Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

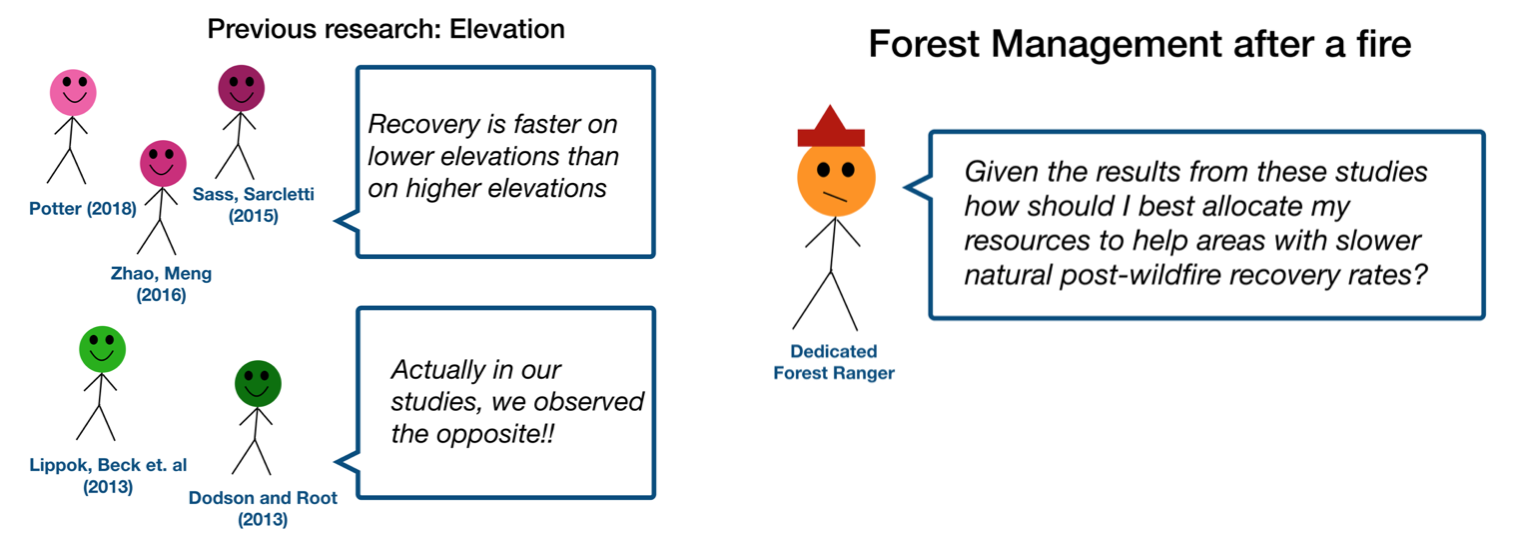

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Newly Launched - AI Presentation Maker

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

AI PPT Maker

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 10 Research Presentation Templates with Examples and Samples

Simran Shekhawat

Research organizes all your thoughts, suggestions, findings and innovations in one area that postulates to determining the future applicability. A crucial part of strategic planning is research. It aids organizations in goal setting, decision-making, and resource allocation. Research allows us to uncover and discover many segments of society by establishing facts and generating data that effectively determine future outcomes and progress.

Here's an ultimate guide to conduct market research! Click to know more!

Research primarily comprises gathering and analysing information about consumer behaviour, industry dynamics, economic conditions, and other elements that affect how markets and businesses behave in the context of understanding market trends. Understanding market trends requires market research, which is likely to be successful. Research can reveal prospective market dangers and difficulties, enabling organizations to create backup plans and decide on market entry or expansion with more excellent knowledge. By understanding market trends, businesses can create marketing and advertising efforts that resonate with their target audience.

Learn about product market research templates. Click here .

Additionally, it aids in determining the best customer-reach methods. Businesses can better satisfy market demands by customizing their products or services by studying consumer behaviours, preferences, and feedback. Assessing Market Size and Potential research can shed light on a market's size, potential for expansion, and competitive environment. Businesses aiming to expand or enter new markets need to know this information.

SlideTeam introduces you with their newly launch research templates that has been extensively built to enhance the quality of company’s research and development area by forging to bring answers related to every ‘how’ and ‘why’. The sole purpose of these is to inform, gather information and contributes towards the development and knowledge about the field of study. These templates are professionally design to disseminate knowledge to provide better judgements.

Template 1: Clinical Research Trial PowerPoint Template

Use this premium PPT template to captivate your audience. Download this well-created template to raise your presenting threshold. Establish your milestones with workflows designed to ease the overburdening of tasks. State clear-cut objectives to specify your aim and deliver a timeline. Use these 58-page PowerPoint slides to launch your product success and deliver a presentation that awakes the audience with your research performance and goals.

Click here!

Template 2: Company Stock Analysis and Equity Research Report Slide

Uncover impacts about the stock markets and analyze company-related specific and general equity design using this ready-made template. Understanding the technicality of maintenance and presentation of stocks and equity research, we at SlideTeam have designed an equity research PowerPoint slide to ease your presentation load. This presentation aims to analyze the target company's financial performance, ratios, and financial model to welcome investment in the company. Provide an extensive company summary, income statement, balance sheet, vertical and horizontal analysis, organization shareholding structure, SWOT analysis, and share price performance throughout history through this template.

Download Now!

Template 3: IT Services Research and Development Template

Showcase the power of your company's services, expertise achievement and future goals using this PPT template. This PPT slide provides you with a summary, key statistics, targets, and overview of your IT service Company. Allow this template to lay out values mission, categorize solutions, and enlist a range of services provided along with expenditure incurred on Research development. The deck also includes a business model canvas that depicts the company's historical development, global reach, management team, organizational structure, employee breakdown, and ownership structure.

Template 4: Research Proposal Steps PowerPoint Template

If you are looking to learn how to draft a research proposal, this slide is the ultimate fit for a newbie to comprehend about - 'what', 'where', and 'how' of research. Download this slide to learn about the format and structure of the research proposal. Use this template to illustrate the goal of the research proposal. Furthermore, our PPT sample file aids in instructing students on how to write a research proposal. Furthermore, you may quickly persuade the audience about the proposal's limitations, objectives, and research gap.

Template 5: Research Proposal for Thesis Template

Provide a clear idea and concise summary of your research with the help of this premium template. A well-written thesis statement frequently paves the way for discussion and debate. It can be the foundation for academic dialogue, enabling others to interact with and challenge your ideas—essential for developing knowledge across all disciplines. Your thesis statement will determine the depth of your study and conclusion while enabling you to attract your targeted audience.

Template 6: Market Research PowerPoint Template

To understand the trends and techniques of market structure, companies need to be aware of the trends and to enable that, and market research is one such profitable asset to invest in to allow numerous investments from companies across. Use this template to highlight the key drivers of growth that define the ultimate indicators of market trends. Use this PPT slide to solve marketing issues and make company decisions, incorporating polished business analysis PPT visuals. Get this template to connect business operations with your company's strategic goals.

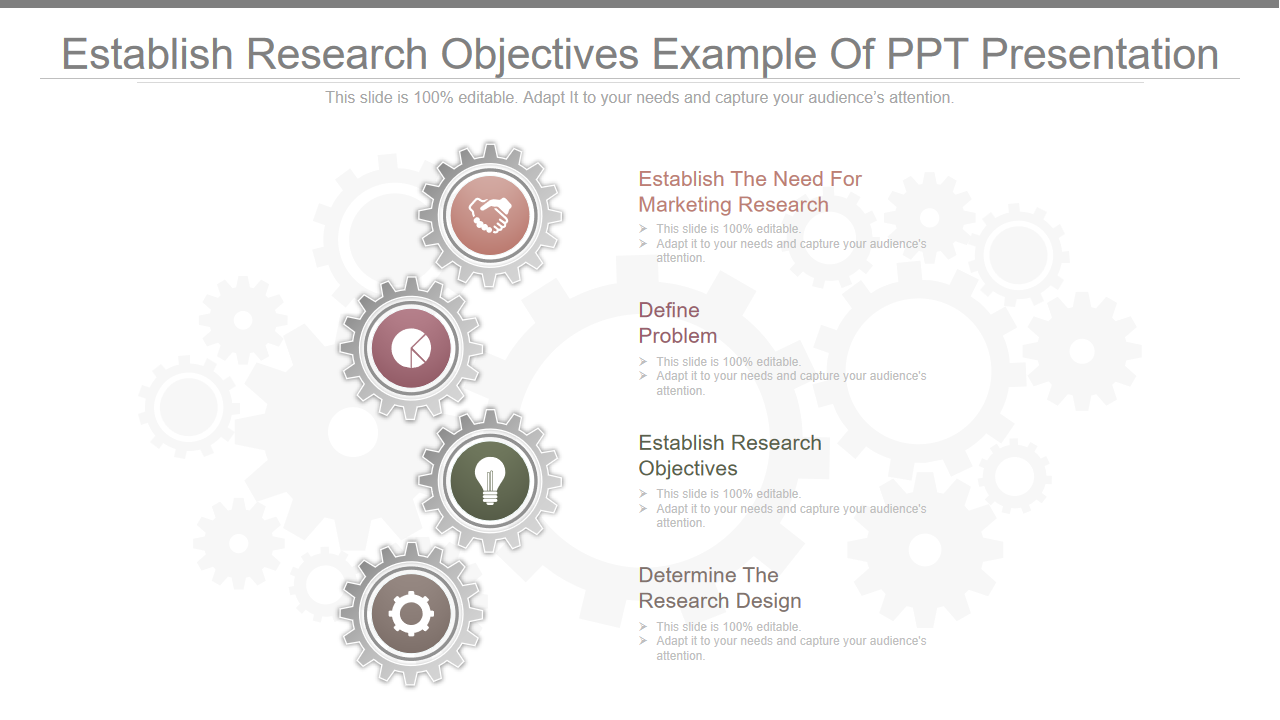

Template 7: Establish Research Objective Template

For an effective and meaningful research, clarity is essential. Deploy this template to facilitate that research objectives should specify the precise goals and targets of the study to assist in limiting its scope. To ensure the study's readability and comprehensibility, SlideTeam has crafted a flowchart template design to help you elucidate the study's objective, providing a basis for measuring and evaluating the success of well-defined research. Define and design your research with the help of this four-stage design pattern.

