Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Oligopoly

10.1 theory of the oligopoly, why do oligopolies exist.

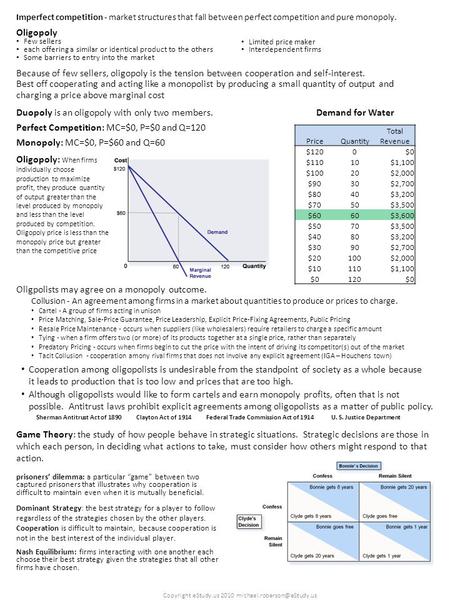

Many purchases that individuals make at the retail level are produced in markets that are neither perfectly competitive, monopolies, nor monopolistically competitive. Rather, they are oligopolies. Oligopoly arises when a small number of large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry. Examples of oligopoly abound and include the auto industry, cable television, and commercial air travel. Oligopolistic firms are like cats in a bag. They can either scratch each other to pieces or cuddle up and get comfortable with one another. If oligopolists compete hard, they may end up acting very much like perfect competitors, driving down costs and leading to zero profits for all. If oligopolists collude with each other, they may effectively act like a monopoly and succeed in pushing up prices and earning consistently high levels of profit. We typically characterize oligopolies by mutual interdependence where various decisions such as output, price, and advertising depend on other firm(s)’ decisions. Analyzing the choices of oligopolistic firms about pricing and quantity produced involves considering the pros and cons of competition versus collusion at a given point in time.

A combination of the barriers to entry that create monopolies and the product differentiation that characterizes monopolistic competition can create the setting for an oligopoly. For example, when a government grants a patent for an invention to one firm, it may create a monopoly. When the government grants patents to, for example, three different pharmaceutical companies that each has its own drug for reducing high blood pressure, those three firms may become an oligopoly.

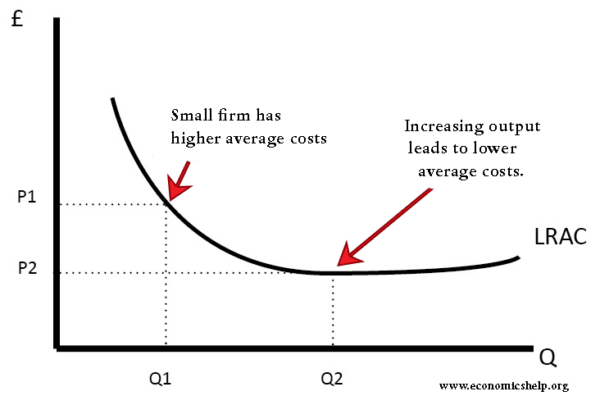

Similarly, a natural monopoly will arise when the quantity demanded in a market is only large enough for a single firm to operate at the minimum of the long-run average cost curve. In such a setting, the market has room for only one firm, because no smaller firm can operate at a low enough average cost to compete, and no larger firm could sell what it produced given the quantity demanded in the market.

Quantity demanded in the market may also be two or three times the quantity needed to produce at the minimum of the average cost curve—which means that the market would have room for only two or three oligopoly firms (and they need not produce differentiated products). Again, smaller firms would have higher average costs and be unable to compete, while additional large firms would produce such a high quantity that they would not be able to sell it at a profitable price. This combination of economies of scale and market demand creates the barrier to entry, which led to the Boeing-Airbus oligopoly (also called a duopoly) for large passenger aircraft.

The product differentiation at the heart of monopolistic competition can also play a role in creating oligopoly. For example, firms may need to reach a certain minimum size before they are able to spend enough on advertising and marketing to create a recognizable brand name. The problem in competing with, say, Coca-Cola or Pepsi is not that producing fizzy drinks is technologically difficult, but rather that creating a brand name and marketing effort to equal Coke or Pepsi is an enormous task.

The existence of oligopolies can lead to the combination of many firms into larger firms. This is discussed next.

Types of Firm Integration

Conglomerate.

From: Wikipedia: Conglomerate (company)

A conglomerate is a combination of multiple business entities operating in entirely different industries under one corporate group , usually involving a parent company and many subsidiaries . Often, a conglomerate is a multi-industry company . Conglomerates are often large and multinational .

Horizontal Integration

From: Wikipedia: Horizontal integration

Horizontal integration is the process of a company increasing production of goods or services at the same part of the supply chain . A company may do this via internal expansion, acquisition or merger . [1] [2] [3]

The process can lead to monopoly if a company captures the vast majority of the market for that product or service. [3]

Horizontal integration contrasts with vertical integration , where companies integrate multiple stages of production of a small number of production units.

Benefits of horizontal integration to both the firm and society may include economies of scale and economies of scope . For the firm, horizontal integration may provide a strengthened presence in the reference market. It may also allow the horizontally integrated firm to engage in monopoly pricing , which is disadvantageous to society as a whole and which may cause regulators to ban or constrain horizontal integration. [5]

An example of horizontal integration in the food industry was the Heinz and Kraft Foods merger. On March 25, 2015, Heinz and Kraft merged into one company, the deal valued at $46 Billion. [8] [9] Both produce processed food for the consumer market.

On November 16, 2015, Marriott International announced that it would purchase Starwood Hotels for $13.6 billion, creating the world’s largest hotel chain once the deal closed. [11] The merger was finalized on September 23, 2016. [12]

AB-Inbev acquisition of SAB Miller for $107 Billion which completed in 2016, is one of the biggest deals of all time. [13]

Vertical Integration

From: Wikipedia: Vertical integration

In microeconomics and management , vertical integration is an arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is owned by that company. Usually each member of the supply chain produces a different product or (market-specific) service, and the products combine to satisfy a common need. It is contrasted with horizontal integration , wherein a company produces several items which are related to one another. Vertical integration has also described management styles that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership, but also into one corporation (as in the 1920s when the Ford River Rouge Complex began making much of its own steel rather than buying it from suppliers).

Vertical integration and expansion is desired because it secures the supplies needed by the firm to produce its product and the market needed to sell the product. Vertical integration and expansion can become undesirable when its actions become anti-competitive and impede free competition in an open marketplace. Vertical integration is one method of avoiding the hold-up problem . A monopoly produced through vertical integration is called a vertical monopoly .

Vertical integration is often closely associated to vertical expansion which, in economics , is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of companies that produce the intermediate goods needed by the business or help market and distribute its product. Such expansion is desired because it secures the supplies needed by the firm to produce its product and the market needed to sell the product. Such expansion can become undesirable when its actions become anti-competitive and impede free competition in an open marketplace.

The result is a more efficient business with lower costs and more profits. On the undesirable side, when vertical expansion leads toward monopolistic control of a product or service then regulative action may be required to rectify anti-competitive behavior. Related to vertical expansion is lateral expansion , which is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of similar firms, in the hope of achieving economies of scale .

Vertical expansion is also known as a vertical acquisition. Vertical expansion or acquisitions can also be used to increase scales and to gain market power. The acquisition of DirecTV by News Corporation is an example of forward vertical expansion or acquisition. DirecTV is a satellite TV company through which News Corporation can distribute more of its media content: news, movies and television shows. The acquisition of NBC by Comcast is an example of backward vertical integration. For example, in the United States, protecting the public from communications monopolies that can be built in this way is one of the missions of the Federal Communications Commission .

