This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Abdolrahimi M, Ghiyasvandian S, Zakerimoghadam M, Ebadi A. Therapeutic communication in nursing student: a Walker and Avant concept analysis. Electron Physician.. 2017; 9:(8)4968-4977 https://doi.org/10.19082/4968

Communication skills 1: benefits of effective communication for patients. 2017. https://tinyurl.com/y3nzu222 (accessed 10 August 2020)

Communication skills 3: non-verbal communication. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y5ay4uhd (accessed 10 August 2020)

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev.. 1977; 84:191-215 https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Barratt J. Developing clinical reasoning and effective communication skills in advanced practice. Nurs Stand.. 2019; 34:(2)37-44 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11109

Bergdahl E, Berterö CM. Concept analysis and the building blocks of theory: misconceptions regarding theory development. J Adv Nurs.. 2016; 72:(10)2558-2566 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13002

Bloomfield J, Pegram A. Care, compassion and communication. Nurs Stand.. 2015; 29:(25)45-50 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.25.45.e7653

Bramhall E. Effective communication skills in nursing practice. Nurs Stand.. 2014; 29:(14)53-59 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.14.53.e9355

Brown R. An analysis of loneliness as a concept of importance for dying persons. In: McKenna H, Cutcliffe J (eds). Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005

Burley D. Better communication in the emergency department. Emerg Nurse.. 2011; 19:(2)32-36 https://doi.org/10.7748/en2011.05.19.2.32.c8509

Cambridge University Press. Effective. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y7dqcypc (accessed 10 August 2020)

Campbell JD, Lavallee LF. Who am I? The role of self-concept confusion in understanding the behavior of people with low self-esteem. In: Baumeister RF (ed). New York (NY): Plenum Press; 1993

Carment DW, Miles CG, Cervin VB. Persuasiveness and persuasibility as related to intelligence and extraversion. Br J Soc Clin Psychol.. 1965; 4:(1)1-7 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1965.tb00433.x

Casey A, Wallis A. Effective communication: principle of nursing practice E. Nurs Stand.. 2011; 25:(32)35-37 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2011.04.25.32.35.c8450

Daly L. Effective communication with older adults. Nurs Stand.. 2017; 31:(41)55-62 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2017.e10832

Department of Health and Social Care. Essence of care 2010: benchmarks for the fundamental aspects of care. 2010. https://tinyurl.com/y3z8grqe (accessed 10 August 2020)

Dithole KS, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Akpor AO, Moleki MM. Communication skills intervention: promoting effective communication between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Nurs.. 2017; 16:(74)1-6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0268-5

Draper P. A critique of concept analysis. J Adv Nurs.. 2014; 70:(6)1207-1208 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12280

Duldt BW, Giffin K, Patton BR. Interpersonal communication in nursing: a humanistic approach.Philadelphia (PA): FA Davis; 1983

Fakhr-Movahedi A, Salsali M, Negharandeh R, Rahnavard Z. Exploring contextual factors of the nurse-patient relationship: a qualitative study. Koomesh.. 2011; 13:(1)23-34

Fleischer S, Berg A, Zimmermann M, Wuste K, Behrens J. Nurse-patient interaction and communication: a systematic literature review. J Public Health.. 2009; 17:339-353 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-008-0238-1

Foley A, Davis A. A guide to concept analysis. Clin Nurse Spec.. 2017; 31:(2)70-73 https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000277

Gadamer HG. Philosophical hermeneutics. Translated by DE Linge.Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1976

Gallagher L. Continuing education in nursing: a concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today.. 2007; 27:(5)466-473 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.08.007

Ghafouri R, Rafii F, Oskouie F, Parvizy S, Mohammadi N. Nursing professional regulation: Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016; 5:(9S)436-442

Griffiths J. Person-centred communication for emotional support in district nursing: SAGE and THYME model. Br J Community Nurs.. 2017; 22:(12)593-597 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.12.593

Hazzard A, Harris W, Howell D. Taking care: practice and philosophy of communication in a critical care follow-up clinic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs.. 2013; 29:(3)158-165 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2013.01.003

Jevon P. Clinical examination skills.Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publications; 2009

Jones A. The foundation of good nursing practice: effective communication. J Renal Nurs.. 2012; 4:(1)37-41 https://doi.org/10.12968/jorn.2012.4.1.37

Kelton D, Davis C. The art of effective communication. Nurs Made Incred Easy.. 2013; 11:(1)55-56 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NME.0000423378.98763.96

Kourkouta L, Papathanasiou IV. Communication in nursing practice. Mater Sociomed.. 2014; 26:(1)65-67 https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2014.26.65-67

McCabe C. Nurse patient communication: an exploration of patients' experiences. J Clin Nurs.. 2004; 13:41-49 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00817.x

McCabe C, Timmins F. Communication skills for nursing practice, 2nd edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2013

McCarthy DM, Buckley BA, Engel KG, Forth VE, Adams JG, Cameron KA. Understanding patient-provider conversations: what are we talking about?. Acad Emerg Med.. 2013; 20:(5)441-448 https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12138

McCroskey JC, Richmond VP. Willingness to communicate: differing cultural perspectives. South Commun J.. 1990; 56:(1)72-77 https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949009372817

McCuster M. Apathy: who cares? A concept analysis. Ment Health Nurs.. 2015; 36:693-697 https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1022844

McKenna HP. Nursing theories and models.London: Routledge; 1997

McKinnon J. The case for concordance: value and application in nursing practice. Br J Nurs.. 2013; 22:(13)16-21 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.13.766

Miller L. Effective communication with older people. Nurs Stand.. 2002; 17:(9)45-50 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2002.11.17.9.45.c3298

Newell S, Jordan Z. The patient experience of patient-centered communication with nurses in the hospital settings: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep.. 2015; 13:(1)76-87 https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1072

Norouzinia R, Aghabarari M, Shiri M, Karimi M, Samami E. Communication barriers perceived by nurses and patients. Glob J Health Sci.. 2016; 8:(6)65-74 https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p65

Nuopponen A. Methods of concept analysis: a comparative study. LSP.. 2010; 1:(1)4-12

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The code: professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/zy7syuo (accessed 10 August 2020)

O'Hagan S, Manias E, Elder C What counts as effective communication in nursing? Evidence from nurse educators' and clinicians' feedback on nurse interactions with simulated patients. J Adv Nurs.. 2013; 70:(6)1344-1355 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12296

Orem DE. Nursing: concepts of practice, 4th edn. St. Louis (MO): Mosby-Year Book; 1991

Oxford University Press. Communication. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y7k22yxb (accessed 10 August 2020)

Communication barriers. 2016. https://tinyurl.com/y3sn342h (accessed 10 August 2020)

Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf.. 2014; 23:(8)678-689 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437

Rodgers BL. Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: the evolutionary cycle. J Adv Nurs.. 1989; 14:(4)330-335 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03420.x

Rodgers BL, Knafi KA. Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques and applications, 2nd edn. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders; 2000

Royal College of Nursing. Communication-end of life care. 2015. https://tinyurl.com/go28vsm (accessed 10 August 2020)

Schirmer JM, Mauksch L, Lang F Assessing communication competence: a review of current tools. Fam Med.. 2005; 37:(3)184-192

Skär L, Söderberg S. Patients' complaints regarding healthcare encounters and communication. Nurs Open.. 2018; 5:(2)224-232 https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.132

Snowden A, Martin C, Mathers B, Donnell A. Concordance: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs.. 2014; 70:(1)46-59 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12147

Tay LH, Ang E, Hegney D. Nurses' perceptions of the barriers in effective communication with inpatient cancer adults in Singapore. J Clin Nurs. 2011; 21:(17-18)2647-2658 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03977.x

Thompson CJ. Nursing theory and philosophy terms: a guide.South Fork (CO): CJT Consulting and Education; 2017

