Search the site

Links to social media channels

Protecting Endangered Species

Still Only One Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy

Despite continued conservation efforts, the status of many endangered species remains unchanged. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) are the primary treaties tasked with protection of endangered species. But moving forward, species conservation efforts should expand to include lesser known species that serve important ecosystem services. ( Download PDF ) ( See all policy briefs ) ( Subscribe to ENB )

The Persian leopard (Panthera pardus tulliana), the largest subspecies of leopards, used to roam widely across Central Asia and the Caucasus. They are large spotted cats—about five feet in length—with slender hindquarters and long, thick tails. Both male and female leopards lead solitary lives, though they come together during winter mating. They are very territorial, patrolling wide home ranges to scent-mark trees, shrubs, and rocks. The leopard inhabits a wide variety of habitats: from mountain crags up to 3,000 meters in elevation, to grasslands and cold desert ecosystems, with a preference for cliff and rocky areas, as well as juniper and pistachio woodlands that give them cover for hunting.

During the past century, human-wildlife conflict, indiscriminate killing of their prey, habitat loss, and bounties incentivizing their killing have reduced their historic range by 72-84% (Jacobson et al., 2016). Today, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species—the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of species and subspecies, which uses a set of defined criteria to evaluate their extinction risk (Rodrigues et al., 2006)—the Persian leopard is endangered.

The story of the Persian leopard is the story of many species pushed by human action to the brink of extinction. Strong conservation measures can still reverse the course for some species. For many others, it is too late.

During the past century, human-wildlife conflict, indiscriminate killing of their prey, habitat loss, and bounties incentivizing their killing have reduced the leopard’s historic range by 72-84% JACOBSON ET AL., 2016

The foundations of global species conservation measures date back to the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment . Principle 2 of the Stockholm Declaration says “the natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and especially representative samples of natural ecosystems, must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations.” Principle 4 reads “Man has a special responsibility to safeguard and wisely manage the heritage of wildlife and its habitat, which are now gravely imperilled by a combination of adverse factors.”

Among the 109 recommendations found in the Stockholm Action Plan , Recommendation 99 calls for the preparation and adoption of an international treaty to regulate international trade in certain species of wild plants and animals. This treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), had been drafted as a result of a resolution adopted in 1963 at a meeting of members of IUCN. As a result of the push provided by the Stockholm Conference, the Convention was finally adopted at a meeting of representatives of 80 countries in Washington, D.C. on 3 March 1973.

There are a few other relevant recommendations. Recommendation 29 draws attention to species of wildlife that may serve as indicators for future wide environmental disturbances. Recommendation 30 emphasizes drawing attention to the situation of animals endangered by their trade value. The Stockholm Declaration and Action Plan also legitimized the role of IUCN and especially the Red List, which had been established in 1964. In fact, IUCN was one of the few environmental organizations formally involved in the preparations of the Stockholm Conference and in the drafting and implementation of the three conventions that followed it: the Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972), CITES, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (1971).

What are Endangered Species: The Role of the IUCN Red List

Since its establishment, the IUCN Red List has been the key tool to assess the status of species and catalyze action for conservation and policy change. Through the List’s rigorous assessment processes, experts linked to the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s specialist groups collect information on a species’ range, population size, habitat and ecology, use and/or trade, threats, and conservation actions that inform necessary conservation decisions.

The assessments published in the IUCN Red List are used by governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and multilateral environmental agreements. The assessments drive conservation action and funding, albeit still in insufficient ways to always ensure saving species. In fact, Betts et al. (2020) noted that without successful communication between species experts, academics, policymakers, funders, and practitioners, IUCN Red List assessments may not lead to development and implementation of conservation action plans.

The IUCN Red List has nine categories to indicate how close a species is to becoming extinct. The closest to extinction is the “critically endangered” category, with a species example being the Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), a subspecies found only in Iran that has dwindled to fewer than 50 animals remaining in the wild. The least critical category is defined as “least concern.” For example, the global brown bear (Ursus arctos) population is considered to be of “least concern” because it is large and spread over three continents, even though there are some local populations that are under threat. The categories in the middle, i.e., “vulnerable” and “endangered,” are for species considered under threat.

In other words, if a species is either critically endangered, endangered, or vulnerable, it is in popular terms “endangered.”

This mismatch between the technical terms of the IUCN Red List and common language can lead to confusion. In 2016, a re-assessment of the snow leopard prompted an outcry from some members of the conservation community due the species’ being reclassified from endangered to vulnerable (McCarthy et al., 2016). Their anger was echoed by members of the public, in part because they did not understand “being vulnerable” under IUCN Red List criteria still means at high risk of extinction.

The way a species is assessed under the IUCN Red List can also determine whether such species deserve protection under two international treaties aimed at species conservation: CITES and the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). Listing an endangered species under either of these two conventions can catalyze further action and, possibly, save a species from extinction (Zahler & Rosen, 2013).

Without successful communication between species experts, academics, policy makers, funders, and practitioners, IUCN Red List assessment may not lead to development and implementation of conservation action plans. BETTS ET AL. (2020)

Regulating the Protection of Endangered Species

CITES and CMS are the key conventions tasked with regulating protection of endangered species.

CITES regulates international trade and therefore looks at the impact of trade on species conservation. Annually, international wildlife trade is estimated to be worth billions of dollars and to include hundreds of millions of plant and animal specimens. The trade is diverse, ranging from live animals and plants to an array of products derived from them, including food, exotic leather goods, wooden musical instruments, timber, tourist curios, and medicines. Since trade in wild animals and plants crosses borders between countries, the effort to regulate it requires international cooperation to safeguard certain species from over-exploitation. Today, CITES accords varying degrees of protection to more than 37,000 species of animals and plants, whether they are traded as live specimens, fur coats, or dried herbs (CITES, n.d.)

In the language of CITES, species listed under Appendix I are considered threatened with extinction and afforded the highest level of protection, including restrictions on commercial trade. Examples of the 931 species currently listed under Appendix 1 include gorillas (Gorilla sp.), tigers (Panthera tigris), and snow leopards (Panthera uncia). Appendix II includes species that, while currently not threatened with extinction, may become so without trade controls. It also includes species that resemble other listed species and must be regulated to effectively control the trade in those other listed species. Currently 34,419 species are listed under Appendix II, including saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica), wolf (Canis lupus), argali sheep (Ovis ammon), and kiang (Equus kiang). Appendix III includes a list of wildlife and plant species identified by particular CITES parties as being in need of international trade controls.

The purpose of CMS is conservation of migratory species, their habitats, and migration routes. “Migratory” is broadly defined as species that straddle international borders (Lewis & Trouwborst, 2019). Migratory species threatened with extinction are listed in Appendix I of the Convention. Appendix I listing is a mechanism to promote conservation measures called, in CMS terminology, “Concerted Action” among the range states of the listed species. CMS parties commit to ensure strict protections under national laws and conserving their habitats, mitigating obstacles to migration, among other threats. Migratory species viewed as benefiting from international cooperation are listed in Appendix II of the Convention (CMS, n.d.). To date, seven specialized regional agreements and 19 memoranda of understanding have been concluded for Appendix II species under the CMS.

Representative Frameworks for the Conservation of Endangered Species

The development of models tailored to conservation needs throughout migratory ranges is a unique feature of the CMS. Along these lines, there are two important initiatives benefiting endangered species in Africa and Central Asia under the CMS umbrella.

One is the Central Asian Mammals Initiative (CAMI) and its associated Programme of Work. Established in 2014, CAMI aims to strengthen the conservation of Central Asian migratory mammals through a common framework to coordinate conservation activities in the region and coherently address major threats to migratory species. By developing an initiative for Central Asian mammals, CMS is catalyzing collaboration between all stakeholders, with the aim of harmonizing and strengthening the implementation of the Convention (Rosen & Roettger, 2014). One of the most recent projects under CAMI is the proposed development of a regional strategy for the conservation of the Persian leopard.