One of the earliest, largest and most famous examples of vertical integration was the Carnegie Steel company. The company controlled not only the mills where the steel was made, but also the mines where the iron ore was extracted, the coal mines that supplied the coal , the ships that transported the iron ore and the railroads that transported the coal to the factory, the coke ovens where the coal was cooked, etc. The company focused heavily on developing talent internally from the bottom up, rather than importing it from other companies. Later, Carnegie established an institute of higher learning to teach the steel processes to the next generation.

Oil companies , both multinational (such as ExxonMobil , Royal Dutch Shell , ConocoPhillips or BP ) and national (e.g., Petronas ) often adopt a vertically integrated structure, meaning that they are active along the entire supply chain from locating deposits , drilling and extracting crude oil , transporting it around the world, refining it into petroleum products such as petrol/gasoline , to distributing the fuel to company-owned retail stations, for sale to consumers.

Lateral Integration

Lateral expansion , in economics , is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of similar companies, in the hope of achieving economies of scale or economies of scope . Unchecked lateral expansion can lead to powerful conglomerates or monopolies .

Lateral integration differs from horizontal integration as the integration is not exact. For example, one of the examples of horizontal integration was one hotel chain buying another. This did not enhance the company’s product offerings other than having more hotel options.

On the other hand, Parker Hannifin acquired Lord Corporation. While the two companies make similar types of products, their product offerings were distinct. There was not much overlap with the types of products offered. Instead, Parker Hannifin was not able to provide a far greater product offering in the given sectors.

The Strength of an Oligopoly

From: Wikipedia: Concentration ratio

The most common concentration ratios are the CR 4 and the CR 8 , which means the market share of the four and the eight largest firms. Concentration ratios are usually used to show the extent of market control of the largest firms in the industry and to illustrate the degree to which an industry is oligopolistic . [1]

N-firm concentration ratio is a common measure of market structure and shows the combined market share of the N largest firms in the market. For example, the 5-firm concentration ratio in the UK pesticide industry is 0.75, which indicates that the combined market share of the five largest pesticide sellers in the UK is about 75%. N-firm concentration ratio does not reflect changes in the size of the largest firms.

Concentration ratios range from 0 to 100 percent. The levels reach from no, low or medium to high to “total” concentration

Perfect competition

If there are N firms in an industry and we are looking at the top n of them, equal market share for all of them means that CR n = n/N . All other possible values will be greater than this.

No concentration

If CR n is close to 0%, (which is only possible for quite a large number of firms in the industry N ) this means perfect competition or at the very least monopolistic competition . If for example CR 4 =0 %, the four largest firm in the industry would not have any significant market share.

Low concentration

0% to 40%. [5] This category ranges from perfect competition to an oligopoly.

Medium concentration

40% to 70%. [5] An industry in this range is likely an oligopoly.

High concentration

70% to 100%. [5] This category ranges from an oligopoly to monopoly.

Total concentration

100% means an extremely concentrated oligopoly . If for example CR 1 = 100%, there is a monopoly .

10.2 Game theory

Game theory basics, dominant versus non-dominant strategies.

From: Wikipedia: Cooperative game theory

In game theory , a cooperative game (or coalitional game ) is a game with competition between groups of players (“coalitions”) due to the possibility of external enforcement of cooperative behavior (e.g. through contract law ). Those are opposed to non-cooperative games in which there is either no possibility to forge alliances or all agreements need to be self-enforcing (e.g. through credible threats ). [1]

Cooperative games are often analysed through the framework of cooperative game theory, which focuses on predicting which coalitions will form, the joint actions that groups take and the resulting collective payoffs. It is opposed to the traditional non-cooperative game theory which focuses on predicting individual players’ actions and payoffs and analyzing Nash equilibria . [2] [3]

Cooperative game theory provides a high-level approach as it only describes the structure, strategies and payoffs of coalitions, whereas non-cooperative game theory also looks at how bargaining procedures will affect the distribution of payoffs within each coalition. As non-cooperative game theory is more general, cooperative games can be analyzed through the approach of non-cooperative game theory (the converse does not hold) provided that sufficient assumptions are made to encompass all the possible strategies available to players due to the possibility of external enforcement of cooperation. While it would thus be possible to have all games expressed under a non-cooperative framework, in many instances insufficient information is available to accurately model the formal procedures available to the players during the strategic bargaining process, or the resulting model would be of too high complexity to offer a practical tool in the real world. In such cases, cooperative game theory provides a simplified approach that allows the analysis of the game at large without having to make any assumption about bargaining powers.

Types of Strategies

General strategy.

This is simply any rule that a player uses. These strategies can be “good” or “bad.” For example, if you have to choose heads or tails for a coinflip, you may use the strategy “tails never fails” and always pick tails even though there is no advantage to this strategy. Additionally, when playing the game of Blackjack, you may have a rule that you always hit when you have a score of 20. If you do not know how to play Blackjack, I will simply state that this is generally a very, very bad idea! Even though it is a poor strategy, it is still a strategy nonetheless.

Dominant Strategy

From: Wikipedia: Strategic dominance

In game theory , strategic dominance (commonly called simply dominance ) occurs when one strategy is better than another strategy for one player, no matter how that player’s opponents may play. Many simple games can be solved using dominance.

Nash Equilibrium

From: Wikipedia: Nash equilibrium

In terms of game theory, if each player has chosen a strategy, and no player can benefit by changing strategies while the other players keep theirs unchanged, then the current set of strategy choices and their corresponding payoffs constitutes a Nash equilibrium.

Stated simply, Alice and Bob are in Nash equilibrium if Alice is making the best decision she can, taking into account Bob’s decision while his decision remains unchanged, and Bob is making the best decision he can, taking into account Alice’s decision while her decision remains unchanged. Likewise, a group of players are in Nash equilibrium if each one is making the best decision possible, taking into account the decisions of the others in the game as long as the other parties’ decisions remain unchanged.

Informally, a strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium if no player can do better by unilaterally changing his or her strategy. To see what this means, imagine that each player is told the strategies of the others. Suppose then that each player asks themselves: “Knowing the strategies of the other players, and treating the strategies of the other players as set in stone, can I benefit by changing my strategy?”

If any player could answer “Yes”, then that set of strategies is not a Nash equilibrium. But if every player prefers not to switch (or is indifferent between switching and not) then the strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium. Thus, each strategy in a Nash equilibrium is a best response to all other strategies in that equilibrium. [13]

The Nash equilibrium may sometimes appear non-rational in a third-person perspective. This is because a Nash equilibrium is not necessarily Pareto optimal . [Note: We do not talk about Pareto optimality in this class, but you can think of it as a best-case for everyone situation.]

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

From: Wikipedia: Prisoner’s dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is a standard example of a game analyzed in game theory that shows why two completely rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interests to do so. It was originally framed by Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher while working at RAND in 1950. Albert W. Tucker formalized the game with prison sentence rewards and named it “prisoner’s dilemma”, [1] presenting it as follows:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge, but they have enough to convict both on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is: If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves two years in prison If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa) If A and B both remain silent, both of them will serve only one year in prison (on the lesser charge).