Tofthagen R, Fagerstrøm LM. Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis – a valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010; 24:21-31 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00845.x

Nursing, admission assessment and examination. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y4ykv2uo (accessed 10 August 2020)

Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing, 5th edn. Norwalk (CT): Appleton and Lange; 2011

Webb L. Exploring the characteristics of effective communicators in healthcare. Nurs Stand.. 2018; 33:(9)47-51 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11157

Wikström B, Svidén G. Exploring communication skills training in undergraduate nurse education by means of a curriculum. Nurs Rep.. 2011; 1:(1) https://doi.org/10.4081/nursrep.2011.e7

Effective communication between nurses and patients: an evolutionary concept analysis

Dorothy Afriyie

Student Nurse, University of West London, Brentford

View articles · Email Dorothy

Communication can be considered as the basis of the nurse-patient relationship and is an essential element in building trust and comfort in nursing care. Effective communication is a fundamental but complex concept in nursing practice. This concept analysis aims to clarify effective communication and its impact on patient care using Rodgers's (1989) evolutionary framework of concept analysis. Effective communication between nurses and patients is presented along with surrogate terms, attributes, antecedents, consequences, related concepts and a model case. Effective communication was identified to be a multifactorial concept and defines as a mutual agreement between nurses and patients. This influences the nursing process, clinical reasoning and decision-making. Consequently, promotes high-quality nursing care, positive patient outcome and patient's and nurse's satisfaction of care.

Communication is an essential element of building trust and comfort in nursing, and it is the basis of the nurse–patient relationship ( Dithole et al, 2017 ). Communication is a complex phenomenon in nursing and is influenced by multiple factors, such as relationship, mood, time, space, culture, facial expression, gestures, personal understanding and perception ( McCarthy et al, 2013 ; Kourkouta and Papathanasiou, 2014 ). Effective communication has been linked to improved quality of care, patient satisfaction and adherence to care, leading to positive health outcomes ( Burley, 2011 ; Kelton and Davis, 2013 ; Ali, 2017 ; Skär and Söderberg, 2018 ). It is an important part of nursing practice and is associated with health promotion and prevention, health education, therapy and treatment as well as rehabilitation ( Fakhr-Movahedi et al, 2011 ). The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2018) emphasised effective communication as one of the most important professional and ethical nursing traits. Nonetheless, communication remains a complicated phenomenon in nursing, and most patient-reported complaints in healthcare are around failed communication ( Reader et al, 2014 ). The aim of the present concept analysis is to explore and clarify the complexity of establishing effective communication between nurses and patients in practice.

Concept analysis

Concept analysis is the foundation and preparatory phase of nursing research ( Walker and Avant, 2011 ). Concept analysis aids in clarifying concepts in nursing by using simpler elements to reduce ambiguity and identify all aspects of a concept ( Nuopponen, 2010 ; Foley and Davis, 2017 ). Draper (2014) criticised concept analysis as being methodologically weak and philosophically dubious, further arguing that there is no evidence of its contribution to patient care. However, concept analysis facilitates the review of literature on a concept of interest, thereby enabling a thorough examination of the concept ( Bergdahl and Berterö, 2016 ). This helps in understanding the concept and, therefore, applying it appropriately. Correspondingly, understanding key concepts in nursing practice enables the nurse to identify strategic interventions that could benefit patients. Although McKenna (1997) argued that there is no definite meaning of a concept because they are experienced and perceived differently by people, Walker and Avant (2011) highlighted that the ability of the nurse to describe concepts in an exploratory way is an important means to demonstrate evidence base in practice. Nursing is an evidence-based practice; hence it is the responsibility of the nurse to keep up-to-date with quality evidence and demonstrate it in practice ( Thompson, 2017 ). Therefore, it is paramount for nurses to understand concept analysis and be able to analyse key concepts in nursing.

This concept analysis aims to clarify the concept of effective communication and address the gap in knowledge using Rodgers's (1989) theoretical framework. The evolutionary method of concept analysis was chosen because it adopts a systematic approach with focused phases ( Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm, 2010 ). Rodgers's (1989) method is perceived as a simultaneous task approach, which does not seek boundaries to restrict a concept and considers its application within multiple contexts ( Gallagher, 2007 ). However, the framework will be used because it facilitates an exploration and deep comprehension of a concept ( McCuster, 2015 ). Additionally, the framework offers an alternative to a positivist approach to concepts, allowing different findings depending on the situation ( Ghafouri et al, 2016 ). Moreover, the framework provides an opportunity to identify attributes and related features in a manner that minimises bias ( McCuster, 2015 ). Effective communication between patients and nurses was analysed using the seven phases of Rodgers's (1989) evolutionary method ( Box 1A ). Further, the following four questions were addressed ( Box 1B ).

Box 1A.Rodgers's method of analysis (1989)

Box 1B.Rationale for the four focused questionsThe focus questions were driven by the Rodgers's (1989) framework of concept analysis; the four questions are aimed at analysing the concept of effective communication using the seven stages of the framework in a systematic manner to engender an understanding of effective communication

- What is effective communication?

- What are the surrogate terms and related use of the concept of effective communication?

- What attributes, antecedents and consequences apply to the concept of effective communication?

- Who benefits from effective communication between nurses and patients?