The Joint CITES-CMS African Carnivores Initiative (ACI), established in 2017, stems from the recognition of the importance of synergies and coordination of measures toward species that are protected under both Conventions. Supported by IUCN Species Survival Commission ’s specialist groups, the Secretariats are tasked to drive effective conservation of African lion, leopard, cheetah, and wild dog, and help avoid duplicate activities and associated costs, and generate funding.

By developing an initiative for Central Asian mammals, CMS is catalyzing collaboration between all stakeholders, with the aim of harmonizing and strengthening the implementation of the Convention ROSEN & ROETTGER, 2014

There are also two other important frameworks, each focused on the conservation of single species. One is the Global Tiger Initiative Council (GTIC), and the other is the Global Snow Leopard Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP).

GTIC was originally set up as the Global Tiger Initiative (GTI), a global alliance of governments, international organizations, NGOs, and the private sector, with the goal to save tigers from extinction. Established by the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Smithsonian Institution, Save the Tiger Fund, and International Tiger Coalition (representing more than 40 NGOs), the initiative is led by the 13 tiger range countries. The St. Petersburg Declaration , adopted in 2010 at the Tiger Summit in Russia, defines the priorities.

GSLEP, propelled by GTI and established in 2013, is driven by 12 snow leopard range states, NGOs, and international organizations, which sit on a steering committee. The foundation of the GSLEP is 12 individual National Snow Leopard and Ecosystems Priorities (NSLEPs). Under GSLEP, specific activities are grouped under broad themes that correspond to the commitments of the Bishkek Declaration adopted at the 2013 Global Snow Leopard Conservation Forum (Zakharenka et al., 2016).

Some of these initiatives have successfully catalyzed attention, resources, and conservation action. They have received a high level of political attention, especially GTI in Russia and GSLEP in Kyrgyzstan, as respective hosts of the Tiger Summit and Snow Leopard Forum. However, some conservationists argue, especially in relation to tigers, that results have fallen short, and lack of transparency and accountability is compromising progress in tiger conservation efforts. Slappendel (2021) writes that “tiger-range countries are responsible for making tiger conservation efforts and holding themselves accountable for their methods and results. There’s no authority above them, so they can do whatever they want.

While the reach and influence of CAMI and ACI are more limited compared to GTI and GSLEP, they have also generated important resources for conservation and could likely have a stronger policy-driving role in the future.

Generally, these four frameworks serve as important examples for directing donor resources.

The Role of UN Agencies and Donors

The GEF, established in 1992, is the largest multilateral fund focused on enabling developing countries to invest in nature. It supports the implementation of major international environmental conventions including on biodiversity, climate change, chemicals, and desertification. Endangered species prioritized under CITES and CMS, such as GTI and GSLEP, are also prioritized for GEF funding.

In 2010, the GEF indicated it would provide up to USD 50 million in grants to save the tiger through contributions to be invested by developing countries using their GEF allocations in biodiversity, supplemented by investments from its REDD+ Program (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries, and the role of conservation, sustainable use of forests, and enhancement of carbon stocks) (GEF, 2010). Since 1991, the GEF has invested nearly USD 100 million toward snow leopard projects implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The GSLEP Forum in 2013 catalyzed nine further GEF-financed, UNDP-implemented projects, representing an investment of about USD 45 million to support snow leopard range countries. These nine projects also leveraged over USD 200 million in co-financing from national and international partners (UNDP, 2016).

UNDP has emerged as one of the key implementing UN agencies when it comes to endangered species and conservation projects more broadly. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has also spearheaded initiatives for the conservation of endangered species, such as Vanishing Treasures . This EUR 9 million project, funded by the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, seeks to better understand the vulnerability to climate change of the snow leopard, tiger, and gorilla and the ecosystems being affected.

Why Do Many Species Continue to be Endangered?

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) warned in its Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services that “nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history—and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating” (IPBES, 2019).

Despite continued conservation efforts, the status of many endangered species remains unchanged—including tigers, lions, and cheetahs. The question is: Why? With our growing knowledge of the fragility of the planet’s ecosystems, why are we pushing entire species out of existence?

The limited amount of funding benefiting species research and conservation is one reason. Often these funds are short term, whereas to really see progress and results, a longer funding commitment is necessary. Some projects are also too narrowly focused on protection and enforcement, without seeking ways local communities can be part of the solution. Likewise, some projects do not address root causes of decline.

But there are also issues of capacity. In many countries that provide habitat for endangered species, there is limited technical capacity to protect such species. Local and national conservation organizations also would benefit from greater capacity building.

At the national level, species conservation may not be prioritized. This is often reflected in ministries tasked with both environment and agriculture or economic and mining issues—with the latter issues prioritized over conservation. Species conservation also does not operate in a vacuum, but must be considered alongside mechanisms to address threats to their survival, which may be exacerbated by conflicting development goals. For example, a development project aimed at improving access to water, through building dams and irrigation channels, may hurt access by salmon species to spawning grounds or damage riparian habitat. Finally, conservation organizations—with their own agendas and issues of competition for funding that leads to lack of cooperation—sometimes fail to create better synergies for conservation.

There are also many other endangered species that are not as well known or do not have the appeal of more popular endangered species, such as snow leopards or tigers. Some of these species have disappeared from large swaths of their range, including the striped hyaena (Hyaena hyaena), which can no longer be found in parts of Central Asia and Caucasus regions. The lesser-known Saint Lucia racer (Erythrolamprus ornatus), listed as Critically Endangered, numbers fewer than 20 individuals and is considered one of the rarest snakes in the world. Similarly, the Daguo Mulian tree (Magnolia grandis) is listed as critically endangered due to habitat loss for agricultural expansion and logging.

Moving Forward

Protecting iconic endangered species is still important for promoting policies and measures that can benefit entire ecosystems and many other endangered species. Nevertheless, species conservation efforts must expand to include many more species that are lesser known and serve important ecosystem services. Such efforts should also create incentives for local communities to conserve them, including through sustainable use when that is recognized as the only or the most effective measure. Finally, greater financial resources have to be allocated. Many hope the post-2020 global biodiversity framework will help guide the most pressing actions to keep entire species from being erased from our shared world.

Works Consulted

Betts, J., Young, R. P., Hilton-Taylor, C., Hoffmann, M., Rodríguez, J. P., Stuart, S. N., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2020). A framework for evaluating the impact of the IUCN Red List of threatened species. Conservation Biology: The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 34(3), 632–643. doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13454

Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (n.d.). What is CITES? cites.org/eng/disc/what.php

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. (n.d.). CMS. cms.int/en/legalinstrument/cms

Global Environment Facility. (2010). Global Environment Facility to support $50 million in grants to save the tiger. thegef.org/newsroom/news/global-environmentfacility-support-50-million-grants-save-tiger

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

Jacobson, A.P., Gerngross, P., Lemeris, Jr., J.R., Schoonover, R.F., Anco, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Durant, S.M., Farhadinia, M.S., Henschel, P., Kamler, J.F., Laguardia, A., Rostro-García, S., Stein, A.B., & Dollar, L. (2016). Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range. PeerJ 4:e1974. doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1974

Lewis, M., & Trouwborst, A. (2019). Large carnivores and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS)—definitions, sustainable use, added value, and other emerging issues. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7. frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fevo.2019.00491

McCarthy, T., Mallon, D., Jackson, R., Zahler, P., & McCarthy, K. (2017). Panthera uncia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017. Panthera uncia (Snow Leopard) (iucnredlist.org)

Rodrigues, A.S.L., Pilgrim, J.D., Lamoreux, J.F., Hoffmann, M., & Brooks, T.M. (2006). The value of the IUCN Red List for conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 21(2), 71-76. doi.org/10.1016/j. tree.2005.10.010

Rosen, T., & Roettger, C. (2014). Central Asian Mammals Initiative: Saving the last migrations. CMS. cms.int/sites/default/files/publication/Central_Asian_Mammals_Initiative.pdf

Slappendel, C. (2021). What’s stopping some countries from keeping up with tiger conservation promises? Commentary. Mongabay news.mongabay.com/2021/11/whats-stopping-some-countries-from-keeping-up-with-tiger-conservationpromises-commentary/

UNDP. (2016). Silent Roar - UNDP and GEF in the snow leopard landscape. undp.org/publications/silent-roar-undpand-gef-snow-leopard-landscape

Zahler, P., & Rosen, T. (2013). Endangered mammals. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. Elsevier.