It is implied that the prisoners will have no opportunity to reward or punish their partner other than the prison sentences they get and that their decision will not affect their reputation in the future. Because betraying a partner offers a greater reward than cooperating with them, all purely rational self-interested prisoners will betray the other, meaning the only possible outcome for two purely rational prisoners is for them to betray each other. [2] The interesting part of this result is that pursuing individual reward logically leads both of the prisoners to betray when they would get a better individual reward if they both kept silent. In reality, humans display a systemic bias towards cooperative behavior in this and similar games despite what is predicted by simple models of “rational” self-interested action. [3] [4] [5] [6] This bias towards cooperation has been known since the test was first conducted at RAND; the secretaries involved trusted each other and worked together for the best common outcome. [7]

The prisoner’s dilemma game can be used as a model for many real world situations involving cooperative behavior. In casual usage, the label “prisoner’s dilemma” may be applied to situations not strictly matching the formal criteria of the classic or iterative games: for instance, those in which two entities could gain important benefits from cooperating or suffer from the failure to do so, but find it difficult or expensive—not necessarily impossible—to coordinate their activities.

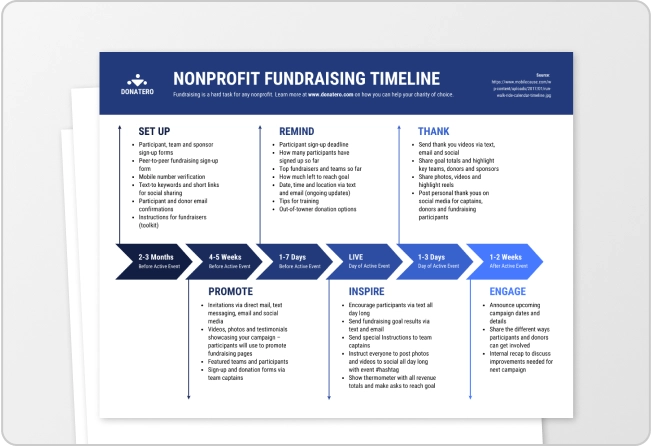

Game Tables

In the game above, we need some way to display all of the information in a condensed format. To accomplish this, we use a game table. For the sake of displaying the game tables in an accessible manner, I will use the following format:

You will see that the information is exactly the same as the information presented. For example, if A stays silent, but B betrays, we would be in the top, right payout cell (which is -3,0).

The next question is what the “best” outcome is. We will examine that but going back to the two strategies discussed earlier.

Solving Prisoner’s Dilemma with Dominant Strategy

The iterated elimination (or deletion) of dominated strategies (also denominated as IESDS or IDSDS) is one common technique for solving games that involves iteratively removing dominated strategies. In the first step, at most one dominated strategy is removed from the strategy space of each of the players since no rational player would ever play these strategies. This results in a new, smaller game. Some strategies—that were not dominated before—may be dominated in the smaller game. The first step is repeated, creating a new even smaller game, and so on. The process stops when no dominated strategy is found for any player. This process is valid since it is assumed that rationality among players is common knowledge , that is, each player knows that the rest of the players are rational, and each player knows that the rest of the players know that he knows that the rest of the players are rational, and so on ad infinitum (see Aumann, 1976).

There are two versions of this process. One version involves only eliminating strictly dominated strategies. If, after completing this process, there is only one strategy for each player remaining, that strategy set is the unique Nash equilibrium [2] . This will be discussed next.

You can use the following set of steps:

- Pick one person (it doesn’t matter).

- If their opponent picks choice A, what will your person pick?

- If their opponent picks choice B, what will your person pick?

- If you choose the same thing for both of your opponent’s choices, then that is the dominant strategy. We say that choice strictly dominates the other choice and you can cross off the strictly dominated strategy.

- Repeat for the opponent (this should be easier).

- If the choices are different, there is no dominant strategy

Let us return to the prisoner’s dilemma game table. Let us act as player A and decide what player A would do in a variety of situations.

If player B stays silent, what should we do as player A? If we stay silent, then we would lose 1 (meaning one year in prison.) If we betray, we earn 0. In this case we should betray as no prison is better than one year in prison.

If player B betrays, what should we do as player A? If we stay silent, then we get three years in prison. If we betray, we get two years in prison. In this case, we should betray as two years in prison is better than 3 years in prison.

Therefore, the dominant strategy for player A is to betray. This is because regardless of what player B chooses to do, player A’s best choice is to betray. We can therefore eliminate “A-stay silent” since player A will not stay silent.

We can now move to player B to see if there is a dominant strategy for player B. It should be noted that, in theory, there does not need to be, but with our games there will be (if player A has one.) So, now let us play our modified game as player B.

If player A chooses to stay silent – STOP! – what did we just discuss? Player A will not choose to stay silent, so we do not need to worry about this. So, if player A chooses to betray, what should we do as player B? If we stay silent, we get three years in prison whereas we only get two years in prison if we betray. Therefore, player B should betray.

Thus, the dominant strategy for this game is (A,B)=(Betray,Betray).

There are additional exercises in the companion. Each player can have either 0 or 1 dominant strategies.

Solving Prisoner’s Dilemma with Nash Equilibrium

As mentioned earlier, we are looking for a stable solution. That is, a situation where neither player has an incentive to change their choice based on the other player’s choice. To find the Nash Equilibrium, you can follow these steps:

- Choose a player (again, it doesn’t matter which).

- Pick a choice (it doesn’t matter which).

- Based on your choice, what will the opponent pick?

- Based on what your opponent picks, what would you pick?

- If it is the same as your original choice, it is a Nash Equilibrium. If not, it is not a Nash Equilibrium.

- Repeat for the other choice(s).

So, let us return to our game. Without loss of generality, let us play as player A. It should be noted that playing as player B will yield the same exact results.

As player A, let us begin by staying silent. What will player B do? Player B can either stay silent (one year in prison) or betray (0 years in prison.) Player B will betray. Now, since we know that player B will betray, what should player A do? If player A stays silent, we get 3 years in prison but if we betray we only get two years in prison. Thus, we, as player A, should betray. But this is different from where we started, thus we do not have a Nash Equilibrium. The chain for this event is:

A: Silent >> B: Betray >> A: Betray — A has changed their choice, not a Nash Equilibrium.

Now, as player A, let us start by betraying. If we betray, player B can either stay silent (3 years in prison) or betray (2 years in prison.) Thus, player B will betray. When player B betrays, what should we do? We can either stay silent (3 years in prison) or betray (2 years in prison.) Thus, we betray. This is exactly where we started, thus, we have a Nash Equilibrium. In fact, we could continue to do this forever and the chain would stay exactly the same. The chain for this scenario is:

A: Betray >> B: Betray >> A: Betray — A has kept their choice the same, so A:Betray, B:Betray is a Nash Equilibrium.

10.3 Cartels and Collusion

Game theory and oligopolies.

So what was the foray into game theory for? It allows us to explore how individual firms in oligopolies want to act. Let us consider two firms that each produce widgets. They can each choose to either produce at a high price level or low price level. Remember, for a firm to produce more (and sell it) they have to charge less. And if a firm restricts its output, they can charge more. Recall, a monopolist is able to make an additional profit because it restricts output and charges more whereas a firm in a perfectly competitive market may sell more, but at a lower price, and therefore earns a lower profit.

Let us use the following game table showing each firms’ profits:

First, let us step back and just look at the game table. What should each firm do? It seems like each firm should just set their price high. But, is that what will happen?

Let us look for the dominant strategy. As player A, if player B chooses to set a high price, we should should charge a low price (70>65). If player B chooses to set a low price, we should choose low price (40>20). Therefore, as player A, we should always choose to set our price low. The same applies for player B as setting their price low is always better than setting their price high regardless of what player A does (100>90 and 60>40).

So, even though it “makes sense” for both firms to set their prices high, both firms will set their prices low. The same would apply to the Nash Equilibrium.