Identifying the appropriate realm for data collection

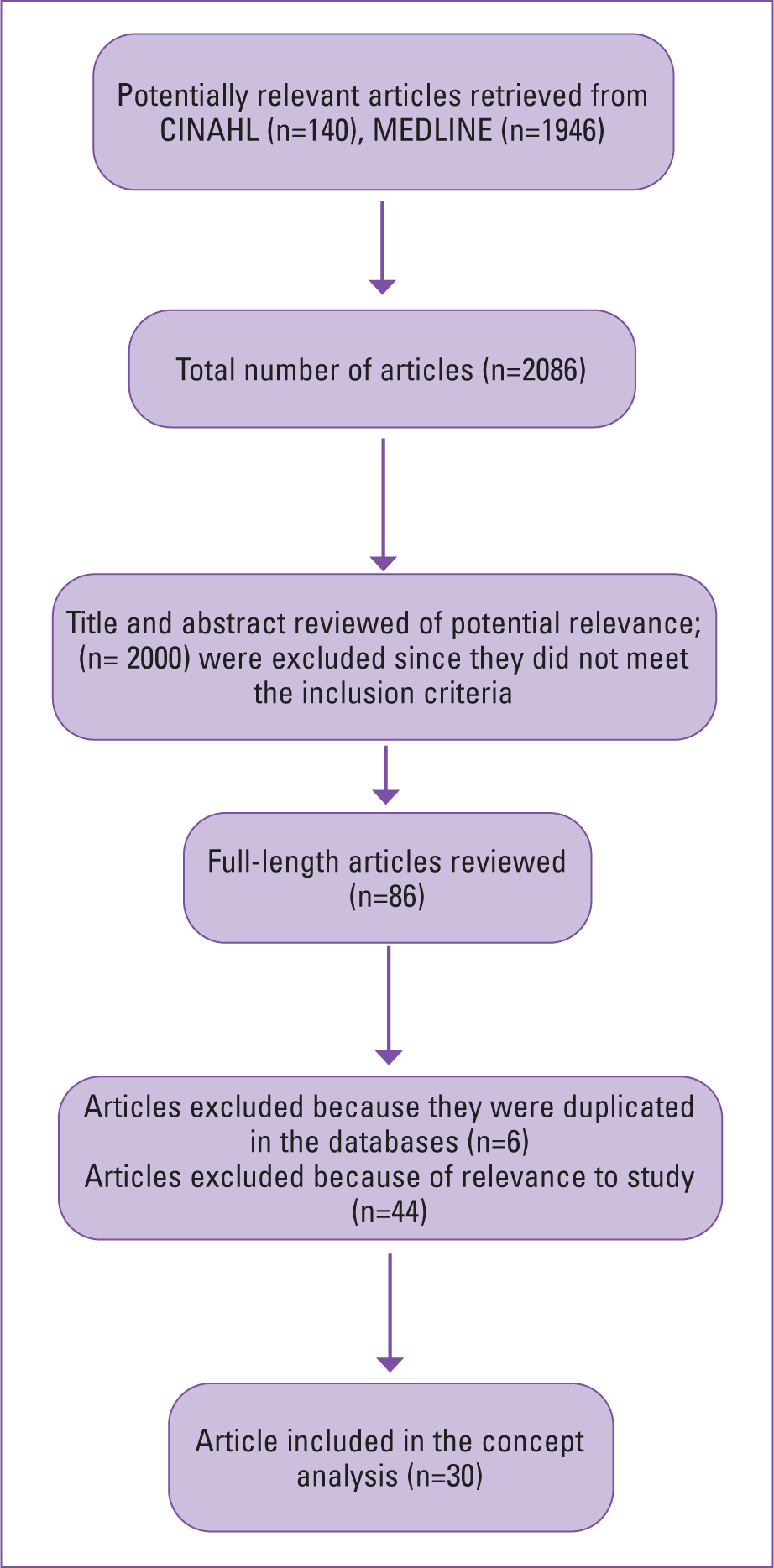

As endorsed by Brown (2005) , a comprehensive review of the literature was conducted for this analysis. Explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to select relevant articles, as recommended by Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm (2010) . Two electronic databases-Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) and MEDLINE (Ovid)-were searched using the keywords ‘effective communication’ and ‘nurses’ and ‘patients’. The inclusion criteria allowed selection of only peer-reviewed academic journals written in the English language. Studies exploring or analysing effective communication among nurses and patients with underlying communication difficulties and cognitive disabilities were excluded, because it is likely that such patients or nurses represent a special challenge in communicating. Only articles exploring effective communication and factors that influence communication between nurses and patients were considered. A total of 2086 articles were retrieved from the databases, and these articles were screened for relevance by reading the abstract. Finally, 30 articles were determined to meet the inclusion criteria for the analysis ( Figure 1 ). The articles selected were published between 1965 and 2019.

Defining effective communication

The Cambridge English dictionary defines ‘effective’ as ‘successful or achieving the results that you want’ ( Cambridge University Press, 2018 ). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, communication is ‘imparting or exchanging information by speaking, writing or using some other medium’ ( Oxford University Press, 2018 ). The Department of Health and Social Care (2010) described communication as the meaningful exchange of facts, needs, opinions, thoughts, feelings or other information between two or more people. Further, communication can be face-to-face, over the phone or by written words. McCabe and Timmins (2013) also described communication as a cyclical and dynamic process, involving transmission, receiving and interpretation of information between people using verbal or non-verbal means. Rani (2016) simply described communication as ‘sharing meaning’.

Interestingly, Hazzard et al (2013) described communication as a primary condition of human consciousness. They further explained that people always identify themselves in a communicative state. This would imply that people are always exchanging information. The authors, however, described communication as the actions taken after speaking to someone; this highlights communication as responsive. This may be the action and reaction people adopt after a communicated request or statement. Nonetheless, Gadamer (1976) , a twentieth-century philosopher, highlighted communication as what we are and not just what we do. Kourkouta and Papathanasiou (2014) defined communication as the use of speech or other means to exchange information, thoughts and feelings among people. Therefore, effective communication may be classified as exchanging information, thoughts and feelings using either verbal or non-verbal expressions to successfully produce a desired or intended result.

Effective communication between nurses and patients may be analysed from both the nurse's and the patient's perspective. McCabe (2004) identified that the patients' perspective of effective communication entails patient-centred interaction. On the other hand, O'Hagan et al (2013) found that nurses' perspective of effective communication revolves around time, task, rapport and patients' agreement on what has been communicated. Although both perspectives appear to differ, they are both driven by the expectations of the patient and nurse. A nurse may ultimately identify effective communication as the ability to engage with patients and to achieve clinical goals. Similarly, patients may be influenced by their expectation regarding their management outcome ( Schirmer et al, 2005 ). Therefore, effective communication between nurses and patients may be defined as mutual agreement and satisfaction with care (provided and received).

Surrogate terms and relevant uses

The terms most commonly serving a manifestation of effective communication include: therapeutic communication, interpersonal relationship, intercommunication, interpersonal communication and concordance. From a literature search, these terms appear frequently, highlighting their close usage with the concept of effective communication ( Fleischer et al, 2009 ; Casey and Wallis, 2011 ; Jones, 2012 ; Bloomfield and Pegram, 2015 ; Daly, 2017 ). For example, through intercommunication or interpersonal communication, a nurse can encourage a patient to participate in their care decision-making. However, a patient's acceptance to engage in shared decision-making regarding care and agree with a negotiated care plan could reflect effective communication. This act of mutual agreement through negotiation and shared decision-making suggests concordance ( Mckinnon, 2013 ; Snowden et al, 2014 ). Abdolrahimi et al (2017) pointed out that therapeutic communication is the basis for effective communication. They highlighted therapeutic communication as an important means for establishing interpersonal relationships. These concepts are different from effective communication; however, these notions express an idea of the concept of effective communication and highlight an understanding of effective communication as emphasised by Rodgers (1989) .

Daly (2017) described communication as dynamic and cyclical, because it involves a process of transmission, receiving and interpretation through verbal or non-verbal means. This reflects the complexity of communication, which involves speaking, being heard, listening, understanding or being accepted, as well as being seen and acknowledged. Hence, assessing factors that could affect communication, such as noise or interference, is always crucial for effective communication ( McCabe and Timmins, 2013 ; Webb, 2018 ). Daly (2017) explained that other skills for effective communication, which are consciousness, compassion, competence, professionalism and person-centredness, are all important concepts in nursing studies and practice. This indicates that communication is intentional in nature, so the purpose and perspective of individuals involved should be valued and respected ( Jones, 2012 ). In the case of the nurse–patient relationship, a nurse must consider a patient's perspective, background and concerns when communicating. It is important for a nurse to be competent, ethical and professional and exhibit an individualised approach in communicating with patients ( Bramhall, 2014 ; Bloomfield and Pegram, 2015 ). For example, when communicating with a patient with no medical background, medical terms should be explained further or avoided. This promotes person-centredness, which is a determinant for effective communication for patients.

A nurse must respect human rights and be professional ( NMC, 2018 ). However, it can be challenging when communicating with a patient who does not want to communicate about their health, which reflects their right to autonomy. Nonetheless, it is paramount for a nurse to identify the purpose of communication and the difficulties, so that they can mitigate them as part of their professional and ethical duties ( Royal College of Nursing, 2015 ; NMC, 2018 ). This can be done by reassuring and encouraging patients. Correspondingly, this act of communication features in Duldt et al's (1983) theory of humanistic nursing communication. This theory is reflected in Bramhall (2014) and Kourkouta and Papathanasiou's (2014) exploration on communication in nursing. The theory explains the need for comprehensive and exclusive communication among nurses and clients as well as colleagues. The focus of the theory is on interpersonal communication and emphasises the need for humanistic approaches to help improve professional communication. These approaches include empathy, deeper respect, encouragement and interpersonal relationship. For example, listening to people, providing privacy when communicating, giving patients ample time, using kind and courteous words such as ‘please’ and ‘thank you’, as well as being frank and honest when communicating. All these approaches may promote effective communication between nurses and patients ( Jevon, 2009 ; Bramhall, 2014 ; Bloomfield and Pegram, 2015 ).