Zakharenka, A., Sharma, K., Kochorov, C., Rutherford, B., Varma, K., Seth, A., Kushlin, A., Lumpkin, S., Seidensticker, J., Laporte, B., Tichomirow, B., Jackson, R. M., Mishra, C., Abdiev, B., Modaqiq, A. W., Wangchuk, S., Zhongtian, Z., Khanduri, S. K., Duisekeyev, B., … Yunusov, N. (2016). The Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Program. Snow Leopards, 559–573. doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-802213-9.00045-6

Additional downloads

Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Government of Sweden, Ministry of Environment

Government of Canada, Global Affairs Canada

Deep dive details, you might also be interested in, web of resilience.

Pakistan's development model has still not recognised the limits of the natural environment and the damage it would cause, if violated, to the sustainability of development and to the health and well-being of its population. Pakistan’s environment journey began with Stockholm Declaration in 1972. A delegation led by Nusrat Bhutto represented the country at the Stockholm meeting, resulting in the establishment of the Urban Affairs Division (UAD), the precursor of today’s Ministry of Climate Change. In setting the country’s environmental agenda, we were inspired by the Stockholm Principles, but in reality, we have mostly ignored them for the last five decades.

IISD in the news

June 5, 2022

The Legacies of the Stockholm Conference

Fifty years after Stockholm, we face a triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution.

June 1, 2022

The Roots of Forest Loss and Forest Governance

If lessons from past failures on deforestation are learned, forest protection could play a major role in reversing both climate change and biodiversity loss.

May 9, 2022

Pathways to Sustainable Cities

Urban planning needs to be inclusive and responsive to the needs of local communities and build on participatory approaches that foster the engagement of marginalized actors.

April 28, 2022

Why should we protect endangered animals?

The conservation of endangered species is not just a matter of ethical responsibility—it’s a fundamental necessity for the health of our planet.

Many human activities have been undeniably detrimental to many animal species, both directly and indirectly. The extinction rate of species is up to 1000 times higher than in pre-human times, and scientists suggest we are living through the planet’s sixth mass extinction. There has been a 68% decline in mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, and fish species between 1970 and 2012. We’re losing biodiversity quicker than we ever have in the past.

Preserving endangered species safeguards the intricate balance of our planet’s life, ensuring a healthier and more secure future for ecosystems and people.

At IFAW, our mission is to build a future where animals and people can thrive together. With this goal in mind, it’s essential to examine why we must protect endangered species—why are they so important? And what would our world look like without them?

Why should we protect endangered species?

Endangered species are essential for biodiversity.

We can think of biodiversity as nature’s balancing act, where all the world’s species work together to keep populations in check and protect our planet’s ecosystems. When certain species become endangered or extinct, that balance is upset, causing ripples throughout the rest of the world’s species.

Take bees as an example. These insects play a crucial role in pollinating plants, helping maintain biodiversity and ensuring the availability of fruits, vegetables, and nuts in our ecosystems.

With globally declining numbers of bee populations , including some species such as the Potter Flower Bee and the Cliff Mason Bee becoming regionally extinct, there is a concern that there will be significant consequences for food security and ecosystem health.

Indicators of environmental health

Endangered species can also serve as indicators of environmental health. When populations decline, it can signify underlying issues such as habitat destruction, pollution, or climate change, which, if unaddressed, can threaten the stability of the entire ecosystem and many other species.

For example, declining populations of bald eagles in North America allowed scientists to discover that the environment had been contaminated with DDT , a pesticide used to control mosquitoes and other insects. In this way, the bald eagle served as a warning sign for the environmental damage being done by DDT, allowing a ban on the chemical to be put in place and eagle populations to recover along with the environment.

Climate change hinges on biodiversity

Climate change is closely linked to biodiversity loss . So protecting—and restoring—biodiverse ecosystems is vital in the fight against climate change.

Biodiversity helps ecosystems adapt to climate change, as various plant and animal species can sequester carbon dioxide, regulate temperatures, and support resilience in the face of climate impacts. When biodiversity is reduced due to habitat destruction or species loss, ecosystems become more vulnerable and compromised.

IFAW champions nature-based solutions to climate change , which involve protecting animals—as they hold the key to protecting their ecosystems and mitigating climate change simply through their natural functions.

Meanwhile, climate change contributes to habitat loss and rising temperatures that further endanger these animals, creating a sort of feedback loop. With a 4.3°C increase in global temperatures, 16% of the world’s species would be driven to extinction.

Currently, more than 25% of animals on the IUCN endangered species list are threatened by climate change. Scientists predict that one third of all animal and plant species will be under threat due to climate change by the year 2070.

How endangered species benefit the animal and plant life around them

Certain animals are known as ‘ ecosystem engineers ’ because they help protect their environments and habitats through their feeding and other behaviors.

Below are some examples of ecosystem engineers. To note here, each of these animals encompasses a broad range of different species and each animal group contains species that are classified as endangered.

- Sharks : Thanks to their position near the top of the food chain, sharks help regulate prey populations, which helps maintain the balance of marine food webs . It’s an intricate system—if snapper and grouper become too numerous on coral reefs because of limited reef shark populations to prey on them, these mesopredator fish will over consume their food source: algae-eating fish. Without adequate populations of algae-eating fish, algae may take over, smothering and killing the coral.

- Elephants : These gentle giants traverse the savannah, eating 140-300 kg (300-400 lbs) of food every single day. While walking through their habitat, elephants disperse seeds through their waste , sometimes as much as 60 kilometers away from where the plants were eaten. Elephant dung is an excellent fertilizer, facilitating new growth from their undigested seeds. These plants colonize new areas and eventually create new habitats and food for a range of other animals.

- Seals : These marine mammals act as both predators (of fish, squid, shellfish, seabirds, and other marine life) and as prey for hunters (like polar bears, orcas, and sharks)—all of which help to maintain balance in the food web. When seals swim through the ocean, they create currents which cycle nutrients from the sea to the shore, essential for plant growth and survival.

Endangered species are important for culture and tradition

Returning to our goal of helping animals and people thrive together, we must also consider that many animals are integral parts of cultures, traditions, and folklore worldwide.

For example, in Mexico, Monarch butterflies are culturally significant to the Mazahua people. When they land in central Mexico at the end of their 4,000-kilometre migration, they are viewed as the spirits of the dead returning for a visit, and their arrival coincides with traditional Day of the Dead celebrations.

Monarchs were classified as endangered by the IUCN in 2022. Losing this butterfly species would have both ecological and cultural impacts.

Similarly, African savannah elephants have deep connections with indigenous groups. For example, the Kwhe culture believes that elephants were once human and transformed into animals while maintaining the wisdom and connection to their people.

Protecting endangered species is also a fight to protect cultures and traditions worldwide.

Humans must protect endangered animals because human activity is a major threat

We’re currently experiencing the sixth mass extinction event, marked by alarming declines in the number of insects, vertebrates, and plant species worldwide. Left unchecked, this could completely change the planet as we know it, devastating ecosystems and life across the globe.

Mass extinction occurs when around 75% of the world’s species go extinct within a short time period. There have been five known mass extinctions throughout Earth’s history, and researchers believe we are now in the midst of the sixth.

However, unlike the five that have come before, this sixth mass extinction is primarily due to human activity. It’s come about through a combination of factors, including habitat destruction, deforestation, pollution, over-exploitation of natural resources, introduction of invasive species, and climate change.

These activities have led to widespread biodiversity loss and countless species’ decline or extinction. Therefore, it’s our responsibility to protect those same species and the environments they inhabit and influence. This necessitates changing behaviors, activities, and policies. Urgent international action is needed to reverse humans’ effects on the environment.

