Subjective

First person narratives are written from the character’s point of view (or the PoV of multiple characters) as if they were speaking directly to the reader. You’ll use statements like “I saw a shadow move from the corner of my eye,” or, “and then he told me that it was over.” First person subjective PoV takes the reader into the mind of the character and shows us everything they’re thinking and feeling.

First Person Objective

First person objective is very similar because it’s also from the character’s perspective and uses “I” and “me” statements. The difference is that the objective PoV doesn’t show the character’s internal thoughts and feelings—only their actions. This gives the reader an outside perspective and makes them feel like they’re watching video footage of the story, deducing what’s happening under the surface from the events of the plot.

Second Person

Second person PoV has a lot in common with first person, but instead of being told from the main character’s perspective, it’s told from the reader’s—this allows the reader to become the person telling the story. You may remember this from “Choose Your Own Adventure” books. In second person narration, you’ll use statements like “you turn a corner and find yourself staring at a door you’ve never seen.” This is challenging to do well, but a fun creative exercise for any writer.

Third Person Limited Subjective

Third person points of view are the most classic in literature; they use “he,” “she,” or “they” to follow the characters’ journeys. In a limited subjective point of view, you’ll allow the reader to experience the thoughts and feelings of your protagonist—but no one else. This is a common narrative choice in mystery novels.

Third Person Objective

Third person objective is pretty similar to first person objective, but it uses the third person pronouns. The reader won’t experience anything the characters are thinking or feeling except through their actions and the choices that they make, leaving the true undercurrents of the story to the reader’s imagination.

Third Person Multiple Subjective

This perspective works like third person limited subjective, in that it takes the reader into the minds of the characters using the pronouns “he,” “she,” or “they.” The difference is that the reader gets to see into more than one character—but only one at any given moment. This might involve chapters that alternate between one character and another, or a story that shows two different timelines with protagonists for each one.

Third Person Omniscient

This perspective is very similar to third person multiple subjective, but it allows the reader to see into more than one character’s thoughts in the same moment. The third person omniscient creates a “mental dollhouse” effect in which the internal workings of everyone on stage is exposed to the reader.

In a literary text, the plot is the sequence of events that takes the protagonist on a journey —whether that’s a literal journey from one place to another, a journey in which they learn how something came to be, or a journey in which they learn something about themselves. Some stories may be all of these things.

How your protagonist reacts to the events around them and the choices that they make come from the things they want and the things they need—we looked at that a little bit in character, above. Most of these stories will fall into one of a few classic plot structures that have been shown to resonate with us on a deep, instinctual level. And every one of these plot structures will use several essential plot points.

Important plot points every story needs

There’s a number of different ways to approach the plot of your story, but you’ll find that most of them follow the same general sequence of events from the inciting incident, or the first key plot point, to the denouement. Let’s look at the different stages that a good story will pass through from beginning to end.

Inciting incident

The inciting incident is the event that changes the protagonist’s life and sends them on a different path than the one they were on before. This will be the first major plot point of every story, and is essential for grabbing the reader’s attention. A good example might be if a mysterious new stranger enters the protagonist’s life.

Rising action

During the first half of your story, your characters will encounter several challenges on their way to achieving their goal (the one set into motion by the inciting incident). These “mini battles” form the rising action of a story.

The climax is the great showdown between the protagonist and their adversary, the moment of greatest triumph and greatest loss. Everything your characters have learned through the rising action has led to this moment.

Falling action

After the final battle, your characters need to adjust to the new landscape of their world. During the falling action, you’ll show the reader how the effects of the rising action and the climax reverberate into the characters’ lives.

The denouement is the final scene of any story that wraps up all the lingering threads and answers any unaddressed questions. A well-written denouement will leave the reader feeling satisfied as they close the book.

5. Conflict

When looking at the events that make up your plot, all of the choices your character needs to make will be in response to the literary element we call “conflict.” This makes it one of the most essential literary elements in literature. This might be a conflict with another person, a conflict inside themselves, or a conflict with their environment. It might be all of these things. There’s a reason we close the book after “happily ever after”; once there’s no more conflict, the story has run its course and there’s nothing more to say.

In a story, your protagonist should always have something to fight for. After you’ve determined what they want and what they need most, ask yourself what’s standing in their way. What steps can they take to overcome this obstacle? And—this is a big one— what do they stand to lose if they fail?

How your protagonist reacts to these conflicts shows a lot about who they are as a person. As the story progresses and your character grows, the way they handle these conflicts will probably change—they’ll start taking an active role in moving the story along, rather than a passive one.

Types of conflict that drive your characters

Conflict is essential to a good story, but it can be so much more than simply pitting a hero against a villain. Let’s look at the different kinds of conflict that drive a story forward.

Character vs. Character

Above, we looked at how antagonists can be central characters in a good narrative. This type of conflict sets a person against another person, usually the classic bad guys of literature, and watches their opposing needs play out. These will usually be the main characters of the literary work.