Template 8: A Company Research Venn Chart Presentation

Establish relationships between the sets and groups of data while comparing and contrasting the company's research analysis. This template is helpful as it helps to understand the abstract, objectives, limitations, methodologies, research gap, etc., of the research effectively while focusing on postulating future recommendations and suggestions.

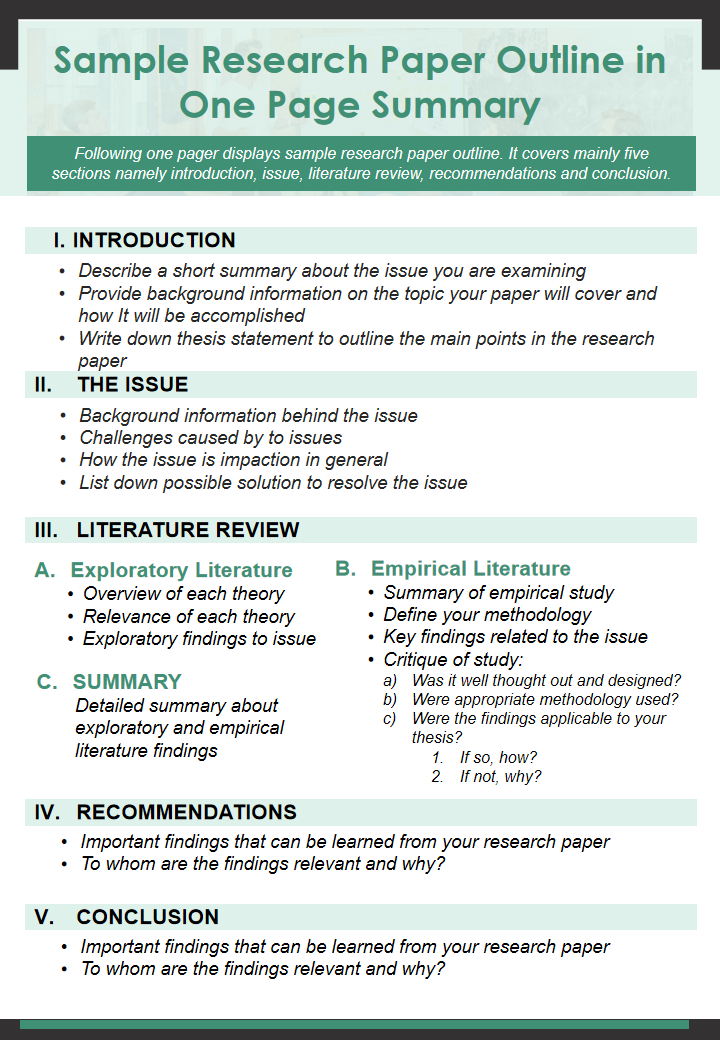

Template 9: Sample Research Paper Outline in a One-Pager Summary Presentation

How effortless it is to study a research paper without turning several pages? Grab this PPT template to research any topic and jot down your findings in a simple and concise format. Most importantly, a significant amount of their precious time can now be dedicated to critical tasks, aiding them in accelerating the research process. This incredibly well-curated one-pager template includes information about the introduction, problem, literature review, suggestions, and conclusions.

Template 10: Big Data Analytics Market Research Template

Deploy this template to introduce your company's extensive data analysis to understand the industry landscape, identify objectives, and make informed business decisions. Use this template slide to determine the current market size and growth rate. Consider the variables influencing this expansion, such as the rising volume of data produced and the demand for data-driven insights. Give information about the big data analysis market's prospects for the future. Over the coming few years, forecast growth trajectories, rising technologies, and market dynamics. Recognize the intended client base's demographics. Summarize your research and include suggestions for companies wishing to enter or grow in the big data analysis market.

PS: Provide an extensive statistical analysis for your research with this template. Check out now!

Refine your Research with SlideTeam.

SlideTeam introduces to its extensively built research templates that not only refines your search capability but also contributes towards the authenticity and development of your organization. It helps you to uncover veils of possibilities of growth while determining the bottlenecks and deriving appropriate solutions for future deliverables.

One of the attractive features about SlideTeam’s template are they are 100% customisable and editable as per the needs.

Download now!

PS: Provide an extensive statistical analysis for your research with this template . Check out now!

FAQs on Research Presentation

What is a research presentation.

Research Presentation is a visual representation of an individual or a team's observational findings or invocation in a particular subject.

What are the steps in research presentation?

To effectively convey your research findings to your audience, various phases are involved in creating a research presentation. Whether you're giving a presentation at a conference or a business meeting,

- Define your audience - Identify your audience's interests and level of knowledge. Make sure to adjust your presentation to fit their wants and needs.

- Outline What You Present - Create a clear structure with an introduction, three main ideas, and a conclusion. Choose the most essential points you want your audience to remember.

- Research and Data Collection - Gather and arrange the pertinent information, facts, and proof. Make sure your sources are reliable and current.

- Develop Visuals - To improve understanding, create visual aids like slides, charts, graphs, and photographs. Keep visuals straightforward, clutter-free, and with a distinct visual hierarchy.

- Get Your Audience Active - Take advantage of storytelling, anecdotes, or pertinent instances to draw in your audience. If appropriate, encourage audience participation and questions during the lecture.

- Present your argument - Start with a compelling introduction. Follow your outline while ensuring a logical and obvious flow.

- Keep an open line of communication, communicate clearly, and change your tone and pace. Improve your communication by making gestures and using body language. Respond to comments and questions as they come up or after the presentation.

- Recap and Draw a Conclusion - Summarize the core ideas and principal conclusions. Reiterate the importance of your study and its consequences.

How do you research a topic for a presentation?

To begin with, the idea of research presentation, choosing topics that align with your expertise and knowledge is the first and foremost. After understanding the topic, collect core factual and empirical data for proper understanding. After gauging information, it creates a place for every subtopic that must be introduced.

Related posts:

- Must-have Business Analyst Resume Templates with Examples and Samples

- Top 10 Data Processing Templates with Samples and Examples

- Must-have Data Mapping Document Templates with Samples and Examples

- Must-have Power BI Templates with Samples and Examples

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 10 Business Model Templates with Samples and Examples

Top 7 Introduction Templates with Samples and Examples

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

--> Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

--> Sales funnel results presentation layouts

--> 3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

--> Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

--> Future plan powerpoint template slide

--> Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

--> Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

--> Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

--> Agenda powerpoint slide show

--> Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

--> Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

--> Meet our team representing in circular format

👀 Turn any prompt into captivating visuals in seconds with our AI-powered design generator ✨ Try Piktochart AI!

7 Best Practices to a Standout Research Presentation

After months of rigorous analysis, interpretation, and synthesis, your research findings are ready to change the world (or at least your corner of it).

Now comes the next challenge: how do you translate your complex insights into a compelling research presentation that not only informs but captivates your audience?

Keep reading for tips and best practices to create a research presentation as confident as your findings.

Pro tip : Get your free Piktochart account before you scroll down. This way, you can immediately put our tips to practice as you read along. Alternatively, you can hop over to our AI presentation maker and find more examples of professional research presentation decks.

Keep your pen and paper handy so you can take notes!

What exactly happens during a research presentation?

When you present your research, you share what you’ve been working on and what you found out.

You start by explaining why your topic matters, then walk your audience through how you went about investigating it. Then, you share your results, often with visuals to make things clear. You wrap up by recapping your main points, talking about what your findings and their relevance, and pointing out any questions that still need to be answered.

In a nutshell, your research presentation is a way to get your work out there, get people talking, and maybe even gain new perspectives.

How long is a typical research presentation?

The ideal length of a research presentation depends on the specific context, audience, and purpose. Here’s a general guideline:

- Short and sweet (10-15 minutes): Perfect for giving your audience a taste of your research and sparking their interest.