How can you help protect endangered species?

Despite the uncertain future we face as we grapple with climate change and habitat loss, there is hope for endangered species. Thanks to policy and conservation efforts, there are many species that have made or are in the midst of making recoveries .

The easiest way you can help protect endangered species is to learn more about them. See our list of the most endangered mammals and our endangered species glossary.

Though IFAW undertakes large-scale conservation efforts across the planet, we also believe in the impact of small acts.

You can do simple things to help protect biodiversity, such as:

- Rewild your garden to encourage pollinators

- Join a community beach cleanup and reduce harmful pollution in our waterways

- Buy eco-friendly cleaning products that don’t contain damaging chemicals

- Introduce one or two meat-free dinners each week

- Put a bell on your cat’s collar to reduce the chance of them attacking native wildlife

- Support wildlife conservation experts

For more ideas, check out our list of 50 simple actions you can take to help animals.

Making a difference starts with taking action. Get involved by signing our petitions and making your voice heard for the animals that need you most.

Press releases

IFAW calls on EU candidates and citizens to put environment at top of election agenda

Giving Day for Elephants

Koala facts and statistics

Our work can’t get done without you. Please give what you can to help animals thrive.

Unfortunately, the browser you use is outdated and does not allow you to display the site correctly. Please install any of the modern browsers, for example:

US Environmental Policy

Preserving life: the endangered species act’s journey and future.

By Brady Kim

Since its inception in 1973, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) has been a cornerstone of environmental legislation in the United States. It reaffirmed the nation’s commitment to preserving biodiversity and protecting endangered species. The ESA has and continues to have significant successes in facilitating the recovery of many endangered species. In fact, over 90% of the plants and wildlife the law covers are recovering on schedule. [1] In recent years however, the act has been caught in the middle of partisan crosshairs. [2] In 2019, the Trump administration significantly weakened the act and despite revisions from the Biden administration in 2024 many conservationists don’t believe the changes are enough. [3] Endangered Species Act proponents must tap into humanity’s affection for animals and underscore its crucial role in maintaining environmental balance to garner broader public support, increased funding, and bipartisan backing to bolster the ESA’s effectiveness.

The ESA’s legacy of success is evident in the remarkable recoveries of species once on the brink of extinction. The most iconic example is the bald eagle, whose population rebounded from just a few hundred pairs in the lower 48 states in the 1960s to over 10,000 pairs today, thanks in large part to actions taken by the ESA. [4] Similarly, the American alligator, once on the verge of extinction due to habitat loss and overhunting, has made a remarkable recovery and is now thriving in its native habitats across the southeastern United States. [5]

The species listed above are among over 2,300 species the ESA currently protects. When a species becomes threatened or endangered, the ESA is able to step in and prohibit importing, exporting and selling of the species. [6] The ESA also prohibits destruction of natural habitats which is part of the contentiousness of the act, but also essential. Ecosystems are completely interconnected and the health of one species affects the entirety. The ESA’s protection of these at-risk species has far-reaching implications.

Looking ahead, the ESA faces a new set of challenges that threaten to undermine its effectiveness in conserving biodiversity. Chief among these challenges is our lack of funding and continual weakening of the act. Today, the ESA is only funded at 40 percent of what it needs to protect all endangered or threatened species. [7] Specifically, this limits the capacity of agencies to effectively monitor species populations, protect critical habitats, and mitigate threats. With regards to the weakening of the act, in 2019 the Trump administration removed blanket protections for plants and animals right when they are classified as threatened. [8] The administration also notably allowed economic considerations when giving protections. [9] More recently, the Biden administration reversed these, however conservationists are worried that a Trump 2024 election will revert the changes.

These two challenges to the effectiveness of the ESA are exacerbated by the existential threat of climate change which is exacerbating habitat loss, altering ecosystems, and increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events. In Washington State where I am from, rising sea levels from climate change is heavily impacting Chinook Salmon populations. A lack of freshwater streams due to less glaciers inhibits the salmon from migrating from freshwater to the ocean. This essential cycle of life for salmons is detrimental to their population. [10] The increasing complexity of conserving at-risk species.

To adapt to these issues, ESA proponents need to focus on recreating the act as a staple of bipartisan support to protect our environment and species that are essential. The first way this can be done is by strategically leveraging iconic species like the grizzly bear and the bald eagle, which hold significant cultural and symbolic value in America, to garner bipartisan support. By convincing the public that the EPA is necessary for the survival of countless species such as the bald eagle more people will be inclined to show active rather than passive support. EPA proponents can also emphasize the economic benefits associated with protecting these iconic species, such as increased tourism revenue from wildlife viewing and ecotourism, can appeal to fiscal conservatives. [11]

The second way this can be done is through communicating the importance of saving critical species by emphasizing their indispensable role in maintaining healthy ecosystems, which contribute to people’s well-being. Advocates can show how the loss of even one species can trigger cascading effects, destabilizing entire ecosystems, and jeopardizing vital ecosystem services upon which humans rely. For instance, bees and other pollinators play a crucial role in the reproduction of many plants, including those that provide us with food. It is estimated that three-fourths of the world’s flowering plants and about 35 percent of the world’s food crops depend on animal pollinators to reproduce. [12] The EPA plays a critical role in preserving the species that hold importance to human health and sustenance.

The Endangered Species Act has been a critical tool in preserving biodiversity and preventing extinctions, but its effectiveness is increasingly challenged by lack of funding and support. To ensure the Act’s continued relevance and success, we must gain bipartisan support from lawmakers and citizens alike. By taking proactive measures to address these challenges, we can chart a sustainable path forward for the ESA and protect endangered species for years to come.

[1] “Celebrating 50 Years of Endangered Species Act Success.” Center for Biological Diversity, Center for Biological Diversity, 3 Feb. 2023, biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/celebrating-50-years-of-endangered-species-act-success-2023-02-02/.

[2] “Species under Siege: Why the Endangered Species Act Is in Congressional Crosshairs.” Defenders of Wildlife, defenders.org/blog/2023/03/species-under-siege-why-endangered-species-act-congressional-crosshairs. Accessed 11 Apr. 2024.

[3] Press, The Associated. “Biden Administration Restores Threatened Species Protections Dropped by Trump.” NPR, NPR, 28 Mar. 2024, www.npr.org/2024/03/28/1241467876/threatened-species-protections-restored .

[4] “Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus Leucocephalus): U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.” FWS.Gov, www.fws.gov/species/bald-eagle-haliaeetus-leucocephalus. Accessed 11 Apr. 2024.

[5] “Conservation Comeback: The American Alligator.” Wild Hope, 10 Jan. 2024, www.wildhope.tv/article/the-americanalligator/#:~:text=The%20tide%20finally%20began%20to,in%20the%20southeastern%20United%20States

[6] F., Cynthia, and Hodges. “Full Title Name: Brief Summary of the Endangered Species Act (ESA).” Animal Law Legal Center, 1 Jan. 1970, www.animallaw.info/article/brief-summary-endangered-species-act#:~:text=With%20certain%20exceptions%2C%20the%20ESA,destruction%20of%20their%20critical%20habitat .

[7] Rice, Bonnie. “Celebrating the Endangered Species Act on Capitol Hill.” Sierra Club, www.sierraclub.org/articles/2023/09/celebrating-endangered-species-act-capitol-hill#:~:text=However%2C%20despite%20its%2099%25%20success,amendments%20in%20major%20congressional%20bills. Accessed 11 Apr. 2024.

[8] Brown, Matthew. “Biden Administration Restores Threatened Species Protections Dropped by Trump.” AP News, AP News, 28 Mar. 2024, apnews.com/article/biden-threatened-species-protections-9f5a2c12e51a857ae32b85997b54dcc7.

[9] Lambert, Jonathan. “Trump Administration Weakens Endangered Species Act.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 12 Aug. 2019, www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02439-1#:~:text=President%20Donald%20Trump’s%20administration%20is,whether%20to%20protect%20a%20species .