Character vs. Self

Sometimes, a protagonist’s obstacle comes from within. This might be something like addiction, alcoholism, fear, or other forms of self-sabotage. This type of conflict shows the main character fighting and ultimately overcoming their central weakness.

Character vs. Society

This type of conflict sets an individual protagonist against the larger world. Stories that deal in difficult themes like racism, homophobia, misogyny, or class divides often focus on this conflict. (We’ll look a little more at theme down below.)

Character vs. Nature

A beloved mainstay of hollywood blockbusters, this type of conflict sets the protagonist against an impersonal force of the natural world—an animal, a natural disaster, or illness.

Theme as a literary element is something that makes both readers and writers a little cautious. After all, doesn’t worrying about developing and understanding a theme take some of the enjoyment out of stories? Well no, it shouldn’t, because themes are present in all works of art whether they were put there intentionally or not. Theme is simply the sum of what the creator was trying to communicate with their work.

Neil Gaiman approached the idea of theme very nicely by asking one simple question: “What’s it about?” What’s this story really about? Underneath all the explosions and secrets and tense kisses and whatever else makes your plot go forward, maybe it’s really a story about family. Or injustice. Or maybe it’s about being there for your best friend even when they screw up really, really bad.

Contrary to popular belief, your theme isn’t an extra layer you add to give depth and richness to the plot. Your theme is the story’s heart —the reason it exists.

Your central theme probably isn’t where the story comes from, at least not initially. Most likely it’s something you’ll discover along the way as the story’s central message becomes clearer through the actions of your characters. It might be an abstract idea, or a lesson you want to share with the world.

Then, once you find this idea taking shape in your mind, you can double back and add in literary devices, details, figurative language, motifs, and relationships that support this heart of the story. Voilà —now it looks like you knew what you were doing all along.

Examples of classic themes in literature

A story’s theme is the central axis of every literary work. Sometimes you’ll find you have multiple themes present in one story, each supporting and underlining the other. Here’s a list of common themes you’ll find across literature.

Central idea themes

Disillusionment

Opposing principle themes

Good vs. Evil

Individual vs. Society

Life vs. Death

Fate vs. Free Will

Tradition vs. Change

Pride vs. Humility

Justice vs. Depravity

Morality vs. Fear

A writer’s voice is something that no guidebook can give you; it’s simply what’s left after everything that’s not your voice has been worn away.

Think of it this way: the work of new writers is usually a spark of an idea (sometimes original, sometimes not) encrusted with everything they’ve ever read. They may be trying to emulate writers who have written things that they’ve resonated with, or they may have simply absorbed those things subconsciously and are now watching them leak out of their fingers as they write.

That’s not to say that writing literature in the style of other craftsmen before you is a negative thing; in fact, it’s how we learn to master the storytelling craft of our own. This is how we try things and find them delightful, or we try things and find that, for some reason or another, they don’t quite settle into our bones the way we’d like them too. Those pieces get discarded, and we continue to grow.

Every time you write something, you’re essentially working in the dark to smooth down the rough gem that will become your storytelling voice. Little by little it takes shape, and one day you read over something you’ve written and are surprised by the thought, “Hey! That sounds like me .”

There’s no formula to this, unfortunately. A writer develops this core literary element simply by doing, by trying, by experimenting with word choice and by being aware of what works and what doesn’t and why.

Once you have this your stories become something that is intimately yours, and no one else’s, even as you grow and share those stories with the world.

Tips for developing your writer’s voice

A writer’s voice can only be found by practicing your own writing and looking inwards, but here’s a few tips to keep in mind that will help you uncover and refine your signature voice.

Read everything

The best way to find your unique voice as a writer is by reading the work of others who have gone before you. This will help you immerse in different styles, sentence structures, and literary devices to find which ones feel like a natural fit.

Try on other writers

As an exercise, try emulating the style of different writers. By experimenting with the different narrative structures in literary works that you’ve read, you’ll be able to refine the parts that feel like you and discard the ones that don’t.

Experiment with structure

Another great exercise is experimenting with specific story archetypes and writing prompts. By imposing restraints on a piece of narrative work, you’ll be able to see how your own natural writer’s voice breaks through.

How to use literary elements to write a great story

There are as many ways to begin a story as there are storytellers. We’ve reviewed the seven literary elements that are the basic building blocks of all good stories:

We’ve looked at how characters are the lifeblood of every story; how our characters are shaped by their world, or setting; how characters reveal themselves through the events of the plot; how plot is powered by a series made of choices in response to conflict; how the underlying theme of your story is at the heart of every choice your character makes; and how their unique perspective and your unique perspective come together to tell the story in a way that only you can.

The truth is, every single one of these literary elements is an essential piece of a perfect, interwoven whole.