- Standard fare (20-30 minutes): Enough time to dive deeper into your methods and findings, ideal for most academic settings.

- Deep dive (45-60+ minutes): A comprehensive look at your work. This is best for specialized audiences who want all the details of your research.

How about an AP research presentation? How long should it be?

The official time limit for an AP (Advanced Placement) Research presentation is 15 to 20 minutes. But here’s a quick tip: you won’t want to use every second of that. Effective presenters often aim for the lower end of this range because shorter yet well-organized presentations hold attention and leave room for questions.

Aim for an AP research presentation that’s around 12-15 minutes, leaving a few minutes for questions or discussion. This keeps things engaging and shows you respect your audience’s time. As you’ll see later below, some of the best winning presentations we’ve found online are just 3 minutes long!

Speaking of, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of designing successful, effective research presentations.

Beyond bullet points: How to create research presentations that stand out

First time presenters often fall into the trap of relying on endless bullet points and dry recitations of data. As tempting as this sounds to effectively organize your presentation, it can often look like you’ve just copied and pasted your paper into the slides, and you’ll end up reading off them verbatim.

Here are some best practices with accompanying research presentation examples to help you go beyond bullet points and leave a lasting impression the next time you present your research.

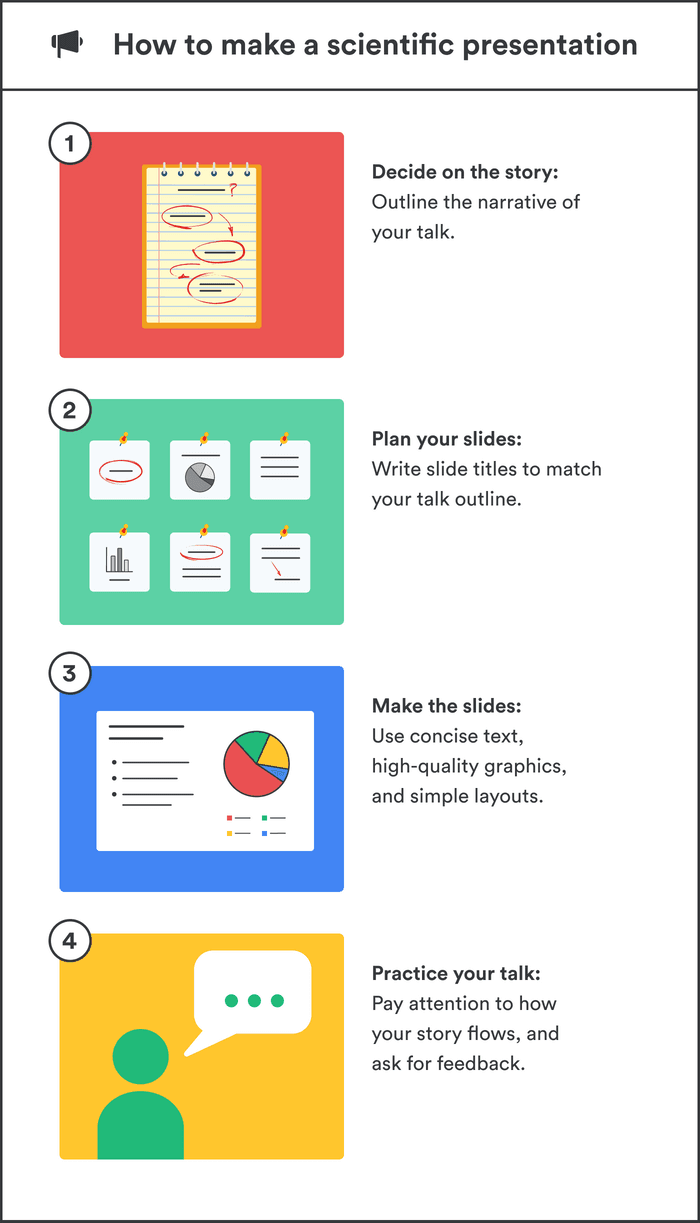

1. Develop a narrative for your research.

Let’s be honest, nobody wants to sit through a data dump disguised as a presentation. Instead, think of your research as a compelling story. Every good story has the following elements:

- Exposition: Set the scene for your research. What’s the problem you’re tackling? Why is your topic important? Use this section to create a compelling rationale that resonates with your audience’s interests or the broader implications of your work.

- Rising action (The challenge): Build tension and intrigue. What challenges did you face? What unexpected twists and turns did your research take? This is where you describe your research approach and the obstacles encountered, giving you a chance to inject some excitement into the research while demonstrating your problem-solving skills.

- Climax (Results): Reveal your findings! This is the moment your audience has been waiting for. This is the best time to use visuals to make your results memorable.

- Falling Action (Unpacking the results)): Help your audience make sense of your results. What are the broader implications? Are there potential applications, policy impacts, or do the results advance the theoretical understanding in your field?

- Resolution: Wrap it up with a satisfying conclusion. What are the next steps? What questions remain unanswered? End your presentation on a high note. Summarize your key takeaways, offer a call to action, or pose thought-provoking questions for future research. This leaves your audience wanting more.

A great example of a research presentation following a narrative arc is this 3-minute presentation by Shannon Lea Watkins of the University of California San Francisco. It won 1st place (Poster Presentation category) for APPAM’s (Association for Public Analysis and Management) 2017 Fall Research Conference.

The presentation skillfully introduces the research question, “Does initiating tobacco use with flavored products predict current smoking status? An examination by race, gender, and sexual identity,” and builds anticipation for the findings. The subsequent discussion of the research’s implications also effectively engages the audience and highlights its significance.

In just 3 minutes, the presenter communicated the core message using clear language and highlighted the key takeaways.

2. Use a font size that is legible from a distance.

Imagine your grandmother sitting in the back row. Would she be able to read your slides comfortably?

If not, it’s time to bump up your presentation slide’s font size. A good rule of thumb is to use a minimum font size of 24 points for body text and 36 points for headings.

In addition, white space is your friend. Don’t overcrowd your slides with too much text. Instead, use concise bullet points, phrases, or keywords to guide your narrative. This will keep your audience focused on your story and not squinting to read tiny texts.

Dr. Oliver Hauser’s presentation of his winning paper on “Minority Report: A Modern Perspective on Reducing Unethical Behavior in Organizations” is a good example of a presentation with legible text. The black text on a white background also creates excellent contrast which makes the text easily readable.

3. Choose your fonts carefully.

Now that you’ve taken care of your presentations’ font size, let’s talk about font types. So what’s the best font for research presentations?

When choosing the right font for your research presentation, consider the “personality” of different fonts and choose ones that align with your research’s tone and topic. For example, serif fonts are traditional and classic, while sans serif fonts are modern and clean.

It also helps to prioritize legibility over style, especially for body text. Finally, don’t be afraid to mix and match fonts for visual interest.

Here’s a pro tip from Stephanie Lee , Lead Designer at Piktochart:

“An important factor to consider when choosing fonts to use is to ensure it has good readability. Roboto is a good font to consider for presentations, it’s a reliable font that’s versatile in that it can be used for both headings and body copy. It’s a great option if you need your design to look professional & modern.”

If you want to get creative, consider exploring less common fonts that still maintain readability. Some popular choices include:

- Futura : A geometric sans serif font with a modern feel.

- Raleway : A versatile sans serif font that works well for both headings and body text.

- Libre Baskerville : A classic serif font with excellent readability.

- Poppins : A geometric sans serif font with a friendly and approachable vibe.

Recommended reading : 14 Fonts That Make Your PowerPoint Presentations Stand Out

How about font pairings for presentations?

Here are some general tips to help you with font pairings and create a professional and visually-appealing research presentation:

- Pair a serif font with a sans serif font: This classic combination offers a nice contrast between traditional and modern styles.

- Use a bold or decorative font for headings and a simple font for body text: This creates a clear hierarchy and helps your audience navigate your content.

- Limit your font choices to two or three: Using too many fonts can make your presentation look cluttered and unprofessional.

And here are some popular font pairings you can try when making your own presentation :

Classic and readable

- Heading: Georgia or Merriweather (serif)

- Body: Arial or Helvetica (sans-serif)

This combination is timeless and easy on the eyes. It works well for formal presentations and those with a lot of text.

Modern and clean

- Heading: Montserrat or Lato (sans-serif)

- Body: Open Sans or Roboto (sans-serif)

These fonts are sleek and contemporary. They are suitable for presentations with a minimalist design and those targeting a younger audience.

Creative and engaging

- Heading: Playfair Display or Lobster (serif)

- Body: Raleway or Oswald (sans-serif)

This pairing is visually interesting and can help capture attention. This combo is ideal for creative presentations and those focused on design or storytelling.

With Piktochart, finding the right font for your presentation is very straightforward. You’ve got many options right at your fingertips, and you can even upload your own if you want to make it more custom. This makes it easier to customize your research presentation slides and make them look sharp!

4. Choose a color palette that complements your presentation.

Your presentation slides’ color scheme sets the mood of your presentation and can even influence how your audience perceives your message. Here are some pointers to help you pick the righ t color palette :

Match it to your topic

The colors you choose should reflect the tone of your research. Calming blues and green palette combinations might work for a mental health presentation, while fiery reds and oranges could be better for discussing climate change.