What does this mean in the real world? If the two firms could cooperate and fully trust each other, they would each set their prices high. This is what we call collusion and will be discussed shortly. But, whether it is due to laws or just human nature, firms are never able to collude too long. Eventually, firms will move to the dominant strategy. While firms would like to keep their prices high, there are typically forces that prevent this.

From: Wikipedia: OPEC

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries ( OPEC , / ˈ oʊ p ɛ k / OH-pek ) is an intergovernmental organization of 14 nations, founded in 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members ( Iran , Iraq , Kuwait , Saudi Arabia , and Venezuela ), and headquartered since 1965 in Vienna, Austria . As of September 2018, the then 14 member countries accounted for an estimated 44 percent of global oil production and 81.5 percent of the world’s “proven” oil reserves , giving OPEC a major influence on global oil prices that were previously determined by the so called “ Seven Sisters ” grouping of multinational oil companies.

The stated mission of the organization is to “coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its member countries and ensure the stabilization of oil markets, in order to secure an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers, and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry.” [4] The organization is also a significant provider of information about the international oil market. The current OPEC members are the following: Algeria , Angola , Ecuador , Equatorial Guinea , Gabon , Iran , Iraq , Kuwait , Libya , Nigeria , the Republic of the Congo , Saudi Arabia (the de facto leader), United Arab Emirates , and Venezuela . Indonesia and Qatar are former members.

The formation of OPEC marked a turning point toward national sovereignty over natural resources , and OPEC decisions have come to play a prominent role in the global oil market and international relations . The effect can be particularly strong when wars or civil disorders lead to extended interruptions in supply. In the 1970s, restrictions in oil production led to a dramatic rise in oil prices and in the revenue and wealth of OPEC, with long-lasting and far-reaching consequences for the global economy . In the 1980s, OPEC began setting production targets for its member nations; generally, when the targets are reduced, oil prices increase. This has occurred most recently from the organization’s 2008 and 2016 decisions to trim oversupply.

Economists often cite OPEC as a textbook example of a cartel that cooperates to reduce market competition , but one whose consultations are protected by the doctrine of state immunity under international law . In December 2014, “OPEC and the oil men” ranked as #3 on Lloyd’s list of “the top 100 most influential people in the shipping industry”. [5] However, the influence of OPEC on international trade is periodically challenged by the expansion of non-OPEC energy sources, and by the recurring temptation for individual OPEC countries to exceed production targets and pursue conflicting self-interests.

At various times, OPEC members have displayed apparent anti-competitive cartel behavior through the organization’s agreements about oil production and price levels. [26] In fact, economists often cite OPEC as a textbook example of a cartel that cooperates to reduce market competition, as in this definition from OECD ‘s Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law : [1]

International commodity agreements covering products such as coffee, sugar, tin and more recently oil (OPEC: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) are examples of international cartels which have publicly entailed agreements between different national governments.

OPEC members strongly prefer to describe their organization as a modest force for market stabilization, rather than a powerful anti-competitive cartel. In its defense, the organization was founded as a counterweight against the previous “ Seven Sisters ” cartel of multinational oil companies, and non-OPEC energy suppliers have maintained enough market share for a substantial degree of worldwide competition. [27] Moreover, because of an economic “ prisoner’s dilemma ” that encourages each member nation individually to discount its price and exceed its production quota, [28] widespread cheating within OPEC often erodes its ability to influence global oil prices through collective action . [29] [30]

OPEC has not been involved in any disputes related to the competition rules of the World Trade Organization , even though the objectives, actions, and principles of the two organizations diverge considerably. [31] A key US District Court decision held that OPEC consultations are protected as “governmental” acts of state by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act , and are therefore beyond the legal reach of US competition law governing “commercial” acts. [32] [33] Despite popular sentiment against OPEC, legislative proposals to limit the organization’s sovereign immunity, such as the NOPEC Act, have so far been unsuccessful. [34]

Cartel Theory

From: Wikipedia: Cartel

A cartel is a group of apparently independent producers whose goal is to increase their collective profits by means of price fixing , limiting supply, or other restrictive practices . Cartels typically control selling prices, but some are organized to force down the prices of purchased inputs. Antitrust laws attempt to deter or forbid cartels. A single entity that holds a monopoly by this definition cannot be a cartel, though it may be guilty of abusing said monopoly in other ways. Cartels usually arise in oligopolies —industries with a small number of sellers—and usually involve homogeneous products .

A survey of hundreds of published economic studies and legal decisions of antitrust authorities found that the median price increase achieved by cartels in the last 200 years is about 23 percent. [4] Private international cartels (those with participants from two or more nations) had an average price increase of 28 percent, whereas domestic cartels averaged 18 percent. Less than 10 percent of all cartels in the sample failed to raise market prices.

In general, cartel agreements are economically unstable in that there is an incentive for members to cheat by selling at below the agreed price or selling more than the production quotas set by the cartel (see also game theory ). This has caused many cartels that attempt to set product prices to be unsuccessful in the long term . Empirical studies of 20th-century cartels have determined that the mean duration of discovered cartels is from 5 to 8 years [5] . However, once a cartel is broken, the incentives to form the cartel return and the cartel may be re-formed. Publicly known cartels that do not follow this cycle include, by some accounts, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Price fixing is often practiced internationally. When the agreement to control price is sanctioned by a multilateral treaty or protected by national sovereignty, no antitrust actions may be initiated [6] . Examples of such price fixing include oil, whose price is partly controlled by the supply by OPEC countries, and international airline tickets, which have prices fixed by agreement with the IATA , a practice for which there is a specific exception in antitrust law.

Prior to World War II (except in the United States), members of cartels could sign contracts that were enforceable in courts of law. There were even instances where cartels are encouraged by states. For example, during the period before 1945, cartels were tolerated in Europe and were promoted as a business practice in German-speaking countries. [7] This was the norm due to the accepted benefits, which even the U.S. Supreme court has noted. In the case, the U.S. v. National Lead Co. et al. , it cited the testimony of individuals, who cited that a cartel, in its protean form, is “a combination of producers for the purpose of regulating production and, frequently, prices, and an association by agreement of companies or sections of companies having common interests so as to prevent extreme or unfair competition.” [8]

Today, however, price fixing by private entities is illegal under the antitrust laws of more than 140 countries. Examples of prosecuted international cartels are lysine , citric acid , graphite electrodes , and bulk vitamins . [9] This is highlighted in countries with market economies wherein price-fixing and the concept of cartels are considered inimical to free and fair competition, which is considered the backbone of political democracy. [10] The current condition makes it increasingly difficult for cartels to maintain sustainable operations. Even if international cartels might be out of reach for the regulatory authorities, they will still have to contend with the fact that their activities in domestic markets will be affected. [11]

For a cartel to be successful, some or all of the following conditions are necessary:

- A small number of firms.

- Products are relatively undifferentiated from one firm to the next.

- Prices are easily observable.

- Prices show little variation over time.

Introduction to Microeconomics Copyright © 2019 by J. Zachary Klingensmith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

11 templates

8 templates

25 templates

9 templates

memorial day

12 templates

39 templates

What Is an Oligopoly?

What is an oligopoly presentation, premium google slides theme and powerpoint template.

Understanding complex economic concepts such as oligopolies is made easy with this fully customizable Google Slides and PowerPoint template. Rendered in calming shades of blue and a minimalist design, this template focuses on elucidating oligopolies, their characteristics, and how they compare to other market structures. The template also boasts a variety of graphs and infographics, assisting learners, educators, and professionals in presenting and digesting this potentially complex topic. Prepare to enhance your audience’s economic comprehension!

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 35 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

What are the benefits of having a Premium account?

What Premium plans do you have?

What can I do to have unlimited downloads?

Don’t want to attribute Slidesgo?