Further, Miller (2002) , Burley (2011) , Casey and Wallis (2011) , Jones (2012) Bloomfield and Pegram (2015) and Daly (2017) demonstrated how effective communication is key in the assessment, planning and implementation of personalised nursing care. Holistic assessment in nursing includes history-taking, general appearance, physical examination, vital signs and documentation ( Toney-Butler and Unison-Pace, 2018 ). Patient assessment aids in identifying the communication needs of a patient in order to promote person-centred care ( Toney-Butler and Unison-Pace, 2018 ). Moreover, non-verbal cues such as general appearance or posture are vital in communication, and understanding them could help in the assessment process. General appearance such as facial expressions, dressing, hair or skin integrity may convey information that may be helpful in the nursing assessment process. Although not ideal, however, appearance can be a powerful transmitter of intentional or unintentional messages ( Ali, 2018 ). For instance, a nurse may sense neglect or abuse when a patient appears physically unkempt, with bruises or sores. This may inform the nurse on appropriate questions to ask during history-taking in order to ascertain the patient's situation and safeguard, signpost or refer them for support if necessary. Nurses' ability to identify these concerns may aid in providing the best necessary care for their patients. This promotes person-centredness, which is perceived as a means of effective communication by patients ( McCabe, 2004 ).

Effective communication promotes comprehensive history-taking. History-taking involves communicating with patients to collect subjective data and using this information to determine management plans ( Jevon, 2009 ). In history-taking, inaccurate information may be collected when communication is not effective ( Burley, 2011 ; Jones, 2012 ; Daly, 2017 ). However, it is important for nurses to establish good personal relationships with patients, so the latter can feel comfortable in sharing their complaints ( Casey and Wallis, 2011 ). It needs to be noted that, since patients are experts in their own lives, the nurse's ability to make patients feel comfortable may encourage patients to share valuable information, as well as their expectations, concerns and fears. Effective communication is important if nurses are to implement their roles effectively with regard to holistic assessment, considering the subjective experience and characteristics of their patient. Further, a well-informed collaborative assessment through effective communication may contribute to positive patient management outcomes ( Kourkouta and Papathanasiou, 2014 ). For instance, a patient may convey all necessary information to a nurse during assessment, and this may inform the nurse and patient of the necessary examination and investigations to aid in evidence-based nursing diagnosis and a collaborative management plan. The ability to establish a mutual agreement for the nursing process suggests effective communication for both parties.

Effective communication aids in planning and implementing personalised care. It helps patients to set realistic goals and choose preferred management for better outcomes. Communication is a bidirectional process in which a sender becomes a receiver and vice versa ( Kourkouta and Papathanasiou, 2014 ). Therefore, there is a need for both patients and nurses to realise that they are partners in communicating care planning and implementation ( Bloomfield and Pegram, 2015 ). This realisation may promote the patient's dignity and may also influence patients' desire to adhere to their plan when they feel involved in decision-making ( Casey and Wallis, 2011 ). Conversely, patients may be reluctant and unhappy if they feel dictated to or patronised. Most importantly, involving patients through effective communication can empower them to have full control over their health and wellbeing. This is reflected in the self-care theory proposed by Orem (1991) and the theory of self-efficacy proposed by Bandura (1977) . These theories focus on the role of the individual in initiating and sustaining change and healthy behaviours. Orem (1991) reinforced the importance of communication, as self-care is learned through communication and interpersonal relationships.

Attributes of effective communication

Certain attributes can be used to develop a definition of effective communication that is more realistically reflective of how patients and nurses use the term in healthcare settings ( Rodgers and Knafi, 2000 ). The most common attributes identified in the literature include: effective communication as ‘a building foundation for interpersonal-relationship’, ‘a determinant of promoting respect and dignity’, ‘a precedent of achieving concordance’, ‘an important tool in empowering self-care in patient’, ‘a significant tool in planning and implementing person-centred care’ and ‘a determinant of clinical reasoning and the nursing process’ ( Casey and Wallis, 2011 ; Jones, 2012 ; McCabe and Timmins, 2013 ; Bramhall, 2014 ; Bloomfield and Pegram, 2015 ; Daly, 2017 ; Webb, 2018 ; Barratt, 2019 ). These attributes make it possible to identify situations that can be categorised under the concept of effective communication.

Antecedents of effective communication

According to the literature, antecedents to effective communication include: personality trait, perceived communication competence and level of education on communication. Personality traits were linked with communication in early research. Carment et al (1965) demonstrated that people who are introverts are less likely to communicate well compared with extroverts. McCroskey and Richmond (1990) also indicated that people with low self-esteem are less willing to communicate. This is because they are more sensitive to environmental cues ( Campbell and Lavallee, 1993 ). Additionally, McCroskey and Richmond (1990) asserted that people who perceived themselves as poor communicators may be less willing to communicate. Nonetheless, people who may be very capable of communicating may not be willing to, due to low self-esteem, anxiety or fear. As a result, such people may have low communication efficacy despite having high actual competence ( McCroskey and Richmond, 1990 ). Therefore, it is important for nurses to consider these factors when communicating with patients in order to identify their communication needs and manage them accordingly ( Daly, 2017 ). Furthermore, Dithole et al (2017) and Norouzinia et al (2016) highlighted that the nurse's level of education on communication may influence the ability to communicate effectively. Thus, incorporation of targeted communication skills education in the training curriculum and on-the-job training will empower nurses to communicate effectively with their patients.

Consequences of effective communication

The consequences of effective communication can be classified into patient–nurse-related and healthcare system-related outcomes. Skär and Söderberg (2018) mentioned that effective communication ensures a good healthcare encounter for patients. In the community settings, effective communication empowers patients to talk about their concerns and expectations ( Griffiths, 2017 ). Further, effective communication promotes a pleasant and comfortable hospital experience for patients as well as their families; this can also be reflected in the community settings, where patients may report pleasant and comfortable nursing care ( Newell and Jordan, 2015 ; Barratt, 2019 ). Kourkouta and Papathanasiou (2014) and Wikström and Svidén (2011) pointed out that the success of a nurse mostly depends on how effectively they can communicate with their patient. Conversely, ineffective communication may lead to unsuccessful outcomes. For example, a patient may convey their fears, signs and symptoms to a nurse and how the nurse decodes and applies the information may influence the intervention given ( Kourkouta and Papathanasiou, 2014 ). Likewise, a nurse may convey a piece of information to a patient, but the patient's understanding of the information will determine their action. Therefore, how the message is understood determines the action taken ( Kourkouta and Papathanasiou, 2014 ). Additionally, through effective communication, a patient may be empowered to have full control over their health and wellbeing ( Newell and Jordan, 2015 ) and may not require extended care. Clearly, effective communication can lead to positive and cost-saving consequences for patients, nurses and the healthcare system.

The final phase of Rodgers's (1989) method of analysis highlights an application of the concept in an exploratory case scenario. A model case for effective communication between a nurse and a patient is given in Box 2 . This case portrays effective communication between a nurse and a patient, revealing some surrogate terms, defining attributes, antecedents and consequences of the concept. The case model highlighted Audrey's positive engagement in her care decision-making when the nurse Dani communicated effectively. Dani visited Audrey in her home, where Audrey had spatial and environmental control, but she was reluctant to engage in her own care. Audrey perceived that other nurses did not involve her in her care decision-making. This indicates ineffective communication and may be attributed to factors such as age difference, generational gap, gender and culture and ethnic differences between Audrey and the other nurses ( Tay et al, 2011 ; Norouzinia et al, 2016 ).