Keep it simple

Don’t overwhelm your audience with a rainbow of colors. Following the rule of 3 is a safe approach; stick to a primary color, a secondary color, and maybe an accent color.

Consider color psychology

The color you choose for your presentation can evoke emotions. For example, blue often signifies trust while green can represent growth.

Here are some more examples to get you started:

- Scientific and academic: Use white, gray, black, with a pop of blue or green.

- Business and corporate: Use blues, grays, and a touch of gold.

- Creative and artistic: Go for vibrant colors like orange, yellow, or turquoise.

- Nonprofit and social Impact: Opt for earthy tones like brown or green, with a warm accent like orange.

If you’re still not sure if you can get your presentation’s color scheme right, Piktochart makes it easier for you with its Color Schemes feature. It allows you to apply a set of colors to your entire presentation slide in one click.

Piktochart offers two types of Color Schemes for your presentations:

- Suggested: These are pre-designed palettes curated by Piktochart’s designers and are available in most templates. Access them by clicking on the “Colors” option in the editor.

- Brand: Business plan users can create custom color schemes with up to six colors. These can be manually created or extracted from an image. To create a brand color scheme, go to “Brand” and click on “Create Brand Color Scheme”.

You can edit both types of color schemes by clicking the pencil icon.

This AP research presentation by Madeline Hart showcases the link between birth order and overall creativity.

Notice how Madeline incorporates vivid colors into her slides. Vivid colors like orange and yellow green are associated with creativity, energy, and enthusiasm. By using these colors, Madeline subtly reinforces her presentation’s theme and creates a visually stimulating experience for her audience.

In addition, while Madeline uses pops of color, her overall slide design likely remains clean and uncluttered. This allows her audience to focus on the content without being overwhelmed by excessive visuals or text.

5. Guide your audience with smooth, engaging transitions

Transitions should enhance, not overpower, your presentation. Smooth transitions between slides can make your presentation feel polished and professional. Avoid abrupt jumps or jarring effects. Use subtle fades, slides, or dissolves to maintain a sense of flow and continuity. It’s also worth noting that shorter transitions may feel energetic, while longer ones create a thoughtful atmosphere.

The good news is that Piktochart offers a range of slide transitions to improve the flow and visual appeal of your presentation. Here are some transition effects you can try:

- None: A simple, static transition with no animation.

- Default: Piktochart’s standard transition, usually a subtle fade or slide.

- Concave: A unique transition where the previous slide appears to bend inwards as the next slide takes its place.

- Fade: A gradual transition where the previous slide fades out as the next slide fades in.

- Linear: A simple, horizontal slide transition.

- Zoom: A dynamic transition where the next slide appears to zoom in from a distance.

Experiment with these transitions to find what best suits your research presentation. Learn more about these Piktochart transitions.

6. Remember the 5/5/5 Rule

The 5/5/5 Rule in presentation design is a simple yet powerful guideline designed to prevent your slides from becoming overwhelming walls of text. Here’s a breakdown of the rule:

- 5 lines of text: Aim to keep the text on each slide to a maximum of five lines. This helps prevent information overload and ensures that your key points are easily digestible.

- 5 words per line: Limit each line of text to approximately five words. This makes your slides easier to read and prevents your audience from getting lost in long sentences or complex ideas.

- 5 text-heavy slides: Avoid presenting more than five consecutive slides that are predominantly text-based. Break up the monotony with visuals, graphs, or interactive elements to maintain audience engagement.

Can you break the 5/5/5 Rule? Of course! It’s a guideline, not a law.

There may be times when you need to exceed these limits, such as when presenting complex data or detailed information. However, always strive for clarity and conciseness. If you must include a lot of text, consider using bullet points, breaking up the information into multiple slides, or providing handouts for your audience to reference later.

7. Test your presentation slides on different devices

Your meticulously crafted presentation might look flawless on your laptop screen, but that doesn’t guarantee it will translate well to other viewing environments like on a projector or smartphone.

Testing your slides on various devices is crucial because screen sizes, resolutions, and even operating systems can drastically alter how your presentation appears.

Here’s a quick checklist you can use:

- Your laptop/desktop

- Projector (if using)

- Smartphone (iOS and Android)

- Tablet (iPad or Android)

- Check in both standard and presentation modes.

- Zoom in and out to simulate different viewing distances.

- Test in different web browsers if you’re using online presentation software .

- Get feedback from others viewing your presentation on their devices.

Testing your research presentation on different devices is easy with Piktochart, thanks to its handy share URL feature. With just a few clicks, you can generate a unique link to your presentation and easily share it with colleagues, friends, or anyone else you’d like to get feedback from.

Here’s how it works:

- Create your presentation in Piktochart.

- Click the “Share” button.

- Select “Public on the Web” and click “Copy Link”

- Send the URL to your reviewers.

They can then access your presentation on their own devices and give valuable feedback on how it looks and functions across different screen sizes and platforms. It’s a simple, efficient way to ensure your presentation is polished and accessible to all audiences.

Make impactful research presentations slides with Piktochart

We’ve covered a lot of ground on how to turn your research into a presentation that’ll grab your audience’s attention and leave a lasting impact.

The takeaway here is it’s not just about the facts and figures—it’s about telling a story, being mindful of your fonts, smooth transitions, and keeping things concise. Testing your slides on different devices is a pro move too.

Don’t let your research findings go unnoticed—use Piktochart’s presentation maker to create impactful and thoughtful research presentations. Get your Piktochart free plan if you haven’t yet!

Other Posts

7 Sales Presentation Examples for Successful Pitches

How to Make a Presentation (Guide With Tips & Templates)