Gain access to over 24200 templates & presentations with premium from 1.67€/month.

Are you already Premium? Log in

Related posts on our blog

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Market Structure: Oligopoly

Published by Sheila Hawkins Modified over 8 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Market Structure: Oligopoly"— Presentation transcript:

Introduction to Oligopoly. Recall: Oligopoly ▫An industry with only a few sellers. ▫Also characterized by interdependence A relationship in which the.

OLIGOPOLY Chapter 16 1.

16 Oligopoly.

Copyright©2004 South-Western 16 Oligopoly. Copyright © 2004 South-Western BETWEEN MONOPOLY AND PERFECT COMPETITION Imperfect competition refers to those.

Copyright©2004 South-Western 16 Oligopoly. Copyright © 2004 South-Western What’s Important in Chapter 16 Four Types of Market Structures Strategic Interdependence.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western CHAPTER 16 OLIGOPOLY.

Part 8 Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

15 chapter: >> Oligopoly Krugman/Wells Economics

Game Theory!.

Introduction to Oligopoly

Game Theory. Games Oligopolist Play ▫Each oligopolist realizes both that its profit depends on what its competitor does and that its competitor’s profit.

Oligopoly Chapter 25.

Economic Analysis for Business Session XIII: Oligopoly Instructor Sandeep Basnyat

ECON 201 OLIGOPOLIES & GAME THEORY 1. FIGURE 12.4 DUOPOLY EQUILIBRIUM IN A CENTRALIZED CARTEL 2.

Oligopoly Fun and games. Oligopoly An oligopolist is one of a small number of producers in an industry. The industry is an oligopoly. All oligopolists.

Oligopoly Most firms are part of oligopoly or monopolistic competition, with few monopolies or perfect competition. These two market structures are called.

Oligopoly. Definition Industry with only a few sellers Industry with only a few sellers A firm in this industry is called an oligopolistic A firm in this.

Oligopoly Few sellers each offering a similar or identical product to the others Some barriers to entry into the market Because of few sellers, oligopoly.

Principles of Microeconomics: Econ102. Monopolistic Competition: A market structure in which barriers to entry are low, and many firms compete by selling.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

10.2 Oligopoly

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why and how oligopolies exist

- Contrast collusion and competition

- Interpret and analyze the prisoner’s dilemma diagram

- Evaluate the tradeoffs of imperfect competition

Many purchases that individuals make at the retail level are produced in markets that are neither perfectly competitive, monopolies, nor monopolistically competitive. Rather, they are oligopolies. Oligopoly arises when a small number of large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry. Examples of oligopoly abound and include the auto industry, cable television, and commercial air travel. Oligopolistic firms are like cats in a bag. They can either scratch each other to pieces or cuddle up and get comfortable with one another. If oligopolists compete hard, they may end up acting very much like perfect competitors, driving down costs and leading to zero profits for all. If oligopolists collude with each other, they may effectively act like a monopoly and succeed in pushing up prices and earning consistently high levels of profit. We typically characterize oligopolies by mutual interdependence where various decisions such as output, price, and advertising depend on other firm(s)' decisions. Analyzing the choices of oligopolistic firms about pricing and quantity produced involves considering the pros and cons of competition versus collusion at a given point in time.

Why Do Oligopolies Exist?

A combination of the barriers to entry that create monopolies and the product differentiation that characterizes monopolistic competition can create the setting for an oligopoly. For example, when a government grants a patent for an invention to one firm, it may create a monopoly. When the government grants patents to, for example, three different pharmaceutical companies that each has its own drug for reducing high blood pressure, those three firms may become an oligopoly.

Similarly, a natural monopoly will arise when the quantity demanded in a market is only large enough for a single firm to operate at the minimum of the long-run average cost curve. In such a setting, the market has room for only one firm, because no smaller firm can operate at a low enough average cost to compete, and no larger firm could sell what it produced given the quantity demanded in the market.

Quantity demanded in the market may also be two or three times the quantity needed to produce at the minimum of the average cost curve—which means that the market would have room for only two or three oligopoly firms (and they need not produce differentiated products). Again, smaller firms would have higher average costs and be unable to compete, while additional large firms would produce such a high quantity that they would not be able to sell it at a profitable price. This combination of economies of scale and market demand creates the barrier to entry, which led to the Boeing-Airbus oligopoly (also called a duopoly) for large passenger aircraft.

The product differentiation at the heart of monopolistic competition can also play a role in creating oligopoly. For example, firms may need to reach a certain minimum size before they are able to spend enough on advertising and marketing to create a recognizable brand name. The problem in competing with, say, Coca-Cola or Pepsi is not that producing fizzy drinks is technologically difficult, but rather that creating a brand name and marketing effort to equal Coke or Pepsi is an enormous task.

Collusion or Competition?

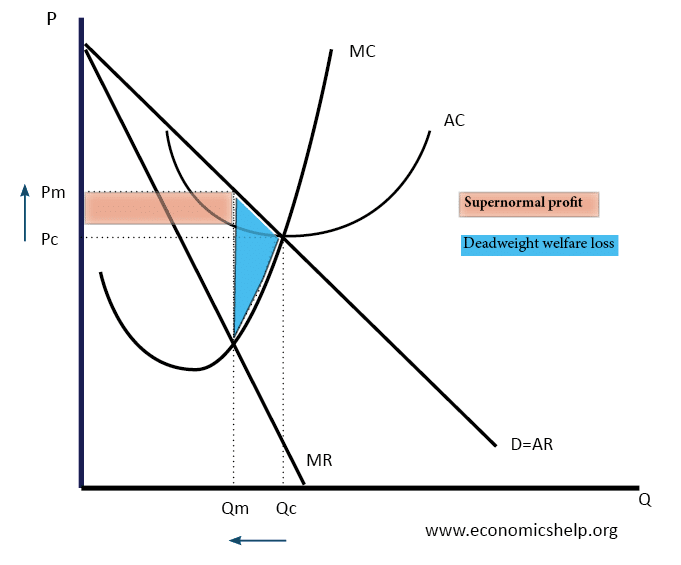

When oligopoly firms in a certain market decide what quantity to produce and what price to charge, they face a temptation to act as if they were a monopoly. By acting together, oligopolistic firms can hold down industry output, charge a higher price, and divide the profit among themselves. When firms act together in this way to reduce output and keep prices high, it is called collusion . A group of firms that have a formal agreement to collude to produce the monopoly output and sell at the monopoly price is called a cartel . See the following Clear It Up feature for a more in-depth analysis of the difference between the two.

Clear It Up

Collusion versus cartels: how to differentiate.

In the United States, as well as many other countries, it is illegal for firms to collude since collusion is anti-competitive behavior, which is a violation of antitrust law. Both the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission have responsibilities for preventing collusion in the United States.

The problem of enforcement is finding hard evidence of collusion. Cartels are formal agreements to collude. Because cartel agreements provide evidence of collusion, they are rare in the United States. Instead, most collusion is tacit, where firms implicitly reach an understanding that competition is bad for profits.

Economists have understood for a long time the desire of businesses to avoid competing so that they can instead raise the prices that they charge and earn higher profits. Adam Smith wrote in Wealth of Nations in 1776: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Even when oligopolists recognize that they would benefit as a group by acting like a monopoly, each individual oligopoly faces a private temptation to produce just a slightly higher quantity and earn slightly higher profit—while still counting on the other oligopolists to hold down their production and keep prices high. If at least some oligopolists give in to this temptation and start producing more, then the market price will fall. A small handful of oligopoly firms may end up competing so fiercely that they all find themselves earning zero economic profits—as if they were perfect competitors.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Because of the complexity of oligopoly, which is the result of mutual interdependence among firms, there is no single, generally-accepted theory of how oligopolies behave, in the same way that we have theories for all the other market structures. Instead, economists use game theory , a branch of mathematics that analyzes situations in which players must make decisions and then receive payoffs based on what other players decide to do. Game theory has found widespread applications in the social sciences, as well as in business, law, and military strategy.