Box 2.Model caseAudrey, a 90-year-old housebound patient with bilateral leg ulcers was visited by Dani, a 45-year-old community staff nurse working in a diverse multicultural district nursing team. On arrival, Dani introduced herself in a suitable tone, maintaining eye contact. Audrey responded in a low tone, without maintaining eye contact. Audrey appeared to be quiet and in a low mood; Dani identified this nonverbal cue and was determined to engage Audrey in conversation. Dani knew from her experience that leg ulcer treatment can affect a person's mental health, causing low self-esteem, fear and anxiety. Dani asked how Audrey felt and if there was something she could help her with. Audrey mentioned she was fine; her carers had visited and supported her with personal care, breakfast and medication, she had been waiting for the nurse's visit. Dani asked Audrey about her ulcers and how she felt about her dressings; Audrey mentioned she was fine, but expressed concerns about the ulcers not healing. Dani reassured Audrey, explained leg ulcers to her and advised Audrey about some effective practice to promote the healing process.Dani asked Audrey ‘How best can I help you, and how do you want your care to be delivered?’. Audrey responded, ‘You are the nurse, you know better’. Dani took ample time to explain to Audrey how she understands her own body better than any other person. Dani also reassured and encouraged Audrey that her opinions mattered, as this helped empower her, promoted her dignity and informed the nurse on how to care for her. Audrey then expressed to Dani that her other nurses, who are much younger than Dani, never ask her opinion regarding the ulcer management; hence, she was not willing to speak. Audrey mentioned that those nurses came in to re-dress her ulcers and they spoke to her about the care plan, but she did not feel involved in decision-making about her care. Audrey then mentioned that she did not mean to create problems or report anyone. Dani reassured Audrey that there would be no trouble, so she should not be afraid to speak up. Audrey thought that having an honest communication about her needs and views could create problems for her or for the nurses if it seemed that she had reported them.Dani then reassured and encouraged Audrey that the situation will be addressed in a professional manner, and none of the other nurses would feel they had been reported; however, they would involve her in her care and decision-making, which is the expectation. Audrey was then comfortable, communicated in a suitable tone and maintained eye contact with Dani. She asked Dani if she could bandage her right leg first, as she tends to be in pain for a long time when the left one is dressed first. Dani gained consent from Audrey, explained the procedure and advised Audrey to stop her whenever she experienced pain. Dani also asked Audrey a bit more about her pain and her analgesia. Dani identified that Audrey's analgesia had not been reviewed for over 3 years. Dani explained to Audrey that she would be making a referral to her GP about this matter. Audrey was very pleased and indicated she was happy with how Dani had communicated with her; she felt she could trust her. Dani was also pleased, because she could provide the best care for Audrey.

Another important factor that can affect effective communication is the environmental factor. Norouzinia et al (2016) revealed that the hospital environment is a barrier to effective communication for patients. Additionally, Tay et al. (2011) indicated the possibility of unilateral communication due to the hierarchical structure of the hospital environment. Conversely, although nurses may feel quite comfortable in the hospital or inpatient setting, they might feel relatively intimidated when visiting a patient's home. Therefore, an awareness of the contextual discomfort and how it may affect communication is important and should be considered when planning for effective two-way communication between the nurse and patient during home visits. Although all these factors are important in communication, a full discussion of these is beyond the scope of this paper and should be the focus of another complete work.

In the model case described in Box 2 , the nurse acknowledged that she was privileged to be a guest in Audrey's home, and she tailored her strategy to gain Audrey's perspective. The nurse's aim was to get Audrey involved in her care decision-making since Audrey knows herself best. Additionally, Audrey's participation in the decision-making made it possible for her to receive her preferred care. This shows that effective communication is bidirectional, and both partners (nurse and patient) must work together to achieve their desired outcomes, in this case, the patient's satisfaction with care and the nurse's ability to provide the best care.

Effective communication in nursing is clearly a complex, multidimensional and multifactorial concept. Factors such as emotions, general appearance, personality trait, mood and level of education on communication may influence the practice and outcome of effective communication. However, effective communication is an ultimate determinant of success for a nurse. Effective communication was defined as a mutual agreement and satisfaction of care for both patients and nurses. It has been linked to precede the achievement of concordance in patients, and in nurses, it influences clinical reasoning and the nursing process. This aids in implementing compassionate person-centred care and, when successful, it promotes positive patient outcomes and satisfaction with nursing care. Thus, effective communication is an important concept to prioritise in nursing education and practice. For this reason, engaging nurses in communication skills and on-the-job training will empower them to communicate effectively with their patients. As endorsed by Rodgers's (1989) , the outcome of this analysis is not the endpoint of the concept but should direct the future exploration of effective communication. Therefore, a systematic study of effective communication between nurses and patients as well as a systematic review considering effective communication among nurses and patients with underlying communication difficulties, cognitive disabilities and intercultural perspectives can ultimately enhance nursing science.

- Effective communication is a key component of nursing practice

- Effective communication is intentional in nature and can be improved through direct actions taken by the nurse

- Communication is a complex phenomenon and is an essential element of building trust and comfort in nursing

- Concept analysis is the basic way of understanding complex concepts and developing different meanings and perceptions

CPD REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How might concept analysis be relevant in nursing studies or practice?

- What does effective communication mean to you?

- What are some challenges nurses face in communicating effectively?

- How can an interpersonal relationship between nurses and patients influence effective communication?

Communication Skills

- First Online: 24 January 2019

Cite this chapter

- Stephanie Fry 3 ,

- Kathryn Burrell 3 &

- Tamie Samyue 3

1721 Accesses

Communication is a vital component of the nursing role and is essential for the delivery of successful, quality healthcare. Good interpersonal communication increases the accuracy of information shared between nurse and patient and can amplify elements that are crucial in achieving positive health outcomes.

Effective and open communication is a key factor when liaising with a multidisciplinary team and can result in a collaborative and collegial approach to patient care.

Health literacy needs to be considered when communicating with patients. Knowledge of how to ensure patients understand basic health information will enable the delivery of information that is appropriate, effective and tailored to the individual’s needs.

In this chapter, the practical skills required to facilitate good communication will be reviewed and common barriers to communication explored, along with how to maintain effective communication via telephone and electronic mail. Communicating effectively within a professional capacity will also be discussed.

The importance of health literacy and the impact it has on communication with the patient will be highlighted and practical ways of providing information and education to patients explored.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adams RL, Appleton SL, Hill CL, Dodd M, Findlay C, Wilson DH (2009) Risks associated with low functional health literacy in an Australian population. Med J Aust 191(10):530–534

PubMed Google Scholar

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2014) Health literacy: taking action to improve safety and quality. ACSQHC, Sydney

Google Scholar

Balzer-Riley J (2017) Communication in nursing, 8th edn. Elsevier, Missouri

Burgoon JK, Guerrero LK, Floyd K (2016) Nonverbal communication. Routledge, New York

Book Google Scholar

Carlisle A, Jacobson KL, Di Francesco L, Parker R (2011) Practical strategies to improve communication with patients. Pharm Ther 36(9):576–589

Centre for Health Care Strategies (2013) Society of Hospital Medicine: how is health literacy identified? http://www.chcs.org/media/How_is_Low_Health_Literacy_Identified.pdf . Cited 15 Mar 2017

Crohn’s and Colitis Australia (2016) Australian IBD standards: standards of healthcare for people with inflammatory bowel disease in Australia. https://www.crohnsandcolitis.com.au/ibdqoc/ibd-audit-report/ . Cited 27 Mar 2017

del Rio-Lanza AB, Suarez-Alvarez L, Suarez-Vazquez A, Vasquez-Casielles R (2016) Information provision and attentive listening as determinants of patient perceptions of shared decision-making around chronic illness. Springerplus 5:1386

Article Google Scholar

Iedema R, Manidis M (2013) Patient-clinician communication: an overview of relevant research and policy literatures. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and UTS Centre for Health Communication, Sydney

Kessels R (2003) Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med 96(5):219–222

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Knox R, Cooper M (2015) The therapeutic relationship in counselling and psychotherapy. Sage, New York

Miller WR, Rollnick SR (2013) Motivational interviewing: helping people change, 3rd edn. The Guildford Press, New York