How to Nail Your Brand Presentation: Examples and Pro Tips

Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

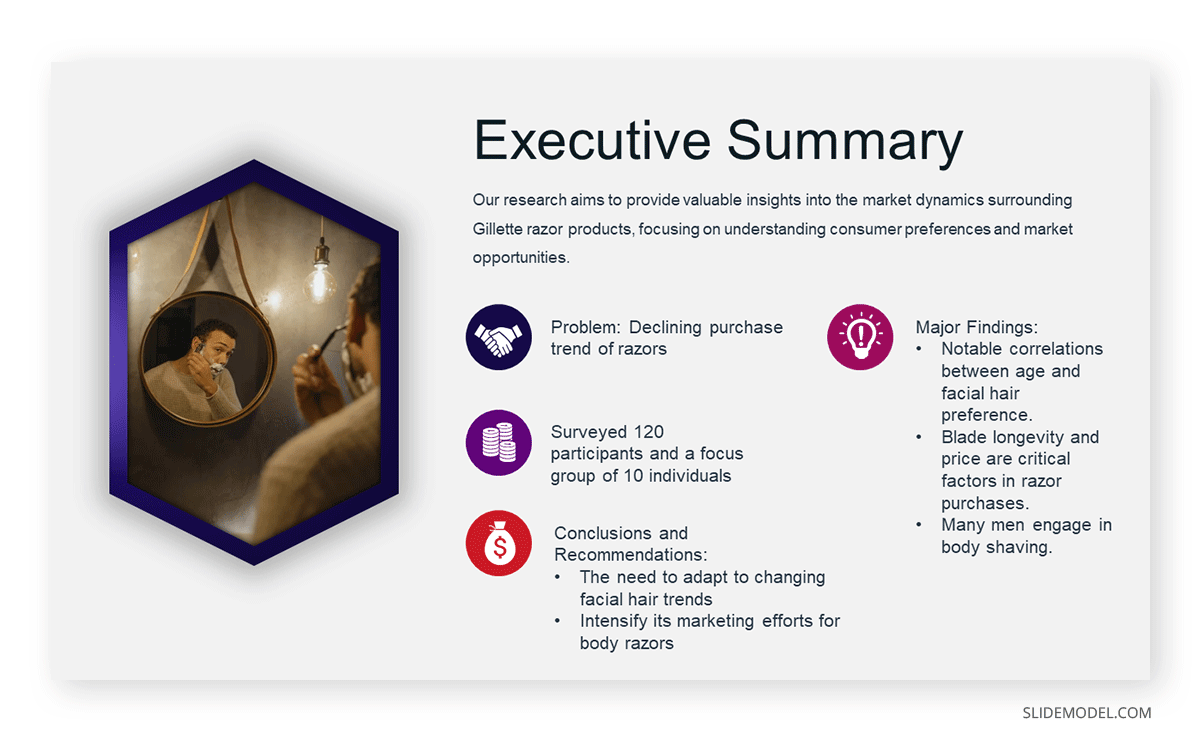

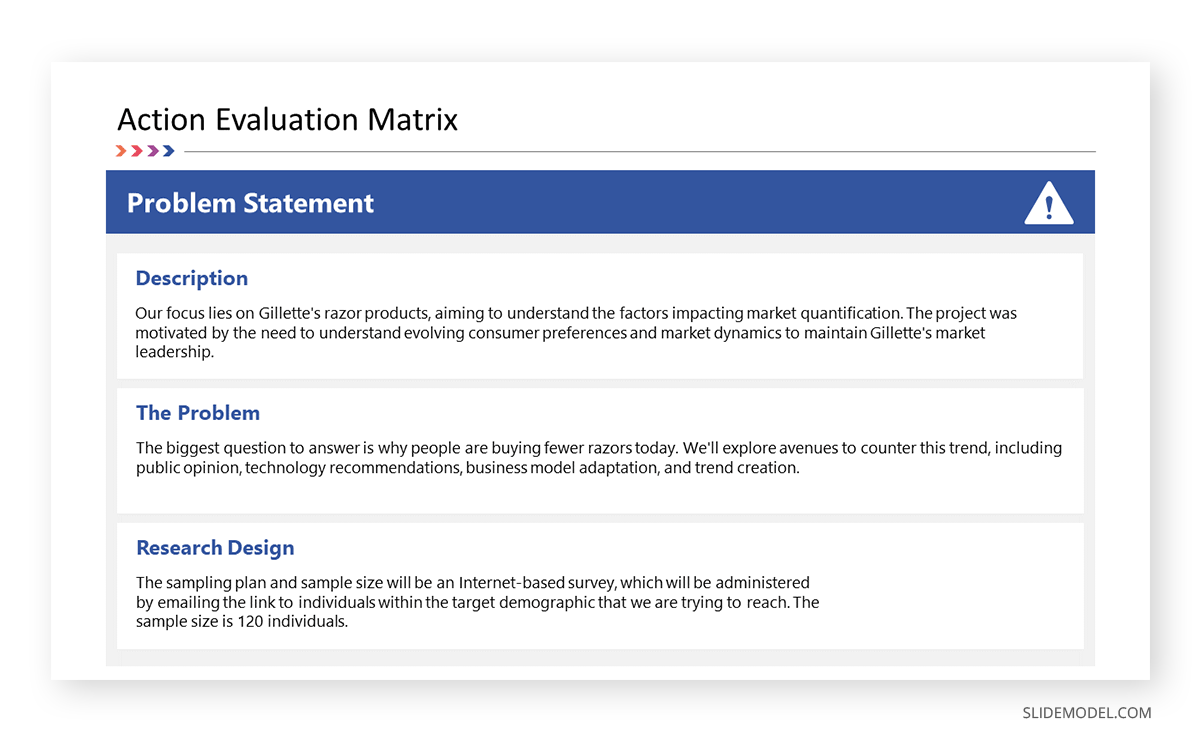

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

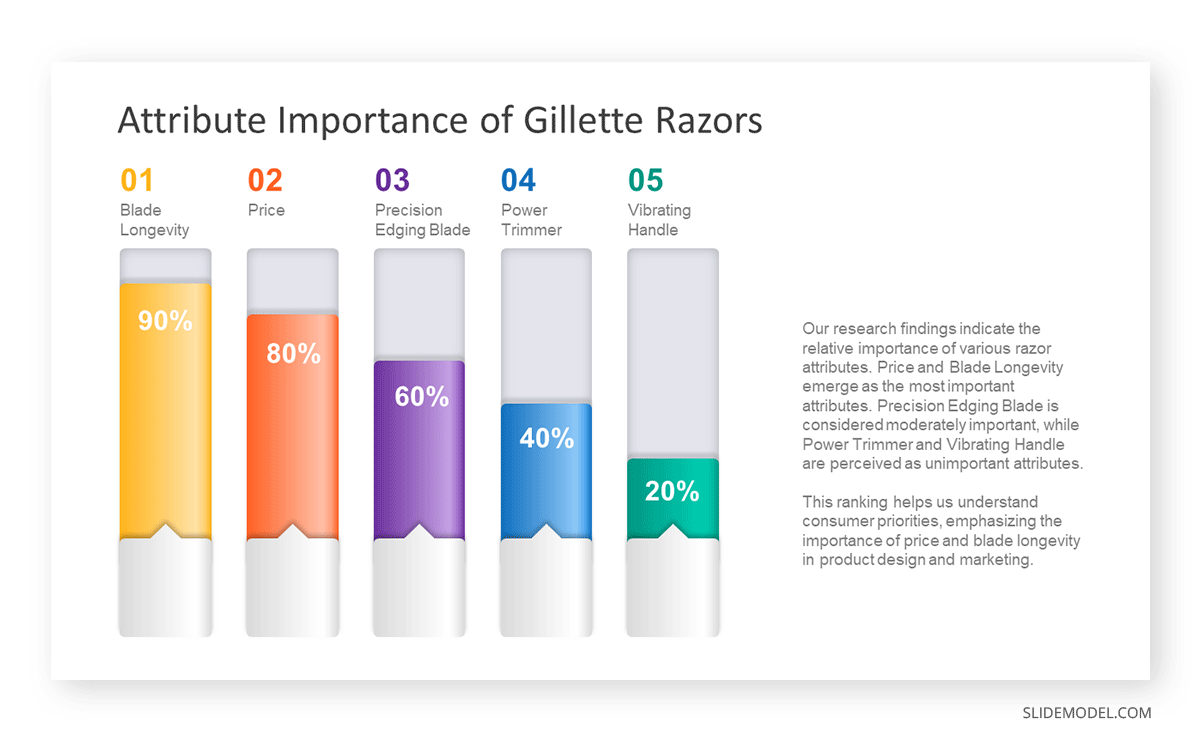

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

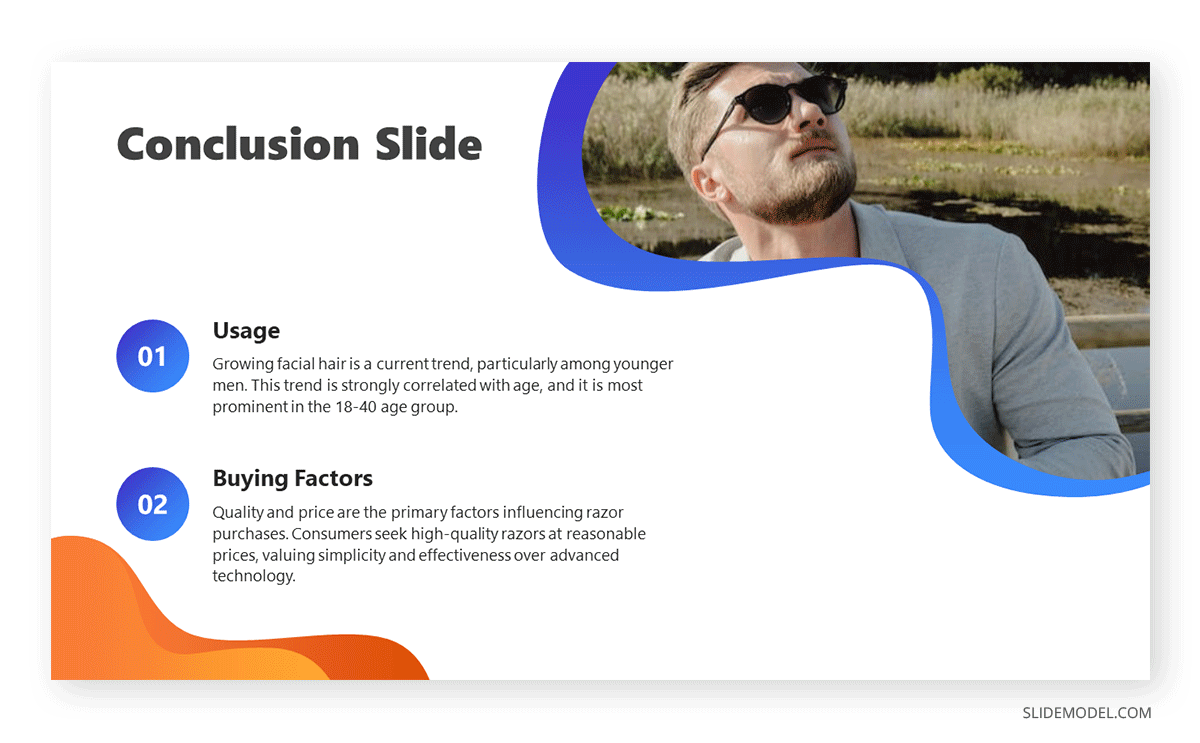

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

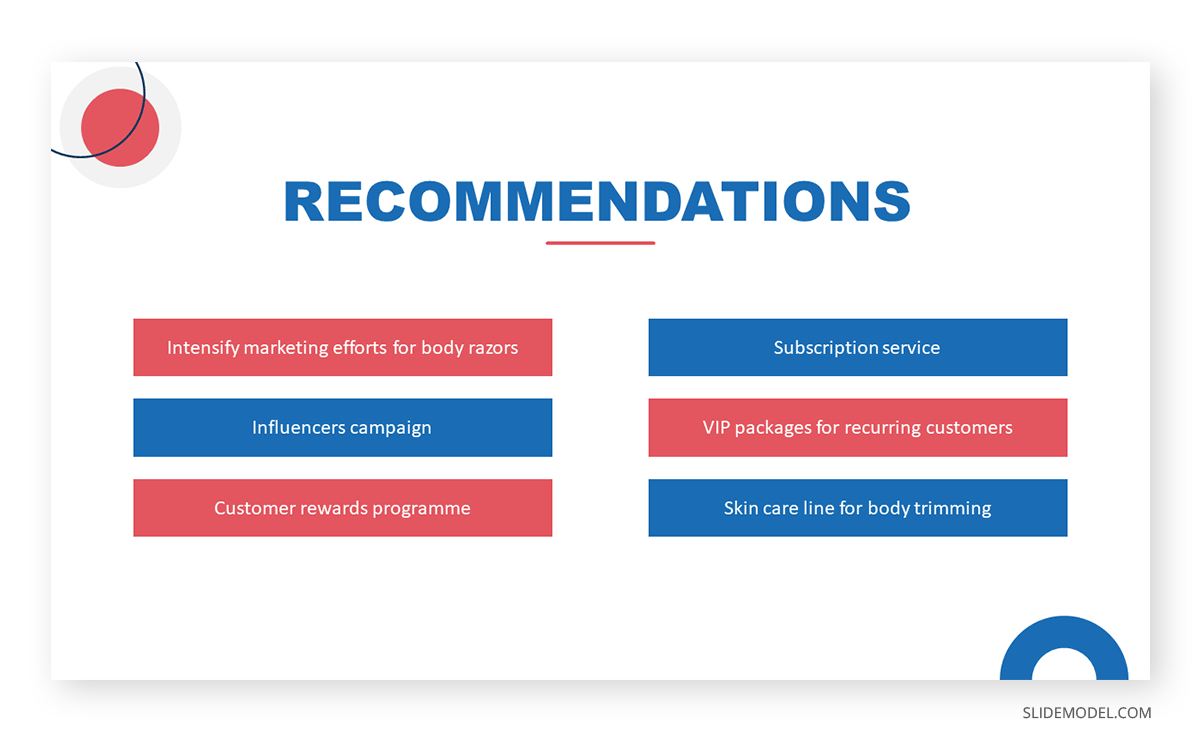

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation. Also, check our article about how to create handouts for a presentation .

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

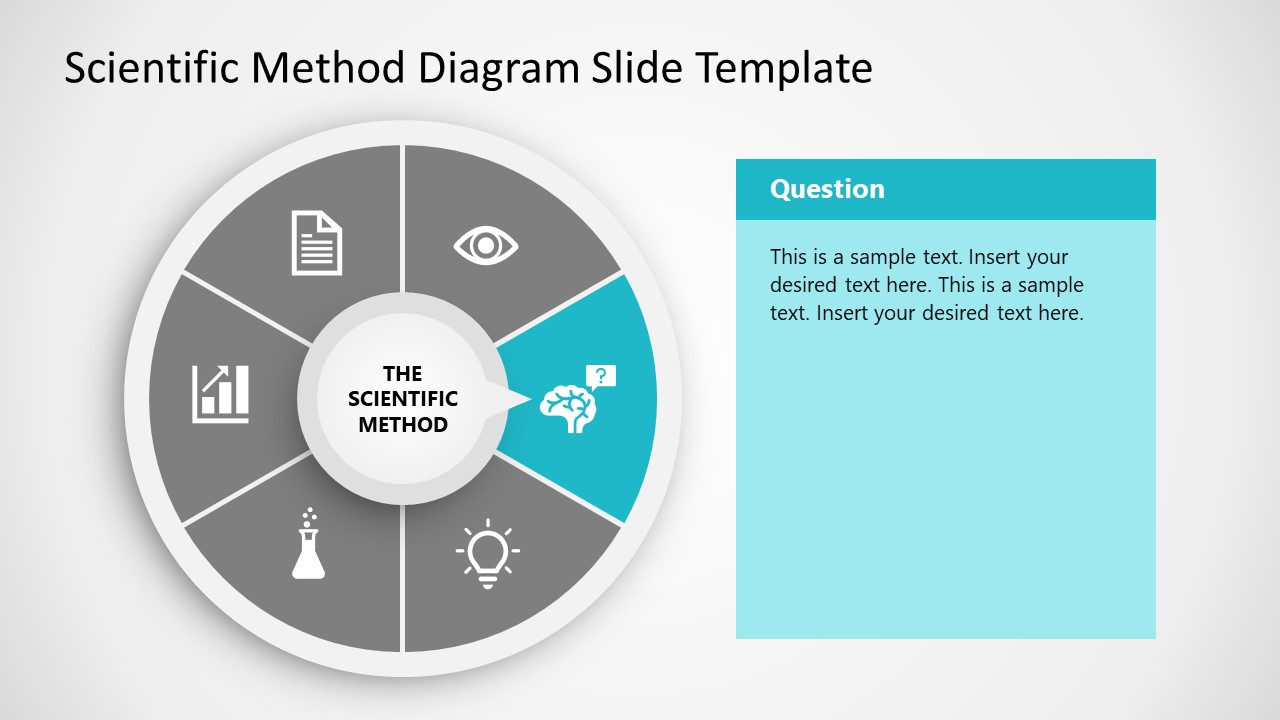

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

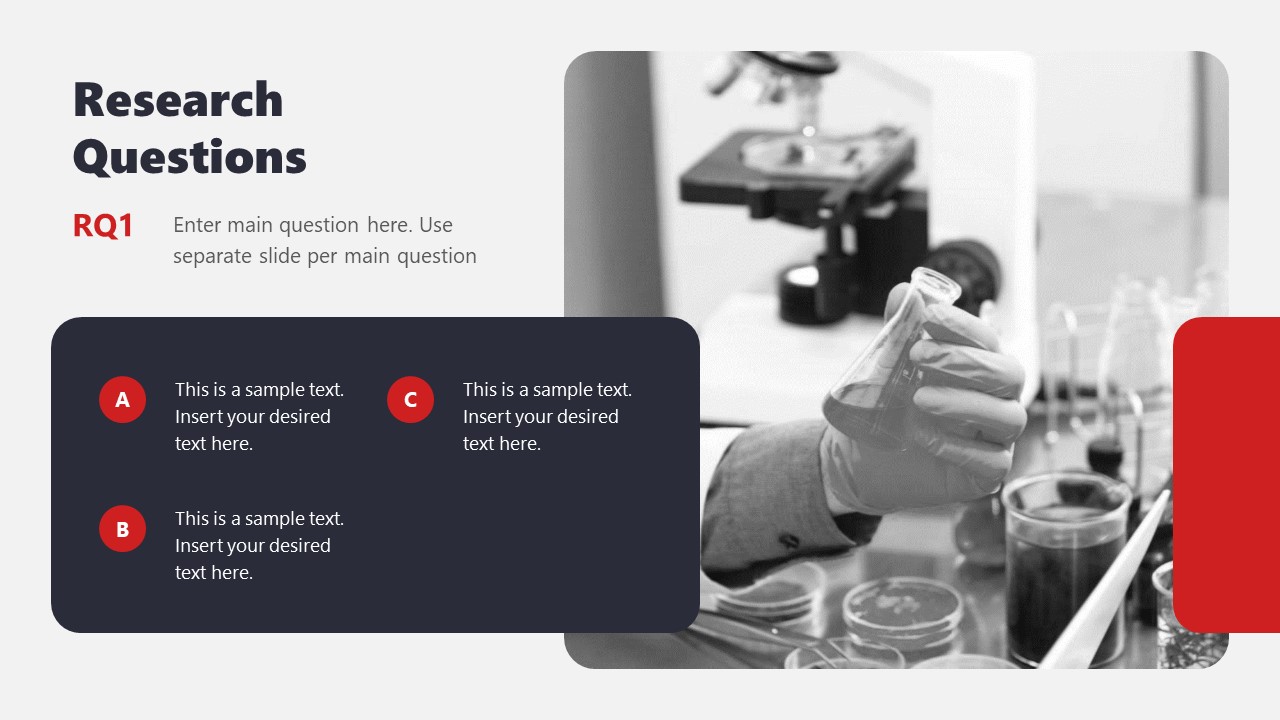

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Design • August 14th, 2024

Creating Custom Themes for PowerPoint and Google Slides

Do you want your slides to go beyond the average result from a template? If so, learn how to create custom themes for presentations with this guide.

Filed under Business • July 24th, 2024

How to Create a Demo Presentation

Discover the secrets behind successful demo presentations and what they should contain with this article. Recommended PPT templates included.

Filed under Presentation Ideas • July 17th, 2024

How to Convert a Text Document into a Presentation with AI

One of the biggest challenges for presenters is to summarize content from lengthy reports, academic papers, or any other kind of written media in an informative and concise way. Rather than losing countless hours going over and over the same text, we can speed up the process thanks to the virtues of artificial intelligence. In […]

Leave a Reply

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

12 Proven Tips to Make an Effective Research Presentation as an Invited Speaker

Guidance from an Experienced Mentor

The evolution of my presentation skills, what is there in this post for you, research presentation tip #1: start confidently, research presentation tip #2: eye to eye contact with the audience, research presentation tip #3: welcome your audience, research presentation tip #4: adjust your voice.