The prisoner’s dilemma is a scenario in which the gains from cooperation are larger than the rewards from pursuing self-interest. It applies well to oligopoly. (Note that the term "prisoner" is not typically an accurate term for someone who has recently been arrested, but we will use the term here, since this scenario is widely used and referenced in economic, business, and social contexts.) The story behind the prisoner’s dilemma goes like this:

Two co-conspirators are arrested. When they are taken to the police station, they refuse to say anything and are put in separate interrogation rooms. Eventually, a police officer enters the room where Prisoner A is being held and says: “You know what? Your partner in the other room is confessing. Your partner is going to get a light prison sentence of just one year, and because you’re remaining silent, the judge is going to stick you with eight years in prison. Why don’t you get smart? If you confess, too, we’ll cut your jail time down to five years, and your partner will get five years, also.” Over in the next room, another police officer is giving exactly the same speech to Prisoner B. What the police officers do not say is that if both prisoners remain silent, the evidence against them is not especially strong, and the prisoners will end up with only two years in jail each.

The game theory situation facing the two prisoners is in Table 10.2 . To understand the dilemma, first consider the choices from Prisoner A’s point of view. If A believes that B will confess, then A should confess, too, so as to not get stuck with the eight years in prison. However, if A believes that B will not confess, then A will be tempted to act selfishly and confess, so as to serve only one year. The key point is that A has an incentive to confess regardless of what choice B makes! B faces the same set of choices, and thus will have an incentive to confess regardless of what choice A makes. To confess is called the dominant strategy. It is the strategy an individual (or firm) will pursue regardless of the other individual’s (or firm’s) decision. The result is that if prisoners pursue their own self-interest, both are likely to confess, and end up being sentenced to a total of 10 years of jail time between them.

The game is called a dilemma because if the two prisoners had cooperated by both remaining silent, they would only have been incarcerated for two years each, for a total of four years between them. If the two prisoners can work out some way of cooperating so that neither one will confess, they will both be better off than if they each follow their own individual self-interest, which in this case leads straight into longer terms.

The Oligopoly Version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma

The members of an oligopoly can face a prisoner’s dilemma, also. If each of the oligopolists cooperates in holding down output, then high monopoly profits are possible. Each oligopolist, however, must worry that while it is holding down output, other firms are taking advantage of the high price by raising output and earning higher profits. Table 10.3 shows the prisoner’s dilemma for a two-firm oligopoly—known as a duopoly . If Firms A and B both agree to hold down output, they are acting together as a monopoly and will each earn $1,000 in profits. However, both firms’ dominant strategy is to increase output, in which case each will earn $400 in profits.

Can the two firms trust each other? Consider the situation of Firm A:

- If A thinks that B will cheat on their agreement and increase output, then A will increase output, too, because for A the profit of $400 when both firms increase output (the bottom right-hand choice in Table 10.3 ) is better than a profit of only $200 if A keeps output low and B raises output (the upper right-hand choice in the table).

- If A thinks that B will cooperate by holding down output, then A may seize the opportunity to earn higher profits by raising output. After all, if B is going to hold down output, then A can earn $1,500 in profits by expanding output (the bottom left-hand choice in the table) compared with only $1,000 by holding down output as well (the upper left-hand choice in the table).

Thus, firm A will reason that it makes sense to expand output if B holds down output and that it also makes sense to expand output if B raises output. Again, B faces a parallel set of decisions that will lead B also to expand output.

The result of this prisoner’s dilemma is often that even though A and B could make the highest combined profits by cooperating in producing a lower level of output and acting like a monopolist, the two firms may well end up in a situation where they each increase output and earn only $400 each in profits . The following Clear It Up feature discusses one cartel scandal in particular.

What is the Lysine cartel?

Lysine, a $600 million-a-year industry, is an amino acid that farmers use as a feed additive to ensure the proper growth of swine and poultry. The primary U.S. producer of lysine is Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), but several other large European and Japanese firms are also in this market. For a time in the first half of the 1990s, the world’s major lysine producers met together in hotel conference rooms and decided exactly how much each firm would sell and what it would charge. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), however, had learned of the cartel and placed wire taps on a number of their phone calls and meetings.

From FBI surveillance tapes, following is a comment that Terry Wilson, president of the corn processing division at ADM, made to the other lysine producers at a 1994 meeting in Mona, Hawaii:

I wanna go back and I wanna say something very simple. If we’re going to trust each other, okay, and if I’m assured that I’m gonna get 67,000 tons by the year’s end, we’re gonna sell it at the prices we agreed to . . . The only thing we need to talk about there because we are gonna get manipulated by these [expletive] buyers—they can be smarter than us if we let them be smarter. . . . They [the customers] are not your friend. They are not my friend. And we gotta have ‘em, but they are not my friends. You are my friend. I wanna be closer to you than I am to any customer. Cause you can make us ... money. ... And all I wanna tell you again is let’s—let’s put the prices on the board. Let’s all agree that’s what we’re gonna do and then walk out of here and do it.

The price of lysine doubled while the cartel was in effect. Confronted by the FBI tapes, Archer Daniels Midland pled guilty in 1996 and paid a fine of $100 million. A number of top executives, both at ADM and other firms, later paid fines of up to $350,000 and were sentenced to 24–30 months in prison.

In another one of the FBI recordings, the president of Archer Daniels Midland told an executive from another competing firm that ADM had a slogan that, in his words, had “penetrated the whole company.” The company president stated the slogan this way: “Our competitors are our friends. Our customers are the enemy.” That slogan could stand as the motto of cartels everywhere.

How to Enforce Cooperation

How can parties who find themselves in a prisoner’s dilemma situation avoid the undesired outcome and cooperate with each other? The way out of a prisoner’s dilemma is to find a way to penalize those who do not cooperate.

Perhaps the easiest approach for colluding oligopolists, as you might imagine, would be to sign a contract with each other that they will hold output low and keep prices high. If a group of U.S. companies signed such a contract, however, it would be illegal. Certain international organizations, like the nations that are members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) , have signed international agreements to act like a monopoly, hold down output, and keep prices high so that all of the countries can make high profits from oil exports. Such agreements, however, because they fall in a gray area of international law, are not legally enforceable. If Nigeria, for example, decides to start cutting prices and selling more oil, Saudi Arabia cannot sue Nigeria in court and force it to stop.

Visit the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries website and learn more about its history and how it defines itself.

Because oligopolists cannot sign a legally enforceable contract to act like a monopoly, the firms may instead keep close tabs on what other firms are producing and charging. Alternatively, oligopolists may choose to act in a way that generates pressure on each firm to stick to its agreed quantity of output.

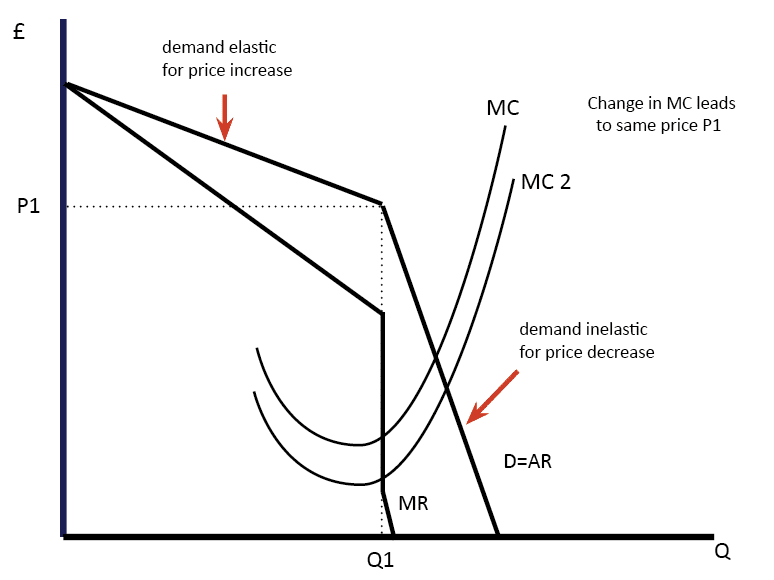

One example of the pressure these firms can exert on one another is the kinked demand curve , in which competing oligopoly firms commit to match price cuts, but not price increases. Figure 10.5 shows this situation. Say that an oligopoly airline has agreed with the rest of a cartel to provide a quantity of 10,000 seats on the New York to Los Angeles route, at a price of $500. This choice defines the kink in the firm’s perceived demand curve. The reason that the firm faces a kink in its demand curve is because of how the other oligopolists react to changes in the firm’s price. If the oligopoly decides to produce more and cut its price, the other members of the cartel will immediately match any price cuts—and therefore, a lower price brings very little increase in quantity sold.

If one firm cuts its price to $300, it will be able to sell only 11,000 seats. However, if the airline seeks to raise prices, the other oligopolists will not raise their prices, and so the firm that raised prices will lose a considerable share of sales. For example, if the firm raises its price to $550, its sales drop to 5,000 seats sold. Thus, if oligopolists always match price cuts by other firms in the cartel, but do not match price increases, then none of the oligopolists will have a strong incentive to change prices, since the potential gains are minimal. This strategy can work like a silent form of cooperation, in which the cartel successfully manages to hold down output, increase price , and share a monopoly level of profits even without any legally enforceable agreement.

Many real-world oligopolies, prodded by economic changes, legal and political pressures, and the egos of their top executives, go through episodes of cooperation and competition. If oligopolies could sustain cooperation with each other on output and pricing, they could earn profits as if they were a single monopoly. However, each firm in an oligopoly has an incentive to produce more and grab a bigger share of the overall market; when firms start behaving in this way, the market outcome in terms of prices and quantity can be similar to that of a highly competitive market.

Tradeoffs of Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic competition is probably the single most common market structure in the U.S. economy. It provides powerful incentives for innovation, as firms seek to earn profits in the short run, while entry assures that firms do not earn economic profits in the long run. However, monopolistically competitive firms do not produce at the lowest point on their average cost curves. In addition, the endless search to impress consumers through product differentiation may lead to excessive social expenses on advertising and marketing.

Oligopoly is probably the second most common market structure. When oligopolies result from patented innovations or from taking advantage of economies of scale to produce at low average cost, they may provide considerable benefit to consumers. Oligopolies are often buffered by significant barriers to entry, which enable the oligopolists to earn sustained profits over long periods of time. Oligopolists also do not typically produce at the minimum of their average cost curves. When they lack vibrant competition, they may lack incentives to provide innovative products and high-quality service.

The task of public policy with regard to competition is to sort through these multiple realities, attempting to encourage behavior that is beneficial to the broader society and to discourage behavior that only adds to the profits of a few large companies, with no corresponding benefit to consumers. Monopoly and Antitrust Policy discusses the delicate judgments that go into this task.

Bring It Home

The temptation to defy the law.

Oligopolistic firms have been called “cats in a bag,” as this chapter mentioned. The French detergent makers chose to “cozy up” with each other. The result? An uneasy and tenuous relationship. When the Wall Street Journal reported on the matter, it wrote: “According to a statement a Henkel manager made to the [French anti-trust] commission, the detergent makers wanted ‘to limit the intensity of the competition between them and clean up the market.’ Nevertheless, by the early 1990s, a price war had broken out among them.” During the soap executives’ meetings, sometimes lasting more than four hours, the companies established complex pricing structures. “One [soap] executive recalled ‘chaotic’ meetings as each side tried to work out how the other had bent the rules.” Like many cartels, the soap cartel disintegrated due to the very strong temptation for each member to maximize its own individual profits.

How did this soap opera end? After an investigation, French antitrust authorities fined Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and Proctor & Gamble a total of €361 million ($484 million). A similar fate befell the icemakers. Bagged ice is a commodity, a perfect substitute, generally sold in 7- or 22-pound bags. No one cares what label is on the bag. By agreeing to carve up the ice market, control broad geographic swaths of territory, and set prices, the icemakers moved from perfect competition to a monopoly model. After the agreements, each firm was the sole supplier of bagged ice to a region. There were profits in both the long run and the short run. According to the courts: “These companies illegally conspired to manipulate the marketplace.” Fines totaled about $600,000—a steep fine considering a bag of ice sells for under $3 in most parts of the United States.

Even though it is illegal in many parts of the world for firms to set prices and carve up a market, the temptation to earn higher profits makes it extremely tempting to defy the law.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/10-2-oligopoly

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Browse Course Material

Course info.

- Prof. Jonathan Gruber

Departments

As taught in.

- Microeconomics

Learning Resource Types

Principles of microeconomics, oligopoly i.

« Previous | Next »

Session Overview

Keywords : Oligopoly; cartel; game theory; Nash equilibrium; Cournot model; duopoly; non-cooperative competition.

Session Activities

Before watching the lecture video, read the course textbook for an introduction to the material covered in this session:

- [R&T] Chapter 11, “The World of Imperfect Competition.”

- [ Perloff ] Chapter 12, “Pricing and Advertising.” (optional)

Lecture Videos

- Lecture 16: Oligopoly I

- Graphs and Figures (PDF)

Further Study

These optional resources are provided for students that wish to explore this topic more fully.

Other OCW and OER Content

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

What Makes a Market an Oligopoly?

Do you know of any industries in which just three or four companies supply most of a specific product?

Some examples:

- From the 1950s to the 1980s, three major broadcast television networks dominated the U.S. airwaves.

- After a series of mergers between 2005 and 2015, four major airlines controlled much of the U.S. market, as a November 2018 Page One Economics essay described.

- Even more recently, shortages and price increases brought attention to the U.S. baby formula market and global insulin market, which also had just a few suppliers.

Those markets could be considered “oligopolies”—markets in which only a few sellers or suppliers dominate.

Suppliers and sellers in an oligopoly can command higher prices than companies in a competitive market, and if one company in an oligopoly stops producing, it has a bigger effect on supply than it would in a competitive market.

Read on for more comparisons of oligopolies to other types of markets and to learn how to tell whether a particular market could be considered an oligopoly.

What Is an Oligopoly?

As the table shows, in addition to having only a few sellers or suppliers dominating the market, an oligopoly has barriers to entering the market, and “there are few close substitutes for the product.”

In other words, certain conditions make it difficult for potential competitors to start selling or supplying a particular product or service within that industry, and there aren’t many alternatives that could be used instead. Monopolies—markets in which one firm dominates—also have those barriers.

“Barriers to entry” could include factors such as costly equipment needed to produce a product, patents restricting who can use an invention, and government regulations that are difficult to meet, as a Corporate Finance Institute article outlined.

What Are Examples of Barriers to Entry?

In the case of the U.S. infant formula market, barriers to entry have included tariffs and Food and Drug Administration standards . (Some of the infant formula market barriers were waived to help ease the shortage last year.)