O’Connor M, Bager P, Duncan J, Gaarenstroom J, Younge L, Détré P et al (2013) N-ECCO consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 7(9):744–764

O’Daniel M, Rosenstein A (2008) Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes RG (ed) Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, pp 271–284

Panes J, O’Connor M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Irving P, Petersson J, Colombel JF (2014) Improving quality of care in inflammatory bowel disease: what changes can be made today? J Crohn’s Colitis 8:919–929

Pulvirenti M, McMillan J, Lawn S (2011) Empowerment, patient centred care and self management. Health Expect 17:303–310

Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC (2008) Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behaviour. The Guildford Press, New York

Watts S, Stevenson C, Adams M (2016) Improving health literacy in patients with diabetes. Nursing 47(1):24–31

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Gastroenterology, St Vincent’s Hospital (Melbourne), Fitzroy, VIC, Australia

Stephanie Fry, Kathryn Burrell & Tamie Samyue

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stephanie Fry .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

DRK Kliniken Berlin Westend, Department of Gastroenterology, Berlin, Germany

Andreas Sturm

Gastroenterology Level 5, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

Lydia White

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Fry, S., Burrell, K., Samyue, T. (2019). Communication Skills. In: Sturm, A., White, L. (eds) Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nursing Manual. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75022-4_37

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75022-4_37

Published : 24 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-75021-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-75022-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Communication skills in nursing: A phenomenologically-based communication training approach

Affiliations.

- 1 Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Department of Health Care Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Department of Health Care Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Department of Health Care Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Department of Health Care Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Department of Health Care Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 6 Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Department of Health Care Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 31487674

- DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.08.011

The aim of this article is to present a communication skills training curriculum for nursing students, based upon phenomenology. Research shows that nurses have difficulty prioritizing dialogue with patients, due to lack of time, organizational and cultural factors. Like other health care professionals, nurses may also have difficulties communicating with patients due to personal fears and shortcomings. The communication training curriculum based upon phenomenology aims at systematically training students to stay focused upon patients' and relatives' narratives, allowing them to reflect upon and better understand their current situation. This approach to communication is applicable in any clinical situation where it important to provide space for the patients' experiences. The philosophical principles guiding the training are presented here as well as the practical steps in the program. Finally, the approach is compared to other common communication methods used in nursing (motivational interviewing, caring conversations, empathy training). The authors hope that the article will highlight the nurses' role as dialogue partner as well as emphasize the importance of communication skills training in nursing education. This approach can be refined, tested and modified in future research and may serve as an inspirational model for creating a generic communicative competence for nurses. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Keywords: Communication training; Nurse-patient interaction; Phenomenology.

Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Clinical Competence*

- Communication*

- Education, Nursing

- Nurse-Patient Relations*

- Students, Nursing

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Comparison of barriers to effective nurse-patient communication in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards

- Hamed Bakhshi ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-7865-0149 1 ,

- Mohammad Javad Shariati ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-5518-698X 1 ,

- Mohammad Hasan Basirinezhad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3672-556X 2 &

- Hossein Ebrahimi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5731-7103 3

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 328 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

250 Accesses

Metrics details

Communication is a basic need of humans. Identifying factors that prevent effective nurse-patient communication allows for the better implementation of necessary measures to modify barriers. This study aims to compare the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication from the perspectives of nurses and patients in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in 2022. The participants included 200 nurses (by stratified sampling method) and 200 patients (by systematic random sampling) referred to two conveniently selected hospitals in Shahroud, Iran. The inclusion criteria for nurses were considered having at least a bachelor’s degree and a minimum literacy level for patients to complete the questionnaires. Data were collected by the demographic information form and questionnaire with 30 and 15 questions for nurses and patients, which contained similar questions to those for nurses, based on a 5-point Likert scale. Data were analysis using descriptive indices and inferential statistics (Linear regression) in SPSS software version 18.

The high workload of nursing, excessive expectations of patients, and the difficulty of nursing work were identified by nurses as the main communication barriers. From the patients’ viewpoints, the aggressiveness of nurses, the lack of facilities (welfare treatment), and the unsanitary conditions of their rooms were the main communication barriers. The regression model revealed that the mean score of barriers to communication among nurses would decrease to 0.48 for each unit of age increase. Additionally, the patient’s residence explained 2.3% of the nurses’ barriers to communication, meaning that native participants obtained a mean score of 2.83 units less than non-native nurses, and there was no statistically significant difference between the COVID and non-COVID wards.

In this study, the domain of job characteristics was identified by nurses as the major barrier, and patients emphasized factors that were in the domain of individual/social factors. There is a pressing need to pay attention to these barriers to eliminate them through necessary measures by nursing administrators.

Peer Review reports

First observed in Wuhan, China, the COVID-19 pandemic is an acute and very severe respiratory syndrome that the World Health Organization has raised as a health problem because of its high spread rate and consequences on an international scale. The number of COVID-19 patients is increasingly on the rise [ 1 , 2 ]. Illness and hospitalization are usually stressful and associated with bad experiences for patients and their family members [ 3 ].

According to Tabandeh Sadeghi et al. (2011) “Communication is a basic need of humans. Any interaction is an opportunity to achieve effective communication and participation in understanding the issue, which leads to the achievement of mutual goals by individuals.” [ 4 ]. The three important aspects of communication that are emphasized the most are the message’s sender, the receiver, and the environment. Communicating is an interaction between the sender and the receiver of the message, and the environment affects them [ 5 , 6 ]. In the context of a hospital, these three aspects of communication can be defined as nurse, patient, and hospital environment, and all three should be considered when examining the obstacles [ 7 ]. “According to Ali Fakhr Movahedi et al. (2012)” Communication is considered a central concept in nursing and an essential part of nursing work [ 8 ]. Patients perceive interaction with nurses as the basis of their treatment [ 9 ]. Nurse-patient communication is an interpersonal process that is created between these two groups during treatment. This process generally includes the start, work, and end stages. Effective communication is an essential aspect of patient care by nurses, and many nursing tasks cannot be performed without this activity [ 10 ]. Effective communication consists of explicit transmission and receipt of message content, in which information is consciously and unconsciously produced by a person and communicated to the recipient through verbal and non-verbal patterns [ 11 ]. The non-verbal aspect of communication plays an essential role and is more important than the verbal aspect of language in emergencies. The mandatory use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively influenced nurse-patient communication, notably because this tool significantly reduced the messages arising from non-verbal communication channels [ 12 ]. In this regard, Vitale et al. investigated wearing face masks as a communication barrier between nurses and patients. The results showed no differences in the patients’ opinions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; patients believed that the mask was not a communication barrier, while nurses thought that wearing masks was a communication barrier [ 12 ]. Unfavorable communication can hamper the patient’s recovery and may even permanently deprive the patient of health or life.

In comparison, good communication affects the patient’s recovery more than medication. In fact, nurses will succeed in their tasks when they can communicate well with their patients [ 13 ]. Effective communication can affect pain control, adherence to a treatment regimen, and the patient’s mental health and play an important role in reducing the patient’s anxiety and fear and faster recovery [ 14 ]. During good communication, patients can disclose and express sensitive and personal information. Consequently, nurses can also transfer necessary information, attitudes, or skills [ 4 ]. Identifying factors that prevent effective nurse-patient communication allows for the better implementation of measures required to adjust obstacles [ 15 ].

The first published reports of the deaths of coronavirus-infected doctors during caring for patients indicate that the virus transmission to healthcare workers in healthcare centers is a hazardous issue [ 16 , 17 ]. Under these stressful conditions, nurses must manage long shift hours and the fear of contagion and overcome communication difficulties through layers of personal protective equipment. These problems may disrupt communication with patients and cause less focus of health workers on the psychosocial well-being of patients [ 18 , 19 ]. Baillie states that the lack of time is a clear barrier to communication between emergency nurses and patients [ 20 ]. Meehan et al. also reported that nurses mentioned the lack of time, fatigue, and workload of personnel to be the factors preventing nurse-patient interaction. In the same research, patients cited the issue of gender as a factor preventing their interaction with nurses. However, male and female patients had difficulty communicating with male nurses [ 21 ].

Identifying factors that prevent effective nurse-patient communication makes it possible to elucidate the direction of necessary measures for the planners and executives of the health sector to eliminate or modify barriers. In particular, when these barriers are identified and expressed with a realistic approach, i.e., from nurses’ and patients’ perspectives [ 22 ]. Before this, no study compared barriers to nurse-patient communication in COVID and non-COVID wards. Therefore, this research aims to compare the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication from nurses’ and patients’ perspectives in COVID-19 and NON-COVID-19 wards. Hopefully, identifying these obstacles and planning to solve them as soon as possible will make us have nurses in the future who can communicate well with patients and improve service delivery.

Study design

This cross-sectional descriptive research was conducted on 200 nurses and 200 patients at hospitals affiliated with the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The participants included nurses and patients from different wards of two conveniently selected hospitals in Shahroud. To sample nurses by the stratified method, the sample size was first divided by the total number of nurses in the mentioned hospitals to obtain the sampling fraction. According to Mohammadi et al. study, standard deviations reported for all subscales for barrier’s to effective communication (individual/social factors = 6.22), job characteristics = 6.74, patient’s clinical conditions = 4.22), and environmental factors = 9.09) were utilized to estimate the sample size [ 23 ]. Estimation error was considered 0.15 of standard deviation values. The confidence levels and power were considered at 0.95 and 0.8 respectively with a 15% dropout probability. Also, another sample size was calculated similarly using the standard deviation reported in Norouzinia et al. study for patient’s questionnaire equal to 1.96 [ 24 ]. Finally, among the estimated values; the largest number (200) was considered as the sample size of the present study for nurses and patients.

Considering that the total number of nurses is around 700 and the sample size calculated by the statistics consultant is 200 nurses, our sampling fraction was calculated as \(\frac{2}{7}\) . Therefore, \(\frac{2}{7}\) personnel of each department were included in the study. The patients were sampled by a systematically random method using the hospital list, file number, and dates of admission and discharge. The inclusion criteria for nurses were a bachelor’s degree or higher and a minimum literacy level for patients to complete the questionnaire. Moreover, the questionnaire contained questions about the nurses’ work experience or no experience in COVID-19 wards. The duration of working in COVID-19 wards was included in the questionnaire questions, and the duration was considered in the analysis. Data were collected using a questionnaire provided to the nurses through daily visits to various wards of the mentioned hospitals, including emergency, surgery, special care, internal medicine, gastroenterology, cardiology, urology, orthopedics, ICU, CCU, and other wards. The questionnaire was also provided to the patients hospitalized in surgery, special care, internal medicine, gastroenterology, cardiology, urology, ICU, and CCU wards, among others. Due to the reduced coronavirus spread during that period, the information on COVID-19 patients was accessed using hospital information by obtaining permission, and the questionnaire was completed through phone calls.

Measurements

Demographic information form.

It contained questions about information related to age, gender, marital status, language, and residence.

Communication barrier questionnaire

The barriers to effective nurse-patient communication were investigated using the same questionnaire designed by Anoosheh et al. This questionnaire contains 30 items for nurses and aims to evaluate nurses’ views about the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. The response of this questionnaire is in the Likert range (completely false = 1, false = 2, I have no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and completely agree = 5). The nurses’ questionnaire contains four dimensions, and the question numbers of each dimension include individual/social factors (1–8), occupational characteristics (9–17), patient’s clinical conditions (18–21), and environmental factors (22–30). The domain of individual/social factors includes questions such as the gender difference between the patient and the nurse, age difference, aggressiveness of nurses, etc. The domain of job characteristics includes questions about the high workload of nursing, the difficulty of nursing work, the low salaries of nurses, etc. The domain of the patient’s clinical condition also includes questions such as the severity of the disease, the presence of the patient’s companion, etc. The domain of environmental factors: where communication occurs is important. The nurse and the patient should feel calm and safe in the treatment environment. This domain also includes questions such as the Lack of facilities (welfare - treatment) for patients, the unsanitary condition of the patient’s room, the High cost of treating patients, etc. A pilot study was carried out to assess the face validity among nurses. In addition, the content validity was assessed by estimation of content validity ratio and content validity index among nursing educators. The internal consistency for the present questionnaire assessed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to 0.96 [ 25 ].

The patient questionnaire contains 15 questions and aims to evaluate the patients’ views about the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. The response of this questionnaire is in the Likert range (completely false = 1, false = 2, I have no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and completely agree = 5). No separate dimension was considered for the patient questionnaire. The reliability based on internal consistency was reported using Cronbach’s alpha equal to 0.91 [ 25 ]. The total score of the questionnaire is obtained by summing up the total scores of all questions. The score of each dimension is obtained from the sum of scores for each question of that dimension. Higher scores in each dimension indicate the greater strength of that dimension as a barrier to effective nurse-patient communication and vice versa. After completing the communication barrier questionnaire, a separate question was asked from the patients and nurses about whether or not the face mask was a communication barrier. This question was scored with a Likert scale (completely false = 1, false = 2, I have no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and completely agree = 5). The score of this question was measured separately from the nurse-patient communication barrier questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

Initially, necessary permissions were obtained from the Vice Chancellor of Research and Technology and the Research Ethics Council (code of ethics: IR.SHMU.REC.1401.140) at the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. Necessary coordination was also made with the administrators of two conveniently selected hospitals in Shahroud. After explaining the purpose of the research and answering the questions of nurses and patients regarding the questionnaire and how to complete them, enough time was given to answer them.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential tests (Linear regression) in SPSS software version 18. All variables with a significance level of less than 0.2 are included in the final regression model. A significance level of 0.05 was considered. Considering that one of the purposes of this study is to determine the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication based on demographic information, three participants were excluded from the data analysis due to a lack of demographic information completion.

The average ages of nurses and patients were respectively 33.28 and 38.57 years, and most nurses (85.3%) and patients (61.5%) were females and males, respectively. Other demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1 .

In this study, the mean score obtained for each domain of the barriers to nurse-patient communication was determined from the nurses’ point of view. According to these results, the highest score with an average of 32.41 ± 6.75 related to the domain of job characteristics, and the lowest score with an average of 11.76 ± 3.17 related to the domain of Patient’s Clinical Conditions. Additional information is presented in Table 2 .

The excessive patients’ expectations in the domain of individual/social factors, the high workload of nursing in the domain of job characteristics, the severity of the disease in the domain of the patient’s clinical conditions, and no appreciation for nurses by authorities in the domain of environmental factors were the major communication barriers. The patient-nurse age difference from the domain of individual/social factors, the patient’s contact with multiple nurses with different attitudes from the domain of job characteristics, previous hospitalization history from the domain of the patient’s clinical conditions, and the high cost of patient treatment from the domain of environmental factors were the least important barriers to communication from the nurses’ viewpoints. From the patients’ views, the aggressiveness of nurses and the patient-nurse age difference were the major and the minor barriers to communication, respectively. Face masks were among the minor barriers to nurse-patient communication from the viewpoints of both groups (Table 3 ); this table is placed at the end of the article.

The relationship between nurses’ age and communication barriers was investigated using a regression model. This model was first run as a univariate type, and variables with a significance of < 0.2 were introduced into a multivariate model using the backward method. Finally, the model showed that the nurses’ age variable explained 3.8% of the score variance. In other words, the regression model revealed that the mean score of nurses would decrease to 0.486 for each year of age increase, and there is no statistically significant difference between the COVID and non-COVID wards (Table 4 ).

Additionally, the patient’s residence variable explained 2.3% of the score variance, meaning that native people obtained a mean score of 2.813 units less than non-native people, and there is no statistically significant difference between the COVID and non-COVID wards (Table 5 ).

The present study aimed to determine the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication from the viewpoints of nurses and patients in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards in hospitals affiliated with the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The results of this study showed that in the domains of barriers to effective communication, nurses reported the highest score in job characteristics and the lowest score in the patient’s clinical conditions. In a study on nursing students at Urmia Midwifery School of Nursing, Habibzadeh et al. (2017) reported the highest and the lowest mean scores for questions related to occupational characteristics and the patient’s clinical conditions [ 26 ], which corresponds to our results. Work congestion conditions increase the work pressure of nurses, leading to fatigue, a situation in which nurses lack enough time to discover the patient’s concerns [ 27 ]. Stress and pressure caused by time constraints often result in miscommunication and reduce the satisfaction of nurses and patients [ 28 ].

The results of this study showed that the high workload of nursing and excessive expectations of patients are mentioned as two major obstacles to effective communication with patients from the point of view of nurses. Anoushe et al. (2015) and Baraz Pordanjani et al. (2016) investigated barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. They reported that nurses identify their workload as a major barrier to effective patient communication [ 15 , 22 ]. However, Habibzadeh et al. (2017) claimed that nurses’ lack of information and skills in patient communication was identified as the main communication barrier [ 26 ]. A possible reason for this discrepancy might be that the current study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, concurrent with the increased workload of nurses compared to the pre-pandemic period.

The difficulty of nursing work, the psychophysical fatigue of nurses, the lack of comfort facilities for nurses, and no appreciation for nurses by administrators are in the next ranks of importance. Similarly, Anoushe et al. (2005) reported the difficulty of nursing work, the lack of comfort facilities for nurses, and psychophysical fatigue among the barriers with more emphasis by nurses [ 22 ]. The notable point is that nurses do not have the opportunity to establish effective communication with patients due to their workload. Furthermore, their work type is hard and tiring, and they do not receive proper benefits or appreciation. In such a situation, one cannot expect good nurse-patient communication, and the conditions affect patients’ moods. As expressed by the patients, this issue also negatively affects the quality of their relationships with patients [ 15 ].

The aggressiveness of nurses mentioned as the main obstacle to effective communication with patients from the patients’ point of view. Likewise, Baraz Pordanjani et al. (2009) found a statistically significant difference between the aggressiveness of nurses from the perspectives of nurses and patients [ 15 ].

Regarding the communication barriers from the patient’s perspective, the lack of facilities (welfare treatment) for them and the unsanitary condition of their rooms were among the factors more emphasized by patients than by the nurses. Interestingly, Baraz Pordanjani et al. observed that nurses believed more than patients that the lack of comfort facilities for patients and the unsanitary condition of their rooms would hinder effective communication [ 15 ]. This contradictory result can result from the difference in facilities and health/treatment conditions of the studied hospitals.

The viewpoints of both nurse and patient groups show that age and class differences do not negatively influence their relationships. Since nurses are responsible for initiating and maintaining communication with patients, it can be claimed that they perform their professional tasks, including communication establishment, regardless of the social class and age of patients, who also acknowledge this issue.

The face mask also obtained a low score from the viewpoints of patients and nurses. Vitale et al. investigated the use of face masks as a communication barrier between nurses and patients. The results indicated no difference in the patients’ opinions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; that is, patients did not consider the mask a communication barrier, which is consistent with the present study. However, nurses thought that using a mask would be a communication barrier [ 12 ].

The present results revealed a significant relationship between the age of nurses and the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication; as such, the total score of nurses decreased for each year of age increase; However, no statistically significant difference was observed in the comparison of COVID and non-COVID wards. In this regard, Gopichandran et al. (2021) aimed to determine communication barriers between doctors and patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. They claimed that communication barriers decreased with age [ 29 ]. Nurses gain more experience and skills with rising age. Enough experience is also a characteristic that patients consider necessary for nursing work [ 30 ]. “According to Aram Feizi et al. (2006)” Mark (2001) concluded that the experience of the nursing unit could create satisfaction in both nurses and patients [ 30 ]. The possible reason for obtaining different results could be that the COVID-19 vaccination process was carried out slowly in Iran. For this reason, the nurses, both in the COVID and non-COVID wards, considered all patients with unique viewpoints (all of the patients considered potential cases of COVID-19). For this reason, there was no statistical difference between the communication barriers of the COVID and non-COVID departments.

No statistically significant difference was observed between the scores of male and female nurses and the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. Unlike this result, Mohammadi et al. (2013) reported a significant difference between job characteristics, patients’ clinical conditions, environmental factors, and the gender of nurses [ 23 ]. The discrepant results might be caused by the heterogeneous distribution of participants in terms of gender, as 56% of the nurses were male in the study of Mohammadi et al. In comparison, less than 20% of the participants were male nurses in the present study.

The present results showed that the patients’ residence was significantly related to the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication, and native people obtained a lower mean score than non-native people: However, there was no any no significant difference between COVID and NON-COVID wards This result might be because nurses are more informed of the accents and dialects of native patients. Caring for patients speaking different languages and accents can lead to problems in the quantity and quality of nurse-patient communication. When patients and caregivers have different cultural values and languages, communication can cause the inability to exchange information [ 27 ]. Tilki and Okoughan presented evidence that differences in spoken language could hinder effective communication [ 31 ]. On the other hand, the results of the study by Vitale et al. showed that there was no difference between the patients before and during the covid-19 pandemic, which is consistent with the results of the present study [ 12 ].

Limitations

Among the limitations of this study, we can mention the low response rate by nurses and patients, which was completed with the continuous presence of the researcher. Since this research is conducted only in public medical centers affiliated to Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, the results may not be generalizable to centers affiliated with other universities of medical sciences in Iran and non-academic centers such as private medical centers. It is recommended that future research be conducted in larger settings.

This study demonstrated that nurses identified the domain of job characteristics as the most critical barrier among the four domains of barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. Patients more emphasized factors that were in the domain of individual/social factors. There is a pressing need to pay attention to these barriers to eliminate them through necessary measures by nursing officials. Hopefully, the elimination of these barriers in the future will lead to nurses who can communicate well with patients and improve service delivery.

Implications

This research helps to identify barriers to effective communication between nurses and patients. In the field of policy and management, the results of this research can help to plan for effective nurse-patient communication. In the field of education, according to the results of this article, necessary training should be given to nurses and patients regarding communication barriers to help improve communication. There will be a basis for further, more comprehensive research in the field of research. Hopefully, these results can help nursing officials and nurses remove communication barriers and improve service delivery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, Health Care Workers, and Health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2352–71.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Situation Report– 161. 2020.[cited 2020 June 29] https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200629-covid-19-sitrep-161.pdf?sfvrsn=74fde64e_2 .

Sheldon LK, Barrett R, Ellington L. Difficult communication in nursing. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38(2):141–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sadeghi T, Dehghan Nayyeri N, Karimi R. Nursing-patient relationship: a comparison between nurses and adolescents perceptions. Iran J Med Ethics History Med. 2011;4(3):69–78.

Google Scholar

Caris-Verhallen WM, De Gruijter IM, Kerkstra A, Bensing JM. Factors related to nurse communication with elderly people. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(5):1106–17.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kopp P. Better communication with older patients. Professional nurse (London, England). 2001;16(8):1296-9.

Aghamolaei T, Hasani L. Communication barriers among nurses and elderly patients. Hormozgan Med J. 2011;14(4):312–8.

Fakhr-Movahedi A, Negarandeh R, Salsali M. Exploring nurse-patient communication strategies. J Hayat. 2013;18(4):28–46.

Kettunen T, Poskiparta M, Gerlander M. Nurse-patient power relationship: preliminary evidence of patients’ power messages. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47(2):101–13.