- Research Presentation Tip #5: Memorize your Opening Line

- Research Presentation Tip #6: Use the words “ 'Think for while', 'Imagine', 'Think of', 'Close Your Eyes' ”

Research Presentation Tip #7: Story Telling

Research presentation tip #8: facts and statistics.

- Research Presentation Tip #9: Power of "Pause"

Research Presentation Tip #10: Quote a Great Researcher

Research presentation tip #11: begin with a video, research presentation tip #12: avoid using filler words, side benefits of giving great research presentations, how should i dress for my invited talk at a research conference, can i share my conference presentation slides after my talk with the audience, shall i entertain questions in between my presentation as an invited speaker to a research conference, can you give some tips for a successful q&a session:.

- How to handle questions where I don't know the answers in my presentation?

Introduction

In this blog post, I’ll be sharing with you some invaluable tips for delivering an effective research presentation, drawn from my own journey through academia. These tips are not just theoretical; they’re the result of my own experiences and the guidance I received along the way.

When I first embarked on my PhD journey, the prospect of presenting my research to an audience filled me with a mixture of excitement and apprehension. Like many researchers, I was eager to share my findings and insights, but I lacked the confidence and experience to do so effectively.

It wasn’t until I had been immersed in my research for nearly a year, clarifying my domain, objectives, and problem statements, that I was presented with an opportunity to speak about my work. However, despite my preparation, I found myself struggling to convey my ideas with clarity and confidence.

Fortunately, I was not alone in this journey. At the event where I was scheduled to present my research, there was another presenter—an experienced professor—who took notice of my nerves and offered his guidance. He generously shared with me a set of tips that would not only improve my presentation that day but also become the foundation for my future presentations.

As I incorporated these tips into my presentations, I noticed a remarkable improvement in my ability to engage and inform my audience. Each tip—from starting confidently to utilizing storytelling and incorporating facts and statistics—contributed to a more polished and impactful presentation style.

As an invited speaker, delivering an effective research presentation is essential to engage and inform your audience. A well-crafted presentation can help you communicate your research findings, ideas, and insights in a clear, concise, and engaging manner.

However, many presenters face challenges when it comes to delivering a successful presentation. Some of these challenges include nervousness, lack of confidence, and difficulty connecting with the audience.

In this article, we will discuss tips to help you make an effective research presentation as an invited speaker. We will cover strategies to prepare for your presentation, ways to deliver your presentation with confidence and impact, and common mistakes to avoid.

By following these tips, you can improve your presentation skills and create a compelling and engaging talk that resonates with your audience.

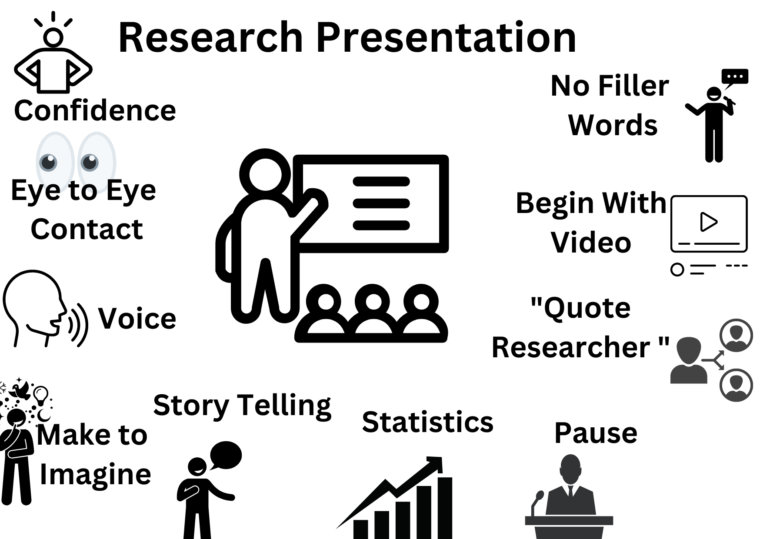

Tips to Make an Effective Research Presentation

- Tip 1: Start confidently

- Tip 2: Eye To Eye Contact With the Audience

- Tip 3: Welcome Your Audience

- Tip 4: Adjust your Voice

- Tip 5: Memorize your Opening Line

- Tip 6: Use the words “ ‘Think for while’, ‘Imagine’, ‘Think of’, ‘Close Your Eyes’ ”

- Tip 7: Story Telling

- Tip 8: Facts and Statistics

- Tip 9: Power of “Pause”

- Tip 10: Quote a Great Researcher

- Tip 11: Begin with a Video

- Tip 12: Avoid using Filler Words

Starting your presentation confidently is essential as it sets the tone for the rest of your presentation. It will help you grab your audience’s attention and make them more receptive to your message. Here are a few ways you can start confidently.

- Begin with a self-introduction: Introduce yourself to the audience and establish your credibility. Briefly mention your educational background, your professional experience, and any relevant achievements that make you an authority on the topic. For example, “Good morning everyone, my name is John and I’m a researcher at XYZ University. I have a Ph.D. in molecular biology, and my research has been published in several reputable journals.”

- Introduce the topic: Clearly state the purpose of your presentation and provide a brief overview of what you’ll be discussing. This helps the audience understand the context of your research and what they can expect from your presentation. For example, “Today, I’ll be presenting my research on the role of DNA repair mechanisms in cancer development. I’ll be discussing the current state of knowledge in this field, the methods we used to conduct our research and the novel insights we’ve gained from our findings.”

- Start with a strong opening statement: Once you’ve introduced yourself and the topic, start your presentation confidently with a statement that captures the audience’s attention and makes them curious to hear more. As mentioned earlier, you could use a strong opening statement, a powerful visual aid, or show enthusiasm for your research. For example:

- “Have you ever wondered how artificial intelligence can be used to predict user behaviour? Today, I’ll be sharing my research on the latest AI algorithms and their potential applications in the field of e-commerce.”

- “Imagine a world where cybersecurity threats no longer exist. My research is focused on developing advanced security measures that can protect your data from even the most sophisticated attacks.”

- “Think for a moment about the amount of data we generate every day. My research focuses on how we can use machine learning algorithms to extract meaningful insights from this vast amount of data, and ultimately drive innovation in industries ranging from healthcare to finance.”

By following these steps, you’ll be able to start your research presentation confidently, establish your credibility and expertise, and create interest in your topic.

Speaking confidently as an invited speaker can be a daunting task, but there are ways to prepare and feel more confident. One such way is through practising yoga. Yoga is a great tool for reducing stress and anxiety, which can be major barriers to confident public speaking.

By practising yoga, you can learn to control your breathing, calm your mind, and increase your focus and concentration. All of these skills can help you feel more centred and confident when it’s time to give your presentation.

If you’re interested in learning more about the benefits of yoga, check out our blog post on the subject YOGA: The Ultimate Productivity Hack for Ph.D. Research Scholars and Researchers .

If you’re ready to dive deeper and start your own yoga practice, be sure to download my e-book on :

Unlock Your Research Potential Through Yoga: A Research Scholar’s Companion

A large number of audiences in the presentation hall make you feel jittery and lose your confidence in no time. This happens because you are seeing many of the audience for the first time and you don’t know their background and their knowledge of the subject in which you are presenting.

The best way to overcome this fear is to go and attack the fear itself. That is come at least 10-15 minutes early to the conference room and start interacting with the people over there. This short span of connectivity with a few of the audience will release your tension.

When you occupy the stage for presenting, the first thing you need to do is gaze around the room, establish one-to-one eye contact, and give a confident smile to your audience whom you had just met before the start of the presentation.

Just gazing around the presentation hall will make you feel connected to everyone in the hall. Internally within your mind choose one of the audience and turn towards him/her make eye contact and deliver a few sentences, then proceed to the next audience and repeat the same set of steps.

This will make everyone in the room feel that you are talking directly to them. Make the audience feel that you are engaging with them personally for this topic, which makes them invest fully in your topic.

The third tip for making an effective research presentation is to welcome your audience. This means taking a few minutes to greet your audience, introduce yourself, and set the tone for your presentation. Here are a few ways you can welcome your audience:

- Greet your audience: Start by greeting your audience with a smile and a warm welcome. This will help you establish a connection with your audience and put them at ease.

- Introduce yourself: Introduce yourself to the audience and give a brief background on your expertise and how it relates to your presentation. This will help your audience understand your qualifications and why you’re the right person to be delivering the presentation.

- Explain the purpose of your presentation: Explain to your audience why you’re presenting your research and what they can expect to learn from your presentation. This will help your audience understand the context of your research and what they can expect from your presentation.

- Set the tone: Set the tone for your presentation by giving a brief overview of your presentation structure and what your audience can expect throughout your presentation. This will help your audience understand what to expect and keep them engaged.

Here are a few examples of how you can welcome your audience:

- If you’re presenting to a group of industry professionals, welcome them by acknowledging their expertise and experience. This will show that you value their knowledge and experience.

- If you’re presenting to a group of students or academics, welcome them by acknowledging their interest in your research area. This will help you establish a connection with your audience and show that you’re excited to share your research with them.