Until the expansion of the cable TV market in the 1980s, the limited availability of broadcast frequencies helped to restrict the number of television networks, with the Federal Communications Commission in charge of allocating portions of the broadcast spectrum to stations.

Barriers to entry in the airline industry include high startup costs, such as for purchasing airplanes, competition for airport gates and large economies of scale, the Page One Economics essay said.

Government can put up barriers, as a St. Louis Fed Econ Lowdown lesson on market structures (PDF) outlined in discussing monopolistic markets. Such markets are rare, according to the lesson.

“Most commonly, [monopolistic markets] occur because government has granted a single firm the opportunity to supply a good or service. This is known as a ‘natural monopoly, ’ ” according to the lesson, which gives the examples of electric and natural gas providers. Because of the expensive infrastructure needed for those services, such as wires and pipes entering people’s homes, it’s cheaper for one firm to provide the service than to build infrastructure needed for true competition.

“In exchange, government often regulates prices in these markets to ensure that these firms do not take advantage of their market power,” the lesson says.

How Can You Tell If a Market Is an Oligopoly?

A “concentration ratio” is one tool that can indicate whether a market is an oligopoly.

A concentration ratio is the combined market share of the largest firms in an industry, according to Oxford Reference . That is, it’s the percentage of the industry’s products or services provided by those firms.

The number of firms used for the ratio can vary. A “four-firm” ratio is often used as a benchmark to show market structure, according to Oxford. But the ratios also can be calculated using the market share from the eight, five or three largest firms in the market, according to a September 2020 Investopedia article.

“A rule of thumb is that an oligopoly exists when the top five firms in the market account for more than 60% of total market sales,” the article says. “If the concentration ratio of one company is equal to 100%, this indicates that the industry is a monopoly.”

In 2015, the four major airlines controlled 80% of the U.S. market, the Page One Economics essay said. Three manufacturers have more than 90% of the global insulin market , according to a July 2022 press release from Grand View Research, a global market research and consulting company. That would make those markets oligopolies, according to the Investopedia rule of thumb.

What Are Two Types of Oligopolistic Markets?

Oligopolistic markets differ, and different types of markets have different effects on prices, as the Econ Lowdown lesson illustrates.

One such market is a collusive oligopoly , which has a few sellers who work together “to divide the market, set prices, or limit production,” the lesson says. Companies might, for example, agree to limit production to drive up prices. Such collusion is often illegal.

In a competitive oligopoly , the few sellers compete, which keeps the prices lower than they would be in a collusive oligopoly.

In general, more competition results in lower prices for consumers. So, a perfect competition market structure, in which lots of companies provide the same product, would result in lower prices, while a monopoly could mean the highest prices for consumers. Depending on whether they are collusive or competitive, oligopolies can be more like monopolies or more like perfect competition, respectively, as a Khan Academy video explains.

Can Oligopolies Change?

Market structures aren’t necessarily fixed, as the Page One Economics essay illustrated with the example of U.S. airlines.

Airline ticket prices declined as low-cost carriers started expanding their routes in 2016, the essay said. A chart from online database FRED shows the downward trend in airfares before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The proliferation of low-cost flights in recent years has pushed the airline industry, which was arguably an oligopoly, toward monopolistic competition,” the essay said.

Heather Hennerich is a senior editor with the St. Louis Fed External Engagement and Corporate Communications Division.

Related Topics

This blog explains everyday economics, consumer topics and the Fed. It also spotlights the people and programs that make the St. Louis Fed central to America’s economy. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other blog-related questions

Oligopoly Diagram

There are different diagrams that you can use to explain 0ligopoly markets.

It is important to bear in mind, there are different possible ways that firms in Oligopoly can behave.

1. Kinked Demand Curve Diagram

In the kinked demand curve model, the firm maximises profits at Q1, P1 where MR=MC. Thus a change in MC, may not change the market price. It suggests prices will be quite stable.

The kinked demand curve makes certain assumptions

- Firms are profit maximisers.

- If one firm increases the price, other firms won’t follow suit. Therefore, for a price increase, demand is price elastic.

- If one firm cuts price, other firms will follow suit because they don’t want to lose market share. Therefore, for a price cut, demand is price inelastic.

- This is how we get the ‘kinked demand curve

However, the kinked demand curve has limitations

- It doesn’t explain how the price was arrived at in the first place.

- Firms may engage in price competition.

Collusive Oligopoly

If firms in oligopoly collude and form a cartel, then they will try and fix the price at the level which maximises profits for the industry. They will then set quotas to keep output at the profit maximising level.

The price and output in oligopoly will reflect the price and output of a monopoly. The Quantity Qm will be split between the firms in the cartel.

Economies of scale for Oligopolies

Oligopolies may benefit from economies of scale. This enables lower average costs with increased output. FIrms in oligopoly producing at Q1 achieve lower prices of AC1.

Efficiency of firms in oligopoly

- Larger firms can benefit from economies of scale – lower average costs – which might outweigh other inefficiencies.

- Allocative efficiency? Not clear but firms operating under kinked demand curve may end up setting price higher than marginal cost. Also, firms able to successfully collude will set prices higher than MC. If oligopolies are competitive then prices will be lower and more allocative efficient.

- Dynamic efficiency? Firms in an oligopoly have profits they can use for investment in new products. Also, competitive pressures encourage them to innovate.

- How firms in Oligopoly compete

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Economics news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Economics Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Teaching PowerPoints

3.4.4 Oligopoly - Introduction (Edexcel A-Level Economics Teaching PowerPoint)

Last updated 13 Sept 2023

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

This PowerPoint covers an introduction to oligopoly.

An oligopoly is a market structure in which a small number of large firms or corporations dominate an industry or sector. In an oligopolistic market, there are typically just a few powerful players, and their actions and decisions can significantly influence the market's behavior. Oligopolies can exist in various industries, including manufacturing, telecommunications, banking, and retail.

Download this PowerPoint

- Kinked Demand Curve

- Non-Price Competition

You might also like

Study Notes

Concentration Ratio Pyramid - Lesson Activity

12th August 2015

Who were the world's most innovative companies in 2015?

6th January 2016

Fantasy Economics for AS and A2 students!

14th April 2016

Secondary ticket markets - blessing or curse for consumers?

19th December 2016

Will other buyers bid against Amazon for Whole Foods?

20th June 2017

Funeral charges under the competition microscope

5th December 2018

4.1.5.6 Monopoly and Monopoly Power (AQA A Level Economics Teaching Powerpoint)

Our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Understanding Oligopolies

- Potential Oligopolies

Current Examples of Oligopolies

The bottom line.

- Fundamental Analysis

- Sectors & Industries

Oligopolies: Some Current Examples

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

When companies within the same industry work together to increase their mutual profits instead of competing doggedly with one another, it is known as an oligopoly situation. Oligopolies are observed throughout the world and even appear to be increasing in certain industries. Unlike a monopoly , where a single corporation dominates a certain market, an oligopoly consists of a select few companies that combined exert significant influence over a market or sector.

While these companies are still technically considered competitors within their particular market, they also tend to cooperate or coordinate with each other to benefit the group as a whole. This anti-competitive behavior can lead to higher prices for consumers.

Key Takeaways

- Oligopolies occur when a small number of firms collude, either explicitly or implicitly, to restrict output or fix prices, in order to achieve above normal market returns.

- Oligopolies can be contrasted with monopolies where only one firm exists as a producer.

- Government policy can discourage or encourage oligopolistic behavior, and firms in mixed economies often seek government blessing for ways to limit competition.

- Examples of oligopolies can be found across major industries like oil and gas, airlines, mass media, automobiles, and telecom.

- The existence of oligopolies does not imply that there is coordination or collusion going on.