[10] Mapes, Lynda V., et al. “Endangered Species Act Turns 50: What 6 NW Animals Can Tell Us.” The Seattle Times, The Seattle Times Company, 4 Jan. 2024, www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/environment/endangered-species-acts-50th-anniversary-what-6-nw-animals-can-tell-us/ .

[11] Worland, Justin. “Endangered Species Act Has Economic Benefits – and Costs.” Time, Time, 25 July 2018, time.com/5347260/endangered-species-act-reform/.

[12] “The Importance of Pollinators.” USDA, www.usda.gov/peoples-garden/pollinators. Accessed 11 Apr. 2024.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

2 thoughts on “ Preserving Life: The Endangered Species Act’s Journey and Future ”

The Endangered Species Act is the cornerstone for protecting endangered animals and habitats in the United States. As Brady states in his blog, the ESA is often changed by the current presidential administration in office. As we approach the next election it is important to remember the power that comes with electing a president or any official to office. In my own research, I uncovered a few ways that I can personally promote the preservation of the ESA. One example would be to learn more about the ESA and specific species in my local area and how I can help them recover. It is also important to voice support for the ESA in local and state governments. Templates can be found online for emails addressed to members of Congress, urging them to preserve the ESA. Influence can be used locally too, by writing letters to local newspapers discussing the importance of the ESA or by attending local meetings for city organizations or governments to voice the importance of preserving endangered species. As always, awareness of political candidates’ positions on the ESA is crucial when voting. Through conscious efforts, we can all show support for the ESA and the protection of endangered and threatened species.

Hey! I like how your discussion emphasizes a multi-faceted approach to garner bipartisan support and public backing for the ESA. Many of these animals hold cultural significance and can inspire national pride and can be used to broaden public interest in biodiversity conservation. Furthermore, I do believe the economic benefits of protecting endangered species—such as increased tourism revenue and ecotourism. Emphasizing the interconnectedness of ecosystems can highlight the broader consequences of losing even a single species in the food chain that can destabilize entire ecosystems and even our way of life. I hope ESA proponents can foster support that transcends political divides, ensuring the preservation America’s natural heritage and beautiful environments.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Biodiversity: What is it and how can we protect it?

Facebook Twitter Print Email

The UN and its global partners will grapple with the massive loss of animal and plant species and how to avoid further extinction at a major conference beginning 23 January. Here’s a primer on what exactly biodiversity is and how the UN can help support efforts to enable nature to survive and thrive.

What does 'biodiversity' mean and why is it important?

In simple terms, biodiversity refers to all types of life on Earth. The UN Convention on Biological Diversity ( CBD ) describes it as “the diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems, including plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi”. These three levels work together to create life on Earth, in all its complexity.

The diversity of species keep the global ecosystem in balance, providing everything in nature that we, as humans, need to survive, including food, clean water, medicine and shelter. Over half of global GDP is strongly dependent on nature. More than one billion people rely on forests for their livelihoods.

Biodiversity is also our strongest natural defence against climate change . Land and ocean ecosystems act as “carbon sinks”, absorbing more than half of all carbon emissions.

Why are we talking about it now?

Because the first big push of the year to put the UN’s bold plan to protect biodiversity into practice takes place in the Swiss capital, Bern , between 23 and 25 January.

Introducing the conference, Patricia Kameri-Mbote, Director of the United Nations Environment Programme ( UNEP ) Law Division, warned that the lack of coordination between the various organizations trying to protect biodiversity is a “critical challenge” that needs to be urgently overcome “as we strive for a world living in harmony with nature by 2050”. A key aim of the conference will be to solve that problem by pulling together the various initiatives taking place across the world.

Is there a crisis?

Yes. It’s very serious, and it needs to be urgently tackled.

Starting with the natural and land sea carbon sinks mentioned above. They are being degraded, with examples including the deforestation of the Amazon and the disappearance of salt marshes and mangrove swamps, which remove large amounts of carbon. The way we use the land and sea is one of the biggest drivers of biodiversity loss. Since 1990, around 420 million hectares of forest have been lost through conversion to other land uses. Agricultural expansion continues to be the main driver of deforestation, forest degradation and forest biodiversity loss.

Other major drivers of species decline include overfishing and the introduction of invasive alien species (species that have entered and established themselves in the environment outside their natural habitat, causing the decline or even extinction of native species and negatively affecting ecosystems).

These activities, UNEP has shown , are pushing around a million species of plants and animals towards extinction. They range from the critically endangered South China tiger and Indonesian orangutans to supposedly “ common” animals and plants, such as giraffes and parrots as well as oak trees, cacti and seaweed. This is the largest loss of life since the dinosaurs.

Combined with skyrocketing levels of pollution, the degradation of the natural habitat and biodiversity loss are having serious impacts on communities around the world. As global temperatures rise, once fertile grasslands turn to desert, and in the ocean, there are hundreds of so-called “dead zones”, where scarcely any aquatic life remains.

The loss of biodiversity affects the way an ecosystem functions, leading to species being less able to respond to changes in the environment and making them increasingly vulnerable to natural disasters. If an ecosystem has a wide diversity of organisms, it is likely that they will not all be affected in the same way. For instance, if one species is killed off then a similar species can take its place.

What is the Biodiversity Plan?

The Plan, officially called the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework , is a UN-driven landmark agreement adopted by 196 countries to guide global action on nature through to 2030, which was hashed out at meetings in Kunming, China and Montreal, Canada, in 2022.

The aim is to address biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and protect indigenous rights. Indigenous peoples suffer disproportionately from loss of biological diversity and environmental degradation. Their lives, survival, development chances, knowledge, environment and health conditions are threatened by environmental degradation, large scale industrial activities, toxic waste, conflicts and forced migration as well as by land-use and land-cover changes such as deforestation for agriculture and extractives.

There are concrete measures to halt and reverse nature loss, including putting 30 per cent of the planet and 30 per cent of degraded ecosystems under protection by 2030. Currently 17 per cent of land and around eight per cent of marine areas are protected. The plan also contains proposals to increase financing to developing countries – a major sticking point during talks – and indigenous peoples.

Countries have to come up with national biodiversity strategies and action plans as well as set or revise national targets to match the ambition of global goals.

What else will the UN do to protect biodiversity this year?

Next month the UN Environment Assembly ( UNEA ), otherwise known as the “World’s Environment Parliament” will meet at the UN office in Nairobi . The event brings together governments, civil society groups, the scientific community and the private sector to highlight the most pressing issues and improve global governance of the environment. UNEA 2024 will focus on climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

However, the main event will be the UN Biodiversity Conference , which will take place in Colombia in October. Delegates will discuss how to restore lands and seas in a way that protects the planet and respects the rights of local communities.

- biodiversity

It’s not too late to save them: 5 ways to improve the government’s plan to protect threatened wildlife

Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

DECRA Research Fellow, University of Sydney

Professor in Terrestrial Ecology, Deakin University

Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW Sydney

ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Euan Ritchie receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the Australian Federal Government’s Bushfire Recovery Program, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, WWF and Parks Victoria. Euan Ritchie is a Director (Media Working Group) and member of the Ecological Society of Australia, and a member of the Australian Mammal Society.

Ayesha Tulloch receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the NSW Government's Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. She is the Vice President of Public Policy and Outreach and co-convenes the Science Communication Chapter for the Ecological Society of Australia, and sits on Birdlife Australia's Research and Conservation Committee. She is a member of eBird Australia, the Society for conservation Biology and the University of Sydney's Charles Perkins Centre Citizen Science Node.

Don Driscoll receives funding from the Herman Slade Foundation, OEH NSW Environmental Grants program, DELWP Vic, National Geographic, Rufford Foundation, WWF and Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Australian Government Bushfire Recovery program. He is Director of the Centre of Integrative Ecology and Director of the TechnEcology Research Network at Deakin University. Don is a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and Society for Conservation Biology.

Megan C Evans receives funding from the Australian Research Council as part of a Discovery Early Career Research Award. Previously she has been funded by the National Environmental Science Program's Threatened Species Recovery Hub.

Tim Doherty is Chair of the Policy Committee for the Society for Conservation Biology Oceania and a member of the Ecological Society of Australia. He receives funding from the Hermon Slade Foundation, Australian Academy of Science, Australian Research Council and NSW Environmental Trust.

University of Sydney , Deakin University , and UNSW Sydney provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Australia’s Threatened Species Strategy — a five-year plan for protecting our imperilled species and ecosystems — fizzled to an end last year. A new 10-year plan is being developed to take its place, likely from March.

It comes as Australia’s list of threatened species continues to grow. Relatively recent extinctions , such as the Christmas Island forest skink, Bramble Cay melomys and smooth handfish , add to an already heavy toll .

Now, more than ever, Australia’s remarkable species and environments need strong and effective policies to strengthen their protection and boost their recovery.

So as we settle into the new year, let’s reflect on what’s worked and what must urgently be improved upon, to turn around Australia’s extinction crisis.

Read more: Let there be no doubt: blame for our failing environment laws lies squarely at the feet of government

How effective was the first Threatened Species Strategy?

The Threatened Species Strategy is a key guiding document for biodiversity conservation at the national level. It identifies 70 priority species for conservation, made up of 20 birds, 20 mammals and 30 plants, such as the plains-wanderer, malleefowl, eastern quoll, greater bilby, black grevillea and Kakadu hibiscus.

These were considered among the most urgent in need of assistance of the more than 1,800 threatened species in Australia.

The strategy also identifies targets such as numbers of feral cats to be culled , and partnerships across industry, academia and government key to making the strategy successful.

The original strategy (2015-20) was eagerly welcomed for putting the national spotlight on threatened species conservation. It has certainly helped raise awareness of its priority species.

However, there’s little evidence the strategy has had a significant impact on threatened species conservation to date.

The midterm report in 2019 found only 35% of the priority species (14 in total) had improving trajectories compared to before the strategy (pre-2015). This number included six species — such as the brush-tailed rabbit-rat and western ringtail possum — that were still declining, but just at a slower rate.

On average, the trends of threatened mammal and bird populations across Australia are not increasing.

Other targets, such as killing two million feral cats by 2020, were not explicitly linked to measurable conservation outcomes, such as an increase in populations of threatened native animals. Because of this, it’s difficult to judge their success.

Read more: Feral cat cull: why the 2 million target is on scientifically shaky ground

What needs to change?

The previous strategy focused very heavily on feral cats as a threat and less so on other important and potentially compounding threats , particularly habitat destruction and degradation.

For instance, land clearing has contributed to a similar number of extinctions in Australia (62 species) as introduced animals such as feral cats (64).

In fact, 2018 research found agricultural activities affect at least 73% of invertebrates, 82% of birds, 69% of amphibians and 73% of mammals listed as threatened in Australia. Urban development and climate change threaten up to 33% and 56% of threatened species, respectively.

Read more: The buffel kerfuffle: how one species quietly destroys native wildlife and cultural sites in arid Australia

Other important threats to native Australian species include pollution, feral herbivores (such as horses and goats), very frequent or hot bushfires and weeds. Buffel grass was recently identified as a major emerging threat to Australia’s biodiversity, with the risk being as high as the threat posed by cats and foxes.

Five vital improvements

We made a submission to the Morrison government when the Threatened Species Strategy was under review. Below, we detail our key recommendations.

1. A holistic and evidence-based approach encompassing the full range of threats

This includes reducing rates of land clearing — a major and ongoing issue, but largely overlooked in the previous strategy.

2. Formal prioritisation of focal species, threats and actions

The previous strategy focused heavily on a small subset of the more than 1,800 threatened species and ecosystems in Australia. It mostly disregarded frog, reptile, fish and invertebrate species also threatened with extinction.

To reduce bias towards primarily “charismatic” species, the federal government should use an evidence-based prioritisation approach, known as “decision science”, like they do in New South Wales , New Zealand and Canada . This would ensure funds are spent on the most feasible and beneficial recovery efforts.

3. Targets linked to clear and measurable conservation outcomes

Some targets in the first Threatened Species Strategy were difficult to measure, not explicitly linked to conservation outcomes, or weak. Targets need to be more specific.

For example, a target to “improve the trajectory” of threatened species could be achieved if extinction is occurring at a slightly slower rate. Alternatively, a target to “improve the conservation status” of a species is achieved if new assessments rate it as “vulnerable” rather than “endangered”.

4. Significant financial investment from government

Investing in conservation reduces biodiversity loss . A 2019 study found Australia’s listed threatened species could be recovered for about A$1.7 billion per year . This money could be raised by removing harmful subsidies that directly threaten biodiversity , such as those to industries emitting large volumes of greenhouse gases.

The first strategy featured a call for co-investment from industry . But this failed to attract much private sector interest, meaning many important projects aimed at conserving species did not proceed.

5. Government leadership, coordination and policy alignment

The Threatened Species Strategy should be aligned with Australia’s international obligations such as the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and the federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (which is also currently being reviewed ). This will help foster a more coherent and efficient national approach to threatened species conservation.

There are also incredible opportunities to better align threatened species conservation with policies and investment in climate change mitigation and sustainable agriculture .

The benefits of investing heavily in wildlife reach beyond preventing extinctions. It would generate many jobs, including in regional and Indigenous communities .

Protecting our natural heritage is an investment, not a cost. Now is the time to seize this opportunity.

Read more: Scientists re-counted Australia's extinct species, and the result is devastating

- Agriculture

- Conservation

- Endangered species

- Wildlife conservation

- Habitat destruction

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

November 1, 2023

20 min read

Can We Save Every Species from Extinction?

The Endangered Species Act requires that every U.S. plant and animal be saved from extinction, but after 50 years, we have to do much more to prevent a biodiversity crisis

By Robert Kunzig

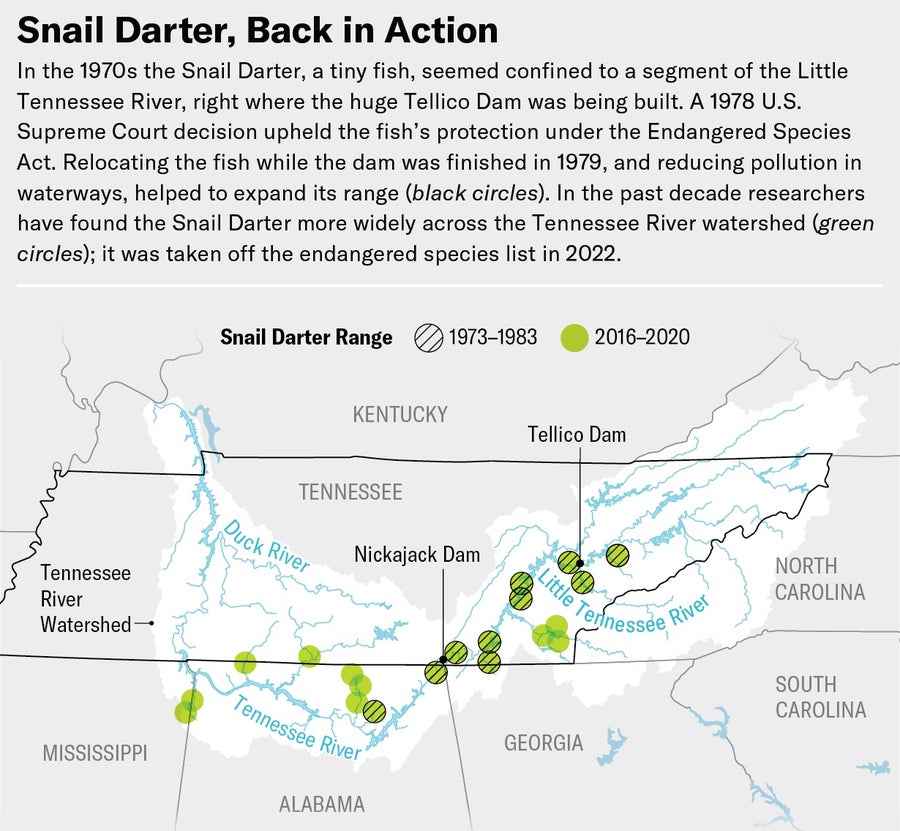

Snail Darter Percina tanasi. Listed as Endangered: 1975. Status: Delisted in 2022.

© Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

A Bald Eagle disappeared into the trees on the far bank of the Tennessee River just as the two researchers at the bow of our modest motorboat began hauling in the trawl net. Eagles have rebounded so well that it's unusual not to see one here these days, Warren Stiles of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told me as the net got closer. On an almost cloudless spring morning in the 50th year of the Endangered Species Act, only a third of a mile downstream from the Tennessee Valley Authority's big Nickajack Dam, we were searching for one of the ESA's more notorious beneficiaries: the Snail Darter. A few months earlier Stiles and the FWS had decided that, like the Bald Eagle, the little fish no longer belonged on the ESA's endangered species list. We were hoping to catch the first nonendangered specimen.

Dave Matthews, a TVA biologist, helped Stiles empty the trawl. Bits of wood and rock spilled onto the deck, along with a Common Logperch maybe six inches long. So did an even smaller fish; a hair over two inches, it had alternating vertical bands of dark and light brown, each flecked with the other color, a pattern that would have made it hard to see against the gravelly river bottom. It was a Snail Darter in its second year, Matthews said, not yet full-grown.

Everybody loves a Bald Eagle. There is much less consensus about the Snail Darter. Yet it epitomizes the main controversy still swirling around the ESA, signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard Nixon: Can we save all the obscure species of this world, and should we even try, if they get in the way of human imperatives? The TVA didn't think so in the 1970s, when the plight of the Snail Darter—an early entry on the endangered species list—temporarily stopped the agency from completing a huge dam. When the U.S. attorney general argued the TVA's case before the Supreme Court with the aim of sidestepping the law, he waved a jar that held a dead, preserved Snail Darter in front of the nine judges in black robes, seeking to convey its insignificance.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now I was looking at a living specimen. It darted around the bottom of a white bucket, bonking its nose against the side and delicately fluttering the translucent fins that swept back toward its tail.

“It's kind of cute,” I said.

Matthews laughed and slapped me on the shoulder. “I like this guy!” he said. “Most people are like, ‘Really? That's it?’ ” He took a picture of the fish and clipped a sliver off its tail fin for DNA analysis but left it otherwise unharmed. Then he had me pour it back into the river. The next trawl, a few miles downstream, brought up seven more specimens.

In the late 1970s the Snail Darter seemed confined to a single stretch of a single tributary of the Tennessee River, the Little Tennessee, and to be doomed by the TVA's ill-considered Tellico Dam, which was being built on the tributary. The first step on its twisting path to recovery came in 1978, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, surprisingly, that the ESA gave the darter priority even over an almost finished dam. “It was when the government stood up and said, ‘Every species matters, and we meant it when we said we're going to protect every species under the Endangered Species Act,’” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus. Listed as Endangered: 1967. Status: Delisted in 2007. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

Today the Snail Darter can be found along 400 miles of the river's main stem and multiple tributaries. ESA enforcement has saved dozens of other species from extinction. Bald Eagles, American Alligators and Peregrine Falcons are just a few of the roughly 60 species that had recovered enough to be “delisted” by late 2023.

And yet the U.S., like the planet as a whole, faces a growing biodiversity crisis. Less than 6 percent of the animals and plants ever placed on the list have been delisted; many of the rest have made scant progress toward recovery. What's more, the list is far from complete: roughly a third of all vertebrates and vascular plants in the U.S. are vulnerable to extinction, says Bruce Stein, chief scientist at the National Wildlife Federation. Populations are falling even for species that aren't yet in danger. “There are a third fewer birds flying around now than in the 1970s,” Stein says. We're much less likely to see a White-throated Sparrow or a Red-winged Blackbird, for example, even though neither species is yet endangered.

The U.S. is far emptier of wildlife sights and sounds than it was 50 years ago, primarily because habitat—forests, grasslands, rivers—has been relentlessly appropriated for human purposes. The ESA was never designed to stop that trend, any more than it is equipped to deal with the next massive threat to wildlife: climate change. Nevertheless, its many proponents say, it is a powerful, foresightful law that we could implement more wisely and effectively, perhaps especially to foster stewardship among private landowners. And modest new measures, such as the Recovering America's Wildlife Act—a bill with bipartisan support—could further protect flora and fauna.

That is, if special interests don't flout the law. After the 1978 Supreme Court decision, Congress passed a special exemption to the ESA allowing the TVA to complete the Tellico Dam. The Snail Darter managed to survive because the TVA transplanted some of the fish from the Little Tennessee, because remnant populations turned up elsewhere in the Tennessee Valley, and because local rivers and streams slowly became less polluted following the 1972 Clean Water Act, which helped fish rebound.

Under pressure from people enforcing the ESA, the TVA also changed the way it managed its dams throughout the valley. It started aerating the depths of its reservoirs, in some places by injecting oxygen. It began releasing water from the dams more regularly to maintain a minimum flow that sweeps silt off the river bottom, exposing the clean gravel that Snail Darters need to lay their eggs and feed on snails. The river system “is acting more like a real river,” Matthews says. Basically, the TVA started considering the needs of wildlife, which is really what the ESA requires. “The Endangered Species Act works,” Matthews says. “With just a little bit of help, [wildlife] can recover.”

The trouble is that many animals and plants aren't getting that help—because government resources are too limited, because private landowners are alienated by the ESA instead of engaged with it, and because as a nation the U.S. has never fully committed to the ESA's essence. Instead, for half a century, the law has been one more thing that polarizes people's thinking.

I t may seem impossible today to imagine the political consensus that prevailed on environmental matters in 1973. The U.S. Senate approved the ESA unanimously, and the House passed it by a vote of 390 to 12. “Some people have referred to it as almost a statement of religion coming out of the Congress,” says Gary Frazer, who as assistant director for ecological services at the FWS has been overseeing the act's implementation for nearly 25 years.

Gopher Tortoise Gopherus polyphemus . Listed as Threatened: 1987. Status: Still threatened. Credit: ©Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

But loss of faith began five years later with the Snail Darter case. Congresspeople who had been thinking of eagles, bears and Whooping Cranes when they passed the ESA, and had not fully appreciated the reach of the sweeping language they had approved, were disabused by the Supreme Court. It found that the legislation had created, “wisely or not ... an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species,” Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said after the Snail Darter case concluded. Even a recently discovered tiny fish had to be saved, “whatever the cost,” he wrote in the decision.

Was that wise? For both environmentalists such as Curry and many nonenvironmentalists, the answer has always been absolutely. The ESA “is the basic Bill of Rights for species other than ourselves,” says National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore, who is building a “photo ark” of every animal visible to the naked eye as a record against extinction. (He has taken studio portraits of 15,000 species so far.) But to critics, the Snail Darter decision always defied common sense. They thought it was “crazy,” says Michael Bean, a leading ESA expert, now retired from the Environmental Defense Fund. “That dichotomy of view has remained with us for the past 45 years.”

According to veteran Washington, D.C., environmental attorney Lowell E. Baier, author of a new history called The Codex of the Endangered Species Act, both the act itself and its early implementation reflected a top-down, federal “command-and-control mentality” that still breeds resentment. FWS field agents in the early days often saw themselves as combat biologists enforcing the act's prohibitions. After the Northern Spotted Owl's listing got tangled up in a bitter 1990s conflict over logging of old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, the FWS became more flexible in working out arrangements. “But the dark mythology of the first 20 years continues in the minds of much of America,” Baier says.

Credit: June Minju Kim ( map ); Source: David Matthews, Tennessee Valley Authority ( reference )

The law can impose real burdens on landowners. Before doing anything that might “harass” or “harm” an endangered species, including modifying its habitat, they need to get a permit from the FWS and present a “habitat conservation plan.” Prosecutions aren't common, because evidence can be elusive, but what Bean calls “the cloud of uncertainty” surrounding what landowners can and cannot do can be distressing.

Requirements the ESA places on federal agencies such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management—or on the TVA—can have large economic impacts. Section 7 of the act prohibits agencies from taking, permitting or funding any action that is likely to “jeopardize the continued existence” of a listed species. If jeopardy seems possible, the agency must consult with the FWS first (or the National Marine Fisheries Service for marine species) and seek alternative plans.

“When people talk about how the ESA stops projects, they've been talking about section 7,” says conservation biologist Jacob Malcom. The Northern Spotted Owl is a strong example: an economic analysis suggests the logging restrictions eliminated thousands of timber-industry jobs, fueling conservative arguments that the ESA harms humans and economic growth.

In recent decades, however, that view has been based “on anecdote, not evidence,” Malcom claims. At Defenders of Wildlife, where he worked until 2022 (he's now at the U.S. Department of the Interior), he and his colleagues analyzed 88,290 consultations between the FWS and other agencies from 2008 to 2015. “Zero projects were stopped,” Malcom says. His group also found that federal agencies were only rarely taking the active measures to recover a species that section 7 requires—like what the TVA did for the Snail Darter. For many listed species, the FWS does not even have recovery plans.

Endangered species also might not recover because “most species are not receiving protection until they have reached dangerously low population sizes,” according to a 2022 study by Erich K. Eberhard of Columbia University and his colleagues. Most listings occur only after the FWS has been petitioned or sued by an environmental group—often the Center for Biological Diversity, which claims credit for 742 listings. Years may go by between petition and listing, during which time the species' population dwindles. Noah Greenwald, the center's endangered species director, thinks the FWS avoids listings to avoid controversy—that it has internalized opposition to the ESA.

He and other experts also say that work regarding endangered species is drastically underfunded. As more species are listed, the funding per species declines. “Congress hasn't come to grips with the biodiversity crisis,” says Baier, who lobbies lawmakers regularly. “When you talk to them about biodiversity, their eyes glaze over.” Just this year federal lawmakers enacted a special provision exempting the Mountain Valley Pipeline from the ESA and other challenges, much as Congress had exempted the Tellico Dam. Environmentalists say the gas pipeline, running from West Virginia to Virginia, threatens the Candy Darter, a colorful small fish. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided a rare bit of good news: it granted the FWS $62.5 million to hire more biologists to prepare recovery plans.

The ESA is often likened to an emergency room for species: overcrowded and understaffed, it has somehow managed to keep patients alive, but it doesn't do much more. The law contains no mandate to restore ecosystems to health even though it recognizes such work as essential for thriving wildlife. “Its goal is to make things better, but its tools are designed to keep things from getting worse,” Bean says. Its ability to do even that will be severely tested in coming decades by threats it was never designed to confront.

T he ESA requires a species to be listed as “threatened” if it might be in danger of extinction in the “foreseeable future.” The foreseeable future will be warmer. Rising average temperatures are a problem, but higher heat extremes are a bigger threat, according to a 2020 study.

Scientists have named climate change as the main cause of only a few extinctions worldwide. But experts expect that number to surge. Climate change has been “a factor in almost every species we've listed in at least the past 15 years,” Frazer says. Yet scientists struggle to forecast whether individual species can “persist in place or shift in space”—as Stein and his co-authors put it in a recent paper—or will be unable to adapt at all and will go extinct. On June 30 the FWS issued a new rule that will make it easier to move species outside their historical range—a practice it once forbade except in extreme circumstances.

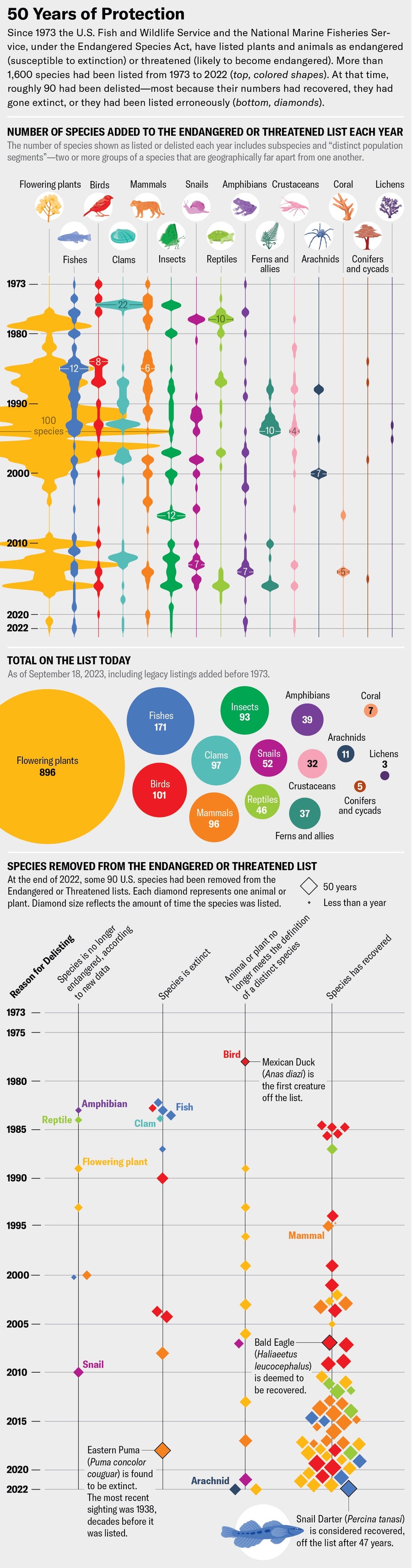

Credit: June Minju Kim ( graphic ); Brown Bird Design ( illustrations ); Sources: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Environmental Conservation Online System; U.S. Federal Endangered and Threatened Species by Calendar Year https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-listings-by-year-totals ( annual data through 2022 ); Listed Species Summary (Boxscore) https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/boxscore ( cumulative data up to September 18, 2023, and annual data for coral ); Delisted Species https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-delisted ( delisted data through 2022 )

Eventually, though, “climate change is going to swamp the ESA,” says J. B. Ruhl, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, who has been writing about the problem for decades. “As more and more species are threatened, I don't know what the agency does with that.” To offer a practical answer, in a 2008 paper he urged the FWS to aggressively identify the species most at risk and not waste resources on ones that seem sure to expire.

Yet when I asked Frazer which urgent issues were commanding his attention right now, his first thought wasn't climate; it was renewable energy. “Renewable energy is going to leave a big footprint on the planet and on our country,” he says, some of it threatening plants and animals if not implemented well. “The Inflation Reduction Act is going to lead to an explosion of more wind and solar across the landscape.

Long before President Joe Biden signed that landmark law, conflicts were proliferating: Desert Tortoise versus solar farms in the Mojave Desert, Golden Eagles versus wind farms in Wyoming, Tiehm's Buckwheat (a little desert flower) versus lithium mining in Nevada. The mine case is a close parallel to that of Snail Darters versus the Tellico Dam. The flower, listed as endangered just last year, grows on only a few acres of mountainside in western Nevada, right where a mining company wants to extract lithium. The Center for Biological Diversity has led the fight to save it. Elsewhere in Nevada people have used the ESA to stop, for the moment, a proposed geothermal plant that might threaten the two-inch Dixie Valley Toad, discovered in 2017 and also declared endangered last year.

Does an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species make sense in such places? In a recent essay entitled “A Time for Triage,” Columbia law professor Michael Gerrard argues that “the environmental community has trade-off denial. We don't recognize that it's too late to preserve everything we consider precious.” In his view, given the urgency of building the infrastructure to fight climate change, we need to be willing to let a species go after we've done our best to save it. Environmental lawyers adept at challenging fossil-fuel projects, using the ESA and other statutes, should consider holding their fire against renewable installations. “Just because you have bullets doesn't mean you shoot them in every direction,” Gerrard says. “You pick your targets.” In the long run, he and others argue, climate change poses a bigger threat to wildlife than wind turbines and solar farms do.