- If you’re presenting to a mixed audience, welcome them by acknowledging their diversity and the different perspectives they bring to the presentation. This will help you set an inclusive tone and show that you’re open to different viewpoints.

Overall, welcoming your audience is an important aspect of delivering an effective research presentation. It helps you establish a connection with your audience, set the tone for your presentation, and keep your audience engaged throughout your presentation.

In my earlier days of presentations, I just used to go on stage and start my presentations without greeting anyone. Later I learned stage etiquette with the help of my fellow research scholars and underwent professional etiquette courses .

The fourth tip for making an effective research presentation is to adjust your voice. This means using your voice effectively to convey your message and engage your audience. Here are a few ways you can adjust your voice during your research presentation:

- Speak clearly: Speak clearly and enunciate your words so that your audience can understand what you’re saying. Avoid speaking too fast or mumbling, which can make it difficult for your audience to follow your presentation.

- Use a varied pace: Use a varied pace to keep your audience engaged. Speak slowly and clearly when you’re making important points, and speed up when you’re discussing less important points. This will help you maintain your audience’s attention throughout your presentation.

- Use a varied pitch: Use a varied pitch to convey emotion and emphasize important points. Lower your pitch when you’re discussing serious or important topics, and raise your pitch when you’re excited or enthusiastic.

- Use pauses: Use pauses to emphasize important points and give your audience time to reflect on what you’re saying. Pausing also helps to break up your presentation and make it easier for your audience to follow.

Here are a few examples of how you can adjust your voice during your research presentation:

- If you’re discussing a complex or technical topic, speak slowly and clearly so that your audience can understand what you’re saying. Use pauses to emphasize important points and give your audience time to reflect on what you’re saying.

- If you’re discussing an exciting or enthusiastic topic, raise your pitch and use a varied pace to convey your excitement to your audience. This will help you engage your audience and keep them interested in your presentation.

- If you’re discussing a serious or emotional topic, lower your pitch and use a slower pace to convey the gravity of the situation. Use pauses to emphasize important points and give your audience time to process what you’re saying.

Overall, adjusting your voice is an important aspect of delivering an effective research presentation. It helps you convey your message clearly, engage your audience, and keep their attention throughout your presentation.

Many researchers are less talkative and speak with a very low voice and this makes their concepts unheard by other researchers. To overcome this drawback, they go for vocal coaching to improve their voice modulation.

Research Presentation Tip #5: Memorize your Opening Line

The fifth tip for making an effective research presentation is to memorize your opening line. This means having a powerful and memorable opening line that will grab your audience’s attention and set the tone for your presentation. Here are a few ways you can create a memorable opening line:

- Use a quote or statistic: Start your presentation with a powerful quote or statistic that relates to your research. This will grab your audience’s attention and show them why your research is important.

- Use a story or anecdote: Use a personal story or anecdote to illustrate the importance of your research. This will help you connect with your audience on an emotional level and show them why your research is relevant to their lives.

- Ask a question: Ask your audience a thought-provoking question that relates to your research. This will help you engage your audience and get them thinking about your topic.

Once you’ve created a memorable opening line, it’s important to memorize it so that you can deliver it confidently and without hesitation. Here are a few examples of powerful opening lines:

- “In the United States, someone dies of a drug overdose every seven minutes. Today, I want to talk to you about the opioid epidemic and what we can do to prevent it.”

- “When I was a child, my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Today, I want to share with you the latest research on Alzheimer’s and what we can do to slow its progression.”

- “Have you ever wondered why some people are more resilient than others? Today, I want to talk to you about the science of resilience and how we can use it to overcome adversity.”

Overall, memorizing your opening line is an important aspect of delivering an effective research presentation. It helps you grab your audience’s attention, set the tone for your presentation, and establish your credibility as a speaker.

Remembering the concepts at the right time and in the right sequence is critical for every researcher. Few of my research scholars face the problem of forgetting everything once they reach the stage for presentation. To overcome this difficulty I gift them with one of my favourite books on improving memory power: “Limitless by Jim Quick” . This book has changed many lives. You can also try.

Research Presentation Tip #6: Use the words “ ‘Think for while’, ‘Imagine’, ‘Think of’, ‘Close Your Eyes’ ”

The sixth tip for making an effective research presentation is to use specific phrases that encourage your audience to think, imagine, and engage with your presentation. Here are a few examples of phrases you can use to encourage your audience to engage with your presentation:

- “Think for a moment about…” This phrase encourages your audience to reflect on a particular point or idea that you’ve just discussed. For example, “Think for a moment about the impact that climate change is having on our planet.”

- “Imagine that…” This phrase encourages your audience to visualize a particular scenario or idea. For example, “Imagine that you’re living in a world without access to clean water. How would your daily life be affected?”

- “Think of a time when…” This phrase encourages your audience to reflect on their own experiences and relate them to your presentation. For example, “Think of a time when you felt overwhelmed at work. How did you manage that stress?”

- “Close your eyes and picture…” This phrase encourages your audience to use their imagination to visualize a particular scenario or idea. For example, “Close your eyes and picture a world without poverty. What would that look like?”

By using these phrases, you can encourage your audience to actively engage with your presentation and think more deeply about your research. Here are a few examples of how you might incorporate these phrases into your presentation:

- “Think for a moment about the impact that our use of plastics is having on our environment. Each year, millions of tons of plastic end up in our oceans, harming marine life and polluting our planet.”

- “Imagine that you’re a scientist working to develop a cure for a deadly disease. What kind of research would you conduct, and what challenges might you face?”

- “Think of a time when you had to overcome a significant challenge. How did you persevere, and what lessons did you learn from that experience?”

- “Close your eyes and picture a world where renewable energy is our primary source of power. What benefits would this have for our planet, and how can we work together to make this a reality?”

Overall, using phrases that encourage your audience to think and engage with your presentation is an effective way to make your research presentation more impactful and memorable.

The seventh tip for making an effective research presentation is to incorporate storytelling into your presentation. Storytelling is a powerful way to connect with your audience, illustrate your points, and make your research more engaging and memorable.

People love stories, but your story has to be relevant to your research. You can craft a story about an experience you had and tell how you could able to define your research problem based on the experience you had. This makes your presentation both interesting and incorporates information about the work you are carrying out.

Storytelling or sharing your own experience is the best way to connect with your audience. Many researchers use this technique and it remains one of the most critical pieces to becoming an effective presenter.

Here are a few examples of how you can incorporate storytelling into your presentation:

- Personal stories: Use a personal story to illustrate the importance of your research. For example, if you’re researching a new cancer treatment, you might share a story about a friend or family member who has been affected by cancer. This personal connection can help your audience relate to your research on a more emotional level.

- Case studies: Use a case study to illustrate how your research has been applied in the real world. For example, if you’re researching the impact of a new educational program, you might share a case study about a school that has implemented the program and seen positive results.

- Historical examples: Use a historical example to illustrate the significance of your research. For example, if you’re researching the impact of climate change, you might share a story about the Dust Bowl of the 1930s to illustrate the devastating effects of drought and soil erosion.

- Analogies: Use an analogy to explain complex concepts or ideas. For example, if you’re researching the workings of the brain, you might use the analogy of a computer to help your audience understand how neurons communicate with each other.

By incorporating storytelling into your presentation, you can help your audience connect with your research on a more personal level and make your presentation more memorable. Here are a few examples of how you might incorporate storytelling into your presentation:

- “When my mother was diagnosed with cancer, I felt helpless and afraid. But thanks to the groundbreaking research that is being done in this field, we now have more treatment options than ever before. Today, I want to share with you the latest research on cancer treatments and what we can do to support those who are fighting this disease.”

- “Imagine for a moment that you’re a small business owner trying to grow your online presence. You’ve heard that search engine optimization (SEO) is important for driving traffic to your website, but you’re not sure where to start. That’s where my research comes in. By analyzing millions of search queries, I’ve identified the key factors that search engines use to rank websites. Using this information, I’ve developed a new algorithm that can help businesses like yours optimize their websites for better search engine rankings. Imagine being able to reach more customers and grow your business, all thanks to this new algorithm. That’s the power of my research.”

In these examples, the speaker is using storytelling to help the audience understand the real-world impact of their research in a relatable way. By framing the research in terms of a relatable scenario, the speaker is able to engage the audience and make the research feel more relevant to their lives. Additionally, by highlighting the practical applications of the research, the speaker is able to demonstrate the value of the research in a tangible way.

Here I recommend without any second thought “ Storytelling with Data: A Data Visualization Guide for Business Professionals ” by Cole Nussbaumer Knaflic. This is one of the powerful techniques to showcase data in the form of graphs and charts.

The eighth tip for making an effective research presentation is to incorporate facts and statistics into your presentation. Facts and statistics can help you communicate the significance of your research and make it more compelling to your audience.

Make your audience curious about your topic with a fact they didn’t know. Explaining the importance of your topic to your audience is essential. Showcasing data and statistics to prove a point remains a critical strategy not just at the beginning but also throughout. Statistics can be mind-numbing but if there is some compelling information that can help further the conversation.

Here are a few examples of how you might use facts and statistics in your research presentation: